In the U.S., perinatal depression is the subject of both powerful legislative initiatives and laws, which must be integrated into the developing landscape of services and research. Initiatives include mandates to screen perinatal women, which have been spurred, in part, by accumulating evidence that perinatal depression is not only widespread but can have a major impact on child development and well-being. Nevertheless, from a healthcare perspective, this viewpoint is relatively new and, from a legislative standpoint, the legal implications are in a state of flux; thus it is not surprising that social scientists specializing in perinatal mental health find it challenging both to track current legislation concerning perinatal depression and to understand the laws governing court decisions. To address this potential for confusion concerning such a critical issue, an interdisciplinary team of academics, with expertise in perinatal mental health and law, collaborated to review the status of enacted state and federal legislation pertaining to perinatal depression. Summarized here are the teams’ findings and a description of U.S. laws that form the basis of court decisions in cases where postpartum psychosis culminated in filicide. To provide an appropriate context, the article first briefly reviews empirical evidence documenting that perinatal depression is a significant public-health problem, then briefly summarizes the status of evidence on the effectiveness of screening.

Research Evidence: A Context for Legislation

Prevalence and Negative Effects

As early as 1968, a large-scale study assessed the prevalence of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period; this study concluded that, of the 305 women interviewed, 10.8% could be diagnosed with postpartum depression (Pitt 1968). Now, some forty years later, the most recent meta-analytic review of postpartum depression came to similar conclusions; after compiling studies based on structured diagnostic interviews, this report determined that, in the first three postpartum months, approximately 7% of women met the diagnostic criteria for Major Depressive Disorder while 19.2% of women met the diagnostic criteria for Major or Minor Depressive Disorder (Gavin et al. 2005).

In parallel to these epidemiological findings, substantial empirical evidence links maternal depression to poor infant and child outcomes. One early review of research on this topic noted that the discovery of how maternal depression affects children was curiously serendipitous (Downey and Coyne 1990). Specifically, in the 1970’s researchers studying the negative effects of maternal schizophrenia, included children of depressed mothers as a control group, only to unexpectedly discover equally poor performance among children of both groups. Children of depressed mothers thus became a focus of subsequent empirical research that has conclusively revealed that exposure to postpartum depression places infants at risk for delays in cognitive, motor, and language development (Goodman 2007; O’Hara and McCabe 2013).

Screening: Controversial Debate

Spurred by these accumulated empirical findings, early identification and treatment of perinatal depression is now broadly recognized; and in several countries screening for perinatal depression is integrated into standard healthcare protocols. In the U.S., depression screening for all adults, including postpartum women, is recommended with the qualifier that it is beneficial “when staff-assisted depression-care supports are in place to assure accurate diagnosis, effective treatment, and follow-up” (United States Preventive Services Task Force 2009, p. 784). For perinatal women specifically, depression screening is recommend by several U.S. national healthcare organizations (American College of Nurse-Midwives 2002; Association of Women’s Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses 2008; National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners 2003). In 2000, the empirical link between maternal depression and poor infant outcomes prompted the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau (HRSA-MCHB) to designate maternal depression screening and referral as a core component of home visiting services provided by the Healthy Start program (Berry et al. 2010). In England, the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued what is perhaps the first national-level recommendation for universal screening of depression of perinatal women (National Collaborating Center for Mental Health 2007). Similar national-level recommendations for perinatal depression screening have been issued in New Zealand, Australia and Norway (Meltzer-Brody 2011).

Despite growing international public recognition of the importance of early identification and referral, the requirement to screen for maternal depression remains the subject of considerable debate. U.S. and British organizations charged with evaluating the evidence base for screening perinatal women concluded it was not an effective protocol (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2010; Hill 2010). The British National Screening Committee (NSC) specifically noted that 1) insufficient evidence supports that screening improves maternal and infant outcomes and 2) universal identification strategies are too expensive due to costs associated with false positives. Nevertheless, evidence that screening indeed improves outcomes is emerging. The results of two U.S. trials and one in France report that compared to either usual care (Chabrol et al. 2002; Yawn et al. 2012) or a historical control (Miller et al. 2012), depression screening indeed prompted more affected women to initiate treatment. More importantly, when such studies compared universal screening to usual care, they found screening significantly improved outcomes in depressed mother (Chabrol et al. 2002; Yawn et al. 2012) Yet, the success of maternal depression screening programs has also been disputed by negative evaluation results both in terms of treatment initiation as well as maternal mood (Yonkers et al. 2009).

Quite apart from the heated academic debate, and despite a lack of firm evidence showing maternal depression screening improves outcomes, a wide range of legislation has already been enacted that has serious implications for women affected by perinatal depression. These initiatives were spurred by a host of social and political factors, including highly publicized, tragic critical incidents of suicide and filicide by mothers with postpartum psychosis, as well as awareness-raising efforts of influential people who experienced postpartum depression. The following is a review of enacted state and then federal legislation.

State Legislative Initiatives

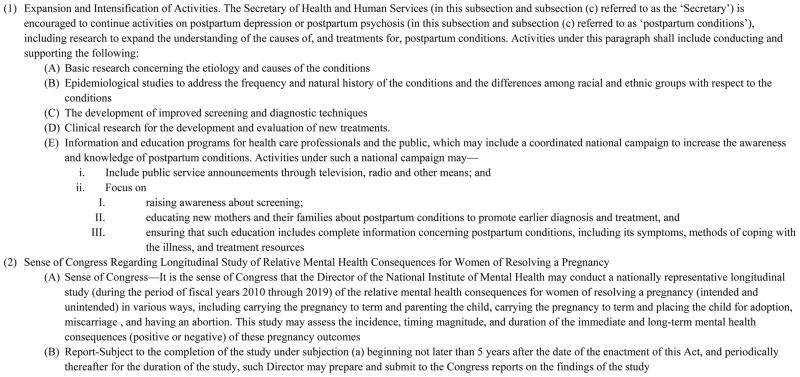

Although many U.S. states have implemented perinatal depression initiatives through private or public health-based venues, this review focuses on state legislative initiatives. For our purposes, state legislation was identified through a search of the legal database, LexisNexis, using the keywords “status, postpartum, perinatal depression.” This search identified legislation that also failed to be passed; however, we will discuss only enacted legislation, to provide a clear view of the current status of perinatal depression legislation. As outlined in the timeline provided in Figure 1, enacted legislation falls into three categories: mandatory screening and education, mandatory education, and awareness/planning initiatives.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Enacted State Legislation Addressing Perinatal Depression

