Abstract

Objectives

To compare sexual orientation group differences in the longitudinal development of alcohol use behaviors during adolescence.

Design

Community-based prospective cohort study.

Setting

Self-reported questionnaires.

Participants

A total of 13450 Growing Up Today Study participants (79.7% of the original cohort) aged 9 to 14 years at baseline in 1996 were followed for over seven years.

Main Exposure

Self-reported sexual orientation classified as heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or lesbian/gay.

Main Outcome Measures

Age of alcohol use initiation, any past-month drinking, number of alcohol drinks usually consumed, and number of binge drinking episodes in the past year.

Results

Compared to heterosexuals, youth reporting any minority sexual orientation reported initiating alcohol use at younger ages. Greater risk of alcohol use was consistently observed for mostly heterosexual males and females and for bisexual females, whereas gay and bisexual males and lesbians reported elevated levels of alcohol use on only some indicators. Gender was an important modifier of alcohol use risk; mostly heterosexual and bisexual females exhibited the highest relative risk. Younger age of alcohol use initiation among minority sexual orientation participants significantly contributed to their elevated risk for binge drinking.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that disparities in alcohol use among youth with a minority sexual orientation emerge in early adolescence and persist into young adulthood. Healthcare providers should be aware that adolescents with a minority sexual orientation are at greater risk for alcohol use.

Adolescent alcohol use is a significant public health concern that contributes to preventable morbidity and mortality.1 Adverse consequences include alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes; unintentional injuries; increased risk for suicide, homicide, and assault; increased likelihood of engaging in high-risk sexual behaviors; and diminished academic performance.2 Evidence suggests that heavy alcohol use during adolescence has deleterious and enduring effects on brain development and impairs neurocognitive functioning.3 Exposure to alcohol during adolescence, as opposed to during adulthood, may be especially harmful because the adolescent brain is actively undergoing development.4

Not all adolescent populations share equivalent risk for alcohol use. Involvement in alcohol use is increasingly recognized as disproportionately affecting the population of adolescents who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual or report same-sex sexual attractions and/or relationships. These youth are referred to in the literature as “sexual minority.” Research using school-based samples indicate that sexual minority adolescents are more likely than heterosexuals to report younger age of alcohol use initiation,5 frequent alcohol use including daily use,6–8 as well as heavy alcohol use (e.g., binge drinking).7, 9 Some research suggests that bisexuals may display the highest risk for alcohol use9–11 and that there may be gender differences in alcohol use with disparities accentuated for sexual minority females as compared to males.12, 13 But most studies did not formally test for statistical interactions between sexual orientation and gender in estimating alcohol use.14 Further investigations to identify how gender and sexual orientation may be related to risk for alcohol involvement is warranted.

Prior research demonstrating that sexual minority youth are at high risk for consuming alcohol has mostly been cross-sectional.5–8, 13, 15 A recent meta-analysis on sexual orientation and substance use underscored the dearth of research comparing trajectories of substance use over time in sexual minority and heterosexual youth.14 Longitudinal studies of adolescents are crucial because adolescence is the developmental period when alcohol use is commonly initiated and when behaviors influencing patterns of use in adulthood are established.16 Consequently, we undertook the current study to estimate and compare the development of alcohol use behaviors over time in a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents who reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or lesbian/gay.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Self-administered questionnaire data are from the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), a United States community-based longitudinal cohort study of 9039 female and 7843 male children of women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II.17 Approximately 93% of the cohort identified as non-Hispanic white. After obtaining maternal consent, baseline questionnaires were mailed in 1996 to potential participants between ages nine and 14 years. The children were invited to return a completed questionnaire if they agreed to participate in the study. Follow-up data collection occurred annually from 1997 through 2001 and in 2003. Because recruitment occurred at the family level, some participants are siblings. Additional information about GUTS methodology is available elsewhere.18 Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained by Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Included in the present analysis are 13450 participants (7750 females and 5700 males) who provided information on sexual orientation and alcohol use in one or more waves between years 1997 through 2003. The analysis sample represents 79.7% of the original GUTS cohort. Compared to participants excluded from the analysis, participants included in analysis are more likely to be female (85.7% of females included; 72.7% of males included; P<.0001) and younger (mean baseline age: 11.5 versus 11.8 years; P<.0001). Participants residing in the Western region of the United States are more likely to be in the analysis (83.3% included) compared to participants residing in the Midwest (79.5% included; P=.0003) and the Northeast (78.7% included; p<.0001). No differences in participation rates were found with respects to race/ethnicity (P=.77), baseline reports of past-year monthly alcohol use (P=.20), or baseline current smoking status (P=.23) when comparing respondents included versus excluded from analysis. Among the analysis sample, 51.1% of participants responded to all six waves occurring between 1997 and 2003, 20.7% responded to five waves, 13.8% responded to four waves, 8.8% responded to three waves, 4.0% responded to two waves, and 1.5% responded to one wave.

