Abstract

Purpose

To examine the association between early adolescent anxiety disorders and self-esteem development from early adolescence to young adulthood.

Methods

Self-esteem was measured at mean ages 13, 16 and 22 for 821 participants from the Children in the Community Study, a population-based longitudinal cohort. Anxiety disorders were measured at mean age 13 years. Multilevel growth models were employed to analyze the change in self-esteem from early adolescence to young adulthood and to evaluate whether adolescent anxiety disorders predict both average and slope of self-esteem development.

Results

Self-esteem increased during adolescence and continued to increase in young adulthood. Girls had lower average self-esteem than boys, but this difference disappeared when examining the effect of anxiety. Adolescents with anxiety disorder had lower self-esteem, on average, compared with healthy adolescents (effect size (ES) =−0.35, p<0.01). Social phobia was found to have the greatest relative impact on average self-esteem (ES=−0.30, p<0.01), followed by overanxious disorder (ES=−0.17, p<0.05), and simple phobia (ES=−0.17, p<0.05). Obsessive compulsive-disorder (OCD) predicted a significant decline in self-esteem from adolescence to young-adulthood (

=−0.1, p<0.05). Separation anxiety disorder was not found to have any significant impact on self-esteem development.

=−0.1, p<0.05). Separation anxiety disorder was not found to have any significant impact on self-esteem development.

Conclusions

All but one of the assessed adolescent anxiety disorders were related to lower self-esteem, with social phobia having the greatest impact. OCD predicted a decline in self-esteem trajectory with age. The importance of raising self-esteem in adolescents with anxiety and other mental disorders is discussed.

Keywords: Anxiety disorder, Self-esteem development, Adolescence, Multilevel growth modeling, Longitudinal

Introduction

Recent theoretical and empirical work has identified the transition from adolescence to young adulthood as a period with distinct characteristics that is important for the understanding of human development [1]. Adolescence is a developmental period marked by rapid maturational changes, shifting societal expectations and conflicting role demands, and self-esteem plays a critical role in this process. Studies on self-esteem development have found moderate increases during adolescence and slower increases during young adulthood [2], while other studies report that self-esteem declines during adolescence, partially explained by adolescent concerns with self-image and related issues associated with puberty, but increases gradually throughout adulthood [3]. From a theoretical standpoint, changes in self-esteem coincide with major life events or transitions [4]. Nevertheless, there is little agreement regarding the self-esteem development through young adulthood due to few longitudinal-based studies conducted on a non-clinical adolescent population [2, 5]. Factors known to influence self-esteem include higher education, positive family communication and low risk taking [2, 6-7]. Given the negative implications of poor self-esteem in adolescents, including poor health and criminal behavior [8], understanding self-esteem development from adolescence to adulthood and the factors which influence its trajectory can aid in the development of interventions designed to improve self-esteem.

Anxiety disorders are the most common of all the mental disorders [9]. The prevalence rate in the general population has been estimated at 11% and anxious people have contact with mental health professionals at rates that are higher than any other mental disorder except schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [10]. Among adolescents, lifetime prevalence for any anxiety disorder is about 32% and 9.1% for social phobia [11]. Previous research concerning this topic has focused on examining the association between demographic and socioeconomic (SES) factors and self-esteem development [2, 7, 12]. However, the relationship between self-esteem and anxiety disorders is less frequently acknowledged, discussed and understood in clinical literature [4]. Greenberg et al [13] reported that anticipatory anxiety was buffered by raised self-esteem. Studies [14–15] found that subjects with anxiety disorders had lower levels of self-esteem, compared to non-clinical controls. Moreover, no research has examined the role of various categories of anxiety disorders on self-esteem development from a longitudinal perspective. The approach of using early adolescent anxiety disorder for predicting self-esteem development is unique as low self-esteem is typically considered a risk factor for mental illness such as depression, commonly occurring with anxiety at high rates among adolescents [16-18].

