Abstract

Early life dietary transitions reflect fundamental aspects of primate evolution and are important determinants of health in contemporary human populations1,2. Weaning is critical to developmental and reproductive rates; early weaning can have detrimental health effects but enables shorter inter-birth intervals, which influences population growth3. Uncovering early life dietary history in fossils is hampered by the absence of prospectively-validated biomarkers that are not modified during fossilisation4. Here we show that major dietary shifts in early life manifest as compositional variations in dental tissues. Teeth from human children and captive macaques, with prospectively-recorded diet histories, demonstrate that barium (Ba) distributions accurately reflect dietary transitions from the introduction of mother’s milk and through the weaning process. We also document transitions in a Middle Palaeolithic juvenile Neanderthal, which shows a pattern of exclusive breastfeeding for seven months, followed by seven months of supplementation. After this point, Ba levels in enamel returned to baseline prenatal levels, suggesting an abrupt cessation of breastfeeding at 1.2 years of age. Integration of Ba spatial distributions and histological mapping of tooth formation enables novel studies of the evolution of human life history, dietary ontogeny in wild primates, and human health investigations through accurate reconstructions of breastfeeding history.

Weaning, the dietary transition from breast milk to exclusive solid food intake, concludes several years earlier in modern humans than in other great apes5,6. Cross-cultural studies of nonindustrial societies reveal remarkable variation in weaning practices7. However, among non-human primates, dietary transitions remain understudied8,9. In addition to the paucity of comparative primate data, our understanding of the evolution of human weaning has been limited by difficulties in assessing the precise timing and nature of dietary transitions during infancy3. Dental hard tissues are particularly valuable for reconstructing diet as they contain precise temporal and chemical records of early life4. Teeth begin forming in utero, record birth as the neonatal line, and manifest daily growth lines, which allow chronological ages to be determined at various positions within tooth crowns and roots (Supplementary Figure S1).

We propose that micro-spatial analysis of barium-calcium ratios (Ba/Ca) in dental tissues represents a powerful approach to assess dietary transitions. While prenatal Ba transfer is restricted by the placenta, marked enrichment occurs immediately after birth from mother’s milk or infant formulas, which contain higher Ba levels than umbilical cord sera10. In response to these variations in dietary Ba exposure, Ba/Ca in enamel and dentine should increase at birth, remain elevated for the duration of exclusive breastfeeding and rise further with introduction of infant formula. Circulating Ba levels are expected to change at weaning as Ba (and Ca) content and bioavailability is markedly different across plant and animal food sources11,12. To test this hypothesis, we investigated Ba/Ca patterns in teeth from human children for whom early life diets were recorded prospectively, and in teeth from captive macaques in which maternal milk was collected and suckling behaviour observed.