Mandatory Screening and Education

The first state law requiring mandatory screening for postpartum depression was passed in 2006, by New Jersey. This law was advocated for by the former first lady, Mary Jo Codey, who herself had suffered from postpartum depression. The law, introduced as An Act Concerning Postpartum Depression, requires postpartum depression screening and education, and also requires that providers ask pregnant women about their history of depression. In addition, new mothers must be screened for depression and new parents must receive information about postpartum depression. The law is now codified under the title: Findings, Declarations Relative to Postpartum Depression (2006).

Shortly after New Jersey passed this law, Illinois enacted the Perinatal Mental Health Disorders Prevention and Treatment Act (2008). This act requires several state agencies to develop pertinent educational programs for women and their families, and provide screening questionnaires for use in prenatal and well-child healthcare visits. (These agencies include the Departments of Human Services, Healthcare and Family Services, Public Health, as well as professional licensing boards.) The act also provides for reviewing the questionnaire in accordance with recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and requires patient consent for the screening, unless a mother poses a danger to herself or others.

The most recent state to legislatively require education and screening of perinatal women was West Virginia. Their Uniform Maternal Screening Act (2009) authorized the Department of Health’s advisory council to develop a tool to identify women at risk for pre-term birth or other high-risk conditions. Once this state has determined how it will conduct screening, the act requires women entering prenatal care to be assessed for their risk for depression.

Mandatory Education

Several states have passed legislation requiring that pregnant women and new mothers receive educational material on postpartum depression. In 2003, the Texas House of Representatives passed a first bill on perinatal depression, colloquially referred to as the “Andrea Yeats Bill,” which required the State Department of Health to maintain a web-based resource list of professionals who can offer advice or services to families affected by perinatal depression. This legislation was later substantially revised and reintroduced as an act: Relating to Information Provided to Parents of Newborn Children (2005). The revised legislation requires healthcare professionals and agencies serving perinatal women to provide information on perinatal depression. The Department of Health and Human Services developed a brochure to fulfill this requirement. Additionally, the Health and Human Services Commission was required to conduct a study assessing the feasibility of providing twelve months of Medicaid health services to women diagnosed with postpartum depression.

Also of note, early on, Virginia passed a similar bill requiring all staff who provide maternity care to both distribute and discuss information about perinatal depression with families. This law is entitled Certain Information Required for Maternity Patients (2003).

Minnesota passed legislation requiring mandatory education about perinatal depression in the form of a bill entitled, Postpartum Depression Education and Information (2010, 2012). The first bill required the commissioner of health to work with mental health professionals, advocates, consumers and families to develop materials about postpartum depression. The resulting Minnesota education model, disseminated through the State Department of Health, exemplifies an effective educational resource. Their website features fact sheets and brochures in English, Spanish, Russian and Hmong, and links to a variety of healthcare programs, websites and helplines; it also contains several tools for assisting mothers and providers (Minnesota Department of Health, 2005). In 2012, the bill was amended to require mandatory distribution of these materials to perinatal women. The amendment particularly sought to rectify the problem of disseminating the information to low-income women, by making it available at Women Infant and Children (WIC) program sites. Further, the amended bill requires steps supporting eventual screening implementation; specifically, the commission of health must provide technical assistance to healthcare providers, with the goal of improving maternal depression screening and referral rates. Finally the bill requires the commission of Human Services, Health, and Education to develop a plan to reduce the prevalence of parental depression and other serious mental illness, as well as to address the impact of mental illness on children.

Most recently, Oregon passed an act entitled Relating to Perinatal Mental Health Disorders and Declaring an Emergency (2011). The act requires training for health care professionals who serve postpartum women as well as the development of training and informational materials to educate the public. Finally it requires that health professionals provide the informational materials to new mothers before they are discharged from the hospital.

Awareness/Planning Initiatives

To expand the information available to health professionals, state legislators have passed legislative initiatives in three categories: awareness campaigns, designation of a special month devoted to postpartum depression, and the appointment of a perinatal depression task force that will develop best-care practices.

Awareness campaigns

The state of Washington launched an awareness initiative by passing legislation entitled: Postpartum Depression – Public Information and Communication Outreach Campaign (2009). The Washington Council for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect was chosen to lead the campaign and state funds were allocated to support it. The campaign identified interested parties, developed a brochure, a website, a communications network and also conducted broad educational programs to raise awareness of the mental health issues faced by women during pregnancy and postpartum period.

Postpartum depression months

To raise awareness, three states have declared a postpartum depression month. In 2009, Oregon State Representative Carolyn Tomie introduced a resolution recognizing March as Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month; this legislation passed in 2011. In Michigan, Governor, Jennifer Granholm, issued a 2010 proclamation summarizing the incidence and negative effects of postpartum depression. In proclaiming May as an awareness month, she expressed the goal of raising awareness and educating new parents, the public, and health care practitioners. Although the designation of a postpartum depression awareness month was not achieved through legislation, as a proclamation it can be considered an official government action. In California, in the same year, the combined efforts of Assemblyman Pedro Nava and the Junior Leagues designated May as Perinatal Depression Awareness Month (2010). Awareness-raising activities conducted during the designated months include gubernatorial proclamations, feature news stories, and widespread distribution of educational posters and information packets.

Task force appointments

Maine was the first state to appoint a perinatal depression task force though legislation: An Act Concerning Postpartum Mental Health Education (2007). This legislation created a work group charged with reviewing screening and education efforts, barriers to care, current programs, and efforts by other states. The work group reported back to the legislature in 2008 but, as yet, no further legislative action has been taken.

