Abstract

Objectives

We test the hypothesis that an evidence-based preventive intervention will change adolescent friendship networks to reduce the potential for peer influence toward antisocial behavior. Altering adolescents’ friendship networks in this way is a promising avenue for achieving setting-level prevention benefits such as expanding the reach and durability of program effects.

Methods

Beginning in 2002, the PROSPER randomized control trial assigned two entire 6th grade cohorts of 14 rural and small town school districts in Iowa and Pennsylvania to receive the intervention and of 14 to control. A family-based intervention was offered in 6th grade and a school-based intervention was provided in 7th grade. Over 11,000 respondents provided five waves of data on friendship networks, attitudes, and behavior in 6th-9th grade. Antisocial influence potential was measured by the association between network centrality and problem behavior for each of 256 networks (time, grade cohort, and school specific).

Results

The intervention had a beneficial impact on antisocial influence potential of adolescents’ friendship networks, with p < .05 for both of the primary composite measures.

Conclusions

Current evidence-based preventive interventions can alter adolescents’ friendship networks in ways that reduce the potential for peer influence toward antisocial behavior.

Keywords: prevention, social networks, substance use, problem behavior

INTRODUCTION

The present study tests whether evidence based preventive interventions alter adolescents’ friendship networks in ways that diminish the potential for peer influence toward problem behaviors such as substance use and delinquency. Universal preventive interventions targeting early adolescents are a key tool for addressing the public health problems associated with behaviors such as substance use and delinquency, and there is now good evidence that such interventions can significantly reduce rates of these behaviors.1-4 Though entire school grades often receive current universal programs, the programs typically seek to change individual adolescents’ attitudes and behavior rather than to alter settings. Tseng and Seidman have argued that targeting settings is a promising avenue for enhancing program effectiveness by creating conditions that reinforce and diffuse initial program efforts and thereby increase the reach and duration of beneficial effects.5,6

We focus on social networks as a potential target for setting-level intervention effects.7 The social network of a setting consists of the individuals there and the set of relationships among them. The properties of that network are characteristics of the setting as a whole, and these properties evolve as some relationships end and others begin. Valente’s8 recent review argues that, across a wide variety of applications, network interventions are frequently more effective than alternative approaches. We believe that intervention effects on friendship networks, in particular, are a promising avenue for increasing the potency, reach, and durability of efforts to reduce adolescent problem behavior.5,6,9,10 Our work builds on Gest and colleague’s7 discussion of how concepts and methods of social network analysis apply to prevention efforts. Within Valente’s framework, we study intervention through “rewiring” the network, that is, altering the pattern of connections.8 To our knowledge, there have been no studies concerning this type of network effect for interventions addressing adolescent problem behavior.

Social Networks and Problem Behavior

Social networks are especially relevant to interventions intended to prevent problem behavior because peer influence, which is strongly linked to these behaviors, is inherently a network process. Prominent theories suggest that peer influence is a major contributor to problem behavior,11-13 and abundant research supports that position.14-17 Consequently, interventions to prevent or reduce adolescent problem behaviors frequently target peer influence.7,18,19 Preventive interventions addressing substance use, for example, often provide adolescents objective information about peer use to counteract perceived social norms that favor use. Many interventions also seek to build communication and “refusal” skills to help deflect peers’ invitations to use.

Adolescent friendship networks have critical bearing on peer influence because they determine the influence to which each adolescent is exposed. Adolescents connected to antisocial friends receive influence toward problem behavior, while those connected to friends who oppose and refrain from that behavior receive influence not to engage in it. Individual-focused interventions typically impart messages and skills to enable individuals to counter antisocial peer influences whereas a network intervention might focus on shifting the pattern of friendships

Interestingly, many effective preventive interventions that target individual attitudes and behaviors include elements that might bring about beneficial changes in adolescent social networks as well. Notably, programs delivered to students often encourage choosing prosocial friends over antisocial friends,1-3 and programs targeting parents often stress monitoring adolescents’ friendship choices and discouraging friendships with antisocial youth.4,10 If these efforts were effective, the typical network positions of prosocial versus antisocial youth would change in ways that would reduce the network’s overall potential for peer influence toward antisocial behavior (as we describe in detail below).