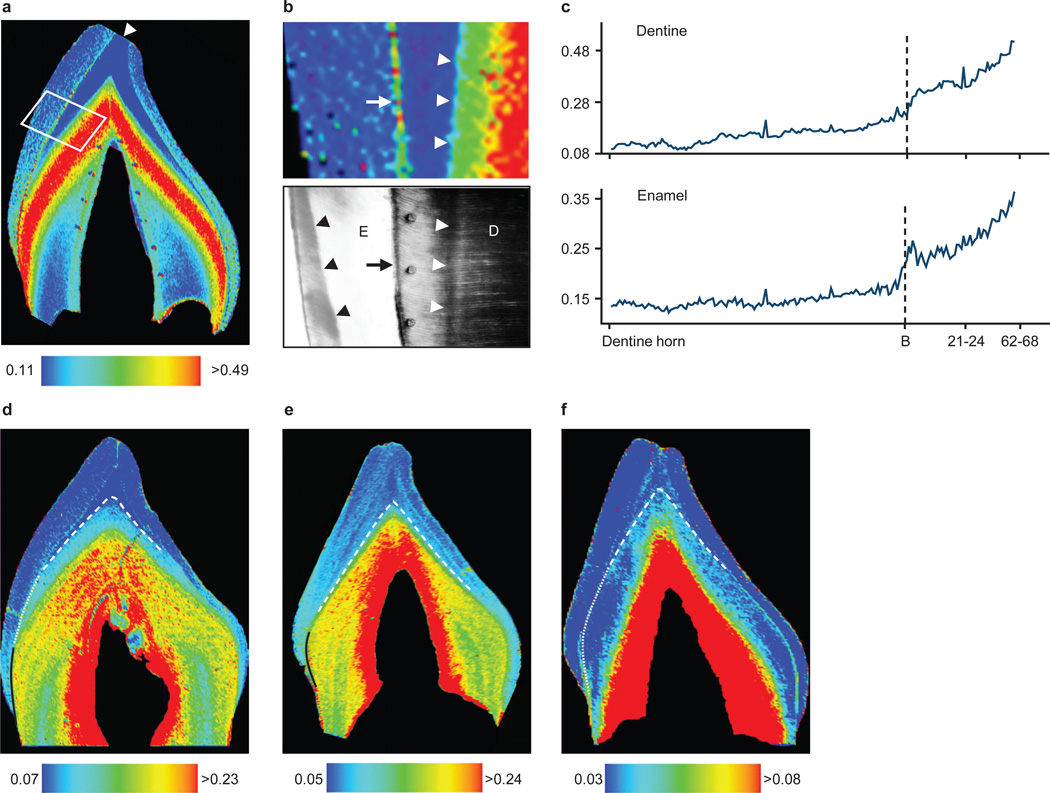

High resolution elemental analysis by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry revealed marked Ba/Ca increases in enamel and dentine formed immediately after birth in human deciduous teeth (n = 22 of 25 individuals) (Figure 1a–c). In 9 of 13 children who were initially breastfed and given infant formula later, two distinct zones of Ba/Ca distribution were apparent in postnatal regions formed before crown completion (Figure 1d,e). Histological analysis (Supplementary Figure S2) revealed a close correspondence between the formation time of the first zone and maternal reports of exclusive breastfeeding. Four individuals who continued to consume breast milk for a long period (9 – 42 months) after the introduction of formula at 1 – 2 months did not show two distinct Ba/Ca zones in enamel or dentine. In children for whom formula was introduced almost immediately after birth and who were breastfed for less than one month (Figure 1e), the first Ba/Ca zone immediately adjacent to the neonatal line was narrower than in infants exclusively breastfed for longer. Individuals who were exclusively breastfed during the entire period of tooth crown formation (n = 7 of 25; Figure 1f) showed an increase in Ba/Ca across the neonatal line, but as expected, no subsequent Ba/Ca zoning was apparent in postnatally formed dentine (as seen in infants who transitioned from breast milk to formula). Thus, Ba enrichment provides unambiguous evidence for postnatal feeding, as well as the beginning of supplementation, however the transition from exclusive breastfeeding to formula intake may be obscured when breast milk remains the predominant dietary component after formula introduction. The extent of Ba/Ca increase at birth varies due to inter-individual differences in breast milk and formula Ba content. This is illustrated in Figure 1f where the rise in Ba/Ca in response to breastfeeding is lower than in other individuals (Figure 1d,e). Data on Ba/Ca values are given in Supplementary Table S1 and Supplementary Figure S3.

Figure 1. Barium distribution in human deciduous teeth.

(a) Ba/Ca map of incisor. Dentine horn indicated by arrowhead. (b) Area highlighted in a and polarized light micrograph. In dentine (D), Ba/Ca levels show marked increase coinciding with the neonatal line (white arrowheads). Neonatal line in enamel (E) is indicated by black arrowheads and EDJ by arrows. (c) Ba/Ca measured adjacent to EDJ from dentine horn to cervix of a, which rose at birth and with introduction of infant formula (21–24 d). X-axis shows days since birth (B). (d–f) Three diet patterns: (d) breastfeeding for 3 months (dotted white line) followed by exclusive formula-feeding (solid black line), (e) formula introduced within 1 week of birth (solid black line), and (f) exclusive breastfeeding (dotted white line). Neonatal line indicated by dashed white line. Intensity indices are Ba/Ca × 10−4. High Ba/Ca adjacent to pulp (red zone) are in secondary dentine, a later-forming region not relevant to the current study (see Kohn et al.16).

