Abstract

Introduction

Perinatal suicidality, i.e., thoughts of death, suicide attempts, or self-harm during the period immediately before and up to 12 months after the birth of a child, is a significant public health concern. Few investigations have examined the patients’ own views and experiences of maternal suicidal ideation.

Methods

Between April and October 2010, we identified 14 patient participants at a single university-based medical center for a follow-up, semi-structured interview if they screened positive for suicidal ideation on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) short-form. In-depth interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide. We transcribed all interviews verbatim and analyzed transcripts using thematic network analysis.

Results

Participants described the experience of suicidality during pregnancy as related to somatic symptoms, past diagnoses, infanticide, family psychiatric history (e.g., completed suicides and family member attempts), and pregnancy complications. The network of themes included the perinatal experience, patient descriptions of changes in mood symptoms, illustrations of situational coping, and reported mental health service use.

Implications

The interview themes suggested that in this small sample, pregnancy represented a critical time period to screen for suicide and to establish treatment for the mothers in our study. These findings may assist health care professionals in the development of interventions designed to identify, assess, and prevent suicidality among perinatal women.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, pregnancy, suicidality, psychosocial screening, maternal mental health

Background

Suicidality during the perinatal period is a serious public health concern, because suicide is among the leading causes of maternal mortality (Chang, Berg, Saltzman, & Herndon, 2005; Palladino, Singh, Campbell, Flynn, & Gold, 2011). Suicidal ideation or suicidal thoughts, are often associated with suicide attempts and completions. Rates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy range from 13.1% to 46%. However, these estimates have been based on small psychiatric or drug-dependent treatment high-risk samples (Birndorf, Madden, Portera, & Leon, 2001; M. Copersino, Jones, Tuten, & Svikis, 2008; M. L. Copersino, Jones, Tuten, & Svikis, 2005; Newport, Levey, Pennell, Ragan, & Stowe, 2007). In a recent U.S. study of a community-based sample of pregnant women, the 14-day prevalence of antenatal suicidal ideation was 2.7% (Gavin, et al., 2011), which was similar to the 12-month prevalence of suicidal ideation among the general population (Kessler, Berglund, Borges, Nock, & Wang, 2005). The comparable rates of suicidal ideation contradicts the notion that suicide is lower during pregnancy (Appleby, 1991). Risks factors for suicidal ideation during the antenatal period include depression, perceived stress, smoking and common mental disorders (Gavin, et al., 2011; Huang H et al., 2012). Because few studies have examined the maternal experiences and beliefs associated with perinatal suicidal ideation, research is needed to identify beliefs and experiences related to perinatal suicidal ideation to assist health professionals in screening and treating perinatal women. Accordingly, the objectives of the present study were to: (1) use qualitative methods to identify salient themes among a non-treatment sample of perinatal women regarding beliefs about suicidal ideation; and (2) to describe experiences with care-seeking for perinatal suicidal ideation and the role that clinical comorbidities played in these beliefs and expereinces.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this study was taken from a longitudinal study of women who received prenatal care at a single university-based delivery hospital. Participants enrolled in the longitudinal perinatal database registry study on psychosocial mood disorders during pregnancy who were ≥18 years of age and older were eligible for the present study. In contrast to prior studies that have examined suicidality in high-risk populations or women recruited from treatment programs for depression (Bowen, Stewart, Baetz, & Muhajarine, 2009; Chung-Hey, Shing-Yaw, Ue-Lin, Ying-Fen, & Fan-Hao, 2006), participants in the present sample were recruited from a hospital-based, prenatal, non-hospitalized sample of a maternal care clinic whose patients were racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse, with slightly more than 50% of clinic patients using publically funded health insurance (Bentley, Melville, Berry, & Katon, 2007). This population also varied in their medical risks and chronic conditions.

During the 6-month study period, 424 patient participants were screened at least once for perinatal mood disorders. Of these, 416 patient participants consented to have study staff collect and enter their questionnaire responses and medical records data into the clinic database registry. Among these 416 respondents, 16 screened positive for suicidal ideation, and 14 of these agreed to participate in the follow-up interview study. Data collection ended after the recruitment of those 14 participants.

