To the Editor:

Even though 83 million procedures are performed in medical offices in the US each year,1 patients are only rarely asked about problems they experience after these procedures. This oversight may highlight a key opportunity to improve health care because patient self-reporting is known to offer both clinical and scientific value.2,3 To inform decision-making for office-based procedures we studied patients treated for Non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the most common malignancy,4 which is most often treated with an office procedure.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study of 886 consecutive patients with basal or squamous cell skin cancer who completed an in-person questionnaire before treatment. Office treatments for NMSC included Mohs surgery, excision, and destruction with cryotherapy or electrodessication and curettage. At 3, 12 and 18 months and annually up to 5 years after treatment, patients were asked: “In your opinion, have there been any complications of your treatment during or after the treatment itself?” Those who reported a complication were asked to describe it and to rate its severity using a Likert-like scale ranging from minimally to extremely serious. Descriptions were classified by 2 independent clinicians into 2 categories: 1) medical complications: bleeding, infection, pain, swelling, poor wound healing, numbness or itching, problem with motor function, allergic reaction to bandages or antibiotics, and 2) non-medical problems: problems with scar or appearance, need for additional treatment, administrative problems or other. Overall, 83% of patients responded to at least one questionnaire. We calculated complication rates as the number of patients out of our baseline cohort who reported a complication at any time point, making the conservative assumption that all non-responders including patients lost to follow up did not experience complications. Two clinicians reviewed all medical charts for complications up to 5 years after treatment.

Results

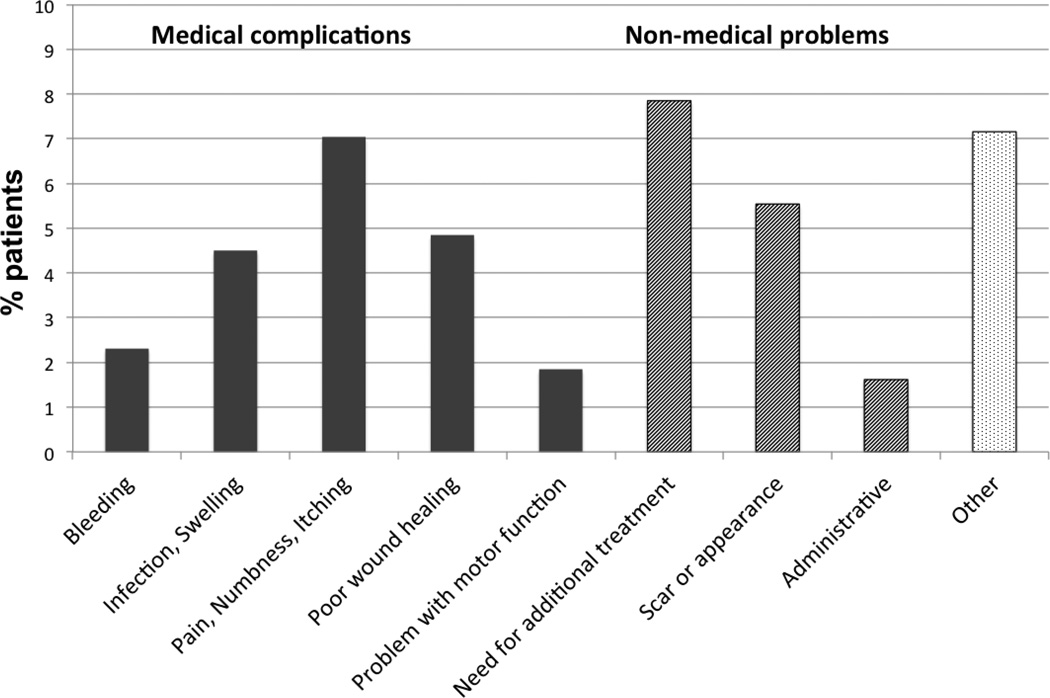

Cohort patients were typical of skin cancer patients nationwide (Table 1). More than a quarter of patients (27% or 236/866) reported a problem after treatment and 14% overall described medical complications (Figure 1). For example, 7% experienced pain, numbness, or itching, 5% problems with wound healing, 5% infection or swelling, 2% bleeding, and 2% problems with motor nerve function. Overall, 10% of all patients described problems that were ‘moderate, very, or extremely serious’. Complications were noted by the clinician in 2.5% of patients' medical charts.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 866 patients with Non-melanoma skin cancer who responded to baseline questionnaire and followed for 5 years after treatment

