Abstract

Background

The lack of accuracy in the prediction of vertebral fracture risk from average density measurements, all external factors being equal, may not just be because bone mineral density (BMD) is less than a perfect surrogate for bone strength but also because strength alone may not be sufficient to fully characterize the structural failure of a vertebra. Apart from bone quantity, the regional variation of cancellous architecture would have a role in governing mechanical properties of vertebrae.

Method of Approach

In this study, we estimated various microstructural parameters of the vertebral cancellous centrum based on stereological analysis. An earlier study indicated that within-vertebra variability, measured as the coefficient of variation (COV) of bone volume fraction (BV/TV) or as COV of finite element-estimated apparent modulus (EFE) correlated well with vertebral strength. Therefore, as an extension to our earlier study, we investigated i) whether the relationships of vertebral strength found with COV of BV/TV and COV of EFE could be extended to the COV of other micro-structural parameters and microcomputed tomography-estimated bone mineral density (μCT-BMD) and ii) whether COV of microstructural parameters were associated with structural ductility measures.

Results

COV-based measures were more strongly associated with vertebral strength and ductility measures than average microstructural measures. Moreover, our results support a hypothesis that decreased microstructural variability, while associated with increased strength, may result in decreased structural toughness and ductility.

Conclusions

The current findings suggest that variability-based measures could provide an improvement, as a supplement to clinical BMD, in screening for fracture risk through an improved prediction of bone strength and ductility. Further understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying microstructural variability may help develop new treatment strategies for improved structural ductility.

Keywords: Micro-CT, Vertebrae, Strength, Ductility, Heterogeneity

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is associated with bone mineral density (BMD), but it is often accepted apprehensively in predicting fracture risk and bone strength because of its vague differentiation between fractures in osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic groups [1]. Although amount of bone mass contributes to the strength of bone, it alone cannot account for how the material is distributed in the structure and bone strength prediction models can often be improved when factors additional to BMD are included [2–4]. Therefore, using information about the organization of trabeculae, in addition to bone density, may increase the success in predicting fractures [5].

Previous studies indicated that the integrity of the trabecular centrum plays an important role in determining the strength of a whole vertebral body [6]. Due to the heterogeneity of trabecular bone density and architecture within the vertebral centrum [4, 7], each region may influence the total strength of the vertebra to a different extent. Previous studies on the regional variation of bone density and architectural parameters in human vertebrae [8, 9] reported that failure strength cannot be predicted through analysis of one specific anatomic region and that prediction of vertebral strength can be improved over traditional BMD measurements when the regional variation of architectural parameters is considered. We have previously quantified the regional variation of cancellous bone properties as the coefficient of variation of bone volume fraction (BV/TV) and finite element (FE)-estimated apparent modulus of cancellous bone within a vertebra and have shown that increasing values of these parameters are highly associated with decreased vertebral strength [10].

One of the implications of the relationship between within-vertebra variability of cancellous bone FE modulus and vertebral strength is that such a relationship could be useful in predicting vertebral strength. However, it is often density or microstructural parameters, rather than FE-estimated parameters that are more readily extractable from various images [5, 7, 10–13]. Although the within-vertebra variability of BV/TV determined from microcomputed tomography (μCT) images was found to correlate with vertebral strength, it is not known whether the variability of cancellous microstructural parameters other than BV/TV would correlate with strength. Therefore, one of the objectives of this study was to extend our earlier study [10] and examine the relationship between within-vertebra variability of cancellous bone microstructure and the structural strength of human vertebral bodies.

The increased strength in vertebrae with more homogenous cancellous bone is consistent with a structural design that has the goal of increasing uniaxial stiffness [14] and with the strong correlation between bone stiffness and strength at various hierarchical levels [12, 15–19]. However, homogenization of the structure may result in the loss of weak and strong sites which, when present, would not fail simultaneously under an overload and provide damage-tolerance and ductility to the vertebral structure [20]. Our recent finding that T12-L1 vertebrae, which collapse more often than other vertebrae, have more homogenous cancellous bone than other vertebrae [21] supports the idea that mechanical properties other than ultimate strength are important in determining the risk of vertebral fractures. Therefore, a second objective of this study was to examine if there is evidence that decreased within-vertebra variability of cancellous properties is associated with decreased measures of structural ductility by further analysis of the mechanical test data from our original study [10].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

