Significance

This study quantifies how protein levels are determined by the underlying 5′-UTR sequence of an mRNA. We accurately measured protein abundance in 2,041 5′-UTR sequence variants, differing only in positions −10 to −1. We show that a few nucleotide substitutions can significantly alter protein expression. We also developed a predictive model that explains two-thirds of the expression variation. We provide convincing evidence that key regulatory elements, including AUG sequence context, mRNA secondary structure, and out-of-frame upstream AUGs conjointly modulate protein levels. Our study can aid in synthetic biology applications, by suggesting sequence manipulations for fine-tuning protein expression in a predictable manner.

Keywords: post-transcriptional regulation, computational prediction, AUG sequence context, mRNA folding, upstream start codons

Abstract

The 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) of mRNAs contains elements that affect expression, yet the rules by which these regions exert their effect are poorly understood. Here, we studied the impact of 5′-UTR sequences on protein levels in yeast, by constructing a large-scale library of mutants that differ only in the 10 bp preceding the translational start site of a fluorescent reporter. Using a high-throughput sequencing strategy, we obtained highly accurate measurements of protein abundance for over 2,000 unique sequence variants. The resulting pool spanned an approximately sevenfold range of protein levels, demonstrating the powerful consequences of sequence manipulations of even 1-10 nucleotides immediately upstream of the start codon. We devised computational models that predicted over 70% of the measured expression variability in held-out sequence variants. Notably, a combined model of the most prominent features successfully explained protein abundance in an additional, independently constructed library, whose nucleotide composition differed greatly from the library used to parameterize the model. Our analysis reveals the dominant contribution of the start codon context at positions −3 to −1, mRNA secondary structure, and out-of-frame upstream AUGs (uAUGs) to phenotypic diversity, thereby advancing our understanding of how protein levels are modulated by 5′-UTR sequences, and paving the way toward predictably tuning protein expression through manipulations of 5′-UTRs.

The control of protein expression is a fundamental process of living cells. Much progress has recently been made in understanding how information encoded within DNA regulatory sequences is converted to yield a precise expression output (1–4). However, functional elements are also embedded within RNA sequences, such as 5′-untranslated regions (5′-UTRs). Accumulating evidence has revealed the importance of 5′-UTRs in shaping eukaryotic protein expression (5–12). Such 5′-UTR sequences encode a variety of cis-regulatory elements, including a 5′-cap structure (13), a translation initiation motif (14–16), upstream AUGs (uAUGs) and upstream ORFs (17, 18), internal ribosome entry sites (19), terminal oligo-pyrimidine tracts (20), secondary structures (21), and G-quadruplexes (22). Many of these elements were shown to control protein levels by altering the efficiency of translation (7–9, 11), whereas some elements affect translation and in addition, transcription (15) or mRNA degradation (23). Despite much progress, significant challenges remain in deciphering the rules by which multiple elements combine to fine-tune protein expression, as well as in quantifying the degree of expression variation that may be jointly explained by known and novel regulatory elements.

Traditionally, the impact of 5′-UTR elements on protein abundance is determined experimentally by comparing a perturbed 5′-UTR sequence with an appropriate control (16, 23–36). Although valuable insights emerged from such studies, they frequently focused on the influence of sequence manipulations on a single type of regulatory element. When several elements were examined, the relative contribution of each element and their pooled effect remained largely unclear. More importantly, previous investigations generated a relatively small number of sequence variants and, thus, were of limited utility for inferring predictive models of the effect of 5′-UTRs on protein abundance. Therefore, we have set out to develop a quantitative model of the impact of 5′-UTR–encoded elements on protein abundance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by generating a large pool of sequence variants that differ only in the 10 bp immediately upstream of the start codon of a fluorescent reporter. To this end, we fused the RPL8A (YHL033C, a ribosomal protein) promoter to a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) reporter and constructed a large-scale 5′-UTR library by introducing random mutations between positions −10 to −1 (relative to A[+1] of the AUG start codon). As the 5′-UTR of the RPL8A gene is relatively short (17 bp), our method can survey a significant fraction of the 5′-UTR sequence. Adapting a recent high-throughput sequencing approach (3), we obtained highly accurate measurements of protein abundance for 2,041 5′-UTR variants. We found that these sequence variants span an approximate sevenfold continuous range of expression values. Using computational analysis, we identified several key regulatory elements that determine protein expression output, including the AUG sequence context at positions −3 to −1, mRNA secondary structure, out-of-frame upstream start codons, and short k-mer sequences.

We developed robust models that have faithfully reproduced the observed quantitative changes in YFP abundance. Although we constructed the models on randomly selected subsets of 5′-UTR sequences, they explained, on average, 74% of the expression variation in held-out sequence variants. By incorporating the dominant features of these models, we show that a combined model with as few as 13 predictors explains 68% of the variation and the six major predictors explain 61% of the variation. To further validate our model, we tested its ability to predict protein abundance levels of a smaller, distinct pool of mutants that we constructed in the 5′-UTR of RPL8A. In this newly generated library, we only modified positions −6 to −1 and changed the overall sequence composition of the pool. Remarkably, the same model explained 71% of the expression variation of this additional pool, providing strong evidence that our model accurately represents significant regulatory elements that affect protein levels in our library.

Taken together, we demonstrate that sequence manipulations in the 10 base pairs preceding the start codon have a profound impact on protein outcome. In addition, we present a robust model that predicts most of the measured fluctuations in protein abundance.

Results

Construction and Measurement of Thousands of 5′-UTR Sequence Variants.

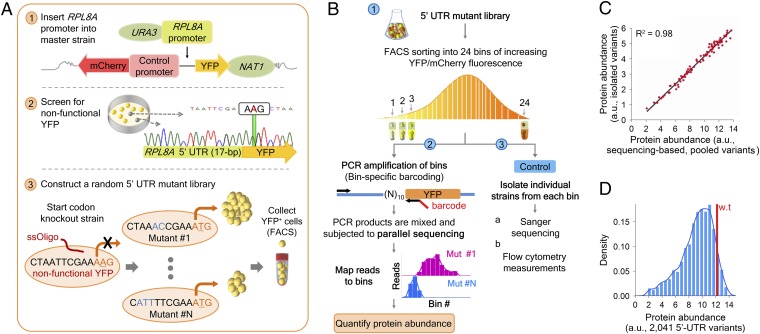

To explore the impact of 5′-UTRs on protein levels, we generated a pool of isogenic strains that differ only in the 10 bp preceding the translational start site of a YFP reporter (Fig. 1A). As our model gene, we selected RPL8A, a member of the tightly regulated ribosomal protein family, harboring a 17-bp–long 5′-UTR sequence (aaaacaactaattcgaaATG, determined by 5′-RACE; see Materials and Methods for details). We constructed a yeast strain containing a genomically integrated RPL8A promoter sequence fused to a YFP reporter, as recently described (37). We then used a single-stranded oligo transformation to create random mutations in the 5′-UTR of RPL8A between positions −10 to −1. As a control, all library strains contained an identical TEF2 promoter-mCherry cassette (TEF2 is a translation elongation factor), allowing us to estimate global variations in protein levels that were unrelated to our perturbations.

Fig. 1.

Accurate quantification of protein abundance in thousands of 5′-UTR sequence variants. (A) Schematics of the construction process of a 5′-UTR mutant library (see Materials and Methods for details). (B) Flow diagram of our experimental framework for measuring protein abundance levels. (1) We sorted our 5′-UTR mutant library into 24 bins according to the ratio between YFP and mCherry fluorescence (YFP/mCherry). (2) We PCR amplified each bin using bin-specific primers, each containing a unique 5-bp bar code sequence. We then pooled the obtained PCR products, subjected them to parallel DNA sequencing, and mapped each sequence read to a specific variant and to a specific bin (using the bin-specific bar codes). We quantified the mean protein abundance of each variant by using the distribution of its sequencing reads across expression bins (Materials and Methods). (3) As a control, we isolated individual strains from each bin, Sanger-sequenced the target 5′-UTR region, and measured the ratio between YFP and mCherry fluorescence by flow cytometry. (C) Our system provides highly accurate quantification of protein abundance levels. Shown is a comparison of the mean YFP-to-mCherry ratio as measured by flow cytometry (y axis; isolated variants), against abundance measurements estimated from our parallel sequencing approach (x axis; pooled variants) (R2 = 0.98). (D) The figure depicts the distribution of protein abundance levels among 2,041 sequence variants. Note that mutations in the 5′-UTR (between positions −10 and −1; aaaacaaNNNNNNNNNNAUG) generate approximately a sevenfold difference in protein levels.