Measures

Sexual Orientation

A sexual orientation measure tapping the domains of attraction and identity was included in waves 1999, 2001, and 2003. The question, adapted from the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey,19 asks participants, “Which one of the following best describes your feelings?” Response options are completely heterosexual (attracted to persons of the opposite sex); mostly heterosexual; bisexual (equally attracted to men and women); mostly homosexual; completely homosexual (gay/lesbian, attracted to persons of the same sex); and not sure. We combined mostly homosexual and completely homosexual responses into a single lesbian/gay category due to their small sample sizes.

Outcome Measures of Alcohol Use

Four alcohol use questions adapted from the Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey were included in the study.20 Age of first whole alcoholic drink, was assessed on five survey waves from 1997 through 2001. Participants were asked to indicate whether and at what age they first had a whole drink of alcohol. A drink was defined as “a whole glass, can, or bottle of beer; a whole glass of wine; or a whole ‘mixed drink’ or shot of liquor.” Response options ranged from seven years or younger to the maximum age of participants at each wave; therefore, the variable ranged from 7 years or younger (coded as 7) to 21 years. Any drinking in the past month, coded as a binary variable, was assessed on five waves from 1997 through 2001. Number of drinks usually consumed, assessed on six waves from 1997 through 2003 was indexed by querying participants, “When you drink alcohol, how much do you usually drink at one time?” Response options for this ordinal variable range from zero to six or more drinks (coded as 6). Lastly, on five waves from 1998 through 2003, participants were asked how often they engaged in binge drinking in the past year. Binge drinking was defined as drinking five or more alcohol drinks over a few hours—except for among girls in 2001 and 2003, when it was defined as drinking four or more alcohol drinks over a few hours. Response options are none, one, two, 3–5, 6–8, 9–11, and 12 or more times. In analyses, we assigned the midpoint value to categories with ranges (e.g., 4 for category 3–5) and the value 13 to the “12 or more” category.

Other Covariates

Potential confounders included are age when questionnaire was returned (grouped into categories of 10–13 years, 14–15, 16–17, 18–19, and 20–23), race/ethnicity self-reported at baseline (coded as non-Hispanic white, other, or missing), region of residence (coded as Midwest, Northeast, South, West, and other [includes international and military addresses]), and any report of an adult living in the household who drinks alcohol (coded as yes, no, or missing).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were stratified on gender due to differences commonly found in alcohol use among males and females.21 We also developed models that included both genders and gender-by-sexual-orientation interaction terms to test for effect measure modification by gender in the relationship between sexual orientation and alcohol use.

Longitudinal descriptive analyses were conducted to examine age-related trajectories in alcohol use across sexual orientation groups. Longitudinal multivariable statistical methods varied by outcome. To model age at first whole drink across sexual orientations, we used proportional hazards survival analysis. To adjust the standard errors to account for non-independent sibling clusters, we used the robust sandwich covariance matrix approach.22

To model longitudinal reports of number of drinks usually consumed and number of past-year binge drinking episodes, we used multivariable generalized estimating equations (GEE) repeated measures linear regression to account for the non-independence of the repeated measures within an individual and the sibling clusters.23 These models estimate the average effect size over the repeated measures. To model any past-month alcohol use, we used the modified Poisson method to estimate risk ratios with GEE adjustment for repeated measures and sibling clusters.24 All multivariable statistical models adjust for age, race/ethnicity, region of residence, and the presence of an adult in the household who drinks alcohol. The heterosexual group served as the referent group. Statistical significance was set at the p<.05 criteria.