The research we present is the first test of whether universal preventive interventions can alter adolescent social networks in this way. Specifically, we analyze data from PROSPER to estimate intervention effects on adolescent, grade-cohort friendship networks. PROSPER is a community-partnership-based delivery system for evidence-based interventions to prevent substance use. We reason that the intervention related efforts to address negative peer influence will achieve their effectiveness, in part, by diminishing the influence potential of youth who exhibit problem behavior. We hypothesize that, compared to control schools, in schools randomly assigned to employ the PROSPER partnership model there will be a less positive (or more negative) association between individuals’ network-defined potential to influence others and their antisocial behavior and attitudes.

Network Structure, Influence Potential, and Preventive Interventions

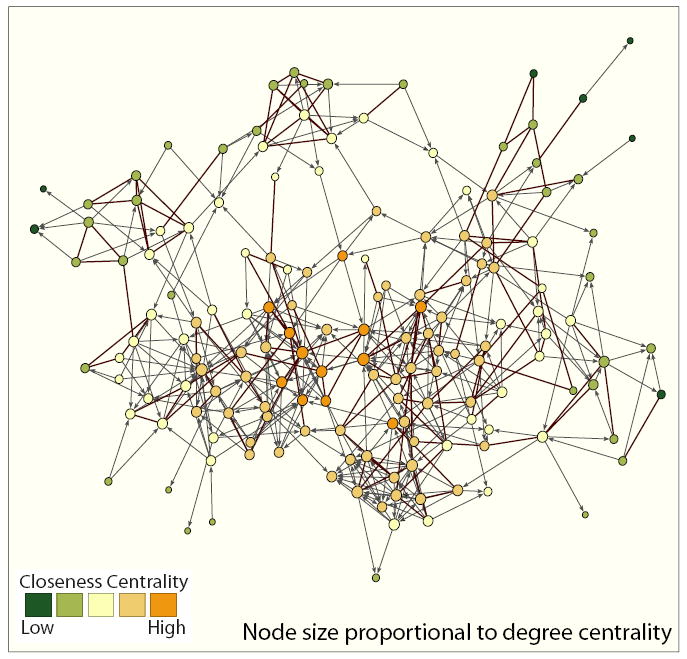

An individual’s potential to influence others corresponds to the network concept of centrality, which is each person’s prominence or importance in the network in terms of his or her direct and indirect connections to others. Network scholars have defined several different types of centrality,20,21 each emphasizing a different aspect of those connections, and several types have proved relevant to problem behavior.22-24Figure 1 illustrates two forms of centrality (degree and closeness) for the friendship network of students in one school in our study for the fall of 6th grade.

Figure 1.

Example of degree and closeness centrality (undirected), Fall of 6th grade for students in one school.

