Abstract

Approximately one third of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities have emotion dysregulation and challenging behaviors (CBs). Although research has not yet confirmed that existing treatments adequately reduce CBs in this population, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) holds promise, as it has been shown to effectively reduce CBs in other emotionally dysregulated populations. This longitudinal single-group pilot study examined whether individuals with impaired intellectual functioning would show reductions in CBs while receiving standard DBT individual therapy used in conjunction with the Skills System (DBT-SS), a DBT emotion regulation skills curriculum adapted for individuals with cognitive impairment. Forty adults with developmental disabilities (most of whom also had intellectual disabilities) and CBs, including histories of aggression, self-injury, sexual offending, or other CBs, participated in this study. Changes in their behaviors were monitored over 4 years while in DBT-SS. Large reductions in CBs were observed during the 4 years. These findings suggest that modified DBT holds promise for effectively treating individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Keywords: intellectual disabilities, dialectical behavior therapy, coping skills

INTRODUCTION

Many individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) experience serious challenges. Beyond cognitive limitations, some have additional problems such as comorbid psychiatric disorders, deficits in adaptive coping skills, and excessive maladaptive behaviors. Challenging behaviors (CBs) are defined as “culturally abnormal behavior(s) of such intensity, frequency, or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behavior which is likely to seriously limit the use of, or result in the person being denied access to, ordinary community facilities” (Emerson et al., 2001, p. 3). Research studies have documented that CBs are often found in individuals with IDD, including dangerous behaviors such as aggression, self-injury, sexual offending, fire setting, and stealing, although prevalence estimates vary tremendously across studies. For example, estimates of the prevalence of aggression range from 10% to 45% (Emerson et al., 2001; Grey, Pollard, McClean, MacAuley, & Hastings, 2010; F. Tyrer et al., 2006). There is a broad consensus that behavioral problems impact the lives of many people with IDD and create significant challenges for support providers. Providing necessary support and safety to both IDD individuals and the community is a challenging and expensive task. High levels of supervision; staff injuries; staff turnover; out-of-state placements; and utilization of multiple state and local disabilities, mental health, and corrections resources are common factors that increase the costs of service delivery.

ETIOLOGY OF CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS

Numerous complex issues must be effectively treated in order to achieve significant long-term reductions in CBs in individuals with IDD. Many of these behaviors are associated with poor coping skills (Janssen, Schuengel, & Stolk, 2002; Nezu, Nezu, & Arean, 1991; F. Tyrer et al., 2006), high levels of frustration (F. Tyrer et al., 2006), depression (Reiss & Rojahn, 1993), mood swings (F. Tyrer et al., 2006), high levels of stress (Janssen et al., 2002), and insecure attachments (Janssen et al., 2002). A cross-sectional study of 296 adults with mild/moderate IDD who exhibited aggression found that increased levels of mental health problems (psychosis, autism, and mood disorders), impulsivity, antisocial tendencies, less ability to tolerate frustration, and lower levels of social and vocational involvement were associated factors (Crocker, Mercier, Allaire, & Roy, 2007). Although the people with IDD who demonstrate behavior problems are a heterogeneous group, it appears that emotion and cognitive regulation skills deficits (Janssen et al., 2002; Nezu et al., 1991; F. Tyrer et al., 2006; Whitman, 1990) and mental health issues (Crocker et al., 2007; Reiss & Rojahn, 1993; F. Tyrer et al., 2006) contribute to their behavioral dysregulation. Given that emotion dysregulation appears to be a key contributing factor to CBs, it is essential that a treatment of behavior problems build self-regulation capacities. Although research addressing emotion dysregulation in the general population is expanding, unfortunately significantly less research exists on emotion regulation treatment for people with IDD (McClure, Halpern, Wolper, & Donahue, 2009).

TREATMENT OPTIONS

There are many studies suggesting that psychosocial interventions reduce CBs in individuals with IDD (Benson, Rice, & Miranti, 1986; Carr & Carlson, 1993; S. T. Harvey, Boer, Meyer, & Evans, 2009; Heyvaert, Maes, & Onghena, 2010; Luyben, 2009; Neidert, Dozier, Iwata, & Hafen, 2010; Prout & Nowak-Drabik, 2003; Willner, 2005). However, due to the difficulties conducting research on this population, most studies have significant methodological limitations, including nonrandomized designs, and inadequate assessment of outcomes (Gustafsson et al., 2009; Hassiotis & Sturmey, 2010; Keenan & Dillenburger, 2011; Willner, 2005). We are not aware of any treatment studies that have reported any evidence that treatments resulted in clinically significant changes in CBs. Without evidence of clinical significance (e.g., improved remission from severe maladaptive behaviors) we do not know if research participants continued to engage in severe maladaptive behaviors, even though they may have occurred less often, on average.

Psychosocial Treatments

Because the side effects of psychotropic medications create serious health concerns and the lack of strong empirical evidence that they effectively reduce CBs (Antonacci, Manual, & Davis, 2008; Matson, Fodstad, Rivet, & Rojahn, 2009; Matson & Neal, 2009; Oliver-Africano, Murphy, & Tyrer, 2009; P. Tyrer et al., 2008), it is important to identify effective psychosocial treatments for CBs in individuals with IDD in community settings. There is a vast literature on the effectiveness of applied behavior analysis (ABA) for individuals with IDD and CBs (Grey & Hastings, 2005; M. Harvey, Luiselli, & Wong, 2009; Hassiotis et al., 2011; Luiselli, 2009; Luyben, 2009; Neef, 2001; Neidert et al., 2010; Robertson et al., 2005). In particular, there are numerous single subject experimental studies supporting ABA with children (Borrero & Vollmer, 2006; Luce, Delquadri, & Hall, 1980; McGee & Ellis, 2000; Russo, Cataldo, & Cushing, 1981; Vaughan, Clarke, & Dunlap, 1997) and with adults in highly controlled environments (e.g., in hospitals and institutional settings; Frederiksen, Jenkins, Foy, & Eisler, 1976; Iwata, Smith, Mazaleski, & Lerman, 1994; Roscoe, Iwata, & Goh, 1998; Shore, Iwata, Vollmer, Lerman, & Zarcone, 1995). We searched several electronic journals and databases (e.g., PsycInfo and PubMed) and Internet search engines for relevant single subject experimental studies and randomized controlled trials evaluating psychosocial interventions for CBs in adults with IDD in outpatient community settings, but the only study of ABA we found was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that found support for ABA (Hassiotis et al., 2009). This apparent lack of research may reflect the exceptional challenges to implementing ABA with adults living in community residences, including the many sources of stimulus control and reinforcement of CBs; many fewer opportunities for outpatient treatment staff to control antecedents and consequences; and the reduced opportunities for outpatient treatment staff to observe low-frequency CBs (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1987; Grey & Hastings, 2005; Neef, 2001; Whitaker, 1993). Our search yielded only one other methodologically strong study evaluating changes in CBs, an RCT that found support for cognitive behavior therapy (CBT; Nezu et al., 1991). We found eight other studies (all RCTs), of which six did not measure CBs (e.g., only self-reports of anger intensity; Hagiliassis, Gulbenkoglu, Marco, Young, & Hudson, 2005; Rose, Dodd, & Rose, 2008; Rose, Loftus, Flint, & Carey, 2005; Rose, O'Brien, & Rose, 2009; Rose, West, & Clifford, 2000; Willner, Jones, Tams, & Green, 2002). McPhail and Chamove (1989) did not mention what type of measures were used in their study of relaxation or how their data were analyzed, and initial treatment gains were completely lost at the 3-month follow-up. Lindsay et al. (2004) reported significant treatment effects, yet substantial missing data and failure of randomization were limitations of this study. Most of these studies were vulnerable to bias by not assessing outcomes using blind raters and not analyzing the impact of missing data when follow-up data were available. Although the studies by Nezu et al. (1991) and Hassiotis et al. (2009) were methodologically strong and showed that CBT and ABA can effectively reduce CBs, it was not clear if the posttreatment scores indicate remission from severe maladaptive behaviors because no cutoff scores for the outcome measure were reported. It is possible that many individuals with IDD in those studies continued to engage in severe maladaptive behaviors, even though they occurred less often.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy

Because there is not yet sufficient evidence that existing interventions sufficiently improve severe CBs of adults with mild/moderate IDD who live in community-based settings, it is reasonable to consider exploring additional options for evidence-based interventions. Because numerous complex issues must be effectively treated in order to achieve significant long-term reductions in CBs in individuals with IDD, it is clear that a sophisticated and comprehensive evidence-based treatment is needed. Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) (Linehan, 1993a) is an one such treatment that is well suited for treating severe CBs because it incorporates the core strategies utilized in ABA and CBT approaches and the top therapy agenda is always to explicitly and thoroughly target severe CBs. DBT is an evidence-based, comprehensive, multimodal, cognitive behavioral treatment that was designed to treat long-standing, rigid, reinforced patterns of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral dysregulation and coexisting Axis 1 and Axis 2 diagnoses. Several randomized controlled trials (with non-IDD participants) have been completed highlighting the efficacy of DBT in reducing self-inflicted injury and days of hospitalization and improving therapy retention and global functioning for women with borderline personality disorder (BPD; e.g., Linehan et al., 2006; van den Bosch, Verheul, Schippers, & van den Brink, 2002; Verheul et al., 2003). DBT has been shown to effectively treat other populations with Axis I and Axis II diagnoses and severe dysregulation. Randomized controlled studies support the efficacy of DBT in treating substance abuse (Linehan et al., 2002; Linehan et al., 1999), eating disorders (Safer, Telch, & Agras, 2001; Telch, Agras, & Linehan, 2001), and depression in older adults (Lynch, Morse, Mendelson, & Robins, 2003).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy and Individuals With IDD

Several studies suggest that DBT is promising for individuals who have IDD and challenging behaviors. Dunn and Bolton (2004) published a case study describing the application of DBT with an individual who demonstrated challenging behaviors. Lew, Matta, Tripp-Tebo, and Watts (2006) reported pilot data that showed significant improvement for eight women who demonstrated challenging behaviors. Verhoeven (2010) published a case study that integrated DBT and the treatment of an individual with IDD and sexual offending issues. Sakdalan, Shaw and Collier (2010) completed a pilot study with a forensic sample of nine individuals with IDD and improvements across all measures were noted. This study seeks to expand the emerging evidence for DBT with this population by conducting a pilot study with a larger sample and more rigorous measurement of CBs to explore clinical significance.

DBT modified for individuals with IDD. DBT is a comprehensive treatment that integrates not only elements of CBT and ABA but also expands the spectrum of strategies to address broad-based, lifelong regulatory deficits. Beyond standard CBT, DBT includes mindfulness practice, dialectical strategies, case management supports, a suicide protocol, and offers a coping skills group (in addition to weekly individual therapy sessions; Linehan, 1993b). The treatment blends acceptance strategies (validation) and change strategies (e.g., behavioral strategies such as positive reinforcement, contingency management, and exposure) to simultaneously treat self-invalidation and reinforced patterns of escalating emotions, which are underlying factors associated with challenging behaviors.

Adapted skills training. The Skills System (Brown, 2011) is a modified emotion regulation skills curriculum designed for individuals with IDD. The Skills System is designed to build mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, emotional regulation, and distress tolerance capacities, as in standard DBT skills modules (Linehan, 1993b), but the adapted curriculum significantly modifies language and format to accommodate the specific learning and processing needs of the population. In light of the complex needs of individuals who have IDD and CBs, combined with the absence of clear data indicating an effective treatment for this population, the adaptation of DBT for people with IDD is justified. Offering long-term DBT in conjunction with the Skills System (DBT-SS) is justified to enable effective transitions to increasing levels of independence within residential and vocational settings.

METHODS

Participants

There were 40 participants in the study. Eighty-five percent were male (35 men and 5 women). Their ages ranged from 19 to 63 (M = 30.8, SD = 10.1), and their IQs ranged from 40 to 95 (full-scale IQ [FSIQ] M = 60.8, SD = 11.5). Table 1 lists the gender, age, FSIQ, challenging behaviors, and mental health diagnoses of each participant. Most of the sample (82.5%) had an IQ of 70 or below (intellectual disability), and 18% were diagnosed as having autism spectrum disorders. All participants had a history of severe problem behaviors and most (67%) had engaged in four or more of the behaviors during their lifetime (M = 4.2). The behaviors, number of participants engaging in these behaviors, and outcomes of behaviors are listed in Table 2. All but 2 participants (95%) had at least one Axis I disorder (Mdn = 2). As can be seen in Table 3, the most common disorders were mood disorders, anxiety disorders, sexual disorders (e.g., pedophilia), and BPD.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information, Types of Challenging Behaviors, and Diagnoses of Study Participants

| Sex | Age | FSIQ | Challenging behaviors | Diagnoses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 29 | 71 | Aggression, self-injury, stealing, hospital, arrests | Dementia-head trauma, personality disorder, NOS |

| 2 | Male | 21 | 64 | Aggression, stealing, hospital | Bipolar with psychotic features, anxiety disorder |

| 3 | Male | 29 | 63 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, substance abuse, stealing, hospital, arrests | Impulse control disorder, NOS; alcohol abuse, cannabis abuse |

| 4 | Male | 22 | 50 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing | Conduct disorder |

| 5 | Male | 22 | 56 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, hospital, arrests | Pervasive developmental disorder, conduct disorder, OCD Schizoaffective disorder, ADHD |

| 6 | Male | 21 | 80 | Self-injury, hospital | |

| 7 | Male | 37 | 57 | Aggression, fire setting | Intermittent explosive disorder |

