Abstract

Objective: To determine the current practice and plans for telemedicine at leading US neurology departments. Design and Setting: An electronic survey was sent to department chairs, administrators, or faculty involved in telemedicine at 47 neurology departments representing the top 50 hospitals as ranked by U.S. News and World Report. Main Outcome Measures: Current use, size, scope, reimbursement, and perceived quality of telemedicine services. Results: A total of 32 individuals from 30 departments responded (64% response rate). The primary respondents were neurology faculty (66%) and department chairs (22%). Of the responding departments, 60% (18 of 30) currently provide telemedicine and most (n = 12) had initiated services within the last 2 years. Two thirds of those not providing telemedicine plan to do so within a year. Departments provide services to patients in state, out of state, and internationally, but only 6 departments had more than 50 consultations in the last year. The principal applications were stroke (n = 14), movement disorders (n = 4), and neurocritical care (n = 3). Most departments (n = 12) received external funding for telemedicine services, but few departments (n = 3) received payment from insurers (eg, Medicare, Medicaid). Reimbursement (n = 21) was the most frequently identified barrier to implementing telemedicine services. The majority of respondents (n = 20) find telemedicine to be equivalent to in-person care. Conclusions: Over 85% of leading US neurology departments currently use or plan to implement telemedicine within the next year. Addressing reimbursement may allow for its broader application.

Keywords: telemedicine, telehealth, teleneurology

Introduction

Telemedicine is used to increase access for rural and underserved areas, allowing for the delivery of longitudinal and acute patient care, patient monitoring, and specialist consultations. Telemedicine is increasingly viewed as a means to improve health care delivery and the telemedicine industry is projected to be an $18 billion global market by 2015.1

Video telecommunications for the care of patients with neurological disease has been increasingly used to date. Teleneurology is most notably used to provide emergency consultation services for the prompt assessment and treatment of acute stroke.2,3 Applications have evolved to include mature networks for stroke care,4 video monitoring for inpatient neurocritical care,5 and longitudinal care for outpatient chronic neurological conditions such as epilepsy6 and Parkinson disease.7 Despite the expanded practices and successes of individual telemedicine programs, the prevalence of use and variety of applications for telemedicine within neurology is largely unknown. Recent literature has reviewed teleneurology and found an emergence in its evidence-based use.8–10 These studies, however, were largely limited to secondary analyses of previously published literature and were generally focused on stroke. To obtain a current and more detailed understanding of teleneurology, we conducted a cross-sectional survey to systematically assess the current practice, size, scope, quality, reimbursement, and plans for telemedicine at leading US neurology departments.

Methods

We surveyed neurology departments of the top 50 hospitals ranked by US News and World Report Best Hospitals for Neurology & Neurosurgery in 2010.11 For this survey, we defined telemedicine according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services as the “use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s health, where electronic communication is the use of interactive telecommunications equipment that includes, at a minimum, audio and video equipment permitting two-way, real time interactive communication between the patient, and the physician or practitioner at the distant site.”12 This definition excludes telephones, facsimile machines, electronic mail systems, traditional electronic medical records, and asynchronous store and forward of radiological or other imaging.

Participants

The University of Rochester institutional review board granted exemption. We identified contacts within each department using publicly available resources. We e-mailed a link to the electronic survey to department chairs, administrators, or other faculty involved in teleneurology for each department. In 3 cases, 1 department (eg, UCLA Department of Neurology) or “parent system” (eg, Partners HealthCare) covered 2 hospitals. Neurology department chairs, administrators, or other faculty were asked to complete the survey, or identify another faculty member from their department to complete the survey. We asked whether the respondents have knowledge of teleneurology plans or practices within their department prior to taking the survey. Reminder e-mails and telephone calls were made to departments that did not respond. Responses were collected between January 31, 2011, and July 6, 2011. If more than 1 response was collected from a single department, we accepted the greater value of 2 responses for questions regarding the size and scope of programs. Responses were assessed individually for questions on perceived quality of telemedicine and challenges to implementing services.

