Abstract

Plant nutrition is one of the important areas for improving the yield and quality in crops as well as non-crop plants. Potassium is an essential plant nutrient and is required in abundance for their proper growth and development. Potassium deficiency directly affects the plant growth and hence crop yield and production. Recently, potassium-dependent transcriptomic analysis has been performed in the model plant Arabidopsis, however in cereals and crop plants; such a transcriptome analysis has not been undertaken till date. In rice, the molecular mechanism for the regulation of potassium starvation responses has not been investigated in detail. Here, we present a combined physiological and whole genome transcriptomic study of rice seedlings exposed to a brief period of potassium deficiency then replenished with potassium. Our results reveal that the expressions of a diverse set of genes annotated with many distinct functions were altered under potassium deprivation. Our findings highlight altered expression patterns of potassium-responsive genes majorly involved in metabolic processes, stress responses, signaling pathways, transcriptional regulation, and transport of multiple molecules including K+. Interestingly, several genes responsive to low-potassium conditions show a reversal in expression upon resupply of potassium. The results of this study indicate that potassium deprivation leads to activation of multiple genes and gene networks, which may be acting in concert to sense the external potassium and mediate uptake, distribution and ultimately adaptation to low potassium conditions. The interplay of both upregulated and downregulated genes globally in response to potassium deprivation determines how plants cope with the stress of nutrient deficiency at different physiological as well as developmental stages of plants.

Introduction

Potassium is one of the essential macronutrients required for plant growth and development. It plays a major role in different physiological processes like cell elongation, stomatal movement, turgor regulation, osmotic adjustment, and signal transduction by acting as a major osmolyte and component of the ionic environment in the cytosol and subcellular organelles [1]–[7]. Potassium is also required for balancing the electrical charge of membranes, energy generation by proton pump activity, long-distant transport of ions from root to shoot, protein synthesis, enzyme activation, and metabolism of sugars and nitrogen [2], [8], [9]. Since potassium is one of the major plant macronutrients (cytosolic K+ concentration is approximately 100 mM), potassium deficiency poses a severe agricultural challenge and requires the use of large quantities of chemical fertilizers for sustainable agricultural practices.

Previous studies report that potassium acts as an activator or cofactor in several enzyme systems [10]. Enzymatic activity of pyruvate kinase, starch synthase, nitrate reductase, and rubisco are all directly connected to metabolic changes under potassium deficiency [11]–[14]. One of the hallmarks of potassium deficiency is chlorosis (yellowing) in older leaves, a consequence of mobilization of potassium from older leaves to younger growing tissues [2], [9], [15].

Potassium uptake takes place in the roots of plants; potassium is subsequently redistributed to plant tissues and organs and stored in abundance in vacuoles. Plant roots tolerate short-term potassium deprivation by utilizing potassium stored in the vacuole when available. When plants grow in potassium-deficient soil, the root cells sense the low concentrations of K+ and initiate a series of physiological reactions [16], [17]. The detailed physiological role of potassium absorption and uptake has been studied in several plant species, and the molecular mechanisms of potassium transport have been largely elucidated in Arabidopsis. A large number of transporters and channels in Arabidopsis have been implicated in the uptake and mobilization of potassium from root to other parts of the plant [4], [18]–[21]. To adjust fluctuation of potassium levels in the soil, plants have adopted two modes of potassium uptake in their roots, namely high-affinity and low-affinity uptake [4], [22], [23]. Recently, studies implicated calcium-mediated CBL-CIPK signaling in regulating the shaker family K+ channels AKT1 and AKT2, however detailed mechanistics of potassium sensing remain elusive [6], [24], [25]. Research related to the molecular mechanisms of K+ sensing, uptake, distribution, and homeostasis in cereal and non-cereal crops is still miniscule. Although considerable work has been done in the model plant Arabidopsis, an extensive amount of work is still needed in crop plants to understand the detail mechanisms of K+ nutrition and signaling.

In this study, we used whole genome microarrays to determine the transcriptomic profile of rice seedlings exposed to short-term K+ deficiency followed by K+ resupply. We applied Benjamini-Hochberg correction to filter the differentially expressed genes in different conditions. We also performed PCA (Principal Component Analysis) and Pearson correlation coefficient analysis to ensure reliability of the data. According to our microarray data, potassium deficiency affects the expression of various genes, which were grouped into different categories such as metabolism, transcription factor, transporter, signal transduction. The objective of this study is to determine the expression pattern of genes under low potassium stress conditions and to determine the role of these genes in potassium homeostasis and adaptation in potassium-deficient soil.

