Abstract

Insulin therapy for Type 1 diabetes (T1D) does not prevent serious long-term complications including vascular disease, neuropathy, retinopathy and renal failure. Stem cells, including amniotic fluid-derived stem (AFS) cells--highly expansive, multipotent, and non-tumorigenic cells--could serve as an appropriate stem cell source for β-cell differentiation. In the current study we tested whether nonhuman primate (nhp) AFS cells ectopically expressing key pancreatic transcription factors were capable of differentiating into a beta-like cell phenotype in vitro. NHPAFS cells were obtained from Cynomolgus monkey amniotic fluid by immunomagnetic selection for a CD117 (c-kit) positive population. RT-PCR for endodermal and pancreatic lineage-specific markers was performed on AFS cells after adenovirally transduced expression of PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA. Expression of MAFA was sufficient to induce insulin mRNA expression in nhpAFS cell lines, whereas a combination of MAFA, PDX1 and NGN3further induced insulin expression, as well as induced the expression of other important endocrine cell genes such as glucagon, NEUROD1, NKX2.2, ISL1 and PCSK2. Higher induction of these and other important pancreatic genes was achieved by growing the triply infected AFS cells in media supplemented with a combination of B27, betacellulin and nicotinamide, as well as culturing the cells on extra-cellular matrix coated plates. The expression of pancreatic genes such as NEUROD1, glucagon and insulin progressively decreased with the decline of adenovirally-expressed PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA. Together, these experiments suggest that forced expression of pancreatic transcription factors in primate AFS cells induces them towards the pancreatic lineage.

Keywords: amniotic fluid stem cells, differentiation, diabetes, pancreas, beta-cells, cell therapy, nonhuman primates

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a vast and growing medical problem in the United States and world-wide, with a huge impact on healthcare costs [Adeghate et al., 2006; Tao and Taylor, 2010]. The disease affects over 18 million people in the U.S. About 10% of these affected individuals have Type 1 diabetes (T1D), resulting from auto immune destruction of insulin-producing β-cells in the Islets of Langerhans of the pancreas. The majority of patients have Type 2 diabetes (T2D), which is manifested initially by insulin resistance, but often culminates in the loss of β-cell mass and a need for insulin replacement therapy [Bouwens and Rooman, 2005]. Unfortunately, consistent glucose homeostasis remains difficult to achieve with any current method of exogenous insulin replacement [Gomis and Esmatjes, 2004]. When glucose metabolism is deregulated over the long term, complications affecting the eyes, kidneys, nerves and cardiovascular system are common [Santiago, 1993; Melendez-Ramirez et al., 2010]. Only transplantation of insulin producing tissue consistently gives the desired outcomes of euglycemia and avoidance of episodes of hypoglycemia [Bigam and Shapiro, 2004; Davis and Alonso, 2004]. Islet cell transplantation has become a viable clinical modality for a selected cohort of patients with T1D. The procedure is safe and achieves improved metabolic control and quality of life [Ricordi and Strom, 2004; Poggioli et al., 2006; Ryan et al., 2006; Mineo et al., 2009]. A major drawback of this procedure is that 2-3 donor organs per recipient are required to obtain the desired islet mass [Ryan et al., 2005], as the islet cells are non-expandable and a significant proportion lose viability during islet isolation [Hering et al., 2005]. In addition, islets are lost over time after transplantation, causing about 90% of patients to require at least some re-administration of exogenous insulin [Ricordi and Strom, 2004; Leitao et al., 2008; Ichii and Ricordi, 2009]. These shortcomings cause the current supply of donated pancreata to fall far short of the medical demand by patients who would benefit from transplantation. Therefore, a major translational goal of this work is to resolve the supply/demand mismatch by developing a cell-based therapy for diabetes using amniotic fluid-derived stem (AFS) cells. AFS cells can be expanded extensively in culture, can be differentiated in vitro to cell types from all three germ layers and do not form teratomas when implanted into immunocompromised mice [De Coppi et al., 2007]. In addition, their in vivo regenerative capacity was demonstrated in two different animal models of tissue injury. AFS cells had a protective effect on the kidneys of mice with acute tubular necrosis [Perin et al., 2010] and could integrate and differentiate into epithelial lineages of the lung after injury [Carraro et al., 2008]. Thus, the accumulating data to date suggests that AFS cells may represent an intermediate phenotype between ES cells and various lineage-restricted adult stem cells. The choice to use non-human primate AFS cells arose from the desire to develop a clinically applicable cell therapy for T1D using cells from unrelated allogeneic donors. Primates have been well characterized as animal models of both Type 2 diabetes (T2D) [Wagner et al., 2006] and islet/cell transplantation in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced T1D [Kenyon et al., 1999a; Kenyon et al., 1999b; Han et al., 2002; Berman et al., 2007].

Despite recent advances, no in vitro approach has yet been documented in which human, non-embryonic, stem cells can safely, reproducibly and efficiently be differentiated into glucose-responsive, insulin-producing β-like cells or islet-like structures at a scale suitable for clinical use [Raikwar and Zavazava, 2009]. In contrast, multiple laboratories have successfully generated pancreatic endocrine cells or more differentiated insulin-producing cells and islet-like clusters from embryonic stem cells in vitro [D'Amour et al., 2006; Jiang et al., 2007a; Jiang et al., 2007b; Cai et al., 2009]. The formation of glucose-responsive insulin-producing β-cells capable of treating hyperglycemia in mice have been produced by recapitulating embryonic pancreatic development in vitro starting from embryonic stem cells [Kroon et al., 2008]. However, in all cases the efficiency of differentiation is low, while residual undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells have high potential to form teratomas, thus precluding their clinical application [Martin, 1981; Thomson et al., 1998]. In fact, one study that used insulin-producing cells generated from ES cells failed due to teratoma formation [Fujikawa et al., 2005]. Transplantation of purified β-cells has been shown to be as effective as transplantation of intact islets in reversing hyperglycemia suggesting that higher-order islet structure is not essential [King et al., 2007]. Stable transdifferentiation of somatic cells to insulin-producing cells has also been demonstrated starting from liver tissue [Ber et al., 2003; Kojima et al., 2003] or pancreatic exocrine cells [Zhou et al., 2008] by the forced over-expression of the pancreatic specific transcription factors. Gage et al. subjected amniotic fluid cells to combinatorial high-content screening using an adenoviral-mediated expression system to look for genes that could activate insulin promoter expression linked to a fluorescent reporter. A panel of six transcription factors was identified and included genes that had been previously shown to be critical for development of the endocrine pancreas as well as islet cell differentiation (Pdx1, NeuroD, Ngn3, Isl-1, Pax6 and MafA). However, the induction of insulin expression was relatively low in vitro and these same transplanted cells were unable to reverse hyperglycemia in an STZ-induced mouse model of diabetes [Gage et al., 2010]. This study determined whether non-human primate AFS cells could be genetically modified to a β-cell like phenotype by the transgenic over-expression of pancreatic transcription factors Pdx1, Ngn3 and MafA. Adenovirus and lentivirus were chosen because these viral reagents are easy to produce and have high transduction efficiency. In future work other types of gene transduction systems could be applied for clinical purpose. The coordinated expression of pancreatic lineage markers was tested by qRT-PCR. Alternative growth conditions that promoted the survival and sustained pancreatic differentiation of the reprogrammed AFS cells were also developed.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Non-human primate amniotic fluid was obtained from Cynomolgus monkey amniotic fluid, under a research protocol approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institution Care and Use Committee. The amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (AFS) cells were isolated by immunomagnetic-sorting for the c-kit positive population using the CD117-antibody MicroBead Kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Inc., cat no. 130-091-332). Clonal AFS lines were generated by the limiting dilution method. AFS cells were grown in modified Chang media [De Coppi et al., 2007].

