Abstract

Background

The spectrum of BRCA1/2 genetic variation in breast-ovarian cancer patients has been scarcely investigated outside Europe and North America, with few reports for South America, where Amerindian founder effects and recent multiracial immigration are predicted to result in high genetic diversity. We describe here the results of BRCA1/BRCA2 germline analysis in an Argentinean series of breast/ovarian cancer patients selected for young age at diagnosis or breast/ovarian cancer family history.

Methods

The study series (134 patients) included 37 cases diagnosed within 40 years of age and no family history (any ethnicity, fully-sequenced), and 97 cases with at least 2 affected relatives (any age), of which 57 were non-Ashkenazi (fully-sequenced) and 40 Ashkenazi (tested only for the founder mutations c.66_67delAG and c.5263insC in BRCA1 and c.5946delT in BRCA2).

Discussion

We found 24 deleterious mutations (BRCA1:16; BRCA2: 8) in 38/134 (28.3%) patients, of which 6/37 (16.2%) within the young age group, 15/57 (26.3%) within the non-Ahkenazi positive for family history; and 17/40 (42.5%) within the Ashkenazi. Seven pathogenetic mutations were novel, five in BRCA1: c.1502_1505delAATT, c.2626_2627delAA c.2686delA, c.2728 C > T, c.3758_3759delCT, two in BRCA2: c.7105insA, c.793 + 1delG. We also detected 72 variants of which 54 previously reported and 17 novel, 33 detected in an individual patient. Four missense variants of unknown clinical significance, identified in 5 patients, are predicted to affect protein function. While global and European variants contributed near 45% of the detected BRCA1/2 variation, the significant fraction of new variants (25/96, 26%) suggests the presence of a South American genetic component.

This study, the first conducted in Argentinean patients, highlights a significant impact of novel BRCA1/2 mutations and genetic variants, which may be regarded as putatively South American, and confirms the important role of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Argentinean Ashkenazi Jews.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/2193-1801-1-20) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Argentina, early onset breast cancer; BRCA1/BRCA2; Germline mutations; Genetic variants; Familial breast cancer; Ashkenazi; Ethnicity

Introduction

Hereditary breast cancer accounts for 5-10% of all BC cases [1] and is characterized by dominant inheritance, premenopausal diagnosis, more severe course, bilaterality and frequent association with ovarian cancer (OC) [2]. The identification of the two major hereditary breast/ovarian cancer genes, BRCA1 (17q21, MIM* 113705) in 1994 [3] and BRCA2 (13q14, MIM* 600185) in 1995 [4], led to a new era in the diagnosis of inherited high predisposition to breast and ovarian cancer [5, 6]. Breast-ovarian cancer (BOC)-causing mutations and other genetic variants are distributed along the entire coding and non-coding regions of BRCA1 and BRCA2, and more than 3400 gene variants have been described in the Breast Cancer Information Core (BIC) [7]. New variants continue to be detected worldwide, mostly in BRCA1.

The prevalences of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in BOC patients with early onset (EO) and/or BOC family history (FH) appear to be similar across race/ethnicity, but there is evidence of important racial and/or geographic differences in the spectrum of BRCA1/2 genetic variation, including pathogenic mutations and variants of uncertain significance. These differences may reflect population history and genetic drifts, and could have a significant impact on genetic counselling, genetic testing, and follow-up care [8]. A typical example is provided by the case of Ashkenazi Jews, where three founder mutations: BRCA1 c.66_67delAG BRCA1 c.5263insC, and BRCA2 c.5946delT account for most of familial breast-ovarian cancer [9]. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel: frequency and differential penetrance in ovarian cancer and in breast-ovarian cancer families [10].

BRCA1/2 mutation status in subsets of BOC patients selected for age, BOC family history and ethnicity has been scarcely investigated outside Europe and North America [5, 11–15], with few reports for South America, where Native American founder effects and the complex multiracial demography of recent immigration are predicted to result in high genetic variation[16]. Indeed, recent studies point to a role of Native American ancestry in BRCA1/2 disease patterns in Central and Northern America [17–22]. Epidemiological data indicate that in Argentina BC incidence [23] and mortality rates [24] are among the highest in the world. The historical records and epidemiological and molecular studies point to variable degrees of admixture among European, mainly Spanish and Italian, and Native American components in more than 50% of the Argentinean population [16, 25]. Regarding autosomal evidence of admixture, the relative European, Native American, and West African genetic contributions to the Argentinean gene pool were estimated to be 67.55%, 25.9%, and 6.5%, respectively [7].

Our study is the first report describing BRCA1/BRCA2 gene variants in Argentinean BOC patients, and highlights a significant impact of novel mutations and genetic variants which may be regarded as putatively South American. On the other hand, we confirm the key role of founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Argentinean Ashkenazi Jews.

Methods

The study includes 134 BOC probands selected either for age at cancer diagnosis or for family history (FH), according to the criteria listed in Table 1. The patients selected for diagnosis within 40 years of age and no BOC FH (EO patients, any ethnicity) included 37 cases (21 with BC, 13 with OC, 3 with BOC; age range 12–40 years, mean age 31.0 ± 7.5 years). The FH patients (any age, 97 cases overall), selected based on the presence of at least two BOC-affected 1st or 2nd degree relatives, included 57 non-Ashkenazi patients (32 with BC, 18 with OC, 7 with BOC, age range 26–71 years, mean 44.6 ± 10.9 years), and 40 Ashkenazi patients (32 with BC, 6 with OC and 2 with BOC, age range: 32–64 years, mean age 47.1 ± 9.9 years) (Tables 1 and 2). The Ashkenazi subset was tested only for the panel of the three founder Ashkenazi mutations (c.66_67delAG (reported in BIC as 185delAG), and c.5263insC (in BIC as 5382insC) in BRCA1 and c.5946delT (in BIC as 6174delT) in BRCA2); all the other cases were fully sequenced.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the probands

| Group (n) | Criteria | Number of probands |

|---|---|---|

| EO (37) | Onset of cancer ≤40 years | 37 |

| Ashk-FH (40) | Onset of cancer ≤40 years with family history | 12 |

| Onset of cancer >40 years with family history | 28 | |

| FH (57) | Onset of cancer ≤40 years with family history | 31 |

| Onset of cancer >40 years with family history | 26 | |

| Total | 134 |

n: total number of probands per group. EO: Early onset; Ashk: Ashkenazi; FH: Family history, defined as: at least 2 members of 1st or 2nd degree with breast and/or ovarian cancer.

