Abstract

Background

Many studies have attempted to correlate radiographic acromial characteristics with rotator cuff tears, but the results have not been conclusive. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between rotator cuff disease and development of symptoms with different radiographic acromial characteristics including shape, index, and presence of a spur.

Materials and Methods

The records of 216 patients enrolled in an ongoing prospective, longitudinal study investigating asymptomatic rotator cuff tears were reviewed. All patients underwent standardized radiographic evaluation, clinical evaluation, and shoulder ultrasonography at regularly scheduled surveillance visits. Three blinded observers reviewed all radiographs to determine the acromial morphology, presence and size of an acromial spur, and acromial index. These findings were analyzed to determine an association with the presence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

Results

The three observers demonstrated poor agreement for acromial morphology, substantial agreement for the presence of an acromial spur, and excellent agreement for acromial index (kappa= 0.41, 0.65, and 0.86 respectively). The presence of an acromial spur was highly associated with the presence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear (p=0.003) even after adjusting for age. No association was found between acromial index and rotator cuff disease (p=0.92).

Conclusion

The presence of an acromial spur is highly associated with the presence of a full-thickness rotator cuff tear in both the symptomatic and asymptomatic patient. The acromial morphology classification system is an unreliable method to assess the acromion. The acromial index shows no association with the presence of rotator cuff disease.

Keywords: Rotator cuff, Acromial spur, acromial morphology, acromial index

Introduction

Controversy still remains regarding the role of the acromion in rotator cuff disease. Neer described the pathologic interaction of the acromion and the rotator cuff in so called “impingement syndrome”. He stated that the anterior third of the acromion and coracoacromial ligament abutted against the tendinous portion of the rotator cuff leading to rotator cuff tearing over time25. Since his findings in 1972, many other authors have found a close relationship between the radiographic appearance of the acromion and rotator cuff disease5,9,12,22,40. Codman, on the other hand, believed that acromial changes were secondary to degeneration of the rotator cuff itself and that initiation of a rotator cuff tear was an intrinsic process8. This mechanism of disease progression has been further validated by investigations showing poor vascularity, altered biology, and inferior mechanical properties of the aging rotator cuff2,7,11,14,18,33,38. Nevertheless, acromioplasty continues to be one of the most common orthopaedic procedures performed in the United States39.

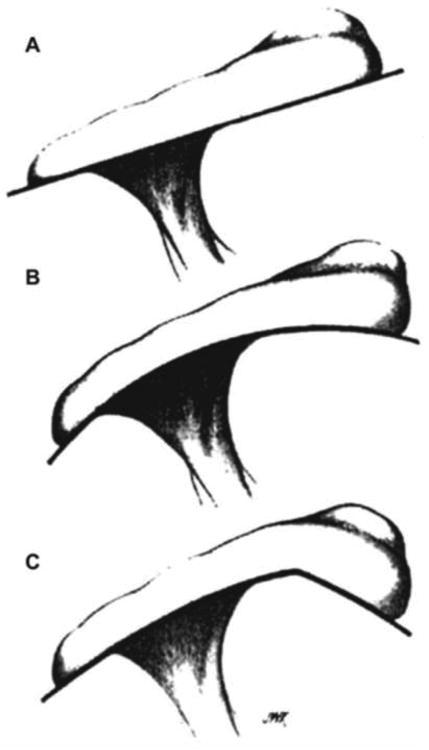

The traditional method of classifying the acromion is based on the shape of its undersurface. First described by Bigliani in 1986, the acromion can be classified as Type I (flat), Type II (curved), or Type III (hooked)4 when viewed in the sagittal plane. There were many studies that showed a close correlation of type III acromions with rotator cuff disease5,9,20,40. However, the poor interobserver reliability using this classification system and the difficulty in standardizing radiographs has brought significant question to the utility of this measurement6,15,27,41. Despite mounting controversial evidence, acromial morphology classification is still widely used in clinical practice and plays a large role in the consideration for acromioplasty.

Another acromial characteristic that has been implicated in the rotator cuff disease process is acromial spur formation. Neer described a traction spur at the anterior acromion along the coracoacromial ligament in stage III impingement syndrome and several other studies have corroborated Neer's initial findings28,29,30. A recent study by Ogawa et al using a combination of control patients, operatively treated patients, and cadaveric subjects showed a close association of acromial spurs with rotator cuff disease. Despite these findings, the interobserver reliability and general applicability of this measurement is still unknown.

Recently Nyffeler et al described a new acromial measurement to assess the amount of lateral acromial extension (acromial index)27. They found that the acromial index was closely associated with rotator cuff disease and provide a biomechanical theory of how lateral acromial extension can alter the deltoid muscle vector leading to excessive forces on the rotator cuff insertion. This novel measurement tool requires further investigation and has yet to be incorporated into the mainstream of rotator cuff evaluation.

