Abstract

Objective

Though a number of CT findings of bowel and mesenteric injuries in blunt abdominal trauma are described in literature, no studies on the specific CT signs of a transected bowel have been published. In the present study we describe the incidence and new CT signs of bowel transection in blunt abdominal trauma.

Materials and Methods

We investigated the incidence of bowel transection in 513 patients admitted for blunt abdominal trauma who underwent multidetector CT (MDCT). The MDCT findings of 8 patients with a surgically proven complete bowel transection were assessed retrospectively. We report novel CT signs that are unique for transection, such as complete cutoff sign (transection of bowel loop), Janus sign (abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement, both increased and decreased), and fecal spillage.

Results

The incidence of bowel transection in blunt abdominal trauma was 1.56%. In eight cases of bowel transection, percentage of CT signs unique for bowel transection were as follows: complete cutoff in 8 (100%), Janus sign in 6 (100%, excluding duodenal injury), and fecal spillage in 2 (25%). The combination of complete cutoff and Janus sign were highly specific findings in patients with bowel transection.

Conclusion

Complete cut off and Janus sign are the unique CT findings to help detect bowel transection in blunt abdominal trauma and recognition of these findings enables an accurate and prompt diagnosis for emergency laparotomy leading to reduced mortality and morbidity.

Keywords: MDCT, Blunt abdominal trauma, Bowel transection

INTRODUCTION

Small and large bowel injuries occur in approximately 5% of patients who experience severe blunt abdominal trauma and require a laparotomy (1-5). Presently, multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is the primary modality for the evaluation of trauma-related injury of the bowel and solid organs in the abdomen. The sensitivity of an MDCT in the diagnosis of surgically important bowel and/or mesenteric injury is about 90% (6), and with CT scans, the non-operative management of solid organ injury is generalized (7). In addition, the possibility of missed blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries is theoretically increased through the use of CT scans, though the overall incidence of missed injury is quite low and should not influence decisions concerning eligibility for non-operative management (8). Patients with missed blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries can develop peritonitis, sepsis, and multiple organ failure which could progress to death (9). Furthermore, a small delay in diagnosis may result in severe complications and high mortality rates (10-12). Therefore, the early detection of bowel injury after an abdominal blunt trauma is critical in order to decrease patient morbidity and mortality.

The most severe form of bowel injury is transection, which means the bowel loop loses its continuity completely in which prompt surgery is crucial. Numerous CT signs of bowel and mesenteric injuries in blunt abdominal trauma have been described in literature, however, there is no studies specifying the radiological characteristics of a transected bowel. Therefore, we investigated the incidence of a complete bowel transection in all blunt abdominal trauma patients. Here we describe the various MDCT findings of bowel transection in blunt abdominal trauma in this paper.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