Multivariable GEE repeated measures linear regression was used to examine if younger age of alcohol initiation (defined as age 14 years or younger) contributed to sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal binge drinking. These analyses were restricted to individuals for whom information on whether or not they initiated alcohol use before age 14 years was available.

Handling of sexual orientation, age, and region of residence varied by model type. In the survival analyses, baselines of age and region of residence were used. We used a hierarchical coding scheme to classify sexual orientation over time into a single variable composed of four mutually exclusive categories. Individuals who indicated that they were “mostly homosexual” or “completely homosexual” on any of the three assessments of sexual orientation (1999, 2001, and 2003) were coded as lesbian/gay; individuals who indicated that they were “bisexual” at any wave, but never “mostly homosexual” or “completely homosexual” were coded as bisexual; individuals who indicated that they were “mostly heterosexual” on any wave, but never “bisexual”, “mostly homosexual”, or “completely homosexual” were coded as mostly heterosexual; and individuals who indicated only that they were “completely heterosexual” were coded as heterosexual. A sensitivity analysis to examine how results changed when using first or last report of sexual orientation confirmed similar results, suggesting that this coding method aptly depicts associations in the data.

In the GEE repeated measures regressions all variables in the model were measured concurrently whenever possible. Age group and region of residence were updated at each assessment. Sexual orientation was also updated and allowed to vary by wave. Sexual orientation reported in 1999 was assigned to the 1997 and 1998 waves and sexual orientation reported in 2001 was assigned to the 2000 wave because sexual orientation was not assessed in 1997, 1998, or 2000. For those not responding to the 2001 wave, sexual orientation reported in 1999 was used for the 2000 wave. For both sexual orientation coding methods, findings related to individuals “not sure” of their sexual orientation are excluded due to instability in estimation because these individuals are concentrated in the youngest age categories. This includes 10 males and 26 females for survival analyses and 279 male observations and 516 female observations for repeated measures analyses.

RESULTS

Gender-specific distributions of sexual orientation by hierarchical coding used in survival analysis and by observations included in the repeated measures analyses are shown in Table 1. Overall, 8.5% of males and 16.1% of females reported a minority sexual orientation (i.e., mostly heterosexual, bisexual, or gay/lesbian). When comparing gender differences in the distribution of sexual orientation based on hierarchical coding, females were significantly more likely to have identified as bisexual, mostly heterosexual, or unsure, whereas males were more likely to have identified as gay (P<.0001).

Table 1.

Distribution of sexual orientation by hierarchical coding and by repeated measures observations among male and female adolescent participants in the Growing Up Today Study (1997–2003)

| Males

|

Females

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Hierarchical Sexual Orientation Coding | ||||

| Total Number of Subjects | 5700 | 100 | 7750 | 100 |

| Heterosexual | 5206 | 91.3 | 6474 | 83.5 |

| Mostly Heterosexual | 340 | 6.0 | 980 | 12.7 |

| Bisexual | 56 | 1.0 | 212 | 2.7 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 88 | 1.5 | 58 | 0.8 |

| Not Sure | 10 | 0.2 | 26 | 0.3 |

| Repeated Measures Observations of Sexual Orientation | ||||

| Total Number of Observations | 23850 | 100 | 36402 | 100 |

| Heterosexual | 22308 | 93.5 | 32489 | 89.3 |

| Mostly Heterosexual | 895 | 3.8 | 2785 | 7.7 |

| Bisexual | 138 | 0.6 | 502 | 1.4 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 230 | 1.0 | 110 | 0.3 |

