Abstract

There is tremendous interest in different approaches to slow the rise in US per capita health spending. One approach is to publicly report on a provider’s costs (also called efficiency, resource use, or value measures) with the hope that consumers will select lower cost providers and thereby encourage providers to decrease spending. In this paper, we explain why we believe many current cost profiling efforts are unlikely to have this intended effect. We then suggest changes to content and design to increase the intended consumer and provider response to publicly reported cost measures.

Background

The passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has intensified the focus on approaches to decreasing health care costs. Jonathan Gruber, a health care economist, has described the ACA as the completion of the first round of health reform which he termed the coverage round.(1) We have now entered what he calls the second round, the cost-reduction round. The ACA takes the general approach of “letting a thousand flowers bloom,” testing a myriad of approaches to lower costs.

One of these approaches to reducing costs is the measurement and public reporting of cost measures. Public reporting of costs is currently conducted by Medicare, the states, and the private sector. The Affordable Care Act will accelerate these efforts by mandating public reporting of cost measures for physicians and hospitals as a component of value-based purchasing programs. The hope is that patients will use these measures as one of many considerations when they choose their providers. As patients begin to switch to lower-cost providers, theoretically higher-cost providers will lower their costs to remain competitive.

In this paper, we explore the feasibility of this model. We first focus on concerns that consumers might not respond to cost measures in the manner policymakers expect and ways to overcome these potential pitfalls. We then discuss whether it is even necessary for consumers to respond to cost measures given that providers may respond due to reputational concerns. We conclude by providing recommendations for how to publicly report cost measures.

Clarifications and caveats

Before turning to the main purpose of the paper, we want to clarify terminology and add some necessary caveats. For the purposes of this paper we consider cost measures to include the wide variety of measures that are publicly reported for the purpose of decreasing spending including “cost,” “resource use,” “efficiency,” or related concepts. In Exhibit 1, we provide some illustrative examples which demonstrate the variety of types of measures and types of providers (i.e. hospitals, physicians, nursing homes) profiled. Often this cost data is presented in isolation from quality information. In many cases, the measure used in the profile is only the reimbursement to the provider and therefore does not equal “total costs” which are a function of this reimbursement and utilization.

EXHIBIT 1. Illustrative examples of publicly reported cost measures (cost measure bolded).

| Type of Provider? |

Where? | What cost measure captures | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aetna’s Aexcel Network (36) |

Physicians | National | In their provider directory, Aetna places stars next to physicians who on average are lower cost than their peers based on a cost profile. Cost profiles are generated based on the costs of treating an episode of care (i.e., treating a particular disease or acute event). The focus of this program is on physicians in 12 specialties. To meet designation status, the physicians must also meet a quality threshold. |

| Hospital Compare(37) |

Hospital | National | On this website run by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, a person selects a specific condition (e.g., pneumonia) and a geographic region. The website then displays the volume of cases and Median Medicare reimbursement for related categories of hospitalizations such (e.g. “Simple pneumonia and pleurisy (DRG 193)”) for hospitals in that region. |

| Quality Quest (38) | Physician clinic |

Illinois | This website targets consumers. A consumer selects one of 7 different kinds of providers (e.g. behavioral health, primary care) and one of 19 counties. For each provider in the county, the website displays the percent of prescriptions that are generic and how that compares to a “high performer.” |

| NJ Hospital Price Compare (39) |

Hospital | New Jersey |

The goal of this website is to provide consumers an ability to compare charges at New Jersey’s acute care hospitals. A consumer selects a hospital and diagnosis (e.g., “DRG 552 (Medical back problems w/o MCC”). The website displays the average length of stay and charges for the hospital compared to several sets of comparison hospitals such as “hospitals with similar licensed beds” |

| Nursing Home Guide. (40) |

Nursing Homes |

Florida | Website users select a region and then a specific nursing home. Each nursing home has a webpage which provides a range of information including quality scores and lowest daily charge for the nursing home. |

SOURCE: Author’s analysis

While we do not address them in this paper, we acknowledge the numerous methodological and operational issues with cost measures that have been noted in our prior work.(9, 10) Following our recommendations on how to present cost measures without addressing concerns about the validity and reliability of the measures is problematic. It might lead to anger and distrust among providers and perceptions that the measures are not fair.(11) Providers may respond by avoiding patients they perceive as high cost such as minorities, wealthy patients who “demand too much”, or patients with multiple co-morbidities if they do not believe these factors are incorporated into the cost measures.

