Abstract

Recent clinical studies have spurred rigorous debate about the benefits of hormone therapy (HT) for postmenopausal women. Controversy first emerged based on a sharp increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease in participants of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) studies, suggesting that decades of empirical research in animal models was not necessarily applicable to humans. However, a reexamination of the data from the WHI studies suggests that the timing of HT might be a critical factor and that advanced age and/or length of estrogen deprivation might alter the body's ability to respond to estrogens. Dichotomous estrogenic effects are mediated primarily by the actions of two high-affinity estrogen receptors alpha and beta (ERα & ERβ). The expression of the ERs can be overlapping or distinct, dependent upon brain region, sex, age, and exposure to hormone, and, during the time of menopause, there may be changes in receptor expression profiles, post-translational modifications, and protein:protein interactions that could lead to a completely different environment for E2 to exert its effects. In this review, factors affecting estrogen-signaling processes will be discussed with particular attention paid to the expression and transcriptional actions of ERβ in brain regions that regulate cognition and affect.

1. Introduction

According to the CDC (2008), the average lifespan for women in the USA is ~81 years of age. While the average lifespan has been steadily increasing over the past century (~48 years in 1900), the average age at which reproductive senescence, menopause, occurs has remained relatively constant between 45–55 years of age [1, 2]. Including the prepubescent years, this leaves women living about half of their lives without high levels of circulating ovarian hormones. The two primary ovarian hormones are 17β-estradiol (E2) and progesterone, both of which are required for female reproduction. Many positive anecdotal experiences are reported during times in the reproductive cycle when E2 is high, sparking further investigation into the role of E2 in various nonreproductive processes, including those pertaining to cognition and mood. The vast majority of basic science studies have described positive effects of E2 on cognitive processes at a molecular level, and, importantly, older postmenopausal females exhibit significant deficits when performing tasks that require the use of working memory, attentional processing, and executive function [3–8]. The natural aging process is coincident with menopause, which confounds studies attempting to differentiate between the molecular mechanisms specific to menopause versus aging. Therefore, studies examining the physiological and molecular functions of estrogen receptors during periods of estrogen deprivation with respect to natural aging are requisite to understanding how reintroducing estrogens in aged postmenopausal women will affect neurological processes. In spite of the wealth of studies investigating the effects of HT on relevant health concerns, there are still very few conclusive arguments for or against HT to ameliorate neurological issues. Moreover, it is very likely that the actions of estrogens regulate opposing processes depending upon brain region and genetic composition of neurons involved, creating complex issues regarding the lack of specificity of E2 treatment. Nevertheless, some insight into general functions of E2 in the brain can be gleaned from existing data that demonstrate that (1) there is a critical window of time surrounding menopause for which HT can be beneficial, suggesting that aging is an important factor, (2) progestins are not likely to be beneficial for cognitive and affective neurological issues, and (3) the type of estrogen used may be crucial. Given these important conclusions, this review will focus on the molecular mechanisms of E2 signaling in the brain and how variables that might contribute to these signaling patterns can be altered by age.

2. The Menopausal Transition: E2 Decline and Health Concerns

Menopause is defined by the Mayo Clinic as “the permanent end of menstruation and fertility, occurring 12 months after your last menstrual period.” Menopause is marked by a reduced oocyte number attributable to progressive atresia of ovarian follicles and by declining circulating levels of E2 and progestins. The perimenopausal transition is typically 4–8 years, during which most women experience symptoms including hot flushes, night sweats, mood swings, sleep disturbances, vaginal dryness and atrophy, as well as urinary incontinence, most of which are alleviated by hormone (E2) replacement therapy (HT/ET). Until recently, a great deal of evidence suggested that estrogens have positive effects on cognition, neuroprotection, memory, anxiety, depression, as well as bone and cardiovascular health [5, 9–13].

The paramount studies to present negative consequences of HT were the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) and the ancillary studies including the Women's Health Initiative Study on Cognitive Aging (WHISCA) and the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS). Data from these studies showed that a combination therapy of conjugated equine estrogen/medroxyprogesterone acetate (CEE/MPA) increased risk for mild cognitive impairment and decreased global cognitive functioning, but CEE alone did not have any significant effect on cognitive functioning [14–16]. Poststudy analyses have revealed many confounding factors in the WHI studies ranging from the choice of a reference group to the age of participants and the choice of ET used (CEE) [4, 17, 18], as well as the use of MPA, which has been shown to have adverse effects on memory after one dose in adulthood [19]. While the WHI studies showed negative or neutral effects of estrogen therapy, many other basic science and observational studies have shown just the opposite. The Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) recently announced findings that suggested that E2 therapy had a positive effect on mood and memory. Participants receiving CEE showed significant improvement in symptoms of depression, anxiety, and a trend toward reduced feelings of anger/hostility. Importantly, CEE treatment or Premarin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Philadelphia, PA, USA) is a mixture of several estrogenic compounds, but primarily estrone sulfate and ring B unsaturated estrogens such as equilin and equilenin, which can differentially activate ER isoforms as compared to E2 alone [20]. Participants receiving CEE self-reported a trend toward better recall of printed materials as compared to placebo, and women using transdermal E2 tended to report fewer memory-related complaints. Another study performed a meta-analysis of 36 randomized HT clinical trials (RCT) focusing on cognition [21]. The length of treatment, type of memory, variety of hormone, and age of the participant were all variables that drastically altered the outcomes of each trial. Results from the meta-analysis indicated that verbal memory was most often affected by HT, and younger women tended to have a better outcome in this category. There was also a trend toward worse outcomes on memory tests in patients treated with CEE treatment alone compared to those treated with biologically identical E2. Moreover, treatment with estrogens alone (i.e., absent cotreatment with progestins) was overall associated with positive results on memory tests. In conclusion, data from these clinical trials have revealed the importance of using bioidentical hormones for HT and that downstream signaling processes for memory and mood can be affected by the choice of estrogen and/or combination of hormones used as therapeutics.

3. Estrogen Receptor Signaling

Estrogen signaling is mediated primarily through two receptors (ERα and ERβ). ERs are class I members of the nuclear hormone superfamily of receptors, deemed as a ligand-inducible transcription factors [22]. Classically, ERs were thought to be localized in the cytoplasm bound to intracellular chaperone proteins until induced by ligand to translocate to the nucleus, according to the two-step hypothesis coined by Jensen et al. [23]. Following ligand binding, ERs undergo a conformational change that allows for dimerization, translocation to the nucleus, and DNA binding or association with other transcription factors to regulate gene transcription; however, we now know that ER signaling is much more complex.

For example, ERs are involved in other “nongenomic” molecular functions including RNA processing, second-messenger signaling cascades, and rapid dendritic spine formation in neurons. Of particular importance in the brain, the discovery of rapid signaling processes implicates E2 as a neuromodulator; however, local synthesis of E2 has been the subject of fervent debate. While it is likely that there is de novo synthesis of E2 within the parenchyma, due to technical challenges, the exact levels and changes with age and circulating hormones have yet to be identified [24, 25]. It is also difficult to determine how local E2 may affect ER action. Most reports suggest an implicit role for local E2 at the synapse and membrane [26], but whether nuclear/genomic activities of ERs are affected has yet to be established. Recent data from our laboratory demonstrate that E2 can alter miRNA-expression [27], and from others have shown that ERα can associate with miRNA processing enzymes such as Drosha [28]. Data from our laboratory (unpublished observations) and others have shown that ERs are involved in alternative splicing processes, and one study has demonstrated direct interaction of phosphorylated ERα with splicing factor (SF) 3a p120 that potentiates alternative splicing through EGF/E2 crosstalk [29]. These relatively novel ER functions may be explained by examining well-studied components of classic NR signaling such as the structural properties of the receptors.

