Abstract

The resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs by cancer cells is considered to be one of the major obstacles for success in the treatment of cancer. A major mechanism underlying this multidrug resistance is the overexpression of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), resulting in an insufficient drug delivery to the tumor sites. A previous study has shown that stemofoline, an alkaloid isolated from Stemona burkillii could enhance the sensitivity of chemotherapeutics in a synergistic fashion. In the present study, we have focused on the effect of stemofoline on the modulation of P-gp function in a multidrug resistant human cervical carcinoma cell line (KB-V1). The effects of stemofoline on a radiolabeled drug, [3H]-vinblastine, and fluorescent P-gp substrates, rhodamine123, and, calcein-AM accumulation or retention were investigated to confirm this finding. Stemofoline could increase the accumulation or retention of radiolabeled drugs or fluorescent P-gp substrates in a dose-dependent manner. For additional studies on drug-P-gp binding, P-gp ATPase activity was stimulated by stemofoline in a concentration-dependent manner. More evidence was offered that stemofoline inhibits the effect on photoaffinity labeling of P-gp with the [125I]-iodoarylazidoprazosin in a concentration-dependent manner. These data indicate that stemofoline may interact directly with P-gp and inhibit P-gp activity, whereas stemofoline has no effect on P-gp expression. Taken together, the results exhibit that stemofoline possesses an effective MDR modulator, and may be used in combination with conventional chemotherapeutic drugs to reverse MDR in cancer cells.

Keywords: P-glycoprotein, stemofoline, multidrug resistance, Stemona burkillii, Stemonaceae, KB-V1

Introduction

The development of multidrug resistance (MDR) is a major impediment to the chemotherapeutic treatment of many forms of human cancer [1-4]. One major factor linked with the development of MDR in tumor cells is the overexpression of the 170 kDa plasma membrane phospho-glycoprotein, known as the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) or ABCB1, which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) superfamily [1-7]. Human P-gp is a 1280 amino acid protein encoded by the MDR1 gene. It is composed of two homologous halves, each containing six putative transmembrane helices and one nucleotide binding/utilization domain (NBD) also called ATP site. P-gp is an ATPase and utilizes the energy from ATP hydrolysis to reduce the accumulation of drugs or other toxins within cells by acting as a drug efflux pump [7]. In order to inhibit the drug export function of P-gp, a class of compounds known as modulators, or reversers can block its function. Modulators interact directly with P-gp, and appear to compete with drugs for the substrate-binding site(s) on the protein. Two of the best studied modulators are the calcium channel blocker verapamil, and the immunosuppressant cyclosporin A [4], and both of these agents are transported by P-gp. The binding of several P-gp substrates can be classified into four categories: (i) those that are bound to the Hoechst binding site (such as colchicine), (ii) those that are bound to the rhodamine binding site (such as daunorubicin), (iii) those that are bound to both sites (such as vinblastine), and (iv) those that appear to bind to neither site (such as progesterone) [8].

A major effort has been focused with the aim of developing effective resistance modulators to overcome the MDR in human forms of cancer. Many current studies are focused on the development of potent MDR modulators without any harmful side effects. Previously, three Stemona alkaloids were presented as MDR reversers [9]. These studies demonstrated that stemofoline, obtained from Stemona burkillii, is the most potent among them. The Stemona have long been used in China and other countries of Southeast Asia for their various medicinal and biological properties. In central Thailand, Stemona have been known to prevent the infestation of anchovy paste by housefly larvae. Traditional medical practitioners in Thailand have recommended Stemona as scabicide, pediculocide and antihelminthic worms, in spite of the fact that ingestion of too much could be potentially fatal [10]. In Thai folk medicines, Stemona is also used as an ingredient in anticancer and chronic anti-inflammation drug formulas. This study is an extended report, which can be used to show the possible inhibitory effect of stemofoline on P-gp-mediated efflux in drug resistant cancer cells. The data showed that stemofoline is able to inhibit the function of P-gp, but has no effect on P-gp expression in KB-V1 cells. These findings provide additional evidence for the development of stemofoline as a new potential chemosensitizers to improve effectiveness of anticancer drugs in the treatment of human cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

KB-3-1 cervical carcinoma drug sensitive cell line and its multidrug-resistant, P-gp overexpressing, sublines KB-V1 (maintained in 1 μg/mL vinblastine), were kindly supplied by Dr. Michael M. Gottesman (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD). KB-3-1 and KB-V1 cell lines were cultured in DMEM with 4.5 g of glucose/L plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 U/mL penicillin and 50 μg/mL streptomycin. These cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator with an atmosphere comprised of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. When the cells reached confluency, they were harvested and plated either for subsequent passages or for drug treatments.