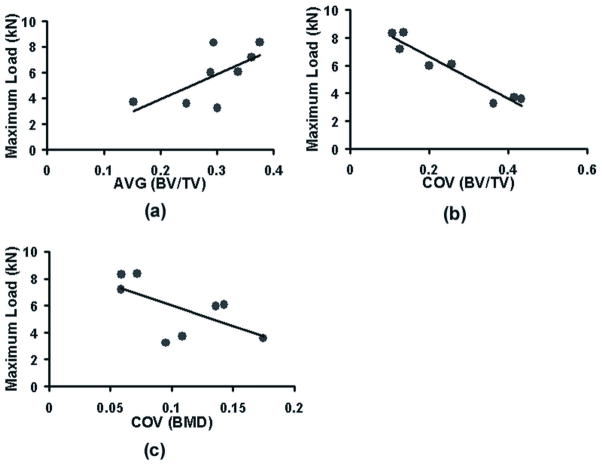

The specimen preparation, μCT scanning, image processing and mechanical test procedures were described in our previous study [10]. Briefly, eight vertebrae (T10~L5) obtained from two human cadavers (78 and 89 yrs, male) were scanned using μCT and six cylindrical biopsy regions (Ø 8 mm × 10 mm) were digitally cored from each vertebral centrum (Figure 1). Thus, a total 48 cylindrical images of cancellous bone were used. A solid radiographic reference was also included in each scan. Bone volume fraction (BV/TV), bone surface area fraction (BS/BV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), connectivity by Euler number (Eu.N), mean intercept length along primary, secondary and tertiary directions (MIL1, MIL2 and MIL3) and degree of anisotropy (DA = MIL1/MIL3) were measured for each digital core using 3D stereology [12]. Then, in order to simulate bone mineral density (BMD) that can be measured in vivo, the images scanned at 119 μm voxel size were re-reconstructed at 1 mm voxel size [22, 23]. The solid radiographic reference was used to convert μCT gray levels to density-based estimates. After this, μCT equivalent of clinical BMD (μCT-BMD) were calculated for each core. Within-vertebra average (Avg) and standard deviation (SD) of the architectural and μCT-BMD parameters were calculated for each vertebral body from 6 digitally cored regions. Within-vertebra coefficient of variation (COV=SD/Avg) was calculated for each parameter as an indication of the variability of these parameters within a vertebral body.

Figure 1.

Regions of digital cores, cylinders of 10 mm length and 8 mm diameter, from which average and variability (COV) measures were estimated for a vertebral body.

The whole vertebra specimens were uniaxially compressed to fracture with a nominal strain rate of 0.01/sec using a servo-hydraulic testing machine (Instron 8501, MA). The height of each vertebra was measured from μCT images. To ensure uniform load distribution, low-temperature melting point Wood’s metal was used to constrain the end plates of vertebrae [24]. Stiffness (K) was estimated as the maximum of the slopes calculated along the load displacement curve before failure. The strength of vertebrae was determined as the maximum load (Fmax) sustained. In addition, ultimate displacement (Δu), the maximum displacement traveled by the cross-head before specimen’s failure, and work to fracture (W), the total amount of work done for fracture, were obtained as measures of structural ductility. Also, post-yield energy (Wpy) was estimated as a ductility measure, where yield point was found using 5% secant stiffness method [25]. In order to assess the variation of structural ductility measures relative to strength, Wpy, W and Δu were normalized with strength to produce post-yield energy to strength ratio (Wpy/Fmax), work to fracture to strength ratio (W/Fmax) and ultimate displacement to strength ratio (Δu/Fmax).

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationship of vertebral body compressive strength and ductility with average and variability of microstructural and BMD parameters.

