Abstract

Objectives

To examine barriers community health centers (CHCs) face in using workers' compensation insurance (WC).

Data Sources/Study Setting

Leadership of CHCs in Massachusetts.

Study Design

We used purposeful snowball sampling of CHC leaders for in-depth exploration of reimbursement policies and practices, experiences with WC, and decisions about using WC. We quantified the prevalence of perceived barriers to using WC through a mail survey of all CHCs in Massachusetts.

Data Collection/Extraction Methods

Emergent coding was used to elaborate themes and processes related to use of WC. Numbers and percentages of survey responses were calculated.

Principal Findings

Few CHCs formally discourage use of WC, but underutilization emerged as a major issue: “We see an awful lot of work-related injury, and I would say that most of it doesn't go through workers' comp.” Barriers include lack of familiarity with WC, uncertainty about work-relatedness, and reliance on patients to identify work-relatedness of their conditions. Reimbursement delays and denials lead patients and CHCs to absorb costs of services.

Conclusion

Follow-up studies should fully characterize barriers to CHC use of WC and experiences in other states to guide system changes in CHCs and WC agencies. Education should target CHC staff and workers about WC.

Keywords: Workers compensation, community health center, work-related injuries and illnesses, medical insurance

The appropriate use of workers' compensation (WC) insurance has importance for access to care, health care resources, and public health. WC can be particularly useful for community health centers (CHCs) that provide care to low-income workers, who are disproportionately employed in high-risk jobs (Baron and Sacoby 2011). However, experience suggests that Massachusetts CHCs face significant obstacles to its use. In this study, we use qualitative and quantitative approaches to describe barriers Massachusetts CHCs face in using WC.

Workers' Compensation Insurance

WC is designed to reimburse medical care and related services for work-related injuries and illnesses (WRII). WC reimburses more than general medical insurance, covering needs such as medications and transportation, with no co-payments or deductibles. WC also covers expenses such as rehabilitation or partial replacement of wages lost due to work-related conditions (McGrail et al. 2002). Such coverage is especially vital for low-wage, immigrant, and other vulnerable workers, who often work in hazardous environments yet can face the greatest barriers to health care (Lashuay and Harrison 2006; Dong et al. 2007; Premji and Krause 2010). Underutilization of WC can result in lack of necessary care, delays in treatment (Day et al. 2010), unreimbursed patient bills, and inability to take time away from work for treatment and recovery.

By covering care for workers without adequate health insurance, WC prevents inappropriate charges to Medicaid, Medicare, other insurance, and unreimbursed care (Leigh and Robbins 2004; Fan et al. 2006; Won and Dembe 2006; Lipscomb et al. 2009). WC claims also provide unique public health data key to identifying and preventing occupational hazards and WRII. Finally, WC claims are some of the few forms of feedback to individual employers enabling them to identify and correct workplace hazards (Herbert et al. 1997; Burgel et al. 2004; Boden and Ozonoff 2008; Dembe 2010; Du and Leigh 2011; Leigh and Marcin 2012; Utterback et al. 2012).

Barriers to Workers' Compensation

Studies suggest that 25–55 percent of costs of care for WRII are shifted away from WC for all eligible cases (Leigh and Robbins 2004; Fan et al. 2006; Rosenman et al. 2006; Won and Dembe 2006; Lakdawalla, Reville, and Seabury 2007; Boden and Ozonoff 2008; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2010; Luckhaupt and Calvert 2010; Premji and Krause 2010; Leigh and Marcin 2012), rising to 75–95 percent for selected conditions or populations (Herbert et al. 1997; Milton et al. 1998; Morse et al. 1998; Azaroff, Levenstein, and Wegman 2004; Burgel et al. 2004; Dong et al. 2007; Bernhardt et al. 2009; Luckhaupt and Calvert 2010; Rosenman et al. 2010).

Barriers to WC from the patient perspective have been characterized, with vulnerable and minority workers most affected (Brown, Domenzain, and Villoria-Siegert 2002; Azaroff, Levenstein, and Wegman 2004; Fan et al. 2006; Lashuay and Harrison 2006; Massachusetts Department of Public Health Occupational Health Surveillance Program [OHSP] 2007); Bernhardt et al. 2009; Lipscomb et al. 2009; U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO] 2009; American Public Health Association [APHA] 2010; Luckhaupt and Calvert 2010.