4. Structural Contributions to ER Activity

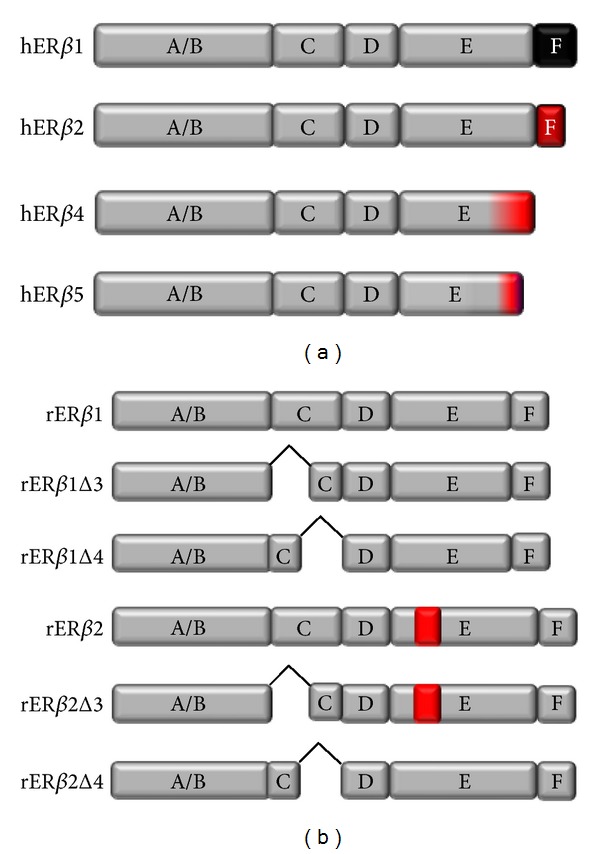

Class I nuclear receptors (NRs) including ERα and ERβ have a characteristic structure comprised of five functional domains labeled A–E, and a sixth domain (F) unique to ERs (Figure 1). The A/B domain contains an activator function-1-(AF-1-) like domain that allows for associations with coregulatory proteins and other transcription factors. Notably, the A/B domain is the least conserved domain between ERα and ERβ (17% homology), and it may be responsible for the observed ligand-independent actions of ERβ [30]. The C domain, is a DNA-binding domain that allows the receptor to bind a specific DNA sequence called an Estrogen Response Element (ERE) to regulate transcription of genes containing this sequence within their promoter region. Two zinc fingers forming a helix-loop-helix structure allow for appropriate spacing (3 nucleotides) between an inverted hexameric palindromic repeat that is described as the canonical ERE. The exact nucleotide sequence of hormone response elements can vary and in part, dictate the affinity an NR has to regulate a particular gene [31]. The D domain is a hinge-like region that allows the receptor to undergo a conformational change once activated and also contains a nuclear localization sequence. The best-studied region of ERs is the E domain, also referred to as the ligand-binding domain (LBD). Characterization using X-ray crystallography has shown that the LBD consists of 12 ordered alpha-helices that are essential for conferring ligand specificity [32]. The orientation of helix 12 is critical to the conformation NRs adopt once bound to a particular type of ligand, and ultimately influence the ability of the receptor to bind other proteins and activate gene transcription. Helix 12 contains the core residues of the activator function-2 (AF-2) domain, a short amphipathic conserved alpha-helix that interacts with coregulatory proteins through an LxxLL motif. Adjacent to the AF-2/E domain is the less characterized F domain that is unique to ERs. ERα has a larger F domain than ERβ, and the two receptors only share about 18% homology within this region. ERα dimerization and interactions with coregulators are altered when the F domain is deleted or modified, demonstrating that the F domain is a relevant structure for ERα transcriptional regulation, but a clear role for this domain for ERβ has yet to be determined [33, 34]. Importantly, naturally occurring human ERβ splice variants have altered E and F domains, which can affect hormone responsiveness in tissues that express these variants.

Figure 1.

Representative image of domains within human and rat ERβ splice variants. Human ERβ splice variants (a) contain truncations and changes in amino acid sequence in the C-terminus E and F domains. Rat ERβ splice variants (b) contain an 18-amino-acid insert in the LBD/E domain and/or exon 3/4 exclusions in the DNA-binding domain.

While the overall sequence homology between ERα and ERβ is greater than 60%, the specific gene targets of each receptor appear to be vastly different. For example, a variety of cancer cell models have identified an antiapoptotic, proliferative role for ERα, whereas ERβ tends to promote apoptosis and regulate antiproliferative genes [35–38]. It is well known that ERα and ERβ are readily able to form heterodimers when expressed in the same cell, adding another layer of complexity to the regulation of estrogen responsive genes. ERα and ERβ both bind EREs, but the affinity for one receptor or the other can depend highly on the specificity of the DNA sequence being regulated and the ligands present [39–41]. Therefore, it is important to consider the overlap in ERα and ERβ preferred transcriptional response elements when both receptors are expressed in the same system.

5. Expression of ERs in the Brain: A Complex Story

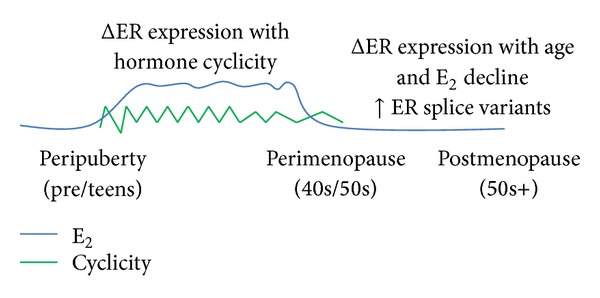

The principal determinant of E2 action is the expression of ERα, ERβ, their alternatively spliced variants, or some combination of each, which is cell-type specific even within distinct brain nuclei. ER expression has been studied extensively, yet there are few definitive statements that can be made about the regulation of ERβ expression. It can be noted that ER expression profiles can vary throughout the life-span, in particular when there are dramatic changes in circulating hormone levels, such as puberty and menopause (Figure 2). Not only can ER expression vary dependent upon sex, age, and E2 treatment, but these factors can also direct subcellular localization, which ultimately dictates ER functions. Accordingly, contextual studies that map the exact cellular expression patterns of each receptor and their splice variants are a critical first step in creating a comprehensive examination of E2-regulated processes in any system.

Figure 2.

Timeline showing factors affecting ER gene expression throughout the female life-span. Brain ER gene expression patterns are altered with age, sex, and exposure to circulating hormone. Circulating hormones fluctuate with age, most dramatically at the time of puberty and menopause therefore contributing to changes in ER gene expression. Additionally, alternative splicing increases with age, thus potentially diversifying the ER gene expression profile.

The female vertebrate reproductive organs tend to be dominated by the expression of ERα, whereas ERβ is expressed largely in nonreproductive tissues. ERβ was first cloned from prostate tissue [42], and it has since been shown to have the highest levels of expression in the central nervous system and cardiovascular tissue, as well as lung, kidney, colorectal tissue, mammary tissue, and the immune system [43]. Consequently, some of the most prominent phenotypic problems observed in mice lacking a functional ESR2 gene (βERKO mice) are neurological deficits. By contrast, ERα knockout mice have no gross brain-related phenotypes, but they exhibit decreased E2-mediated neuroprotection following an ischemic event [44]. Overall, the phenotypes observed in ERα- and ERβ-null mouse models suggest that ERβ is potentially more important for mediating nonreproductive E2-governed processes than ERα.

ERα and ERβ are coexpressed in some regions of the hypothalamus, such as the medial amygdala (MeA), the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), and the periaqueductal grey area. However, ERα is predominant in hypothalamic nuclei that control reproduction, sexual behavior, and appetite (e.g., arcuate (ARC), medial preoptic (MPoA), and ventromedial (VM)) but ERβ is the predominant isoform in the nonreproductive associated nuclei (e.g., paraventricular (PVN), supraoptic (SON), and suprachiasmatic (SCN)) as well as the hippocampus, dorsal raphe nuclei, cortex, and cerebellum [45, 46]. In the hippocampus, mRNA and protein for both ERs have been detected and are well established as mediating both genomic and nongenomic processes [47–49]. Nuclear and extranuclear ERβ mRNA and immunoreactivity (IR) have been detected in principal cells as well as in many other nuclei of cells within the ventral CA2/3 [46, 47]. Although not as prevalent as ERβ, ERα has also been detected in the hippocampus, primarily within GABAergic interneurons [47, 49].

