Abstract

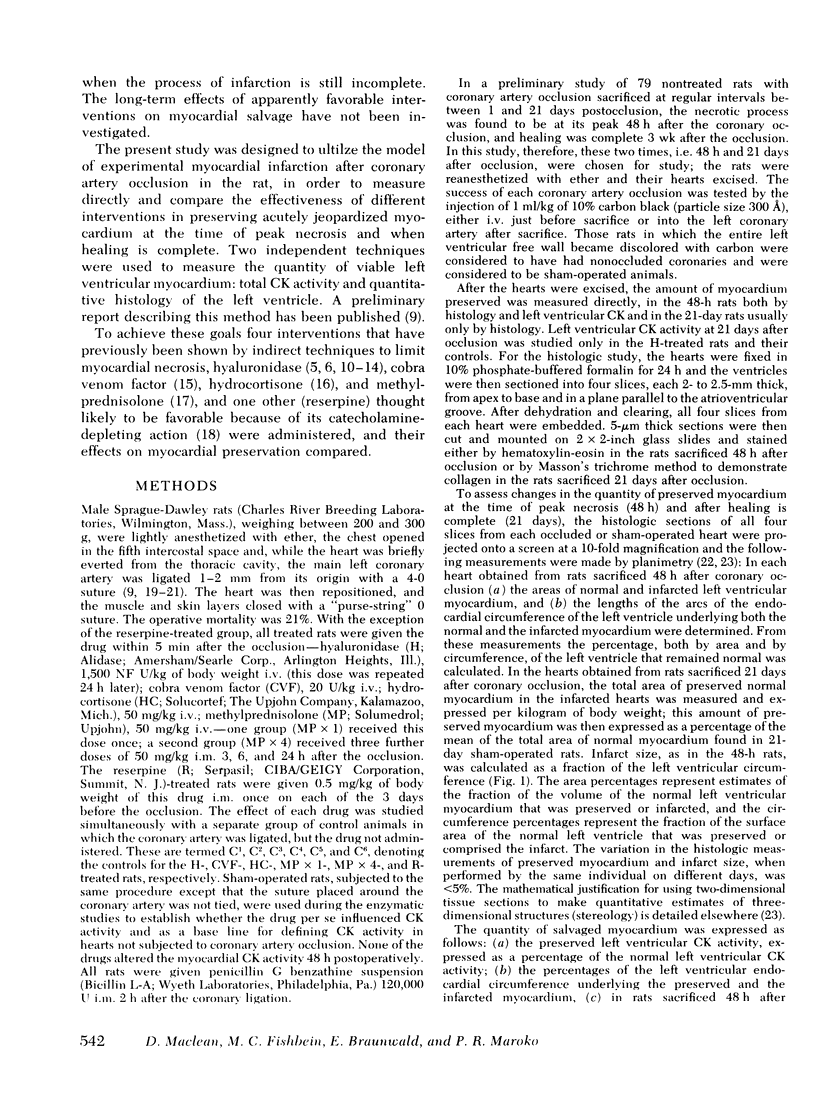

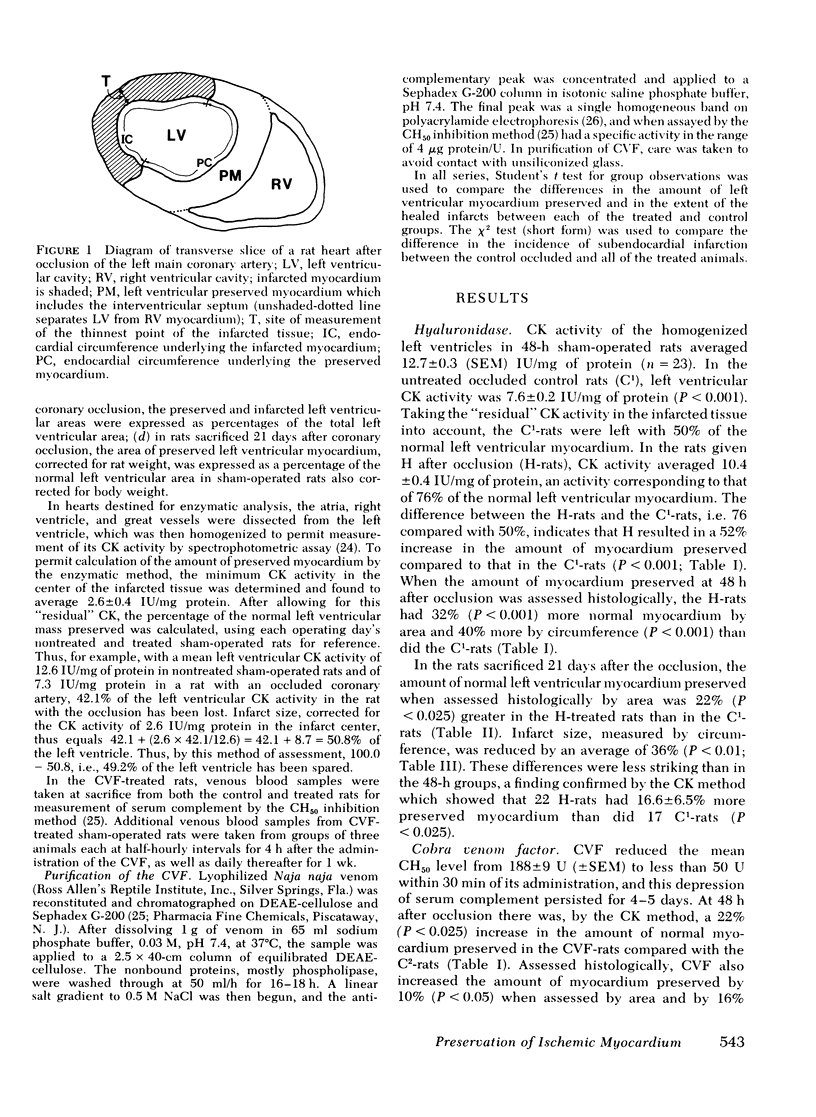

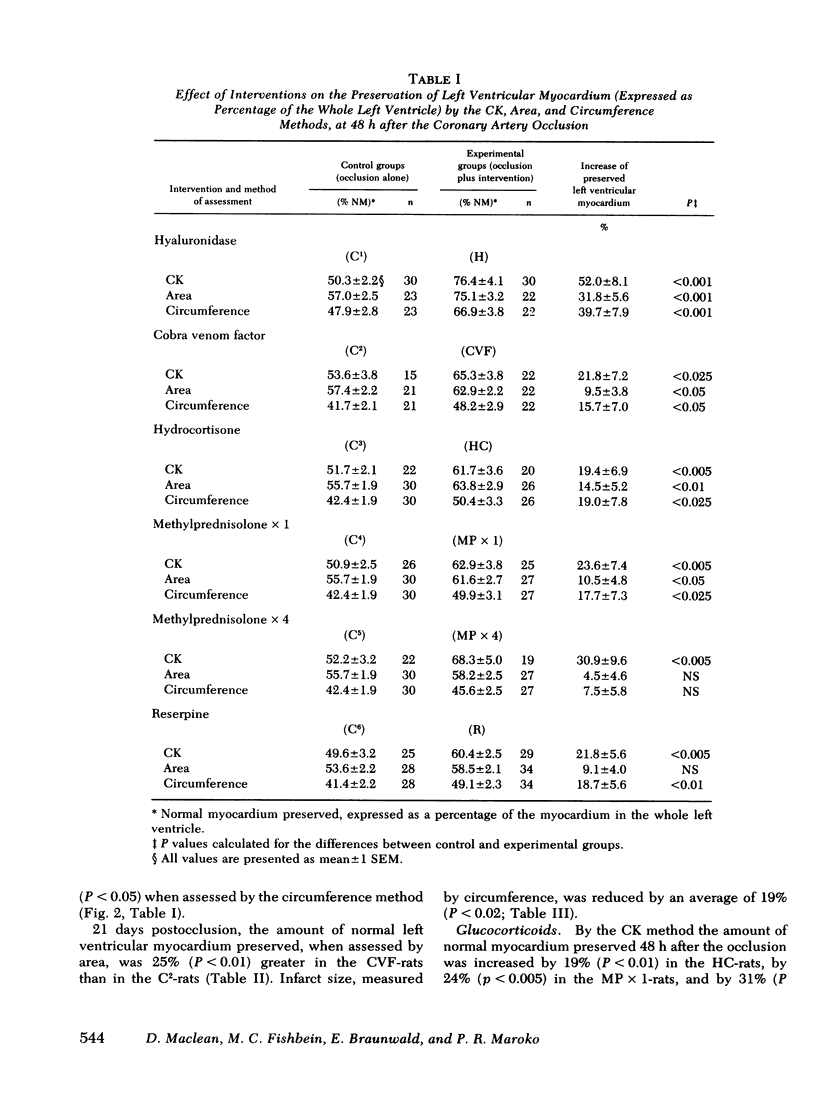

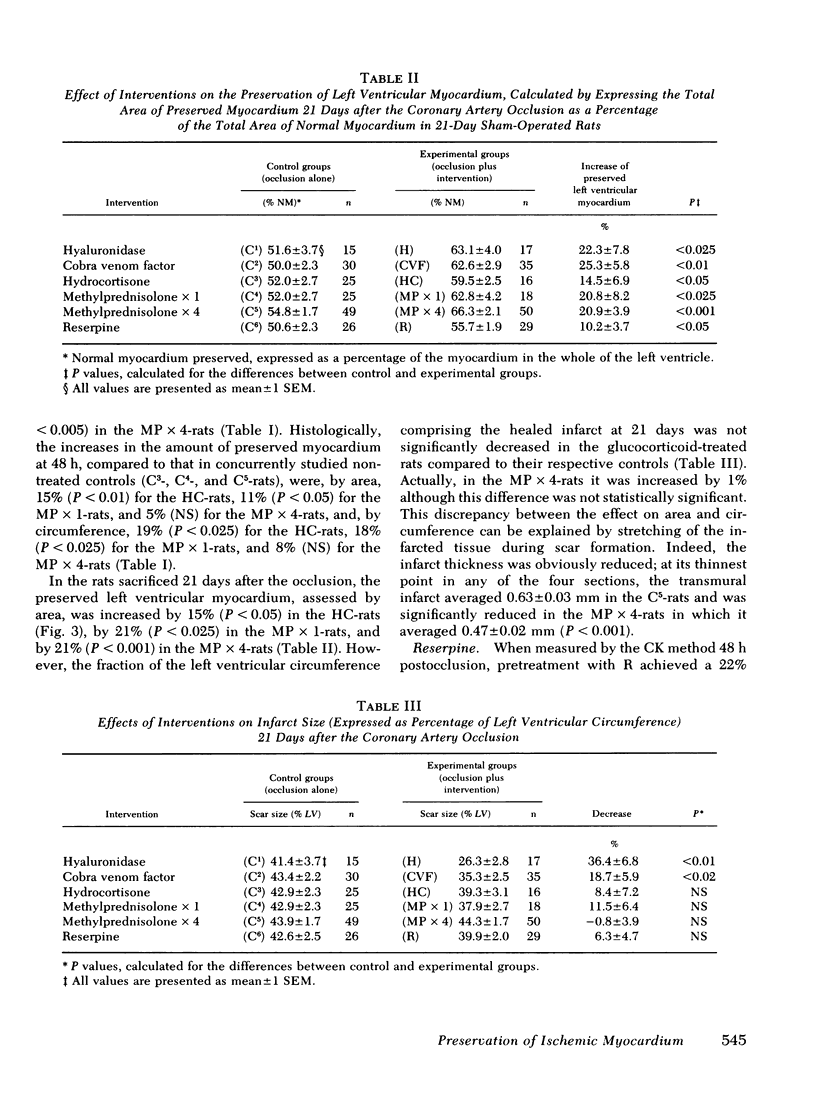

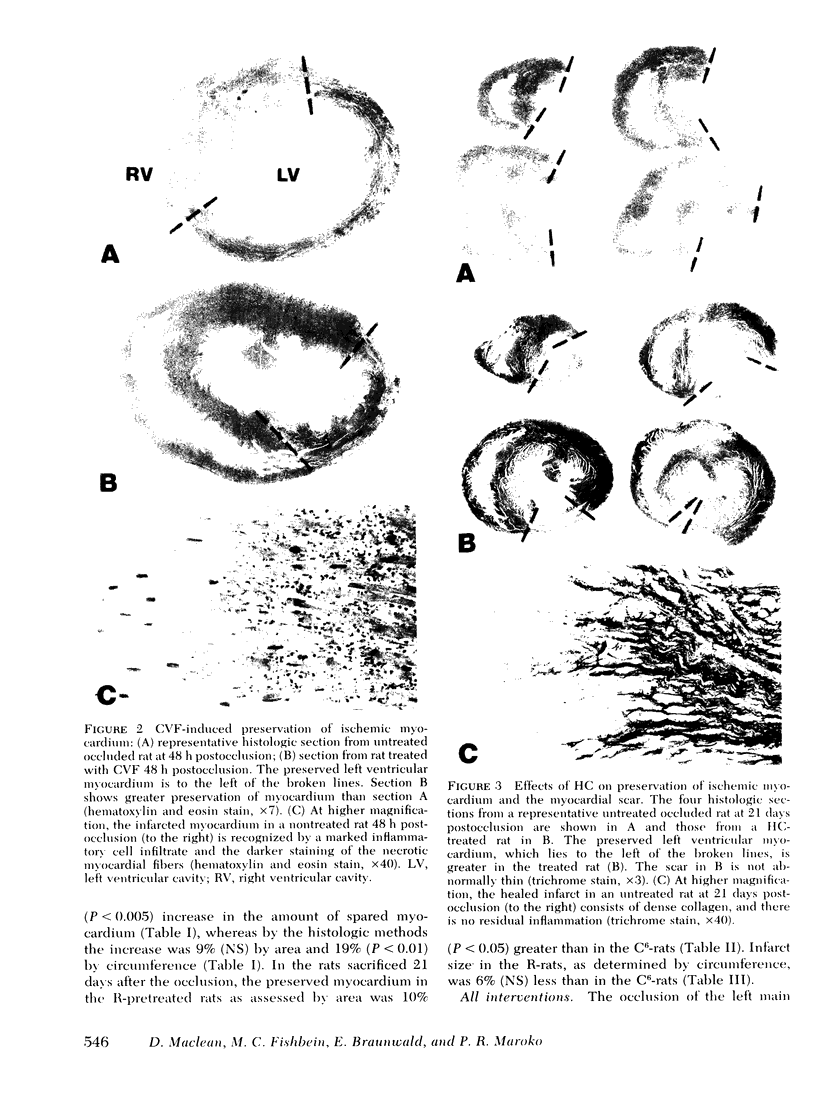

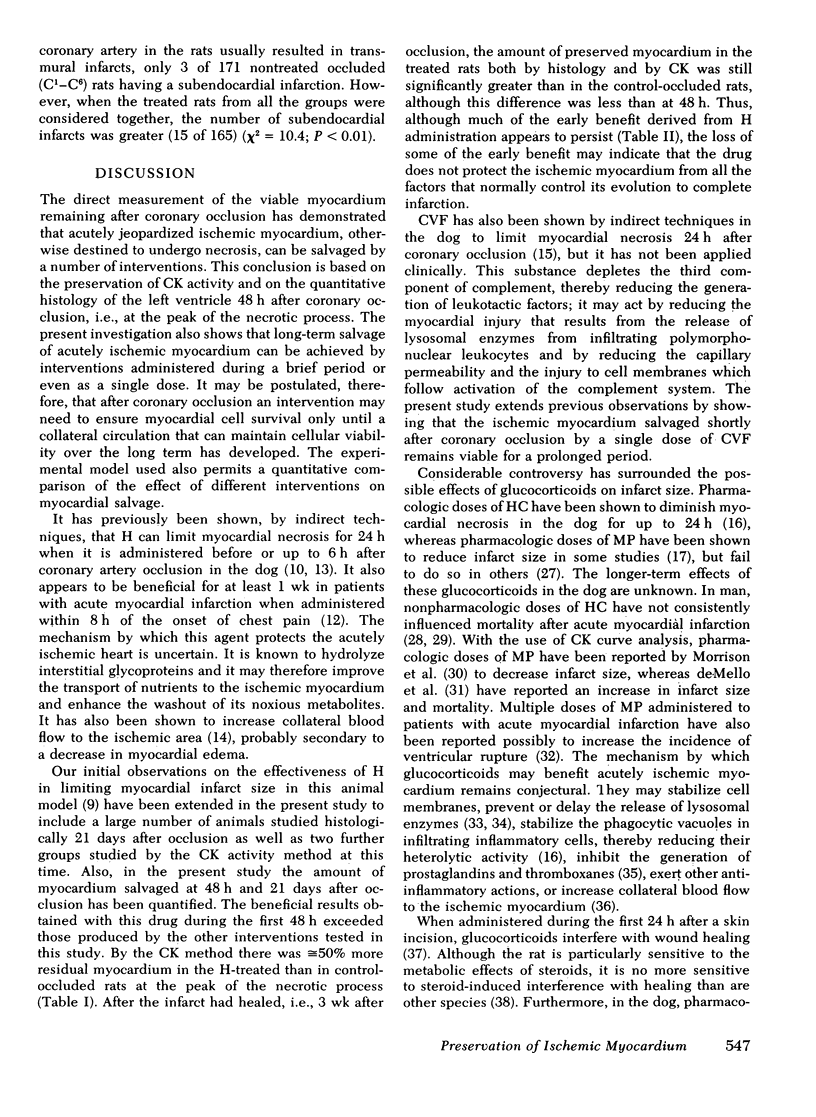

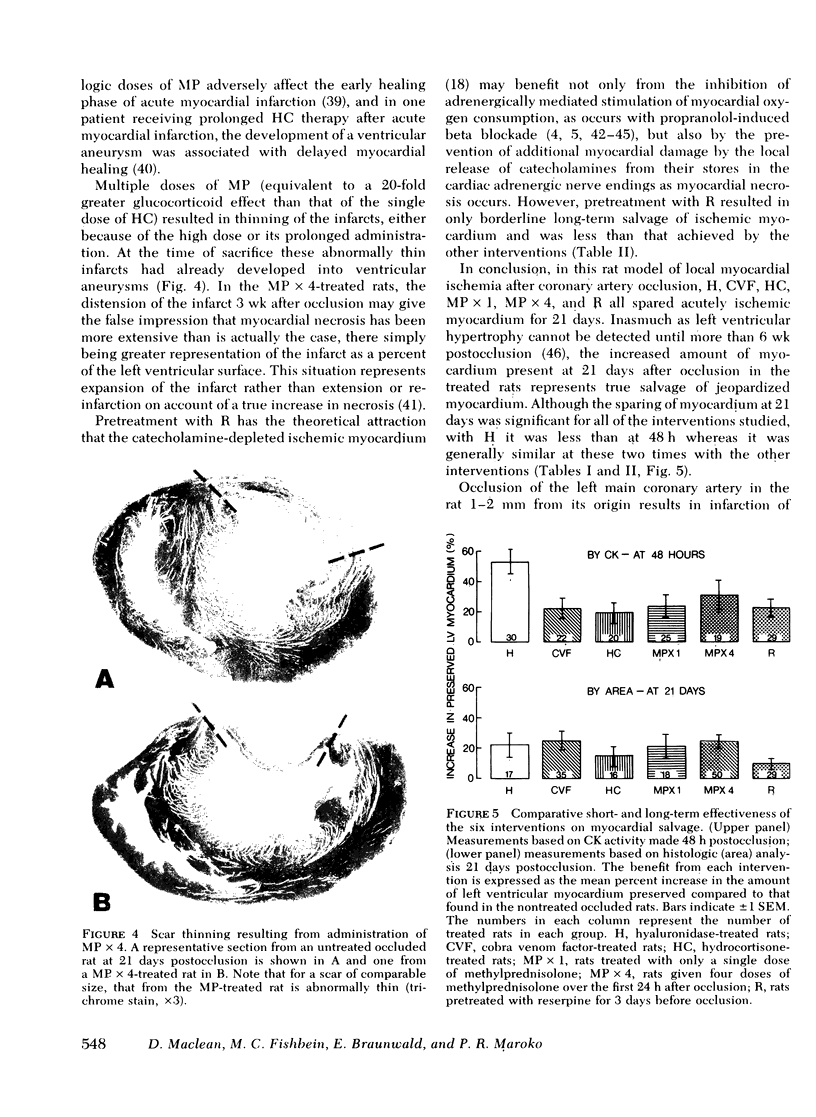

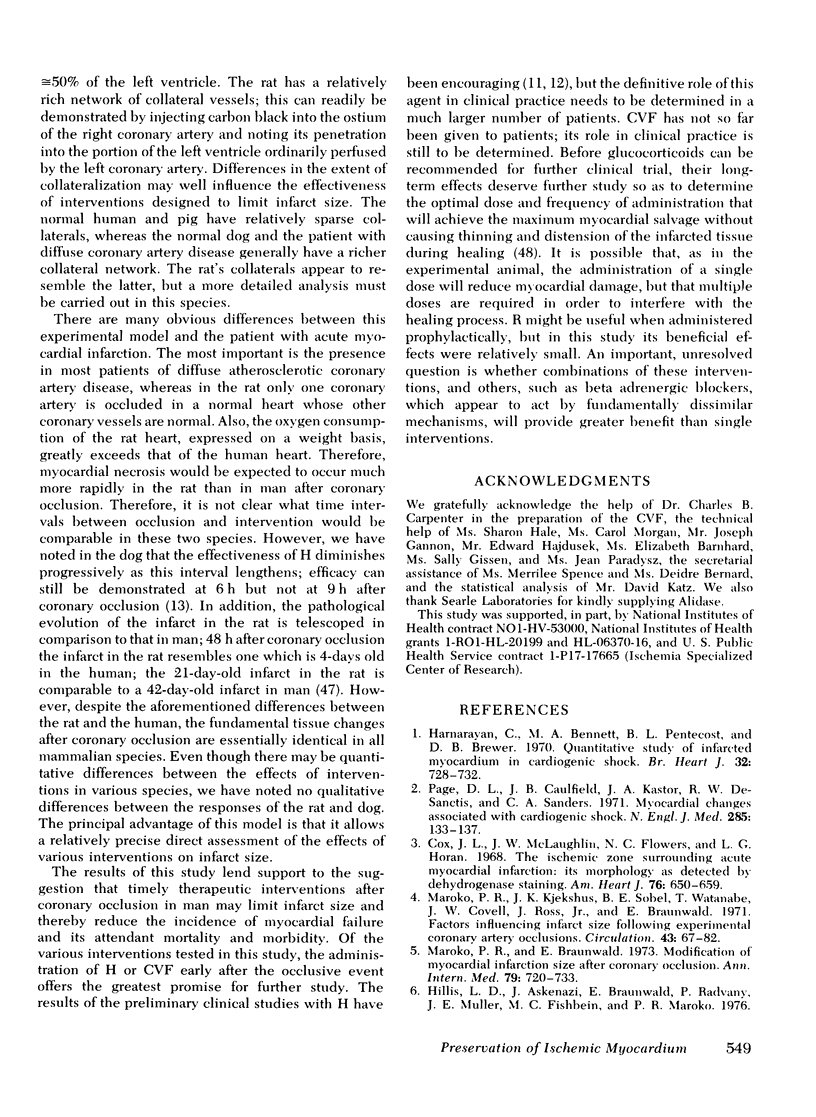

The results of experiments with indirect methods have suggested that various interventions reduce infarct size after coronary artery occlusion. To determine and quantify directly both the short- and long-term effects of several interventions on myocardial salvage without relying on indirect methods, the left coronary artery was occluded in 880 rats; they were then given either no treatment or one of the following interventions: (a) hyaluronidase, an enzyme that hydrolyzes interstitial glycoproteins, 1,500 National Formulary (NF) U/kg i.v. 5 min and 24 h after occlusion; (b) cobra venom factor, a protein that depletes the third component of complement, 20 U/kg i.v. 5 min after occlusion; (c) a glucocorticoid: hydrocortisone, 50 mg/kg i.v. 5 min after occlusion; or the five-fold more potent methylprednisolone (MP): (i) 50 mg/kg i.v. 5 min after occlusion or (ii) 50 mg/kg i.v. 5 min after occlusion followed by 50 mg/kg i.m. 3, 6, and 24 h after occlusion; or (d) reserpine, an agent that depletes the heart of catecholamines, 0.5 mg/kg i.m. once on each of the 3 days before occlusion. The animals were sacrificed either 2 days after occlusion, i.e., at