Barriers to WC from the provider perspective include providers' lack of familiarity with the system, delays, denials, “overwhelming” paperwork (Lax and Manetti 2001; Woodcock and Neely 2005; Lax 2010), administrative hassles (Weber 2007; Ortolon 2008), and concerns about litigation, confidentiality, conflicts, and lack of time and resources for obtaining WC reimbursement (Himmelstein and Rest 1996; Himmelstein et al. 1999; Lippel 1999; Lax and Manetti 2001; McGrail et al. 2002; Pransky et al. 2002; Atlas et al. 2004; Beardwood, Kirsh, and Clark 2005; Lashuay and Harrison 2006). “Insurance-induced limbo” (Himmelstein and Rest 1996), in which WC denies claims and other insurers refuse payment because a condition was identified as work related, can leave patients without care or responsible for the bills (Lipscomb et al. 2009). Excepting acute traumatic injuries, the identification of work as causing or exacerbating a condition is necessary for WC, but most U.S. physicians receive insufficient training in diagnosing WRII (Burstein and Levy 1994; Michas and Iacono 2008).

Workers' Compensation and Community Health Centers

Community health centers (CHCs) focus on vulnerable populations, including the low-income and uninsured (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care [HRSA] 2008). CHCs serve 20 million patients at 7,000 sites nationwide, including more than 760,000 in Massachusetts (Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers 2010). WRII are often seen in primary care settings such as CHCs (Atlas et al. 2004; Won and Dembe 2006). A 2005 survey of patients in five Massachusetts CHCs found 20 percent had conditions in the previous year they thought were caused by their jobs (OHSP 2007).

Lashuay and Harrison surveyed 11 community-based clinics in California and found that less than half routinely filed WC reports due to barriers, including patient fear of reprisals, lack of WC coverage for informal employment, and employer refusal to recognize the WRII (Lashuay and Harrison 2006). We learned of a Massachusetts CHC where 65 cases over 2 years were diagnosed as work related, but none were charged to WC. Another had approximately 81,000 adult visits over 1 year with none charged to WC, although many of the patients are employed in hazardous industries (OHSP 2007). To explore barriers to use of WC faced by CHCs in Massachusetts, we conducted in-depth interviews and a survey of CHC leaders.

Methods

In-Depth Interviews

Confidential telephone interviews were conducted with administrators and providers from eight CHCs. We used purposeful snowball sampling to select leaders identified by their peers as likely to discuss this topic thoughtfully with researchers (Noy 2008). Our goals were in-depth exploration of potentially sensitive processes rather than representativeness, so we did not select participants based on CHC characteristics. (We did include a CHC from each major region of Massachusetts given striking geographic variability in economics and health care.) Interviews were semi-structured: respondents were asked a list of questions (Appendix SA2) and the interviewer probed for additional information. The interviewer typed notes during the interview.

Questions addressed CHC reimbursement policies and practices for using WC, experiences with WC, identification of WC cases, staff and provider decisions about using WC, and changes that could facilitate WC use.

Responses to interviews were reviewed and grouped according to emergent themes.

CHC Survey

An anonymous mail survey was conducted to assess the representativeness of issues described in the interviews. We included all 76 sites of 56 CHCs in Massachusetts, targeting medical directors and chief financial officers. Questions addressed current and previous WC use, perceived importance of selected factors in discouraging WC use, and types of educational materials needed (Appendix SA3). Responses were Not at all, A little, Somewhat, Very Much, and Don't Know. Questionnaires were coded to identify multiple responses from any site. Respondents self-identified as “Medical Director,” “Chief Financial Officer,” or “Other.”

The study, conducted in 2009, was approved by the Institutional Review Board for the Protection of Human Subjects at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health.

