Abstract

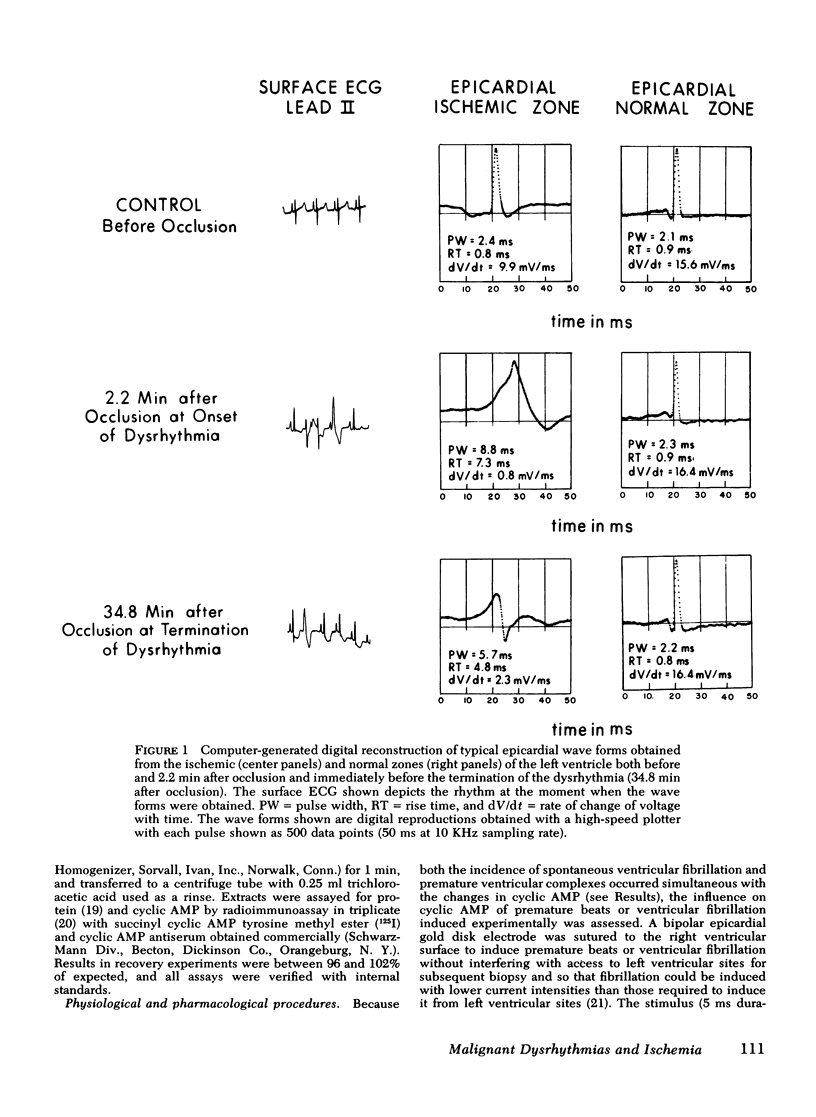

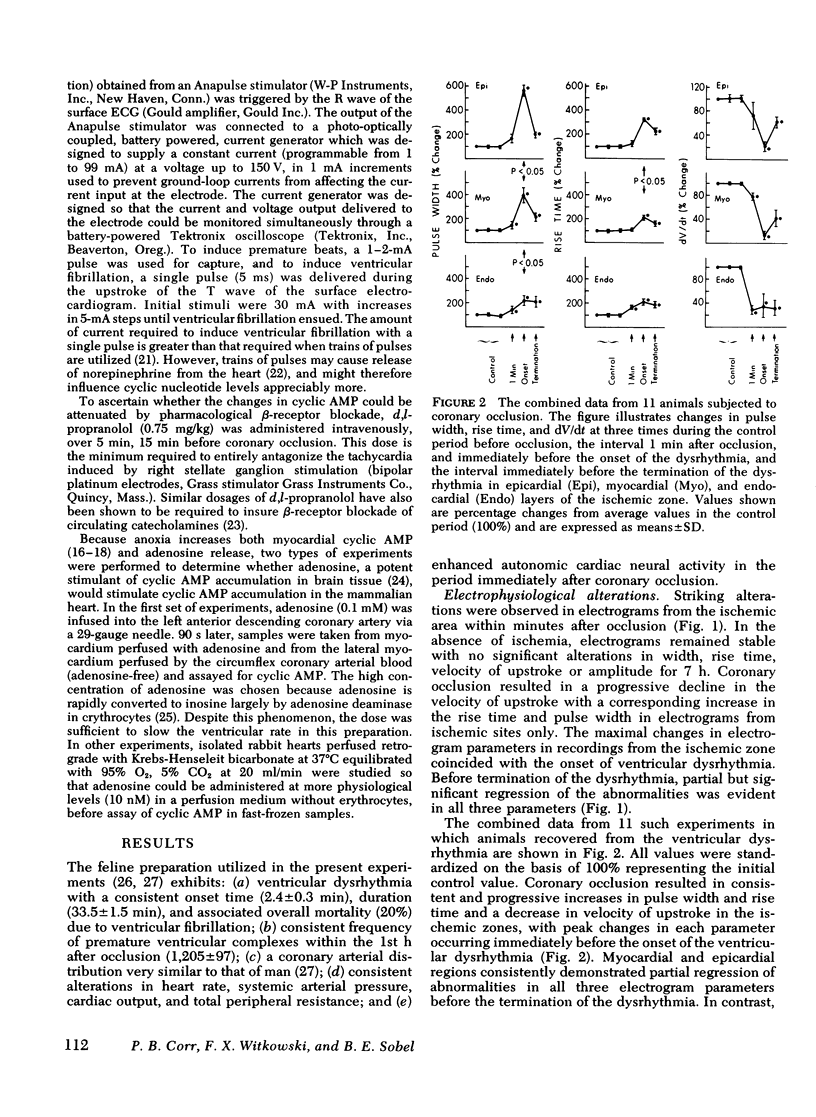

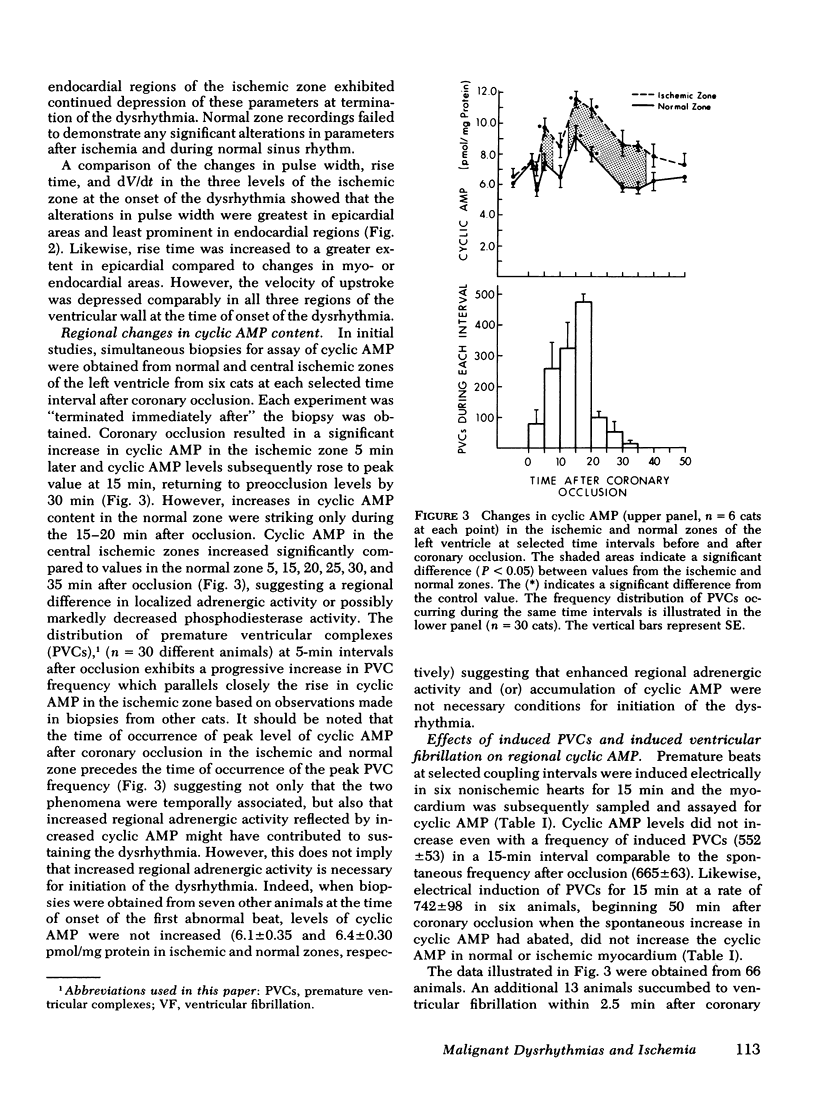

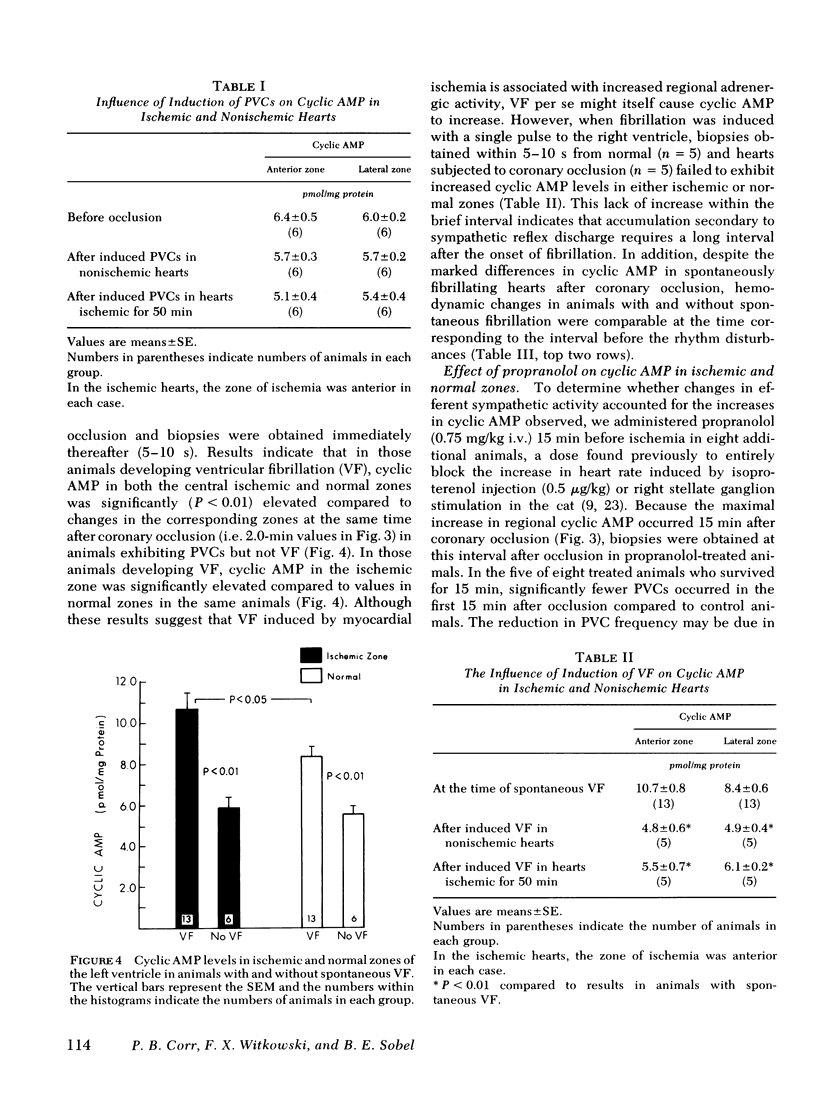

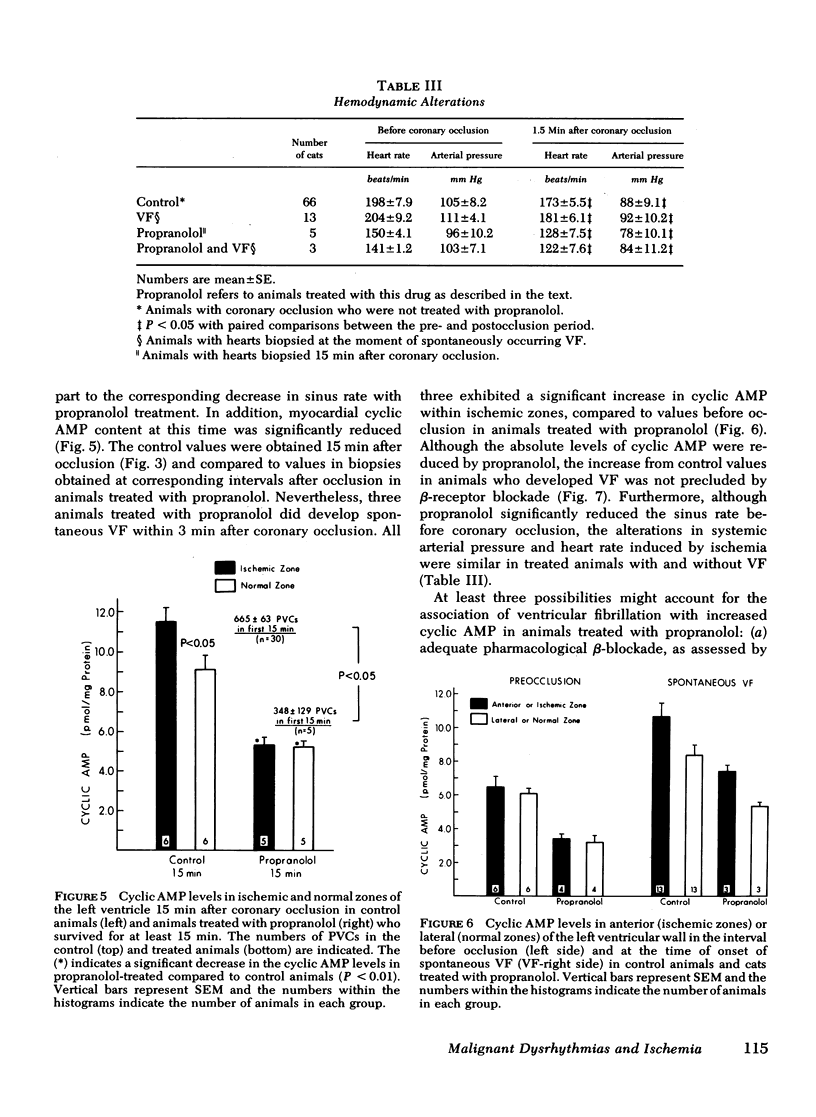

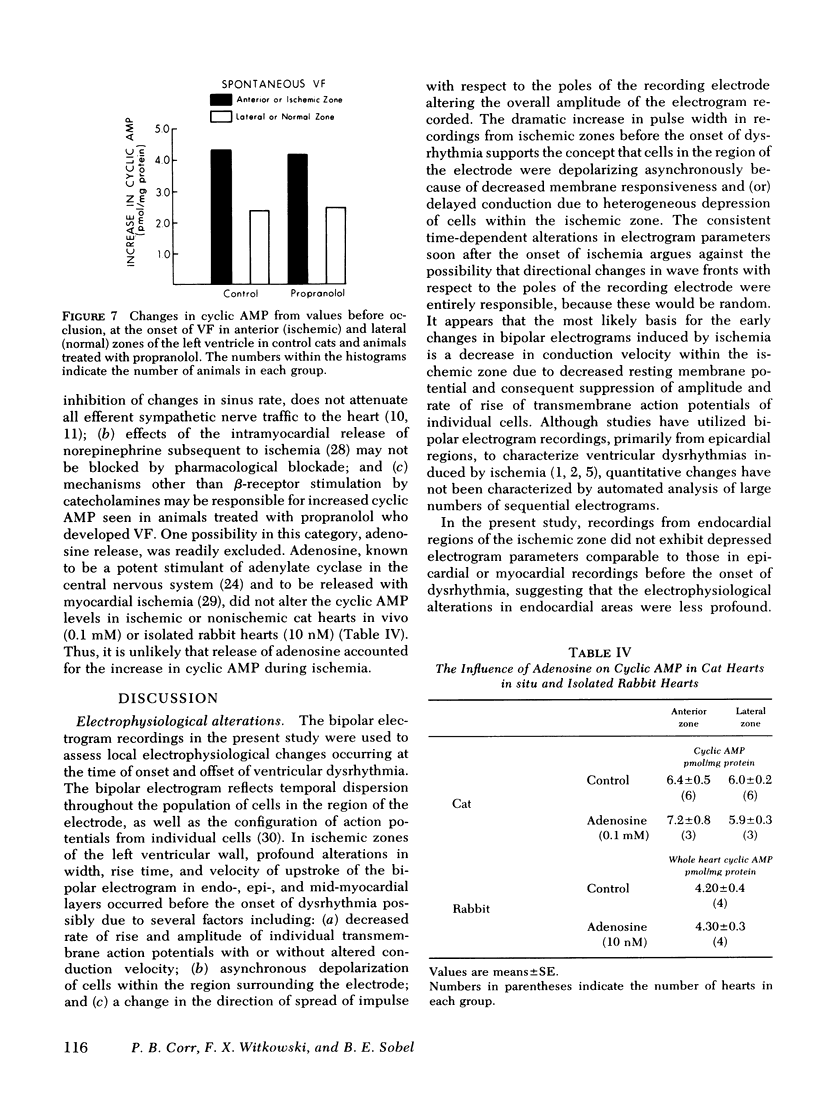

Continuously recorded bipolar electrograms were obtained simultaneously from epi-, endo-, and mid-myocardial regions of the ischemic and normal zones of cat left ventricle in vivo after coronary occlusion, analyzed by computer, and compared to regional cyclic AMP levels. Regional cyclic AMP content was used as an index of the combined local effects of: (a) efferent sympathetic nerve discharge; (b) release of myocardial catecholamines due to ischemia; and (c) circulating catecholamines. Ischemia resulted in a progressive increase in pulse width and rise time and a decrease in rate of rise of voltage (dV/dt) of the local electrograms from ischemic zones reaching a maximum within 2.4±0.3 min (mean±SE) at the time of onset of severe ventricular dysrhythmias, all of which returned toward control before the cessation of the dysrhythmia (33.5±1.5 min after coronary occlusion). Increases in cyclic AMP in ischemic zones preceded corresponding increases in the frequency of premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). Propranolol inhibited the increases in cyclic AMP and reduced the frequency of PVCs in animals without ventricular fibrillation. In animals with ventricular fibrillation, cyclic AMP was significantly elevated in normal and ischemic zones compared to animals with PVCs only. Electrical induction of PVCs or ventricular fibrillation in ischemic and nonischemic hearts failed to increase cyclic AMP. The results suggest that the changes in regional adrenergic stimulation of the heart may contribute to perpetuation of ventricular dysrhythmia and the genesis of ventricular fibrillation early after the onset of myocardial ischemia.