Abstract

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an angiogenic factor implicated in asthma severity. The objective of the present study was to determine whether VEGF single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are associated with asthma, lung function and airway responsiveness.

The present authors analysed 10 SNPs in 458 white families in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP). Tests of association with asthma, lung function and airway responsiveness were performed using PBAT software (Golden Helix, Inc. Bozeman, MT, USA; available at www.goldenhelix.com). Family and population-based, revpeated measures analysis of airflow obstruction were conducted. Replication studies were performed in 412 asthmatic children and their parents from Costa Rica.

Associations with asthma, lung function and airway responsiveness were observed in both cohorts. SNP rs833058 was associated with asthma in both cohorts. This SNP was also associated with increased airway responsiveness in both populations. An association of rs4711750 and its haplotype with forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio in both cohorts was observed. Longitudinal analysis in CAMP confirmed an association of rs4711750 with FEV1/FVC decline over ~4.5 yrs of observation.

VEGF polymorphisms are associated with childhood asthma, lung function and airway responsiveness in two populations, suggesting that VEGF polymorphisms influence asthma susceptibility, airflow obstruction and airways responsiveness.

Keywords: Airflow obstruction, asthma, single nucleotide polymorphisms, vascular endothelial growth factor

Exaggerated T-helper cell (Th) type 2-mediated inflammation, producing airflow obstruction, is one of the pathological cornerstones of asthma. Although this airflow obstruction is typically reversible with bronchodilator use, progressive, irreversible airflow obstruction can develop in some patients with persistent asthma, resulting in long-term disability [1]. This progressive obstruction is often associated with the characteristic histopathological changes of airway remodelling, which include subepithelial fibrosis, neovascularisation and increased smooth muscle deposition, all leading to a decrease in the calibre of the small airways [2]. Angiogenesis has been found to be an important histological feature of the airway wall in asthma. Bronchial biopsies from asthmatic patients demonstrate increased vascularity, with notable increases in both the subepithelial vascular surface area and overall vessel size [2].

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is the critical angiogenic factor implicated in neovascularisation in response to tissue injury and repair. Several lines of evidence suggest that VEGF contributes to the development of asthma, airway responsiveness and airway remodelling. Animal models have demonstrated the importance of VEGF in antigen-induced Th2-mediated airway inflammation in asthma [3]. Transgenic mouse models have also demonstrated that overexpression of VEGF leads to increased vascularity in the airway epithelium, airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness, all of which are largely attenuated by VEGF antagonism [4]. Pathological findings are similar in human subjects with asthma. Simcock et al. [5] recently showed that levels of pro-angiogenic factors, including VEGF, are higher in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of patients with mild asthma than in nonatopic healthy controls [5]. In humans, VEGF expression is significantly higher in the BAL fluid of asthmatic subjects than in that of healthy controls [6]. Among asthmatics, VEGF expression in BAL fluid is inversely correlated with lung function [2]. Another recent study in asthmatic human subjects confirms that increased VEGF and VEGF receptor (VEGFR) expression within airway epithelial cells was correlated with airway remodelling in histological samples, airflow obstruction on spirometry, and increased airways responsiveness to methacholine [7]. In the present study, treatment with budesonide/fomoterol for 6 months decreased VEGF and VEGFR expression and decreased airway remodelling noted on histological specimens [7]. Together, these data implicate VEGF as a plausible molecular determinant of asthma susceptibility, airway remodelling, airways responsiveness and progressive lung function decline.

Given these observations, the present authors hypothesised that VEGF gene sequence variation influences asthma susceptibility, progressive airflow obstruction and airways responsiveness in children with asthma. The human VEGF gene (located on chromosome 6p21) harbours at least 140 known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), several of which have been associated with clinical phenotypes [8–10]. However, no studies of VEGF associations with asthma, lung function or airways responsiveness have been reported to date. To determine whether VEGF variants contribute to asthma susceptibility, airflow obstruction and airways responsiveness, the present authors performed family based genetic association studies in two childhood asthma cohorts.

METHODS

Study population

The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) was a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to investigate the long-term effects of inhaled corticosteroids and inhaled nedocromil. Of the 1,041 children randomised in the clinical trial, 968 children and 1,518 of their parents contributed DNA samples as part of the genetic ancillary study of CAMP. DNA was sufficient for all family members for 470 nuclear families of self-reported, non-Hispanic, white ancestry who were studied previously [11]. Of these families, 32 had more than one asthmatic offspring, resulting in a total of 503 asthmatic children available for analysis.

