Abstract

Background

Adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) are at increased cardiovascular risk. Studies of factors including treatment exposures that may modify risk of low cardiorespiratory fitness in this population have been limited.

Procedure

To assess cardiorespiratory fitness, maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) was measured in 115 ALL survivors (median age, 23.5 years; range 18–37). We compared VO2max measurements for ALL survivors to those estimated from submaximal testing in a frequency-matched (age, gender, race/ethnicity) 2003–2004 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) cohort. Multivariable linear regression models were constructed to evaluate the association between therapeutic exposures and outcomes of interest.

Results

Compared to NHANES participants, ALL survivors had a substantially lower VO2max (mean 30.7 vs 39.9 ml/kg/min; adjusted P<0.0001). For any given percent total body fat, ALL survivors had an 8.9 ml/kg/min lower VO2max than NHANES participants. For key treatment exposure groups (cranial radiotherapy [CRT], anthracycline chemotherapy, or neither), ALL survivors had substantially lower VO2max compared with NHANES participants (all comparisons, P<0.001). Almost two-thirds (66.7%) of ALL survivors were classified as low cardiorespiratory fitness compared with 26.3% of NHANES participants (adjusted P<0.0001). In multivariable models including only ALL survivors, treatment exposures were modestly associated with VO2max. Among females, CRT was associated with low VO2max (P=0.02), but anthracycline exposure was not (P=0.58). In contrast, among males, anthracycline exposure ≥100 mg/m2 was associated with low VO2max (P=0.03), but CRT was not (P=0.54).

Conclusion

Adult survivors of childhood ALL have substantially lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness compared with a similarly aged non-cancer population.

Keywords: childhood cancer, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, survivor, cardiorespiratory fitness

INTRODUCTION

Treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common childhood cancer, has improved markedly over the past three decades. Today, 85% of children with ALL will survive at least five years following diagnosis [1]. However, long-term survivors of childhood ALL have an increased risk of obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus, and consequently cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2–4].

Low cardiorespiratory fitness is one of the most important predictors of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, many chronic health risks, and functional limitations [5–11]. In a meta-analysis of 33 studies with 102,980 healthy adult men and women, Kodama et al reported that low cardiorespiratory fitness, estimated as maximal aerobic capacity and expressed in metabolic equivalent (MET) units, was associated with a 70% increased risk of all-cause mortality when compared with individuals with high cardiorespiratory fitness [11]. Importantly, cardiorespiratory fitness is modifiable and can be improved in most individuals with targeted interventions aimed at increasing levels of physical activity [5].

Studies have reported that children and adolescents have lower cardiorespiratory fitness levels following the completion of therapy for ALL compared with non-cancer groups [12,13]. Two recent studies, with small sample sizes, suggest that these changes may persist into young adulthood [14,15]. Assessments of factors, including treatment exposures, which may modify risk of low cardiorespiratory fitness have been limited. Recognizing these gaps, we conducted a study among 115 adult survivors of childhood ALL with the following aims: (1) assess cardiorespiratory fitness by measuring VO2max using a graded maximal exercise test, (2) compare measurements to a non-cancer population, and (3) evaluate the association between therapeutic exposures and cardiorespiratory fitness.