Procedures

In the present study, all study participants consented to participate in the longitudinal study. Once consented, all study participants received at least one questionnaire as part of routine antenatal care distributed by clinic staff. All study participants received the questionnaire in the second or third trimester or during the 6-week postpartum visit. The questionnaire was developed using diagnostic criteria to assess probable depression, panic disorder, suicidal ideation, and various factors associated with predicting depression. The longitudinal study protocol has been described in detail elsewhere (Bentley, et al., 2007; Melville, Gavin, Guo, Fan, & Katon, 2010). The results of the questionnaire were reviewed on the day of the screening by clinic staff and reported to providers if questionnaires were positive for depression and/or suicidal ideation. Any patient who screened positive for suicidal ideation was triaged and evaluated for safety by a perinatal social worker. Because a single item captures both active and passive wishes to die, along with self-harm, we conducted follow-up, in-depth interviews with patient participants to capture their experiences and beliefs regarding suicidal ideation during pregnancy and the postpartum.

In the present study, from April 2010 through October 2010, all women ≥ 18 years of age who screened positive for suicidal ideation and enrolled in the longitudinal study were approached to participate in the present qualitative study. Perinatal social workers evaluated patients’ suicidal risk prior to enrollment in the present study. Invitation letters were distributed to eligible women at perinatal visits by clinic staff. In four instances, invitation letters were mailed to the home of eligible women. Written consent was obtained for all study participants. Interviews were conducted in private clinic examination rooms unless the participant specifically requested to meet outside the clinic. In these rare instances, interviewers travelled to alternative locations, which were assessed for privacy at the time of the interview. Interviews averaged 29 minutes and ranged from 15 to 90 minutes. Respondents were compensated $30 for their participation. Participants were interviewed by trained interviewers, and all interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Both study protocols received approval from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Probable major (minor) depression and suicidal ideation were evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) short form. In a study of 3,000 obstetric and gynecology patients, the PHQ-9 demonstrated high sensitivity (73%) and specificity (98%) for a diagnosis of major depression based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (Spitzer, Williams, Kroenke, Hornyak, & McMurray, 2000). Depressive disorders were reported as “probable major (and minor) depression.” The criteria for minor depression require the participant to have two to four depressive symptoms present for more than half the days, for at least 2 weeks, with at least one of these symptoms being depressed mood or anhedonia. Suicidal ideation was assessed from Item 9 of the PHQ-9, which reads “Over the last two weeks, how often have you been bothered by--- thoughts that you would be better off dead or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way?” Response options measure severity and include: 0=“not at all”, 1= “several days”, 2= “more than half the days”, and 3= “nearly every day” (Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999). A score greater than 1, rendered a positive screen for suicidal ideation. The questionnaire also inquired about psychosocial stress (Curry, Burton, & Fields, 1998; Curry, Campbell, & Christian, 1994), substance use (Midanik, Zahnd, & Klein, 1998), and domestic violence (McFarlane & Parker, 1992).

Because a single item captures both active and passive wishes to die, along with self-harm, we conducted follow-up, in-depth interviews with respondents to capture their experiences and beliefs regarding perinatal suicidal ideation. The interview guide was developed using semi-structured questions to learn about respondents’ perceived control of their thoughts, associated behaviors, past suicidiality, treatment usage, and perceptions regarding support (see Box 1). When the participant introduced a new topic thread, the interviewer followed that thread. This technique allowed the participants an unrestricted opportunity to describe their experiences as well as describe how suicidal ideation (and/or comorbidity of depression) affected their lives and relationships.

Box 1. Semi-structured Interview Guide: “Experiences with suicide ideation interview guide”.

“You indicated (today) (or) (on the survey you completed for us in MONTH) that sometimes you think that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way.”

<Assess onset of symptoms>

I would like you to think back to the first time that you thought you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way. Can you tell me what that was like for you?

How old were you?

Can you remember what was going on in your life at that time?

How would you describe your mood (in your own words) at that time?

-

Did you have a:

Wish to live?

Wish to die?

Reason for living or dying?

<Assess suicidal thoughts>

I would like to you think about your thoughts and the types of thought you have. Would you say you have an active suicidal desire? Passive suicidal desire?

What is the duration of your thoughts? How long do they last?

What is the frequency of your ideation? How often do they happen?

What is your attitude toward ideation? How do you feel about your thought?

Do you have control over your thoughts?

<Assess coping mechanisms>

-

Can you tell me how you dealt with the thoughts about harming yourself or dying?

Who did you tell about these thoughts that you were having? (Probe: family, friend, spouse/partner)

If No one, why not?

<Assess care-seeking>

Did you seek medical care for your thoughts about harming yourself or dying with that first episode? For example, help from a doctor, a therapist, a counselor, a social worker, or a nurse.

-

If Yes:

Who did you go to for help?