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- BERNE R. M. REGULATION OF CORONARY BLOOD FLOW. Physiol Rev. 1964 Jan;44:1–29. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1964.44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A. M. A comparison of the effects of (plus of minus)-propranolol and (plus)-propranolol in anaesthetized dogs; beta-receptor blocking and haemodynamic action. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1969 Apr;21(4):241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1969.tb08239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borda L., Shuchleib R., Henry P. D. Effects of potassium on isolated canine coronary arteries. Modulation of adrenergic responsiveness and release of norepinephrine. Circ Res. 1977 Dec;41(6):778–786. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braasch W., Gudbjarnason S., Puri P. S., Ravens K. G., Bing R. J. Early changes in energy metabolism in the myocardium following acute coronary artery occlusion in anesthetized dogs. Circ Res. 1968 Sep;23(3):429–438. doi: 10.1161/01.res.23.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caen J. P., Jenkins C. S., Michel H., Chivot J. J., Levy-Toledano S., Rendu F. Adenosine metabolism in platelets and plasma. Ser Haematol. 1973;6(3):317–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. B., Gillis R. A. Effect of autonomic neural influences on the cardiovascular changes induced by coronary occlusion. Am Heart J. 1975 Jun;89(6):767–774. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90192-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. B., Gillis R. A. Role of the vagus nerves in the cardiovascular changes induced by coronary occlusion. Circulation. 1974 Jan;49(1):86–97. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. B., Pearle D. L., Hinton J. R., Roberts W. C., Gillis R. A. Site of myocardial infarction. A determinant of the cardiovascular changes induced in the cat by coronary occlusion. Circ Res. 1976 Dec;39(6):840–847. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.6.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr P. B., Sobel B. E. Automated data processing. An essential decision-making aid in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Adv Cardiol. 1977;20:54–71. doi: 10.1159/000399853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson J. G., Jr, Mayer S. E. Mechanisms of activation of cardiac glycogen phosphorylase in ischemia and anoxia. Circ Res. 1973 Oct;33(4):412–420. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.4.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond G. I., Hemmings S. J. Role of adenylate cyclase-cyclic AMP in cardiac actions of adrenergic amines. Recent Adv Stud Cardiac Struct Metab. 1973;3:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert P. A., Vanderbeek R. B., Allgood R. J., Sabiston D. C., Jr Effect of chronic cardiac denervation on arrhythmias after coronary artery ligation. Cardiovasc Res. 1970 Apr;4(2):141–147. doi: 10.1093/cvr/4.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowlis R. A., Sang C. T., Lundy P. M., Ahuja S. P., Colhoun H. Experimental coronary artery ligation in conscious dogs six months after bilateral cardiac sympathectomy. Am Heart J. 1974 Dec;88(6):748–757. