Abstract

A choice that reliably produces a preferred outcome can be automated to liberate cognitive resources for other tasks. Should an outcome become less desirable, behavior must adapt in parallel or become perseverative. Corticostriatal systems are known to mediate choice learning and flexibility, but the molecular mechanisms subserving the instantiation of these processes are not well understood. We integrated mouse behavioral, immunocytochemical, in vivo electrophysiological, genetic, and pharmacological approaches to study choice. We found that the dorsal striatum (DS) was increasingly activated with choice learning, whereas reversal of learned choice engaged prefrontal regions. In vivo, DS neurons showed activity associated with reward anticipation and receipt that emerged with learning and relearning. Corticostriatal or striatal GluN2B gene deletion, or DS-restricted GluN2B antagonism, impaired choice learning, whereas cortical GluN2B deletion or OFC GluN2B antagonism impaired shifting. Our convergent data demonstrate how corticostriatal GluN2B circuits govern the ability to learn and shift choice behavior.

INTRODUCTION

The ability to make adaptive choices is fundamental to survival. When a given choice reliably produces a preferred outcome, it can be behaviorally efficient to automate execution of that choice and liberate cognitive processing for other tasks. However, if the value of that same outcome is lessened or a better choice becomes available, actions must adapt accordingly to prevent perseverative, intransigent patterns of behavior.

Choice learning and shifting are thought to be dependent upon anatomically interconnected corticostriatal ‘loops’1. Animal lesion and single-unit recording experiments, together with human neuroimaging studies, have shown the ventromedial (vmPFC) and orbitofrontal (OFC) subregions of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) subserve decision-making and the capacity for rapidly shifting between actions 2–4. The dorsal striatum (DS), by contrast, is posited to support the representation of reward-action relationships to guide choice learning 5, and to enable the automation and habitization of behavior 6,7.

Plastic changes within corticostriatal circuits may allow for the encoding and expression of stable choices. However, while there has been progress in elucidating neurochemical substrates of these processes 8,9, the molecular mechanisms underlying such plasticity remain poorly understood. An excellent candidate in this regard is the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) – given prior work showing that NMDARs, which are essential for certain forms of synaptic plasticity, subserve both PFC-mediated rodent cognitive functions 10 as well as DS-mediated motor 11 and instrumental 12,13 learning.

NMDARs are heteromers comprising an obligatory GluN1 subunit and modulatory GluN2A-2D subunits. GluN2B-containing NMDARs are expressed throughout cortex and striatum 14, and have slower channel kinetics and a lower channel open probability than GluN2A-NMDARs 15. Pharmacological and gene mutation studies demonstrate that inactivating or overexpressing GluN2B, either systemically or specifically in forebrain regions, alters spatial reference and working memory, trace fear and extinction, attention, and conditional discrimination 15–20. Together, these data support a critical role for GluN2B in mediating certain types of cognitive functions, but do not isolate the specific contribution of corticostriatal GluN2B to choice learning and shifting.

Here, we employed a multi-technique approach to determine the role of GluN2B-expressing corticostriatal circuits in a simple pairwise choice behavior, as assayed in visual discrimination and reversal paradigm. We found dynamic patterns of PFC and DS engagement as reliable choice response developed via trial and error learning, and then subsequently shifted to an alternative choice. In vivo single-unit recordings revealed dynamic changes in DS neuronal activity around reward anticipation and receipt that tracked learning and relearning. Choice relearning also drove alterations in DS synaptic plasticity. Using regionally-restricted gene deletions and drug microinfusions, we found GluN2B-expressing circuits in DS were critical for choice learning, but not flexibility. Conversely, GluN2B-expressing circuits in OFC mediated choice flexibility, not learning. These data demonstrate highly dynamic patterns of corticostriatal activity mediating choice, and reveal GluN2B as a key molecular mechanism underpinning this process.

RESULTS

Structure of choice behavior

We trained C57BL/6J mice on a translationally-relevant touchscreen-based pairwise visual discrimination and reversal paradigm 21–23. Two distinct shapes were presented on a touchscreen in a spatially pseudorandomized manner. Responses at the CS+ resulted in food reward delivery (=correct). Responses to the CS– produced a 15 sec lights-out/timeout period (=error). Error choices were followed by a repeat presentation of the previous trial (correction trial). Error choices on correction trials (=correction error) led to additional correction trials until a correct choice (not recorded as a correct choice) was made. There were 30 trials (excluding correction trials) per daily session. After a mouse achieved discrimination criterion of >85% correct choice over 2 consecutive sessions, the CS+/CS– designation was reversed. Reversal training continued until the 2-session >85% correct choice criterion was re-attained. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications 24.

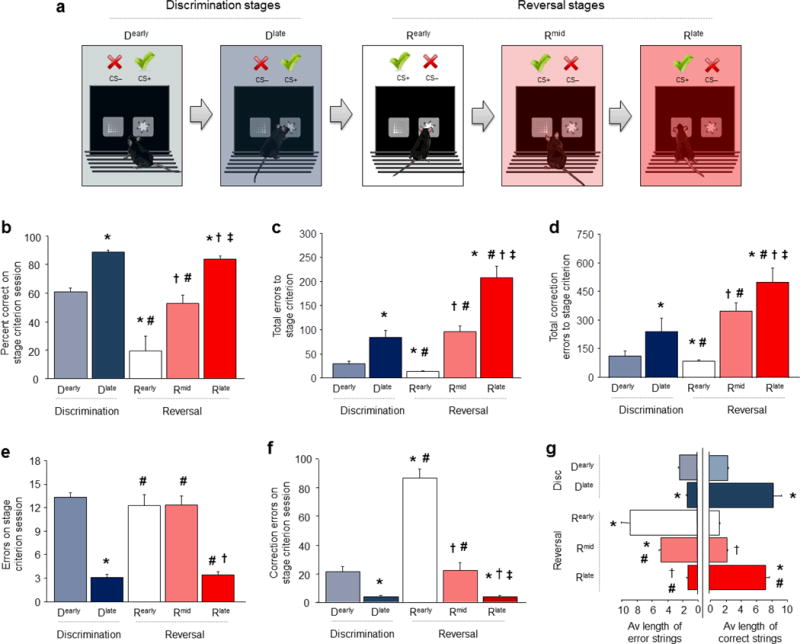

We employed a stage-wise analysis 25 to represent each of 5 major discrimination and reversal performance stages (Figure 1A): 1) chance-level choice during the first session of discrimination (Dearly), 2) high choice accuracy by the final session of discrimination (Dlate), 3) very low choice accuracy on the first reversal session (Rearly), 4) chance-level (i.e., 50% correct) choice at the midpoint session of reversal (Rmid), and finally, 5) high choice accuracy by the final reversal session (Rlate) (stage effect on %correct choice: F4,40=28.57, P<.01) (Figure 1B). Mice required an average of 8.0±2 sessions to complete discrimination and approximately twice as many sessions (15.8±2) to complete reversal, and hundreds of trials to form a robust discriminated choice and then relearn it after reversal of the stimulus-reward contingencies (consistent with 22,23). This is illustrated by the total trials made to reach each discrimination or reversal performance stage (Dearly=100.0±12.7, Dlate=243.5±43.1, Rearly=18.2±8.0, Rmid=204.2±39.2, Rlate=447±89.0, F4,38=11.86), and by the total number of errors (F4,38=34.92, P<.01) (Figure 1C) and correction errors (F4,38=18.18, P<.01) (Figure 1D) made.

Figure 1. Choice learning, shifting and relearning in a choice task.

(a) Five stages of choice performance as mice learn a pairwise visual discrimination, then shift and relearn after reversal. Dearly=first discrimination session, Dlate=final discrimination session, Rearly=first reversal session, Rmid=session midway through reversal, Rlate=final reversal session. (b) Percent choice accuracy increased from Dearly to Dlate, decreased during Rearly and subsequently increased on Rmid and again Rlate. (c) Total errors to reach Dlate was higher than Dearly, and higher to reach Rmid and Rlate than Rearly. (d) Similarly, total correction errors to reach Dlate was higher than Dearly, and higher to reach Rmid and Rlate than Rearly. (e) More errors were committed on Dearly than Dlate stage, and the Rearly than Rmid and Rlate stage. (f) More correction errors were committed on Dearly than Dlate stage, and were markedly elevated on Rearly, as compared to the Rmid and Rlate stage. (g) The average length of consecutive strings of correct choices increased from Dearly to Dlate, decreased during Rearly and increased on Rmid and again Rlate. The average length of consecutive strings of error (including perseverative) choices decreased from Dearly to Dlate, fell during Rearly and remained relatively elevated by Rmid and then decreased by Rlate. Data are Means±SEM. n per stage for b-f: Dearly=10, Dlate=9, Rearly=8, Rmid=8, Rlate=7. *P<.05 vs. Dearly, #P<.05 vs. Dlate, †P<.05 vs. Rearly, ‡P<.05 vs. Rmid, **P<.01 vs. Base.

To gain further insight into how the structure of choice behavior changed across stages, we examined choices made on the session at which mice attained criterion for each performance stage. The number of choice errors made generally decreased across stages, with fewer errors on the Dlate than the Dearly stage, followed by an increase in errors on the Rearly and Rmid stages and a further decrease by the Rlate stage (F4,39=33.94, P<.01,) (Figure 1E). Correction errors showed a similar pattern to errors (F4,40=69.29, P<.01) (Figure 1F). One difference was that by far the highest number of correction errors made was on the Rearly stage. This is consistent with vigorous perseverative choice responding at the previous CS+ and indicates that correction errors are a sensitive measure of preservative responding on this task. In contrast to the clear stage-wise changes in these measures, neither the time to make a choice nor the latency to retrieve rewards (simple measures of motivation and motor function) changed significantly across stages, although a non-significant decrease in both measures across sessions was apparent (Figure S1A).