Why did you decide to seek care?

How did you decide where to go?

How did it feel to make that first visit?

Was it easier or more difficult than you had imagined?

Is there anything that would have made it easier or more likely for you to seek care?

-

If No:

Why did you choose to not seek help?

Is there anything that would have made it easier or more likely for you to seek care?

Is there anything that would have made it harder or more likely for you to seek care?

<Assess comordibities>

Many people with thoughts about harming yourself or dying have other episodes of diagnosed mental health [emotional] disorders. Has this been the case for you?

-

If Yes, can you tell me more about [emotional] mental health diagnoses you have had since that first episode that we just discussed?

If No one, why not?

Have you had anymore episodes since then? If yes:

What are the episodes like for you now?

Can you tell me how you deal with the episodes now?

Who do you talk to about the episodes when you have them? (Probe: family, friend, spouse/partner)

-

Have you sought care for any of these subsequent episodes?

-

If Yes: Now I want to ask about the treatments that your doctors or other providers have recommended to you. This includes medication, therapy, or other treatments they might have recommended.

Can you tell me what treatments you have tried?

What was good or bad about those treatments?

-

If No: I know that you said you have not seen a medical provider about your mental health.

Have you seen anyone else about it?

Have you tried any over-the-counter or non-traditional therapies?

Are there any therapies, traditional or non-traditional, that you have thought you may be interested in trying?

-

[Has anyone ever suggested to you or diagnosed you as having depression or anxiety?]

Analysis

All interviews were analyzed using thematic network analysis (Attride-Striling, 2001). Our analytical approach included three raters reading all transcripts from each interview and creating codes related to the literature. Each interview was independently coded by all three raters, and codes were recapitulated as a team to ensure quality control. Review of the data revealed initial codes, such as grieving, family death, therapist, and psychiatric hospitalization. The coding framework of 89 original codes was reiterated and reapplied to earlier transcripts as it was developed. In accordance with thematic analysis, data that did not fit into the coding framework were reviewed and discussed by the three raters. Codes were then cross-checked for co-occurrence and grouped into themes. Co-occurring codes (frequently used codes that describe the same set of experiences) were produced using Atlas ti 6.2 qualitative data management software (Atlas.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) and then reviewed by all three raters to minimize overlap and redundancy of codes. For example, “wishes to die” as a code often overlapped with “thoughts of death” and “ideation,” hence all three codes were collapsed into one universal code: “thoughts.” Finally, after codes and co-occurring codes were reviewed, all codes were synthesized into themes. Themes were then applied to the transcripts and synthesized into organizing themes. Of the six initial organizing themes, only four remained after the network analysis was applied to the data. All coding and thematic networks were cross-checked to ensure agreement among coders. The thematic networks were interpreted as connecting the experience of suicidality to the perinatal period. Each step of analysis was reviewed and organized collaboratively by the coders.

Results

Thirty-six percent of this sample was White (n=5); 28.5% were Multiracial (n=4); 21.5% were Asian (n=3), and 14% were Black (n=2). The average age of participants was 29.5 years (range 19–40 years, SD =7.46). Half of the sample was multiparous (n=7). A total of 36% reported co-morbid probable major depression (n=5), and 28.5% reported co-morbid probable minor depression (n=4). In addition, 42.8% reported high levels of psychosocial stress (n=6); half reported a history of substance use (n=7), and 14.2% reported current domestic violence (n=2).