In 2009, Oregon State Representative, Carolyn Tomei, proposed House Bills 2666 and 2666A, which created, within the Department of Human Services, a statewide work group that focuses on perinatal mood disorders. These bills were enacted under the title: Relating to Perinatal Mental Health Disorders; and Declaring an Emergency in 2011. As a result of this legislation, a task force group was appointed to study needs, best practices, and funding resources for improved care in Oregon.

The Massachusetts legislature, in 2010, also appointed a task force through the legislation: An Act Relative to Postpartum Depression. This act established an expert panel to advise the governor on current relevant research, including best and promising practices to prevent, detect, and treat postpartum depression; the panel will also recommend policies and legislation to promote greater public awareness, screening, and treatment. The bill also targets healthcare providers by requiring the development of regulations demanding that healthcare providers report annually on postpartum depression screening. The full commission has created subcommittees on screening, referrals, professional education, public education, and outcomes. The commission also developed a legislative work plan, to be introduced in the 2013–14 session. In addition to gathering data and assembling resources for health professionals, the commission is implementing a community-based screening model and a public information program.

Federal Legislative Initiatives

The greatest potential for impact, however, comes from federal legislation. Such legislation benefits from being uniform throughout the fifty states. The first federal legislation on perinatal depression was precipitated by a critical incident, the death of Ms. Melanie Blocker-Stokes. This Chicago native was a successful professional who gave birth to a daughter in February 23, 2001 and consequently developed a postpartum psychosis. She was hospitalized three times, for seven to ten days each time, but despite aggressive medical intervention and the support of her family, on June 12, 2001, she jumped from a 12-story window ledge to her death.

In direct response to this tragic event, the Melanie Blocker-Stokes Postpartum Depression Research and Care Act (2003) was introduced by Illinois Representative Bobby Rush, and then referred to a legislative subcommittee that had jurisdiction over health issues. For three subsequent sessions of Congress, which covered a span of six years, this bill was re-introduced and discussed in subcommittee. It was finally passed by the House of Representatives in 110th Congress and referred to a Senate subcommittee, but no further legislative action was taken. In 2009, the Melanie Blocker Stokes Act was renamed the Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act or “Moms Opportunity To access Health, Education, Research and Support.” This revised act was introduced into the Senate by Senators Robert Durbin of Illinois, Olympia Snowe of Maine, Sheldon Whitehouse of Rhode Island, Sherrod Brown of Ohio, and Dick Menendez and Frank Lautenberg. The latter two are both senators from New Jersey, which has been noted as the state whose First Lady has been a strong advocate of this type of legislation.

Ultimately, it was the MOTHERS Act that was incorporated into the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In the 2008 presidential election, health reform was central to Obama’s legislative platform; and after being elected, he directed the Democratic leadership to develop legislation to cover the uninsured, reduce healthcare costs, and improve healthcare quality. Thus, before Congress recessed in August of 2009, four health care reform proposals were drafted. Nevertheless, Congress disagreed on these proposals, preventing any bill from going beyond the committee.

Early in 2010, Democrats in the House of Representatives drafted a compromise bill that narrowly passed on March 21, 2010 (220 to 211). Importantly, when this bill then went to the Senate, it was combined with the Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. This, in combination with a “reconciliation act,” significantly facilitated a positive outcome: the combined bill was not subject to filibuster. Had the proposed healthcare bill not been combined with the reconciliation act, the bill would have gone to the Senate, where the opposition would have likely employed the filibuster technique to delay and ultimately prevent a vote. Instead, the combined bill, which now needed only a majority of votes, was passed—again by a narrow margin (51 to 48). In the process of getting enough votes to pass, legislators added a large number of amendments, many of them related to health care and one of which was the MOTHERS Act. Ultimately, language from the MOTHERS Act was included in Section 2952 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010).

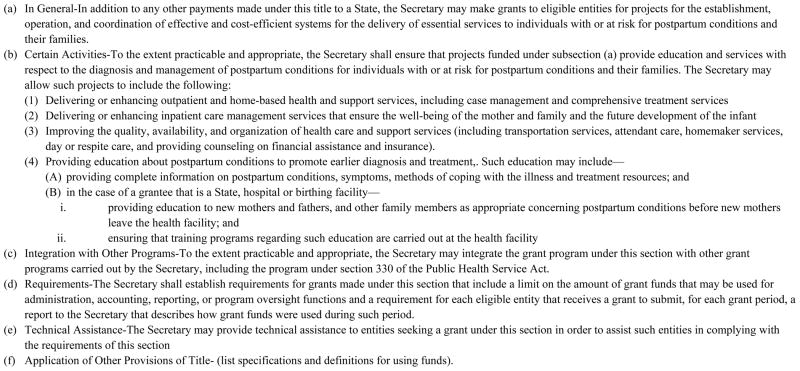

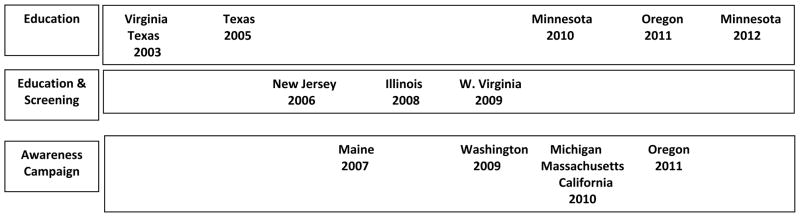

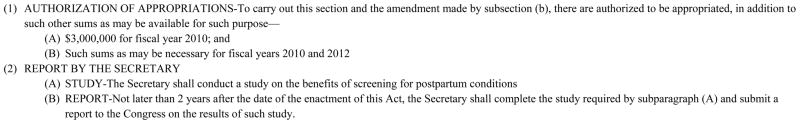

Like the MOTHERS Act, Section 2952 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act aims to expand research on postpartum depression and evaluate service models. Specifically, Section 2952, entitled Support, Education, and Research for Postpartum Depression, has three provisions plus a “sense of congress” statement. Section 2952a, entitled Research on Postpartum Conditions, directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to expand and intensify research on postpartum depression and psychosis (Figure 2). Section 2952a also includes the sense of congress statement, which directs future actions of the Director of the National Institute of Mental Health. The second provision, Section 2952b, authorizes grants to support the establishment, operation, and delivery of effective and cost-efficient systems for providing clinical services to women with, or at risk for, postpartum depression or psychosis (Figure 3). Section 2952c, entitled General Provisions, appropriates money to study the benefits of screening and requires a report to Congress on the study results (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Section 2952A: Research on Postpartum Conditions

From: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2952 (a), (b), (c); Sec. 2713. (2010)

Figure 3.

