Abstract

Approximately 10% of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) cases are familial (known as FALS) with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and ~25% of FALS cases are caused by mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1). There is convincing evidence that mutant SOD1 (mtSOD1) kills motor neurons (MNs) because of a gain-of-function toxicity, most likely related to aggregation of mtSOD1. A number of recent reports have suggested that antibodies can be used to treat mtSOD1-induced FALS. To follow up on the use of antibodies as potential therapeutics, we generated single chain fragments of variable region antibodies (scFvs) against SOD1, and then expressed them as ‘intrabodies’ within a motor neuron cell line. In the present study, we describe isolation of human scFvs that interfere with mtSOD1 in vitro aggregation and toxicity. These scFvs may have therapeutic potential in sporadic ALS, as well as FALS, given that sporadic ALS may also involve abnormalities in the SOD1 protein or activity.

Keywords: familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, mutant superoxide dismutase type 1, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, single chain fragments of variable region antibodies, scFvs, motor neuron disease

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the selective loss of motor neurons (MNs). Approximately 10% of ALS cases are familial (known as FALS) with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, and ~25% of FALS cases are caused by mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1)(Rothstein, 2009). There is convincing evidence that mutant SOD1 (mtSOD1) kills motor neurons (MNs) because of a gain-of-function, rather than a loss-of-function (i.e., a loss of dismutase activity). Although the nature of the mtSOD1 toxicity remains unclear, some investigators have postulated a key role played by aggregation of mtSOD1, with an associated sequestration of proteins that are critical for the viability of the MN. Such sequestration of proteins could lead to a variety of other deficits, such as abnormalities in axonal flow and alterations in the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway.

Of interest, recent data suggest that sporadic ALS may also involve abnormalities in the SOD1 protein or activity (Bosco et al., 2010; Ezzi et al., 2007; Guareschi et al., 2012; Kabashi et al., 2007; Pokrishevsky et al., 2012). Therefore, investigations of mtSOD1 may not only clarify our understanding of the pathogenesis and the treatment of FALS, but also increase our understanding and treatment of sporadic ALS.

A number of reports have suggested that antibodies may have a role in the treatment of mtSOD-1-induced FALS. Immunization with mtSOD1 protein (Urushitani et al., 2007) (Takeuchi et al., 2010) or a peptide within the SOD1 interface (Liu et al., 2012) delays disease onset and extends survival of FALS transgenic mice. Furthermore, Alzet osmotic minipump intraventricular infusion of anti-SOD1 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) into FALS transgenic mice delays body weight loss and hind limb reflex impairment and significantly prolongs survival (Gros-Louis et al., 2010; Urushitani et al., 2007). Together, these studies demonstrate that anti-SOD1 antibodies can ameliorate disease in FALS transgenic mice.

In the present study, we describe isolation of single chain fragments of variable regions (scFvs) of antibodies directed against SOD1, focusing on two scFvs that interfere with in vitro aggregation and toxicity of mtSOD1. One of the advantages of scFvs is that they can be readily cloned, expressed, and used in gene delivery studies. Of special interest, scFvs can be expressed within cells, where these “intrabodies” can bind to and perturb their targets (Zu et al., 1997). Intrabodies, therefore, have the potential for disrupting aggregate and oligomer formation, and thereby help clarify FALS pathogenesis and ameliorate disease.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and Biotinylation of SOD1

cDNAs from wild type (wt) SOD1 and three mtSOD1s (A4V, G93A and V148G) were inserted in the prokaryotic expression vector, pMCSG15, which contained His6 and AviTag at the C-terminus (Scholle et al 2004). The plasmids were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) pBirA (Avidity, CO), which expresses biotin ligase, an enzyme capable of in vivo biotinylation. The proteins were induced with isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and biotinylated with the addition of 0.1 mg/L of biotin to the cell culture media. Proteins were isolated and purified using a Ni-NTA affinity column (Qiagen, MD), and then analyzed by Western blot, using rabbit anti-SOD1 polyclonal antibody (Enzo Life Sciences, Inc., NY) and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, MA) or streptavidin-HRP (Chemicon, CA), followed by detection with an ECL-Plus detection kit (Amersham, NJ).