| All Cohort patients Mean or % |

|

|---|---|

| PATIENT | N=866 |

| Age, years, mean (IQR) | 66 (55–77) |

| Gender – male | 75% |

| History of prior NMSC | 57% |

| Number of NMSC at baseline, mean (range) | 1.3 (1–8) |

| Annual income <30,000 | 51% |

| Education ≤ high school | 38% |

| TUMOR | |

| Tumor diameter, mm, mean (IQR) | 8 (5–12) |

| Tumor on central face | 41% |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 75% |

| Superficial pathology | 29% |

| TREATMENT | |

| Mohs | 40% (N=343) |

| Excision | 37% (N=324) |

| Destruction | 22% (N=191) |

| Other | 1% (N=8) |

| PATIENT-REPORTED PROBLEMS | |

| Overall | 27% (N=236) |

| Medical complications | 14% (N=123) |

| Non-medical problems | 13% (N=113) |

| Severity | |

| Mild | 17% (N=146) |

| Moderate, very or extremely | 10% (N=90) |

| PHYSICIAN-RECORDED COMPLICATIONS | 2.5% (N=22) |

Figure 1.

Types of complications described by patients treated for NMSC.

* Administrative category includes problems with insurance, travel or telephone contact with clinic.

* Other category includes patient responses reported by <1% sample for example: allergic reactions, anxiety, problems relating to post-operative period (e.g., “not able to wear glasses because ear flap attached to scalp”, “have to wear a dressing over my mouth, need to drink with a straw”, “cant swim anymore and I was a competitive swimmer”)

Comment

Our findings suggest that over a quarter of patients perceived complications after a common office procedure, treatment for skin cancer, and that 10% of patients regarded their problems as at least moderately serious. We also found a significant discrepancy between patients’ perceptions and clinicians’ reports of complications after office procedures. In fact, patients’ problems were only rarely documented in the medical record. The reasons for our findings are unclear. Clinicians may be unaware of patients’ experiences, or they may decide these problems do not warrant documentation as complications in the chart. Patients may overstate problems (e.g., scars) that are, to clinicians, largely unavoidable. Overall, this discrepancy suggests that patients may have a broader view of what it means to have complications after procedures, including non-medical problems (e.g., problems with insurance or follow-up appointments) and expected consequences of a procedure (e.g., scars or need for additional treatment).

Medical care is probably improved if clinicians understand patients’ experiences.2,5 Such understanding may identify adverse outcomes that can be prevented, or may highlight situations in which educating and preparing patients may more closely align their expectations with likely outcomes. Knowledge about patients’ experiences after procedures can also improve decision-making by future patients by providing clear data about prognosis. Because office procedures are among the most common medical interventions, efforts to improve their outcomes are important. We propose that these efforts can be strengthened by asking patients directly about their experiences.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank to thank Amy J. Markowitz for editorial help, Sarah Stuart for data management and John Boscardin and Rupa Parvataneni for their help with statistical analysis. EL and MMC had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis

Footnotes

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.National Health Statistics Report. 2010 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr027.pdf.

- 2.Basch E. The missing voice of patients in drug-safety reporting. N Engl J Med. 2010 Mar 11;:362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basch E, Jia X, Heller G, et al. Adverse symptom reporting by patients versus clinicians: relationships with clinical outcomes. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2009;101(23):1624–1632. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed Jan 10, 2013];Skin Cancer Statistics. 2012 Dec 12; http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/

- 5.Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) http://www.pcori.org/about/mission-and-vision/