the time of peak necrosis, or after 3 wk, i.e., after the infarct was completely healed. The amount of preserved myocardium was then assessed by two independent techniques: planimetric measurement of serial histologic sections and creatine kinase activity of the whole left ventricle. The amount of normal myocardium preserved at 21 days postocclusion was significantly increased, by 22.3±7.8% (P < 0.025) after the administration of hyaluronidase, by 25.3±5.8% (P < 0.005) after cobra venom factor, by 14.5±6.9% (P < 0.05) after hydrocortisone, by 20.8±8.2% (P < 0.025) after the single dose of MP, by 20.9±3.9% (P < 0.001) after the four doses of MP, and by 10.2±3.7% (P < 0.05) as a result of pretreatment with reserpine. The four doses of MP significantly thinned the infarct—by 25.6±2.9% (P < 0.001)—and although ventricular rupture did not occur, the intervention caused distension of the left ventricle as a result of stretching of the infarcted tissue during scar formation. Thus, myocardium acutely jeopardized by ischemia can be preserved on a long-term basis.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Askenazi J., Hillis L. D., Diaz P. E., Davis M. A., Braunwald E., Maroko P. R. The effects of hyaluronidase on coronary blood flow following coronary artery occlusion in the dog. Circ Res. 1977 Jun;40(6):566–571. doi: 10.1161/01.res.40.