Adenovirus Production

Adenovirus expressing mouse Pdx1 was a gift from Christopher Newgard and Sarah Ferber at Duke University. Adenovirus expressing mouse MafA and nuclear GFP under the control of CMV promoter was obtained from Add gene [Zhou et al., 2008]. Human NGN3 cDNA was subcloned into pShuttle CMV and pAd Track CMV vector to make a denovirus in the AdEasy viral system [Luo et al., 2007]. Adenoviruses were amplified in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Adenovirus preparations were titered by infecting 293 cells with diluted virus in 6-well plate. After 12-16 hours, cells were collected and fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with cold 100% methanol. The cells were stained with mouse anti-E2A antibody (gift from Dr. David Ornelle) and Cy5-goatanti-mouse (Fab')2 antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Inc.). The percentage of infected cells was determined by flow cytometry and the infectious units per cell was calculated based on the Poisson distribution. Viral-mediated gene expression was confirmed by immunostaining with specific antibodies: Anti-Pdx1 monoclonal antibody (Clone 267712) from R&D Systems, rabbit anti-human NGN3 polyclonal antibody (H-80) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. and rabbit anti-mouse MAFA antibody from Abcam.

Lentivirus Production

A 3-in-1 lentiviral vector (pLenti-MafA-Ngn3-Pdx1) expressing the human MAFA, NGN3 and PDX1 genes was purchased from Applied Biological Materials (ABM, Richmond, BC, Canada). The MAFA gene was under the control of the mini CMV promoter while NGN3 and PDX1 were under the control of the PGK promoter. Lentivirus was produced in 293T cells following the methods of Kutner et al. [Kutner et al., 2009]. Crude supernatants containing lentiviral particles was concentrated with Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.).

AFS Cell Infection and Differentiation

NhpAFS cells were seeded at 60-70% confluence 24 hours before adenoviral infection. Just prior to viral infection, culture media was aspirated and cells were rinsed twice with 1×PBS. Adenovirus at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) in serum free α-MEM was added to the cells at minimal volume that ensures cell coverage. Plates were rocked gently every 15 minutes for the first hour and incubated for another 2-3 hours at 37°C in CO2 incubator after which the infection media was replaced with normal culture media. Differentiation inducing media contained α-MEM supplemented with 2% B27 (Invitrogen), 10 ng/ml Betacellulin (Peprotech) and 10mM Nicotinamide (Sigma).

Quantitative Reverse transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from virally-infected and uninfected control AFS cells using PerfectPure RNA cultured cell kit (5 Prime Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) and treated with DNase according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA was prepared using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Forter City, CA) . qPCR was performed in 20 μl reactions in 96-well plates using cDNA samples from 6.25 ng of total RNA. Taqman probes (Applied Biosystems) specific for primate genes are listed in Supplemental Table 1. For Insulin detection, two primers, NHPINS-F29 (5′-aggtcagcaagcaggtcact-3′) and NHPINS-R151 (5′-cacaggtgctggttcacaaa-3′) were designed based on primate insulin cDNA sequence (Accession Number J00336.1 gi:342121). qPCR was performed with these primers in presence of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in an ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System. For insulin qPCR there was only one peak in the dissociation curve. Insulin PCR product was sequenced to confirm specificity of the primers and to show that it matched the preproinsulin sequence obtained from monkey pancreas extracted cDNA [Wetekam et al., 1982]. The undetectable level of fluorescence was set at a cycle threshold (Ct) of 38.

For detection of exogenous (adenovirally expressed) PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA, AFS cells were transduced at an MOI of 100 and then cultured in modified Chang media (the same media AFS cells are grown in to maintain them in their undifferentiated state). Total RNA from transduced cells was extracted 3, 6 and 9 days after adenovirus infection. qRT-PCR was used to detect the expression of exogenous transcription factors and endogenous pancreatic lineage marker genes. Mouse PDX1 Taqman probe (Mm00435565-m1, ABI), human NGN3 primers (hNGN3-F28 ACTGTCCAAGTGACCCGTGA, hNGN3-R232 TCAGTGCCAACTCGCTCTTAG) and GFP primers (GFP-F ACGTAAACGGCCACAAGTTC, GFP-RAAGTCGTGCTGCTTCATGTG) were used to detect exogenous gene expression of mouse PDX1, human NGN3 and mouse MAFA linked to GFP. The MafA/nGFP adenoviral construct has nuclear-expressed GFP linked with the MafA cDNA by an IRES allowing the two genes to be co-transcribed. Therefore, MAFA message was determined qRT-PCR using GFP primers and protein expression was demonstrated by the presence of nuclear GFP fluorescence, which was confirmed by MAFA immunostaining. For detection of exogenous human PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA expression from lentivirus, AFS cells were transduced with different dilutions of concentrated lentivirus. The highest concentration of lentivirus which did not show toxicity to cells in 3 days was used for the experiment. Human Pdx1 Taqman probe (Hs00426216_m1, ABI), human NGN3 primers (same as previous) and human MAFA Taqman probe (Hs001651425_s1, ABI) were used to detect exogenous gene expression from the 3-in-1 lentivirus.

Cell Viability Analysis by MTS Assay

For evaluation of cell survival, PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA adenovirus triply infected cells were cultured in 96-well plate with 100 μl of culture media pre well for different amounts of time. The 96-well plate was pre-coated with or without ECM protein including collagen IV (10 μg/cm2, Sigma C-5533), fibronectin (4 μg/cm2, Millipore FC010) and laminin (2 μg/cm2, Sigma L6274). 20 μl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) was added per well at the different time points. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 2 hours and the absorbance was read at 490 nm using SpectraMax M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA).

Results

Isolation of nonhuman primate amniotic fluid-derived stem cells

Multiple clonal lines of nonhuman primate amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (nhpAFS) were isolated from Cynomolgus monkey amniotic fluid according to the same methods employed for human AFS cells [De Coppi et al., 2007]. AFS cells were passaged between 30% and 80% confluency in order to maintain full differentiation capacity. Cell morphology of different lines was consistent with that of a fibroblast-like morphology resembling a mesenchymal stromal cell population. Given that the principle isolation criteria after c-kit selection is the adherence to tissue culture plastic, this observation is consistent with the mesenchymal origin of these cells. This phenotype was confirmed in all lines generated by the expression of typical mesenchymal stem cell markers, such as CD44 (hyaluronic acid receptor), CD73 (5′-ribonucleotide phosphohydrolase), CD90 (Thy-1) and CD146 (MCAM), plus others shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Marker expression in undifferentiated primate AFS cell clones.