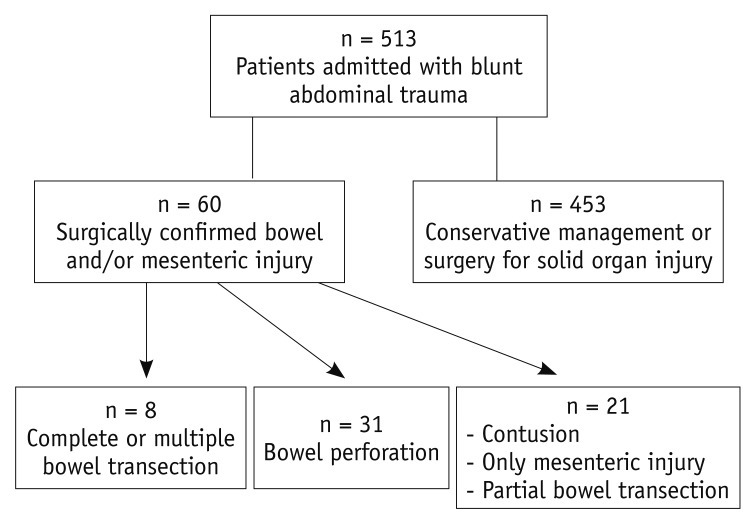

This retrospective study was approved by an institutional review board, and the requirement for informed consent was waived. We retrospectively analyzed all the patients who had been admitted for blunt abdominal trauma in the databases of two hospitals, namely Hallym University College of Medicine, Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital, and Hallym University College of Medicine, Sacred Heart Hospital, between March 2006 and September 2012. A total of 513 patients were admitted for blunt abdominal trauma at these hospitals and all of them underwent MDCT prior to surgery. Most of them had been admitted through the emergency Level 1 trauma centers. Some patients were only treated with conservative management while others underwent surgeries. The surgical records of all of the patients were reviewed. Sixty patients with laparatomy-confirmed bowel and/or mesentery injury were identified. Thirty-one patients with laparatomy-confirmed bowel perforation were identified and there were only eight patients who had had a complete transection of the bowel loop. Seven of the eight identified patients were men, and one was woman. Their median age was 47 years (range 34-63 years). Four patients were injured as a result of traffic accidents (TA), and all of them had been in the car (in car TA). Four of the patients had been sandwiched between some materials, like a car or machines in factories. A flowchart of the overall study design is presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of patient selection in this study.

CT Technique

CT examinations were performed with one of three MDCT scanners (Brilliance CT 64-Channel, Philips Healthcare, MX 8000 IDT, Philips Healthcare, or SOMATOM Sensation 64, Siemens Healthcare) for all patients who were in emergency care. The average time from trauma to CT was approximately 4.9 hours.

Our trauma CT protocol included unenhanced CT scans and CT scans with the administration of 120 mL of an intravenous contrast medium (iopromide, Ultravist 300; Bayer Medical Systems) at a rate of 3 mL/sec. Scanning was performed with a 70-sec delay and a section thickness of 5 mm.

The scanning ranged from the xyphoid process to the lower end of the symphysis pubis. The CT scanning parameters were as follows: for 64-detector rows, a beam collimation of 0.625 mm × 64, a pitch of 0.75, kVp/effective mA 120/240, and a gantry rotation time of 0.75 second; for 16-detector rows, a beam collimation of 0.625 mm × 16, a pitch of 0.891, kVp/effective mA 120/240, and a gantry rotation time of 0.75 second; and for 64-detector rows, a beam collimation of 0.625 mm × 64, a pitch of 0.891, kVp/effective mA, 120/240, and a gantry rotation time of 0.75 sec. Isotropic raw data was acquired with a slice thickness of 1 mm and an interval of 1 mm at MDCT. Using this raw data, an axial image was obtained with a slice thickness of 5 mm and an interval of 5 mm; the coronal and sagittal multiplanar reformation (MPR) images were reconstructed on a workstation. Each MPR image was obtained at a 5 mm interval with a slice thickness of 5 mm.

Image Analysis

The CT images were retrospectively evaluated by consensus by three radiologists with 2048 × 2560 picture archiving and communication system (PACS) workstation (PiView Star, INFINITT Healthcare Co. LTD., Seoul, Korea). In case of two or more pre-operative CT scans were performed, the first pre-operative images were analyzed. All images were interpreted by two abdominal radiologists (each with more than 10 years of experience in the interpretation of abdominopelvic CT) and a radiology resident. The consensus of the investigators was obtained on the CT features of the patients.

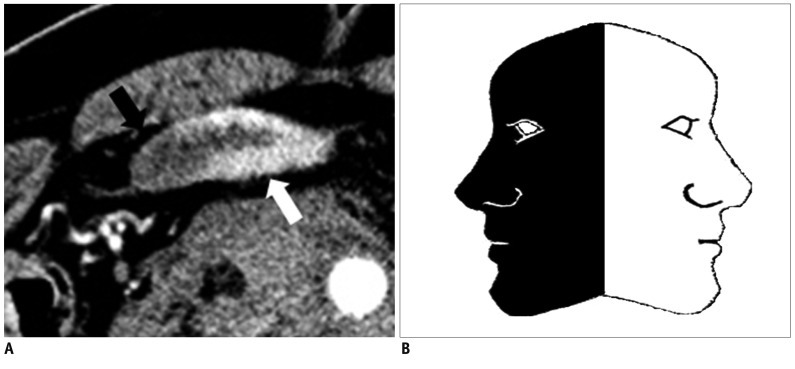

We summarized several new CT signs, which are unique for transection, as well as other CT signs that have previously been noted in literature. The CT signs unique for bowel transection are complete cutoff sign (transection of bowel loop), Janus sign (abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement, both increased and decreased), and fecal spillage (Fig. 2). Other CT signs of bowel and mesenteric injury frequently noted in literature include hyperenhancing mucosa, free air, bowel wall thickening, intramural gas, intraperitoneal fluid, retroperitoneal fluid, mesenteric extravasation, termination of mesenteric vessels, mesenteric vessel beading, focal mesenteric hematoma, and mesenteric infiltration. Associated CT findings, such as solid organ injury, focal dissection of large vessel, lateral hernia, and fracture of lumbar vertebra, were also assessed.