| Not Sure | 279 | 1.2 | 516 | 1.4 |

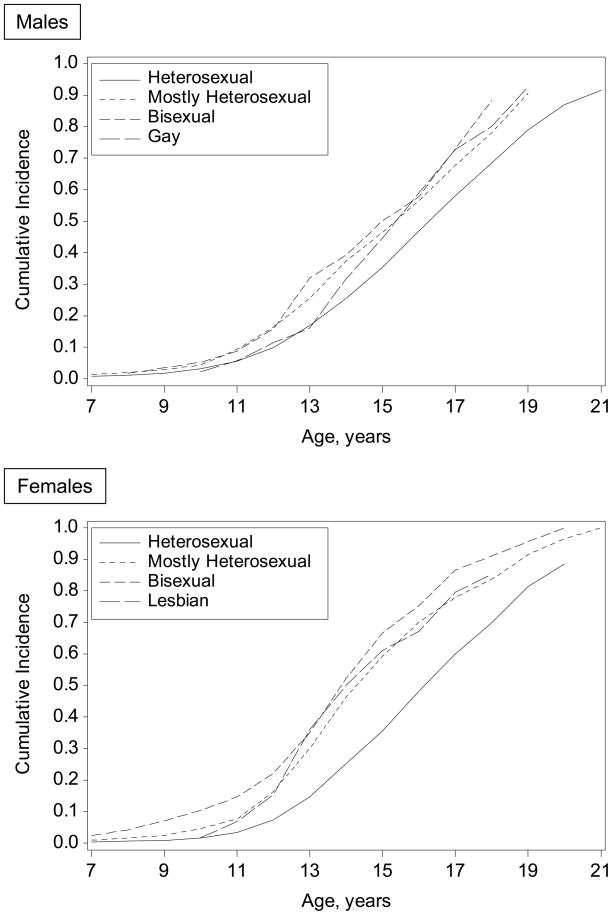

Longitudinal patterns of alcohol use by sexual orientation

Gender-specific cumulative incidence plots comparing age of initiation of alcohol use by sexual orientation are displayed in Figure 1. Males and females reporting a minority sexual orientation indicated a younger age at first consuming a whole alcoholic drink as compared to their same-gender heterosexual counterparts. After controlling for covariates, males classified as mostly heterosexual (hazard ratio [HR], 1.35; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.09–1.56) and bisexual (HR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.09–2.30) reported a younger age at first consuming a whole drink as compared to heterosexual males. Gay males also reported a younger age at first whole drink consumption relative to heterosexual males, but findings were not statistically significant (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.96–1.54). Among females, mostly heterosexual (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.49–1.77), bisexual (HR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.72–2.38), and lesbian (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.14–2.43) participants were more likely than heterosexuals to report a younger age at consuming their first whole drink.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of age of first whole alcoholic drink by sexual orientation among male and female participants in the Growing Up Today Study (1997–2003)

Gender-specific plots of age trajectories of prevalence of any past-month drinking and means for number of drinks usually consumed and number of past-year binge drinking episodes by sexual orientation are shown in Figure 2. As expected, regardless of sexual orientation, we observed increases in alcohol use as participants aged. Table 2 presents results of multivariable repeated regression analyses estimating relative risks (RR) for any past-month drinking and unstandardized regression coefficients (β) for number of drinks usually consumed on an occasion and number of binge drinking episodes in the past year. Mostly heterosexual males and females and bisexual females reported greater alcohol use on all three outcomes as compared to their same-gender heterosexual peers. Bisexual males reported greater alcohol use than heterosexual males, but associations were statistically significant only for any past-month drinking. Gay males reported consuming a larger number of drinks as compared to heterosexual males. Compared to heterosexual females, lesbians reported a greater number of drinks usually consumed and binge drinking episodes, although the latter did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2.

Alcohol use across age by sexual orientation among male and female participants in the Growing Up Today Study (1997–2003)

Table 2.