Results

Responses

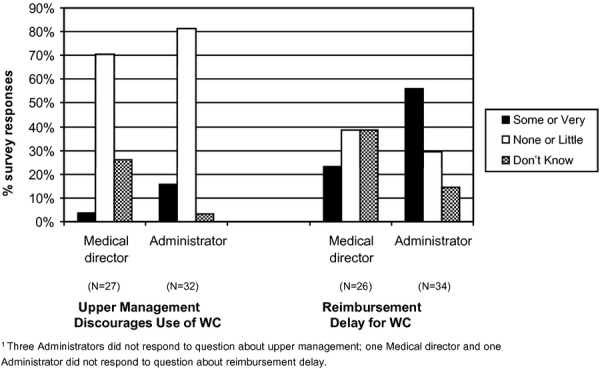

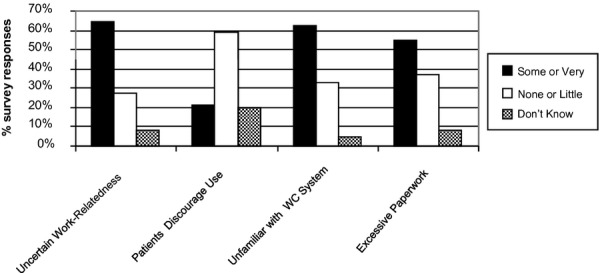

Ten respondents (including three physicians, one certified in occupational and environmental medicine) from eight CHCs participated in in-depth interviews. CHC survey questionnaires were returned by 56 of 76 CHC sites (74 percent). Survey respondents included 27 medical directors (MDs) or associate medical directors from 25 sites and 35 administrators from 32 sites. Survey results for MDs and administrators are presented separately when they differed (Figure 1) and combined when similar (Figure 2). Findings are grouped by themes and results presented within theme, first the results of the in-depth interviews followed by a summary of survey findings.

Figure 1.

Factors Discouraging Use of Workers' Compensation (WC) at Community Health Centres by Type of Survey Respondent

Figure 2.

Factors Discouraging Use of Workers' Compensation (WC) at Community Health Centres, All Survey Respondent (N = 62)

Policies Regarding Use of WC

Almost all interviewees indicated that their CHCs have no policy against using WC and are willing to do so if requested. One physician explained, “We've never been told by our financial people, try not to bill that way, it's a pain in the neck or anything.”

An exception was one who said that, after years of delays and denials in getting reimbursed by WC, this CHC's staff were told to send WC cases to a local emergency department rather than register them there.

Survey responses supported this finding, with 91 percent of CHCs accepting WC cases, just three saying they did not and two answering “don't know.” Only 10 percent responded that their upper-level management discourages use of WC “very much” (5 percent) or “somewhat” (5 percent), whereas 69 percent reported that their upper-level management discourages use of WC “not at all.” Notably, administrators were somewhat more likely than MDs to report discouragement by upper management (Figure 1).

Identification of Work-Relatedness

Interviewees from five CHCs described a reliance on the patient to volunteer that a condition is work-related at registration or to respond positively on a registration form to a question: “Is today's visit due to a work-related injury?” One of these, however, indicated that their registration staff is trained to ask patients about the time and place where an injury occurred.

Four noted that work-relatedness would not be identified if not documented at registration: “… if the desk doesn't catch it, the provider isn't likely to.”

Three interviewees said that providers at their CHCs do identify work-related conditions, but only if patients describe them as such during appointments. One reported that providers sometimes identify work-relatedness proactively: “We're aware to ask questions about work-related injuries and illnesses because our patients… the most common occupation is janitor… it's pretty common that people get hurt.”

The occupational medicine physician interviewed argued that identifying work-relatedness should be the responsibility of the provider, but that lack of occupational medicine training for primary care providers is a major obstacle.

Survey findings underscored the challenges of diagnosing work-related conditions. Sixty-five percent of respondents reported that uncertainty about work-relatedness discourages their CHCs' use of WC, 18 percent “very much (Figure 2).”

Three survey respondents also wrote comments reflecting reliance on patients to identify work-relatedness at registration, for example, “Often patients don't know they need to tell registration staff it is a work injury. More often than not we are billing personal insurance in error because of this fact.”

Administrative Obstacles to Use of WC by Massachusetts CHCs

Decision to Bill WC

Interviews indicate that translating a determination of work-relatedness into a decision to bill WC is influenced by a number of factors. If a patient identifies a condition as work-related while registering, respondents said that staff usually bill WC. Some added that patients have to provide the information on their employer's WC policy, whereas others have staff contact employers. Policy at one CHC registers the visit as self-pay and bills patients while obtaining the claim number from the employer. They rely on the patient to refuse to pay these bills; “we assume that the patient would have to know what they're entitled to.”

One physician explained that billing WC, not only identifying work-relatedness, is left up to the patient at that CHC: “if the patient initiates it we would go along, we may not be the ones to actually think about it.”

The nature of the patient's condition or financial consequences of cost-shifting can affect a CHC's decision. One physician explained that when patients cannot get coverage for needed physical therapy through other insurance, or when faced with high deductibles or copayments, “if it's a financial burden to the patient to use their own insurance… then we would try to use comp.” Others described billing WC only if work-relatedness is “very obvious” (such as injuries from falling off a ladder) or “in the case of more serious [injuries], time off, litigation, etc.”

Three interviews indicated some administrators' general lack of awareness about WC. A director of billing said companies with just a couple of employees would probably not carry WC because they are “too small” to be required to carry WC. (Massachusetts law requires employers with one or more employees to carry WC.) Several respondents were unable to name any advantages for the patient to billing WC rather than other forms of coverage.

