Abstract

The evolutionarily conserved kinase PIKfyve that synthesizes PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 has been implicated in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation/glucose entry in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. To decipher PIKfyve's role in muscle and systemic glucose metabolism, here we have developed a novel mouse model with Pikfyve gene disruption in striated muscle (MPIfKO). These mice exhibited systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance at an early age but had unaltered muscle mass or proportion of slow/fast-twitch muscle fibers. Insulin stimulation of in vivo or ex vivo glucose uptake and GLUT4 surface translocation was severely blunted in skeletal muscle. These changes were associated with premature attenuation of Akt phosphorylation in response to in vivo insulin, as tested in young mice. Starting at 10–11 wk of age, MPIfKO mice progressively accumulated greater body weight and fat mass. Despite increased adiposity, serum free fatty acid and triglyceride levels were normal until adulthood. Together with the undetectable lipid accumulation in liver, these data suggest that lipotoxicity and muscle fiber switching do not contribute to muscle insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice. Furthermore, the 80% increase in total fat mass resulted from increased fat cell size rather than altered fat cell number. The observed profound hyperinsulinemia combined with the documented increases in constitutive Akt activation, in vivo glucose uptake, and gene expression of key enzymes for fatty acid biosynthesis in MPIfKO fat tissue suggest that the latter is being sensitized for de novo lipid anabolism. Our data provide the first in vivo evidence that PIKfyve is essential for systemic glucose homeostasis and insulin-regulated glucose uptake/GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle.

Keywords: PIKfyve muscle knockout, PIKfyve metabolic functions, systemic glucose homeostasis, muscle glucose uptake, insulin-regulated glucose transporter 4 translocation, insulin resistance, prediabetes

skeletal muscle plays a central role in postprandial (insulin-regulated) glucose disposal. Therefore, it is not surprising that the skeletal muscle in type 2 diabetes (T2D) and obese patients is the tissue with greatest insulin resistance (2, 3, 42). Skeletal muscle insulin resistance results from impaired insulin-activated glucose uptake due to defective intracellular signaling and trafficking events leading to plasma membrane translocation of the glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4)-containing compartment (3, 19). The role of muscle GLUT4 in maintaining glucose homeostasis is substantiated by genetic studies in mice with muscle-specific GLUT4 knockout. These mice are glucose intolerant and insulin resistant at an early age, with a subset of mice exhibiting frank diabetes (84).

Insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation is an elaborate process whose complex molecular network and mechanisms are still unclear. Current data are consistent with a model whereby in basal conditions GLUT4 is sequestered into a postendosomal pool of storage vesicles [GLUT4 storage vesicles (GSVs)] that, in response to insulin, undergo cytoskeleton-dependent trafficking to and fusion with the plasma membrane (26, 28, 78). An ever-growing list of lipid and protein intermediates downstream of activated insulin receptor tyrosine kinase has been implicated in orchestrating various steps of the GLUT4 cell surface translocation, but the physiological role for many remains unknown (40, 58). A central role in whole body glucose homeostasis has been attributed to class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) (75). Such a role is corroborated by data from genetic mouse models with muscle-specific gene knockout (KO) of class IA PI3K p85α/p85β (PIK3r1/PIK3r2) regulatory subunits, which exhibit whole body glucose intolerance and hyperlipidemia along with muscle insulin resistance (50). Likewise, mice with global and muscle-specific KO of Akt2 (9) and PKCλ (13), respectively, both of which are kinases activated downstream of insulin-induced PI3K-catalyzed PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production, show systemic glucose intolerance along with muscle insulin resistance. Furthermore, muscle-specific KO of the lipid phosphatase PTEN that hydrolyzes the 3′-phosphate in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 enhances insulin sensitivity and protects against diet-induced hyperglycemia (79). However, mouse models with muscle-specific gene KO also have unraveled redundant or compensatory pathways triggered to counterbalance systemic glucose intolerance, which is exemplified by the muscle-specific KO of the insulin receptor (MIRKO) or the p85α regulatory subunit of class IA PI3K (5, 50). Therefore, preclinical studies in animal models with gene disruption selectively in muscle are a prerequisite to establish a physiological role for any insulin-regulated intermediate in signaling to GLUT4.

Downstream of PI3Ks is the phosphoinositide 5′-kinase PIKfyve, the sole enzyme responsible for PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns5P direct biosynthesis (63, 64, 66). Cellular studies have revealed that PIKfyve is recruited to endosomal microdomains in a manner dependent on the presence of activated Rab5 and PtdIns3P, where it regulates key endosome operations such as fission and fusion in the course of endosomal cargo transport (35, 65, 71). One of the most well-studied functions of PIKfyve is its role in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (30, 34). Although the exact mechanism by which these processes are affected is still obscure, PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns5P are both upregulated in response to cell stimulation with insulin (4, 20, 30, 33, 68), promoting distinct steps of the elaborate insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation. PtdIns(3,5)P2 is suggested to function in fusion/fission events in the endosomal system, facilitating the supply of endosomal GLUT4 to the rapidly depleting GSV pool during or after insulin challenge (70). By contrast, the PtdIns5P pool is thought to mechanistically operate at the insulin-regulated step of F-actin remodeling, which is required for optimal GLUT4 cell-surface translocation (59, 64, 68). It is noteworthy that PIKfyve exhibits pleiotropic functions and, in addition to mediating insulin-induced signals for endosome/actin remodeling in the course of GLUT4 translocation/glucose uptake activation, has been implicated in myriad essential cellular processes such as maintenance of endomembrane homeostasis, endosome processing in the course of constitutive outward trafficking, lysosomal trafficking, nuclear transport, gene transcription, and cell cycle progression (71). Given this multifunctionality, recent observations for early embryonic lethality of the systemic pikfyve gene KO in mice, likely due to arrested DNA synthesis, did not come as a surprise (29). The surprising finding was the normality of the heterozygous PIKfyvewild-type (WT)/KO mice that lived to late adulthood without ostensible morphological defects despite one-half of the normal amounts of the PIKfyve protein, PtdIns(3,5)P2, and PtdIns5P (29).

To begin elucidating the metabolic roles of PIKfyve in vivo and to circumvent the lethality associated with pikfyve−/− germline KO, we engineered mice in which the pikfyve gene could be deleted in a tissue-specific manner by the Cre-loxP approach (29). Because insulin sensitivity upon muscle-specific KO undoubtedly represents the ultimate indicator as to whether or not PIKfyve is part of the mechanisms regulating whole body glucose homeostasis, in this study we generated mice (designated as MPIfKO) with pikfyve deletion in muscle, using the muscle creatine kinase (MCK) promoter to drive Cre expression. We observed that the MPIfKO mice exhibited marked systemic glucose intolerance and muscle insulin resistance at an early age, followed by increased body weight and adiposity. Our study demonstrates for the first time the essential role of PIKfyve in muscle and whole body glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal procedures were approved by the Wayne State University Animal Care and Use Committee and conducted according to institutional ethics guidelines for animal work by the Association and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Generation of MPIfKO mice.

In previous studies, we generated a conditional pikfyve mutant allele (fl) on a C57BL/6J (BL6) background by the Cre-loxP approach (29), allowing for tissue-specific pikfyve ablation. To generate mice with selective disruption of pikfyve in striated muscle, we first removed the neomycin resistance selection cassette by crossing the PIKfyvefl/WT mice with BL6 mice expressing FlpE recombinase. The flp gene was then bred out by crossing PIKfyvefl/fl-Δneo mice with BL6 mice. To generate MPIfKO mice, the PIKfyvefl/fl progeny was crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase under the muscle-specific creatine kinase promoter MCK propagated in a BL6 background (Taconic, Hudson, NY). Genotyping was performed by PCR using genomic DNA isolated from tails of 20-day-old mice and specific primer pairs, as specified previously (29). PIKfyvefl/fl mice were used as controls, PIKfyvefl/fl;MCK-Cre/+ mice were used as a homozygous mutant, and PIKfyvefl/WT;MCK-Cre/+ were used as a heterozygous mutant. The PIKfyve floxed allele had no effect on PIKfyve expression or phenotypes (29). Likewise, no obvious phenotypic differences were noted between control (PIKfyvefl/fl) and heterozygous PIKfyvefl/WT;MCK-Cre/+ mice; therefore, most of the experiments were performed by comparing PIKfyvefl/fl control with PIKfyvefl/fl;MCK-Cre/+ (MPIfKO) mice. Animals were maintained in a temperature-controlled environment (22 ± 1) with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (6 AM to 6 PM) and a standard rodent diet (4.5% calories from fat; LabDiets no. 5001), with free access to food and water. Unless otherwise stated, experiments were performed on male animals.

Body composition and adiposity.

Fat or lean mass and water content were measured in randomly fed nonanesthetized mice, typically between noon and 2 PM, using EcoMRI-130 (Echo Medical Systems). Regional fat distribution was assessed by dissecting and weighing individual fat pads (epididymal, perirenal, inguinal, and interscapular brown fat). Adiposity index was calculated by the following formula as described elsewhere (21, 46): total fat pad weight/(body weight − total fat pad weight).

Food/water intake and energy expenditure.

Food and water intake were measured in individually housed 9-wk-old mice for a period of 7 days, subsequent to a 3-day acclimation period. On the same mice, O2 consumption and CO2 production were assessed using an indirect calorimeter (LE400 Panlab; Harvard Apparatus). Individually housed mice were acclimated to the metabolic cages for 48 h, followed by 72-h data collection of cage O2 and CO2 concentrations recorded every 30 min for 5 min, with constant cage air flow of 200 ml/min. Data were quantified for the light and dark cycle.

Blood/serum metabolites and hormones.

Glucose was determined by a glucometer (Truetrack) in a blood droplet formed after mouse tail clipping. Cholesterol and nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA) were measured in serum, using enzymatic kits (catalog nos. 1000760–1EA and 99475409, respectively) from Wako (Richmond, VA). Serum triglycerides (TG) were measured by the TR0100 kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Plasma insulin levels were determined in 10-wk- and 6-mo-old mice with an ELISA kit and a radioimmunoassay, respectively, from Linco Research (EMD Millipore, St. Charles, MO).

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests.

For glucose (GTT) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT), individually housed (on paper bedding) and morning-fasted mice (5 h) were injected intraperitoneally (ip) with 1.5 g of dextrose/kg body wt or insulin (0.75 U/kg body wt) (Humalog; Eli Lilly). Tail blood prior to and following glucose or insulin injections was used for glucose measurements at the indicated time intervals.

Glucose uptake in isolated skeletal muscle.