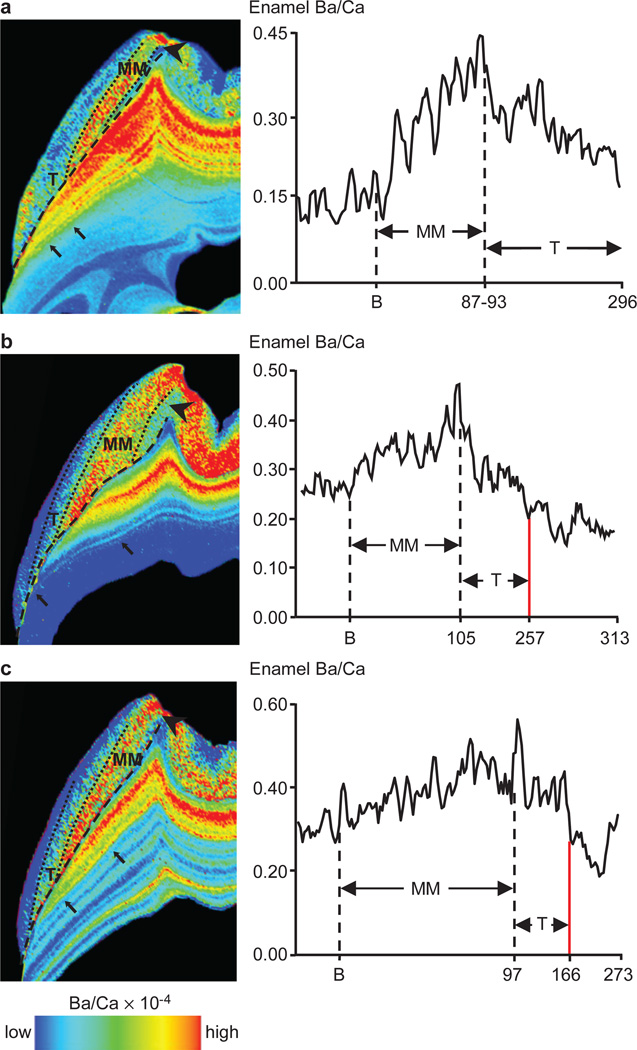

Macaque permanent first molars also showed clear distinctions in Ba/Ca between pre- and postnatal regions, and close correspondence of postnatal changes in dental tissues and mother’s milk (Supplementary Figure S4). While more diffuse due to the nature of mineralization, Ba/Ca patterns in enamel correlated closely with dentine. Temporal mapping revealed Ba/Ca increases for the first 3–3.5 months of postnatal life (Figure 2; Supplementary Figures S4–S6; Supplementary Table S2), followed by decreases that correlated with declines in suckling time and the initiation of solid food consumption. Moreover, Ba/Ca decreased more gradually during natural weaning than in individuals who experienced truncated weaning periods (Figure 2). In the most extreme case, an individual separated from its mother for several weeks at 166 days of age, precipitating cessation of milk synthesis and mammary gland involution, showed an abrupt Ba/Ca drop (Figure 2c), which was independently estimated at 151 – 183 days of age.

Figure 2. Barium distribution reveals natural and truncated weaning.

(a) Macaque 515: natural weaning after 296 d. (b) Macaque 152: weaned slightly early due to maternal separation at 257 d. (c) Macaque 401: markedly truncated weaning due to maternal separation at 166 d. This individual’s weight fluctuated during final seven months of life due to illness; post-weaning enrichment may be due to release from skeletal stores30. Diet transitions: prenatal regions (arrowhead), exclusive mothers’ milk (MM), transitional (T) periods, and post-weaning regions delineated in enamel (dotted lines) and dentine (black arrows). EDJ indicated with dashed line. Y-axis shows enamel Ba/Ca adjacent to EDJ. X-axis shows days since birth (B) and weaning (red line). Elemental maps of dentine and enamel were rendered on different scales to clearly show Ba/Ca transitions. The colour scale only reflects Ba/Ca variations within the dentine or enamel of a tooth.