How will public reporting of cost measures translate to lower costs?

Selection pathway – driving lower costs through consumers

Public reporting of cost measures to a consumer audience is built on the expectation that consumers will use that cost information to choose their provider. Theoretically, patients will preferentially choose lower-cost providers, higher-cost providers will lose market share and will be motivated to decrease their costs in response to these competitive pressures. This has been termed the “selection” pathway by Don Berwick; providers will lower their costs due to real or anticipated loss of market share.(14, 15)

This pathway is complementary to consumer-directed health care. In consumer-directed health care there is an expectation that patients will bear a greater burden of costs (“skin in the game”) and therefore will have greater interest in selecting low-cost high-quality providers.(16) We discuss later the importance of financial incentives and quality information.

Concerns with the selection pathway

There are several reasons why current cost measures may not achieve the aims of the selection pathway. First, regardless of the costs of the provider they select, most people in the US, including those on Medicare,(17) still pay no copayment or a fixed co-payment for individual services and have a cap on their annual out-of-pocket spending. Even beneficiaries with high-deductible plans quickly reach full coverage in the event of a significant health care problem due to the high cost of most services. Therefore, the majority of consumers have no practical interest in these data. It is notable that consumers typically express interest in quality information, yet have been slow to use current quality report cards to inform their choice of providers.(18, 19) With the addition of cost measures to public reports, the challenges are likely to be greater.

Second, the cost information that is directly relevant to consumers is their out-of-pocket costs. Current cost measures typically do not provide consumers with this key information. Instead, currently used measures typically include total costs from the perspective of a third party payer. While the total cost of care contributes to increasing health costs – and therefore, higher premiums for consumers – it is unlikely that most consumers will change their behavior based on these considerations. The link between higher personal medical costs and ones income is indirect.

Third, the evidence to date suggests that many consumers believe that more care is better and that higher-cost providers are higher-quality providers.(20-22) This raises the possibility that public reporting of cost measures might have the perverse impact of increasing costs. Consumers might interpret “lower cost” as evidence of scrimping on care and therefore low quality. This association between costs and quality is powerful. Consumers know that in most aspects of their life higher priced goods and services are often better than lower cost goods and services. In one recent study two groups of patients were randomized to receive the same drug, but in one group the pill was labeled $2.50 per pill while in the other group the pill was labeled as $0.10 per pill. The group that received the more expensive pill was much more likely to report pain reduction.(23) Costs may be sensibly viewed as a proxy for quality. Therefore, the potential hazard of only publicly reporting cost data is that consumers will use the cost information to select higher-cost providers. Overcoming the “more is better” belief and communicating that lower cost is not compromising on quality are key challenges in publicly reporting cost data.

Fourth, consumers often cannot understand cost measures and therefore may not trust the reports. Prior work on publicly reported quality information highlights the cognitive burden of assimilating this information or basic misunderstanding of whether a high or low score is preferable.(15, 24) These issues are also evident with cost measures. For example, it would be difficult for the typical consumer to interpret whether a shorter length of stay in the hospital is a good thing. Indeed, a consumer might interpret higher length of stay as a positive attribute because that means the hospital will not push them out of the hospital. Beyond comprehension, there are concerns with awareness and trust. It is likely that consumers will be skeptical of any cost information that comes from a health plan or employer. One study on tiered physician networks (which is based both on quality and costs) found that few consumers were aware of the tiering and almost two-thirds did not trust the information which was provided by a health plan.(25)

Lastly, the measures must be directed to the decisions consumers actually make. Medicare publicly reports average reimbursement to a hospital for a myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack. Yet, a hospitalization for a myocardial infarction (and many other emergent conditions) is dictated by the driver of the ambulance, not the patient. Therefore it is not feasible for a patient to use this information.

To summarize, we believe that in their current form and in the absence of any financial incentives, it is unlikely that public reporting of provider costs will drive consumers to selectively choose lower-cost providers.