Plant material

The roots of S. burkillii Prain were collected from Chiang Mai in 2008. The botanical identity of the sample was confirmed by Professor Harald Greger, a botanist at the Institute of Botany, University of Vienna. A voucher specimen has been deposited at the Chiang Mai University Herbarium, Department of Biology, Chiang Mai University. A corresponding collection of S. burkillii (HG 887) was also filed in the Herbarium of the Institute of Botany, University of Vienna, Austria (WU).

Extraction and isolation

Dried roots of Stemona burkillii were ground and extracted three times with 95 % ethanol over 3 days at room temperature. The ethanol extract was combined and evaporated by a rotary evaporator under reduced pressure. The extract was separated into two parts as ethyl acetate- and aqueous portions. Bioassay-guided isolation led to obtaining stemofoline (96.05 % purity by HPLC), an MDR reversing agent as previously described [9]. The corresponding chemical structure is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Structure of stemofoline

Drugs and chemicals

Silica gel 60 and silica gel 60 F254 TLC plates (alumina sheet) were purchased from Merck. The organic solvents used were of the analytical reagent grade and purchased from Merck. Vinblastine, verapamil (≥ 99.0% purity), cyclosporin A, (≥ 98.5% purity) rhodamine123 and sodium orthovanadate were purchased from Sigma. Calcein-AM was obtained from Molecular Probes Inc. [3H]-vinblastine (9.30 Ci/mmol) was obtained from Amersham Bioscience. [125I]-iodoarylazidoprazosin (IAAP, 2200 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) and trypsin were purchased from GibcoBRL. Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Sigma.

Radiolabeled drug retention

The effect of stemofoline on P-gp mediated drug transport was confirmed by monitoring the intracellular radiolabeled drug efflux. The method was modified from Plouzek et al. [11, 12]. KB-3-1 and KB-V1 cells (2.0×105 cells/well) were cultured in 6-well plates for 24 h. For determination of [3H]-vinblastine efflux [12], cells were incubated 60 min with 0.05 μCi [3H]-vinblastine/ml and 20 μM verapamil in order to load the cells with [3H]-vinblastine. Cells were then washed with ice-cold PBS at pH 7.4, followed by the drug-free medium containing stemofoline or verapamil (positive control). After incubation for 30 min, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS at pH 7.4 and harvested. The cells were then lysed with 200 μL of 1.5 N NaOH. Cell lysate was neutralized with 100 μL of 3N HCl and the radioactivity of [3H]-vinblastine was then determined with a liquid scintillation counter. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method [13] using 10 μL of cell lysate in 96-well plate. The intracellular [3H]-vinblastine was expressed as the amount of radioactivity (DMP) per mg protein of cells and then the [3H]-vinblastine retention was calculated in terms of the percentage relative to the vehicle control.

Fluorescent drug accumulation assay by FACS

Accumulation assays with KB-3-1 and KB-V1 (substrate used; rhodamine123, 1 μg/mL or calcein-AM, 0.5 μM) cells in the presence or absence of specific P-gp inhibitors (10 μM cyclosporin A, 20 μM verapamil) or stemofoline were performed as described below. The measurement of rhodamine123 or calcein-AM accumulations [12, 14, 15], KB-3-1 and KB-V1 cells (5.0×105 cells/sample) were incubated for 30 min with 1 μg/mL rhodamine123 or 15 min with 0.5 μM calcein-AM in the dark at 37°C in 5% CO2. Stemofoline (dissolved in DMSO) were added to cell cultures at the same time as rhodamine123, or calcein-AM. The final concentration of 0.4% DMSO (v/v) was used for all experiments and controls. Following rhodamine123, or calcein-AM accumulation, the cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS, then placed in HBSS with 10% FBS on wet ice and analyzed on FACScan flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson) equipped with a 488-nm argon laser. The green fluorescence of rhodamine123 and calcein were measured by a 530 nm band-pass filter (hLi). Samples were gated on forward scatter and side scatter to exclude debris and crumbs. A minimum of 10000 events were collected for each sample.