Table 2.

Summary of the mutations detected

| Total patients = 134 (group) | Age at diagnosis (n) | Family history | BRCA1mutation (%) | BRCA2mutation (%) | % of mutated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 37 (EO) | ≤40 years (37) | No | 4 (10.8) | 2 (5.4) | 16.2 |

| 40 (Ashk-FH) | ≤40 years (12) | Yes | 3 (25.0) | 4 (33.3) | 58.3 |

| >40 years (28) | Yes | 6 (21.4) | 4 (14.3) | 35.7 | |

| 57 (FH) | ≤40 years (31) | Yes | 3 (9.7) | 3 (9.7) | 19.4 |

| >40 years (26) | Yes | 7 (26.9) | 2 (7.7) | 35.8 |

EO: Early onset; Ashk: Ashkenazi; FH: Family History.

Total coding BRCA1-2 sequencing was performed for the patients in all groups except.

the Ashkenazi patients which were tested for the panel of three mutations.

(n): number of probands analyzed.

Blood samples were sent from the participating centers to the Laboratory HRDC of the Department of Biochemistry, University of Buenos Aires, and were also recruited at the Centro de Estudios Medicos e Investigaciones Clinicas (CEMIC). Study eligibility required signing an informed consent as a result of the routine procedures for genetic analysis. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sociedad Argentina de Investigación Clínica.

Genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA blood purification kit (Qiagen, http://www.qiagen.com). The coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries of the BRCA1-2 genes were analyzed by amplification using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with alternative primers to avoid false results due to polymorphisms [26, 27], followed by direct sequencing of at least 55 amplicons, to ensure overlapping of the segments. Sequencing was performed using either an Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer or an Applied Biosystems ABI PRISM ® 310 Genetic Analyzer. Homozygosis (HO) was confirmed by alternative sequencing in exonic and/or intronic regions. The three Ashkenazi mutations were tested as described [28]. Variants nomenclature follows the guidelines of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS). Tables provide lists including also the nomenclature of the Cancer Information Core Internet Website (BIC), April 2012.

Effects of the missense mutations that resulted not reported or recorded as clinically unknown (CU) in the BIC were predicted by virtual analyses of functional compatibility for aminoacid changes using two programs: Align-GVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/) [29] and SIFT (http://sift.bii.a-star.edu.sg/) [30].

Results and discussion

We describe for the first time in Argentina the results of BRCA1/BRCA2 germline analysis in 134 BOC probands selected either for diagnosis within 40 years of age (37 cases) or for FH (97 cases) (Tables 1 and 2). The latter included 40 Ashkenazi patients, tested only for the three founder Ashkenazi mutations [28]. All the other cases were fully sequenced.

Overall 96 mutations and sequence variants, of which 53 in BRCA1 and 43 in BRCA2, were identified in 94/134 patients analyzed. Mutation types, effects, carrier frequencies, worldwide occurrences and relevant references are listed in online Additional file 1: Tables S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2. The sequence variants were classified as pathogenic based on literature data and/or when predicted to truncate/inactivate the protein product.

Among the 53 sequence variants identified in BRCA1 15 are novel and 17 clinically unknown, 14 introduce a stop codon; 22 are missense substitutions (Additional file 1: Table S1). With regard to the 43 BRCA2 mutations, 9 are novel, 17 clinically unknown, 6 introduce a stop codon; 15 are missense substitutions and one is predicted to result in an aberrant splice (Additional file 2: Table S2). The truncating mutations and the novel non-truncating variants predicted to affect the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene products are described in Table 3. Synonyms, intronic and polymorphic BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants ranged from 4 to 33 per individual patients and were detected in all the 94 fully-sequenced cases (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2). Notably, 34 variants are listed in BIC as of clinically unknown importance, and of these 14 were identified in unique patients (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

Table 3.

BRCA1/BRCA2truncating mutations, novel and non-truncating variants affect the gene products

| Exon | Codon | (HGVS) Protein level | (HGVS) DNA level | BIC DNA level | BIC Status | Carrier CODE | Index case Status (age) | Family history | Inclusion Criteria | Worldwide Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | ||||||||||

| 2 | E23VfsX16 | Stop cod39 | c.66_67delAG | 185delAG | D | AB54 | Br(37) | Br | Ashk-EO-FH | Ashkenazi |

| AB60 | Br(40) | Br | Ashk-EO- | |||||||

| AB77 | Ov (44) | Br, Ov | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB68 | Ov (44) | Br, Ov | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB76 | Br (49) | Br | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB81 | Br (52) | Br | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB87 | Ov (60) | Br, Ov | FH Ashk-FH | |||||||

| 2 | E23KfsX18 | Stop cod40 | c.67insA | 186insA | D | AB82 | Br (34) | Br | EO-FH | NE/ME |

| 5 | C61G | p. Cys61Gly | c.181 T > G | 300 T > C | D | AB75 | Br (49) | Br | FH | E |

| 5 | R71G | p. Arg71Gly | c.211A > G | 330A > G | D | AB64 | Br (43) | Br | FH | E |

| 7 | E143X | p. Glu143Stop | c.427 G > T | 546 G > T | D | AB46 | Br (33) | Br, Ov, Pa, Pr | EO-FH | E |

| 11 | S267KfsX19 | Stop cod285 | c.797_798delTT | 916delTT | D | AB36 | Br-Ov (46) | Br | FH | C, L-A E, N-A |

| 11 | K501Kfs30 | Stop cod530 | c.1502_1505delAATT | 1621delAATT | NR | AB20 | Br (32) | No | EO | Argentina |

| 11 | R504VfsX28 | Stop cod531 | c.1510delC | 1629delC | D | AB40 | Br (30) | Br | EO-FH | E |

| 11 | E836GfsX2 | Stop cod837 | c.507_2508delAA | 2626delAA | NR | AB67 | Br (50) | Br | FH | Argentina |

| 11 | S896Vfs104 | Stop cod999 | c.2686delA | 2805delA | NR | AB85 | Br (55) | Br | FH | Argentina |