Isolation of phage clones that expressed scFvs that bound SOD1

Affinity selection experiments were performed with the C-terminal biotinylated SOD1s as target proteins and a phage-displayed scFv antibody library (Bliss et al., 2003) a gift from Dr. Mark Sullivan (University of Rochester Medical Center). The biotinylated wtSOD1 protein was immobilized onto streptavidin-coated 96-well microtiter plates; unbound target protein was removed and the plates were washed seven times with 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 % Tween-20, (pH 7.5) buffer (TBST) and blocked with TBST containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Bound target protein was then incubated with the scFv phage; unbound phage was removed, and the plates were washed five times with TBST. Bound phage were eluted with 50 μl of 100 mM glycine-HCl (pH 2.0) buffer and immediately neutralized with 20 μl of 2 M Tris-HCl, (pH 10). The eluted phage particles were amplified by infecting E. coli TG1 bacteria, and the phage were rescued by superinfecting the host with helper phage M13K07 (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). Secreted phage particles were concentrated by precipitation with 6% polyethylene glycol (MW 8000) - 0.3 M NaCl, and subjected to two more rounds of affinity selection, as described above. Exponentially growing TG1 bacterial cells (supE thi-1 Δ(lac-proAB) hsdD5[F′ traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZDM15]) were infected with the eluted phage isolated after the third round of selection at 37°C for 1 h, plated onto petri plates containing 16 g tryptone 10 g yeast extract 5 g NaCl, 1.5% agar, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, and 1% glucose, and incubated overnight at 30°C. Bacterial colonies were grown individually in a 96-well deep-well plate, superinfected with M13K07 helper phage, and the rescued phage particles were then tested for their ability to bind wt or mutant SOD1 by an enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

ELISA

High-binding, flat-bottom microtiter plates were coated with streptavidin (250 ng/well in 50 μl PBS) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The next day, plates were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS; 137 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 8 mM Na2HPO4, 1.5 mM KH2PO4) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), and purified biotinylated wt or each of the three mtSOD1 proteins (250 ng in 50 μl PBS) was added to each well of a separate ELISA plate. The plates were incubated at room temperature (RT) for 1.5 h on a shaker, blocked for 30 min with 2% BSA in PBS, and then washed three times with PBST. Twenty-five μl of PBS and 25 μl of phage particles, grown in the previous step, were added to each well and the plates were shaken at RT for 1.5 h. The plates were washed three times with PBST and the bound phage particles were detected with 50 μl of HRP-linked anti-M13 antibody (Amersham Biosciences) for 1 h at RT on a shaker. Following five PBST washes, 50 μl of HRP substrate solution containing 220 mg/L of 2′,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid, 50 mM sodium citrate (pH4.0), and 0.05% H2O2 was added for 20–30 min, and the developed color was measured at 405 nm. Plates coated with streptavidin, with or without captured biotinylated SOD1, were used as negative controls. A ratio of 2 or more of optical density of a phage binding to SOD1 target over background was generally used as a positive signal to identify individual scFv phage clones. In order to discover binders that bind uniquely to one of the SOD1 variants, binders for each SOD1 target protein were checked for cross-reactivity by ELISA. The DNA inserts of phage clones with the highest ELISA values were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and then sequenced.

Characterization of scFvs by Western blot analysis

Two hundred ng of purified and biotinylated bacterially-expressed wt SOD1, mt (A4V and G93A) SOD1, or human Src SH3 domain (negative control) were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were then incubated with precipitated phage particles for 2 h, washed, and then incubated with an anti-M13 phage antibody conjugated to HRP. Separately, membranes were incubated with polyclonal rabbit anti-SOD1 antibody (Enzo; 1:1000 dilution) and processed with an anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to HRP. Immune complexes on the blots were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Plus detection system (Amersham Biosciences).

scFv eukaryotic expression

The coding regions of strong binding scFvs were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 expression vector, as follows. The coding region of scFv along with the Flag-epitope tag at the amino-terminus was amplified by PCR using primers that added an XbaI restriction site and ATG translational start site at the 5′-end and an XhoI site at the 3′-end of the amplified DNA fragment. The PCR product was digested with XbaI and XhoI, and then cloned into the NheI and XhoI sites of pcDNA3.1. The fidelity of the correct sequence of the recombinant clones was confirmed by sequencing and expression studies.