We adapted a recent method (3) for accurately measuring protein abundance and sequencing the target region in thousands of different strains within a single experiment (Fig. 1B). Briefly, we sorted our mutant library into 24 bins based on the ratio of YFP to mCherry fluorescence (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Using a bin-specific bar-coding approach, we PCR amplified the target region of each variant and subjected our samples to parallel DNA sequencing. We then used these bar codes to unambiguously map each sequencing read to its corresponding bin (SI Appendix, Method S1). We identified 2,041 unique sequence variants (including wild type) composed, on average, of 40% A, 35% C, 10% T, and 15% G nucleotides (SI Appendix, Note S1). Each of these variants was covered by at least 100 sequencing reads, with many (60%) covered by more than 1,000 reads [median number of reads, 1,312 ± 1,168 median absolute deviation (MAD)]. Subsequently, we obtained for each variant a single measure of its mean protein abundance, based on the distribution of its sequencing reads across expression bins (Materials and Methods and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). For a list of sequence variants and protein abundance levels, see Dataset S1.

To gauge the accuracy of the resulting abundance levels, we isolated 84 strains from our sorted mutant pool and conventionally sequenced the target 5′-UTR segment (SI Appendix, Note S2). We measured for each individual strain the ratio of YFP to mCherry fluorescence by flow cytometry and compared the obtained measurements with our parallel sequencing estimations. We found excellent agreement between protein abundance derived from parallel sequencing data and isolated strains (Pearson's R2 = 0.98 for comparing the means; Fig. 1C). Our system can also estimate the SD with high accuracy (Pearson's R2 = 0.84; SI Appendix, Fig. S3), although it may not capture other aspects of the distribution equally well (SI Appendix, Note S3, and related SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

We assessed the influence of our mutations on protein output and found that protein expression was substantially affected, resulting in a continuous dynamic range of approximately sevenfold (Fig. 1D). Because YFP is linked to different 5′-UTR sequences and mCherry is under the control of a constant promoter (across all variants), we expected the differences in YFP expression to be primarily due to our 5′-UTR perturbations. Indeed, we did not find a significant correlation between YFP and mCherry fluorescence in our 84 single-strain controls (Pearson's R2 = 0.006, P = 0.47; Spearman's ρ = 0.15, P = 0.18). This is in line with our observation that, whereas YFP expression varies considerably, mCherry abundance has low variation (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Finally, to determine whether mutations in the 5′-UTR may also lead to differences in mRNA levels, we performed quantitative PCR for 15 sequence variants with a 4.5-fold range of protein levels (strains were chosen from our validation library; Materials and Methods). We found a high correlation between mRNA levels and protein abundance levels (Pearson's R2 = 0.71, P < 10−4; SI Appendix, Fig. S6), consistent with previous results showing that in yeast, reducing the efficiency of translation can sometimes lead to decreased mRNA stability (38–40).

Overall, the results show that our method can accurately measure protein abundance in thousands of variants and that perturbations immediately upstream of the start codon generate a substantial variation in protein output.

The Phenotypic Effect of Individual 5′-UTR Nucleotides at Positions −3 to −1.

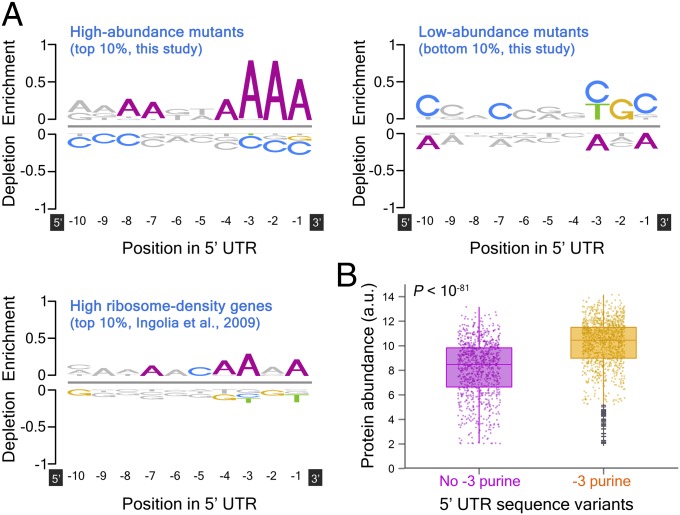

We subsequently sought to study the influence of individual nucleotides at specific positions on protein expression. We assessed the over representation and under representation of each nucleotide between positions −10 to −1 in highly and lowly expressed variants (10% of sequences with highest and 10% with lowest expression, respectively). We found that highly expressed variants (205 sequences) exhibit marked enrichment of adenine (P < 10−14) and moderate depletion of cytosine (P < 10−8) nucleotides in the three positions immediately upstream of the start codon (Fig. 2A, Upper Left). Conversely, suppressed variants (204 sequences) display some preference for a pyrimidine at position −3 (P < 10−3), guanine at position −2 (P < 10−5), and cytosine at position −1 (P < 10−4) (Fig. 2A, Upper Right). We obtained equivalent results for other fractions of highest and lowest expressed variants (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B). We performed similar analysis on a genome-wide scale in yeast and found that high ribosome density genes [10% of genes with highest ribosome density (530 genes); ref. 5] have a comparable, albeit weaker, enrichment profile, particularly at position −3 (Fig. 2A, Lower Left; for analysis of low ribosome density genes, see SI Appendix, Fig. S7C).

Fig. 2.

The effect of specific nucleotides on protein levels. (A) The first three positions upstream of the start codon are key determinates of protein expression in our library. Shown are position-specific, logo-like representations of enrichment (over representation) and depletion (under representation) for highly (Left Upper) and lowly (Right Upper) expressed variants and high ribosome density genes in yeast (Lower Left). Over representation and under representation were calculated using the formula: Eset[i,k] = Pset[i,k]*log2(Pset[i,k]/Pback[i,k]), where, Pset[i,k] denotes the probability of nucleotide i at position k in a subset of sequence variants (e.g., 10% of sequences with highest expression) and Pback[i,k] is the probability of the same nucleotide at the same position in the appropriate background model (the remaining set of sequences). The relative height of individual symbols (A, C, G, or T) equals to Eset[i,k], whereas enrichment and depletion are indicated by positive and negative Eset[i,k] values, respectively. Statistical significance was quantified by using a two-tailed Fisher's exact test, controlling for a false discovery rate (74) of 1%. Nucleotides with false discovery rate-corrected P values greater or equal to 0.01 are colored gray. The genome-wide analysis is based on average ribosome densities of two biological replicates (5). (B) Purine at position −3 supports high levels of expression. Box plots of protein abundance (y axis) in the presence (orange; n = 1,164) and absence (magenta; n = 877) of a −3 purine. Outliers (gray plus signs) are defined as expression levels that are either larger than the upper quartile or smaller than the lower quartile by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range. See SI Appendix, Fig. S9, for position-specific comparisons of protein levels in the presence and absence of each of the four nucleotide bases.

In mammalian cells, there is a strong nucleotide preference for a purine (A/G) at position −3 (Kozak sequence, A/GCCaugG), previously demonstrated to be necessary for efficient translation (9). Motivated by this, we compared protein levels in the presence (n = 1,164) and absence (n = 877) of a −3 purine. We found a notable increase in protein levels in −3 purine-containing strains (P < 10−81; Fig. 2B), although the magnitude of the effect is relatively modest (expression is elevated from 8.5 ± 2.2 to 10.5 ± 1.8; median ± MAD), consistent with small-scale studies in yeast (33, 36, 41). Quantification of the potentially confounding effect of nearby nucleotides (at positions −5, −4, −2, and −1) suggests that the positive influence of a purine at position −3 holds across several sequence contexts (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Interestingly, the concurrent occurrence of a −3 purine and an adjacent adenine (at positions −4, −2, or −1) enhances expression, compared with −3 purine alone (P < 10−20; SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). Moreover, the presence of adenine at position −1 can, by itself (without a −3 purine), increase protein levels (P < 10−29; SI Appendix, Fig. S8C).