| Gene | NHP7231 | NHP7405 | NHP7880 | NHP islet | ABI probe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD44 | 22.4 | 23.2 | 23.1 | 26.6 | Rh02829215_m1 |

| CD73 | 24.1 | 25.6 | 25.1 | 30.1 | Rh01573920_m1 |

| CD90 | 27.1 | 27.2 | 28.6 | 30.6 | Rh02860204_m1 |

| CD146 | 28.1 | 26.3 | 26.3 | 29.3 | Rh02861012_m1 |

| EPCAM | 32.7 | 37.4 | 36.6 | 25.4 | Rh02841959_m1 |

| SOX17 | undetectable | 31.4 | 36.9 | 33.1 | Rh02976917 s1 |

| FOXA2 | 35.9 | 37.5 | undetectable | 25.7 | Rh02819217_m1 |

| GATA4 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 27.2 | Rh02840876_m1 |

| SOX9 | 31.5 | 34.9 | 29.3 | 28.2 | Rh01001343_m1 |

| PDX1 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 27.6 | Rh02902569_m1 |

| NGN3 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 37.9 | Rh02819089_m1 |

| PAX4 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 31.3 | Rh02913666_m1 |

| NEUROD1 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 26.0 | Rh02913666_m1 |

| ISL1 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 26.3 | Rh02792708_m1 |

| PAX6 | undetectable | 33.0 | 31.0 | 27.3 | Rh02827776_m1 |

| NkX6.1 | undetectable | 30.9 | 31.0 | 28.5 | Rh02859869_m1 |

| NKX2.2 | undetectable | undetectable | 36.9 | 29.9 | Rh01119252_m1 |

| GLP1R | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 27.4 | Rh02840909_m1 |

| GlUT2 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 28.2 | Rh02828080_m1 |

| PCSK2 | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 24.4 | Rh02842756_m1 |

| INS | undetectable | undetectable | undetectable | 15.2 | See M & M |

| GCG | 36.5 | 37.5 | undetectable | 19.0 | Rh02840882_m1 |

| SST | undetectable | 29.4 | 32.7 | 25.1 | Rh02912807_m1 |

| PPY | 37.9 | 34.0 | undetectable | 27.1 | Rh02929042_m1 |

| ACTB | 17.1 | 17.2 | 17.3 | 22.0 | Rh03043379_gH |

| GAPDH | 17.4 | 19.3 | 18.1 | 22.6 | Rh02621745_g1 |

| 18srRNA | 14.2 | 13.8 | 13.7 | 13.6 | 433760F |

cDNA samples from about 6.25 ng total RNA were analyzed by qRT-PCR using ABI rhesus monkey Taqman probes or SYBR GREEN PCR (INS) system. Insulin primers were designed based on monkey insulin sequence (J00336.1). Values represent average cycle threshold (Ct) of triplicate reactions. The undetectable Ct cutoff was 38 cycle.

KEY:

Ct value <20: very high expression level

Ct value 20-25: high expression

Ct value 25-30: moderate to high expression

Ct value 30-35: low expression

Ct value 35-38: Low to negligible expression

Ct value ≥38: undetectable level

Induction of pancreatic gene expression by over-expression of pancreatic-specific transcription factors

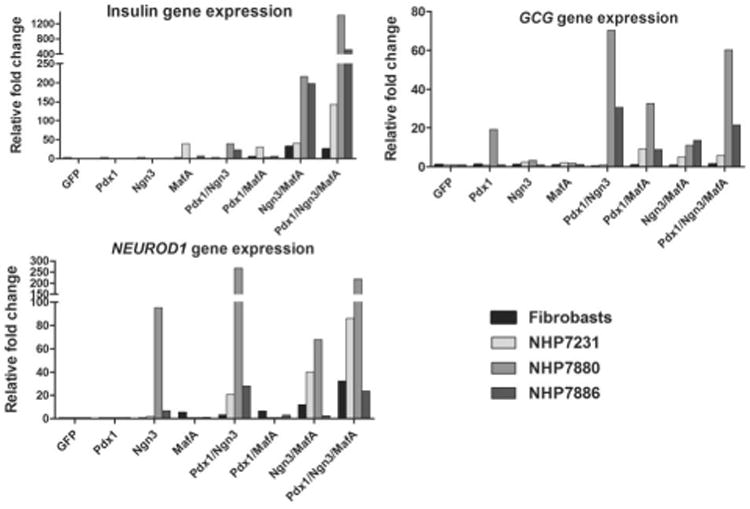

To rule out that the nhpAFS cells originated from an endodermal lineage, it was important first to verify that pancreatic-specific gene expression was not present in the undifferentiated cells. Table 1 also shows that PDX1, NGN3, PAX4, NEUROD1, ISL1, GLP1R, GLUT2, PCSK2 and INS (insulin) were undetectable by RT-PCR in all three clones analyzed. However, low level expression of PAX6 and NKX6.1 could be detected in two of the primate AFS clones (NHP7405, NHP7880), while one clone (NHP7880) showed barely detectable levels of NKX2.2 and two clones (NHP7231, NHP7405) showed GCG (glucagon) expression just above the negative cut off. We subsequently tested the effects of pancreatic-specific transcription factors, introduced via adenoviral-mediated transduction, on nhp AFS cell differentiation to pancreatic lineages. Three key transcription factors, PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA, either singly or in combination, were transiently expressed in AFS cells from the adenoviral CMV promoter and compared to the control GFP-expressing adenovirus. Figure 1 confirms that over-expressed PDX1 protein could be detected in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig.1a), while NGN3 and MAFA were only detected in the nucleus. Over 50% of the transduced cells expressed the target transcription factors. Double infection with PDX1and NGN3/GFP showed most of NGN3 positive cells (GFP) were also PDX1 positive (red) (Fig.1a). Three days after viral transduction, expression of genes, restricted to different stages along the pancreatic differentiation pathway, was assayed by qRT-PCR. The GFP control vector was unable to induce expression of any of the pancreatic marker genes tested. Each transcription factor alone was able to induce very few markers (Table 2). NGN3 can induce NeuroD1 in most of the cell lines tested but was unable to induce insulin. MAFA was able to induce insulin in some lines such as NHP7231 and to a much greater extent in NHP7405. PDX1 induced glucagons expression in two cell lines (NHP7880 and NHP7405) which had relatively high expression of endogenous PAX6 and NKX6.1 gene but could not induce glucagon expression in PAX6 and NKX6.1-low cells such as NHP7231 and NHP7886. NGN3 or MAFA was unable to induce GCG expression even in PAX6 and NKX6.1 expressing cells. Two-factor combinations were able to induce the expression of more marker genes and with a higher expression levels. For example, PDX1 and NGN3 invariably induced higher expression of NeuroD1 than NGN3 only. Three transcription factor combinations further improved the capability to induce the expression of pancreatic marker genes in all the primate AFS cell lines tested. Figure 2 shows the relative fold change in expression of selected pancreatic genes in primate AFS cells after the introduction of one, two or three transcription factors. In NHP7880 exogenous NGN3 expression induced high level NeuroD1 expression and that level was increased by the introduction of PDX1 but not by MAFA.

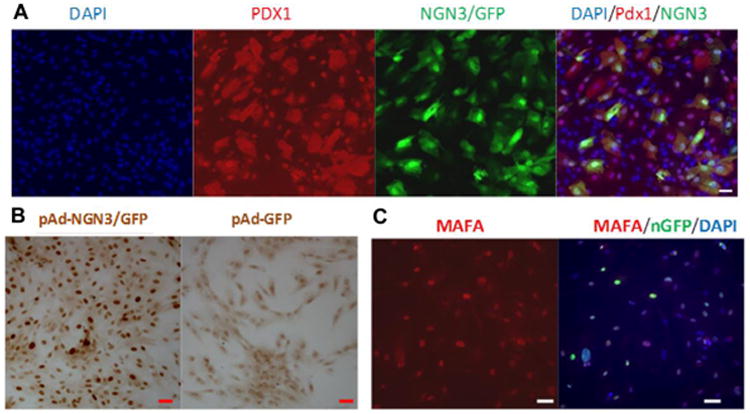

Figure 1. Ectopic expression of pancreatic genes in nonhuman primate AFS cells.

Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 each for adenoviral vectors (Ad) expressing Pdx1, Ngn3/GFP, Mafa/nGFP and their combinations. After 48 hours ectopic gene expression of PDX1 and MAFA was detected by immunofluorescence (A, C). NGN3 gene expression was detected by anti-Ngn3 immunostaining (B). Overexpressed PDX1 protein could be detected in both cytoplasm and nucleus (A) while NGN3 and MAFA were only detected in nucleus. Over 50% of the transduced cells expressed the target transcription factors. Double infection with Pdx1 and Ngn3/GFP showed that most Ngn3/GFP positive cells were also Pdx1 positive, as shown by orange staining (A). Scale bar=50 μm

Table 2. Expression of endogenous pancreatic lineage genes in nonhuman primate AFS cells over-expressing pancreatic transcription factors.

| Adenovirus transduction |

NEUROD1 | PAX6 | NKX2.2 | ISL1 | PCSK2 | INS | GCG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFP |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pdxl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ngn3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MafA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pdxl/Ngn3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pdxl/MafA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Ngn3/MafA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pdxl/Ngn3/MafA |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of pancreatic lineage gene expression in nhp skin fibroblast (gray) and 4 lines of amniotic fluid-derived stem cells (black, separated by /) 72 hours after transduction with different combinations of pancreatic transcription factors. All mRNA levels were normalized to beta-actin expression. Values represent relative fold change of mRNA level compared to GFP adenovirus transduced cells which was arbitrarily set as 1.

Key:

/ AFS7231 / ASF7880 / AFS7886 / AFS7405

/ AFS7231 / ASF7880 / AFS7886 / AFS7405

Figure 2. Expression of endogenous insulin, glucagon and NeuroD1 in nonhuman primate AFS cells overexpressing pancreatic transcription factors.

Expression data from Table 1 is presented as single graphs for insulin, glucagon and NeuroD1. Experimental details are the same as in Table 2.

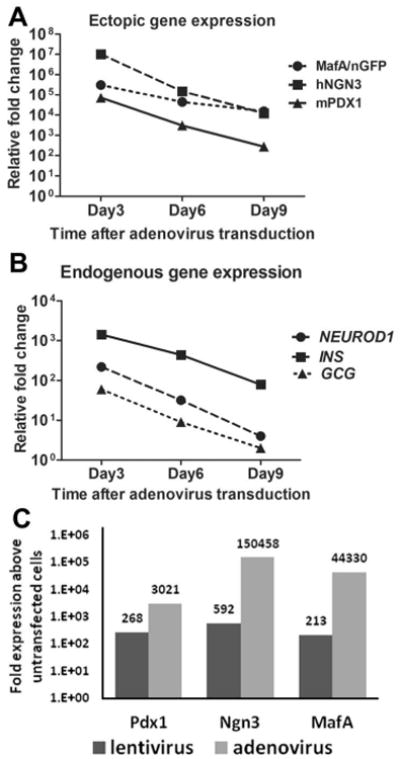

Continuous, high level PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA expression is necessary for induction and maintenance of the pancreatic gene expression

To determine the correlations between the levels of forced expressed pancreatic transcription factors (PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA) and the endogenous expression of pancreatic genes in nhpAFS cells, we measured their expression at 3, 6 and 9 days after transduction with all 3 transcription factors. Ectopic expression of the three transcription factors from the adenoviral CMV promoters is transient and decreases over time as the episomal virus is diluted during cell division. All three exogenous transcription factors reach their maximum expression on day 3 after transduction and then steadily decrease of over time (Fig 3a). Figure 3b shows that NeuroD1, insulin and glucagon expression decreases over the nine day time course, paralleling expression of the adenoviral-mediated expressed PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA . Although expression of exogenous transcription factors was still relatively high at day 9, the expression of endogenous pancreatic marker genes was barely detectable suggesting that continued high-level transcription factor expression is necessary to maintain the long-term pancreatic lineage phenotype. These results suggest that maintenance of the pancreatic phenotype is dependent on continued exogenous transcription factor expression.

Figure 3. Sustained endogenous expression of insulin, glucagon and NeuroD1 is dependent on transient over-expression of pancreatic transcription factors.

A, B. NHP7880 AFS cells were transduced with adenoviral vectors expressing Pdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa at 100 MOI each. Total RNA from transduced cells was extracted 3, 6 and 9 days after adenovirus infection. Ectopic (A) and endogenous (B) gene expression was measured using quantitative RT-PCR. C. NHPAFS7880 were transduced with a combination of adenoviral vectors expressing Pdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa at 100moi each or with a 3-in-1 lentiviral vector expressing Pdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa. Total RNAs were extracted 6 days after virus trandsduction and quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure expression of Pdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa. Data was normalized to the expression in untransduced cells.

If stable and elevated expression of PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA in nhpAFS cells is required to maintain expression of pancreatic lineage genes, a 3-in-1 lentiviral expression system may prove to be a superior approach. Lentiviral-mediated expression originates from stable integration of the transgenic construct into the host cell genome. Long-term transcription factor expression was achieved using the lentiviral system (data not shown), however it expressed approximately 10-fold less PDX1, 250-fold less NGN3 and 200-fold less MafA (Fig 3c). The lentiviral infected cells did not show elevated expression of pancreatic genes after 6 days in culture. This observation is consistent with our previous finding (Figure 3a and b) that high level transcription factor expression was necessary for the sustained expression of endogenous pancreatic marker genes.

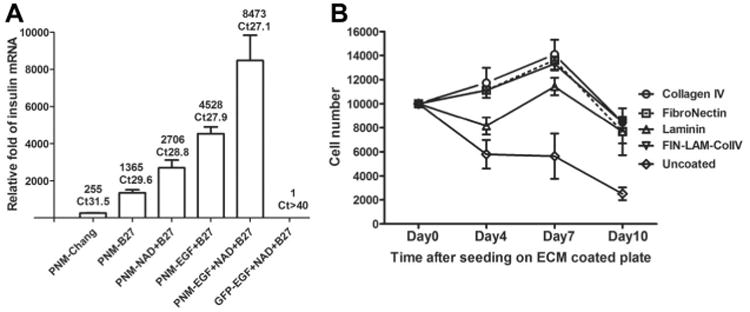

Further induction of pancreatic gene expression and cell survival by media and growth substrate modification

In all experiments described above, nhpAFS cells were grown in Chang media [Chang et al., 1982] before and after adenoviral transduction to induce pancreatic transcription factor expression. The cells are able to proliferate in Chang media and remain in an undifferentiated state even after extensive passaging. It is possible that forcing transduced AFS cells to differentiate in media that otherwise was designed to maintain them in an undifferentiated state contributed to the observed toxicity. Recent publications showed the effect of different proteins and culture media components on the differentiation of stem cells towards endodermal and pancreatic lineages [Champeris Tsaniras S, 2010; Chiou SH, 2011]. Five different “induction” culture conditions were tested: Chang medium which contains 17% ES-qualified FBS, α-MEM with B27 supplement only; α-MEM with B27 plus nicotinamide; α-MEM with B27 plus EGF (or betacellulin); α-MEM with B27 plus nicotinamide (NAD) and EGF (or betacellulin). After transduction with all three transcription factors (PNM = PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA) the cells were allowed to recover overnight in Chang media before being transferred to various induction media formulations for the five day period of differentiation. Figure 4a shows the average fold increase in insulin expression from two independent experiments on a representative nhpAFS cell line, NHP7231. Induction medium containing B27 increased insulin expression five-fold over Chang media. An additional two-fold increase was observed when NAD was added to the B27-containing media. The pair wise combination of B27 plus EGF boosted insulin expression 17.7 fold over Chang media and when all three supplements were added together, insulin expression was increased a total of 33.2 fold over baseline. However, growth factor supplementation alone, without forced expression of pancreatic transcription factors, was insufficient to induce insulin expression on its own, as shown by the lack of insulin expression when nhpAFS cells were infected with a GFP-containing adenovirus and grown in α-MEM+B27+NAD+EGF.

