Abstract

The vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) is considered as a new target for the development of novel therapeutics to treat psychostimulant abuse. Current information on the structure, function and role of VMAT2 in psychostimulant abuse are presented. Lobeline, the major alkaloidal constituent of Lobelia inflata, interacts with nicotinic receptors and with VMAT2. Numerous studies have shown that lobeline inhibits both the neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine in rodents, and behavioral studies demonstrate that lobeline has potential as a pharmacotherapy for psychostimulant abuse. Systematic structural modification of the lobeline molecule is described with the aim of improving selectivity and affinity for VMAT2 over neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and other neurotransmitter transporters. This has led to the discovery of more potent and selective ligands for VMAT2. In addition, a computational neural network analysis of the affinity of these lobeline analogs for VMAT2 has been carried out, which provides computational models that have predictive value in the rational design of VMAT2 ligands and is also useful in identifying drug candidates from virtual libraries for subsequent synthesis and evaluation.

Keywords: Vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2), psychostimulant abuse, lobeline, lobeline analogs, computational modeling

1. VMAT2

1.1. Introduction

The accumulation and storage of the monoamines serotonin, dopamine (DA), norepinephrine, and histamine in the vesicles of neurons is essential to the regulatory processes governing available cytosolic concentrations of these endogenous neurotransmitters [1]. The vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) exists as two distinct isoforms VMAT1 and VMAT2 [2–5]. VMAT2 is expressed in sympathetic postganglionic neurons as well as adult human and monoaminergic neurons of the central nervous system, whereas VMAT1 is primarily expressed in neuroendocrine cells including chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and enterochromaffin cells of the intestine [1, 6–10]. However, recent studies have shown that VMAT1 is also expressed in brain [11]. Both isoforms of VMAT are expressed during the embryonic growth and development phase in mammals [12]. Studies utilizing transfected Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing either VMAT1 or VMAT2 revealed differences in both substrate recognition and activity of inhibitors. For example, VMAT2 has greater affinity for the monoamines, and greater sensitivity to inhibition by tetrabenazine (TBZ) compared to VMAT1 [1, 4].

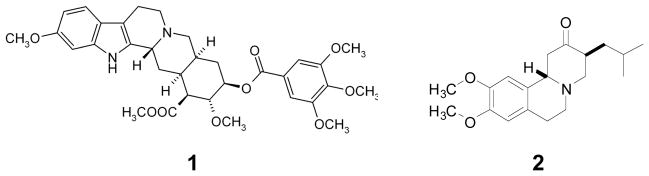

The natural alkaloid reserpine 1, Fig. (1) and the synthetic compound TBZ 2, Fig. (1) are both considered classical inhibitors of VMAT2 [13]. Reserpine inhibits monoamine transport into synaptic storage vesicles as well as chromaffin granules by interaction with VMAT [14, 15]. Reserpine binds to the amine recognition site on VMAT2 and TBZ binds to an allosteric site on this protein that is distinct from the substrate binding site [15–17].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of reserpine (1) and tetrabenazine (2).

1.2. The Role of VMAT2 in Psychostimulant Abuse

The psychostimulant amphetamine and other structurally-related compounds, including methamphetamine, interact with VMAT2 and the DA transporter (DAT) to increase synaptic DA concentrations leading to reward and drug-seeking behavior [18–23]. These psychostimulants inhibit DA uptake into and promote DA release from the synaptic vesicles via its interaction with VMAT2 [24, 25]. Amphetamine enters the vesicle by diffusing across the vesicular membrane or by uptake via VMAT2 with a resulting decrease in pH gradient across the vesicular membrane and a reduction in the free energy available for DA transport into the vesicle [24–27]. Amphetamine accumulating inside the vesicle also competes with monoamine neurotransmitters for available protons, as monoamines are normally found as cationic at the low pH found in the vesicle, but the increase in pH due to the influx of amphetamine results in monoamines reverting to their non-ionized form, resulting in diffusion of neutral mono-amines out of the vesicle [27]. Studies utilizing VMAT2 knockout mice demonstrate reduced drug-seeking behavior compared to wild-type in locomotor response studies that included a array of drugs, including amphetamine and cocaine.[28, 29]. Collectively, these results support the validity of VMAT2 serving as a target for the development of therapeutic agents that have the ability to augment cessation of psychostimulant abuse [30].

1.3. VMAT2 Structure

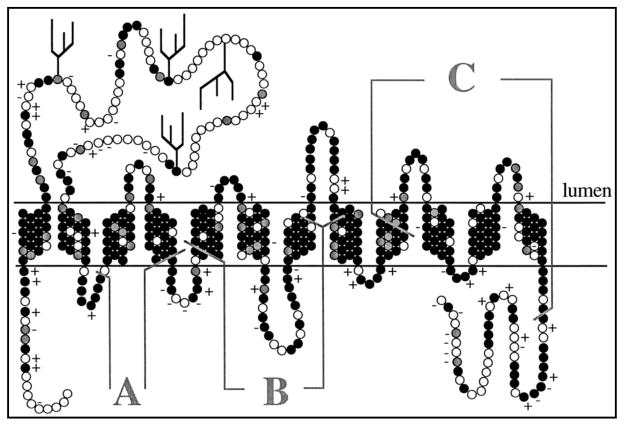

VMAT2 is a member of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) of transporters [36]. The computationally predicted molecular structure of VMAT2 is thought to incorporate 12 putative transmembrane domains (TMDs) Fig. (2) based on hydrophobicity plots of the amino acid sequence of the protein [31]. Both the N- and C- termini are cytosolic, and a hydrophobic, N-glycosylated loop is believed to be located between TMDs 1 and 2 Fig. (2) left, projecting into the vesicle lumen. [32].

Fig. 2.

VMAT2 Predicted Secondary Structure (Copyright permission requested, need to login to JBC, create account, costs $86.25. NEED COPYRIGHT AUTHORIZATION) Peter, D. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 1996; 271: 2979–2986

Structural biology studies have identified specific amino acid residues in the VMAT2 protein that are likely important sites for ligand binding and monoamine transport. Mutagenesis experiments indicate that the negatively charged aspartate 33 residue in TMD1 and serine residues 180 and 183 in TMD3 of VMAT2 are essential for substrate recognition. Substrate-recognition is believed to result interaction of the protonated amino group of the substrate with aspartate 33 and interaction of the catechol or indole hydroxyl groups with serine residues 180 and 183 [32]. Further, lysine 139 in TMD2 and aspartate 427 in TMD11 of VMAT2 form an ion-pair and provide a structural foundation for high affinity substrate recognition [33]. Experiments utilizing chimeras of VMAT1 and VMAT2 show that two regions of the protein, incoporating TMD5 through TMD8 Region B, Fig. (2), and TMD9 through TMD12 Region C, Fig. (2), liaise to confer TBZ and histamine with high affinity at VMAT2. Similar experiments reveal that the region that includes TMD3 and TMD4 Region A, Fig. (2) confers serotonin affinity, but does not impart affinity for histamine or sensitivity to TBZ [30]. Studies employing photoaffinity labelling of purified VMAT2 from rat brain suggest that TMD1 and TMD10/TMD11 may be adjacent to one another, and likely interact and thereby affecting function [34]. Cysteine mutagenesis and deriviatization experiments with human VMAT2 (hVMAT2) have demonstrated that cysteine residues 439, 476, and/or 497, and possibly cysteine 126 and/or 333, are critical for [3H]TBZ binding. Moreover, modification of a combination of three or more of the cysteine residues 126, 333, 439, 476, and 497 alters [3H]TBZ binding characteristics [35]. Furthermore, preincubation with [3H]TBZ, even at low concentrations, effectively blocked subsequent modification at cysteine 439 in TMD 11, suggesting that cysteine 439 is positioned at the TBZ binding site on VMAT2. Several studies provide support for location of the TBZ binding site on VMAT2 at TMD 11, as well as suggest contributions from TMDs 1, 2 and 12 [36]. More recently, comparative modeling studies were conducted utilizing high resolution structures of proteins from the MFS. These studies predict tertiary structures of the rVMAT2 protein allowing for high structural conservation of the MFS proteins, despite low rates of sequence homology. These models also lend further credence to the idea that TMD 2 and 11 are likely involved in the TBZ binding site, and this hypothesis is further supported by recent mutagenesis studies using functionally expressed rVMAT2 in S. cerevisiae cells [37].

2. LOBELINE

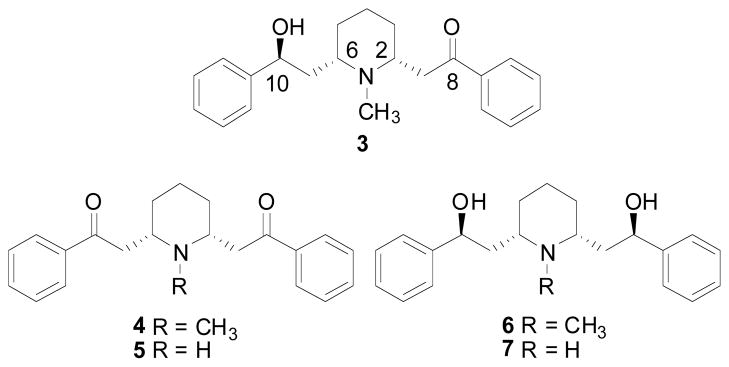

(−)-Lobeline lobeline, 2R,6S,10S-lobeline, 3, Fig. (3) is the major alkaloidal constituent of Lobelia inflata, which is also known as Indian tobacco. The name “Indian tobacco” most likely originated from the fact that Native Americans smoked the dried leaves of the plants (Millspaugh 1974). In 1838, Proctor prepared a liquid alkaloid extract of the plant and named it lobeline (Millspaugh 1974). Historically, the alkaloidal extract of L. inflata has been used as an expectorant, emetic, anti-asthmatic, anti-spasmodic, respiratory stimulant, general muscular relaxant, diaphoretic, diuretic, and stimulant and has been used to treat narcotic overdose. In the plant, lobeline is both the most abundant and the most pharmacologically active constituent of more than 20 structurally-related piperidine alkaloids, which include lobelanine (4), nor-lobelanine (5), lobelanidine (6), and nor-lobelanidine (7) Fig. (3) (Felpin and Lebreton 2004). Lobeline was initially isolated (Wieland 1921) and characterized (Wieland, Schopf et al. 1925; Wieland and Dragendorff 1929) by Wieland, who subsequently reported a total synthesis to confirm its structure (Wieland and Drishaus 1929; Wieland, Koschara et al. 1929). Numerous total syntheses of lobeline have been reported either by the racemic approach (Scheuing and Winterhalder 1929; Schopf and Lehmann 1935) or by the asymmetric approach (Schoepf and Mueller 1965; Compere, Marazano et al. 1999; Felpin and Lebreton 2002; Klingler and Sobotta 2006; Birman, Jiang et al. 2007).

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of lobeline and other structurally-related alkaloids in L. inflata.

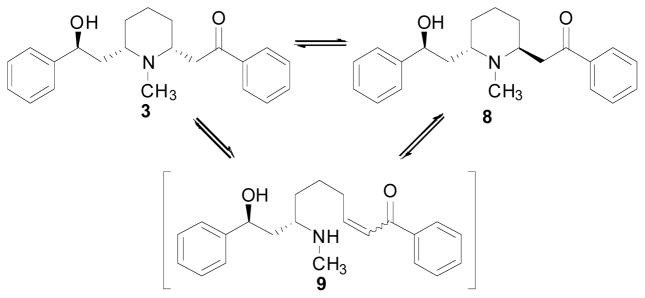

Both the free base and the hydrochloride and sulfate salt forms of lobeline are stable when in crystalline form. However, in solution, due to the presence of the β-aminoketone moiety in the molecule, lobeline readily undergoes a pH-dependent epimerization at C2 of the piperidine ring to yield a mixture of cis-lobeline (3) and trans-lobeline 8, Fig. (4) (Compere, Marazano et al. 1999; Felpin and Lebreton 2002; Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2004). The epimerization is believed to occur via the transient retro-aza Michael addition product 9 Fig. (4). β-Aminoketone compounds often exhibit stability problems, such as epimerization and elimination, due to their susceptibility to retro-aza Michael addition. Retro-aza Michael addition often occurs under acidic conditions (Vazquez, Galindo et al. 2001; Davis, Zhang et al. 2005); however, epimerization does not occur in aqueous solutions of lobeline at pH 3.0. Thus, the epimerization process can be terminated by decreasing the pH of the aqueous media to below 3.0, and this ‘quench’ technique has been used to determine the time course and kinetics of lobeline epimerization under a variety of conditions utilizing HPLC as an analytical methodology for determining epimer ratio (unpublished data). At room temperature, epimerization of lobeline is curtailed when the cis: trans ratio is ~65:35 in aqueous solutions. In a chloroform solution, epimerization stops when a cis:trans ratio of 46:54 is reached (unpublished data). Interestingly, the cis:trans lobeline ratio in human plasma after sublingual administration of lobeline sulfate is about 1:19. Surprisingly, this ratio is reversed to 16:1 cis:trans lobeline, in rat plasma after sublingual administration of lobeline sulfate (Crooks et al., unpublished work).