Section 2952 B: Grants to Provide Services to Individuals with a Postpartum Condition and Their Families- (Title V of the Social Security Act (42: U.S.C. 701 et seq.) as amended by section 2951, is amended by adding at the end the following new section:

From: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2952 (a), (b), (c); Sec. 2713. (2010)

Figure 4.

Section 2952C: General Provisions

From: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2952 (a), (b), (c); Sec. 2713. (2010)

It is important to note the focus of Section 2952 is research and the provision of services; however, although it recommends research on the development of screening and diagnostic programs, it does not specifically recommend screening per se. Instead, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Section 2713 (2010), entitled Coverage of Preventive Health Services, requires that healthcare providers and insurance companies support any preventive health services backed by evidence that is graded by the USPSTF as ‘A’ or ‘B’ (Figure 5). Because the USPSTF recommends depression screening of all adults based on Grade-B evidence, this broad mandates covers depression screening of perinatal women.

Figure 5.

Section 2713. Coverage of Preventive Health Services

From: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2952 (a), (b), (c); Sec. 2713. (2010)

After federal legislation is passed, the rules that will define, interpret, and implement it must be established. This is particularly true after passage of legislation as significant as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. In the case of the Sections 2952 and 2713, the Department of Health and Human Services will pass administrative rules. In 2010 the rules for Section 2713 were published (45 Code of Federal Regulations Part 147, 2010). These rules incorporate the USPTSF recommendations for depression screening of all adults, which is now a required element of all health plans. To date, no rules have been issued for the implementation of Section 2952; however, in fiscal year 2010, three million dollars were appropriated for relevant research and clinical mandates. Still, no funds have been distributed because of challenges to the constitutionality of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010). Although the United States Supreme Court recently judged that the act is constitutional (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius 2012), full implementation was delayed until the re-election of President Obama in 2012. With his re-election, however, we expect final rules on Section 2952 to be issued, as should rules governing the other provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which phases in over a four-year period.

U.S. State Criminal Law

In the U.S. system of government, new federal and state legislation requires that new laws be created. This is the expected next phase of any legislation pertaining to the identification and management of the perinatal depression. The interpretation of laws and their application to individual cases is the function of the judicial branch, i.e., the court system. Postpartum mood disorders generally become a criminal issue in cases involving mothers who kill their children (Spinelli 2003). In the U.S., mothers accused of the murder of their infants/children have been charged under the state’s criminal code and tried in a state court.

To find a woman accused of murdering her child guilty, a prosecutor must prove guilt according to two elements: the act (known as the actus reas) and the intent (known as the mens rea). Mens rea refers to the mental or cognitive elements of intent at the time of the crime. For the crime of murder, the mental element required is knowledge of one’s actions at the time and understanding that the act was wrong. As a form of defense two pleas can be used: diminished capacity or insanity. To claim diminished capacity, defendants claim guilt in breaking the law but also claim impaired functioning; thus, if found guilty they are not held criminally liable and usually receive a reduced sentence. In contrast, taking an insanity defense asserts that the defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity, and therefore not culpable. For perinatal mental health researchers and clinicians, it is critical to note that in the U.S. judicial system “psychosis of itself does not determine the legal definition or defense of insanity” (Spinelli, 2004, p. 1152). Rather, more abstract, legal definitions are applied. This section describes these legal definitions and then discusses the relevance of psychiatric nosology.

U.S. Legal Definitions of Insanity

In the U.S., insanity is, with only exception, defined by one of two rules adopted by states that retain the insanity defense: the M’Naghten Rule or the Model Penal Code. The one exception is New Hampshire which still uses the Durham Rule. Among the 46 states that retain an insanity defense, the definition used by each state is listed in Table 1. As a result, in cases in which postpartum mental illness culminated in infanticide, courts in various state jurisdictions have responded in very different ways. In some cases, women were found not guilty by reason of insanity and ordered to undergo long-term psychiatric treatment. In other very similar cases, sometimes even in the same state, women were found guilty and sentenced to lengthy prison terms. These widely varying decisions and sentences are due, in some part, to the use of one of the two different definitions of insanity.

Table 1.

The insanity defense among the states

| Tally | M’Naghten Rule | Model Penal Code |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alabama | Arkansas |

| 2 | Alaska | Connecticut |

| 3 | Arizona | Delaware |

| 4 | California | District of Columbia |

| 5 | Colorado | Hawaii |

| 6 | Florida | Illinois |

| 7 | Georgia | Indiana |

| 8 | Iowa | Kentucky |

| 9 | Louisiana | Maine |

| 10 | Minnesota | Maryland |

| 11 | Mississippi | Massachusetts |

| 12 | Missouri | Michigan |

| 13 | Nebraska | New York |

| 14 | Nevada | North Dakota |

| 15 | New Jersey | Oregon |

| 16 | New Mexico | Rhode Island |

| 17 | North Carolina | Tennessee |

| 18 | Ohio | Vermont |

| 19 | Oklahoma | West Virginia |

| 20 | Pennsylvania | Wisconsin |

| 21 | South Carolina | Wyoming |

| 22 | South Dakota | |

| 23 | Texas | |

| 24 | Virginia | |

| 25 | Washington |

Note. This data for this table was summarized on the basis of the material provided by the U.S. Legal Law Digest on a public website entitled “The Insanity Defense Among the States.” http://lawdigest.uslegal.com/criminal-laws/insanity-defense/7204. Accessed 1 April 2013

Four states do not recognize insanity as a defense: Idaho, Kansas, Montana and Utah. New Hampshire is the only state that uses the Durham rule.

