Abstract

The goals of this study were: (a) to examine authoritative parenting style among Chinese immigrant mothers of young children, (b) to test the mediational mechanism between authoritative parenting style and children’s outcomes; and (c) to evaluate 3 predictors of authoritative parenting style (psychological well-being, perceived support in the parenting role, parenting stress). Participants included 85 Chinese immigrant mothers and their preschool children. Mothers reported on their parenting style, psychological well-being, perceived parenting support and stress, and children’s hyperactivity/attention. Teacher ratings of child adjustment were also obtained. Results revealed that Chinese immigrant mothers of preschoolers strongly endorsed the authoritative parenting style. Moreover, authoritative parenting predicted increased children’s behavioral/attention regulation abilities (lower hyperactivity/inattention), which then predicted decreased teacher rated child difficulties. Finally, mothers with greater psychological well-being or parenting support engaged in more authoritative parenting, but only under conditions of low parenting stress. Neither well-being nor parenting support predicted authoritative parenting when parenting hassles were high. Findings were discussed in light of cultural- and immigration-related issues facing immigrant Chinese mothers of young children.

Keywords: parenting, Chinese immigrants, social development

Asians are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004), growing by 48% (from 6.9 million to 10.2 million) compared to an increase of 13.2% for the total U.S. population between 1990 and 2000. Chinese individuals comprise the largest Asian ethnic group (Barnes & Bennett, 2002) and may be represented by people from three different geographic designations, including the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C.), Hong Kong, and Taiwan (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Malone, Baluja, Constanzo & Davis, 2003).

Despite their apparent success in the academic realm, the psychosocial adjustment of Chinese American children and youth is less clear. Research on Chinese American adolescents indicate that some of these adolescents may experience greater psychological and social emotional difficulties, including depression, suicidal risk, and anxiety than their European American counterparts (e.g., Stewart, Rao, & Bond, 1998; Sue, Mak, & Sue, 1998; Zhou, Peverly, Xin, Huang, & Wang, 2003). For instance, Zhou et al. found that first-generation Chinese immigrant adolescents reported more negative attitudes toward teachers and social stress than European American and Mainland Chinese students and had more negative perceptions of the school environment than students in Mainland China, likely due to their immigration related stress. These adolescents also reported feeling fear, anger, and frustration at being bullied frequently in school that could be related to their negative perceptions of school and teachers. Moreover, Chinese American adolescents from urban schools in New York City had the most discrimination from peers among ethnic groups (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006) that can further exacerbate their emotional and behavioral adjustment (Huang, 1997).

In contrast, with regard to younger second-generation Chinese American children with higher educated parents, Huntsinger, Jose, and Larson (1998) found no significant differences between Chinese American school-aged children and their European American peers on teacher-rated peer acceptance, and withdrawn and social behavioral problems. Chinese American children were rated lower on anxious and depressive symptoms than their European American counterparts. More interesting, Chinese American parents rated their children as higher on social problems than European American parents.

However, much more information is needed regarding the socialization of young Chinese immigrant children and factors that are related to their adjustment (Cheah & Li, in press). Although research comparing Mainland Chinese and European American parenting regarding social development of young children indicates clear cultural differences (e.g., Chang, Schwartz, Dodge, & McBride-Chang, 2003; Cheah & Rubin, 2003, 2004), there is a lack of developmental research on the socialization of the social development of young children of Chinese immigrants in the United States, particularly with regard to examining potential mechanisms involved. The present study examined Chinese immigrant children’s emotional and behavioral difficulties in the preschool or daycare setting as rated by their teachers. Moreover, we examined the role of authoritative parenting in children’s functioning. The preschool period is an ideal developmental period to examine the influence of parenting on children’s development as this is a heightened, intensive, and self-conscious period of parental socialization (Olson, Kashiwagi, & Crystal, 2001). This period is also when young children begin to be in the frequent company of peers. Moreover, the early examination of developmental and socialization processes is essential for potential early intervention.

Thus, the present study had three main goals. The first goal was to examine if authoritative parenting style was endorsed by Chinese immigrant mothers of young children. The second goal was to determine if authoritative parenting style was related to fewer behavioral problems in the preschool/daycare setting among immigrant Chinese children, similar to previous research on European American children. Under the assumption that authoritative parenting would predict child outcomes, we attempted to determine the mediational mechanism between authoritative parenting style and children’s outcomes. Finally, the third goal was to evaluate the role of maternal psychological well-being, perceived support in the parenting role, parenting stress, and their interactions in predicting authoritative parenting.

Authoritative Parenting in Chinese Culture

In individualistic contexts, Baumrind’s (1971) authoritative parenting style (warmth/acceptance, reasoning oriented regulation, and autonomy granting) has been found to be associated with children’s prosocial engagement, cooperation, and moral concern for others’ interests, whereas authoritarian parenting (physical coercion, verbal hostility, and nonreasoning oriented regulation) is associated with children’s aggressive behaviors and adjustment problems (Lamborn, Mounts, Steinberg, & Dornbusch, 1991; Russell, Hart, Robinson, & Olsen, 2003).

Chinese parents in the Mainland China as well as in the United States have been found to be more directive in their parenting and downplay the expression of warmth (i.e., authoritarian), in line with traditional Confucian beliefs in emotional reservedness (Chao, 1994; Kelley & Tseng, 1992; Wu et al., 2002). However, the significance of authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles for children’s social and cognitive functioning in Chinese culture has been questioned (e.g., Chao, 1994, 2001) due to its argued inability to capture important features of Chinese child rearing (e.g., training and governing). With regard to authoritative parenting that is the focus of the present study, Chao and Tseng (2002) asserted that “the beneficial effects of authoritative parenting do not seem to be found among families of Chinese descent, but they are found among families of European descent” (p. 86).

