Abstract

Chloroplasts and mitochondria descended from bacterial ancestors, but the dating of these primary endosymbiosis events remains very uncertain, despite their importance for our understanding of the evolution of both bacteria and eukaryotes. All phylogenetic dating in the Proterozoic and before is difficult: Significant debates surround potential fossil calibration points based on the interpretation of the Precambrian microbial fossil record, and strict molecular clock methods cannot be expected to yield accurate dates over such vast timescales because of strong heterogeneity in rates. Even with more sophisticated relaxed-clock analyses, nodes that are distant from fossil calibrations will have a very high uncertainty in dating. However, endosymbiosis events and gene duplications provide some additional information that has never been exploited in dating; namely, that certain nodes on a gene tree must represent the same events, and thus must have the same or very similar dates, even if the exact date is uncertain. We devised techniques to exploit this information: cross-calibration, in which node date calibrations are reused across a phylogeny, and cross-bracing, in which node date calibrations are formally linked in a hierarchical Bayesian model. We apply these methods to proteins with ancient duplications that have remained associated and originated from plastid and mitochondrial endosymbionts: the α and β subunits of ATP synthase and its relatives, and the elongation factor thermo unstable. The methods yield reductions in dating uncertainty of 14–26% while only using date calibrations derived from phylogenetically unambiguous Phanerozoic fossils of multicellular plants and animals. Our results suggest that primary plastid endosymbiosis occurred ∼900 Mya and mitochondrial endosymbiosis occurred ∼1,200 Mya.

Biologists have often attempted to estimate when key events on the Tree of Life (TOL) occurred. This approach has experienced substantial success when used for dating events in the Phanerozoic [543–0 Mya], but when trying to date deep events on the TOL, such as endosymbiosis events in the Proterozoic (2,500–543 Mya), it becomes increasingly difficult to find reliable fossil calibrations. Molecular dating analysis is performed by calibrating a phylogenetic tree with known dates, usually based on fossil calibration points. Ideally, the dating of phylogenetic events deep in the Precambrian would be well-constrained by fossil calibrations; however, many of the fossil calibrations that have been proposed for Precambrian microorganisms have been controversial because of the difficulty in identifying the clade memberships of these groups.

Although the timing of the origin of eukaryotes is heavily studied and debated, the endosymbiosis events involved in the origin and diversification of many eukaryotic lineages are arguably equally contentious. Fossil records for eukaryotes have been claimed up to 2,700 Mya (1), and others have speculated that “Snowball Earth” events postponed the origin and/or diversification of eukaryotes until as recently as 850–580 Mya (2–4). Interpretation of microfossils is inherently difficult because of difficult preservation, taphonomic, and interpretive issues (e.g., refs. 5 and 6). A less-recognized problem is that fossil calibrations are best done via a phylogenetic analysis of characters, which allows objective placement of fossils on a tree and measurement of the uncertainty of this placement (7). General similarity to an extant group is an insufficient basis for using a fossil as a date calibration: Characters must place the fossil in the crown group rather than a stem group [which is sometimes an insufficiently appreciated distinction (8)] to constrain the date of the last common ancestor of the crown group (7). However, microfossils typically have a very small number of diagnosable characters (9), thus running the risk of misclassification, especially as a result of homoplasy.

Chemical biomarkers, another strategy that is much used to date Precambrian lineages, are equally problematic because fundamentally, each biomarker constitutes a single character unassociated with other fossil characters. To be used for dating, it must be assumed that the character only evolved once and is unique to one extant clade, but this is not always a safe assumption, as demonstrated by the recent finding that the methylhopane biomarker, once used specifically for cyanobacteria (10), can also be found in a broad range of other bacterial phyla (11, 12).

Apart from uncertainty in fossil calibrations, molecular dating imposes additional uncertainties. Early attempts at molecular dating, starting with Zuckerkandl and Pauling (13), assumed a strict molecular clock to date divergences. Subsequent attempts to date deep nodes in the TOL have given wildly varying results, many of which clearly do not agree with fossil, let alone geological, histories primarily because of rate variation not accounted for by strict clock models (14, 15). More sophisticated models allow for rate variation, and thus provide a more realistic assessment of uncertainty. However, the uncertainty that results can be vast, as the origin of crown eukaryotes has been dated between 3,970 and 1,100 Mya throughout various studies (16).

Uncorrelated relaxed-clock methods, available in Bayesian phylogenetic dating methods, allow the rate of evolution on each branch to be drawn from a common distribution, the parameters of which are themselves estimated during the analysis. One advantage of Bayesian analysis is that it takes into account diverse sources of known prior information. Another technique used in several studies relies on the concatenation of protein sequences to increase phylogenetic signal for estimations of deeply rooted events. However, this strategy does nothing to remedy the problem of scarce and ambiguous fossil calibrations for deep nodes.