Children enrolled in CAMP had mild-to-moderate persistent asthma based on demonstration of airway hyperresponsiveness to methacholine with a PC20 (provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)) ≤12.5 mg·mL−1, and at least two of the following: asthma symptoms at least twice per week, the use of inhaled bronchodilator at least twice weekly, or the use of daily asthma medication for >6 months in the year prior to screening [12]. Follow-up clinic visits with spirometry occurred at 2 and 4 months, and every 4 months thereafter. Spirometry performance was required to meet American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria for acceptability and reproducibility. At least three spirometric manoeuvres were performed, with at least two reproducible manoeuvres required for each test. Post-bronchodilator spirometric values were obtained >15 min after the administration of two puffs of albuterol (90 μg·puff−1). Complete trial design, methodology and primary outcomes analysis of the CAMP study have been previously published [13].

Replication population

Replication studies were performed in 412 parent–child trios recruited as part of the Genetic Epidemiology of Asthma in Costa Rica cohort between February 2001, and March 2005. Details on subject recruitment and study protocols have been published elsewhere [14]. In brief, children aged 6–14 yrs were included in the study if they had asthma (as indicated by a physician’s diagnosis of asthma, at least two respiratory symptoms or asthma attacks in the previous year) and a high probability of having at leat six great-grandparents born in the Central Valley of Costa Rica (as determined by the present study’s genealogist on the basis of the paternal and maternal last names of each of the child’s parents). This requirement increased the likelihood that children would be descendants of the founder population of the Central Valley [15]. All children completed a questionnaire, pulmonary function testing (meeting ATS criteria for acceptability and reproducibility), methacholine challenge testing, and measurements of serum total immunoglobulin E and peripheral blood eosinophils.

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA, USA), the Hospital Nacional de Niños (San José, Costa Rica), and each of the CAMP-participating institutions. Informed consent was obtained from parents of participating children, and the child’s assent was obtained prior to study enrolment.

Genotyping

SNPs were selected from the HapMap [16] and dbSNP [17] databases to tag all common VEGF haplotype blocks and to achieve a physical density of ~5 kb/SNP. SNP genotyping was performed using the Illumina Golden Gate platform (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA, USA). Duplicate genotyping was performed on ~5% of the sample to assess the quality of genotyping. The pedigree data were assessed for evidence of parent–offspring genotype incompatibility using PedCheck [18]. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was tested in parents at each locus using an exact method [19]. Genotype data quality was assessed by genotype completion rates, discordance in the duplicate genotyping and evidence of Mendelian inconsistencies in the data.

Statistical analysis

Family based association tests (FBAT) were conducted, as implemented in the GoldenHelix package (Golden Helix, Inc., Bozeman, MT, USA; available at www.goldenhelix.com). The asthma association analyses were performed without covariate adjustment [20]. The analyses of lung function phenotypes (post-bronchodilator (FEV1) and the ratio of FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) were conducted with covariate (age, sex and height) adjustment. The analysis of airways responsiveness was adjusted for age, sex, height and use of inhaled steroids. Standard phenotypic residuals were obtained by regressing the phenotype on nongenetic covariates that are thought to be strong predictors of the phenotype. The goal is to remove the variability in the phenotype that is due to nongenetic factors (listed above for each phenotype tested). Standard phenotypic residuals were then used as the outcome for the quantitative trait analysis. Additive and dominant genetic models were considered. To account for multiple comparisons, results were deemed statistically significant (study-wide alpha <0.05) when similar associations (i.e. same allele, same phenotype, same direction of genetic effect given the same genetic model) were observed in both the CAMP and Costa Rican populations with a Fisher’s combined p-value of <0.0008. This threshold accounts for testing of eight effectively independent markers (determined using the Nyholt SNPSpD method; see online supplementary data S1 [21, 22], four non-independent phenotypes, under two genetic models).

Haplotype block structure was defined with the Gabriel method [23] using Haploview (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA; available at www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview), and haplotype-based tests of association were performed using PBAT (Golden Helix, Inc.; available at www.goldenhelix.com). Global tests of haplotype association were performed using the multiallelic haplotype test with a cut-off frequency of 0.01. Individual haplotype block associations were then assessed using haplotype-specific tests of association.

Given the availability of longitudinal data on the children in CAMP, the present authors were able to assess the effect of SNP rs4711750 on progressive airflow obstruction. A longitudinal analysis was performed in CAMP for FEV1/FVC using mixed models implemented in the Proc MIXED procedure in SAS (version 9.1; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The longitudinal analysis was adjusted for age, sex, treatment group and height. Corroborative family based tests of association with repeated spirometric measures used a principal component FBAT (FBAT-PC) [24].