Potential ways to make the selection pathway viable

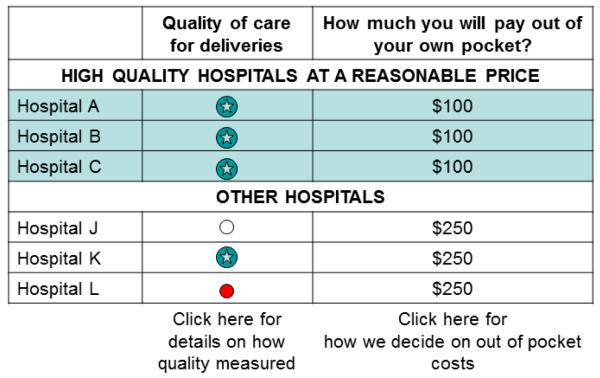

If a policymaker wants to pursue the selection pathway, there are four key changes that must be made to current reporting to make it more likely that consumers will respond to cost measures: (1) focus on choices that are relevant to consumers, (2) present information in a manner that patients can easily process, (3) tie cost measures to quality measures, (4) use consumer financial incentives. In Exhibit 2, we illustrate these recommendations in a theoretical report card.

EXHIBIT 2. Illustration of How to Implement the Consumer-Pathway: Report Card for Maternity Hospitals.

SOURCE: Author’s views

Footnote: In this Exhibit, we illustrate our recommendations on how public reports can better engage consumers. We focus on choice of a maternity hospitals, an area of health care where patients are motivated and have the time to make a choice. We present the key piece of information that consumers want, their out-of-pocket costs. We also differentiate between the high-value providers by putting them in a separate section and highlight them in green. Because we recognize consumers may distrust the cost information and link higher costs with higher quality, we made quality the first column. We do not even list the cost metrics used to distinguish between the two tiers (that information is available using the question symbol for only those that want more data). In some sense we are creating different depths of data, the initial report for the “1 minute reader” while the more in depth information is available for the reader with greater interest.

It is important to target the provider choices made most often by consumers such as the choice of a primary care physician, an obstetrician/maternity hospital, or the surgeon for an elective procedure such as joint replacement. In many other clinical situations, a patient’s choice of provider is heavily influenced by their physician. For example, Medicare patients often accept the specialty physicians associated with that primary care physician and the hospital to which these physicians typically admit consumers.(26). With emergent conditions or procedures (e.g. hip fracture, heart attack), consumers cannot plausibly respond to public reports of costs. Another good fit for public reporting of costs are services which patients are unlikely to perceive quality differences. With these services, patients will be more sensitive to financial incentives. Examples of such services include a blood test for complete blood count or an influenza vaccine.

The type of measures and presentation of the information are also critical. The measure most relevant and easily interpreted by consumers is their out-of-pocket costs. Ideally, consumers would be presented with an estimate of their total expected costs over a period of time or episode of treatment, not simply with their payment for the first physician visit or diagnostic test. Given the current complex variation in benefit designs, it may be difficult to publicly report a single co-payment amount and it may be necessary to report ranges of co-payments ($50-150 vs.$200-400) or to use qualitative terms (“lowest co-payment” vs. “highest co-payment”). A personalized estimate would require information on individual insurance benefits, as well as expected utilization over the entire episode of treatment (e.g. all care related to pneumonia), and provider payment rates. Given the current complex variation in benefit designs, it may be difficult to publicly report a single co-payment amount and it may be necessary to report ranges of co-payments ($50-150 vs.$200-400) or to use qualitative terms (“lowest co-payment” vs. “highest co-payment”).

Research on public reporting of quality measures highlights the importance of simplicity.(24, 27) Consumers can more easily process information when an overall summary is provided [One caveat is that a single summary measures might increase distrust. To address this issue it is useful to have more detailed information (“click here for more details”)] available for those consumers who desire that information. They are also more likely to respond if it is easy to identify the outlier providers; this can be done by putting the outlier physicians at the top of the report, rank-ordering providers, or highlighting them in some other manner. The use of easy to interpret symbols, as opposed to numerical scores, is also easier for consumers to interpret. Equally important is the language used. While “high-value” or “efficient” might seem intuitive, we believe consumers do not understand or find these terms salient. We emphasize the need to do consumer testing with the language used in a public report card.