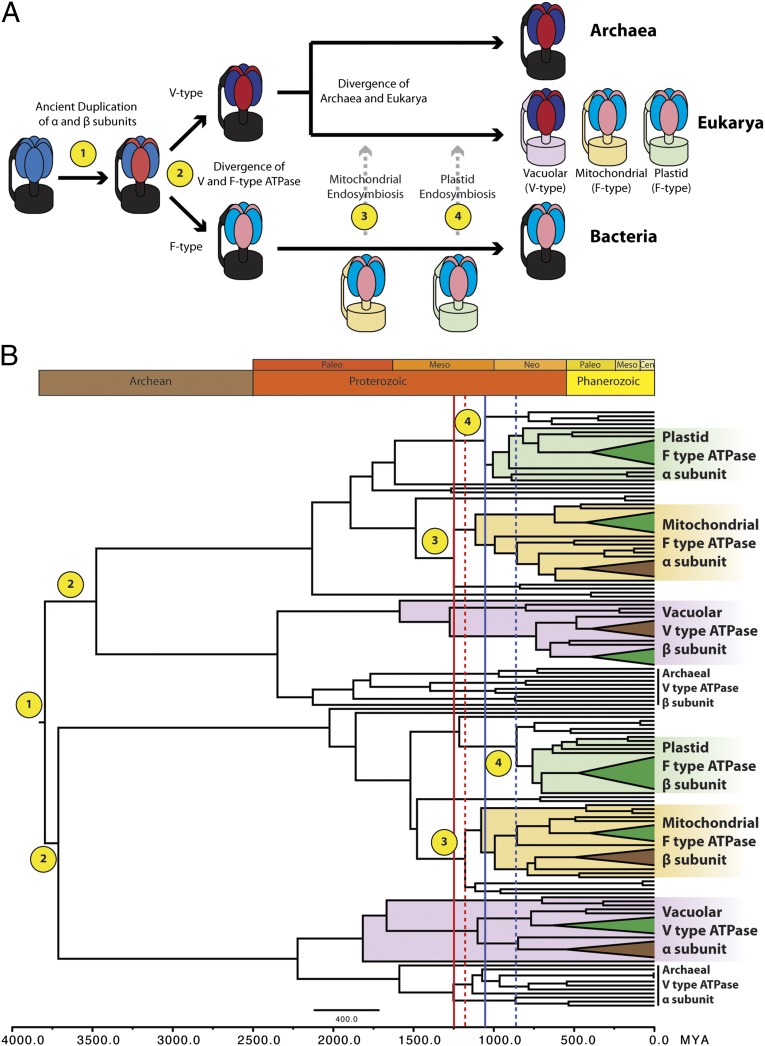

Given the difficulty of dating deep nodes in the Proterozoic as well as the lack of studies dating Precambrian events with newer methods, it is useful to explore possible improvements in relaxed clock analyses. We hypothesize that better estimates of rates and rate variability, and thus better estimates of dates and dating uncertainty, would occur if more prior information and more date calibrations were input into analyses. Date calibrations are typically scarce, but we suggest they can be multiplied in cases in which one or more ancient duplications has been universally or near-universally inherited. In such cases, a single fossil calibration can date not just one node in the tree, but several. An example where this is possible is the protein family of ATP synthases (ATPases) found within the F1 portion of the F1Fo-ATPase system and its relatives, the vacuolar V1Vo-ATPases and archaeal A1Ao-ATPases (17). The α and β subunits of F1-ATPase duplicated before the last universal common ancestor (18, 19) and have been almost universally inherited as a pair since then (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, the core function of the ATPases in energy production has resulted in high conservation and a lower probability of extreme rate variation.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary history of the ATPase α- and β-subunits and divergence time estimates inferred from cross-calibration analysis. (A) Cartoon schematic that demonstrates the common origin of both α- and β-subunits, followed by both the mitochondrial and plastid endosymbiosis events, all of which enable the use of cross-calibration methods. Evolutionary events of interest are numbered and labeled onto the subsequent chronogram generated from cross-calibration of the α- and β-subunits. (B) Time-scale phylogeny generated from Bayesian analysis of cross-calibrated ATPase α- and β-subunits (SI Appendix, Fig. SB). Blue lines denote the dates estimated for the primary plastid endosymbiosis event. Red lines denote the dates estimated for mitochondrial endosymbiosis. Solid lines represent dates that were inferred from the α-subunit subsection of the phylogeny; dashed lines were inferred from the β-subunit subclade.

The fact that mitochondria and plastids have retained these ATPase proteins (whether they are encoded by the organellar or the nuclear genome) means that many homologs may coexist in a single organism. For example, plant genomes contain six homologous copies of this ATPase subunit: both homologous α and β subunits targeted to the mitochondria, chloroplasts, and vacuoles. Therefore, a single plant fossil, which calibrates the date of the divergence of monocots and eudicots, can actually provide calibration dates for up to six nodes on the ATPase α and β subunit phylogeny. We propose two methods for use of these calibrations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In the first strategy, which we dub cross-calibration, the date calibrations are simply reused at each node, and the dates of these nodes are subsequently sampled independently during the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) search. Cross-calibration is simple to implement but neglects the fact that nodes representing the same event should have the same date, even if that date is uncertain. We therefore also propose a second strategy, cross-bracing, in which the dates of calibrated nodes representing the same speciation events are linked, and thus covary during MCMC sampling. This is a more accurate representation of our prior knowledge that a single speciation event led to the simultaneous divergence of the nuclear, mitochondrial, plastid ATPase genes (although some variability could be caused by lineage sorting processes).