| 11 | Q910X | p. Gln910Stop | c.2728 C > T | 2847C > T | NR | AB84 | Ov (55) | Br, Ov, Co | FH | Argentina |

| 11 | R1203X | p. Arg1203Stop | c.3607C > T | 3726C > T | D | AB8 | Ov (25) | No | EO | C, L-A |

| 11 | E1210RfsX8 | Stop cod1218 | c.3627insA | 3746insA | D | AB21 | Br-Ov (33) | No | EO | C, L-A, As |

| 11 | S1253X | p. Ser1253Stop | c.3758_3759delCT | 3877delCT | NR | AB17 | Br (31) | No | EO | Argentina |

| 17 | T1677IfsX2 | Stop cod1678 | c.5030_5033delCTAA | 5149delCTAA | D | AB79 | Br (51)* | Br, Ov, Pa, Pr | FH | E |

| 20 | S1755PfsX75 | Stop cod1829 | c.5263insC | 5382insC | D | AB55 | Br (49) | Br | Ashk-FH Ashk-EO-FH | E, Ashkenazi |

| AB97 | Br (38) | Br | ||||||||

| BRCA2 | ||||||||||

| 9 | - | Splice defect | c.793 + 1delG | IVS9 + 1delG | NR | AB99 | Br (31) | Br | EO-FH | Argentina |

| 11 | N955KfsX5 | Stop cod959 | c.2808_2811delACAA | 3036delACAA | D | AB78 | Br (50) | Br | FH | E, L-A |

| 11 | S1982RfsX22 | Stop cod2003 | c.5946delT | 6174delT | D | AB43 | Br (32) | Br-male | Ashk-EO-FH | Ashkenazi |

| AB47 | Br (33) | Br-male | Ashk-EO- | |||||||

| AB69 | Br/Ov (45) | Br-male | FH Ashk-FH | |||||||

| AB57 | Br (39) | Br, Pa, | Ashk-EO- | |||||||

| AB71 | Br (46) | Ov Pr, | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB74 | Br (48) | Br | FH Ashk- | |||||||

| AB95 | Br (36) | Br | FH Ashk- |

|||||||

| AB96 | Br (60) | Br | EO-FH Ashk-FH | |||||||

| 11 | K1213X | p. Lys1213Stop | c.6037A > T | 6265A > T | D | AB34 | Br (40) | No | EO | E |

| 11 | S1882X | p. Ser1882Stop | c.5644C > G | 5872C > G | D | AB117 | Br (50) | Br, Pr | FH | E |

| 11 | Y1894X | Stop cod1894 | c.5909insA | 6137insA | D | AB92 | Br (31) | Br | EO-FH | E |

| 14 | E2369EfsX23 | Stop cod2391 | c.7105insA | 7333insA | NR | AB98 | Br (35) | Br | EO-FH | Argentina |

| 18 | D2723H | p. Asp2723His | c.8169 G > C | 8397 G > C | CU | AB31 | Ov (38) | No | EO | E |

D, deleterious; CU, clinically unknown importance; NR, Not Reported in Breast Information Core database(BIC)http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/

Global, as defined in BIC or when reported in at least 3 continents ethnic groups in HapMap; E, European; As, Asian; A-A African-American; L-A, Latin American; N-A, Native-American; A-C America-Caucasian; NE/ME, Near Eastern/Middle Eastern;

The DNA sequence numbering of BRCA1and BRCA2 sequence variants is based on recomendations of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS, translation initiation codon ATG = 1) BRCA1:genomic sequence:L78833; RNA sequence: U14680; BRCA2 genomic sequence: NW_001838072; RNA sequence: NM_001838072

In bold, novel mutations not previously reported.

Overall, a total of 24 bona fide pathogenetic mutations, 16 in BRCA1 and 8 in BRCA2, were detected in 38/134 cases (28.4%), including: a) 6/37 (16.2%) fully-sequenced patients in the group within 40 years of age; b) 15/57 (26.3%) fully-sequenced non-Ashkenazi FH patients; c) 17/40 (42.5%) Ashkenazi FH patients, analyzed for the three Ashkenazi mutations only (Table 2). The pathogenetic mutations were more frequent in BRCA1 (23/38, 60.5%) than in BRCA2 (15/38, 39.5%), which is in agreement with literature data [31].

The Ashkenazi-FH patients with age ≤40 years showed the highest frequency of pathogenetic BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, i.e., 58.3% (for BRCA1 16.7% in c.66_67delAG and 8.3% in c.5263insC and 33.3% for BRCA2 c.5946delT), in agreement with literature frequencies [28, 32]. The detection rate of bona fide pathogenetic mutations in FH-negative probands selected for age within 40 years at diagnosis was 6/37 (16.2%). This falls within the 15-31% range reported in the literature for EO BOC with FH [33–36], but is in contrast with the lack of mutations reported in EO Chilean patients without FH [37]. The published data on the South American population [17, 37, 38] show lower rates of mutation detection, while in agreement with results from a study in the USA [31] and a large study in high risk Hispanic family from USA [39] and also with an study of Hispanic BOC from Colombia [40]. Differences in mutation detection rates might reflect divergences in the criteria of proband selection and in the methods of analysis. In fact, the other South American [37, 38] reports were based on indirect mutation detection methods and not on full sequencing; in contrast, we used direct sequencing of all the amplicons along the BRCA1 and BRCA2 coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries.

It may be of interest to compare the deleterious mutation rates of the young patients with no FH (16.2%) and of the FH cases of similar age (within 40 years) in the non-Ashkenazi and Ashkenazi groups (Table 3). Notably, a pathogenetic mutation was found in 6/31 (19.4%) non-Ashkenazi FH patients within 40 years of age (mean age 35.6 ± 4.8 years) and in 7/12 (58.3%) FH Ashkenazi cases within the same age cutoff (mean 35.6 ± 2.8 years). The recurrent Ashkenazi mutations were never detected in non-Ashkenazi probands. BRCA1 c.66_67delAG, BRCA1 c.5263insC and BRCA2 c.5946delT were found in 7 (17.5%), 2 (5%) and 8 (20%) Ashkenazi probands, respectively. Interestingly, BRCA2 c.5946delT was also found in a non-Ashkenazi FH patient who could recall a great grand mother of Ashkenazi origin. Conversely, only a non-Ashkenazi pathogenetic mutation (Asp2723His in BRCA2) was detected in one of 4 patients of Ashkenazi origin included in the subset selected for early diagnosis and no FH. This supports the full sequencing of EO Ashkenazi patients with no BOC FH.