Results

Phenotypic Analysis of K+ Deficiency on Rice Seedling Growth

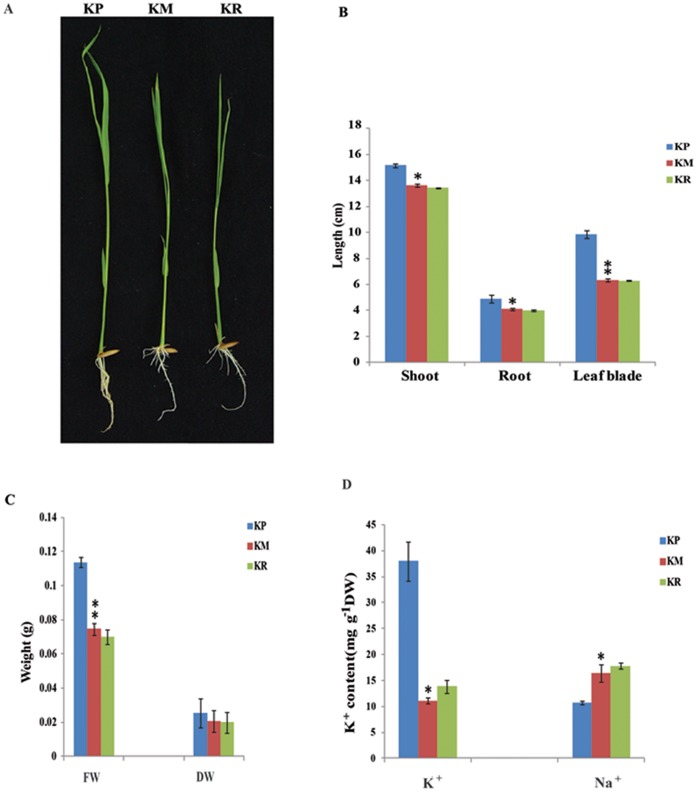

For transcriptional analysis under potassium deficiency, 5 days old hydroponically grown indica rice IR64 seedlings were transferred to a potassium-deficient medium for 5 days followed by resupply of potassium for 6 h. Seedlings grown in potassium-deficient media had reduced shoot and root growth and leaf blade height (Figure 1A, B). However, there was no phenotypic difference between K+ minus or starved (KM) and K+ resupply (KR) seedlings after treatment for 6 h. In addition, we observed a higher number of root hairs in KM seedlings while more lateral roots were seen in K+ plus or normal growth (KP) seedlings (Figure 1A, B). The biomass and ion content (K+, Na+) of seedlings were also measured for each condition. The fresh and dry weight of KM seedlings was lower after 5 days of K+ deficiency compared to normal growth conditions, whereas no significant difference was observed between KM and KR (Figure 1C). In order to determine the total K+ and Na+ content, single-channel flame photometry (see Material and Methods) was performed for all the three conditions. KM seedlings contained about 4 times less K+ than KP seedlings while KR showed slightly higher K+ than KM plants (Figure 1D). Na+ content was lower in KP condition as compared to KM and KR condition, however no significant difference was found in KM and KR seedlings.

Figure 1. Growth and ion content analysis of rice seedlings during potassium nutrient deficiency.

(A) Analysis was performed 5 days after transfer of seedling in KP and KM medium. Phenotypes of rice seedlings under normal, K+ deficient and resupply conditions (KP, KM and KR). (B) Length of rice shoot, root and leaf blade under three different conditions. (C) Fresh and dry weight comparison of rice seedling. (D) K+ and Na+ content of rice seedlings. Differences between mean values of treatments and controls were compared using t - tests (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01).

Global Expression Analysis in Response to Potassium Deficiency and Resupply Condition

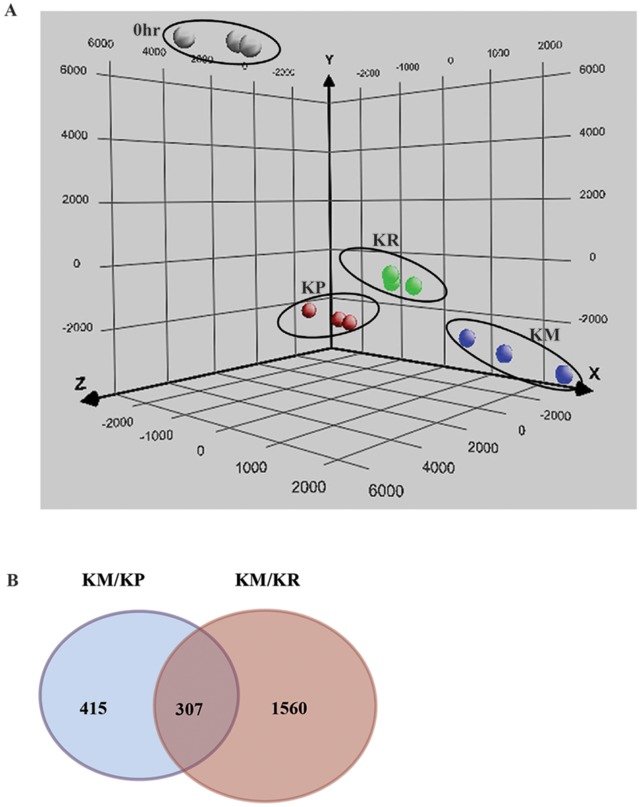

To obtain insights into changes in rice gene expression profiles under potassium deprivation and resupply of potassium, we performed rice whole genome microarrays using Affymetrix gene chip (57 K). Rice seedlings were subjected to three different conditions, viz. K+ plus (KP), K+ minus (KM), and K+ resupply (KR) after five days of normal growth as described in the material and method. Total RNA was isolated from treated seedlings and used for whole genome microarray analysis. The microarray gene expression data was normalized against data obtained for samples grown on normal media for five days (untreated seedlings) in order to eliminate potassium-responsive genes involved in early growth and development of seedlings. To determine the accuracy and reliability of the data obtained, microarray data of three biological replicates for each treatment was analysed for their correlation coefficient, and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was also performed. Correlation between the biological replicates was calculated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient based on the signal intensities. The three replicates of each treatment showed correlation coefficient of greater than 0.98 (Table 1). The values of the correlation coefficients of the three replicates were further reinforced by the result of the PCA, wherein the biological replicates for each treatment showed a high degree of correlation. Interestingly, the PCA cluster for the third treatment i.e. resupply of K+-deficient medium with K+ for 6 h (KR) was positioned closer to the PCA cluster of the K+-plus condition (KP) as compared to the PCA cluster for the K+-minus condition (KM) (Figure 2A). This indicated that resupplying potassium externally for 6 h restored expression of many genes to their normal levels [i.e. K+ plus condition (KP)].

Table 1. Correlation data from microarray analysis.

| Array Name | KR1 | KR2 | KR3 | 0 hr1 | 0 hr2 | 0 hr3 | KP1 | KP2 | KP3 | KM1 | KM2 | KM3 |

| KR1 | 1 | 0.9942733 | 0.991799 | 0.8602868 | 0.8646402 | 0.8550841 | 0.945861 | 0.958903 | 0.960618 | 0.940772 | 0.949816 | 0.948117 |

| KR2 | 0.9942733 | 1 | 0.9917473 | 0.8624464 | 0.8658453 | 0.8552977 | 0.944316 | 0.959933 | 0.960965 | 0.938354 | 0.947319 | 0.945787 |

| KR3 | 0.991799 | 0.9917473 | 1 | 0.8662803 | 0.8702267 | 0.8627964 | 0.944466 | 0.954373 | 0.958572 | 0.935967 | 0.942745 | 0.940963 |

| 0 hr1 | 0.8602868 | 0.8624464 | 0.8662803 | 1 | 0.9964587 | 0.9892928 | 0.875728 | 0.879222 | 0.874045 | 0.869435 | 0.857152 | 0.858365 |

| 0 hr2 | 0.8646402 | 0.8658453 | 0.8702267 | 0.9964587 | 1 | 0.9915484 | 0.873703 | 0.878731 | 0.874345 | 0.869253 | 0.858916 | 0.859034 |