Iwabe et al. (18) and Gogarten et al. (19) attempted to use ancient duplicated genes in inferring distant evolutionary relationships between the three domains of life, using α and β subunits of ATPase and elongation factor thermo unstable (Ef-Tu). Their rooting of the TOL has been much debated because of problems with saturation of phylogenetic signal at the very deepest nodes of the tree (20) and the possible breakdown of the tree concept itself, when it comes to the origin and rooting of the three domains (21). Because of these issues, in this study, we do not attempt to revisit the question of the root of the TOL or its date; instead, we focus on the much more recent, but still Precambrian, endosymbiosis events that gave rise to mitochondria and chloroplasts. The root and the date of the TOL will be treated as highly uncertain nuisance parameters over which our Bayesian analysis will integrate, because of the numerous hazards involved in extrapolative dating at the base of the TOL. These hazards include, but are not limited to, horizontal gene transfer for some ATPases (22). In this study, we augment a standard Bayesian relaxed molecular clock approach with our new cross-calibration and cross-bracing methods and show the influence of these methods on the estimates and precision of dates for major endosymbiosis events within the Eukaryotes.

Results and Discussion

BEAST Analyses.

To measure the effect of cross-calibration and cross-bracing on an overall dating analysis and the effect of different amounts of prior dating information, nine separate relaxed-clock dating analyses using ATPase sequences (SI Appendix, Table S1) were performed using the program BEAST (23, 24). Six analyses used only α-subunit sequences, each of which was cross-calibrated using some or all of the available node date calibrations (α-cross-calibrated); one analysis conducted cross-calibration with all node date calibrations, using only β-subunit sequences (β-cross-calibrated); one analysis conducted cross-calibration with all node date calibrations applied simultaneously to a tree containing all α- and β-subunits (α/β cross-calibrated); and the last analysis used all calibrations and all α- and β-subunits, but used the cross-bracing approach to link node dates (α/β cross-braced). Consensus trees from these analyses are shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S6.

Effect of Cross-Calibration Methods on Age, Rates, and Uncertainty.

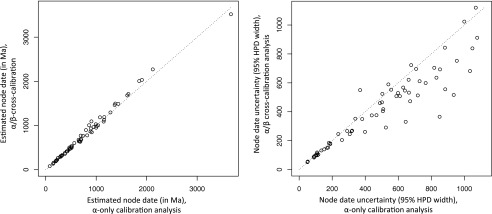

The change in precision of date estimates between calibration methods was measured by comparing the width of the 95% highest posterior density of node age between analyses (only nodes in the α-subunit portion of the tree, which existed in all analyses, were compared). The null hypothesis, indicating no difference, predicts a 1:1 relationship in node uncertainty between methods. Regression was used to test for statistically significant departure from a 1:1 relationship. The increased amount of dating information incorporated into the α/β-cross-calibrated analysis and α/β-cross-braced analysis yielded a decrease in uncertainty (14–26%) for both the α/β-cross-calibrated and α/β-cross-braced runs (Fig. 2; SI Appendix, Table S2). This was a significant result (P value always < 0.0025; the F-test was used for all regressions). There was no significant difference in uncertainty when comparing α/β-cross-calibrated and α/β-cross-braced runs (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S7).

Fig. 2.

Cross-calibration decreases dating uncertainty. Comparison (regression analysis) of estimates of node age in F1-ATPase proteins under BEAST runs with two different calibration methods; namely, dated calibrations only within the α-subunit gene tree (α-cross-calibrated) (x-axis) and cross-calibration across the ATPase phylogeny of α- and β-subunits (α/β-cross-calibrated) (y-axis). Each dot represents a corresponding node-date estimate from the α-portion of the tree. The left panel shows the mean estimates of node age, which are not statistically significantly affected by calibration strategy (P = 0.145, F-test). The right panel compares precisions between the two analyses (the width of the 95% highest posterior density on node age). Average uncertainty in node age estimates is decreased by about 22% by the cross-calibration strategy, which is a statistically significant result (P = 2.96e-07, F-test).

Branch rates were also estimated with more precision using the cross-calibration and cross-bracing methods, in which regressions indicate a 42–57% decrease in uncertainty in rate for the α/β-cross-calibrated tree compared with α- and β- cross-calibrated trees (SI Appendix, Table S2). Some of this decrease is because the mean rates, as estimated by α/β-cross-calibration, were also on average slightly lower (6–12%) than in α-only or β-only analyses, and the mean rate and the uncertainty in rate are strongly correlated. However, the effect remains when the coefficients of variation (CVs) in rate estimates were observed (a 14–29% reduction in uncertainty is seen). Further examination of the effects of cross-calibration and cross-bracing on node age and branch rate uncertainty is elaborated in SI Appendix, Supplemental Analysis of BEAST Runs.