We next calculated the average length of continuous strings of either correct or error choices. Mice engaged in equal sampling of stimuli (strings of ~2 responses at each stimulus) during Dearly, but then, as they learned to make the correct choice by Dlate, there was a parallel shift to making long strings (~8) of consecutive correct choices (correct strings: F4,37=31.87, P<.01, errors strings: F4,37=41.39, P<.01) (Figure 1G). The same pattern was seen for correct choice strings across stages Rearly to Rlate, as mice relearned the choice during reversal. Conversely, there were long strings (~9) of error choices during Rearly, reflecting the high rates of perseveration during initial reversal. Interestingly, error strings remained relatively elevated (5) during Rmid (before decreasing by Rlate) even though overall choice accuracy had improved to chance levels by Rmid, and was essentially at the same level as during the start of choice discrimination learning. Thus, while chance performance on the initial discrimination involved exploratory sampling of the choice options, chance performance at reversal was characterized by correct responses interspersed with blocks of perseverative responses – illustrating how ostensibly similar profiles of choice performance were associated with qualitatively distinct patterns of behavior. These analyses establish the major patterns of behavior across choice learning and relearning and provide a framework for studying the underlying neural and molecular mechanisms.

Corticostriatal activation associated with choice learning

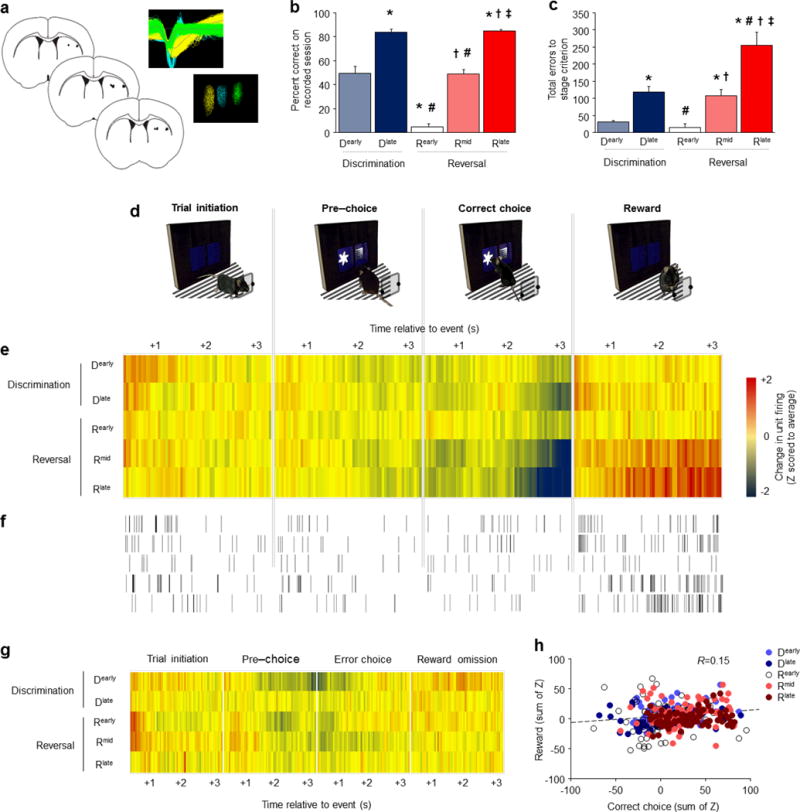

Our next objective was to identify the principal brain regions activated during choice behavior. To this end, we trained mice to one of the 5 choice performance stages (Dearly-Rlate) and sacrificed for immunocytochemical quantification of the immediate-early gene (IEG), c-Fos, in 13 different forebrain regions. The number of c-Fos-positive cells in various regions changed as a function of stage (Table S1). The clearest patterns were seen in regions of the PFC and DS. There was increased c-Fos expression in the OFC (F4,36=4.17, P<.01) (Figure 2A,B) and prelimbic area of vmPFC (PL) (F4,37=5.40, P<.01) (Figure 2C,D) specifically, during Rearly and, to a lesser extent Rmid, as the original choice was reversed. These data demonstrate that choice shifting in our task activates the same subregions of PFC governing reversal learning and other measures of flexible decision-making in rats, non-human primates and humans 2–4,26. Activation in these regions could reflect a number of processes that include, but may not be limited to, relearning of the change in stimulus-reward contingencies. For example, this could reflect a response to surprise or confusion at the contingency shift, that has been mainly linked to other prefrontal areas (e.g., anterior cingulate) 27. The type of reversal procedure we employed in the current study cannot readily parse these alternatives. Notwithstanding, engagement of OFC or PFC is not epiphenomenal to relearning and clearly plays an important functional role, as demonstrated by previous evidence that lesioning these regions significantly impacts reversal learning in the current task 24.

Figure 2. Dynamic corticostriatal activation with choice learning and relearning.

(a,b) The number of c-Fos-positive cells in OFC was elevated during Rearly and Rmid, relative to Dearly and Dlate. (c,d) The number of c-Fos-positive cells in PL was increased during Rearly and Rmid, relative to Dearly and Dlate. (e,f) c-Fos-positive cells in DS increased from Dearly to Dlate, decreased (<Dearly levels) during Rearly and increased in a step-wise manner on Rmid and then Rlate. C57BL/6J mice with bilateral excitotoxic lesions of DS (g), made more errors (h) and correction errors (i) to get attain discrimination criterion, as compared to sham controls. n per stage for c-Fos: Dearly=10, Dlate=9, Rearly=8, Rmid=8, Rlate=7. n per treatment for lesions: Lesion=14, Sham=15. Data are Means±SEM. Example images show the whole 360 × 460 μm region sampled. *P<.05 vs. Dearly, #P<.05 vs. Dlate, †P<.05 vs. Rearly, ‡P<.05 vs. Rlate, **P<.05 vs. sham.

While OFC and PL were most active during choice shifting, DS activation tracked choice learning and relearning. c-Fos expression in DS increased from Dearly to Dlate during choice learning (F4,39=11.02, P<.01) (Figure 2E,F). c-Fos expression was then decreased on Rearly, notably, to levels that were lower than on Dearly, suggesting DS was not simply unengaged, but may have been inhibited during initial reversal. As mice subsequently relearned choice, there was step-wise increase in DS c-Fos expression over the reversal stages. The close parallel between DS activation and choice performance imply that activation of this brain region may have supported choice learning and relearning. These data showed equivalent engagement of the lateral and medial aspects of DS, while prior rodents lesion studies specifically implicate the lateral DS in stimulus-reward and habit behavior, and the medial DS in goal-directed behavior 7. However, the medial DS is also involved in reversal 28 and while inactivation of medial DS impairs goal-directed behavior 29, inactivation limited to the posterior part of medial DS can also impair habit-related, stimulus-outcome learning 29. Thus, the relative contributions of the medial and lateral DS to habit are complex and their relative roles in choice learning remain particularly unclear.

Further demonstrating the functional contribution of lateral DS to choice relearning in our task, DS lesions disrupt choice relearning 24. To confirm that initial choice learning was also DS-dependent, we made discrete bilateral lesions of lateral DS prior to discrimination (Figure 2G), and showed that lesioned mice made more discrimination and errors (t(28)=2.51, P<.01) and correction errors (t(28)=2.12, P<.01) errors than sham controls (Figure 2H–I). Given the importance of DS to motor behavior, we confirmed that choice learning deficits in lesioned mice was not an artifact of locomotor dysfunction by showing no difference between sham and lesion mice in an open field (Figure S2A).

Given the contribution of DS to choice learning and relearning, we asked whether repeated DS engagement over the course of training in our task might have ‘primed’ the region in such a way as to positively transfer (e.g., to improve) performance on other striatal-dependent forms of learning. Mice were trained to either the Rlate or Dlate stages, or given operant training with no choice learning (matching for total sessions) and, the day after, assessed for DS-mediated motor learning in the rotarod 30. Groups showed similar motor learning over 10 training trials (F1,15=27.02, P<.01) (Figure S2B), indicating no demonstrable performance transfer between the two DS-dependent forms of learning.

A critical role of DS in choice learning in the current setting extends prior findings obtained in a range of species, including human subjects, showing that DS mediates stimulus-response learning and automatized, habitual behaviors 6,7. Extended instrumental training can promote the development of habitual behavior 31 and we have previously shown 24 that choice behavior during relearning (as early as Rmid) is insensitive to reinforcer devaluation – an operational measure of habit 31. While it remains to be shown whether choice behavior in our task becomes habitual with training, current and prior IEG and lesion data demonstrates critical roles for OFC and DS in choice learning and relearning.

In vivo DS single-unit activity associated with choice learning

While our results thus far indicate a critical role for DS in choice learning and relearning, IEG and lesion approaches do not indicate which, if any, specific behavioral components of task performance are associated with DS function. To more directly test for DS activity in close temporal coincidence with behavior, we conducted in vivo neuronal recordings in DS in freely-moving mice. Multi-electrode arrays were implanted in DS (Figure 3A) and recordings made from 402 putative neurons (84±3 per stage) in 8 mice during sessions corresponding to each of the 5 performance stages (Dearly through Rlate). Choice accuracy (F4,45=86.09, P<.01) (Figure 3B) and the errors made (F4,45=23.94, P<.01) (Figure 3C) differed between stages in the same manner as above.

Figure 3. In vivo striatal single-unit activity shifts with choice learning.

(a) Position of electrode placements and example waveforms recorded from 3 separate units. Percent correct responding (b) and total cumulative errors from the start of learning and relearning (c) on the session on which ex vivo recordings were made. (d) Single-unit activity on correct-choice trials was recorded during 3-second epoch aligned to trial-initiation, pre-choice, choice, and reward receipt. (e) Divergence from average neuronal activity per 50 msec timebin was strongest during the correct choice and reward epochs. An inhibition of activity after a correct choice and immediately prior to reward collection developed with learning and relearning, while population-level excitation after reward emerged most strongly during relearning. (f) Example of firing in an individual neuron reflecting population-level dynamics across learning/relearning. (g) Stage-wise shifts in activity around choice and reward found for correct choices were not found for error choices. (h) Reward-related activity of individual units was weakly correlated with their activity after correct choices. n=8 mice, 403 units (n=84±3/stage). Data are Means±SEM. *P<.05 vs. D early, #P<.05 vs. D late, †P<.05 vs. R early, ‡P<.05 vs. R mid.