The CAMP study design, as a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial, enabled testing of whether treatment with inhaled corticosteroids modifies the effect of VEGF polymorphisms on longitudinal lung function. The present authors thus performed gene-by-treatment group tests for interaction using the FBAT of interaction (FBAT-I) implemented in PBAT [25]. The Costa Rican population was not studied in the context of randomised treatment assignments, precluding similar analysis in this cohort.

RESULTS

Phenotypic and genetic comparability of the CAMP and Costa Rican cohorts

The baseline characteristics of the index cases in both the CAMP and Costa Rican trios genotyped for this study are presented in table 1. Despite the differences in geographical and ancestral origin, and methods of sample ascertainment, the baseline characteristics of the CAMP and Costa Rican pro-bands were very similar. There were more males in both cohorts, in keeping with the known increased prevalence of childhood asthma among males.

TABLE 1.

Baseline phenotypic characteristics of index cases in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) and the Costa Rican population

| CAMP# | Costa Rican | |

|---|---|---|

| Subjects n | 493 | 412 |

| Variable | ||

| Mean age yrs | 8.7 (7.0–10.5) | 9.2 (7.8–10.4) |

| Females | 187 (38) | 152 (37) |

| Baseline post-bronchodilator FEV1 L¶ | 1.81±0.5 | 1.84±0.5 |

| Baseline post-bronchodilator FVC L | 2.13±0.6 | 2.15±0.6 |

| Baseline post-bronchodilator FEV1 /FVC | 85.62±6.3 | 85.63±6.4 |

| IgE level IU·L−1 | 405.0 (171.0–1061.0) | 422.0 (118.0–975.0) |

| PC20 mg·mL−1 | 1.1 (0.5–2.8) | 1.2 (0.7–1.4) |

| Eosinophil count cells·mm−3 | 411.0 (229.0–700.0) | 530.0 (290.0–805.0) |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range), n (%) and mean±SD, unless otherwise indicated. FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity; IgE: immunoglobulin E; PC20: provocative concentration of methacholine causing a 20% fall in FEV1.

lung function phenotypes presented in the table are unadjusted values;

non-Hispanic white.

Of the 470 white families in the CAMP study, 13 were removed from this analysis because of Mendelian inconsistencies, and 10 probands had inadequate genotyping. Of the 426 trios participating in the Genetic Epidemiology of Asthma in Costa Rica study, 14 were excluded because of Mendelian inconsistencies (n=9) or inadequate genotypic data for VEGF (n=5). Seventeen SNPs in VEGF were thus genotyped in 458 non-Hispanic white families (493 probands) in CAMP and 412 Costa Rican trios. The quality of the genotypic data was high for both study populations included in the analysis, with an average completion rate of 99% and no discrepancies between the initial genotyping and the 5% of samples that underwent repeat genotyping. Parental genotypes in both populations were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium at all loci.

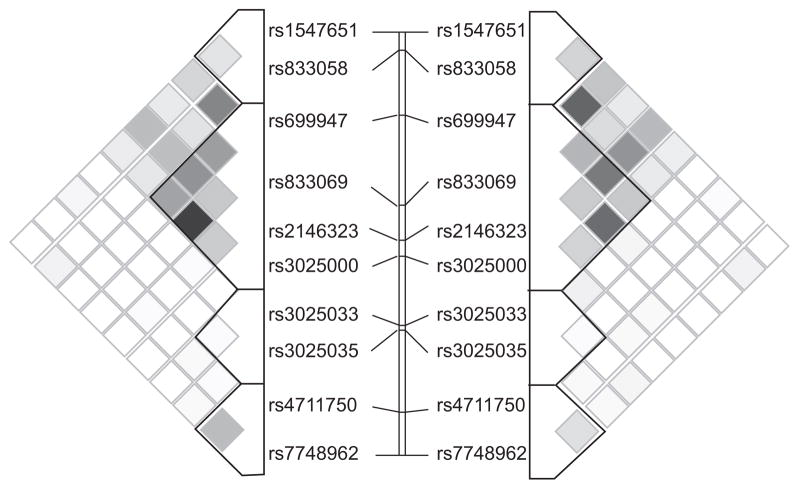

Figure 1 presents the patterns of linkage disequilibrium (LD) and haplotype block structure in both asthma cohorts. Despite differing ancestral histories, regional LD surrounding the VEGF gene was similar, with the 10 SNPs used in the present analysis organising into four discrete haplotype blocks in both populations. Block structure was nearly identical between cohorts, in that block boundaries and the haplotypes within each block were similar. However, notable differences in the distribution of haplotype frequencies were found (table 2). For example, block 4 was defined by three adjacent SNPs in both cohorts and harbours the same four common haplotypes, yet the most common haplotype in CAMP subjects (TCG, frequency 0.517) was much less common in the Costa Rican cohort (0.122). Similar, but less extreme, differences in haplotype distributions were noted in other blocks, particularly block 2. Thus, while LD and haplotype structure are virtually identical between these cohorts, haplotype frequencies vary somewhat.