The α/β-cross-braced run produced node dates that averaged about 5% younger than the corresponding node dates in the α/β-cross-calibrated, α-cross-calibrated, and β-cross-calibrated analyses. The differences were statistically significant (α-cross-calibrated, P = 2.97E-06; β-cross-calibrated, P = 1.19E-05; α/β-cross-calibrated, P = 5.75E-08). In addition, the intercept term was significantly negative (α-cross-calibrated, P = 4E-06; β-cross-calibrated, P = 0.018; α/β-cross-calibrated, P = 8.64E-12), indicating that in addition to the 5% average difference, cross-braced node ages tended to be lower by a fixed amount of 37–65 My (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S8).

To further investigate the effect of reducing the number of prior calibration dates, the α-cross-calibrated analysis using all node calibrations was compared with the α-cross-calibrated analyses using fewer calibration priors (SI Appendix, Table S3). Uncertainty in node age was not dramatically different between the α-cross-calibrated data set with all date calibrations and subsets of these calibrations (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). However, when the heteroscedasticity between node age and uncertainty is accounted for by calculating the CV, comparison of CVs showed a significant decrease in CV (23–44%) when all calibration nodes were used, suggesting that increasing the number of calibration points decreases relative uncertainty in the estimates of node age in α-only analyses. Moreover, branch rate uncertainty significantly increased for runs with fewer calibrations except run 5 (SI Appendix, Table S4 and Fig. S9). Further comparisons of all runs, including the α/β-cross-calibrated and α/β-cross-braced runs, are summarized in SI Appendix.

Dating Symbiosis Events: ATPases.

Because the α/β-cross-calibrated and α/β-cross-braced runs were shown to decrease rate and age uncertainty, but neither method yielded significantly more robust results when compared with the other, for simplicity, we will henceforth refer to only the α/β-cross-calibrated analysis (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Divergence-time estimates (in millions of years ago) for major endosymbiosis or domain divergence events

| Divergence event and cross-calibrated ATPase α/β subunits | Cross-calibrated elongation factor Tu |

| Plastid endosymbiosis | |

| α subunit: 1,055 (1,278-913) | 1,188 (896–1,613) |

| β subunit: 857 (1,098-720) | |

| Mitochondrial endosymbiosis | |

| α subunit: 1,248 (1,838-1,217) | 1,196 (909–1,551) |

| β subunit: 1,176 (1,524-1,053) |

Dates in parentheses denote the 95% highest posterior density.

The timing of plastid endosymbiosis has been as contentious as dating the rise of eukaryotes. The hypothesis that cyanobacteria are responsible for the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) has led to many studies extrapolating divergence points for a broad range of uses, from dating endosymbiosis events to events of multicellularity (25–28). However, this approach assumes that all crown cyanobacterial lineages emerged at the time of the GOE (29). Our study was aimed at dating the plastid endosymbiosis event agnostic of the GOE, microfossils, or biomarker data, and instead calibrated only by well-accepted Phanerozoic divergence events. Our cross-calibrated analysis estimates primary plastid endosymbiosis and the birth of the Archaeplastida lineage at 857 and 1,055 Mya (857/1,055 Mya), based on F-type α and β subunits of the tree, respectively. These dates are remarkably similar to the dates estimated by Douzery et al., who predicted that the plastid endosymbiosis occurred between 825 and 1,162 Mya, using 129 concatenated protein sequences, as well as to other previous large-scale and broadly sampled molecular clock studies (30).

Although younger than other predicted estimated divergence dates (31, 32), our dates present a plausible scenario for the changing geochemical properties of the ocean. The rise of photosynthetic eukaryotes through the acquisition of plastids ∼900 Mya most likely dramatically added to primary productivity in the sea, which may have significantly contributed to the conversion of euxinic oceans during the Neoproterozoic to its oxygenated state, which persists today (33). This is further supported by the dramatic increase in atmospheric oxygen between 1,005 and 640 Mya (34). Our analysis suggests that the diversification of Archaeplastida occurred near or during the time of the transformation of euxinic conditions to its modern-day properties and that there was very little lag time between the origin and diversification of photosynthetic eukaryotes.