Results of multivariable generalized estimating equation repeated measures regression for alcohol use outcomes among male and female participants in the Growing Up Today Study (1997–2003)

| Characteristic | Males

|

Females

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Past Month Drinkinga (19087 obs) | Number of Drinks Usually Consumedb (21370 obs) | Number of Binge Drinking Episodesb (19629 obs) | Any Past Month Drinkinga (28999 obs) | Number of Drinks Usually Consumedb (33562 obs) | Number of Binge Drinking Episodesb (29971 obs) | |||||||

| RR | 95% CI | β | P-value | β | P-value | RR | 95% CI | β | P-value | β | P-value | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||||||||

| Heterosexual | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Mostly Heterosexual | 1.22 | 1.06, 1.42 | 0.32 | <.0001 | 0.39 | .02 | 1.36 | 1.28, 1.46 | 0.40 | <.0001 | 0.82 | <.0001 |

| Bisexual | 1.54 | 1.18, 2.01 | 0.19 | .29 | 0.65 | .18 | 1.55 | 1.34, 1.78 | 0.82 | <.0001 | 1.65 | <.0001 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 1.24 | 0.96, 1.61 | 0.58 | .006 | 0.64 | .16 | 1.11 | 0.79, 1.56 | 0.50 | .03 | 0.83 | .12 |

Relative risks (RR) estimated by modified Poisson regression.

Regression coefficients (β) estimated by linear regression.

Note: Models adjust for age group, race/ethnicity, region of residence, and household adult alcohol drinking.

Interactions of gender and sexual orientation

In some instances, we observed a gender-by-sexual-orientation statistical interaction indicating that differences in alcohol use between sexual minority and heterosexual females were larger than differences observed between sexual minority and heterosexual males. A gender-by-sexual orientation interaction for younger age at first whole drink was statistically significant for mostly heterosexual females (HRinteraction, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.00–1.40), but not for bisexual females (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.84–1.90) or lesbians (HR, 1.54; 95% CI, 0.85–2.08).

A gender-by-sexual-orientation interaction for greater number of drinks usually consumed was observed for bisexual females (βinteraction, 0.54; P=.01). A gender-by-sexual-orientation interaction for greater number of binge drinking episodes was observed for mostly heterosexual females (β, 0.46; P=.02) and suggestive for bisexual females (β, 0.86; P=.12).

Contributions of younger age of alcohol initiation to binge drinking patterns

Younger age of alcohol initiation among sexual minority participants appeared to explain some of their excess risk for longitudinal alcohol use. Among males, when age of alcohol use initiation was entered into the multivariable repeated measures regression analyses predicting binge drinking, the regression coefficients attenuated among mostly heterosexuals (from β, 0.37; P=.03 to β, 0.19; P=.25), bisexuals (from β, 0.70; P=.15 to β, 0.43; P=.37), and gay males (from β, 0.71; P=.13 to β, 0.49; P=.25). Among females, entering age of alcohol use initiation into the regression models estimating differences in binge drinking also resulted in the coefficients attenuating for mostly heterosexuals (from β, 0.81; P<.0001 to β, 0.50; P<.0001), bisexuals (from β, 1.68; P<.0001 to β, 1.27; P<.0001), and lesbians (from β, 0.74; P=.17 to β, 0.36; P=.47).

COMMENT

The results of this prospective study provide further evidence that some sexual minority youth are at disproportionate risk for using alcohol. Our findings extend the literature5–8, 13, 15 by estimating sexual orientation group differences across multiple assessments during the critical developmental period when substance use patterns are generally established. Furthermore, sexual orientation identity develops during adolescence and young adulthood and is expected to be more fluid during this period.25 Our estimates were able to account for this variability by updating sexual orientation and allowing it to change across waves.

In our study, mostly heterosexual and bisexual males indicated a younger age of alcohol use initiation. Sexual minority males also reported heavier drinking (as indexed by number of drinks usually consumed on an occasion and binge drinking episodes), but findings were significant only for mostly heterosexual and gay males. Findings for bisexual males should be interpreted with caution due to lower statistical power.