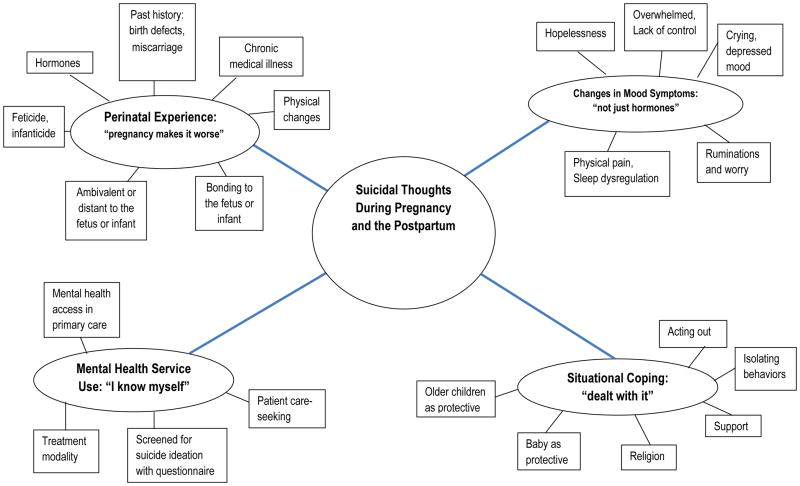

Themes were grouped and connected to organizing themes (Figure 1). The organizing themes were networked together, depending on how they related to suicidality during the perinatal period. Within the four organizing themes, three subthemes were described. Subthemes were necessary to introduce areas not thoroughly discussed in the literature while at the same time not dominant enough to become organizing themes. Defining subthemes was necessary as well, to introduce areas not thoroughly discussed in the literature and not dominant enough to qualify as organizing themes. The subthemes (family history of suicide, feticide-infanticide, and postpartum bonding) provided critical perspectives related to the experience of suicidality during pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Thematic Analysis of Interview Data on Views and Experiences of Suicidal Ideation during the Perinatal Period (n=14)

Organizing Themes

Data were organized into four unique themes, including changes in mood, situational coping, mental health service use, and the perinatal experience (Figure 1), which represented the various social factors mentioned by participants in relation to suicidal ideation.

Theme 1 – Changes in Mood Symptoms: “Not just hormones”

Mood symptoms as an organizing theme included somatic symptoms, such as physical pain and sleep dysregulation. In describing the connection between mood and physical pain, one patient described the relationship between mental distress and physical changes:

[I]t was just a very, very, very rough time in my life, and it was—my mental pain was so strong, that it was physically painful. I was just—my whole body would ache, and I literally cried myself to sleep every single night. Hysterically crying, every night, and it was just exhausting, and I wouldn’t want to get out of bed. I missed weeks and weeks of work. I barely ate. I mean, during that pregnancy, I only gained 18 pounds.” [postpartum patient – ideation, attempt]

Participants described stressful situations as related to changes in mood. These periods of situational stress were described as a time of “having no control” and being terrified of the future. During these periods of fear, several respondents considered suicide as a way to escape stressors. The experience of overwhelming situations and changes in mood was expressed by one participant as follows:

“…, the reason why I get sadness is because, … I’m going through divorce and the whole thing between us, was [my husband] got my family involved and had their word against me. I have two sons that were with me, and they were taken away from me. Now I only have a one son that lives with me now. Now this time I’m pregnant and it helps me a little bit, but my son is the only one who cheers me up. He helps me and comforts me.” [antenatal patient - ideation]

We also found changes in mood related to ruminations or intense worry. Changes in mood were described as part of a lifelong experience with mood disorders. For some, the pregnancy was expected to be a turbulent experience of changes in mood due to hormonal changes or a discontinuation of psychiatric medication. As exemplified by one participant below, several of the participants discontinued their psychiatric medications during pregnancy but later felt the need to resume medication for mood symptoms.

“I stopped all medications when I got pregnant.”[postpartum patient - ideation]

“I don’t know that I would have had the wherewithal to go back on my meds when I did. I should have gone back on them earlier.”[postpartum patient - ideation]

For some respondents with a history of suicidality, the decision was made to initiate a regimen of antidepressants. The rationale for starting medication was to improve mood and control suicidal thoughts in an effort to avoid a subsequent suicide attempt. However, others decided to abstain from all psychiatric medications during pregnancy for fear that these medications would harm their unborn children. The change in mood symptoms was a salient theme across all respondents, including those who were not depressed.

Theme 2 - Stress and Coping: “I dealt with it”

During the interviews many women expressed how their experience with suicide ideation was a function of coping with multiple stressors. As a theme, coping was divided into two axes: negative and positive coping. Negative coping included codes such as self-harm, acting out, isolating behaviors and pushing people away, escaping situations, and substance or tobacco use during pregnancy. One patient described her behaviors as acting out.

“My mom called me, and had said ‘Hey, you’re out of control, I got a call from your ex-boyfriend saying you wanted to kill yourself and that you tried to attempt and contemplated suicide, and that you’ve been punching stuff two nights in a row, so I’m going to take you to the psychiatric hospital.’” [antenatal patient – ideation, attempt]

Some respondents endorsed self-harm as a form of situational coping both before and after the pregnancy. For one respondent, self-harm (e.g., cutting her arms) was a way to cope with her thoughts.