Building upon our prospectively-validated human and macaque results, we precisely documented diet transitions in a juvenile Neanderthal13. Barium is incorporated into the mineral phase (hydroxyapatite) during tooth calcification, which occurs rapidly after secretion in dentine, and more slowly and diffusely in enamel during maturation14,15. Trace elements such as Ba are more resistant to postmortem diagenetic alteration in enamel than in dentine, due in part to the greater original mineral content and lack of natural pores16. Thus the distribution of Ba/Ca in well preserved tooth enamel may yield direct information on early life dietary transitions in fossil hominins.

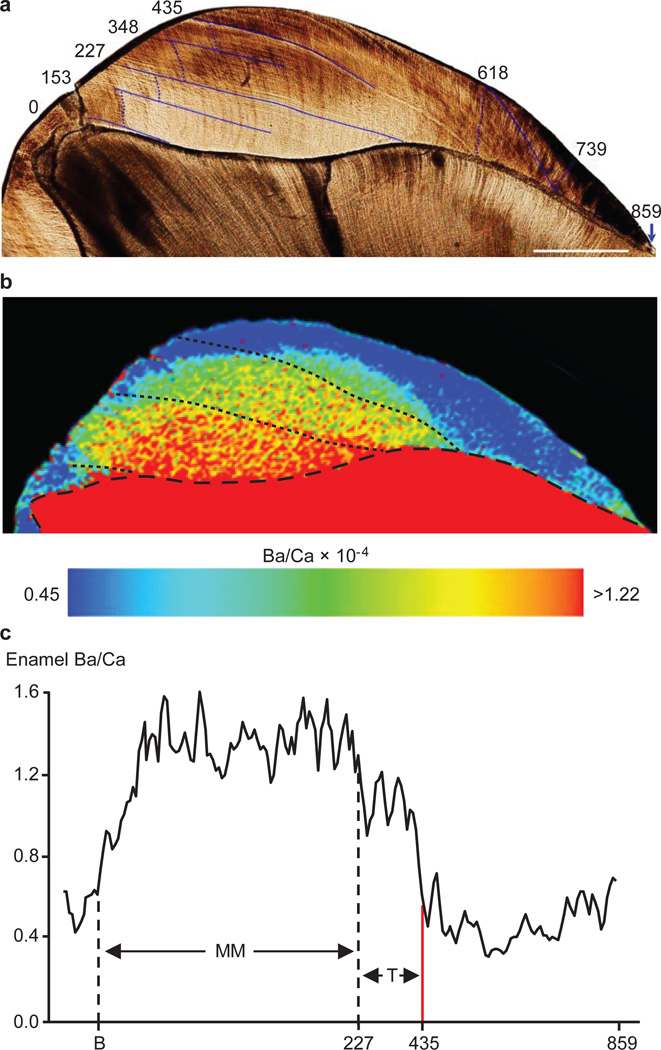

Chemical and temporal mapping of Neanderthal first molar enamel (Figure 3) revealed a transition pattern similar to the macaque that weaned abruptly. After approximately 13 days of prenatal enamel formation, Ba/Ca near the enamel-dentine junction increased and remained elevated until approximately 227 days of age (~7.5 months), followed by intermediate values until 435 days of age (1.2 years). After this age Ba/Ca rapidly returned to prenatal levels for the final 1.15 years of crown formation. The Ba/Ca patterns in enamel were not observed in dentine, likely due to diagenetic modification while interred. However, diagenesis did not appear to have a significant influence on enamel, as concentrations of diagenetic indicators17 were low (Supplementary Table S3 and Supplementary Figure S7). Furthermore, Ba/Ca levels were similar to published values for hominin enamel11,18, and Ba/Ca shifts were similar in form and timing between both mesial cusps, suggesting that the transition represents biogenic input rather than postmortem modification (Supplementary Discussion). Although the subsurface occlusal and cervical enamel appears to show minor cracks that may lead to local modification17, the majority of the tooth crown is intact and naturally-coloured. The Scladina individual has also yielded mtDNA and ancient enamel proteins19,20, indicating that it is a well-preserved fossil.