Ex vivo glucose uptake was measured by 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) uptake in isolated muscles, as described elsewhere (23, 43), with slight modifications. Briefly, dissected muscles were placed in prewarmed glass vials containing 2.0 ml of Krebs-Ringer-HEPES (KRH) buffer [composition described elsewhere (30)] containing 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 8 mM mannitol, 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and insulin (Humalog) at indicated concentrations (0, 0.36, and 12 nM) and preincubated in a temperature-controlled water bath at 35°C for 60 min with rotation (60 rpm). Muscles were then transferred to fresh glass vials containing KRH-BSA supplemented with 1 mM [3H]2DG (specific activity 3 mCi/mmol) and 9 mM [14C]mannitol (specific activity 0.022 mCi/mmol) without or with insulin and incubated for 15 min with rotation. Muscles were blotted on filter paper, trimmed of tendons, weighed, and digested in 0.5 ml of 1 N NaOH for 30 min at 55°C. Following neutralization with 0.5 ml of 1 N HCl, the 3H and 14C radioactivity was determined in duplicate samples after the addition of scintillation fluid. Intracellular accumulation of 2DG (in μmol·15 min−1·g muscle−1) was calculated by subtracting the extracellular from the total muscle [3H]2DG. Extracellular [3H]2DG was estimated from the measurement of the extracellular fluid volume by [14C]mannitol.

In vivo glucose uptake in skeletal muscle.

Glucose transport was measured in vivo as described (13, 47). Briefly, following 14-h food deprivation, mice were injected ip with saline containing 50 μCi/kg [3H]2DG (NET328, specific activity 8.5 Ci/mmol) with or without insulin (1 U/kg body wt). Injections also contained 5 μCi/kg l-[14C]glucose (NEC478, specific activity 51 mCi/mmol) for the control of glucose diffusion into the extracellular space. Fifteen minutes postinjection, mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and blood for glucose determinations was collected from the heart. Individual muscles, including vastus lateralis, gastrocnemius, or soleus, and epididymal fat tissue were excised and snap-frozen in N2. Prior to the radioactive counting, plasma and muscle tissue were hydrolyzed in 1 N NaOH for 30 min at 55°C and neutralized with 1 N HCl. The glucose-specific activity was calculated by dividing plasma radioactivity by plasma glucose levels. In vivo glucose uptake was calculated by subtracting the nonspecific uptake and normalizing for tissue weight and glucose-specific activity (13, 47).

In vivo insulin stimulation and subcellular fractionation of muscle GLUT4.

Insulin stimulation in vivo was carried out in 12-wk-old male mice. Following 14 h of starvation, mice were injected ip with either saline or 5 U/kg body wt of insulin. Five or 15 minutes postinjection, liver, muscle, and adipose tissues were removed and frozen in liquid N2 for immunoblot analyses of the insulin-signaling proteins. Alternatively, dissected quadriceps and gastrocnemius trimmed of connective tissues were immediately subjected to differential centrifugation without freezing to obtain plasma membrane- and intracellular membrane-enriched fractions by a technique developed previously for rat and mouse muscle (80, 83) and adopted herein with slight modification. Briefly, muscles were homogenized (Polytron PT-3000; 13,500 rpm, 3 bursts, 10 s each) in 3 ml of ice-cold 20 mM HEPES buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 1× protease inhibitor mix (29). Samples underwent two consecutive centrifugations at 2,000 g for 5 min (to eliminate debris) and 9,000 g for 20 min to obtain the “P1” pellet enriched in plasma membrane proteins. The supernatant prior to the second centrifugation contained total protein. The P1 supernatant was centrifuged at 180,000 g (TLA100.3; Beckman) for 90 min. The pellet from this spin, enriched with intracellular membrane proteins, was resuspended, loaded onto a 4.5-ml 10–30% continuous sucrose gradient, and centrifuged at 216,000 g for 55 min (SW50.1 rotor; Beckman). Gradient fractions were collected (500-μl aliquots). P1 pellets (plasma membranes) and fractions from the sucrose gradient (intracellular membranes) were subjected to immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. Band intensity was quantified by densitometry as described (29).

Antibodies and Western blotting analyses.

Rabbit polyclonal anti-PIKfyve (R7069; East-Acres) (66), anti-ArPIKfyve (WS047; Covance, Denver, PA) (65, 67), anti-Sac3 (65, 67), and anti-GDI1 antibodies (to normalize for protein loading) (R5057; East-Acres) (72) were characterized previously. Anti-phosphotyrosine (4G10), anti-phospho-Thr308-Akt, anti-phosphoSer473-Akt, or anti-Akt antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Polyclonal antibodies against GLUT4 (R1288), GLUT1 (R480) and insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP) were gifts from Drs. Mike Czech and Paul Pilch. Western blotting analyses were conducted as described previously (29).

Tissue histology.

Epididymal fat pads were dissected from male mice and fixed in 4% formaldehyde overnight at room temperature. Cross sections (5 μm) of paraffin-embedded pads stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E) as described (6) were viewed with a Nikon Eclipse TE200 microscope. Images were captured and cell size was measured with a SPOT RT slider charge-coupled device camera. The diameter of >20 cells from different microscopic fields was determined and averaged for each mouse. Gastrocnemius was dissected, snap-frozen in a bath of 2-methylbutane and dry ice, and stored at −80°C until sectioning. Cryostat (−20°C) cross sections (10 μm) were obtained starting 3 mm from the beginning of the Achilles tendon, mounted on charged slides, fixed in 4% formaldehyde at room temperature, and stained with H & E. Muscle fiber size was compared as described above for fat cell size. Intracellular lipid droplets in liver and muscle frozen sections (10 μm) were evaluated by the Oil Red O staining protocol (6). Liver from high-fat diet-treated mice served as a positive control.

Determination of the muscle fiber type.

Muscle fiber type was examined in extensor digitorum longus (EDL), soleus, and diaphragm muscles by immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies against muscle fiber type-specific myofilament protein isoforms or troponin (Tn), as described previously (15). Briefly, freshly isolated muscle tissues were homogenized using a high-speed mechanical homogenizer in SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer containing 2% SDS to extract total proteins. Protein samples were denatured by heating at 80°C for 5 min and clarified by centrifugation. The protein extracts were examined on 14% Laemmli gels with an acrylamide/bis-acrylamide ratio of 180:1. Duplicate gels were subjected to Coomassie blue staining or to Western blotting using an anti-TnI mAb TnI-1, recognizing all TnI isoforms, and anti-TnT mAb CT3, recognizing slow skeletal muscle TnT and cardiac muscle TnT. Antibodies were diluted in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 0.1% BSA and incubated with the nitrocellulose membranes at 4°C overnight. After high-stringency washes with TBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.05% SDS, membranes were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in TBS-BSA and washed. Blots were developed in 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate nitro blue tetrazolium substrate solution to visualize the protein bands.

Gene expression.

RNA was isolated by the TRIzol reagent protocol (Invitrogen) and tested for concentration and purity, as described previously (32). cDNA was synthesized by using primers for acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1 (Acc1), lipoprotein lipase (Lpl), and fatty acid synthase (Fas), as specified elsewhere (18, 25). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed as we described previously (32).

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Data from control and MPIfKO mice were compared by Student's t-test. Statistical significance is considered when P < 0.05. Excel (Microsoft) and the trapezoid rule (76) were used to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) from time zero to the last time point (120 min in GTT and 60 min in ITT) postinjection. Statistical significance of ITT and GTT curves was determined by comparing differences in AUC between the groups by Student's t-test.

RESULTS

Characterization of MPIfKO mice.

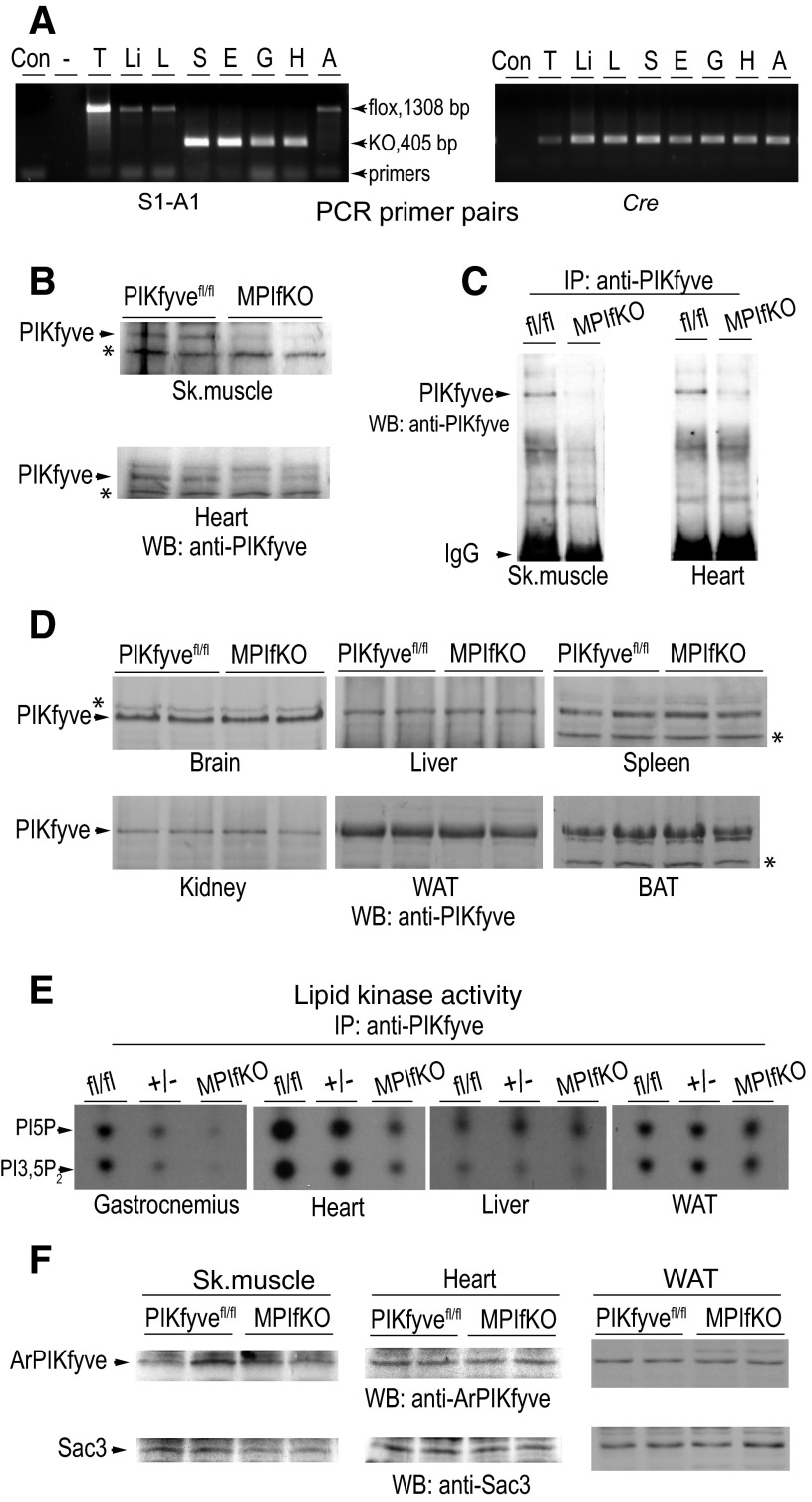

Mice with loxP sites flanking exon 6 of the mouse pikfyve gene (29) were mated with mice carrying Cre recombinase under the MCK promoter. PCR analyses with several sets of primers demonstrated that deletion of exon 6 in the pikfyve gene took place selectively in striated muscle, with no DNA recombination events occurring in other tissues and organs such as liver, fat, lung, and spleen (Fig. 1A). Deletion of exon 6 in the pikfyve floxed allele causes a frame shift and a translation stop at residue 171, i.e., prior to the first evolutionarily conserved domain. Similarly to our previous observation with mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from heterozygous PIKfyve mice, MPIfKO muscle lysates had undetectable expression of the partial NH2-terminal peptide from the PIKfyve sequence by immunoblotting (Ref. 29 and data not shown), making a putative dominant-negative effect in the mutant mice unlikely.

