Summary

ATP-gated P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels are cation-selective, trimeric ligand-gated ion channels unrelated in amino acid sequence. Nevertheless, initial crystal structures of the P2X4 receptor and acid-sensing ion channel 1a in resting/closed and in non conductive/desensitized conformations, respectively, revealed common elements of architecture. Recent structures of both channels have revealed the ion channels in open conformations. Here we focus on common elements of architecture, conformational change and ion permeation, emphasizing general principles of structure and mechanism in P2X receptors and in acid-sensing ion channels and showing how these two sequence-disparate families of ligand-gated ion channel harbor unexpected similarities when viewed through a structural lens.

Introduction

In the nervous system, rapid signaling between cells on the subsecond to seconds time-scale involves the release of neurotransmitter from one cell and the detection of the transmitter on the same or adjacent cells by neurotransmitter- or ligand-gated ion channels 1. There are four major families of ligand-gated ion channels: trimeric ATP-gated P2X receptors 2 and acid sensing ion channels 3, 4; tetrameric ionotropic glutamate receptors 5, 6 and pentameric Cys-loop receptors 7, 8. Here we will focus on unanticipated relationships of protein architecture and of conformational changes associated with ion channel gating in P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels.

Clues from physiology experiments long preceded the cloning of the genes and further molecular characterization of both P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels. Early studies carried out in the 1950s provided the first hints that ATP was an extracellular messenger 9 and experiments by Krishtal in the early 1980s gave the initial evidence of proton activated ion channels 10. Firm acceptance of ATP as a transmitter for chemical signaling did not occur until the 1970s 11, however, and cloning of the receptor genes, together with in-depth molecular characterization, did not occur until the 1990s, ultimately revealing that there are seven P2X receptor subtypes (P2X1-7) 12–14. Each of these receptor subtypes has unique gating and pharmacological properties and, in many instances, two subtypes assemble as heterotrimeric complexes to form the native receptors found in vivo 15. In the same period of wide-spread gene cloning of the 1990s, the genes for ASICs were identified 16, 17, with initial sequence analysis demonstrating that ASICs are members of the superfamily of ion channel proteins that includes the epithelial sodium channel and the degenerin channels 4. Despite extensive analysis of the protein sequences for P2X receptors and ASICs, there were no indications that these two families of ligand-gated ion channel harbor common elements of three-dimensional architecture and mechanism.

P2X receptors and ASICs are cation channels, with the former permeable to Na+, K+ and Ca2+ 14 whereas the latter exhibit modest selectivity of Na+ over K+ and also, for selected channel subtypes, showing permeability to Ca2+ 18. In several instances, however, both P2X receptors and ASICs appear to show dynamic ion selectivity 19. Indeed, the dynamic selectivity or pore-dilation of P2X receptors has been a topic of much debate and the underlying mechanism for these striking phenomena, in both families of ion channel, has proven elusive. The time course of channel activation upon exposure to agonist, ATP for P2X and protons for ASICs, also varies widely between the various subtypes of each receptor family, with P2X1, P2X3, and ASIC1a showing rapid and profound desensitization and P2X2, P2X4, P2X7 and ASIC2a yielding slower and incomplete desensitization, as several examples 14,18, 20. Thus a major challenge in mapping the conformational changes associated with channel gating involves stabilizing the agonist bound state in an open channel, non-desensitized conformation.

Receptor and subunit architectures

Crystal structures of the zebrafish P2X4 receptor in an apo, closed channel state and the chicken ASIC1a channel in a low pH, non conducting, desensitized state demonstrate that both channels have six transmembrane segments – two per subunit, short N- and C-termini on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, and large glycosylated and disulfide bond-rich extracellular domains that protrude as much as 80 Å from the predicted position of the membrane bilayer (Figure 1) 21–23. Despite differences in the overall structures of the trimeric receptors, we nevertheless see that in these non conductive states the transmembrane helices are arranged in similar conformations 23. Moreover, on the extracellular side of the membrane, for both ion channels, the transmembrane helices are connected to β-strands that are, in turn, part of large β sheets that wrap around the 3-fold axes of symmetry. Inspection of the individual subunits also shows that whereas the overall structures and folds are largely different, there nevertheless is a central β-sheet with similar β-strand topology – the palm domain in ASIC and the body domain in P2X – that forms their fundamental cores 21–23. Surrounding this core are additional elements of structure that are involved in ligand binding and ligand-dependent conformational changes.