“Usually just up until I cut myself or sometimes I’d battle in my head. Like if I cut myself, I’d feel better, but then I’d tell myself it would only be temporary relief, it wouldn’t really do any good. And [sometimes] I’d just feel guilty after I’d cut myself, but it would usually just be up until I cut myself [that I felt guilty], because I usually would harm myself when I had those thoughts.” [postpartum patient – self-harm]

Positive coping included thinking of the fetus or infant as a protective factor, the positive role of older children, talking with others for support, religion or spirituality, and the notion of hope of future happiness. Several respondents discussed the role of the fetus as a protective factor. The code “baby as a protective factor” was applied to all data when mothers decided not to attempt suicide because they did not want to harm their fetus.

“So, it’s not his fault; he didn’t do anything. I thought about it, I thought about pills, taking pills. I thought about doing drugs that would just get rid of him, and then break my body down. It was more for me. I was selfish. I wanted to be selfish. I was going to have an abortion, and then I didn’t find out until I was three months…. Now as I think about the baby, I think about him, and I’m ready to be a mother.” [antenatal patient - ideation]

“…Let’s kill myself, because what’s the use? But the only thing I think that stopped me that night was the baby. It was like, if I take my life, I take her life as well.” [antenatal patient – ideation, self-harm, attempt]

Older children were introduced as a protective factor as well. Despite the intense feelings of suicidal ideation, respondents put the interests of their older children ahead of their desire to commit suicide.

“I talk to myself, or I talk to my mother. I mean, [my thoughts are] just irrational for a moment, and then like, you know, I look at [my baby boy], or [my older girl], or you know, and then I move on. ” [postpartum patient – ideation, attempt]

“I didn’t tell anybody. I just dealt with it in my own way. Now when I have the thoughts, I just go in the bathroom and turn off the light, and just sit there, and really think about it. You know, like is this really what I want to do? What about my kids?” [antenatal patient – ideation, attempt]

Theme 3 - Mental Health Service Use: “I know myself”

In the present study, respondents were uniquely positioned to use mental health services in a prenatal care setting. This model of service delivery presented an opportunity for patients to communicate their needs to clinic staff including obstetricians. For many respondents, pregnancy brought forth new concerns regarding mental health service use. One respondent described her reasoning for starting psychiatric medication after a suicide attempt during her second pregnancy:

“So my first pregnancy, I - my whole situation was very different. I didn’t already have a kid, and I was kind of hysterical about certain things, so…, I guess I was depressed, like mildly depressed at the start of my pregnancy. And then after I had the baby I got, I don’t know if it was postpartum depression or postpartum anxiety, or whatever, but it was kind of bad. I didn’t sleep for, like, ever, and not because of the baby. And so this time, I’m like, on drugs, and in therapy, and I kind of wanted to make sure I didn’t go through the same thing again.” [antenatal patient – ideation, attempt].

In this sample, pregnancy and the postpartum also signified a critical period to seek help for mood disorders and suicidal behaviors. This desire was discussed in terms of preparing to be healthier and enter the role as mother.

“I think because I really wanted to get clean and sober at that time, and I really wanted to just live better, live healthier. And I know that cutting [myself] is really not healthy, and it really doesn’t solve anything. It doesn’t fix anything, and it sure doesn’t help, you know, make me feel better after I do it. And I just didn’t, I wanted to learn new ways to cope with my emotions other than harming myself.” [postpartum patient – self-harm]

Although modes of communicating mental health service needs varied across the sample, the screening questionnaires were used as a tool to communicate mental health needs.

“One thing that would–probably have helped me more would have been for my doctors [at different hospital] to have been more on top of doing questionnaires like what [study hospital] did, to find out about mental health and whatnot. … it’s supposed to be a 15-minute appointment, and I’m looking forward to hearing my baby’s heartbeat. I don’t want to sit there and talk about how I’ve been crying constantly.” [postpartum patient -ideation]

Finally, three of the women in the sample disclosed that, despite having times when they felt incapacitated by sadness or intense feelings of “calm”, they had never had a psychiatric diagnosis or treatment for a mood disorder. For these respondents the encounter with a provider was an appropriate forum to talk about changes in mood and suicidal thoughts.

Theme 4 - Perinatal Experience: “Pregnancy makes it worse”

Respondents described their experiences with suicidality during the perinatal period. Two themes that emerged from this discussion are listed below.

Hormonal changes

Pregnancy is accompanied by a myriad of biological changes; however, the connections among pregnancy, mood disorders and hormonal changes are still being investigated (Bonari et al., 2004; Evans, Heron, Francomb, Oke, & Golding, 2001). As described by the majority of respondents, hormonal changes during pregnancy affected mood more than at other times during the life course.