Numerous phylogenetic studies have placed the plastid endosymbiosis event near the base of the extant cyanobacterial tree (35–37). Assuming that crown cyanobacteria were responsible for the GOE, this would place the plastid endosymbiosis near the time of the GOE. This is in contradiction to our study and many concatenated, multiloci molecular clock studies (30–32), which have conservatively dated the origin of crown eukaryotes well after 2 Gya. It is therefore difficult to reconcile these dates, as plastid endosymbiosis could not have occurred before the origin of eukaryotes. Moreover, all bacterial phyla in our analysis (including cyanobacteria) have diversified after the GOE, suggesting that extant crown cyanobacteria were not responsible for the GOE. Our findings are in contrast with those of Schirrmeister et al. (28) who date the origin of crown cyanobacteria before the GOE. These findings are attributable to their assignment of ancient (>2 Gya) cyanobacterial-like fossils to extant clades, despite the possibility that the few available morphological characters may be homoplastic and may have evolved several times convergently. Assuming the GOE was of biological origin, our results imply that crown cyanobacteria may not have been responsible for the GOE. However, this does not rule out the possibility of its origin from stem group cyanobacteria, which may have gone extinct during the major transition from euxinic to oxic oceans (33). In line with this idea, the phylogeny of crown cyanobacteria has been interpreted as a large radiation event (35, 37), which may have occurred after the extinction of stem groups and the adaption of crown lineages to the changing ocean surfaces. These extinct lineages may be the Proterozoic cyanobacterial-like fossils described in previous studies (27, 38–40) and used as fossil calibrations by Schirrmeister et al. (28). Our analysis reflects the controversial nature of contrasting molecular and fossil studies, and thus emphasizes the need to improve existing phylogenetic techniques to more accurately examine the dating of these Precambrian events.

Our cross-calibration analysis dates the rise of modern-day mitochondria through the endosymbiosis of an α-proteobacterium to be 1,176/1,248 Mya. Although the vacuolar subclades display an earlier date for the last common ancestor of eukaryotes, our interest was in dating the actual divergence between bacteria and mitochondria; other dates in the analyses were treated as nuisance variables. Given that the most recent common ancestor of eukaryotes most likely is younger than the mitochondrial endosymbiosis, we recognize the contradiction between the dates in the two parts of the tree, which is probably caused by fewer calibration points and an accelerated rate of evolution at the base of the V-ATPase tree. However, the only methodological remedy would be to use the cross-bracing technique on those nodes we want to infer, whereas in this study we are examining the potential of cross-linking date calibration nodes. Cross-bracing nodes with dates that are to be inferred rather than used as calibrations should be explored in the future, but issues of extended autocorrelation in the posterior distribution and of low estimated sample size become much more pressing if the nodes targeted for inference are cross-braced.

Parfrey et al. estimate the last common eukaryotic ancestor to be more than 1,600 Mya (31), which is notably older than our analysis. However, when excluding Proterozoic fossil calibrations, they observed shifts in all major clades to be 300 My younger, which is nearly comparable with our results. The effects of excluding Proterozoic microfossil calibrations may explain the incongruence in estimated dates between studies; however, for the purposes of our study, our focus on cross-calibration methods was to increase the amount of dating prior information with younger and less controversial Phanerozoic fossils. Finally, our analysis does not find evidence for the hypothesis that crown eukaryotes originated ∼850 Mya and postdate the hypothesized Snowball Earth.

Although earlier Proterozoic and Archean events are not the primary focus of this study, and uncertainties this far back are large, we observe long branches leading to the Eukarya/Archaea split, followed by a radiation of extant Eukarya/Archaea (V-type ATPases) and Eubacteria (F-type ATPases) around 2,000–2,500 Mya. Because the rise in molecular oxygen in the atmosphere occurred around the same time, it is tempting to speculate that this synchronized radiation of extant life across all three kingdoms was somehow facilitated by the GOE and that all extant life-forms are the descendants of lineages that most successfully adapted to the changing biogeochemistry in ocean surfaces.

Dating Symbiosis Events: Ef-Tu.

Because there may be inherent biases between particular markers used for any phylogenetic analysis, we extended our cross-calibration study to Ef-Tu because of its similar evolutionary history to ATPases, which allows for cross-calibration. Bacterial Ef-Tu and its eukaryotic/archaeal homolog, translation elongation factor 1α (EF-1α), allow for entry of aminoacyl tRNAs into the ribosome, and thus are considered conserved, slowly evolving proteins, decreasing the chance of saturation and high rate variability. The dates estimated from the Ef-Tu chronogram were similar to the dates attained from the ATPase analysis: 1,188 Mya for plastid endosymbiosis and1,196 Mya for mitochondrial endosymbiosis (Table 1; SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Estimations of deeper nodes such as the split between Archaea and Eukarya (1,528 Mya) differed from the ATPase results by almost 800 Mya. This is not surprising, as many of these nodes may inherently be difficult to estimate because of the lack of signal from a saturation of amino acid substitutions (20).

Conclusion

Cross-calibration and cross-bracing, using duplication or endosymbiosis events, provide useful advantages compared with conventional molecular dating. First, they increase the sampling and sequence data used, which improves accuracy of the dating of internal nodes (41, 42). Second, by increasing the number of sequences that are cross-calibrated, they decrease the chance of artifacts being introduced by underestimated rate variation. Just as there are multiple calibration points for a given divergence event, a divergence event will be estimated multiple times on the tree. Third, the increase in calibration points allows for the use of more well-accepted calibration points closer to the tips of the tree, rather than relying on older and more contentious microscopic, Precambrian fossils.