M’Naghten Rule

The M’Naghten rule arises from an 1843 case in which Daniel M’Naghten, who displayed symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia, attempted to kill the British prime minister because of his delusional belief that the prime minister was persecuting him. M’Naghten, however, mistakenly shot the wrong person (Daniel M’Naghten’s Case, 1843). At trial, he was judged to be “not guilty” on the grounds that he was insane at the time of his act. Public outrage against this decision resulted in standards or rules for governing the insanity defense.

It is notable that the M’Naghten Rule is based on the presumption of sanity. This means that insanity at the time of committing the act must be clearly proven. According to this rule, insanity is defined as either an inability to understand the nature and quality of the act, or the inability to understand that the act was wrong. Importantly, the narrow cognitive emphasis of this legal definition does not address the idea that hallucinations or delusions can impair control over behavior. Accordingly, the “deific decree doctrine” provides an exception to this strict cognitive interpretation. This decree, which maintains a cognitive emphasis, exonerates a defendant who believes that s/he was commanded by God to commit an unlawful act, and is based on the understanding that any commandment from God is necessarily a delusion and cannot be real (Morris and Haroun, 2001).

This emphasis on assessing cognitive capacity can play a pivotal role in verdicts based on the M’Naghten Rule. Moreover, the importance of interpreting the deific defense is revealed by the widely divergent verdicts of two high-profile Texas criminal cases. In the first, State v. Yates (2002), the defense was found guilty by the jury, who rejected an insanity plea notwithstanding legal and psychiatric opinion that the defendant was psychotic (Spinelli 2005). The insanity plea was rejected because, after the murders, Ms. Yates immediately called 911 and her husband, indicating she understood what she had done was wrong (Spinelli 2004). Although the prosecution sought the death penalty, the jury instead sentenced her to life imprisonment with eligibility for parole in 40 years. In a second case of filicide, Laney v. State (2003), the defendant claimed that she acted under God’s orders. Five mental health experts (the prosecution and defense each ordered two and the judge ordered one) unanimously agreed that, at the time of the murders, Ms. Laney was experiencing psychotic delusions that impaired her ability to know right from wrong. She was therefore found not guilty by reason of insanity and ordered to a maximum security inpatient treatment facility. Eventually she was released with supervisory provisions.

Model Penal Code

Because some deemed as unsatisfactory the M’Naghten Rule’s exclusive cognitive focus in defining insanity, two broader definitions were subsequently incorporated into some state penal codes. The Irresistible Impulse Test, introduced into broad usage in an Alabama case (Parsons v. Alabama, 1887), recognized that although a mental disease (such as psychosis) might not affect the ability to understand (cognitively determined) right from wrong, it can significantly affect the ability to choose (behaviorally determined) between right and wrong. The Durham Rule, first articulated in a single New Hampshire case in 1871, was adopted by the Circuit Court of Appeals in a 1954 case that gave the rule its name: Durham v. U.S. (1954). This rule—that a person is not criminally responsible if the unlawful act resulted from a specific mental disorder—was an attempt to objectively define insanity through medical diagnoses. Nevertheless, this rule was eventually abandoned, except in the state of New Hampshire, because of its expansive definition of insanity.

Ultimately, the American Law Institute developed a broader definition of insanity as part of The Model Penal Code (American Law Institute 1962). This new definition, which incorporates aspects of both the Irresistible Impulse Test and the Durham Rule, states: "a person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct the unlawful act resulted from a mental disease (Durham Rule) or the lack of either the capacity to appreciate the criminality of the act (M’Naghten Rule) or the capacity to conform his/her conduct to the requirements of the law (Irresistible Impulse Test).

No Insanity Defense

The M’Naghten Rule and the Model Penal Code provide strictly legal approaches to defining insanity, which although flawed, at least provide a mechanism to protect women who suffer from postpartum mental disorders. Especially alarming is the fact that four states (Idaho, Kansas, Montana, and Utah) have abolished the insanity defense altogether. In these states, mentally ill defendants have no recourse of an insanity defense when accused of a crime. To be clear, this means that in these four states, a woman who kills her children as the result of a postpartum psychosis has no opportunity during the trial phase to assert that the illness influenced her behavior. It is also quite worth noting that all four of these states also have the death penalty which is most frequently applied to the crime of murder. The one mitigating recourse is that postpartum illness may be considered in the sentencing phase, which will likely replace the death penalty with significant periods of incarceration. Nonetheless, ultimately, the result is likely to be incarceration rather than mental health treatment.

Infanticide Acts: An International Approach

In the U.S, the approach of courts to women with postpartum mental illness varies among jurisdictions and these approaches are largely characterized on a spectrum of punitive outcomes—the worst being the four states without an insanity defense. While this review summarizes U.S. legislation and laws, it is worth noting that in an international context, the U.S. judicial approach is uniquely punitive. Specifically, Spinelli (2005) in a historical review of approaches to infanticide, traces the first infanticide act to 1647, when Russia legally distinguished infanticide from murder by issuing more lenient penalties in infanticide cases. England, which passed an Infanticide Act in 1922 and amended it in 1938, recognizes the biological vulnerability of postpartum women. This act typically results in more lenient sentences, which usually require psychiatric treatment. Currently, many developed and some developing countries have infanticide statutes, including most European countries, as well as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Korea, Turkey and India (Spinelli 2005).

Infanticide Acts in the U.S

In the U.S., some attempts have been made to adopt infanticide laws, replacing the insanity defense in cases of infanticide. In response to the two cases in Texas, a member of the State House of Representatives introduced an act, entitled An Act Relating to Creating an Offense for Infanticide (2009), which would have amended the Texas penal code to classify infanticide as a crime distinct from murder. This bill proposed that: (a) a person commits an offense if the person willfully, or by an act or omission, causes the death of a child to whom the person gave birth within the 12-month period preceding the child’s death and if, at the time of the act or omission, the person’s judgment was impaired as a result of the effects of giving birth or the effects of lactation following the birth; and (b) an offense under this section would be a state jail felony. In real terms, this revision of the penal code would mean that the crime would be changed from a capital offense (for which, if found guilty, the defendant could receive the death penalty) to a felony (for which the maximum sentence is imprisonment for 6 to 24 months). In this proposed legislation, infanticide would also have been added to the definition of murder in the Texas Penal Code. This proposed legislation faced considerable opposition in committee, and was the subject of a significant degree of public outrage; hence, it was not voted out of committee, and so was never introduced to the full legislative body.