For the determination of rhodamine123 efflux, cells were loaded for 60 min with rhodamine 123 and 20 μM verapamil (a specific Pgp inhibitor), in order to load cells with rhodamine 123. The cells were then washed twice in ice-cold HBSS. The medium was then replaced with drug-free medium containing various concentrations of stemofoline or the reversing agent (20 μM verapamil or 10 μM cyclosporin A), or the vehicle (0.4% DMSO). Following efflux intervals of 30 min at 37 °C, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with ice-cold HBSS and rhodamine123 retained in the cell was measured by flow cytometry. As measured by trypan blue exclusion, the cells remained viable during the rhodamine123 accumulation and efflux studies with stemofoline and verapamil or cyclosporin A.

ATPase activity of P-gp assay

The ATPase activity in crude membranes of High-five insect cells expressing P-gp was measured by the endpoint, Pi release assay as described previously [2, 6, 15, 16]. This assay measures the amount of inorganic phosphate released for 20 min at 37 °C using a colorimetric method. Crude membranes (100 μg protein/mL) were incubated with increasing concentrations of stemofoline in the presence or absence of 0.3 mM sodium orthovanadate (Vi) in 100 μL of ATPase assay buffer (50 mM KCl, 5 mM sodium azide, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, and 1 mM ouabaine, pH 6.8). The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 mM ATP and terminated with SDS (2.5 % final concentration). P-gp specific activity was recorded as the vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity.

Photoaffinity labeling of P-gp with [125I]-IAAP

The crude membranes of P-gp expressing High-five insect cells (50-75 μg protein) were incubated with increasing concentrations of stemofoline (0-100 μM) at room temperature in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, for 10 min. 3-6 nM [125I]-IAAP (2200 Ci/mmole) was added and further incubated for additional 5 min under subdued light. The samples were then illuminated with a UV lamp (365 nm) assembly (PGC Scientifics) fitted with two black light (self-filtering) UV-long wavelength-F15T8BLB tubes for 10 min at room temperature (21-23 °C). Following SDS-PAGE on a 7% Tris-acetate gel at constant voltage (150 V), gels were dried and exposed to Bio-Max MR film at −80 °C for 5-18 hr. The radioactivity incorporated into the P-gp band was quantified as described [6] using a STORM 860 PhosphorImager system (Molecular Dynamics) and the software ImageQuant TL (GE Healthcare).

Western blot analysis of P-gp expression

Whole cell lysates were prepared by way of harvesting the treated cells and then rinsing them twice with PBS. Treated cells were incubated in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM PMSF, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5 μg/mL each of aprotinin and leupeptin) for 20 min with occasional rocking followed by being centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The protein amount was measured by the method of Bradford protein assay [13] using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard. The plasma membrane proteins (20 μg/lane) were separated on 8 % SDS-polyacrylamide gel and immunoblotted overnight onto nitrocellulose filters (Amersham Hybond ECL). The filters were incubated sequentially with mouse monoclonal anti-Pgp clone C219 (Calbiochem) at dilution of 1:10000 and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG at a dilution of 1:5000.

Statistical analysis

The results were presented as means ± SE from duplicate or triplicate samples of three independent experiments (n = 3). Differences between the means were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was considered at p<0.05.