We did not classify neurons based on firing rate or waveform although some studies have indicated a preferential contribution of DS fast-spiking interneurons in choice execution 32. The activity of all recorded neurons (5.89±8.4 Hz) was sorted into 50-msec timebins and temporally aligned to 4 separate event-related 3-sec epochs: after trial initiation, immediately prior to choice, after choice, and after reward retrieval (Figure 3D). To avoid overlap of activity across epochs, measurement of neuronal activity during one epoch was terminated at the time of next epoch. Activity was segregated for correct choice and error choice trials.

To measure the average activity of the recorded population, activity for each neuron was Z-score normalized to the average firing rate of that neuron across all 4 event epochs – with positive and negative values respectively indicating relatively high and low activity, relative to the average, at a given timepoint. For correct choice trials, there was stage × time interactions for trial initiation (F236,23364=1.61, P<.01), correct choice (F236,23364=2.40, P<.01) and reward (F236,23364=2.56, P<.01), but not pre-choice, epochs (Figure 3E,F). The effect for trial initiation was largely due to modest activity increases during Dearly. More striking stage-wise activity was evident during the latter seconds of the epoch after a correct choice was made and immediately prior to reward receipt. Specifically, a population-level inhibition of activity emerged with learning and relearning, peaking by Rlate. Conversely, marked excitation developed with learning and particularly relearning after reward collection. Interestingly, although choice and reward-related activity developed in tandem across performance stages, there was only a weak correlation between the two (Pearson’s R=0.154), suggesting largely segregating populations of DS neurons encoded each behavioral event (Figure 3H).

To examine the network organization of DS neurons across stages, we examined the event-related firing of individual units. This clearly illustrated a learning and relearning-related increase in population of units that inhibited their activity prior to reward (Figure S3A). To further quantify these shifts, we calculated the percentage of recorded cells exhibiting event-related Z-scores>+1.0 (positive-modulated) or<−1.0 (negative-modulated) at a given timebin. These data mirrored the individual single-unit data, showing a higher percentage (~15%) of negatively-modulated choice-related units for correct choice trials, and higher percentage of positively-modulated reward-related units, during later reversal stages (Figure S3B). These stage-wise shifts were specific to correct choices and not found for error trials. While there was stage × time interactions for trial initiation (F236,23364=1.86, P<.01), pre-choice (F236,23364=1.74, P<.01), choice (F236,23364=1.57, P<.01), and reward-omission (F236,23364=1.16, P<.01) error trial epochs, there was no clearly discernible stage-wise shift in activity associated with choice or reward-omission other than modest post-error inhibition on Dearly and Rearly-Rmid and excitation after reward on Dearly (Figure 3G, S4A,B).

These data demonstrate dynamic changes in the activity of DS neurons around choice and reward receipt occurring in concert with improving choice performance. The pattern of changes was consistent with the emergence of inhibition of a significant population of DS units in anticipation of reward receipt. Because neuronal excitation after reward receipt was restricted to learning and especially relearning, it cannot simply be an artifact of chewing or reflect a signal of the hedonic value or the reward. However, given the importance of the DS to motor functions 33, we asked whether the post-choice DS activity changes across stages reflected stage-related changes in movement timing, rather than reward anticipation. Post-correct choice activity data for each stage was sorted, using a median split, according to ‘fast’ or ‘slow’ choice-to-reward latencies. Activity did not differ as a function of the latency from choice to reward (Figure S5); while both the fast and slow response times were virtually equivalent on the Rearly (fast=1.5 sec, slow=3.8) and Rlate (fast=1.4 sec, slow=3.6) stages, there was only strong pre-reward activity inhibition for Rlate and not Rearly. Thus, the speed of choice-to-reward movement does not explain the stage-wise activity shifts in DS neuronal activity. Nonetheless, we cannot at this point exclude the potential contribution of other behavioral states that vary coincident with learning.

The patterns of DS neuronal activity associated with choice learning echoes earlier examples of DS neurons exhibiting task-relevant shifts in activity during motor learning 30, formation of a motor habit 34 or acquisition of stimulus-response learning 25. For example, DS neural activity associated with performance in a T-maze task was rapidly shifted as responses are extinguished and reinstated 25. Our data add to this literature by showing clear and highly dynamic in vivo DS neuronal responses in the setting of an operant choice task, and provide further support for the importance of this brain region in mediating choice behavior. It will be of significant interest to examine how these dynamic changes in DS activity relate to concurrent changes in OFC or vmPFC neuronal activity given prior in vivo evidence that activity in the regions is closely coupled during learning 35.

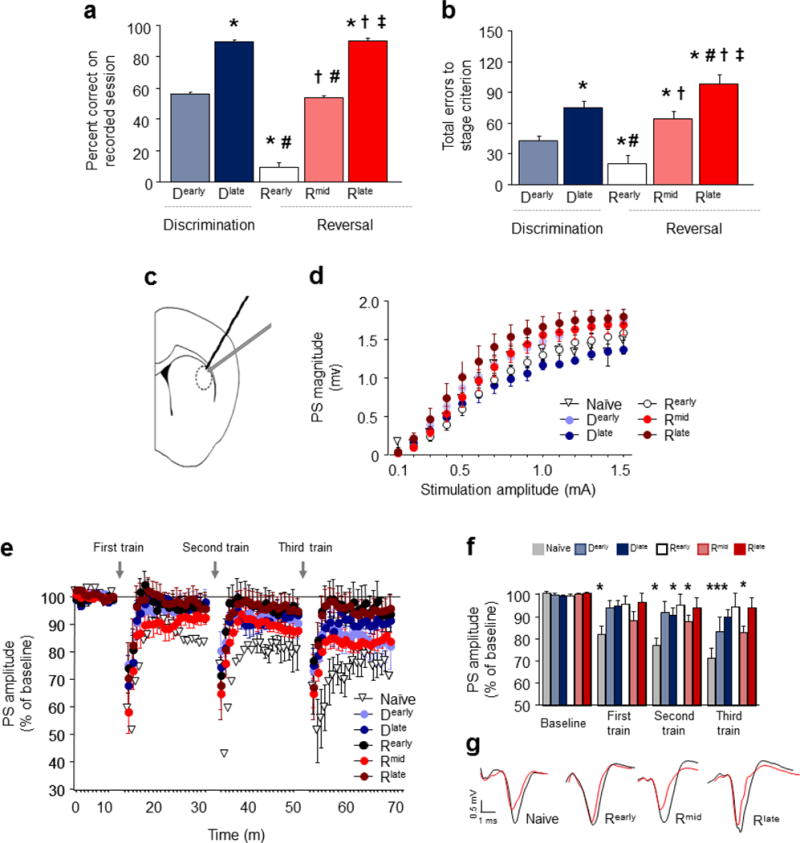

DS plasticity associated with choice learning

Changes in DS unit activity across choice stages suggest plasticity mechanisms may be engaged to shape and reshape behavior. We therefore tested whether choice stages were associated with alterations in DS plasticity using ex vivo slice electrophysiology. Mimicking the design of the experiments above, mice were trained to 1 of the 5 performance stages and, along with a set of behaviorally-naïve controls, sacrificed 2 hr later for electrophysiology recordings in slices containing DS. Choice accuracy (F4,45=325.85, P<.01) (Figure 4A) and the total number of errors made (F4,45=18.70, P<.01) (Figure 4B) differed between stages in the now expected manner, closely replicating the patterns in the earlier experiments.

Figure 4. Striatal synaptic plasticity changes with choice learning.

Ex vivo recordings were conducted after attaining the 5 choice performance stages. Percent correct responding (a) and total cumulative errors from the start of learning and relearning (b) on the session immediately prior to ex vivo recordings. (c) Position of field potential recordings in coronal slices containing DS evoked by local afferent stimulation. (d) Population spike (PS) amplitude did not vary with stage, but was relatively left-shifted in mice trained to Rlate. (e) Time course of PS amplitude at baseline and following 3 trains of high-frequency stimulation (HFS). (f) Average baseline and post-HFS values. All 3 HFS trains evoked LTD in test-naïve mice, as compared to baseline. Mice trained to Dlate or Rearly showed LTD after the 2nd or 3rd, but not 1st, HFS trains, and mice trained to Dearly showed LTD after the 3rd train only. LTD was occluded in mice trained to Rearly or Rlate. (g) Representative traces after the third stimulation train. n per stage: naïve=5, Dearly=9, Dlate=9, Rearly=9, Rmid=9, Rlate=7. For a-b: *P<.05 vs. D early, #P<.05 vs. D late, †P<.05 vs. R early, ‡P<.05 vs. Rmid. For f: *P<.05 vs. baseline.

Evoked field potentials were recorded at DS synapses following local afferent stimulation by a locally-placed bipolar twisted-tungsten electrode 36 (Figure 4C). We first measured the efficacy of synaptically-driven neuronal output of DS neurons by measuring the population spike (PS) magnitude at increasing stimulation-amplitudes (0.1–1.5 mA) (F14,364=231.35, P<.01). There was no difference (P>.05) in this input/output measure across stages, and although there was a trend for a leftward shift at the late reversal stage (Rlate) that could indicate an increase in the efficacy of activation, there was no discernible stage-wise pattern in these trends (Figure 4D). Next, we examined long-term depression (LTD) at these synapses using a high-frequency stimulation (HFS) protocol comprising sets of (2 × 1 sec) trains of 100 pulses beginning 10 min after establishing baseline PS amplitude, and continuing once every 20 min. We used a procedure entailing multiple trains in order to test for graded alterations in LTD, as successive trains are expected to produce stronger LTD 36. Data are presented in the full time course (Figure 4E) and the averaged values for each train and baseline (Figure 4F). Example traces are also shown (Figure 4G).

In behaviorally-naïve mice, robust LTD was produced after the third (t(6)=6.56, P<.01), second (t(6)=6.70, P<.01) and first (t(6)=4.99, P<.01) sets of trains, as indicated by a decrease in PS after HFS relative to baseline prior to the first set of trains (Figure 4E,F). By contrast, LTD was partially impaired in mice trained to either Dearly or Dlate, being evident after only the third (t(7)=2.40, P<.05), or the second (t(7)=2.89, P<.01) sets of trains, respectively (Figure 4E,F). Partial loss of LTD at the beginning of choice testing suggests that plasticity changes already developed at this early point in training, possibly due to some engagement of DS during pre-training.