Differences between heterosexual and sexual minority subgroups in longitudinal alcohol use were larger in females than males; findings were strongest for mostly heterosexual and bisexual females. A meta-analysis of sexual orientation and adolescent substance use made similar conclusions.14 A prior cross-sectional analysis of GUTS data collected in 1999 when participants were in early to middle adolescence also found that gender modified associations between sexual orientation and alcohol use.13 The current analysis suggests that alcohol use disparities among sexual minority females may extend beyond early and middle adolescence and into later adolescence.

The alcohol consumption patterns of the sexual minority female participants in GUTS are concerning because females are more susceptible than males to alcohol-related health problems at any degree of alcohol use.26 Females are more vulnerable to alcohol’s negative effects due to increased bioavailability of alcohol, which is linked to increased risk of liver damage.27 Females experience more acute sedation and memory deficits and are more likely to “blackout” (i.e., experience amnesia for the events of any part of a drinking episode, without loss of consciousness28) compared to males who drink comparable amounts of alcohol.29

Another concerning finding of this study is the younger age of alcohol use initiation reported by the sexual minority participants relative to their same-gender heterosexual peers. Younger onset of adolescent alcohol use has been linked to greater risk of violence, injury, drinking and driving, and substance abuse.30–32 One study found that respondents who began drinking at younger ages were more likely to meet criteria for lifetime DSM-IV alcohol dependence.33 Furthermore, participants meeting diagnostic criteria for lifetime alcohol dependence who initiated alcohol use at younger ages had a longer duration of a dependence episode than individuals with a history of dependence who initiated alcohol use at later ages.33 In our study, younger age of alcohol use initiation among the sexual minority participants was linked to their higher frequency of binge drinking when compared to heterosexual participants. Binge drinking is a marker of heavy alcohol use associated with alcohol dependence.34 Studies in adults suggest that sexual minority women are more likely than heterosexual women to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder; sexual orientation differences observed in men are less pronounced for alcohol use disorders, but sexual minority men may be more likely than heterosexual men to experience drug use disorders.35–40 Further research is needed to determine if younger age of alcohol use initiation contributes to increased risk for substance disorders among individuals with a minority sexual orientation. Research is also needed to understand the reasons why sexual minority youth begin drinking at younger ages.

Two reasons have been considered to explain higher alcohol use among sexual minority youth. First, these youth may use alcohol to cope with gay-related stress (i.e., internal and external stressors associated with stigmatization of homosexuality),41–43 or social anxiety associated with entry into the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community.44 This explanation is consistent with the self medication theory in which individuals use alcohol or other substances to alleviate negative feelings associated with psychiatric morbidity.45 Second, socializing in the gay community, even for youth, may still occur primarily in settings where substances are prevalent (e.g., bars, community pride events), at least initially until alternative settings are identified.44, 46

Limitations

Several potential limitations of the study should be noted. GUTS is not a representative probability sample and participants are children of women with nursing degrees, which precludes generalizability of findings. However, the distribution of sexual orientation in GUTS is comparable to other youth cohort studies using a similar measure of sexual orientation.47, 48 Because GUTS participants are predominantly non-Hispanic white we were unable to examine possible racial/ethnic differences. One potential source of bias is that information collected is based on self-reports. The accuracy of adolescent self-reports is influenced by multiple cognitive (e.g., question comprehension, retrieval of information) and situational (e.g., privacy, confidentiality) factors.49 The self-administered questionnaire format used in GUTS has been shown to result in higher rates of reported substance use than the interview format in adolescents.49 Furthermore, our data were gathered annually or biannually and are presumably less likely to be influenced by recall bias compared to data gathered retrospectively in adulthood.

Another possible source of bias in longitudinal studies is loss to follow up. Although it is not known how attrition may bias estimates, the sample included responses from 79.7% of the original GUTS cohort and the majority of these individuals provided responses over multiple waves. Also, attrition was not associated with baseline reports of alcohol or tobacco use. Finally, because only one item taping attraction/identity was used to assess sexual orientation, this study was unable to account for other dimensions of sexual orientation (e.g., behavior) and to determine how minority sexual orientation developmental factors (e.g., timing, stage) are related to alcohol use. Despite the limitations, this cohort study adds to the body of knowledge on sexual orientation and the development of alcohol use because information is based on seven years of data collection across multiple waves of assessment during the critical periods of adolescence and young adulthood.