ER expression is also often found to be sexually dimorphic. As one would expect, many regions of the hypothalamus exhibit a great deal of sexual dimorphism due in part to differences in sexual behavior and regulation of gonadotrophic hormones, but regions such as the BNST also display some sex-related differences in ER expression. For example, ERα in the BNST can be induced in somatostatin-positive neurons of male, but not female, rats [50]. ERs have also been shown to be sexually dimorphic in the developing rodent hippocampus, but not in adults [51, 52]. However one report identified ERβ mRNA in the adult female, but not male, rhesus macaque basal ganglia and hippocampus [53]. Importantly, a lack sexually dimorphic regional ER expression does not preclude differential responses to estrogens, as other effector molecules can alter estrogen-responsive processes.

Expression of ERs can vary not only with chromosomal sex, but also in response to the hormonal milieu. For instance, it is well accepted that ERα expression is autoregulated by E2, primarily through proteasomal degradation, [54] but also perhaps on a transcriptional level by E2-bound ERβ [55]. The ERβ gene (ESR2) promoter region has not been extensively characterized, but it has been shown to contain E2-responsive cis sequence-binding sites for Oct-1 and Sp-1, which interact with ERs via trans factors suggesting a molecular mechanism for E2-mediated autoregulation of its receptor. There is also an Alu repeat sequence that may contain an ERE that could act as an ER-dependent enhancer [56]. Conversely, in vitro and in vivo studies investigating the effects of E2 on ERβ expression have yielded inconsistent conclusions depending upon cell type, animal species, and age. For instance, in the T47D human breast cancer cell line, E2 upregulated ERβ [57]. However, ERβ expression was decreased by E2 in mammary glands of lactating mice that coexpress ERα [58]. ERβ was also decreased in the PVN of rats subjected to OVX + E2 [59]. Thus, it appears that E2 may regulate ERα and ERβ; however, this effect is highly dependent upon cell type, and possibly upon the coexpression of other ERs.

In addition to sex and E2, aging also appears to influence ER expression. Overall, decreased nuclear E2 binding has been reported in the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary of aged female rats compared to young ones, but the change in E2 binding was not necessarily attributed to a decrease in total ER expression [60, 61], suggesting a shift in the ratio of ERs and/or subcellular localization. While overall nuclear E2 binding within the hypothalamus may decrease with age, changes to ER expression patterns with age remain contentious. In general, it appears that age alone does not eliminate ERα expression in the brain, but regional specificity and E2 availability may be important factors [62, 63], and an increase in ESR promoter methylation has been correlated with age in other systems [64, 65]. One study reported varied middle age-specific reduction in hypothalamic ER with E2 treatment [66], yet another study showed that E2 decreased hypothalamic ER expression significantly in all ages tested (3, 11, and 20 months) [67]. Specific to ERα, a work by Chakraborty and colleagues determined that immunoreactive cell numbers did not always change following OVX and E2 replacement. Rather, their study revealed that with advanced age (24–26 months compared to 3-4 and 10–12 months) the number of ERα-positive cells was increased or it stayed the same in different hypothalamic nuclei [68]. In the hippocampus, ERα was decreased after long-term estrogen deprivation (LTED, 10 weeks), regardless of E2 replacement following LTED, but E2 deprivation had no effect on ERβ [11]. The same report demonstrated decreased levels of ERβ in very old rats (24-month females compared to 3-month diestrus females). In general, most reports suggest that aging decreases ERβ expression, but, like ERα, this effect may be highly region specific. An age-related decrease in ERβ expression in the brain is underscored by a corresponding increase in CpG methylation of the ESR2 promoter in middle-aged (9–12 months) rats [69]. Other reports describe decreases in ERβ protein and message in some areas but not in others [63, 70]. Taken together, there are a number of reports attempting to identify the parameters that control ER expression such as age, sex, and response to E2; however, with such vast deviations in expression with cell type there is still much to be learned about expression of these receptors, especially in brain regions controlling nonreproductive behaviors.

6. Alternative Splice Variants

Based upon the highly variable reports that differ in sex and age of animals as well as exposure to hormone, it may be possible that these studies are unknowingly detecting changes in splice variant expression, which could change E2 responsiveness as well as downstream gene regulation. Not only can ERs heterodimerize to regulate gene transcription, but there are a number of alternatively spliced variants of each receptor that are endogenously expressed and that potentially contribute to the diverse tissue-specific actions of E2. Alternative splicing of ERs alters inherent signaling properties of the receptor including ligand, and DNA-binding affinities, nuclear localization, and dimerization, depending on where the alternative splice site is encoded. A number of ER splice variant transcripts and other proteins have been identified in demented human brains, breast, and prostate, and, in some reports, an increase in alternative splicing is correlated with pathology [71–75]. Also interesting, age alone may increase alternative splicing of some gene products [76]. The identified ERβ human splice variants are truncated at the C-terminus of the receptor (Figure 1(a)); however, we provided experimental evidence that the C-terminus of the receptor is not required for ERβ-mediated transcription, especially with regard to the identified human splice variants [77]. Unlike the human splice variants, rodent ERβ splice variants identified to date have been shown to have either an exon inclusion in the ligand-binding domain, creating (rERβ2), or an exon deletion in the DNA-binding domain rERβ1Δ3 or rERβ1Δ4 or both rERβ2Δ3 and rERβ2Δ4 (Figure 1(b)) [37, 78, 79]. Exon inclusion (rERβ2 variants) has been shown to produce a protein that binds E2 with a 35-fold decrease in affinity. In contrast, ERs with exon 3 and 4 deletions are unable to bind DNA, but they can still mediate transcription through protein:protein interactions with other transcription factors such as AP-1, and it can bind E2 as well as rERβ1 [37, 80]. Importantly, the transcriptional functions of rERβ1 are significantly altered when coexpressed with other splice variants, likely due to a weaker interaction with coactivator proteins [81, 82]. Despite lower E2 binding and/or lack of DNA binding, the rodent and human splice variants retain a constitutive ligand-independent transcriptional function, at both basic and complex promoters [77, 83, 84], suggesting that these splice variants have an important endogenous biological function. Indeed, unliganded ERβ1 or apo-ERβ1 has been reported to regulate a subset of genes distinct from those regulated by ERβ1 when bound to E2 [41]. Conversely, the human splice variants do not bind ligand with great affinity [85], and they might therefore only regulate the class of genes that unliganded ERβ targets.

The downstream target genes of ERβ splice variants might be an important consideration at the time of menopause, as ER expression profiles and alternative splicing tend to change with age [76]. One recent report demonstrated an increase in ERβ2 expression in the hippocampus of 9-month old, middle-aged rats following short-term (6 days) E2 deprivation that was significantly decreased compared to the Sham group after E2 administration [86]. Importantly, E2 replacement no longer affected ERβ2 expression in the hippocampus after LTED (180 days). That study also reported a decrease in hippocampal neurogenesis and increased floating behavior in a forced swim test, thus functionally correlating increased ERβ2 with mood regulation and potentially cognition. Thus, the expression and functions of ERβ splice variants are absolutely critical to understand the effects of estrogen particularly at times of sustained E2 deprivation with regard to cognition and affect. While ERβ2 expression has been assessed in the young male rat brain [87], and other variants have been described in some brain regions [80, 88], there is a general lack of data on most ERβ splice variants, especially in aged female brains.

Some of the splice variants identified to date have been characterized as dominant negative receptors, serving to inhibit activation of the full-length receptor [89]; however, most identified variants do not bind ligand with the same affinity and have the potential to differentially regulate target genes. While several splice variants for ERβ have been identified in many model systems including mouse [90], rat [45, 46], and monkey [91], there is a general lack of comparative studies on expression and functionality of human ERβ variants, especially in neuronal systems. Furthermore, changing expression levels of one or more alternatively spliced variants during a period of E2 deprivation may drastically change general receptivity and downstream functions of E2.