METHODS

Study Population: ALL Survivors

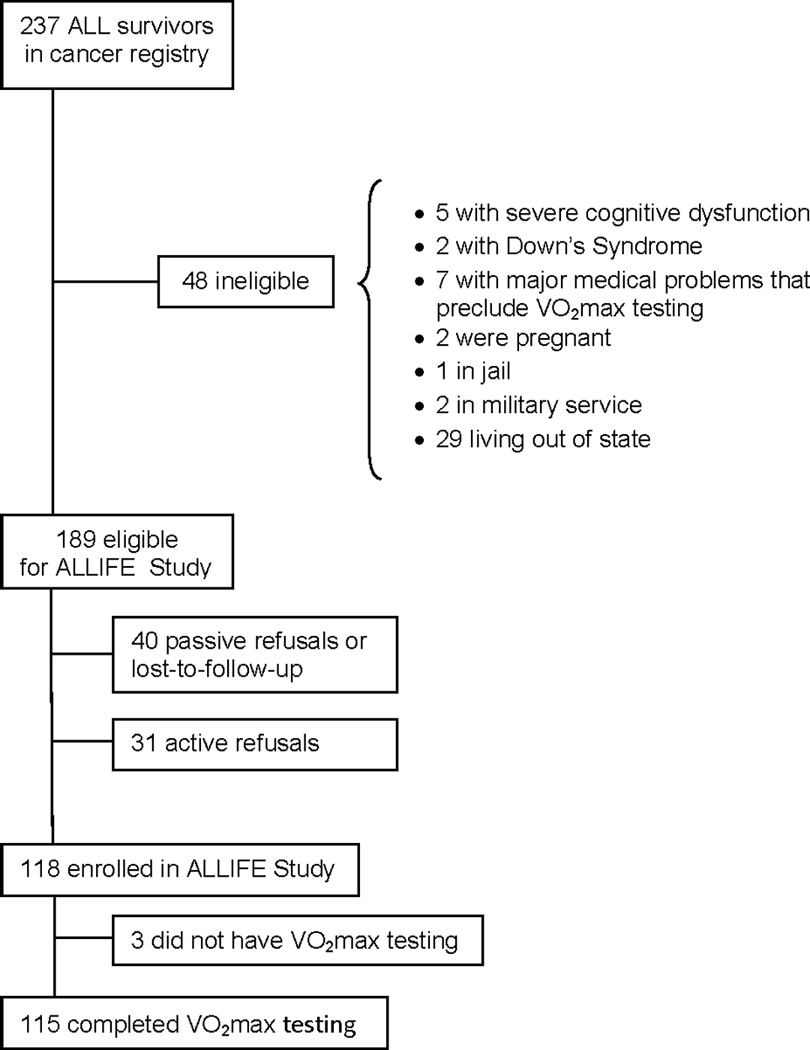

Between May 2004 and January 2007, a cohort of 118 adult survivors of childhood ALL enrolled in the ALLIFE Study, as described in prior reports (Figure 1) [3,16–19]. Eligible survivors diagnosed between 1970 and 2000, had no evidence of active disease, and were identified from the cancer registry (N=189). Detailed treatment records were available for ALL survivors. Non-participants (passive non-respondents, 21.2%; active refusals, 16.4%) were not significantly different than participants with respect to sex, race and ethnicity, age at study, age at ALL diagnosis, interval from diagnosis to study, or history of attending a long-term follow-up program (all P > 0.1). Of the 118 participants, 115 completed cardiorespiratory fitness testing. Prior to the study, the Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center approved the research protocol and all survivors provided written informed consent for participation and medical record abstraction.

Figure 1.

Patient flow diagram.

Comparison Population: NHANES Participants

The National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to monitor the health and nutritional status of the United States population [20]. The design for the NHANES is a stratified multistage probability of the civilian noninstitutionalized U.S. population. The survey consists of a household interview followed by a physical examination at a mobile examination center. Cardiorespiratory fitness testing was included in the physical examination for participants aged 12–49 years in the 2003–2004 NHANES. In 2003–2004 NHANES, 1208 participants completed cardiorespiratory testing. The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

To create a comparison group for the ALL survivors, we selected a frequency-matched sample of the NHANES participants who completed cardiorespiratory fitness testing and did not have a history of cancer, matching to the ALL survivors in a 5:1 ratio on gender, age (18–24; 25–38 years), and race (non-Hispanic white; minorities). This sampling scheme yielded 570 NHANES participants included in our analysis.

Cardiorespiratory Fitness Testing

ALL Survivors

Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed by maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) during a graded maximal exercise test on a treadmill. Measurements of inspired and expired air volumes and respiratory gas composition were made continuously using a CPX/D model metabolic measurement system (Medical Graphics Corporation, St. Paul, MN). Heart rate was measured with a heart rate monitor (Polar Electro, Finland) or a 12-lead ECG recording system for those participants who were treated with anthracyclines ≥300 mg/m2. Following a 5-minute warm-up, two submaximal measurements, and a recovery period, the treadmill grade was elevated by 2% every 2 minutes. Heart rate and rating of perceived exertion (RPE) were recorded during the last 30 seconds of each stage and at the end of the test. The test continued until either volitional fatigue occurred (participants indicated they were no longer able to continue) or standard stopping criteria consistent with maximal effort were met [21]. VO2max (L/min)

NHANES Participants

Cardiorespiratory fitness testing was performed by trained health technicians using a submaximal exercise test [20]. Based on gender, age, body mass index, and self-reported level of physical activity, participants were assigned to one of eight treadmill test protocols. The goal of each protocol was to elicit a heart rate that is approximately 75 percent of the age-predicted maximum (220-age) by the end of the test. Each protocol included a 2-minute warm-up, two 3-minute exercise stages, and a 2-minute cool down period. Heart rate was monitored continuously using an automated monitor and was recorded at the end of warm-up, each exercise stage, and each minute of recovery. At the end of warm-up and each exercise stage, participants were asked to rate their perceived exertion using the Borg scale. VO2max (ml/kg/min) was estimated by extrapolation to an expected age-specific maximal heart rate to the two 3-minute exercise stages [21,22].

Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) and body composition

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). In the ALLIFE Study, body composition was measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using a Lunar DPX scanner (MEC, Minster, OH). A Hologic QDR-4500A DXA scanner (Hologic, Inc., Bedford, Massachusetts) was used in the 2003–2004 NHANES.

Statistical analysis

To compare the ALL survivors to the NHANES participants, we estimated VO2max using treadmill speed and grade. For ALL survivors who were walking, we used the Givoni and Goldman method [23]; for those who were running, VO2max was estimated using the American College of Sports Medicine metabolic equations [21]. This combination of methods had the highest correlation with our gas-exchange measurements. Our findings were not different if we used only one or the other method. Low cardiorespiratory fitness was defined as an estimated VO2max below the 20th percentile of the same sex and age group from the NHANES 1999–2000 and 2001–2002 [24].

In the clinical setting, respiratory gases during maximal exercise testing are not collected and maximal aerobic capacity, expressed as METs, is estimated from treadmill speed and grade [6–11]. As such, we also estimated the maximal METS for ALL survivors using treadmill speed and grade and defined low maximal METs as <7.9 [11].

Multivariable linear regression and logistic regression models were used to compare continuous and binary outcomes between ALLIFE and NHANES participants while adjusting for matching factors and current smoking status. Since the NHANES cohort was frequency matched on gender, analyses included both females and males, unless otherwise stated. Because a proportion of the NHANES DXA is missing, the National Center for Health Statistics imputed values for the missing data and provides five imputed data files. We analyzed each data file separately and then combined estimates and standard errors using methods recommended for multiply imputed data [25].

In comparisons among only the ALL survivors, gas-exchange measurements were used. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for univariate analyses to examine differences in VO2max by gender, time since treatment, age at treatment, CRT treatment (yes/no), history of treatment with cyclophosphamide or doxorubicin, and dose of anthracyclines (categorized as no anthracyclines, 1–99 mg/m2, and ≥100 mg/m2). Importantly, nearly all subjects (111 of 115) had a history of treatment with vincristine, so subjects were not able to be compared based on this exposure. Multivariable linear regression models were used to determine whether CRT exposure (yes/no) and/or anthracycline dose (none, 1–99 mg/m2, ≥100 mg/m2) was associated with VO2max separately for males and females. Five of the ALL survivors (4.3%) in the cohort had been treated with total body irradiation (TBI) in preparation for an allogeneic bone marrow transplant. The VO2max was similar for these five survivors to the rest of the ALL cohort so they were not excluded from the analyses. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC), with a two-sided P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of ALL Survivors and NHANES Participants

Table I provides demographic and treatment-related characteristics of the ALL survivors and NHANES participants. The mean age ± standard deviation of the ALL survivors was 24.3±4.9 years (median, 23.5 years; range 18 to 37). Survivors were many years from cancer treatment; greater than two thirds were 15 or more years from therapy.

Table I.

Demographic characteristic of adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and frequency-matched NHANES participants

| Characteristic | ALL Survivors (N = 115) N (%) |

NHANES* (N = 570) N (%) |

p value** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at study, years | NA* | ||

| 18–24 | 73 (63.5) | 355 (62.3) | |

| 25–38 | 42 (36.5) | 215 (37.7) | |

| Gender | NA* | ||

| Female | 65 (56.5) | 321 (56.3) | |

| Male | 50 (43.5) | 249 (43.7) | |

| Race and ethnicity | NA* | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 87 (75.6) | 415 (72.8) | |

| Minority | 28 (24.4) | 155 (27.2) | |

| Education level | 0.0040 | ||

| HS graduate or less | 38 (32.7) | 271 (47.5) | |

| HS graduate + schooling | 77 (67.3) | 299 (52.5) | |

| Cigarette use | |||

| Current smoker | 10 (8.9) | 154 (27.0) | <0.0001 |

| Age at cancer diagnosis, years | |||

| 0–9 | 88 (76.5) | NA | |

| 10–17 | 27 (23.5) | NA | |

| Interval from cancer, years | |||

| 4–9 | 12 (10.4) | NA | |

| 10–14 | 28 (24.4) | NA | |

| ≥15 | 75 (65.2) | NA | |

| Cranial radiotherapy (CRT) | |||

| None | 76 (66.1) | NA | |

| 1–19 Gy | 10 (8.7) | NA | |

| ≥ 20 Gy | 29 (25.2) | NA | |

| Chemotherapy | |||

| Anthracycline, cumulative dose | |||

| None | 32 (27.8) | NA | |

| 1–99 mg/m2 | 44 (38.3) | NA | |

| 100–299 mg/m2 | 18 (15.6) | NA | |

| ≥ 300 mg/m2 | 21 (18.3) | NA | |

| Dexamethasone | 12 (10.4) | NA | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 47 (40.9) | NA |

frequency-matched for age at study, gender, and race/ethnicity;

p value adjusted for age, gender and race/ethnicity; NHANES, National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2003–2004); HS, high school; NA, not applicable