Fig. 4.

Lobeline epimerization.

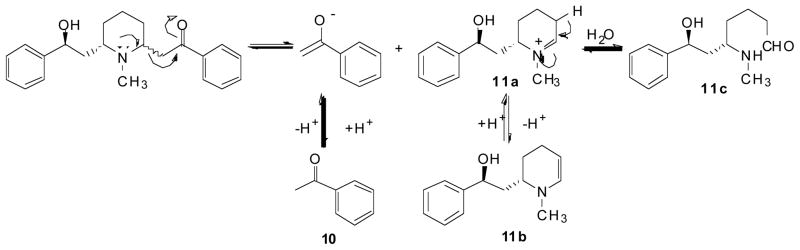

Due to the presence of the β-aminoketone moiety, an additional stability problem associated with lobeline is decomposition via a retro-Mannich reaction which affords ace-tophenone (10) and reactive intermediates 11a, 11b, and 11c Fig. (5) in an aqueous solution (Crooks et al, 2010). As illustrated in Fig. (5), the nitrogen lone pair must be available for the retro-Mannich reaction to occur, which is consistent with experimental observations, demonstrating that this degradation pathway does not occur in acidic media.

Fig. 5.

Retro-Mannich reaction of lobeline.

2.1. Lobeline Pharmacology

The pharmacology of lobeline has been reviewed previously (McCurdy, Miller et al. 2000; Dwoskin and Crooks 2002; Felpin and Lebreton 2004; Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2006). Lobeline exhibits high affinity for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Court, Perry et al. 1994; Damaj, Patrick et al. 1997; Flammia, Dukat et al. 1999; Miller, Crooks et al. 2004), and has many nicotine-like effects, such as tachycardia and hypertension (Korczyn, Bruderma.I et al. 1969), nausea (Bevan and Hughes 1966), anxiolytic activity (Brioni, Oneill et al. 1993), improvement in learning and memory (Decker, Majchrzak et al. 1993), hyperalgesia (Hamann and Martin 1994), and analgesia after intrathecal administration (Damaj, Patrick et al. 1997). Consequently, lobeline has been categorized as a nicotinic receptor agonist. However, lobeline has no obvious structural resemblance to nicotine, and structure-activity relationships (SARs) do not suggest a common pharmacophore (Barlow and Johnson 1989). Further, lobeline and nicotine have different effects in both behavioral and neurochemical studies, suggesting that they do not act via a common mechanism (Dwoskin and Crooks 2002). Specifically, in contrast to nicotine, lobeline only marginally supports self-administration in mice (Rasmussen and Swedberg 1998) and does not support self-administration in rats (Harrod, Dwoskin et al. 2003). In contrast to nicotine, lobeline does not produce conditioned place preference. Also, chronic lobeline treatment does not increase locomotor activity in rats (Fudala and Iwamoto 1986; Stolerman, Garcha et al. 1995). Conversely, lobeline attenuates the hyperactivity induced by repeated nicotine administration in rats (Miller, Harrod et al. 2003). Furthermore, lobeline inhibits nicotine-evoked [3H]dopamine (DA) overflow from rat striatal slices (IC50 ~1 μM), suggesting that the alkaloid acts as an antagonist at nAChRs mediating nicotine-evoked DA release (Miller, Crooks et al. 2000). Lobeline binds to α4β2* nAChRs with high affinity (Ki = 4 nM), and also inhibits nicotine-evoked 86Rb+ efflux from rat thalamic synaptosomes (IC50 = 0.7 μM), indicating that lobeline is an antagonist at α4β2* nAChRs (Miller, Crooks et al. 2000). Additionally, lobeline has also been reported to be an antagonist (IC50 = 8.5 μM) at human α7* nAChRs expressed in Xenopus oocytes (Briggs and McKenna 1998). These results suggest that lobeline acts as a potent, but nonselective, nAChR antagonist.

In addition to the interaction of lobeline with nAChRs, lobeline interacts with VMAT2 and DAT. Lobeline inhibits [3H]dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ) binding to VMAT2 (IC50 = 0.90 μM) and inhibits [3H]DA uptake into rat striatal vesicle preparations (IC50 = 0.88 μM) (Teng, Crooks et al. 1997; Teng, Crooks et al. 1998). In addition, lobeline inhibits [3H]DA uptake into rat striatal synaptosomes (IC50 = 80 μM) via DAT, but with 100-fold lower affinity compared to its inhibition of VMAT2 (Teng, Crooks et al. 1997). In a VMAT2 and DAT co-expressed cell system, lobeline has been shown to evoke [3H]DA release through an interaction with VMAT2, but not with DAT (Wilhelm, Johnson et al. 2004), which was accompanied by a decrease in methamphetamine-evoked [3H]DA release (Wilhelm, Johnson et al. 2008).

Numerous studies have shown that lobeline inhibits both the neurochemical and behavioral effects of amphetamine in rodents. Lobeline inhibits amphetamine-evoked DA release from superfused rat striatal slices (Miller, Crooks et al. 2001) and decreases amphetamine- and methamphetamine-induced hyperactivity in rats and mice (Miller, Crooks et al. 2001), and decreases methamphetamine self-administration in rats without acting as a substitute reinforcer (Harrod, Dwoskin et al. 2001; Harrod, Dwoskin et al. 2003). Pre-treatment with lobeline attenuates the intensity of methamphetamine-induced stereotypy in adolescent mice (Tatsuta, Kitanaka et al. 2006). Lobeline also attenuates cocaine self-administration in rats. The effects of lobeline on cocaine-induced hyperactivity in rats is complex. Acutely, lobeline did not decrease the effect of cocaine on hyperactivity. However, repeated administration of lobeline attenuated cocaine-induced hyperactivity and prevented the development of sensitization to cocaine. Interestingly, repeated administration of a lower dose of lobeline (0.3 mg/kg) increased cocaine (10 mg/kg)-induced hyperactivity (Polston, Cunningham et al. 2006). These behavioral studies demonstrate that lobeline has potential as a pharmacotherapy for psychostimulant abuse. In addition, since lobeline attenuates methamphetamine-induced decreases in rat striatal VMAT2 protein, this suggests a possible neuroprotective role against methamphetamine toxicity (Eyerman and Yamamoto 2005). Lobeline is currently undergoing Phase 2 clinical evaluation to determine its effectiveness in humans as a therapeutic agent for methamphetamine abuse.

Lobeline has recently been shown to interact with opiate receptors, and has been suggested as a potential therapeutic for treatment of opiate abuse [77].

3. LOBELINE INTERACTION WITH VMAT2

Lobeline is believed to inhibit the rewarding effects of psychostimulants by altering synaptic DA concentration via interactions with VMAT2 and DAT [30]. Since the affinity of lobeline at VMAT2 is 100-fold higher than at DAT and lobeline inhibits amphetamine evoked DA release in the concentration range which inhibits VMAT2, but not DAT,it has been proposed that the interaction of lobeline with VMAT2 is the primary mechanism responsible for lobeline-induced inhibition of the behavioral effects of psychostimulants. Thus, VMAT2 is currently being investigated as a novel target for the development of pharmacotherapies to treat psychostimulant addiction (Dwoskin and Crooks 2002). In this respect, a mechanism of action for lobeline has been proposed, i.e. lobeline interacts with the TBZ binding site on VMAT2 to inhibit dopamine uptake and promote dopamine release from storage vesicles within dopaminergic presynaptic terminals(Dwoskin and Crooks 2002).

4. STRUCTURAL MODIFICATION OF LOBELINE

Lobeline represents a novel structural entity as a VMAT2 ligand even though it is a molecule that interacts with multiple receptors and transporters. Systematic structural modification of lobeline has been carried out with the aim of improving selectivity and affinity for VMAT2 over other neurotransmitter transporters and nAChRs.

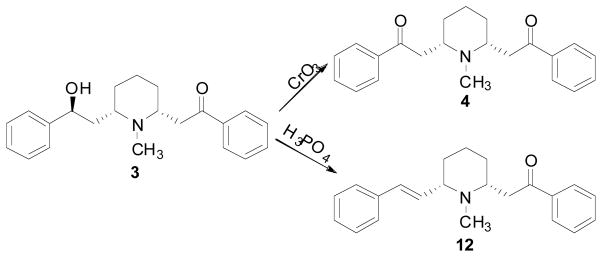

4.1. Modification on the 10-Hydroxyl Group of Lobeline

Jones oxidation (Wieland, Koschara et al. 1929) and acid-catalyzed dehydration (Ebnother 1958; Flammia, Dukat et al. 1999) of lobeline afforded lobelanine (4) and ketoalkene (12), respectively (Scheme 1). Compared to lobeline, both compounds 4 and 12 exhibited a robust 110-9280-fold reduction in affinity for the [3H]nicotine ([3H]NIC) binding site, probing α4β2* nAChRs, a slight reduction in affinity for the [3H]methyllycaconitine ([3H]MLA) binding site, probing α7* nAChRs, and a slight increase in affinity for the [3H]methoxytetrabenazine ([3H]MTBZ) binding site, probing VMAT2 (Table 1) (Miller, Crooks et al. 2004). These results demonstrate that the 10-hydroxyl group is important for α4β2* nAChRs interaction, but not for α7* nAChR nor VMAT2 interaction.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of lobelanine and ketoalkene.

Table 1.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of Compounds 3, 4, 6, and 12.

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC Binding α4β2* nAChRa | [3H]MLA Binding α7* nAChRa | [3H]MTBZ Binding VMAT2a | |

| 3 | 0.004 | 11.6 | 5.46 |

| 4 | 37.1 | 22.7 | 2.41 |

| 6 | 3.10 | 3.29 | 25.9 |

| 12 | 0.44 | 34.2 | 1.35 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

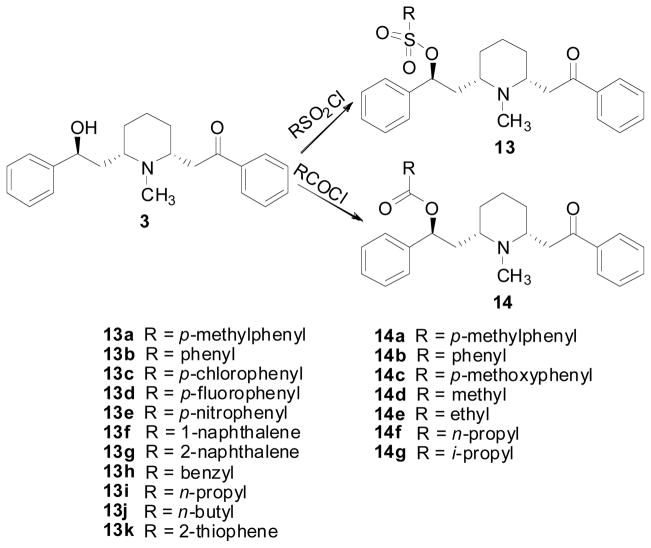

Acylation or sulfonation of the 10-hydroxyl group of lobeline provided a series of lobeline carboxylic and sulfonic esters which exhibited interesting biological activity (Scheme 2). All the lobeline sulfonate derivatives (13a–k), including both aliphatic and aromatic sulfonates, exhibited similar binding profiles to lobeline at α4β2*, α7* nAChRs and VMAT2 (Table 2). However, within the lobeline ester series, aromatic esters (14a–c) exhibited 400–4830-fold lower affinity for α4β2* nAChRs compared to lobeline, while the aliphatic esters 14d–g exhibited only 15–125-fold lower affinity for α4β2* nAChRs (Table 2). In addition, all the carboxylic esters (14a–g) were equipotent to lobeline at VMAT2 (Table 2) [85]. Compounds 13a–13k and 14a–14g generally exhibited poor affinity for α7 nAChRs. Thus, esterification of the lobeline molecule with sulphonic acids affords analogs with high affinity for α4β2 nAChRs and comparable affinity to lobeline at VMAT2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of lobeline esters and sulfonates.

Table 2.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of Lobeline Carboxylic and Sulfonic Esters.