Figure 4. Inclusion of growth factors and extracellular matrix coating improves cell survival and insulin expression in nonhuman primate AFS cells over-expressing of pancreatic transcription factors.

A. NHPAFS 7231 were infected with combination of adenoviral vectors expressingPdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa. GFP infected cells were used as control. Cells were cultured in Chang media for 24 hours and then the media was changed to include the different supplements and growth factors, as indicated. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the relative insulin expression levels was performed 5 days later. The data represent the average relative fold compare with Ad-GFP infected cells in 2 experiments.

B. NHP7880 AFS cells were were infected with combination of adenoviral vectors expressing Pdx1, Ngn3 and Mafa at 100 MOI each. Transduced cells were cultured in Chang's media for 72 hours and collected by trypsinization. The cell were replated in96-well plate coated with different ECM protein at 10,000 cells per well (day 0). MTS assay was used to determine cell number after 4, 7 and 10 days, as indicated. The data represent average cell number of 3 wells.

Extracellular matrix components have been shown to dramatically impact the viability of cultured β-cells and augment insulin secretion [Kaido et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2008]. To further support proliferation of nhpAFS cells, genetically modified to express pancreatic transcription factors, cells were seeded on various extracellular matrix-coated dishes. For these experiments, the nhpAFS cells were first transduced with all three transcription factors (PNM = PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA) and then plated in culture dishes coated with fibronectin, laminin or collagen IV, or a 1:1:1 combination of all three (Fig 4b). Laminin coating promoted better survival than uncoated plastic, but still showed a decrease in viability after initial plating like that seen with uncoated dishes. The extent of improved viability afforded by fibronectin and collagen IV each individually were better than laminin and both of them also eliminated the cell death that occurred between zero and four days. The combination of all three ECM components (red line) was no different than fibronectin and collagen IV, each by itself, but these three groups enabled the nhpAFS cells to proliferate between plating and seven days, which had not been seen before in previous experiments. However, between seven and ten days the viability of differentiating AFS cells under all ECM-containing growth conditions declined by approximately 40%, and continued to decline thereafter. Therefore, the short term viability of the cells was dramatically increased by plating on ECM components, but long term survival was not improved.

Discussion

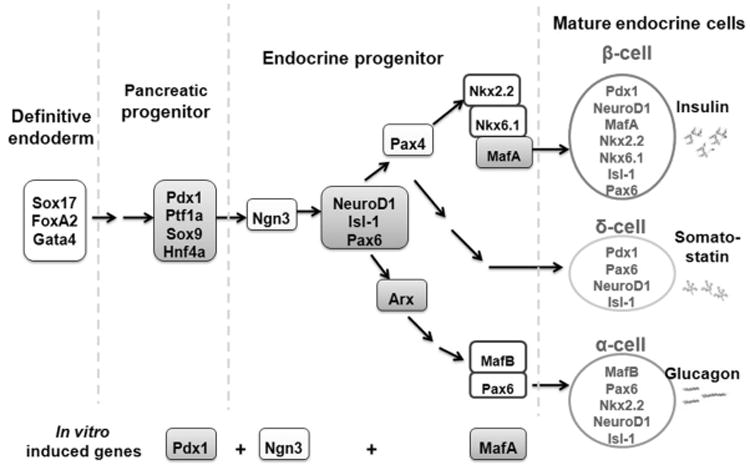

Amniotic fluid-derived stem cells, initially isolated as a c-kit positive population from second trimester human amniocentesis samples, have been shown to differentiate efficiently into mesenchymal lineages such as bone, cartilage, fat and muscle and, when cultured under specific inductive conditions, will express a subset of endodermal and ectodermal lineage markers. The fact that AFS cells do not form teratomas upon transplantation make them an attractive stem cell source for many cell therapy, regenerative medicine and tissue engineering applications. An equivalent AFS cell population has now been isolated from non-human primates with the intention of developing a clinically relevant model of diabetes for testing potential cellular therapies in our closest relatives. As a first step in that goal, this study expands the lineage repertoire of primate AFS cells and investigates whether these primitive cells can be induced to express genes associated with pancreatic endocrine differentiation by the introduction of three developmentally critical pancreatic transcription factors (Figure 5). This study goes on to show that if the partially differentiated AFS cells are exposed to growth conditions that more closely mimic the native β-cell microenvironment, enhanced pancreatic gene expression is observed. PDX1 alone, induced glucagon expression in two of the NHPAFS cell lines, NHP7880 and NHP7405, which interestingly express PAX6 and Nkx6.1 in their undifferentiated state (Table 1). Other groups have shown that PDX1 could induce high level glucagon expression in bone marrow MSCs and human pancreas-derived MSCs [Wilson et al., 2009] while a different group observed barely detectable levels of glucagon expression after PDX1 viral infection [Karnieli et al., 2007]. Similar to the data presented in Table 1, both of these studies established that there is considerable donor variation in the expression of endogenous genes in MSCs, suggesting that PDX1-dependent differentiation toward the α-cell lineage partially depends on what combination of genes are already present. Virally mediated NGN3 expression induced NeuroD1 expression in two out of the three cell lines. NeuroD1 is a key transcriptional regulator of pancreatic development and its promoter is a direct target of NGN3 [Huang et al., 2000]. In fact at least one publication introduces NeuroD1 directly, rather than depending on its activation downstream of NGN3 to induce pancreatic differentiation and insulin expression in a wide variety of cell types [Kaneto etal., 2009]. When MAFA was introduced by itself into AFS cells via viral transduction, low level insulin expression was observed in two out of the three lines. MAFA is unique inbeing expressed exclusively in the final stages of β-cell differentiation and has been shown in various cell types to be a powerful inducer of insulin expression, but not important for β-cell development [Matsuoka et al., 2007]. In addition, glucose sensitive insulin expression is synergistically enhanced when MAFA is co-expressed, or expressed in sequence after, PDX1 and either NGN3 or NeuroD1 [Andrali et al., 2008].This observation is consistent with the results presented in Table 1 and Figure 2 showing that in all three AFS cell lines, insulin expression is increased 3-7 fold whenPDX1, NGN3 and MAFA are co-infected and that this effect is not seen in primate skin fibroblasts. PDX1, MAFA and NeuroD1 can all directly bind to and activate the insulin promoter [Ohlsson et al., 1993; Naya et al., 1995; Olbrot et al., 2002; Zhang et al.,2009b] without reprogramming the cell. However, in our experiments concerted expression of other markers involved with development or maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor phenotype (Nkx2.2 and ISL1), as well as insulin processing (PCSK2), were also observed and cannot be explained by direct promoter binding. Therefore, we speculated that AFS cells did undergo a transient partial differentiation down the pancreatic lineage. The combinatorial nature of multiple transcription factors working in concert is consistent with the bulk of the literature on cellular reprogramming. Even though single transcription factors can target a specific promoter, synergistic induction is typically observed when multiple transcription factors are introduced, despite the fact that the second or third transcription factors do not bind directly to the promoter(s) of interest. For example, Gage et al. identified a combination of six adenovirally-expressed transcription factors (PDX1, NGN3, MAFA, NEUROD1, ISL1 and PAX6) that could induce the human insulin promoter in amniotic fluid-derived cells [Gage et al., 2010]. Interestingly, in their system, the combination of PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA could not induce insulin expression but the ISL1, PAX6 and MAFA triple combination could, although much less efficiently than all six. Four possibilities could explain the difference between the observations of Gage and those of ours. First, the inducibility of undifferentiated cell lines might be linked to the combination of endogenously expressed transcription factors. The NHPAFS cell line (NHP7880) that showed the highest induction of all the pancreatic genes tested already expressed the highest endogenous level of PAX6. Second, it is possible that the species difference between human and primate may have a different genetic regulation and could affect the result. Third, the differences in the assay methods. Gage used DsRed expression driven by human insulin promoter and found six transcription factor combination was the best, whereas we used qRT-PCR method to detect endogenous insulin gene expression. The synthetic human insulin promoter may not completely mimic the activity of the endogenous promoter. The epigenetic stage could be very different in endogenous promoter from exogenous promoter [Wilson et al., 2009]. And finally, experimental conditions were different: Gage used lower adenovirus titers (10 MOI of each viral construct) than we did (100 MOI); and low temperature (30 degrees) for tissue culture to control cell proliferation. Although our studies are similar to others, any changes in the methods could have a significant difference in the outcomes, as seen in many other cases.