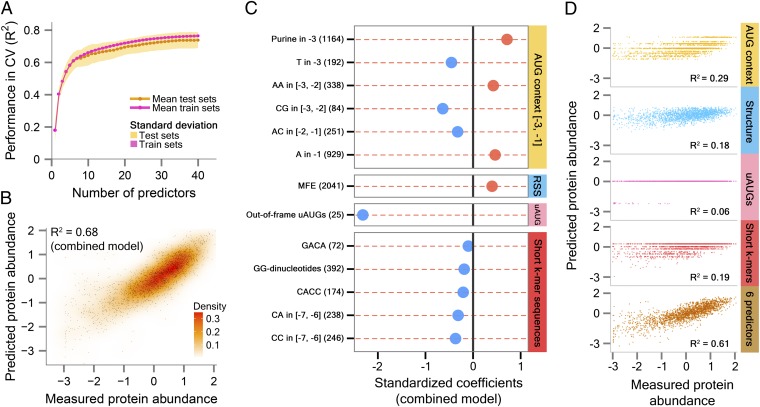

Taken together, our findings indicate that the AUG context, particularly at the three positions immediately upstream of the start codon, has a significant effect on protein levels (explaining 29% of the total expression variation in our library; Fig. 5D, orange, Top).

Fig. 5.

Quantitative models predict over 70% of the variation in protein levels in held-out test sets. (A) Prediction performance reaches a plateau at 20–25 predictors. The colored lines depict the average R2 (y axis) obtained in a 10-fold cross-validation (CV) strategy for linear models that each uses a different number of feature predictors (x axis), for both the train (magenta) and test (orange) sets. The colored areas above and below the lines represent the SD. Note that a high fraction of the expression variation can be explained, for example, by using 20 predictors (mean ± SD, test R2 = 0.69 ± 0.05), whereas adding further features only marginally improves performance (mean ± SD, test R2 = 0.74 ± 0.05; 40 predictors). (B) A combined model with as few as 13 predictors explains 68% of the expression variation in our library. A comparison between measured protein abundance (x axis) and abundance levels predicted by our combined model (y axis), using the 13 most informative predictors. Protein abundance levels are expressed as standardized scores (during model construction, continuous predictors and measured protein levels were standardized to zero mean and unit SD; binary predictors were coded as 1 and 0). (C) A graphical depiction of our combined model. Shown are the 13 predictors (y axis) included in our combined model with their respective model coefficients (x axis): (i) Nucleotide preferences at positions −3 to −1 (six features, orange); (ii) mRNA secondary structure (abbreviated as RSS, light blue); (iii) out-of-frame uAUGs (pink); and (iv) short uncharacterized k-mers (five features, red). Positive and negative coefficients are marked in red and light blue dots, respectively. Numbers in brackets indicate the quantity of variants associated with each predictor. (D) Predictive power of different feature groups. We constructed a linear regression model for each of the four feature groups from C, reporting the proportion of variance explained (R2) by each group. In addition, we found that the top six most dominant predictors in our combined model account for 61% of the expression variation (dark orange, Bottom). The six predictors are as follows: a purine at position −3, adenine at position −1, mRNA secondary structure, out-of-frame uAUGs, GG-dinucleotides, and a CACC pattern. As in B, protein abundance levels are expressed as standardized scores. R2 values indicate the average performance obtained on test sets, using 10-fold CV.

mRNA Secondary Structure Is Correlated with Protein Abundance.

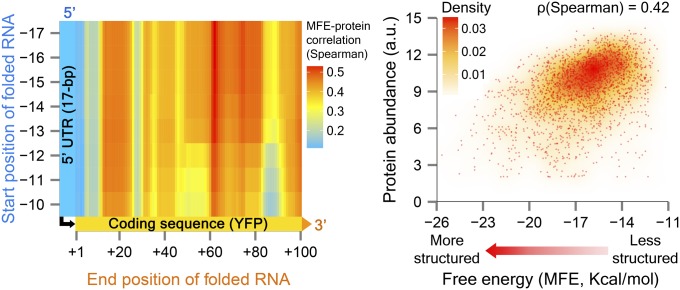

Previous analyses in S. cerevisiae have suggested that mRNA secondary structures of endogenous 5′-UTRs have small but significant inverse correlation to protein abundance (42) and ribosomal density (42, 43). However, the validity of this association in the context of 5′-UTR sequence manipulations has only been tested in small-scale experiments (34, 35, 41, 44, 45). To study the contribution of secondary structure to expression variation, we computed the folding free energies for our variants across a range of mRNA lengths and positions. As the free energy measure, we used the minimum free energy (MFE), representing the most stable structure of an RNA sequence (46). We found a significant association between thermodynamically stable secondary structures (lower MFE) and reduced protein levels for all folding segments, predominantly when including at least the first 12–13 bp of YFP (Fig. 3, Left; Spearman's ρ = 0.4 ± 0.08, median ± MAD; P < 10−4 for all tested regions). Although it was previously shown that the MFE can predict ∼70% of secondary structure (47), some RNAs can give rise to several structures (48, 49), and the MFE may not always represent the native conformation (50). Therefore, we additionally calculated the ensemble free energy (EFE; using RNAfold, ref. 51), expressing the sum of contributions of the Boltzmann-weighted free energies of possible structures for a given RNA sequence. Notably, the EFE produced very similar results with a Spearman correlation of 0.43 ± 0.08 (median ± MAD; P < 10−5 for all tested regions; SI Appendix, Fig. S10, and SI Appendix, Note S4).

Fig. 3.

Stable mRNA secondary structures are correlated with reduced protein levels. The left panel shows a heat map of Spearman correlations, where each correlation denotes the association between the minimum free energy (MFE) of a given mRNA region and protein levels, in 2,041 variants. We used the region between −10 and −1 as the smallest folding segment, while moving upstream and/or downstream in 1-bp steps (up to −17 and +100). The y and x axes represent the start (in 5′-UTR) and end (in coding region) position of each folded segment, respectively. For each correlation, we obtained a two-sided P value by performing 100,000 permutation tests of shuffled expression values. For clarity of the figure, we removed folding segments that include only 5′-UTR nucleotides, without the YFP coding region (the Spearman's ρ for these regions is 0.09 ± 0.003; median ± MAD; P < 0.001). The right panel shows an example of the above relationship for the mRNA segment between positions −15 to +50 (Spearman's ρ = 0.42, P < 10−86). We obtained equivalent results, albeit with slightly higher correlations, by using the ensemble free energy measure (SI Appendix, Fig. S10, and related SI Appendix, Note S4). Folding free energies were computed with RNAfold from the Vienna RNA package at a folding temperature of 30 °C (51).

To further explore the correlation between MFE and protein abundance, we divided our data into four equally sized intervals of MFE values (total range, −25.66 to −11.18 kcal/mol). We calculated the MFE for the region between positions −15 to +50, which has a relatively high MFE–protein correlation (Spearman's ρ = 0.42; Fig. 3, Right). We found significant correlations between MFE levels and protein abundance levels for sequence variants from the three lower intervals (MFE between −25.66 and −14.8 kcal/mol) (largest P = 0.01; SI Appendix, Fig. S11). We also partitioned the data based on the protein fold-range of each variant (the ratio between the expression of its maximal and minimal bin) and found significant correlations for all subsets (largest P < 0.01; SI Appendix, Table S1).

To estimate the relevance to endogenous 5′-UTRs, we explored the genome-wide association between the thermal stability (MFE) of yeast mRNAs around start codons and ribosomal density (used as a proxy for translation efficiency). We obtained small but significant associations (largest Spearman's ρ = 0.224 for positions −27 to +23; P < 10−38; SI Appendix, Fig. S12), supporting the broader significance of our findings.

Our results suggest that sequence variants that are folded into stable mRNA secondary structures tend to produce less protein (R2 = 0.18; Fig. 5D, light blue panel), most likely because such structures impede translation initiation (21, 34, 35, 45).

Out-of-Frame Upstream AUGs Attenuate Protein Expression.

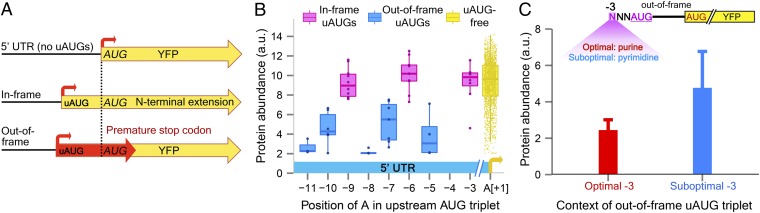

uAUGs are key functional elements in 5′-UTRs, known to affect the efficiency of translation (17, 23, 52). To gain insights into their effect on our library, we compared the protein abundance levels of uAUG-free variants and sequences harboring a single in-frame or out-of-frame uAUG (the native 5′-UTR of RPL8A does not contain a uAUG). We defined a uAUG as a start codon upstream of the main ORF, without a subsequent in-frame stop codon in the 5′-UTR (see Fig. 4A for illustration and legend for comment). We anticipated that in-frame upstream start codons would not affect protein levels considerably, as they may produce a functional N-terminally extended protein, exclusively or in addition to the major polypeptide (9, 17, 30, 53). Indeed, in-frame upstream start codons (27 variants) did not attenuate protein expression compared with uAUG-free sequences (n = 1,989) (P = 0.84). In sharp contrast, out-of-frame uAUGs produced a highly significant repression of ∼2.4-fold, on average (25 sequences; mean ± SD, 3.9 ± 2), in comparison with in-frame (mean ± SD, 9.5 ± 1.8; P < 10−12) and uAUG-free variants (mean ± SD, 9.3 ± 2.4; P < 10−13) (Fig. 4B), most likely resulting from premature termination of translation within the YFP coding sequence. This inhibitory effect is not confounded by other sequence differences (SI Appendix, Fig. S13).