The purpose of the present study is to examine the relative impact of adolescent anxiety disorders on self-esteem development from adolescence to young adulthood. Adolescent anxiety disorders examined include overanxious disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), simple phobia, social phobia, and separation anxiety disorder. For clarification, overanxious disorder as a diagnosis has been replaced by generalized anxiety disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). Self-esteem was measured across three time points beginning from early adolescence and ending in adulthood.

Methods

Participants and Study Procedures

Data were drawn from the Children in the Community (CIC) study, based on a randomly sampled cohort of over 800 families with at least one child between ages one to ten residing in two upstate New York counties in 1975 [19]. The study sample is comprised of one randomly selected child per family, and is demographically representative of children living in the northeastern US at that time. The regions were selected for their similarities in racial distribution and socioeconomic status to that of the entire United States. It is one of the few studies that have conducted systematic, interview-based assessments of psychopathology over 30 years beginning in childhood in randomly-ascertained individuals. Data for the current study are based on 821 subjects (49% female, 51% male) interviewed in 1983 (wave 2), at a mean age of about 13, for their anxiety disorders assessment and self-esteem, and followed measures of self-esteem in 1986 (wave 3, mean age of 16) and 1992 (wave 4, mean age of 22). Participants ranged from 9 years of age to about 28 years of age, with an average of about 17 years of age. Study procedures were conducted in accordance with appropriate institutional guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. A National Institute of Health Certificate of Confidentiality has been obtained for these data. Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants after the interview procedures were fully explained. Additional information regarding study methods is available on the study website (www.nyspi.org/childcom).

Measures

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety disorders were assessed with the diagnostic interview schedule for children [20]. In 1983 we administered the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC)-I separately to children and a parent, usually their mothers. Home interviews were carried out by two interviewers who were blind to the responses of the other respondent and to any prior data. Data from parent and child were combined by computer algorithms in two ways. First, we created continuous scales for each disorder defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association [21] by summing responses to disorder-specific questions on symptoms and associated impairment for each respondent. By and large these scales have acceptable internal consistency reliability, ranging from 0.6 to over 0.9 [22], despite the absence of concern about such reliability in the definition of these disorders. DSM-III-R diagnoses for adolescents were made based on criteria met by either youth or parent report on the DISC-I but also required that the sum of the mother and adolescent symptom scales for the disorder to be at least one standard deviation above the sample mean. This decision to consider either respondent's symptom indication as positive is consistent with the consensus of the field that sensitivity is thereby ensured [23], while the use of the additional criterion based on the pooled scales enhances the specificity of the diagnoses. The type of anxiety disorders noted are overanxious disorder, OCD, simple phobia, social phobia and separation anxiety disorder.

Self-Esteem

Self-esteem was measured in 1983 (mean age of 13), 1986 (mean age of 16) and 1994 (mean age of 22). Four items indexed global self-esteem in each protocol: (i) I feel that I have a number of good qualities; (ii) I feel that my life is very useful; (iii) I am a useful person to have around; and (iv) I feel that I do not have much to be proud of (reversed). The items were rated from 1 (false) to 4 (true), and the internal consistency of the scale formed by summing them was 0.64 in adolescence and 0.69 in young adulthood [24].

Demographic Control Variables

Covariates include gender, race, and SES. Family SES was measured as a standardized sum of standardized parental education, occupational status, and family income.

Data Analysis

A linear mixed-effect (LME) model [25] was used to examine the self-esteem trajectory. This approach was taken given the outcome, self-esteem, was repeatedly measured over time (age) [25]. In all models, both the intercept and slope were considered as random effects allowing for parameter estimations both at the intra-individual and inter-individual levels [26]. We investigated the following four scenarios of models. First, a basic unconditional LME model was assessed with age as the only variable to estimate the self-esteem trajectory. Age was centered at the mean (17 years) for all analyses. Secondly, gender, race and SES were added to the basic model to determine any potential influence on self-esteem development. These variables were used as controls for remaining analyses.