Fig. 1.

Validation of muscle-specific ablation of PIKfyve by PCR, Western blotting (WB), immunoprecipitation (IP), and in vitro kinase activity. A: representative genotyping with specific primer pairs for S1-A1 encompassing exon 6 and Cre, as indicated. A product of 405 bp is detected only in soleus (S), EDL (E), gastrocnemius (G), and heart (H) of the Cre-positive MPIfKO mice, whereas the other tissues, i.e., thymus (T), liver (Li), lung (L), and fat (A), make a product of 1,308 bp, having intact exon 6. B–D: RIPA+ lysates, derived from indicated tissues dissected from MPIfKO mice and PIKfyvefl/fl littermates, were clarified by centrifugation. Equal amounts of tissue protein (250 and 160 μg in muscle and other tissues, respectively) from each genotype were examined by WB with anti-PIKfyve antibodies (B and D) or by IP [2.5 mg, skeletal muscle (sk. muscle); and 875 μg, heart] with anti-PIKfyve prior to WB (C). Blots were reprobed with anti-GDI1 to normalize for loading (not shown). *Equal loading is also apparent by the identical intensity of the unspecific bands in the tissue samples. Shown are chemiluminescence detections from representative experiments with 2 mice/genotype for each condition out of 3–5 independent determinations. E: clarified fresh RIPA+ lysates derived from the indicated tissues dissected from MPIfKO and PIKfyvefl/fl mice underwent IP with anti-PIKfyve antibodies. Washed IPs were subjected to in vitro lipid kinase activity assay. Shown are representative autoradiograms of a TLC plate with resolved radiolabeled lipids, indicating that only in muscle of MPIfKO mice were the PIKfyve lipid products abrogated. In heterozygotes (+/−, genotype fl/WT; Cre+), these products were detected in gastrocnemius at significantly lower levels than in control (fl/fl;Cre−). F: clarified fresh RIPA+ lysates (250 μg protein) derived from the indicated tissues dissected from control and mutant mice were subjected to WB with antibodies against the partner proteins ArPIKfyve and Sac3. No significant changes between control and MPIfKO mice are apparent. Shown are chemiluminescence detections from representative experiments, with 2 mice/genotype for each condition out of 3–5 independent determinations. WAT, white adipose tissue; BAT, brown adipose tissue.

Western blot analyses with or without prior immunoprecipitation with anti-PIKfyve antibodies revealed that levels of the PIKfyve protein were reduced profoundly in skeletal muscle and heart (Fig. 1, B and C). The faint PIKfyve bands seen in the muscle samples of MPIfKO mice are most likely related to the presence of other cell types, such as endothelial cells and fibroblasts, in which PIKfyve expression is intact. Notably, in the other tissues tested, including brain, lung, spleen, liver, kidney, and white and brown adipose tissue, the PIKfyve protein levels remained unaltered (Fig. 1D).

PIKfyve levels in striated muscle are relatively low compared with fat tissue and brain, as evidenced by the low intensity of the PIKfyve-immunoreactive band despite the considerable protein amount loaded on the gel (Fig. 1B). In addition, in SDS-PAGE gels, PIKfyve (∼220 kDa) migrates close to the muscle-abundant myosin heavy chain (∼200 kDa). Therefore, to overcome the disadvantaged PIKfyve detection in muscle by immunoblotting, as well as to gain insights about the status of the PIKfyve activity upon muscle-specific knockout, we next examined the in vitro PIKfyve kinase activity that typically parallels the PIKfyve protein levels. Data obtained with immunopurified PIKfyve derived from various tissues revealed that the PIKfyve lipid kinase activity was reduced only in muscle of MPIfKO mice, as evidenced by the marked and selective diminution in in vitro-generated PtdIns(3,5)P2 and PtdIns5P products (Fig. 1E). In the heterozygotes, the lipid products were also reduced only in muscle, reaching ∼50% of the control levels in flox/flox mice as expected for haploinsufficiency (Fig. 1E).

We have demonstrated previously that PIKfyve forms a stable triple complex with its activator ArPIKfyve and the phosphatase Sac3, called the PAS complex, that supports both synthesis and turnover of PtdIns(3,5)P2 (31, 65). To determine whether loss of muscle PIKfyve alters expression of these two partner proteins, we measured Sac3 and ArPIKfyve protein levels in muscle lysates by immunoblotting with anti-ArPIKfyve or anti-Sac3 antibodies. Results from at least six independent immunoblots revealed that muscle PIKfyve protein ablation was not paralleled by diminution of ArPIKfyve and Sac3 protein levels in skeletal muscle, heart, or other tissues (Fig. 1F and data not shown). These data corroborate previous observations in tissues or MEFs derived from heterozygous PIKfyveWT/KO mice, in which the 50% decrease in PIKfyve protein levels occurred without changes in the other two proteins of the PAS complex (29), and indicate that the metabolic changes in MPIfKO mice are triggered solely by PIKfyve ablation.

Increased body weight and fat mass in MPIfKO mice.

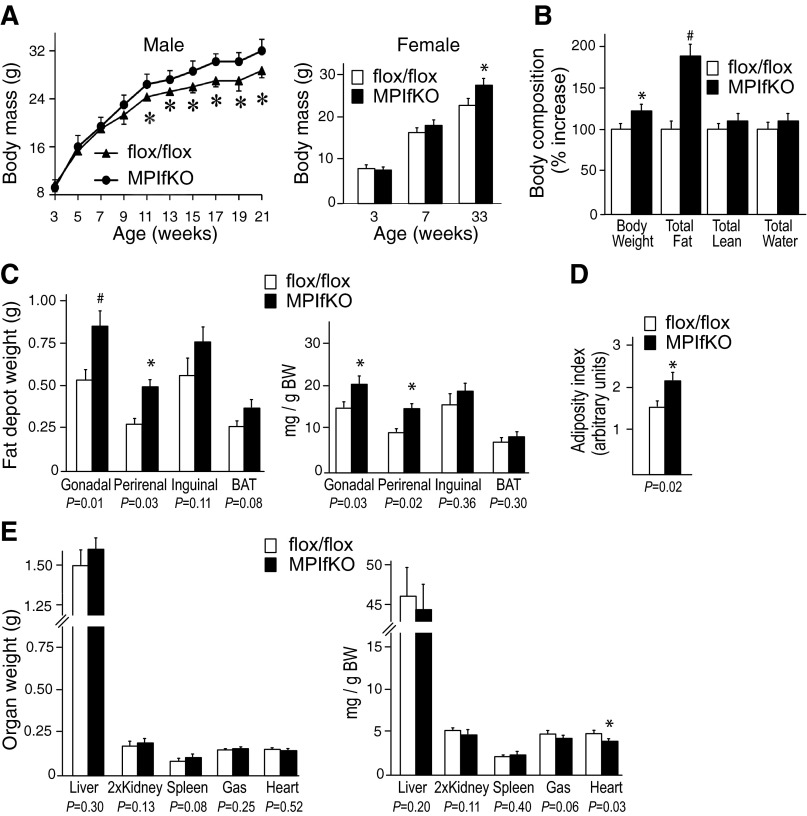

MPIfKO mice were born at the expected Mendelian ratio. They were apparently healthy and fertile, with a lifespan similar to that of their littermates with a genotype PIKfyvefl/fl;Mck-Cre− or heterozygous PIKfyvefl/WT;Mck-Cre/+, ≤12 mo of age, when the study ended. Statistically significant metabolic differences between the control PIKfyvefl/fl and heterozygous PIKfyvefl/WT;MCK-Cre/+ mice up to this age were also not noted; therefore, most of the experiments were performed comparing PIKfyvefl/fl and MPIfKO mice. Intriguingly, whereas at birth the body weight of MPIfKO mice was similar to that of their littermates, at ∼10–11 wk of age the mutant mice of both sexes began to gain more weight that continually increased as the mice aged (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Increased body weight gain and adiposity in MPIfKO mice. A: rate of body weight gain in male (n = 7/group) and female mice (n = 4/group) fed a regular diet. B: in vivo body composition by EcoMRI (6-mo-old male mice; n = 7/group). C–E: absolute or relative organ weights normalized per body weight and the adiposity index in 9- to 10-mo-old male mice (n = 8–10/group); #P < 0.01 and *P < 0.05 vs. control. Adiposity index was calculated by the following formula: total fat pad weight/(body weight − total fat pad weight).

The body weight gain was associated with marked increases in total fat mass, whereas the lean mass remained unaltered, as tested by noninvasive EchoMRI in 6-mo-old male mice (Fig. 2B). Organ dissection further confirmed that the absolute weights of several white fat depots, including gonadal, perirenal, and inguinal, were greater in MPIfKO mice, with gonadal and perirenal fat showing statistically significant differences even when normalized per gram body weight (Fig. 2C). Interscapular brown fat pads in MPIfKO mice showed a trend for higher weight vs. littermate controls, but the difference remained statistically insignificant (Fig. 2C). Concordantly, the adiposity index (21, 46) was significantly higher in the mutant animals (by 38%) compared with controls (Fig. 2D). By contrast, the absolute weight changes of liver, kidney, spleen, and skeletal muscle were statistically insignificant, as were the relative changes in these tissues' weights when normalized per body weight (Fig. 2E). Notably, whereas absolute heart weight was similar between the two groups, heart weight per gram body weight was lower in MPIfKO mice compared with PIKfyvefl/fl control mice at 9–10 mo of age (Fig. 2E). Together, these data indicate that the higher body weights in MPIfKO mice were attributable to increased adiposity.