| 0 hr3 | 0.8550841 | 0.8552977 | 0.8627964 | 0.9892928 | 0.9915484 | 1 | 0.863212 | 0.864016 | 0.859468 | 0.861733 | 0.850758 | 0.85059 |

| KP1 | 0.945861 | 0.9443161 | 0.9444658 | 0.875728 | 0.8737032 | 0.8632119 | 1 | 0.989603 | 0.984926 | 0.946355 | 0.944624 | 0.946672 |

| KP2 | 0.9589027 | 0.9599334 | 0.9543728 | 0.8792217 | 0.8787307 | 0.8640156 | 0.989603 | 1 | 0.992018 | 0.950186 | 0.953336 | 0.954741 |

| KP3 | 0.9606177 | 0.9609647 | 0.9585716 | 0.8740448 | 0.8743453 | 0.8594683 | 0.984926 | 0.992018 | 1 | 0.952037 | 0.956309 | 0.957403 |

| KM1 | 0.9407717 | 0.938354 | 0.9359667 | 0.8694348 | 0.8692533 | 0.8617328 | 0.946355 | 0.950186 | 0.952037 | 1 | 0.992166 | 0.992698 |

| KM2 | 0.9498156 | 0.9473191 | 0.9427447 | 0.8571518 | 0.8589162 | 0.8507582 | 0.944624 | 0.953336 | 0.956309 | 0.992166 | 1 | 0.997317 |

| KM | 0.948117 | 0.9457873 | 0.9409633 | 0.8583649 | 0.8590338 | 0.8505895 | 0.946672 | 0.954741 | 0.957403 | 0.992698 | 0.997317 | 1 |

Figure 2. Overview of the changes in transcripts in potassium sufficient, deficient and resupply condition.

(A) Principal component analysis (PCA) of the changes in transcript abundance in rice seedling under different condition. (B) Venn diagram showing the number of differentially expressed genes (P<0.05 and fold change equal or more than 2) in response to KM/KP and KR/KM in seedling.

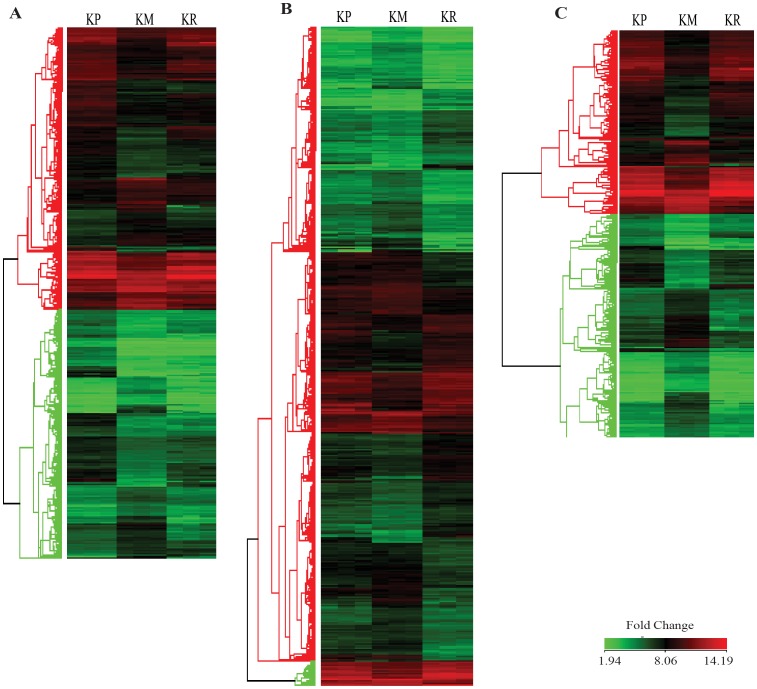

After normalization of the microarray data, differential expression analysis was performed for the following pairwise combinations of the three test conditions: KP and KM (KP/KM) and KM and KR (KM/KR). Differentially expressed genes were identified on the basis of following two criteria: first, the fold change, wherein genes with a fold change of ≥2 were considered for analysis and second, the unpaired t-test, wherein genes with p-value ≤0.05 were selected for analysis. False discovery rate (FDR) correction (Benjamini-Hochberg Correction) was applied, which added greater significance to the data. 722 genes were differentially expressed under potassium deficient (KM) condition while 1867 genes were differentially expressed upon potassium resupply (KR). The details (probe set Ids, signal intensity value, p-value, fold change and regulation) of 722 and 1867 genes is given in Table S1 and Table S2 respectively. Among these 722 differentially expressed genes, 281 genes showed up regulation and 441 genes were down regulated (Figure 3A). Out of the 1867 genes differentially expressed upon potassium resupply, 866 showed up regulation, while 1001 genes were down regulated (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Hierarchical cluster analysis.

(A) Hierarchical cluster analysis of the 722 potassium responsive genes found in potassium deficient condition, (B) 1876 genes found in potassium resupply condition and (C) 307 genes found common between potassium deficient and resupply condition, which were truly differentially expressing under K+ deficient conditions based on their reversal of expression upon resupply condition.