Subsequently, a second bill was proposed that would have required the court to consider the presence of postpartum psychosis in a woman found guilty of murdering her child, during the sentencing phase. Under this bill, if a preponderance of the evidence proved that the murder was the result of postpartum psychosis, then the crime would be considered a state jail felony. Again, this proposed statute also did not get out of committee in the Texas legislature. Moreover, although it attempted to address the unique circumstances of postpartum psychosis, it applied only to the death of a child up to twelve months in age, and therefore would not have applied either to Ms. Yates or Ms. Laney.

The Relevance of Psychiatric Nosology

In the U.S. legal system, a person accused of a crime is both presumed innocent and, importantly, also presumed sane. This presumption of sanity means that in a criminal case of infanticide, the person who defends the mother must prove that she was insane when she killed her child. In asserting an insanity defense based on postpartum illness, it is essential that the defense attorney have two types of evidence: a documented diagnosis of a mental illness and evidence of the woman’s behavior before and immediately after the crime (evidence that demonstrates the inability to display specific intent). For the former, a lack of a specific diagnosis of postpartum psychosis in the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) presents a significant disadvantage. Although this current nosology includes “postpartum onset” as a “specifier” to the diagnosis of “Brief Psychotic Episode,” this diagnostic categorization does not provide compelling evidence to most courts or lay juries. An “onset specifier” is not a specific, identifiable diagnosis with characteristic symptoms and behaviors.

As noted in Spinelli (2005, p. 19): “Our reluctance to place postpartum disorders within a diagnostic framework often leads to tragic outcomes for women, family and society.” This view is supported by a recent review of the outcomes of 34 infanticide cases in which the defendant asserted postpartum illness. The outcomes of these trials suggest that, in cases of infanticide or filicide resulting from postpartum psychosis, the definition of insanity (i.e., M’Naghten or Model Penal Code) is a less significant determinant of verdict than the type of evidence presented to the jury (Nau et al. 2012). Specifically, among the 34 cases reviewed, verdicts of not guilty by reason of insanity were most likely rendered when the evidence supported the presence of psychotic symptoms, regardless of whether the definitions of insanity were based on the M’Naghten Rule or the Model Penal Code.

Discussion

This specialized review, considers both the status of state and federal legislation pertaining to perinatal depression, as well as U.S. laws. What have we learned about each of these legal venues?

When examining the range of enacted state legislation on perinatal depression, which is summarized in Figure 1, several themes become readily apparent. First, enacted state legislation is a relatively recent phenomenon that began only in the last decade. For example, in 2003, the case of filicide in Texas was the impetus for the Andrea Yeats Bill requiring mandatory education. A similar bill was passed by Virginia that same year. A second observation is that momentum is building that demands new state legislation. Between 2000 and 2006, only three states (New Jersey, Texas, and Virginia) passed relevant legislation. In contrast, during a comparable time frame between 2007 and 2012, the number of states passing relevant legislation has tripled (n=9; Illinois, West Virginia, Minnesota, Oregon, California, Michigan, Maine, Massachusetts, and Washington). Third, despite significant progress made by state legislatures, it is notable that only 12/50 or 24% of states have legislation pertaining to perinatal depression. Most major regions in the United States are represented (East, Central, West, and South), yet the absence of legislation in the majority of states is notable. Finally, legislative mandates to provide screening, the highest level of action, is implemented in only a minority of states: New Jersey in 2006, in 2008; and Illinois and West Virginia, in 2009.

While three states have mandated maternal depression screening, we could find only one formal evaluation of the impact of maternal depression screening (Kozhimannil et al. 2011). Using the New Jersey Medicaid database, this assessment evaluated rates of treatment initiation (e.g., filling prescription or attending a mental health visit), and follow-up or continued care (e.g., prescription refill or a second visit). Outcomes compared these two rates before and after the awareness initiative, as well as after the legislated screening mandate. Surprisingly, both treatment initiation and treatment use rates turned out to be unaffected by either the awareness initiative or the legislated screening mandate. The authors concede that several methodological limitations characterized this study. First, the study sample was limited to impoverished women in an urban setting. Second, although the New Jersey Postpartum Depression Act mandated depression screening, screening rates unfortunately could not be directly assessed because the New Jersey Medicaid program does not make payments specifically for depression screening. Notwithstanding these methodological limitations, the authors suggest that the apparent failure of this legislated policy was likely due to lack of both monitoring and means for enforcement, as well the fact that no provision was made to pay for screening activities.

At the federal level, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Section 2952 (Support, Education and Research for Postpartum Depression), galvanized by the death of Ms. Blocker Stokes, will provide extensive fiscal resources for research on perinatal mood disorders and also provide clinical services for women and families struggling with this illness. Although screening for perinatal depression, currently the subject of heated academic debate (Buist et al. 2002), is not mandated by Section 2952, funding for research on the benefits of screening is provided. Nevertheless, Section 2713 (Coverage of Preventive Health Services) provides fiscal coverage of preventive health services with a rating of Grade-A or Grade-B evidence by the USPTF; this may supersede the need for state or federal level legislation that is specific to perinatal depression screening. Based on grade-B evidence, the USPTF has already issued a recommendation for screening for depression of all adults when adequate follow-up care is provided, thus encompassing perinatal women. Subsequent rules have already been issued such that depression screening of all adults, including perinatal women, is now a required element of all health plans. Full implementation of Section 2952 awaits the publication of final rules.