ALL Survivors vs NHANES Participants

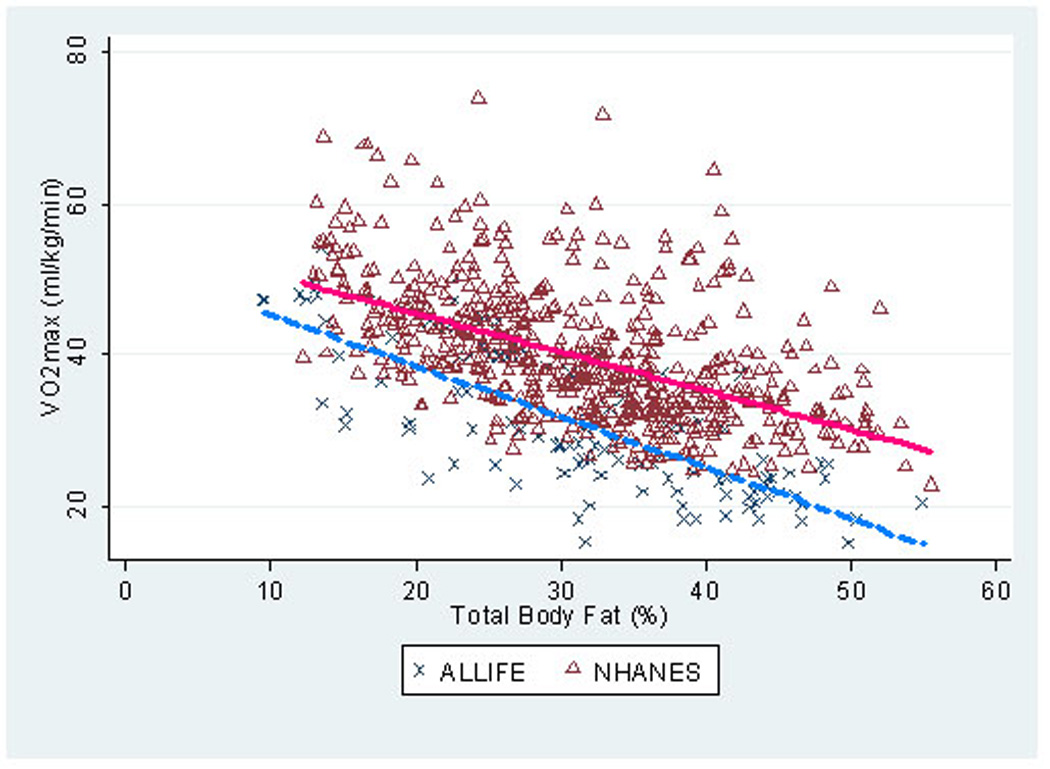

The mean estimated VO2max for the ALL survivors was 30.7 ml/kg/min (females, 25.8; males, 36.8) (Table II). For NHANES participants, the mean estimated VO2max was 39.9 ml/kg/min (females, 36.8; males, 44.0). The ALL survivors had a substantially lower VO2max than the NHANES participants, adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and smoking status (P<0.0001). Further adjusting by total body fat (percent) did not change this finding (P<0.0001). As demonstrated in Figure 2, for any given percent total body fat, ALL survivors had an 8.9 ml/kg/min lower VO2max than NHANES participants (adjusted for age, gender, race, and current smoking status). This finding was similar for both men and women (data not shown). Similarly, using lean mass (kg) rather than total mass did not change the relationship between VO2max and group (mean ml/kg lean mass/min; ALL survivors 45.3 vs NHANES 60.6; P<0.0001). Almost two-thirds of leukemia survivors were classified as low cardiorespiratory fitness (females, 79.7%; males, 50.0%) compared with 26.3% of NHANES participants (females, 28.0%; males, 24.1%).

Table II.

Anthropometrics and cardiorespiratory fitness in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and matched NHANES participants

| ALL Survivors | NHANES participants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (N=50) | Females (N=65) | Males (N=249) | Females (N=321) | overall p value† |

|||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Height, cm | 174.8 | 7.3 | 159.8 | 7.4 | 178.2 | 7.3 | 163.4 | 6.6 | <0.0001 |

| Weight, kg | 81.6 | 17.4 | 74.0 | 20.3 | 83.3 | 19.2 | 70.0 | 17.7 | 0.3020 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.8 | 5.6 | 28.9 | 7.8 | 26.2 | 5.5 | 26.2 | 6.6 | 0.0013 |

| Percent body fat, total | 23.8 | 8.4 | 38.0 | 7.7 | 24.4 | 6.8 | 36.5 | 7.0 | 0.3145 |