| 8 | Male | 19 | 55 | Aggression, fire setting, hospital, arrests | Impulse control disorder, NOS, PTSD, borderline personality disorder |

| 9 | Male | 21 | 95 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, stealing, hospital, arrests Aggression, fire setting, self-injury, hospital | Asperger's disorder, anxiety disorder |

| 10 | Male | 24 | 64 | Impulse control disorder, NOS, OCD | |

| 11 | Male | 22 | 73 | Aggression, self-injury, hospital | Pervasive developmental disorder, Asperger's disorder, intermittent explosive disorder |

| 12 | Male | 40 | 40 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, stealing, arrests | Intermittent explosive disorder |

| 13 | Male | 22 | 73 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing, hospital | Pervasive developmental disorder, OCD, pedophilia, oppositional defiant disorder |

| 14 | Male | 39 | 48 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing, arrests | Pedophilia, voyeurism, exhibitionism |

| 15 | Male | 37 | 77 | Sexual offense, self-injury, hospital, arrests | Pedophilia |

| 16 | Male | 23 | 68 | Aggression, substance abuse, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital, arrests | Psychotic disorder, NOS, polysubstance abuse |

| 17 | Male | 22 | 50 | Aggression, sexual offense, self-injury, stealing | Conduct disorder, OCD, exhibitionism |

| 18 | Male | 27 | 60 | Aggression, substance abuse, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital | OCD, ADHD, borderline personality disorder |

| 19 | Female | 26 | 56 | Aggression, self-injury, stealing, hospital | PTSD, borderline personality disorder |

| 20 | Male | 21 | 60 | Sexual offense | Pedophilia |

| 21 | Male | 28 | 46 | Aggression, sexual offense | Intermittent explosive disorder, pedophilia |

| 22 | Female | 26 | 67 | Aggression, self-injury, stealing, arrests | |

| 23 | Female | 54 | 50 | Aggression, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital | Dysthymic disorder, borderline personality disorder |

| 24 | Female | 28 | 55 | Aggression, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital | Depression, anxiety disorder |

| 25 | Male | 29 | 65 | Aggression, fire setting, stealing, hospital | Anxiety, depression |

| 26 | Male | 54 | 49 | Sexual offense, self-injury, stealing, arrests | Anxiety, pedophilia |

| 27 | Male | 39 | 56 | Aggression, sexual offense, self-injury, hospital, arrests | Asperger's disorder, intermittent explosive disorder |

| 28 | Female | 36 | 60 | Aggression, substance abuse, self-injury, stealing, hospital | Bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, histrionic personality disorder |

| 29 | Male | 46 | 54 | Aggression, sexual offense, arrests | Depression, anxiety disorder |

| 30 | Male | 22 | 59 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing | Schizoaffective disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent defiant disorder |

| 31 | Male | 22 | 60 | Aggression, substance abuse, stealing | ADHD, Asperger's disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, alcohol abuse |

| 32 | Male | 20 | 61 | Aggression, sexual offense, substance abuse, hospital, arrests | Conduct disorder, ADHD, sexual abuse of a child, dysthymic disorder |

| 33 | Female | 52 | 60 | Aggression, self-injury, suicide attempts, hospital | Major depression with psychotic features, borderline personality disorder |

| 34 | Male | 23 | 63 | Aggression, sexual offense | Impulse control disorder, NOS, PTSD, ADD |

| 35 | Male | 34 | 60 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, substance abuse, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital, arrests | Impulse control disorder, NOS, sexual abuse of an adult, voyeurism |

| 36 | Male | 35 | 85 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing | Depression, frontal lobe syndrome |

| 37 | Male | 42 | 49 | Aggression, sexual offense, stealing, hospital, arrests | Pedophilia, personality disorder, NOS |

| 38 | Male | 44 | 49 | Aggression, sexual offense, self-injury, stealing | Impulse control disorder, NOS, depression |

| 39 | Male | 36 | 76 | Aggression, sexual offense, fire setting, self-injury, suicide attempts, stealing, hospital, arrests | Pedophilia, paraphilia, NOS |

| 40 | Male | 40 | 46 | Sexual offense, stealing, arrests | Conduct disorder, NOS |

Hospital = psychiatric hospitalization; NOS = not otherwise specified; OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

TABLE 2.

Lifetime History of Problem Behaviors and Outcomes (N = 40)

| Behaviors | % |

|---|---|

| Suicide attempts | 18 |

| Fire setting | 23 |

| Self-injury | 48 |

| Stealing | 65 |

| Aggression | 88 |

| Outcomes | |

| Arrests | 45 |

| Psychiatric hospitalization | 60 |

TABLE 3.

Current Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disorders (N = 40)

| Disorder | % |

|---|---|

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 5 |

| Psychotic disorder | 8 |

| Substance use disorder | 10 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention deficit disorder | 13 |

| Conduct disorder | 13 |

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 18 |

| Impulse control disorder NOS | 15 |

| Borderline personality disorder | 20 |

| Mood disorder | 25 |

| Anxiety disorder | 35 |

| Sexual disorders (abuse of others) | 38 |

Note. For diagnostic categories, the percentage refers to how many participants had at least one of the disorders. NOS = not otherwise specified.

Most of the participants utilized expensive services in the 2 years prior to DBT-SS. Eleven (28%) were inpatients in a psychiatric hospital, 11 (28%) were in out-of-state residential treatment (OSRT), and 5 (13%) were in jail or other locked forensic settings. Ten of the 11 clients in OSRT were in that setting for the two full years, and one was in OSRT for 16 months. Three of the clients were in a psychiatric hospital for the full two years, and the total number of psychiatric inpatient days for the other 7 clients was 315, 28, 16, 16, 12, 7, 7. One client was hospitalized prior to and following admission to DBT-SS during the time frame of this study, but it was not possible to get the exact number of days.

Procedure

All participants received comprehensive treatment at Justice Resource Institute-Integrated Clinical Services (ICS). Most of the participants lived in community residences with 24-hr supervision, with the exception of 2 individuals who resided in more individualized settings that provide support as needed. Residential supports are provided by private provider agencies, which are funded by the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals. This study was approved and monitored by the Justice Resource Institute Institutional Review Board to protect the rights of the human participants.

Once potential participants were clearly identified by their primary therapists at ICS, participants were invited to sign informed consent forms for the study. Written informed consent procedures were adapted by the research team to meet the developmental needs of participants and completed with the participant and his or her individual therapist. Next, the primary therapist contacted the support providers by phone, e-mail, and/or in person to request demographic and behavioral data.