Survey Instrument

Survey questions were reviewed and edited based on comments from senior department faculty and neurologists involved in telemedicine. The survey contained 24 questions (supplemental document), although the number of questions answered by any 1 respondent may vary. For many questions, respondents were asked to choose from a multiple-choice list, some of which could accommodate multiple answers and comments. All questions were optional. Questions regarding current practice and plans, size, scope, and reimbursement pertain to the departments’ use of telemedicine over the previous year. In addition, we asked respondents about their perception of telemedicine quality (inferior, equivalent, superior to in-person care) and barriers to implementing services.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison of differences between respondents and nonresponding departments in the size of the primary hospital, size of geographical area, and number of faculty neurologists was performed using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, while medical center tax status was compared using Fisher exact test. For nonresponding departments, we determined the number of faculty neurologists using department Web sites. For total staffed beds and tax status, we used figures from the American Hospital Association.13 To determine the size of geographical area, we aligned hospital location with metropolitan statistical area and used 2009 population estimates from the US Census Bureau.14 Differences between respondents from departments using telemedicine and those that do not use telemedicine were evaluated using Fisher exact test for the telemedicine challenges identified (or reasons for not using telemedicine) and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for the comparison of telemedicine to in-person care. Analyses were performed using STATA software, version 12.0. All tests were conducted at the 2-sided significance level of 5%.

Results

Respondents

Of the 47 neurology departments surveyed, 30 responded (64% response rate) and 32 faculty responses were collected (2 institutions provided 2 responses). The majority of respondents were faculty neurologists and department chairs (Table 1). The characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents did not differ by size of hospital (P = .58), geographical area (P = .49), faculty size (P = .12), or taxpayer status (P = .07).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Survey Respondents and Nonrespondents

| Survey Respondents (%) n = 30 | Survey Nonrespondents (%) n = 17 | |

|---|---|---|

| Size of primary hospital (beds) | ||

| <100 | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| 100-299 | 1 (3) | 3 (18) |

| 300-499 | 5 (17) | 3 (18) |

| 500-1000 | 19 (63) | 6 (35) |

| >1000 | 5 (17) | 4 (24) |

| Mean (SD) | 808 (411) | 747 (499) |

| Size of geographical area (MSA in millions) | ||

| <1 | 6 (20) | 3 (18) |

| 1-3 | 8 (27) | 4 (24) |

| 3-5 | 6 (20) | 3 (18) |

| 5-8 | 6 (20) | 3 (18) |

| >8 | 4 (13) | 4 (24) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (3.5) | 5.2 (4.1) |

| Neurology faculty size | ||

| <10 | 0 (0) | 3 (18) |

| 10-25 | 3 (10) | 3 (18) |

| 26-50 | 14 (47) | 7 (41) |

| >50 | 14 (43) | 4 (24) |

| Mean (SD) | 54 (27) | 39 (28) |

| Hospital/Medical center tax status | ||

| Public | 9 (30) | 1 (6) |

| Private | 21 (70) | 16 (94) |

| Department position (n = 32)a | ||

| Department chair | 7 (22) | NA |

| Faculty neurologist | 21 (66) | NA |

| Department administrator | 2 (6) | NA |

| Other | 2 (6) | NA |

Abbreviations: MSA, metropolitan statistical area; SD, standard deviation.

a Two institutions provided 2 responses. Department chair includes former chair. Other includes joint appointments (psychiatry) and unspecified.

Current Practice

Of the 30 responding departments, 60% provide telemedicine. There were no differences in the size of hospital, geographical area, faculty, or taxpayer status between departments providing telemedicine and those not providing this service, although our study was not powered to detect small differences. Most departments that provide teleneurology services began doing so within the last 2 years, and most of the remaining departments plan to provide such services within a year. The principal applications were acute stroke, movement disorders, and neurocritical care (Table 2). Most departments (n = 16) used telemedicine for 1-time consultations, including specialty consults and second opinions, and a minority (n = 7) used teleneurology to provide longitudinal care.

Table 2.