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(74)90285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis R. A., Pearle D. L., Hoekman T. Failure of beta-adrenergic receptor blockade to prevent arrhythmias induced by sympathetic nerve stimulation. Science. 1974 Jul 5;185(4145):70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4145.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren E. N., Rosen O. M. Inhibition of a cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase from beef heart by catecholamines and related compounds. Mol Pharmacol. 1972 May;8(3):380–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govier W. C. Myocardial alpha adrenergic receptors and their role in the production of a positive inotropic effect by sympathomimetic agents. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Jan;159(1):82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN J., GARCIADEJALON P., MOE G. K. ADRENERGIC EFFECTS ON VENTRICULAR VULNERABILITY. Circ Res. 1964 Jun;14:516–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. S. Potassium and experimental coronary occlusion. Am Heart J. 1966 Jun;71(6):797–802. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(66)90601-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. I., Hamilton J. T., Manning G. W. Protective effect of beta adrenoceptor blockade in experimental coronary occlusion in conscious dogs. Am J Cardiol. 1972 Dec;30(8):832–837. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi T., Nakayama R., Kimura K. Effects of glucagon, prostaglandin E 1 and dibutyryl cyclic 3',5'-AMP upon the transmembrane action potential of guinea pig ventricular fiber and myocardial contractile force. Jpn Circ J. 1971 Jul;35(7):807–819. doi: 10.1253/jcj.35.