Results

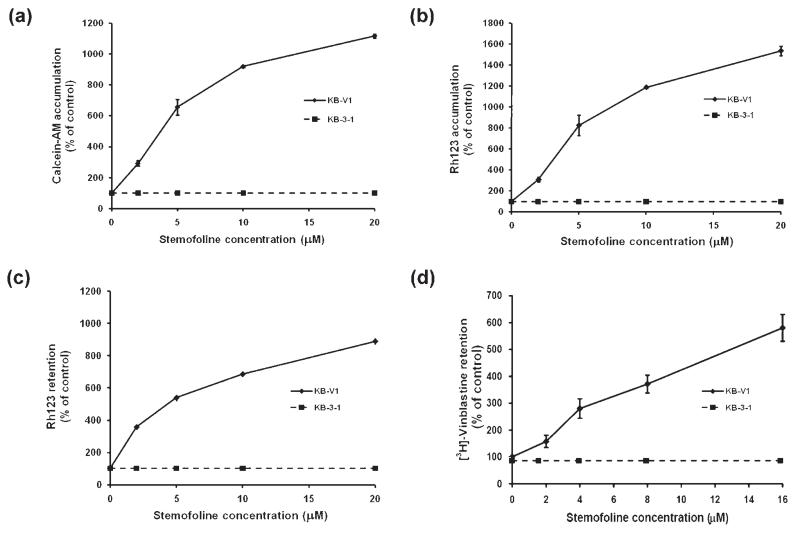

We studied the effect of stemofoline on P-gp function. Accumulation of fluorescent substrates of P-gp (calcein-AM and Rh123) was determined using flow cytometry. The result demonstrated that stemofoline increased the accumulation of calcein-AM in KB-V1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (ED50 at 4.6 ± 0.2 μM; Fig 2a). At the lowest concentration of stemofoline used, 2 μM, calcein-AM accumulation was significantly increased 3-fold compared to 11-fold at 20 μM. At this higher concentration of stemofoline, calcein-AM accumulation was similar to that measured in the presence of 20 μM verapamil (13-fold) or 10 μM cyclosporin A (12-fold), a well-known and potent P-gp inhibitor. The same treatment of stemofoline showed that the accumulation of Rh123 in KB-V1 cells was also significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (ED50 at 5.1 ± 1.1 μM; Fig. 2b). The presence of stemofoline at 2 to 20 μM increased the Rh123 accumulation in KB-V1 cells by 4- to 16-fold. In comparison, verapamil at 20 μM and cyclosporin A at 10 μM enhanced Rh123 accumulation by 23- and 16-fold, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Effect of stemofoline on (a) calcein-AM accumulation (b) Rh123 accumulation (c) Rh123 retention and (d) [3H]-vinblastine retention in KB-V1 cells. The amount of intracellular calcein-AM and Rh123 in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of stemofoline were determined using a flow cytometer, whereas the amount of intracellular radioactivity in the absence or presence of indicated concentrations of stemofoline were determined by β-counter. The mean value from three independent experiments is shown, and error bars indicate SE (n = 3).

To confirm the P-gp function inhibitory effect of stemofoline, the fluorescence Rh123 and radiolabeled drug; [3H]-vinblastine efflux, were performed in drug-resistant KB-V1 cells, and compared with their retention in the drug-sensitive KB-3-1 cells. The results demonstrated that stemofoline increased the retention of Rh123 in KB-V1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (ED50 at 5.2 ± 0.2 μM; Fig. 2c). The presence of stemofoline at 2 to 20 μM increased the Rh123 retention in KB-V1 cells by 3.5- to 9-fold, respectively (Fig. 2c). In comparison, verapamil at 20 μM and cyclosporin A at 10 μM enhanced Rh123 retention by 8- and 8.5-fold, respectively. The same treatment of stemofoline showed that the radioactive drug efflux was also significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (approximately ED50 at 5 μM; Fig. 2d). The presence of stemofoline at 8 and 16 μM increased the intracellular radiolabeled drug [3H]-vinblastine retention in KB-V1 cells by 4- and 6-fold, respectively (Fig. 2d). In comparison, verapamil at 20 μM enhanced vinblastine retention by 3-fold, demonstrating that stemofoline at 8 and 16 μM increased drug retention compatibility with 20 μM verapamil. The accumulation and retention of fluorescence substrates and the radiolabeled drug in wild-type KB-3-1 cells treated with stemofoline and a positive control, verapamil or cyclosporin A, did not differ from the accumulation and retention in cells without any treatment (shown as a dashed line in Fig. 2).