B1and B12 scFvs that contained a FLAG tag at the N-terminsus and had been separately cloned into pcDNA3.1 were transfected into NSC-34 cells. The cells were harvested after 48 hours, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and then stained with mouse anti-FLAG antibody (Sigman Aldrich, MO) followed by detection with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody.

Effect of anti-SOD1 scFvs on mtSOD1-induced aggregates and cell death

NSC-34 cells in a 12-well plate were cotransfected with an mtSOD1-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) fusion construct and scFv DNAs using the Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen), and fixed 48 h later with 4% paraformaldehyde. The mean percent of aggregate-positive cells was calculated by counting the number of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-expressing cells in 10–15 random fields from two wells in each of two separate experiments that contain aggregates, as determined by epifluorescence microscopy.

To test the effect on cell viability, cells in a 96-well plate were transfected with scFv and either A4V or G93A SOD1 coding regions. Cell viability was analyzed by using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo, Rockville, MD), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The results are presented as percent cell survival compared to the absorbance in the control transfected cells. The results were from six wells in each of two separate experiments.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s Multiple Comparison Test.

Results

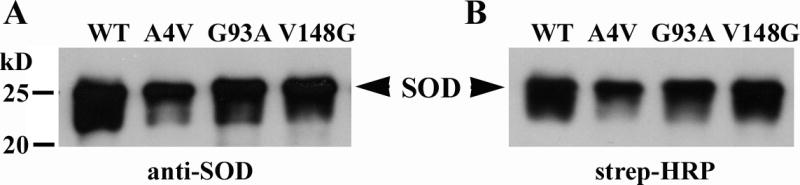

Expression and purification of biotinylated SOD1 in E. coli

The wt and three mtSOD1s (A4V, G93A and V148G) cDNAs were inserted in a prokaryotic expression vector, MCSG15 (Scholle et al., 2005), which contains biotinylation (i.e., AviTag) and His6 tags at the C-terminus of the fusions. These recombinant proteins were overexpressed in E. coli and purified to near homogeneity by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. As the E. coli cells also overexpressed the biotin ligase, BirA, >80% of the purified protein carried a single biotin at its C-termini. Fig. 1 shows the results of a Western blot of bacterially-expressed wt and mtSOD1 proteins that had been subjected to SDS-PAGE and then immunostained with anti-SOD1 antibody or stepavidin-HRP anti-rabbit IgG. The blotted proteins immunostained with both antibodies demonstrating that the SOD1s were biotinylated.

Figure 1.

Bacterially expressed and purified wt and mtSOD1 target proteins, which have been biotinylated at their C-termini. The SOD1 proteins were detected with (A) anti-SOD1 polyclonal antibody, and (B) streptavidin-HRP.

Affinity selection and activity of SOD1-binding phage displaying scFvs

An M13 bacteriophage library (Bliss et al., 2003) displaying human scFvs, was subjected to three rounds of affinity selection with the wt and three mtSOD1 proteins. Many strong binders were found to each target (data not shown). When they were then cross-checked by ELISA against each of the four targets, only one phage clone (B4) was found to bind to three of the four proteins, but not to G93A mtSOD1. We suspect that the epitope for the B4 scFv includes the glycine 93 of SOD, and therefore when it is an alanine (i.e., G93A) it no longer binds.

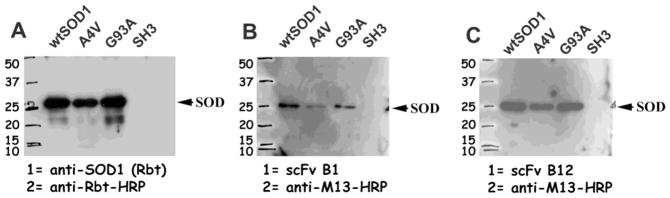

Some of the scFvs were examined for reactivity against SOD1 on Western blots. Figure 2 shows Western blots that tested the reactivity of two scFvs (that were found in subsequent experiments to have activity against mtSOD1 aggregation and toxicity) against denatured wt and mt SOD1. scFv B1 phage particles (Fig. 2B) and scFv B12 phage particles (Fig. 2C) reacted against denatured wt, A4V and G93A SOD1 proteins but not the control SH3 protein.