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC Binding α4β2* nAChRsa | [3H]MLA Binding α7* nAChRsa | [3H]DTBZ Binding VMAT2a | |

| 3 | 0.004 ± 0.0001 | 6.26 ± 1.30 | 2.76 ± 0.64 |

| 13a | 0.005 ± 0.001 | 18.0 ± 4.56 | 10.8 ± 4.64 |

| 13b | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 34.8 ± 11.3 | 3.50 ± 0.80 |

| 13c | 0.016 ± 0.001 | > 100 | 3.24 ± 0.28 |

| 13d | 0.012 ± 0.001 | 24.2 ± 1.59 | 3.00 ± 0.48 |

| 13e | 0.013 ± 0.002 | 53.8 ± 10.4 | 4.23 ± 1.08 |

| 13f | 0.017 ± 0.002 | > 100 | 4.12 ± 1.15 |

| 13g | 0.010 ± 0.001 | 18.5 ± 3.06 | 2.48 ± 0.33 |

| 13h | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 46.6 ± 5.22 | 3.98 ± 0.74 |

| 13i | 0.015 ± 0.002 | 47.7 ± 7.03 | 2.09 ± 0.30 |

| 13j | 0.011 ± 0.001 | 41.0 ± 15.4 | 1.98 ± 0.65 |

| 13k | 0.016 ± 0.006 | 25.6 ± 3.12 | 2.69 ± 0.63 |

| 14a | 1.62 ± 0.30 | > 100 | 1.76 ± 0.54 |

| 14b | 2.87 ± 0.52 | > 100 | 1.53 ± 0.38 |

| 14c | 19.3 ± 8.80 | 18.4 ± 0.42 | 2.98 ± 0.21 |

| 14d | 0.07 ± 0.01 | > 100 | 8.05 ± 1.06 |

| 14e | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 8.86 ± 2.36 | 4.75 ± 0.92 |

| 14f | 0.50 ± 0.08 | > 100 | 3.38 ± 0.98 |

| 14g | 0.06 ± 0.005 | > 100 | 2.61 ± 0.52 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

4.2. Modification on the 8-Ketone Moiety in the Lobeline Molecule

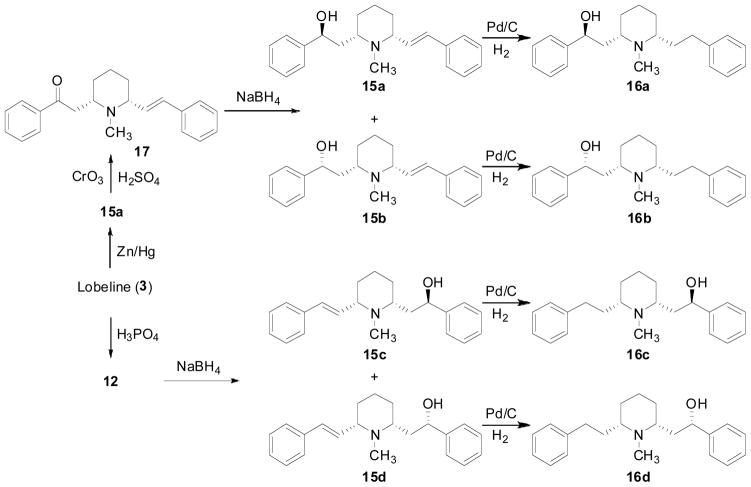

The carboxyl group of lobeline was stereoselectively reduced to lobelanidine 6, Fig. (3) by using LAH (Ebnother 1958) or NaBH4, or eliminated to form a series of des-keto analogs (15a–d and 16a–d) (Scheme 3) (Zheng, Horton et al. 2006). Compound 15a was prepared by Clemmensen reduction of lobeline (Flammia, Dukat et al. 1999). Oxidation of 15a to compound 17, an enantiomer of ketoalkene 12, by Jones oxidation, followed by NaBH4 reduction yielded a mixture of 15a and 15b; this which could be easily separated by silica gel column chromatography. Similarly, NaBH4 reduction of ketoalkene 12 afforded compounds 15c and 15d, which were obtained in an isomerically pure form using silica gel chromatography. Catalytic hydrogenation of the unsaturated compounds 15a, 15b, 15c, and 15d afforded the corresponding hydrolic compounds 16a, 16b, 16c, and 16d, respectively.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of des-keto analogs of lobeline.

Compared to lobeline, the dihydroxyl compound, lobelanidine (6) exhibited 200-fold lower affinity for α4β2* nAChRs, slightly higher affinity at α7* nAChRs, and 5-fold lower affinity at VMAT2 (Table 1) (Miller, Crooks et al. 2004). Des-keto lobeline analogs displayed diminished affinity at α4β2* and α7* nAChRs, except for compounds 15c and 16c, which had slightly higher affinity than lobeline at α7* nAChRs. The des-keto analogs had similar affinities for VMAT2 compared to lobeline (i.e., within one-order of magnitude); with compound 15b exhibiting the highest affinity of the series (Ki = 0.59 μM) (Table 3) (Zheng, Horton et al. 2006).

Table 3.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of des-keto Lobeline Analogs

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC Binding α4β2* nAChRa | [3H]MLA Binding α7* nAChRa | [3H]DTBZ Binding VMAT2a | |

| 15a | 9.75 ± 0.91 | > 100 | 6.44 ± 0.54 |

| 15b | > 100 | > 100 | 0.59 ± 0.15 |

| 15c | 4.19 ± 0.80 | 1.70 ± 0.32 | 5.16 ± 0.30 |

| 15d | > 100 | > 100 | 6.06 ± 0.45 |

| 16a | 1.77 ± 0.61 | 39.3 ± 12.9 | 3.09 ± 0.41 |

| 16b | > 100 | > 100 | 6.60 ± 2.96 |

| 16c | 2.36 ± 0.18 | 1.21 ± 0.09 | 1.98 ± 0.31 |

| 16d | 33.6 ± 8.54 | > 100 | 3.01 ± 0.44 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

4.3. DES-Oxygen Lobeline Analogs

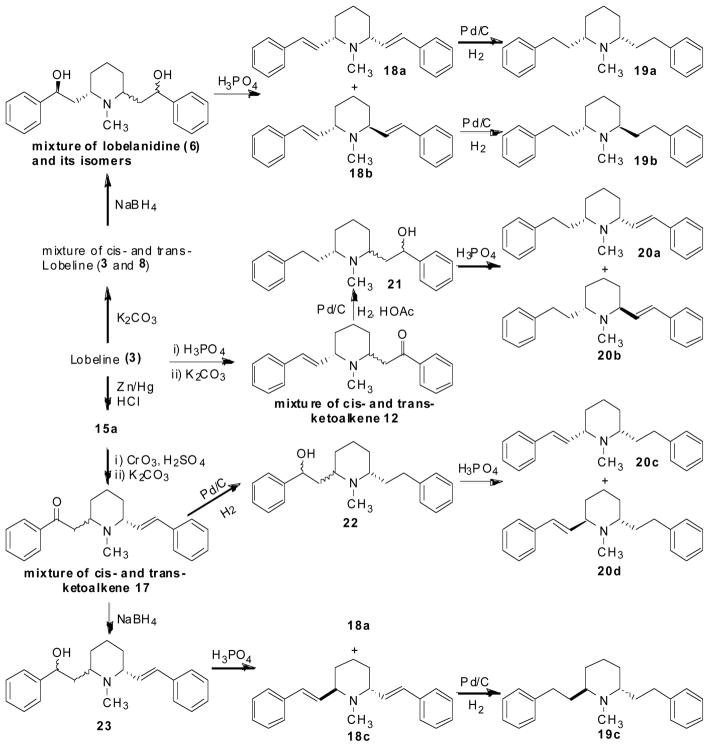

From the above structure-activity relationships, both the hydroxyl group and the carboxyl group of lobeline clearly are important for the high affinity for α4β2* nAChRs, but not important for VMAT2 interaction. A series of fully defunctionalized lobeline analogs, in which both of these two functional groups were removed from the molecule were synthesized and evaluated for affinity at VMAT2 assessed by inhibition of [3H]DTBZ binding to rat synaptic vesicle membranes (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). The synthesis of the defunctionalized analogs 18a–c, 19a–c, and 20a–d is illustrated in Scheme 4. Briefly, cis-lobeline (3) was treated with K2CO3/methanol to yield a mixture of the two C2 epimers, 3 and 8, which was then converted into a mixture of lobelanidine isomers via reduction with NaBH4. Treatment of the lobelanidine isomeric mixture with 85% phosphoric acid afforded a separable mixture of meso-transdiene (MTD, 18a), and (−)-trans-transdiene ((−)-TTD, 18b). The (+)-TTD (18c) isomer was separated from a mixture of 18a and 18c, obtained via successive oxidation and C6-epimerization of 15a. Catalytic hydrogenation of 18a, 18b, and 18c afforded lobelane (19a), (−)-2S, 6S-trans-lobelane ((−)-trans-lobelane, 19b), and (+)-2R, 6R-trans-lobelane ((+)-trans-lobelane, 19c), respectively. Simultaneous reduction of the double bond and the carbonyl group in the ketoalkene mixture (12) or the ketoalkene mixture (17) by catalytic hydrogenation each afforded compounds 21 (as a mixture of 4 isomers) and 22 (as a mixture of 4 isomers). .Dehydration of 21 and 22 with 85% H3PO4, respectively, followed by silica gel column chromatography separation, yielded compounds 20a, 20b, 20c, and 20d, respectively.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of fully defunctionalized lobeline analogs.

Results from the pharmacological analysis of this series of defunctionalized analogs are shown in Table 4. MTD (18a), the fully deoxygenated, unsaturated meso-compound, has no affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs, but had comparable affinity at VMAT2 (Ki = 9.88 μM) to lobeline. Reduction of the double-bonds in MTD afforded lobelane (19a, Ki = 0.97 μM at VMAT2), which was more selective for VMAT2 but only 3-fold more potent than lobeline at VMAT2. Reduction of either the C7 or the C9 double bond in MTD afforded enantiomers 20c and 20a, respectively, both of which had no affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs, but both isomers had 4-fold higher affinity at VMAT2 compared to MTD. The trans analogs of MTD (18b and 18c) had no affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs and exhibited comparable affinity for VMAT2 with respect to MTD. Surprisingly, no difference in affinity between these two trans enantiomers was observed at VMAT2. These results indicate a surprising lack of stereochemical sensitivity at the ligand recognition site at VMAT2 with these lobeline analogs because changes in the stereochemistry of the substituents at C2 and C6 of the piperidine ring from cis to trans within the MTD series (i.e., 18a to 18b and 18c) had no effect on affinity for VMAT2. The trans analogs of lobelane, 19b and 19c, exhibited a 5–6-fold decrease in affinity at VMAT2 compared to lobelane (19a). Again, the trans enantiomers 19b and 19c exhibited comparable affinities at VMAT2. Taken together, these data indicate that the VMAT2 binding site can accept major stereochemical changes to the MTD and lobelane molecules at the C2 and C6 piperidino ring carbons.

Table 4.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of Compounds 18a–c, 19a–c, 20a–d, 29, and 32–38.

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC binding α4β2* nAChRa | [3H]MLA binding α7* nAChRa | [3H]DTBZ binding VMAT2a | |

| 3 | 0.004 ± 0.000 | 6.26 ± 1.30 | 2.76 ± 0.64 |

| 18a | 11.6 ± 2.01 | >100 | 9.88 ± 2.22 |

| 18b | >100 | >100 | 19.4 ± 1.25 |

| 18c | >100 | >100 | 7.09 ± 2.42 |

| 19a | 14.9 ± 1.67 | 26.0 ± 6.57 | 0.97 ± 0.19 |

| 19b | >100 | 25.3 ± 4.27 | 5.32 ± 0.45 |

| 19c | >100 | 40.0 ± 14.1 | 6.46 ± 1.70 |

| 20a | >100 | >100 | 2.50 ± 0.23 |

| 20b | >100 | 55.1 ± 13.3 | 5.27 ± 1.32 |

| 20c | >100 | >100 | 2.67 ± 0.56 |

| 20d | >100 | 25.2 ± 3.00 | > 100 |

| 29 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 32 | 25.9 ± 1.62 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 33 | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 34 | 4.52 ± 0.58 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 35 | > 100 | > 100 | 2.37 ± 0.55 |

| 36 | > 100 | > 100 | 3.07 ± 1.72 |

| 37 | >100 | >100 | 5.21 ± 1.23 |

| 38 | >100 | >100 | 3.96 ± 0.80 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

Similarly, the enantiomers 20b and 20d showed low affinity at α4β2* or α7* nAChRs, but interestingly exhibited very different affinities for VMAT2. That is compound 20b had a similar affinity for VMAT2 compared to MTD,, whereas 20d exhibited low affinity for VMAT2. These results suggest a somewhat complex structure-activity relationship within these structurally-related analogs, in that the VMAT2 recognition site appears to accommodate three mono double bond isomers, with different stereochemistry at C2 and C6, but does not recognize one specific stereochemical form 20d, which has the 2R, 6R stereochemical configuration.