Fig. 2.

Janus sign.

A. Axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan shows well enhancing distal jejunal loop (white arrow) and continuous bowel loop shows no enhancement abruptly (black arrow). Most of patients with bowel transection show this appearance in MDCT and we named it Janus sign. B. Janus is two-faced god in Roman mythology.

RESULTS

Prevalence and Location

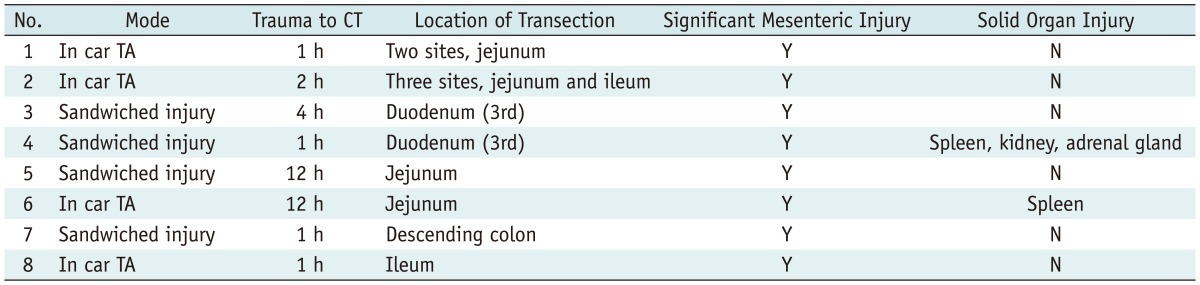

The incidence of bowel transection in blunt abdominal trauma was 1.56%. The trauma mode and operative findings for all patients are summarized in Table 1. Based on the location, three patients (37.5%) had a transection of the jejunum, two (25%) of the duodenum, one (12.5%) of the ileum, one of the descending colon, and one had a multiple transection of the jejunum and ileum.

Table 1.