“Yeah, it just seems like my natural ups and downs [caused the ideation]. Like, plus pregnancy, just somehow led to something worse. And I don’t know, I guess it just must be hormonal. I don’t know exactly what the relationship is, but there seems to be one.” [antenatal patient - ideation]

Birth Trauma

Birth trauma—including miscarriages and pregnancy complications—emerged from the data as being related to suicidal thoughts. Childbirth was anticlimactic for some women, and these women sometimes felt tremendous guilt. For others, the sense of loss and worry resulting from a previous birth trauma resurfaced during the current pregnancy. Respondents described their experiences as follows:

“I also thought to myself that because I had had a miscarriage before [this baby], and I was really still grieving that child, I thought that, well, I’d get to be with that child, too, [in the afterlife]. So I thought that if I killed myself while I was pregnant, that I would be taking that life too. But I thought that in an afterlife we would all be together, and so I just really had these really crazy thoughts.” [postpartum patient – ideation, attempt]

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to examine the views and experiences associated with suicidal ideation among a small group of women who sought prenatal care services. We found four organizing themes that provided a framework to examine perinatal suicidal ideation. First, changes in mood symptoms included the description of physical symptoms, including pain and sleep disturbances. These symptoms are important to recognize, because symptoms related to changes in mood can often be confused with physical changes due to pregnancy. In addition, we found that changes in mood were related to initiating and ending psychiatric medication use during the perinatal period, which is consistent with previous research (Einarson, Selby, & Koren, 2001). Abrupt changes in psychiatric medications during pregnancy have been linked to suicidality (Einarson, et al., 2001). While the safety of antidepressant medication use during pregnancy is controversial, antepartum inaccurate beliefs related to side effects of medication abound and vary widely across patient populations, and these misperceptions are not limited to psychiatric medications alone. For example, several recent studies have found that medical students, providers, and female patients overestimate the risk of all medications in terms of teratogenic effects or adverse birth outcomes (Nordeng, Ystrøm, & Einarson, 2010; Sanz, Gómez-López, & Martínez-Quintas, 2001). Therefore, health care providers should discuss psychiatric medication usage with patients throughout the perinatal period and monitor any mood changes that accompany changes in medication type or dose.

Second, situational coping was a central theme for many respondents. For this group of women, suicidal thoughts provided a potential solution to the changes in mood and/or intense stressors. Congruent with past findings, we found in our study sample that situational stressors were related to perinatal suicidality (S. Chan & Levy, 2004; Gausia, Fisher, Ali, & Oosthuizen, 2009). Negative coping responses to stressors during pregnancy included social isolation, acting out, and abusing other individuals in the home. For some respondents, a suicide attempt was made during pregnancy (or immediately after childbirth) explicitly to escape a stressful situation. Respondents also shared views on positive coping responses, including relying on their social support system. In our sample, coping responses varied by parity s. We found multiparous respondents agreeing that their children prevented them from committing suicide. Further research is needed to understand how children affect maternal suicidality and the related implications for clinical practice.

Third, mental health service use and care-seeking behavior was another theme that emerged in our study. For most respondents, the clinic questionnaire was used as a tool to communicate their mental health needs to their obstetrician and/or their clinical care team members. This study provided evidence to support screening for suicidal ideation in the context of mood disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum in a prenatal care setting (Gavin, et al., 2011; Melville, et al., 2010; Yonkers, Vigod, & Ross, 2011). While screening for suicidal ideation provided some insight into this at-risk population, it did not provide in-depth information about the participants’ history of suicidality prior to the perinatal period. We found various levels of reported risks for suicide, depending on the number of past attempts or past psychiatric hospitalizations. This is important, because those who have made multiple attempts have different risk factors than individuals who experience only suicidal ideation (Mandrusiak et al., 2006). Nevertheless, this study confirmed the importance of screening during the perinatal period as an essential clinical tool for identifying patients in need of treatment for suicidality in the context of mood disorders (Rudd et al., 2006).