Figure 3. Dietary transitions in a Neanderthal permanent first molar.

(a) Developmental time (in days from birth) of stress lines in enamel (dark blue lines) was determined from daily growth increments (following dotted blue lines). Scale bar = 1 mm. (b) Ba/Ca map shows marked variations in enamel at birth, 227 and 435 d, which resemble human and macaque transition from exclusive maternal milk (MM) consumption to supplementation. (c) Ba/Ca in enamel adjacent to EDJ. X-axis shows days from birth (B) to proposed exclusive MM, transitional diet (T) periods and hypothesized weaning event (red line). Elevated Ba/Ca levels at the very beginning and end of crown formation are likely due to subtle diagenetic modification17.

Strontium-calcium ratios (Sr/Ca) in tooth enamel have been interpreted to reveal dietary transitions in baboons and humans9,21. However, these events were inferred from species-typical norms or recalled retrospectively years after the event, which may be subject to significant recall bias22. In light of this, and concerns that Sr might be more susceptible to diagenetic alteration than Ba due to its higher diffusivity23,24, we conducted a posthoc comparison of Sr/Ca and Ba/Ca for reconstructing early life diet. The interpretation of diet history from Sr/Ca mapping was impeded due to proportionately smaller changes in Sr levels across transitions and inconsistent patterns (Supplementary Figures S3, S8 and S9; Supplementary Tables S4 and S5; Supplementary Discussion). Two distinct regions between birth and 1.2 years were observed in the Neanderthal tooth for Ba/Ca and Sr/Ca, representing exclusive breastfeeding and solid food supplementation, although this is less clear from Sr/Ca when compared to Ba/Ca (Supplementary Figure S10). Thus Ba/Ca provides greater resolution of dietary transitions than Sr/Ca in extant and fossil material. Nonetheless, measurements of Sr isotopes in enamel have yielded useful data on diet and migration in early hominins18.

We have shown a direct correlation between Ba/Ca distributions in human deciduous teeth and breastfeeding data collected prospectively, thereby avoiding recall bias. In the macaques, patterns of suckling behaviour and Ba concentration in mother’s milk are predictive of Ba/Ca in dental tissues, which consistently show a decrease in Ba/Ca from the onset of supplementation. Taken collectively, these results demonstrate that Ba/Ca in teeth effectively reflect Ba intake via mother’s milk, and can be used to document developmental transitions in future studies of wild primate skeletal material, and for assessments of human health outcomes.

In the Scladina Neanderthal, the protracted weaning process typical in primates was interrupted by unknown cause(s), precipitating abrupt cessation of suckling. The period of exclusive breastfeeding in this Neanderthal is consistent with other hominoids; human hunter-gatherers and wild chimpanzees also begin to supplement milk with solid food by around six months of age5,25. Humans and chimpanzees may wean offspring as early as 1.0 and 4.2 years, respectively, without serious health effects, but average 2.3 – 2.6 years5 and 5.3 years25. When applied to additional samples, our approach will allow the evaluation of hypotheses that Neanderthal young routinely weaned at later ages than Upper Palaeolithic hominins26, or possessed faster life histories than modern humans13, which have important implications for models of hominin population growth and species replacement.