Implications

Individuals working with adolescents (e.g., healthcare providers, teachers, parents) should be aware that youth who report same-sex attractions regardless of how they identify, including youth describing themselves as mostly heterosexual, may be at high risk for alcohol use at relatively young ages. It is critical that interventions targeting these youth be developed, implemented, and tested for efficacy for the purpose of delaying alcohol initiation and reducing alcohol use. Focusing on sexual minority adolescent males is important because alcohol use contributes to greater sexual risk taking and HIV risk.50–52 The necessity to reduce or eliminate alcohol-related problems demands interventions targeting this population beginning in early adolescence, if not earlier.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Growing Up Today Study for their contributions to this study. We also thank the members of the Growing Up Today Study research team whose dedication made this study possible.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Drs. Corliss, Austin, Wypij and Rosario contributed to study concept and design. Dr. Austin contributed to acquisition of data, obtaining funding, and study supervision. Drs. Corliss and Austin contributed to drafting of the manuscript and administrative, technical, or material support. All authors contributed to data analysis and interpretation and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Drs. Corliss and Wypij and Ms. Fisher contributed to statistical analysis.

References

- 1.United States Department of Health and Human Services. With Understanding and Improving Health and Objectives for Improving Health. 2. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; Nov, 2000. Healthy People 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonnie RJ, O’Connell ME, editors. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine, editor. Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sher L. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in studies of neurocognitive effects of alcohol use on adolescents and young adults. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2006;18(1):3–7. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2006.18.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark DB, Thatcher DL, Tapert SF. Alcohol, psychological dysregulation, and adolescent brain development. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(3):375–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey SJ, DuRant RH. The association between health risk behaviors and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bontempo DE, D’Augelli AR. Effects of at-school victimization and sexual orientation on lesbian, gay, or bisexual youths’ health risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(5):364–374. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faulkner AH, Cranston K. Correlates of same-sex sexual behavior in a random sample of Massachusetts high school students. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(2):262–266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rostosky SS, Owens GP, Zimmerman RS, Riggle ED. Associations among sexual attraction status, school belonging, and alcohol and marijuana use in rural high school students. J Adolesc. 2003;26(6):741–751. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Russell ST, Driscoll AK, Truong N. Adolescent same-sex romantic attractions and relationships: implications for substance use and abuse. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(2):198–202. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.2.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgard SA, Cochran SD, Mays VM. Alcohol and tobacco use patterns among heterosexually and homosexually experienced California women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robin L, Brener ND, Donahue SF, Hack T, Hale K, Goodenow C. Associations between health risk behaviors and opposite-, same-, and both-sex sexual partners in representative samples of Vermont and Massachusetts high school students. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(4):349–355. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell ST. Substance Use and Abuse and Mental Health Among Sexual-Minority Youths: Evidence From Add Health. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual orientation and mental health: Examining identity and development in lesbian, gay, and bisexual people. Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual psychology. 2006. pp. 13–35. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziyadeh NJ, Prokop LA, Fisher LB, et al. Sexual orientation, gender, and alcohol use in a cohort study of U.S. adolescent girls and boys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;87(2–3):119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103(4):546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orenstein A. Substance use among gay and lesbian adolescents. J Homosex. 2001;41(2):1–15. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n02_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zucker RA. Alcohol use and the alcohol use disorders: A developmental-biopsychosocial systems formulation covering the life course. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2006. pp. 620–656. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich-Edwards JW, Spiegelman D, Garland M, et al. Physical activity, body mass index, and ovulatory disorder infertility. Epidemiology. 2002;13(2):184–190. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, et al. Overweight, weight concerns, and bulimic behaviors among girls and boys. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38(6):754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Remafedi G, Resnick M, Blum R, Harris L. Demography of sexual orientation in adolescents. Pediatrics. 1992;89(4 Pt 2):714–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massachusetts Department of Education/Bureau of Student Development and Health. 1992 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Malden, MA: Massachusetts Department of Education; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keyes KM, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Evidence for a closing gender gap in alcohol use, abuse, and dependence in the United States population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;93(1–2):21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee E, Wei L, Amato D. Cox-type regression analysis for large numbers of small groups of correlated failure time observations. In: Klein JP, Goel PK, editors. Survival Analysis: State of the Art. Vol. 211. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1992. pp. 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1996;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J. Models of development: Understanding risk in adolescence. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1995;25 (Suppl):18–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antai-Otong D. Women and alcoholism: Gender-related medical complications: Treatment considerations. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2006;17:33–45. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baraona E, Abittan CS, Dohmen K, et al. Gender differences in pharmacokinetics of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(4):502–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin DW, Crane JB, Guze SB. Alcoholic “blackouts”: A review and clinical study of 100 alcoholics. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:191–198. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mumenthaler MS, Taylor JL, O’Hara R, Yesavage JA. Gender differences in moderate drinking effects. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(1):55–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuRant RH, Smith JA, Kreiter SR, Krowchuk DP. The relationship between early age of onset of initial substance use and engaging in multiple health risk behaviors among young adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):286–291. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruber E, DiClemente RJ, Anderson MM, Lodico M. Early drinking onset and its association with alcohol use and problem behavior in late adolescence. Prev Med. 1996;25(3):293–300. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitkanen T, Lyyra AL, Pulkkinen L. Age of onset of drinking and the use of alcohol in adulthood: a follow-up study from age 8–42 for females and males. Addiction. 2005;100(5):652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woerle S, Roeber J, Landen MG. Prevalence of alcohol dependence among excessive drinkers in New Mexico. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(2):293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cochran SD, Mays VM. Relation between psychiatric syndromes and behaviorally defined sexual orientation in a sample of the US population. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(5):516–523. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cochran SD, Ackerman D, Mays VM, Ross MW. Prevalence of non-medical drug use and dependence among homosexually active men and women in the US population. Addiction. 2004;99(8):989–998. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drabble L, Midanik LT, Trocki K. Reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems among homosexual, bisexual and heterosexual respondents: results from the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(1):111–120. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gilman SE, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Hughes M, Ostrow D, Kessler RC. Risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals reporting same-sex sexual partners in the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(6):933–939. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.6.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandfort TGM, de Graaf R, Bijl RV, Schnabel P. Same-sex sexual behavior and psychiatric disorders: Findings from the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):85–91. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction. 2001;96(11):1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):38–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosario M, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Reid H. Gay-related stress and its correlates among gay and bisexual male adolescents of predominantly Black and Hispanic background. Journal of Community Psychology. 1996;24(2):136–159. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosario M, Hunter J, Gwadz M. Exploration of substance use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth: Prevalence and correlates. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12(4):454–476. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Predictors of substance use over time among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: an examination of three hypotheses. Addict Behav. 2004;29(8):1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trocki KF, Drabble L, Midanik L. Use of heavier drinking contexts among heterosexuals, homosexuals and bisexuals: results from a National Household Probability Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(1):105–110. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Prevalence and stability of sexual orientation components during adolescence and young adulthood. Arch Sex Behav. 2007;36(3):385–394. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Austin SB, Roberts AL, Corliss HL, Molnar BE. “Mostly heterosexual” and heterosexual young women: Sexual violence victimization history and sexual risk indicators in a community-based urban cohort. Am J Public Health. 2007 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.099473. ;[Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health risk. J Adolesc Health. 2003;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Celentano DD, Valleroy LA, Sifakis F, et al. Associations between substance use and sexual risk among very young men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(4):265–271. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187207.10992.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Read TR, Hocking J, Sinnott V, Hellard M. Risk factors for incident HIV infection in men having sex with men: a case-control study. Sex Health. 2007;4(1):35–39. doi: 10.1071/sh06043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaudrey J, Raymond HF, Chen S, Hecht J, Ahrens K, McFarland W. Indicators of use of methamphetamine and other substances among men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2003–2006. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(1):97–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]