FIGURE 1.

Linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) based on R2 in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP; left) and the Costa Rican (right) subjects. The 10 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) tested for association are represented from 5′ (top) to 3′ (bottom). Haplotype blocks are defined using the method outlined by Gabriel et al. [23]. The dark blocks indicate SNPs with high LD, while regions of low LD are shown in white.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of haplotype block structure across the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) locus in Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) and Costa Rican subjects

| Haplotype frequencies

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMP | Costa Rican | |||||||

| Block 1 | ||||||||

| SNP | rs1547651 | rs833058 | ||||||

| Hap 1 | A | C | 0.452 | 0.315 | ||||

| Hap 2 | A | T | 0.389 | 0.536 | ||||

| Hap 3 | T | C | 0.157 | 0.146 | ||||

| θ# | 0.64 | 0.79 | ||||||

| Block 2 | ||||||||

| SNP | rs699947 | rs1005230 | rs833067 | rs833069 | rs2146323 | rs3025000 | ||

| Hap 1 | A | T | C | T | A | C | 0.327 | 0.279 |

| Hap 2 | C | C | T | C | C | T | 0.318 | 0.279 |

| Hap 3 | C | C | T | T | C | C | 0.185 | 0.246 |

| Hap 4 | A | T | C | T | C | C | 0.150 | 0.074 |

| Hap 5 | C | C | T | C | C | C | 0.013 | 0.620 |

| θ | 0.24 | 0.25 | ||||||

| Block 3 | ||||||||

| SNP | rs3025033 | rs3025035 | ||||||

| Hap 1 | G | C | 0.147 | 0.206 | ||||

| Hap 2 | A | C | 0.790 | 0.695 | ||||

| Hap 3 | A | T | 0.063 | 0.099 | ||||

| θ | 0.38 | 0.34 | ||||||

| Block 4 | ||||||||

| SNP | rs4711750 | rs6900017 | rs7748962 | |||||

| Hap 1 | T | C | G | 0.517 | 0.122 | |||

| Hap 2 | A | C | A | 0.226 | 0.488 | |||

| Hap 3 | T | C | A | 0.185 | 0.323 | |||

| Hap 4 | T | T | A | 0.069 | 0.068 | |||

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) organise into four discrete haplotype (Hap) blocks with similar boundaries in both populations. Haplotypes are similar in the two populations within each block, but the differences in haplotype frequencies between the two populations are shown herein.

θ represents the recombination frequency between adjacent haplotype blocks.

Association of VEGF with asthma and lung function phenotypes in CAMP and Costa Rican subjects

Next, the VEGF genetic variation was tested for association with asthma, airflow obstruction and airways responsiveness. To reduce the number of statistical comparisons, the present authors limited association testing to 10 of the 17 SNPs genotyped by excluding seven SNPs with minor allele frequency <10% (due to limited statistical power).

The FBAT association results under dominant genetic models between the 10 VEGF polymorphisms and asthma affection status in both populations are shown in table 3. There was evidence of association of rs833058 with asthma in CAMP (p=0.004). Notably, this association was replicated in the Costa Rican trios (p=0.01). In both populations, the T allele was overtransmitted to individuals with asthma (Fisher’s combined p=0.0004), which was statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons [26, 27]. Another VEGF variant demonstrated suggestive evidence of association with asthma in CAMP (rs7748962, p=0.02) but this association was not replicated in the Costa Rican cohort.

TABLE 3.

Suggestive and replicated associations in Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) and Costa Rican subjects under dominant genetic models#

| Phenotype | dbSNP rs | CAMP

|

Costa Rican

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allele | Allele frequency | Informative families n | Z score | p-value | Allele | Allele frequency families | Informative families n | Z score | p-value | ||

| Asthma | rs833058 | T | 0.40 | 178 | 2.72 | 0.004 | T | 0.53 | 183 | 2.36 | 0.01** |

| rs7748962 | G | 0.23 | 254 | −2.36 | 0.01 | G | 0.12 | 149 | >0.05 | ||

| FEV1 | rs4711750 | A | 0.52 | 227 | 2.36 | 0.01 | A | 0.49 | 247 | >0.05 | |

| rs2146323 | A | 0.33 | 228 | >0.05 | A | 0.32 | 233 | 2.36 | 0.01 | ||

| FEV1/FVC | rs4711750 | A | 0.53 | 225 | 2.36 | 0.01 | A | 0.49 | 247 | −2.36 | 0.01 |

| Airway responsiveness | rs833058 | T | 0.40 | 241 | −2.32 | 0.01 | T | 0.53 | 180 | −2.12 | 0.03 |

SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism; FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC: forced vital capacity.