7. Novel Protein:Protein Interactions for E2-Mediated Nuclear Processes

Protein:protein interactions are an essential relay in the regulation of dynamic cellular processes. Immediately following translation, ERs typically associate with a chaperone protein to ensure proper folding, protect from degradation, and assist the ER in becoming poised to accept ligand. Once bound to ligand, ERs can dimerize and act as transcription factors to mediate gene regulation or associate with membrane proteins to initiate a signaling cascade. When acting as transcription factors, ERs associate with a number of coregulatory proteins that assist in activating or repressing E2-regulated genes. Coregulatory interactions are more characterized for ERα than ERβ, and, importantly, less clear is how ERβ mediates ligand-independent transcription. In addition to the well-established ER interaction partners, many novel interacting proteins have not yet been characterized and could be critical for nuclear processes not limited to gene transcription.

8. HSPs and Chaperone Proteins

According to the classical two-step hypothesis, inactive nuclear receptors are constantly accompanied and protected from degradation by a number of chaperone proteins, typically members of the heat-shock protein (HSP) family. This receptor:chaperone complex has been studied extensively, and while the idea of a protective role for chaperones is well supported, this complex can also perform other functions. For instance, HSP:ER complexes can serve to preactivate a hormone receptor by forcing a conformational change in ER such that it is able to bind its cognate hormone. The initial HSP complex consists of the ER, HSP70, and HSP70-interacting protein (HiP), as well as other accessory and scaffolding proteins [92]. HSP90 is recruited to the complex, and HSP70 dissociates, creating the mature HSP:ER complex [93]. HSP90 induces a conformational change in the nuclear receptor, and the ER is released from the complex, ready to dimerize and bind DNA or other transcription factors to regulate gene transcription. However, some studies suggest that HSPs could have a broader role than originally thought. For example, in Drosophila, HSPs are required for DNA binding, and in some instances they may regulate NR action [94]. Interestingly, aging and E2 can alter HSP70 in a cell-type specific manner [95–98]. However, recent data from our lab (Table 1) demonstrated that HSP70 more readily associates with ERβ in aged female hippocampus following E2 treatment compared to the young ones in which HSP70:ERβ association decreased following E2 treatment. We also observed no significant changes in HSP70 or ERβ expression, suggesting that changes in the HSP70:ERβ interaction with age in response to E2 change are a result of E2 responsiveness and/or activation of ERβ.

Table 1.

Protein interactions with ERβ were altered by age and E 2. Selected proteins that were significantly altered (P < 0.05) in their association with ERβ depending on age and E 2 treatment. Experimental paradigm: young (3 month) and aged (18 month) female Fischer 344 rats were ovariectomized and hormone deprived for 7 days. Following deprivation, animals were administered 2.5 μg/kg E 2 (plasma levels = 79.45 ± 22.5 pg/mL) or vehicle (safflower oil) via subcutaneous injection once/day for 3 days. Nuclear protein was isolated from the ventral hippocampus and coimmunoprecipitated for ERβ (a beam 14C8) and associated proteins. Protein interactions were identified and quantified using 2D-DIGE/DeCyder and ESI MS/MS. YV = young + vehicle; YE = young + E 2; AV = aged + vehicle; AE = aged + E 2.

| Accession no. |

Molecular weight (Kda) |

Estimated isoelectric point |

PEAKS score |

% Coverage | ID | Interaction with ERβ | Function | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young vehicle |

Young E 2 |

Aged vehicle |

Aged E 2 |

|||||||

| gi∣ 149038929 | 80 | 5.75 | 49.4 | 6.43 | Gelsolin | — | ↑ | — | — | Actin-binding coactivator |

| gi∣ 116242507 | 75 | 5.97 | 93 | 14.58 | Heat-shock protein 70 | — | ↓ | — | ↑ | Chaperone |

| gi∣ 120538378 | 47 | 5.7 | 93.2 | 10.72 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H1/2 | — | ↑ | — | — | RNA splicing |

9. Transcriptional Proteins and ERs

The process of transcribing DNA into RNA is a systematic process that involves multiprotein complexes binding to DNA, modifying histone marks, and initiating RNA synthesis. ERα, but not ERβ, has been shown to directly interact with TFIIB, IIE, IIF, and TIID proteins that initiate transcription [99, 100]. However, experimental evidence from co-immunoprecipitation studies has demonstrated interactions between ERβ coregulatory proteins as well as other transcription factors. Coregulatory proteins are transcriptional accessory proteins that enhance or repress transcription of target genes. In general, coactivators enhance gene transcription, whereas corepressors block it. However, recent data suggest that seemingly nontranscriptional proteins may have context-dependent coregulatory functions. Importantly, certain coregulators can also be governed by age and E2 [101–103]; thus, recent discoveries imply that ER-mediated gene regulation is not as well understood as previously thought.

The best studied and well-established group of coregulatory proteins that selectively associate with NRs is the steroid receptor coactivator (SRC/p160) family. The SRC family is composed of three members, SRC-1, SRC-2, and SRC-3, all of which contain canonical LxxLL motifs known as the nuclear receptor (NR) box. This motif interacts with AF-2 domains in ERβ, as well as other NR family members such as glucocorticoid receptor (GR), progesterone receptor (PR), thyroid hormone receptor (TR), and ERα [104]. SRC members have intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity (HAT, DNA activating) and interact with CREB-binding protein (CBP) [105]. CBP/p300 proteins are also coactivators that have intrinsic HAT activity and can recruit ASC-2 and other known coregulatory proteins [106]. Confirmed coregulatory interaction partners for several NRs that do not belong to the SRC family include estrogen-receptor-association protein (ERAP 140) [107], nuclear corepressor (NCoR) [108] silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) [109], and many others. As is the case with our understanding of ERβ interactions with basic transcriptional machinery, studies investigating ERβ:coregulator interactions are sparse, which may be due to uniquely challenging issues associated with ERβ, such as a lack of high-fidelity biochemical tools, complicated structural properties, and, or pleiotropic physiological actions that are specific to ERβ.

In 2010, Anna Ma lovannaya and colleagues directed a high-throughput study (not including ERβ) aiming at compiling a database for the endogenous coregulator pool “nuclear receptor complexome” [110]. In this study, a number of novel protein interactions were identified, and studies such as these are identifying proteins as “coregulators” that had been previously thought to serve completely different functions. One group of relatively novel coregulatory proteins are the E3 ubiquitin-protein ligases such as E6-associated proteins (E6-AP) [111]. While these proteins were thought to serve primarily as ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, they have recently been highlighted as transcriptional enhancers of NR-mediated activity independent of ligase function. Similarly, a group of E3-ligases that conjugate small ubiquitin like modifier (SUMO) proteins to a target protein called PIAS are also now considered NR coregulators and they utilize a typical LxxLL motif. In one study, a decrease in ER expression following LTED or with advanced age coincided with an increase in ER association with an E3-ubiquitin ligase, CHIP [11]. Together, these newly described roles for HSPs and E3 ligases raise novel questions about estrogen signaling, such as when is an E3-ligase:ER complex targeted for transcriptional regulation versus degradation? Also, when are HSPs merely performing a chaperone/protective function versus directing transcriptional processes? Future efforts aiming at elucidating the complexity of age-related changes in receptor structure and recruitment of coregulatory proteins could provide important insight into these seemingly paradoxical findings.

10. Nuclear Actin: Setting the Stage

Coregulatory interactions may be poised upon a bed of nuclear actin, which has recently been identified as a dynamic molecular stage for which many nuclear processes are performed such as transcription, chromatin remodeling, mRNA processing, and nuclear import/export. The general events that initiate transcription are well established; however, the process by which all of the molecular components are temporally layered into a complex is still unclear. Nuclear actin is essential in forming the preinitiation complex on a promoter, elongation, and RNP organization, as well as remodeling of chromatin [112–114], and, as mentioned previously, ERs are also key factors in these processes. In one study, ERα and β-actin were coimmunoprecipitated on the E2 responsive pS2/TFF1 promoter, indicating that ER and nuclear actin may work in concert to regulate transcriptional processes under control of estrogens [115]. The interaction between ERs and actin is not yet fully investigated, but data from our lab (unpublished observations) and others [116] imply that both ERα and ERβ may utilize nuclear actin to perform various functions. Another actin-binding, protein gelsolin, caps actin filament ends, and it has been shown to be an NR coactivator [117, 118]. Gelsolin may assist in actin polymerization, allowing transcriptional machinery to be brought in proximity of target genes; however, it remains unclear how gelsolin enhances AR/ER transcriptional activity. Data from our lab indicate that gelsolin:ERβ interactions increase with E2 treatment in young but not aged animals (Table 1). Gelsolin has been shown to increase with age [119], but a lack of significant interaction with ERβ despite increased expression of gelsolin could again suggest an alteration in ERβ function with age.