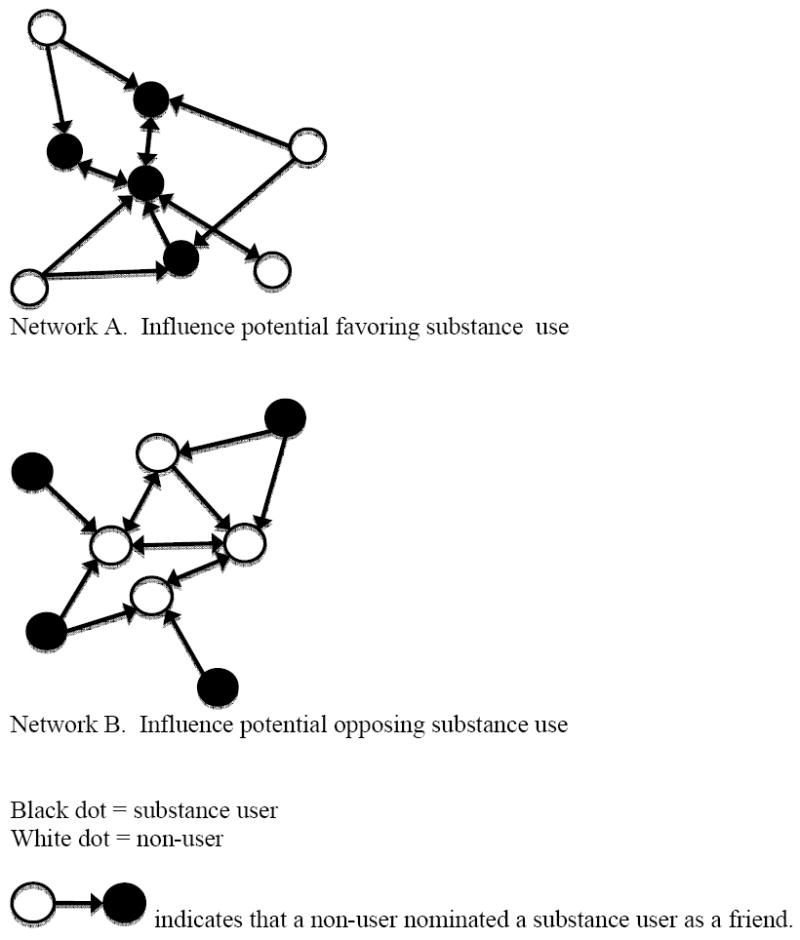

Influence potential can also be conceptualized and measured at the level of the network as a whole. The contribution of a network’s structure to the overall strength and direction of peer influence can be captured through the association (across individuals) between centrality and the behavior of interest. This association provides a measure of the influence potential of the network because it reflects the relationship of the behavior to prominence in the network.7 Thus, in Network A of Figure 2, antisocial influence potential is high because substance users (black nodes) receive more friendship choices than non-users (white nodes), while the reverse is true in Network B. Accordingly, the association between individuals’ network centrality and their problem behavior provides a conceptually grounded and efficient summary of the implications of a social network’s structure for the overall strength of influence toward or away from that behavior, and thus it is a suitable target for preventive interventions.7

Figure 2.

Networks with different antisocial influence potential.

As noted above, many effective preventive interventions, including those implemented in PROSPER, use strategies that may have the potential to shift influence away from antisocial behavior. From a network perspective, if these interventions are effective, antisocial students should come to occupy less influential positions, thus reducing peer influence toward substance use. This network-wide change could be an avenue for generating setting-level benefits5-7,9 in which positive individual-level effects are mutually reinforcing, lead to greater change in the setting as a whole, and diffuse to broader populations.

The PROSPER study research design meets two critical needs for testing the hypothesis that preventive interventions targeting peer influence can affect adolescents’ friendship networks. Most importantly, PROSPER randomly assigned whole school districts to intervention and control conditions, so entire social networks experienced the intervention. Second, PROSPER assessed social networks before and after the intervention. Furthermore, PROSPER’s combination of evidenced-based universal programs, high fidelity of implementation, and demonstrated effects on problem behaviors make this an ideal test case. Prior analyses have revealed that the intervention significantly reduced substance use 1.5 and 5.5 years past the Fall of 6th grade pretest for measures covering a variety of time periods and substances.25,26

METHODS

Sample

The PROSPER prevention study is a randomized control trial conducted in 28 rural and semi-rural public school districts, 14 each in Iowa and Pennsylvania. The study was limited to districts with total enrollments of 1,300 to 5,200 students and at least 15% of families eligible for free or reduced-cost school lunches. The predominant race/ethnicity of all districts was White (61% - 96%). After blocking districts by state, geographic area, and district size, one district of each blocked pair was randomly assigned to receive the intervention and the other to serve as a control. One Iowa intervention school district did not participate in the social network portion of the study, so that school district and its paired control are not included in the present analyses.