With regard to disease association, the pathogenetic mutations in BRCA1 occurred in 16/88 BC cases (18.2%), 5/24 OC cases (20.8%) and 2/22 BOC cases (9.1%), those in BRCA2 in 13/88 BC cases (14.8%), 1/24 OC cases (4.2%) and 1/22 BOC cases (4.5%). As expected, OC was more frequent in BRCA1 carriers (21.7% vs 6.7%), and BC in BRCA2 carriers (86.6% vs 65.2%) [30].

Seven pathogenic mutations (18.4% of all the mutations detected) were putatively novel: 5 in BRCA1 (21.7% for this gene), all with frameshifts generating stop codons in exon 11, and 2 in BRCA2 (13.3% for this gene), one with a frameshift at nt 2369, exon 14 (c7333 insA), the other (c.793 + 1delG) affecting the donor splicing site nucleotide at IVS + 1 delG in intron 9 (Table 3).

The frequency of the common non-pathogenic variants and synonyms was in agreement with that reported in the BIC. The mutations reported in BIC as CU that we detected in multiple patients as homozygous (in parenthesis number of cases) and/or in association with deleterious mutations, such as p. Gln356Arg, IVS7 + 36 C > T, IVS7 + 41 C > T, IVS14-63 C > G, and IVS18 + 66 G > A in BRCA1 and p. Val2171Val (9), p. Ala2466Val (4), IVS8 + 56 C > T, IVS9 + 65delT, IVS10 + 12delT, and IVS11 + 80delTTAA (1) in BRCA2 most probably represent non-pathogenic variants. Furthermore, based on prediction programs, homozygous status, detection in multiple unrelated patients and/or association with pathogenic mutations, 10 variants found in the present study and not reported in the BIC can be considered non pathogenic. These include p. Val122Asp, p. Gln139Lys, IVS7 + 38 T > C, IVS7 + 49 del 15 bp, in BRCA1 and c*110 A > C at 3'UTR in BRCA2 (two other novel BRCA2 variants, i.e., IVS4 + 246 G > C and IVS4 + 364delT, located far from the end of the exon 4 are reported here only as heterozygosity markers).

Five of the 28 missense variants (Table 4) (i.e., p. Arg7Cys, p. Cys61Gly, p. Arg71Gly, p. Tyr179Cys, and p. Met1652Thr in BRCA1, p. Asp2723His in BRCA2) were predicted to have an impact on protein structure upon evaluation by SIFT and GVGD (Table 4). BRCA1 p. Arg7Cys, differently from the other non-conservative variants, has a rather low prediction score and was found in two cases. The high prediction values for BRCA1 p. Cys61Gly and BRCA1 p. Arg71gly agree with their previously reported pathogenicity [41, 42] (Table 4). Few reported data are available for BRCA2 p. Asp2723His [43]. BRCA1 p. Met1652Thr, located in the BRCT tandem repeat region is predicted to result in a large volume change in rigid neighbourhood [44] but structural and functional assays show normal peptide binding specificity and transcriptional activity [45]. Tyr179Cys is also located in a highly conserved region and is listed as clinically importance unknown (CU) in BIC. Notably BRCA1 Tyr179Cys co-occurred with two other missense mutations, i.e., Phe486Leu and Asn550His, in an FH patient affected with pagetoid BC (AB80). These 3 mutations, already reported to occur together, may constitute a rare haplotype [46] [brca.iarc.fr/LOVD].

Table 4.

BRCA1/2missense variants identified in 94 (non Askenazi) Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer cases

| HGVS :Protein: DNA | BIC: Status | N° Carrier (%) | Co-occurrence with deleterious | PredictionSIFT GVGD grade | refSNP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | |||||||

| p. Arg7Cys | c.19C > T | CU | 2(1.1) | - | NT | C15 | rs144792613 |

| p. Cys61Gly | c.181 T > G | D | 1 (1.1) | - | NT | C65 | - |

| p. Arg71Gly | c.211A > G | D | 1 (1.1) | - | NT | C65 | - |

| p. Val122Asp | c.365 T > A | NR | 5 (5.3) | BRCA2 | T | C0 | - |

| p. Gln139Lys | c.415C > A | NR | 6 (6.3) | - | T | C0 | - |

| p. Tyr179Cys | c.536A > G | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA1 [30] (AB80) | NT | C35 | rs56187033 |

| p. Gln356Arg | c.1067A > G | CU | 10 (10.6) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | T | C0 | rs1799950 |

| p. Phe486Leu | c.1456 T > C | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA1 [30] (AB80) | T | C0 | rs55906931 |

| p. Val525Ile | c.1573 G > A | CU | 1 (1.1) | - | T | C0 | rs80357273 |

| p. Asn550His | c.1648A > C | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA1 [30] (AB80) | NT | C0 | rs56012641 |

| p. Asp693Asn | c.2077 G > A | CN | 8 (8.5) | BRCA1 | T | C0 | rs4986850 |

| p. Pro871Leu | c.2612C > T | CN | 29 (30.9) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | T | C0 | rs799917 |

| p. Lys898Glu | c.2692A > G | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA2 | T | C0 | rs80357420 |

| p. Met1008Ile | c.3024 G > A | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA1 [30] | T | C0 | rs1800704 |

| p. Glu1038Gly | c.3113 G > A | CN | 33 (35.1) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | T | C0 | rs16941 |

| p. Ser1040Asn | c.3119 G > A | CU | 1 (1.1) | BRCA1 [31] | T | C0 | rs4986852 |

| p. Asp1131Glu | c.3393C > G | NR | 1 (1.1) | BRCA2 | T | C0 | - |

| p. Lys1183Arg | c.3548A > G | CN | 34 (36.2) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | T | C0 | rs16942 |

| p. Ile1275Val | c.3823A > G | CU | 8 (8.5) | - | T | C0 | rs80357280 |

| p. Glu1586Gly | c.4757A > G | NR | 1 (1.1) | - | NT | C0 | - |

| p. Ser1613Gly | c.4837A > G | CN | 33 (35.1) | BRCA1/BRCA# | T | C0 | rs1799966 |