Program Description and Interventions

Treatment at ICS model consists of 1 hr of individual DBT per week and 1 hr of Skills System (SS) group skills training (DBT-SS). Clients with histories of sexual offending behaviors receive an additional hour of group per week to specifically address those clinical issues in addition to the standard DBT-SS. The DBT-SS individual therapy was adherent to the standard DBT structure of treatment. No accommodations were necessary related to the DBT (stages of treatment, hierarchy of targets, assumptions, consultation agreements, phone calls, and consultation team) described by Linehan (1993a). Modifications were necessary to the DBT self-monitoring procedures. Clients who have difficulty reading and writing worked with their therapists to create shift summary forms that were completed by support staff, documenting adaptive and problematic target behaviors to facilitate behavior analysis. Adapted diary cards were integrated when possible; these forms were individualized, simplified, and used pictures to represent targets and skills. Standard DBT dialectical strategies, validation, contingency management, exposure, and DBT stylistic strategies are used. Simplification, shaping, and task analysis are often necessary when doing these strategies as well as when doing problem solving, cognitive modification, contingency management, and case management with this population to be assured the individuals understand each step within complex, multistep skills.

In addition to in-session use of behavioral strategies typical in standard DBT (such as contingency management, extinction, and exposure), formal behavioral treatment plans are used with this population; these often include the use of tangible rewards for adaptive behaviors and systematic contingency plans to address problematic behaviors. To further accommodate the learning needs of the clients, a behavioral categorization system is used in to label increasing levels of intensity of maladaptive behaviors. Through the process of behavioral analysis the client and therapist classify problematic behaviors as Red Flags (low intensity), Dangerous Situations (medium), and Lapse behaviors (high) to clarify phases of the person's escalating chains of behavior. This framework improves self-awareness and facilitates early intervention with more adaptive self-regulation alternatives.

The standard DBT skills modules are designed for average-intelligence learners; the Skills System is a simplified DBT-based coping skills curriculum that extracts key DBT skills concepts, simplifies the language, and provides tools that guide the participant through choosing the most effective skills to manage his or her current situation given his or her level of emotional arousal. Additionally, DBT-SS therapists promote skills generalization by frequently consulting with the multidisciplinary team of residential agencies, vocational support teams, psychologists, and medical staff (including the treating psychiatrist). True to the standard DBT consultation to the client strategy, DBT-SS therapists strive to balance intervening with other providers for the client with guiding the client to effectively deal directly with other providers. Support staff are offered monthly Skills System training to help them function as Skills System coaches. Participation in DBT-SS generally lasts several years.

The ICS clinical team was comprised of the director (who is a licensed, independent clinical social worker and DBT trainer for Behavioral Tech, LLC) and two master's level clinicians, all of whom were intensively trained in DBT through Behavioral Tech, LLC. For the duration of the study, the clinicians received weekly individual supervision with the program director and participated in weekly consultation team following standard DBT protocols (Linehan, 1993a). DBT experts employed at Behavioral Tech, LLC, rated a session of the program director and found her session to be in adherence with DBT.

Sampling Procedures

All individuals who were currently receiving services at Justice Resource Institute-Integrated Clinical Services (ICS) at the start of the study were participants in this research. All individuals who receive services at ICS have been diagnosed with a developmental disability by the Rhode Island Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals and present with a variety of CBs. These individuals were sent to ICS because their CBs did not improve in traditional mental health centers.

Measures

Demographic data (gender, age, IQ, history of behavioral problems, psychiatric diagnoses, placement history, and length of time participating in treatment) and behavioral data were culled from the records of the residential provider agencies and ICS clinical records. For most ICS participants the residential team, the psychologist, the ICS primary therapist, and the client developed behavioral treatment plans that categorize the client's behaviors in three ascending intensity categories: Red Flags, Dangerous Situations, and Lapse behaviors. “Red Flags” included low-grade behaviors, such as yelling or swearing, that could precede more serious behaviors. “Dangerous Situations” were ones that escalated beyond verbal outburst to include rough handling of objects, slamming doors, and verbal and/or physical threats of violence (e.g., moving closer to a potential victim). “Lapses” were violent and illegal behaviors, such as aggression and self-injury. The categorization of the individual's behavior reflects his or her unique patterns of challenging behavior. For example, if one participant spoke to a child in the community it might not be a risk for that individual, whereas for an individual with a history of sexually abusing children it might be categorized as a Dangerous Situation because he or she approached a potential victim.

During treatment ongoing CBs were documented in incident reports. For participants with behavioral treatment plans, the CBs were sorted into the three intensity categories by the support staff who directly observed the behaviors. Seven participants lacked behavioral treatment plans, therefore the CBs documented in the incident reports had to be later categorized by the ICS team (described earlier) into the three intensity categories. The following coding rules were used: (a) if the participant demonstrated a cluster of multiple CBs within a short time frame (e.g., often less than 15 min), it was coded as one incident, at the highest intensity level; (b) incidents that clearly progressed over a longer time frame (e.g., longer than 30 min) from Red Flags, to Dangerous Situations, and to Lapse were coded as separate incidents. In the event of unclear or missing information, individual therapy notes of these 7 participants were utilized to fill in gaps or clarify these data; these documents provide detailed behavioral analysis information related to behavior problems. Interrater reliability of the coding was not evaluated.

Missing Data

The average participant had data through the 82nd month of treatment (M = 6.9 years, SD = 3.5, Mdn = 6.9) and provided 79 months of data. Five participants (15%) were missing between 16 and 40 months of data at the start of treatment. Their first data were for 17, 21, 24, 35, and 41 months, respectively, since the start of their treatment. These missing data were not recoverable because the agencies only kept records for 7 years. These 5 participants provided 115, 136, 52, 94, and 49 months of data, respectively. All data were retained in all analyses. Three of the 6 did not have Dangerous Situations data for a portion of treatment. In these cases the behavioral treatment plans collapsed the three categories of data into two target categories for a period of time and incident reports were not available to recode the incidents due to destruction of files after 7 years. One of the 6 participants with missing data did not have Red Flag behaviors coded because the support team did not target low-risk behaviors and incident reports were not available to recode the data.

Statistical Methods

Our primary method for analyzing the repeated measures data was random regression modeling (HLM; also known as hierarchical linear models, multilevel linear models, and mixed-effects models; Bryk & Raudenbush, 1992; Longford, 1993). The primary analysis variables were the number of problem behaviors per month, and the analyses were based on computations of rates of change in behaviors (i.e., the slopes) from month to month across the years of study participation. Because all the primary outcome variables had highly skewed nonnormal distributions, they were recoded into discrete ordinal levels and analyzed with HLM for ordinal data (Hedeker & Mermelstein, 2000; Scott, Goldberg, & Mayo, 1997). Red Flag behaviors were recoded into four ordinal levels (the highest level was five or more episodes per month), Dangerous Situations were recoded into four ordinal levels (the highest level was four or more episodes), and Lapses were recoded into three ordinal levels (the highest level was two or more episodes). For each, zero and one episodes per month were coded as the two lowest levels. A piecewise HLM was also tested to examine if improvement was faster (i.e., larger slopes) within the 1st year than subsequent years. For these piecewise analyses the time variable was partitioned into two time variables, and both were entered into a single HLM analysis (cf. Keller et al., 2000).