The third LME model compared any anxiety disorder (n=225) to those without mental disorders (healthy adolescents, n=427). Lastly, we examined the relative impact of the classifications of anxiety disorders – overanxious disorder (n=111), OCD (n=43), simple phobia (n=90), social phobia (n=65), and separation anxiety disorder (n=67). All anxiety classifications were included in this model to control for co-morbidity impact. Correlation between anxiety disorders is low. Multicollinearity was assessed and considered not to be a concern. Youth in the anxiety groups are considered to have at least the specified classification of anxiety disorder, but may have other mental health disorders. Each anxiety disorder group was compared to those without the specified disorder. Interaction effects between anxiety disorders and age were assessed before deciding on a final model. The PROC MIXED procedure in SAS statistical software was used in all analyses.

Results

Profile of Sample

Self-esteem was measured in 756 of the 821 subjects during wave 2, 750 at wave 3 and 751 at wave 4. About 51% of the participants were male and 49% were female; over 91% were White and about 9% of the subjects were Black. Over 27% of all participants had at least one anxiety disorder, not distinguishing from other Axis I disorders. About 14% of all participants were reported to have at least overanxious disorder; about 5% have OCD; 11% have simple phobia; 8% reported social phobia; 8% with separation anxiety. Average observed self-esteem at waves 2, 3 and 4 were 9.33±2.14, 9.34±2.0 and 9.98±1.8, respectively. Males had a higher observed self-esteem (9.70±1.92), on average, than females (9.39±2.10). On average, self-esteem was highest in participants with no mental disorders – about 9.9 compared to about 9.0 in participants with any anxiety disorder (see Table 1). Among the categories of anxiety disorders, participants with at least social phobia appeared to have the lowest observed mean self-esteem while participants with at least separation anxiety disorder had the highest followed by participants with at least OCD.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample Population.

| Population Characteristics | Mean ± SD | Outcome: Self-Esteem | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Age | 17.29 ± 4.42 | 9.55 ± 2.02 | |

| Age by Wave: | |||

| Wave 2 (n=756) | 13.76 ± 2.58 | 9.33 ± 2.14 | |

| Wave 3 (n=750) | 16.19 ± 2.76 | 9.34 ± 2.00 | |

| Wave 4 (n=751) | 22.11 ± 2.73 | 9.98 ± 1.84 | |

| Overall SES | 10.00 ± 1.00 | ||

|

| |||

| N (% of Total Sample) | |||

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 418 (50.90) | 9.70 ± 1.92 | |

| Female | 403 (49.10) | 9.39 ± 2.10 | |

| Race | |||

| White | 748 (91.11) | 9.54 ± 2.00 | |

| Black | 73 (8.89) | 9.57 ± 2.19 | |

| Comparison Group: | |||

| Healthy/no mental disorder (n=427) | 427 (52.01) | 9.87 ± 1.86 | |

| Any Anxiety Disorder (n=225)* | 225 (27.41) | 9.01 ± 2.04 | |

| Among Anxiety Disorders:† | |||

| Overanxious Disorder | 111 (13.52) | 8.88 ± 2.19 | |

| Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder | 43 (5.24) | 9.09 ± 2.03 | |

| Simple Phobia | 90 (10.96) | 8.89 ± 2.16 | |

| Social Phobia | 65 (7.92) | 8.63 ± 2.03 | |

| Separation Anxiety Disorder | 67 (8.16) | 9.30 ± 2.13 | |

Individuals with at least one anxiety disorder including those with any combination of anxiety disorders

Individuals have at least the specified anxiety disorder as compared with individuals without this anxiety disorder