Another key is that cost measures should be tied to quality measures.(20) The goal is to neutralize the typical consumer’s association between high costs and higher quality. If the cost and quality data are displayed side-by-side or the cost data is displayed within quality tiers, then consumers might be less concerned that being lower cost translates into lower quality. One idea is to combine cost and quality data into a single value metric. Our concern with that approach is that the idea of value may not be salient or trusted by consumers currently.

Lastly, and maybe most importantly, we believe there must be a financial incentive for patients to switch providers. The limited available evidence suggests that patients will switch their providers when given a financial incentive.(11, 28) Financial incentives could be created through changes to benefit design such as tiered networks with higher copayments for high-cost providers or narrow networks that exclude high-cost providers. One study found that when their physician was excluded from their health plan’s network, 81% of patients stopped seeing that physician.(28) The visit copayment difference for patients between an out-of-network physician and an in-network physician was $50-60 versus $15. Evidence of provider switching has also been seen in tiered provider networks where a patient must pay a higher premium or a higher co-payment to see designated providers. In the tiered network in the Buyers Health Care Action Group purchasing initiative research shows that patients were responsive to the cost differences.(11) This is echoed by the self-reported experience of health plans with tiered provider plans.(29) This approach, combining cost and quality reporting with a financial incentive such as a different copayment, could also address the concern that simple cost-sharing is a blunt instrument that is equally likely to discourage both high-value and low-value care.(30)

In summary, to encourage consumers to respond to publicly-reported cost measures (the selection pathway), it is important for the cost measures to focus on consumer-relevant choices, be easy to interpret, tied to quality information, and/or linked to a consumer’s out-of-pocket costs. Because of the limited evidence in this area, future empirical studies will be necessary to test the effect of improved cost measures.

The alternative “reputational” pathway – driving lower costs through direct response of providers

In the reputational pathway the goal of public reporting is to provide transparency (“sunlight is the best disinfectant”) and to directly drive a provider response.(14)

There are two potential reasons why providers might respond to such publicly reported measures. The first is that by learning that they are labeled “high cost” or “low value” a provider maybe inherently motivated to change and lower their costs.(14) This idea has been promoted in recent definitions of physician professionalism that include being good stewards of resources.(31) The second is that providers will respond primarily to protect their public image.(15, 32) Prior research has argued that the latter is more likely to drive a response and therefore we have labeled it the “reputation” pathway.

To our knowledge, there are no data on whether providers will respond to publicly-reported cost measures. We only can extrapolate from research examining the provider response to public reporting of quality measures. One prominent example is CMS’s Hospital Compare initiative, where there has been steady improvement in hospital performance on the publicly reported measures despite the absence of any clear consumer response.(33) Provider response to quality measures appears to be driven primarily by concerns about reputation.(32, 34) Hospitals that receive private and confidential reports do not improve on their care to the same degree to those where it was publicly reported. However, for the reputational pathway to work, those being reported upon must think that relevant audiences (e.g. hospital board members, local politicians, competitors) are watching and care. This means the reports must be salient and comprehensible to these relevant audiences.

Will publicly reporting cost measures drive the same provider response? Like many issues related to publicly reporting cost measures, we do not know. On one hand, if high costs are interpreted as being “wasteful” then providers will worry it hurts their image. On the other hand, unlike in the area of quality where providers have an intrinsic desire to provide higher quality care, it is unclear whether a provider has an intrinsic desire to be lower cost. Being publicly labeled as a “high cost” or “low value” provider is unlikely to have the same negative reputational impact as being labeled as low quality. Indeed providers might recognize that among a large fraction of the populace higher cost with quality and therefore believe that being labeled as high cost actually enhances their public reputation. We also must be concerned about the perverse impact on low-cost providers. Providers labeled low cost might worry about the negative reputational effect or see the opportunity to increase revenue among their existing patient population. In response, they might try and increase their costs.

It is important to emphasize that even with the reputation pathway, public reporting of the measures is important. Even though in this pathway consumers do not change providers, providers must worry that some consumers and their peers view them as a poor performer. Therefore, the measures should be accessible and understandable to consumers if the measures are going to impact public image. Ideally, the cost measures will have a clear association with quality. Examples include rehospitalizations, costs associated with potentially avoidable complications or “never” events, or use of high-cost high-radiation risk imaging for back pain. All of these might be viewed by providers as potentially avoidable costs that clearly result from poor-quality health care.