Actin is also commonly associated with ubiquitous multifunctional RNA-binding proteins such as heterologous nuclear riboproteins (hnRNPs), which also associate with ERs [120]. hnRNPs associate within the matrix of nuclear actin, accompany transcripts out of the nucleus, participate in alternative splicing, and can modulate transcription [121]. Phosphorylated hnRNPK has been shown to mediate translation of specific mRNAs [122], and hnRNPH is involved in splicing and mRNA polyadenylation [123, 124]. In the past, the association of NRs with hnRNPs was thought to be nonspecific due to the ubiquitous nature of these proteins, but recent studies are no longer ruling out an important interaction between NRs and hnRNPs that may assist in transcription and/or splicing [125, 126]. Data from our lab and others demonstrate a dynamic interaction between both ERα and ERβ and hnRNPs (Table 1), and, furthermore, data, demonstrated that E2 might regulate expression of members of the hnRNP family [127]. As noted previously, age-related increases in splicing could lead to aberrant signaling, not only for E2-mediated processes, but also for cellular processes in general.

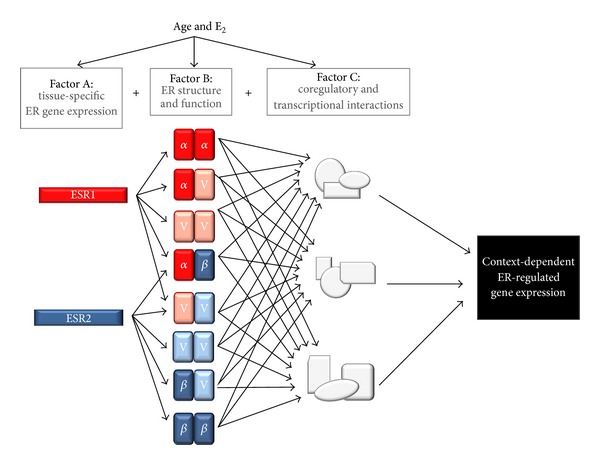

Nuclear ER interaction partners have historically been a distinct class of nuclear receptor coregulators that seemed to solely assist ERs in gene transcription; however, the number of interaction partners for ERs is increasing. Further investigation into ERβ-associated proteins is required, as far as NRs are concerned; data specific to ERβ are inadequate to make broad conclusions. Moreover, post-translational modifications to coregulatory proteins, ERs or changes in their expression patterns due to age or sustained estrogen deprivation could all contribute to an altered microenvironment, setting the stage for atypical estrogen signaling upon therapeutic reinstatement of hormones (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Age and hormonal milieu exponentially increase the potential diversity of estrogen receptor signaling leading to context-dependent gene regulation. Age and E2 influence ER gene expression, alternative splicing, coregulatory protein expression, and interaction, which ultimately direct ER-target gene transcription.

11. Estrogens and Cognition

Most empirical and observational data give merit to the idea that estrogens have a positive effect on cognitive processes, increased spine densities [128, 129], enhanced synaptic plasticity [130–132], and improved memory [133, 134]; however, the particular receptor(s) and the mechanisms that regulate these processes remain unclear. There are a myriad of behavioral studies suggesting that E2 enhances prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampal-dependent tasks. For example, long-term E2 deprivation diminished aged female rhesus macaques' performance in a delayed response task, a PFC- dependent task [135]. E2 also enhanced object recognition under a number of different paradigms [136–138], and there are also multiple lines of evidence supporting E2-mediated neuroprotection which may be important for cognition, especially after stroke [139–142].

Pharmacological targeting of the receptors with ER selective ligands has been a standard method for investigating the behavioral, physiological, and cellular actions of E2 mediated distinctly through ERα and/or ERβ; however, valuable insight has also come from the ERβ-null (βERKO) mice. βERKO mice have significantly fewer neurons in the cortex, hypothalamus, amygdala, and ventral tegmental area compared to WT. They also exhibit neuronal shrinkage and hyperproliferation of glia by 3 months of age, as well as having high levels of apoE and apoE-dependent deposition of amyloid plaques throughout the CNS by 12 months of age [143]. These mice also demonstrate spatial learning deficits in the Morris water maze [144] and a decrease in hippocampal- and amygdala-dependent memory in a fear-conditioning paradigm that is accompanied by decreased synaptic plasticity in hippocampal slice preparations [145]. The critical role of ERβ in higher-level brain functions has been deduced from these studies and others, warranting a full investigation of the wide-spread molecular actions of E2 known to contribute to cellular processes on at least two levels: at the synapse and on the genome.

Long-term potentiation (LTP) is an important component of learning and memory. It represents an increase in synaptic transmission and plasticity that underlies cognitive behaviors, and it is readily altered by E2 in many circumstances. In fact, application of an aromatase inhibitor eliminates CA LTP generated by theta-burst stimulation in intact female neurons, but not male or OVX animals, posing a potentially serious concern for women using aromatase inhibitors for therapeutic treatment of breast cancer [146]. E2 can also enhance or suppress long-term depression (LTD), reducing synaptic transmission, which may be dependent upon the specific receptors involved. In aged male CA1 cells, E2 decreased LTD [147]; however, E2 enhanced LTP in the cerebellum where ERβ is the predominately expressed cognate receptor [148].

Although the majority of studies on cognitive process focus on the rapid effects of E2, late-phase long-term potentiation (L-LTP), depends upon transcription and translation of new mRNA [149] to sustain an increase in synaptic transmission. E2 has been shown to regulate LTP in CA1 pyramidal cells [150] over the span of 48 hours, and this regulation appears to be dependent upon a higher ratio of NMDAR relative to AMPAR. LTP induction requires activation of NR2A-containing NMDARs; however, increased expression of NR2B potentiates LTP magnitude [151]. Notably, E2 increased expression of NR2B mRNA and NR2B expression at the synapse [152, 153], and the E2-induced increase in LTP can be abolished by blocking NR2B receptors [154], suggesting a transcriptional role for ERs in synaptic plasticity. Moreover, E2 application may increase CREB expression and the amount of phosphorylated CREB in regions such as the amygdala [155] and BNST [117, 155], which may be critical in the formation of long-term memories. Taken together, these data demonstrate that E2 regulates neuronal plasticity and memory through its original role as a transcription factor, and also by acting as a general intracellular signaling molecule through regulation of NMDARs and CREB. However, to date, there are little data on the mechanisms by which ERβ regulates these processes, or how the same principles of plasticity may apply to other neurological issues.

12. Estrogens and Mood Regulation

A range of behavioral experiments indicate that E2 modulation of stress, mood, and affect is a complex story, with considerable conflicting data that may, as in other processes, be explained in part by distinct roles for ERα and ERβ. Anecdotally, many women report mood fluctuations as corresponding to changes in circulating estrogen levels, such as what occurs during the menstrual cycle, peripuberty, postpartum, and peri/postmenopause. Incidence of anxiety and depression are observed at perimenopause and when hormone levels are fluctuating [156, 157]. However, E2 can also exhibit anxiogenic properties, and often anxiety and depression present in a comorbid fashion, especially in women [158, 159]. Interestingly, after the age of 55, bouts of depression and anxiety appear to decrease in women [160]. As previously mentioned, perimenopausal women receiving CEE in the KEEPs study reported an improvement in mood, and the primary actions of CEE tend to be mediated through ERβ [20]. A plethora of behavioral studies has mounted in response to observational reports, and at first glance it appears that ERβ has an anxiolytic and antidepressive role; however, there is still an immense void to be filled with respect to biochemical and molecular mechanisms of ERβ and affective disorders. Elucidating the precise molecular mechanisms that require ERβ in plasticity and neurotransmitter processing in brain regions regulating these behaviors will help clarify the role of E2 in stress- and mood-related processes.