Telemedicine Practice, Plans, Size, Scope, and Reimbursement at Leading US Neurology Departments, 2010a

| Survey Questions and Responses | Departments (%) | Survey Questions and Responses | Departments (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telemedicine use (n=30) | Plans to use within a year (n=12) | ||

| Yes | 18 (60) | Yes | 8 (67) |

| No | 12 (40) | No | 4 (33) |

| Years of use (n=18) | Applications (n=18) | ||

| ≤1 year | 8 (44) | Stroke | 14 (78) |

| 2 years | 4 (22) | Movement Disorders | 4 (22) |

| 3 years | 2 (11) | Neurocritical Care | 3 (17) |

| 4 years | 0 (0) | Cognitive Disorders | 2 (11) |

| 5 years | 1 (6) | Epilepsy | 1 (6) |

| >5 years | 3 (17) | Neuroimmunology | 1 (6) |

| Visits in past year (n=18) | Patients in past year (n=18) | ||

| 1-10 visits | 7 (39) | 1-5 patients | 4 (22) |

| 11-100 visits | 6 (33) | 6-25 patients | 3 (17) |

| 101-500 visits | 3 (17) | 26-100 patients | 4 (22) |

| >500 visits | 2 (11) | >100 patients | 5 (28) |

| Providers (n=18) | No Response | 2 (11) | |

| 1 provider | 2 (11) | Distance of care (n=18) | |

| 2-3 providers | 3 (17) | 1-10 miles & in-state | 9 (53) |

| 4-10 providers | 12 (67) | 11-100 miles & in-state | 10 (59) |

| >10 providers | 1 (6) | >100 miles & in-state | 8 (47) |

| Originating sites (n=18)b | Out-of-state | 6 (35) | |

| Emergency department | 13 (72) | International | 1 (6) |

| Hospital - inpatient | 9 (50) | Funding for telemedicine (n=18) | |

| Outpatient clinic | 4 (22) | Payment from originating site | 5 (28) |

| Long term care facility | 2 (11) | Federal or state funding | 4 (22) |

| Prison | 2 (11) | Foundation or philanthropy | 3 (17) |

| Patient residence | 2 (11) | Insurance providers | 3 (17) |

aNumber of respondents for any single question may vary. For originating sites, applications, distance of care, and funding for telemedicine respondents could select multiple answers, and therefore, not all items sum to 100%.

bThe originating site is the site which receives telemedicine.

As detailed in Table 2, the majority of departments using telemedicine have 4 to 10 telemedicine providers, 100 patients or less, and 100 visits or less in the past year.

The primary sites receiving care by telemedicine were emergency departments (EDs), hospitals, and outpatient clinics (Table 2). Of neurology departments reporting service to EDs (n = 13), 7 provide services within their own institution’s ED and 12 provide service to EDs outside of their institution (from 1 to more than 40 EDs). Most departments used telemedicine to reach patients within their state, and the distance of communication between department and patient ranged from 1 to 10 miles (53%) to greater than 100 miles (47%) within state boarders. Some provide care out of state (from 1 to 3 states) and 1 department reported international delivery of care.

Technology

Departments used a wide variety of telemedicine technology. The most frequently used were InTouch Health (n = 7), Polycom (n = 5), and Tandberg (n = 4).

Quality

For quality measures, twenty respondents (63%) rated telemedicine as equivalent to in-person care, 10 (31%) rated telemedicine as inferior, and 1 (3%) as superior. The opinion did not differ between respondents at departments that use telemedicine and those that do not (P = .32). Six respondents commented that their rating of telemedicine as equivalent to in-person care specifically pertained to applications for acute stroke, neurovascular, or neurological emergencies. Those that indicated telemedicine was inferior to in-person care remarked that it was due to a loss of personal touch, inability to perform a complete physical examination, dependency on another person’s examination, or difficulty with hearing and visually impaired patients.