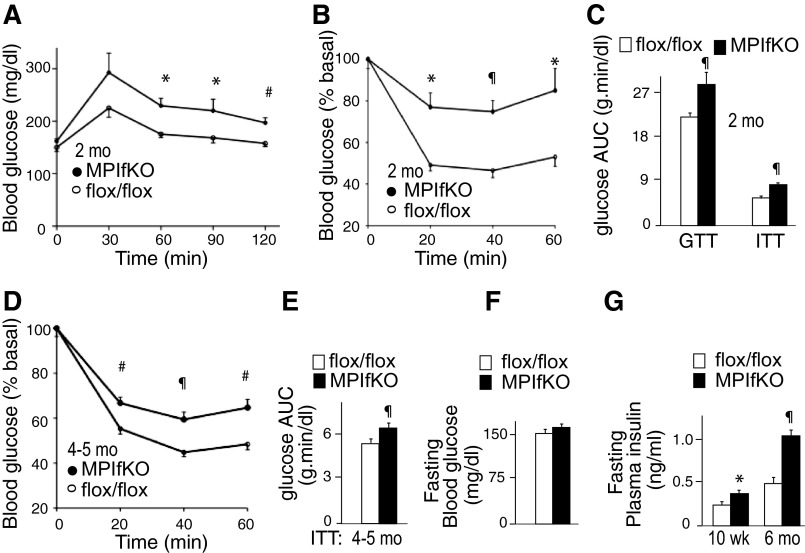

Potential mechanisms for increased body weight/fat mass in MPIfKO mice could involve increased food intake and/or reduced energy expenditure. Nine-week-old MPIfKO mice that exhibited the body weight of control mice showed a trend for slightly higher food (by 5%) and water ingestion (by 3.9%) vs. age-matched control mice, as measured over a 1-wk period (Fig. 3A). Although these changes were not statistically significant, if such a trend was to persist over a longer period, it could have provided the extra calories to account for the slight increases in body weight gain in MPIfKO mice (see Fig. 2A). Furthermore, assessments of energy expenditure in these mice at the age of 10 wk revealed that both O2 consumption and CO2 production in either the light or dark cycle were similar between the two groups (Fig. 3B). Together these data suggest that increased energy intake, rather than reduced energy expenditure, may have accounted for increased body weight gain in mature MPIfKO mice.

Fig. 3.

Food/water intake and energy expenditure in MPIfKO mice. A: food/water consumption was measured in 9-wk-old male mice fed a regular diet over a period of 7 days. Note that the body weight at this age was similar between the mutant and control groups (n = 7/group). B: O2 consumption and CO2 production were measured in 10-wk-old male mice over a period of 72 h, subsequent to 48-h acclimation, and quantified separately for the light and dark cycles. The 2 groups show no differences (n = 7/group).

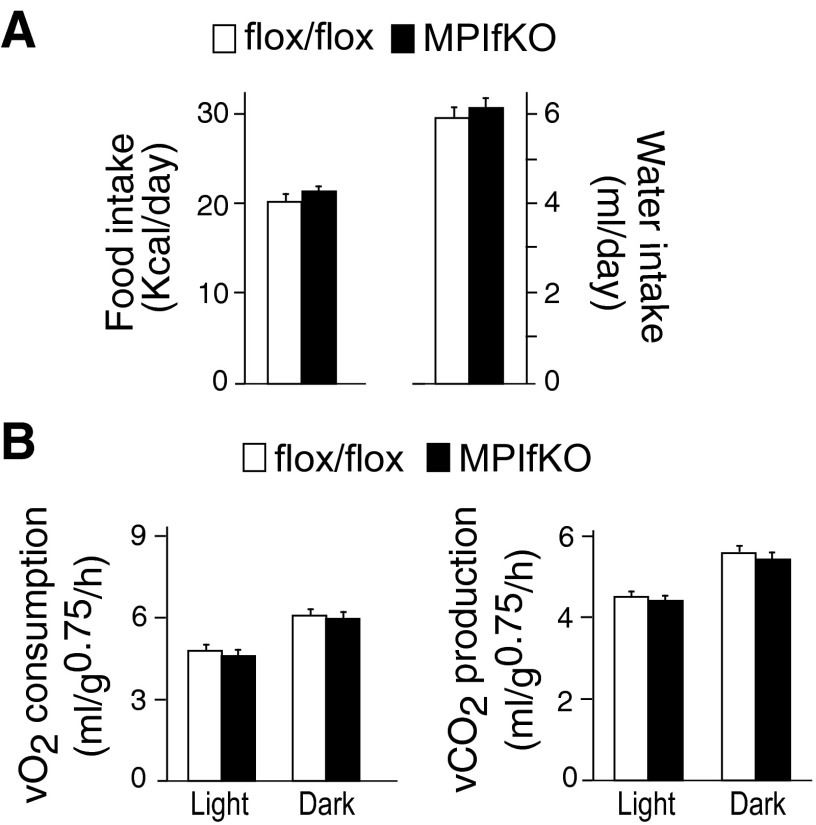

MPIfKO mice are glucose intolerant, insulin resistant, and hyperinsulinemic.

To determine the systemic metabolic consequences of muscle PIKfyve ablation, we performed GTT and ITT in 8- to 10-wk-old male MPIfKO and PIKfyvefl/fl age-matched controls. It should be emphasized that at this early age there are no differences in body weight and adiposity, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. Despite this, GTT revealed that whereas the blood glucose levels at 0 min were similar between the two groups, they increased prominently in MPIfKO mice after glucose injection, with differences becoming statistically significant at and after the 60th min (Fig. 4A). Concordantly, the glucose AUC during GTT was significantly greater in MPIfKO mice compared with age-matched controls (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice. A and B: glucose levels were measured at indicated time points before and after 1.5 g/kg of glucose (A) or 0.75 U/kg of insulin (B), which were administered ip in 8- to 10-wk-old male mice; n = 6–8/group. C: the area under the blood glucose curves (AUC) during glucose (GTT) and insulin tolerance tests (ITT). D and E: glucose levels measured at indicated time points before and after ip administration of insulin (0.75 U/kg) in 4- to 5-mo-old male mice (n = 9–13/group; D) and AUC during ITT (E), indicating that insulin resistance persisted in older MPIfKO mice. F: fasting blood glucose concentration in 6-mo-old male mice; n = 9–13/group. G: fasting plasma insulin in 10-wk- (n = 6/group) and 6-mo-old mice (n = 7/group). *P < 0.05, #P < 0.01, and ¶P < 0.001 vs. controls.

Insulin sensitivity in 8- to 10-wk-old MPIfKO mice was also profoundly impaired, as judged by the blunted hypoglycemic response to the ip injection of insulin during ITT. Thus, as illustrated in Fig. 4B, blood glucose levels in MPIfKO mice remained higher compared with those in age-matched control mice, with a statistically significant difference at each time point following insulin injection. In contrast, basal glucose levels between the two groups were not statistically different (not shown). The profoundly reduced insulin sensitivity is further underscored by the AUC during ITT, which was ∼41% higher (P < 0.001) in MPIfKO compared with control mice (Fig. 4C). Concordantly, the insulin-resistant (IR) index, calculated as the product of the GTT's and ITT's AUC (46), was markedly greater (1.9-fold) in MPIfKO mice compared with age-matched control animals (2.34 ± 0.63 vs. 1.25 ± 0.11, P < 0.002). These data demonstrate profound systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice at an early age.

Impaired GTT and ITT persisted as MPIfKO mice aged (Fig. 4D and data not shown). However, despite aging and increased adiposity, as in the younger mice, fasting glucose levels in 6-mo-old MPIfKO mice were normal, as evidenced by the lack of significant changes vs. age-matched control mice, consistent with a lack of overt diabetes (Fig. 4F). Considering a potential compensatory mechanism associated with increased insulin secretion by the pancreatic β-cells to mitigate dysregulated glucose homeostasis, we measured fasting plasma insulin levels in 10-wk- and 6-mo-old mice. Whereas younger mice showed only a 50% increase, the 6-mo-old MPIfKO mice exhibited profound increases (2.3-fold) in plasma insulin vs. control littermates (Fig. 4G). Together these data indicate that aged MPIfKO mice maintained systemic glucose intolerance and insulin insensitivity for glucose disposals but also developed marked hyperinsulinemia in an attempt to compensate the defects.

Reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and cell surface GLUT4 accumulation in MPIfKO muscle.

The observed systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice in a background of hyperinsulinemia suggest that glucose disposal by peripheral tissues, and particularly skeletal muscle, might be impaired. This prediction is also implied by data in cultured 3T3-L1 adipocytes, where we observed inhibited glucose uptake in response to insulin under perturbed PIKfyve functionality (30, 34, 36). However, intact muscle and muscle cells have never been tested in such a setting. Therefore, we examined the uptake of 2DG into isolated skeletal muscle at basal and insulin-stimulated conditions using two insulin doses: physiological (0.36 nM) and supraphysiological (12 nM). We analyzed two representative muscles that differ in their metabolic properties, the oxidative soleus and glycolytic EDL. As illustrated in Fig. 5A, basal 2DG uptake was similar between control and mutant muscles of both types. However, whereas insulin-regulated 2DG uptake in control muscles was increased at physiological and maximally activating insulin concentrations, it was severely blunted (by >85%) in both EDL and soleus of MPIfKO mice (Fig. 5A). These ex vivo data were supported by the in vivo assessment of glucose uptake. In all MPIfKO muscles examined, such as gastrocnemius, soleus, and vastus lateralis, the insulin-simulated but not the basal glucose uptake was significantly impaired (Fig. 5B and data not shown). Strikingly consistent with previous studies (47), we observed markedly greater in vivo basal glucose uptake in soleus vs. other muscles (∼20-fold), but this remained similar in the mutant and control muscles. Collectively, these results indicate that deletion of muscle pikfyve leads to marked decreases in insulin's ability to stimulate glucose entry into skeletal muscle both ex vivo and in vivo and suggest that muscle PIKfyve plays an essential role in insulin-regulated muscle glucose uptake.

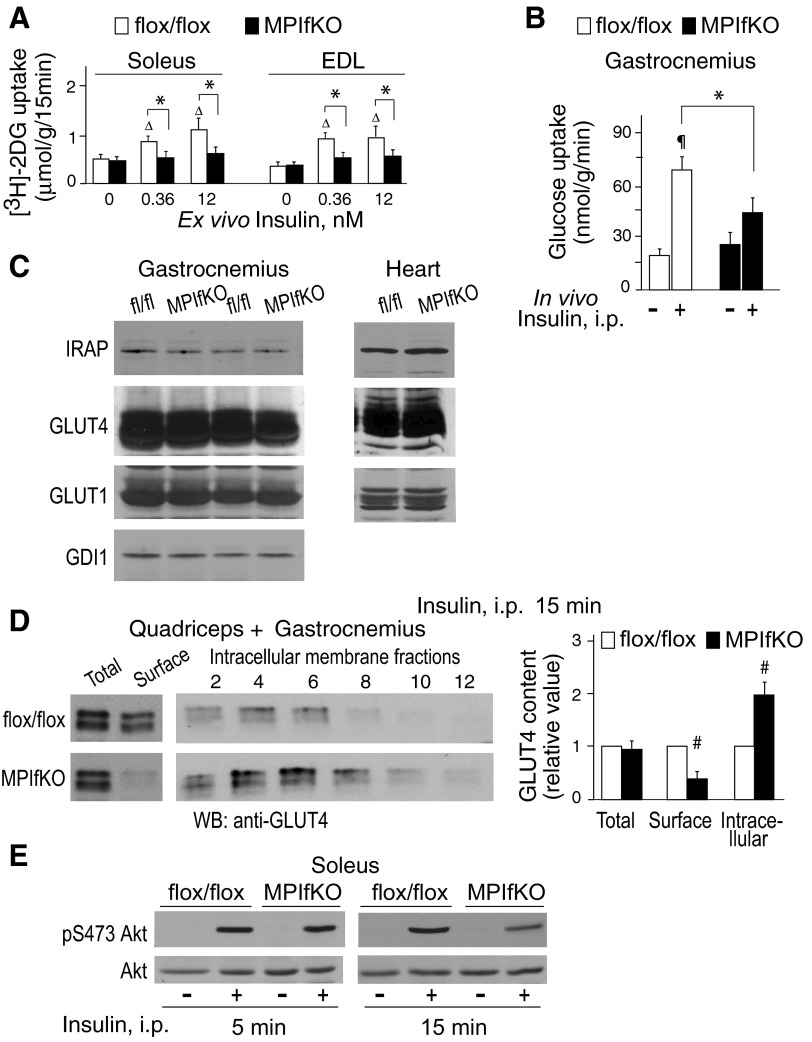

Fig. 5.