Figure 1.

P2X4 and ASIC1a architecture, domain organization and agonist or toxin binding site. a. Zebrafish P2X4 receptor structure in the apo, closed state, color coded by domain. b. Domain organization of a single P2X4 apo subunit. c. Domain organization of cASIC1a. d. Chicken ASIC1a structure in the low pH, desensitized, non conductive state. e. P2X4 structure in the ATP-bound, open channel state. f. cASIC1a bound to psalmotoxin (PcTx1) at low pH. g. cASIC1a bound to PcTx1 at high pH.

Agonist and gating modifier binding sites

Subsequent crystal structures of the zebrafish P2X4 receptor in complex with the agonist ATP and the chicken ASIC1a in complex with psalmotoxin (PcTx1), an inhibitor cysteine knot polypeptide toxin from a South American tarantula, allowed for identification of the canonical agonist binding site and of the toxin binding site, respectively (Figure 2) 24, 25. Here we define PcTx1 as a gating modifier rather than an agonist because even though this small peptide promotes the opening of the chicken ASIC1a channel, it acts instead as an antagonist on other ASICs, presumably by stabilizing the channel in a proton-bound, desensitized-like state 26–28.

Figure 2.

Binding sites for ATP and toxin in P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a, respectively, flank the central β-sheet ‘scaffold’ domains. a. Close up of the intersubunit binding site for ATP in the P2X4 receptor. b. Close up of the intersubunit binding site for PcTx1. ATP and the toxin are shown in sphere representation, color coded by atom type (carbon: gray; oxygen: red; nitrogen: blue; sulfur: yellow). The proteins are colored as in Figure 1.

There are three ATP sites on the P2X4 receptor situated between adjacent subunits and located about 40 Å from the extracellular side of the membrane bilayer 24. Each of the ATP molecules is cradled between the head, left flipper and upper body domains of one subunit (A) and the dorsal fin and lower body domain of a neighboring subunit (B) which together define an ATP binding motif that has not been seen before. Interestingly, the triphosphate moiety is bound primarily by basic residues located on subunits A and B whereas the adenosine group interacts nearly exclusively with side chain and main chain atoms on subunit B. The ribose group, by contrast, is near to the dorsal fin on subunit B yet also leaves its hydroxyl groups exposed to solution. Taken together, the crystallographically determined binding site for ATP on the P2X4 receptor is in good agreement with extensive mutagenesis and chemical modification data 29, 30.

There are three equivalent binding sites for PcTx1 on chicken ASIC1a, positioned approximately 50 Å from the membrane bilayer and localized at a subunit interface 25,31. The toxin molecules insert an arginine rich loop into the negatively charged ‘acidic pocket’, forming multiple interactions with the thumb and the finger domains, while aromatic residues of the toxin participate in non polar interactions with key residues on the thumb domain. Importantly, the toxin binding site mapped from these structural data is in harmony with previous mutagenesis, binding and electrophysiological data as well as with a recent structure of an inactive form of chicken ASIC1a with PcTx1 28, 31.

Despite the many differences in the ligands – ATP and PcTx1 – and their cognate binding sites on the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a, respectively, it is striking to note that both molecules bind to sites on the ion channels that are 40–50 Å from the membrane bilayer, that each are at or near subunit interfaces, and that both binding sites are defined by elements of protein structure that flank the central β-sheet domains – the ‘body domain’ in the case of P2X4 and the ‘palm domain’ for ASIC1a.