Alternately, other researchers believe that the pattern of the “within-culture” associations between the parenting dimensions and child adjustment may be similar to what is proposed in Baumrind’s (1971) work discussed previously (see Sorkhabi, 2005, for a thorough review). Moreover, Chang and his colleagues (Chang, Lansford, Schwartz, & Farver, 2004) suggested that the social context of Chinese living is Westernized, such that the function of care-giving dimensions of warmth, empathy, and support for Chinese children and adolescents may be more similar to that found among European American children and adolescents than previously thought. Similarly, X. Chen, Dong, and Zhou (1997) found that authoritative parenting was positively associated with Mainland Chinese children’s social competence, peer acceptance, school achievement, and distinguished studentship, and was negatively related to social difficulties. Nevertheless, whether these parenting styles are predictive of young Chinese immigrant children’s social adjustment outcomes in the United States is largely unknown.

Research on this issue would provide valuable information about the applicability of Baumrind’s (1971) system concerning parenting patterns in different cultural contexts. Moreover, findings concerning the relations between authoritative parenting style and child outcomes would be helpful for professionals and parents working with immigrant families to understand the developmental origins of adaptive and maladaptive child functioning. Examining these mechanisms early on can inform effective familybased and culturally-relevant prevention and intervention programs that may offset potential trajectories of maladjustment.

The present study’s first goal was to assess authoritative parenting style in Chinese immigrant mothers of young children. We predicted that the present sample of Chinese immigrant mothers of young children would engage in high levels of authoritative parenting for several reasons. First, Jose, Huntsinger, Huntsinger, & Liaw (2000) observed that Chinese American parents displayed authoritative parenting style during play, combining high levels of warmth and firm control with their preschoolers. Second, our sample of mothers was quite highly educated and level of education has been found to be associated with greater endorsement of authoritative parenting style in Chinese families as well as other cultural groups (e.g., X. Chen et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2005). Finally, the children in the present sample were under 6 years of age. In Chinese society, the preschool child is treated with leniency and indulgence. A young child (under 6 years old) is considered to be incapable of understanding things and therefore not punished for misbehavior (Ho, 1989). Instead, a lot of direction and guidance is given regarding the appropriate behavior (Cheah & Rubin, 2003, 2004). When the child reaches the “age of understanding,” at approximately 6 years of age, there is a change in parental attitudes and practices with the imposition of stricter discipline.

As the second goal, we were also interested in assessing the association between authoritative parenting style and immigrant Chinese children’s outcomes, and expected that this parenting style would be associated with fewer difficulties in children, similar to their European American peers. Authoritative parenting is distinguished by reciprocity, mutual understanding, and flexibility, which enable the parent to effectively account for, coordinate, and balance communal needs or collective goals of society and family with the capabilities, needs, and goals of the child (Sorkhabi, 2005). Thus, the consistent and differentiated use of autonomy granting, supportive but firm control, and nurturance of authoritative parents was expected to be related to fewer difficulties in Chinese immigrant children’s behavioral adaption in the preschool or daycare setting.

We were specifically interested in a mediation model that examines the mechanism through which authoritative parenting is related to child outcomes. The potential mediating role of the child’s behavioral and attentional self-regulation was examined. Parents who are accepting of their children, grant them more autonomy, and implement higher levels of behavioral control in terms of rules and guidelines, have children who display higher levels of behavioral selfregulation, maturity, identity, and work orientation (Reitman & Gross 1997). Moreover, authoritative mothers tend to make age-appropriate demands within a supportive context that promotes early self-regulation, leading to fewer child behavior problems (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). Although the cross-sectional nature of our data does not allow us to conclude the direction of the associations among these variables, in our conceptual mediation model, we proposed that mothers’ authoritative parenting style would be positively correlated with children’s ability to regulate and modulate their behaviors and attention, which in turn would be associated with fewer teacher-rated emotional and behavioral difficulties.

Predictors of Authoritative Parenting

Given the assumption that authoritative parenting would indeed be predictive of fewer behavioral difficulties in Chinese immigrant children, the third goal of the present study was to examine the predictors of authoritative parenting in immigrant Chinese mothers. Similar to with our mediation model, the direction of causation cannot be inferred. However, we focused on personal (psychological well-being), relational (parenting support), and contextual (parenting stress) factors that were thought to either predict better (psychological adjustment and parenting support) or worse (parenting stress) maternal ability to engage in authoritative parenting.

Psychological adjustment

Research suggests parents who are most sensitive, warm, and nurturing with their infants are those with positive psychological well-being (Belsky, 1984). Most researchers focus on the role of poor psychological health, with fewer researchers examining psychological well-being in terms of positive mental health attributes (Diener, 1984), including indicators such as life satisfaction and mastery of life. In this study, a composite of psychological well-being comprised of autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance was assessed.

As a result of the challenges associated with immigration, psychological well-being is especially important for immigrant Chinese mothers (Schnittker, 2002). Mothers who are able to adjust well to the new cultural context (i.e. reduce stressors of immigrating), report greater psychological well-being (Phinney, Horenczyk, Liebkind, & Vedder, 2001). In turn, mothers who report greater well-being may have greater psychological, cognitive, and emotional functioning and subsequently parent more effectively (Vondra, Sysko, & Belsky, 2005). Mothers with higher self-acceptance, a more positive outlook on life, and greater sense of mastery over the environment are more likely to demonstrate sensitive parenting practices and empathy toward their children and less likely to prefer punitive punishment strategies (Meyers & Battistoni, 2003). Thus, we expected that Chinese immigrant mothers with higher levels of psychological well-being would report engaging in a more authoritative parenting style.