Fig. 4.

Out-of-frame upstream start codons attenuate protein expression. (A) Schematic representation of in-frame and out-of-frame uAUGs. We note that our definition of a uAUG (see text) differs from the traditional upstream ORF (uORF) which usually contains a uAUG triplet and an in-frame stop codon, fully embedded within the 5′-UTR. (B) Out-of-frame uAUGs decrease protein levels. Shown are position-specific box plots of protein abundance (y axis) for out-of-frame uAUGs (light blue), in-frame uAUGs (magenta), and uAUG-free sequences (yellow). The x axis indicates the position of the A nucleotide in the uAUG triplet (relative to the main ORF). Note that RPL8A contains an adenine nucleotide at position −11 (there are no mutations at this position) and hence may form a uAUG codon. P values (see text) were obtained using two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. (C) The inhibitory effect of out-of-frame uAUGs is augmented by optimal uAUG context. The graph represents a comparison of protein abundance levels of out-of-frame uAUG variants with optimal (purine, red bar) and suboptimal (pyrimidine, light blue bar) nucleotides at position −3 upstream of the uAUG codon (two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum, P < 0.01). Error bars represent the SD.

Based on earlier reports (16, 29, 36), we hypothesized that the effect of out-of-frame uAUGs may vary, depending on their neighboring sequence context. To test this, we compared out-of-frame uAUG variants with optimal (purine) and suboptimal (pyrimidine) nucleotides at the −3 position upstream of the uAUG triplet (Fig. 4C). We found an almost complete abolishment of protein output in out-of-frame uAUGs within an optimal context (mean ± SD, 2.4 ± 0.6; n = 9), versus suboptimal context (mean ± SD, 4.8 ± 2; n = 16) (P < 0.01). This result implies that when positioned within a favorable context, uAUGs promote more frequent translation from the uAUG codon, thereby acting as a barrier for downstream translation of the main ORF. Because these uAUGs are out-of-frame, they are likely to produce aberrant proteins, resulting in considerable attenuation of protein expression. For the in-frame uAUGs, expression levels were invariably high, regardless of the uAUG context, with average expressions of 9.8 ± 1.4 SD (n = 20) and 8.7 ± 2.4 SD (n = 7) in variants with optimal and suboptimal context, respectively (two-sided Wilcoxon P = 0.29). Notably, upstream out-of-frame non-AUG initiation codons had a relatively minor impact, if any, on protein levels in our library (SI Appendix, Fig. S14).

Overall, because a small fraction of 5′-UTR sequences contains an out-of-frame uAUG triplet (1.2%), this element explains only 6% of the expression variation in our library (Fig. 5D, pink panel). Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that, when present, out-of-frame uAUGs can act as powerful inhibitors of protein levels, depending on the context of the uAUG codon.

Quantitative Model of 5′-UTR–Mediated Regulation of Protein Expression.

Although each of the above elements is correlated with protein abundance and likely affects protein levels, none of these features on their own can fully account for the observed expression variation in our library. We thus sought to devise a quantitative model that integrates these features and other elements, with the goal of predicting protein abundance measurements. We compiled a list of potential predictors, including mRNA secondary structure, in-frame and out-of-frame uAUGs, non-AUG start codons, predicted nucleosome occupancy, sequence composition statistics, and arbitrary k-mer sequences (SI Appendix, Table S2). We then used a cross-validation (CV) scheme (SI Appendix, Fig. S15), whereby we tested the ability of a model whose parameters were estimated from a subset of 5′-UTR variants (the training set), to predict protein levels of the remaining held-out set of sequences (the testing set). We randomly partitioned our dataset into 10 equally sized groups, where 9 groups were used for training and the 10th group for testing. Based solely on the training data, we selected a subset of features and used this subset to construct a linear model. We then applied this model to predict the protein abundance of the 10th held-out group and assessed its performance (R2 or proportion of variance explained) by comparing its predictions with the experimentally obtained measurements. We repeated this process 10 times, each time holding out a different group for testing while using the remaining groups for training. To gauge the overall performance of the resulting models, we computed the average test R2 across all 10 CVs and found that the predictions of the models on held-out variants explained, on average, 74% of the variation in protein levels (mean ± SD, test R2 = 0.74 ± 0.05; mean ± SD, train R2 = 0.76 ± 0.01; 40 predictors; Fig. 5A).

To identify the most influential features and to estimate the minimal number of features necessary for robust prediction, we generated a combined regression model (SI Appendix, Fig. S15). To this end, we extracted features that appeared in all 10 CVs and subjected them to best-subset regression analysis (using a variant of the Bayesian information criterion; ref. 54). We found that a combined model containing the top 13 most predictive features (an arbitrarily chosen number, used as a compromise between performance and number of predictors), accounted for 68% of the expression variation (Fig. 5B). This model includes sequence preferences at the first three positions preceding the start codon (six features), mRNA secondary structure, out-of-frame uAUGs, and uncharacterized k-mers (five features) (Fig. 5C). We assessed the individual contribution of each of the above predictor sets by distinct models (Fig. 5D) and found that a relatively large fraction of the expression variation can be explained using the AUG context at positions −3 to −1 (29%) or mRNA secondary structure (18%). Smaller portions were accounted for by out-of-frame uAUGs (6%). Notably, 90% of the predictive power of the combined model is attributed to merely six predictors (explaining 61% of the variation; Fig. 5D, dark orange, Bottom).

Our findings show that two-thirds of the variation in protein expression can be predicted by integrating a relatively small number of features. Analysis of the individual contributions of these features provides strong evidence for the dominant role of the AUG context at positions −3 to −1, mRNA secondary structure, and out-of-frame uAUGs.

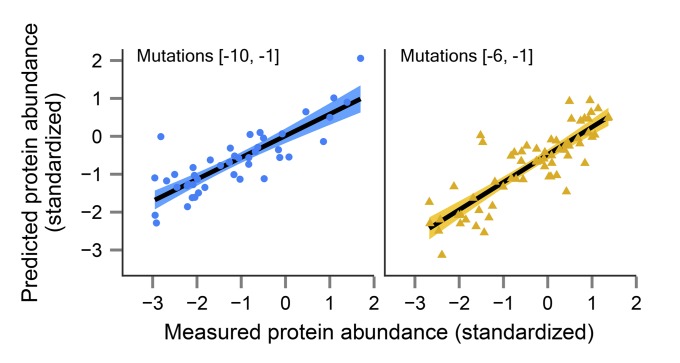

Accurate Prediction of a Mutant Library with a Distinct Base Composition.

To test the generality of our model, we constructed two additional libraries in the same 5′-UTR sequence (RPL8A). In one library, we repeated the original mutagenesis, generating a second A/C-rich collection of random perturbations at positions −10 to −1 (44 variants). In the other, we constructed a pool of G/C-rich sequences in which we randomly mutated only positions −6 to −1 (65 variants). We subjected each library to Sanger sequencing and microplate reader measurements of the YFP-to-mCherry ratio, as previously described (37). Most critically, the new pools contained distinct sequence variants that were not present in the large-scale library. These libraries had substantial fluctuations in protein levels as well, with 6.5-fold (first pool) and 4.6-fold (second pool) differences. Notably, the combined model, which was generated using only the large-scale collection, explained 69% (Fig. 6, Left) and 71% (Fig. 6, Right) of the expression variation in the first and second independently constructed libraries, respectively. Of note, mRNA secondary structure was of higher importance in the G/C-rich collection. These results offer convincing independent validation for the generality of our model and for its ability to accurately capture the quantitative effects of modifications in the 5′-UTR on protein levels in RPL8A.

Fig. 6.