Vestibules and fenestrations – portals for ions

Sagittal section slices along the 3-fold axis of both the P2X receptor and ASIC1a reveal several remarkable, similar features (Figure 3). First, inspection of the extracellular domain demonstrates that there are several vestibules or cavities beginning with the ‘upper vestibule’, the ‘central vestibule’, the ‘extracellular vestibule’ - which is immediately proximal to the ion channel pore - and finally, on the intracellular side of the membrane, the ‘cytoplasmic vestibule’ 21–23. When the solvent accessible protein surface is coded by electrostatic potential, we further notice that for both ion channels, the central and extracellular vestibules are highly electronegative, a consequence of their being lined by acidic residues and a molecular feature contributing to their selectivity for cations over anions (Figures 3a and 3d). In fact, we note that in the P2X4 receptor the central vestibule is a site of Gd3+ binding 21 and, in the ASIC1a channel, the highly acidic central vestibule is also a likely site of cation binding 31.

Figure 3.

The P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a harbor cavities, vestibules and lateral fenestrations. a. Surface representation of the P2X4 receptor color coded by electrostatic potential. ‘HOLE’ representation 35 of the apo, closed (b) and ATP-bound, open (c) states of the P2X4 receptor, showing a large pore in the ATP-bound state. d. Surface representation of ASIC1a also colored by electrostatic potential. ‘HOLE’ representations of ASIC1a in the low pH desensitized state (e), the high pH PcTx1 bound state (f) and the low pH PcTx1 bound state, illustrating a large non-selective pore in (f) and small, asymmetric and selective pore in (g). In both the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a ions enter and exit the pore from the extracellular site of the membrane by way of lateral fenestrations. For both channels a possible ion pathway along the 3-fold axis within the extracellular domain remains occluded.

Access by ions to the transmembrane pore could conceivably occur by way of two distinct pathways, one along the 3-fold axis and the second via ‘fenestrations’ or triangle-shaped ‘windows’ located near the base of the extracellular domain and opening directly into the extracellular vestibule. Both the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a have such portals to the pore, and evidence derived from mutagenesis and electrophysiology studies, together with structures of open states of the ion channel pores, shows that on the extracellular side of the membrane ions must enter and exit the pore via these fenestrations 32, 33,24, 25. In agonist or gating modifier bound states of P2X4 and ASIC1a the occlusions along the 3-fold axis remain too small for ions to pass and thus even though ions may ‘percolate’ from the extracellular vestibule into the central vestibule, the pathway from the central vestibule to the extracellular vestibule remains closed in all structures studied to date 24, 25.

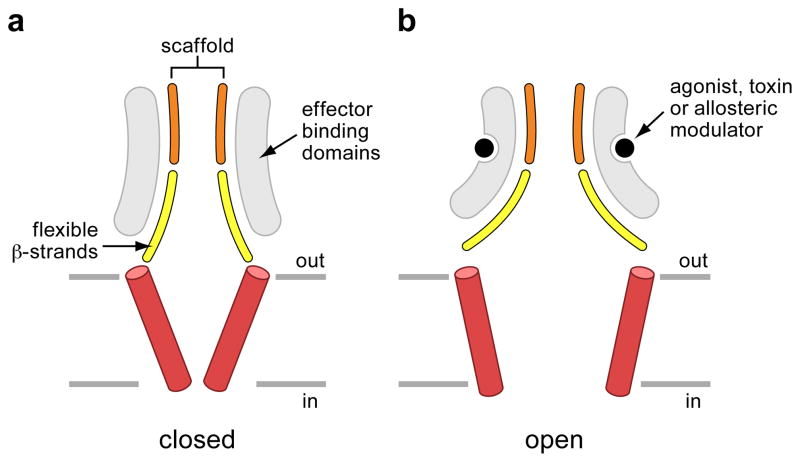

Structural scaffolds and pliable sheets

Comparisons of closed and open states of the P2X4 receptor and of ASIC1a illuminate several remarkable parallels (Figure 4). Upon analysis of the closed and open states of the P2X4 receptor we see that there is a structurally rigid scaffold near the ‘top’ of the extracellular domain composed of the upper body domains of each of the three symmetry-related subunits. Upon ATP binding, the β-strands of the lower body domains flex outward, expanding the extracellular vestibule and, because these β strands are covalently linked to the transmembrane helices, the transmembrane helices also undergo an iris-like expansion, opening a solvent accessible pathway through the ion channel pore 24 (Figures 4a and 5).

Figure 4.