Two successive grade cohorts participated in the programs, and both were assessed on five occasions in four years, beginning Fall 2002. The intervention districts implemented a universal family-focused intervention during 6th grade and a universal school-based intervention during 7th grade. Using research procedures approved by the IRBs of Pennsylvania State University and Iowa State University, students and their parents had the opportunity to opt out of each wave of data collection. Research staff administered questionnaires to students in their classrooms in Fall of 6th grade and every Spring through 9th grade. Fall of 6th grade was the only pre-treatment wave; all others were post-baseline. Participation rates ranged from 86% to 90% (across waves) for all eligible students, with an average of 87.2% and about 11,000 students responding each wave. Enrollment in the study was open at each wave, drawing the sample from the entire student body at each occasion.

The social network data derive from questions asking students to name up to two best friends and five additional close friends in their current grade and school, which defines the friendship network as the school and grade cohort combination. Of respondents, 93.9% provided friendship nomination data, and 83.0% of the friends named were successfully matched to the class roster, with means across waves of 4.37 to 4.92 matched names per respondent. Unmatched names resulted from multiple plausible matches for 1.9%, inappropriate choices (e.g., celebrities) for 0.4%, and absence from roster for 14.7%, presumably reflecting friends outside of grade or school.

A single school served each district in 9th grade, and eight districts had multiple schools in some earlier grades (up to seven in 6th grade for one). After excluding eight networks with fewer than 25 students (too few for meaningful analysis), the research design yielded 256 unique post-baseline school-, cohort-, and wave-specific networks, ranging from 78 in 6th grade to 52 in 9th.

The PROSPER Intervention

Each of the school districts randomly assigned to the PROSPER intervention created community-based prevention teams led by a local Cooperative Extension educator, and a school system representative, with additional representation of local mental health and substance use agencies, parents, and youth. (More detailed information on the PROSPER Partnership Model has been published elsewhere.27,28) Each PROSPER team implemented the preventive interventions in both 6th and 7th grades, each time choosing the program from a menu of evidence-based options.

All 14 teams selected the Strengthening Families Program: For Parents and Youth 10-14,4 which research shows to be effective at reducing substance use and other problem behaviors.10,29-32 All parents of 6th grade students were invited to participate, and 17% of families did so. During 7th grade, intervention communities chose one of three similar interventions: the Life Skills Training Program19 (chosen by four), the All Stars Program3 (chosen by six), and Project Alert2 (chosen by four). These programs were delivered to all students in regular 7th grade classes in these communities. These programs have been successful at reducing rates of substance use for adolescents.1,33,34 The core logic of the three programs is more similar than different in that all target social norms, personal goal setting, decision-making, and peer group affiliation, and all share an interactive approach. Independent observations (four per family group; three per classroom) showed consistently high implementation quality, with greater than 90% adherence for both programs in both cohorts.35

Measures

Our primary hypothesis is that the PROSPER intervention will raise the influence potential of prosocial students relative to antisocial students, as reflected in the association between network centrality and antisocial attitudes and behavior. We measure this association with network-specific bivariate regression coefficients that express the mean difference in centrality corresponding to a unit increase in antisocial attitudes or behavior, computed across the students in that network. These regression coefficients, which serve as our outcome measures, describe the structure of each network rather than any causal relationship between these individual-level attributes. These regression coefficients serve as a network-level outcome measure for our test of whether the intervention alters the relationship between prominence in the social network and antisocial behavior.

Social network analysis offers many measures of the centrality of an individual’s network position. Although positively correlated,36 each reflects a different form of influence potential, and we have no convincing basis for prioritizing them. We therefore use six different types of centrality20 to define composite measures. (See supplemental material for formulas for each.) Degree centrality represents the number of friends connected to the individual. Closeness centrality is the mean of inverted distance from others in the network, with distance defined as the minimum number of friendship links required to reach a person. Reach centrality is the number of people connected to the individual, either directly or via a shared friend. Betweenness centrality concerns how often the individual sits on the shortest paths between other adolescents. Bonacich centrality weights the individual’s ties to others by each of those people’s connectedness, while information centrality indicates the individual’s total connectivity with all others in the network. Finally, composite centrality is the mean of standardized versions of the other centrality measures.