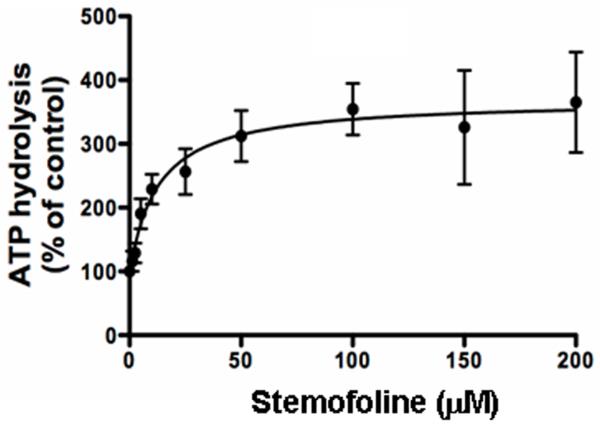

The effect of stemofoline on ATP hydrolysis by P-gp was determined in crude membranes isolated from High-five cells overexpressing P-gp. As shown in Fig. 3, 50 μM stemofoline showed 3.7-fold stimulation of ATP hydrolysis (70.9 ± 8.0 nmoles Pi/mg protein/min) compared with basal activity (19.0 ± 3.2 nmoles Pi/mg protein/min). The concentration required for 50% stimulation was 12.6 ± 6.1 μM (n =3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of stemofoline on ATPase activity of P-gp. The vanadate-sensitive ATPase activity of P-gp was determined using the Pi release assay as described under Materials and Methods in the presence of increasing concentrations of stemofoline (0-200 μM). The Y-axis shows the ATP hydrolysis (% of control), and the X-axis shows varying concentrations of stemofoline. The mean value from three independent experiments is shown, and error bars indicate SE (n = 3).

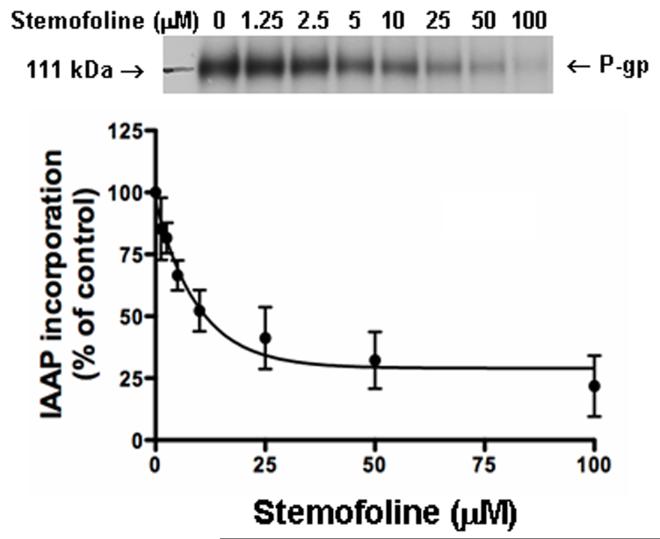

To assess whether stemofoline interacts directly with the substrate-binding site(s) of P-gp, the effect of stemofoline on the photoaffinity labeling of P-gp with IAAP was monitored. IAAP is an analog of prazosin, which is transported by P-gp [17]. The data in Fig. 4 demonstrate that stemofoline effectively inhibits photoaffinity labeling of P-gp with IAAP in a concentration-dependent manner. The IC50 value of stemofoline for inhibition of IAAP binding was 6.7 ± 0.8 μM (n = 3).

Fig. 4.

Effect of stemofoline on photoaffinity labeling of P-gp with IAAP. The photolabeling of P-gp with [125I]-IAAP was monitored as described in Materials and Methods in the presence of increasing concentrations of stemofoline (0-100 μM). The Y-axis shows the percent of [125I]-IAAP incorporation and the X-axis shows varying concentrations of stemofoline. The data were fitted by non-linear least square regression analysis using the software GraphPad Prism 2.0. The mean value from three independent experiments is shown, and error bars indicate SE. The autoradiogram shows incorporation of IAAP into the P-gp band in the presence of indicated concentrations of stemofoline.

Taken together, the IC50 values for the inhibition of both IAAP binding and the stimulation of vanadate-stimulated ATPase activity suggest that stemofoline most likely exerts its inhibitory effect by binding to the substrate-binding sites on the transporter.

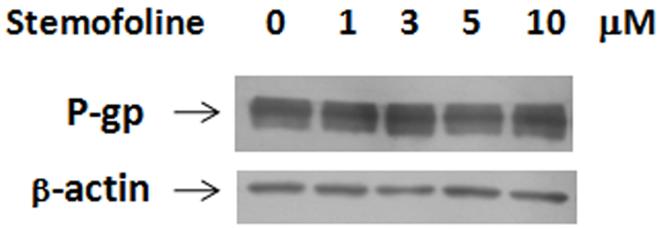

Overexpression of P-gp has been well established as the cause of the MDR phenotype in vitro selected drug-resistant cell lines. KB-V1 cells have been shown to express P-gp at a high level on their plasma membrane. To assess whether stemofoline could modulate P-gp expression, Western blot analysis was carried out. KB-V1 cells were treated for 72 h by stemofoline at the concentration of 1, 3, 5, 10 μM, no significant change of P-gp expression was observed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of stemofoline on the P-gp protein level in KB-V1 cells. P-gp expression in KB-V1 cells treated for 72 h by stemofoline at the concentration of 1, 3, 5, 10 μM was determined by Western blotting.