Conformational changes accompanying gating in the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a. a. Superposition of the upper body domain – the ‘scaffold’ - of the apo (gray) and ATP-bound states of the P2X4 receptor showing how the β-strands of the lower body domain flex outward in the ATP-bound state. A superposition of the upper palm and knuckle domains – the ‘scaffold’ – of the low pH desensitized state with the high pH PcTx1 state (b) and the low pH PcTx1 state (c), illustrating how the scaffold domain is relatively immobile whereas the β-strands of the lower palm domain flex outward in the PcTx1 bound states.

Figure 5.

Cartoon schematic illustrating the core domains involved in the ATP-dependent and PcTx1-dependent gating of the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a, respectively. The ‘effector binding domains’ are, as examples, the ‘head’, ‘body’, ‘dorsal fin’ and ‘left flipper’ in the case of the P2X4 receptor and the ‘finger’, ‘thumb’ and ‘palm’ domains of ASIC1a.

Strikingly, when we carry out a similar comparison of ASIC1a in the high and low pH PcTx1-bound states to the low pH, ion channel shut and desensitized state, we also observe that there is an architecturally similar structural scaffold coupled to flexible β strands (Figures 4b, 4c and 5). In the case of ASIC1a, the upper palm domains define the conformationally immobile structural scaffold while the lower palm domains constitute the flexible β-strands. Here, as with the P2X4 receptor, the expansion of the β-strands within the lower palm domain concomitantly results in the expansion of the extracellular vestibule which in turn induces conformational changes in the transmembrane helices lining the ion channel pore 25.

Movements of transmembrane helices

In the shut ion channel pores of the P2X receptor in the apo, resting state 21 and ASIC1a in the proton-bound desensitized state 23, a slab of protein ~8 Å thick insulates the extracellular solution from the cytoplasmic milieu, thus defining the physical ion channel gate. By having structures of both receptors in open channel states we can now visualize the conformational changes of the transmembrane helices that remove these occlusions and open ion accessible pathways from one side of the membrane to the other. In the case of the P2X receptor, the agonist-triggered movements involve a simple iris-like rotation and expansion of the transmembrane helices (Figure 4d). TM1 and TM2 move nearly in unison, maintaining extensive interactions, and undergoing only small relative changes in orientation. Most remarkably, in the ATP-bound open state, there are few contacts between subunits within the transmembrane domains and thus not only do these gaps and crevices present likely binding sites for allosteric modulators such as ivermectin, but they also are presumably occupied by lipid molecules. This predicted intimate participation of lipids in turn suggests that they will not only modulate channel function, but they will also define a portion of the ‘walls’ of the ion channel pore 24.

The movements of the transmembrane helices of ASIC1a in going from the non conductive, desensitized state to the high pH and low pH PcTx1-bound open states are qualitatively different from the rearrangements of the P2X4 receptor. In the high pH toxin-bound state (Figure 4e), the TM2 helices have moved from close to the 3-fold axis to positions farther from the 3-fold axis, now forming a 3-fold symmetric single-layer ring of helices together with the TM1 segment, thereby defining a large non-selective pore with a minimum diameter of ~10 Å 25. By visualizing the structure of the high pH, ASIC1a-PcTx1 pore, we provide insight into how ion channels, including ASICs and P2X receptors, can form large and non-selective pores across cellular membranes.

The apparent movements of the TM helices in going from the ASIC1a desensitized state to the low pH toxin-bound state are distinct from those associated with the high pH state. In the low pH state (Figure 4f), not only are the TM1 and TM2 of each subunit asymmetrically arranged around the pore axis, but within each subunit, the relative TM1-TM2 interactions also differ. Thus, while TM1 and TM2 occupy positions on the periphery of the pore that are similar to those seen in the high pH state, TM2 of the C subunit has ‘collapsed’ into the pore, greatly restricting the dimensions of the pore, thus rendering the ion channel highly selective for Na+ over K+. Here we see how a homotrimeric ion channel can harbor an asymmetric, transmembrane ion channel pore 25.