Figure 2.

Characterization of scFv phage clones using Western blot analysis. wt or mt (A4V and G93A) biotinylated SOD1 proteins as well as human Src SH3 domain (negative control) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, which were then incubated with rabbit anti-SOD1 antibody (A), B1 phage particles (B), or B12 phage particles (C). Blots were developed using either HRP-linked anti-rabbit antibody or HRP-linked anti-M13 antibody, followed by detection using ECL-Plus kit.

To identify the scFvs that were unique, and not sibling clones, the coding regions of strong binders were cleaved with BstNI restriction enzyme (New England BioLabs). Clones with unique fragmentation patterns were chosen for DNA sequencing and then inserted into pcDNA3.1.

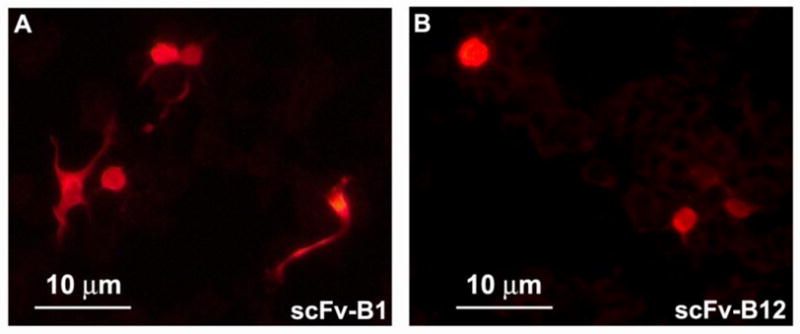

Expression and activity of scFvs

In order to begin to characterize the expression and solubility of the scFvs, we separately transfected NSC-34 cells with B1scFv and B12 scFv that contained a FLAG tag at the N-terminus and had been cloned into pcDNA3.1. Fig. 3 shows NSC-34 cells that had been transfected with B1 and B12 scFvs and then fixed, and overlaid with anti-FLAG antibody followed by detection with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. In each case, diffuse cytoplasmic staining of the scFvs was seen. A pcDNA3.1 vector control that contained a FLAG tag showed no staining (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Subcellular localization of B1 and B12 scFvs in NSC-34 cells. NSC-34 cells were separately transfected with B1 (A) and B12 (B) scFv that contained a FLAG tag. The cells were harvested 48 hours later and stained with mouse anti-FLAG antibody followed by detection with Alexa Fluor 555-conjugated anti-mouse antibody. In each case, diffuse cytoplasmic staining with no aggregation of the scFvs was seen.