RESULTS

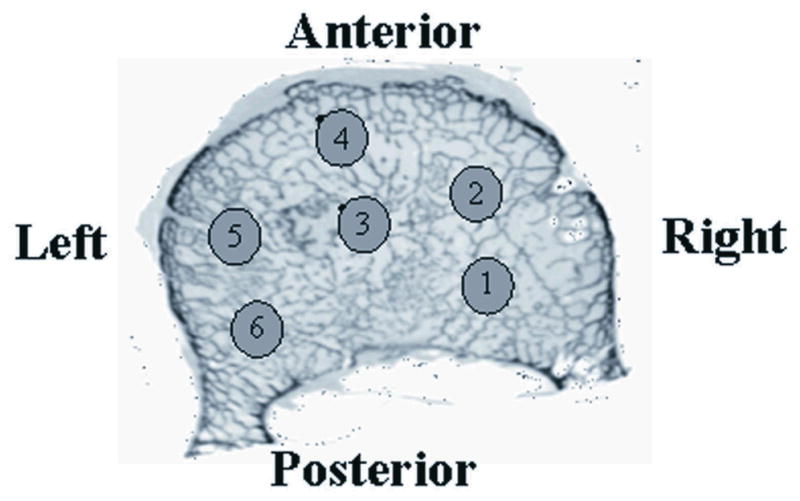

Strength correlated positively (P = 0.039, P = 0.047, P = 0.015) with the average values of Tb.N, MIL1, DA and negatively (P = 0.047) with average Tb.Sp, while the relationships between stiffness and average measures were nonsignificant, except for DA (P = 0.031). Whereas, COV of BV/TV (P = 0.0004), Tb.N (P = 0.0085), Tb.Sp (P = 0.0001) and Eu.N (P = 0.035) negatively correlated with stiffness and COV of BV/TV (P = 0.0002), Tb.N (P = 0.0048), Tb.Sp (P = 0.0007), Eu.N (P = 0.032) and MIL2 (P = 0.035) with strength (Table 1, Figures 2a, 2b). For comparison with the average and COV of BV/TV, a significant negative correlation was found between minimum BV/TV and strength (P = 0.036, r = 0.74).

Table 1.

Coefficients (r) of significant correlations between within-vertebra average (AVG) and variability (COV) of cancellous bone parameters and vertebral body structural strength and ductility parameters.

| S | Fmax | W | Wpy | Δu | W/Fmax | Wpy/Fmax | Δu/Fmax | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV/TV | AVG | +0.76 | |||||||

| COV | −0.94 | −0.96 | +0.74 | +0.82 | |||||

| BS/BV | AVG | ||||||||

| COV | +0.71 | +0.82 | +0.83 | +0.73 | |||||

| Tb.N | AVG | +0.73 | |||||||

| COV | −0.84 | −0.87 | −0.75 | ||||||

| Tb.Sp | AVG | −0.71 | −0.75 | ||||||

| COV | −0.96 | −0.93 | |||||||

| Tb.Th | AVG | ||||||||

| COV | +0.70 | +0.83 | +0.85 | +0.75 | +0.75 | ||||

| Eu.N | AVG | ||||||||

| COV | −0.74 | −0.75 | −0.74 | ||||||

| MIL1 | AVG | +0.71 | +0.72 | ||||||

| COV | |||||||||

| MIL2 | AVG | ||||||||

| COV | −0.74 | +0.73 | +0.71 | +0.77 | |||||

| MIL3 | AVG | ||||||||

| COV | +0.84 | +0.88 | +0.93 | +0.87 | +0.85 | ||||

| DA | AVG | +0.75 | +0.81 | −0.74 | −0.80 | −0.80 | −0.86 | ||

| COV | |||||||||

| μCT-BMD | AVG | +0.71 | |||||||

| COV | −0.72 |

Figure 2.

a) A positive nonsignificant relationship of vertebral strength with average BV/TV was observed whereas b) a strong and negative relationship was found between strength and the coefficient of variation of BV/TV (r = 0.95, P = 0.0002). c) In comparison, the relationship between strength and COV of μCT-BMD was negative but nonsignificant.

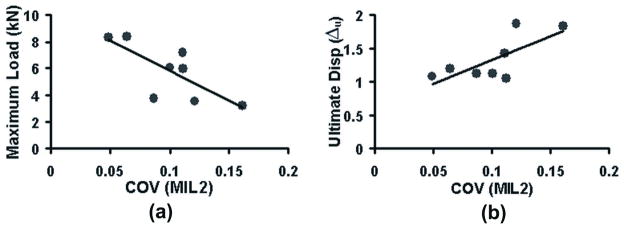

Among ductility parameters, work to fracture significantly increased with average measures of BV/TV (P = 0.027) and MIL1 (P = 0.044) and significantly decreased with average Tb.Sp (P = 0.031). Increasing variability of the microstructure was generally associated with increased values of ductility parameters, except for work to fracture, but this when normalized with strength, again positively associated with increasing microstructural variability. Especially interesting was the case of MIL2 where increasing COV of MIL2 was negatively (P = 0.035) associated with strength but positively associated with ultimate displacement (P = 0.042), Wpy/Fmax (P = 0.048) and Δu/Fmax (P = 0.024) (Table 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

a) Vertebral strength decreased with increasing COV of MIL2 (r = −0.74, P = 0.035) whereas b) ultimate displacement of the vertebra increased with increasing COV of MIL2 (r = 0.75, P = 0.042).