Patients' fears of job loss or financial loss for reporting a WRII also discourage billing. “We sometimes have patients coming in, when we ask them if they have reported to their company, they say, ‘oh no, I can't do that,’ they have reluctance to inform HR or someone at work.” “If the patient is apprehensive about giving you all the information you need, because of the nature of the injury, you run into all sorts of barriers in attempting to get WC done.” In the patient's mind, “they are going to get money from the source that also supplies them a job to work, so they feel that they are in a situation where it may not be an advantage to them.” “They're thinking, ‘what's going to happen’ about their job.”

An interviewee added that some patients do not use WC because they are undocumented. In addition, patients are sometimes afraid to pursue a claim that is initially rejected by a WC carrier, thinking they will not prevail.

A provider reported feeling “struck by the number of workers who continue to work in pain… whose conditions worsen,” and “with illnesses that continue to put them at risk for irreversible impacts” due to worry of losing their job.

Survey results did not show this concern to be very representative: just 21 percent of respondents indicated that patients themselves “very much” (5 percent) or “somewhat” (16 percent) discourage use of WC (Figure 2).

However, the survey did find that lack of familiarity with the WC system is a prevalent barrier to translating identification of work-relatedness to a WC claim (Figure 2). Most respondents reported that lack of familiarity with WC system discourages their CHCs' use of WC “very much” (32 percent) or “somewhat” (29 percent). Survey respondents wrote additional comments: “Confusion regarding patients with routine medical issues who also have work-related injury—should I write 2 notes?” Another simply wrote, “Confusion.”

Disconnect in the Workflow

Four interviews indicated that when conditions are first diagnosed as work-related by the provider (i.e., after registration), few mechanisms exist to notify the CHC staff to bill WC.

Administrators at one CHC identified some providers who e-mail patients' employers when the patients are found to have a WRII. When this happens, the CHC charges the care to WC. A physician explained that providers can send the patient to the financial department for information on how to bill. Other interviewees explained that providers would not normally inform the patient's employer, billing staff, or other staff about work-relatedness. Even the provider who described asking patients about WRII related to their cleaning jobs reported that the CHC would be unlikely to bill WC if the patient had not identified work-relatedness at registration.

One explained, “the doctor has nothing to do with the insurance piece,” he or she is worrying about taking care of the patient, not about how the patient gets billed or “how the bill goes out the door.” “They'd be more concerned if they were in a private practice,” but “here it doesn't matter.”

Data systems are also structured to avoid provider involvement in billing: “our encounter forms say what it is, not how it gets billed.” One explained that the most common WRII seen are strain injuries, which are coded as the specific diagnoses (e.g., back strain, carpal tunnel syndrome), and billed to regular insurance. Another interviewee explained that administrators at that CHC do not want providers to get involved in reimbursement because they sometimes misinform patients, for example, mistakenly telling them that their insurance will cover a procedure.

Interviewees clarified that medical records staff have nothing to do with billing and would not notify billing staff about work-relatedness noted in a record.

Work Involved in Billing WC

Interviewees from three CHCs described demands for additional paperwork and information in billing WC. These demands are repeated at multiple steps throughout the process: contact between the CHC and the patient's employer, communication between the employer and the insurer, submitting bills to the insurer, responding to the insurer's inquiries, responding to an insurer's denials, and referring patients to specialists. An administrator stated, “The system is very complicated compared to billing a normal health insurance company, it's cumbersome.” Each case has to be examined and processed individually rather than being submitted in batches. A physician stated, “It's invariably a huge amount of work for the provider.”

Several interviewees reported that obtaining information from employers is a major obstacle. They explained that this distinguishes WC from other forms of insurance: a regular insurance card contains the necessary information, but for WC, the patient usually has to obtain additional information from the employer. “The big thing is gathering all the information.” “It can be a big process in order to get paid.” Administrators from one CHC added, “we have struggled with this for years.”

One interviewee stated, “In order to submit any bill, you need to do paperwork, but then with comp you have to fill out more forms about when the patient should go out of work, when they should go back to work. It always ends up filtering back to 20 e-mails.” Another explained: “There's a lot of paper work, often they send it again, they need to hear it in a certain way.”