Lung function phenotypes are post-bronchodilator values.

Combined p-value 0.001, which is significant after study-wide correction for multiple comparisons.

Given the role of VEGF in mouse models of airway remodelling, it was next examined whether VEGF polymorphisms affect FEV1 in childhood asthma. Suggestive associations in CAMP included one SNP with FEV1 (rs4711750, p=0.01) but this association did not replicate in the Costa Rican trios. In the Costa Rican trios, the present authors also found suggestive evidence of association of SNP rs2146323 with post-bronchodilator FEV1 (p=0.02).

As airway remodelling has been associated with progressive airflow obstruction, the present authors next sought to determine whether VEGF variation influenced airflow obstruction, as measured by FEV1/FVC at the time of randomisation in the clinical trial. It is noteworthy that SNP rs4711750, located in the 3′-untranslated region of VEGF, was associated with FEV1/FVC (p=0.01) in CAMP, with the major A allele being overtransmitted to individuals with higher FEV1/FVC ratios. The association of SNP rs4711750 with FEV1/FVC in CAMP was also found in the Costa Rican cohort (p=0.02), albeit in the opposite direction (the minor A allele was undertransmitted to individuals with higher FEV1/FVC).

VEGF expression has been associated with airway responsiveness in the general population [28]. Therefore, the present authors examined whether VEGF polymorphisms affect airway responsiveness in childhood asthma. The asthma-associated SNP rs8833058 was also associated with increased airway responsiveness in both populations, with carriers of the T allele demonstrating increased airway responsiveness in both CAMP (p=0.01) and Costa Rican subjects (p=0.03, Fisher’s combined p=0.003; table 3). No additional SNP associations with airway responsiveness were observed.

Haplotype block associations with asthma and lung function phenotypes in CAMP and Costa Rican subjects

Based on the replicated findings of the single SNP analysis demonstrating an association with asthma, FEV1/FVC and airway responsiveness in both populations, the haplotype blocks containing these SNPs were subsequently tested for association with these phenotypes. Using the block structure established in Haploview, block 1 was tested for association with asthma affection status and airway responsiveness in both populations. The association with asthma was confirmed, with the AT haplotype being overtransmitted in both CAMP and Costa Rican subjects (p=0.02 and p=0.005, respectively, Fisher’s combined p=0.001). The AT haplotype in block 1 was also associated with increased airways responsiveness, albeit with weaker affect (in CAMP, p=0.03, and in Costa Rican subjects, p=0.03 and Fisher’s combined p=0.007). Furthermore, block 4, which is the terminal 3-SNP haplotype block containing rs4711750, was tested for association with FEV1/FVC. The ACA haplotype was associated with FEV1/FVC in both populations. The ACA haplotype was over-transmitted to individuals with higher FEV1/FVC values in CAMP and undertransmitted in the Costa Rican cohort (p=0.01 and 0.003, respectively).