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara R., el-Sherif N., Scherlag B. J. Early and late effects of coronary artery occlusion on canine Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1974 Sep;35(3):391–399. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara R., el-Sherif N., Scherlag B. J. Electrophysiological properties of canine Purkinje cells in one-day-old myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 1973 Dec;33(6):722–734. doi: 10.1161/01.res.33.6.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limas C. J., Ragan D., Freis E. D. Effect of acute cardiac overload on intramyocardial cyclic 3',5'-AMP: relation to prostaglandin synthesis. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1974 Oct;147(1):103–105. doi: 10.3181/00379727-147-38289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler W. G., Tay J. Effect of o-2-hydroxy-3-(tert.-butylamino) propoxybenzonitrile HCl (KO 1366) on beta adrenergic receptors in the cardiovascular system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1972 Feb;180(2):302–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien J. A., Strange R. C. The release of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate from the isolated perfused rat heart. Biochem J. 1975 Nov;152(2):429–432. doi: 10.1042/bj1520429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podzuweit T., Lubbe W. F., Opie L. H. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate, ventricular fibrillation, and antiarrhythmic drugs. Lancet. 1976 Feb 14;1(7955):341–342. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz B., Parmley W. W., Kligerman M., Norman J., Fujimura S., Chiba S., Matloff J. M. Myocardial and plasma levels of adenosine 3':5'-cyclic phosphate. Studies in experimental myocardial ischemia. Chest. 