Our combined model successfully accounts for most of the expression variation in two additional, independently constructed RPL8A 5′-UTR mutant pools. Shown is a comparison between measured protein abundance (x axes) and predictions made by our combined model (y axes) for: (i) An A/C-rich collection with random mutations between positions −10 to −1 (44 variants; Left; R2 = 0.69), and (ii) a G/C-rich collection with random perturbations between positions −6 to −1 (65 variants; Right; R2 = 0.71). The predictions were based on standardized features (z scores), whereby we used the mean and SD obtained for a specific feature in the large-scale library to standardize the same feature in the new collections (assuming that all pools come from the same probability distribution). Binary predictors were coded as 1 and 0. Linear fits are depicted in black with their respective 95% confidence intervals (the colored area above and below the lines).

Discussion

In this study, we constructed a robust model that successfully predicts the combined effect of different 5′-UTR elements on protein levels, based on mutations in the RPL8A 5′-UTR region immediately upstream of the start codon (positions −10 to −1). To directly measure the impact of 5′-UTRs on protein levels, we devised an experimental system that isolates the effect of different 5′-UTR sequences from other regulatory regions, such as promoters and 3′-UTRs. Using parallel DNA-sequencing methodology, we accurately determined protein abundance in thousands of variants, differing only in the sequence spanning positions −10 to −1. We show that random perturbations in the 5′-UTR produce a marked and gradual change in protein abundance (approximately sevenfold). By exploring the sequence differences among our variants, we identified several key regulatory principles, including the composite impact of the AUG context at positions −3 to −1 and the negative influence of mRNA secondary structure and out-of-frame uAUGs. We demonstrate that a combined model that uses a relatively small number of feature predictors (13 features), explains a highly significant fraction (68%) of the variation in protein levels in our library. Nevertheless, our current model cannot account for the remaining ∼30% of variation, which might be related to experimental noise and yet-uncharacterized biological factors.

A detailed examination of the individual contributions of our predictors allowed us to dissect their relative importance. We show that the combined effect of nucleotides in the three positions immediately upstream of the start codon is relatively large (R2 = 0.29), where a purine at position −3 has the greatest (positive) impact on protein levels. Additionally, we found that the −3 position of high ribosome density genes in yeast is relatively enriched with adenine. These results reinforce previous findings from (i): small-scale mutagenesis experiments, which indicate that protein expression in yeast is positively and negatively affected by a purine (mostly adenine) and a pyrimidine at position −3, respectively (33, 36, 41); and (ii) a genome-wide survey of high ribosome-occupancy genes, showing that natural 5′-UTRs in yeast are typically A-rich, particularly at positions −4 to −1 (14). In mammalian cells, although the optimal motif upstream of the AUG codon (GCCA/GCCaug) differs overall from that of yeast, a purine at position −3 (in bold) is a key factor in determining the efficiency of translation (9, 16, 55). This −3 purine is thought to exert its beneficial action on the selection of AUG codons via specific interaction with eIF2α, a component of the mammalian 43S preinitiation complexes (56). However, unlike mammalian systems (9) and in accordance with earlier reports in yeast (33, 36, 41), our study indicates that in the absence of a −3 purine, expression levels are only moderately impaired, suggesting a role for other regulatory elements in shaping protein levels.

We also found that the folding free energies of manipulated 5′-UTRs are significantly correlated with protein levels (R2 = 0.18). This finding is congruent with large-scale investigations of natural 5′-UTRs in yeast (42, 43), primarily when involving the 10 bp preceding the start codon (43). However, the strength of the relationship is considerably greater for manipulated 5′-UTRs (compare Fig. 3 with SI Appendix, Fig. S12). Interestingly, in comparison with mammalian cells (57), yeast 5′-UTRs were suggested to be more sensitive to the introduction of secondary structures (34, 41, 44, 45, 58). Such base-paired structures may act to slow down ribosomal scanning by impeding the unwinding activity associated with RNA helicases (59). Whereas natural 5′-UTRs in yeast have evolved to be relatively free of stable secondary structures (43, 60, 61), we suggest that sequence manipulations in the 10 bp preceding the translational start site can be applied effectively to generate structured mRNAs which can modify protein output.

In addition we provide evidence that out-of-frame uAUGs repress protein levels at the main ORF by more than 50% on average. We show that a favorable context (−3 purine) at the upstream vicinity of out-of-frame uAUG codons, nearly abolishes the expression of YFP, transforming these uAUGs into potent suppressors. Of note, the limited number of sequence variants that contain an out-of-frame uAUG codon (25 variants) is likely to account for the small contribution of uAUGs to the total explained variation in our library (6%). Our findings corroborate previous analyses in yeast (23, 36) and humans (31). Because translation is typically initiated at the first in-good context AUG codon encountered by a scanning ribosome, AUGs upstream of the main ORF can hinder initiation at the canonical AUG (9, 62). When the uAUG is in-frame, a functional protein isoform with an N-terminal extension may be produced (9, 17, 30, 53). In contrast, ribosomes initiating at an out-of-frame uAUG, frequently encounter an early termination codon, and may trigger RNA degradation via nonsense-mediated decay (23). Nevertheless, when an out-of-frame uAUG is embedded in a suboptimal context, a fraction of the ribosomes may skip the uAUG and initiate translation at the main start codon (leaky scanning), resulting in a less dramatic inhibition of protein expression (16, 29, 36). From an evolutionary standpoint, because uAUGs in yeast may have a detrimental effect on protein levels, it was suggested that they are exposed to strong forces of purifying selection, causing pronounced depletion of uAUGs in natural 5′-UTRs (23, 63). However, uAUGs were shown to be relatively conserved in the ∼20% of genes that retained their uAUG triplets (23), implying that such upstream start codons have a pivotal functional role (23, 63).

Furthermore, we identified several short sequence patterns (R2 = 0.19) with no characterized function or clear mechanistic role.

Finally, we show for a selected set of variants that perturbations in the 5′-UTR can alter both protein and mRNA levels. However, we observed a greater absolute change in protein levels (4.5-fold) than in mRNA levels (2.9-fold). In addition, a model consisting mostly of features related to translation explains ∼70% of the variation in protein levels in our library (Fig. 5). Together, these findings suggest that most of the differences in mRNA levels are due to translation-mediated RNA degradation, as demonstrated before (38–40). Although we cannot exclude possible effects on transcription, coupling between translation and mRNA degradation has previously been demonstrated in manipulated 5′-UTRs. Examples of these manipulations include: the introduction of strong secondary structures (64) or an upstream ORF (65) in the 5′-UTR, changing the AUG context (66), and generating out-of-frame uAUGs (23).

Our study has several limitations. As we only analyzed one gene and with a relatively short 5′-UTR, it is unclear whether our model can be generalized to other genes, in particular genes with longer 5′-UTRs, in which additional modes of regulation might play a greater role. Moreover, although we generated a comprehensive pool of sequences, only a subset of the possible 10-mer space was measured and the effect of unexplored variants remains unknown. Nevertheless, our model is highly predictive of both held-out sequence variants and of an independently constructed pool with a distinct base composition (exploring a different part of the sequence space), indicating that it can capture a major fraction of the underlying rules.

Overall, we devised a robust model that integrates the effects of several distinct 5′-UTR regulatory elements on protein levels and which is capable of predicting these effects with high accuracy. In this study, we mutated the 5′-UTR of RPL8A, a highly expressed gene, and have shown that the vast majority of sequence variants have lower protein levels compared with the wild type strain. We hypothesize that there might be certain genes, particularly lowly expressed genes, for which 5′-UTR manipulations can substantially elevate expression. However, additional experiments are necessary to directly test this hypothesis. As the role of 5′-UTRs in shaping protein levels is further studied, it will be important to apply similar methods to both highly and lowly expressed genes, in diverse environmental conditions. To arrive at a more comprehensive understanding of the regulatory code embedded within 5′-UTRs, it will be necessary to experimentally test the genome-wide involvement of various 5′-UTR elements, and the relative contribution of each element to both transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation.

Materials and Methods

OD Measurements.

OD measurements of yeast cells at 600 nm refer to ∼5 × 106 cells per mL in one OD unit.

Generation of an RPL8Apromoter-YFP Start Codon Knockout Strain.