| Cardiorespiratory fitness | |||||||||

| VO2max ml/kg/min (gas-exchange) | 35.5 | 7.6 | 24.5 | 6.7 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| VO2max ml/kg/min (estimated*) | 36.9 | 9.0 | 25.8 | 6.5 | 43.9 | 7.8 | 36.8 | 7.8 | <0.0001 |

| VO2max ml/kg lean/min | 47.3 | 7.8 | 40.1 | 8.4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| VO2max ml/kg lean/min (estimated*) | 49.1 | 9.6 | 42.1 | 8.3 | 60.5 | 9.7 | 60.7 | 12.4 | <0.0001 |

| Low cardiorespiratory fitness (%) ** | 50.0 | 79.7 | 24.1 | 28.0 | <0.0001 | ||||

comparison between ALL survivors and NHANES participants reflects model adjusted for age at study, gender, race/ethnicity, and smoking status;

low cardiorespiratory fitness defined as an estimated VO2max below the 20th percentile of the same sex and age group from the NHANES 1999–2000 and 2001–2002; NHANES, National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2003–2004); NA, not applicable; SD, standard deviation

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of VO2max (ml/kg/min) by percent total body fat among 115 adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and 570 matched NHANES participants. * unadjusted analysis; NHANES, National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2003–2004)

We compared subgroups of ALL survivors to NHANES participants (Table III). Regardless of treatment exposure, age at treatment, or time from treatment, ALL survivors had substantially lower VO2max than NHANES participants (all subgroups, P<0.001). Even ALL survivors who did not receive any CRT or anthracycline chemotherapy (N=23) had a lower VO2max than the NHANES participants (mean ml/kg/min; ALL survivors 33.8 vs NHANES 39.9; P<0.001). Among those who were treated with CRT, the proportion with low cardiorespiratory fitness was 91.7% of the females and 85.7% of the males.

Table III.

Cardiorespiratory fitness in 115 adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia and matched NHANES participants

| VO2max ml/kg/minute |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | Mean | SD | p value* |

| NHANES | 570 | 39.9 | 8.6 | |

| ALL survivors, total group | 115 | 33.7 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| CRT, no | 76 | 32.7 | 9.9 | <0.001 |

| CRT, yes | 39 | 26.5 | 6.7 | <0.001 |

| Anthracyclines, none | 32 | 31.4 | 9.8 | <0.001 |

| Anthracyclines, 1–99 mg/m2 | 44 | 32.8 | 9.7 | <0.001 |

| Anthracyclines, ≥ 100 mg/m2 | 39 | 27.6 | 8.1 | <0.001 |

| No CRT or anthracycline chemotherapy | 23 | 33.8 | 10.4 | <0.001 |

p value is adjusted for age at study, gender, race/ethnicity, and current smoking status; NHANES, National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (2003–2004); CRT, cranial radiotherapy; SD, standard deviation

ALL Survivors Only

The mean VO2max was lower in survivors who were treated with CRT compared to those who were not (females: 23.5 vs 27.3, P=0.01; males: 31.6 vs 38.9, P<0.01). Among females, the mean VO2max was 26.4, 27.2, and 23.7 ml/kg/min for survivors treated with no anthracyclines, cumulative anthracycline dose of 1–99 mg/m2, and cumulative dose ≥100 mg/m2, respectively (P=0.18). Among the males, the mean VO2max was 42.6, 38.7, and 31.8 ml/kg/min for survivors treated with no anthracyclines, 1–99 mg/m2, and ≥100 mg/m2, respectively (P<0.01).

In multivariate models including race/ethnicity, duration since cancer diagnosis, CRT, and anthracycline chemotherapy, the association between therapeutic exposures and VO2max differed by sex (Table IV). Among females, CRT was associated with lower VO2max (P=0.02), but anthracycline exposure was not (anthracyclines ≥100 mg/m2; P=0.58). In contrast, among males, anthracycline exposure ≥100 mg/m2 was associated with lower VO2max (P=0.03), but CRT was not (P=0.54). Using different cut-points for anthracyclines (none, 1–299 mg/m2, ≥300 mg/m2) or analyzing as a continuous variable produced similar results for both males and females. There was not an interaction between CRT and anthracycline exposure (by total group or by gender). In a linear regression with VO2max as the outcome, inclusion of CRT and anthracycline exposure accounted for only a modest proportion of the variation in VO2max levels (unadjusted R2: females, 0.14; males, 0.23).

Table IV.