To assess the potential impact of missing data (i.e., ignorable vs. informative missing data), a pattern-mixture analysis was implemented with two-tailed tests (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). We defined one pattern using a binary status variable, reflecting whether data were available at the very start of treatment, which was entered as a predictor in the random regression models (RRMs). To determine if the slope estimates depend on this missing data status, a two-way interaction of missing status by time was included in the HLM models. We also examined whether the total number of months of data was associated with the slope estimates.

RESULTS

Primary Outcomes

Many problem behaviors occurred while participants were in treatment. Descriptive data clearly indicate that there were large reductions in problem behaviors during treatment (see Table 4), and the reductions were statistically significant for Red Flag behaviors (t = 4.2, df = 3018, p < .001), Dangerous Situations (t = 3.066, df = 2867, p = .003), and Lapses (t = 5.1, df = 3111, p < .001). Figure 1 shows the observed outcome data during the first 4 years of treatment suggest that much of the improvement for most behaviors occurred during the 1st year but that the most serious behaviors, Lapses, improved more slowly.

TABLE 4.

Behavior Outcomes During the First 4 Years of Treatment

| Observed data | Year 1 (N = 35) | Year 2 (N = 40) | Year 3 (N = 40) | Year 4 (N = 40) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Red Flags | ||||

| M (SD) | 55.2 (67.3) | 32.5 (36.6) | 31.2 (39.1) | 26.8 (34.7) |

| Median | 17.5 | 20.5 | 15.5 | 9.5 |

| Dangerous Situations | ||||

| M (SD) | 59.3 (114.1) | 29.5 (55.9) | 29.0 (56.4) | 25.0 (50.4) |

| Median | 13.5 | 9.5 | 6.5 | 6.0 |

| Lapses | ||||

| M (SD) | 20.5 (29.1) | 16.5 (28.9) | 12.2 (18.2) | 11.4 (21.2) |

| Median | 8.5 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 3.0 |

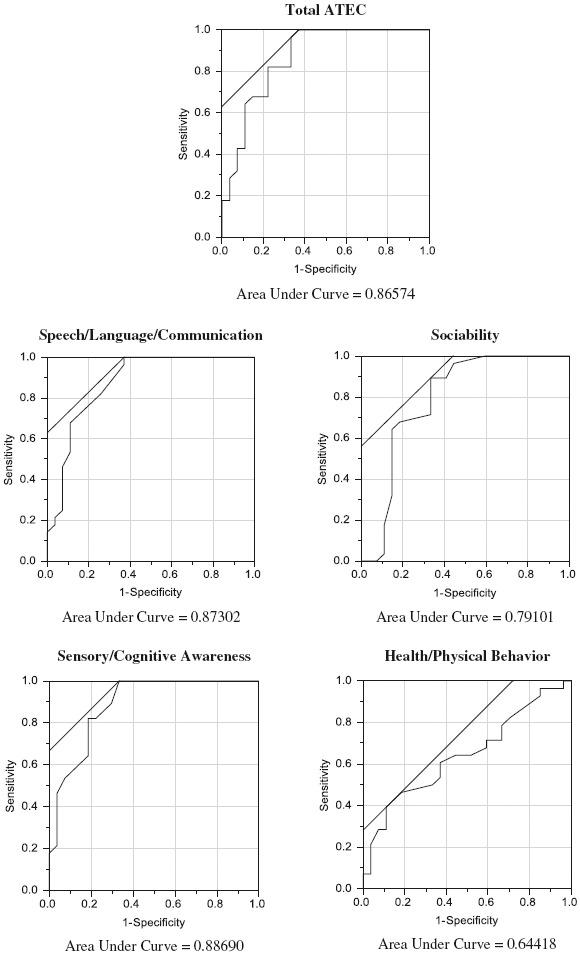

FIGURE 1.

Mean number of Dangerous Situations, Red Flags, and Lapses within 4-month intervals across 4 years (N = 26). Note. This graph includes only the 26 participants with complete data for 4 years.

A piecewise HLM analysis was done to compare the rate of change in problem behaviors across the 1st year compared with later years. The HLM coefficients from this analysis suggest that larger reductions in problem behaviors occurred in the 1st year of treatment than in subsequent years and that the reductions were maintained into the later years; however, the statistical significance of the difference in slopes was not robust. The ordinal piecewise HLM analysis on Lapses yielded a slope coefficient of 0.049 for the 1st year and 0.015 for subsequent years, indicating the decrease in Lapses in the 1st year is about 3 times as large as the decrease in Lapses in subsequent years (chi-square = 3.9, df = 1, p = .047). However, the difference in slopes did not remain statistically significant when using robust standard errors (chi-square = 1.8, df = 1, p = .174).

The coefficient estimates from standard linear HLM were used to illustrate the magnitude of the differences in the rate of change. Although the p values from linear HLM do not reflect the true Type I error rate, the coefficients are much more easily interpreted than the odds ratio coefficients generated from ordinal HLM analyses. Linear HLM estimated that much larger reductions in Lapses occurred in the 1st year than in subsequent years. Linear HLM estimated 1.7 Lapses during the 1st month and that in the 13th month of treatment the average participant had 1.0 Lapses per month (a reduction of 0.7 monthly Lapses, 1.7 − 1.0 = 0.7, across the 1st year, which is equivalent to a reduction of 8.4 total Lapses, 0.7 × 12 months = 8.4, across the 1st year), whereas HLM estimated 0.8 total Lapses in the 25th month of treatment and a similar reduction in subsequent years (a reduction of 0.2 monthly Lapses, 1.0 − 0.8 = 0.2, across the 2nd year, which is equivalent to a reduction of about 2.4 total Lapses, 0.2 × 12 months = 2.4, per year for each subsequent year). Thus, at the end of the 4th year of treatment, the average participant had 0.4 Lapses per month, which is a 76% reduction in Lapses compared with the 1st month of treatment (1.7 Lapses per month). These estimates derived from HLM are likely to be more accurate than the raw descriptive statistics because HLM adjusts for missing data (e.g., people who leave the program early due to remarkable improvement).

In the 2 years prior to DBT-SS, 28 of the 40 clients (70%) were in OSRT, a psychiatric hospital, or in a jail/forensic setting. The exact number of days was not available for 1 client. The 27 clients with complete data spent an average of 228 total days per year in these settings. In contrast, during the first 2 years of DBT-SS only 2 of the 40 clients were in any of these settings. One client was in a psychiatric hospital for 20 days and the other client (noted earlier) was hospitalized, but it was not possible to get the exact number of days. Of the 27 clients with complete data on days in OSRT, a psychiatric hospital, or a forensic setting prior to DBT-SS, the average client spent 228 fewer days per year in these settings during DBT-SS.