Finally, respondents in this study revealed the unique intersection of suicidality during the perinatal period with hormonal changes, mood symptoms, and birth trauma. Birth trauma due to the loss of an infant or miscarriage has been associated with suicidality among perinatal women (Babu, et al., 2008; Rudd, Mandrusiak, et al., 2006). As described by women with previously diagnosed mood disorders in our study, the experience of pregnancy exacerbated the severity of mood symptoms and fears related to experiencing a depressive episode or not being able to respond appropriately to changes in hormones.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the sample included only women who were screened for suicidal ideation during a 6-month period at a single university-based medical center. We were not able to determine what proportion of all patients participated in questionnaire for the parent study, thus we are not able to determine potential selection and participant biases. Ideally, all clinic patients should have been screened for suicidal ideation; however, clinic staff was unable to perform universal screening. Therefore, it is possible that not all women experiencing suicidal ideation or self-harm in this population were captured. Second, this study did not intentionally inquire about psychiatric medication use; therefore, researchers were unable to discuss the experience of changes or improvement in mood related to taking psychiatric medication (e.g., antidepressants). Accordingly, we are unable to determine the proportion of women who were taking antidepressant medication prior to pregnancy. Third, given the rarity of suicidal ideation among perinatal women and our limited sample size, we were unable to gather a more comprehensive picture of suicidality during the perinatal period. Finally, the study was limited to inquiring only about suicidal thoughts and behaviors and did not explicitly ask about self-harm behaviors other than those related to suicide.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to explore the phenomenon of suicide during pregnancy. Research is also needed to explore various kinds of self-harm during pregnancy as a form of concealed suicidal behavior. As one patient with a history of depression said, “Pregnancy makes it worse,” and while this study was able to gain a description of the experience, researchers were unable to quantify the unique contribution of pregnancy as a moderator, though clearly the relationship between pregnancy and suicide is important. Further exploration of perinatal suicidal behaviors can aid in understanding the motives behind feticide and infanticide. Future studies are needed to explore the role of social support and children as protective for suicide prevention.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible by grants from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources funding sources TL1 RR025016 and 1KL2RR025015-01 and Health Services Division of NIMH: T32 MH20021-14 (Dr. Katon).

Footnotes

There are no conflicting interests.

References

- Appleby L. Suicide during pregnancy and in the first postnatal year. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1991;302(6769):137–140. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6769.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attride-Striling J. Thematic networks: an analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research. 2001;1(3) [Google Scholar]