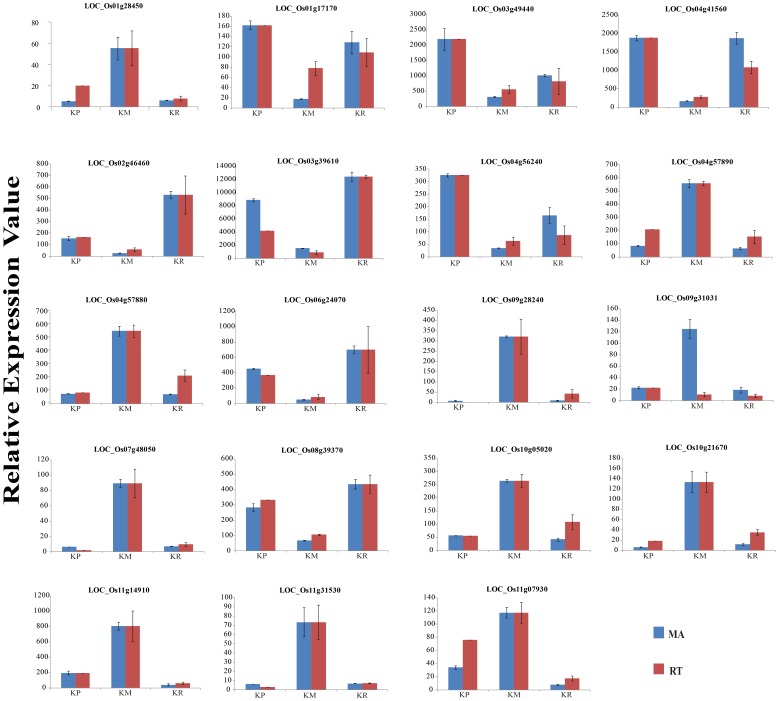

A total of 307 differentially expressed genes were common for both KP and KR condition (Figure 2B, Figure 3C), details of which are given in Table S3. For the validation of microarray data, 19 significantly and differentially expressed genes representing different categories were selected for quantitative realtime PCR (qPCR) analysis. The results of qPCR of the 19 tested genes were in accordance with the microarray results, which authenticated our microarray data and established its reliability (Figure 4, Table S4). The raw data sets (CEL) and the normalized expression data sets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus at the National Center for Biotechnology Information with the accession number GSE44250 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Figure 4. Confirmation of microarray data for selected genes by qRT-PCR analysis.

Nineteen genes were selected and their expression profiles were assessed by qRT-PCR in all three conditions to verify the microarray data by using three biological replicates. Y-axis represents relative expression values obtained after normalizing the data against maximum expression value and X-axis shows different nutritional treatments. Blue bars represent the expression from microarrays, while red bars represent the qRT- PCR values.

Functional Classification of the Differentially Expressed Genes

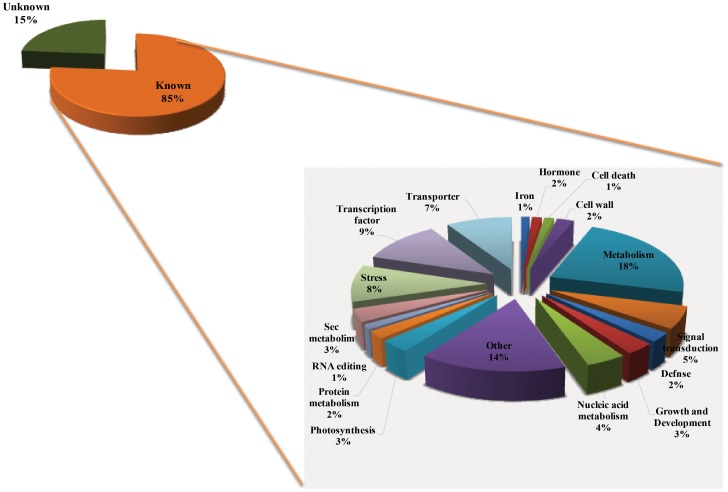

The differentially expressed genes in potassium-deficient conditions were functionally classified by homology search against the Gene Ontology (GO) and NCBI Non-redundant (NR) databases using BLAST through NCBI. Genes encoding hypothetical proteins were classified as genes of unknown function. Among the 722 genes that were differentially expressed under potassium deprivation, 15% of the genes belonged to the unknown function category (Figure 5). The remaining 85% genes were categorised into 17 comprehensive subdivisions corresponding to the following functions: primary metabolism, secondary metabolism, nucleic acid metabolism, transporters, transcription factors, auxin signaling components, cell wall metabolism, cell death, growth and development, photosynthesis, stress responses, etc. (Figure 5). Genes that could not be classified into any of the above-mentioned categories were placed in the category of “others”. Overall, this analysis indicate that potassium deficiency affects the expression of genes with diverse functions in metabolism, transcriptional regulation, stress responses, molecular transport and signal transduction. In all, nearly 56% of total differentially expressed genes are involved in these processes according to their annotation.

Figure 5. Functional categorization of potassium responsive genes into different categories.

Detailed classification of genes showing transcriptional changes in the several categories based on the gene ontology (GO) and their putative function.

18% of differentially expressing genes (DEG) were involved in various metabolic pathways, including 4% in nucleic acid metabolism, 3% in secondary metabolism and 2% in protein metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism (primary metabolism), lipid metabolism, glycolytic enzymes and other biosynthetic pathways (Table 2). Of all the DEG, 7% were transporters, including three potassium transporters HAK1, OsHKT2;3 and OsHKT2;4; ABC transporter; 3 peptide transporter PTR2 and PTR3-A, and many other diverse transporters. Diverse group of kinases (CIPKs and MAPKs), phosphatases (PP2C and other Ser/Thr protein phosphatases), and calcium sensors (CMLs and CBLs) known to be involved in signal transduction mechanism constituted 5% of DEG. Significant percentages of the total DEG were comprised of genes annotated as transcription factors (9%) and stress responsive genes (8%). A small group of genes related to photosynthesis (3%), growth and development (3%), cell wall (2%), defence (2%), and auxin (1%) were also differentially expressed under potassium-deficient conditions.

Table 2. Different category of differentially regulated genes in potassium deficient condition.

| Probe Set ID | LOC_ID | Putative Function | FC in KM | Regulation in KM | FC in KR | Regulation in KR |

| Carbohydrate metabolism | ||||||

| Os.9996.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g10980 | pyruvate kinase, putative, expressed | 5.8973556 | down | 2.7624514 | up |

| Os.57437.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g52700 | alpha-amylase precursor | 16.978466 | up | 13.761532 | down |

| Os.38240.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os12g08760 | carboxyvinyl-carboxyphosphonate phosphorylmutase, putative, expressed | 62.562016 | down | 3.4629653 | up |

| Os.33211.1.S1_at | LOC_Os09g28430 | alpha-amylase precursor | 49.027573 | up | 44.134583 | down |

| Os.50903.1.S1_at | LOC_Os09g08130 | indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase, chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed | 4.5081425 | up | 6.329595 | down |

| Os.9212.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g22930 | starch synthase, putative, expressed | 10.27882 | down | 1.8906631 | up |

| Os.17814.2.S1_x_at | LOC_Os07g43700 | lactate/malate dehydrogenase, putative, expressed | 4.746752 | down | 4.3317947 | up |

| Lipid metabolism | ||||||

| Os.17491.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g35070 | Alpha-galactosidase precursor, putative, expressed | 4.75564 | down | 2.4528239 | up |