Despite numerous investigations, the role of the acromion in rotator cuff disease continues to be an enigma and theories of intrinsic cuff degeneration have challenged the classic teachings of subacromial impingement as a primary etiology of rotator cuff disease. In order to progress our understanding of rotator cuff disease, further investigation of the radiographic characteristics of the acromion and their potential relationships to rotator cuff disease is needed. We also sought to determine what effect acromial characteristics would have on the development of pain in an asymptomatic patient with a rotator cuff tear as this has not been previously investigated. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine the relationship between rotator cuff disease and development of symptoms with different radiographic acromial characteristics including shape, index, and presence of an acromial spur.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

Data for this investigation was obtained as a separate, specific aim of an ongoing prospective, longitudinal study regarding asymptomatic rotator cuff tears. To be included into this prospective study, patients had to have (1) presented for bilateral shoulder ultrasonography at our institution for investigation of unilateral shoulder pain secondary to rotator cuff disease, (2) been discovered to have a rotator cuff tear (partial or full-thickness) in the asymptomatic shoulder, (3) no history of trauma (fall, motor-vehicle accident, heavy lifting episode or shoulder dislocation) to either shoulder and remained free of injury for the study duration. Patients found to have a rotator cuff tear on the asymptomatic shoulder were enrolled in a longitudinal, observational cohort. Also, subjects with an intact rotator cuff on the asymptomatic side were recruited to serve as a control group. Exclusion criteria were (1) pain in the asymptomatic shoulder at the time of study enrollment, (2) previous surgery on either shoulder, (3) inflammatory arthropathy, (4) glenohumeral osteoarthritis, (5) previous shoulder trauma, (6) use of upper extremity for weight bearing. At the time of this study, 250 patients had been enrolled into this cohort. All patients underwent annual surveillance including clinical interview, examination, ultrasonography, and standardized radiographs. Patients were deemed to have become “symptomatic” if (1) shoulder pain on visual analog scale was 3 or greater for at least six weeks, (2) pain level was considered greater than normally experienced as a part of daily living, (3) pain required the use of medications such as narcotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, or (4) pain that prompted a visit to a physician.

Investigational review board approval was obtained for review of medical records. Of the 250 subjects in this database, 216 were used for analysis in this study. Twenty five shoulders were excluded due to poor quality radiographs, five shoulders did not obtain adequate radiographs, and four shoulders were excluded because radiographs and sonograms were performed greater than 12 weeks apart. The most recent surveillance visit with complete clinical, radiographic, and sonographic data was used for analysis. Hence, this study employed a cross-sectional analysis of all patients at one given time point and did not investigate temporal changes seen in each subject over the course of surveillance. The most recent surveillance visit was chosen for analysis so as to include as many patients that have become symptomatic as possible.

Ultrasonography

The ultrasonographic examinations were performed by one of three musculoskeletal radiologists with extensive experience in the use of high-resolution ultrasound for evaluation of pathological conditions of the shoulder. Ultrasound is used as the primary modality of screening for rotator cuff disease at our institution and has been validated as an accurate means to detect rotator cuff tears34,32,35. All patients underwent standardized bilateral shoulder examinations as previously described34. Ultrasounds were performed in real time with the use of one of three different sonographic machines (ATL HDI 5000- Phillips Healthcare, Andover, MA, USA; Elegra- Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, PA, USA; and Antares- Siemens Healthcare, Malvern, PA, USA). Rotator cuff tears were assessed and measured using four parameters: 1) tear width (anterior to posterior), 2) tear length (lateral to medial tendon retraction), 3) distance from biceps tendon to anterior margin of tear, and 4) distance from biceps to posterior margin of tear. All measurements were made in real time by the examining radiologist.

Radiographic Analysis

All patients enrolled in the longitudinal cohort had standardized radiographs performed at study enrollment and annually thereafter. Three radiology technicians were specifically trained to standardize the quality of the radiographs. The distance between the cassette and the x-ray beam was 40 inches for all x-rays. The radiographic series included a true anterior-posterior view in the scapular plane with the arm in neutral rotation and in zero degrees elevation. A supraspinatous outlet view (SOV) was performed in the posterior to anterior direction and the x-ray beam was directed with a 10 degree caudal tilt26.

All radiographs were reviewed by three independent observers blinded to the clinical and ultrasound data. Due to the historically poor interobserver reliability of acromial measurements and classifications, three separate training sessions were conducted. These sessions served to allow for collaboration and further clarification of the classification systems used in this analysis. All radiographs were reviewed after these training sessions and there was no further collaboration after radiographic analysis had begun.

Acromial morphology analysis

All shoulders were classified into one of three acromial shapes using the SOV. The Bigliani classification system was used (Figure 1)4. This system classifies the shape of the undersurface of the acromion as flat (type I), curved (type II), or hooked (type III). For the purpose of analysis, a type III acromion was felt to be present if there was a distinct inferior projection of the anterior third of the acromion independent of the presence of an anterior projecting osteophyte. If the SOV was felt to be inadequate to determine the acromial shape by one or more of the reviewers, it was excluded from analysis. Of the 216 subjects, 208 had acceptable radiographs for acromial morphology analysis.

Figure 1. Acromial morphology classification system.