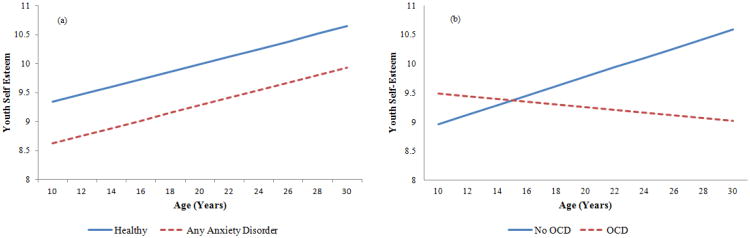

Basic Model and Impact of Any Anxiety Disorder

Without controlling for any factors, self-esteem increased over time by about 0.08 units each year. Subjects with any anxiety disorder (n=225), on average, have a self-esteem score of 0.714 (ES= −0.35, p<0.01) units lower than subjects with no mental health disorders (n=427) (see Table 2 and Figure 1(a)). No slope differences were found among these two groups (see Table 2). Average gender differences were found in the basic model with covariates (controlling for age, race and SES). However, there were no significant gender differences in the effect of any anxiety on self-esteem. No race or SES differences in the effect of anxiety on self-esteem were found.

Table 2. Impact of Adolescent Anxiety on Self-Esteem From the Ages of 13 to 22 Years †.

| Variable | Coefficient | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Model | |||

|

| |||

| Intercept | 9.52 | <0.01 | (9.41, 9.63) |

| Age | 0.08 | <0.01 | (0.06, 0.10) |

|

| |||

| Basic Model with Demographic Covariates | |||

|

| |||

| Intercept | 7.76 | <0.01 | (6.72, 8.81) |

| Age | 0.08 | <0.01 | (0.06, 0.10) |

| Gender | 0.27 | <0.01 | (0.07, 0.48) |

| Race | −0.32 | 0.11 | (−0.70, 0.07) |

| SES | 0.19 | <0.01 | (0.08, 0.30) |

|

| |||

| Model for Any Anxiety Disorder(s) (n=225)* | |||

|

| |||

| Intercept | 8.76 | <0.01 | (7.53, 9.98) |

| Age | 0.07 | <0.01 | (0.05, 0.09) |

| Anxiety | −0.71 | <0.01 | (−0.96, -0.47) |

|

| |||

| Model for Any Anxiety Disorder(s) with Interaction (n=225)* | |||

|

| |||

| Intercept | 8.78 | <0.01 | (7.56, 10.01) |

| Age | 0.05 | <0.01 | (0.03, 0.08) |

| Anxiety | −0.73 | <0.01 | (−0.98, -0.49) |

| Anxiety×Age | 0.04 | 0.10 | (−0.01, 0.08) |

Age was centered at 17 for all models; Anxiety disorder = 1, Healthy = 0

Models include gender (Male = 1, Female = 0), race (White = 1, Black = 0) and family SES as controls

Figure 1.

(a) Self-esteem change in youth by anxiety disorder status (any anxiety disorder versus healthy youth/no mental disorder) based on the model for any anxiety disorder; and (b) self-esteem change in youth by OCD status (at least OCD versus without OCD) based on the model for controlling for categories of anxiety disorders with OCD slope effect