Predictors of Treatment Response

The following eight variables were plausible treatment moderators and therefore were tested to see if they predict the amount of improvement in serious CBs (Lapses). Given that DBT is an evidence-based treatment for overt problem behaviors associated with BPD, we predicted more improvement among clients with externalizing disorders (conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder [IED] or impulse control disorder, and aggressive behaviors), suicidal or self-injurious behaviors, or BPD. We predicted less improvement among clients with sexual offending behaviors because the treatment literature suggests these behaviors are very resistant to change. We predicted that amount of improvement would be comparable for participants of different ages and intellectual functioning (FSIQ).

Predictors of better outcomes were the presence of BPD, self-injury, and aggression, each of which predicted larger reductions in Lapses (see Table 5). These variables were highly correlated. All 8 BPD participants had aggressive behavior, and 6 had self-injury. When BPD, self-injury, and aggression and number of Lapses in the first 4 months of treatment were entered into a single HLM equation, each had unique variance in predicting larger reductions in Lapses. That is, the presence of BPD independently predicts larger improvement regardless of whether the participant has self-injury or aggression.

TABLE 5.

Predictors of Treatment Response (N = 40)

| Normal SE | Robust SE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variable | Covariate | t (df) | p value | t (df) | p value |

| FSIQ | No | 1.541 (3109) | .123 | 0.818 (3109) | .414 |

| Age | Yes | −2.473 (2680) | .014 | −1.144 (2680) | .253 |

| BPD | Yes | 4.140 (2680) | .001 | 2.751 (2680) | .006 |

| Self-injury | Yes | 4.717 (2680) | .001 | 1.954 (2680) | .050 |

| Aggression | Yes | 2.292 (2680) | .022 | 2.444 (2680) | .015 |

| Conduct disorder | No | 2.097 (3109) | .036 | 1.114 (3109) | .266 |

| IED | Yes | −5.166 (2680) | .001 | −2.199 (2680) | .028 |

| Sex offender | Yes | −2.723 (2680) | .007 | −1.101 (2680) | .271 |

Note. The covariate variable, the number of Lapses in the first 4 months of treatment, was put into the equation when necessary to clarify significant correlations. Thirty-five participants were in the covariate analyses because five participants did not have data for the first treatment year. Normal SE = normal standard errors used; Robust SE = robust standard errors used; FSIQ = full scale IQ; BPD = borderline personality disorder; IED = intermittent explosive disorder.

An additional analysis was conducted to examine if the effect of any of these variables could be due to participants with these problems simply having more Lapses at the start of treatment and thus more room for improvement. However, including number of Lapses in the first 4 months of treatment as a covariate showed that the strength of the relationship between these variables and larger reductions in Lapses did not change after controlling for initial number of Lapses. Younger age was significantly correlated with larger reductions in Lapses (t = −2.642, df = 3109, p = .009). However, the difference in slopes did not remain statistically significant when using robust standard errors (t = −1.435, df = 3109, p = .151). The HLM coefficients indicated that participants who were age 20 had twice the reduction as participants who were age 45. When age was added to the same HLM equation with BPD, nonsuicidal self-injury, and aggression, the effect for aggression became statistically nonsignificant implying that aggression predicted larger reductions in Lapse behaviors because aggressive participants were younger, not because aggression per se makes someone a good match for DBT.

The only reliable predictor of a slower progress was the presence of IED. Participants with IED had smaller reductions in Lapses than participants without the disorder. Including number of Lapses in the first 4 months of treatment as a covariate showed that the strength of the relationship between the presence of IED and smaller reductions in Lapses did not change after controlling for initial number of Lapses. The presence of a history of sexual offending was also associated with slower progress in treatment, but the effect did not remain statistically significant when using robust standard errors so it could simply be a spurious association. None of the 8 BPD participants had IED and only 1 had a history of sexual offending. Finally, we tested if reduction in Lapses generalized across levels of intellectual impairment severity. Participants with lower FSIQ scores had the largest reduction in Lapses, but the association was not statistically significant.

Analysis of the Impact of Missing Data Patterns

We examined the effects of differential missing data on each of our major outcome variables and found no evidence that the findings were biased by these differences. The 5 participants (15%) who were missing the first 16–40 months of data (16, 20, 23, 34, 40 months) were all retained in all analyses because the 5 participants were largely similar to the other 34 participants: FSIQ (M = 63.7 vs. 60.2, p = .507, respectively); age (35.7 vs. 30.0, p = .140). However, a much higher percentage of the 5 participants had a history of sexual offending (100% vs. 53%; p = .064). Although inclusion of the 5 participants in the analyses did reduce the effect size of the reduction in problem behaviors, it did not eliminate the statistical significance of any finding.

DISCUSSION

We hypothesized that dialectical behavior individual therapy and the Skills System (DBT-SS) would help individuals with intellectual disabilities reduce severe CBs by teaching them self-control. As expected, there were large statistically and clinically significant reductions in all three behavior categories in the 1st year and the improvement was maintained over 4 years. Most of the improvement in the less severe behaviors occurred in the 1st year, but the more severe behaviors improved more gradually across the first 4 years. Statistical analyses estimated the there was a 76% reduction in serious behaviors (e.g., fewer violent, self-injurious, and illegal behaviors) across 4 years of DBT-SS.

Our results suggest that DBT-SS may be more helpful for younger participants and participants with BPD, self-injury, or aggression, as the presence of these characteristics was associated with larger reductions in severe challenging behaviors. Given that DBT is an evidence-based treatment for BPD, one would expect that these clients would improve more rapidly in treatment. Individuals without IED improved more quickly than individuals with IED. Younger participants with BPD, self-injury, or aggression and who do not have IED may be a particularly good match for DBT-SS, but further research is needed to confirm for whom DBT-SS will likely yield better improvement than other treatments. Understanding predictors of poor outcome can also facilitate efforts to develop more effective interventions to address the specific needs of certain subgroups of clients. The analysis of predictors of improvement suggests that improvement in CBs was comparable for individuals of varying levels of intellectual disability (FSIQ), which suggests that DBT may be as helpful for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) as for individuals with developmental disabilities (DD) without ID.

Because no comparison group was used in this study, we cannot conclude confidently that DBT-SS is responsible for these improvements. These data also do not verify that participants improved in emotion regulation or self-control skills or that these changes were responsible for improvements in challenging behaviors. The significant reductions in CBs combined with the heavy focus on skills training in DBT-SS leads us to believe that DBT-SS improved the coping abilities of participants and thereby improved their autonomy, positive life experiences, and relationships, but more research is needed to verify the process and outcomes for DBT-SS. However, it is unknown which of the many DBT-SS components were the most helpful. In addition, the treatment fidelity was not verified. Further research is also needed to clarify how much DBT-SS is needed to achieve the magnitude of treatment effect observed in this study. It is currently not clear how much of the continuing improvement in challenging behaviors in the later years was due to what participants learned in DBT-SS during the 1st year of treatment or if ongoing intensive DBT-SS was necessary for multiple years. The generalizability of these treatment effects beyond this clinical setting and specific sample is also unknown. This pilot study warrants further studies with rigorous methodologies to remedy these limitations.