1975 Jul;68(1):69–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.68.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlag B. J., Helfant R. H., Haft J. I., Damato A. N. Electrophysiology underlying ventricular arrhythmias due to coronary ligation. Am J Physiol. 1970 Dec;219(6):1665–1671. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.6.1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherlag B. J., el-Sherif N., Hope R., Lazzara R. Characterization and localization of ventricular arrhythmias resulting from myocardial ischemia and infarction. Circ Res. 1974 Sep;35(3):372–383. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz J. Cyclic adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate in guinea-pig cerebral cortical slices: studies on the role of adenosine. J Neurochem. 1975 Jun;24(6):1237–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1975.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel B. E., Mayer S. E. Cyclic adenosine monophosphate and cardiac contractility. Circ Res. 1973 Apr;32(4):407–414. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner A. L., Wehmann R. E., Parker C. W., Kipnis D. M. Radioimmunoassay for the measurement of cyclic nucleotides. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1972;2:51–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamargo J., Moe B., Moe G. K. Interaction of sequential stimuli applied during the relative refractory period in relation to determination of fibrillation threshold in the canine ventricle. Circ Res. 1975 Nov;37(5):534–541. doi: 10.1161/01.res.37.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. W. Adrenaline-like effects of intracellular iontophoresis of cyclic AMP in cardiac Purkinje fibres. Nat New Biol. 1973 Sep 26;245(143):120–122. doi: 10.1038/newbio245120a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. W., Giles W., Greengard P. Cyclic AMP mediates the effects of adrenaline on cardiac purkinje fibres. Nat New Biol. 1972 Dec 6;240(101):181–183. doi: 10.1038/newbio240181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VINCENZI F. F., WEST T. C. RELEASE OF AUTONOMIC MEDIATORS IN CARDIAC TISSUE BY DIRECT SUBTHRESHOLD ELECTRICAL STIMULATION. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1963 Aug;141:185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S. W., Adgey A. A., Pantridge J. F. Autonomic disturbance at onset of acute myocardial infarction. Br Med J. 1972 Jul 8;3(5818):89–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5818.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit A. L., Friedman P. L. Basis for ventricular arrhythmias accompanying myocardial infarction: alterations in electrical activity of ventricular muscle and Purkinje fibers after coronary artery occlusion. Arch Intern Med. 1975 Mar;135(3):459–472. doi: 10.1001/archinte.135.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberger A., Krause E. G., Heier G. Stimulation of 3',5'-cyclic AMP formation in dog myocardium following arrest of blood flow. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1969 Aug 15;36(4):664–670. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(69)90357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollenberger A., Shahab L. Anoxia-induced release of noradrenaline from the isolated perfused heart. Nature. 1965 Jul 3;207(992):88–89. doi: 10.1038/207088a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]