Summarized Information of Eight Patients with Bowel Transection

CT Findings

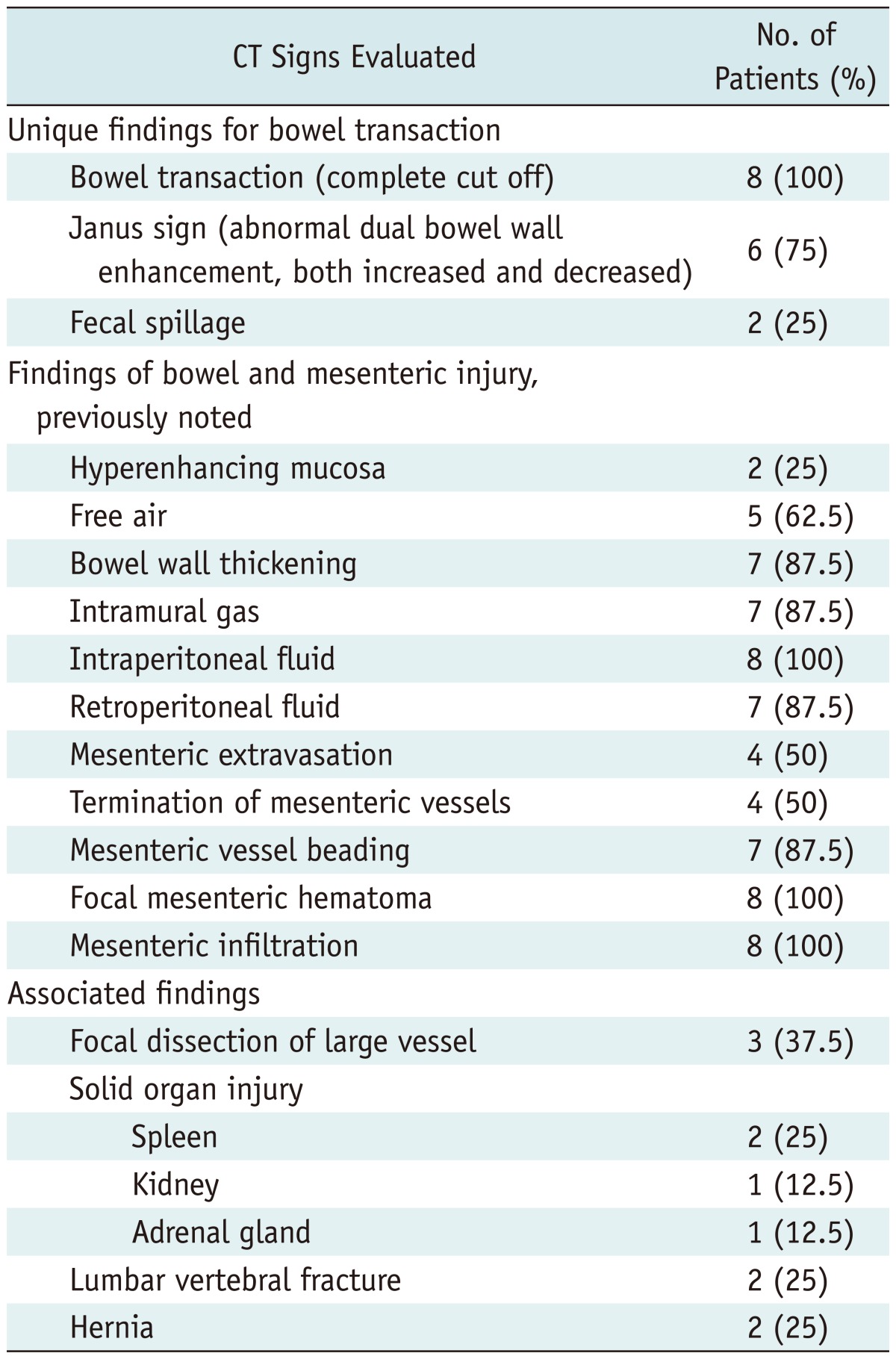

The CT findings of complete bowel transection are summarized in Table 2. In the eight cases of bowel transection, we assessed the CT findings according to following three categories. Firstly, the CT signs, that were unique for bowel transection, were assessed which included complete cutoff sign (transection of bowel loop), Janus sign (abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement, both increased and decreased), and fecal spillage. Complete cutoff sign was present in eight patients (100%) (Figs. 3-5). At the transection site, the bowel loop with abnormally increased enhancement abruptly lost its strong enhancement and presented decreased enhancement, and a bowel transection followed was called Janus sign (abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement, both increased and decreased), and was present in six patients (75%) (Figs. 2-4). Two patients did not have Janus sign but experienced a duodenal injury. Excluding the patients with a duodenal injury, the percentage of patients with Janus sign increased to 100%. All six patients, excluding those with duodenal injury, showed both of these signs concurrently and hence these could serve as a specific sign of bowel transection. Fecal spillage was observed in two cases (25%) of transection at the descending colon and distal ileum (Fig. 6).

Table 2.

CT Signs Evaluated and Number of Patients with Each Sign

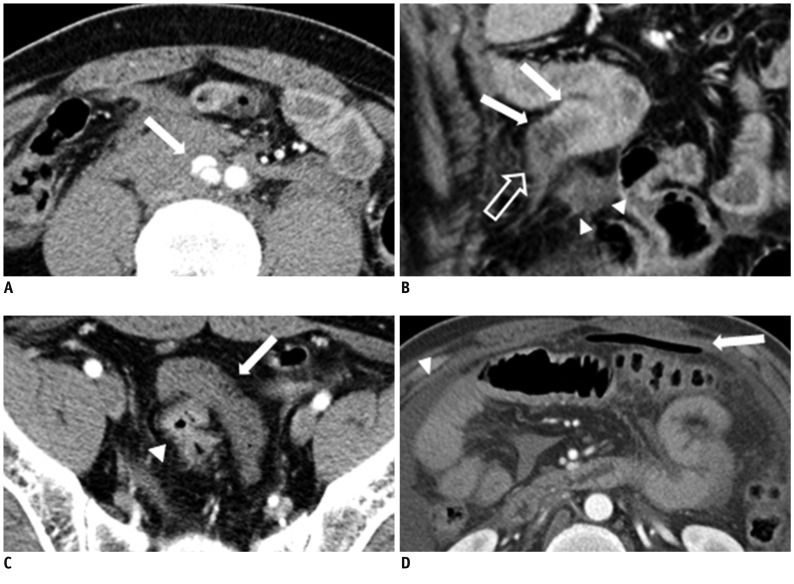

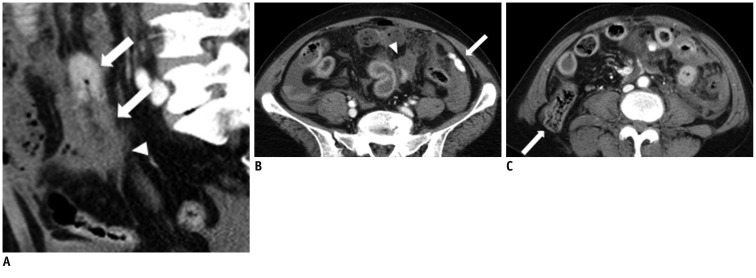

Fig. 3.