We created separate centrality measures based on incoming ties (when another student names the respondent as a friend) versus undirected ties (when either in a pair named the other). Incoming ties correspond to the common view that people will be influenced by the friends they choose. Yet undirected ties might provide superior measures of influence potential because they are more stable and prevalent, yielding centrality measures that tend to be more reliable and better represent the network.37 Bonacich centrality and information centrality could be computed only for undirected ties because incoming ties were too sparse.

Though the metrics of the centrality indices are grounded in network theory, they are ill suited to regression analysis due to skewed distributions, outliers, and having variance dependent on network size. To eliminate these features, we subjected the centrality measures to transformations (presented in the supplemental material). Analyses based on original measures also support our conclusions.

Analyses make use of three separate measures of antisocial attitudes and behavior as well as a composite of those three. The first is a measure of the respondent’s substance use based on responses to questions about smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, getting drunk, and using marijuana in the past month, with response categories ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (more than once a week). These items were combined using the graded response model from item response theory, which translates these discrete and skewed items to an equal-interval scale.38 The second deviance measure reflects attitudes toward substance use, summed across four standardized subscales (anti-use attitudes, expectations for use, refusal intentions, and refusal efficacy) with 22 total questions. Higher scores correspond to attitudes more favorable to substance use. The third measure is a 12 item self-report index of delinquent behavior, also scored with the graded response model. The composite antisocial orientation measure is the mean of standardized versions of the previous three measures. The supplemental material includes the full text of these measures.

The 12 measures of network centrality and 4 measures of antisocial orientation yield 48 versions of our measure of antisocial influence potential. To minimize concerns about multiple significance testing, we focus on the versions based on composite measures of both, which provide the best overall test of the hypothesized program effect.

Plan of analysis

We assess program impact on antisocial influence potential through multi-level regression models. The dependent variables reflect the dependence of centrality on problem behavior in a school grade cohort in a single wave (level 1). These repeated measures are nested within schools (level 2), which are nested in school districts (level 3), which are nested within the pairs of random assignment (level 4). In addition to random intercept terms that allow for variation at all four levels, we allow for cohort differences through a random coefficient at the district level (centered within district, no fixed coefficient). Level 1 variance includes measurement error variance indicated by network-specific standard errors (varying vary due to number of students and variance of measures). The model allows for mean change over time by controlling for wave as a categorical variable. All models were estimated through the MLwiN program, using restricted maximum likelihood via iterative generalized least squares.39

In this randomized control trial, control variables are not needed to reduce bias in estimates of intervention effects, but they might increase statistical power. Supplemental analyses revealed that controlling for state, network size (a quadratic function of log size), and pretest measures yielded essentially identical results, with no increase in power (see supplement).

Pretest analyses demonstrated that intervention and control school districts originally differed by no more than chance on antisocial influence potential (z = .74, p = .46 and z = .11, p = .92 for undirected and incoming composite centrality with composite antisocial orientation). Across 48 versions of our outcome measure, the mean intervention versus control difference was opposite to the hypothesized program effect, and only one pretest difference reached p < .05. Thus, the random assignment procedures succeeded in producing groups that were equivalent at baseline. (Full results appear in the supplemental material.)