The flexibility of the BEAST XML input allows unconventional strategies such as ours to be used. However, the cross-bracing technique could be improved. Future efforts should develop algorithms that redesign the MCMC tree search such that nodes with linked dates can be specified and linked nodes can be allowed to share identical dates during sampling. This should eliminate all or most of the need for longer runs to account for increased autocorrelation in the posterior sample. The cross-bracing strategy might also improve inference in another way: nodes with dates that are unknown, but that represent the same event, could be linked, as we have done here for calibration nodes. For example, the nodes representing the divergence of the chloroplasts should have the same or nearly the same date between the α- and β- subunit gene trees, instead of two individually estimated dates. Further refinements could include linking rates for genes when they are inhabiting the same species, which would avoid the assumption, made here by necessity, that rates and rate variation are independent across the tree.

It is important to note that our approach is different from the common technique of concatenation of gene duplicates into a larger alignment. For example, if a researcher were only interested in dating nodes within plants, to increase signal they might concatenate the α- and β -subunit sequences from vacuolar, chloroplast, and mitochondrial ATPases. However, this conventional strategy would be useless when the goal is to date nodes in the gene tree that are not represented by nodes in the species tree; for example, the date of a gene duplication itself, or as in this study, the date of endosymbiosis events.

Although we observed similar dates between ATPase and Ef-Tu, it will be interesting to determine whether other molecular markers that have undergone duplications or endosymbiotic transfers and can be used in cross-calibration will also yield similar dates. Possible examples include aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (43), translation initiation factors (44), and phytochrome (45) data sets. Cross-calibration could also be extended to large concatenated data sets if all proteins display similar histories.

Regardless of the detailed method used, we argue that because of the difficulty in estimating the timing of Precambrian events, every possible source of information should be included. As we show here, this information is not merely found in the dates of fossil calibrations, it can also include linkages between nodes that represent the same speciation or duplication events. Information about the relative timing of events could also be included; for example, the origin of crown chloroplasts must equal or postdate the origin of crown eukaryotes. Hierarchical Bayesian models excel in the incorporation of such diverse sources of information and should be exploited wherever possible, along with other attempts to ameliorate dependence on controversial date calibrations based on ancient, microscopic fossils that are difficult to interpret and rigorously place on phylogenies.

Materials and Methods

Alignments.

ATPase α and β subunit and EF-Tu/1α protein sequences were all gathered from the Uniprot database and are listed in SI Appendix, Table S5. Sequences were chosen to cover a broad range of bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic phyla. Alignments were generated using the –maxiterate strategy in the MAFFT program (46).

Dating Programs.

Estimation of dated phylogenies was conducted with BEAST 1.7.3 (23, 24). BEAST XML input files were started using BEAUTi 1.7.3 (23, 24), but our novel calibration strategies, described below, required custom modifications to the XML code. The WAG model was chosen as the best-fitting amino acid substitution matrix available in BEAST, based on ProtTest analysis for all data sets (47). Production of the final BEAST XML files for the different combinations of data sets and calibration methods was done via custom programs in R 2.15 (48). BEAST XML files implementing the cross-calibration and cross-bracing methods are available in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. All BEAST runs were inspected for convergence and completeness of sampling the posterior distribution, using Tracer (49).

Node Date Calibrations.

Dating calibration distributions were based on macroscopic fossils of Phanerozoic plants and animals that provide well-accepted calibration points used in previous molecular dating studies of Phanerozoic groups (50, 51) (SI Appendix, Table S6). Although the origin of crown angiosperms estimated by Smith et al. (50) was older than previous studies and fossil records (52), we found the discrepancy of ∼80 Mya negligible in comparison with the divergence estimates we were focused on in this study. More important, the other estimated dates used as calibration points from Smith et al. aligned well with the current estimates of divergences within land plants (53, 54). Plant calibration points were used for the plant vacuolar, mitochondrial, and plastid ATPases. The human/chicken and fly/mosquito divergences were used as metazoan calibration points (51). To maintain maximum agnosticism about the date of the last common ancestor and the divergence of the ATPase α and β subunits, which occurred before the last common ancestor, a uniform distribution before between 3,800 and 2,500 Mya was set at the base of the tree (the split between α and β subunits), assuming a biological origin of the GOE of 2,500 Mya (55) and that life most likely could not have began before the Late Heavy Bombardment of Earth, ca. 3,800 Mya (56).

Cross-Calibration and Cross-Bracing Methods.

In the cross-calibration method, each node in the gene tree corresponding to the same speciation event is assigned the same prior distribution on the date (i.e., the distribution given in SI Appendix, Table S6). These distributions are cross-calibrated, or “unlinked”; that is, during MCMC sampling, the date of each node is sampled independent from the prior distribution.