4.4. Fragmented Lobeline Analogs

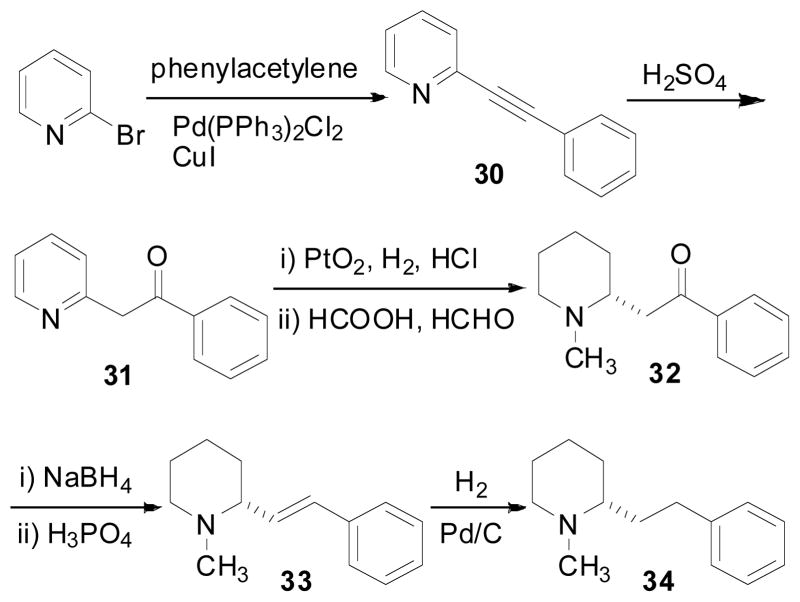

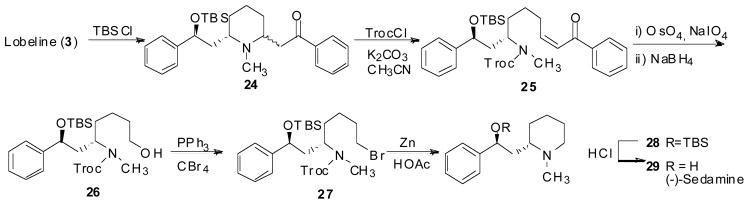

(−)-Sedamine (29) and compound 32, which represent the hydroxyl containing fragment and the keto containing fragment of lobeline, were synthesized to determine if the structure of the whole lobeline molecule is required for potent VMAT2 interaction. (−)-Sedamine was synthesized via a key ring opening reaction of the TBS protected lobeline (24) to afford compound 25. The double bond in compound 25 was then cleaved and the resulting aldehyde was reduced by NaBH4 to afford compound 26. Bromination of compound 26, followed by removal of the Troc group, cyclization, and removal of the TBS group, yielded the final product (Scheme 5) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2004). Compound 32 was synthesized via initial Sonogashira cross-coupling of 2-bromopyridine and phenylacetylene to form compound 30. Compound 30 was then hydrolyzed to the keto compound 31 with sulfuric acid. Hydrogenation of compound 31 over Adams’ catalyst followed by N-methylation afforded the final product (Scheme 6) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Compounds 29 and 32 exhibited low affinity at α4β2* nAChRs, α7* nAChRs and VMAT2 (Table 4) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005), suggesting that both the C2 and C6 side chains on the piperidine ring of lobeline are essential for VMAT2 affinity.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of (−)-sedamine.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of compounds 32, 33, and 34.

5. STRUCTURAL MODIFICATION OF LOBELANE

Systematic structural modification of the lobeline molecule provided lobelane (19a, Scheme 4), which exhibited high affinity (Ki of 0.97 μM) for the DTBZ binding site, on VMAT2, with low affinity for the α4β2* and α7* nAChRs (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Compared to lobeline, lobelane appears to be slightly more potent and selective at VMAT2, and lobelane is also effective in decreasing methamphetamine self-administration, suggesting that it may have potential as a novel treatment for methamphetamine abuse (Neugebauer, Harrod et al. 2007). Thus, systematic structural modifications based on lobelane molecule have been carried out in order to identify more selective and potent analogs at VMAT2, as well as analogs with improved physicochemical properties compared to lobelane.

5.1. Fragmented Lobelane Analogs

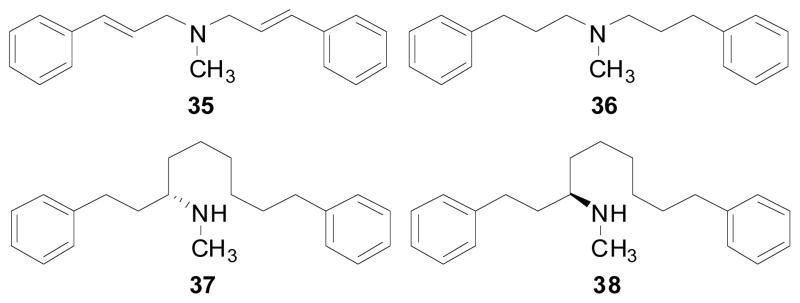

Similar to the lobeline series, structural fragments of MTD and lobelane (compounds 33 and 34, respectively; Scheme 6), were also prepared in order to determine if the whole molecule was required for potent VMAT2 interaction. Compounds 33 and 34 were synthesized from compound 32 as shown in Scheme 6 (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Interestingly, compound 34, in which one of the piperidine ring side chains of lobelane has been removed, showed 3-fold higher affinity at α4β2* nAChRs compared to lobelane, and exhibited no affinity at α7*. Compound 33, in which a trans-double bond has been introduced into the molecule, showed no affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs. Both of the fragmented compounds (33 and 34) exhibited low affinity at VMAT2 (Table 4) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). These results suggest that both the C2 and C6 side chains of the piperidine ring of MTD and/or lobelane are essential for VMAT2 affinity and selectivity. Compounds 35 and 36 Fig. (6), two other fragmented compounds in which the piperidine ring has been truncated, were also synthesized (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Compounds 35 and 36 exhibited no affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs and had affinity at VMAT2 similar to that of lobelane (Table 4) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). These results indicate that the nitrogen and two phenyl rings of lobelane are likely the essential pharmacophoric elements for recognition by the VMAT2 binding site. Interestingly, two open ring compounds, 37 and 38 Fig. (6), which are by-products from the hydrogenation reaction of 18b and 18c to form 19b and 19c, respectively, showed comparable affinity for VMAT2 compared to lobelane (Table 4) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005).

Fig. 6.

Structures of compounds 35, 36, 37, and 38.

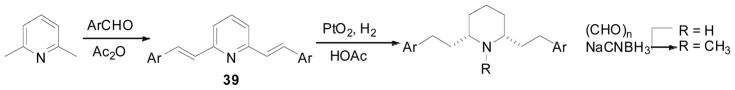

5.2. Modification of the Phenyl Rings of Lobelane

A series of lobelane analogs, in which the two phenyl rings were replaced by substituted phenyl rings or other aromatic ring systems, was synthesized (Scheme 7 and 8). The syntheses of analogs 40–60b (as shown in Table 5) were initiated from condensation reactions between 2,6-lutidine and appropriate aldehydes to form the conjugated products of general structure 39. Compounds of general structure 39 were reduced to the corresponding nor-compounds by Adams’ catalyzed hydrogenation. N-Methylation was then carried out using NaCNBH3/(CH2O)n to afford the corresponding N-methyl compounds (Scheme 7) (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005; Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). All the compounds synthesized in this series (Table 5) exhibited low affinity for both α4β2* and α7* nAChRs. With the exception of compounds 51a and 54a, which exhibited low affinity at VMAT2, all other compounds exhibited comparable affinity for VMAT2 relative to lobelane, i.e., within about one-order of magnitude. The 3-fluoro, 2-methoxy, and 3-methoxy, substituted analogs (42b, 44b, and 45b, respectively) had the highest affinity (Ki = 0.43–0.57 μM) at VMAT2 among the mono-substituted analogs series (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Among the di-substituted series, 3,4-methylenedioxy, 3,5-difluoro, 2,3-dimethoxy, and 2,5-dimethoxy substituted analogs (47b, 56b, 59b, and 60b, respectively) showed the highest affinity (Ki = 0.29–0.62 μM) at VMAT2 (Culver et al, 2010). Interestingly, there were no marked differences in VMAT2 affinity between analogs bearing either electron donating or withdrawing substituents. Also, the N-methyl analogs generally had higher affinity at VMAT2 compared to their corresponding nor-analogs.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of compounds 40–60b in Table 5.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of compounds 63–68 in Table 5.

Table 5.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of Compounds 41–60, 63–67, 70 and 71.

| Compd | Ar (Het) | R | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC binding α4β2* nAChRa | [3H]MLA binding α7* nAChRa | [3H]DTBZ binding VMAT2a | |||

| lobelane | phenyl | CH3 | 14.9 ± 1.67 | 26.0 ± 6.57 | 0.97 ± 0.19 |

| nor-lobelane | phenyl | H | >100 | >100 | 2.31 ± 0.21 |

| 41a | 2-fluorophenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 1.60 ± 0.10 |

| 41b | 2-fluorophenyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 1.07 ± 0.07 |

| 42a | 3-fluorophenyl | H | > 100 | 49.2 ± 21.3 | 1.60 ± 0.08 |

| 42b | 3-fluorophenyl | CH3 | > 100 | 16.6 ± 3.47 | 0.57 ± 0.07 |

| 43a | 4-fluorophenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 1.25 ± 0.08 |

| 43b | 4-fluorophenyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 0.98 ± 0.31 |

| 44a | 2-anisolyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 1.87 ± 0.19 |

| 44b | 2-anisolyl | CH3 | > 100 | 29.7 ± 7.73 | 0.58 ± 0.04 |

| 45a | 3-anisolyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 1.67 ± 0.07 |

| 45b | 3-anisolyl | CH3 | > 100 | 25.1 ± 2.23 | 0.43 ± 0.03 |

| 46a | 4-anisolyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 3.32 ± 0.82 |

| 46b | 4-anisolyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 1.73 ± 0.20 |

| 47a | 3,4-methylenedioxy-phenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 2.34 ± 0.16 |

| 47b | 3,4-methylenedioxy-phenyl | CH3 | > 100 | 18.2 ± 6.87 | 0.52 ± 0.25 |

| 48a | 4-methylphenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 3.23 ± 0.10 |

| 48b | 4-methylphenyl | CH3 | >100 | > 100 | 4.36 ± 0.18 |

| 49a | 3-trifluoromethylphenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 9.90 ± 2.01 |

| 49b | 3-trifluoromethylphenyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 1.51 ± 0.07 |

| 50a | 2,4-dichlorophenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 1.32 ± 0.18 |

| 50b | 2,4-dichlorophenyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 1.04 ± 0.06 |

| 51a | 4-phenylphenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | > 100 |

| 51b | 4-phenylphenyl | CH3 | > 100 | > 100 | 10.7 ± 6.60 |

| 52a | 4-acetoxyphenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 5.96 ± 1.76 |

| 52b | 4-hydroxyphenyl | H | > 100 | > 100 | 5.26 ± 0.47 |

| 53a | 1-naphthyl | H | >100 | >100 | 4.68 ± 0.70 |

| 53b | 1-naphthyl | CH3 | >100 | >100 | 0.63 ± 0.16 |

| 54a | 2-naphthyl | H | >100 | >100 | >100 |

| 54b | 2-naphthyl | CH3 | >100 | >100 | 2.03 ± 0.45 |

| 55 | 3-chlorophenyl | H | - | - | 3.88 ± 0.43 |

| 56a | 3,5-difluorophenyl | H | - | - | 5.24 ± 1.81 |

| 56b | 3,5-difluorophenyl | CH3 | - | - | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| 57a | 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl | H | - | - | 2.57 ± 0.48 |

| 57b | 3,5-dimethoxyphenyl | CH3 | - | - | 2.87 ± 0.83 |

| 58a | 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl | H | - | - | 29.0 ± 5.00 |

| 58b | 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl | CH3 | - | - | 5.93 ± 1.40 |

| 59a | 2,3-dimethoxyphenyl | H | - | - | 2.08 ± 0.10 |

| 59b | 2,3-dimethoxyphenyl | CH3 | - | - | 0.62 ± 0.02 |

| 60a | 2,5-dimethoxyphenyl | H | - | - | 2.70 ± 0.70 |

| 60b | 2,5-dimethoxyphenyl | CH3 | - | - | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| 63 | 2-pyridinyl | - | - | - | 5.87 ± 1.72 |

| 64 | 3-pyridinyl | - | - | - | 33.3 ± 16.3 |

| 65 | 2-quinolinyl | - | - | - | 0.96 ± 0.37 |

| 66 | 4-quinolinyl | - | - | - | 2.64 ± 1.41 |

| 67 | 2-(N-methyl)pyrrolyl | - | - | - | 9.21 ± 1.65 |

| 70 | 1-naphthyl | - | - | - | 1.02 ± 0.30 |

| 71 | 1-anisolyl | - | - | - | 0.83 ± 0.23 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