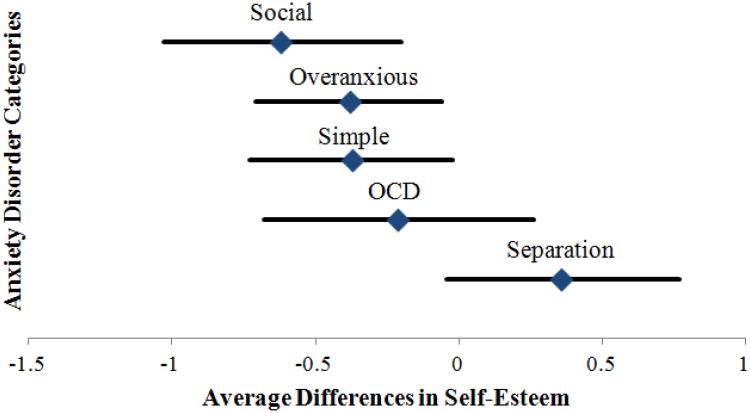

Relative Impact of Classifications of Anxiety Disorders

Our model indicates that social phobia, overanxious disorder, OCD, and simple phobia significantly predicted self-esteem among the study population (Table 3). Social phobia, overanxious and simple phobia classifications of anxiety disorders lowered self-esteem, on average, with social phobia having the most negative impact on average self-esteem relative to the other anxiety disorder types. Subjects with at least social phobia had an average self-esteem score about 0.62 units lower than subjects without social phobia (ES=−0.30, p<0.01; see Table 3 and Figure 2). Overanxious disorder had the second highest impact on average self-esteem, with a score of about 0.38 lower than the reference group (ES=−0.17, p<0.05; see Table 3 and Figure 2). Simple phobia had the least impact at 0.37 units lower (ES=−0.17, p<0.05; see Table 3 and Figure 2). No statistical evidence was found to suggest a difference in average self-esteem between participants with separation anxiety disorder and participants without separation anxiety (p=0.08; see Table 3 and Figure 2). Similar to the findings for subjects with any anxiety disorder, there was no significant gender or race differences found for the classifications of anxiety disorders. On the other hand, the model controlling for co-morbidity of the various classifications of anxiety disorders suggests that higher SES was significantly associated with higher self-esteem, on average.

Table 3. Relative Impact of Categories of Anxiety on Self-Esteem from the Ages of 13 To 22 Years (based on the Model Controlling for Categories of Anxiety Disorders with OCD Slope Effect).

| Variable | Coefficient | p-value | 95% CI | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social | −0.62 | <0.01 | (−1.03, −0.20) | −0.30 |

| Overanxious | −0.38 | <0.05 | (−0.71, −0.06) | −0.17 |

| Simple | −0.37 | <0.05 | (−0.73, −0.02) | −0.17 |

| OCD | −0.21 | 0.39 | (−0.68, 0.26) | |

| OCD × Age | −0.11 | <0.05 | (−0.19, −0.02) | −0.10 |

| Separation | 0.36 | 0.08 | (−0.04, 0.77) | 0.17 |

Figure 2. Mean effects with 95% confidence interval per anxiety disorder category based on the model controlling for categories of anxiety disorders with OCD slope effect.

Self-esteem in participants with OCD changed over time when compared to non-OCD controls, decreasing by about 0.1 units per year (p<0.05; see Table 3 and Figure 1(b)). However, other anxiety disorder types were not found to have a slope difference (see Table 3). The relative impact and ranking of the anxiety disorder types varies when assessing the average difference versus the slope difference. OCD had the only significant impact on slope difference, and social phobia (ES=−0.30, p<0.01; see Table 3) had the greatest impact on average self-esteem.

Discussion

The present research investigated self-esteem development from adolescence to young adulthood using longitudinal data based on three waves of data collected from the CIC study. Our findings are consistent with the research [2, 7, 27–28] indicating that self-esteem increases from adolescence to young adulthood. Those with any type of anxiety disorder have lower average self-esteem compared with the healthy group. Our results suggest that distinct anxiety disorders differ in their impact on self-esteem development. Social phobia, overanxious disorder, OCD, and simple phobia significantly predicted self-esteem, with social phobia having the highest impact on average self-esteem. Separation anxiety disorder was not found to have a significant impact on self-esteem development. The present study also showed that OCD adolescents exhibit a self-esteem decline compared to those without OCD. Average self-esteem was found to be lower in females in the basic model, but this effect was removed when examining the impact of any anxiety disorder on self-esteem. The present study advances the topic by analyzing longitudinal data from a large community-based sample whereas prior research is based predominantly on clinical or cross-sectional studies. To date, there are no known longitudinal-based studies using categories of adolescent anxiety disorders to prospectively predict self-esteem development through young adulthood.

Study Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. The main weakness of the study is that the data collected is relatively old as the data spans from 1983 to 1992. However, the CIC study was selected for our investigation as it is one of the few longitudinal studies providing a detailed assessment of psychopathology beginning in childhood from a large sample size. The generalizability of results to modern day adolescents and young adults is another limitation. The population is predominantly White further inhibiting the generalizability of results. However, the use of a largely homogenous sample strengthens the internal validity of the study by reducing potential bias. Data collection for the CIC study is ongoing. The present study provides a basis upon which future research may expand. Although we were able to capture anxiety diagnosis using a standard diagnostic interview, our measure of self-esteem was not as extensive due to constraints on the length of the interviews.