A master strain was constructed by introducing a dsDNA cassette composed of [ADH1 terminator-mCherry-TEF2 promoter]-[YFP-ADH1 terminator-NAT1] into the Y8205 yeast strain at the histidine deletion locus (his3), as previously described (ref. 37; see this reference for the master strain sequence). This master strain served as a template for building an RPL8Apromoter-YFP start codon knockout strain (Fig. 1A). The RPL8A promoter, defined as the sequence from its translational start site to the end of its upstream neighboring gene, was amplified by PCR from the BY4741 yeast strain and linked to a uracil selection marker (URA3) using a PCR-based procedure (67). To allow efficient integration into yeast DNA, the 3′-tail was extended to 45 bp. Next, the URA3-RPL8Apromoter fusion product was inserted into the master strain genome by homologous recombination (68), directly upstream of YFP. Transformants were selected on synthetic complete plates lacking uracil and screened by a Typhoon imager to identify RPL8A+ colonies lacking a functional YFP reporter activity. To validate the correct insertion of RPL8A and to identify strains carrying a nonfunctional YFP gene, individual colonies were amplified by PCR and Sanger-sequenced. The resulting strain contained a point mutation in the translational start site of YFP (ATG to AAG; Segal laboratory strain 556; for sequence, see SI Appendix, Method S2). Primers are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3 A–F.

Inactivation of MSH2 (MutS Homolog 2).

Single-stranded DNA oligos can be used to produce small genetic modifications via a simple transformation procedure (69). Because the transformation efficiency may be reduced by the endogenous mismatch repair system (70), MSH2 (YOL090W), a DNA mismatch repair gene, was inactivated by partial deletion and replaced by a kanamycin-resistance marker (KanMX4) (Fig. 1A). Briefly, a KanMX4 cassette was PCR amplified from the pKT103 plasmid (pFA6a-link-yEVenus-KAN) obtained from EUROSCARF. Primers included 20 bp matching to pKT103 and 40-bp tails homologous to the ORF (in reverse primer) or upstream region (in forward primer) of MSH2. The KanMX4 construct was then transformed into the RPL8Apromoter-YFP start codon knockout strain (Segal laboratory strain 556), and G418-resistant transformants were selected and verified by PCR (Segal laboratory strain 556ΔMSH2). For primers, see SI Appendix, Table S3 G–J.

Single-Stranded Oligonucleotide Design.

A single-stranded oligonucleotide (ssOligo) (56-bp–long) was designed to contain a 10-bp stretch of random nucleotides, flanked by constant sequences matching to RPL8A (positions −34 to −11, relative to A[+1] of the AUG start codon) and a part of YFP (positions +1 to +22) at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. To allow start codon repair (reactivating YFP expression), the ssOligo included an ATG triplet corresponding to the mutated start codon of YFP (AAG). ssOligos were obtained from IDT (Integrated DNA Technologies) with standard purification (for sequence, see SI Appendix, Method S3).

Construction of a Large-Scale 5′-UTR Mutant Library.

Random mutations in the 5′-UTR of RPL8A were created by following an electroporation-based single-stranded oligo transformation (modified from Otsuka et al.; ref. 69). A single clone from a freshly streaked plate of an RPL8Apromoter-YFP start codon knockout strain (Segal laboratory strain 556ΔMSH2) was inoculated into 5 mL of yeast extract peptone dextros (YPD, rich medium) and incubated overnight at 30 °C. The culture was then inoculated in 45 mL of YPD and grown for approximately three cell divisions. The cells were harvested by centrifugation (2,800 × g for 3 min, 4 °C) and immediately chilled on ice for 5 min, rinsed twice with ice-cold double-distilled water, and once with cold 1 M sorbitol. Competent cells were finally generated by resuspending the cells in 900 μL of sterile 1 M sorbitol. Aliquots of 100 μL of competent cell suspension (containing ∼108 cells each) were pelleted by centrifugation and mixed with ssDNA oligos (8 nmol), resuspended in sorbitol (to a final concentration of 1 M), and incubated on ice for 5 min. The mixture was electroporated on a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, using a prechilled electroporation cuvette) at 200-Ω pulse, 25 μF, and 1.5 kV. Electroporated cells were immediately suspended in 1 mL of YPD and allowed to recover in 100 mL of YPD overnight.

Collection of Mutant Cells.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting was used to detect YFP+ cells, resulting from the ssOligo-mediated start codon repair. Cells were filtered using tubes with cell strainer caps (BD Falcon) to remove large cell aggregates, diluted in YPD (1:10), and sorted with a FACSAria sorter (Becton Dickinson). Isolated YFP+ cells were grown to stationary phase at 30 °C under continuous shaking (250 rpm) in fresh YPD (50 mL) and stored at −80 °C. To verify the correct construction of a mutant library, individual colonies were randomly selected, amplified by PCR, and Sanger-sequenced (for primers, see SI Appendix, Table S3 K and L).

Sorting into 24 Expression Bins.

To prepare the cells for bin sorting, stationary library cultures were thawed and diluted in YPD (500 mL) to OD600 0.02–0.03 and allowed to grow to stationary phase (30 °C at 250 rpm). Cells (1 mL at OD600 of ∼12) were then diluted to OD600 of ∼0.05 and grown until cell density reached midexponential phase (OD600 of 0.5–1.5). Next, the cells were filtered with cell strainer caps (BD Falcon) to remove clumps and sorted using a Becton Dickinson FACSAria sorter equipped with 488- and 561- nm lasers. We used fresh mid log phase cultures for each round of sorting. Sorting gates were constructed on the basis of the following: (i) side scatter (SSC)-A vs. forward scatter (FSC)-A profile; (ii) FSC-W vs. FSC-A profile; (iii) mCherry fluorescence (used as a control, excluding too-high or too-low intensity levels); and (iv) YFP background levels (autofluorescence was determined by measuring the YFP fluorescence intensity of our start codon knockout strain). We then sorted the cells into 24 bins (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) based on the ratio of YFP to mCherry, from lowest (bin 1) to highest (bin 24). Because the sorting process is labor intensive, we decided to use 24 bins as a trade-off between experimental complexity and the ability to achieve appropriate resolution. We collected a total of ∼5,400,000 cells (from all 24 bins). Bins were inoculated in YPD (5 mL each) and incubated at 30 °C until reaching stationary phase (OD600 of ∼12; stored at −80 °C).

Design of Bar Codes and Primers.

A set of 24 reverse primers (25 bp each, one for each bin) was designed to contain a constant region (20-bp–long) matching the start of YFP (positions +1 to +25; constant in all strains across all bins) and a unique 5-bp bar code sequence (5′-XXXXXAATTCTTCACCTTTAGACAT-3′, where the Xs denote the unique 5-bp bar code). The forward primer (one, 25-bp–long) consisted of 22 bases corresponding to RPL8A promoter and a randomized 3-bp–long region at the 5′ end (5′-NNNGACGCTAAATTGTTTATAAAGG-3′, the random Ns part was required for sequencing by oligonucleotide ligation and detection (SOLiD) and was not used in any downstream analysis). Primers and bar codes are listed in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Sample Preparation for Sequencing.

Stationary phase cultures of library bins (25 μL of cells per bin) were grown in YPD (175 μL) to saturation in 96-well plates (at 30 °C). Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation (3,220 × g for 1 min) and heat treated at 99 °C for 10 min in 0.02 M NaOH (42 μL). NaOH-treated cells were centrifuged at 3,220 × g for 1 min, and 8.4 μL of the supernatant (from each bin) was used for PCR amplification. PCRs (30 μL each) included 8.7 μL of double-distilled water, 6 μL of 5× Phusion buffer (Finnzyme), 3 μL of 2 mM dNTPs mix, 0.9 μL of 25 mM MgSO4, and 0.6 μL of Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Finnzyme). Bin-specific bar-coded reverse primers and one forward primer (SI Appendix, Table S4) were used in concentrations (stock) of 6 μM (1.5 μL) and 10 μM (0.9 μL), respectively (final concentration of 0.3 μM each). The PCR was performed with a preliminary melting step at 98 °C for 30 s and 28 cycles of 98 °C (10 s), 60 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (10 s). A closing extension step was carried out at 72 °C for 10 min. The PCR products from each bin were purified and eluted in a volume of 20 µL.

Pooling of PCR products and Sequencing.

DNA concentrations of PCR-amplified bins were measured in 96-well plates using a Tecan microplate reader (Infinite 200). Briefly, 1 μL from each PCR product was added to 199 μL of Qubit dsDNA HS assay mix (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were pooled from all bins to yield final quantities that were proportional to the original fraction of each sorting bin of the entire population (for fractions, see SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The DNA mix was concentrated and a sample containing ∼100 ng of DNA in a total volume of 30 μL was subjected to parallel DNA sequencing. Parallel sequencing was carried out using Applied Biosystems SOLiD sequencing (BC-MM50/35/10 kit; PN 4459182).