Contemporary hypotheses concerning the onset of affective disorders revolve around perturbations to the central processing of environmental stress. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the 3-tiered hierarchical biological system that mediates physical or psychological response to stressors. The primary steroid regulating the HPA axis is cortisol/corticosterone (humans/rats, CORT), a glucocorticoid receptor (GR) ligand that is produced from the adrenals to exert negative feedback upon the HPA system to effectively modulate response to stressors. The paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus (PVN) produces two neuropeptides, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin (AVP), to activate the HPA axis. CRF and AVP synergistically stimulate release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) from the anterior pituitary, which acts on the adrenal cortex to produce CORT. CORT binds GR and negatively regulates CRF and AVP expressions and releases through classical negative feedback mechanisms [161, 162]. ERβ is the main ER expressed in the PVN [158, 163–165], and regulation of AVP is an interesting example of how ER action can vary. AVP expression fluctuates during the menstrual cycle and is usually highest when E2 is low. In fact, oral contraceptives appear to decrease AVP expression, and E2 is thought to inhibit AVP in the human SON [166]. In the rodent system, ERβ and its splice variants activate the rodent AVP promoter independent of ligand [84]; however, the human promoter is repressed by ERβ and splice variants. This discrepancy between the human and rat was mediated by an AP-1 response element on the human AVP promoter that is not present in the rat. Importantly, ERβ acted similarly in the two systems when the AP-1 sequence was deleted from the human promoter, underscoring the striking alterations that small changes in DNA sequence can invoke in E2 signaling pathways and the importance of understanding the experimental context upon which such conclusions are based [77]. On the contrary, rat and human CRF expression was increased in response to E2 in rodent, monkey, and human hypothalamus, but it was inhibited in the placenta [167–170].

In addition to AVP and CRF, glutamatergic and GABAergic projects from regions like the BNST, AMY, PFC, and hippocampus all express ERβ [45, 46] and are likely targets for E2 to exert effects on the HPA axis. Moreover, decreased ERβ mRNA in postmortem locus coeruleus has been found to correlate with suicide [13], and, even more recently, ERβ-mediated hippocampal nitric oxide levels have been implicated in affective behaviors in females, but not males [171]. Neurotransmitter release from these regions influences mood, affect, and stress responses, and E2 increases the rate of monoamine oxidase degradation and serotonin transport which enhances serotonin at the synapse; E2 also increases serotonin receptor expression [172, 173]. Dopamine and serotonin [174] are diminished in the BNST, POA, and hippocampus and caudate putamen (dopamine) of βERKO mice [174] further implicating an important role for ERβ in the regulation of emotion and mood. βERKO mice also display serious morphological and functional abnormalities in the brain that correlate to increased depression and anxiety [12, 175–178]. In addition to βERKO studies, administration of ERβ selective agonists (diarylpoprionitrile, DPN) decreases both stress markers and anxiety-related behaviors in rats [158]. In fact, there have been several studies implicating ERβ and its variants in affective behaviors, but the molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood.