Study Implications

The findings from the present study offer evidence for implementing distinct interventions for raising self-esteem in adolescents with an anxiety diagnosis. Roberts [29] advocates that self-esteem should be incorporated into treatment of mental health disorders, and states that poor response to treatment of individuals with mental health disorders goes hand in hand with low self-esteem. Accordingly, raising self-esteem is a key ingredient in therapeutic attempts to elicit adaptive behavior in individuals with a mental health disorder [29]. By understanding the relationship between self-esteem and mental disorders clinicians may be prompted to use an intervention with a focus on raising self-esteem. These interventions may vary by class of mental health disorders and even further, based on the results of the present study, vary by classification of anxiety. For instance, clinicians may consider developing different interventions for adolescents with social phobia or OCD than for those with separation anxiety disorder targeting raising self-esteem.

Many longitudinal studies have found that self-esteem increases over time, particularly from early adolescence to young adulthood [2, 7, 27–28]. Our findings based on three waves of data collected over about one decade are consistent with these studies. Baldwin and Hoffman [30] found a curvilinear relationship for self-esteem development. A meta-analysis performed on 86 published articles found that self-esteem declines during adolescence and increases gradually throughout adulthood [3]. However, many of the studies from the meta-analysis were based on cross-sectional data and assess group mean difference rather than change over time.

Two studies that have linked anxiety disorder with decreased self-esteem were conducted in clinical settings [4, 14]. These studies found a relationship between anxiety and self-esteem, but did not examine the impact of anxiety disorders on self-esteem development through young adulthood. Both studies were conducted on adult participants. The sample analyzed in the present study consists of community individuals with a variety of anxiety and mental health disorders as well as individuals without the assessed disorders, making the results relevant to the general population. Subjects with any anxiety disorder were found to have a significantly lower self-esteem, on average, than healthy subjects. Wallis [4] reported that adult anxious clients suffered from poorer self-esteem. In fact, following an intervention to improve the state of anxiety in adult anxious clients, adult anxious clients became less anxious and showed increased self-esteem as a result [4]. Adolescence, as a transitory state, is subject to increased responsibility that may lead to additional stress thereby affecting self-esteem [30]. Adolescents who experience greater stress are typically depressed or anxious with evidence suggesting decreases in self-esteem for these adolescents [30]. The present study agrees with this conjecture. There are no known longitudinal-based studies using categories of adolescent anxiety disorders to prospectively predict self-esteem development through young adulthood.

Social phobia had the greatest impact on self-esteem development relative to the other anxiety disorders. Social acceptance by peers and parental figures play an important role in adolescent development and self-identity [24, 31]. Adolescents who experience positive relationships with peers or associate with groups perceived as having a “high-status” typically demonstrate higher levels of self-esteem and less social anxiety [31-32]. Our findings are consistent with this concept as well as the findings from Geist and Borceki [33], a cross-sectional study suggesting that the degree of social distress is indicative of an individual's perceived locus of control and self-esteem level.

Separation anxiety disorder tends to be more common in children while social phobia tends to affect adolescents [34]. Separation anxiety typically occurs at about 12 through 18 months of age and usually does not persist beyond childhood [34]. Hale et al. [35] showed that symptoms of separation anxiety disorder decreased for all adolescent participants over the course of a 5-year prospective community study. The same study showed that symptoms of social phobia remained fairly stable over time further supporting the idea that social phobia plays a significant role during adolescence [35]. It is not surprising then that no evidence was found in the present study to suggest that separation anxiety disorder predicts self-esteem development in adolescents while social phobia does so overwhelmingly. Future research may consider investigating how separation anxiety disorder may influence childhood self-esteem development through adolescence. For the purposes of the present study, separation anxiety disorder appears to have no significant impact on self-esteem development from adolescence through young adulthood. However, Lewinsohn et al [36] found that separation anxiety disorder in childhood is a risk factor for the development of mental disorders such as panic disorder and depression during young adulthood. Thus, the potential impact of this disorder should not be ignored.