| Os.10339.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g04770 | beta-amylase, putative, expressed | 8.125269 | down | 1.3109915 | up |

| Os.46633.1.A1_at | LOC_Os10g38940 | fatty acid hydroxylase, putative, expressed | 3.8152332 | down | 2.6639307 | up |

| Os.50047.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g11680 | glucosyltransferase, putative, expressed | 3.1383889 | down | 1.010676 | up |

| Os.7665.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g56240 | lipase, putative, expressed | 9.613265 | down | 4.904837 | up |

| Os.7985.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g18070 | omega-3 fatty acid desaturase, chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed | 8.088967 | down | 2.869564 | up |

| Os.8569.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g48880 | fatty acid hydroxylase, putative, expressed | 7.0666585 | down | 3.1543837 | up |

| Secondary metabolism | ||||||

| Os.12161.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g50760 | polyprenyl synthetase, putative, expressed | 2.1792645 | down | 1.5211341 | up |

| Os.18305.1.S2_at | LOC_Os05g50550 | polyprenyl synthetase, putative, expressed | 4.09671 | down | 1.2781891 | down |

| Os.22651.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g56230 | polyprenyl synthetase, putative, expressed | 3.5511298 | down | 1.7434987 | up |

| Os.18299.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g07410 | oxidoreductase, 2OG-Fe oxygenase family protein, putative, expressed | 2.0075734 | down | 1.7679305 | up |

| Os.28290.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g47510 | 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase 1, chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed | 3.8347073 | down | 5.148261 | up |

| Os.57569.2.A1_s_at | LOC_Os08g04500 | terpene synthase, putative, expressed | 9.682299 | down | 1.2949013 | up |

| OsAffx.13994.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g27430 | terpene synthase, putative | 20.18755 | down | 1.5568593 | up |

| OsAffx.28637.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os07g27970 | O-methyltransferase, putative, expressed | 3.0486414 | down | 1.0420687 | down |

| Os.11122.1.S1_at | LOC_Os08g37456 | flavonol synthase/flavanone 3-hydroxylase, putative, expressed | 3.2668943 | up | 1.0315864 | up |

| Os.46813.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g20610.1 | laccase-15 precursor, putative, expressed | 4.0983953 | up | 4.2176743 | down |

| OsAffx.7606.1.S1_at | LOC_Os12g15680.1 | laccase precursor protein, putative, expressed | 6.6438375 | up | 12.205469 | down |

| Protein metabolism | ||||||

| Os.11946.1.S1_at | LOC_Os06g21380 | OsCttP3 - Putative C-terminal processing peptidase homologue, expressed | 14.64291 | down | 1.1892594 | up |

| Os.50769.1.A1_at | LOC_Os06g03120 | aspartic proteinase nepenthesin-2 precursor, putative | 3.9677827 | down | 1.3502886 | up |

| Os.52208.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g45990 | von Willebrand factor type A domain containing protein, putative, expressed | 7.479702 | down | 1.1065638 | down |

| Os.52261.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g47360 | OsPOP9 - Putative Prolyl Oligopeptidase homologue, expressed | 6.0788016 | down | 1.0184413 | down |

| Os.18819.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g06660 | OsSCP26 - Putative Serine Carboxypeptidase homologue, expressed | 2.0857537 | up | 1.4075973 | down |

| Os.4181.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g67980 | cysteine proteinase EP-B 1 precursor, putative, expressed | 22.488976 | up | 8.29099 | down |

| Nucleic acid metabolism | ||||||

| Os.56275.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os10g41100 | CCT motif family protein, expressed | 8.075855 | down | 2.332891 | up |

| Os.57417.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os05g50930 | RNA polymerase sigma factor, putative, expressed | 6.873295 | down | 1.0277363 | up |

| Os.3407.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os08g06630 | RNA polymerase sigma factor, putative, expressed | 3.5794642 | down | 2.7469041 | up |

| Os.14820.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os05g51150 | RNA polymerase sigma factor, putative, expressed | 2.5400774 | up | 1.2800328 | up |

| Photosynthesis | ||||||

| Os.12181.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os11g13890 | chlorophyll A–B binding protein, putative, expressed | 4.180208 | down | 7.1355653 | up |

| Os.12296.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g39610 | chlorophyll A–B binding protein, putative, expressed | 6.138936 | down | 9.02072 | up |

| Os.28216.2.S1_a_at | LOC_Os07g37550 | chlorophyll A–B binding protein, putative, expressed | 4.8379245 | down | 8.404701 | up |

| Os.57519.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os01g14410 | early light-induced protein, chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed | 4.234971 | down | 1.6210355 | down |

| Os.7868.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g17170 | magnesium-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase,chloroplast precursor, putative, expressed | 9.336843 | down | 6.4937716 | up |

| Defense | ||||||

| Os.2416.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os01g71340 | glycosyl hydrolases family 17, putative, expressed | 4.742775 | up | 1.6272075 | down |

| Os.418.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g28450 | SCP-like extracellular protein, expressed | 12.021974 | up | 9.981392 | down |

| Os.459.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g46070 | thaumatin, putative, expressed | 3.5260322 | up | 5.110073 | down |

| Os.49615.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g45960 | thaumatin, putative, expressed | 3.8472998 | up | 8.540888 | down |

| Stress | ||||||

| Drought stress | ||||||

| Os.12167.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g44870 | dehydrin, putative, expressed | 2.9321172 | down | 1.1124701 | up |

| Os.27642.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g30320 | drought-induced protein 1, putative, expressed | 2.1810718 | down | 1.4512954 | up |

| Os.54341.1.S1_at | LOC_Os12g43720 | early-responsive to dehydration protein-related, putative, expressed | 3.4949756 | down | 1.1637394 | down |

| Os.6812.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g21670 | dehydration stress-induced protein, putative, expressed | 20.037441 | up | 9.9064045 | down |

| GST | ||||||

| Os.22957.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g72140 | glutathione S-transferase, putative, expressed | 7.938599 | up | 12.89018 | down |

| Os.40000.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g38600 | glutathione S-transferase GSTU6, putative, expressed | 3.4470932 | up | 7.7719364 | down |

| Os.46634.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g38489 | glutathione S-transferase GSTU6, putative, expressed | 2.544139 | up | 5.0398207 | down |

| Os.46635.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os10g38350.1 | glutathione S-transferase, putative, expressed | 2.723984 | up | 7.052062 | down |