More strikingly, LTD was essentially absent after training to Rearly and Rlate (i.e., no LTD after any train) (Figure 4E,F). This loss of plasticity corresponds to the stages where choice behavior is relatively rigid, either due to perseveration during initial reversal or high choice accuracy after extensive training at late reversal. Importantly, loss of plasticity is not simply a function of the amount of choice training mice had undergone. This was evidenced by the ‘recovery’ of robust LTD during the Rmid stage of reversal when mice were shifting and relearning the choice: significant LTD after the third (t(8)=5.33, P<.01) and second (t(8)=3.80, P<.01) sets of trains and showed a trend for LTD after first (t(8)=2.62, P=.068) set of trains (Figure 4E,F). Thus there appeared to be a close association between plasticity at DS neurons and stages of maximal demands on choice flexibility, such that plasticity was highest when mice were relearning the choice, and lowest when choice was either perseverative or well-learned.

These ex vivo electrophysiological data are consistent with DS plasticity as a dynamic correlate of choice learning, but do not establish a causative relationship between changes at DS neurons and choice performance. As in the case the in vivo single-unit measures, this approach is unable to directly attribute plastic changes to learning and not some coincident behavioral states. Nonetheless, because changes in LTD were evident in the absence of concomitant changes in synaptically-driven DS neuronal firing (assessed via I/O analysis), we can conclude that they are unlikely to be an effect of a general enhancement of neuronal output. . Instead, these data imply alterations in molecular mechanisms mediating plasticity at DS synapses. Prior findings implicate dopamine as one possible contributing mechanism. Phasic dopamine activity is critical to reinforcement learning in various behavioral settings and is hypothesized to support learning in part by signaling reward uncertainty to regions which receive dense inputs, such as DS 37. In addition, dopamine mediates DS LTD 38 and dopamine applied coincident with corticostriatal synaptic activation promotes synaptic plasticity 39,40. Examination of shifts in dopamine input to DS during choice learning is a focus of our future studies.

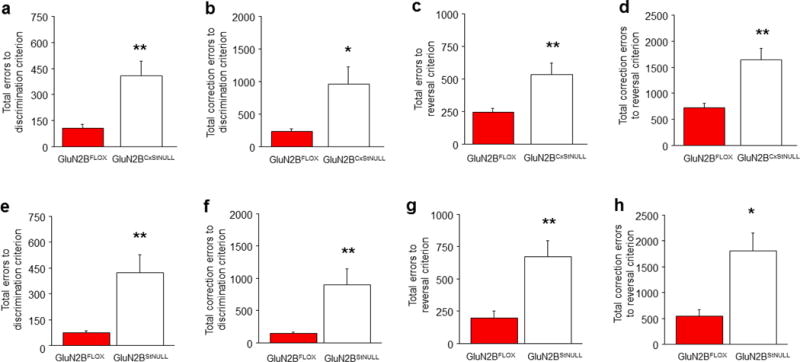

Impaired choice learning after corticostriatal GluN2B deletion

We next examined the role GluN2B as a putative mechanism instantiating plasticity at DS neurons to support choice learning and relearning. We began by employing a conditional mutant model in which GluN2B is postnatally deleted in forebrain principal neurons expressing CaMKII (GluN2BCxStNULL). To produce corticostriatal-wide loss of GluN2B, we took advantage of the observation that the CaMKII-promoter transgenic mouse (T29-1) produces increasingly widespread deletion as mice age. Quantitative western blots confirmed loss of GluN2B protein in mutant tissue from DS (t(7)=5.03, P<.01), mPFC (t(6)=2.46, P<.05), and dorsal hippocampus (t(7)=8.40, P<.01) (Figure S6A). In ~11 month old mutants, GluN2B mRNA was decreased in the cortex, striatum and CA1 hippocampus, but not other forebrain regions including thalamus and basolateral amygdala, relative to age-matched GluN2BFLOX littermate controls (Figure S6B).

Comparison of ~11 month old GluN2BCxStNULL mutants and age-matched GluN2BFLOX controls found no differences in operant pre-training prior to discrimination training, indicating normal gross motor and motivational functions. However, choice learning was impaired in these mutants, as demonstrated by more errors (t(16)=3.11, P<.01) (Figure 5A) and correction errors (t(16)=2.36, P<.05) (Figure 5B) to attain discrimination criterion, as compared to GluN2BFLOX controls. Choice-response and reward-retrieval latencies were no different between genotypes, further excluding a general performance deficit (Figure S1D). GluN2BCxStNULL mutants also made more errors (t(13)=3.30, P<.01) (Figure 5C) and correction errors (t(13)=4.08, P<.01) (Figure 5D) than GluN2BFLOX controls to attain reversal criterion, but again had normal choice-response and reward-retrieval latencies (Figure S1E). Underscoring the severity of the learning deficit, 5 of the 7 mutants failed to attain criterion even after extensive (60-session) reversal training.

Figure 5. Corticostriatal or striatal GluN2B deletion impairs choice learning.

GluN2BCxStNULL mice made more errors (a) and correction errors (b) to attain discrimination criterion, as compared to GluN2BFLOX controls (n per genotype: GluN2BFLOX=8, GluN2BCxStNULL=7). GluN2BCxStNULL mice made more errors (c) and correction errors (d) than GluN2BFLOX controls to attain reversal criterion. GluN2BStNULL mice made more errors (e) and correction errors (f) than GluN2BFLOX controls to attain discrimination criterion (n per genotype: GluN2BFLOX=10, GluN2BStNUL=9). GluN2BStNULL mice made more errors (g) and correction errors (h) to attain reversal criterion than GluN2BFLOX controls. Data are Means±SEM. *P<.05, **P<.01 vs. GluN2BFLOX controls.

Interestingly, impaired choice learning in these mutants did not extend to other operant settings. A naïve cohort of ~11 month old GluN2BCxStNULL mutants was tested on a task that required mice to touch a single visual stimulus for reward, without having to make a choice between two options. We found that GluN2BCxStNULL mutants acquired (Figure S7A) and extinguished (Figure S7B) this behavior in the same number of trials as age-matched GluN2BFLOX controls. A similar dissociation between intact performance in this task and impaired choice learning is also reported in the same choice task in mutants with brain-wide constitutive swap of the GluN2B and GluN2A C-terminal domains 41 or deletion of GluN2A 42, suggesting NMDARs are dispensable for simple forms of operant learning.

This set of experiments establishes a critical role for corticostriatal GluN2B in mediating choice learning and relearning.

Impaired choice learning after striatal GluN2B deletion

The various datasets accrued to this point in our study strongly implicate DS in choice learning and suggest that deficit in the GluN2BCxStNULL mutants was due to GluN2B loss in DS. However, the corticostriatal-wide nature of deletion in the GluN2BCxStNULL mutants precludes parsing of the relative contribution of GluN2B-expressing circuits in DS and cortex. We therefore generated a conditional mutant in which GluN2B is postnatally deleted in striatal cells expressing RGS9 (GluN2BStNULL) 11. Real-time-PCR confirmed significant loss of Grin2B in DS (t(5)=4.51, P<.01), not mPFC or dorsal hippocampus, in 4–6 month old GluN2BStNULL relative to age-matched GluN2BFLOX controls (Figure S8A). Western blots s;dp showed a modest, significant loss of GluN2B protein in tissue from DS (t(7)=5.03, P<.01), but not mPFC or dorsal hippocampus (Figure S8B).

There were no differences in operant pre-training prior to discrimination training in the GluN2BCxStNULL mice, but choice learning was severly impaired, as demonstrated by more errors (t(17)=5.57, P<.01) (Figure 5E) and correction errors (t(17)=3.65, P<.05) (Figure 5F) to attain discrimination criterion, relative to GluN2BFLOX littermates. Five of the 10 mutants failed to attain discrimination criterion even after extensive (60-session) training. The mutants also made more errors (t(12)=4.21, P<.01) (Figure 5G) and correction errors (t(12)=2.62, P<.05) (Figure 5H) than controls to attain reversal criterion. There was no indication of a general performance deficit, given choice-response and reward-retrieval latencies were normal (Figure S1F,G). These data confirm that GluN2B striatal cells are critical for choice learning and relearning.

Impaired choice learning after DS GluN2B antagonism

Although the CaMKII and RGS9 promoters circumvent developmental loss of GluN2B 43, prolonged GluN2B deletion may still have produced compensatory alterations in other subunits. Moreover, because GluN2B deletion was present at all testing stages, this approach cannot delineate the role of GluN2B in choice learning or shifting, and the expression of choice behavior once learned. Therefore, to compliment the mutant data, we infused the selective GluN2B antagonist Ro 25-6981 into the DS at different stages of relearning.

C57BL/6J mice were trained through Dlate and assigned to either vehicle or Ro 25-6981 groups matching for trials to Dlate. In 3 separate experiments, 2.5 μg Ro 25-6981 (0.5 μL per hemisphere) or an equivalent volume of vehicle was infused bilaterally into DS 15 min prior to sessions corresponding to Rearly, Rmid or Rlate. There was then 3 sessions without infusions to ensure behavior was altered by GluN2B antagonism and not artifactual to cannulation or infusion.