The present study showed that OCD adolescents exhibit a self-esteem decline. Obsessive thoughts leading to significant functional impairment are characteristic of OCD individuals [37]. Individuals scoring high on an obsessionality scale have been shown to evaluate their self-worth based on moral standing, social skills and acceptance, and physical attraction [38]. OCD individuals amplify the importance of perceived negative characteristics of the self [39] leaving them vulnerable to decreases in self-esteem.

Gender differences in self-esteem have been a focus among previous studies [2, 6-7, 12, 40], but has not been assessed in the context of the effect of anxiety disorders on self-esteem development. Findings from such studies have yielded inconsistent results. For instance, in Orth et al. [7], minor differences in self-esteem were found between men and women during young adulthood. However, Erol and Orth [2] found that women and men did not differ in their self-esteem trajectories. In contrast, Block and Robins [12] showed that self-esteem in males tends to increase while decreasing in females through young adulthood. Their study suggests that self-esteem change among males is linked to the ability to control personal anxiety level. Social acceptance has a greater influence in females than in males as females tend to be in touch with how others may be judging them more than their male peers [24]. This may account for gender differences found in some studies. The present study found that females have lower average self-esteem when considering gender as a main effect. However, when examining the effect of any anxiety disorder and the effect of the co-morbidity model, our study found no gender differences.

In summary, the present research investigated self-esteem development from adolescence to young adulthood using longitudinal data from the CIC study. As mentioned previously, studies have been inconsistent in determining self-esteem trajectory. The present study advances the topic by analyzing longitudinal data from a large community-based sample whereas prior research is based predominantly on clinical or cross-sectional studies. Our results suggest that distinct anxiety disorders differ in their impact on self-esteem development. The implications of this research are practical in the efforts to make adolescence a smooth transition for youth. Whether used for clinical treatment or future research, the present study serves to supplement the self-esteem literature in adolescents; it also serves as the first study to use various categories of anxiety disorders to predict self-esteem trajectories from adolescence through young adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH-36971, MH-38914, MH-38916, and MH-49191.