Channel pore and ion selectivity

P2X receptors and ASICs have ion channel pores that are, most generally, non- selective cation pores 14, 18. Inspection of the open P2X4 pore reveals a channel that is largely hydrophobic with a constriction that is ~7 Å in diameter and thus permeant ions are partially, if not fully, hydrated 24. Cation selectivity may be largely endowed by regions flanking the ion channel pore, including the acidic-residue enriched and highly electrostatically negative extracellular and central vestibules, as well as residues lining the extracellular fenestrations 32, 34.

In the case of ASICs, the high pH PcTx1-bound pore is large enough to pass organic cations, including N-methyl-D-glucamine. The low pH pore, by contrast, is small, largely hydrophobic and non 3-fold symmetric 25. With dimensions of 4 × 7 Å in cross section, the low pH pore is sufficiently large to allow for passage of partially hydrated Na+ ions but perhaps not large enough for passage of larger cations, such as K+. Thus we hypothesize that the mechanism of ion selectivity in this particular complex is best described by way of a barrier mechanism. Whereas the low pH PcTx1 complex is selective for Na+ over K+, the extent to which it discriminates between Na+ and K+ is actually greater than that observed for ASICs upon activation by transition to low pH, thus the chemical nature and structural composition of the ASIC ion channel activated solely by protons is likely different from that observed in the low pH PcTx1 complex. Future studies are needed to refine the mechanism of ion selectivity in ASICs as well as to define the conformation of the ion channel pore upon transition to low pH.

Conclusion

Crystal structures of the P2X4 receptor and ASIC1a in apo or ATP-bound and desensitized or PcTx1-bound states have not only defined the binding sites of agonist and toxins, respectively, but they have also demonstrated that these two trimeric ion channels share unanticipated mechanisms for ion channel gating that involve a conformationally rigid scaffold coupled to flexible β-strands that are, in turn, connected to the transmembrane ion channel helices (Figure 5).

Highlights.

ATP-activated P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels are trimeric, cation-selective ligand-gated ion channels.

P2X receptors and acid-sensing ion channels are unrelated in amino acid sequence.

The transmembrane pores of the P2X4 receptor and the acid-sensing ion channel 1a are similar in structure.

The P2X4 receptor and the acid-sensing ion channel 1a harbor extracellular and cytoplasmic vestibules and lateral fenestrations.

Both channels have an ‘upper’ β-sheet scaffold and a ‘lower’, flexible β-sheet region that is directly coupled to the ion channel pore.