Why does the potential pathway matter?

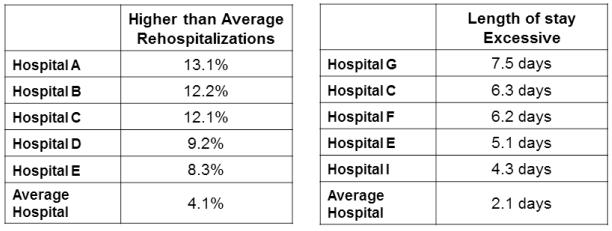

The pathway, selection or reputational, by which one believes public reporting of cost measures translates to lower costs has clear practical implications. It can impact which conditions to focus on, which measures are chosen, and how the information is presented. To make our recommendations concrete, we present in Exhibits 2 and 3, cost report cards that focus on the selection pathway and reputational pathway respectively. The exhibits are presented to illustrate the key concepts and we have not been tested with consumers or providers.

EXHIBIT 3. Illustration of How to Implement Reputation Pathway: Report Card for Myocardial Infarction.

Source: Author’s views

Footnote: In this Exhibit, we illustrate our recommendations on how public reports can better motivate providers to focus on value. We focus on rehospitalizations, because we feel it is important to choose a measure where poor performance is viewed negatively by the provider’s peers. In contrast, higher reimbursement might not be viewed negatively by the provider’s peers. We do not list all hospitals, but only identify the high-cost outliers. This helps increase the negative reputational impact on these hospitals and, maybe more importantly, it decreases the likelihood of the perverse impact that low-cost hospitals will increase their costs. We have chosen to use the term “excessive” to make it compelling and easy to interpret that poor performance is wasteful. We have illustrated this for a condition, myocardial infarction, where patients cannot choose the provider. When focusing on the reputational pathway, it is not critical to focus on conditions where patients can make a choice

As we noted above, if one believes that consumer response is the pathway (selection pathway), then policymakers should focus on cost measures that for consumers are (1) relevant,(2) easily interpreted,(3) linked to corresponding quality measures, and (4) linked to financial incentives.

There are a new set of issues and questions if one pursues the reputational pathway. The key question to ask when selecting and presenting a measure, will poor performance be viewed negatively by the provider’s peers? Cost measures where higher cost implies poor quality will have the greatest impact such as rehospitalization rates, rates or costs of potentially avoidable complications, overuse measures (e.g., ordering unnecessary radiology tests for back pain), or excessive length of stay. In contrast, many currently used cost measures such as episode-based costs, differences in reimbursement, generic prescribing rates, or price transparency seem unlikely to negatively impact a provider’s reputation. In Exhibit 3 where we illustrate these concepts, we do not list all hospitals, but only identify the high-cost outliers. We focus on only high-cost outliers to increase the negative reputational impact on these hospitals. Also, and maybe more importantly, it decreases the likelihood of the perverse impact that low-cost hospitals will increase their costs. The concept that poor performance is wasteful must be compelling and easy to interpret. In our example, we have chosen to use the term “excessive” to make it more evident that this is negative performance. While we recognize that not all consumers will understand the concepts of length of stay and rehospitalizations, it is likely clear to key opinion makers and their peer hospitals. Lastly, in contrast to the selection pathway, we have focused on a condition, myocardial infarction, where patients cannot choose the provider and we do not link the measures to out-of-pocket costs.

Can both pathways be pursued?

Our focus on the choice of pathway does not mean that policymakers cannot pursue both pathways. In fact, by pursuing both pathways at the same time, there is the possibility of achieving some synergy between the two efforts, and thereby yielding more change.

However, the report would need to focus on a subset of measures that are appropriate for both pathways and would be likely need to be divided into sections for consumers and providers. For example, by repackaging or relabeling the data in Exhibit 3 (with plain language and icons to replace numbers). The concern is that there are relatively few measures that meet all of the criteria for both pathways.