| Heat stress | ||||||

| Os.26059.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g20730 | chaperone protein dnaJ, putative, expressed | 2.3602993 | down | 1.4174172 | up |

| Os.49277.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g53020 | heat shock protein DnaJ, putative, expressed | 2.5835004 | down | 5.9116116 | up |

| Os.5648.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g01160 | heat shock protein DnaJ, putative, expressed | 4.7269297 | down | 1.9027811 | up |

| Os.57477.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os11g47760.1 | DnaK family protein, putative, expressed | 2.0001137 | down | 1.4022813 | up |

| OsAffx.11879.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g03570 | hsp20/alpha crystallin family protein, putative, expressed | 2.594732 | up | 3.2607677 | down |

| Os.11941.2.S1_at | LOC_Os09g35790 | HSF-type DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 2.0028756 | down | 1.1283132 | up |

| OsAffx.26649.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os04g57880 | heat shock protein DnaJ, putative, expressed | 7.3370676 | up | 7.996968 | down |

| Oxidation-reduction | ||||||

| Os.23290.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g40960 | oxidoreductase, 2OG-Fe oxygenase family protein, putative, expressed | 2.322114 | up | 1.8621931 | down |

| Os.25496.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g07930 | oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family domain containing family, expressed | 3.465435 | up | 17.474422 | down |

| Os.7392.2.S1_x_at | LOC_Os01g62880 | oxidoreductase, aldo/keto reductase family protein, putative, expressed | 2.1068213 | up | 2.3765166 | down |

| Os.9230.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os10g35370 | oxidoreductase, short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family domain containing family, expressed | 2.0683372 | down | 4.2801576 | up |

| Os.11266.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g09830 | OsGrx_A2 - glutaredoxin subgroup III, expressed | 4.5280557 | up | 16.795298 | down |

| Os.12100.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g29410 | thioredoxin, putative, expressed | 2.4418237 | down | 2.615967 | up |

| Os.36648.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os01g13480 | glutaredoxin, putative, expressed | 3.831749 | down | 1.0782503 | down |

| OsAffx.15537.1.S1_at | LOC_Os06g21550 | thioredoxin domain-containing protein 17, putative, expressed | 4.0799003 | up | 2.8130107 | down |

| Plant hormone | ||||||

| Auxin | ||||||

| OsAffx.14380.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os04g52670.1 | OsSAUR21 - Auxin-responsive SAUR gene family member, expressed | 2.4365497 | up | 1.091372 | up |

| Os.12501.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g55940 | OsGH3.2 - Probable indole-3-acetic acid-amido synthetase, expressed | 2.102113 | up | 2.3879192 | down |

| Os.18493.1.S1_at | LOC_Os09g37480 | OsSAUR53 - Auxin-responsive SAUR gene family member, expressed | 2.7041986 | down | 2.0083132 | up |

| Os.19952.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g09450 | OsIAA2 - Auxin-responsive Aux/IAA gene family member, expressed | 2.3135202 | up | 1.126054 | down |

| Os.56924.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g41420 | auxin-induced protein 5NG4, putative, expressed | 2.6951323 | down | 2.5001767 | up |

| Jasmonic Acid | ||||||

| Os.15829.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g10120 | lipoxygenase, putative, expressed | 16.1165 | down | 4.611044 | up |

| Os.6863.1.S1_at | LOC_Os12g14440 | Jacalin-like lectin domain containing protein, putative, expressed | 65.412315 | down | 1.8992921 | up |

| Gibberellin | ||||||

| Os.27673.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g14730 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2, putative, expressed | 2.4927118 | down | 1.7543458 | up |

| Os.30608.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g41954 | gibberellin 2-beta-dioxygenase 7, putative, expressed | 2.1261473 | down | 2.3699095 | up |

| Os.33885.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g06220 | gibberellin receptor GID1L2, putative, expressed | 3.5340044 | up | 9.710723 | down |

| Ethylene-responsive | ||||||

| OsAffx.12799.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os03g09170 | ethylene-responsive transcription factor, putative, expressed | 4.337239 | down | 1.7307606 | up |

| OsAffx.12775.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g07940 | AP2 domain containing protein, expressed | 2.0415235 | up | 1.8989204 | down |

| Cell wall | ||||||

| Os.158.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g02070 | peroxidase precursor, putative, expressed | 2.1756594 | down | 4.579428 | up |

| Os.2373.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g40710 | expansin precursor, putative, expressed | 3.3498163 | down | 3.2064276 | up |

| Os.5034.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g47990 | peroxidase precursor, putative, expressed | 3.2906973 | down | 3.9200315 | up |

| Os.57547.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g48050 | peroxidase precursor, putative, expressed | 16.27228 | up | 13.841287 | down |

| OsAffx.17389.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os08g37930 | beta-expansin precursor, putative, expressed | 4.7917747 | up | 1.8499234 | down |

| Os.5087.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g03780.1 | alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase, putative, expressed | 2.0912318 | up | 1.0629448 | down |

| OsAffx.26676.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g01370 | polygalacturonase inhibitor precursor, putative, expressed | 2.1363134 | up | 1.4509802 | down |

| Signal ransduction | ||||||

| CIPK | ||||||

| Os.41019.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g35184.1 | CIPK8 | 2.0357978 | down | 1.1911937 | up |

| Os.17787.1.S1_at | LOC_Os07g48090 | CIPK29 | 3.334685 | down | 3.260447 | up |

| Os.19815.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g43440 | CIPK7 | 2.9495628 | down | 3.3653092 | up |

| MAPK | ||||||

| Os.11617.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g49140 | CGMC_MAPKCMGC_2.8 - CGMC includes CDA, MAPK, GSK3, and CLKC kinases, expressed | 2.0979733 | down | 2.1305962 | up |

| Os.27170.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g50400 | STE_MEKK_ste11_MAP3K.5 - STE kinases include homologs to sterile 7, sterile 11 and sterile 20 from yeast, expressed | 3.7302904 | down | 2.896405 | up |

| Os.5940.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g50370 | STE_MEKK_ste11_MAP3K.4 - STE kinases include homologs to sterile 7, sterile 11 and sterile 20 from yeast, expressed | 6.0885477 | down | 2.018108 | up |