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEIN H. J. The pharmacology of Rauwolfia. Pharmacol Rev. 1956 Sep;8(3):435–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballow M., Cochrane C. G. Two anticomplementary factors in cobra venom: hemolysis of guinea pig erythrocytes by one of them. J Immunol. 1969 Nov;103(5):944–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai D., Plavnick J., Hazani A., Einath R., Kleinhaus N., Kanter Y. Use of hydrocortisone in the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. Summary of a clinical trial in 446 patients. Chest. 1972 May;61(5):488–491. doi: 10.1378/chest.61.5.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulkley B. H., Roberts W. C. Steroid therapy during acute myocardial infarction. A cause of delayed healing and of ventricular aneurysm. Am J Med. 1974 Feb;56(2):244–250. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(74)90603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J. L., McLaughlin V. W., Flowers N. C., Horan L. G. The ischemic zone surrounding acute myocardial infarction. Its morphology as detected by dehydrogenase staining. Am Heart J. 1968 Nov;76(5):650–659. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(68)90164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deloche A., Fontaliran F., Fabiani J. N., Pennecot G., Carpentier A., Dubost C. Etude expérimentale de la revascularisation chirurgicale précoce de l'infarctus du myocarde. Ann Chir Thorac Cardiovasc. 1972 Jan;11(1):89–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold H. K., Leinbach R. C., Maroko P. R. Propranolol-induced reduction of signs of ischemic injury during acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Nov 23;38(6):689–695. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90344-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnarayan C., Bennett M. A., Pentecost B. L., Brewer D. B. Quantitative study of infarcted myocardium in cardiogenic shock. Br Heart J. 1970 Nov;32(6):728–732. doi: 10.1136/hrt.32.6.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis L. D., Fishbein M. C., Braunwald E., Maroko P. R. The influence of the time interval between coronary artery occlusion and the administration of hyaluronidase on salvage of ischemic myocardium in dogs. Circ Res. 1977 Jul;41(1):26–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNS T. N. P., OLSON B. J. Experimental myocardial infarction. I. A method of coronary occlusion in small animals. Ann Surg. 1954 Nov;140(5):675–682. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195411000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjekshus J. K., Sobel B. E. Depressed myocardial creatine phosphokinase activity following experimental myocardial infarction in rabbit. Circ Res. 1970 Sep;27(3):403–414. doi: 10.1161/01.res.27.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P., Maroko P. R., Bloor C. M., Sobel B. E., Braunwald E. Reduction of experimental myocardial infarct size by corticosteroid administration. J Clin Invest. 1973 Mar;52(3):599–607. doi: 10.1172/JCI107221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lysosomal mechanisms in production of tissue damage during myocardial ischemia and the effects of treatment with steroids. Am Heart J. 1976 Mar;91(3):394–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(76)80226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean D., Fishbein M. C., Maroko P. R., Braunwald E. Hyaluronidase-induced reductions in myocardial infarct size. Science. 1976 Oct 8;194(4261):199–200. doi: 10.1126/science.959848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Braunwald E. Modification of myocardial infarction size after coronary occlusion. Ann Intern Med. 1973 Nov;79(5):720–733. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-5-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Davidson D. M., Libby P., Hagan A. D., Braunwald E. Effects of hyaluronidase administration on myocardial ischemic injury in acute infarction. A preliminary study in 24 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1975 Apr;82(4):516–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-82-4-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Hillis L. D., Muller J. E., Tavazzi L., Heyndrickx G. R., Ray M., Chiariello M., Distante A., Askenazi J., Salerno J. Favorable effects of hyaluronidase on electrocardiographic evidence of necrosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1977 Apr 21;296(16):898–903. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197704212961603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Kjekshus J. K., Sobel B. E., Watanabe T., Covell J. W., Ross J., Jr, Braunwald E. Factors influencing infarct size following experimental coronary artery occlusions. Circulation. 