Impaired insulin-dependent glucose uptake and glucose transporter (GLUT)4 translocation in muscle of MPIfKO. A: ex vivo glucose uptake was determined in soleus or extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles, excised from 10-wk-old mice, and incubated with insulin at the indicated concentrations for 15 min. 2-[3H]deoxyglucose ([3H]2DG) uptake was determined as described in materials and methods; n = 4–7/condition; ΔP < 0.05 vs. 0 insulin; *P < 0.05 vs. control mice. B: in vivo glucose uptake was measured in 14-h-starved 12-wk-old male mice that were administered [3H]2DG and l-[14C]glucose ip with or without insulin (1 U/kg), as described in materials and methods; n = 5/condition. ¶P < 0.001 vs. nontreated control group; *P < 0.05 between the insulin-treated groups. C: clarified fresh RIPA+ lysates isolated from gastrocnemius or cardiac muscle were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Blots were reprobed with anti-GDI1 to normalize for loading. Shown are chemiluminescence detections from a representative experiment, with 2 mice/genotype out of 3–6 independent determinations. Apparent are the similar levels of GLUT4, insulin-responsive aminopeptidase (IRAP), and GLUT1 between MPIfKO and control mice. D: insulin (5 U/kg) was administered ip in 14-h-fasted mice. Fifteen minutes following injection, quadriceps (2×) and gastrocnemius (1×) were dissected and subjected to differential/sucrose velocity centrifugation, as detailed in materials and methods. Shown are chemiluminescence detections of an anti-GLUT4 blot from a representative experiment and quantitation by densitometry from 3 experiments (#P < 0.01). E: insulin (5 U/kg) was administered ip in 14-h-starved mice for 5 or 15 min. Soleus muscle was isolated and subjected to Western blotting analysis (65 μg of protein) with antibodies for phospho-Ser473 Akt or total Akt. Reduced Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO muscle is evident at 15-min but not 5-min insulin. Shown are chemiluminescence detections from a representative experiment for each time point out of 3 independent determinations.

To mechanistically address how PIKfyve ablation led to profound inhibition of muscle glucose uptake, we first examined whether the total amount of GLUT4 protein was reduced. Intriguingly, Western blotting with anti-GLUT4 antibodies indicated that the GLUT4 content in gastrocnemius derived from MPIfKO mice was comparable with that in control littermates (Fig. 5C). Likewise, levels of IRAP, a component of GLUT4 vesicles required in GSV formation (40, 41), remained unaltered, suggesting that GSVs in MPIfKO skeletal muscles were properly formed. Consistent with the observed unaltered basal glucose entry that is mediated by GLUT1, we failed to detect differences in muscle GLUT1 levels between the MPIfKO and control mice (Fig. 5C). Levels of GLUT4, IRAP, and GLUT1 were also unaltered in soleus, quadriceps, and cardiac muscles of MPIfKO vs. control mice (Fig. 5C and data not shown), suggestive of other defects underlying muscle insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice.

The primary mechanism by which insulin stimulates glucose uptake in skeletal muscle is the translocation of an intracellular pool of GLUT4 vesicles to the cell surface (40, 82). Indeed, in both humans and mouse models with insulin resistance or diabetes, the insulin-triggered GLUT4 translocation mechanism has often been found to be defective (3, 42, 61). Therefore, to determine the relative distribution of GLUT4 between muscle intracellular and plasma membranes, muscles (quadriceps plus gastrocnemius) isolated from insulin-injected mutant and control mice were subjected to subcellular fractionation, applying protocols designed specifically for mouse/rat muscle differential fractionation (80, 83). Fractions enriched in plasma or intracellular membranes were then subjected to Western blotting. As illustrated in Fig. 5D, whereas in control mice insulin administration (15 min) resulted in increased amounts of GLUT4 in the cell surface membrane-enriched fraction, such changes in MPIfKO mice were not apparent. These data are further corroborated by the opposite changes of immunoreactive GLUT4 in the intracellular membrane fractions in response to insulin. Thus, as shown in Fig. 5D, significantly higher amounts of GLUT4 were retained in the intracellular membrane fractions of MPIfKO vs. control muscles. Collectively, these data indicate a defective insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation mechanism in MPIfKO mice that likely underlies the impaired muscle glucose uptake caused by the absence of muscle PIKfyve.

Attenuated insulin-dependent Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO muscle.

Lack of PIKfyve and PtdIns(3,5)P2 may directly affect proper fusion/fission events in the endosomal system to arrest GLUT4 sorting and insulin-regulated translocation in MPIfKO muscle, as suggested by data in 3T3-L1 adipocytes (71). An additional mechanism may involve impaired PIKfyve-catalyzed synthesis of PtdIns5P that is lost in parallel with PIKfyve ablation (29, 64, 85). Intriguingly, PtdIns5P has recently emerged as a potent regulator of Akt phosphorylation, a critical event in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation (39, 55, 56). Concordantly, studies in 3T3L1 adipocytes have revealed that modulations in PIKfyve protein or enzymatic activity parallel changes in insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation (30, 34). Therefore, to test whether muscle PIKfyve/PtdIns5P ablation affects muscle Akt phosphorylation in vivo, we performed immunoblotting with phospho-Akt antibodies of soleus muscle lysates derived from insulin-injected or noninjected mice. Intriguingly, both Akt Ser473 and Akt Thr308 phosphorylation sites were similarly phosphorylated in mutant and control muscle 5 min postinjection (Fig. 5E). By contrast, both sites were only weakly phosphorylated in MPIfKO muscle vs. control littermate mice at a later time after insulin treatment (15 min; Fig. 5E and data not shown). These data indicate robust attenuation of muscle Akt phosphorylation in the absence of muscle PIKfyve, consistent with the requirement of PIKfyve in the maintenance of sustained Akt phosphorylation by insulin over time.

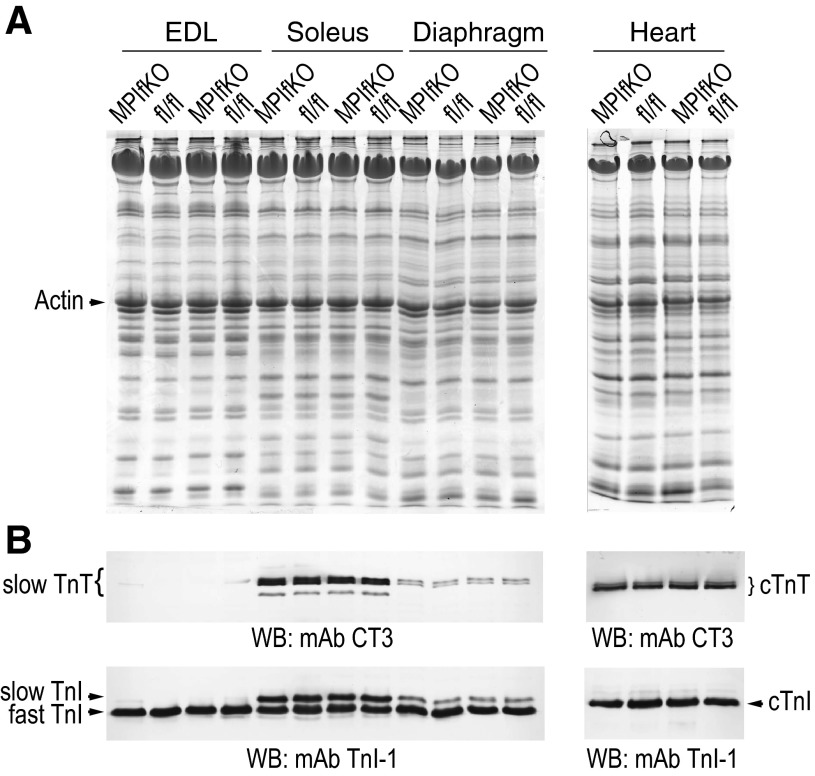

Unaltered muscle fiber type in MPIfKO mice despite metabolic defects.

Altered muscle fiber composition characterized by diminished muscle oxidative capacity through increased fast-twitch glycolytic fibers and decreased slow-twitch oxidative fibers is often seen in insulin-resistant or obese animal models and diabetic patients (8, 24, 38, 52, 73). Notably, the fiber-type switch could even precede the metabolic abnormalities (38, 49, 57, 69). Because the fast-twitch fibers are less insulin sensitive, this poses the question as to whether the metabolic disturbances observed in MPIfKO mice at such an early age are associated with a switch in a muscle fiber type triggered by muscle PIKfyve ablation. To assess this possibility, we subjected muscle protein extracts derived from young mice to immunoblotting with specific antibodies against the slow and fast isoforms of skeletal muscle troponin subunits, as we described previously (15–17). We examined EDL, soleus, and diaphragm muscles, which have distinct muscle fiber compositions and contractile properties, with the glycolytic EDL being enriched in fast-twitch fibers, the oxidative soleus being enriched in slow-twitch fibers, and the diaphragm having mixed fiber type composition. Hearts were also subjected to similar analyses using cardiac-specific antibodies for troponin T and troponin I isoforms. Notably, we did not detect any shift in the fiber type composition in either skeletal muscle or heart of MPIfKO vs. littermate controls of either sex (Fig. 6, A and B, and data not shown). These results indicate that the profound muscle insulin resistance seen in MPIfKO mice did not result from slow-to-fast transition, nor did it trigger muscle fiber type switching, at least at the age tested (8 wk to 4 mo old; Fig. 6 and data not shown). Additionally, these data also demonstrate that, whereas MPIfKO hearts were relatively smaller if normalized for body weight (see Fig. 2D), there was no notable alteration in cardiac-specific contractile protein isoforms (Fig. 6). This result, coupled with the observed lack of significant changes in cardiac function analyzed in adult mice by ex vivo working heart preparations (data not shown) (14), is suggestive of a lack of cardiac phenotype in MPIfKO mice.

Fig. 6.