13. Summary

Estrogen-receptor-mediated signaling in the brain regulates neurological processes, many of which translate to cognitive and affective behavioral outputs. When estrogen is declining and becomes replete, as in menopause, a number of neurophysiological changes occur, producing some unwanted changes. The most common and logical remedy is replacement of bioidentical hormone, E2; however, this treatment can be problematic depending upon the length of time a woman has been in a postmenopausal, estrogen-deprived state. This suggests that there is a molecular switch in estrogen-mediated signaling that may allow for drastic change in ER signaling, not to mention the interaction of E2 signaling components and the natural aging process. These changes are likely to include alterations to receptor profiles including expression of alternatively spliced variants that respond differently to E2, changes in the cellular microenvironment that can alter the protein:protein associations which ultimately leads to changes in ER-mediated gene transcription, and synaptic transmission. ERβ in particular is widely expressed and implicated positively in the regulation of memory and mood fluctuations, two of the most commonly reported neurological issues in postmenopausal women. It is important to understand the actions of ERβ in the areas regulating these processes to identify what, when, how, and for whom hormone therapy may be a useful treatment to rectify cognitive and affective issues.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIA RO1. AG033605-01 and, NIH T32 AG031780. The authors, N. N. Mott and T. R. Pak, have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Bengtsson C, Lindquist O, Redvall L. Is the menopausal age rapidly changing? Maturitas. 1979;1(3):159–164. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(79)90003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh A, Kaur S, Walia I. A historical perspective on menopause and menopausal age. Bulletin of the Indian Institute of History of Medicine (Hyderabad) 2002;32(2):121–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verhaeghen P, Cerella J. Aging, executive control, and attention: a review of meta-analyses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2002;26(7):849–857. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wroolie TE, Kenna HA, Williams KE, et al. Differences in verbal memory performance in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy: 17β-estradiol versus conjugated equine estrogens. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;19(9):792–802. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181ff678a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherwin BB. Estrogenic effects on memory in women. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1994;743:213–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb55794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherwin BB. Hormones, mood, and cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;87(2, supplement):20S–26S. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sherwin BB. Sex hormones and psychological functioning in postmenopausal women. Experimental Gerontology. 1994;29(3-4):423–430. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips SM, Sherwin BB. Effects of estrogen on memory function in surgically menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1992;17(5):485–495. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(92)90007-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindsay R, Aitken JM, Anderson JB. Long term prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis by oestrogen. Evidence for an increased bone mass after delayed onset of oestrogen treatment. The Lancet. 1976;1(7968):1038–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)92217-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(13):1465–1477. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.13.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q-G, Han D, Wang R-M, et al. C terminus of Hsc70-interacting protein (CHIP)-mediated degradation of hippocampal estrogen receptor-α and the critical period hypothesis of estrogen neuroprotection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(35):E617–E624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104391108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krezel W, Dupont S, Krust A, Chambon P, Chapman PF. Increased anxiety and synaptic plasticity in estrogen receptor β-deficient mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(21):12278–12282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221451898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Östlund H, Keller E, Hurd YL. Estrogen receptor gene expression in relation to neuropsychiatric disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;1007:54–63. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(20):2651–2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Kuller L, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and incidence of probable dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: women’s Health Initiative Memory Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(24):2947–2958. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.24.2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(20):2663–2672. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson VW, Benke KS, Green RC, Cupples LA, Farrer LA. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and Alzheimer’s disease risk: interaction with age. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 2005;76(1):103–105. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.024927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garbe E, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and acute coronary syndromes: methodological issues between randomized and observational studies. Human Reproduction. 2004;19(1):8–13. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braden BB, Garcia AN, Mennenga SE, et al. Cognitive-impairing effects of medroxyprogesterone acetate in the rat: independent and interactive effects across time. Psychopharmacology. 2011;218(2):405–418. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhavnani BR, Tam S-P, Lu X. Structure activity relationships and differential interactions and functional activity of various equine estrogens mediated via estrogen receptors (ERs) ERα and ERβ . Endocrinology. 2008;149(10):4857–4870. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogervorst E, Bandelow S. Sex steroids to maintain cognitive function in women after the menopause: a meta-analyses of treatment trials. Maturitas. 2010;66(1):56–71. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mangelsdorf DJ, Thummel C, Beato M, et al. The nuclear receptor super-family: the second decade. Cell. 1995;83(6):835–839. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90199-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen EV, Suzuki T, Kawashima T, Stumpf WE, Jungblut PW, DeSombre ER. A two-step mechanism for the interaction of estradiol with rat uterus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1968;59(2):632–638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.2.632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naftolin F, Horvath TL, Jakab RL, Leranth C, Harada N, Balthazart J. Aromatase immunoreactivity in axon terminals of the vertebrate brain: an immunocytochemical study on quail, rat, monkey and human tissues. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;63(2):149–155. doi: 10.1159/000126951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roselli CE, Abdelgadir SE, Rønnekleiv OK, Klosterman SA. Anatomic distribution and regulation of aromatase gene expression in the rat brain. Biology of Reproduction. 1998;58(1):79–87. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod58.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balthazart J, Ball GF. Is brain estradiol a hormone or a neurotransmitter? Trends in Neurosciences. 2006;29(5):241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pak TR, Rao YS, Prins SA, Mott NN. An emerging role for microRNAs in sexually dimorphic neurobiological systems. Pflügers Archiv. 2013;465(5):655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamagata K, Fujiyama S, Ito S, et al. Maturation of microRNA is hormonally regulated by a nuclear receptor. Molecular Cell. 2009;36(2):340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuhiro Y, Mezaki Y, Sakari M, et al. Splicing potentiation by growth factor signals via estrogen receptor phosphorylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(23):8126–8131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tremblay A, Tremblay GB, Labrie F, Giguère V. Ligand-Independent recruitment of SRC-1 to estrogen receptor β through phosphorylation of activation function AF-1. Molecular Cell. 1999;3(4):513–519. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meijsing SH, Pufall MA, So AY, Bates DL, Chen L, Yamamoto KR. DNA binding site sequence directs glucocorticoid receptor structure and activity. Science. 2009;324(5925):407–410. doi: 10.1126/science.1164265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bourguet W, Germain P, Gronemeyer H. Nuclear receptor ligand-binding domains: three-dimensional structures, molecular interactions and pharmacological implications. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2000;21(10):381–388. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01548-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koide A, Zhao C, Naganuma M, et al. Identification of regions within the F domain of the human estrogen receptor α that are important for modulating transactivation and protein-protein interactions. Molecular Endocrinology. 2007;21(4):829–842. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Skafar DF, Koide S. Understanding the human estrogen receptor-alpha using targeted mutagenesis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2006;246(1-2):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang EC, Frasor J, Komm B, Katzenellenbogen BS. Impact of estrogen receptor β on gene networks regulated by estrogen receptor α in breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2006;147(10):4831–4842. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu X, Leav I, Leung Y-K, et al. Dynamic regulation of estrogen receptor-β expression by DNA methylation during prostate cancer development and metastasis. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164(6):2003–2012. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63760-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petersen DN, Tkalcevic GT, Koza-Taylor PH, Turi TG, Brown TA. Identification of estrogen receptor β2, a functional variant of estrogen receptor β expressed in normal rat tissues. Endocrinology. 1998;139(3):1082–1092. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helguero LA, Faulds MH, Gustafsson J-Å, Haldosén L-A. Estrogen receptors alfa (ERα) and beta (ERβ) differentially regulate proliferation and apoptosis of the normal murine mammary epithelial cell line HC11. Oncogene. 2005;24(44):6605–6616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulakosky PC, McCarty MA, Jernigan SC, Risinger KE, Klinge CM. Response element sequence modulates estrogen receptor α and β affinity and activity. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2002;29(1):137–152. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0290137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grober OMV, Mutarelli M, Giurato G, et al. Global analysis of estrogen receptor beta binding to breast cancer cell genome reveals an extensive interplay with estrogen receptor alpha for target gene regulation. BMC Genomics. 2011;12(article 36) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vivar OI, Zhao X, Saunier EF, et al. Estrogen receptor β binds to and regulates three distinct classes of target genes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(29):22059–22066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.114116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuiper GGJM, Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Nilsson S, Gustafsson J-Å. Cloning of a novel estrogen receptor expressed in rat prostate and ovary. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(12):5925–5930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuiper GGJM, Carlsson B, Grandien K, et al. Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors and α and β . Endocrinology. 1997;138(3):863–870. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.3.4979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dubal DB, Zhu H, Yu J, et al. Estrogen receptor alpha, not beta, is a critical link in estradiol-mediated protection against brain injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(4):1952–1957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041483198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shughrue PJ, Scrimo PJ, Merchenthaler I. Evidence for the colocalization of estrogen receptor-β mRNA and estrogen receptor-α immunoreactivity in neurons of the rat forebrain. Endocrinology. 1998;139(12):5267–5270. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shughrue PJ, Lane MV, Merchenthaler I. Comparative distribution of estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta mRNA in the rat central nervous system. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;388(4):507–525. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971201)388:4<507::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milner TA, McEwen BS, Hayashi S, Li CJ, Reagan LP, Alves SE. Ultrastructural evidence that hippocampal alpha estrogen receptors are located at extranuclear sites. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2001;429(3):355–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Milner TA, Lubbers LS, Alves SE, McEwen BS. Nuclear and extranuclear estrogen binding sites in the rat forebrain and autonomic medullary areas. Endocrinology. 2008;149(7):3306–3312. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Milner TA, Ayoola K, Drake CT, et al. Ultrastructural localization of estrogen receptor β immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;491(2):81–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herbison AE, Theodosis DT. Absence of estrogen receptor immunoreactivity in somatostatin (SRIF) neurons of the periventricular nucleus but sexually dimorphic colocalization of estrogen receptor and SRIF immunoreactivities in neurons of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. Endocrinology. 1993;132(4):1707–1714. doi: 10.1210/endo.132.4.7681764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kalita K, Szymczak S, Kaczmarek L. Non-nuclear estrogen receptor β and α in the hippocampus of male and female rats. Hippocampus. 2005;15(3):404–412. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ivanova T, Beyer C. Ontogenetic expression and sex differences of aromatase and estrogen receptor-α/β mRNA in the mouse hippocampus. Cell and Tissue Research. 2000;300(2):231–237. doi: 10.1007/s004410000199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pau CY, Pau K-YF, Spies HG. Putative estrogen receptor β and α mRNA expression in male and female rhesus macaques. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1998;146(1-2):59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wijayaratne AL, McDonnell DP. The human estrogen receptor-α is a ubiquitinated protein whose stability is affected differentially by agonists, antagonists, and selective estrogen receptor modulators. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(38):35684–35692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bartella V, Rizza P, Barone I, et al. Estrogen receptor beta binds Sp1 and recruits a corepressor complex to the estrogen receptor alpha gene promoter. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2012;134(2):569–581. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2090-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li LC, Yeh CC, Nojima D, Dahiya R. Cloning and characterization of human estrogen receptor beta promoter. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;275(2):682–689. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vladusic EA, Hornby AE, Guerra-Vladusic FK, Lakins J, Lupu R. Expression and regulation of estrogen receptor ß in human breast tumors and cell lines. Oncology Reports. 2000;7(1):157–167. doi: 10.3892/or.7.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hatsumi T, Yamamuro Y. Downregulation of estrogen receptor gene expression by exogenous 17β-estradiol in the mammary glands of lactating mice. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2006;231(3):311–316. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patisaul HB, Whitten PL, Young LJ. Regulation of estrogen receptor beta mRNA in the brain: opposite effects of 17β-estradiol and the phytoestrogen, coumestrol. Molecular Brain Research. 1999;67(1):165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brown TJ, MacLusky NJ, Shanabrough M, Naftolin F. Comparison of age- and sex-related changes in cell nuclear estrogen-binding capacity and progestin receptor induction in the rat brain. Endocrinology. 1990;126(6):2965–2972. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-6-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rubin BS, Fox TO, Bridges RS. Estrogen binding in nuclear and cytosolic extracts from brain and pituitary of middle-aged female rats. Brain Research. 1986;383(1-2):60–67. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Funabashi T, Kleopoulos SP, Brooks PJ, et al. Changes in estrogenic regulation of estrogen receptor α mRNA and progesterone receptor mRNA in the female rat hypothalamus during aging: an in situ hybridization study. Neuroscience Research. 2000;38(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(00)00150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilson ME, Rosewell KL, Kashon ML, Shughrue PJ, Merchenthaler I, Wise PM. Age differentially influences estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) gene expression in specific regions of the rat brain. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2002;123(6):593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Post WS, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Wilhide CC, et al. Methylation of the estrogen receptor gene is associated with aging and atherosclerosis in the cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular Research. 1999;43(4):985–991. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Issa J-PJ, Ottaviano YL, Celano P, Hamilton SR, Davidson NE, Baylin SB. Methylation of the oestrogen receptor CpG island links ageing and neoplasia in human colon. Nature Genetics. 1994;7(4):536–540. doi: 10.1038/ng0894-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Funabashi T, Kimura F. Effects of estrogen and estrogen receptor messenger RNA levels in young and middle-aged female rats: comparison of medial preoptic area and mediobasal hypothalamus. Acta Biologica Hungarica. 1994;45(2–4):223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller MA, Kolb PE, Planas B, Raskind MA. Estrogen receptor and neurotensin/neuromedin-N gene expression in the preoptic area are unaltered with age in Fischer 344 female rats. Endocrinology. 1994;135(5):1986–1995. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7956921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chakraborty TR, Hof PR, Ng L, Gore AC. Stereologic analysis of estrogen receptor alpha (ER alpha) expression in rat hypothalamus and its regulation by aging and estrogen. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2003;466(3):409–421. doi: 10.1002/cne.10906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Westberry JM, Trout AL, Wilson ME. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen receptor beta expression in the rat cortex during aging. NeuroReport. 2011;22(9):428–432. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328346e1cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chakraborty TR, Ng L, Gore AC. Age-related changes in estrogen receptor β in rat hypothalamus: a quantitative analysis. Endocrinology. 2003;144(9):4164–4171. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poola I, Koduri S, Chatra S, Clarke R. Identification of twenty alternatively spliced estrogen receptor alpha mRNAs in breast cancer cell lines and tumors using splice targeted primer approach. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2000;72(5):249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ishunina TA, Swaab DF. Hippocampal estrogen receptor-alpha splice variant TADDI in the human brain in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89(2):187–199. doi: 10.1159/000158573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ishunina TA, Swaab DF. Estrogen receptor-α splice variants in the human brain. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2008;24(2):93–98. doi: 10.1080/09513590701705148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ishunina TA, Kruijver FPM, Balesar R, Swaab DF. Differential expression of estrogen receptor α and β immunoreactivity in the human supraoptic nucleus in relation to sex and aging. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2000;85(9):3283–3291. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.9.6826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ishunina TA, Fischer DF, Swaab DF. Estrogen receptor α and its splice variants in the hippocampus in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007;28(11):1670–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tollervey JR, Wang Z, Hortobágyi T, et al. Analysis of alternative splicing associated with aging and neurodegeneration in the human brain. Genome Research. 2011;21(10):1572–1582. doi: 10.1101/gr.122226.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mott NN, Pak TR. Characterisation of human oestrogen receptor beta (ERβ) splice variants in neuronal cells. Journal of Neuroendocrinology. 2012;24(10):1311–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Inoue S, Hoshino S-J, Miyoshi H, et al. Identification of a ovel isoform of estrogen receptor, a potential inhibitor of estrogen action, in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;219(3):766–772. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skipper JK, Young LJ, Bergeron JM, Tetzlaff MT, Osborn CT, Crews D. Identification of an isoform of the estrogen receptor messenger RNA lacking exon four and present in the brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(15):7172–7175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Price RH, Jr., Lorenzon N, Handa RJ. Differential expression of estrogen receptor beta splice variants in rat brain: identification and characterization of a novel variant missing exon 4. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 2000;80(2):260–268. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chu S, Fuller PJ. Identification of a splice variant of the rat estrogen receptor β gene. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1997;132(1-2):195–199. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(97)00133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu B, Leygue E, Dotzlaw H, Murphy LJ, Murphy LC, Watson PH. Estrogen receptor-β mRNA variants in human and murine tissues. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 1998;138(1-2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pak TR, Chung WCJ, Roberts JL, Handa RJ. Ligand-independent effects of estrogen receptor β on mouse gonadotropin-releasing hormone promoter activity. Endocrinology. 2006;147(4):1924–1931. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pak TR, Chung WCJ, Hinds LR, Handa RJ. Estrogen receptor-β mediates dihydrotestosterone-induced stimulation of the arginine vasopressin promoter in neuronal cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148(7):3371–3382. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-β isoforms: a key to understanding ER-β signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(35):13162–13167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang JM, Hou X, Adeosun S, et al. A dominant negative ERβ splice variant determines the effectiveness of early or late estrogen therapy after ovariectomy in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033493.e33493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chung WCJ, Pak TR, Suzuki S, Pouliot WA, Andersen ME, Handa RJ. Detection and localization of an estrogen receptor beta splice variant protein (ERβ2) in the adult female rat forebrain and midbrain regions. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2007;505(3):249–267. doi: 10.1002/cne.21490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Price RH, Jr., Butler CA, Webb P, Uht R, Kushner P, Handa RJ. A splice variant of estrogen receptor β missing exon 3 displays altered subnuclear localization and capacity for transcriptional activation. Endocrinology. 2001;142(5):2039–2049. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.5.8130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Y, Miksicek RJ. Identification of a dominant negative form of the human estrogen receptor. Molecular Endocrinology. 1991;5(11):1707–1715. doi: 10.1210/mend-5-11-1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Küppers E, Beyer C. Expression of estrogen receptor-α and β mRNA in the developing and adult mouse striatum. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;276(2):95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00815-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gundlah C, Kohama SG, Mirkes SJ, Garyfallou VT, Urbanski HF, Bethea CL. Distribution of estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) mRNA in hypothalamus, midbrain and temporal lobe of spayed macaque: continued expression with hormone replacement. Brain Research. Molecular Brain Research. 2000;76(2):191–204. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morishima Y, Murphy PJM, Li D-P, Sanchez ER, Pratt WB. Stepwise assembly of a glucocorticoid receptor·hsp90 heterocomplex resolves two sequential ATP-dependent events involving first hsp70 and then hsp90 in opening of the steroid binding pocket. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(24):18054–18060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dittmar KD, Pratt WB. Folding of the glucocorticoid receptor by the reconstituted hsp90-based chaperone machinery. The initial hsp90·p60·hsp70-dependent step is sufficient for creating the steroid binding conformation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(20):13047–13054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kang KI, Meng X, Devin-Leclerc J, et al. The molecular chaperone Hsp90 can negatively regulate the activity of a glucocorticosteroid-dependent promoter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(4):1439–1444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Unno K, Asakura H, Shibuya Y, Kaiho M, Okada S, Oku Naoto N. Increase in basal level of Hsp70, consisting chiefly of constitutively expressed hsp70 (Hsc70) in aged rat brain. Journals of Gerontology. Series A. 2000;55(7):B329–B335. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.7.b329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Olazabal UE, Pfaff DW, Mobbs CV. Sex differences in the regulation of heat shock protein 70 kDa and 90 kDa in the rat ventromedial hypothalamus by estrogen. Brain Research. 1992;596(1-2):311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91563-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pahlavani MA, Harris MD, Moore SA, Richardson A. Expression of heat shock protein 70 in rat spleen lymphocytes is affected by age but not by food restriction. Journal of Nutrition. 1996;126(9):2069–2075. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.9.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Heydari AR, Wu B, Takahashi R, Strong R, Richardson A. Expression of heat shock protein 70 is altered by age and diet at the level of transcription. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1993;13(5):2909–2918. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.5.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sabbah M, Kang K-II, Tora L, Redeuilh G. Oestrogen receptor facilitates the formation of preinitiation complex assembly: involvement of the general transcription factor TFIIB. Biochemical Journal. 1998;336(part 3):639–646. doi: 10.1042/bj3360639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wu S-Y, Thomas MC, Hou SY, Likhite V, Chiang C-M. Isolation of mouse TFIID and functional characterization of TBP and TFIID in mediating estrogen receptor and chromatin transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(33):23480–23490. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ghosh S, Thakur MK. Tissue-specific expression of receptor-interacting protein in aging mouse. Age. 2008;30(4):237–243. doi: 10.1007/s11357-008-9062-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Frasor J, Danes JM, Komm B, Chang KCN, Richard Lyttle C, Katzenellenbogen BS. Profiling of estrogen up- and down-regulated gene expression in human breast cancer cells: insights into gene networks and pathways underlying estrogenic control of proliferation and cell phenotype. Endocrinology. 2003;144(10):4562–4574. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Frasor J, Danes JM, Funk CC, Katzenellenbogen BS. Estrogen down-regulation of the corepressor N-CoR: mechanism and implications for estrogen derepression of N-CoR-regulated genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(37):13153–13157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502782102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]