Challenges

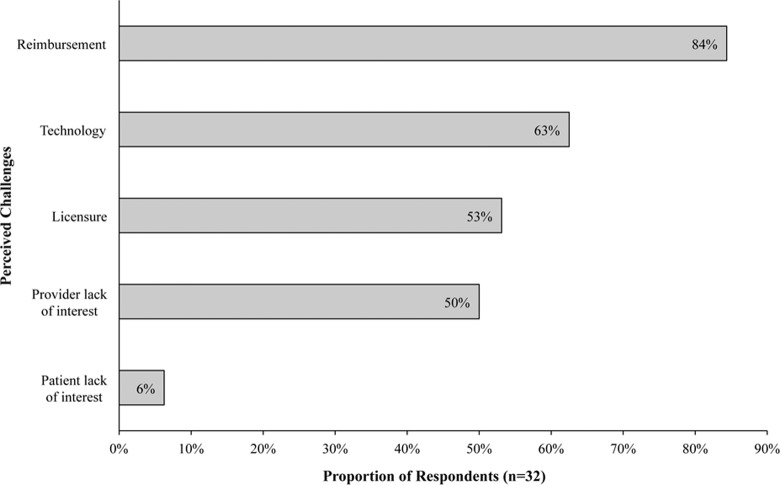

The most frequently identified challenges to implementing telemedicine by faculty respondents were reimbursement, technology, and licensure issues (Figure 1). No significant differences in perceived challenges were found between respondents at departments that use telemedicine and those that do not.

Figure 1.

Challenges to implementing telemedicine as perceived by survey respondents at leading US neurology departments, 2010.* *Respondents had the option to select multiple and, therefore, responses do not sum to 100%.

Discussion

More than 85% of leading US neurology departments use or plan to use telemedicine within the next year. Currently, telestroke is the most common application of telemedicine,2–4 however other applications are developing. Neurology departments are using telemedicine to provide neurocritical care to remotely monitor patients with brain trauma, intracerebral hemorrhage, and other conditions.5 Some also use telemedicine for the care of chronic neurological conditions; applications that can improve access and provide continuity for patients who are homebound or live in rural communities distant from providers.15

Most teleneurology programs are currently small in size and modest in geographic scope. Departments have a limited number of neurologists providing care, patients receiving care, and total number of visits, which may be due to the recent introduction of services for many departments. At least 2 departments are more mature and provide over 500 visits per year. Currently, services are primarily provided to hospitals and EDs. Patients also receive care via telemedicine in outpatient clinics, long-term care facilities, prisons, and their own residences. Most programs are limited in their geographical scope to their home state, which may be due to licensure laws that require a physician to be licensed in the state in which the patient is located.16

More than half of department providers receive external funding, and only 17% receive reimbursement from insurers including Medicare, Medicaid, and private payors, which is similar to other recent reports.17

In this survey, reimbursement was frequently identified as one of the greatest challenges to the adoption of telemedicine. Restrictions on Medicare reimbursement for physicians at distant sites make qualification for payment difficult. Beyond the required 2-way interactive telecommunications, telemedicine visits must meet specifications on location (ie, Health Professional Shortage Areas), provide care to an appropriate originating site (eg, critical access hospital), and deliver eligible medical services.18 Medicaid and private insurance reimbursement is also subject to specifications and is largely variable by payor and state.19,20 At least 12 state legislatures have adopted mandates for telemedicine reimbursement.21 Still, large gaps and inconsistencies in reimbursement leave telemedicine services underfunded. Additional data on quality of care and outcomes of telemedicine programs could be helpful toward driving changes in reimbursement policy.

Recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services proposed to change the way additional telemedicine services are covered by examining “clinical benefit” rather than equivalence to in-person services.22 Insurance coverage for telemedicine may expand substantially under this proposal, but this remains speculative given the financial pressures on federal and state governments and little research on the effectiveness of teleneurology in the United States, with the exception of telestroke.23,24

Other funding sources for telemedicine programs in neurology include payment from sites, government grants, and funding from foundations or philanthropy. Some community hospitals or other originating sites receiving telemedicine (eg, prisons) experience reduced costs associated with patient transportation and staff time, as staff are often required to accompany patients on visits. These sites may choose to pay departments directly for the value of services received. Nevertheless, one third of department providers do not receive any external funding and rely on department or home institution funds to support their programs. To date, no dominant reimbursement model has evolved for telemedicine.