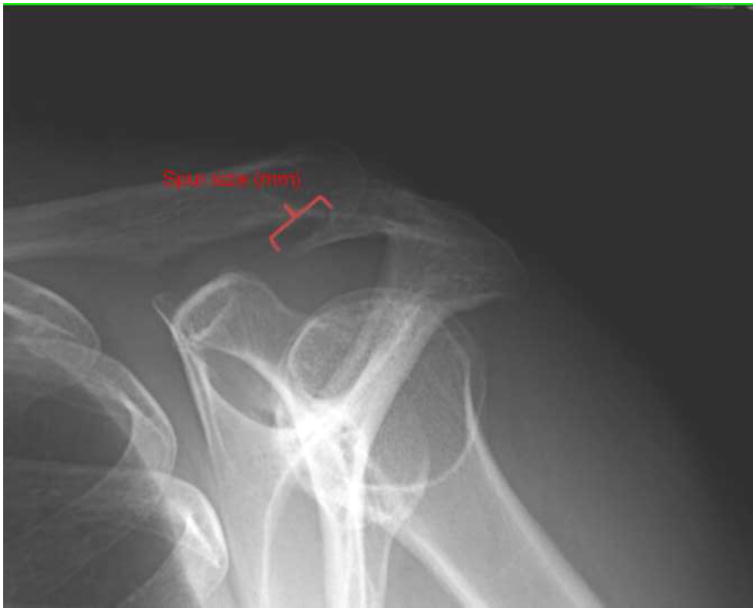

Acromial spur analysis

The SOV was also used to assess for the presence of an acromial spur. A spur was defined as a boney projection along the insertion of the coracoacromial ligament that showed an abrupt change in the curvature of the anterior edge of the acromion as described by Ogawa et al29. Spurs did not have the normal trabecular bone seen in the acromion and always projected toward the coracoid on the SOV (Figure 2). Digital software was used to measure the length of the spur in millimeters. Spurs were measured in a single dimension from the base of the acromial attachment to the tip of the spur. The presence or absence of a spur had no bearing on the acromial morphology classification.

Figure 2. Acromial Spur measurement method.

Acromial index analysis

The acromial index (AI) is a method to quantify the amount of lateral extension of the acromion relative to the humeral head. Described by Nyffeler et al, this calculation is done using the true anteroposterior radiograph27. All radiographs were taken with the arm in neutral rotation and adduction. Three parallel lines are drawn with the first line connecting the superior and inferior glenoid margins. The second line is tangential to the lateral border of the acromion and the third line is tangential and abutting the most lateral aspect of the proximal humerus (Figure 3). The AI is the ratio of the distance to the lateral extent of the acromion over the distance to the lateral extent of the humerus

Figure 3.

Acromial index measurement method. Acromial Index= Distance from glenoid plane to acromion (GA)/Distance from glenoid plane to lateral aspect of humerus (GH).

In addition to the control group in the observation cohort, a second control group was included for acromial index investigation. The controls in the observation cohort had known rotator cuff tears on the non-study shoulder and may be pre-disposed to having lateral extension of the acromion (i.e. a larger acromial index). Therefore, a group of 43 patients with no rotator cuff disease was chosen as a second control group for this analysis. These patients were identified by CPT query for capsular release of adhesive capsulitis. All patients underwent surgical treatment of adhesive capsulitis and had an intact rotator cuff at the time of surgery. All radiographs were reviewed to confirm the absence of any underlying pathology (ie: fracture, osteoarthritis, calcific tendinitis). Initially 65 radiographs were screened, and 22 were excluded due to insufficient radiographic quality, leaving 43 for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Agreement among three raters' measurement of acromial spur size and acromial index was calculated with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Acromial spur measurements were collapsed to create a dichotomous variable to represent spur presence (defined as a measurement greater than 0mm) and an additional dichotomous variable to represent large spur presence (defined as a measurement greater than 5mm). Agreement among three raters for spur presence and acromial morphology grade was expressed using Cohen's simple kappa coefficients (κ) and percent perfect agreement with corresponding 95% CIs. Agreement coefficients were interpreted using the general guidelines suggested by Landis and Koch19: 0 = poor, 0 - 0.2 = slight, 0.21 - 0.40 = fair, 0.41 - 0.60 = moderate, 0.61 - 0.80 = substantial, and 0.81-1.0 = almost perfect agreement. However, these guidelines are arbitrary and are often adjusted to more accurately reflect the data being analyzed. Therefore, a value of less than 0.50 was considered “poor” in accordance with previous studies on this particular subject matter6,15,41.

Data for patients with and without a spur were compared using chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and analysis of variance (for continuous variables). Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% CIs are reported to express the association between the presence of a full tear and a spur. ORs reflect the increased likelihood for full tears to have a spur.

Patients with a full tear were compared to patients with a partial or no tear using a multivariable stepwise logistic regression. The model selected variables that contribute information that is statistically independent of the other variables in the model. Based on an a priori decision, spur presence, age, gender, and side dominance were included as possible predictors in the multivariable model. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) are reported for variables selected, adjusted for all variables in the final model.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are shown as a mean ± standard deviation. The data analysis was generated using SAS software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). It should be noted that a large number of statistical tests were conducted. As the number of tests increases, the likelihood increases that any one of these tests is significant by chance alone (type 1 error). Therefore, caution must be used in evaluating the significance of any individual test. More confidence can be had in patterns of similar results.