Another alternative would be to divide up report cards by condition or patient choice. Where consumers do make a choice, the focus could be on the selection pathway. In other clinical areas where consumers are unlikely to make a choice, the focus could be on the reputational pathway. Other ways of combining the two pathways could be investigated. For example, in Exhibit 2 the focus is on the selection pathway for maternity hospitals. One could imagine that for the second higher-cost tier of hospitals, a more in-depth set of reputation pathway metrics are made available.

Acknowledging the lack of rigorous scientific data

With the great societal need to decrease health care spending, numerous efforts to publicly report cost measures are ongoing or in development. Given this intense interest, we have used our expertise to make recommendations on how to optimize the impact of public reporting of cost information. However, we fully acknowledge the limited scientific evidence base on public reporting of cost measures in isolation. More simply, we do not know if this will work.

Conclusions

In this article we summarize the pathways by which public reporting of cost measures can translate into lower costs. There are several key take-away points for policymakers.

First, in their current form and absent any financial incentives, publicly reporting of cost measures alone is unlikely to lead to the hoped for consumer response. It could even lead to the perverse impact of consumers switching their care to higher-cost providers.

Second, we believe policymakers should consider the intended pathway when selecting cost measures for public reporting and deciding how the measures are presented. With the selection pathway (focus on consumers) the keys are that the cost measures are relevant to consumer interests, easy to interpret, and tied to quality measures and financial incentives. With the reputational pathway (focus on providers) the keys are that the cost measures are viewed by opinion makers and provider’s peer group as clearly signaling wastefulness or poor quality. With the reputational pathway the measures can focus on the full range of conditions including emergent (e.g., myocardial infarction) and don’t need to be tied to financial incentives. We have highlighted some potential solutions and challenges if one wants to pursue both pathways.

In the context of great urgency in national efforts to curb health care spending, it is critical that we do not assume that consumers will respond to any cost information that is provided. We must be thoughtful in our approach and figure out how to do this right.