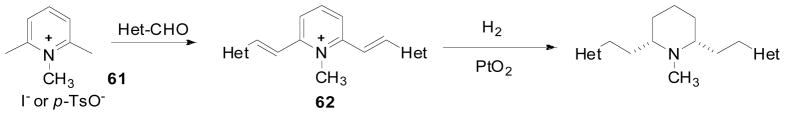

The syntheses of analogs 63–67, in which the two phenyl rings of lobelane have been replaced by two hetero-aromatic rings, were initiated from condensation reaction between N-methylated 2,6-lutidine (61) and appropriate aldehydes to form compound 62. Adams’ catalyzed hydrogenation of compound 62 afforded the final products (Scheme 8) (Vartak et al., 2010). These analogs displayed affinities that were 5 to 10-fold lower at VMAT2 compared to lobelane, with the exception of 2-quinolinyl compound 65, which showed similar affinity to lobelane at VMAT2 (Table 5; Vartak et al., 2010). It would appear that a neutral aryl substituent is highly preferred by the putative binding site on VMAT2, since only the quinolyl compounds 65 and 66, which can potentially remain uncharged at physiological pH, retained the affinity of lobelane toward VMAT2.

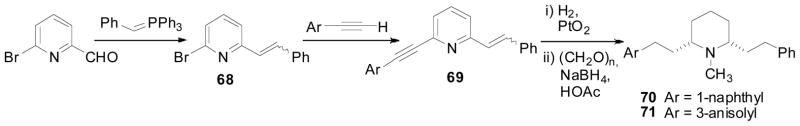

Two asymmetric lobelane analogs 70 and 71, which incorporate non-identical aromatic moieties at the C2, C6 of the piperidine ring, were also prepared. A Wittig reaction of 2-bromo-6-pyridincarboxaldehyde with benzyl ylid, followed by Sonogashira coupling with 1-ethynylnaphthalene or 3-ethynylanisole furnished the key intermediate, compound 69. Adams’ catalyzed hydrogenation of compound 69 followed by N-methylation provided the final products (Scheme 9; Crooks et al., 2010). Both compounds 70 and 71 exhibited similar affinity at VMAT2 when compared to that of lobelane, and slightly lower affinity at VMAT2 compared to their corresponding symmetric bis-1-naphthyl analog (53b) and bis-3-anisolyl analog (45b) (Table 5).

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of compounds 70 and 71.

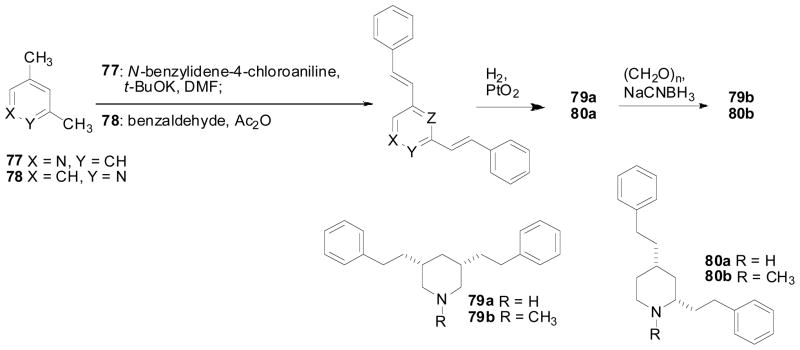

5.3. Isomerized Lobelane Analogs

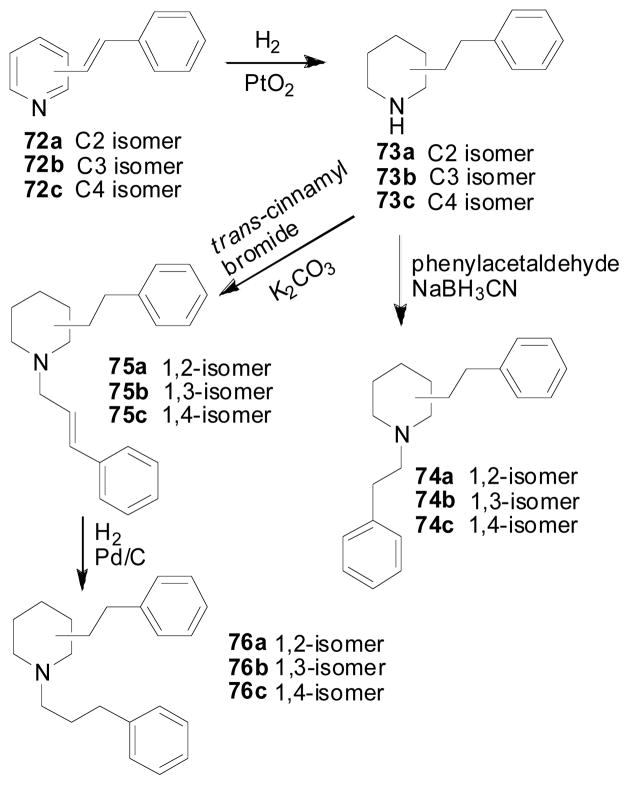

To further understand the importance of the juxtaposition and stereochemistry of the piperidino C2 and C6 substituents in the lobelane molecule, and the importance of the intramolecular distance between the nitrogen atom and the phenyl rings of lobelane, compounds 74a–76a, 74b–76b, 74c–76c, 79a, 79b, 80a, and 80b were synthesized (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). In these compounds, the C2, C6 phenethyl groups of lobelane were moved to the N1, C2; N1, C3; N1, C4; C3, C5; or C2, C4 positions around the piperidine ring. Analogs with one side chain attached to the nitrogen atom of the piperidine ring, i.e., 74a–76a, 74b–76b, and 74c–76c, were synthesized from initial condensation reaction of 2, 3, or 4-picoline with benzaldehyde. Adams’ reduction of the resulting conjugated products 72a–72c, followed by N-alkylation afforded compounds 74a–74c and 75a–75c. Reduction of the double bond in compounds 74a, 74b, and 74c by catalytic hydrogenation afforded compounds 76a, 76b, and 76c, respectively (Scheme 10). The synthesis of compounds 80a, and 80b was similar to the synthesis of nor-lobelane and lobelane, except that 2,4-lutidine was used as a starting material instead of 2,6-lutidine (Scheme 11). Similar procedures were also employed for the synthesis of compounds 79a and 79b. In the condensation reaction, N-benzylidene-4-chloroaniline was used as an activated form of benzaldehyde, due to the low activity of the 3-methyl group of the pyridinyl moiety (Scheme 11). Most of these compounds showed low affinity at either α4β2* or α7* nAChRs. All of these analogs retained affinity at VMAT2, but were 2–10-fold less potent than lobelane (Table 6). Analogs bearing a side chain at the piperidino C3 position, i.e., 74b, 75b, 76b, 79a and 79b, exhibited 3–10-fold lower potency at VMAT2 compared with lobelane. Thus, surprisingly, the position of the piperidine nitrogen atom relative to the C2 and C6 side chains does not appear to be critical for interaction with the VMAT2 binding site. The most potent compounds at VMAT2 in this series were 74c and 80a (Ki = 1.87 and 1.36 μM, respectively), in which the two side chains are located on the piperidino N1, C4 or C2, C4 positions. These results also indicate that the VMAT2 binding site can tolerate changes in distance between the piperidine nitrogen and the two phenyl rings.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of compounds 74a–74c, 75a–75c, and 76a–76c.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of compounds 79a, 79b, 80a, and 80b.

Table 6.

α4β2*, α7* nAChR, and VMAT2 Binding Affinity of 74a–76a, 74b–76b, 79a, 79b, 80a, 80b, 83a–d, 84a–d, 86a–d, 87a, 87b, 88a, 88b and 89–93.

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| [3H]NIC Binding α4β2* nAChRa | [3H]MLA Binding α7* nAChRa | [3H]DTBZ Binding VMAT2a | |

| lobelane | 14.9 ± 1.67 | 26.0 ± 6.57 | 0.97 ± 0.19 |

| 74a | > 100 | 66.9 ± 27.4 | 3.32 ± 0.74 |

| 75a | > 100 | > 100 | 3.11 ± 0.51 |

| 76a | > 100 | 9.02 ± 1.54 | 3.35 ± 0.80 |

| 74b | > 100 | > 100 | 3.95 ± 0.61 |

| 75b | > 100 | > 100 | 10.5 ± 1.58 |

| 76b | > 100 | > 100 | 4.04 ± 1.76 |

| 74c | 7.62 ± 1.47 | > 100 | 1.87 ± 0.25 |

| 75c | > 100 | > 100 | 3.28 ± 1.65 |

| 76c | > 100 | > 100 | 2.47 ± 0.70 |

| 79a | > 100 | > 100 | 6.11 ± 0.92 |

| 79b | > 100 | > 100 | 11.7 ± 0.65 |

| 80a | > 100 | > 100 | 1.36 ± 0.11 |

| 80b | > 100 | > 100 | 2.62 ± 0.51 |

| 83a | - | - | 3.35 ± 0.78 |

| 83b | - | - | 3.17 ± 0.58 |

| 83c | - | - | 3.36 ± 0.72 |

| 83d | - | - | 5.29 ± 0.96 |

| 84a | - | - | 0.30 ± 0.11 |

| 84b | - | - | 0.63 ± 0.27 |

| 84c | - | - | 2.68 ± 0.44 |

| 84d | - | - | 3.62 ± 0.59 |

| 86a | > 100 | > 100 | 12.3 ± 4.70 |

| 86b | > 100 | > 100 | 31.8 ± 5.84 |

| 86c | > 100 | > 100 | 2.57 ± 0.63 |

| 86d | > 100 | > 100 | 3.92 ± 0.19 |

| 87a | > 100 | > 100 | 3.42 ± 0.26 |

| 87b | > 100 | > 100 | 16.0 ± 2.83 |

| 88a | > 100 | > 100 | 41.0 ± 14.0 |

| 88b | > 100 | > 100 | 4.60 ± 1.70 |

| 89 | > 100 | > 100 | 7.27 ± 2.28 |

| 90 | > 100 | > 100 | 10.4 ± 2.62 |

| 91 | > 100 | > 100 | 91.3 ± 26.2 |

| 92 | > 100 | > 100 | 15.5 ± 1.61 |

| 93 | > 100 | > 100 | 32.6 ± 6.79 |

n =3–6/compound/assay

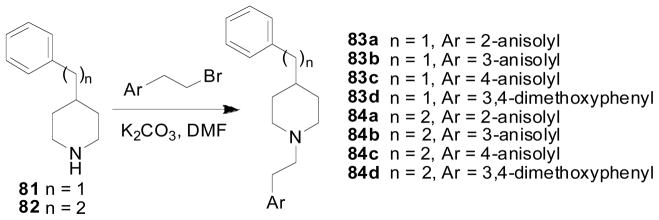

Based the interesting data obtained on compound 74c, a series of N1, C4 lobelane analogs, in which one of the phenyl ring was replaced by an anisolyl or dimethoxyphenyl ring, was synthesized (Scheme 12). The 2-methoxy and 3-methoxy substituted analogs, 84a and 84b, exhibited similar affinity (Ki = 0.30 and 0.63 μM, respectively) at VMAT2 compared to lobelane and 74c (Table 6) (Culver et al., 2010).

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of compounds 83a–d, and 84a–d.