Unaltered muscle fiber type in MPIfKO mice despite metabolic abnormalities. A and B: protein extracts, prepared by homogenization in sample buffer of fresh muscle tissues from MPIfKO and control female mice (8 wk old), were subjected to SDS-PAGE in duplicate gels. Gels were either stained with Coomassie Blue R250 (A) or processed for immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies (mAb) troponin I-1 (TnI-1) against muscle-specific myofilament protein troponin I (TnI), recognizing skeletal muscle fast/slow TnI and the cardiac muscle (c) TnI, and with mAb CT3 against muscle-specific troponin T (TnT), recognizing skeletal muscle slow TnT and the cardiac muscle TnT (B). Shown are Coomassie blue (A) and chemical detections (B) from a representative experiment. No changes were found between the control and MPIfKO mice in any of the muscles in 3 independent experiments.

Normolipidemia in MPIfKO mice.

To determine whether the increased TG accumulation in the expanding fat depots of MPIfKO mice triggers derangement in systemic lipid homeostasis, which in turn may contribute to muscle insulin resistance (12, 22), we examined levels of serum NEFA, TG, and cholesterol in adult or old mice. As demonstrated in Table 1, serum TG levels in 4- to 5-mo-old MPIfKO mice were statistically indistinguishable from those of age-matched controls under both fasted and random-fed conditions. Likewise, at this age, serum NEFA or cholesterol levels remained unchanged vs. age-matched controls (Table 1). Concordantly, Oil Red O staining of liver or muscle cross sections did not reveal any ectopic lipid accumulation (data not shown). Of note, as MPIfKO mice aged further and adiposity increased, serum TG levels were significantly higher as measured in ∼8.5-mo-old mice (Table 1). These data indicate that at a young age muscle insulin resistance triggers TG accumulation selectively in MPIfKO fat and that hypertriglyceridemia is manifested only later in life.

Table 1.

Serum lipids in MPIfKO and control flox/flox male mice

| Fasted Age 20–22 wk |

Random Fed Age 20–22 wk |

Random Fed Age 36–38 wk |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Lipids | PIKfyveflox/flox | MPIfKO | PIKfyveflox/flox | MPIfKO | PIKfyveflox/flox | MPIfKO |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 55.66 ± 2.32 (n = 7) | 61.35 ± 2.34 (n = 16) | 57.10 ± 0.8 (n = 5) | 60.00 ± 2.30 (n = 5) | 67.43 ± 7.08 (n = 4) | 93.73 ± 7.87 (n = 11)* |

| Nonesterified fatty acids, mEq/l | 1.31 ± 0.03 (n = 4) | 1.29 ± 0.04 (n = 11) | 0.95 ± 0.11 (n = 5) | 0.98 ± 0.12 (n = 7) | 0.91 ± 0.10 (n = 4) | 0.96 ± 0.05 (n = 11) |

| Cholesterol, mg/dl | 73.92 ± 4.51 (n = 3) | 76.83 ± 5.28 (n = 6) | ND | ND | 61.81 ± 8.65 (n = 4) | 61.16 ± 2.2 (n = 12) |

Values are means ± SE. ND, not determined.

P < 0.05.

Cellular and molecular mechanisms of increased adiposity in MPIfKO mice.

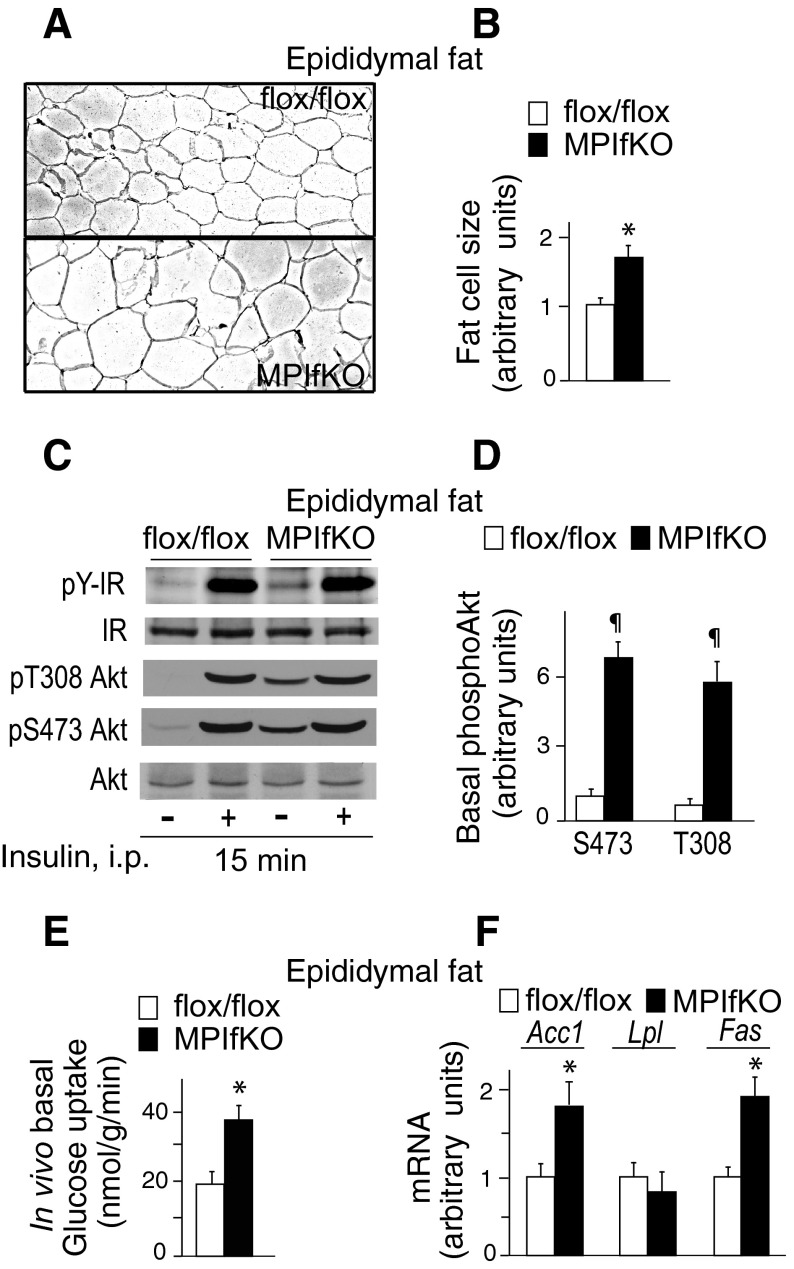

Increased TG accumulation in fat could be due to increased adipocyte size (hypertrophy) and/or adipocyte cell number (hyperplasia). To determine the mechanism underlying the increased MPIfKO fat mass, we performed morphometric analyses of epididymal fat sections from MPIfKO and PIKfyvefl/fl mice. H & E staining of paraffin-embedded sections derived from epididymal fat depots indicated that the MPIfKO fat cells had a greater size (Fig. 7A), being 162% larger compared with control fat cells (Fig. 7B). Determination of the DNA content in MPIfKO and control epididymal fat pads did not reveal significant differences (not shown). These observations are thus consistent with hypertrophy being the main cause for the increased adiposity in MPIfKO mice.

Fig. 7.

Hypertophy, augmented basal Akt phosphorylation, and in vivo glucose uptake in MPIfKO fat. A and B: hematoxylin and eosin staining of paraffin-embedded epididymal fat tissue sections (A) showing profound hypertrophy in MPIfKO fat, quantified in B; n = 3/genotype; *P < 0.05 vs. control mice. C and D: constitutive Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO fat. Insulin (5 U/kg) was administered ip in 14-h-starved mice. Fifteen minutes postinjection, epididymal fat tissue was isolated and subjected to Western blotting analysis (65 μg of protein) with antibodies for phospho-Thr308 Akt or phospho-Ser473 Akt, phosphotyrosine (P-Y), Akt, and insulin receptor (IR). Shown are chemiluminescence detections from a representative experiment (C) and quantitation of increased basal Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO fat relative to Ser473 phosphorylation in controls (D); n = 5/group. ¶P < 0.001 vs. control mice. E: in vivo glucose uptake in epididymal fat was measured in 14-h-starved mice that were injected ip with [3H]2DG and l-[14C]glucose, as described in materials and methods; n = 5/genotype. *P < 0.05 vs. control mice. F: gene expression in epididymal fat from 12-wk-old mice; n = 6/genotype. *P < 0.05 vs. control mice. Acc1, acetyl-CoA carboxylase1; Lpl, lipoprotein lipase; Fas, fatty acid synthase.

As indicated in Fig. 1, D and E, PIKfyve protein and activity are unaltered in WAT of MPIfKO mice, suggesting that the fat cell hypertrophy is secondary to muscle insulin resistance. MPIfKO mice exhibited hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 4G), which is thought to augment insulin action in fat by elevating GLUT4 mRNA (7, 10, 44). However, we failed to detect higher GLUT4 protein levels in fat of MPIfKO mice, as revealed by immunoblotting with anti-GLUT4 (not shown). In efforts to delineate the molecular mechanism underlying increased MPIfKO adiposity, we examined levels of Akt phosphorylation as a critical event in insulin signaling of glucose uptake/de novo lipogenesis in fat tissue. Intriguingly, we found unexpected and profound rises in basal Akt phosphorylation on both Ser473 and Thr308, with no changes in the insulin-dependent increment vs. control animals (Fig. 7, C and D). Basal IR Tyr phosphorylation, but not total IR, was slightly increased as well (Fig. 7C). These data indicate constitutive Akt phosphorylation in fat tissue of MPIfKO mice.

We surmised that constitutively active Akt may increase basal glucose flux in fat tissue, which could promote de novo lipogenesis (DNL), inducing expression levels of the enzymes involved in DNL. To test whether such a mechanism underlies the increased fat mass in MPIfKO mice, we first assessed the in vivo glucose uptake by adipose tissue. Intriguingly, we observed an ∼80% greater basal glucose uptake in epididymal fat from MPIfKO mice vs. control mice (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, examination of expression levels of genes encoding key enzymes of fatty acid synthesis, such as Acc and Fas, which are under transcriptional regulation of the carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (25), revealed that both Acc and Fas mRNA levels were increased significantly in epididymal fat in MPIfKO compared with control mice (Fig. 7F). Lpl levels were unaltered (Fig. 7F). Jointly, these data are consistent with the notion that the increased MPIfKO fat mass is at least in part related to increased basal glucose flux in adipose tissue and DNL.

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to reveal for the first time the in vivo relationship between systemic glucose homeostasis and PIKfyve in skeletal muscle, the tissue responsible for the majority of postprandial glucose disposal (2, 19). To this end, we took advantage of our recent success in generating the first mouse with a pikfyve floxed allele (29) to develop a new model with pikfyve conditional inactivation specifically in muscle. We show here that the MPIfKO mice display systemic glucose intolerance and impaired insulin-induced glucose uptake in muscle at an early age and on a regular diet. Our data demonstrate genetically that PIKfyve is essential for normal muscle insulin signaling to GLUT4 and provide the first in vivo evidence for the central role of muscle PIKfyve in the mechanisms regulating glucose homeostasis. In addition, we found that these metabolic disturbances are followed by markedly increased adiposity and hyperinsulinemia but not dyslipidemia. Notably, the combined phenotype manifested by the MPIfKO mouse closely recapitulates the cluster of typical features in clinical insulin resistance, a condition often referred to as prediabetes that includes systemic glucose intolerance and insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and increased visceral obesity, but without dyslipidemia (1, 53). For these reasons, the MPIfKO mouse represents a valuable novel tool for exploring new preclinical strategies to improve treatments in individuals with prediabetes. Strikingly, except for increased adiposity, our MPIfKO mice closely recapitulate the phenotypic defects in muscle-specific GLUT4 KO mice (84), i.e., severely perturbed glucose homeostasis at an early age, hyperinsulinemia, normolipidemia, and muscle insulin resistance, indicating that muscle PIKfyve is likely to play a prominent role in most if not all metabolic effects of insulin.