MDCT findings of jejunal segmental transection of 42-year-old man.

A. Axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan which was taken 1 hour after trauma shows focal dissection of right common iliac artery (arrow) and there is diffuse hematoma surrounding lesion. By focusing on this focal dissection, mesenteric hematoma around dissection was mistakenly thought to have originated from great vessel injury. B. Coronal reformatted contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan shows complete cut off of bowel loop at distal jejunum; complete cut off sign (open arrow). Jejunal loop shows abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement (both increased and decreased), and loses continuity soon after; Janus sign (arrows). Other end of broken bowel loop is identified nearby (arrowheads). C. Axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan presents 10 cm-long fragmented bowel segment in pelvic cavity (arrow). This fragmented bowel segment had no connection with adjacent bowel loop. There is no wall enhancing compared to normal enhanced bowel wall (arrowhead). D. Second axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT, taken 17 hours after trauma, shows free air (arrow) and increased amount of fluid (arrowhead) in abdomen. At first CT scans (A-C), there was no free air.

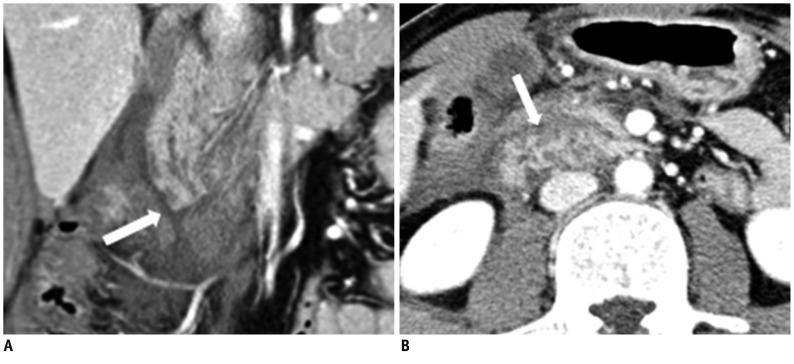

Fig. 5.

MDCT findings of duodenal transection of 37-year-old man.

A. Coronal reformatted contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan shows transection of third portion of duodenum (arrow). B. Axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan of duodenum around transection shows hyperenhancing mucosa, representing shock bowel (arrow).

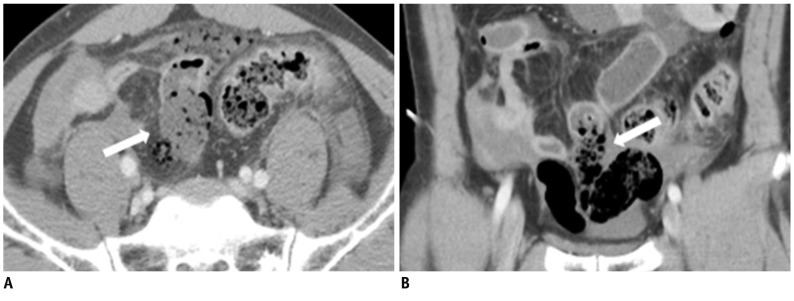

Fig. 4.

MDCT findings of multiple small bowel transections of 47-year-old woman.

A. Sagittal reformatted contrast enhanced multidetector CT scan shows complete cut off of bowel loop at proximal ileum. Ileal loop shows abnormal dual bowel wall enhancement (both increased and decreased); Janus sign (arrows). Surrounding hematoma (arrowhead) makes it difficult to recognize transected bowel end. B, C. Axial contrast enhanced multidetector CT scans show mesenteric extravasation (arrow in B), mesenteric hematoma (arrowhead in B) and lateral hernia of ascending colon (arrow in C).

Fig. 6.

MDCT findings of distal ileal transection of 54-year-old man.

A, B. Axial and coronal reformmated contrast enhanced multidetector CT scans show transection of distal ileum and fecal spillage (arrow in A, B).