Footnotes

Implications and contribution: The present study advances knowledge on self-esteem development from adolescence into adulthood, and is the first community-based longitudinal study to assess the relative impact of various types of anxiety disorders found in early adolescence on self-esteem development through young adulthood.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cohen P, Kasen S, Chen H, et al. Variations in Patterns of Developmental Transitions in the Emerging Adulthood Period. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:657–669. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.4.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erol R, Orth U. Self-Esteem Development From Age 14 to 30 Years: A Longitudinal Study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:607–619. doi: 10.1037/a0024299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robins R, Trzesniewski K. Self-Esteem Development Across the Lifespan. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:158–162. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallis D. Depression, Anxiety and Self-esteem: A Clinical Field Study. Behav Change. 2002;19:112–120. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarons G, Monn A, Leslie L, et al. Association Between Mental and Physical Health Problems in High-Risk Adolescents: A Longitudinal Study. J Adolsc Health. 2008;43:260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birndorf S, Ryan S, Auinger P, et al. High self-esteem among adolescents: Longitudinal trends, sex differences, and protective factors. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orth U, Robins R, Trzesniewski K. Self-Esteem Development from Young Adulthood to Old Age: A Cohort-Sequential Longitudinal Study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98:645–658. doi: 10.1037/a0018769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trzesniewski K, Moffit T, Poulton R, et al. Low Self-Esteem During Adolescence Predicts Poor Health, Criminal Behavior, and Limited Economic Prospects During Adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2006;42:381–390. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews G, Crino R, Hunt C, et al. The treatment of anxiety disorders: Clinician's guide and patient manuals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakley-Browne MA. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Int Rev Psychiatr. 1991;3:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication – Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Block J, Robins R. A Longitudinal Study of Consistency and Change in Self-Esteem from Early Adolescence to Early Adulthood. Child Dev. 1993;64:909–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1993.tb02951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg J, Solomon S, Pyszczynski R, et al. Why do people need self-esteem? Converging evidence that self-esteem serves an anxiety-buffering function. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63:913–922. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehntholt K, Salkovskis P, Rimes K. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorders, and self-esteem: an exploratory study. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:771–781. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchand A, Goupil G, Trudel G, et al. Fear and social self-esteem in individuals suffering from panic disorder with agoraphobia. Scand J of Behav Ther. 1995;23:163–170. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg M. The Association Between Self-Esteem and Anxiety. J Psychiat Res. 1962;1:135–152. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(62)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low Self-Esteem Prospectively Predicts Depression in Adolescence and Young Adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95:695–708. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.3.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee A, Hankin BL. Insecure Attachment, Dysfunctional Attitudes, and Low Self-Esteem Predicting Prospective Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety During Adolescence. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:219–231. doi: 10.1080/15374410802698396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogan LS, Smith J, Jenkins S. Ecological validity of indicator data as predictors of survey findings. J Soc Serv Res. 1978;1:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Costello EJ, Edelbrock CS, Duncan MK, et al. Testing of the NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in a Clinical Population: Final Report to the Center for Epidemiological Studies, NIMH. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen P, Cohen J. Life Values and Adolescent Mental Health. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc; Mahwah NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bird HR, Gould M, Staghezza B. Aggregating data from multiple informants in child psychiatry epidemiological research. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry. 1992;49:282–291. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berenson K, Crawford T, Cohen P. Implications of Identification with Parents and Parents' Acceptance for Adolescent and Young Adult Self-Esteem. Self Identity. 2005;4:289–301. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laird NM, Ware JH. Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 1982;38:963–974. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singer J. Using SAS PROC MIXED to Fit Multilevel Models, Hierarchical Models, and Individual Growth Models. J Educ Behav Stat. 1998;4:323–355. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gentile B, Campbell W, Twenge J. Birth Cohort Differences in Self-Esteem, 1988-2008: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis. Rev Gen Psychol. 2010;14:261–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCarthy J, Hoge D. Analysis of Age Effects in Longitudinal Studies of Adolescent Self-Esteem. Dev Psychol. 1982;18:372–379. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts J. Self-Esteem from a Clinical Perspective. In: Kernis M, editor. Self-Esteem Issues and Answers: A Sourcebook of Current Perspectives. 1st. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baldwin S, Hoffman J. The Dynamics of Self-Esteem: A Growth-Curve Analysis. J Youth Adolescence. 2002;31:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- 31.La Greca A, Harrison H. Adolescent Peer Relations, Friendships, and Romantic Relationships: Do They Predict Social Anxiety and Depression? J Clin Child Adolesc. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman M, Copeland L, Shope J, et al. A Longitudinal Study of Self-Esteem: Implications for Adolescent Development. J Youth Adolescence. 1997;26:117–141. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geist C, Borecki S. Social Avoidance and Distress as a Predictor of Perceived Locus of Control and Level of Self-Esteem. J Clin Psychol. 2006;38:611–613. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198207)38:3<611::aid-jclp2270380325>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine D. Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents: Developmental Issues and Implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;32:483–524. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hale W, III, Raaijmakers Q, Muris P, et al. Developmental Trajectories of Adolescent Anxiety Disorder Symptoms: A 5-Year Prospective Community Study. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2008;47:556–564. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewinsohn P, Holm-Denoma J, Small J, et al. Separation Anxiety Disorder in Childhood as a Risk Factor for Future Mental Illness. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2008;47:548–555. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816765e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cameron CL. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents. J Psychiatr Ment Hlt. 2007;14:696–704. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doron G, Kyrios M. Obsessive compulsive disorder: A review of possible specific internal representations within a broader cognitive theory. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:415–432. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhar S, Kyrios M. An investigation of self-ambivalence in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1845–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robins R, Trzesniewski K, Tracy J, et al. Global Self-Esteem Across the Life Span. Psychol Aging. 2002;17:423–434. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.17.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]