Parenting support

Xu et al. (2005) reported that Mainland Chinese mothers’ perceived social support was positively associated with an authoritative parenting style. Previous studies show that social support available for mothers is associated with their parenting style by making mothers feel less isolated and overwhelmed, and more satisfied with their children (Crnic & Greenberg, 1987; Simons, Lorenz, Wu, & Conger, 1993). Such support also allows mothers to have more emotional and psychological resources available to handle their children effectively and thus become more competent in parenting (S. Cohen & Wills, 1985; McLoyd, 1990).

Social support plays an important role in the adaptation of immigrant families (Kagitcibasi, 2006; Salaff & Greve, 2004; Short & Johnston, 1997). In the present study, we focused on support that mothers may receive with regard to the parenting role from three sources: their spouses, mothers, and fathers. Given that these mothers may have less access to their larger network of social support as an immigrant, perceived support from these key individuals is likely to be highly important. Support related to the parenting role was expected to be most related to mothers’ ability engage in more inductive reasoning, provide greater warmth and support, and create opportunities for child autonomy. Thus, we predicted that mothers who reported receiving greater amounts of parenting support would be more likely to engage in authoritative parenting.

Parenting stress

Immigrant Chinese mothers’ perceived parenting stress may also play a significant role in their parenting style. High levels of parenting stress have been found to be associated with more punitive behaviors in Mainland Chinese mothers (Xu et al., 2005). In addition, parents who experience high levels of stress are less able to respond to their young children warmly and sensitively because the parent is preoccupied with other stressors and has fewer resources available for parenting (Gelfand, Teti, & Fox, 1992). Mothers who experience high levels of parenting stress report more negative emotions and frustration in their roles as parents than those who experienced lower levels of stress (Bugental, Blue, & Lewis, 1990; Dix, 1991) that may lead to a parenting style characterized by the use of lower levels of inductive reasoning, warmth, and provision of opportunities for child autonomy. Related, Chinese immigrant mothers who reported less stress also reported fewer child adjustment problems (Short & Johnston, 1997). In this study, we expected that high levels of daily hassles from parenting tasks and challenging child behavior would interfere with mothers’ ability to engage in authoritative parenting. We also aimed to examine the interactions between these variables in predicting parenting.

Method

Participants

Eighty-five mothers (M = 37.47 years, SD = 4.01) of preschool-aged children (M = 4.23 years, SD = .82) participated in the present study. All children were from twoparent families of well-educated, middle-class socioeconomic status. Mothers were originally from Mainland China (69.1%), Taiwan (23.5%), and Hong Kong (7.4%). On average, mothers had been in the United States for 10.52 years (SD = 7.52), ranging from 3 months to 45.25 years. Most mothers were highly educated, with 2.4% of mothers having secondary school education, 31% with a university degree, and 63% with a graduate or professional degree.

The mothers reported having moved to the United States for a variety of reasons (35% for education, 33.5% for marriage/came with spouse, 10% for reunion with family in Unites States, 10% for better living opportunities, 7.5% for a job, and 2.5% for political reasons). Most mothers had more than one child (43.8% had one child, 41.3% had two children, 13.8% had three children, and 1.3% had four children). The majority of mothers reported being Christian (57%), whereas more than a third (39%) reported no religious affiliation, and 2.4% reported being Buddhist. Eightysix percent of the preschoolers were born in the United States (second generation) and 14% were born in Asia (first generation).

Procedure

Families were recruited from churches, community centers, preschools, and daycare centers throughout Maryland. With the permission of the directors of these centers, announcements were made to the parents regarding the study and parents were invited to participate if they were interested. Most of these families resided in suburban areas. Data collection was conducted during a visit to each family’s home by two trained research assistants who were fluent in the dialect used within the home (Mandarin or Cantonese). Written consent was obtained from the mothers. The mothers completed the questionnaires in a language or dialect of her preference, (i.e. simplified Chinese, traditional Chinese, or English). With parental permission, the research assistant contacted the child’s teacher to administer the teacher ratings over the telephone within 1 week of the home visit. The institutional review board of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County approved the procedures used for obtaining informed consent and protecting the rights and welfare of the participants.

Measures

Most of the measures were available in Chinese. Those that were originally in English were translated to Chinese (both simplified and traditional forms), and then backtranslated to English. Next, the two English versions were compared to ensure that the original meaning of the measures was maintained. All discrepancies were discussed and consensus was obtained among all the bilingual translators.

The Family Description Measure

The Family Description Measure (Bornstein, 1991) obtains detailed demographic and descriptive information about the child, mother, father, the child’s environment and routine, and parents’ age, employment, education, and nationality. We also obtained other information relevant to our immigrant families, such as the mothers’ country of origin, length of time in the United States, and reasons for moving to the United States.

SDQ–M

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire–Mother (SDQ–M; Goodman, 1997) was used to assess mothers’ perspective of children’s behaviors. The SDQ is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire about 3 to 16 year olds. The slightly modified informant-rated version specifically for parents of 3 and 4 year olds was used for the present sample. We focused on the maternal report of hyperactivity/inattention subscale as an indicator of children’s behavioral and attentional regulation. Mothers rated their children’s behaviors on a scale of 1 (not true) to 3 (certainly true). A sample item includes, “Good attention span, sees work through to the end.” The SDQ’s internal reliability has been established across various cultures, and a version in Chinese was already available (see www.sdqinfor.com for a list of supporting validity and reliability citations). In the present study, the alpha coefficient was α = .74 for mother-report of hyperactivity/inattention.