Figure 5. Transcription factor hierarchy during pancreatic development.

Among the various transcription factors involved in the pancreas formation and beta cell differentiation, Pdx1 play a crucial role in pancreas and beta cell differentiation, and maintenance of mature beta cell function. Ngn3 is an important factor for pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation and MafA expression is induced at the final stage of beta-cell differentiation and functions as an activator of the insulin promoter.

In an ongoing attempt to generate surrogate glucose-responsive, insulin-secreting islet-like cells for the purpose of achieving a cell-based therapy for both T1D and late-stage T2D, multiple in vitro approaches have been honed to increase efficiency and functional maturity [Tateishi et al., 2008; Borowiak et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2009a; Champeris Tsaniras S, 2010; Hui et al., 2010; Mayhew and Wells, 2010]. For obvious reasons, ES and iPS cells have been the most popular starting cell populations, but the likelihood of teratoma formation and need to “finish” their differentiation in vivo has limited the excitement of this approach for clinical translation. Trans-differentiation of various somatic cell types, like hepatocytes and exocrine pancreatic cells has both conceptual and pragmatic advantages. Both of these cell types are developmentally closer to islet endocrine tissue and therefore more likely to require less extensive input. In addition, the fact that they start out as terminally differentiated cells makes teratoma formation unlikely.

In addition to ES cells and various adult somatic cells, several non-c-kit selected cell populations have also been isolated from human mid-gestation amniotic fluid, simply by virtue of their ability to adhere to tissue culture plastic, but the literature is unclear on whether any of them pass muster as bona fide stem cells. However, endocrine cell differentiation has yet to be conclusively demonstrated in any of the various amniotic fluid-derived cells. Two studies cultured human amnion epithelial cells in nicotinamide-containing media and were able to show that the resulting population was able to reverse hyperglycemia and weight loss in diabetic rodents [Wei et al., 2003; Hou et al., 2008]. However, those studies did not include sufficient characterization of the resulting beta-cell like population and failed to prove that the transplanted cells caused the diabetic reversal. Therefore, given the ease of obtaining fetal stem cells from amniotic fluid and their relative plentifulness after expansion, further investigation into their ability to differentiate into insulin-producing pancreatic progenitor cells is justified.

Although ectopic expression of transcription factors has been shown to be the principle driving force behind direct cellular reprogramming, it is clear that culture conditions also play an important role in facilitating and enhancing lineage-specific differentiation. Therefore, we postulated that the efficiency of β-cell differentiation would be improved if the culture conditions after viral transduction mimicked the native pancreatic micro-environment. Chang media was developed to provide optimal conditions for primary culture of human amniotic fluid cells and chorionic vilus sample cultures for use in karyotyping and other antenatal genetic testing [Chang et al., 1982] but may not be ideal for β-cell differentiation. Here we found that including B27, a serum replacement widely used for β-cell differentiation, enhanced insulin expression approximately five-fold above that expressed in Chang media. Also including nicotinamide, a poly adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-ribose synthetase inhibitor, lead to a two-fold further enhancement of insulin expression, consistent with studies by Otonkoski et al. showing that nicotinamide induced islet formation from pancreatic progenitor cells [Otonkoski et al., 1993]. Lastly, if betacellulin was added in combination with B27 and nicotinamide, insulin expression increased a total of 30-fold above that achieved in Chang media. Betacellulin, a member of the EGF growth factor family, was previously shown to sustain Pdx1 expression in isolated islets and promote their maturation in vitro [Cho et al., 2008]. However, reagents used at early stages of ES cell differentiation toward the beta lineage, such as Activin A and Retinoic acid, did not enhance insulin expression in our system (data not shown), suggesting that partially differentiated AFS cells can only respond to late-stage inductive signals.

Insulin mRNA was undetectable in AFS transduced with GFP adenovirus under the optimal differentiation media (Figure 4a). Thus, over-expression of the transcription factors was necessary to initiate cell differentiation. However, no c-peptide protein was detected in the PNM+EGF+NAD+B27-treated AFS cells and insulin mRNA was approximately 10,000 fold less than that produced by isolated primate islets. Differentiation of AFS, using the beta-cell differentiation protocols developed for ES cells or MSCs without transcript factor over-expression, failed to induce beta lineage marker expression.

AFS cells were originally cultured with Chang media, which contained high concentration of serum (about 16%). In differentiation medium, 2% B27 was used as a serum replacement. The low serum condition most likely caused high rate of cell death, in both transcription factor over-expressed and control cells without transcription factor expression. We do not have evidence that the medium causes selective cell survival.

Increased AFS cell death and a decreased proliferation rate was observed after adenoviral transduction compared to un-transduced controls. It has been demonstrated that extracellular matrix can support the in vitro long-term culture of pancreatic islets and protect pancreatic beta cells from apoptosis leading to improved cell survival [De Carlo et al., 2010]. It has also been reported that the peripheral extracellular matrix (ECM) of mature human pancreas contains laminin (LM), Collagen IV (Col-IV) and Fibronectin (FN) [Stendahl et al., 2009]. Therefore, these three ECM proteins were included as plastic coatings in the differentiation system and were found to improve cell survival, while the benefit to augment insulin expression is inconclusive, due to variation between the different primate AFS cell lines.

Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of the transcription factor cascade that ultimately leads to the α-, β-, and δ-cell pancreatic lineages and where the three transcription factors used in this study function in the cascade. PDX1 and NGN3 expression in primate AFS cells induced a gene expression profile indicative of the α-cell lineage. However, when MAFA was expressed in combination with PDX1 and NGN3, the marker profile more closely resembled pancreatic progenitors early in the β-cell lineage. The schematic implies a sequential expression of these transcription factors during pancreatic differentiation, however in our studies all three transcription factors were simultaneously co-expressed. Coordinated although transient expression of endogenous endodermal, endocrine and pancreatic genes suggests that some level of cellular reprogramming was achieved in the primate AFS cells. However, the resulting fairly robust expression of insulin was mostly likely a result of direct insulin promoter activation. In fact, sequential expression of PDX1, NGN3 and MAFA was less effective in inducing insulin expression than simultaneous co-expression of all three transcription factors. It is unknown whether transcription factor induced AFS cells would continue to mature in native pancreatic microenvironment, as has been demonstrated for partially differentiated ES cells [Kroon et al., 2008]. Therefore, a further characterization of the in vivo differentiation potential of partially reprogrammed AFS cells in an STZ-induced mouse model of diabetes is warranted, given their promise as an easily obtained, highly expansive, relatively plastic and non-tumorigenic candidate for a future cellular therapy for diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Yu Zhou and David L. Mack performed the genetic modification of the cells and cowrote the manuscript, J. Koudy Williams, Sayed-Hadi Mirmalek-Sani and Jun Wang isolated and expanded the nonhuman primate amniotic fluid stem cells, Emily Moorefield, So-Young Chun and Diego Lorenzetti, performed gene expression analyses, Mark Furth and Shay Soker and Anthony Atala designed the experiments and assisted with data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Part of this study was supported by a research grant 5R01EB8009 from NIBIB.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Mark Pettenati from Medical Genetics and the Wake Forest School of Medicine for his assistance in the karyotype analysis of the AFS cells.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- T1D

Type 1 diabetes

- T2D

Type 2 diabetes

- AFS

amniotic fluid-derived stem cells

- NHP

non human primate

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative Reverse transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction

- ECM

extracellular matrix

References

- Adeghate E, Schattner P, Dunn E. An update on the etiology and epidemiology of diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1084:1–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrali SS, Sampley ML, Vanderford NL, Ozcan S. Glucose regulation of insulin gene expression in pancreatic beta-cells. Biochem J. 2008;415(1):1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ber I, Shternhall K, Perl S, Ohanuna Z, Goldberg I, Barshack I, Benvenisti-Zarum L, Meivar-Levy I, Ferber S. Functional, persistent, and extended liver to pancreas transdifferentiation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(34):31950–31957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303127200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman DM, Cabrera O, Kenyon NM, Miller J, Tam SH, Khandekar VS, Picha KM, Soderman AR, Jordan RE, Bugelski PJ, Horninger D, Lark M, Davis JE, Alejandro R, Berggren PO, Zimmerman M, O'Neil JJ, Ricordi C, Kenyon NS. Interference with tissue factor prolongs intrahepatic islet allograft survival in a nonhuman primate marginal mass model. Transplantation. 2007;84(3):308–315. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000275401.80187.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigam DL, Shapiro AJ. Pancreatic Transplantation: Beta Cell Replacement. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2004;7(5):329–341. doi: 10.1007/s11938-004-0046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowiak M, Maehr R, Chen S, Chen AE, Tang W, Fox JL, Schreiber SL, Melton DA. Small molecules efficiently direct endodermal differentiation of mouse and human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4(4):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwens L, Rooman I. Regulation of pancreatic beta-cell mass. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(4):1255–1270. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Yu C, Liu Y, Chen S, Guo Y, Yong J, Lu W, Ding M, Deng H. Generation of Homogeneous PDX1+ Pancreatic Progenitors from Human ES Cell-derived Endoderm Cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjp037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro G, Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, Tiozzo C, Lee J, Turcatel G, De Langhe SP, Driscoll B, Bellusci S, Minoo P, Atala A, De Filippo RE, Warburton D. Human amniotic fluid stem cells can integrate and differentiate into epithelial lung lineages. Stem Cells. 2008;26(11):2902–2911. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champeris Tsaniras S, J P. Generating pancreatic beta-cells from embryonic stem cells by manipulating signaling pathways. J Endocrinol. 2010;206(1):13–26. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Jones OW, Masui H. Human amniotic fluid cells grown in a hormone-supplemented medium: suitability for prenatal diagnosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79(15):4795–4799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Borowiak M, Fox JL, Maehr R, Osafune K, Davidow L, Lam K, Peng LF, Schreiber SL, Rubin LL, Melton D. A small molecule that directs differentiation of human ESCs into the pancreatic lineage. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(4):258–265. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou SH, C S, Chang YL, Chen YC, Li HY, Chen DT, Wang HH, Chang CM, Chen YJ, Ku HH. MafA promotes the reprogramming of placenta-derived multipotent stem cells into pancreatic islets-like and insulin-positive cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15(3):612–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YM, Lim JM, Yoo DH, Kim JH, Chung SS, Park SG, Kim TH, Oh SK, Choi YM, Moon SY, Park KS, Lee HK. Betacellulin and nicotinamide sustain PDX1 expression and induce pancreatic beta-cell differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour KA, Bang AG, Eliazer S, Kelly OG, Agulnick AD, Smart NG, Moorman MA, Kroon E, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE. Production of pancreatic hormone-expressing endocrine cells from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24(11):1392–1401. doi: 10.1038/nbt1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Alonso MD. Hypoglycemia as a barrier to glycemic control. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18(1):60–68. doi: 10.1016/S1056-8727(03)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo E, Baiguera S, Conconi MT, Vigolo S, Grandi C, Lora S, Martini C, Maffei P, Tamagno G, Vettor R, Sicolo N, Parnigotto PP. Pancreatic acellular matrix supports islet survival and function in a synthetic tubular device: in vitro and in vivo studies. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25(2):195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coppi P, Bartsch G, Siddiqui MM, Xu T, Santos CC, Perin L, Mostoslavsky G, Serre AC, Snyder EY, Yoo JJ, Furth ME, Soker S, Atala A. Isolation of amniotic stem cell lines with potential for therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):100–106. doi: 10.1038/nbt1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa T, Oh SH, Pi L, Hatch HM, Shupe T, Petersen BE. Teratoma formation leads to failure of treatment for type I diabetes using embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-producing cells. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(6):1781–1791. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage BK, Riedel MJ, Karanu F, Rezania A, Fujita Y, Webber TD, Baker RK, Wideman RD, Kieffer TJ. Cellular reprogramming of human amniotic fluid cells to express insulin. Differentiation. 2010;80(2-3):130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao F, Wu DQ, Hu YH, Jin GX. Extracellular matrix gel is necessary for in vitro cultivation of insulin producing cells from human umbilical cord blood derived mesenchymal stem cells. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121(9):811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomis R, Esmatjes E. Asymptomatic hypoglycaemia: identification and impact. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2004;20(2):S47–49. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D, Xu X, Pastori RL, Ricordi C, Kenyon NS. Elevation of cytotoxic lymphocyte gene expression is predictive of islet allograft rejection in nonhuman primates. Diabetes. 2002;51(3):562–566. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering BJ, Kandaswamy R, Ansite JD, Eckman PM, Nakano M, Sawada T, Matsumoto I, Ihm SH, Zhang HJ, Parkey J, Hunter DW, Sutherl DE. Single-donor, marginal-dose islet transplantation in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293(7):830–835. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou Y, Huang Q, Liu T, Guo L. Human amnion epithelial cells can be induced to differentiate into functional insulin-producing cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2008;40(9):830–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HP, Liu M, El-Hodiri HM, Chu K, Jamrich M, Tsai MJ. Regulation of the pancreatic islet-specific gene BETA2 (neuroD) by neurogenin 3. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(9):3292–3307. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.9.3292-3307.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, Tang YG, Zhu L, Khoury N, Hui Z, Wang KY, Perfetti R, Go VL. Glucagon like peptide-1-directed human embryonic stem cells differentiation into insulin-producing cells via hedgehog, cAMP, and PI3K pathways. Pancreas. 2010;39(3):315–322. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bc30dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichii H, Ricordi C. Current status of islet cell transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(2):101–112. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Au M, Lu K, Eshpeter A, Korbutt G, Fisk G, Majumdar AS. Generation of insulin-producing islet-like clusters from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2007a;25(8):1940–1953. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Shi Y, Zhao D, Chen S, Yong J, Zhang J, Qing T, Sun X, Zhang P, Ding M, Li D, Deng H. In vitro derivation of functional insulin-producing cells from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Res. 2007b;17(4):333–344. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaido T, Yebra M, Cirulli V, Rhodes C, Diaferia G, Montgomery AM. Impact of defined matrix interactions on insulin production by cultured human beta-cells: effect on insulin content, secretion, and gene transcription. Diabetes. 2006;55(10):2723–2729. doi: 10.2337/db06-0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneto H, Matsuoka TA, Katakami N, Matsuhisa M. Combination of MafA, PDX-1 and NeuroD is a useful tool to efficiently induce insulin-producing surrogate beta-cells. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(24):3144–3151. doi: 10.2174/092986709788802980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli O, Izhar-Prato Y, Bulvik S, Efrat S. Generation of insulin-producing cells from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by genetic manipulation. Stem Cells. 2007;25(11):2837–2844. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon NS, Chatzipetrou M, Masetti M, Ranuncoli A, Oliveira M, Wagner JL, Kirk AD, Harlan DM, Burkly LC, Ricordi C. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in rhesus monkeys treated with humanized anti-CD154. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999a;96(14):8132–8137. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon NS, Fernandez LA, Lehmann R, Masetti M, Ranuncoli A, Chatzipetrou M, Iaria G, Han D, Wagner JL, Ruiz P, Berho M, Inverardi L, Alejandro R, Mintz DH, Kirk AD, Harlan DM, Burkly LC, Ricordi C. Long-term survival and function of intrahepatic islet allografts in baboons treated with humanized anti-CD154. Diabetes. 1999b;48(7):1473–1481. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.7.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AJ, Fernandes JR, Hollister-Lock J, Nienaber CE, Bonner-Weir S, Weir GC. Normal relationship of beta- and non-beta-cells not needed for successful islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2007;56(9):2312–2318. doi: 10.2337/db07-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima H, Fujimiya M, Matsumura K, Younan P, Imaeda H, Maeda M, Chan L. NeuroD-betacellulin gene therapy induces islet neogenesis in the liver and reverses diabetes in mice. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):596–603. doi: 10.1038/nm867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Bang AG, Kelly OG, Eliazer S, Young H, Richardson M, Smart NG, Cunningham J, Agulnick AD, D'Amour KA, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(4):443–452. doi: 10.1038/nbt1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner RH, Zhang XY, Reiser J. Production, concentration and titration of pseudotyped HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(4):495–505. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leitao CB, Cure P, Tharavanij T, Baidal DA, Alejandro R. Current challenges in islet transplantation. Curr Diab Rep. 2008;8(4):324–331. doi: 10.1007/s11892-008-0057-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Deng ZL, Luo X, Tang N, Song WX, Chen J, Sharff KA, Luu HH, Haydon RC, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, He TC. A protocol for rapid generation of recombinant adenoviruses using the AdEasy system. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(5):1236–1247. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78(12):7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka TA, Kaneto H, Stein R, Miyatsuka T, Kawamori D, Henderson E, Kojima I, Matsuhisa M, Hori M, Yamasaki Y. MafA regulates expression of genes important to islet beta-cell function. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(11):2764–2774. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew CN, Wells JM. Converting human pluripotent stem cells into beta-cells: recent advances and future challenges. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(1):54–60. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283337e1c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melendez-Ramirez LY, Richards RJ, Cefalu WT. Complications of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(3):625–640. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo D, Pileggi A, Alejandro R, Ricordi C. Point: steady progress and current challenges in clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(8):1563–1569. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naya FJ, Stellrecht CM, Tsai MJ. Tissue-specific regulation of the insulin gene by a novel basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor. Genes Dev. 1995;9(8):1009–1019. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.8.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlsson H, Karlsson K, Edlund T. IPF1, a homeodomain-containing transactivator of the insulin gene. EMBO J. 1993;12(11):4251–4259. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06109.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olbrot M, Rud J, Moss LG, Sharma A. Identification of beta-cell-specific insulin gene transcription factor RIPE3b1 as mammalian MafA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(10):6737–6742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102168499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T, Beattie GM, Mally MI, Ricordi C, Hayek A. Nicotinamide is a potent inducer of endocrine differentiation in cultured human fetal pancreatic cells. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(3):1459–1466. doi: 10.1172/JCI116723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perin L, Sedrakyan S, Giuliani S, Da Sacco S, Carraro G, Shiri L, Lemley KV, Rosol M, Wu S, Atala A, Warburton D, De Filippo RE. Protective effect of human amniotic fluid stem cells in an immunodeficient mouse model of acute tubular necrosis. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9357. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poggioli R, Faradji RN, Ponte G, Betancourt A, Messinger S, Baidal DA, Froud T, Ricordi C, Alejandro R. Quality of life after islet transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(2):371–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikwar SP, Zavazava N. Insulin producing cells derived from embryonic stem cells: are we there yet? J Cell Physiol. 2009;218(2):256–263. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricordi C, Strom TB. Clinical islet transplantation: advances and immunological challenges. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(4):259–268. doi: 10.1038/nri1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EA, Bigam D, Shapiro AM. Current indications for pancreas or islet transplant. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2006;8(1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2004.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, Bigam D, Alfadhli E, Kneteman NM, Lakey JR, Shapiro AM. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54(7):2060–2069. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago JV. Lessons from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1993;42(11):1549–1554. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.11.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stendahl JC, Kaufman DB, Stupp SI. Extracellular matrix in pancreatic islets: relevance to scaffold design and transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.3727/096368909788237195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao BT, Taylor DG. Economics of type 1 diabetes. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2010;39(3):499–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateishi K, He J, Taranova O, Liang G, D'Alessio AC, Zhang Y. Generation of insulin-secreting islet-like clusters from human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(46):31601–31607. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner JD, Kavanagh K, Ward GM, Auerbach BJ, Harwood HJ, Jr, Kaplan JR. Old world nonhuman primate models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ilar J. 2006;47(3):259–271. doi: 10.1093/ilar.47.3.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei JP, Zhang TS, Kawa S, Aizawa T, Ota M, Akaike T, Kato K, Konishi I, Nikaido T. Human amnion-isolated cells normalize blood glucose in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Cell Transplant. 2003;12(5):545–552. doi: 10.3727/000000003108747000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetekam W, Groneberg J, Leineweber M, Wengenmayer F, Winnacker EL. The nucleotide sequence of cDNA coding for preproinsulin from the primate Macaca fascicularis. Gene. 1982;19(2):179–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90004-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LM, Wong SH, Yu N, Geras-Raaka E, Raaka BM, Gershengorn MC. Insulin but not glucagon gene is silenced in human pancreas-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27(11):2703–2711. doi: 10.1002/stem.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Jiang W, Liu M, Sui X, Yin X, Chen S, Shi Y, Deng H. Highly efficient differentiation of human ES cells and iPS cells into mature pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Cell Res. 2009a;19(4):429–438. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Wang WP, Guo T, Yang JC, Chen P, Ma KT, Guan YF, Zhou CY. The LIM-homeodomain protein ISL1 activates insulin gene promoter directly through synergy with BETA2. J Mol Biol. 2009b;392(3):566–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008;455(7213):627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]