Interviewees stressed that most CHC patients have multiple health issues, further complicating the use of WC: “Invariably I'm seeing people with chronic issues like diabetes, high blood pressure, then they fall at work, I can't see them for both or the comp carrier would deny the claim.” “If a patient has an ankle injury due to work, I'm supposed to ignore chronic problems; they have to come back for another visit. Sometimes I'm seeing a patient for the ankle they hurt at work, but they come back for a diabetes check, so even though I'm seeing them for something unrelated to workers' comp, it's hard to get billing to do this… They get registered under comp until the claim closes they get put in as a certain insurance package. Their record will say across the top ‘industrial accident,’ then you have to go out to the front desk, say, no, I'm seeing him for diabetes.” This respondent confirmed that this type of situation happens frequently.

The occupational medicine physician confirmed that providers need to be clear about dates of service for work-related versus non-work-related issues and “absolutely” need to write two notes. Another provider explained that the complications of documenting work-related and other conditions separately results in cost-shifting to the CHC: “We're stuck choosing to deny half of the care that we provided. Otherwise the patient gets the bill, which is a total disaster.”

Survey findings likewise highlighted the paperwork burden. Fifty-five percent of respondents reported that excessive paperwork “very much” (34 percent) or “somewhat” (21 percent) discourages their CHC's use of WC (Figure 2).

Delays and Denial of Payment by WC Insurers

Delays in reimbursement by WC carriers were emphasized as a barrier by six administrators interviewed from four CHCs. One reported previously learning in a private practice that WC is a “really slow payer.” Another administrator said WC claims “take forever,” and specified that this CHC's wait for reimbursement was 6 months to a year, “much longer than other forms of insurance,” which one respondent said takes 45 days to reimburse. Delays in reimbursement were cited as the principal reason for no longer accepting WC cases by the one responding CHC that does not bill WC.

One interviewee explained that “the disadvantages are pretty big”: for patients facing delays in reimbursement, as they have to spend their own money while expenses are processed.

WC payers often deny coverage altogether. One interviewee stated that the CHC's claims to WC are “more frequently denied than paid.”

Respondents from three CHCs confirmed that if WC denies a claim, other forms of insurance then refuse to pay.

Interviews suggested that CHCs' commitment to patient care means that delays and denials in WC payment do not typically result in withholding of necessary care, but rather in cost-shifting, billing the patient or losses for the CHC. However, one physician reported delays in care and recovery resulting from obstruction by WC insurers.

Survey findings showed delayed reimbursement is an issue for most administrators, with 37 percent of administrators reporting that delays in reimbursement “very much,” and 17 percent reporting that delays “somewhat,” discourage use of WC. Only 22 percent of medical directors noted this as a problem but 37 percent replied “don't know” (Figure 1). Survey results regarding denials were similar.

Discussion

This study sought to describe barriers to use of WC by Massachusetts CHCs. Interviews explored underlying processes, whereas surveys estimated the prevalence of certain obstacles.

Our findings add to evidence from California on underutilization of WC by CHCs (Lashuay and Harrison 2006). Results indicate that, although few Massachusetts CHCs refuse WC cases and few CHC leaders discourage use of WC, default practices favor charging other forms of coverage. One interviewee explained: “We see an awful lot of work-related injury, and I would say that most of it doesn't go through workers' comp.”

A striking finding is that, for WC to be used, patients typically must identify their conditions as work-related when they register, and request, or at least agree to, billing their employers' WC carriers. If work-relatedness is identified by the patient or provider only during an appointment, some CHCs lack mechanisms to communicate this to billing staff, who therefore charge non-WC forms of coverage.

Relying on patients to self-diagnose WRII is likely to lead to underutilization of WC. While patients know when traumatic injuries happen at work, they cannot be expected to recognize the link of work to illnesses, such as asthma or chronic musculoskeletal disorders, the types of conditions more commonly seen in CHCs (OHSP 2007).

Moreover, once WC is charged, delays and denials of reimbursement can lead to patients themselves being billed or CHCs absorbing the costs of services. CHC administrators were more likely than medical directors to report denials and delays as problematic, consistent with their distinct roles and with other studies about their different perspectives (Mimiaga et al. 2011). Administrators and providers alike described excessive paperwork involved in WC.

These obstacles mean that CHCs have little incentive to encourage providers to identify and report back to billing that a condition is work related. Exceptions occur when WC is recognized to relieve patients of high deductibles or other uncovered costs associated with general medical insurance.

We found some lack of knowledge on the part of CHCs about WC and its potential advantages for patients. Participants also revealed confusion about using the WC system effectively, for example, how to identify and adequately document work-related health problems.

The emphasis on ensuring that patients receive care independent of their ability to pay can create a dilemma for CHCs. Appropriate billing of WC can enable patients to receive the benefits and services that they are entitled to and may be critical to their long-term recovery. On the other hand, delays and denials in reimbursement by WC strain the finances of CHCs and can leave patients responsible for the bills or even going without needed care, consistent with the “insurance-induced limbo” described previously (Himmelstein and Rest 1996). Such concerns may lead CHCs to bill another type of insurance or public program.