PSDQ

A modified version of the Parenting Styles Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Robinson, Mandleco, Olsen, & Hart, 2001; Wu et al., 2002) was administered to the mothers. This 41-item measure assesses the mothers’ perspective on their parenting role, endorsement of the authoritative and authoritarian parenting style as well as five parenting practices emphasized in China. Specific to the proposed study, the authoritative parenting pattern is comprised of three stylistic dimensions: (a) warmth (7 items; e.g., “I gave praise when my child is good”); (b) reasoning induction (4 items; e.g., “I talk it over and reason with my child when he/she misbehaves”); and (c) autonomy granting (4 items; e.g., “I allow my child to give input into family rules”). Mothers rated the frequency of their parenting behaviors described in each item on a 5-point scale: 1 (never), 2 (once in a while), 3 (about half of the time), 4 (very often), to 5 (always).”

Items representing the three authoritative construct dimensions have been identified in the Chinese and American samples with a series of multisample confirmatory factor analyses (MCFA; Wu et al., 2002). The authoritative parenting constructs have been shown to be cross-culturally valid for both Chinese and American samples. Moreover, intercorrelations among warmth, reasoning induction, and autonomy were .80, .82, and .85, respectively, for the Chinese sample. Cronbach’s alphas for parents’ self-reports ranged from .71 to .86, with a mean of .81 (Russell et al., 2003). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were α = .79 for warmth, α = .70 for reasoning, α = .59 for autonomy granting. All three subscales were averaged to create an overall measure of authoritative parenting that was used in all subsequent analyses; the overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was α = .82.

RWBS

The Psychological Well-Being Scale (RWBS; Ryff, 1995) assesses multiple dimensions of parent’s psychological well-being: autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relationships with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance. Mothers responded to each item on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Examples of items on the measure are: (a) autonomy, “In general, I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live”; (b) environmental mastery, “I am quite good at mastering the many responsibilities of my daily life”; (c) personal growth, “For me, life has been a continuous process of learning, changing, and growth”; (d) positive relationships with others, “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others”; (e) purpose in life, “Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them”; and (f) self acceptance, “I have confidence in my own opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus” (Ryff, 1989).

This measure has demonstrated high internal consistency in previous research, and good reliability estimates were obtained for immigrant samples, ranging from .77 to .79 (e.g., Downie, Chua, Koestner, Barrios, Rip, & M’Birkou, 2007). An overall well-being composite was created by summing all of the subscales, and Cronbach’s alpha for this overall composite was .77 for the present sample.

Parenting support

Parenting support was assessed by using three items derived from the Bornstein (1991) demographic measure regarding the amount of support specific to the parenting role that mothers received from their husband, their own mother, and their own father (e.g., “How supportive is your spouse in your role as a parent?”). Mothers responded to each item on a scale of 0 (not supportive) to 6 (consistently, strongly supportive). These items were averaged to create a composite measure of parenting support. The alpha coefficient for this scale in the present study was α = .83.

The Parenting Daily Hassles

The Parenting Daily Hassles (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990) measure captures the stressors that parents face as a result of parenting and in their interactions with their children. This 20-item questionnaire is designed to measure the frequency of hassles mothers experience on a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (constantly) and the intensity of these hassles, on a scale of 1 (no hassle) to 5 (big hassle) over the past few weeks. Some events include making child care arrangements, cleaning messes, managing the child’s behavior in public, having their daily tasks disrupted, and being resisted at bedtime. The reliabilities of each subscale sum were high, such that the internal consistency of the frequency scale was .81 and was .90 for the intensity scale. In addition, the subscales of the Parenting Daily Hassles measure have been demonstrated to be highly correlated, r = .78 (Crnic & Greenberg, 1990) and was therefore summed in the present study. In a sample of Chinese parents of preschoolers, F.-M. Chen and Luster (2002) reported an overall internal consistency of the measure of α = .86. The alpha coefficient for the overall scale in the present study was α = .88.

Teacher Ratings of Children’s Outcomes

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire–Teacher (SDQ–T; Goodman, 1997) was used to assess teacher’s perspective of children’s behaviors. The SDQ is a brief behavioral screening questionnaire about 3 to 16 year olds. The slightly modified informant-rated version specifically for teachers of 3 and 4 year olds was used for the present sample. Five factors comprise this measure: emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationships problems, and prosocial behavior. We focused on teachers’ report of total difficulties as an indicator of child outcomes, which was a composite of all five factors. Teachers rated items on a scale ranging from 1 (not true) to 3 (certainly true). Sample items include: (a) emotional symptoms, “Often unhappy, depressed or tearful”; (b) conduct problems, “loses temper”; (c) peer problems, “Rather solitary, tends to play alone”;” and (d) hyperactivity/Inattention, “Can stop and think things out before acting (reversed).” The SDQ’s internal reliability has been established across various cultures, and a version in Chinese was already available (see www.sdqinfor.com for a list of supporting validity and reliability citations). In the present study, the alpha coefficient was α = .63 for teacher-report of total difficulties and α = .74 for mother-report of hyperactivity/ inattention.

Results

None of the potential covariates, specifically child’s age, mother’s age, mother’s length of time in the United States, and child’s generation status was significantly related to authoritative parenting style or child outcomes and was not included in further analyses. There were also no child sex differences on any of the variables of interest.

Authoritative Parenting Style

In support of our first hypothesis, mothers endorsed high levels of warmth (M = 4.30, SD = .47), reasoning induction (M = 4.12, SD = .58), autonomy granting (M = 3.69, SD = .62), and overall authoritative parenting style (M = 4.04, SD = .48), with ratings of 4 indicating that mothers engaged in these behaviors very often. There were significant correlations between (a) warmth and reasoning induction, r = .68,p < .001, (b) warmth and autonomy granting, r = .56, p < .001, and (c) reasoning induction and autonomy granting, r = .62, p < .001, indicating that the three authoritative parenting dimensions were highly interrelated. Thus, the overall authoritative parenting style variable was used for all further analyses.