Secondly, other CT signs of bowel and mesenteric injury reported in literature were assessed. The CT of two patients with duodenal transections did not show Janus sign, however, hyperenhancing duodenal mucosa was indicated, and hyperenhancing mucosa was evident in only these two patients (25%), and a CT of one of them presented hyperenhancing mucosa in the extensive bowel loop with a flattened inferior vena cava (IVC). Intramural gas (87.5%), diffuse bowel wall thickening (87.5%), intraperitoneal fluid (100%), and retroperitoneal fluid (87.5%) were presented with high percentage.

In our study, mesenteric injury was present in all of the patients, and the CT findings were indicated that four of the patients (50%) with mesenteric extravasation, four patients with bowel transection including showed abrupt mesenteric vessel termination, and seven patients (87.5%) with mesenteric vessel beading. Mesenteric focal hematoma and infiltration had the highest sensitivity for mesenteric injury, and they were seen in all of the patients.

Thirdly, other associated CT findings were also assessed. Focal dissection of the large vessel presented in three patients (37.5%): two had focal dissection of the right common iliac artery (Fig. 3) and the other had focal dissection of the left common iliac artery. Solid organ injury was observed in only two patients (25%), i.e., the spleen (25%), kidneys (12.5%), and adrenal glands (12.5%). The percentage of solid organ injury patients with a bowel transection was lower than expected and only two of the eight patients had lumbar vertebral fracture and a lateral hernia (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

Recently, a multidetector CT scan is generally thought to be the primary imaging modality for the evaluation of patients with blunt abdominal trauma. For a non-severe solid organ injury in a CT, non-operative management is the standard treatment (13). However, if bowel or mesenteric injury involvement is suspected, a laparotomy is usually needed. A delayed diagnosis of surgically important bowel or mesenteric injury leads to significant morbidity and mortality from hemorrhage, peritonitis, or abdominal sepsis. The timely diagnosis of bowel and mesenteric injuries requiring operative repair depends almost exclusively on their early detection by the radiologist during CT examination.

The most severe form of bowel injury is transection, which means the bowel loop loses its continuity completely. This type of injury rarely occurs in patients with blunt abdominal trauma, but it needs hyperacute surgical repair as soon as possible. Numerous CT signs of bowel and mesenteric injuries in blunt abdominal trauma have been described in the literature, however, to our knowledge, there is no report specifying the radiological characteristics of a transected bowel.

In the present study, the incidence of bowel transection among patients admitted for blunt abdominal trauma was 1.56%. Considering that a hollow viscous Check please! injury during blunt abdominal trauma is present in approximately 5% of patients who experience severe blunt abdominal trauma (1-5), the incidence of bowel transection during blunt abdominal trauma is higher than expected. Since the complete transection of the bowel is such a severe injury that some unique CT findings exist, radiologists need to consider this critically important major injury.

In severe bowel injuries, bowel wall discontinuity on CT scan is although almost 100% specific, has low sensitivity, i.e., approximately 7% of blunt abdominal trauma patients. Since traumatic bowel perforations are small and cannot be directly identified on CT, diagnosis of small bowel perforations demands careful attention from the radiologist to detect subtle abnormality (14). Also studies suggest that, bowel wall discontinuity usually indicated a focal defect of the bowel wall. In bowel transection, however, discontinuity appears not just as a focal defect but as a complete cutoff, and we therefore called this CT finding complete cutoff sign. This sign was present in 100% of our eight patients with bowel transection. The high frequency of observations of this feature is thought to be natural because total bowel transection means the complete loss of bowel continuity. However, recognition of this finding at an initial CT scan is not easy, since, there are hematomas and mesenteric infiltration surrounding the transection site, a bowel transection may be difficult to detect. Indeed, there were some cases in which we missed this sign during the initial CT review.

Transection is accompanied by various signs. One of the very unique signs we observed is the bowel segment with increased and decreased enhancement at the same time in one bowel loop. We named this as "Janus sign", since an unequivocal focal abnormal enhancement (decreased or increased) of a segment of bowel is known to be a highly suspicious finding that is often associated with a significant injury (15). Six of our eight patients with bowel transection (75%) showed an increased and focally decreased bowel segment at the same time in one bowel loop: the bowel loop with an abnormally increased enhancement abruptly lost its strong enhancement and presented decreased enhancement, and bowel wall transection followed. The contiguous existence of focally increased and decreased enhancement in one bowel loop is thought to be a rare imaging feature, however, in patients with a bowel transection, this feature presented in 75% of the cases. When we excluded the patients with duodenal injury, the percentage of this sign was 100%. Therefore, even if it is a rare finding, if this imaging feature is shown, major bowel trauma, like transection, should be considered, and if there is a Janus sign, our findings showed that a bowel wall transection also followed near the site. Therefore, the Janus sign may be a specific sign of bowel transection. A diffusely increased bowel wall enhancement is commonly considered to be an indirect sign of bowel trauma. The potential causes of increased bowel wall enhancement are the leakage of contrast material from increased vascular permeability during the hypoperfusion preferential shift of blood flow to the mucosa, or the slowing of the transit time of blood through the mucosa during hypotension (16). The reason Janus sign appears at th ebowel transection sites is still unclear, however, we can hypothesize that hypoperfusion increases the enhancement of the bowel loop, and mesenteric injury accompanied by bowel transection decreases the enhancement of the bowel loop. A bowel loop showing decreased enhancement represents a devascularized bowel loop with an irregular margin at the transection site.