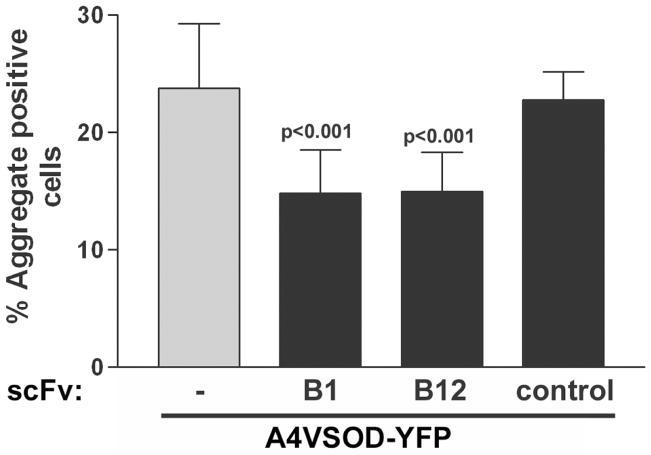

We then tested the B1 and B12 scFv pcDNA3.1 clones with respect to their ability to decrease A4V mtSOD1 aggregation. We chose A4V mtSOD1 for these studies since aggregation is prominently seen after expression of this mtSOD1. NSC-34 cells were cotransfected with A4VSOD1-YFP along with the scFv coding regions. Some cells had homogeneously YFP-stained cytoplasm, while other cells had one or more YFP fluorescent foci that were scored as aggregates. The percentage of YFP-expressing cells that contained aggregates was determined 48 h after transfection (Figure 4). Approximately 24% of YFP-expressing cells had bright focal punctuate areas of fluorescence following transfection with A4VSOD1-YFP without an scFv. The number of aggregates was not significantly affected by cotransfection of A4VSOD1-YFP with a control scFv cDNA. However, there was a statistically significant decrease in A4VSOD1-YFP aggregation (P < 0.001) following cotransfection of B1 or B12 scFv. The mean results from testing B1 and B12 scFvs in two separate experiments that each involved 10–15 fields from two wells of each scFv are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Effect of anti-SOD1 B1 and B12 scFvs on A4VSOD1-YFP induced aggregation. NSC-34 cells were transfected with A4VSOD1-YFP with or without an scFv expression construct. The number of aggregate-positive cells was counted 48 h later (from 10–15 random fields). “−” corresponds to cotransfection of A4VSOD1-YFP with pcDNA3.1 (an empty vector). “control” corresponds to cotransfection of A4VSOD1-YFP along with an scFv expression construct without anti-SOD1 activity.

We next tested whether the scFvs interfere with cell death caused by A4V and G93A mtSOD1s. NSC-34 cells were cotransfected with A4V or G93A with or without scFvs. The percent survival was calculated 48 h later using a colorimetric assay. Figure 5 shows the results for each scFv from two separate experiments that each involved calculating the mean colorimetric absorbance from 6 wells for each experiment. Both A4V and G93A led to significant cell death when compared to mock-transfected cells. Clones B1 and B12 significantly improved cell survival following expression of either A4V or G93A (P < 0.001). In contrast, empty vector and a negative control scFv had no significant effect on cell survival.

Figure 5.

Effect of anti-SOD1 B1 and B12 scFvs on A4V-YFP and G93A-YFP induced cell death. NSC-34 cells were transfected with A4V or G93A with or without scFvs, and the percent survival was calculated 48h later from 10–15 random fields. “−” corresponds to cotransfection of A4V or G93A along with pcDNA3.1 (empty vector). “control” corresponds to cotransfection with a construct expressing an scFv without anti-SOD1 activity along with A4V-YFP.

Discussion

ALS is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the selective loss of MNs. Approximately 10% of cases are inherited, and mtSOD1 causes ~20% of these cases recognized to date. There is convincing evidence that mtSOD1 does not cause FALS because of a decrease in dismutase activity: some mtSOD1s that induce FALS have full dismutase activity; an SOD−/− mouse does not develop ALS; mice that carry mtSOD1 as a transgene develop ALS, despite a normal endogenous dismutase activity (Rothstein, 2009). Investigators have stressed the potential importance of mtSOD1 aggregation as central to the protein’s toxicity; however, the basis for this toxicity remains unclear, as does effective treatment for this devastating and fatal disease. The importance of misfolded mutant proteins in inducing disease has been proposed in a number of neurodegenerative disease processes (Soto and Estrada, 2008).

Of interest to the present study is the recent demonstration that vaccination with mtSOD1 or an SOD1 peptide or the intraventricular delivery of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against SOD1 leads to amelioration of disease in FALS transgenic mice (Gros-Louis et al., 2010; Urushitani et al., 2007) (Takeuchi et al., 2010). There are a number of mechanisms by which mAbs (and scFvs) could be protective in prolonging survival of FALS transgenic mice: the antibodies may interfere with aggregation (assuming that the oligomeric or high molecular weight forms of mtSOD1 are pathogenic), thereby preventing the sequestration of proteins that are important for MN survival; the antibodies may cover up a toxic domain of mtSOD1 that is exposed when SOD1 is misfolded; the antibodies may change the conformation of misfolded mtSOD1, thereby attenuating the mutant’s toxicity; the antibodies may down-regulate expression of mtSOD1.