Mediating Role of Authoritative Parenting Style

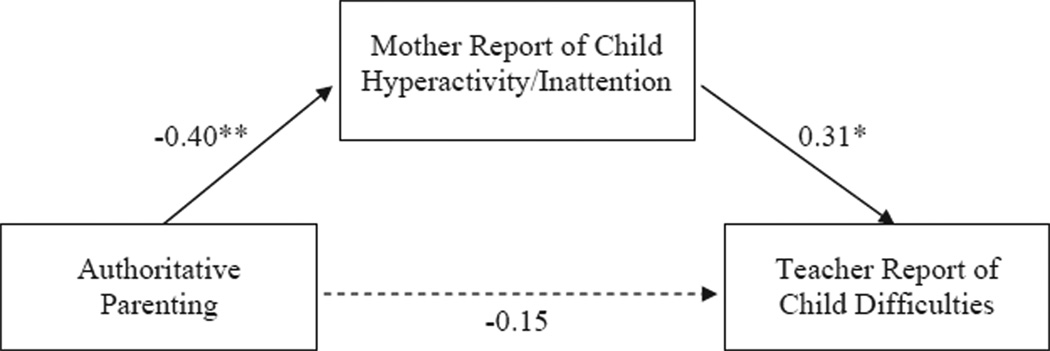

A series of mediation regression analyses (Baron & Kenny, 1986) was conducted to examine the mediating role of the child’s behavioral and attentional self-regulation, as indexed by the maternal ratings of hyperactivity/inattention on the SDQ, in the relation between authoritative parenting style and teacher rating of the child’s overall difficulties.

Results revealed that authoritative parenting style negatively predicted children’s difficulties, β = −.61, t(71) = −2.28, p < .05, f2 = 0.07 and negatively predicted children’s hyperactivity/inattention, β = −0.40, t(81) = −3.88, p < .001, f2 = 0.19. Moreover, children’s hyperactivity/ inattention positively predicted children’s difficulties, β = 0.31, t(69) = 2.62, p < .05, f2 = 0.10. When controlling for children’s hyperactivity/inattention in testing for mediation, the effect of authoritative parenting style on children’s difficulties decreased and became nonsignificant, β = −0.15, t(69) = −1.31, p > .05. Sobel test (1982) indicated a significant full mediation effect of authoritative parenting style on teacher report of children’s difficulties through children’s hyperactivity/inattention, t(69) = −2.17, p < .5, f2 = 0.07. Thus, authoritative parenting predicted increased behavioral and attention regulation abilities (lower hyperactivity/inattention), which in turn, was associated with decreased children’s difficulties (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A full mediation effect of authoritative parenting style on teacher report of children’s difficulties through mother report of children’s hyperactivity/inattention.

Predictors of Authoritative Parenting

A hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the predictors of authoritative parenting (i.e., psychological well-being, parenting support, and parenting stress) and their interactions. To facilitate the interpretation of interaction terms and to minimize nonessential multicolinearity, all variables, with the exception of the outcome variable, were centered at their means (see Table 1 for results; J. Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Table 1.

Hierarchical Regression of Multiple Predictors of Authoritative Parenting Style

| Variable | β | B | SE | R2 | ΔR2 | F change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .15 | .15 | 4.35* | |||

| Psychological well-being | 0.20 | 0.10 | .05 | |||

| Parenting support | 0.14 | 0.07 | .05 | |||

| Parenting stress | −0.23* | −0.011* | .05 | |||

| Step 2 | .29 | .14 | 4.85* | |||

| Psychological well-being | 0.19 | 0.10 | .05 | |||

| Parenting support | 0.21* | 0.10* | .05 | |||

| Parenting stress | −0.20* | −0.10* | .05 | |||

| Well-Being × Parenting Support | −0.15 | −0.07 | .06 | |||

| Well-Being × Parenting Stress | −0.36** | −0.18** | .06 | |||

| Parenting Support × Parenting Stress | −0.28** | −0.14** | .05 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

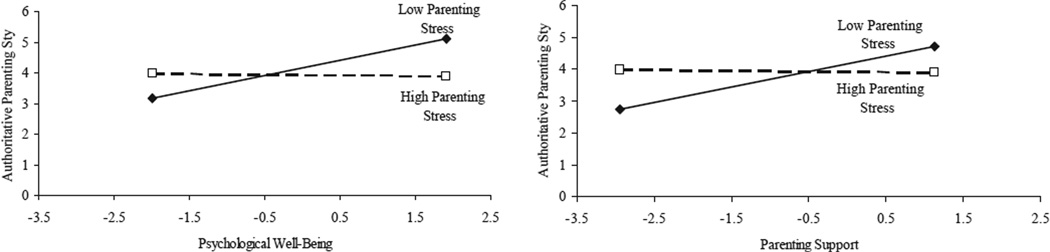

There was a significant psychological well-being and parenting stress interaction in predicting authoritative parenting style, −0.36, t(73) = −3.11,p < .01,f2 = 0.13. To further examine how parenting stress moderated the association between psychological well-being and authoritative parenting, simple slope tests were conducted at the values of one standard deviation above and below the mean (Aiken & West, 1991; J. Cohen et al., 2003). Results revealed showed that at a low level of parenting stress, psychological well-being was positively associated with authoritative parenting style, β = 0.50, t(78) = 3.35, p < .01, f2 = 0.14. However, at a high level of parenting stress, psychological well-being was not significantly associated with authoritative parenting style (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maternal psychological well-being and parenting stress interaction in predicting authoritative parenting style and parenting support and parenting stress interaction in predicting authoritative parenting style. The mean score of the overall authoritative parenting style was 4.04 out of 5.00.