Patient hesitancy to use the WC system has been documented in numerous studies and likely reflects a combination of factors, including patient lack of awareness about WC, prior experience with the system, and fear of job loss or other negative consequences.

Our findings are consistent with results from a 2008 survey of medical providers in the state conducted by authors D. Hashimoto and R. Naparstek with the Massachusetts Medical Society (MMS) (Health Policy Department, spring 2008). An email survey of 1,236 MMS members living in Massachusetts with email address on file targeted the 18 specialties likely to treat patients with WRII. Of the 124 responses, 51 percent reported that they currently accept WC patients and 12 percent reported that they used to, but no longer do so. Excessive paperwork was reported by 51 percent of physicians currently accepting WC patients and by 73 percent of physicians no longer accepting WC patients. Half of those currently accepting WC patients and two thirds of those no longer accepting such patients reported delays in reimbursement by WC “often” or “always.” Furthermore, half of the respondents reported “often” or “always” experiencing delays in recommended patient care for WC patient claims. Denial of WC for patients considered by their physicians to be eligible was a problem “often” or “always” for one fourth of physicians accepting WC patients and over 40 percent of those no longer accepting WC patients. Finally, more than one third of physicians who currently or previously accepted WC patients reported they “often” or “always” experienced denials in recommended patient care for their patients.

While low reimbursement rates were a major factor discouraging WC use among the physicians surveyed by MMS, this rarely arose as an issue in CHC interviews or surveys. This difference may reflect a discrepancy in WC reimbursement rates. WC rates for CHCs are comparable with rates for Medicaid (Eccleston et al. 2002; Zuckerman, Williams, and Stockley 2009), which reimburses large proportions of other CHC services (Takach 2008). For non-CHC physicians, however, WC rates in Massachusetts are among the lowest in the United States (Eccleston and Liu 2006).

Study findings underscore the need for:

Further research documenting denials, delays, and other barriers within the WC system itself and steps to address these barriers.

Educational initiatives about the WC system and how to use it, targeting administrators and other CHC support staff as well as providers and workers.

Innovative strategies to provide occupational health support, for example, clinical decision support tools, consultation, to CHC primary care providers

Systems changes within CHCs and other resources for CHCs to address barriers in work flow.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include a lack of direct data about work-related cases and WC claims. In addition, our experiences with CHCs indicate wide variability in approaches to WC, and the eight who provided in-depth interviews may or may not be representative of CHCs statewide. WC systems are state specific, and the results reported here are relevant only to Massachusetts and the state's CHCs. These findings suggest the need for follow-up studies to fully characterize barriers to CHC use of WC across states as well as critical differences among states. With this evidence proposals can be developed for system changes at both CHC and WC agency levels and for educational materials and programs to inform providers about WC and workers of their rights.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: This study was funded in part through a Cooperative Agreement between the CDC-National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH): U60/OH008490. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC-NIOSH.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Appendix SA2: Exploring Barriers to Use of Workers' Compensation at Massachusetts Community Health Centers Key Informant Interview Questions.

Appendix SA3: Anonymous Survey on Workers' Compensation Insurance and Massachusetts Community Health Centers.

References

- American Public Health Association [APHA] “Workers' Compensation Reform Policy”. New Solutions. 2010;20(3):397–404. doi: 10.2190/NS.20.3.l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas SJ, Wasiak R, Webster M, van den Ancker B, Pransky G. “Primary Care Involvement and Outcomes of Care in Patients with a Workers' Compensation Claim for Back Pain”. Spine. 2004;29(9):1041–8. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200405010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azaroff LS, Levenstein C, Wegman DH. “The Occupational Health of Southeast Asians in Lowell: A Descriptive Study”. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 2004;10(1):47–54. doi: 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron S, Sacoby W. “Occupational and Environmental Health Equity and Social Justice”. In: Levy BL, Wegman DH, Baron SL, Sokas RK, editors. Occupational and Environmental Health, Recognizing and Preventing Disease and Injury. 6th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 69–97. [Google Scholar]

- Beardwood BA, Kirsh B, Clark NJ. “Victims Twice over: Perceptions and Experiences of Injured Workers”. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(1):30–48. doi: 10.1177/1049732304268716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt A, Milkman R, Theodore N, Heckathorn D, Auer M, DeFilippis J, Gonzalez AL, Narro V, Perelshteyn J, Polson D, Spiller M. Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America's Cities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [accessed on June 5, 2012]. Available at http://www.unprotectedworkers.org. [Google Scholar]