Results

Study subjects and tear characteristics

The analysis consisted of 216 subjects with an average age of 64.8±10 years (range 37.1 to 90.2 years). Of the 216 subjects included in this analysis, 123 had full thickness rotator cuff tears, 46 had partial thickness tears, and 47 had no rotator cuff tear (control) at the most recent surveillance visit. The average age was 62.8±10 for the patients with intact or partial thickness tear, and 66.2±10 for those patients with a full thickness tear (p= 0.01). Eighty-eight of the 216 (41%) subjects were female and the dominant side was studied in 78 of 214 (36%) subjects (2 patients did not report hand dominance).

Forty-nine of the 216 patients became symptomatic during the surveillance period. The average duration of follow-up for the newly symptomatic shoulders from the time of study enrollment to the onset of pain was 2.3±1 years with a range of 0.4 to 7.2 years. The mean ages of the subjects that developed shoulder pain compared to those that remained pain-free was 62.1±10 and 65.5±10, respectively (p=0.04).

Acromial morphology

The interobserver reliability for acromial morphology was poor with κ=0.41 (95% CI 0.34-0.48) (Table 1). The percent perfect agreement was 72% (95% CI 68%-75%). No further analysis was performed using the acromial morphology classification system due to the low interobserver agreement.

Table 1. Rater Agreement for acromial radiographic characteristics.

| Variable | Number of subjects | reliability coefficient | 95% confidence bounds on coefficient | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lower bound | upper bound | |||

| Acromial morphology | 208 | k=0.41 | 0.34 | 0.48 |

| Acromial spur measurement (mm) | 216 | ICC=0.65 | 0.59 | 0.71 |

| Acromial spur presence | 216 | k=0.59 | 0.52 | 0.66 |

| Large acromial spur (>5mm) presence | 216 | k=0.61 | 0.52 | 0.71 |

| Acromial index* | 216 | ICC=0.86 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

k=simple kappa.

ICC=intraclass correlation coefficient.

Calculated variable: (acromial offset/humeral offset).

Acromial spur

The interobserver reliability for acromial spur measurement was substantial with ICC=0.65 (95% CI 0.59- 0.71) (Table 1). For acromial spur presence greater than 5mm in size, the κ was 0.61 (95% CI 0.52 -0.71) and the percent perfect agreement was 92% (95% CI 90-94%).

As shown in Table 2, 49 subjects were found to have a spur present (>0mm) by at least two of the three readers. Subjects with an acromial spur were slightly older with an average age of 67.2 years (range 53.1 - 82.9 years) than those without a spur (average age 64.0 years; range 37.1 to 90.2 years) but this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). The presence of a full thickness rotator cuff tear was seen in 85 of the 167 (51%) subjects without an acromial spur and in 38 of the 49 (78%) patients with an acromial spur (p=0.0009). The odds ratio (OR) of having a full thickness rotator cuff tear when a spur is present was 3.33 (95% CI 1.60-6.96. The onset of pain was seen in 34 of 167(20%) subjects without a spur and in 15 of 49 (31%) subjects with an acromial spur (p=0.13). A post hoc power analysis showed that the sample size was adequately powered (0.80) to detect an eighteen percent between-group difference in the prevalence of pain (alpha= 0.05).

Table 2. Association of spur presence with patient and tear characteristics.

| variable | overall sample (N=216) | Spur presence | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| absent (n=167) | present (n=49) | |||

|

| ||||

| Age (yr) | 64.8 ± 10 | 64.0 ± 11 | 67.2 ± 8 | 0.06† |

|

| ||||

| Gender: Male | 128 (59%) | 102 (61%) | 26(53%) | 0.32* |

| Female | 88 (41%) | 65 (39%) | 23(47%) | |

|

| ||||

| Dominant Side: No | 136 (64%) | 109 (66%) | 27 (55%) | 0.16* |

| yes | 78 (36%) | 56 (34%) | 22 (45%) | |

|

| ||||

| Pain: No | 167 (77%) | 133 (80%) | 34 (69%) | 0.13* |

| Yes | 49 (23%) | 34 (20%) | 15 (31%) | |

|

| ||||

| Tear type | ||||

| Control/Partial | 93 (43%) | 82 (49%) | 11 (22%) | 0.0009* |

| Full | 123 (57%) | 85 (51%) | 38 (78%) | |

|

| ||||

| Tear measurements for full tears | ||||

|

| ||||

| tear length (mm) | 15.5 ± 9 | 15.0 ± 9 | 16.8 ± 10 | 0.34† |

| n = 120 | n = 83 | n = 37 | ||

|

| ||||

| tear width (mm) | 14.6 ± 9 | 14.1 ± 9 | 15.6 ± 9 | 0.24† |

| n = 120 | n = 82 | n = 38 | ||

For the entire sample and separately by spur presence group, data are the # of patients (% of group) or mean ± standard deviation.

P-value compares spur presence groups by chi-square test.