The absence of third-party reimbursement may be an opportunity. Reimbursement from insurers may stifle innovation and limit the scope of care provided and received.25,26 In the absence of reimbursement, patients and providers can develop alternative payment models, such as monthly or annual fees for services, that could reflect the transportation and time savings for patients. These payments could vary depending on the scope of services desired by the patient and offered by the physician. In the inpatient setting, smaller hospitals may want to contract with larger ones for access to specialty services (eg, acute stroke care) that would otherwise be unavailable to smaller, underserved communities.

Telemedicine is seen as valuable to providers and patients alike. Most of those surveyed rate telemedicine as equivalent to in-person care, appreciating the “convenience” and “improved outcomes” enabled by telemedicine. Patients, including the chronically ill, are open to remote monitoring and virtual medical visits, and the use of technology and social media is growing among the elderly individuals.27 While both physicians and patients realize the benefits, insurers have been slow to embrace telemedicine. Given the current state of reimbursement, novel payment models and continued creative application of technology are needed to increase access and advance care for individuals with neurological disorders.

Our study was restricted to neurology departments at the top 50 hospitals in neurology and neurosurgery in 2010. The results may not be generalizable to smaller departments due to large faculty size, large hospital size, and urban location of the hospitals surveyed. For smaller hospitals, views on the application and value of telemedicine may differ. Given the limited size of our survey the study was not powered to detect small differences between respondents providing telemedicine and those not providing this service. Importantly, our survey focuses on telemedicine services provided rather than those received by departments and hospitals. Patients and providers at originating sites receiving telemedicine may view the services provided differently. Additionally, telemedicine providers may have a bias of perceiving the service as positive compared to traditional in-person care. However, the focus of the study was on prevalence and details of telemedicine use. In this respect, our study is limited by the possibility that some respondents may have had incomplete information on department activities and, therefore, could have under- or overreported telemedicine use. We attempted to control for this by asking that only those with knowledge of activities and plans in telemedicine respond to the survey. Respondents included a variety of individuals across departments (eg, department chairs, administrators, and faculty) and therefore the differences among respondents may limit the reliability of the study. Respondents using telemedicine may also have a vested interest and could be more likely to respond, resulting in higher estimates of telemedicine use. Despite these limitations, the survey provides a timely estimate of the current practice, size, scope, quality, reimbursement, and plans for telemedicine at leading departments.

Although leading neurology departments increasingly use telemedicine, the size of current programs and geographic scope of services provided are limited. Applications of telemedicine in neurology have the potential to expand based on the benefits to patients and providers. While telemedicine increases access to care and creates value for its users, insufficient reimbursement from insurers prevents more widespread use. In the absence of reimbursement, novel payment models are needed to continue growth in telemedicine for the care of neurological disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Robert G. Holloway, MD, MPH, Professor of Neurology at the University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry for his guidance in survey design.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The authors B. P. George and E. R. Dorsey were involved with study conception and design;B. P. George, N. J. Scoglio, J. I. Reminick, B. Rajan, A. Seidmann, K. M. Biglan, and E. R. Dorsey with survey design; C.A. Beck and B. P. George with statistical analysis; B. P. George with drafting of the original manuscript; and B. P. George, N. J. Scoglio, J. I. Reminick, B. Rajan, C. A. Beck, A. Seidmann, K. M. Biglan, and E. R. Dorsey with critical review and critique of the manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Dr Biglan and Dr Dorsey use Polycom technology to provide telemedicine services. Mr George, Mr Scoglio, Mr Reminick, Mr Rajan, Dr Beck, and Dr Seidmann report no conflicting interests.

Funding: This study was supported by the American Academy of Neurology Medical Student Summer Research Scholarship (Mr George) and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Physician Faculty Scholars Program (Dr Dorsey).