The relationships of within-vertebra average (P = 0.263) and the variability of μCT-BMD (P = 0.100, Figure 2c) with the vertebral strength, although potentially demonstrable with a larger sample size, were not significant in the current sample. However stiffness correlated positively with average (P = 0.047) and negatively with COV (P = 0.045) of μCT-BMD.

DISCUSSION

The main objective in this study was to investigate the relationships between statistical measures of micro-architectural parameters and the strength and ductile behavior of human vertebrae. Since this investigation is an extension to our earlier work [10], most of the limitations discussed in the previous study apply to the current investigation also. In addition, for BMD measurements, we reconstructed images at a typical 1 mm voxel size consistent with previous studies of vertebral mineral density [22] and finite element models [22, 23]. Recognizing that factors other than reconstruction voxel size contribute to resolution [11, 26, 27], our BMD measurements might not accurately reflect clinical CT resolution, hence the acronym μCT-BMD.

In this study we characterized ductility using work to fracture, ultimate displacement, post-yield energy and their ratios relative to strength. Among these parameters, work to fracture is related to both strength and displacement unlike the other ductility parameters considered in this study. Consequently, when work to fracture was normalized with strength, its relationships with the microstructure were similar to those of other ductility parameters. Although the currently employed parameters were sufficient to make our initial point, this work could be expanded to include more rigorous failure criteria. For example, note that the W/Fmax is similar, in principle, to the reciprocal of cushion factor commonly used in evaluating the energy absorption efficiency of cellular materials [28], however, this study did not include the post-maximum load mechanical behavior of the vertebrae.

Our results indicate that an increase in the variability of cancellous microstructure within a vertebra is strongly associated with a decrease in vertebral strength. The stronger association of the vertebral strength with the scatter than with the average of cancellous microstructure suggests that within-vertebra variability of the microstructure may help determine fracture risk in equal bone-mass groups. High variability of the microstructure may indicate presence of relatively weak regions that may be a dominant factor in determining vertebral strength [29]. Minimum BV/TV did negatively correlate with strength but not as strong as COV in the current study.

Our results also indicate that within-vertebra variability of the microstructure (COV of BV/TV and MIL2), while negatively associated with strength, is positively associated with ductility properties (Table 1). This is consistent with the observations that, in engineering and biological materials including bone, increased stiffness and strength of the vertebra comes at the cost of reduced toughness and ductility [30]. Our result is also consistent with previous findings that vertebral fatigue life (related to tolerance for progressive damage, toughness and ductility) and strength are competing properties [4, 31]. The issue of characterization of bone integrity is at least twofold: Finding a more accurate surrogate for bone strength than average density and finding a mechanical parameter(s) that is more representative of a progressive failure process than strength. One implication of the finding that increased microstructural variability is associated with reduced strength but increased ductility is that variability-based parameters can be developed to improve fracture risk prediction from average density-based predictions alone. A potential advantage of using microstructural parameters is the applicability to images such as those measured using histomorphometry or 2D imaging modalities [32] that are not necessarily amenable to complete computational mechanical analysis.

The current results must be considered in the context of a pilot study as the sample size was small and the hypothesis was general and not parameter-specific. As such, further studies are necessary to determine which specific parameter would be most useful and whether or not the results are expandable to clinical modalities. For example, despite the similarity between BV/TV and BMD, COV of BV/TV was more strongly correlated with vertebral strength or stiffness than COV of μCT-BMD. A sample size analysis suggests that the relationship between strength and COV of μCT-BMD is statistically demonstrable at a power of 0.8 and an α of 0.05 using a sample size of 18. If it turns out that imaging methods that can resolve the details of trabecular microstructure are necessary for noninvasive use of the variability information in a clinical environment, alternative imaging techniques could be considered. For example, an analysis of calcaneal cancellous microstructure from X-ray radiograms was able to distinguish fracture cases from controls in a recent study [33]. With the advances in digital X-ray technology, techniques such as tomosynthesis would be able to provide in vivo images that can be used for the type of analyses presented in the current work [34].