Discussion

For the purpose of overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer cells, the development of agents, which inhibit the P-gp-mediated efflux of cytotoxic drugs, and reverse MDR have been intensively pursued. First-generation MDR modulators (eg. verapamil, cyclosporin A) had other pharmacological activities and were not specifically developed for inhibiting MDR.Verapamil, a calcium channel blocker, and cyclosporin A, an immunosuppressive agent, are the most effective P-gp inhibitors in vitro, but they have limited clinical use. Their affinity was low for ABC transporters and necessitated the use of high doses, resulting in unacceptable side effects at doses required for their application. These limitations prompted the development of new chemosensitizers with higher selectivity and potency, and less toxicity [18].

Stemona is a Thai traditional medicine in cancer treatment but its effect at the cellular level is still unknown. We reported previously that Stemona alkaloids, stemofoline, stemocurtisine and oxystemokerrine, could enhanced the cytotoxicity of the KB-V1 cells as anticancer drugs, but they did not show cytotoxicity on KB cell lines and fibroblast (human normal cells) themselves. Stemofoline showed an interestingly significant potency on MDR phenotype test of KB-V1 at the concentration of 1-5 μM. Stemofoline could reduced the IC50 of vinblastine to KB-V1 more than 4-fold at the concentration of 5 μM [9]. Comparing the potency of stemofoline to another P-gp modulators from natural sources, for example; quercetin and kaempferol, showed the reversal property on KB-V1 at concentrations 10-30 μM could decrease the IC50 of vinblastine about 1.1- to 1.3-fold and 1.2- to 1.76-fold, respectively [19]. Curcumin, the most effective curcuminoid MDR modulators from turmeric, could reduced the IC50 of vinblastine about 5.6-fold at the concentration of 15 μM [20]. This information supported the fact that stemofoline possesses a higher potency compared to another well-known natural compound. This leads us to investigate the biochemical mechanism of stemofoline on P-gp function and expression.

In P-gp functional studies, stemofoline dose dependently increased intracellular accumulation, and reduced the efflux of [3H]-vinblastine, Rh123 and calcein-AM in MDR KB-V1 cells, but not the wild-type drug-sensitive KB-3-1 cells. Verapamil and cyclosporin A are well-known P-gp chemosensitizers and were used as reference compounds in our study. Overall, our data demonstrated that stemofoline at 2 to 20 μM inhibited P-gp function compatibility with 20 μM verapamil and 10 μM cyclosporin A. In comparison to other natural products, Rh123 accumulation was increased in the multidrug-resistant cell lines incubated with resveratrol (a polyphenol from red wine) at 100 μM, EGCG (a catechin from green tea) at 50 μM and curcumin (a polyphenol from turmeric) at 30 μM by 1.4-, 3.7- and 3-fold, respectively [12, 21]. Our studies showed that the presence of stemofoline at 2 to 20 μM increased the Rh123 accumulation in KB-V1 cells by 4- to 16-fold (ED50 at 5.1 ± 1.1 μM).

The direct interaction of stemofoline with P-gp was assessed by ATPase and photoaffinity labeling assays. Stemofoline simulated several folds of the ATPase activity of P-gp. The incorporation of IAAP into P-gp was significantly inhibited by stemofoline in a concentration-dependent manner. Thus, it can be suggested that stemofoline exhibited the inhibitory effect on the P-gp drug transporter by interacting directly with the transport molecule, probably at the same binding site as prazosin.

Since the period of time of exposure of the cells to stemofoline in P-gp functional assay was short (1 h), it is unlikely that stemofoline acted by downregulating MDR1 transcription, which would have reduced the amount of cellular P-gp. On the other hand, the protein levels of P-gp were determined and the results showed that the P-gp expression in KB-V1 cells was not affected after incubation in the presence of 1-10 μM of stemofoline for up to 72 h. These data indicate that stemofoline might reverse the MDR phenotype by blocking P-gp function, but not by reducing P-gp expression.