| p. Met1652Thr | c.4955 T > C | CU | 1 (1.1) | - | NT | C25 | rs80356968 |

| BRCA2 | |||||||

| p. Tyr42Cys | c.125A > G | CU(BIC) | 1 (1.1) | - | T | C0 | rs4987046 |

| p. Asn289His | c.865A > C | CN | 5 (5.3) | BRCA2 | NT | C0 | rs766173 |

| p. His372Asn | c.1114C > A | CN | 24 (4.2) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | T | C0 | rs144848 |

| p. Arg858Ile | c.2578 G > T | NR | 1 (1.1) | BRCA2 | T | C0 | - |

| p. Asn991Asp | c.2971A > G | CN | 4 (4.2) | BRCA2 | T | C0 | rs1799944 |

| p.Q1063K | c.3187C > A | NR | 1 (1.1) | - | T | C0 | - |

| p. Asp1420Tyr | c.4258 G > A | CN | 1 (1.1) | BRCA2 [32] | T | C0 | rs28897727 |

| p. Met1915Thr | c.5744 T > C | CU | 1 (1.1) | - | T | C0 | rs4987117 |

| p. Ser2098Phe | c.6749C > T | CU | 1 (1.1) | - | T | C0 | rs80358867 |

| p. Arg2108His | c.6323 G > A | CU | 1.(1.1) | - | T | C0 | rs35029074 |

| p. Ala2466Val | c.7397C > T | CU | 37 (39.4) | BRCA1/BRCA2# | NT | C0 | rs169547 |

| p. Asn2486Lys | c.7919 T > G | NR | 1(1.1) | - | T | C0 | - |

| p. Ile2490Thr | c.7469 T > C | CU | 6 (6.3) | - | NT | C0 | rs11571707 |

| p. Asp2723His | c.8167 G > C | CU | 1 (1.1) | - | NT | C65 | rs41293511 |

| p. Ile3412Val | c.10690A > G | CU | 3 (3.2) | - | T | C0 | rs1801426 |

NR, Not Reported CU, Clinically Unknown; CN, clinically not important, in Breast Information Core database (BIC), http://research.nhgri.nih.gov/bic/;

In bold missense predict deleterious; NT, Not Tolerated; T, Tolerated; Align-GVGD grade between C0 and C65; Co-occurrence: # two or more patients.

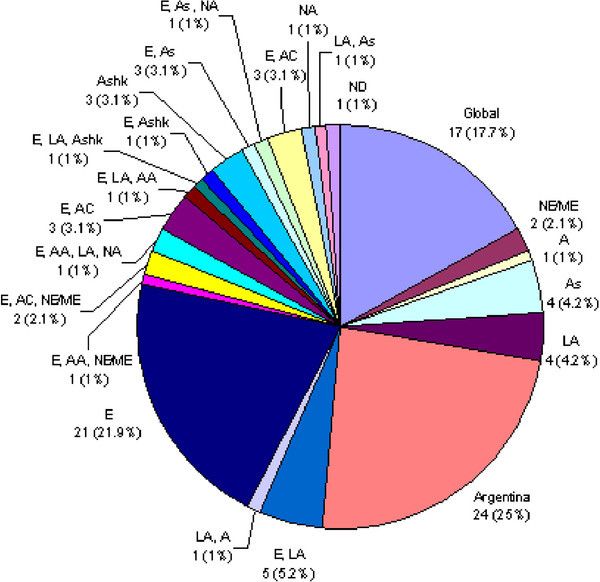

In agreement with the complex population history of Argentina, the BRCA1/2 mutations detected in this BOC series were associated with diverse geographic/ethnic backgrounds (Figure 1 and online Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2). Of the 96 detected variants, 25 (26%) are not reported in the BIC, in HapMap [47] and in the current literature, and are thus putatively unique for Argentina, 17 (17.7%) were reported worldwide (at least 3 continents), 4 (4.2%) were reported only in Latin-America. The remaining variants comprise mutations previously detected in Europe, Asia and North America. (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2). The putative Latin American variants include p. Ile2490Thr in BRCA2, a modestly penetrant variant that might contribute to sporadic breast cancer risk, listed as CU in the BIC, originally described in a Caribbean patient [48] and reported almost 100 times in the BIC, frequently associated to Latin American probands. In this line, several novel variants were previously observed in Argentina in genes related to other hereditary syndromes and might be regarded as putatively regional or influenced by founding events, [49–51]. In the present case series this mutation recurred in six cases (Table 4, Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Worldwide occurrence of 96 BRCA1/2 variants detected in 94 non-Ashkenazi Argentinean BOC patients.Global, as defined in BIC or when reported in at least 3 continents in HapMap or in references; A, African; AA, African American; AC, American Caucasian; As, Asian; Ashk, Ashkenazi; E, European; LA, Latin American; NA, Native American; NE/ME, Near Eastern/Middle Eastern; ND, not determined.

Two other mutations related to South American ethnicity deserve mention: 1) BRCA1 IVS7 + 37 del14bp(TTTTCTTTTTTTTT), not listed in BIC but found in 10/42 families from Uruguay (including one with a pathogenetic mutation in BRCA2) [38], and in a patient from Chile [37]; and 2) BRCA2 IVS16-14 T > C, reported in a patient from Uruguay [38] and detected in 31 of our patients (including 4 with identified pathogenic mutations).

Conclusions

The present study is the first reporting the spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in an Argentinean BOC series, based on the analysis of the coding sequences and exon-intron boundaries of both genes. Given that the rates of BC incidence and mortality in Argentina are among the highest in the world [23, 24], a better understanding of the impact of BRCA1/BRCA2-related disease in Argentinean BOC patients is important for the implementation of prevention and/or early detection strategies. In our case series selected for early diagnosis with no FH or for FH independently of age at diagnosis, the overall detection rate of bona fide pathogenetic mutations was quite high (38/134, 28.3%). This could rise to 35.8% (48/134) including the missense mutations suspected to confer increasing risk of breast cancer.