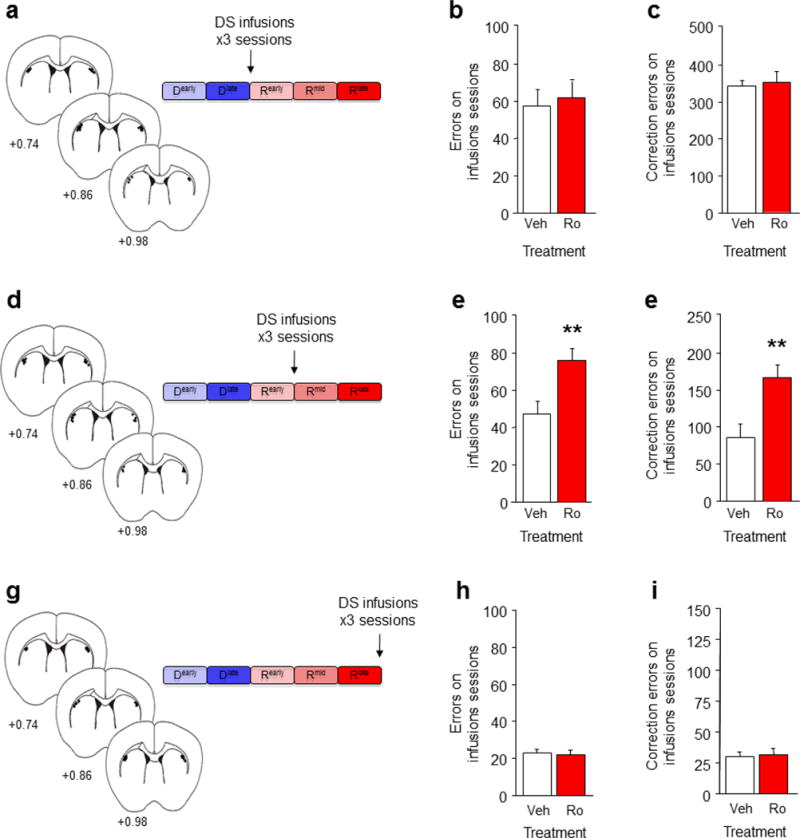

DS GluN2B blockade during Rearly (Figure 6A) did not alter total errors (Figure 6B) or correction errors (Figure 6C) over 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle controls (Figure S9A). This indicates that DS GluN2B are dispensable for initial choice shifting, presumably because DS-mediated choice relearning is not fully engaged at this stage and performance can be supported by other brain regions (e.g., cortical). By contrast, in a separate experiment blockade of GluN2B during Rmid (Figure 6D) increased errors (t(14)=3.04, P<.01) (Figure 6E) and correction errors (t(14)=3.29, P<.01) (Figure 6F), over 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle controls (Figure S9B). This confirms that GluN2B specifically localized within DS is critical for choice relearning and extends previous evidence that systemic GluN2B antagonism impairs various forms of learning 16–18,44–46.

Figure 6. Striatal GluN2B blockade impairs choice learning.

(a) Mice were trained to Rearly and given bilateral DS infusions of the GluN2B antagonist Ro 25-6981 on the next 3 sessions. Relative to vehicle infusion, DS GluN2B blockade at the Rearly stage did not affect the number of errors (b) or correction errors (c) made on the 3 infusion sessions. (d) Mice trained to Rmid and given bilateral DS infusions of Ro 25-6981 on the next 3 sessions. DS GluN2B blockade at the Rmid stage increased errors (e) and correction errors (f) on the 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle infusion. (g) Mice were trained to Rlate and given bilateral DS infusions of Ro 25-6981 on the next 3 sessions. DS GluN2B blockade at the Rlate stage did not affect the number of errors (h) or correction errors (i) made on the 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle infusion. n per treatment: Ro=7, Sal=11. Data are Means±SEM. **P<.01 vs. vehicle.

Finally, we asked whether DS GluN2B mediated choice behavior after relearning was complete. In mice trained to Rlate (Figure 6G), DS GluN2B blockade failed to increase errors (Figure 6H) or correction errors (Figure 6I) over the 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle (Figure S9C). Choice-response and reward-retrieval latencies were unaffected by GluN2B antagonism in this or any infusion experiment (Figure S1K–M). The absence of effects of GluN2B blockade on the expression of a learned choice is generally consistent with previous studies showing that infusion of a non-specific NMDAR antagonist in DS failed to alter a learned cue-driven cocaine-seeking response in rats 47. Other mechanisms, including AMPA and dopamine receptors, may be necessary for choice expression in our task, as found for other DS-mediated behaviors 47.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that functional inactivation of GluN2B within DS is sufficient to impair choice relearning and, moreover, that DS GluN2B is not necessary for either initial choice shifting or the expression of choice once learned. It remains to be shown whether this reflects a necessary role for GluN2B in mediating learning-related plasticity at DS synapses, or GluN2B regulation of the flow of critical information from other regions either to or from the DS.

Impaired choice shifting after cortical GluN2B deletion

Our finding that choice relearning is mediated by GluN2B-expressing circuits in DS still leaves open the question of whether parallel circuits in PFC regions implicated by our c-Fos data mediate choice shifting. Our first approach was to generate a cohort of mutant mice from the same line described above, but in which GluN2B deletion is largely restricted to CaMKII-expressing principal neurons in cortex by virtue of their younger age, as previously shown using in situ hybridization and quantitative immunoblot 43 (GluN2BCxNULL). We have previously reported loss of GluN2B protein and mRNA throughout cortex, as well as the dorsal hippocampal CA1 subregion in these mice 15. Here we obtained replicate in situ hybridization to show loss of GluN2B mRNA in these regions (Figure S8C).

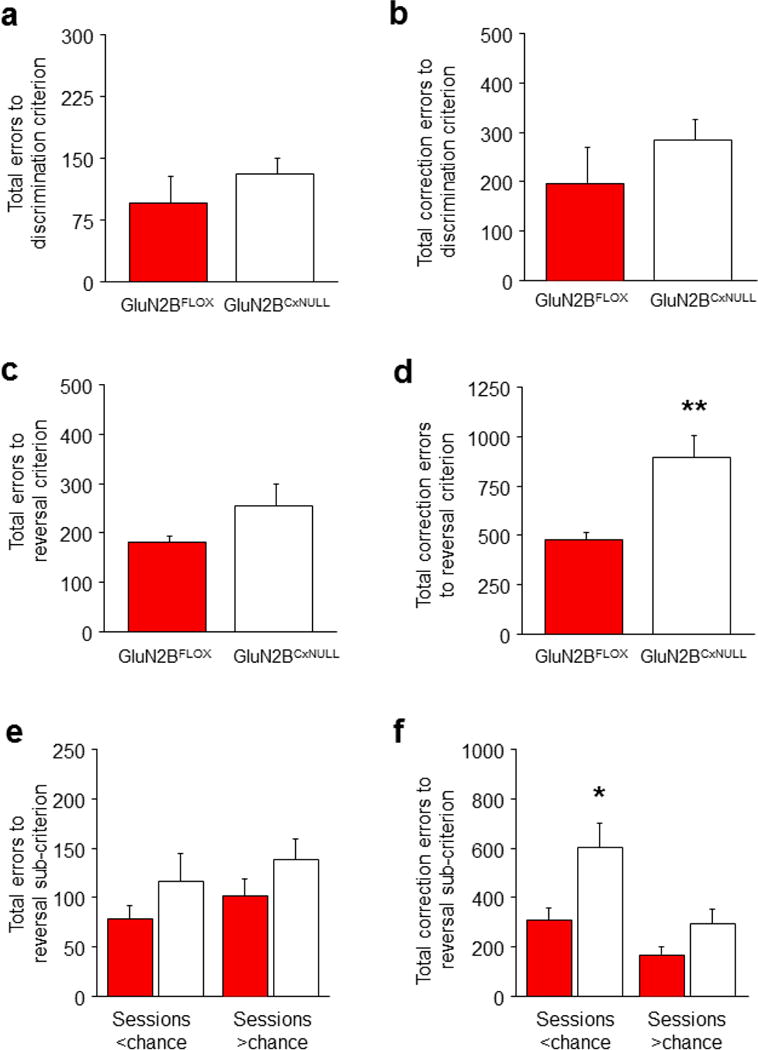

We found that GluN2BCxNULL mice were no different from age-matched GluN2BFLOX littermate controls on operant pre-training. These mutants also made the same number of errors (Figure 7A) and correction errors (Figure 7B) as controls to attain discrimination criterion, indicating intact choice learning. Although GluN2BCxNULL mutants also made a similar number of errors (Figure 7C) as GluN2BFLOX controls to attain reversal criterion, correction errors were increased (t(14)=3.63, P<.01) (Figure 7D). Choice-response and reward-retrieval latencies were no different between genotypes for discrimination or reversal (Figure S1H–J). This selective increase in correction errors during reversal suggests that the GluN2BCxNULL mutants were impaired on choice shifting. To explore this possibility further, we subdivided reversal performance into sessions where choice accuracy was below chance (<50% correct) versus above chance (>50% correct), equivalent to Rearly-to-Rmid and Rmid-to-Rlate phases, respectively. This revealed that the higher rate of correction errors in the mutants was specific to the Rearly-to-Rmid phase (t=2.75, df=14, P<.05) with no genotype difference at the Rmid-to-Rlate phase (Figure 7E), and no change in errors at either phase (Figure 7F).

Figure 7. Cortical GluN2B deletion impairs choice shifting.

(a) GluN2BCxNULL mice made a similar number of errors (b) and correction errors (c) as GluN2BFLOX controls to attain discrimination criterion. GluN2BCxNULL mice made more errors (d) and correction errors (e) to attain reversal criterion, in comparison to GluN2BFLOX controls. As compared to GluN2BFLOX controls, GluN2BCxNULL mice made a similar number of errors (f) but made more correction errors (g) on reversal sessions on which performance was below chance, but not above chance. n per genotype: GluN2BCxNULL=7, GluN2BFLOX=8. Data are Means±SEM. *P<.05, **P<.01 vs. GluN2BFLOX controls.

These mutant data are consistent with a selective impairment in choice shifting as a result of cortical GluN2B loss. Given the age-dependent nature of the loss of GluN2B in these mutants, it was, however, possible that the deficit was an artifact of the mutants being slightly older (with potentially some striatal loss) at the time of choice shifting than choice relearning. Excluding this possibility, we phenotyped another set of mice for discrimination at an older age (~5 months) and confirmed that there were no genotype differences in choice learning (errors from Dearly-to-Dlate: GluN2BFLOX=102±21, GluN2BCxNULL=131±23, correction errors: GluN2BFLOX=188±30, GluN2BCxNULL=276±67). Thus, we demonstrate a critical role of cortical GluN2B in choice shifting but not choice learning. The specificity of the effects of cortical GluN2B inactivation echoes previously observed learning phenotypes in these conditional GluN2B null mutants. For example, GluN2BCxStNULL mutants exhibited impaired corticohippocampal spatial memory, but normal striatal-mediated cue-guided learning, in the Morris water maze 15 that was coupled with impaired hippocampal synaptic plasticity (see also 19).