In summary, stemofoline showed reversal effects on the MDR phenotype which is consistent with increased intracellular accumulation of the drugs. The results reported here open the possibility for investigations on the effect of stemofoline in animal experiments to determine if stemofoline has potential as a non-toxic effective chemosensitizer to be used in combination with conventional chemotherapy.

Acknowledgments

This work has been financially supported by the National Research Council of Thailand. S.O. and S.V.A were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. We thank Dr. Michael M. Gottesman (National Cancer Institute, NIH) for the donation of the KB-3-1 and KB-V1 cell lines.

Abbreviations

- Rh123

rhodamine123

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

All the authors report no conflict of interest and accept full responsibility of the article’s content.

References

- 1.Ramachandra M, Ambudkar SV, Chen D, Hrycyna CA, Dey S, Gottesman MM, Pastan I. Human P-glycoprotein exhibits reduced affinity for substrates during a catalytic transition state. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5010–5019. doi: 10.1021/bi973045u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharom FJ. The P-glycoprotein efflux pump: How does it transport drugs? J Membrane Biol. 1997;160:161–175. doi: 10.1007/s002329900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosch I, Croop J. P-glycoprotein multidrug resistance and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F37–F54. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharom FJ, Liu R, Romsicki Y, Lu P. Insights into the structure and substrate interactions of the P-glycoprotein multidrug transport from spectroscopic studies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1461:327–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambudkar SV, Kim I, Sauna ZE. The power of the pump: mechanisms of action of P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) Eur J Pharm Sci. 2006;27:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sauna ZE, Ambudkar SV. Characterization of the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis by human P-glycoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11653–11661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011294200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hrycyna CA, Ramachandra M, Germann UA, Cheng PW, Pastan I, Gottesman MM. Both ATP sites of human P-glycoprotein are essential but not symmetric. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13887–13899. doi: 10.1021/bi991115m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litman T, Druley TE, Stein WD, Bates SE. From MDR to MXR: new understanding of multidrug resistance system, their properties and clinical significance. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:931–959. doi: 10.1007/PL00000912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanmahasathien W, Ampasavate C, Greger H, Limtrakul P. Stemona alkaloids, from traditional Thai medicine, increase chemosensitivity via P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance. Phytomedicine. 2011;18:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greger H. Structure relationships, distribution and biological activities of Stemona alkaloids. Planta Med. 2006;72:99–113. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-916258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Plouzek CA, Ciolino HP, Clarke R, Yeh GC. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein activity and reversal of multidrug resistance in vitro by rosemary extract. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1541–1545. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00180-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jodoin J, Demeule M, Beliveau R. Inhibition of the multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein activity by green tea polyphenols. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1542:149–159. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauna ZE, Muller M, Peng X, Ambudkar SV. Importance of the conserved Walker B glutamate residues, 556 and 1201, for the completion of the catalytic cycle of ATP hydrolysis by human P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) Biochemistry. 2002;41:13989–14000. doi: 10.1021/bi026626e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla S, Robey RW, Bates SE, Ambudkar SV. Sunitinib (Sutent, SU11248), a small-molecule receptor tyrosone kinase inhibitor, blocks function of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and ABCG2. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:359–365. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.024612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ambudkar SV. Drug stimulatable ATPase activity in crude membranes of human MDR1 transfected mammalian cells. Methods Enzymol. 1998;292:504–514. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)92039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maki N, Hafkemeyer P, Dey S. Allosteric modulation of human P-gp. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18132–18139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozben T. Mechanisms and strategies to overcome multiple drug resistance in cancer. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2903–2909. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Limtrakul P, Khantamat O, Pintha K. Inhibition of P-glycoprotein function and expression by kaempferol and quercetin. J Chemotherapy. 2005;17:86–95. doi: 10.1179/joc.2005.17.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chearwae W, Anuchapreeda S, Nandigama K, Ambudkar SV, Limtrakul P. Biochemical mechanism of modulation of human P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) by curcumin I, II, and III purified from Turmeric powder. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2004;68:2043–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anuchapreeda S, Ambudkar SV, Leechanachai P, Limtrakul P. Modulation of P-glycoprotein expression and function by curcumin in multidrug resistant human KB Cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;64:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]