As with cross-calibration, in the cross-bracing method, each node in the gene tree corresponding to the same speciation event is assigned the same prior distribution on the date. However, in the cross-bracing method, the dates of nodes corresponding to the same speciation event are “linked.” As BEAST cannot formally do joint sampling of node dates, we achieved the same effect by coding into the BEAST XML an additional prior on the differences between the dates of linked nodes and the mean of the linked nodes. This prior was a normal distribution, with a mean of 0 (as any prior on the difference from the mean must have) and a SD set to 1% of the mean of the prior distribution of the date of the speciation event. Thus, although BEAST samples each linkednode independently during the actual MCMC sampling, samples in which the linked nodes are far apart will have a low posterior probability and will be rejected more often than in the cross-calibration approach. Inspection of linked node dates in Tracer (57) showed that they were indeed highly correlated to each other, unlike in the cross-calibration approach.

The 1% SD value on the distribution of differences from the mean date was chosen to indicate our prior high confidence that nodes corresponding to the same speciation event should have approximately the same date. The distribution on differences from the mean date was not set even more tightly, for two reasons. First, lineage-sorting processes can cause some degree of difference in the divergence dates of gene trees during speciation. Second, it was important to give BEAST’s MCMC sampler “breathing room” to sample the date of one linked node, then another, then another, and so on, without too many of these moves being rejected, so that the full posterior distribution could be explored. Further analysis was conducted as described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods and Supplemental Analysis of BEAST Runs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