One of the potential advantages of scFvs over mAbs as a treatment of FALS is the fact that their small size makes them amenable to intracellular delivery and activity. It may be valuable in the future to employ both an intracellular as well as extracellular delivery of anti-SOD1 antibody in treating FALS, perhaps by making use of both an scFv as well as a mAb. Intracellular scFv and extracellular mAb treatment may be important not only for mtSOD1-induced FALS, but also in the treatment of sporadic ALS, since recent data suggest that the sporadic disease may involve abnormalities of SOD1 (Bosco et al., 2010; Ezzi et al., 2007; Grad et al., 2011; Guareschi et al., 2012; Kabashi et al., 2007; Pokrishevsky et al., 2012).

scFvs have been generated against a number of misfolded proteins that have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, with the goal of using them for treatment. For example, scFvs have been generated against alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease (Maguire-Zeiss et al., 2006) (Emadi et al., 2004) (Lynch et al., 2008; Yuan and Sierks, 2009), huntingtin in Huntington’s disease (reviewed in (Butler et al., 2012)), amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease (reviewed in (Robert and Wark, 2012)), and prion protein in prion diseases (reviewed in (Sakaguchi et al., 2009)).

In the present study, we isolated a number of scFvs directed against SOD1 by affinity selection using phage display libraries. Of interest was the isolation of two scFvs that decrease the aggregation and toxicity of mtSOD1s. These scFvs are reactive against wt as well as mtSOD1 by ELISA. The reactivity of the scFvs against wtSOD1 may not be a problem with respect to treatment of patients since mice with wtSOD1 knock-out had a relatively minor phenotype (Harris et al., 2007).

A potential problem with respect to scFvs is that the antibodies can be unstable and aggregation-prone due to the reducing environment and macromolecular crowding of the cytoplasm. Recent studies have shown that the proper folding and solubility of scFvs can be significantly affected by its complementary determining region content, with enhanced solubility of the scFv as a result of an overall negative charge at cytoplasmic pH and reduced hydrophilicity (Kvam et al., 2010). Using methods described by Kvam et al. (Kvam et al., 2010) we calculated the isoectric point, net charge at cytoplasmic pH, and grand average of hydrophobicity (GRAVY) for tagged and untagged B1 and B12 scFvs (Table). The values that we obtained for the tagged scFvswere ones that have been associated with favorable and soluble expression in the cytoplasm (Kvam et al., 2010). The values for untagged B1 and B12 scFvs predict problems with the solubility and folding of these scFvs, which is a concern since clinical use may require the scFvs to be untagged; however, the predictions from these kinds of data may not always be accurate. In addition, there may be ways of engineering the scFvs that enhance the solubility of the untagged antibodies.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical properties of B1 and B12 scFvs

| scFv | pIa | Net charge at pH 7.4 | GRAVYb |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1-FLAG | 5.69 | −2.6 | −0.348 |

| B1 | 7.61 | 0.4 | −0.271 |

| B12-FLAG | 5.69 | −2.4 | −0.255 |

| B12 | 7.75 | 0.6 | −0.172 |

pI = isolelectric point;

GRAVY = grand average of hydrophobicity

Our future plan is to test these scFvs in mtSOD1 FALS transgenic mice. The scFvs could be delivered intracellularly with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector. A recent report demonstrated that intravenous inoculation of neonatal mice with an AAV9 vector leads to persistent expression of a transgene in neurons (including the MNs of the spinal cord), while inoculation of old mice leads to persistent expression primarily in astrocytes (Foust et al., 2009). Remarkably, these studies showed that ~60% of MNs in the spinal cord (as well as some astrocytes and microglia) expressed the transgene 21 days (the latest time checked) after intravenous inoculation of a neonate, while intravenous inoculation of 75 day-old mice led to expression of >64% of astrocytes in the spinal cord segment with persistent expression for at least 7 weeks (the latest time checked). These observations have been confirmed by a number of other labs with respect to gene delivery in rodents as well as non-human primates (reviewed in (Dayton et al., 2012). Having both neuronal and astrocytic delivery may be advantageous since we and others have demonstrated that there is non-cell autonomous degeneration in mtSOD1-induced ALS, in which non-neuronal cells play a significant role in the MN degeneration.