There was also a significant parenting support and parenting stress interaction in predicting authoritative parenting style, β = −0.28, t(73) = −2.76, p < .01, f2 = 0.10. Here, we were interested in examining how parenting stress moderated the association between parenting support and authoritative parenting. Simple slope tests were conducted and indicated that at a low level of parenting stress, parenting support was positively associated with authoritative parenting style, β = 0.45, t(77) = 2.75, p < .01, f2 = 0.10. However, at a high level of parenting stress, parenting support was not significantly associated with authoritative parenting style (see Figure 2).

Discussion

The present study was designed to examine the role of authoritative parenting style among Chinese immigrant mothers of children between the ages of 3 and 5 years old. In addition, we were interested in the mediating mechanism between parenting style and child outcomes. Finally, we explored the multivariate factors that predicted authoritative parenting.

Authoritative Parenting

As we hypothesized, the Chinese immigrant mothers in our sample highly endorsed the use of authoritative parenting style. As predicted, mothers endorsed items indicating that they gave comfort to their children when they were upset, having warm and intimate times with them, explaining the consequences for their behavior, or taking their desire into account before asking them to do something. These findings are consistent with those of Chao (1995) in which loving the child and fostering a good relationship was the most frequently mentioned theme among immigrant Chinese American mothers of preschool-aged children. Wang and Phinney (1998) also found that immigrant Chinese mothers of preschoolers sought to provide opportunity and encouragement for their children to develop selfreliance and independence more so than Anglo American mothers. Moreover, Jose, Huntsinger, Huntsinger, and Liaw (2000) reported that Chinese American mothers engaged in high levels of warmth and firm control. Our finding contributes to current research on the endorsement and adaptability of authoritative parenting in Chinese families.

Moreover, according to Ho (1989), Chinese parents tend to be lenient, warm, and affectionate toward infants and very young children until they reach the “age of understanding,” at which point strict discipline was imposed. This indulgence is based on the belief that young children (below 6 years of age) are incapable of understanding. Given the Confucian belief in guidance and training that informs Chinese parenting (Ho, 1996), parents may believe that wrongdoing should be tolerated, and children should be guided through their mistakes. Future longitudinal research is needed to understand changes in parental expectations of children’s capabilities and consequent parenting behaviors across developmental stages.

Another possible explanation for the endorsement of authoritative parenting in the present study concerns the high educational level of the mothers in our immigrant Chinese sample. In research by X. Chen et al. (2000) and Xu et al. (2005), the education levels of Chinese mothers were found to be positively associated with authoritative attitudes and more reasoning strategies. This difference may be because mothers with high educational levels are more likely to be exposed to and understand the importance of inductive parenting for social and cognitive development in children. The majority of the mothers in the present study had college degrees or higher (i.e., graduate or professional degrees). Moreover, the families in the present sample reside in neighborhoods with small concentrations of other Chinese families (co-ethnics). Thus, mothers might be more inclined to engage in parenting practices that are encouraged in the larger U.S. majority. Further research including a more diverse sample in terms of educational levels and across communities of immigrants with different densities of coethnics is needed.

Child Outcomes and Authoritative Parenting

In addition to examining mean levels of authoritative parenting among Chinese immigrant mothers, we sought to further clarify the adaptational meanings of authoritative parenting style in this group. In other words, how is this parenting style relevant to the social functioning of Chinese American children?

Consistent with our expectations and in support of a growing body of research (e.g., Chang et al., 2003; 2004; X. Chen et al., 1997), authoritative parenting was associated negatively with children’s adjustment problems in the Chinese culture. Moreover, the association between parenting style on children’s behavioral adjustment was mediated by their behavioral and attentional regulation abilities. Mediators explain through what mechanisms parenting style is related to child outcomes. Highly authoritative mothers emphasize demands for action and future-oriented controls within a harmonious social context of early self-regulation, which may lead to fewer child behavior problems (Kuczynski & Kochanska, 1995). In addition, the authoritative model of discipline that emphasizes the use of reasoning and induction directs children’s attention to the consequences of their misdemeanors on others.

Children’s internalization of family and social rules about regulating behavior is more likely to be fostered (Grusec & Goodnow, 1994; Hoffman, 2000). Moreover, Mainland Chinese authoritative parents tend to encourage their child’s autonomy, and thus provide opportunities for their child to develop self-regulatory abilities (Zhou, Eisenberg, Wang, & Reiser, 2004). These children’s abilities to regulate behavior and attention was related to lower levels of children’s difficulties including emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity, and peer problems, as rated by their preschool or daycare teachers.

Predictors of Authoritative Parenting

Given the contributions of authoritative parenting to fewer child difficulties, our final goal was to examine the predictors of authoritative parenting. Specifically, we focused on two factors that were thought to be particularly significant for immigrant mothers: their psychological wellbeing and perceived parenting support. We were also interested in examining how parenting stress moderated the association between these predictors and the mothers’ ability to engage in authoritative parenting. As predicted, we found that mothers who reported higher psychological well-being were more likely to engage in authoritative parenting, but only under conditions of low parenting stress from daily hassles. When parenting hassles were perceived to be high, mothers may be less able to utilize their psychological resources to engage in warm and responsive parenting, inductive reasoning, and support their child’s autonomy development.