The P2X4 receptor and the acid sensing ion channel 1a exhibit striking parallels in architecture and mechanism.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cowan WM, Sudhof TC, Stevens CF, editors. Synapses. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khakh BS, North RA. Neuromodulation by extracellular ATP and P2X receptors in the CNS. Neuron. 2012;76:51–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sherwood TW, Frey EN, Askwith CC. Structure and activity of the acid-sensing ion channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C699–710. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00188.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gründer S, Chen X. Structure, function, and pharmacology of acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs): focus on ASIC1a. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2010;2:73–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer ML. Emerging models of glutamate receptor ion channel strucure and function. Structure. 2011;19:1370–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar J, Mayer ML. Functional insights from glutamate receptor ion channel structures. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson AJ, Lester HA, Lummis SC. The structural basis of function in Cys-loop receptors. Q Rev Biophys. 2010;43:449–499. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corringer PJ, et al. Structure and pharmacology of pentameric receptor channels: from bacteria to brain. Structure. 2012;20:941–956. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holton FA, Holton P. The capillary dilator substances in dry powders of spinal roots; a possible role of adenosine triphosphate in chemical transmission from nerve endings. J Physiol. 1954;126:124–140. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishtal OA. The ASICs: Signaling molecules? Modulators? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:477–483. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnstock G. Purinergic nerves. Pharmacol Rev. 1972;24:509–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Valera S, et al. A new class of ligand-gated ion channel defined by P2x receptor for extracellular ATP. Nature. 1994;371:516–519. doi: 10.1038/371516a0. (refs 12–14) Cloning of the first P2X receptor genes and identification as a new class of ligand-gated ion channel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brake AJ, Wagenbach MJ, Julius D. New structural motif for ligand-gated ion channels defined by an ionotropic ATP receptor. Nature. 1994;371:519–523. doi: 10.1038/371519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.North RA. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:1013–1067. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surprenant A, North RA. Signaling at purinergic P2X receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:333–359. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16**.Waldmann R, Champigny G, Bassilana F, Heurteaux C, Lazdunski M. A proton-gated cation channel involved in acid-sensing. Nature. 1997;386:173–177. doi: 10.1038/386173a0. (refs 16–17) Cloning of the first acid-sensing ion channel genes and identification as a new class of ligand-gated ion channel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Anoveros J, Derfler B, Neville-Golden J, Hyman BT, Corey DP. BNaC1 and BNaC2 constitute a new family of human neuronal sodium channels related to degenerins and epithelial sodium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1459–1464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kellenberger S, Schild L. Epithelial sodium channel/degenerin family of ion channels: a variety of functions for a shared structure. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:735–767. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khakh BS, Lester HA. Dynamic selectivity filters in ion channels. Neuron. 1999;23:653–658. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesselager M, Timmermann DB, Ahring PK. pH dependency and desensitization kinetics of heterologously expressed combinations of acid-sensing ion channel subunits. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11006–11015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313507200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21**.Kawate T, Michel JC, Birdsong WT, Gouaux E. Crystal structure of the ATP-gated P2X4 ion channel in the closed state. Nature. 2009;460:592–598. doi: 10.1038/nature08198. (ref 21) Crystal structure of the zebra fish P2X4 receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22**.Jasti J, Furukawa H, Gonzales E, Gouaux E. Structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1 at 1.9 A resolution and low pH. Nature. 2007;449:316–323. doi: 10.1038/nature06163. (ref 22) Crystal structure of the chicken acid-sensing ion channel 1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23*.Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature. 2009;460:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature08218. (ref 23) Crystal structure of the chicken acid sensing ion channel at low pH, in the desensitized state and comparison to the apo, closed state of the zebra fish P2X4 receptor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Hattori M, Gouaux E. Molecular mechanism of ATP binding and ion channel activation in P2X receptors. Nature. 2012;485:207–212. doi: 10.1038/nature11010. (ref 24) Crystal structure of the zebra fish P2X4 receptor in the ATP-bound open state. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25*.Baconguis I, Gouaux E. Structural plasticity and dynamic selectivity of acid-sensing ion channel-spider toxin complexes. Nature. 2012;489:400–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11375. (ref 25) Crystal structures of the chicken acid-sensing ion channel 1a - psalmotoxin complex in non selective and sodium selective states at high and low pH, respectively. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26*.Chen X, Kalbacher H, Grunder S. The tarantula toxin psalmotoxin 1 inhibits acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1a by increasing its apparent H+ affinity. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:71–79. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509303. (refs 26–28) Characterization of the action of psalmotoxin on acid-sensing ion channel 1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen X, Kalbacher H, Grunder S. Interaction of acid-sensing ion channel (ASIC) 1 with the tarantula toxin psalmotoxin 1 is state dependent. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:267–276. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salinas M, et al. The receptor site of the spider toxin PcTx1 on the proton-gated cation channel ASIC1a. J Physiol. 2006;570:339–354. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Browne LE, Jiang LH, North RA. New structure enlivens interest in P2X receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang R, Taly A, Grutter T. Moving through the gate in ATP-activated P2X receptors. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31*.Dawson RJP, et al. Structure of the acid-sensin ion channel 1 in complex with the gating modifier Psalmotoxin 1. Nature Commun. 2012;3 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1917. (ref 31) Crystal structure of chicken acid-sensing ion channel 1a in complex with psalmotoxin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawate T, Robertson JL, Li M, Silberberg SD, Swartz KJ. Ion access pathway to the transmembrane pore in P2X receptor channels. J Gen Physiol. 2011;137:579–590. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samways DS, Khakh BS, Dutertre S, Egan TM. Preferential use of unobstructed lateral portals as the access route to the pore of human ATP-gated ion channels (P2X receptors) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017550108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Samways DSK, Khakh BS, Egan TM. Allosteric modulation of Ca2+ flux in ligand-gated cation channel (P2X4) by actions on lateral portals. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:7594–7602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.322461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Samsom MS. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J Mol Graph. 1996;14:354–360. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]