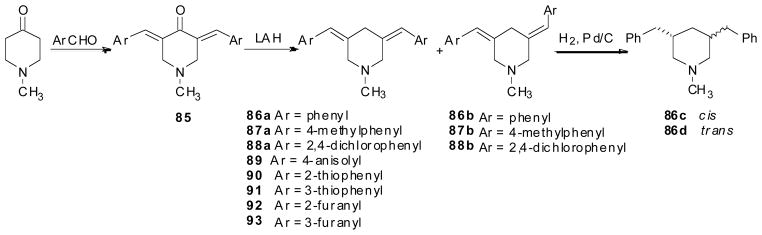

A series of isomerized MTD analogs, including 86a–88a, 86b–88b and 89–93, in which the C2, C6 side chains in MTD were moved to C3, C5, while the carbon numbers between nitrogen and the aromatic rings were retained, was also synthesized. These analogs generally displayed similar affinity at VMAT2 compared with MTD. Compounds 86c and 86d, two isomerized lobelane analogs containing a linker unit that is one carbon shorter between the piperidine and the phenyl rings than compound 79b, displayed a 3-fold increase in affinity at VMAT2 compared with compound 79b (Table 6) (Horton et al, submitted).

5.4. Modification on the two Ethylene Groups of Lobelane

To determine the optimal bridge lengths between the piperidine ring and each of the two phenyl rings in lobelane, a series of lobelane homologs, in which the two ethylene groups connecting the two phenyl rings to the C-2 and C-6 positions of the piperidine ring in lobelane have been replaced by carbon linkers of a range of different length (0–3 carbons), i.e., combinations of 0,0-, 0,1-, 0,2-, 0,3-, 1,1-, 1,2-, 1,3-, 2,3-, and 3,3-carbons on each side of piperidine ring, were synthesized as ligands for VMAT2 (Table 7)[90]. The removal of the two-carbon bridge on both sides of the piperidine ring of lobelane to generate compound 94 eliminated binding at VMAT2. Compounds 95b, 96b, and 97b, which contain no carbon bridge on one side, and a one-, two, or three-carbon bridge, respectively, on the other side of the piperidine ring, had 14–40-fold lower affinity at VMAT2 compared to lobelane. The reduction of one methylene unit on each side of the two-carbon bridge of lobelane to afford compound 98b resulted in a 20-fold decrease in VMAT2 affinity compared to lobelane. Increasing the length of one side of the bridge in compound 98b by one or two methylene units to afford compounds 99b and 100b afforded an improvement in affinity (Ki = 2.77 and 1.62 μM, respectively),at VMAT2 compared to 98b, similar to lobelane. The addition of a methylene unit to one side or both sides of the piperidine ring in lobelane to produce longer homologs, compounds 101b and 102b, respectively, had no effect on VMAT2 affinity compared to lobelane. Compound 101b (Ki = 0.88 μM) had similar potency to lobelane. Compounds 95a–102a, exhibited affinities at VMAT2 within an order-of-magnitude compared to their corresponding methylated analogs 95b–102b, which is consistent with the SAR observed in the previous lobelane analog series [90]. These results indicate that retention of binding affinity at VMAT2 found for lobelane, structurally-related homologs require linkers lengths between the central piperidine and two phenyl rings to be no shorter than one methylene group on one side of the piperidine ring and no shorter than two methylene group on the other side of the piperidine ring. The optimal methylene unit lengths are a combination of two and three methylene units.

Table 7.

VMAT2 binding affinity of compounds 94–102.

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[3H]DTBZ binding, VMAT2a | |||

| R | m | n | ||

| lobelane | CH3 | 2 | 2 | 0.97 ± 0.19 |

| 94 | CH3 | 0 | 0 | >100 |

| 95a | H | 0 | 1 | 24.1 ± 6.10 |

| 95b | CH3 | 0 | 1 | 13.6 ± 8.14 |

| 96a | H | 0 | 2 | 28.4 ± 7.30 |

| 96b | CH3 | 0 | 2 | 16.1 ± 4.07 |

| 97a | H | 0 | 3 | 28.6 ± 2.44 |

| 97b | CH3 | 0 | 3 | 62.5 ± 16.6 |

| 98a | H | 1 | 1 | 7.68 ± 1.44 |

| 98b | CH3 | 1 | 1 | 10.5 ± 3.36 |

| 99a | H | 1 | 2 | 12.2 ± 0.19 |

| 99b | CH3 | 1 | 2 | 2.77 ± 1.77 |

| 100a | H | 1 | 3 | 1.13 ± 0.28 |

| 100b | CH3 | 1 | 3 | 1.62 ± 0.39 |

| 101a | H | 2 | 3 | 4.60 ± 0.56 |

| 101b | CH3 | 2 | 3 | 0.88 ± 0.30 |

| 102a | H | 3 | 3 | 4.50 ± 1.02 |

| 102b | CH3 | 3 | 3 | 1.00 ± 0.23 |

n =3–6/compound

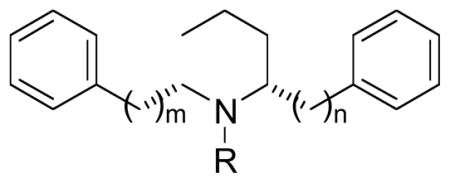

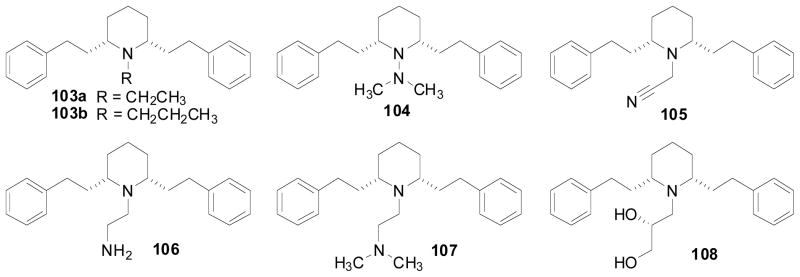

5.5. Modification on the n-Methyl Group of Lobelane

A series of modifications on the nitrogen atom of the piperidine ring of lobelane was carried out Fig. (7). Nor-lobelane (40, Ki = 2.31 μM), N-ethyl lobelane (103a, Ki = 3.41 μM) or N-n-propyl lobelane (103b, Ki = 1.87 μM) exhibited similar affinity for VMAT2 compared to lobelane (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). Replacing the N-methyl group in lobelane with a dimethylhydrazine group afforded compound 104, which exhibited no affinity at VMAT2. Replacing the N-methyl group in lobelane with an acetylnitrile, an ethylamine, or an ethyldimethylamine group afforded compound 105, 106, or 107, respectively, which exhibited 5–20-fold lower affinity at VMAT2 compared to lobelane. Interestingly, compound 108, which contains a 1,2(R)-dihydroxylpropyl group on the piperidine nitrogen, displayed similar affinity (Ki = 0.56 μM) at VMAT2 (Table 8) compared to lobelane (Zheng et al., 2010). Importantly, 108 is a more water soluble analog of lobelane, with obvious advantages for clinical development.

Fig. 7.

Structures of compounds 103a–b, and 104–108.

Table 8.

VMAT2 Binding Affinity of

| Compd | [3H]DTBZ binding, VMAT2 Ki, μM ± SEM |

|---|---|

| lobelane | 0.97 ± 0.19a |

| nor-lobelane | 2.31 ± 0.21 |

| 103a | 3.41 ± 0.67 |

| 103b | 1.87 ± 0.25 |

| 104 | > 100 |

| 105 | 22.6 ± 0.23 |

| 106 | 5.59 ± 0.94 |

| 107 | 9.59 ± 1.47 |

| 108 | 0.56 ± 0.08 |

| 109 | 12.7 ± 1.09 |

| 110 | 15.5 ± 3.90 |

| 111 | 17.7 ± 4.66 |

| 112 | 25.0 ± 3.08 |

| 113 | 24.9 ± 3.07 |

5.6. Modification on the Piperidine Ring of Lobelane

5.6.1. Introduction of an Oxygen Atom at the C4 of Piperidine Ring

By introduction of an oxygen atom (ketone or hydroxyl group) at the C4 position of the piperidine ring of lobelane, analogs 109–113 incorporate some structural features of the TBZ and DTBZ molecules, which were thought to improve affinity at VMAT2 Fig. (8). Interestingly, all the analogs in this series displayed more than 10-fold lower affinity at VMAT2 when compared to lobelane, indicating that lobelane and TBZ may bind differently at VMAT2 (Table 8) (Zheng et al., submitted).

Fig. 8.

Structures of compounds 109–113.

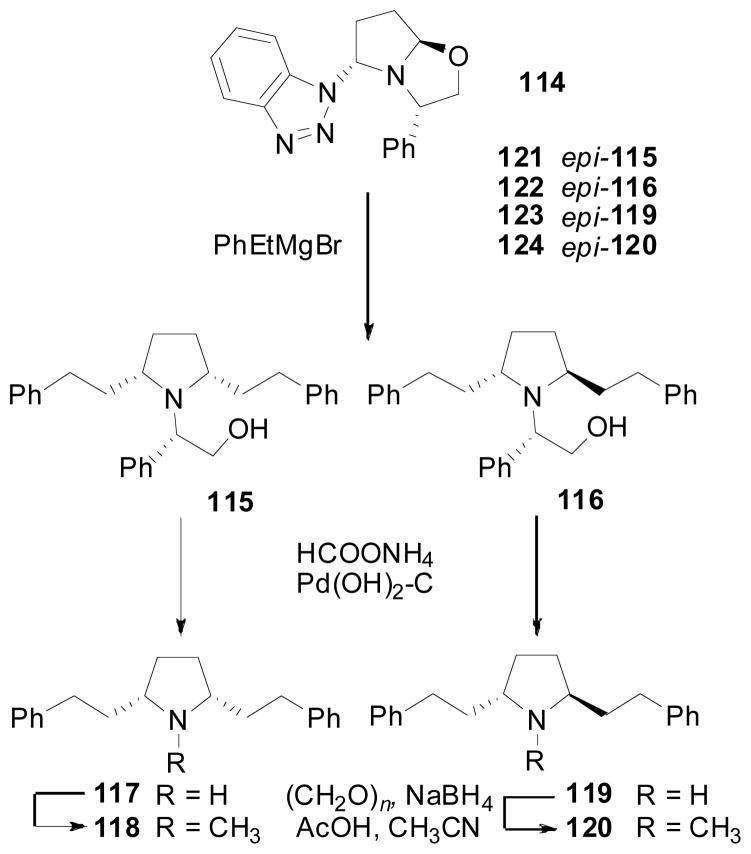

5.6.2. Replacing the Piperidine Ring in Lobelane with a Pyrrolidine Ring

Subtle conformational changes caused by contraction of the central piperidine ring to the 5-membered pyrrolidine can be expected to affect the 3-dimensional projection of the C2, C6 substituents, as well as the direction of the N-substituent. Such compounds were prepared via the addition of Grignard reagents to Katritzky’s bicyclic hemiaminal (114; Scheme 14), followed by elaboration of the separable diastereomers (115 and 116) into the requisite pyrrolidine compounds (117–120) (Katritzky, Cui et al. 1999). Enantiomers of compounds 115, 116, 119 and 120 (compounds 121, 122, 123 and 124, respectively) were similarly obtained from the epimer of compound 114.

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of compounds 115–124.

The nor-analog (117) exhibited an order-of-magnitude higher affinity at VMAT2 than its N-methylated analog (118; Table 9), which is in sharp contrast to the higher affinity of the N-methyl analog usually observed in the corresponding piperidine (lobelane) series. N-Substitutions as large as a phenethyl substituent (compounds 115, 116, 121, 122) did not decrease binding affinity within this series of pyrrolidine compounds [92]. The relative stereochemistry of substitutions at the C2 and C5 positions also seems to be of little consequence with regard to affinity for VMAT. The overall affinity of the pyrrolidine compounds, with the exception of 118, does not vary substantially within the series. Clearly, replacement of the central piperidine ring with a pyrrolidine ring does not afford compounds with enhanced affinity when compared to lobelane.

Table 9.