The same pattern of findings was revealed with regard to the relation between parenting support and authoritative parenting. As expected, mothers who reported receiving a lot of support with regard to their role as a parent from their spouse and own parents were more likely to engage in reasoned guidance with their children, but only under conditions of low parenting stress. In contrast, for mothers who reported being hassled by events including making childcare arrangements, cleaning messes, managing the child’s behavior in public, having their daily tasks disrupted, and being resisted at bedtime, parenting support was no longer associated with their endorsement of authoritative parenting.

The cumulative impact over time of these daily hassles that are specifically associated with parenting appeared to be particularly important for Chinese immigrant mothers in terms of interfering with their ability to engage in authoritative parenting. Support can come in many forms, including emotional support and satisfaction, as well as instrumental assistance (e.g., childcare, help with household maintenance, financial assistance, and community referrals; MacPhee, Fritz, & Miller-Heyl, 1996). Although some of these mothers may perceive receiving high amounts of support from their spouse and own parents with their parenting role, they may be referring to emotional support instead of instrumental assistance with daily hassles arising from parenting tasks and managing child behaviors.

For immigrant mothers, parenting support that is more related to instrumental assistance might be more beneficial. MacPhee et al. (1996) found that informal support from kin and friends was more likely to be emotional than instrumental, even though childcare was strongly related to satisfaction with support. To support this idea, we found that only 16% of the children in our sample had grandparents residing in their household. Thus, regardless of how much perceived support mothers reported receiving with the parenting role from their parents, these mothers might be less likely to receive functional parenting assistance from the sources of support that were measured in the present study.

Future research needs to more carefully examine the specific types of parenting stressors that may create unique problems for immigrant mothers, for instance, parents’ language barrier, lack of knowledge about the schooling process or ways to attain assistance with childcare. Such information would aid community organizations to develop ways to address these stressors by providing the appropriate amount and type of support. The structure and function of the larger network should also be examined in relation to parenting style, stress, support, and their psychological well-being.

Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, the generalizability of the results of the present study is constrained due to the lack of variability in the educational level of the mothers. Second, the high rate of authoritative parenting that was identified in the present study presents only one aspect of the parenting style of these Chinese immigrant mothers. As noted in the Introduction, indigenous forms of Chinese parenting have been identified by researchers (e.g., Chao, 1994; Lieber, Fung, & Leung, 2006; Stewart et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1996) and are in further need of investigation to fully understand the complex parenting of Chinese mothers. Moreover, although the overall authoritative parenting style was examined in this present study, the specific subscales of parenting (i.e. warmth, regulation, and autonomy support) should be further examined with regard to specific predictors and child outcomes.

More important, these results are correlational in nature. Therefore, although we proposed that authoritative parenting would promote regulatory abilities in children, the direction of causation in these analyses cannot be inferred. It is easy to imagine that children who posses good emotion and behavioral regulatory skills would be more easily met with warm and autonomy promoting parenting. Children who are viewed by their teacher as experiencing fewer problems in the classroom may engender authoritative parenting from their parents. Likewise, with regard to the predictors of authoritative parenting that were examined, parents who engage in such a style might seek out more support from their surroundings and consequently be more psychologically well. Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of this study cannot inform the direction of the relations among these variables.

Finally, the mothers’ level of acculturation was also not examined in the present study. Research has shown that level of acculturation is related to psychological well-being, the amount and types of support received, the stresses experienced by immigrants, as well as their parenting styles and practices (Birman, 2006; Phinney et al., 2001; Ying, 1996). Another limitation of the present study is the lack of inclusion of fathers. Recent research has described the importance of understanding the unique contributions of fathers to children’s development (Jose et al., 2000; Sun & Roopnarine, 1996).