P-value compares spur presence groups by analysis of variance. For tear size variables, size was log-transformed prior to analysis.

When acromial spurs were further subdivided, 26 subjects were found to have a spur measuring greater than 5mm by at least two of three readers (Table 3). The presence of a full thickness rotator cuff tear was seen in 100 of the 190 (53%) subjects without a large spur and in 23 of 26 (88%) of subjects with a large acromial spur (p=0.0005). When a full thickness tear was present, the tear width was greater when a large acromial spur was present (p=0.046). There was also a trend noted with greater tear length (retraction) and the presence of a large acromial spur (p=0.053). The onset of pain was seen in 40 of the 190 (21%) subjects without a large spur and in 9 of 26 (35%) subjects with a large spur (p=0.12).

Table 3. Association of large acromial spur with patient and tear characteristics (Spurs >5mm).

| variable | Large spur presence | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| absent (n = 190) | present (n = 26) | ||

|

| |||

| Age (yr) | 64.4 ± 10 | 67.0 ± 7 | 0.23† |

|

| |||

| Gender: Male | 112 (59%) | 16 (62%) | 0.80* |

| Female | 78 (41%) | 10 (38%) | |

|

| |||

| Dominant Side: No | 123 (65%) | 13 (50%) | 0.13* |

| Yes | 65 (35%) | 13 (50%) | |

|

| |||

| Pain No | 150 (79%) | 17 (65%) | 0.12* |

| Yes | 40 (21%) | 9 (35%) | |

|

| |||

| Tear type | |||

| Control/Partial | 90 (47%) | 3 (12%) | 0.0005* |

| Full | 100 (53%) | 23 (88%) | |

|

| |||

| Tear measurements for full tears | |||

|

| |||

| tear length (mm) | 14.8 ± 9 | 18.4 ± 9 | 0.053† |

| n =97 | n = 23 | ||

|

| |||

| tear width (mm) | 14.0 ± 9 | 16.7 ± 8 | 0.046† |

| n =97 | n =23 | ||

Data are the # of patients (% of spur presence group) or mean ± standard deviation.

P-value compares groups chi-square test.

P-value compares groups by analysis of variance. For tear size variables, size was log-transformed prior to analysis.

Further investigation was performed to clarify the association of age, presence of an acromial spur, and rotator cuff disease. Using a univariate model, spur presence and advancing age were associated with the presence of a full-thickness cuff tear (p=0.0009 and p=0.01, respectively) but gender was not (p=0.09). A multi-variable logistic regression model (table 4) showed that the presence of an acromial spur, regardless of size, was highly associated with a full thickness rotator cuff tear even after adjusting for age, gender, and hand dominance (OR=3.05; 95% CI 1.42-6.52).

Table 4. Multivariable logistic regression model of characteristics and adjusted odds ratios for the presence of a full tear.

| variable | adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Incremental R2 (selection order) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| spur, presence vs. absence | 3.05 (1.42, 6.52) | 0.05 (1) | 0.001 |

| age (yr) | 1.39 (1.04, 1.86) | 0.02 (2) | 0.03 |

| gender, male vs. female | 1.83 (1.02, 3.31) | 0.02 (3) | 0.03 |

| side, dominant vs. nondominant (bilaterals are coded as dominant) | 1.81 (0.98, 3.32) | 0.02 (4) | 0.055 |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval for the OR; NS = not significant.

Adjusted ORs reflect the increased odds of having a full tear. For categorical characteristics, reference categories were spur absence, female gender, and nondominant side. ORs for age are expressed in units of 10 years.

Acromial index

The interobserver reliability for the acromial index was excellent with ICC=0.86 (95% CI 0.83-0.89) (Table 1). The overall mean acromial index was 0.691±0.06 (range 0.540-0.884). As shown in table 5, the AI was higher in females than males (0.705 versus 0.682, p=0.01). The AI did not correlate with age or hand dominance (p=0.25 and 0.08 respectively). The mean AI for subjects with no or partial rotator cuff tears was 0.691, and for those subjects with full thickness rotator cuff tears it was 0.692 (p=0.92). Subjects with new onset pain had slightly larger values for acromial index than those that remained asymptomatic (0.710 vs. 0.686, p=0.02). A post hoc power analysis, with an alpha level of 0.05, showed that the given sample size and observed variability had adequate power of 0.80 to detect a minimum of 0.023 between-group difference in AI. Also, a multivariable analysis of variance showed that pain was still associated with AI even after adjusting for gender (p= 0.04).

Table 5. Association of acromial index with patient and tear characteristics.

| variable | n | mean ± SD of acromial index* | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (yr) | 216 | r = -0.08 | 0.25 |

|

| |||

| pain | |||

| no | 167 | 0.686 ± 0.06 | 0.02† |

| yes | 49 | 0.710 ± 0.07 | |

|

| |||

| Gender: | |||

| male | 128 | 0.682 ± 0.06 | 0.01† |

| female | 88 | 0.705 ± 0.07 | |

|

| |||

| Dominant side: | |||

| no | 136 | 0.697 ± 0.06 | 0.08† |

| yes (bilaterals are coded as dominant) |

78 | 0.682 ± 0.07 | |

|

| |||

| Tear type: | |||

| control/partial | 93 | 0.691 ± 0.06 | 0.92† |

| full | 123 | 0.692 ± 0.06 | |

SD = standard deviation. n = # of patients.