The relationships presented here have other implications on the mechanisms of vertebral fracture risk. It is a well accepted notion that bone structurally adapts to local loads by modifying its architecture. There is good evidence that these adaptations result in the maintenance of bone stiffness (thus strength, suggested by the strong correlations between the two [12, 15–19]) in directions of most habitual loading [35, 36]. Homogeneous distribution of microstructural properties could represent an effort to increase stiffness under uniaxial loading. However, over-homogenization of the bone structure could come at a cost of increased brittleness, as suggested by the current data, and result in a clinical fracture even though the bone appears strong on screens. If true, for studies aiming at improving bone mechanical integrity, the outcome measures should include measures of ductility. If the role of microstructural variability in age- and disease-related increase of bone fragility can be further substantiated, cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying heterogeneity of bone microstructure would be of interest.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by Grant Number AR049343 from the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Cranney A, Jamal SA, Tsang JF, Josse RG, Leslie WD. Low Bone Mineral Density and Fracture Burden in Postmenopausal Women. Cmaj. 2007;177(6):575–80. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortoft G, Mosekilde L, Hasling C, Mosekilde L. Estimation of Vertebral Body Strength by Dual Photon Absorptiometry in Elderly Individuals: Comparison between Measurements of Total Vertebral and Vertebral Body Bone Mineral. Bone. 1993;14(4):667–73. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(93)90090-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mcbroom RJ, Hayes WC, Edwards WT, Goldberg RP, White AA., 3rd Prediction of Vertebral Body Compressive Fracture Using Quantitative Computed Tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(8):1206–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mccubbrey DA, Cody DD, Peterson EL, Kuhn JL, Flynn MJ, Goldstein SA. Static and Fatigue Failure Properties of Thoracic and Lumbar Vertebral Bodies and Their Relation to Regional Density. J Biomech. 1995;28(8):891–9. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00155-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudelmaier M, Kollstedt A, Lochmuller EM, Kuhn V, Eckstein F, Link TM. Gender Differences in Trabecular Bone Architecture of the Distal Radius Assessed with Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Implications for Mechanical Competence. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(9):1124–33. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1823-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva MJ, Keaveny TM, Hayes WC. Load Sharing between the Shell and Centrum in the Lumbar Vertebral Body. Spine. 1997;22(2):140–50. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199701150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banse X, Devogelaer JP, Munting E, Delloye C, Cornu O, Grynpas M. Inhomogeneity of Human Vertebral Cancellous Bone: Systematic Density and Structure Patterns inside the Vertebral Body. Bone. 2001;28(5):563–71. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00425-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hulme PA, Boyd SK, Ferguson SJ. Regional Variation in Vertebral Bone Morphology and Its Contribution to Vertebral Fracture Strength. Bone. 2007;41(6):946–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cody DD, Goldstein SA, Flynn MJ, Brown EB. Correlations between Vertebral Regional Bone Mineral Density (Rbmd) and Whole Bone Fracture Load. Spine. 1991;16(2):146–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim DG, Hunt CA, Zauel R, Fyhrie DP, Yeni YN. The Effect of Regional Variations of the Trabecular Bone Properties on the Compressive Strength of Human Vertebral Bodies. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35(11):1907–13. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DG, Christopherson GT, Dong XN, Fyhrie DP, Yeni YN. The Effect of Microcomputed Tomography Scanning and Reconstruction Voxel Size on the Accuracy of Stereological Measurements in Human Cancellous Bone. Bone. 2004;35(6):1375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goulet RW, Goldstein SA, Ciarelli MJ, Kuhn JL, Brown MB, Feldkamp LA. The Relationship between the Structural and Orthogonal Compressive Properties of Trabecular Bone. J Biomech. 1994;27(4):375–89. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laib A, Ruegsegger P. Calibration of Trabecular Bone Structure Measurements of in Vivo Three-Dimensional Peripheral Quantitative Computed Tomography with 28-Microm-Resolution Microcomputed Tomography. Bone. 1999;24(1):35–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Steven GP, Xie YM. On Equivalence between Stress Criterion and Stiffness Criterion in Evolutionary Structural Optimization. Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization. 1999;18(1):67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown TD, Ferguson AB., Jr Mechanical Property Distributions in the Cancellous Bone of the Human Proximal Femur. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51(3):429–37. doi: 10.3109/17453678008990819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keaveny TM, Wachtel EF, Ford CM, Hayes WC. Differences between the Tensile and Compressive Strengths of Bovine Tibial Trabecular Bone Depend on Modulus. J Biomech. 1994;27(9):1137–46. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou FJ, Lang SM, Hoshaw SJ, Reimann DA, Fyhrie DP. Human Vertebral Body Apparent and Hard Tissue Stiffness. J Biomech. 1998;31(11):1009–15. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fyhrie DP, Vashishth D. Bone Stiffness Predicts Strength Similarly for Human Vertebral Cancellous Bone in Compression and for Cortical Bone in Tension. Bone. 2000;26(2):169–73. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(99)00246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yeni YN, Dong XN, Fyhrie DP, Les CM. The Dependence between the Strength and Stiffness of Cancellous and Cortical Bone Tissue for Tension and Compression: Extension of a Unifying Principle. Biomed Mater Eng. 2004;14(3):303–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silva MJ, Gibson LJ. Modeling the Mechanical Behavior of Vertebral Trabecular Bone: Effects of Age-Related Changes in Microstructure. Bone. 1997;21(2):191–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(97)00100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeni YN, Kim DG, Divine GW, Johnson EM, Cody DD. Human Cancellous Bone from T12-L1 Vertebrae Has Unique Microstructural and Trabecular Shear Stress Properties. Bone. 2009;44(1):130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford RP, Cann CE, Keaveny TM. Finite Element Models Predict in Vitro Vertebral Body Compressive Strength Better Than Quantitative Computed Tomography. Bone. 2003;33(4):744–50. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00210-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen W, Niu Y, Mattrey RF, Fournier A, Corbeil J, Kono Y, Stuhmiller JH. Development and Validation of Subject-Specific Finite Element Models for Blunt Trauma Study. J Biomech Eng. 2008;130(2):021022. doi: 10.1115/1.2898723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DG, Dong XN, Cao T, Baker KC, Shaffer RR, Fyhrie DP, Yeni YN. Evaluation of Filler Materials Used for Uniform Load Distribution at Boundaries During Structural Biomechanical Testing of Whole Vertebrae. J Biomech Eng. 2006;128(1):161–5. doi: 10.1115/1.2133770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeni YN, Shaffer RR, Baker KC, Dong XN, Grimm MJ, Les CM, Fyhrie DP. The Effect of Yield Damage on the Viscoelastic Properties of Cortical Bone Tissue as Measured by Dynamic Mechanical Analysis. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82(3):530–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen S, Michael JF. In: Resolving Power of 3d X-Ray Microtomography Systems. Larry EA, et al., editors. Vol. 4682. 2002. pp. 407–413. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samei E, Badano A, Chakraborty D, Compton K, Cornelius C, Corrigan K, Flynn MJ, Hemminger B, Hangiandreou N, Johnson J, Moxley-Stevens DM, Pavlicek W, Roehrig H, Rutz L, Shepard J, Uzenoff RA, Wang J, Willis CE. Assessment of Display Performance for Medical Imaging Systems: Executive Summary of Aapm Tg18 Report. Med Phys. 2005;32(4):1205–25. doi: 10.1118/1.1861159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lorna J, Gibson MFA. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, Solid State Science Series. Cambridge University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazarian A, Stauber M, Zurakowski D, Snyder BD, Muller R. The Interaction of Microstructure and Volume Fraction in Predicting Failure in Cancellous Bone. Bone. 2006;39(6):1196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kelly A, Macmillan NH. Strong Solids. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindsey DP, Kim MJ, Hannibal M, Alamin TF. The Monotonic and Fatigue Properties of Osteoporotic Thoracic Vertebral Bodies. Spine. 2005;30(6):645–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000155411.69149.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lespessailles E, Chappard C, Bonnet N, Benhamou CL. Imaging Techniques for Evaluating Bone Microarchitecture. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(3):254–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chappard C, Brunet-Imbault B, Lemineur G, Giraudeau B, Basillais A, Harba R, Benhamou CL. Anisotropy Changes in Post-Menopausal Osteoporosis: Characterization by a New Index Applied to Trabecular Bone Radiographic Images. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(10):1193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1829-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wolbarst AB, Hendee WR. Evolving and Experimental Technologies in Medical Imaging. Radiology. 2006;238(1):16–39. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2381041602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Homminga J, Van-Rietbergen B, Lochmuller EM, Weinans H, Eckstein F, Huiskes R. The Osteoporotic Vertebral Structure Is Well Adapted to the Loads of Daily Life, but Not to Infrequent “Error” Loads. Bone. 2004;34(3):510–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Der Linden JC, Day JS, Verhaar JA, Weinans H. Altered Tissue Properties Induce Changes in Cancellous Bone Architecture in Aging and Diseases. J Biomech. 2004;37(3):367–74. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]