- Babu G, Subbakrishna D, Chandra P. Prevalence and correlates of suicidality among Indian women with postpartum psychosis in an inpatient setting. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;42(11) doi: 10.1080/00048670802415384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley SM, Melville JL, Berry BD, Katon WJ. Implementing a clinical and research registry in obstetrics: overcoming the barriers. General hospital psychiatry. 2007;29(3):192. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birndorf CA, Madden A, Portera L, Leon AC. Psychiatric symptoms, functional impairment, and receptivity toward mental health treatment among obstetrical patients. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2001;31(4):355–365. doi: 10.2190/5VPD-WGL1-MTWN-6JA6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonari L, Pinto N, Ahn E, Einarson A, Steiner M, Koren G. Perinatal Risks of Untreated Depression During Pregnancy. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 2004;49(11):726. doi: 10.1177/070674370404901103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen A, Stewart N, Baetz M, Muhajarine N. Antenatal depression in socially high-risk women in Canada. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:414–416. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.078832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Levy V. Postnatal depression: a qualitative study of the experiences of a group of Hong Kong Chinese women. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2004;13(1):120–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SW, Williamson V, McCutcheon H. A comparative study of the experiences of a group of Hong Kong Chinese and Australian women diagnosed with postnatal depression. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2009;45(2):108–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: A leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(3):471–477. doi: 10.2105/Ajph.2003.029868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung-Hey C, Shing-Yaw W, Ue-Lin C, Ying-Fen T, Fan-Hao C. Being reborn: the recovery process of postpartum depression in Taiwanese women. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2006;54(4) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Class QA, D’Onofrio BM, Lichtenstein P, Langstrom N. Timing of prenatal maternal exposure to severe life events and adverse pregnancy outcomes: A population study of 2.6 million pregnancies. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2011;73(3):234–241. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820a62ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copersino M, Jones H, Tuten M, Svikis D. Suicidal Ideation Among Drug-Dependent Treatment-Seeking Inner-City Pregnant Women. Journal of Maintenance in the Addictions. 2008;3:53–64. doi: 10.1300/J126v03n02_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copersino ML, Jones H, Tuten M, Svikis D. Suicidal Ideation Among Drug-Dependent Treatment-Seeking Inner-City Pregnant Woman. Journal of Maintenance in the Addictions. 2005;3(2/3/4) doi: 10.1300/J126v03n02_07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coryell W, Young EA. Clinical predictors of suicide in primary major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):412–417. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry MA, Burton D, Fields J. The Prenatal Psychosocial Profile: a research and clinical tool. Research in nursing & health. 1998;21(3):211–219. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199806)21:3<211::aid-nur4>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry MA, Campbell RA, Christian M. Validity and reliability testing of the Prenatal Psychosocial Profile. Research in nursing & health. 1994;17(2):127–135. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeizel AE, Timar L, Susanszky E. Timing of suicide attempts by self-poisoning during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics : the Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1999;65(1):39. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Einarson A, Selby P, Koren G. Abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy: fear of teratogenic risk and impact of counseling. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2001;26(1) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J, Heron J, Francomb H, Oke S, Golding J. Cohort study of depressed mood during pregnancy and after childbirth. British Medical Journal. 2001;323(7307):257–260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gausia K, Fisher C, Ali M, Oosthuizen J. Antenatal depression and suicidal ideation among rural Bangladeshi women: a community-based study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2009;12(5) doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AR, Tabb KM, Melville JL, Guo YQ, Katon W. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation during pregnancy. Archives of Womens Mental Health. 2011;14(3):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0207-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbody S, Sheldon T, Wessely S. Health policy - Should we screen for depression? British Medical Journal. 2006;332(7548):1027–1030. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7548.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Faisal-Cury A, Chan YF, Tabb K, Katon W, PRM Suicidal ideation during pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors among low-income women in São Paulo, Brazil. Archives of Womens Mental Health. 2012;2:135–138. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0263-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Borges G, Nock M, Wang PS. Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. JAMA. 2005;293(20):2487–2495. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2487. 293/20/2487 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrusiak M, Rudd MD, Joiner TE, Berman AL, Van Orden KA, Witte T. Warning signs for suicide on the Internet: A descriptive study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36(3):263–271. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris RW, Berman AL, Silverman MM, Bongar BM. Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. New York: Guilford Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McClure CK, Katz KD, Patrick TE, Kelsey SF, Weiss HB. The Epidemiology of Acute Poisonings in Women of Reproductive Age and During Pregnancy, California, 2000–2004. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2010:2. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane J, Parker B. Assessing for abuse during pregnancy. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992;267(23) doi: 10.1001/jama.267.23.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville JL, Gavin A, Guo YQ, Fan MY, Katon WJ. Depressive Disorders During Pregnancy Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Large Urban Sample. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;116(5):1064–1070. doi: 10.1097/Aog.0b013e3181f60b0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Zahnd EG, Klein D. Alcohol and Drug CAGE Screeners for Pregnant, Low-Income Women: The California Perinatal Needs Assessment. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research. 1998;22(1):121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newport DJ, Levey LC, Pennell PB, Ragan K, Stowe ZN. Suicidal ideation in pregnancy: assessment and clinical implications. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2007;10(5):181–187. doi: 10.1007/s00737-007-0192-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordeng H, Ystrøm E, Einarson A. Perception of risk regarding the use of medications and other exposures during pregnancy. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2010;66(2) doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. British Medical Bulletin. 2003a;67:219–229. doi: 10.1093/Bmb/Ldg011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oates M. Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003b;183:279–281. doi: 10.1192/bjp.183.4.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and Suicide During the Perinatal Period Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2011;118(5):1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/Aog.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris R, Bolton RE, Weinberg MK. Postpartum depression, suicidality, and mother-infant interactions. Arch Women’s Ment Health Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2009;12(5):309–321. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Berman AL, Joiner TE, Nock MK, Silverman MM, Mandrusiak M, Witte T. Warning signs for suicide: Theory, research, and clinical applications. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36(3):255–262. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Mandrusiak M, Joiner TE, Berman AL, Van Orden KA, Hollar D. The emotional impact and ease of recall of warning signs for suicide: A controlled study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36(3):288–295. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz E, Gómez-López T, Martínez-Quintas MJ. Perception of teratogenic risk of common medicines. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 2001;95(1):127–131. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282(18):1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. joc90770 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Hornyak R, McMurray J. Validity and utility of the PRIME-MD patient health questionnaire in assessment of 3000 obstetric-gynecologic patients: the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire Obstetrics-Gynecology Study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;183(3):759–769. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106580. S0002-9378(00)78686-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valladares E, Pena R, Ellsberg M, Persson LA, Hogberg U. Neuroendocrine response to violence during pregnancy - impact on duration of pregnancy and fetal growth. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2009;88(7):818–823. doi: 10.1080/00016340903015321. Pii 911751999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Vigod S, Ross LE. Diagnosis, pathophysiology, and management of mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):961–977. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821187a700006250-201104000-00029. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]