Fluorescence Measurements of Single-Strain Controls.

Cells from each sorted bin were subjected to serial dilutions, plated on six-well YPD agar plates, and incubated for 2 d at 30 °C. Four colonies were randomly selected from each bin (96 in total) and individually grown to stationary phase in 96-well plates containing YPD (180 μL/well). Next, we PCR amplified the DNA segment composed of the RPL8A promoter and the start of YFP from each clone (for primers, see SI Appendix, Table S3 K and L), using Dream Taq DNA Polymerase (Fermentas). The obtained PCR products were purified and subjected to Sanger sequencing. We then measured, for each isolated strain, the ratio between YFP and mCherry fluorescence. Briefly, individual strains were grown in synthetic complete (SC) medium (180 μL) for 2 d to saturation (30 °C), diluted in fresh SC in two replicates, and allowed to grow to midexponential phase (OD600 of 0.5–1). Flow cytometry analysis was performed on an LSRII (BD Biosciences) 96-well plate platform. To obtain a more homogenous cell population, cells were gated based on FSC-A vs. FSC-W and FSC-A vs. SSC-A profiles. Data were analyzed with a self-written MATLAB script. We note that the YFP-to-mCherry ratio of isolated variants in Fig. 1C (y axis) refers to measurements from one replica (the Pearson's R2 between replicates is 0.99). We additionally validated the obtained measurements by quantifying the YFP-to-mCherry ratio with a robotically operated microplate reader (Tecan Infinite F500), in three independent experiments, as previously described (37) (the Pearson's R2 between flow cytometry and plate reader measurements is 0.98).

Quantification of Protein Abundance.

(i) For each sorted bin, we first computed the average YFP-to-mCherry ratio of the cells that were sorted into that bin. (ii) We then mapped each sequencing read both to a specific variant and to a specific expression bin (using our bin-specific bar codes; SI Appendix, Method S1). Each such read added one count to an entry of a matrix that describes how all sequence variants are distributed across all expression bins. In this matrix, each row represents a single sequence variant and each column represents an expression bin. This matrix was further processed according to the following steps: (a) we normalized the sum of reads of each bin (column) to 1, (b) we scaled (multiplied) each bin (column) according to its fraction of the entire population (fractions are listed in SI Appendix, Fig. S1), and (c) we normalized the sum of each sequence variant (row) to 1. After this step, each row represented the distribution of cells that contained the sequence variant over all sorted expression bins. To reduce experimental noise, bins at the tails of each variant's distribution that had a small number of reads were set to zero (removing at most 5% of each variant's reads). (iii) Finally, we used the normalized matrix to obtain a measure of mean protein abundance according to the following formula:  , where

, where  is the mean protein abundance of the ith sequence variant,

is the mean protein abundance of the ith sequence variant,  is the mean YFP-to-mCherry ratio of the jth bin (as measured by flow cytometry), and

is the mean YFP-to-mCherry ratio of the jth bin (as measured by flow cytometry), and  is the fraction of normalized sequence reads of the ith variant that mapped to the jth bin.

is the fraction of normalized sequence reads of the ith variant that mapped to the jth bin.

Transcriptional Start Site Mapping.

To experimentally determine the transcriptional start site of the RPL8Apromoter-YFP strain, we used the Cap-Switching 5′-RACE method (71). Briefly, cDNA was generated from total RNA using a YFP-specific biotinylated primer (5′-/5BiosG/ACCGTAAGTAGCATCACCTTCA-3′) and the CapFinder primer (5′-TGGTTGCCATAAGCGGATCATCGGGAGGAGAAACGGG-3′). cDNA was purified using Invitrogen M-280 Dynabeads. The cDNA and beads were resuspended in 200 μL of Tris⋅HCl at pH 8.0 and were then used (0.5 μL) in a 50-μL PCR with the forward U0 primer (5′-TGGTTGCCATAAGCGGATC-3′) and a YFP-specific reverse primer (5′-GGGACAACACCAGTGAATAATTC-3′; internal to the biotinylated primer). Sanger sequencing showed that RPL8A has a 17-bp–long 5′-UTR sequence (aaaacaactaattcgaaATG; 5′-UTR in bold).

Quantification of Relative mRNA Abundance.

We measured mRNA abundance for 15 sequence variants (14 mutants and wild type) that span a 4.5-fold range of protein levels. We selected the strains from a G/C-rich validation pool with mutations between positions −6 to −1 (Fig. 6, Right). Total RNA was purified using a MasterPure purification kit (epicenter) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA samples (1 µg each) were subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and oligo-dT. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed by using Applied Biosystems real-time PCR instrument (StepOnePlus). qPCR primers were designed to yield YFP (the target) and mCherry (the endogenous control) products of 106- and 135- bp, respectively (for primers, see SI Appendix, Table S3 M–P). Samples were run in duplicates and included 2 μL of cDNA (∼0.5 ng each), 10 µL of KAPA SYBR FAST Master Mix, 1 µL of primers (YFP or mCherry, from a 10 μM stock), and 6 µL of nuclease-free water in a final volume of 20 μL. The qPCR was carried out at 95 °C for 10 min with 45 cycles of 95 °C (15 s), 60 °C (30 s), and 72 °C (10 s). We used the standard curve method to quantify relative mRNA abundance, expressed as the ratio between YFP mRNA and mCherry mRNA. R2 values for both standard curves (YFP and mCherry) were 0.999. Nonspecific products were not observed (melting-curve analysis). Sequences of selected variants (positions −6 to −1): AGGTTG, ATTCTT, CAAGCG, CCCAAC, CGAGGT, CGGGAC, CTTGTG, GACGGG, GCAGGG, GCCTAC, GCGAGG, GGCCGC, GTGCTG, TTCCTG, and TTCGAA (wild type).

Statistical Analysis and Visualization.

Statistical and data analyses were conducted using the R statistical environment (ref. 72; R, version 3.0.0). Additional analyses, using MATLAB (R2012b) or the Vienna RNA package (version 1.6), are reported throughout the text and SI Appendix. Plots were drawn using the R ggplot2 package (73).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Lubliner for performing nucleosome occupancy predictions and Y. Kalma for experimental guidance. This work was supported by grant R01-HG004361 from the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) to E. Segal.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Dataset S1 contains the sequences of 2,041 variants with their protein abundance levels. Dataset S1 can be downloaded from the Weizmann Institute of Science at http://genie.weizmann.ac.il/pubs/5utr2013/.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1222534110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Melnikov A, et al. Systematic dissection and optimization of inducible enhancers in human cells using a massively parallel reporter assay. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(3):271–277. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patwardhan RP, et al. Massively parallel functional dissection of mammalian enhancers in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(3):265–270. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharon E, et al. Inferring gene regulatory logic from high-throughput measurements of thousands of systematically designed promoters. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(6):521–530. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raveh-Sadka T, et al. Manipulating nucleosome disfavoring sequences allows fine-tune regulation of gene expression in yeast. Nat Genet. 2012;44(7):743–750. doi: 10.1038/ng.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ingolia NT, Ghaemmaghami S, Newman JRS, Weissman JS. Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science. 2009;324(5924):218–223. doi: 10.1126/science.1168978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatterjee S, Pal JK. Role of 5′- and 3′-untranslated regions of mRNAs in human diseases. Biol Cell. 2009;101(5):251–262. doi: 10.1042/BC20080104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mignone F, Gissi C, Liuni S, Pesole G. 2002. Untranslated regions of mRNAs. Genome Biol 3(3):reviews0004.1–0004.10.