1971 Jan;43(1):67–82. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Libby P., Bloor C. M., Sobel B. E., Braunwald E. Reduction by hyaluronidase of myocardial necrosis following coronary artery occlusion. Circulation. 1972 Sep;46(3):430–437. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.46.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroko P. R., Libby P., Covell J. W., Sobel B. E., Ross J., Jr, Braunwald E. Precordial S-T segment elevation mapping: an atraumatic method for assessing alterations in the extent of myocardial ischemic injury. The effects of pharmacologic and hemodynamic interventions. Am J Cardiol. 1972 Feb;29(2):223–230. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90633-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters T. N., Harbold N. B., Jr, Hall D. G., Jackson R. D., Mullen D. C., Daugherty H. K., Robicsek F. Beneficial metabolic effects of methylprednisolone sodium succinate in acute myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Mar 31;37(4):557–563. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORMAN T. D., COERS C. R. Cardiac hypertrophy after coronary artery ligation in rats. Arch Pathol. 1960 Feb;69:181–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page D. L., Caulfield J. B., Kastor J. A., DeSanctis R. W., Sanders C. A. Myocardial changes associated with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 1971 Jul 15;285(3):133–137. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197107152850301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehder E., Enquist I. F. Species differences in response to cortisone in wounded animals. Arch Surg. 1967 Jan;94(1):74–78. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1967.01330070076016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SANDBERG N. TIME RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ADMINISTRATION OF CORTISONE AND WOUND HEALING IN RATS. Acta Chir Scand. 1964 May;127:446–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SELYE H., BAJUSZ E., GRASSO S., MENDELL P. Simple techniques for the surgical occlusion of coronary vessels in the rat. Angiology. 1960 Oct;11:398–407. doi: 10.1177/000331976001100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatney C. H., MacCarter D. J., Lillehei R. C. Effects of allopurinol, propranolol and methylprednisolone on infarct size in experimental myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Mar 31;37(4):572–580. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell W. E., Kjekshus J. K., Sobel B. E. Quantitative assessment of the extent of myocardial infarction in the conscious dog by means of analysis of serial changes in serum creatine phosphokinase activity. J Clin Invest. 1971 Dec;50(12):2614–2625. doi: 10.1172/JCI106762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shell W. E., Lavelle J. F., Covell J. W., Sobel B. E. Early estimation of myocardial damage in conscious dogs and patients with evolving acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Invest. 1973 Oct;52(10):2579–2590. doi: 10.1172/JCI107450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommers H. M., Jennings R. B. Ventricular fibrillation and myocardial necrosis after transient ischemia. Effect of treatment with oxygen, procainamide, reserpine, and propranolol. Arch Intern Med. 1972 May;129(5):780–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spath J. A., Jr, Lane D. L., Lefer A. M. Protective action of methylprednisolone on the myocardium during experimental myocardial ischemia in the cat. Circ Res. 1974 Jul;35(1):44–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.35.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel W. M., Zannoni V. G., Abrams G. D., Lucchesi B. R. Inability of methylprednisolone sodium succinate to decrease infarct size or preserve enzyme activity measured 24 hours after coronary occlusion in the dog. Circulation. 1977 Apr;55(4):588–595. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.55.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEIBEL E. R. Principles and methods for the morphometric study of the lung and other organs. Lab Invest. 1963 Feb;12:131–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K., Osborn M. The reliability of molecular weight determinations by dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1969 Aug 25;244(16):4406–4412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]