Calculated variable: (acromial offset/humeral offset).

P-value compares acromial index across groups by analysis of variance.

Acromial index was also measured in a group of patients without a history of rotator cuff disease in either shoulder. This control group (n=43) was significantly younger than the rotator cuff observational cohort (50.6 ±8 versus 64.8 ±10 years, p<0.0001). The AI was 0.690 ±0.07 in this group, showing no difference compared to the patients in the rotator disease cohort (p=0.91).

Discussion

The acromion has been implicated in the pathogenesis of rotator cuff disease for many years. Neer investigated the mechanism of impingement and described a focal, critical area of contact between the supraspinatous tendon and the undersurface of the anterolateral acromion24. Further cadaveric investigations showed a close relationship between acromial shape and rotator cuff disease4,23. These findings led to the widespread use of partial anterior acromioplasty to treat rotator cuff disease and this procedure was associated with good clinical results3,10,13,31. Since Neer's original findings, many methods have been described to link the radiographic appearance of the acromion and coracoacromial arch with rotator cuff disease. Acromial shape4, acromial slope17, acromial angle36, acromial tilt1, acromiohumeral distance, acromial spur formation29, and acromial index27 have all been proposed to predict which patients have rotator cuff tears. We chose to further investigate three particular methods of classifying the radiographic appearance of the acromion: acromial morphology, acromial spur, and acromial index.

Acromial morphology was chosen for investigation as it is still widely used in clinical practice throughout the world. We found that the Bigliani acromial morphology classification system lacked interobserver reliability (κ=0.41). These findings were despite collaboration sessions conducted by the three reviewers prior to radiographic assessment. Also, radiographs were performed in a standardized fashion with a precise radiographic protocol by specially trained staff Due to the poor rater agreement, no further analysis was conducted using acromial morphology. These results were not unanticipated as others have reported poor interobserver reliability using this classification system. Jacobson et al reviewed 126 SOV radiographs and each acromion was classified as type I, II, or III by six fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons15. The interobserver reliability coefficient was 0.516 and was lowest when delineation between type II and III was required. In another investigation, Zuckerman et al conducted a cadaveric study of 110 scapulas, where the entire acromion was visually inspected by three shoulder surgeons and classified by the Bigliani system41. They found poor agreement among the three reviewers with an ICC similar to the one found in our study (κ=0.41). Based on these studies and our findings, we agree with previous investigators that acromial morphology is an unreliable method to characterize the acromion and a more objective system should be employed to determine the relationship of acromion characteristics and rotator cuff disease.

We also investigated the presence of an acromial spur along the coracoacromial ligament. We chose this method because it appeared to be a more reliable and consistent measure compared to acromial shape and others have found it to be predictive of rotator cuff disease29. Our rater agreement was substantial with an ICC value of 0.65 for the spur measurement (mm), κ=0.59 for spur presence, and κ=0.61 for presence of a large spur. We found that the presence of an acromial spur was highly associated with a full thickness rotator cuff tear (p= 0.0009) (Figure 4). Additionally, spurs larger than five millimeters were found to be associated with larger tears. Our results coincide with those of Ogawa et al. as they found a high association between spurs measuring 5 mm or more and bursal or complete rotator cuff tears29. They also found that acromial spurs were more common in older patients. Our data showed a similar trend with a mean age of 64 for patients without the presence of a spur and 67 for those with a spur (p= 0.06). We were concerned that age and presence of an acromial spur would be closely linked and, therefore, lead to a faulty assumption that rotator cuff disease was associated with spur presence. Therefore, a multivariable analysis was performed to clarify the role of age, spur presence, and rotator cuff disease. We found that acromial spur presence was significantly associated with the presence of a full thickness rotator cuff tear after adjusting for the potential influence of age, gender, and hand dominance.

Figure 4.

SOV showing a 15mm acromial spur in a 72 year-old asymptomatic patient. Ultrasound examination revealed a full thickness rotator cuff tear measuring 12 × 12mm.

The last method we chose to investigate was the acromial index described by Nyffeler27. We found this to be a novel measurement tool that showed convincing evidence of a close relationship between lateral acromial extension and rotator cuff disease. Our interobserver reliability was excellent using this measurement tool (ICC=0.86). However, we were unable to demonstrate a difference in the acromial index between patients with and without rotator cuff tears. To ensure that the control group in the observation cohort was not predisposed to a larger acromial index (because of known rotator cuff disease on the contralateral side), we studied a group of control patients with no history of rotator cuff disease. We found all these groups to have nearly an identical acromial index (means 0.690 and 0.691). These results conflict with those of Nyffeler et al. They found the mean AI of patients without rotator cuff disease to be 0.64 and the AI of those with full thickness rotator cuff tears to be 0.73 (p<0.0001) and these findings were later corroborated by Torrens et al37. Although both our and Nyffeler's studies employed standardized radiographs, it is possible that subtle differences in the methods of radiographic assessment led to this disparity. However, we feel that the high interobserver reliability and narrow confidence intervals found in our study suggest that no association exists between lateral acromial extension and rotator cuff disease.