Methods

Human study participants

We used teeth from children enrolled in the Center for the Health Assessment of Mothers and Children of Salinas (CHAMACOS) study in Monterey County, California27,31. Pregnant women in the CHAMACOS cohort were recruited before 20 weeks gestation, and data on breastfeeding and infant formulas use were prospectively collected. Interviews were conducted with participants twice during pregnancy (at the end of the first and second trimesters), immediately postpartum, and when children were approximately 6, 12, 24, and 42 months old. Interviews were conducted in person, either at the study office or in a modified recreational vehicle that was used as a mobile office at the participant’s home. All questionnaires were administered in English or Spanish by trained bicultural interviewers, with the majority of interviews (94%) conducted in Spanish. Study instruments were developed in English, translated, and validated by Mexican-American immigrant staff members familiar with the language of the community and of southern Mexico from where many participants migrated.

At the second pregnancy interview (mean = 27 weeks gestation), the participant was asked if she intended to breastfeed her child. At each of the postpartum interviews she was asked if she was currently breastfeeding. At the interview when the mother first answered that she was no longer breastfeeding, she was then asked the child’s age when she had completely stopped breastfeeding and the reasons for stopping. Additionally, at the 6-month interview, the mother was asked if her child was receiving formula, and if so, at what age formula had been introduced. At the 12-month interview, she was asked at what age formula, solid foods and cow’s milk were each introduced. Duration of exclusive breastfeeding was defined as period between birth and the age when food or liquid other than breast milk or water was first given. All procedures were reviewed by the University of California at Berkeley Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects. Written informed consent was obtained from parents of all participating children and oral assent was obtained from 7-year olds.

From the 7-year assessment onwards, mothers were asked to bring in a tooth the child had shed. We randomly selected deciduous teeth that were free of obvious defects (caries, hypoplasias, fluorosis, cracks, extensive attrition) from 25 children who fell into one of three categories: exclusively breastfed from birth; initially breastfed with formula introduced within 1 – 2 months of birth; or exclusively formula fed soon after birth. We prepared ~100–150 µm sections in an axial labio-lingual plane following established methods.

Developmental times were assigned to marked shifts in Ba/Ca in tooth sections with histological analyses. To distinguish pre- and postnatal enamel and dentine, we photographed the enamel-dentine junction (EDJ) and the neonatal line in enamel and dentine. We overlaid these photomicrographs on our elemental maps to distinguish pre- and postnatal regions (Figure 1). In teeth of children whose mothers introduced formula within 1–2 months of birth, we noticed clear high Ba/Ca bands in the postnatally formed dentine some distance from the neonatal line. To assign a developmental time to these zones, we used polarized light microscopy to visualize prominent long-period incremental lines and cross-striations (daily growth increments) in enamel, and measured the distance between consecutive cross-striations to determine the average daily enamel secretion rate. Developmental times were then assigned to different points in enamel and dentine along the EDJ.

Macaques

Data and samples were obtained from two mother-infant dyads and two additional juveniles at the California National Primate Research Center, UC Davis, CA. All subjects were housed in large, intact social groups in outdoor corrals (0.2 hectare). Mothers received a nutritionally complete commercial diet (Outdoor Monkey Lab Diet, PMI Nutrition, Int’l, Brentwood, Missouri) twice daily. Subjects were part of a larger, on-going study on lactation and infant development8. Three times during lactation, at infant age 1, 3–4, and 5–6 months, mothers and infants were relocated for milk collection and morphometric measurements as described in detail elsewhere8. In the week previous to milk collection, trained technicians conducted four 10-minute focal observations between 8:30 and 12:30 and recorded duration of infant suckling behaviour28. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines and with UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval. Dentitions were collected opportunistically during animal necropsy as part of the CNPRC Biological Specimens Program.

Neanderthal Sample

The Scladina Neanderthal upper first maxillary molar was sectioned and temporally mapped for a previous developmental study that established this individual died at approximately 8 years of age13.