- 8.Barrett LW, Fletcher S, Wilton SD. Regulation of eukaryotic gene expression by the untranslated gene regions and other non-coding elements. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2012;69(21):3613–3634. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0990-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozak M. Regulation of translation via mRNA structure in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Gene. 2005;361(0):13–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuller T, Ruppin E, Kupiec M. Properties of untranslated regions of the S. cerevisiae genome. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:391. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Araujo PR, et al. Before it gets started: Regulating translation at the 5′ UTR. Comp Funct Genomics. 2012;2012:475731. doi: 10.1155/2012/475731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawless C, et al. Upstream sequence elements direct post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression under stress conditions in yeast. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell SF, et al. The 5′-7-methylguanosine cap on eukaryotic mRNAs serves both to stimulate canonical translation initiation and to block an alternative pathway. Mol Cell. 2010;39(6):950–962. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gingold H, Pilpel Y. Determinants of translation efficiency and accuracy. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:481. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dikstein R. Transcription and translation in a package deal: The TISU paradigm. Gene. 2012;491(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kozak M. Point mutations define a sequence flanking the AUG initiator codon that modulates translation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Cell. 1986;44(2):283–292. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90762-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kochetov AV. Alternative translation start sites and hidden coding potential of eukaryotic mRNAs. Bioessays. 2008;30(7):683–691. doi: 10.1002/bies.20771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hood HM, Neafsey DE, Galagan J, Sachs MS. Evolutionary roles of upstream open reading frames in mediating gene regulation in fungi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:385–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xia X, Holcik M. Strong eukaryotic IRESs have weak secondary structure. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashita R, et al. Comprehensive detection of human terminal oligo-pyrimidine (TOP) genes and analysis of their characteristics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(11):3707–3715. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickering BM, Willis AE. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bugaut A, Balasubramanian S. 5′-UTR RNA G-quadruplexes: Translation regulation and targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(11):4727–4741. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun Y, Adesanya TM, Mitra RD. A systematic study of gene expression variation at single-nucleotide resolution reveals widespread regulatory roles for uAUGs. Genome Res. 2012;22(6):1089–1097. doi: 10.1101/gr.117366.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumari S, Bugaut A, Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S. An RNA G-quadruplex in the 5′ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene modulates translation. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(4):218–221. doi: 10.1038/nchembio864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert WV, Zhou K, Butler TK, Doudna JA. Cap-independent translation is required for starvation-induced differentiation in yeast. Science. 2007;317(5842):1224–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.1144467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozak M. Influences of mRNA secondary structure on initiation by eukaryotic ribosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(9):2850–2854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner M, Feller A, Messenguy F, Piérard A. The leader peptide of yeast gene CPA1 is essential for the translational repression of its expression. Cell. 1987;49(6):805–813. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vattem KM, Wek RC. Reinitiation involving upstream ORFs regulates ATF4 mRNA translation in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(31):11269–11274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400541101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang XQ, Rothnagel JA. 5′-untranslated regions with multiple upstream AUG codons can support low-level translation via leaky scanning and reinitiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(4):1382–1391. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medenbach J, Seiler M, Hentze MW. Translational control via protein-regulated upstream open reading frames. Cell. 2011;145(6):902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Calvo SE, Pagliarini DJ, Mootha VK. Upstream open reading frames cause widespread reduction of protein expression and are polymorphic among humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(18):7507–7512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810916106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Z, Dietrich FS. Identification and characterization of upstream open reading frames (uORF) in the 5′ untranslated regions (UTR) of genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet. 2005;48(2):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Looman AC, Kuivenhoven JA. Influence of the three nucleotides upstream of the initiation codon on expression of the Escherichia coli lacZ gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(18):4268–4271. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.18.4268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveira CC, van den Heuvel JJ, McCarthy JE. Inhibition of translational initiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by secondary structure: The roles of the stability and position of stem-loops in the mRNA leader. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9(3):521–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sagliocco FA, et al. The influence of 5′-secondary structures upon ribosome binding to mRNA during translation in yeast. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(35):26522–26530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yun DF, Laz TM, Clements JM, Sherman F. mRNA sequences influencing translation and the selection of AUG initiator codons in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19(6):1225–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeevi D, et al. Compensation for differences in gene copy number among yeast ribosomal proteins is encoded within their promoters. Genome Res. 2011;21(12):2114–2128. doi: 10.1101/gr.119669.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muhlrad D, Parker R. Recognition of yeast mRNAs as “nonsense containing” leads to both inhibition of mRNA translation and mRNA degradation: Implications for the control of mRNA decapping. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(11):3971–3978. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwartz DC, Parker R. Mutations in translation initiation factors lead to increased rates of deadenylation and decapping of mRNAs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(8):5247–5256. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barnes CA. Upf1 and Upf2 proteins mediate normal yeast mRNA degradation when translation initiation is limited. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(10):2433–2441. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.10.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baim SB, Sherman F. mRNA structures influencing translation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8(4):1591–1601. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.4.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ringnér M, Krogh M. Folding free energies of 5′-UTRs impact post-transcriptional regulation on a genomic scale in yeast. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1(7):e72. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kertesz M, et al. Genome-wide measurement of RNA secondary structure in yeast. Nature. 2010;467(7311):103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature09322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cigan AM, Pabich EK, Donahue TF. Mutational analysis of the HIS4 translational initiator region in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8(7):2964–2975. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.7.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vega Laso MR, et al. Inhibition of translational initiation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a function of the stability and position of hairpin structures in the mRNA leader. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(9):6453–6462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zuker M. Calculating nucleic acid secondary structure. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10(3):303–310. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mathews DH, Moss WN, Turner DH. Folding and finding RNA secondary structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(12):a003665. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marek MS, Johnson-Buck A, Walter NG. The shape-shifting quasispecies of RNA: One sequence, many functional folds. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2011;13(24):11524–11537. doi: 10.1039/c1cp20576e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mathews DH. Revolutions in RNA secondary structure prediction. J Mol Biol. 2006;359(3):526–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reeder J, Höchsmann M, Rehmsmeier M, Voss B, Giegerich R. Beyond Mfold: Recent advances in RNA bioinformatics. J Biotechnol. 2006;124(1):41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2006.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hofacker I, et al. Fast folding and comparison of RNA secondary structures. Monatsh Chem. 1994;125:167–188. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meijer HA, Thomas AA. Control of eukaryotic protein synthesis by upstream open reading frames in the 5′-untranslated region of an mRNA. Biochem J. 2002;367(Pt 1):1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Slusher LB, Gillman EC, Martin NC, Hopper AK. mRNA leader length and initiation codon context determine alternative AUG selection for the yeast gene MOD5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(21):9789–9793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McLeod AI, Xu C. 2011. Bestglm: Best subset GLM. R package, version 0.33. Available at http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=bestglm. Accessed June 16, 2013.

- 55.Kozak M. At least six nucleotides preceding the AUG initiator codon enhance translation in mammalian cells. J Mol Biol. 1987;196(4):947–950. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pisarev AV, et al. Specific functional interactions of nucleotides at key −3 and +4 positions flanking the initiation codon with components of the mammalian 48S translation initiation complex. Genes Dev. 2006;20(5):624–636. doi: 10.1101/gad.1397906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kozak M. Structural features in eukaryotic mRNAs that modulate the initiation of translation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(30):19867–19870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McCarthy JEG. Posttranscriptional control of gene expression in yeast. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62(4):1492–1553. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1492-1553.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parsyan A, et al. mRNA helicases: The tacticians of translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(4):235–245. doi: 10.1038/nrm3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Robbins-Pianka A, Rice MD, Weir MP. The mRNA landscape at yeast translation initiation sites. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(21):2651–2655. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tuller T, Waldman YY, Kupiec M, Ruppin E. Translation efficiency is determined by both codon bias and folding energy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3645–3650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909910107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kozak M. The scanning model for translation: An update. J Cell Biol. 1989;108(2):229–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Churbanov A, Rogozin IB, Babenko VN, Ali H, Koonin EV. Evolutionary conservation suggests a regulatory function of AUG triplets in 5′-UTRs of eukaryotic genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(17):5512–5520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muhlrad D, Decker CJ, Parker R. Turnover mechanisms of the stable yeast PGK1 mRNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(4):2145–2156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.4.2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oliveira CC, McCarthy JE. The relationship between eukaryotic translation and mRNA stability. A short upstream open reading frame strongly inhibits translational initiation and greatly accelerates mRNA degradation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(15):8936–8943. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.LaGrandeur T, Parker R. The cis acting sequences responsible for the differential decay of the unstable MFA2 and stable PGK1 transcripts in yeast include the context of the translational start codon. RNA. 1999;5(3):420–433. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Linshiz G, et al. Recursive construction of perfect DNA molecules from imperfect oligonucleotides. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:191. doi: 10.1038/msb.2008.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Microtiter plate transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(1):5–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Otsuka C, et al. Use of yeast transformation by oligonucleotides to study DNA lesion bypass in vivo. Mutat Res. 2002;502(1-2):53–60. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kow YW, Bao G, Reeves JW, Jinks-Robertson S, Crouse GF. Oligonucleotide transformation of yeast reveals mismatch repair complexes to be differentially active on DNA replication strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(27):11352–11357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704695104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frohman MA. 2006. Cap-switching RACE. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2006(1):pdb.prot4133.

- 72.R Core Team 2013. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna). Available at www.R-project.org/. Accessed June 16, 2013.

- 73.Wickham H. 2009. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, New York)

- 74.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.