Fecal spillage is not usually mentioned in literature that deals with the imaging of blunt abdominal trauma. This is could be due to its rare occurrence in simple perforations. In case of feces in the bowel lumen (usually the colon or distal ileum), the feces will inevitably spill out to the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, this sign is considered to be almost 100% specific to bowel injury, even if sensitivity is thought to be low.

The most common cause of shock in the setting of trauma is hemorrhage. This results in decreased circulating blood volumes, which can be complicated by the derangement of circulatory control. CT manifestations of shock bowel include mucosal hyperenhancement, diffuse wall enhancement, transmural edema, and fluid-filled dilated loops (17-19). In the present study, only two patients showed hyperenhancing mucosa, and both of them had duodenal injury. The reason hyperenhancing mucosa was only present in patients with duodenal transection is not obvious. However, we can presume that it is because there are many significant blood vessels around the duodenum, and the amount of hemorrhage is greater than the injury to other regions.

Extraluminal gas (free air) is highly suggestive, but not a pathognomonic sign, of bowel perforation. Pneumoperitoneum is found on CT in 20% to 75% of patients with proven bowel perforations (6, 20-24). In our cases of bowel transection, the most severe form of bowel injury, free air was observed in 62.5% of patients. It can be speculated that in cases of transection, free air should be seen with high frequency, but the percentage was slightly higher than that of a simple perforation. It therefore seems obvious that the degree of bowel injury and the frequency of free air have no significant correlation.

The other signs such as bowel wall thickening, intramural gas, intraperitoneal fluid, and retroperitoneal fluid, are known to be sensitive but not as specific. Almost all of our patients showed bowel wall thickening, intramural gas, intraperitoneal and/or retroperitoneal fluid. This suggests that these signs might be a sensitive sign of severe bowel trauma.

There is always a possibility of a complete bowel transection to have any mesenteric injury. Accordingly, the CT finding-related mesenteric injuries we observed were mesenteric extravasation, termination of the mesenteric vessels, mesenteric vessel beading, focal mesenteric hematoma, and mesenteric infiltration. All the findings showed higher percentage in bowel transection than reported in simple bowel perforation. Mesenteric hematoma and mesenteric infiltration make it hard to find bowel discontinuity or transection in a CT scan, however, they can also be a clue for bowel discontinuity or transection because they can suggest bowel or mesenteric injury.

There were few limitations in our study such as the small number of patients and retrospective nature of the study design may reduce the power of this study.

In conclusion, the transection of bowel loop, the most severe form of bowel injury in blunt trauma, was with some unique CT findings. In particular, the focal increased and decreased bowel segment in one bowel loop contiguously, the Janus sign was present in 100% of patients with a small and large bowel transection. So even if it is a rare finding in a bowel injury, if there is a contiguous existence of focal increased and decreased enhancement in one bowel loop, major bowel trauma, like a transection, should be considered. Furthermore, when the Janus sign was present, a bowel wall transection was also located near the site, hence the Janus sign can be a specific sign of bowel transection. By recognizing the findings described in this paper, there is a high probability of awareness of severe bowel injury. This could lead to emergency laparotomy with appropriate surgical plan and, therefore, lower the patient's chance of mortality and morbidity.