| Calcium sensor | ||||||

| Os.2216.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g59530 | OsCML1 - Calmodulin-related calcium sensor protein, expressed | 2.9643536 | up | 2.7207763 | down |

| Os.49658.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g45810 | calcineurin B, putative, expressed | 3.1708822 | down | 1.2174544 | up |

| Os.8862.1.S1_at | LOC_Os09g28510 | EF hand family protein, putative, expressed | 2.0125606 | up | 1.5394444 | down |

| Os.8889.1.S1_at | LOC_Os05g50180 | OsCML14 - Calmodulin-related calcium sensor protein, expressed | 3.8419423 | down | 2.0545144 | up |

| Phosphatase | ||||||

| Os.12150.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g33080 | protein phosphatase 2C, putative, expressed | 2.380953 | down | 1.4617312 | up |

| Os.12535.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g52230 | phosphoethanolamine/phosphocholine phosphatase, putative, expressed | 5.0726867 | down | 1.2910246 | down |

| Os.49226.1.S1_at | LOC_Os12g38750 | nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase, putative, expressed | 3.5158448 | up | 1.9599011 | down |

| Os.49352.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g15570 | Ser/Thr protein phosphatase family protein, putative, expressed | 2.0299246 | up | 1.8765 | down |

| Os.5690.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g46760 | protein phosphatase 2C, putative, expressed | 2.3383155 | down | 1.2241448 | up |

| Transporters | ||||||

| Potassium transporter | ||||||

| Os.11262.2.S1_x_at | LOC_Os04g32920 | HAK1 | 1.6623486 | up | 1.3617935 | down |

| OsAffx.3292.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os03g21890 | potassium transporter, putative, expressed | 1.89058 | down | 1.1096667 | up |

| Os.38354.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os01g11250 | potassium channel KAT1, putative, expressed | 1.7454123 | down | 1.2604069 | up |

| ABC transporter | ||||||

| Os.10975.1.S1_at | LOC_Os11g39020 | ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein, putative, expressed | 5.1243515 | down | 1.092812 | up |

| Os.11616.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g36570 | ABC1 family domain containing protein, putative, expressed | 3.1116002 | down | 1.6521326 | up |

| Sodium transporter | ||||||

| Os.19896.2.S1_x_at | LOC_Os06g48800 | OsHKT2;4 - Na+ transporter, expressed | 6.008856 | down | 1.069684 | down |

| Os.57530.1.S1_x_at | LOC_Os01g34850 | OsHKT2;3 - Na+ transporter, expressed | 3.2722178 | down | 1.0480005 | down |

| Sulfate transporter | ||||||

| Os.18597.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g09930 | sulfate transporter, putative, expressed | 10.878617 | down | 1.1813235 | down |

| Os.10754.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g06520 | sulfate transporter, putative, expressed | 2.6930013 | down | 2.0457704 | up |

| Lipid transporter | ||||||

| Os.20387.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g14642 | LTPL107 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family protein precursor, expressed | 3.3959548 | up | 1.7493165 | down |

| Os.24103.1.A1_at | LOC_Os07g18990 | LTPL40 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family protein precursor, expressed | 2.3825653 | up | 1.1182239 | down |

| Os.36913.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g40530 | LTPL146 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family protein precursor, expressed | 3.1217232 | down | 5.417366 | up |

| Os.38235.2.S1_at | LOC_Os04g52260 | LTPL124 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family protein precursor, expressed | 5.2148013 | down | 6.255761 | up |

| Os.6838.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g40510 | LTPL144 - Protease inhibitor/seed storage/LTP family protein precursor, expressed | 3.2739449 | down | 7.4096494 | up |

| Peptide transporter | ||||||

| Os.32686.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g65110 | POT family protein, expressed | 2.889076 | up | 3.8825707 | down |

| Os.34161.1.S1_at | LOC_Os06g03700 | oligopeptide transporter, putative, expressed | 2.7034025 | up | 3.4326303 | down |

| Os.45923.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g37590 | peptide transporter PTR2, putative, expressed | 2.8099432 | down | 3.7542121 | down |

| Os.52974.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g50940 | peptide transporter PTR2, putative, expressed | 2.4533195 | up | 3.851256 | down |

| Os.9303.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g46460 | peptide transporter PTR2, putative, expressed | 5.1835947 | down | 19.712648 | up |

| Metal transporter | ||||||

| Os.1193.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g43070 | ammonium transporter protein, putative, expressed | 3.5124 | down | 1.6415328 | up |

| Os.26807.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g12210 | aluminum-activated malate transporter, putative, expressed | 4.311443 | up | 1.5286913 | down |

| Os.27805.1.S1_at | LOC_Os03g48000 | CorA-like magnesium transporter protein, putative, expressed | 7.6011996 | down | 2.93601 | up |

| Os.54471.1.S1_at | LOC_Os08g10630 | metal cation transporter, putative, expressed | 2.1970346 | down | 1.2260257 | up |

| Os.6864.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g61070 | heavy metal-associated domain containing protein, expressed | 3.188327 | up | 2.0711086 | down |

| Transcription factor | ||||||

| Myb TF | ||||||

| Os.49829.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g40530.1 | MYB family transcription factor, putative, expressed | 4.539408 | down | 2.2878835 | up |

| Os.10901.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os08g06110 | MYB family transcription factor, putative, expressed | 26.226946 | down | 1.342114 | up |

| Os.18955.1.S1_at | LOC_Os06g51260 | MYB family transcription factor, putative, expressed | 16.628183 | down | 1.4534045 | up |

| Os.3340.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os06g24070 | myb-like DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 8.957898 | down | 13.670861 | up |

| Os.8149.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g46030 | MYB family transcription factor, putative, expressed | 42.721607 | down | 1.0932941 | up |

| Zinc finger TF | ||||||

| Os.12805.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g41560 | B-box zinc finger family protein, putative, expressed | 12.830358 | down | 10.982284 | up |

| Os.23145.1.S1_at | LOC_Os08g03310 | zinc finger family protein, putative, expressed | 5.089536 | down | 3.4042013 | up |

| Os.3399.1.S1_at | LOC_Os09g06464 | CCT/B-box zinc finger protein, putative, expressed | 9.954306 | down | 2.2954476 | up |

| Os.4184.1.S1_at | LOC_Os02g15350 | dof zinc finger domain containing protein, putative, expressed | 6.1414027 | up | 5.342717 | down |