Individuals with IDD and CBs have complex needs that likely require intensive and comprehensive treatment over an extended period of time. Although such treatments are expensive, they will likely benefit these consumers, support agencies, and the general public. The usual management of these high-risk individuals often involves multiple systems of care, multiple treatment modalities, high staff-to-client ratios, psychiatric hospitalizations, and incarcerations and also involves considerable expense. DBT-SS could result in cost savings through reductions in the utilization of these types of services. Clients in DBT-SS showed dramatic reductions in incarceration, psychiatric hospitalization, and OSRT. Among the clients who were in these settings before DBT-SS (n = 27), the time spent in these settings decreased from 228 days per year to almost zero on average. Total psychiatric multidisciplinary treatment costs for the average client living in a community residence receiving DBT-SS services is estimated at $482 per day. The most expensive residential rate of for a participant in the study was $526 per day. Of these totals, the average cost of DBT-SS therapy services at ICS was $180.81 per week. This weekly rate included 1 hr of DBT individual therapy, 1 hr of skills group, an additional hour of sexual offender group for individual with those issues, unlimited staff participation in ICS training, ICS staff attendance at monthly team meetings, supplied Skills System Handout Notebooks and Skills System CDs for the clients and direct support professionals, skills coaching via phone with the client, and phone consultation with the team as needed.

We estimated cost savings for the clients in this study by comparing our costs to the cost of psychiatric hospitalization according to the Hospital Association of Rhode Island (2007; published on the Internet by Rhode Island Price Point System http://www.ripricepoint.org). In 2006, the average cost for a psychiatric hospitalization in Rhode Island was $2,637 per day for a person who has an ID/DD (the least expensive hospital costs about $2,105 per day). Thus, we estimate that the average DBT-SS client costs $667,270 per year (228 days × $2,637 + 137days × $482) before starting DBT-SS and costs $175,930 per year during DBT-SS at ICS (365 days × $482 = $175,930)—a savings of $491,340 per client per year.

There are clear benefits to enabling clients to move from locked settings to community residences. This adapted DBT model utilizing the Skills System is designed to improve the individual's core emotional, cognitive, and behavioral regulation capacities that are foundational to gaining increased levels of independence. Effectively addressing these lifelong severe problem behaviors appears to require long-term, comprehensive clinical support.

CONCLUSION

Although these pilot study data do not provide conclusive evidence for the effectiveness of DBT-SS with this population, these preliminary findings merit further studies with more rigorous methodologies. The DBT-SS model is designed to treat emotional dysregulation within a framework that accommodates the complex needs of individuals with cognitive impairment who demonstrate chronic patterns of CBs. This long-term, comprehensive treatment may enhance core self-regulation skills that are required for increasing independence and mobilizing effective self-determination.

REFERENCES

- Antonacci D. J., Manual C., Davis E. Diagnosis and treatment of aggression in individuals with developmental disabilities. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2008;79:225–247. doi: 10.1007/s11126-008-9080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer D. M., Wolf M. M., Risley T. R. Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20:313–327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson B. A., Rice C. J., Miranti S. V. Effects of anger management training with mentally retarded adults in group treatment. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:728–729. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero C. S., Vollmer T. R. Experimental analysis and treatment of multiply controlled problem behavior: A systematic replication and extension. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2006;39(3):375–379. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2006.170-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. The Skills System instructor's guide: An emotion regulation skills curriculum for all learning abilities. Bloomington, IN: IUniverse; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk A. S., Raudenbush S. W. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Carr E. G., Carlson J. I. Reduction of severe behavior problems in the community using a multicomponent treatment approach. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:157–172. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker A. G., Mercier C., Allaire J. F., Roy M. E. Profiles and correlates of aggressive behaviour among adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2007;51(10):786–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2007.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B. D., Bolton W. The impact of borderline personality traits on challenging behavior: Implications for learning disabilities services. The British Journal of Forensic Practice. 2004;6(4):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson E., Kiernan C., Alborz A., Reeves D., Mason H., Swarbrick R., Hatton C. The prevalence of challenging behaviors: A total population study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2001;22:77–93. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen L. W., Jenkins J. O., Foy D. W., Eisler R. M. Social-skills training to modify abusive verbal outbursts in adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1976;9:117–125. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1976.9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey I., Hastings R. P. Evidence-based practices in intellectual disability and behavior disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2005;18:469–475. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000179482.54767.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey I., Pollard J., McClean B., MacAuley N., Hastings R. Prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses and challenging behaviors in a community-based population of adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2010;3:210–222. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson C., Ojehagen A., Hansson L., Sandlund M., Nystrom M., Glad J., Fredriksson M. Effects of psychosocial interventions for people with intellectual disabilities and mental health problems. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19(3):281–290. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiliassis N., Gulbenkoglu H., Marco M. D., Young S., Hudson A. The anger management project: A group intervention for anger in people with physical and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2005;30(2):86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey M., Luiselli J. K., Wong S. E. Application of applied behavior analysis to mental health issues. Psychological Services. 2009;6(3):212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey S. T., Boer D., Meyer L. H., Evans I. M. Updating a meta-analysis of intervention research with challenging behavior: Treatment validity and standards of practice. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;34:67–80. doi: 10.1080/13668250802690922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis A., Canagasabey A., Robotham D., Marston L., Romeo R., King M. Applied behavior analysis and standard treatment in intellectual disability: 2-year outcomes. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;198:490–491. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.076646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis A., Robotham M. A., Canagasabey A., Romeo R., Langridge D., Blizard R., King M. Randomized, single-blind, controlled trial of a specialist behavior therapy team for challenging behavior in adults with intellectual disabilities. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166(11):1278–1285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08111747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassiotis A., Sturmey P. Randomized controlled trials in intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviors: Current practice and future challenges. European Psychiatric Review. 2010;23(2):39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D., Gibbons R. D. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal studies. Psychological Methods. 1997;2(64):78. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D., Mermelstein R. J. Analysis of longitudinal substance use outcomes using ordinal random-effects regression models. Addiction. 2000;95(4):S381–S394. doi: 10.1080/09652140020004296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert M., Maes B., Onghena P. A meta-analysis of intervention effects on challenging behavior among persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2010;54(7):634–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital Association of Rhode Island. Rhode Island PricePoint System. 2007. Retrieved from www.ripricepoint.org.