Longitudinal analysis of airflow obstruction in CAMP

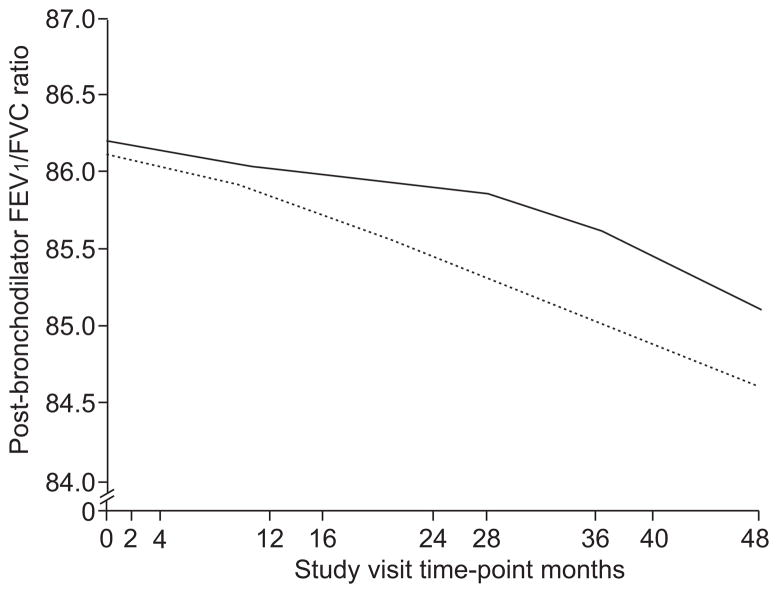

To assess the effect of rs4711750 on airflow obstruction over time, a population-based longitudinal analysis of post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC was performed over ~4.5 yrs of observation during the CAMP clinical trial. In order to exclude the potential effects of population stratification, confirmatory family based association testing using repeated measures of FEV1/FVC was performed using FBAT-PC. A significant relationship between rs4711750 genotype and FEV1/FVC was noted (p=0.03 with both analyses). As illustrated in figure 2, TT homozygotes developed more severe airflow obstruction over time as compared with AT or AA subjects. It is of interest that inhaled corticosteroids did not alter the development of progressive airflow obstruction over the time course of the clinical trial (p=0.11). Similar longitudinal data are not available in the Costa Rican cohort, precluding assessment of replication of this finding.

FIGURE 2.

Longitudinal forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio by genotype for single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs4711750. The effect of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) SNP rs4711750 on rate of lung function decline in the Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP) cohort over 4 yrs of observation, as measured by post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC. ——: CAMP subjects that are homozygous or heterozygous for major allele; -----: minor allele homozygotes.

Modification of the effect of VEGF SNPs on longitudinal lung function by treatment with inhaled corticosteroids in CAMP

Given previous evidence for the modification of the effect of VEGF on airway remodelling by treatment with inhaled corticosteroids for 6 months [7], SNP-by-treatment group assignment interactions were tested using FBAT-I [25]. These analyses revealed evidence for interaction between SNP rs2146323 and the treatment group on post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC (p-value for interaction 0.02): individuals on inhaled corticosteroids carrying at least one copy of the A allele had higher mean FEV1/FVC after 4 yrs of treatment with inhaled corticosteroids compared with subjects not treated with inhaled corticosteroids (85.1±5.6 versus 82.5±7.3). In contrast, subjects who did not carry the A allele demonstrated similar FEV1/FVC ratios regardless of treatment assignment (83.3±7.5 versus 84.2±6.7). There was no additional evidence for SNP-treatment interactions for the other VEGF SNPs.

DISCUSSION

A substantial proportion of children with persistent asthma (including those with mild disease) have reduced lung function as compared with nonasthmatic, healthy, age-matched controls, and fail to attain their maximal predicted lung growth [29]. Although the pathological changes characteristic of airway remodelling are often attributed to persistent allergic inflammation, sustained treatment of childhood asthma with inhaled corticosteroids at conventional doses does not appear to influence long-term lung function [12]. Thus, identifying the molecular determinants underlying the development of asthma and airway remodelling is of great importance, as understanding novel pathways that contribute to airway dysfunction may ultimately have profound therapeutic implications.

In this family based association study, it was found that a VEGF polymorphism (rs833058) was associated with asthma in two independently ascertained and ethnically distinct populations. This replicated association is significant after study-wide correction for multiple comparisons (see online supplementary material S1 for details). Of note, this SNP was also associated with increased airway responsiveness in both childhood asthma populations. The present authors have demonstrated that VEGF variants also affect airflow obstruction: rs4711750 was associated with FEV1/FVC in both populations and was also associated with progressive airflow obstruction over >4 yrs of follow-up in the CAMP study, suggesting that this variant (or others in linkage disequilibrium with it) may contribute to airway remodelling. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that 4 yrs of treatment with inhaled corticosteroids in the CAMP clinical trial modified the effect of SNP rs2146323 on FEV1/FVC after 4 yrs of observation.

Substantial evidence exists that demonstrates a role for VEGF in the development of airways responsiveness. Recently, Wang et al. [7] demonstrated the correlation of airway responsiveness (as measured by methacholine response) with bronchial epithelial cell VEGF and VEGFR mRNA expression in asthmatics. Genetic associations of VEGFR polymorphisms with airway responsiveness in the general population have been reported [28]. To the best of the present authors’ knowledge, the results presented here are the first to suggest association of a VEGF polymorphism with airway responsiveness in asthmatics.

Animal models of lung development have demonstrated the importance of the VEGF pathway in lung morphogenesis, with specific contribution to airway development in utero [30]. Substantial evidence from murine models of development suggests that epithelial expression of VEGF during early lung development regulates epithelial branching morphogenesis. The present study demonstrates associations of VEGF polymorphisms with lung function and airway responsiveness in two asthmatic populations, which may be related to the implications of VEGF in the context of airway development.