We attempted to describe the association of various acromial radiographic variables with the development of pain in shoulders with asymptomatic cuff tears. This aim has not been previously investigated. Previous studies of this observational cohort have shown pain development to occur in short-term follow-up in approximately 20% of subjects21. Risk factors for the development of pain included the presence of a larger tear at the time of enrollment and tear enlargement over time. Furthermore, another study related to this cohort showed a higher likelihood of pain in the dominant shoulder16. In the present study, a slightly larger acromial index was seen in shoulders that became painful. In addition, nonsignificant trends were seen between the presence of an acromial spur and the development of pain. It remains uncertain, at this point, the potential role of the acromial architecture to the development of shoulder pain in patients with known cuff disease. It is likely that pain development in patients with degenerative cuff tears is complex and multifactorial; however, the findings of this study suggest that further investigation into the potential role of the acromion to the development of pain is warranted.

Our study investigated a unique cohort of asymptomatic patients that were identified by ultrasound to have an intact, partially torn, or completely torn rotator cuff. These patients were followed over time with annual sonographic, radiographic, and clinical assessment. We felt that this group of patients would be ideal to investigate the relationship between radiographic acromial findings and rotator cuff disease. Standardized radiographs were performed and blinded reviewers evaluated all radiographs. High-resolution ultrasonography was used to evaluate the rotator cuff as this method and technique has been validated at our institution34,35. Although some of our findings have been previously shown in the literature, the methodology of this investigation including its prospective design, blinded radiographic analysis, and standardized data acquisition offers compelling validation to this controversial topic.

This study has several limitations that must be recognized. For the purposes of this study, the definition of an acromial spur was somewhat arbitrary. We sought to identify and measure irregular bone formation along the insertion of the coracoacromial ligament. Therefore, our conclusions cannot be extrapolated to any other type of acromial boney excrescence. Although, prospective protocols were in place to enhance radiographic reliability, 100% accuracy of radiographs could not be achieved and some variability in technique surely occurred. Also, this investigation did not explore the temporal changes of subjects through their surveillance period. This information, which may be the subject of future research, may help clarify the causal relationship of acromial spurs and rotator cuff disease. Therefore, the association of acromial spur presence with rotator cuff disease found in this study cannot be used to infer a causal relationship between these two variables.

Conclusions

The presence of an acromial spur at the acromial insertion of the coracoacromial ligament is highly associated with the presence of a full thickness rotator cuff tear in both symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects even after controlling for confounding variable such as age and gender. Spurs measuring greater than five millimeters are associated with larger rotator cuff tears. Acromial morphology is an unreliable classification system with poor interobserver reliability. The acromial index is associated with the development of pain in previously asymptomatic shoulders, but shows no association with the presence of rotator cuff disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tomoyuki Mochizuki MD and Chanteak Lim MD for their invaluable contributions to this study.

Funding: The funding source for this study was an R01 grant (AR051026-01A1) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

IRB: Study approved by Washington University Human Research Protection Office (IRB # 201103230)

All authors, their immediate family, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated did not receive any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Dr. Yamaguchi receives royalties from Tornier, which is unrelated to the subject of this article.