While this review summarizes legislative initiatives pertaining to perinatal depression, it is important to recognize that legislation is not the only means to ensure that the mental health of perinatal women is included as a focus of clinical care. Several federal and private programs already address this disorder, including research-based as well as private and public-sector screening programs (Segre and O’Hara 2005). Additionally, although requiring depression screening and fiscal coverage of screening activities may permit health and social service providers’ reimbursed time to accomplish this task, legislative mandates alone cannot ensure that screening strategies are effectively implemented. Many treatment providers who care for perinatal women recognize the importance of screening for perinatal depression; however, they often do not feel their training on perinatal depression is adequate to support effective clinical management of their patients (Olson et al. 2002; Schmidt et al. 1997). In addition to legislative mandates to screen for perinatal depression, it is key to focus energy on educating health care and social services providers. To meet this educational need, perinatal depression researchers have developed a wide range of instructional approaches for health and social service providers, including web-based training (Baker, Kamke, O’Hara, and Stuart, 2009; Wisner, Logsdon, and Shanahan, 2008), one-to-one professional consultation (Chaudron, Szilagyi, Kitzman, Wadkins, and Conwell, 2004; Gordon, Cardone, Kim, Gordon, and Silver, 2006; Yonkers et al., 2009), and a “train-the-trainer” approach (Segre, Brock, O’Hara, Gorman, and Engeldinger, 2011). The additional federal funding issued by Section 2952 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act will be critical in addressing the identified gaps on perinatal depression screening outcomes and in establishing an evidence base of best practices.

When it comes to the issue of women with postpartum mood disorders and U.S. criminal prosecution, court decisions are governed by two different definitions of insanity. Thus, the outcomes for women accused of killing their children are unpredictable. Moreover, these definitions are outdated and do not conform to current psychiatric knowledge. While it would be ideal to enact a federal law similar to the laws of countries with infanticide statutes, enactment of federal infanticide legislation would be very difficult. Because the Constitution reserves matters of defining criminal conduct to individual states, enacting a federal statute that defines criminal conduct in a uniform way for a non-federal crime would raise significant issues of constitutional law and federal jurisdiction. Nonetheless, as has already been attempted in Texas, it would be worthwhile to pursue a strategy of enacting state laws similar to the two dozen countries with infanticide statutes. These acts require mental health treatment instead of punishment in cases infanticide or filicide resulting from a postpartum psychiatric illness.

Conclusions

The field of perinatal depression research has come a long way since 1968 when Brice Pitt first documented the prevalence of this disorder. The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) provides for comprehensive research and clinical services for postpartum mood disorders and requires that all adults be screened for depression in systems that provide adequate follow-up. This legislation represents a giant leap forward in recognizing postpartum mood disorders, not only in the perinatal period but, with the expanded focus on all adults, at any time throughout the adult lifespan. Nonetheless, an important take home point is that this global mandate does not guarantee successful local implementation, nor does it guarantee improved outcomes for women and children. The evidence base that screening ultimately improves outcomes in a cost effective manner has yet to be established. Moreover, a federal or state screening mandate does not guarantee that perinatal depression screening will be successfully implemented. For the future, however, the new funds issued for research on postpartum disorders and screening will spur acquisition of this evidence. In addition, funded state initiatives, such as a legislative appointment of multidisciplinary task force to evaluate best practices and recommend additional context-informed actions, as was done in Oregon, Maine and Massachusetts, remain important in ensuring the local success of a global mandate.

In stark contrast to the status of state and federal legislation pertaining to perinatal depression, the definitions of insanity that govern U.S. criminal laws lag behind both our current understanding of postpartum psychosis and international legal approaches. With regard to the courts and women with postpartum mental illness, it would be helpful if future revisions of the DSM recognized postpartum psychosis as an independent diagnosis. This categorization would give weight to expert testimony on the matter of a woman’s ability to form the specific intent to commit the crime of killing her child. The evidence suggests that a DSM-recognized diagnosis could provide critical leverage in establishing an insanity defense.

In an educated society which has developed a sophisticated understanding of mental illness, can we really still justify the criminal incarceration of women who are clearly mentally ill? Existing legal constructs of insanity are, at best, coarse-grained tools of a criminal justice system specifically designed to establish guilt and ultimately determine punitive sanctions. The message of this review is that a more nuanced and enlightened understanding of guilt or innocence, which still acknowledges the gravity of the offense, may be in reach of our society if the tools of psychiatric diagnoses are judiciously applied.

Acknowledgments

Removed for Blind Review

Contributor Information

Ann Rhodes, The University of Iowa, College of Nursing/College of Law, 50 Newton Road, Rm. 360 CNB, Iowa City, IA 52242.

Lisa Segre, Email: lisa-segre@uiowa.edu, The University of Iowa, College of Nursing, 50 Newton Road, Rm. 356 CNB, Iowa City, IA 52242, Phone: 319-335-7079.

References

- 45 Code of Federal Regulations Part 147 (2010)

- American College of Nurse-Midwives. [Accessed 20 June 2012];Depression in women: Position statement. 2002 http://www.midwife.org/siteFiles/position/Depression_in_Women_05.pdf.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Screening for depression during and after pregnancy: Committee Opinion No. 453. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:394–395. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d035aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Law Institute, Model Penal Code, Article 2, Sec. 2.02 (1962)

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Assocation; Arlington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- An Act Concerning Postpartum Mental Health Education, 22 ME. Rev. Stat. Sec. 1, Sec. 262 (2007)

- An Act Relating to Creating and Offense for Infanticide, TX H.B. 3318 (2009)

- An Act Relative to Postpartum Depression, MA. Acts Chapter 313 (2010)

- Association of Women’s Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. [Accessed 29 March 2013];The role of the nurse in postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. 2008 http://www.awhonn.org/awhonn/content.do?name=05_HealthPolicyLegislation/5H_PositionStatements.htm.