Although global and European sequence variants contribute to near 45% of the detected BRCA1/2 variation, the significant fraction of new variants putatively unique for Argentina detected in the present study might suggest the presence of a Native American genetic component, not yet genetically characterized, that it in recent centuries has come to admixture with alleles mostly of European origin.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: Table S1:BRCA1 sequence variants identified in Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer cases [38, 52–57]. (DOC 25 KB)

Additional file 2: Table S2:BRCA2 sequence variants identified in Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer cases [58, 59]. (DOC 318 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Ulises Orlando and Paula Maloberti for their informatic scientific support. This work was supported by CONICET (112-200801-01976) http://www.conicet.gov.ar/, Podestá; UBA (M059, 20020090200030) Podestá http://www.uba.ar/homepage.php; FONCyT (PICT-2010-0498) Podesta, http://www.agencia.mincyt.gov.ar/. INC (Resolución Ministerial (N 148/12) http://www.msal.gov.ar/inc/novedades-proy-invest.php, Podestá, Fundacion Bunge y Born Solano/Podesta and AIRC and MIUR 60% for activities developed at the Aging Research Center (CeSI) of the “G. d’Annunzio” University Foundation by Professor Mariani-Constantini. Collaboration between “G. d’Annunzio” University and the University of Buenos Aires is in the framework of the activities developed by CeSI as a Special Consultant of ECOSOC of the United Nations. The collaboration is supported by funds for personnel exchange, research and travel provided by the “G. d’Annunzio” University.

Abbreviations

- BOC

Breast/ovarian cancer

- FH

Family history

- BC

Breast cancer

- OC

Ovarian cancer

- BIC

Breast Cancer Information Core

- EO

Early onset

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- HO

Homozygosis

- A

African

- AA

American African

- AC

American Caucasian

- As

Asian

- Ashk

Ashkenazi

- E

European

- LA

Latin American

- NA

Native American

- NE/ME

Near Eastern/Middle Eastern

- ND

Not Determined

- D

Deleterious

- CU

Clinically Unknown

- CN

Clinically No important

- NR

Not reported

- NT

Not tolerated

- T

Tolerated

- HGVS

Human Genome Variation Society.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare not competing interests.

Author’s contribution

ARS: Contributed to study conception and design, and acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data; and drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. GA: Contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data; and drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. DD: Contributed to sample preparation and genetic analysis, and participate in data analysis. SV: Carried out genetic analysis, data analysis coordinated data collection. MIN: Contributed to sample preparation and genetic analysis, EA: participated clinically in the diagnosis and follow up of patients and sample provision. SC: Contributed to sample preparation and provision. RDC: Critically reviewed the manuscript and participated clinically in the diagnosis and follow up of patients and sample provision and drafted the manuscript. RMC: Contributed to study conception and design, and interpretation of data; and drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. EJP: Contributed to study conception and design, and interpretation of data; and drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Angela Rosaria Solano, Email: drsolanoangela@gmail.com.

Gitana Maria Aceto, Email: gaceto@unich.it.

Dreanina Delettieres, Email: dreaninad@gmail.com.

Serena Veschi, Email: veschi@unich.it.

Maria Isabel Neuman, Email: isaneuman2003@yahoo.com.

Eduardo Alonso, Email: ealonso@intramed.net.ar.

Sergio Chialina, Email: schialina@stem.com.ar.

Reinaldo Daniel Chacón, Email: rchaconbadaracco@yahoo.com.ar.

Mariani-Costantini Renato, Email: rmc@unichi.it.

Ernesto Jorge Podestá, Email: ernestopodesta@yahoo.com.ar.

References

- 1.Easton DF. Familial risks of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2002;4(5):179–181. doi: 10.1186/bcr448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2318–2324. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2318::AID-CNCR21>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, Liu Q, Cochran C, Bennett LM, Ding W, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, Collins N, Gregory S, Gumbs C, Micklem G. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378(6559):789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Narod SA. BRCA mutations in the management of breast cancer: the state of the art. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(12):702–707. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trainer AH, Lewis CR, Tucker K, Meiser B, Friedlander M, Ward RL. The role of BRCA mutation testing in determining breast cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(12):708–717. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Breast Cancer Information Core databasehttp://researcnhgrinihgov/bic