Associations between key therapeutic exposures and cardiorespiratory fitness among 115 adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females (N=65) | Males (N=50) | |||||

| Characteristic | β | 95% CI | p value | β | 95% CI | p value |

| CRT | ||||||

| No | -- | -- | ||||

| Yes | −4.3 | −7.8to−0.8 | 0.016 | −1.7 | −7.4 to 3.9 | 0.542 |

| Anthracyclines | ||||||

| None | -- | -- | ||||

| 1–99 mg/m2 | −1.4 | −5.3to 2.4 | 0.460 | −4.3 | −9.6 to 1.1 | 0.117 |

| ≥ 100 mg/m2 | −1.1 | −5.3to 3.0 | 0.579 | −7.4 | −13.9 to−1.0 | 0.025 |

p value calculated from multivariate regression model including race/ethnicity, time from diagnosis, CRT, and anthracycline dose category; CRT: cranial radiotherapy

Treatment with cyclophosphamide or dexamethasone was not significantly associated with VO2max. Age at diagnosis was not associated with VO2max. The findings presented in Table 4 were similar when ALL survivors who were current smokers (females, 3.1%; males, 15.4%) were excluded (data not shown).

The mean gas-exchange measured maximal aerobic capacity for the ALL survivors was 7.0±1.9 METs for females and 10.1±2.2 METs for males. The estimated METs based on treadmill speed and grade was 7.4±1.9 for females and 10.5±2.6 for males. Notably, 70.3% (45/64) of females and 14.0% (7/50) of males were classified as low maximal METs (<7.9 METs).

DISCUSSION

We report that adult survivors of childhood ALL, regardless of therapy, have substantially lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness than a frequency-matched population of non-cancer individuals. For perspective, the estimated maximal METs achieved by both female and male ALL survivors is similar to that of individuals aged 70 years [26]. Notably, for any given percent total body fat, ALL survivors had an 8.9 ml/kg/min lower VO2max than the non-cancer NHANES population. In other words, the substantially lower cardiorespiratory fitness levels do not appear to simply be the byproduct of the increased incidence of obesity observed in ALL survivors [13,19,27,28]. Similarly, VO2max was only modestly influenced by key therapeutic exposures, such as CRT, anthracycline chemotherapy, or time from treatment. Indeed, female ALL survivors with neither of these therapies achieved maximal METs comparable to that of a 70-year-old woman [26]. For the small number of male ALL survivors who were not treated with either CRT or anthracycline chemotherapy, cardiorespiratory fitness was less diminished, approaching that of 40–49 year olds [10,26].

The clinical implications of this study are important. It is well established that low cardiorespiratory fitness is one of the most important predictors among healthy men and women for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, numerous chronic health risks, and functional limitations [5,11]. It is not known whether the low VO2max levels in ALL survivors in our study, aged 18 to 37, have a similar risk of all-cause mortality reported by Kodama et al [11]. However, in their meta-analysis of 33 studies, including almost 103,000 individuals, the mean age at time of cardiorespiratory testing and follow-up duration ranged from 37 to 57 years and 1.1 to 26, years respectively. Notably, the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-mortality was not different for individuals under age 50 at time of testing compared to those 50 years and older. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the substantially reduced VO2max results in our ALL survivor population have serious implications for their future health. Fortunately, a relatively modest increase of 1 MET (i.e., walking 0.6 miles or 0.97 kilometers-per-hour faster on a treadmill) is associated with a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality [11]. Indeed, an increase of 1-MET is comparable to the risk reduction seen with a 7 cm decrease in waist circumference, a 5 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure, an 18.2 mg/dl (1.01 mmol/l) decrease in fasting plasma glucose, or a 7.7mg/dl (0.199 mmol/l) increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [11]. With targeted interventions, cardiorespiratory fitness can be improved [5]. Thus, further study and testing of interventions suitable for ALL survivors are warranted.

Our findings confirm and extend the work of two recent studies. Bar et al measured VO2max in 10 male adult survivors of childhood ALL with a median age of 24 years (range, 20–28) to 9 age-matched physically untrained and 12 age-matched trained healthy controls [14]. They reported that ALL survivors had a significantly lower VO2max (24.4 ml/kg/min) compared with trained (46.75 ml/kg/min, P<0.001) but not untrained controls (32.8 ml/kg/min). Jarvela et al compared 21 childhood ALL survivors, aged 16 to 30 years, to age- and sex-matched controls and reported that the VO2peak was 14% lower for survivors (34.8 ml/kg/min) compared to controls (40.5 ml/kg/min; P=0.01) [15]. Due to smaller sample size, neither study was able to assess the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and cancer treatment exposures.