- Boden LI, Ozonoff A. “Capture-Recapture Estimates of Nonfatal Workplace Injuries and Illnesses”. Annals of Epidemiology. 2008;18(6):500–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MP, Domenzain A, Villoria-Siegert N. Voices from the Margins: Immigrant Workers' Perceptions of Health and Safety in the Workplace. Los Angeles: UCLA Labor Occupational Health Program; 2002. December. [Google Scholar]

- Burgel BJ, Lashuay N, Israel L, Harrison R. “Garment Workers in California: Health Outcomes of the Asian Immigrant Women Workers Clinic”. American Association of Occupational Health Nurses Journal. 2004;52(11):465–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein JM, Levy BS. “The Teaching of Occupational Health in US Medical Schools: Little Improvement in 9 Years”. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(5):846–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Proportion of Workers Who Were Work-Injured and Payment by Workers' Compensation Systems – 10 States”. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(29):897–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day CS, Makhni EC, Mejia E, Lage DE, Rozental TD. “Carpal and Cubital Tunnel Syndrome: Who Gets Surgery?”. Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research. 2010;468(7):1796–803. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1210-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dembe AE. “How Historical Factors have Affected the Application of Workers' Compensation Data to Public Health”. Journal of Public Health Policy. 2010;31(2):227–43. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Ringen K, Men Y, Fujimoto A. “Medical Costs and Sources of Payment for Work-Related Injuries among Hispanic Construction Workers”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2007;49(12):1367–75. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31815796a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, Leigh JP. “Incidence of Workers Compensation Indemnity Claims across Socio-Demographic and Job Characteristics”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2011;54(10):758–70. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston S, Liu T-C. Benchmarks for Designing Workers' Compensation Medical Fee Schedules: 2006. Cambridge, MA: Workers' Compensation Research Institute; 2006. November. [Google Scholar]

- Eccleston S, Laszlo A, Zhao X, Watson M. Benchmarks for Designing Workers' Compensation Medical Fee Schedules: 2001–2002. Cambridge, MA: Workers' Compensation Research Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fan ZJ, Bonauto DK, Foley MP, Silverstein BA. “Underreporting of Work-Related Injury or Illness to Workers' Compensation: Individual and Industry Factors”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;48(9):914–22. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000226253.54138.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert R, Plattus B, Kellogg L, Luo J, Marcus M, Mascolo A, Landrigan PJ. “The Union Health Center: A Working Model of Clinical Care Linked to Preventive Occupational Health Services”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1997;31(3):263–73. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199703)31:3<263::aid-ajim1>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein J, Rest K. “Working on Reform. How Workers' Compensation Medical Care Is Affected by Health Care Reform”. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(1):12–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein J, Buchanan JL, Dembe AE, Stevens B. “Health Services Research in Workers' Compensation Medical Care: Policy Issues and Research Opportunities”. Health Services Research. 1999;34(1 pt 2):427–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawalla DN, Reville RT, Seabury SA. “How Does Health Insurance Affect Workers' Compensation Filing?”. Economic Inquiry. 2007;45(2):286–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lashuay N, Harrison R. Barriers to Occupational Health Services for Low-Wage Workers in California. San Francisco: California Department of Industrial Relations; 2006. A Report to the Commission on Health and Safety and Workers' Compensation. April. [Google Scholar]

- Lax MB. “Workers' Compensation Reform Requires an Agenda… and a Strategy”. New Solutions. 2010;20(3):303–9. doi: 10.2190/NS.20.3.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lax MB, Manetti FA. “Access to Medical Care for Individuals with Workers' Compensation Claims”. New Solutions. 2001;11(4):325–48. doi: 10.2190/YVMM-JQMD-EJRC-2EN7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh JP, Marcin JP. “Workers' Compensation Benefits and Shifting Costs for Occupational Injury and Illness”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(4):445–50. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3182451e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh JP, Robbins JA. “Occupational Disease and Workers' Compensation: Coverage, Costs, and Consequences”. Milbank Memorial Quarterly. 2004;82(4):689–721. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00328.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippel K. “Therapeutic and Anti-Therapeutic Consequences of Workers' Compensation”. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 1999;22(5–6):521–46. doi: 10.1016/s0160-2527(99)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb HJ, Dement JM, Silverstein B, Cameron W, Glazner JE. “Who Is Paying the Bills? Health Care Costs for Musculoskeletal Back Disorders, Washington State Union Carpenters, 1989–2003”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2009;51(10):1185–92. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181b68d0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckhaupt SE, Calvert GM. “Work-Relatedness of Selected Chronic Medical Conditions and Workers' Compensation Utilization: National Health Interview Survey Occupational Health Supplement Data”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53(12):1252–63. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health Occupational Health Surveillance Program [OHSP] Occupational Health and Community Health Center (CHC) Patients: A Report On a Survey Conducted at Five Massachusetts CHCs. Boston: Massachusetts Department of Public Health; 2007. April. [Google Scholar]