Despite these limitations, however, the present study represents a significant step toward understanding the parenting and social development of Chinese American young children. These findings will provide needed information on individual, relational, and contextual factors that predict parenting in Chinese immigrant mothers that may contribute to the behavioral adaptation of their young children. These results can contribute to community planning of services targeted towards the healthy adaptation of immigrant children and their parents.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Foundation for Child Development Young Scholars Program to Charissa S.L. Cheah. We are deeply indebted to the families who have participated and to those who continue to participate in this longitudinal research.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JS, Bennett CE. The Asian population: 2000. Census 2000 Brief. 2002 Retrieved January 7, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01–16.pdf.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Developmental Psychology Monograph. 1971;4(1, Part 2):1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D. Acculturation gap and family adjustment: Findings with Soviet Jewish Refugees in the United States and implications for measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37:568–589. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Approaches to parenting in culture. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Cultural approaches to parenting. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Blue J, Lewis J. Caregiver beliefs and dysphoric affect directed to difficult children. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26:631–638. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Lansford JE, Schwartz D, Farver JM. Marital quality, maternal depressed affect, harsh parenting, and child externalising in Hong Kong Chinese families. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Chinese and European American cultural models of the self reflected in mothers’ childrearing beliefs. Ethos. 1995;23:328–354. [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Extending research on the consequences of parenting style for Chinese Americans and European Americans. Child Development. 2001;72:1832–1843. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Li J. Parenting of young immigrant Chinese children: Challenges facing their social emotional and intellectual development. In: Takanishi R, Grigorenko EL, editors. Immigration, diversity, and education. New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Rubin KH. European American and Mainland Chinese mothers’ socialization beliefs regarding preschoolers’ social skills. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Rubin KH. Comparison of European American and Mainland Chinese Mothers’ responses to aggression and social withdrawal in preschoolers. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28:83–94. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F-M, Luster T. Factors related to parenting practices in Taiwan. Early Child Development and Care. 2002;172:413–430. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Dong Q, Zhou H. Authoritative and Authoritarian parenting practices and social and school performance in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21:855–873. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Liu M, Li B, Cen G, Chen H, Wang L. Maternal authoritative and authoritarian attitudes and motherchild interactions and relationships in urban China. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2000;24:119–126. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, Greenberg M. Maternal stress, social support, and coping: Influences on early mother-child relationship. In: Boukydis C, editor. Research on support for parents and infants in the postnatal period. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1987. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Greenberg MT. Minor parenting stresses with young children. Child Development. 1990;61:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T. The affective organization of parenting: Adaptive and maladaptative processes. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:3–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downie M, Chua SN, Koestner R, Barrios M-F, Rip B, M’Birkou S. The relations of parental autonomy support to cultural internalization and well-being of immigrants and sojourners. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:241–249. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand D, Teti DM, Fox CR. Sources of parenting stress for depressed and nondepressed mothers of infants. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1992;21:262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ. Impact of parental discipline methods on the child’s internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Continuity and variation in Chinese patterns of socialization. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 1989;51:149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ho DYF. Filial piety and its psychological consequences. In: Bond MH, editor. The handbook of Chinese psychology. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press; 1996. pp. 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Social adjustment of Chinese immigrant children in the U.S. educational system. Education and Society. 1997;15:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Huntsinger CS, Jose PE, Larson SL. Do parent practices to encourage academic competence influence the social adjustment of young European American and Chinese American children? Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:747–756. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE, Huntsinger CS, Huntsinger PR, Liaw FR. Parental values and practices relevant to young children’s social development in Taiwan and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2000;31:677–702. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi C. An overview of acculturation and parentchild relationship. In: Bornstein MH, Cote LR, editors. Acculturation and parent-child relationships: Measurement and development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Tseng H. Cultural differences in child rearing: A comparison of immigrant Chinese and Caucasian American mothers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1992;23:444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L, Kochanska G. Function and content of maternal demands: Developmental significance of early demands for competent action. Child Development. 1995;66:616–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamborn SD, Mounts NS, Steinberg L, Dornbusch SM. Patterns of competence and adjustment among adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Development. 1991;62:1049–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber E, Fung H, Leung PW-L. Chinese childrearing beliefs: Key dimensions and contributions to the development of culture-appropriate assessment. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. 2006;9:140–147. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee D, Fritz J, Miller-Heyl J. Ethnic variations in personal social networks and parenting. Child Development. 1996;67:3278–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Malone N, Baluja KF, Costanzo JM, Davis CJ. The foreign-born population: 2000. Census 2000 brief. 2003;2005 Retrieved January 7, 2005, from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-34.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Battistoni J. Proximal and distal correlates of adolescent mothers’ parenting attitudes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24:33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Olson SL, Kashiwagi K, Crystal D. Concepts of adaptive and maladaptive child behavior: A comparison of U.S. and Japanese mothers of preschool-age children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2001;32:43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Liebkind K, Vedder P. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:493–510. [Google Scholar]

- Reitman D, Gross A. The relation of maternal childrearing attitudes to delay of gratification among boys. Child Study Journal. 1997;27:279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson CC, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire (PSDQ) In: Perlmutter BF, Touliatos J, Holden GW, editors. Handbook of family measurement techniques. Vol. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. p. 190. Instruments and index. [Google Scholar]

- Russell A, Hart CH, Robinson CC, Olsen SF. Children’s sociable and aggressive behavior with peers: A comparison of the U.S. and Australian, and contributions of temperament and parenting styles. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2003;27:74–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;57:1069–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD. Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1995;4(4):99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Salaff JW, Greve A. Can Chinese women’s social networks migrate? Women’s Studies International Forum. 2004;27:149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J. Acculturation in context: The self-esteem of Chinese immigrants. Social Psychological Quarterly. 2002;65:56–76. [Google Scholar]

- Short KH, Johnston C. Stress, maternal distress, and children’s adjustment following immigration: The buffering role of social support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:494–503. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lorenz FO, Wu C, Conger RD. Social network and marital support as mediators and moderators of the impact of stress and depression on maternal behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29:368–381. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkhabi N. Applicability of Baumrind’s parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:552–563. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SM, Rao N, Bond MH. Chinese dimensions of parenting: Broadening Western predictors and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology. 1998;33:345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Sue D, Mak WS, Sue DW. Ethnic identity. In: Lee LC, Zane NWS, editors. Handbook of Asian American psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 289–323. [Google Scholar]

- Sun L-C, Roopnarine JL. Mother-infant, father- infant interaction and involvement in childcare and household labor among Taiwanese families. Infant Behavior & Development. 1996;19:121–129. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic and Asian Americans increasing faster than overall population. U.S. Census Bureau News. 2004 Retrieved April 21, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/releases/archives/race/001839.html.

- Vondra J, Sysko HB, Belsky J. Developmental origins of parenting: Personality and relationship factors. In: Luster T, Okagaki L, editors. Parenting: An ecological perspective. 2nd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CH, Phinney JS. Differences in child rearing attitudes between immigrant Chinese mothers and Anglo-American mothers. Early Development & Parenting. 1998;7:181–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Robinson CC, Yang C, Hart CH, Olsen SF, Porter CL, et al. Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:481–491. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Farver JM, Zhang Z, Zeng Q, Yu L, Cai B. Mainland Chinese parenting styles and parent-child interaction. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y. Immigration satisfaction of Chinese Americans: An empirical examination. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Growing up American: The challenge confronting immigrant children and children of immigrants. Annual Review of Sociology. 1997;23:63–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Wang Y, Reiser M. Chinese children’s effortful control and dispositional anger/frustration: Relations to parenting styles and children’s social functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:352–366. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Peverly ST, Xin T, Huang AS, Wang W. School adjustment of first-generation Chinese-American adolescents. Psychology in the Schools. 2003;40:71–84. [Google Scholar]