Like other intermediate asthma phenotypes, airway remodelling is likely to be a complex process, resulting from the interplay of genetic and environmental factors. An important environmental factor is cigarette smoke exposure (both active and passive), but longitudinal studies of lung function in adult asthmatics have shown that the accelerated decline often observed in asthmatics cannot be explained by smoking alone [31]. The evidence supporting a genetic contribution to this process is considerable. In addition to numerous studies demonstrating heritability of lung function in otherwise healthy populations, heritability estimates of lung function in asthmatic populations also support an important genetic contribution. For example, the heritability of post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC was estimated as 15.4±6.6% (p=0.001) in Costa Ricans, and subsequent genome-wide linkage analysis of pulmonary function in extended pedigrees from this population identified modest linkage of post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC on chromosome 6p in nonsmokers [32]. Linkage to this region, which includes the VEGF locus, has also been detected in a second asthma population [33]. It is conceivable that genetic variation at the VEGF locus contributes to these linkage results.

Bronchial biopsy specimens in patients with asthma demonstrate increased basement membrane thickening and increased vascularity when compared with healthy controls [34]. Several studies suggest that these pathological changes diminish after treatment with inhaled corticosteroids [7, 34]. Based on these observations, the present authors tested for interaction of inhaled corticosteroids on lung function after 4 yrs of treatment with inhaled corticosteroids. It has been shown herein that treatment with inhaled corticosteroids results in higher lung function at 4 yrs in patients with at least one copy of the A allele for SNP rs2146323, which is supported by the previous research. However, the present authors caution that this pharmacogenetic analysis was performed post hoc, and that the results were not amenable to replication in the Costa Rican cohort. Therefore, it is unclear whether these latter findings can be generalised to other populations.

Unlike the association of rs833058 with asthma, for which similar genetic effects were noted in both cohorts, the associations of rs4711750 with FEV1/FVC are in opposing directions in the CAMP and Costa Rican cohorts. There have been several other “flip-flop” associations documented in the literature [35–38]. Though possibly representing two false-positive associations, such flip-flops are occasionally noted when there are subtle differences in genetic architecture, suggesting that differences in LD between the typed marker and nongenotyped functional SNP may explain the conflicting associations [39]. Other possible explanations for this flip-flop association include differences in environmental exposures, epistatic interactions, or gene-by-environment interactions (not modelled in the present analysis) between the two cohorts.

In conclusion, to the best of the present authors’ knowledge, this is the first time that genetic variation in the VEGF polymorphism gene has been associated with asthma and airway responsiveness in two cohorts of children with mild-to-moderate persistent asthma, suggesting a role of VEGF polymorphism in the development of asthma. The present study also demonstrates preliminary associations of VEGF polymorphism variation with lung function in both the CAMP and Costa Rican cohorts, though additional fine mapping of this region, along with additional replication studies in other populations, will be needed to resolve the directionality issues noted. If the observed effects of VEGF genetic variation on lung function are corroborated in future studies, the functional markers may serve as potential biomarkers for the identification of susceptible individuals who could benefit from novel therapies that target VEGF pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SUPPORT STATEMENT

The Childhood Asthma Management program (CAMP) Genetics Ancillary Study is supported by grants U01 HL075419, U01 HL65899, P01 HL083069, R01 HL 086601, and T32 HL07427 from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI), National Institutes of Health (NIH). B.A. Raby is a recipient of a Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award from NIH/NHLBI (K08 HL074193). The Genetics of Asthma in Costa Rica study was supported by NIH/NHLBI grants HL04370 and HL66289.

The present authors thank all subjects for their ongoing participation in this study. They acknowledge the CAMP investigators and research team, supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, for collection of CAMP Genetic Ancillary Study data. All work on data collected from the CAMP Genetic Ancillary Study was conducted at the Channing Laboratory of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital under appropriate CAMP policies and human subject protections.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

None declared.