Impaired choice shifting after OFC GluN2B antagonism

Some of the same caveats discussed above for the GluN2BCxStNULL mutants apply to the data in the GluN2BCxNULL mutants, i.e., GluN2B is not temporally limited, nor spatially restricted to specific cortical subregions. We therefore sought to reinforce the mutant data with a pharmacological approach by testing the effects of OFC GluN2B blockade on choice performance.

OFC GluN2B blockade during Rearly (Figure 8A) did not alter the number of errors (Figure 8B) but increased correction errors (t(14)=3.61, P<.01) (Figure 8C), relative to vehicle controls (Figure S9A). By contrast, GluN2B blockade during Rmid (Figure 8D) had no effect on either errors (Figure 8E) or correction errors (Figure 8F) compared to vehicle controls (Figure S9B). Stimulus-response and reward-retrieval latencies was unaltered (Figure S1N,O).

Figure 8. Orbitofrontal GluN2B blockade impairs choice shifting.

(a) Mice trained to Rearly and given bilateral OFC infusions of the GluN2B antagonist Ro 25-6981 on the next 3 sessions. Relative to vehicle infusion, OFC GluN2B blockade at the Rearly stage did not affect the number of errors (b) but increased correction errors (c) made on the 3 infusion sessions. (d) Mice were trained to Rmid and given bilateral OFC infusions of the GluN2B antagonist Ro 25-6981 on the next 3 sessions. OFC GluN2B blockade at the Rmid stage did not affect errors (e) or correction errors (f) on the 3 infusion sessions, relative to vehicle infusion. n=7-9/treatment. Data are Means±SEM. **P<.01 vs. vehicle.

This pattern of deficits mimics the effect of subunit-non-selective NMDAR blockade on reversal in rats 48 and the phenotype of the GluN2BCxNULL mutants, and demonstrates that blockade of GluN2B in OFC is sufficient to disrupt choice shifting. This does not exclude a contribution from other PFC regions, e.g., our c-Fos analysis indicated that PL also showed activation during choice shifting stages, and exposure to stress facilitates choice learning in a manner prevented by PL infusion of BDNF 24. Restricted re-expression of NMDARs in PL also rescued impaired associative learning in mice lacking NMDARs on inputs to midbrain dopaminergic neurons 49. In turn, NMDARs expressed on dopaminergic neurons are crucial for habit behavior 50. Collectively, these various findings point to an indispensable role for NMDARs and, in the current study, specifically GluN2B, at multiple nodes within the corticostriatal circuitry subserving habit and other cognitive processes. An important avenue for future studies will be to elucidate how NMDARs regulate the functional and plasticity of circuits to integrate these various nodes of the system and regulate emergent behaviors such as choice.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Employing multiple approaches, the current study provides convergent support for a dynamic role of corticostriatal circuitry in choice learning and shifting. Our data also identifies a critical molecular mechanism subserving these functions by providing novel and compelling evidence of a double dissociation between OFC GluN2B in choice shifting and DS GluN2B in choice learning.

METHODS

Subjects

Male C57BL/6J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). GluN2BCxStNULL mice were generated as previously described 15. Briefly the GluN2B gene was disrupted by inserting a loxP site downstream of the 599 bp exon 3 or exon 5 (depending on transcript) and a neomycin resistance gene cassette flanked by 2 loxP sites upstream of this exon. The ‘129’ strain was used as the embryonic stem cell donor and C57BL/6J was used for blastocysts and as the genetic background for backcrossing. GluN2BFLOX mice were crossed with (C57BL/6J-congenic) transgenic mice expressing either Cre recombinase driven by the CaMKII promoter (T29-1 line) or Cre recombinase driven by the RGS9 promoter. With each Cre-mutant line, Cre+ hemizygous GluN2BFLOX (i.e., GluN2B excised) mice were crossed with Cre-GluN2BFLOX (non-excised controls) mice to produce mutant and control littermates for experimentation. Male and female mutants were used. Mice were housed in same-sex groupings (2–4 per cage, except for cannulated/implanted mice, which were 1 per cage) in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vivarium under a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on 0600 h) and tested during the light phase. The number of mice used in each experiment is given in the figure legends. Note that no statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes but our sample sizes are similar to those reported in previous publications 24. Experimenters were blind to all experimental conditions until all data was collected. Unless otherwise specified, mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the local Animal Care and Use Committee.

Behavioral procedures

Operant apparatus

All operant behavior was conducted in a chamber measuring 21.6 × 17.8 × 12.7 cm (model # ENV-307W, Med Associates, St. Albans, VT) housed within a sound- and light-attenuating box (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT). The grid floor of the chamber was covered with solid Plexiglas to facilitate ambulation. A pellet dispenser delivering 14 mg dustless pellets (#F05684, BioServ, Frenchtown, NJ) into a magazine was located at one end of the chamber. At the opposite end of the chamber there was a touch-sensitive screen (Light Industrial Metal Cased TFT LCD Monitor, Craft Data Limited, Chesham, U.K.), a house-light, and a tone generator. The touchscreen was covered by a black Plexiglas panel that had 2 × 5 cm windows separated by 0.5 cm and located at a height of 6.5 cm from the floor of the chamber. Stimuli presented on the screen were controlled by custom software (‘MouseCat’, L.M. Saksida) and visible through the windows (1 stimulus/window). Nosepokes at the stimuli were detected by the touchscreen and recorded by the software.

Stage analysis of discrimination and reversal performance

Pairwise visual discrimination and reversal learning was assessed in C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks at beginning of testing) as previously described 22,24,42,51. Mice were first slowly reduced and then maintained at 85% free-feeding body weight. Prior to testing, mice were acclimated to the 14 mg pellet food reward by provision of ~10 pellets/mouse in the home cage for 1–3 days. Mice were then acclimated to the operant chamber and to eating out of the pellet magazine by being placed in the chamber for 30 min with pellets available in the magazine. Mice eating 10 pellets within 30 min were moved onto autoshaping.

Autoshaping consisted of variously shaped stimuli being presented in the touchscreen windows (1 per window) for 10 sec (inter-trial interval (ITI) 15 sec). The disappearance of the stimuli coincided with delivery of a single pellet food reward, concomitant with presentation of stimuli (2-sec 65 dB auditory tone and illumination of pellet magazine) that served to support instrumental learning. Pellet retrievals from the magazine were detected as a head entry and, at this stage of pre-training, initiated the next trial. To encourage screen approaches and touches at this stage, nosepokes at the touchscreen delivered 3 pellets into the magazine.

Mice retrieving 30 pellets within 30 min were moved onto pre-training. During pre-training mice first obtained rewards by responding to a (variously-shaped) stimulus that appeared in 1 of the 2 windows (spatially pseudorandomized) that remained on the screen until a response was made (‘respond’ phase). Mice retrieving 30 pellets within 30 min were next required to initiate each new trial with a head entry into the pellet magazine. In addition, responses at a blank window during stimulus presentation now produced a 15 sec timeout (signaled by extinction of the house light) to discourage indiscriminate screen responding (‘punish’ phase). Errors were followed by correction trials in which the same stimulus and left/right position was presented until a correct response was made. Mice making≥75% (excluding correction trials) of their responses at a stimulus-containing window over a 30-trial session were moved onto discrimination.

For discrimination learning, 2 novel approximately equiluminescent stimuli were presented in a spatially pseudorandomized manner over 30-trial sessions (15 sec ITI). Responses at 1 stimulus (correct) resulted in reward; responses at the other stimulus (incorrect) resulted in a 15 sec timeout (signaled by extinction of the house light) and were followed by a correction trial. Stimuli remained on screen until a response was made. Designation of the correct and incorrect stimulus was counterbalanced across groups. Mice were trained to a criterion of≥85% correct responding (excluding correction trials) over 2 consecutive sessions.

Reversal training began on the session after discrimination criterion was attained. Here, the designation of stimuli as correct versus incorrect was reversed for each mouse. Mice were trained on 30-trial daily sessions (as for discrimination) to a criterion of≥85% correct responding (excluding correction trials) over 2 consecutive sessions.

The following dependent measures were taken during discrimination and reversal: percent correct responding (=[correct responses/30 session-trials]*100), errors (=incorrect responses made), correction errors (=correction trials made), time to response (=time from trial initiation to touchscreen response), and time to reward (=time from touchscreen response to reward retrieval). In addition, for the initial experiment characterizing the major task performance stages in C57BL/6J mice (see Figure 1), the average length of strings of consecutive errors or correct responses was also measured. Here and elsewhere in the study, behavior measures were compared across the 5 task performance stages using analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a statistically conservative post hoc test (Newman Keuls). Data met the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance for analysis with parametric tests. No attempt was made to exactly equate the number of animals in each experimental group.

Regional mapping of neuronal activation

This experiment mapped patterns of regional neuronal activation associated with choice learning and shifting, via immunocytochemical staining for the immediate-early gene, c-Fos. Separate groups of C57BL/6J mice were trained to 1 of 5 possible stages of discrimination or reversal performance (Figure 1A): Dearly=first session of discrimination/performance at chance, Dlate=final session of discrimination/performance at criterion, Rearly=first session of reversal/performance highly perseverative, Rmid=reversal session when performance was around chance (i.e., 50% correct), Rlate=final session of reversal/performance at criterion. Two hr after the start of the final session, mice were deeply anesthetized with an overdose of ketamine/xylazine (200 mg/kg) and transcardially perfused with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed at 4°C overnight in 4% formaldehyde in PBS and then rinsed in PBS for 2–4 hr.