- Massachusetts League of Community Health Centers. 2010. Massachusetts Community Health Centers Facts and Issues Brief; January. [accessed on June 5, 2012]. Available at http://www.massleague.org/About/FactsIssuesBrief.pdf.

- McGrail MP, Jr, Calasanz M, Christianson J, Cortez C, Dowd B, Gorman R, Lohman WH, Parker D, Radosevich DM, Westman G. “The Minnesota Health Partnership and Coordinated Health Care and Disability Prevention: The Implementation of an Integrated Benefits and Medical Care Model”. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 2002;12(1):43–54. doi: 10.1023/a:1013598204042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michas MG, Iacono CU. “Overview of Occupational Medicine Training among US Family Medicine Residency Programs”. Family Medicine. 2008;40(2):102–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton DK, Solomon GM, Rosiello RA, Herrick RF. “Risk and Incidence of Asthma Attributable to Occupational Exposure among HMO Members”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1998;33(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199801)33:1<1::aid-ajim1>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Johnson CV, Reisner SL, Vanderwarker R, Mayer KH. “Barriers to Routine HIV Testing among Massachusetts Community Health Center Personnel”. Public Health Reports. 2011;126(5):643–52. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse TF, Dillon C, Warren N, Levenstein C, Warren A. “The Economic and Social Consequences of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders: The Connecticut Upper-Extremity Surveillance Project (CUSP)”. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health. 1998;4(4):209–16. doi: 10.1179/oeh.1998.4.4.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noy C. “Sampling Knowledge: The Hermeneutics of Snowball Sampling in Qualitative Research”. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2008;11(4):327–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ortolon K. “Workers' Comp Worth It?”. Texas Medicine. 2008;104(2):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pransky G, Katz JN, Benjamin K, Himmelstein J. “Improving the Physician Role in Evaluating Work Ability and Managing Disability: A Survey of Primary Care Practitioners”. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2002;24(16):867–74. doi: 10.1080/09638280210142176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premji S, Krause N. “Disparities by Ethnicity, Language, and Immigrant Status in Occupational Health Experiences among Las Vegas Hotel Room Cleaners”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010;53(10):960–75. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman KD, Kalush A, Reilly MJ, Gardiner JC, Reeves M, Luo Z. “How Much Work-Related Injury and Illness Is Missed by the Current National Surveillance System?”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;48(4):357–65. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000205864.81970.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman KD, Gardiner JC, Wang J, Biddle J, Hogan A, Reilly MJ, Roberts K, Welch E. “Why Most Workers with Occupational Repetitive Trauma Do Not File for Workers' Compensation”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2010;42(1):25–34. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takach M. Federal Community Health Centers and State Health Policy: A Primer for Policy Makers. Washington, DC: National Academy for State Health Policy; 2008. June. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, Bureau of Primary Health Care [HRSA] Health Centers: America's Primary Care Safety Net. Reflections on Success, 2002–2007. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. June. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Accountability Office [GAO] Washington, DC: U.S. Government Accountability Office; 2009. Workplace Safety and Health: Enhancing OSHA's Records Audit Process Could Improve the Accuracy of Worker Injury and Illness Data GAO-10-10, October 15. [Google Scholar]

- Utterback DF, Schnorr TM, Silverstein BA, Spieler EA, Leamon TB, Amick BC., 3rd “Occupational Health and Safety Surveillance and Research Using Workers' Compensation Data”. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2012;54(2):171–6. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31823c14cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C. “Another Doctor Leaves Workers' Comp”. Texas Medicine. 2007;103(7):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won JU, Dembe AE. “Services Provided by Family Physicians for Patients with Occupational Injuries and Illnesses”. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(2):138–47. doi: 10.1370/afm.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock E, Neely MH. “Workers' Compensation: A Surprising New Service Line”. MGMA Connexion. 2005;5(1):44–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman S, Williams AF, Stockley KE. “Trends in Medicaid Physician Fees, 2003–2008”. Health Affairs. 2009;28(3):w510–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w510. (Published online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.