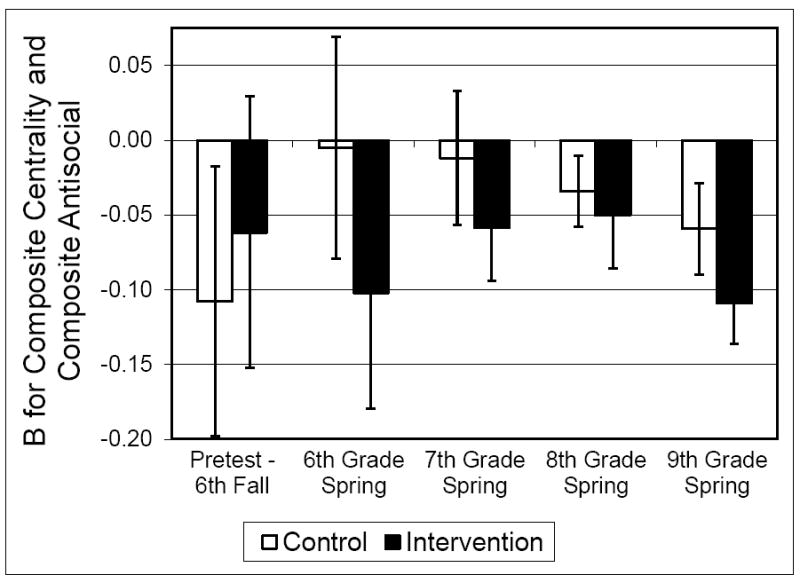

RESULTS

Analyses reveal that the PROSPER intervention significantly reduced antisocial influence potential in adolescents’ friendship networks (B = -.052, z = -2.70, p = .007 for composite undirected centrality and B = -.031, z = -1.97, p = .049 for composite incoming centrality). The negative estimates reflect that, as hypothesized, antisocial youth tended to be less central than other youth in intervention communities than in control communities. Figure 3 illustrates intervention effects for the relationship of composite undirected centrality to composite antisocial orientation. The negative means for both groups across all waves indicate that, overall, antisocial attitudes and behavior were associated with slightly lower centrality. At the pretest, however, antisocial youth were somewhat less central in control than in intervention school districts, but this pattern reversed for all post-intervention assessments. The confidence bands show that differences between intervention and control groups were imprecise at any one wave, so power was insufficient to detect change in intervention effects over time. Nonetheless, the significant overall intervention effect indicates a statistically reliable overall intervention effect of reduced influence potential of antisocial adolescents.

Figure 3.

Intervention and control means over time for the association of composite undirected centrality with composite antisocial orientation.

Results were largely consistent across the 48 combinations of measures of centrality and measures of antisocial orientation. Program effect estimates were in the hypothesized direction for 47 of 48 measures of antisocial influence potential, with p < .05 for 26, and p < .10 for 4 more. Effect sizes for the significant effects were small, ranging from -.027 to -.079 in the metric of regression coefficients standardized using sample-wide individual-level standard deviations. Note that these values would be roughly twice as large in the typical metric of Cohen’s d. Mean effect sizes were stronger for measures based on undirected friendship ties than incoming ties (-.040 versus -.021), stronger for Bonacich centrality (-.061), and weaker for betweenness centrality (-.009). The supplemental material includes results for all 48 combinations.

DISCUSSION

These findings demonstrate a beneficial effect on adolescent social networks from a universal intervention to prevent substance use. In school districts randomly assigned to the PROSPER intervention, students’ friendship networks changed in a way that should reduce diffusion of problem behaviors, relative to control districts. Influence potential shifted away from adolescents who engaged in problem behavior or held attitudes favoring substance use and toward adolescents who did not. These setting-level effects hold promise for enlarging the benefit of preventive interventions by altering interpersonal influence processes to extend impact beyond the individuals initially most affected. Such setting-level effects have the potential to engender beneficial peer influence that reinforces and maintains initial intervention effects on individual attitudes and behavior.5,6

Intervention effects most consistently reached statistical significance for composite measures and for centrality measures based on all friendship ties (either to or from an adolescent) rather than only incoming ties (being chosen as a friend). We believe this pattern reflects the greater reliability of indices that aggregate the most information. Differences in results across measures are no more than suggestive because few if any differences in effect size would be statistically significant.