Several lines of evidence in the present study indicate that the primary defect responsible for whole body glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice is the impairment of GLUT4 translocation/glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (Fig. 5, A, B, and D). These data corroborate previous results in 3T3-L1 adipocytes implicating PIKfyve as a positive effector in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport based on perturbation experiments by means of siRNA-mediated protein knockdown or dominant-negative or chemical inhibition (30, 34, 36, 45). Concordantly, ectopic expression of an enzymatically inactive point mutant of Sac3, the antagonistic phosphatase that associates with PIKfyve and turns over PtdIns(3,5)P2, has a positive effect (31, 33, 65). Our current study confirms and expands these findings by providing the first evidence that PIKfyve also positively affects GLUT4 translocation/glucose entry in skeletal muscle and that this role has systemic consequences. Importantly, whereas increased visceral obesity was apparent as MPIfKO mice aged, its contribution to the dysregulated muscle glucose metabolism is highly unlikely, at least until 6 mo of age, because of the following considerations. First, arrested 2DG uptake in response to insulin, as documented both ex vivo and in vivo in skeletal muscles (Fig. 5, A and B), was evident at an early age prior to increased body weight and adiposity (Fig. 2). Concordantly, at this early age, we observed impaired insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation to the plasma membrane in MPIfKO muscle, with a concomitant increase of GLUT4 in intracellular membranes, whereas total GLUT4 content remained unaffected (Fig. 5D). Second, despite increased lipid accumulation in WAT, serum TG and NEFA in both fasted and fed states were normal in MPIfKO mice until late adulthood (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Third, Oil Red O staining of both liver and muscle cross sections in 6-mo-old mice failed to detect abnormal lipid accumulation in these tissues (data not shown). These observations rule out potential lipotoxicity-induced insulin resistance in muscle or liver, which is known to contribute to systemic glucose disequilibrium (11, 60), at least up to the age of unaltered TG/NEFA levels.

An important insight in the current study is the delineation of a potential molecular mechanism by which loss of PIKfyve suppresses GLUT4 translocation in skeletal muscle. Thus, the attenuated muscle Akt phosphorylation in response to a longer, but not shorter, time period of in vivo insulin administration (Fig. 5E) is consistent with accelerated Akt dephosphorylation under PIKfyve loss. These data complement observations in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and L6 cells, where perturbations in PIKfyve protein or lipid product levels were found to negatively affect insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation (20, 30, 34, 36). Whereas the exact molecular mechanism for the lack of sustained Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO muscle remains an important goal for future investigation, it is worth emphasizing that, similarly to insulin, the PIKfyve lipid product PtdIns5P is found to be a powerful inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) (56, 74, 77) that dephosphorylates both phospho-Thr308 and phospho-Ser473 in Akt (48). These data support the notion that PtdIns5P, which is elevated by acute insulin in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and L6 myotubes (20, 68), may mediate insulin's effect on PP2A inhibition. It is significant to note that in prediabetes and T2D, insulin action fails to downregulate the muscle PP2A catalytic subunit (27), making the predicted mechanism of PtdIns5P-mediated PP2A inhibition clinically important. It is also possible that in addition to prematurely attenuating Akt phosphorylation, PIKfyve ablation dysregulates other steps in the complex molecular network and mechanisms mediating insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation, one and foremost being PtdIns(3,5)P2-sensitive endosome plasticity (71).

Our findings for systemic insulin resistance in MPIfKO mice preceding the increased body weight gain suggest that MPIfKO fat tissue has undergone an adaptive expansion as a compensatory mechanism to counterbalance the reduced glucose utilization by insulin in skeletal muscle and maintain fasting normoglycemia, as observed previously in MIRKO mice (44). In our study, the prospect for glucose shunting into fat depots was particularly apparent under basal conditions, as evidenced by the striking increases in in vivo basal glucose uptake in MPIfKO fat tissue (Fig. 7F). Our findings for a profound constitutive Akt phosphorylation in MPIfKO fat (Fig. 7, C and D), likely due to chronic hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 4G), offer an insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the increased basal glucose flux into fat. This, together with data for induced gene expression of key lipogenic enzymes (Fig. 7F), supports the notion for accelerated de novo fatty acid synthesis/TG storage contributing partly to the marked increases in MPIfKO fat mass (Fig. 2B) and fat cell hypertrophy (Fig. 7, A and B). It is likely that this mechanism maintains fasting glucose at normal levels in MPIfKO mice, at least up to 5 mo of age (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, we surmise that the greater hyperinsulinemia in mature MPIfKO mice (Fig. 4G), together with elevated adiposity owing to increased glucose influx/de novo lipogenesis in fat tissue, may account for less severe insulin resistance in the older vs. younger mice. It is also possible that additional yet-to-be identified mechanisms may operate in parallel to account for the trend toward increased food intake (Fig. 3A) and adiposity in MPIfKO mice. Among those, one could envision dysregulated secretory function of skeletal muscle (54, 81) in the absence of PIKfyve, the molecule that governs exocytosis/secretion of numerous bioactive molecules (71). Further insight into this possibility is an important goal in future research.

A striking observation in the current study was that animal growth and development were unaffected by muscle PIKfyve ablation. Neither muscle abnormalities at birth nor any premature lethality of MPIfKO mice were noted during the period of our study (12 mo). This finding was surprising given PIKfyve's vital role in early growth and development, as evidenced by preimplantation lethality of the global KO model (29). One possible explanation is that PIKfyve becomes dispensable after the onset of MCK expression that starts at E17 and peaks at postnatal day 10 (5). Our data further suggest that PIKfyve is also dispensable for muscle fiber-type determination, as evidenced by the normal fiber-type composition in MPIfKO muscles (Fig. 6). These findings further emphasize that the metabolic abnormalities in MPIfKO mice are not a consequence of the fiber-type switching as seen in humans or animal models with metabolic disturbances (38, 69). In addition, the unaltered fiber-type composition corroborates the notion that PIKfyve is not a prerequisite for the skeletal or cardiac muscle contractile function, at least at the age tested. However, advanced age and/or exercise/diet challenges may disclose contractile defects in MPIfKO mice and should be addressed in future studies.

Whereas PIKfyve acts downstream of PI3Ks, which one of the three PI3K classes is the in vivo enzyme supplying the PtdIns3P precursor for PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis is a matter of speculation, with the class III/Vps34 lipid kinase presumed to be a main source (71). Comparing our MPIfKO mice to the currently available mouse models with muscle-specific ablation (also controlled by the MCK promoter) of class 1A PI3Ks or class III/Vps34 lipid kinases provides important clues to this issue. Thus, whereas the muscle-specific PI3Kr1-KO mouse has normal systemic glucose homeostasis, when combined with global PI3Kr2 deletion, severe metabolic defects are manifested. Remarkably, some of these abnormalities closely resemble those found in MPIfKO mice, including systemic glucose intolerance, muscle insulin resistance, increased adiposity, and hyperlipidemia in older mice (50). Furthermore, similarly to MPIfKO, muscle PI3Kr1/PI3Kr2 KO mice live to late adulthood. On the other hand, contrary to MPIfKO, the muscle-specific Vps34 KO mice die between 5 and 13 wk of age due to heart failure (37). These data are thus consistent with at least some of the metabolic defects in PI3Kr1/PI3Kr2 KO mice being dependent on downstream PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis and promote the idea that, in vivo, class 1A PI3Ks are likely a key supplier of the PtdIns3P precursor for PIKfyve, as suggested previously by cell studies (62). Supporting this notion are data from transcriptome analysis in fat tissue of subjects with metabolic syndrome revealing a strong correlation of PIKFYVE and PIK3CA (class 1A PI3K p110α) but not VPS34 expression levels with plasma lipid metabolites that inversely affect insulin resistance (51).

In conclusion, our current study demonstrates an unexpected key role of PIKfyve in muscle insulin sensitivity and in vivo regulation of glucose balance, revealing the PIKfyve pathway as a potentially important pathophysiological mechanism in T2D.

GRANTS

This project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DK-058058 and AR-048816; A. Shisheva and J. P. Jin), the WSU Office of the Vice President for Research under the auspices of cardiovascular adaptation multidisciplinary incubator program (J. P. Jin and A. Shisheva), the WSU School of Medicine Research Offices (A. Shisheva), and the American Diabetes Association (A. Shisheva).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