In our study, we found a modest relationship between cumulative dose of anthracycline chemotherapy and reduced VO2max, adjusted for CRT, in males, but not females. Though anthracycline chemotherapy is associated, in a dose-dependent fashion, with left ventricular (LV) dysfunction [29–31], studies of children following ALL therapy have not reported a difference in VO2max based on anthracycline exposure [32–35]. Hauser et al reported that 10 of 38 ALL survivors who had a normal resting echocardiogram had significant LV dysfunction with stress echocardiography and that this stress-induced LV dysfunction correlated with VO2max [36]. However, these findings were not related to the cumulative dose of anthracycline. This should not be surprising, as VO2max does not correlate well with systolic dysfunction until an individual has overt heart failure [37,38]. We also found a modest relationship between CRT and reduced VO2max among women, but not men (adjusted for anthracycline exposure). Several studies have shown that female survivors of childhood ALL are more sensitive than males to adverse effects of CRT, including obesity [27,28,39], lower body weakness [40], physical inactivity [41], and insulin resistance [3,42]. Future studies of the underlying mechanisms of poor cardiorespiratory fitness among adult survivors of childhood ALL, particularly among women with a history of CRT, are needed.

While we found modest associations between reduced VO2max and these two treatment exposures, it should be noted that even survivors who did not receive either CRT or anthracycline chemotherapy had diminished cardiorespiratory fitness; again, this was most profound among women. A recent study by Ness and colleagues sheds some light on this issue. In a extensive evaluation of neuromuscular and physical function in 415 adult survivors of childhood ALL, they found that impairment was prevalent, more common among females, and associated with higher cumulative doses of vincristine and/or intrathecal methotrexate (and not CRT) [43]. These findings illustrate the multiple pathways by which ALL therapy, with or without CRT, may lead to physical inactivity and ultimately to reduced cardiorespiratory fitness.

When interpreting the findings from our study, it is important to draw attention not only to the strengths of the study (e.g., objectively measured cardiorespiratory fitness, relatively large cohort, detailed treatment exposures, comparison with a non-cancer population), but also to potential limitations. Caution should be applied when interpreting chronic condition estimates from studies including only survivors in a long-term follow-up program [44]. Our cohort was drawn from a cancer registry; the proportion of participants and non-participants followed in a long-term follow-up program was not significantly different (52.5% vs 47.2%; P=0.51). Furthermore, this study relied on a national sample for controls, frequency-matched by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Diet or other regional variations may contribute to cardiorespiratory fitness, but they would be likely to operate via measured covariates such as BMI or body fat. This study is, however, representative of a single locale and thus the findings warrant replication in other settings. Also, the NHANES method of estimating VO2max is based upon results from a submaximal test. However, the NHANES treadmill protocol has been validated and results are comparable to directly measured VO2max results [10,25]. Perhaps more importantly, the use of the NHANES data simply provides perspective – the VO2max levels reported in ALL survivors in our study are similar to those of (non-cancer) 70-year-olds and thus marginal differences in methodology are likely clinically irrelevant.

In summary, ALL survivors had very low levels of cardiorespiratory fitness. Unfortunately, cardiorespiratory fitness can be expected to continue to further decline with age unless actively intervened upon. Thus, ALL survivors should be encouraged to increase their level of physical activity. Further, developing and testing programs to encourage physical activity and improve cardiorespiratory fitness among long-term survivors of childhood ALL are warranted.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research grants from the National Institutes of Health (Oeffinger KC, PI: R01-CA-100474, K05-CA-160724), the Howard J. and Dorothy Adleta Foundation, the American Cancer Society Cancer Control Career Development Award (Tonorezos ES, PI: #121092), and the General Clinical Research Center (Grant M01-RR-00633 and CTSA UL1-RR-024982).