These intervention effects on social networks could help account for the PROSPER intervention’s enduring success in reducing substance use and for the impact of family-based interventions observed for youth whose families did not participate in the intervention.10 At present, it is not possible to compute a specific reduction in the rate of problem behavior that would follow from these intervention effects on networks. Social networks are complex systems with highly endogenous selection and influence processes, so estimating the consequences on behavior would require simulations that integrate estimates of intervention impact with a realistic model of network evolution. Also, future research should study our topic using more diverse populations and including friendships with older students, who could be a potent influence on problem behavior.

The present study shows that existing preventive interventions alter social networks in ways that should enhance the interventions’ capacity to reduce problem behavior. These promising findings suggest that program developers look to the burgeoning research on adolescent friendship networks for means to achieve greater impact. Current programs target influence and selection processes that affect social networks from an individualistic perspective, such as providing training in skills for resisting influence attempts and giving advice about choosing friends. As our knowledge of network processes grows, it will provide program developers with a larger set of tools for designing programs that not only benefit individual students, but also reshape social systems to sustain and diffuse program benefits.

Supplementary Material

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Our results show that the PROSPER evidence based preventive interventions alter adolescents’ friendship networks in ways that reduce the potential for peer influence toward problem behaviors such as substance use and delinquency. This network-wide change could be an avenue for generating setting-level benefits that increase the reach and duration of intervention benefits.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Susan Ennett for valuable comments on an earlier draft, Sonja Siennick and April Woolnough for assistance with data analysis, and Lauren Molloy for assistance with figures. Analyses of the friendship network data are supported by grants from the W.T. Grant Foundation (8316) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1-DA08225), and the PROSPER intervention study is supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (RO1-DA013709).

Footnotes

An earlier version of this work was presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Prevention Research, Denver, CO, June 2010.

Contributor Information

D. Wayne Osgood, Crime, Law and Justice Program, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University.

Mark E. Feinberg, Prevention Center, Pennsylvania State University.

Scott D. Gest, Prevention Center and the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University.

James Moody, Department of Sociology, Duke University.

Daniel T. Ragan, Crime, Law and Justice Program, Department of Sociology, Pennsylvania State University.

Richard Spoth, Partnerships in Prevention Science Institute, Iowa State University.

Mark Greenberg, Prevention Center and the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, Pennsylvania State University.

Cleve Redmond, Partnerships in Prevention Science Institute, Iowa State University.