References

- 1.Dauterive AH, Flancbaum L, Cox EF. Blunt intestinal trauma. A modern-day review. Ann Surg. 1985;201:198–203. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198502000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox EF. Blunt abdominal trauma. A 5-year analysis of 870 patients requiring celiotomy. Ann Surg. 1984;199:467–474. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198404000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buck GC, 3rd, Dalton ML, Neely WA. Diagnostic laparotomy for abdominal trauma. A university hospital experience. Am Surg. 1986;52:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rizzo MJ, Federle MP, Griffiths BG. Bowel and mesenteric injury following blunt abdominal trauma: evaluation with CT. Radiology. 1989;173:143–148. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.1.2781000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis JJ, Cohn I, Jr, Nance FC. Diagnosis and management of blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1976;183:672–678. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197606000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atri M, Hanson JM, Grinblat L, Brofman N, Chughtai T, Tomlinson G. Surgically important bowel and/or mesenteric injury in blunt trauma: accuracy of multidetector CT for evaluation. Radiology. 2008;249:524–533. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492072055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croce MA, Fabian TC, Menke PG, Waddle-Smith L, Minard G, Kudsk KA, et al. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma is the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients. Results of a prospective trial. Ann Surg. 1995;221:744–753. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199506000-00013. discussion 753-755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller PR, Croce MA, Bee TK, Malhotra AK, Fabian TC. Associated injuries in blunt solid organ trauma: implications for missed injury in nonoperative management. J Trauma. 2002;53:238–242. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200208000-00008. discussion 242-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menegaux F, Trésallet C, Gosgnach M, Nguyen-Thanh Q, Langeron O, Riou B. Diagnosis of bowel and mesenteric injuries in blunt abdominal trauma: a prospective study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fakhry SM, Brownstein M, Watts DD, Baker CC, Oller D. Relatively short diagnostic delays (< 8 hours) produce morbidity and mortality in blunt small bowel injury: an analysis of time to operative intervention in 198 patients from a multicenter experience. J Trauma. 2000;48:408–414. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200003000-00007. discussion 414-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robbs JV, Moore SW, Pillay SP. Blunt abdominal trauma with jejunal injury: a review. J Trauma. 1980;20:308–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killeen KL, Shanmuganathan K, Poletti PA, Cooper C, Mirvis SE. Helical computed tomography of bowel and mesenteric injuries. J Trauma. 2001;51:26–36. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes TM, Elton C. The pathophysiology and management of bowel and mesenteric injuries due to blunt trauma. Injury. 2002;33:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(02)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brofman N, Atri M, Hanson JM, Grinblat L, Chughtai T, Brenneman F. Evaluation of bowel and mesenteric blunt trauma with multidetector CT. Radiographics. 2006;26:1119–1131. doi: 10.1148/rg.264055144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malhotra AK, Fabian TC, Katsis SB, Gavant ML, Croce MA. Blunt bowel and mesenteric injuries: the role of screening computed tomography. J Trauma. 2000;48:991–998. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200006000-00001. discussion 998-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brody JM, Leighton DB, Murphy BL, Abbott GF, Vaccaro JP, Jagminas L, et al. CT of blunt trauma bowel and mesenteric injury: typical findings and pitfalls in diagnosis. Radiographics. 2000;20:1525–1536. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00nv021525. discussion 1536-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lubner M, Demertzis J, Lee JY, Appleton CM, Bhalla S, Menias CO. CT evaluation of shock viscera: a pictorial review. Emerg Radiol. 2008;15:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10140-007-0676-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiesner W, Khurana B, Ji H, Ros PR. CT of acute bowel ischemia. Radiology. 2003;226:635–650. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263011540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittenberg J, Harisinghani MG, Jhaveri K, Varghese J, Mueller PR. Algorithmic approach to CT diagnosis of the abnormal bowel wall. Radiographics. 2002;22:1093–1107. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se201093. discussion 1107-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sivit CJ, Eichelberger MR, Taylor GA. CT in children with rupture of the bowel caused by blunt trauma: diagnostic efficacy and comparison with hypoperfusion complex. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1195–1198. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.5.7976900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stuhlfaut JW, Soto JA, Lucey BC, Ulrich A, Rathlev NK, Burke PA, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: performance of CT without oral contrast material. Radiology. 2004;233:689–694. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333031972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donohue JH, Federle MP, Griffiths BG, Trunkey DD. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of blunt intestinal and mesenteric injuries. J Trauma. 1987;27:11–17. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagiwara A, Yukioka T, Satou M, Yoshii H, Yamamoto S, Matsuda H, et al. Early diagnosis of small intestine rupture from blunt abdominal trauma using computed tomography: significance of the streaky density within the mesentery. J Trauma. 1995;38:630–633. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199504000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mirvis SE, Gens DR, Shanmuganathan K. Rupture of the bowel after blunt abdominal trauma: diagnosis with CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:1217–1221. doi: 10.2214/ajr.159.6.1442385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]