References

- 1. Telemedicine: A Global Strategic Business Report San Jose, CA: Global Industry Analysts, Inc; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schwamm LH, Rosenthal ES, Hirshberg A, et al. Virtual TeleStroke support for the emergency department evaluation of acute stroke. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(11):1193–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meyer BC, Lyden PD, Al-Khoury L, et al. Prospective reliability of the STRokE DOC wireless/site independent telemedicine system. Neurology. 2005;64(6):1058–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hess DC, Wang S, Hamilton W, et al. REACH: clinical feasibility of a rural telestroke network. Stroke. 2005;36(9):2018–2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vespa PM. Multimodality monitoring and telemonitoring in neurocritical care: from microdialysis to robotic telepresence. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2005;11(2):133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ahmed SN, Mann C, Sinclair DB, et al. Feasibility of epilepsy follow-up care through telemedicine: a pilot study on the patient's perspective. Epilepsia. 2008;49(4):573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dorsey ER, Deuel LM, Voss TS, et al. Increasing access to specialty care: a pilot, randomized controlled trial of telemedicine for Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(11):1652–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Demaerschalk BM, Miley ML, Kiernan TE, et al. Stroke telemedicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stone K. NerveCenter: Telestroke comes of age, but telemedicine stalls overall. Ann Neurol. 2011;69(2): A12–A14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agarwal S, Warburton EA. Teleneurology: is it really at a distance? J Neurol. 2011;258(6):971–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. News Best Hospitals: Neurology & Neurosurgery, author. http://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals/rankings/neurology-and-neurosurgery Accessed September 30, 2010.

- 12.Telemedicine for Medicare, author. http://www.medicare.org/health-information/telemedicine.html Accessed February 14, 2012.

- 13. American Hospital Association Data Washington, DC: American Hosptial Association; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Area Estimates: Annual Estimates of the Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009. http://www.census.gov/popest/metro/CBSA-est2009-annual.html Accessed February 20, 2012

- 15. Woods KF, Kutlar A, Johnson JA, et al. Sickle cell telemedicine and standard clinical encounters: a comparison of patient satisfaction. Telemed J. 1999;5(4):349–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cwiek MA, Rafiq A, Qamar A, Tobey C, Merrell RC. Telemedicine licensure in the United States: the need for a cooperative regional approach. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(2):141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.http://strokeforum.doh.wa.gov/links/RTI_TelestrokeSurvey_Report2010.pdf Regional Telestroke Initiative: 2010 Telestroke Survey; 2010. Accessed February 24, 2011.

- 18. Demaerschalk BM. Telestrokologists: treating stroke patients here, there, and everywhere with telemedicine. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(5):477–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naditz A. Medicare's and Medicaid's new reimbursement policies for telemedicine. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14(1):21–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitten P, Buis L. Private payer reimbursement for telemedicine services in the United States. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(1):15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silva C. Telemedicine Coverage Now Mandated in Virginia. http://www.ama-assn.org/amednews/2010/04/19/gvsb0419.htm Accessed February 20, 2012

- 22. Medicare Program; Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B for CY 2012; 2011:76 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2011-07-19/pdf/2011-16972.pdf Accessed February 20, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nelson RE, Saltzman GM, Skalabrin EJ, Demaerschalk BM, Majersik JJ. The cost-effectiveness of telestroke in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2011;77(17):1590–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwamm LH, Holloway RG, Amarenco P, et al. A review of the evidence for the use of telemedicine within stroke systems of care: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2616–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raab GG, Parr DH. From medical invention to clinical practice: the reimbursement challenge facing new device procedures and technology—part 2: coverage. J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3(10):772–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carrier E, Pham HH, Rich E. Comparative Effectiveness Research and Innovation: Policy Options to Foster Medical Advances. National Institute for Healthcare Reform: Policy Analysis 2009; http://www.nihcr.org/Comparative---Effectiveness---Research.pdf Accessed February 20, 2012

- 27. Madden M. Older Adults and Social Media: Social Networking Use Among Those Ages 50 and Older Nearly Doubled Over the Past Year. http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Older-Adults-and-Social-Media.aspx Assessed February 20, 2012