- Baker CD, Kamke H, O’Hara MW, Stuart S. Web-based training for implementing evidence-based management of postpartum depression. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22:588–589. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.05.080265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry E, Brady C, Cunningham SD, Derrick LL, Drummonds M, Petiford B, et al. A national network for effective home visitation and family support services. National Healthy Start Association; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Buist A, Barnett BEW, Milgrom J, Pope S, Condon JT, Ellwood DA, et al. To screen or not to screen - that is the question in perinatal depression. Med J Aust. 2002;177:s101–s105. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certain Information Required for Maternity Patients, VA. Code Ann. Sec. 32.1–134.01 (2003)

- Chabrol H, Teissedre N, Roge B, Mullet E, Roge B, Mullet E. Prevention and treatment of post-partum depression: A controlled randomized study on women at risk. Psychol Med. 2002;32:1039–1047. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudron LH, Szilagyi PG, Kitzman HJ, Wadkins HIM, Conwell Y. Detection of postpartum depressive symptoms by screening at well-child visits. Pediatrics. 2004;113:551–558. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M’Naghten’s Case, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (U.K.H.L. 1843)

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychol Bull. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durham v. U.S., 214 F, 2d 862 (D.C. Cir. 1954)

- Findings, Declarations Relative to Postpartum Depression, NJ. Stat. Ann. Title 26 – Health and Vital Statistics Sec 26:2–175 (2006)

- Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH. Depression in mothers. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:107–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon TEJ, Cardone IA, Kim JJ, Gordon SM, Silver RK. Universal perinatal depression screening in an academic medical center. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:342–347. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000194080.18261.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. An evaluation of screening for postnatal depression against NSC criteria. [Accessed 1 April 2013];National Screening Committee Report. 2010 http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/topic/postnatal-depression.

- Infanticide Act, All E. R. 1 & 2 Geo. 6, ch.36 Sec. I (1938)

- Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA. New Jersey’s efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Affairs. 2011;30:293–301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laney v. State, 117 SW 3d 854 (2003)

- Maternal Mental Health Awareness Month, OR. Rev. Stat. Sec. 187.233 (2011)

- Melanie Blocker-Stokes Postpartum Depression Research and Care Act House, H. R. 846, 108th Cong. (2003)

- Melanie Blocker Stokes MOTHERS Act, H. R. 20, 111th Cong. (2009)

- Meltzer-Brody S. New insights into perinatal depression: Pathogenesis and treatment during pregnancy and postpartum. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2011;13:89–100. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.1/smbrody. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ, McGlynn A, Suberlak K, Rubin LH, Miller M, Pirec V. Now what? Effects of on-site assessment on treatment entry after perinatal depression screening. J Womens Health. 2012;21:1046–1052. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnesota Department of Health. [Accessed 1 April 2013];Postpartum depression education materials. 2005 http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/fh/mch/fhv/strategies/ppd/index.html.

- Morris GH, Haroun A. “God told me to kill”: Religion or delusion? San Diego Law Rev. 2001;38:973–1050. [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners. The PNP’s role in supporting infant and family well-being during the first year of life: Position statement. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:19A–20A. doi: 10.1067/mph.2003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Collaborating Center for Mental Health. Antenatal and postnatal mental health: The NICE guideline on clinical management and service guidance. The British Psychological Society and the Royal College of Psychiatrists; London: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius. U.S: 2012. [Accessed 29 March 2013]. p. 567. http://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/11pdf/11-393c3a2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Nau ML, McNiel DE, Binder RL. Postpartum psychosis and the courts. J Am Acad Psychiat Law. 2012;40:318–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, McCabe JE. Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;19:379–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson AL, Kemper KJ, Kellecher KJ, Hammond CS, Zuckerman BS, Dietrich AJ. Primary care pediatricians’ roles and perceived responsibilities in the identification and management of maternal depression. Pediatrics. 2002;110:1169–1176. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons v. Alabama, 81 Ala. 577, 2 So 854 (1887)

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. Sec. 2952 (a), (b), (c); Sec. 2713. (2010)

- Perinatal Depression Awareness Month, California Assembly Concurrent Resolution 105 (2009–2010)

- Perinatal Mental Health Disorders Prevention and Treatment Act, Sec. 15 405 ILCS 95 (2008)

- Pitt B. “Atypical” depression following childbirth. Br J Psychiatry. 1968;114:1325–1335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.114.516.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postpartum Depression and Education Information, MN. Stat. Sec. 145.906 (2010, 2012)

- Postpartum Depression – Public Information and Communication Outreach Campaign, WA. Rev. Code Title 43 State Government - Executive - Sec. 43.121.160 (2009)

- Relating to Information Provided to Parents of Newborn Children, TX. Health and Safety Code Ann., Title 2, Sec. 161, 501, 502 (2005)

- Relating to Perinatal Mental Health and Declaring an Emergency, OR. Laws 75th HS 2666 (2011)

- Holzman GB, Schulkin J. Treatment of depression by obstetrician-gynecologists: A survey study. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:296–300. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00255-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre LS, Brock RL, O’Hara MW, Gorman LL, Engeldinger J. Disseminating perinatal depression screening as a public health initiative: A train-the-trainer approach. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:814–821. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0644-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segre LS, O’Hara MW. The status of postpartum depression screening in the United States. In: Henshaw C, Elliott SA, editors. Screening for perinatal depression. Jessica Kinglsey; London: 2005. pp. 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli MG. Maternal infanticide associated with mental illness: Prevention and promise of saved lives. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1548–1557. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli MG. Infanticide: Contrasting views. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00737-005-0067-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli MG, editor. Infanticide: Psychosocial and legal perspectives on mothers who kill. American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- State v. Yates, Harris County, Texas, Trial Court Case No. 88025 and 88359 Houston 1st Dist (2002)

- Uniform Maternal Screening Act, WV. Code, Chapter 16, Public Health, Article 4E (2009)

- United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Legal Law Digest. [Accessed 1 April 2013];The insanity defense among the states. 2013 http://lawdigest.uslegal.com/criminal-laws/insanity-defense/7204.

- Wisner KL, Logsdon MC, Shanahan BR. Web-based education for postpartum depression: Conceptual development and impact. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11:377–385. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yawn B, Dietrich AJ, Wollan P, Betram S, Graham D, Huff J, et al. TRIPPD: A practice-based network effectiveness study of postpartum depression screening and management. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:320–329. doi: 10.1370/afm.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Lin H, Howell HB, Shao L, Rosencheck RA. Depression screening of perinatal women: An evaluation of the healthy start depression initiative. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:322–328. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]