Highlights.

We screened a phage display library to identify scFvs that bind wild type and/or mutant SOD1

We isolated scFvs that bind wild type and mutant SOD1.

Two of the scFvs interfere with aggregation and toxicity of mtSOD1 in a motor neuron cell line.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21 NS066175 to RPR) and the ALS Association (#910 to RPR). The technical assistance of Anna Liza Monti and Sevde Felek is gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- FALS

familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MN

motor neuron

- mt

mutant

- scFv

single-chain fragments of variable regions

- SOD1

superoxide dismutase type 1

- wt

wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bliss JM, et al. Differentiation of Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis by using recombinant human antibody single-chain variable fragments specific for hyphae. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1152–60. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1152-1160.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosco DA, et al. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1396–403. doi: 10.1038/nn.2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler DC, et al. Engineered antibody therapies to counteract mutant huntingtin and related toxic intracellular proteins. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;97:190–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton RD, et al. The advent of AAV9 expands applications for brain and spinal cord gene delivery. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:757–66. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.681463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzi SA, et al. Wild-type superoxide dismutase acquires binding and toxic properties of ALS-linked mutant forms through oxidation. J Neurochem. 2007;102:170–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04531.x. Epub 2007 Mar 29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, et al. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. Epub 2008 Dec 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad LI, et al. Intermolecular transmission of superoxide dismutase 1 misfolding in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16398–403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros-Louis F, et al. Intracerebroventricular infusion of monoclonal antibody or its derived Fab fragment against misfolded forms of SOD1 mutant delays mortality in a mouse model of ALS. J Neurochem. 2010;113:1188–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guareschi S, et al. An over-oxidized form of superoxide dismutase found in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with bulbar onset shares a toxic mechanism with mutant SOD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5074–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115402109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris J, et al. Fabrication of a microfluidic device for the compartmentalization of neuron soma and axons. J Vis Exp. 2007:261. doi: 10.3791/261. Epub 2007 Aug 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi E, et al. Oxidized/misfolded superoxide dismutase-1: the cause of all amyotrophic lateral sclerosis? Ann Neurol. 2007;62:553–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam E, et al. Physico-chemical determinants of soluble intrabody expression in mammalian cell cytoplasm. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2010;23:489–98. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HN, et al. Targeting of Monomer/Misfolded SOD1 as a Therapeutic Strategy for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8791–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5053-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch SM, et al. An scFv intrabody against the nonamyloid component of alpha-synuclein reduces intracellular aggregation and toxicity. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:136–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.11.096. Epub 2007 Dec 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire-Zeiss KA, et al. Identification of human alpha-synuclein specific single chain antibodies. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:1198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.08.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokrishevsky E, et al. Aberrant localization of FUS and TDP43 is associated with misfolding of SOD1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert R, Wark KL. Engineered antibody approaches for Alzheimer’s disease immunotherapy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD. Current hypotheses for the underlying biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:S3–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S, et al. Antibody-based immunotherapeutic attempts in experimental animal models of prion diseases. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:907–17. doi: 10.1517/13543770902988530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholle MD, et al. Efficient construction of a large collection of phage-displayed combinatorial peptide libraries. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2005;8:545–51. doi: 10.2174/1386207054867337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Estrada LD. Protein misfolding and neurodegeneration. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:184–9. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi S, et al. Induction of protective immunity by vaccination with wild-type apo superoxide dismutase 1 in mutant SOD1 transgenic mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:1044–56. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181f4a90a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushitani M, et al. Therapeutic effects of immunization with mutant superoxide dismutase in mice models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2495–500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606201104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan B, Sierks MR. Intracellular targeting and clearance of oligomeric alpha-synuclein alleviates toxicity in mammalian cells. Neurosci Lett. 2009;459:16–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zu JS, et al. Exon 5 encoded domain is not required for the toxic function of mutant SOD1 but essential for the dismutase activity: identification and characterization of two new SOD1 mutations associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurogenetics. 1997;1:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s100480050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]