Fifty μm thick coronal sections were cut into PBS on a vibratome and processed for c-Fos immunoreactivity based upon methods previously described 52. Briefly, sections were permeabilized in PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS-T) for 1 hr, blocked with 5% BSA in PBS-T for 4 hr and incubated on a platform rocker overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-Fos (sc-52) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) diluted 1 mg/mL in PBS-T. Negative controls were prepared by omitting the primary antibody. Sections were washed 3 times for 1 hr in PBS-T and incubated overnight at 4°C with Alexa 488 goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) diluted 1:1000 in PBS-T. They were then washed 3 times for 1 hr in PBS-T and mounted.

Sections were imaged with a 32X, 0.4 NA objective using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 epiflourescence microscope (482/35 excitation filter, 505 dichroic, 540/25 emission filters). Images were collected using the same exposure time (determined by control signal intensity) using a CCD camera (Axiocam) combined with the Axiovision software (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen GER). Care was taken not to repeatedly expose the sections in order to reduce photobleaching and sections were stored in the dark during all procedures beginning with the secondary antibody treatment. Images were then adjusted using ImageJ (version 1.38x) by background subtraction and threshold adjustment, constant for each region. Circular particles larger than 20 μm2 in diameter were automatically counted and recorded. For each region, c-fos was an average of counts from a 360 × 460 μm region, measured in duplicate sections.

Thirteen brain regions were analyzed: agranular insular cortex (AP=+2.10, ML=±2.25, DV=−3.25), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (AP=+2.10, ML=±1.50, DV=−3.25), medial orbitofrontal cortex (AP=+2.10, ML=±0.25, DV=−3.25), primary motor cortex (AP=+2.10, ML=±2.00, DV=−1.75), prelimbic cortex (AP=+1.54, ML=±1.33, DV=−2.50), infralimbic cortex (AP=+1.54, ML=±1.33, DV=−3.00), the dorsal CA1 subregion of the hippocampus (AP=−1.46, ML=±1.00, DV=−1.50), dorsomedial striatum (AP=+1.10, ML=±0.80, DV=−3.00), dorsolateral striatum (AP=+1.10, ML=±2.10, DV=−3.00), nucleus accumbens shell (AP=+1.54, ML=±0.50, DV=−4.80), nucleus accumbens core (AP=+1.54, ML=±0.75, DV=−4.50), basolateral nucleus of the amygdala (AP=−1.46, ML=±3.00, DV=−4.65), central nucleus of the amygdala (AP=−1.46, ML=±2.40, DV=−4.30). The number of c-fos-positive cells was compared across the 5 task performance stages using ANOVA followed by Newman Keuls post hoc tests.

Excitotoxic dorsolateral striatum lesions

This experiment assessed the functional contribution of the dorsolateral striatum to choice learning by making bilateral lesions of this region, prior to discrimination training. After completing pre-training, C57BL/6J mice were assigned to lesion or sham groups by matching to trials to complete pre-training. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic alignment system (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). The fiber-of-passage-sparing excitotoxin NMDA or saline was infused into 4 sites (2 sites per hemisphere: 1 anterior and 1 posterior) at the coordinates: AP +1.18, +0.22; ML±2.4,±3.0; DV −2.5. After 7–10 days of recovery, body weight reduction resumed and mice were given post-surgery reminder sessions to ensure retention of pre-training criterion. Discrimination training was conducted as above. Behavioral measures (as above) were compared between sham and lesion groups using 2-tailed (as elsewhere) Student’s t-test.

Given the role of dorsolateral striatum in controlling motor functions, after the completion of discrimination testing, an open field test was conducted to provide an additional control measure for locomotor function in the lesioned mice. Mice were placed in the perimeter of a 40 × 40 × 35 cm square arena (illuminated to 50 lux) constructed of white Plexiglas in the perimeter and allowed to explore the apparatus for 30 min, as previously described 53. Testing was conducted under 65 dB white noise to minimize external noise disturbances (Sound Screen, Marpac Corporation, Rocky Point, NC). Total distance traveled in the whole arena and time spent in the center (20 × 20 cm) was measured by the Ethovision videotracking system (Noldus Information Technology Inc., Leesburg, VA).

Mice were sacrificed at the completion of testing to verify the location and extent of the lesions. Mice were terminally anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde solution in phosphate buffer. Brains were removed and 50 μm coronal sections cut with a vibratome (Classic 1000 model, Vibratome, Bannockburn, IL) and then stained with cresyl violet. Estimates or the maximum and minimum extent of lesions were estimated with reference to a mouse brain atlas and the aid of a microscope. Mice with lesions outside the DLS were excluded from the analysis.

Performance transfer from operant training to motor learning

Training on cognitive and motor tasks that heavily recruit certain brain regions can facilitate performance on separate tasks that are mediated by the same regions 54–56. This experiment tested for performance transfer from choice testing to a dorsal striatal-mediated motor learning task 36. Separate groups of C57BL/6J mice were trained (as above) to either 1) pre-training criterion (Pre-D), 2) discrimination criterion (Dlate) or 3) reversal criterion (Rlate). The aim was to test the differential effects of prior experience with operant training but no-choice learning, training+choice learning or training+choice learning+choice shifting, rather than the accumulated amount of operant testing or reinforcement. Therefore, the 3 groups were matched for the total number of sessions from the beginning of operant training until the motor learning test (=26.1±0.7 sessions) by giving the pre-training group an additional 20.0±0.7 sessions after reaching criterion, and the discrimination group an additional 6.8±1.3 sessions.

One day after the completion of operant testing, motor learning was assessed using the accelerating rotarod, as previously described 57. Mice were placed on a 7-cm-diameter dowel (Med Associates rotarod model ENV-577) rotating at 4 rpm and accelerating at a constant rate of 8 rpm/min up to 40 rpm. The latency to fall to the floor 10.5 cm below was recorded by breaking photocell beams. Mice were given 10 consecutive training trials (30-sec inter-trial interval), with a cutoff latency of 300 sec for a given trial. Motor learning was calculated as the difference in latency from trial 1 to 10. Groups were compared using ANOVA.

In vivo dorsal striatum neuronal recordings

The specific role of dorsal striatum in choice behavior was investigated via in vivo neuronal recordings made during choice learning and shifting. After completing pre-training, C57BL/6J mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic alignment system (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA) for implantation of a microelectrode array 58. The array (fabricated by Innovative Neurophysiology, Durham, NC) comprised 16x 35 μm-diameter tungsten microelectrodes arranged into 2 rows of 8 (150 μm spacing between microelectrodes within a row, 1000 μm spacing between rows). One row was placed in lateral dorsal striatal and the other central-medial (Figure 3A), with rows running lengthwise anterior to posterior (targeting coordinates for center of array: AP +0.75, ML +1.60, DV −2.75). After 7–10 days of recovery, body weight reduction resumed and mice were given post-surgery reminder sessions to ensure retention of pre-training criterion. Discrimination training, followed by reversal training, was conducted as above.

Neuronal activity was recorded using the Plexon Inc (Dallas, Texas) Multichannel Acquisition Processor during 1 session corresponding to each of the 5 performance stages described above. Extracellular waveforms exceeding a set voltage threshold were digitized at 40 kHz and stored on a PC. Waveforms were manually sorted using principal component analysis of spike clusters and visual inspection of waveform and inter-spike interval 36. Neuronal activity was timestamped around 4 × 3-sec event epochs (trial initiation, pre-choice, choice, reward receipt), separately for correct and error trials. Spike and timestamp information was integrated and analyzed using NeuroExplorer (NEX Technologies, Littleton, MA).

To measure the average activity of the recorded population, activity for each neuron was Z-score normalized to the average firing rate of that neuron across all events and presented in 50 msec timebins. Changes in Z-scored firing across performance stages were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA, with repeated measures for time. Z-scored firing of individual cells is also shown. To examine the event-related firing of individual units, units with Z-scores exceeding either>1.0 or<1.0 were designated as event-related. The percentage of recorded units classified as event-related were calculated at each 50 msec timebin. The Pearson’s r correlation between firing during correct responses and reward-retrieval was measured by summing the Z values during the entirety of each epoch.

At the completion of testing, array placement was verified by electrolytic lesions made by passing 100 μA through the electrodes for 20 sec using a current stimulator (S48 Square Pulse Stimulator, Grass Technologies, West Warwick, RI). Brains were removed, 50 μm coronal sections cut with a vibratome (Classic 1000 model, Vibratome, Bannockburn, IL) and stained with cresyl violet. Placement was estimated with reference to a mouse brain atlas and the aid of a microscope. Mice with placements outside the DLS were excluded from the analysis.

Ex vivo dorsal striatum slice recordings

Here, changes in synaptic plasticity in dorsal striatum neurons were analyzed, ex vivo, as a function of choice learning and shifting. C57BL/6J mice were trained to 1 of the 5 discrimination or reversal stages defined above. Two hr after the start of the final session, mice were anesthetized by halothane or isoflurane inhalation. The brain was rapidly removed and placed in ice-cold cutting solution (in mM): 194 Sucrose, 30 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 10 Glucose, pH 7.3, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, mOsm 320. Coronal sections (250 μm thick) were cut with an Integraslice 7550 vibratome (Campden Instruments, Loughborough, UK) and incubated in ice-cold modified aCSF and transferred immediately to normal aCSF (in mM): 124 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 10 Glucose, 2 CaCl2, pH 7.3, equilibrated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 34ºC, for 30 min and then at room temperature for at least 30 min before the experiment. Slices were maintained at 28–32 during the experiment.

Extracellular field recordings were performed with micropipettes (2.5–5 MO) filled with 1 M NaCl solution, as previously described 36. Field potentials were evoked by constant current stimulation delivered via a bipolar twisted Teflon-coated tungsten electrode placed in the striatum. Individual stimulus pulses of 0.01 msec duration were generated by a Grass 44 stimulator through a Grass optical isolator. Input/output (I/O) relationship was examined by stimulating at intensities from 0.1 to 1.5 mA (2 stimuli at each intensity) with an interstimulus interval of 30 sec, and recording population spike (PS) amplitude. To measure PS amplitude before and after high frequency stimulation (HFS), responses to stimuli (1/30 sec) that evoked a PS that was approximately half the amplitude of the maximal evoked response were recorded for at least 10 min prior to the first HFS trains (baseline period) and for 20 min after each set of trains. LTD was induced via high frequency stimulation consisting of 3 × 1 sec-trains of 100 pulses (each pulse=0.01 msec) delivered at 100 Hz (10 sec inter-train interval) with the stimulus intensity set a 1.5 mA during the trains. The peak amplitude of the negative-going PS was measured relative to the positive-going field potential component just prior to PS onset, using cursors in Clampfit v8.0.