Level of evidence: Level III, Cross-Sectional Study Design, Epidemiology Study

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aoki M, Ishii S, Usui M. Clinical application for measuring the slope of the acromion Surgery of the Shoulder R H B Morrey. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1990. p. 200. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biberthaler P, Wiedemann E, Nerlich A, Kettler M, Mussack T, Deckelmann S. Microcirculation associated with degenerative rotator cuff lesions. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005;85-A:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bigliani LU, D'Alessandro DF, Duralde XA, McIlveen SJ. Anterior acromioplasty for subacromial impingement in patients younger than 40 years of age. Clin Orthop. 1989;246:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigliani LU, Morrison DS, April EW. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans. 1986;10:216. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigliani LU, Ticker JB, Flatow EL, Soslowsky LJ, Mow VC. The relationship of acromial architecture to rotator cuff disease. Clin Sports Med. 1991;10(4):823–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bright AS, Torpey B, Magid D, Codd T, McFarland EG. Reliability of radiographic evaluation for acromial morphology. Skeletal Radiology. 1997;26(12):717–721. doi: 10.1007/s002560050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chambler AFW, Pitsillides AA, Emery RJH. Acromial spur formation in patients with rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:314–321. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(03)00030-2. 310.1016/S1058-2746(1003)00030-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Codman EA. Rare lesions of the shoulder. In: Codman EA, editor. The Shoulder: Rupture of the Supraspinatus Tendon and Other Lesions In or About the Subacromial Bursa. Boston: Thomas Todd Co.,; 1934. pp. 468–509. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein RE, Schweitzer ME, Frieman BG, Fenlin JM, Mitchell DG. Hooked acromion: Prevalence on MR images of painful shoulders. Radiology. 1993;187(2):479–481. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.2.8475294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frieman BG, Fenlin JM. Anterior acromioplasty: effect of litigation and workers' compensation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:175–181. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukuda H, Hamada K, Yamanaka K. Pathology and pathogenesis of bursal-side rotator cuff tears viewed from en block histologic sections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill TJ, McIrvin E, Kocher MS, Homa K, Mair SD, Hawkins RJ. The relative importance of acromial morphology and age with respect to rotator cuff pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:327–330. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.124425. 310.1067/mse.2002.124425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ha'eri GB, Wiley AM. Shoulder impingement syndrome. results of operative release. Clin Orthop. 1982;168:128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang CY, Wang VM, Pawluk RJ, Bucchieri JS, Levine WN, Bigliani LU. Inhomogeneous mechanical behavior of the human supraspinatous tendon under axial loading. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2005;23:924–930. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.02.016. 910.1016/j.orthres.2004. 1002.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson SR, Speer KP, Moor JT, Janda DH, Saddemi SR, MacDonald PB, Mallon WJ. Reliability of radiographic assessment of acromial morphology. Journal of Shouder and Elbow Surgery. 1995;4(6):449–453. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keener JD, Steger-May K, Stobbs G, Yamaguchi K. Asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: patient demographics and baseline shoulder function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2010.07.017. 1110.1016/j.jse.2010.1107.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitay GS, Iannotti JP, Williams GR, Haygood T, Kneeland BJ, Berlin J. Roentgenographic assessment of acromial morphologic condition in rotator cuff impingement syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4:441–448. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(05)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumagai J, Sarkar K, Uhthoff HK. The collagen types in the attachment zone of rotator cuff tendons in the elderly. Journal of Rheumatol. 1994;21:2096–2100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measure of observer agreement for catagorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacGillivray JD, Fealy S, Potter HG, O'Brien SJ. Multiplanar analysis of acromion morphology. American Journal of Sports Medicine. 1998;26(6):836–840. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260061701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, Steger-May K, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Stobbs G, Yamaguchi K. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg. 2010;92:2623–2633. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00506. 2610.2106/JBJS.I.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayerhoefer ME, Breitenseher MJ, Wurnig C, Roposch A. Shoulder impingement: relationship of clinical symptoms and imaging criteria. Clin Journal of Sports Medicine. 2009;19(2):83–89. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0b013e318198e2e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison DS, Bigliani LU. The clinical significance of variations in acromial morphology. Orthop Trans. 1987;11:234. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neer CS. Impingement Lesions. Clin Orthop. 1983;173:70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 1972;54:41–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neer CS, Poppen NK. Supraspinatous outlet. Orthop Trans. 1987;11:234. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nyffeler RW, Werner CML, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 2006;88(4):800–805. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.03042. 810.2106/JBJS.D.03042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogata S, Uhthoff HK. Acromial enthesopathy and rotator cuff tear. Clinical Orthop. 1990;254:39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogawa K, Yoshida A, Inokuchi W, Naniwa T. Acromial spur: relationship to aging and morphologic changes in the rotator cuff. Journal of Shouder and Elbow Surgery. 2005;14(6):591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2005.03.007. 510.1016/j.jse.2005.1003.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. Journal of Boe. 1988;70:1224–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Post M, Cohen J. Impingement syndrome. a review of late stage II and early stage III lesions. Clin Orthop. 1986;207:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prickett WD, Teefey SA, Galatz LM, Calfee RP, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. Accuracy of ultrasound imaging of the rotator cuff in shoulders that are painful postoperatively. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 2003;85-A:1084–1089. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200306000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar K, Taine W, Uhthoff HK. The ultrastructure of the coracoacromial ligament in patients with chronic impingement syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1990;254:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleton WD, Patel M, Wright RW, Yamaguchi K. Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff. A comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. Journal of Shouder and Elbow Surgery. 2000;82:498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teefey SA, Rubin DA, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Leibold RA, Yamaguchi K. Comparison of ultrasonographic, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthroscopic findings in seventy-one consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86-A:708–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Toivonen DA, Tuite MJ, Orwin JF. Acromial structure and tears of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1995;4(5):376–383. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(95)80022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torrens C, Lopez J, Puente I, Caceres E. The influence of the acromial coverage index in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:347–251. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.07.006. 310.1016/j.jse.2006.1007.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uhthoff HK, Hammond DI, Sarkar K, Hooper GJ, Papoff WJ. The role of the coracoacromial ligament in the impingement syndrome. Int Orthop. 1988;12:97–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00266972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hurwitz S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. The rising incidence of acromioplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) 2010;92-A(9):1842–1850. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01003. 1810.2106/JBJS.l.01003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worland RL, Lee D, Orozco CG, Sozarex F, Keenan J. Correlation of age, acromial morphology, and rotator cuff tear pathology diagnosed by ultrasound in asymptomatic patients. J South Orthop Assoc. 2003;12(1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zuckerman JD, Kummer FJ, Cuomo F, Greller M. Interobserver reliability of acromial morphology classification: an anatomic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:286–287. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(97)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]