Ba measurements in teeth using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS)

We used a New Wave Research UP-213 laser ablation system equipped with a Nd:YAG laser emitting a nanosecond laser pulse in the fifth harmonic with a wavelength of 213 nm. The laser was connected to an Agilent Technologies 7500cs ICP-MS by Tygon® tubing. Details of our analytical methods have been published previously29. In brief, the laser beam was rastered along the sample surface in a straight line. A laser spot size of 30 µm, laser scan speed of 60 µm s−1 and ICP-MS total integration time of 0.50 s produced data points that corresponded to a pixel size32 of approximately 900 µm2. Reported element ratios (Ba/Ca×10−4 and Sr/Ca ×10−3) were calculated from concentrations determined using 43Ca, 88Sr and 138Ba isotopes and NIST 1486 bone meal as a standard. NIST 1486 was not certified for Ba so an average concentration calculated from determinations in two other studies33,34 was used. Diagenetic indicators were quantified using NIST 612 glass standard. Each line of ablation produced a single data file in comma separated value (.csv) format. Data was processed using Interactive Spectral Imaging Data Analysis Software (ISIDAS), a custom-built software tool written using Python programming language. ISIDAS reduced all .csv files into a single, exportable visualization toolkit (.vtk) file format. Images were produced by exporting .vtk files into MayaVi2 (Enthought Inc., Austin, Texas, USA), an open source data visualization application. Colour scales were applied using the linear blue-red LUT. Image backgrounds were converted to black (absent from the colour intensity scale) to clarify sample boundaries from the substrate. Elemental maps were rotated and black boarders added where needed to align rectangular figure panels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Linda Reynard, Noreen Tuross and Felicitas Bidlack provided comments on this project. Chitra Amarasiriwardena and Nicola Lupoli provided expertise in macaque milk analysis. Fossil samples were provided by Michel Toussaint, Rainer Gruen and Marie-Helene Moncell. The CHAMACOS study is funded by the US Environmental Protection Agency (RD 83171001 and RD 82670901 to BE) and the US National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (PO1 ES009605 to BE). Support for macaque data collection was provided by NSF BCS-0921978 (KH); milk samples were made possible through the ARMMS program (Archive of Rhesus Macaque Milk Samples). Histological study of the Scladina Neanderthal was funded by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. RJB is supported by Australian Research Council Discovery Grant (DP120101752) and SCU postdoctoral Fellowship grant. PD was supported by Australian Research Council Project Grant (LP100200254) that draws collaborative funding from Agilent Technologies and Kennelec Scientific. MA is supported by a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant 4R00ES019597-03. CA and MA are supported by NHMRC grant APP1028372.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions

CA, TMS and MA designed the study, undertook the elemental and histological analysis, and wrote the manuscript. AB and BE designed and analysed the human study. KH designed the macaque lactation study and collected samples. RJB analysed the Payre Neanderthal tooth in the Supplementary Information and assessed diagenetic alteration. CA, DJH, DB and PD undertook elemental imaging of tooth samples. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, in addition to editing the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ip S, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries. Evid. Rep. Tech. Assess. 2007;153:1–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDade TW. Life history, maintenance, and the early origins of immune function. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2005;17:81–94. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey LT. Weaning behaviour in human evolution. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010;21:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith TM, Tafforeau P. New visions of dental tissue research: Tooth development, chemistry, and structure. Evol. Anthropol. 2008;17:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sellen DW, Smay DB. Relationship between subsistence and age at weaning in "preindustrial" societies. Hum. Nature-Int. Bios. 2001;12:47–87. doi: 10.1007/s12110-001-1013-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee PC, Majluf P, Gordon IJ. Growth, weaning and maternal investment from a comparative perspective. J. Zool. 1991;225:99–114. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sellen DW. Comparison of Infant Feeding Patterns Reported for Nonindustrial Populations with Current Recommendations. J. Nutr. 2001;131:2707–2715. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hinde K, Power ML, Oftedal OT. Rhesus macaque milk: Magnitude, sources, and consequences of individual variation over lactation. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2009;138:148–157. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey LT, Dirks W, Dean MC, Jeffries TE. Tracking Dietary Transitions in Weanling Baboons (Papio hamadryas anubis) Using Strontium/Calcium Ratios in Enamel. Folia Primatol. 2008;79:197–212. doi: 10.1159/000113457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krachler M, Rossipal E, Micetic-turk D. Concentrations of trace elements in sera of newborns, young infants, and adults. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1999;68:121–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02784401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sponheimer M, Lee-Thorp JA. Enamel diagenesis at South African Australopith sites: Implications for paleoecological reconstruction with trace elements. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2006;70:1644–1654. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohn MJ, Morris J, Olin P. Trace element concentrations in teeth – a modern Idaho baseline with implications for archeometry, forensics, and palaeontology. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2013;40:1689–1699. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith TM, Toussaint M, Reid DJ, Olejniczak AJ, Hublin J-J. Rapid dental development in a Middle Paleolithic Belgian Neanderthal. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:20220–20225. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707051104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith CE. Cellular and Chemical Events During Enamel Maturation. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. M. 1998;9:128–161. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg M, Kulkarni AB, Young M, Boskey A. Dentin: structure, composition and mineralization. Front. Biosci. 2011;E3:711–735. doi: 10.2741/e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohn MJ, Schoeninger MJ, Barker WW. Altered states: effects of diagenesis on fossil tooth chemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 1999;63:2737–2747. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinz EA, Kohn MJ. The effect of tissue structure and soil chemistry on trace element uptake in fossils. Geochim. Cosmochim. Ac. 2010;74:3213–3231. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balter V, Braga J, Telouk P, Thackeray JF. Evidence for dietary change but not landscape use in South African early hominins. Nature. 2012;489:558–560. doi: 10.1038/nature11349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen-Marsh CM, et al. Extraction and sequencing of human and Neanderthal mature enamel proteins using MALDI-TOF/TOF MS. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2009;36:1758–1763. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orlando L, et al. Revisiting Neandertal diversity with a 100,000 year old mtDNA sequence. Curr. Biol. 2006;16:R400–R402. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphrey LT, Dean MC, Jeffries TE, Penn M. Unlocking Evidence of Early Diet from Tooth Enamel. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:6834–6839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711513105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gillespie B, d'Arcy H, Schwartz K, Bobo J, Foxman B. Recall of age of weaning and other breastfeeding variables. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2006;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kohn MJ, Moses RJ. Trace element diffusivities in bone rule out simple diffusive uptake during fossilization but explain in vivo uptake and release. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:419–424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209513110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ezzo JA. A test of diet versus diagenesis at Ventana Cave, Arizona. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1992;19:23–37. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith TM, et al. First molar eruption, weaning, and life history in living wild chimpanzees. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110:2787–2791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218746110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skinner M. Dental wear in immature Late Pleistocene European hominines. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1997;24:677–700. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harley K, Stamm N, Eskenazi B. The Effect of Time in the U.S. on the Duration of Breastfeeding in Women of Mexican Descent. Matern. Child Health J. 2007;11:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0152-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altmann J. Observational Study of Behavior: Sampling Methods. Behaviour. 1974;49:227–267. doi: 10.1163/156853974x00534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hare D, Austin C, Doble P, Arora M. Elemental bio-imaging of trace elements in teeth using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. J. Dent. 2011;39:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological profile for Barium. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2007. [Google Scholar]

Additional Online Methods References

- 31.Eskenazi B, et al. Association of in utero organophosphate pesticide exposure and fetal growth and length of gestation in an agricultural population. Environ. Health Persp. 2004;112:1116–1124. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lear J, Hare D, Adlard P, Finkelstein D, Doble P. Improving acquisition times of elemental bio-imaging for quadrupole-based LA-ICP-MS. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2012;27:159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Porte N, Mauerhofer E, Denschlag HO. Test of multielement analysis of bone samples using instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA) and anti-Compton spectrometry. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 1997;224:103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zaichick V, Zaichick S, Karandashev V, Nosenko S. The effect of age and gender on Al, B, Ba, Ca, Cu, Fe, K, Li, Mg, Mn, Na, P, S, Sr, V, and Zn contents in rib bone of healthy humans. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2009;129:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s12011-008-8302-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.