References

- 1.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW. Life Skills Training: Empirical Findings and Future Directions. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2004;25(2):211–232. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellickson P, Miller L, Robyn A, Wildflower L, Zellman G. Project Alert. Best Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansen WB, Dusenbury L. All Stars Plus: A competence and motivation enhancement approach to prevention. Health Education. 2004;104(6):371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molgaard V, Kumpfer K, Fleming E. Strenghtening Families Program. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Research Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seidman E. An action science of social setting. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;50(1-2):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng V, Seidman E. A systems framework for understanding social settings. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;39(3-4):217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gest SD, Osgood DW, Feinberg M, Bierman KL, Moody J. Strengthening Prevention Program Theories and Evaluations: Contributions from Social Network Analysis. Prevention Science. 2011;12(4):349–360. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0229-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Valente TW. Network interventions. Science. 2012 Jul 6;337(6090):49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1217330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valente TW. Social Networks and Health : Models, Methods, and Applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Azevedo K. Brief Family Intervention Effects on Adolescent Substance Initiation: School-Level Growth Curve Analyses 6 Years Following Baseline. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):535–542. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burgess RL, Akers RL. A Differential Association-Reinforcement Theory of Criminal Behavior. Social Problems. 1966;14(2):128–147. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oetting ER, Beauvais F. Peer cluster theory: Drugs and the adolescent. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1986;65(1):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patterson GR. Performance models for antisocial boys. American Psychologist. 1986;41(4):432–444. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Gest SD, Gariépy J-L. Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology. 1988;24(6):815–823. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dishion TJ, Eddy JM, Haas E, Li F, Spracklen K. Friendships and Violent Behavior During Adolescence. Social Development. 1997;6(2):207–223. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Menard SW. Multiple Problem Youth : Delinquency, Substance Use, and Mental Health Problems. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Hussong A, et al. The Peer Context of Adolescent Substance Use: Findings from Social Network Analysis. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(2):159–186. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Drug Abuse Prevention Among Minority Adolescents: Posttest and One-Year Follow-Up of a School-Based Preventive Intervention. Prevention Science. 2001;2(1):1–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010025311161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botvin GJ. Life Skills Training Program. Princeton: Princeton Health Press, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasserman S, Faust K. Social Network Analysis : Methods and Applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification. Social Networks. 1979;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bearman PS, Moody J. Suicide and Friendships Among American Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:89–95. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.1.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ennett ST, Bauman KE. Peer group structure and adolescent cigarette smoking: A social network analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34(3):226–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haynie DL. Delinquent peers revisited: Does network structure matter? American Journal of Sociology. 2001;106(4):1013–1057. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Greenberg M, Clair S, Feinberg M. Substance-Use Outcomes at 18 Months Past Baseline: The PROSPER Community-University Partnership Trial. American Journal of Preventative Medicine May. 2007;32(5):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spoth RL, Randall GK, Trudeau L, Shin C, Redmond C. Substance use outcomes 5 1/2 years past baseline for partnership-based, family-school preventative interventions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008 Jul 1;96(1-2):57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spoth R, Greenberg M, Bierman K, Redmond C. PROSPER community-university partnership model for public education systems: capacity-building for evidence-based, competence-building prevention. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):31–39. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013979.52796.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spoth R, Greenberg M. Impact challenges in community science-with-practice: Lessons from PROSPER on transformative practitioner-scientist partnerships and prevention infrastructure development. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(1-2):106–119. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spoth R, Guyll M, Trudeau L, Goldberg-Lillehoj C. Two studies of proximal outcomes and implementation quality of universal preventive interventions in a community-university collaboration context. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(5):499–518. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spoth R, Redmond C, Shin C, Lepper H, Haggerty K, Wall M. Risk moderation of parent and child outcomes in a preventive intervention: A test and replication. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):565–579. doi: 10.1037/h0080365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lillehoj CJ, Trudeau L, Spoth R, Wickrama KAS. Internalizing, Social Competence, and Substance Initiation: Influence of Gender Moderation and a Preventive Intervention. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39(6):963–991. doi: 10.1081/ja-120030895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spoth R, Trudeau L, Guyll M, Shin C, Redmond C. Universal intervention effects on substance use among young adults mediated by delayed adolescent substance initiation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(4):620–632. doi: 10.1037/a0016029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Drug Prevention in Junior High: A Multi-site Longitudinal Test. Science. 1990;247(4948):1299–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.2180065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNeal RB, Hansen WB, Harrington NG, Giles SM. How all Stars Works: An Examination of Program Effects on Mediating Variables. Health Education and Behavior. 2004;31(2):165–178. doi: 10.1177/1090198103259852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spoth R, Guyll M, Lillehoj CJ, Redmond C, Greenberg M. PROSPER study of evidence-based intervention implementation quality by community-university partnerships. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35(8):981–999. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Valente TW, Coronges K, Lakon C, Costenbader E. How Correlated are Network Centrality Measures? Connect. 2008;28(1):16–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butts CT. Network inference, error, and informant (in)accuracy: a Bayesian approach. Social Networks. 2003;25(2):103–140. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osgood DW, McMorris BJ, Potenza MT. Analyzing Multiple-Item Measures of Crime and Deviance I: Item Response Theory Scaling. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 2002;18(3):267–296. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasbash J, Steele F, Browne WJ, Goldstein H. A User’s Guide to MLwiN, Version 2.10. Bristol, UK: Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.