VMAT2 Binding Affinity of Pyrrolidino Analogs 115–126, 128a–128c, 129a–129c, and 131

| Compd | Ki, μM ± SEM |

|---|---|

| [3H]DTBZ binding, VMAT2a | |

| lobelane | 0.97 ± 0.19 |

| nor-lobelane | 2.31 ± 0.21 |

| 115 | 2.75 ± 0.63 |

| 116 | 4.79 ± 0.71 |

| 117 | 1.50 ± 0.22 |

| 118 | 14.5 ± 2.13 |

| 119 | 3.02 ± 0.17 |

| 120 | 8.80 ± 2.30 |

| 121 | 5.05 ± 1.05 |

| 122 | 4.34 ± 0.71 |

| 123 | 3.40 ± 0.30 |

| 124 | 3.97 ± 0.64 |

| 125 | 36.7 ± 20.3 |

| 126 | 6.09 ± 0.19 |

| 128a | 1.30 ± 0.21 |

| 128b | 1.38 ± 0.20 |

| 128c | 4.80 ± 1.70 |

| 129a | > 100 |

| 129b | > 100 |

| 129c | 3.88 ± 0.90 |

| 131 | 3.95 ± 0.54 |

n =3–6/compound

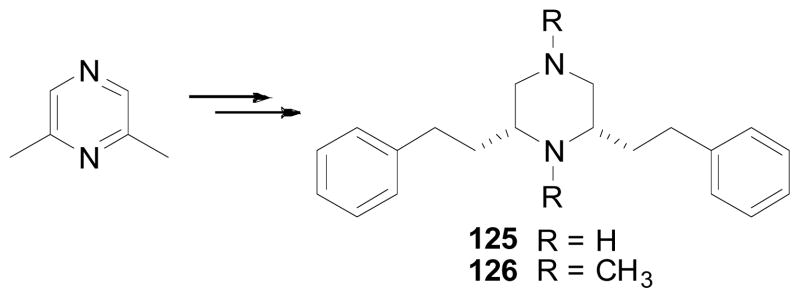

5.6.3. Replacing the Piperidine Ring in Lobelane with a Piperizine Ring

Further modification on the piperidine ring of lobelane has been carried out by replacing the piperidine ring with a piperizine ring (compounds 125 and 126), which can be achieved by employment of a similar approach as described in Scheme 7 (Scheme 15). Compounds 125 and 126 were 36- and 6-fold less potent at VMAT2, respectively, compared to lobelane (Table 9).

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of compounds 125 and 126.

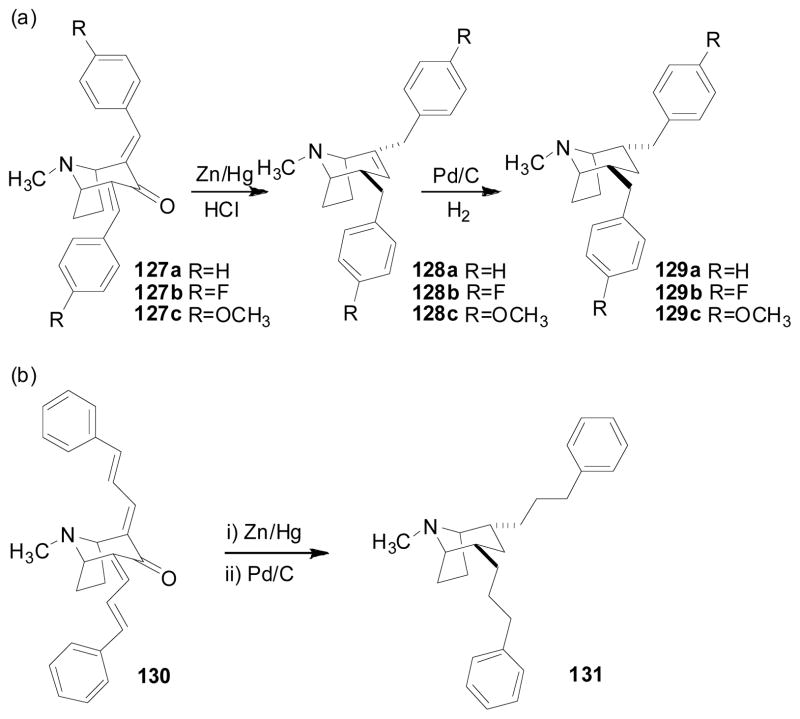

5.6.4. Replacing the Piperidine Ring in Lobelane with a Tropane Ring

Compounds 128a, 128b, 128c, 129a, 129b, 129c, and 131, in which the more conformationally- restricted tropane ring was substituted for the piperidine ring in lobelane, were synthesized (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005). The general methodology for the preparation of these analogs is summarized in Scheme 16. Compounds 127a–127c and 130 were obtained by aldol condensation of tropinone with benzaldehyde, 4-fluorobenzaldehyde, 4-methoxybenzaldehyde or trans-cinnamaldehyde. Clemmensen reduction of compounds 127a, 127b or 127c afforded compounds 128a, 128b or 128c, respectively. Compounds 129a, 129b, and 129c were each obtained by catalytic hydrogenation of the corresponding precursor molecules, compounds 128a, 128b and 128c. Clemmensen reduction of compound 130, followed by catalytic hydrogenation afforded compound 131.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of compounds 128a–c, 129a–c, and 131.

The trop-2-ene compounds 128a and 128b exhibited similar affinity (Ki = 1.30 μM and 1.38 μM, respectively) at VMAT2 to that of lobelane (Table 9). Interestingly, compounds 129a and 129b, which are saturated analogs of 128a and 128b, respectively, had no affinity (both with Ki > 100 μM) for VMAT2. These results suggest that the double bond in compounds 128a and 128b is important for VMAT2 binding. In this respect, the double bond affects both the configuration of the tropane ring and the orientations of two side chains at C-2 and C-4. In particular, the molecules of 128a and 128b are more extended than the corresponding reduced analogs, i.e., compounds 129a and 129b. Compound 128c, in which an electron donating methoxy group was introduced into the para position of each of the two phenyl rings, exhibited lower potency (Ki = 4.80 μM) at VMAT2 compared to either lobelane, compound 128a or compound 128b. Surprisingly, in contrast to compounds 129a and 129b, when the double bond in compound 128c was reduced to afford the tropane analog, compound 129c, the affinity of compound 129c (Ki = 3.88 μM) at VMAT2 was retained. Thus, the electron density in the phenyl rings may influence binding at VMAT2. However, compound 129c is more extended than either 129a or 129b, because of the presence of the para-methoxy groups. Thus, full extension of the molecule in these tropane analogs also may be important for VMAT2 binding. Compound 131, which incorporates an increased distance between the phenyl rings and the C2, C4 atoms of the tropane ring compared to compound 129a, had a Ki value of 3.95 μM at VMAT2. Similar to compound 129c, compound 131 is a more extended molecule than compound 129a, which may be the reason for the observed increase in VMAT2 affinity (Zheng, Dwoskin et al. 2005).

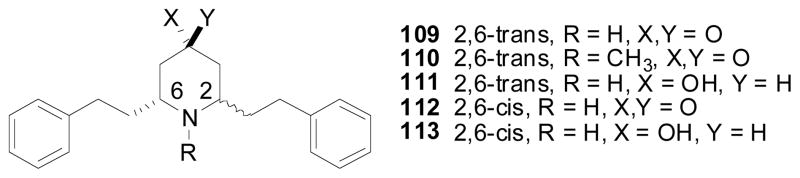

6. COMPUTATIONAL NEURAL NETWORK ANALYSIS OF THE AFFINITY OF LOBELINE ANALOGS FOR VMAT2

Towards the discovery of more potent, novel and selective lobeline analogs as ligands for VMAT2, we considered computational modeling as a valuable aid in drug design and optimization. In this respect, the nature of the interaction of these novel ligands with binding site(s) on VMAT2 is not known due to the lack of a crystal structure of this protein. Thus, a structure-based drug design approach is not available. On the other hand, artificial neural network (ANN) approaches, such as back-propagation network to data analysis, has received much attention over the last decade. This artificial system emulates the function of the brain, in which a very high number of information-processing neurons are interconnected and are known for their ability to model a wide set of functions, including linear and non-linear functions, without knowing in advance the analytic forms[94]. By use of an ANN that simulates the processes of brain neurons, one can train the network to solve many types of problems. The rapid advancement of computing systems in the past 20 years led to the success of this machine-learning approach in various engineering, business, and medical applications. One of the best known and widely used applications is NETtalk [95], an application of an ANN for machine reading of text. Most recently, the ANN approach also has been applied in a variety of biomedical areas, which includes analysis of appendicitis [96], cancer imaging extraction and classification [97], and AIDS research and therapy [98]. Relevant to this chapter, this approach has also been used in drug design and discovery, in such areas as prediction of molecular bioactivity [99–102]. Pharmaceutical applications utilizing this approach include pharmaceutical production development [103], pharmacodynamic modeling [104], and mapping dose-effect relationships to pharmacological response. [105].

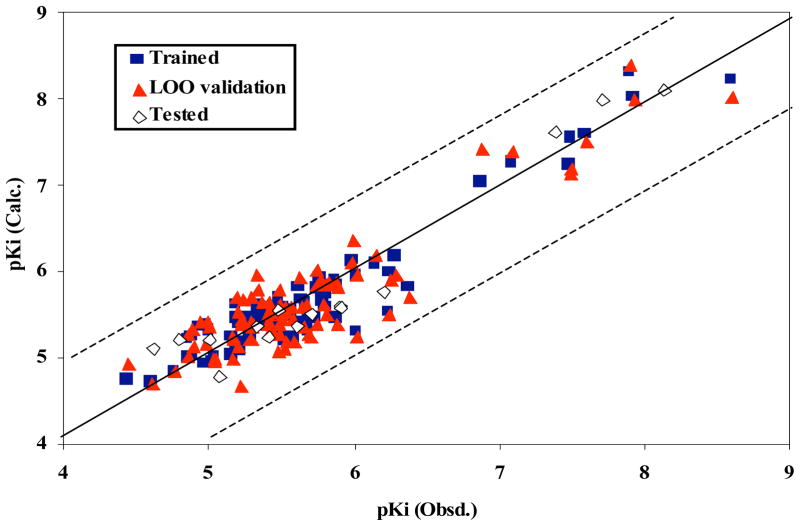

In our recent study, the ANN approach was used to build a quantitative SAR (QSAR) model on a set of 104 TBZ and lobeline analogs with known affinity for VMAT2 [103]. This is the first QSAR modeling study that has addressed the interaction of a small library of ligands at the VMAT2 binding site. Most of the entities in the library were lobeline analogs. TBZ and its analogs were introduced into the dataset as they represent ligands having high affinity for VMAT2. The affinity of the lobeline analogs were measured using [3H]DTBZ as a probe, thus the same bioactivity endpoint was used for the entire set of 104 compounds in this QSAR study. With high activity analogs in a training set, the trained model would have a better chance of identifying the features that lead to high affinity novel analogs. The goal of the QSAR work were: (i) to extract the relevant descriptors to establish the QSAR of the library of ligands, (ii) to establish the high predictive power of ANN modeling of this library of compounds, and (iii) to develop insights regarding the relationship between the descriptors of the compounds and their affinity for VMAT2.

The QSAR study revealed that while the linear partial least squares model built from the same dataset is predictive, the fully interconnected three-layer neural network model trained with the back-propagation procedure was superior learning the correct association between a set of relevant descriptors of compounds and the log(1/Ki) for VMAT2 [106]. The optimal ANN architecture was determined as 11:3:1, i.e. eleven input, three hidden and one output neuron(s). The eleven related descriptors (shown in Table 10) constructed the input vector for the input neurons of the ANN. These descriptors were composed of topological, geometrical, GETAWAY, aromaticity, and WHIM descriptors. Evaluation of the contributions of the descriptors to the QSAR reflected the importance of atomic distribution in the molecules, molecular size, and steric effects of the ligand molecules when interacting with their target binding site on VMAT2. Statistical analysis for the trained ANN indicated that the computed activities were in excellent agreement with the experimentally observed values (r2 = 0.91, rmsd = 0.225; predictive q2 = 0.82, loormsd = 0.316). The generated models were further tested by use of an external prediction set of 15 molecules. The nonlinear ANN model had r2 = 0.93 and root-mean-square errors of 0.282 compared with the experimentally measured activities of the test set Fig. (9). Furthermore, the stability test of the model with regard to data division was performed. The dataset of 104 molecules was randomly divided into two sets; one set of 89 molecules for training and leave-one-out validation, and the other set of 15 molecules for external testing. Among each division, the dissimilarity of one test set from the test set of another division was greater than 90%. This process was randomly repeated five times. The same eleven descriptors, learning epochs (200,000) and ANN architecture were used to train and test the ANN models. The data in Table 11 shows that the trained 11-3-1 ANN models are stable with regard to the data division, indicating that the generated model is reliable and predictive.

Table 10.

Brief Description of the Descriptors Used in the PLS and Nonlinear Neural Network Analyses.

| Descriptor | Definition | Typea |

|---|---|---|

| Ram | Ramification index | 1 |

| PW5 | Path/walk 5-Randic shape index. | 1 |

| LP1 | Lovasz-Pelikan index [leading eigenvalue]. | 1 |

| SEige | Eigenvalue sum from electronegativity weighted distance matrix. | 1 |

| VEp2 | Average eigenvector coefficient sum from polarizability weighted distance matrix. | 1 |

| DISPm | d COMMA2 value/weighted by atomic masses. | 2 |

| G(N..N) | Sum of geometrical distances between N..N. | 2 |

| H7m | H autocorrelation of lag 7/weighted by atomic masses. | 3 |

| RCON | Randic-type R matrix connectivity. | 3 |

| R1p+ | R maximal autocorrelation of lag 1/ weighted by atomic polarizabilities. | 3 |

| HOMT | HOMA (harmonic oscillator model of aromaticity index) total. | 4 |

a1.Topological; 2. Geometrical; 3. GETAWAY; 4. Aromaticity indices; 5. WHIM

n =3–6/compound

Fig. 9.