P.M.S. was supported by National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0851070 (to Cheryl Kerfeld) and Howard Hughes Medical Institute/Gordon and Betty More Foundation Grant GBMF3070 (to Krishna Niyogi). N.J.M. was supported by National Science Foundation Grant DEB-0919451, a UC Berkeley Wang Fellowship, and a UC Berkeley Tien Fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 12168.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1305813110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brocks JJ, Logan GA, Buick R, Summons RE. Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes. Science. 1999;285(5430):1033–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman PF, Kaufman AJ, Halverson GP, Schrag DP. A neoproterozoic snowball earth. Science. 1998;281(5381):1342–1346. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavalier-Smith T. Cell evolution and Earth history: Stasis and revolution. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):969–1006. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavalier-Smith T. Deep phylogeny, ancestral groups and the four ages of life. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1537):111–132. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schopf JW, Kudryavtsev AB. Biogenicity of Earth's earliest fossils: A resolution of the controversy. Gondwana Res. 2012;22(3–4):761–771. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brasier MD, et al. Questioning the evidence for Earth’s oldest fossils. Nature. 2002;416(6876):76–81. doi: 10.1038/416076a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parham JF, et al. Best practices for justifying fossil calibrations. Syst Biol. 2012;61(2):346–359. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syr107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Budd GE. The cambrian fossil record and the origin of the phyla. Integr Comp Biol. 2003;43(1):157–165. doi: 10.1093/icb/43.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diver W, Peat C. On the interpretation and classification of Precambrian organic-walled microfossils. Geology. 1979;7(8):401–404. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Summons RE, Jahnke LL, Hope JM, Logan GA. 2-Methylhopanoids as biomarkers for cyanobacterial oxygenic photosynthesis. Nature. 1999;400(6744):554–557. doi: 10.1038/23005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rashby SE, Sessions AL, Summons RE, Newman DK. Biosynthesis of 2-methylbacteriohopanepolyols by an anoxygenic phototroph. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(38):15099–15104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704912104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welander PV, Coleman ML, Sessions AL, Summons RE, Newman DK. Identification of a methylase required for 2-methylhopanoid production and implications for the interpretation of sedimentary hopanes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(19):8537–8542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912949107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zuckerkandl E, Pauling L. Molecules as documents of evolutionary history. J Theor Biol. 1965;8(2):357–366. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(65)90083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin W, Gierl A, Saedler H. Molecular evidence for pre-Cretaceous angiosperm origins. Nature. 1989;339(6219):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doolittle RF. Reconstructing history with amino acid sequences1. Protein Sci. 1992;1(2):191–200. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roger AJ, Hug LA. The origin and diversification of eukaryotes: Problems with molecular phylogenetics and molecular clock estimation. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2006;361(1470):1039–1054. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulkidjanian AY, Makarova KS, Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Inventing the dynamo machine: The evolution of the F-type and V-type ATPases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(11):892–899. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwabe N, Kuma K, Hasegawa M, Osawa S, Miyata T. Evolutionary relationship of archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes inferred from phylogenetic trees of duplicated genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(23):9355–9359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.23.9355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogarten JP, et al. Evolution of the vacuolar H+-ATPase: Implications for the origin of eukaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86(17):6661–6665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philippe H, Forterre P. The rooting of the universal tree of life is not reliable. J Mol Evol. 1999;49(4):509–523. doi: 10.1007/pl00006573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doolittle WF, Bapteste E. Pattern pluralism and the Tree of Life hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(7):2043–2049. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hilario E, Gogarten JP. Horizontal transfer of ATPase genes—the tree of life becomes a net of life. Biosystems. 1993;31(2-3):111–119. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(93)90038-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7(1):214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A (2012) Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol 29(8):1969-1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Falcón LI, Magallón S, Castillo A. Dating the cyanobacterial ancestor of the chloroplast. ISME J. 2010;4(6):777–783. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schirrmeister BE, Antonelli A, Bagheri HC. The origin of multicellularity in cyanobacteria. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11(1):45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomitani A, Knoll AH, Cavanaugh CM, Ohno T. The evolutionary diversification of cyanobacteria: Molecular-phylogenetic and paleontological perspectives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(14):5442–5447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600999103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirrmeister BE, de Vos JM, Antonelli A, Bagheri HC. Evolution of multicellularity coincided with increased diversification of cyanobacteria and the Great Oxidation Event. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(5):1791–1796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato N. Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids. In: Wise R, Hoober JK, editors. The Structure and Function of Plastids, Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. Vol 23. Springer, The Netherlands; 2006. pp. 75–102. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douzery EJP, Snell EA, Bapteste E, Delsuc F, Philippe H. The timing of eukaryotic evolution: Does a relaxed molecular clock reconcile proteins and fossils? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(43):15386–15391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parfrey LW, Lahr DJG, Knoll AH, Katz LA. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(33):13624–13629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110633108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon HS, Hackett JD, Ciniglia C, Pinto G, Bhattacharya D. A molecular timeline for the origin of photosynthetic eukaryotes. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21(5):809–818. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston DT, Wolfe-Simon F, Pearson A, Knoll AH. Anoxygenic photosynthesis modulated Proterozoic oxygen and sustained Earth’s middle age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(40):16925–16929. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909248106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Canfield DE, Teske A. Late Proterozoic rise in atmospheric oxygen concentration inferred from phylogenetic and sulphur-isotope studies. Nature. 1996;382(6587):127–132. doi: 10.1038/382127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. Large-scale phylogenomic analyses indicate a deep origin of primary plastids within cyanobacteria. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(11):3019–3032. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner S, Pryer KM, Miao VPW, Palmer JD. Investigating deep phylogenetic relationships among cyanobacteria and plastids by small subunit rRNA sequence analysis. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1999;46(4):327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shih PM, et al. Improving the coverage of the cyanobacterial phylum using diversity-driven genome sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(3):1053–1058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217107110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schopf JW. Microfossils of the Early Archean Apex chert: New evidence of the antiquity of life. Science. 1993;260(5108):640–646. doi: 10.1126/science.260.5108.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schopf JW. The Fossil Record of Cyanobacteria. In: Whitton BA, editor. Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time. Springer, The Netherlands; 2012. pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann HJ. Precambrian microflora, Belcher Islands, Canada; significance and systematics. J Paleontol. 1976;50(6):1040–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwickl DJ, Hillis DM. Increased taxon sampling greatly reduces phylogenetic error. Syst Biol. 2002;51(4):588–598. doi: 10.1080/10635150290102339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wertheim JO, Sanderson MJ. Estimating diversification rates: How useful are divergence times? Evolution. 2011;65(2):309–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown JR, Doolittle WF. Root of the universal tree of life based on ancient aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase gene duplications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(7):2441–2445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keeling PJ, Fast NM, McFadden GI. Evolutionary relationship between translation initiation factor eIF-2γ and selenocysteine-specific elongation factor SELB: Change of function in translation factors. J Mol Evol. 1998;47(6):649–655. doi: 10.1007/pl00006422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mathews S, Clements MD, Beilstein MA. A duplicate gene rooting of seed plants and the phylogenetic position of flowering plants. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365(1539):383–395. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh K, Kuma K-i, Toh H, Miyata T. MAFFT version 5: Improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):511–518. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: Selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):2104–2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rambaut A, Drummond AJ (2007) Tracer version 1.5. Available at http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

- 50.Smith SA, Beaulieu JM, Donoghue MJ. An uncorrelated relaxed-clock analysis suggests an earlier origin for flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(13):5897–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001225107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berbee ML, Taylor JW. Dating the molecular clock in fungi – how close are we? Fungal Biol Rev. 2010;24(1–2):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sanderson MJ, Thorne JL, Wikström N, Bremer K. Molecular evidence on plant divergence times. Am J Bot. 2004;91(10):1656–1665. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.10.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wellman CH, Gray J. The microfossil record of early land plants. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1398):717–731, discussion 731–732. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doyle JA. Molecules, morphology, fossils, and the relationship of angiosperms and Gnetales. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1998;9(3):448–462. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1998.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kopp RE, Kirschvink JL, Hilburn IA, Nash CZ. The Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth: A climate disaster triggered by the evolution of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(32):11131–11136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504878102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen BA, Swindle TD, Kring DA. Support for the lunar cataclysm hypothesis from lunar meteorite impact melt ages. Science. 2000;290(5497):1754–1756. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rambaut A, Drummond A (2007) Tracer v1.4. Available at http://beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.