References

- 1.Fan J. [cited 2012 Jan 16];After health bill, a push to curb costs. The Tech [Internet] 2010 Apr 2;130(16) [about 1 p.] Available from: http://tech.mit.edu/V130/N16/healthcare.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennberg JE, Fisher ES, Baker L, Sharp SM, Bronner KK. Evaluating the efficiency of California providers in caring for patients with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jul-Dec;:W5-526–43. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.526. Suppl Web Exclusives. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandy LG, Rattray MC, Thomas JW. Episode-based physician profiling: a guide to the perplexing. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Sep;23(9):1521–4. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0684-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Quality Forum (NQF) Measurement framework: evaluating efficiency across patient-focused episodes of care. NQF; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussey PS, de Vries H, Romley J, Wang MC, Chen SS, Shekelle PG, McGlynn EA. A systematic review of health care efficiency measures. Health Serv Res. 2009 Jun;44(3):784–805. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.AQA Alliance . AQA principles of “efficiency” measures [Internet] AQA; [cited 2012 Jan 16]. 2009. Available from: http://www.aqaalliance.org/files/PrinciplesofEfficiencyMeasureme nt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyle MK, Ridley DB. Would greater transparency and uniformity of health care prices benefit poor patients? Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Sep-Oct;26(5):1384–91. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002 May-Jun;21(3):80–90. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams JL, McGlynn EA, Thomas JW, Mehrotra A. Incorporating statistical uncertainty in the use of physician cost profiles. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehrotra A, Adams JL, Thomas JW, McGlynn EA. The effect of different attribution rules on individual physician cost profiles. Ann Intern Med. 2010 May 18;152(10):649–54. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-10-201005180-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christianson JB, Feldman R. Evolution in the Buyers Health Care Action Group purchasing initiative. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002 Jan-Feb;21(1):76–88. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Quality Forum (NQF) Measurement evaluation criteria [Internet] NQF; Washington, D.C.: [cited 2012 Jan 16]. 2009. Available from: http://www.qualityforum.org/Measuring_Performance/Submitting_Sta ndards/Measure_Evaluation_Criteria.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berwick DM, James B, Coye MJ. Connections between quality measurement and improvement. Med Care. 2003 Jan;41(1 Suppl):I30–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200301001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hibbard JH. What can we say about the impact of public reporting? Inconsistent execution yields variable results. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jan 15;148(2):160–1. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bloche MG. Consumer-directed health care. N Engl J Med. 2006 Oct 26;355(17):1756–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Health policy brief: putting limits on “Medigap.”. Health Aff (Millwood) Updated September 21, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Werner RM, Asch DA. The unintended consequences of publicly reporting quality information. JAMA. 2005 Mar 9;293(10):1239–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, Brook RH. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence [see comments] JAMA. 2000;283(14):1866–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.14.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hibbard J, Greene J, Sofaer S, Firminger K, Hirsh J. communicating with consumers about value in health care:findings from a controlled experiment. Health Aff (Millwood) In Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carman KL, Maurer M, Yegian JM, Dardess P, McGee J, Evers M, et al. Evidence that consumers are skeptical about evidence-based health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Jul;29(7):1400–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Increased price transparency in health care--challenges and potential effects. N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 10;364(10):891–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1100041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waber RL, Shiv B, Carmon Z, Ariely D. Commercial features of placebo and therapeutic efficacy. JAMA. 2008 Mar 5;299(9):1016–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.9.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vaiana ME, McGlynn EA. What cognitive science tells us about the design of reports for consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2002 Mar;59(1):3–35. doi: 10.1177/107755870205900101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Consumer experience with a tiered physician network: early evidence. Am J Manag Care. 2010 Feb;16(2):123–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fisher ES, Staiger DO, Bynum JP, Gottlieb DJ. Creating accountable care organizations: the extended hospital medical staff. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007 Jan-Feb;26(1):w44–57. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.w44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters E, Dieckmann N, Dixon A, Hibbard JH, Mertz CK. Less is more in presenting quality information to consumers. Med Care Res Rev. 2007 Apr;64(2):169–90. doi: 10.1177/10775587070640020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenthal MB, Li Z, Milstein A. Do patients continue to see physicians who are removed from a PPO network? Am J Manag Care. 2009 Oct;15(10):713–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.New frontiers in quality initiatives: hearing before the Subcomm.on Health of the Comm. on Ways and Means [Internet]; 108th Cong., 2nd Sess.; March 18, 2004; [cited 2012 Jan 18]. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-108hhrg99678/html/CHRG-108hhrg99678.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swartz K. Cost-sharing: effects on spending and outcomes. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lesser CS, Lucey CR, Egener B, Braddock CH, 3rd, Linas SL, Levinson W. A behavioral and systems view of professionalism. JAMA. 2010 Dec 22;304(24):2732–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Does publicizing hospital performance stimulate quality improvement efforts? Health Aff (Millwood) 2003 Mar-Apr;22(2):84–94. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mehrotra A, Damberg C, Sorbero M, Teleki S. Pay-for-performance in the hospital setting: what is the state of the evidence? AM J Med Qual. 2009 doi: 10.1177/1062860608326634. (OnlineFirst, published on December 10, 2008 as doi:10.1177/1062860608326634) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Tusler M. Hospital performance reports: impact on quality, market share, and reputation. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005 Jul-Aug;24(4):1150–60. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.4.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pauly MV. Is medical care different? Old questions, new answers. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1988 Summer;13(2):227–37. doi: 10.1215/03616878-13-2-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brennan TA, Spettell CM, Fernandes J, Downey RL, Carrara LM. Do managed care plans’ tiered networks lead to inequities in care for minority patients? Health Aff (Millwood) 2008 Jul-Aug;27(4):1160–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.4.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.HospitalCompare.hhs.gov [Internet] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: [updated 2011 October 13]. [cited 16 Jan 2012]. Available from: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qualityquest.org [Internet] Quality Quest for Health of Illinois; Peoria, IL: [cited 2012 Jan 16]. c2009. Available from: www.qualityquest.org. [Google Scholar]

- 39.NJhospitalpricecompare.com [Internet] New Jersey Hospital Association; Princeton: [cited 2012 Jan 16]. c2001-2012. Available from: http://www.njhospitalpricecompare.com/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Florida Agency for Health Care Administration (FAHCA) Nursing home guide. FAHCA; Tallahassee, FL: [cited 2012 Jan 16]. Available from: http://apps.ahca.myflorida.com/NHCGUIDE/RegionMap.aspx. [Google Scholar]