Footnotes

Contributors

KCO had full access to all data in the study and takes the responsibility of the integrity of the data. KCO, PGS, DAEK, ALD, and TSC contributed to the study design, DAEK contributed to data collection, CSM, JFC, KCO, PGS, TSC, EST, JEL, SMS, and AED contributed to data analysis and interpretation, EST, KCO, PGS, CSM, DAEK, JEL, JFC, SMS, ALD, and TSC contributed to writing and review of manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.SEER_2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeffinger KC. Are survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at increased risk of cardiovascular disease? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2 Suppl):462–467. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21410. discussion 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Adams-Huet B, Victor RG, et al. Insulin resistance and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in young adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3698–3704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–1582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.USDEPTHEALTH [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berry JD, Willis B, Gupta S, et al. Lifetime risks for cardiovascular disease mortality by cardiorespiratory fitness levels measured at ages 45, 55, and 65 years in men. The Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(15):1604–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farrell SW, Fitzgerald SJ, McAuley PA, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness, adiposity, and all-cause mortality in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(11):2006–2012. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181df12bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell JA, Bornstein DB, Sui X, et al. The impact of combined health factors on cardiovascular disease mortality. Am Heart J. 2010;160(1):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sui X, LaMonte MJ, Laditka JN, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and adiposity as mortality predictors in older adults. JAMA. 2007;298(21):2507–2516. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.21.2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang CY, Haskell WL, Farrell SW, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness levels among US adults 20–49 years of age: findings from the 1999–2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(4):426–435. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Brussel M, Takken T, Lucia A, et al. Is physical fitness decreased in survivors of childhood leukemia? A systematic review. Leukemia : official journal of the Leukemia Society of America, Leukemia Research Fund, UK. 2005;19(1):13–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warner JT. Body composition, exercise and energy expenditure in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(2 Suppl):456–461. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21411. discussion 468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bar G, Black PC, Gutjahr P, et al. Recovery kinetics of heart rate and oxygen uptake in long-term survivors of acute leukemia in childhood. European journal of pediatrics. 2007;166(11):1135–1142. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvela LS, Niinikoski H, Lahteenmaki PM, et al. Physical activity and fitness in adolescent and young adult long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. J Cancer Surviv. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janiszewski PM, Oeffinger KC, Church TS, et al. Abdominal Obesity, Liver Fat and Muscle Composition in Survivors of Childhood Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonorezos ES, Vega GL, Sklar CA, et al. Adipokines, body fatness, and insulin resistance among survivors of childhood leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(1):31–36. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malhotra J, Tonorezos ES, Rozenberg M, et al. Atherogenic low density lipoprotein phenotype in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of lipid research. 2012 doi: 10.1194/jlr.P029785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janiszewski PM, Oeffinger KC, Church TS, et al. Abdominal obesity, liver fat muscle composition in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3816–3821. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NHANES [Google Scholar]

- 21.American College of Sports Medicine. Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilmore JH, Haskell WL. Use of the heart rate-energy expenditure relationship in the individualized prescription of exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 1971;24(9):1186–1192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/24.9.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Givoni B, Goldman RF. Predicting metabolic energy cost. J Appl Physiol. 1971;30(3):429–433. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1971.30.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanders LF, Duncan GE. Population-based reference standards for cardiovascular fitness among US adults: NHANES 1999–2000 and 2001–2002. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(4):701–707. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000210193.49210.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHANESTECHDOC [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson AS, Sui X, Hebert JR, et al. Role of lifestyle and aging on the longitudinal change in cardiorespiratory fitness. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1781–1787. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garmey EG, Liu Q, Sklar CA, et al. Longitudinal changes in obesity and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(28):4639–4645. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Obesity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(7):1359–1365. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kremer LC, van Dalen EC, Offringa M, et al. Frequency and risk factors of anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(4):503–512. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, et al. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(12):808–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199103213241205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dalen EC, van den Brug M, Caron HN, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity: comparison of recommendations for monitoring cardiac function during therapy in paediatric oncology trials. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(18):3199–3205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Black P, Gutjahr P, Stopfkuchen H. Physical performance in long-term survivors of acute leukaemia in childhood. Eur J Pediatr. 1998;157(6):464–467. doi: 10.1007/s004310050854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jenney ME, Faragher EB, Jones PH, et al. Lung function and exercise capacity in survivors of childhood leukaemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1995;24(4):222–230. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950240403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Caro E, Fioredda F, Calevo MG, et al. Exercise capacity in apparently healthy survivors of cancer. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(1):47–51. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.071241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.TurnerGomes SO, Lands LC, Halton J, et al. Cardiorespiratory status after treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1996;26(3):160–165. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199603)26:3<160::AID-MPO3>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauser M, Gibson BS, Wilson N. Diagnosis of anthracycline-induced late cardiomyopathy by exercise-spiroergometry and stress-echocardiography. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(10):607–610. doi: 10.1007/s004310100830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gardin JM, Leifer ES, Fleg JL, et al. Relationship of Doppler-Echocardiographic left ventricular diastolic function to exercise performance in systolic heart failure: the HF-ACTION study. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4 Suppl):S45–S52. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arena R, MacCarter D, Olson TP, et al. Ventilatory expired gas at constant-rate low-intensity exercise predicts adverse events and is related to neurohormonal markers in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15(6):482–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross JA, Oeffinger KC, Davies SM, et al. Genetic variation in the leptin receptor gene and obesity in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(17):3558–3562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ness KK, Baker KS, Dengel DR, et al. Body composition, muscle strength deficits and mobility limitations in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(7):975–981. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Florin TA, Fryer GE, Miyoshi T, et al. Physical inactivity in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(7):1356–1363. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinberger J, Sinaiko AR, Kelly AS, et al. Cardiovascular risk and insulin resistance in childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ness KK, Hudson MM, Pui CH, et al. Neuromuscular impairments in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Associations with physical performance and chemotherapy doses. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ness KK, Leisenring W, Goodman P, et al. Assessment of selection bias in clinic-based populations of childhood cancer survivors: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(3):379–386. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]