Corticostriatal GluN2B deletion

The contribution of corticostriatal GluN2B circuits was first assessed in mutant mice lacking GluN2B in neurons in these brain regions, as well as dorsal CA1 hippocampus. This was achieved by crossing GluN2BFLOX mice with CaMKII-driven Cre transgenic mice, and testing the progeny at an age when the deletion has spread from cortex and CA1 hippocampus to striatum (see main text for further details). GluN2BCxStrNULL mice and age-matched controls were tested for choice discrimination (age range=28–36 weeks) and then choice reversal (age range=30–42 weeks) as above.

Western blot

To confirm and quantify loss of GluN2B, another set of ~11 month-old mice were used to quantify GluN2B protein levels via Western blot. Tissue from mPFC, dorsal hippocampus and dorsal striatum was dissected from frozen brains with a 2 mm-diameter micro punch. Tissue was homogenized by sonication on ice in lysis buffer (10mM NaPPi, pH7.5, 20mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 2mM EDTA, 2mM EGTA, 1mM NaF, 1mM Na3VO4, 2mM DTT) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Supernatant was obtained by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10min at 4ºC. Protein concentration was determined with Micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein extracts were denatured in 2X Laemmli buffer (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 20 μg of protein per well were loaded for SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA), blocked with 5% milk in TBS with 0.05% Tween-20, and blotted with rabbit polyclonal anti-GluN2B (1:2000, Chemicon/Millipore, catalogue numbers 07-632, AB1548) followed by the HRP-labeled anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Immunoreactivity was detected with ECL plus (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Western blots results combined from 4 biological replicates were quantified with KODAK Molecular Imaging Software (Carestream Health Molecular Imaging, New Haven, CT) and normalized by anti-β-tubulin (1:10k; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) immunoreactivity. Genotypes were compared using Student’s t-test.

In situ hybridization

Brains of mice aged ~11 months (range=45–48 weeks) were analyzed for GluN2B mRNA expression using in situ hybridization, as previously described 15. Fresh-frozen brain sections (14 μm in thickness) were prepared in the parasagittal or horizontal plane with a cryostat, and mounted onto silane-coated glass slides. Sections were post-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min followed by 0.2 M HCl for 10 min. After rinsing, sections were further incubated in 0.25% acetic anhydride and 0.1 M triethanolamine for 10 min to avoid non-specific binding of the probe. Following dehydration with ethanol, hybridization was performed at 55°C for 18 hr in a hybridization buffer containing 50% formamide. For detection of GluN2B mRNA, a complementary RNA (cRNA) probe, derived from the whole exon 2 sequence (599 bp) of mouse GluN2B genome, was labeled with [33P]UTP (5 × 105 cpm), and added to the hybridization buffer. Brain sections were serially washed at 55°C with a set of SSC buffers of decreasing strength, the final strength being 0.2x and then treated with Rnase A (12.5 μg/mL) at 37°C for 30 min. The sections were exposed to X-ray film (Kodak BioMax MR) for 2 days and were dipped in nuclear emulsion (Kodak NTB) for exposure for 3–4 weeks. Images were collected with a digital camera attached to a microscope.

Cortical GluN2B deletion

The consequences of loss of GluN2B in cortical (and dorsal CA1 hippocampal), but not striatal, neurons, for choice learning and shifting, was tested by crossing GluN2BFLOX with CaMKII-Cre mutants at an age at which deletion has not spread to striatum 15. GluN2B mutant mice and age-matched floxed controls were tested for choice discrimination (age range=10–15 weeks) and then choice reversal (age range=13–20 weeks), as above. Behavior was compared between genotypes using Student’s t-test.

Striatal GluN2B deletion

The consequences of loss of GluN2B in striatal neurons for choice learning and shifting, was tested by crossing GluN2BFLOX with RGS9-Cre transgenic mice 11. GluN2BStrNULL mice and age-matched floxed controls were tested for choice discrimination (age range=12–18 weeks) and then choice reversal (age range=16–24 weeks), as above. Behavior was compared between genotypes using Student’s t-test.

Real time-PCR

Tissue from mPFC, dorsal striatum and dorsal hippocampus was dissected from frozen brains with a 1 or 2 mm-diameter micro punch. Punches from 3 mice were pooled together and kept in RNAlater solution (Ambion). Total RNA was isolated with RNeasy kit (QIAGEN) followed by DNase I treatment (Invitrogen) for eliminating the DNA in order to purify RNA. Reverse transcription was performed with 1 μg of total RNA using the Iscript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) and a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). Expression of mouse Grin2B gene (GluN2B receptor) was quantified with QuantiTect Primer Assay (QT00169281) and Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) using a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). Relative GRIN2B expression was quantified by normalization with the QuantiTect Primer Assay against mouse beta-Actin (QT01136772).

Western blot

Tissue from mPFC, dorsal striatum and dorsal hippocampus was dissected from frozen brains with a 1 or 2 mm-diameter micro punch. Tissue was homogenized by sonication on ice in RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Homogenates were kept on ice for 30 min for lysis and protein concentration was determined with Bradford Method using bovine serum albumin as a standard. Protein extracts were mixed (1:1) with Laemmli sample buffer and β-Mercaptoethanol and denatured by heating for 10 min at 85°C. 20 µg of protein per well were loaded on 4–12% polyacrylamide gel (Criterion XT Bis-Tris Gel) and run for 2h at 100 V in a Criterion cell. Following the electrophoresis, gels were equilibrated and proteins were transferred onto Nitrocellulose membrane (pore size 0.45 μm) with Trans-Blot SD a semi-dry electrophoretic Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 30 min at 25 V. Blots were blocked with 5% milk in TBST (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 1 h at room temperature and blotted overnight at 4°C with mouse monoclonal anti-GluN2B primary antibody (1:1000 NeuroMab# 75-097). Mouse monoclonal beta actin (1:5000, catalog # ab8226; Abcam) was used as a loading control. Blots were then washed 3 times for 10 min in TBST, and incubated for 1 hr at room temperature appropriately with HRP-labeled mouse secondary antibody (1:5000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, SC-2969). Immunoreactivity was detected with SuperSignal West Dura chemiluminescence detection reagent (Thermo Scientific Rockford, IL) and collected using a Kodak Image Station 4000R. Net intensity values combined from 4 biological replicates were determined using the Kodak MI software and were normalized to total beta actin. Genotypes were compared using Student’s t-test.

Dorsolateral striatal GluN2B antagonism

This series of experiments were conducted to delineate the role of GluN2B-expressing neurons in dorsolateral striatum in choice shifting, choice learning, and the expression of learned choice behavior, during reversal testing.

Effects on choice shifting

After attaining discrimination criterion, C57BL/6J mice were assigned to drug or vehicle groups by matching to trials to complete discrimination. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxic alignment system (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Guide cannulae (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) were inserted bilaterally (AP +0.85, ML±2.35, DV −1.75) stabilized with dental cement. After 7–10 days of recovery, body weight reduction resumed and mice were given post-surgery reminder sessions to ensure retention of discrimination criterion. Reversal testing was conducted as above, except that the GluN2B-selective antagonist Ro 25-6981 (2.5 μg per side in a volume of 0.5 μl) (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or an equivalent volume of saline vehicle was infused bilaterally into dorsolateral striatum prior to the first 3 reversal sessions, i.e., when choice shifting was most strongly taxed. Solutions were infused with the aid of a dual syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA) at a slow rate over 5 min via injectors that projected into the tissue 1 mm beyond the tip of the cannula. The injectors were left in place for 3 min to ensure full diffusion. Mice were tested 15 min later. From the fourth session onwards, reversal testing continued to criterion with no further infusions.

Effects on choice learning

A set of naïve C57BL/6J mice were trained to discrimination criterion and implanted with guide cannulae, as above. To test the effects of dorsolateral striatal GluN2B blockade when choice learning was evident, mice were trained to chance performance and Ro 25-6981 or vehicle was infused prior to the next 3 reversal sessions. Thereafter, reversal testing continued to criterion without further infusions.

Effects on learned choice expression

Another set of naïve C57BL/6J mice were trained to discrimination criterion and implanted with guide cannulae, as above. These mice were trained to reversal criterion and then infused with drug or vehicle over another 3 sessions, in order to test whether dorsolateral striatal GluN2B blockade affects the expression of the choice behavior, once learned. After the infusion sessions, reversal testing continued for another 3 no-infusions sessions to ensure retention of learned choice.

For all three experiments, trials per session were doubled from 30 to 60 in order to minimize the number of potentially tissue-damaging infusions. The sum of errors and correction errors, and the average stimulus-response and reward-retrieval times, during the infusion sessions was compared between drug and vehicle groups using Student’s t-test. In addition, the effect of drug treatment on choice accuracy on each of the 3 infusion sessions and subsequent 3 (i.e., no-infusion) sessions was analyzed using ANOVA, with repeated measures for session, followed by Newman Keuls post hoc tests.

At the completion of testing brains were removed and 50 μm coronal sections cut with a vibratome (Classic 1000 model, Vibratome, Bannockburn, IL) and stained with cresyl violet. Cannulae placements were estimated with reference to a mouse brain atlas and the aid of a microscope. Mice with placements outside the DLS were excluded from the analysis.

Orbitofrontal cortical GluN2B antagonism

These experiments were conducted to examine the contribution of GluN2B-expressing neurons in orbitofrontal cortex to choice shifting and choice learning using the same pharmacological approach as described for dorsolateral striatum. Procedures were the same as above with the guide cannulae bilaterally targeted to orbitofrontal cortex (AP +2.80, ML±1.35, DV −1.80).