- Iwata B. A., Smith R. G., Mazaleski J. L., Lerman D. C. Reemergence of extinction of self-injurious behavior during stimulus (instructional) fading. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:307–316. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen C. G. C., Schuengel C., Stolk J. Understanding challenging behavior in people with severe and profound intellectually disability: A stress-attachment model. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2002;46(6):445–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan M., Dillenburger K. When all you have is a hammer…: RCTs and hegemony in science. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Keller M. B., McCullough J. P., Klein D. N., Arnow B., Dunner D. L., Gelenberg A. J., Zajecka J. A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(20):1462–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew M., Matta C., Tripp-Tebo C., Watts D. DBT for individuals with intellectual disabilities: A program description. Mental Health Aspects of Developmental Disabilities. 2006;9(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay W. R., Allan R., Parry C., MacLeod F., Cottrell J., Overend H., Smith A. Anger and aggression in people with intellectual disabilities: Treatment and follow-up of consecutive referrals and waitlist comparison. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2004;11:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M. Cognitive behavioral treatment for borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993a. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M. Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993b. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M., Comtois K., Murray A., Brown M., Gallop R., Heard H., Lindenboim N. Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(7):757–766. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.7.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M., Dimeff L. A., Reynolds S. K., Comtois K. A., Welch S. S., Heagerty P., Kivlahan D. R. Dialectical behavior therapy versus comprehensive validation plus 12-step for the treatment of opioid dependent women meeting criteria for borderline personality disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2002;67(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M., Schmidt H., Dimeff L. A., Craft J. C., Kanter J., Comtois K. A. Dialectical behavior therapy for patients with borderline personality disorder and drug dependence. American Journal on Addiction. 1999;8(4):279–292. doi: 10.1080/105504999305686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longford N. T. Random coefficient models. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Luce S. C., Delquadri J., Hall R. V. Contingent exercise: A mild but powerful procedure for suppressing inappropriate verbal and aggressive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1980;13:583–594. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1980.13-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luiselli J. K. Behavior support of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Contemporary research applications. Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2009;21:441–442. [Google Scholar]

- Luyben P. D. Applied behavior analysis: Understanding and changing behavior in the community. A representative review. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2009;37:230–253. doi: 10.1080/10852350902975884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch T. R., Morse J. Q., Mendelson T., Robins C. J. Dialectical behavior therapy for depressed older adults: A randomized pilot study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):33–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson J. L., Fodstad J. C., Rivet T. T., Rojahn J. Behavioral and psychiatric differences in medication side effects in adults with severe intellectual disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2009;2:261–278. [Google Scholar]

- Matson J. L., Neal D. Psychotropic medication use for challenging behaviors in persons with intellectual disabilities: An overview. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2009;30:572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClure K. S., Halpern J., Wolper P. A., Donahue J. J. Emotion regulation and intellectual disability. Journal on Developmental Disabilities. 2009;15:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- McGee S. K., Ellis J. Extinction effects during the assessment of multiple problem behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:313–316. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhail C. H., Chamove A. S. Relaxation reduces disruption in mentally handicapped adults. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research. 1989;33:399–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1989.tb01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neef N. A. The past and future of behavior analysis in developmental disabilities: When good news is bad and bad news is good. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2001;2:336–340. Retrieved from http://www.behavior-analyst-today.net/section2.html. [Google Scholar]

- Neidert P., Dozier C., Iwata B., Hafen M. Behavior analysis in intellectual and developmental disabilities. Psychological Services. 2010;7:103–113. [Google Scholar]

- Nezu C. M., Nezu A. M., Arean P. Assertiveness and problem-solving training for mildly mentally retarded persons with dual diagnoses. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1991;12:371–386. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(91)90033-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Africano P., Murphy D., Tyrer P. Aggressive behavior in adults with intellectual disability. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(1):903–913. doi: 10.2165/11310930-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout H. T., Nowak-Drabik K. M. Psychotherapy with persons who have mental retardation: An evaluation of effectiveness. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2003;108(2):82–93. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2003)108<0082:PWPWHM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S., Rojahn J. Joint occurrence of depression and aggression in children and adults with mental retardation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1993;37:287–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1993.tb01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J., Ererson E., Pinkney L., Caerar E., Felce D., Meek A., Hallam A. Treatment and management of challenging behaviors in congregate and noncongregate community-based supported accommodation. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(1):63–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roscoe E. M., Iwata B. A., Goh H. L. A comparison of noncontingent reinforcement and sensory extinction as treatment for self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:635–646. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J., Dodd L., Rose N. Individual cognitive-behavioral intervention for anger. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2008;1:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Rose J., Loftus M., Flint B., Carey L. Factors associated with the efficacy of a group intervention for anger in people with intellectual disabilities. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:305–317. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose J., O'Brien A., Rose D. Group and individual cognitive behavioral interventions for anger. Advances in Mental Health for Learning Disabilities. 2009;3:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rose J., West C., Clifford D. Group interventions for anger in people with intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2000;21:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(00)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo D. C., Cataldo M. F., Cushing P. J. Compliance training and behavioral covariation in the treatment of multiple problem behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:209–222. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer D. L., Telch C. F., Agras W. S. Dialectical behavior therapy for bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):632–634. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakdalan J. A., Shaw J., Collier V. Staying in the here-and-now: A pilot study on the use of dialectical behavior therapy group skills training for forensic clients with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities. 2010;54(6):568–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott S. C., Goldberg M. S., Mayo N. E. Statistical assessment of ordinal outcomes in comparative studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore B. A., Iwata B. A., Vollmer T. R., Lerman D. C., Zarcone J. R. Pyramidal staff training in the extension of treatment for severe behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:323–332. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch C. F., Agras W. S., Linehan M. M. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69(6):1061–1065. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer F., McGrother C. W., Thorp C. F., Donaldson M., Bhaumik S., Watson J. M., Hollin C. Physical aggression towards others in adults with learning disabilities: Prevalence and associated factors. Journal of Disabilities Research. 2006;50:295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrer P., Oliver-Africano P. C., Ahmed Z., Bouras N., Cooray S., Deb S., Crawford M. Risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the treatment of aggressive challenging behavior in patients with intellectual disability: A randomized controlled trial. The Lancet. 2008;371:57–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60072-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bosch L. M. C., Verheul R., Schippers G. M., van den Brink W. Dialectical behavior therapy of borderline patients with and without substance use problems: Implementation and long-term effects. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27(6):911–923. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00293-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan B. J., Clarke S., Dunlap G. Assessment-based intervention for severe behavior problems in natural family contexts. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:713–716. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verheul R., van den Bosch L. M. C., Koeter M. W. J., de Ridder M. A. J., Stijnen T., van den Brink W. Dialectical behaviour therapy for women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomized clinical trial in The Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;182:135–140. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven M. Journeying to wise mind: Dialectical behavior therapy and offenders with an intellectual disability. In: Craig A., Lindsay W. R., Browne K. D., editors. Assessment and treatment of sexual offenders with intellectual disabilities: A handbook. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 2010. pp. 317–340. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker S. The reduction of aggression in people with learning difficulties: A review of psychological methods. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993;29:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1993.tb01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitman T. L. Self-regulation and mental retardation. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1990;94(4):347–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for people with learning disabilities: A critical overview. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49(1):73–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P., Jones J., Tams R., Green G. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioural anger management group for adults with learning disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2002;15:224–235. [Google Scholar]