O.C.I., D.S., K.D., and H.-Z.F. performed the experiments; O.C.I., D.S., K.D., H.-Z.F., and A.S. analyzed the data; O.C.I., D.S., H.-Z.F., G.D.C., J.-P.J., and A.S. interpreted the results of the experiments; O.C.I., D.S., and H.-Z.F. prepared the figures; O.C.I., D.S., H.-Z.F., G.D.C., and J.-P.J. edited and revised the manuscript; O.C.I., D.S., K.D., H.-Z.F., G.D.C., J.-P.J., and A.S. approved the final version of the manuscript; A.S. contributed to the conception and design of the research; A.S. drafted the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jim Granneman, Center for Integrative Metabolic and Endocrine Research, Wayne State University (WSU), for generously allowing us to use the indirect calorimeter and EcoMRI. We thank Linda McCraw for the outstanding secretarial assistance. A. Shisheva expresses gratitude to the late Violeta Shisheva for the many years of support.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdul-Ghani MA, DeFronzo RA. Pathophysiology of prediabetes. Curr Diab Rep 9: 193–199, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biddinger SB, Kahn CR. From mice to men: insights into the insulin resistance syndromes. Annu Rev Physiol 68: 123–158, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Björnholm M, Zierath JR. Insulin signal transduction in human skeletal muscle: identifying the defects in Type II diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 354–357, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bridges D, Ma JT, Park S, Inoki K, Weisman LS, Saltiel AR. Phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate plays a role in the activation and subcellular localization of mechanistic target of rapamycin 1. Mol Biol Cell 23: 2955–2962, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruning JC, Michael MD, Winnay JN, Hayashi T, Horsch D, Accili D, Goodyear LJ, Kahn CR. A muscle-specific insulin receptor knockout exhibits features of the metabolic syndrome of NIDDM without altering glucose tolerance. Mol Cell 2: 559–569, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carlson FL. Histotechnology: A Self-Instructional Text (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: ASCP, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Charron MJ, Katz EB, Olson AL. GLUT4 gene regulation and manipulation. J Biol Chem 274: 3253–3256, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen M, Feng HZ, Gupta D, Kelleher J, Dickerson KE, Wang J, Hunt D, Jou W, Gavrilova O, Jin JP, Weinstein LS. Gsα deficiency in skeletal muscle leads to reduced muscle mass, fiber-type switching, and glucose intolerance without insulin resistance or deficiency. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C930–C940, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cho H, Mu J, Kim JK, Thorvaldsen JL, Chu Q, Crenshaw EB, 3rd, Kaestner KH, Bartolomei MS, Shulman GI, Birnbaum MJ. Insulin resistance and a diabetes mellitus-like syndrome in mice lacking the protein kinase Akt2 (PKB beta). Science 292: 1728–1731, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cusin I, Terrettaz J, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Zarjevski N, Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F, Jeanrenaud B. Hyperinsulinemia increases the amount of GLUT4 mRNA in white adipose tissue and decreases that of muscles: a clue for increased fat depot and insulin resistance. Endocrinology 127: 3246–3248, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. DeFronzo RA. Insulin resistance, lipotoxicity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerosis: the missing links. The Claude Bernard Lecture 2009. Diabetologia 53: 1270–1287, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deng Y, Scherer PE. Adipokines as novel biomarkers and regulators of the metabolic syndrome. Ann NY Acad Sci 1212: E1–E19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Farese RV, Sajan MP, Yang H, Li P, Mastorides S, Gower WR, Jr, Nimal S, Choi CS, Kim S, Shulman GI, Kahn CR, Braun U, Leitges M. Muscle-specific knockout of PKC-lambda impairs glucose transport and induces metabolic and diabetic syndromes. J Clin Invest 117: 2289–2301, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feng HZ, Biesiadecki BJ, Yu ZB, Hossain MM, Jin JP. Restricted N-terminal truncation of cardiac troponin T: a novel mechanism for functional adaptation to energetic crisis. J Physiol 586: 3537–3550, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feng HZ, Chen M, Weinstein LS, Jin JP. Improved fatigue resistance in Gsα-deficient and aging mouse skeletal muscles due to adaptive increases in slow fibers. J Appl Physiol 111: 834–843, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feng HZ, Hossain MM, Huang XP, Jin JP. Myofilament incorporation determines the stoichiometry of troponin I in transgenic expression and the rescue of a null mutation. Arch Biochem Biophys 487: 36–41, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feng HZ, Wei B, Jin JP. Deletion of a genomic segment containing the cardiac troponin I gene knocks down expression of the slow troponin T gene and impairs fatigue tolerance of diaphragm muscle. J Biol Chem 284: 31798–31806, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gonzales AM, Orlando RA. Role of adipocyte-derived lipoprotein lipase in adipocyte hypertrophy. Nutr Metab (Lond) 4: 22, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Graham TE, Kahn BB. Tissue-specific alterations of glucose transport and molecular mechanisms of intertissue communication in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res 39: 717–721, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grainger DL, Tavelis C, Ryan AJ, Hinchliffe KA. Involvement of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate in insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in the L6 myotube model of skeletal muscle. Pflugers Arch 462: 723–732, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gregoire FM, Zhang Q, Smith SJ, Tong C, Ross D, Lopez H, West DB. Diet-induced obesity and hepatic gene expression alterations in C57BL/6J and ICAM-1-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 282: E703–E713, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guilherme A, Virbasius JV, Puri V, Czech MP. Adipocyte dysfunctions linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9: 367–377, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hamada T, Arias EB, Cartee GD. Increased submaximal insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in mouse skeletal muscle after treadmill exercise. J Appl Physiol 101: 1368–1376, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. He J, Watkins S, Kelley DE. Skeletal muscle lipid content and oxidative enzyme activity in relation to muscle fiber type in type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabetes 50: 817–823, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Herman MA, Peroni OD, Villoria J, Schön MR, Abumrad NA, Blüher M, Klein S, Kahn BB. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose tissue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature 484: 333–338, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hoffman NJ, Elmendorf JS. Signaling, cytoskeletal and membrane mechanisms regulating GLUT4 exocytosis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 22: 110–116, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Højlund K, Poulsen M, Staehr P, Brusgaard K, Beck-Nielsen H. Effect of insulin on protein phosphatase 2A expression in muscle in type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Invest 32: 918–923, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang S, Czech MP. The GLUT4 glucose transporter. Cell Metab 5: 237–252, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Delvecchio K, Xie Y, Jin JP, Rappolee D, Shisheva A. The phosphoinositide kinase PIKfyve Is vital in early embryonic development: preimplantation lethality of PIKfyve−/− embryos but normality of PIKfyve+/− mice. J Biol Chem 286: 13404–13413, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Dondapati R, Shisheva A. ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve interaction and role in insulin-regulated GLUT4 translocation and glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Exp Cell Res 313: 2404–2416, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Fenner H, Shisheva A. PIKfyve-ArPIKfyve-Sac3 core complex: contact sites and their consequence for Sac3 phosphatase activity and endocytic membrane homeostasis. J Biol Chem 284: 35794–35806, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Fligger J, Delvecchio K, Shisheva A. ArPIKfyve regulates Sac3 protein abundance and turnover: disruption of the mechanism by Sac3I41T mutation causing Charcot-Marie-Tooth 4J disorder. J Biol Chem 285: 26760–26764, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Ijuin T, Takenawa T, Shisheva A. Sac3 is an insulin-regulated phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate phosphatase: gain in insulin responsiveness through Sac3 down-regulation in adipocytes. J Biol Chem 284: 23961–23971, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Mlak K, Shisheva A. Requirement for PIKfyve enzymatic activity in acute and long-term insulin cellular effects. Endocrinology 143: 4742–4754, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. Localized PtdIns 3,5-P2 synthesis to regulate early endosome dynamics and fusion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C393–C404, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ikonomov OC, Sbrissa D, Shisheva A. YM201636, an inhibitor of retroviral budding and PIKfyve-catalyzed PtdIns(3,5)P2 synthesis, halts glucose entry by insulin in adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382: 566–570, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jaber N, Dou Z, Chen JS, Catanzaro J, Jiang YP, Ballou LM, Selinger E, Ouyang X, Lin RZ, Zhang J, Zong WX. Class III PI3K Vps34 plays an essential role in autophagy and in heart and liver function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 2003–2008, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jensen CB, Storgaard H, Madsbad S, Richter EA, Vaag AA. Altered skeletal muscle fiber composition and size precede whole-body insulin resistance in young men with low birth weight. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 1530–1534, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones DR, Foulger R, Keune WJ, Bultsma Y, Divecha N. PtdIns5P is an oxidative stress-induced second messenger that regulates PKB activation. FASEB J 27: 1644–1656, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kandror KV, Pilch PF. The sugar is sIRVed: sorting Glut4 and its fellow travelers. Traffic 12: 665–671, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kandror KV, Yu L, Pilch PF. The major protein of GLUT4-containing vesicles, gp160, has aminopeptidase activity. J Biol Chem 269: 30777–30780, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Karlsson HK, Zierath JR. Insulin signaling and glucose transport in insulin resistant human skeletal muscle. Cell Biochem Biophys 48: 103–113, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim J, Arias EB, Cartee GD. Effects of gender and prior swim exercise on glucose uptake in isolated skeletal muscles from mice. J Physiol Sci 56: 305–312, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim JK, Michael MD, Previs SF, Peroni OD, Mauvais-Jarvis F, Neschen S, Kahn BB, Kahn CR, Shulman GI. Redistribution of substrates to adipose tissue promotes obesity in mice with selective insulin resistance in muscle. J Clin Invest 105: 1791–1797, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Koumanov F, Pereira VJ, Whitley PR, Holman GD. GLUT4 traffic through an ESCRT-III-dependent sorting compartment in adipocytes. PLoS One 7: e44141, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kurlawalla-Martinez C, Stiles B, Wang Y, Devaskar SU, Kahn BB, Wu H. Insulin hypersensitivity and resistance to streptozotocin-induced diabetes in mice lacking PTEN in adipose tissue. Mol Cell Biol 25: 2498–2510, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Levin MC, Monetti M, Watt MJ, Sajan MP, Stevens RD, Bain JR, Newgard CB, Farese RV, Sr, Farese RV., Jr Increased lipid accumulation and insulin resistance in transgenic mice expressing DGAT2 in glycolytic (type II) muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1772–E1781, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liao Y, Hung MC. Physiological regulation of Akt activity and stability. Am J Transl Res 2: 19–42, 2010 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM. Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature 418: 797–801, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Luo J, Sobkiw CL, Hirshman MF, Logsdon MN, Li TQ, Goodyear LJ, Cantley LC. Loss of class IA PI3K signaling in muscle leads to impaired muscle growth, insulin response, and hyperlipidemia. Cell Metab 3: 355–366, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Morine MJ, Tierney AC, van Ommen B, Daniel H, Toomey S, Gjelstad IM, Gormley IC, Pérez-Martinez P, Drevon CA, López-Miranda J, Roche HM. Transcriptomic coordination in the human metabolic network reveals links between n-3 fat intake, adipose tissue gene expression and metabolic health. PLoS Comput Biol 7: e1002223, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Oberbach A, Bossenz Y, Lehmann S, Niebauer J, Adams V, Paschke R, Schon MR, Bluher M, Punkt K. Altered fiber distribution and fiber-specific glycolytic and oxidative enzyme activity in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 29: 895–900, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Patti ME. Gene expression in humans with diabetes and prediabetes: what have we learned about diabetes pathophysiology? Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 7: 383–390, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8: 457–465, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pendaries C, Tronchere H, Arbibe L, Mounier J, Gozani O, Cantley L, Fry MJ, Gaits-Iacovoni F, Sansonetti PJ, Payrastre B. PtdIns5P activates the host cell PI3-kinase/Akt pathway during Shigella flexneri infection. EMBO J 25: 1024–1034, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ramel D, Lagarrigue F, Dupuis-Coronas S, Chicanne G, Leslie N, Gaits-Iacovoni F, Payrastre B, Tronchere H. PtdIns5P protects Akt from dephosphorylation through PP2A inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 387: 127–131, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Roth RJ, Le AM, Zhang L, Kahn M, Samuel VT, Shulman GI, Bennett AM. MAPK phosphatase-1 facilitates the loss of oxidative myofibers associated with obesity in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 3817–3829, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rowland AF, Fazakerley DJ, James DE. Mapping insulin/GLUT4 circuitry. Traffic 12: 672–681, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rudich A, Klip A. Push/pull mechanisms of GLUT4 traffic in muscle cells. Acta Physiol Scand 178: 297–308, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Samuel VT, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Lipid-induced insulin resistance: unravelling the mechanism. Lancet 375: 2267–2277, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev 87: 507–520, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sbrissa D, Ikonomov O, Shisheva A. Selective insulin-induced activation of class I(A) phosphoinositide 3-kinase in PIKfyve immune complexes from 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 181: 35–46, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Deeb R, Shisheva A. Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate biosynthesis is linked to PIKfyve and is involved in osmotic response pathway in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 277: 47276–47284, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]