- 8.Kurian AW. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations across race and ethnicity: distribution and clinical implications. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22(1):72–78. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328332dca3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy-Lahad E, Catane R, Eisenberg S, Kaufman B, Hornreich G, Lishinsky E, Shohat M, Weber BL, Beller U, Lahad A, Halle D. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel: frequency and differential penetrance in ovarian cancer and in breast-ovarian cancer families. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(5):1059–1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charrow J. Ashkenazi Jewish genetic disorders. Fam Cancer. 2004;3(3–4):201–206. doi: 10.1007/s10689-004-9545-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langston AA, Malone KE, Thompson JD, Daling JR, Ostrander EA. BRCA1 mutations in a population-based sample of young women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(3):137–142. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601183340301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Sanjose S, Leone M, Berez V, Izquierdo A, Font R, Brunet JM, Louat T, Vilardell L, Borras J, Viladiu P, Bosch FX, Lenoir GM, Sinilnikova OM. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in young breast cancer patients: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2003;106(4):588–593. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Toh GT, Kang P, Lee SS, Lee DS, Lee SY, Selamat S, Mohd Taib NA, Yoon SY, Yip CH, Teo SH. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Malaysian women with early-onset breast cancer without a family history. PLoS One. 2008;3(4):e2024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans DG, Moran A, Hartley R, Dawson J, Bulman B, Knox F, Howell A, Lalloo F. Long-term outcomes of breast cancer in women aged 30 years or younger, based on family history, pathology and BRCA1/BRCA2/TP53 status. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(7):1091–1098. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartsmann G. Breast cancer in South America: challenges to improve early detection and medical management of a public health problem. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(18 Suppl):118S–124S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Ray N, Rojas W, Parra MV, Bedoya G, Gallo C, Poletti G, Mazzotti G, Hill K, Hurtado AM, Camrena B, Nicolini H, Klitz W, Barrantes R, Molina JA, Freimer NB, Bortolini MC, Salzano FM, Petzl-Erler ML, Tsuneto LT, Dipierri JE, Alfaro EL, Bailliet G, Bianchi NO, Llop E, Rothhammer F, Excoffier L, Ruiz-Linares A. Geographic patterns of genome admixture in Latin American Mestizos. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(3):e1000037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes MC, Costa MM, Borojevic R, Monteiro AN, Vieira R, Koifman S, Koifman RJ, Li S, Royer R, Zhang S, Narod SA. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients from Brazil. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(3):349–353. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9378-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jara L, Ampuero S, Santibanez E, Seccia L, Rodriguez J, Bustamante M, Martinez V, Catenaccio A, Lay-Son G, Blanco R, Reyes JM. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a South American population. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2006;166(1):36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallardo M, Silva A, Rubio L, Alvarez C, Torrealba C, Salinas M, Tapia T, Faundez P, Palma L, Riccio ME, Paredes H, Rodriguez M, Cruz A, Rousseau C, King MC, Camus M, Alvarez M, Carvallo P. Incidence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in 54 Chilean families with breast/ovarian cancer, genotype-phenotype correlations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;95(1):81–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-9047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vidal-Millan S, Taja-Chayeb L, Gutierrez-Hernandez O, Ramirez Ugalde MT, Robles-Vidal C, Bargallo-Rocha E, Mohar-Betancourt A, Duenas-Gonzalez A. Mutational analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in Mexican breast cancer patients. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30(5):527–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liede A, Jack E, Hegele RA, Narod SA. A BRCA1 mutation in Native North American families. Hum Mutat. 2002;19(4):460. doi: 10.1002/humu.9027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weitzel JN, Lagos VI, Herzog JS, Judkins T, Hendrickson B, Ho JS, Ricker CN, Lowstuter KJ, Blazer KR, Tomlinson G, Scholl T. Evidence for common ancestral origin of a recurring BRCA1 genomic rearrangement identified in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(8):1615–1620. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manual operativo de evaluacón clínica mamaria. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atlas de mortalidad por cáncer en Argentina. 2003. pp. 1997–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sala A, Penacino G, Carnese R, Corach D. Reference database of hypervariable genetic markers of Argentina: application for molecular anthropology and forensic casework. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(8):1733–1739. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19990101)20:8<1733::AID-ELPS1733>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solano AR, Dourisboure RJ, Weitzel J, Podesta EJ. A cautionary note: false homozygosity for BRCA2 6174delT mutation resulting from a single nucleotide polymorphism masking the wt allele. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10(6):395–397. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aceto GM, Solano AR, Neuman MI, Veschi S, Morgano A, Malatesta S, Chacon RD, Pupareli C, Lombardi M, Battista P, Marchetti A, Mariani-Costantini R, Podesta EJ. High-risk human papilloma virus infection, tumor pathophenotypes, and BRCA1/2 and TP53 status in juvenile breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;122(3):671–683. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tonin P, Weber B, Offit K, Couch F, Rebbeck TR, Neuhausen S, Godwin AK, Daly M, Wagner-Costalos J, Berman D, Grana G, Fox E, Kane MF, Kolodner RD, Krainer M, Haber DA, Struewing JP, Warner E, Rosen B, Lerman C, Peshkin B, Norton L, Serova O, Foulkes WD, Garber JE, et al. Frequency of recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish breast cancer families. Nat Med. 1996;2(11):1179–1183. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathe E, Olivier M, Kato S, Ishioka C, Hainaut P, Tavtigian SV. Computational approaches for predicting the biological effect of p53 missense mutations: a comparison of three sequence analysis based methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(5):1317–1325. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng PC, Henikoff S. Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res. 2002;12(3):436–446. doi: 10.1101/gr.212802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank TS, Deffenbaugh AM, Reid JE, Hulick M, Ward BE, Lingenfelter B, Gumpper KL, Scholl T, Tavtigian SV, Pruss DR, Critchfield GC. Clinical characteristics of individuals with germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2: analysis of 10,000 individuals. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(6):1480–1490. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.6.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abeliovich D, Kaduri L, Lerer I, Weinberg N, Amir G, Sagi M, Zlotogora J, Heching N, Peretz T. The founder mutations 185delAG and 5382insC in BRCA1 and 6174delT in BRCA2 appear in 60% of ovarian cancer and 30% of early-onset breast cancer patients among Ashkenazi women. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(3):505–514. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wacholder S, Hartge P, Prentice R, Garcia-Closas M, Feigelson HS, Diver WR, Thun MJ, Cox DG, Hankinson SE, Kraft P, Rosner B, Berg CD, Brinton LA, Lissowska J, Sherman ME, Chlebowski R, Kooperberg C, Jackson RD, Buckman DW, Hui P, Pfeiffer R, Jacobs KB, Thomas GD, Hoover RN, Gail MH, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ. Performance of common genetic variants in breast-cancer risk models. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(11):986–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hutchinson L. Screening: BRCA testing in women younger than 50 with triple-negative breast cancer is cost effective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7(11):611. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minami CA, Chung DU, Chang HR. Management options in triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2011;5:175–199. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S6562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwon JS, Gutierrez-Barrera AM, Young D, Sun CC, Daniels MS, Lu KH, Arun B. Expanding the criteria for BRCA mutation testing in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4214–4220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Hormazabal P, Gutierrez-Enriquez S, Gaete D, Reyes JM, Peralta O, Waugh E, Gomez F, Margarit S, Bravo T, Blanco R, Diez O, Jara L. Spectrum of BRCA1/2 point mutations and genomic rearrangements in high-risk breast/ovarian cancer Chilean families. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;126(3):705–716. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delgado L, Fernandez G, Grotiuz G, Cataldi S, Gonzalez A, Lluveras N, Heguaburu M, Fresco R, Lens D, Sabini G, Muse IM. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Uruguayan breast and breast-ovarian cancer families. Identification of novel mutations and unclassified variants. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;128(1):211–218. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weitzel JN, Lagos V, Blazer KR, Nelson R, Ricker C, Herzog J, McGuire C, Neuhausen S. Prevalence of BRCA mutations and founder effect in high-risk Hispanic families. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(7):1666–1671. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torres D, Rashid MU, Gil F, Umana A, Ramelli G, Robledo JF, Tawil M, Torregrosa L, Briceno I, Hamann U. High proportion of BRCA1/2 founder mutations in Hispanic breast/ovarian cancer families from Colombia. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103(2):225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9370-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machackova E, Foretova L, Lukesova M, Vasickova P, Navratilova M, Coene I, Pavlu H, Kosinova V, Kuklova J, Claes K. Spectrum and characterisation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deleterious mutations in high-risk Czech patients with breast and/or ovarian cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vega A, Campos B, Bressac-De-Paillerets B, Bond PM, Janin N, Douglas FS, Domenech M, Baena M, Pericay C, Alonso C, Carracedo A, Baiget M, Diez O. The R71G BRCA1 is a founder Spanish mutation and leads to aberrant splicing of the transcript. Hum Mutat. 2001;17(6):520–521. doi: 10.1002/humu.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldgar DE, Easton DF, Deffenbaugh AM, Monteiro AN, Tavtigian SV, Couch FJ. Integrated evaluation of DNA sequence variants of unknown clinical significance: application to BRCA1 and BRCA2. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(4):535–544. doi: 10.1086/424388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirkovic N, Marti-Renom MA, Weber BL, Sali A, Monteiro AN. Structure-based assessment of missense mutations in human BRCA1: implications for breast and ovarian cancer predisposition. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3790–3797. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee MS, Green R, Marsillac SM, Coquelle N, Williams RS, Yeung T, Foo D, Hau DD, Hui B, Monteiro AN, Glover JN. Comprehensive analysis of missense variations in the BRCT domain of BRCA1 by structural and functional assays. Cancer Res. 2010;70(12):4880–4890. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tavtigian SV, Deffenbaugh AM, Yin L, Judkins T, Scholl T, Samollow PB, de Silva D, Zharkikh A, Thomas A. Comprehensive statistical study of 452 BRCA1 missense substitutions with classification of eight recurrent substitutions as neutral. J Med Genet. 2006;43(4):295–305. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Schaffner SF, Yu F, Peltonen L, Dermitzakis E, Bonnen PE, Altshuler DM, Gibbs RA, de Bakker PI, Deloukas P, Gabriel SB, Gwilliam R, Hunt S, Inouye M, Jia X, Palotie A, Parkin M, Whittaker P, Yu F, Chang K, Hawes A, Lewis LR, Ren Y, Wheeler D, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467(7311):52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Offit K, Levran O, Mullaney B, Mah K, Nafa K, Batish SD, Diotti R, Schneider H, Deffenbaugh A, Scholl T, Proud VK, Robson M, Norton L, Ellis N, Hanenberg H, Auerbach AD. Shared genetic susceptibility to breast cancer, brain tumors, and Fanconi anemia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(20):1548–1551. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Rosa M, Dourisboure RJ, Morelli G, Graziano A, Gutierrez A, Thibodeau S, Halling K, Avila KC, Duraturo F, Podesta EJ, Izzo P, Solano AR. First genotype characterization of Argentinean FAP patients: identification of 14 novel APC mutations. Hum Mutat. 2004;23(5):523–524. doi: 10.1002/humu.9237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chialina SG, Fornes C, Landi C, de la Vega Elena CD, Nicolorich MV, Dourisboure RJ, Solano A, Solis EA. Microsatellite instability analysis in hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer using the Bethesda consensus panel of microsatellite markers in the absence of proband normal tissue. BMC Med Genet. 2006;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dourisboure RJ, Belli S, Domenichini E, Podesta EJ, Eng C, Solano AR. Penetrance and clinical manifestations of non-hotspot germline RET mutation, C630R, in a family with medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2005;15(7):668–671. doi: 10.1089/thy.2005.15.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ginsburg OM, Dinh NV, To TV, Quang LH, Linh ND, Duong BT, Royer R, Llacuachaqui M, Tulman A, Vichodez G, Li S, Love RR, Narod SA. Family history, BRCA mutations and breast cancer in Vietnamese women. Clin Genet. 2010;80(1):89–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamel N, Feng BJ, Foretova L, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Narod SA, Imyanitov E, Sinilnikova O, Tihomirova L, Lubinski J, Gronwald J, Gorski B, Hansen TO, Nielsen FC, Thomassen M, Yannoukakos D, Konstantopoulou I, Zajac V, Ciernikova S, Couch FJ, Greenwood CM, Goldgar DE, Foulkes WD. On the origin and diffusion of BRCA1 c.5266dupC (5382insC) in European populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;19(3):300–306. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Keshavarzi F, Javadi GR, Zeinali S. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in 85 Iranian breast cancer patients. Fam Cancer. 2012;11(1):57–67. doi: 10.1007/s10689-011-9477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De Silva W, Karunanayake EH, Tennekoon KH, Allen M, Amarasinghe I, Angunawala P, Ziard MH. Novel sequence variants and a high frequency of recurrent polymorphisms in BRCA1 gene in Sri Lankan breast cancer patients and at risk individuals. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Spurdle AB, Lakhani SR, Healey S, Parry S, Da Silva LM, Brinkworth R, Hopper JL, Brown MA, Babikyan D, Chenevix-Trench G, Tavtigian SV, Goldgar DE. Clinical classification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 DNA sequence variants: the value of cytokeratin profiles and evolutionary analysis–a report from the kConFab Investigators. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1657–1663. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Judkins T, Hendrickson BC, Deffenbaugh AM, Eliason K, Leclair B, Norton MJ, Ward BE, Pruss D, Scholl T. Application of embryonic lethal or other obvious phenotypes to characterize the clinical significance of genetic variants found in trans with known deleterious mutations. Cancer Res. 2005;65(21):10096–10103. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Claes K, Poppe B, Coene I, Paepe AD, Messiaen L. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutation spectrum and frequencies in Belgian breast/ovarian cancer families. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(6):1244–1251. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhi X, Szabo C, Chopin S, Suter N, Wang QS, Ostrander EA, Sinilnikova OM, Lenoir GM, Goldgar D, Shi YR. BRCA1 and BRCA2 sequence variants in Chinese breast cancer families. Hum Mutat. 2002;20(6):474. doi: 10.1002/humu.9083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1:BRCA1 sequence variants identified in Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer cases [38, 52–57]. (DOC 25 KB)

Additional file 2: Table S2:BRCA2 sequence variants identified in Argentinean breast/ovarian cancer cases [58, 59]. (DOC 318 KB)