References

- 1.Sears MRGJ, Willian AR, Wiecek EM, et al. A longitudinal population-based cohort study of childhood asthma followed into adulthood. Am Rev Respir Dis. 2003;349:1414–1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoshino MNY, Hamid QA. Gene expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors and angiogenesis in bronchial asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:1034–2001. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee CG, Link H, Baluk P, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) induces remodeling and enhances TH2-mediated sensitization and inflammation in the lung. Nat Med. 2004;10:1095–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baluk PLC, Link H, Ator E, et al. Regulated angiogenesis and vascular regression in mice overexpressing vascular endothelial growth factor in airways. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1071–1083. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63369-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simcock DE, Kanabar V, Clarke GW, et al. Proangiogenic activity in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:146–153. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200701-042OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feltis BN, Wignarajah D, Zheng L, et al. Increased vascular endothelial growth factor and receptors: relationship to angiogenesis in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1201–1207. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1105OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Liu CT, Wu YH, et al. Budesonide/formoterol decreases expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptor 1 within airway remodelling in asthma. Adv Ther. 2008;25:342–354. doi: 10.1007/s12325-008-0048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banyasz I, Szabo S, Bokodi G, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of vascular endothelial growth factor in severe pre-eclampsia. Mol Hum Reprod. 2006;12:233–236. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gal024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boiardi L, Casali B, Nicoli D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor gene polymorphisms in giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2160–2164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buraczynska M, Ksiazek P, Baranowicz-Gaszczyk I, et al. Association of the VEGF gene polymorphism with diabetic retinopathy in type 2 diabetes patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:827–832. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raby BA, Silverman EK, Kwiatkowski DJ, et al. ADAM33 polymorphisms and phenotype associations in childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. Long-term effects of budesonide or nedocromil in children with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1054–1063. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010123431501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. The Childhood Asthma Management Program (CAMP): design, rationale, and methods. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:91–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunninghake GM, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, et al. Sensitization to Ascaris lumbricoides and severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escamilla MA, Spesny M, Reus VI, et al. Use of linkage disequilibrium approaches to map genes for bipolar disorder in the Costa Rican population. Am J Med Genet. 1996;67:244–253. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960531)67:3<244::AID-AJMG2>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thorisson GA, Smith AV, Krishnan L, et al. The International HapMap Project Website. Genome Res. 2005;15:1591–1593. doi: 10.1101/gr.4413105. ( http://www.hapmap.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sherry ST, Ward MH, Kholdov M, et al. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.308. ( www.ncbi.nlh.nih.gov/projects/SNP/index.html) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haldane J. An exact test for randomness of mating. J Genet. 1954;52:631–635. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whittemore AS, Halpern J, Ahsan H. Covariate adjustment in family-based association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;28:244–255. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyholt DR. A simple correction for multiple testing for single-nucleotide polymorphisms in linkage disequilibrium with each other. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:765–769. doi: 10.1086/383251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity. 2005;95:221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296:2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lange C, van Steen K, Andrew T, et al. A family-based association test for repeatedly measured quantitative traits adjusting for unknown environmental and/or polygenic effects. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:1–27. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lake SL, Laird NM. Tests of gene-environment interaction for case-parent triads with general environmental exposures. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68:55–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher RA. Statistical Methods for Research Workers. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd; 1932. pp. 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaykin DV, Zhivotovsky LA, Westfall PH, et al. Truncated product method for combining P-values. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;22:170–185. doi: 10.1002/gepi.0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park HK, Park HW, Jeon SG, et al. Distinct association of genetic variations of vascular endothelial growth factor, transforming growth factor-beta, and fibroblast growth factor receptors with atopy and airway hyperresponsiveness. Allergy. 2008;63:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strunk RC, Weiss ST, Yates KP, et al. Mild to moderate asthma affects lung growth in children and adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warburton D, Bellusci S, De Langhe S, et al. Molecular mechanisms of early lung specification and branching morphogenesis. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:26R–37R. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159570.01327.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange PPJ, Vestbo J, Schnohr P, Jensen G. A 15-year follow-up study of ventilatory function in adults with asthma. New Engl J Med. 1998;339:1194–2000. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810223391703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hersh CP, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, et al. Genome-wide linkage analysis of pulmonary function in families of children with asthma in Costa Rica. Thorax. 2007;62:224–230. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.067934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Postma DSMD, Jongepier H, Howard TD, et al. Genomewide screen for pulmonary function in 200 families ascertained for asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:446–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200407-864OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chetta A, Zanini A, Foresi A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulation and bronchial wall remodelling in asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35:1437–1442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glatt SJ, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Association between a functional catechol O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and schizophrenia: meta-analysis of case-control and family-based studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:469–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolsch H, Linnebank M, Lutjohann D, et al. Polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferase omega-1 and AD, vascular dementia, and stroke. Neurology. 2004;63:2255–2260. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147294.29309.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li YJ, Oliveira SA, Xu P, et al. Glutathione S-transferase omega-1 modifies age-at-onset of Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:3259–3267. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanders AR, Rusu I, Duan J, et al. Haplotypic association spanning the 22q11. 21 genes COMT and ARVCF with schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:353–365. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin PI, Vance JM, Pericak-Vance MA, et al. No gene is an island: the flip-flop phenomenon. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:531–538. doi: 10.1086/512133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.