The calculated versus experimental activity data for the training (shown in squares), LOO cross-validation (shown in triangles) and test set runs (shown in diamonds) for the best NN11-3-1 QSAR model with VMAT2 ligands. The solid line represents a perfect correlation.

Table 11.

Stability Analysis of the Predictive Models Built from the Set of 104 Tetrabenazine and Lobeline Analogs

| No. | NN11-3-1 Model

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Train r2 (rmsd) | LOO q2 (rmsd) | Test r2 (rmsd) | |

| 1 | 0.91 (0.225) | 0.82 (0.316) | 0.93 (0.282) |

| 2 | 0.93 (0.207) | 0.83 (0.330) | 0.89 (0.341) |

| 3 | 0.93 (0.220) | 0.81 (0.358) | 0.92 (0.303) |

| 4 | 0.92 (0.235) | 0.84 (0.339) | 0.88 (0.353) |

| 5 | 0.93 (0.223) | 0.80 (0.370) | 0.94 (0.246) |

|

| |||

| Avg. | 0.92 (0.222) | 0.82 (0.343) | 0.91 (0.305) |

The developed models are expected to be valuable in the rational design of chemical modifications of the next-generation of VMAT2 ligands in order to identify the most likely candidates for synthesis and discovery of new lead compounds. One of the most important attributes of ANN is the ability to make predictions on new molecules with accuracy similar to that within the learning set. With a system that was theoretically validated to estimate binding affinity (Ki values) for known compounds with reasonable accuracy, we predicted the Ki values of various new (virtual) compounds designed by intuitive modification of the structures of the compounds in the ANN training set. Insights obtained from the theoretical predictions included the importance of the aromatic methoxy groups, and the optimal number of these groups in the molecule, which were determined to be a factor leading to high affinity for VMAT2. For example, for molecules with the general structure shown in Table 12, the IC50(exp.) values of four molecules (ID 1–4) that had been synthesized and evaluated experimentally (out of 104 new structures utilized for model generation), were inserted into the training set for the ANN to ‘learn’. Compounds 5–16 were novel molecules in which binding affinities were predicted by the generated models. According to the results predicted by the trained model, it was shown that when R0 = H, if R1, R2, R3 and R4 = H (compound 1), the computationally fitted binding affinity for the molecule was 4.90 μM. However, if one of the R1, R2, R3 and/or R4 groups was CH3O, the affinity of the compound was predicted to be improved, and if two of the R1, R2, R3 and R4 groups were CH3O, the affinity of the compound would be improved by one-order-of magnitude compared to the predicted binding affinity for compound 1. When R0 was OH, and R1, R2, R3 and R4 all were H (compound 9), the binding affinity of the molecule was predicted to be 4.62 μM. Compounds 10–12, which contain one aromatic methoxy substitutituent, are predicted to have their affinity improved similar to compounds 2–4. Compounds 13–16, which contain two aromatic methoxy substitituents, are predicted to exhibit a two-fold increase in binding affinity at VMAT2 compared to those of compounds 5–8. Compounds 6–9 were subsequently synthesized and their binding affinities were measured experimentally. The experimental results for compounds 7–9 shown in Table 12 are consistent with the computational predictions, but those for compound 6 are not. Clearly, the position of the methoxy group in the aromatic ring has a significant influence on Ki value; however, the model is not sensitive to this variable, since the information relating the importance of methoxy to binding activity was determined by topological descriptors. In this situation, the 3D effect of the methyloxy group was not reflected. However, in other cases the generated model does predict the difference in binding affinity of a molecule with different configuration. Table 13 shows that compounds 132–135, which constitute 4 different stereoisomers of the same structure, have different binding affinities for VMAT2. The experiment measurements for compounds 132 and 135 were consistent with theoretical predictions [106].

The accuracy of a QSAR model should be determined by statistical analysis with a much greater number (>500) of analogs than the limited number in our practical application of the currently generated models. For the VMAT2 binding assay, three compounds (6, 7 and 8, Table 12) were among those predicted to be lead compounds (i.e. binding affinity was predicted to be less than 1 μM) based on computational analysis, and were subsequently synthesized. Two of these compounds (7 and 8) had experimental binding affinities (0.62 μM and 0.56 μM, respectively) that were close to the original best leads (0.43 μM and 0.58 μM). Three compounds (132 and 135, Table 13, and 9, Table 12) were predicted to be inactive from computational models, and indeed were inactive when evaluated experimentally. These results indicate that the generated computational models have predictive value in the rational design of chemical modifications of VMAT2 ligands, and can be utilized to identify the most likely candidates for synthesis and discovery of new lead compounds. A larger data base needs be examined to form conclusions with statistical significance.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of compounds 86a–d, 87a, 87b, 88a, 88b and 89–93.

References

- 1.Erickson JD, Schafer MK, Bonner TI, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Distinct pharmacological properties and distribution in neurons and endocrine cells of isoforms of the human vesicular monoamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:5166–5171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson JD, Eiden L. Functional identification and molecular cloning of a human brain vesicle monoamine transporter. J Neurochem. 1993;61:2314–2317. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb07476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erickson JD, Eiden LE, Hoffman BJ. Expression cloning of a reserpine-sensitive vesicular monoamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:10993–10997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zheng G, Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. Vesicular monoamine transporter-2: Role as a novel target for drug development. AAPS J. 2006;8(4):E682–E692. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peter D, Jimenez J, Liu Y, Kim J, Edwards RH. The chromaffin granule and synaptic vesicle amine transporters differ in substrate recognition and sensitivity to inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7231–7237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peter D, Liu Y, Sternini C, de Giorgio R, Brecha N, Edwards RH. Differential expression of two vesicular monoamine transporters. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6179–6188. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-06179.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weihe E, Schafer MK, Erickson JD, Eiden LE, et al. Localization of vesicular monoamine transporter isoforms (VMAT1 and VMAT2) to endocrine cells neurons in rat. J Mol Neurosci. 1994;5:149–164. doi: 10.1007/BF02736730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krejci E, Gasnier B, Botton D, Isambert MF, Sagné C, Gagnon J, Massoulié J, Henry JP. Expression and regulation of the bovine vesicular monoamine transporter gene. FEBS Lett. 1993;335:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80432-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stern-Bach Y, Keen JN, Bejerano M, Steiner-Mordoch S, Wallach M, Findlay JB, Schuldiner S. Homology of a vesicular amine transporter to a gene conferring resistance to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9730–9733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell M, Shirvan A, Stern-Bach Y, Steiner-Mordoch S, Strasser JE, Dean GE, Schuldiner S. Cloning and functional expression of a tetrabenazine sensitive vesicular monoamine transporter from bovine chromaffin granules. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:16–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohoff FW, Dahl JP, Ferraro TN, Arnold SE, Gallinat J, Sander T, Berrettini WH. Variations in the vesicular mono-amine transporter 1 gene (VMAT1/SLC18A1) are associated with bipolar I disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2739–2747. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansson SR, Mezey E, Hoffman BJ. Ontogeny of vesicular monoamine transporter mRNAs VMAT1 and VMAT2, II. Expression in neural crest derivatives and their target sites in the rat. Dev Brain Res. 1998;110:159–174. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pletscher A. Effect of neuroleptics and other drugs on monoamine uptake by membranes of adrenal chromaffin granules. Br J Pharmacol. 1977;59:419–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1977.tb08395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darchen F, Scherman D, Henry JP. Reserpine binding to bovine chromaffin granule membranes. Mol Pharmacol. 1984;25:113–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scherman D, Henry JP. Radioligands of the vesicular monoamine transporter and their use as markers of monoamine storage vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:2395–2404. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry JP, Scherman D. Radioligands of the vesicular monoamine transporter and their use as markers of monoamine storage vesicles. Biochem Pharmacol. 1989;38:2395–2404. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(89)90082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scherman D, Jaudon P, Henry JP. Characterization of the monoamine carrier of chromaffin granule membrane by binding of [2-3H]dihydrotetrabenazine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:584–588. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.2.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amara SG, Sonders MS. Neurotransmitter transporters as molecular targets for addictive drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wise RA, Bozarth MA. A psychostimulant theory of addiction. Psychol Rev. 1987;94:469–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koob GF. Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;654:171–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Impact of psychostimulants on vesicular monoamine transporter function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;479:283–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riddle EL, Fleckenstein AE, Hanson GR. Role of monoamine transporters in mediating psychostimulant effects. AAPS J. 2005;7:E847–E851. doi: 10.1208/aapsj070481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown JM, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Regulation of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2: A novel mechanism for cocaine and other psychostimulants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:762–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sulzer D, Maidment NT, Rayport S. Amphetamine and other weak bases act to promote reverse transport of dopamine in ventral midbrain neurons. J Neurochem. 1993;60:527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sulzer D, Chem TK, Lau YY, Kristensen H, Rayport S, Ewing A. Amphetamine redistributes dopamine from synaptic vesicles to the cytosol and promotes reverse transport. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4102–4108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-05-04102.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson RG. Accumulation of biological amines into chromaffin granules: A model for hormone and neurotransmitter transport. Physiol Rev. 1988;68:232–307. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1988.68.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sulzer D, Rayport S. Amphetamine and other psychostimulants reduce pH gradients in midbrain dopaminergic neurons and chromaffin granules: A mechanism of action. Neuron. 1990;5:797–808. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90339-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takahashi N, Miner LL, Sora I, Ujike H, Revay RS, Kostic V, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Uhl GR. VMAT2 knockout mice: heterozygotes display reduced amphetamine-conditioned reward, enhanced amphetamine locomotion and enhanced MPTP toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9938–9943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, et al. Knockout of the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 gene results in neonatal dath and supersensitivity to cocaine and amphetamine. Neuron. 1997;19:1285–1296. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80419-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dwoskin LP, Crooks PA. A Novel mechanism of action and potential use for lobeline as a treatment for psychostimulant abuse. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00899-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peter D, Vu T, Edwards RH. Chimeric vesicular monoamine transporters identify structural domains that influence substrate affinity and sensitivity to tetrabenazine. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2979–2986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yelin R, Schuldiner S. Vesicular neurotransmitter transporters: Pharmacology, biochemistry, and molecular analysis. In: Reith M, editor. Neurotransmitter Transporters; Structure, Function, and Regulation. 2. Humana Press; Totowa: 2002. pp. 313–354. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merickel A, et al. Identification of residues involved in substrate recognition by a vesicular monoamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25798–25804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merickel A, Kaback HR, Edwards RH. Charged residues in transmembrane domains II and XI of a vesicular monoamine transporter form a chard pair that promotes high affinity substrate recognition. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5403–5408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.9.5403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sievert MK, Ruoho AE. Peptide mapping of the [125I]iodoazidoketanserin and [125I]2-N-[(3′-iodo-4′-azidophenyl)propionyl]tetrabenazine binding sites for the synaptic vesicle monoamine transporter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26049–26055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.26049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiriot DS, Ruoho AE. Mutagenesis and deriviatization of human vesicle monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) cysteines identifies transporter domains involved in tetrabenazine binding and substrate transport. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27304–27315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vardy E, Arkin IT, Gottschalk KE, Kaback HR, Schuldiner S. Structural conservation in the major facilitator superfamily as revealed by comparative modeling. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1982–1840. doi: 10.1110/ps.04657704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gros Y, Schuldiner S. Directed evolution reveals hidden properties of VMAT, a neurotransmitter transporter. J Biol Chem. 2009 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081216. Paper in Press: Manuscript M109.081216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millspaugh CF. American Medicinal Plants: An Illustrated and Descriptive Guide to Plants Indigenous to and Naturalized in the United States Which Are Used in Medicine. Dover; New York: 1974. Lobelia Inflata; pp. 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felpin FX, Lebreton J. History, chemistry and biology of alkaloids from Lobelia inflata. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:10127–10153. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wieland H. Alkaloids of the Lobelia plant. I. (Preliminary Communication.) Ber Dtsch Chem Ges. 1921;54B:1784–1788. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wieland H, Schopf C, Hermsen W. Lobelia Alkaloids. Ii. Ann Chem. 1925;444:40–68. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wieland H, Dragendorff O. Lobelia alkaloids. Iii. Constitution of the Lobelia alkaloids. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1929;473:83–101. [Google Scholar]