| Os.10583.1.S1_at | LOC_Os06g04920 | zinc finger family protein, putative, expressed | 14.976689 | up | 6.472622 | down |

| bZIP TF | ||||||

| Os.16025.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os06g39960 | bZIP transcription factor domain containing protein, expressed | 3.1624238 | down | 1.4623934 | down |

| Os.12134.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g45810 | homeobox associated leucine zipper, putative, expressed | 16.334263 | down | 1.1461058 | up |

| Os.27388.1.S1_s_at | LOC_Os10g01470 | homeobox associated leucine zipper, putative, expressed | 2.4151278 | up | 3.0738394 | down |

| HLH TF | ||||||

| Os.19229.1.S1_a_at | LOC_Os03g43810 | helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 2.5253093 | down | 1.4796277 | up |

| Os.27587.1.S1_at | LOC_Os10g40740 | helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 2.0795941 | down | 1.2293708 | down |

| Os.4548.1.S1_at | LOC_Os04g52770 | helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 3.0124726 | up | 3.9773142 | down |

| Os.46956.1.S1_at | LOC_Os01g50940 | helix-loop-helix DNA-binding domain containing protein, expressed | 9.380022 | down | 3.0063295 | up |

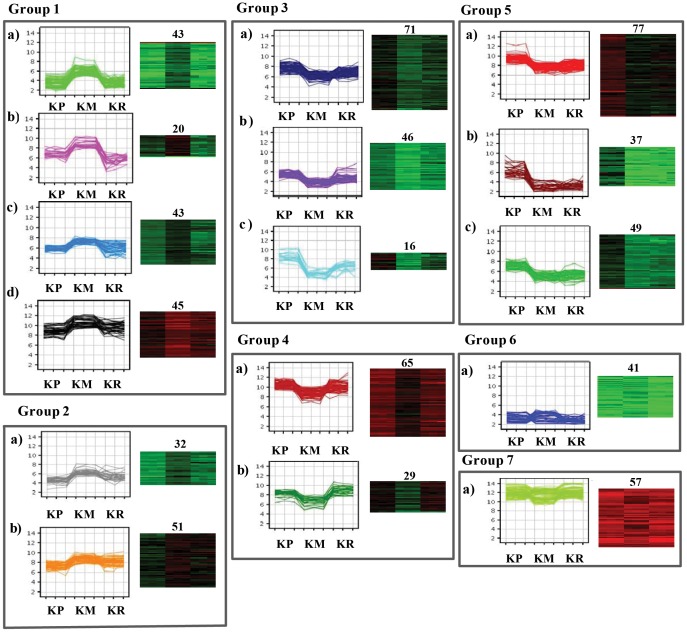

K-means Cluster Analysis

To elucidate potassium-specific gene expression profiles, co-regulated genes were further analysed by K-Means Cluster analysis. Generally, K-means cluster analysis is based on the assumption that genes involved in either a similar function or a common pathway will have similar expression profiles and can likely to be grouped together. The analysis was performed for genes that were significantly expressed during potassium starvation. A total of 722 DEG under potassium-deficient conditions were clustered into 16 primary clusters and were then grouped into 7 different groups based on significant changes in expression pattern (Figure 6). Group 1, the largest group, consisted of 151 genes that were further divided into four sub-groups (i.e. 1A, 1B, 1C and 1D). All the genes in this group exhibited high expression levels under potassium-deficient conditions (KM), while their expression was low in both potassium-sufficient (KP) and potassium resupply (KR) conditions. Stress-related genes such as oxidoreductase, GST, heat shock protein and a few genes related to metabolism such as oligosaccharyl transferase, terpene synthase, ribulose 1,5 biphosphate were included in this group. 32 and 51 genes from group 2 a and 2 b, respectively, showed similar expression pattern as group 1 under KM condition, but they exhibited slightly elevated expression during potassium resupply (KR) compared to K+ plus (KP) conditions. This group included genes related to plant growth, plant development, and transcription factors. In group 3 (133 genes) and group 4 (94 genes), the overall expression pattern of genes was similar, but the difference in expression levels of genes under KM and KR was greater in group 4 as compared to group 3. Group 3 included 133 genes; all of them showed elevated expression in KP and low expression in KM. After resupply of potassium, they regained expression levels comparable to KP. Most of the photosynthesis, signal transduction, and transporter-related genes along with flavonol synthase, expansin precursor, and RNA polymerase sigma factor, comprised group 3 and 4. 163 genes of group 5 had elevated expression in K+-sufficient (KP) conditions and constant expression in K+-deficient (KM) and K+-resupply condition (KR). CHIT10, WRKY 50, WRKY 65, a MYB family transcription factor were also contained in this group. Group 6 genes were not differentially expressed in any of the three conditions tested and maintained a constant low level of expression. On the other hand, genes placed in group 7 showed high expression in all three conditions.

Figure 6. K-means cluster analysis of differentially expressed genes.

All the genes categorized into 20 clusters and again grouped together to make 7 groups, based on their similar expression patterns but different expression amplitudes. The normalized log transformed signal values were plotted for all the conditions. The number of genes in the clusters is indicated upper side of the heatmap.

Genes Involved in Metabolism

A large number of DEG was found to be involved in metabolic processes, particularly primary metabolism (carbohydrate and lipid), secondary metabolism, protein and nucleic acid metabolism. Potassium is a crucial ion for plants as it acts as a cofactor for various enzymes in metabolic pathways [10]. From this gene expression analysis, many genes related to metabolism showed altered expression in potassium-deficient conditions (KM). Upon resupply of potassium, the expression was restored to similar levels as seen in K+-sufficient (KP) conditions. As mentioned earlier, 18% of differentially regulated genes were involved in various metabolic and biosynthetic processes. Among these 18% of genes, 30 genes are related to carbohydrate metabolism, of which 10 genes were downregulated in KM condition and upregulated upon external resupply of potassium (KR). Another 14 genes showed the reverse trend of upregulation in KM condition and downregulation in KR condition (Table S5). Carboxyvinyl-carboxyphosphonate phosphorylmutase (LOC_Os12g08760) showed downregulation in potassium-deficient conditions, as well as glyoxalase (LOC_Os07g06660), pyruvate kinase (LOC_Os11g10980), and lactate/malate dehydrogenase (LOC_Os07g43700). UDP-glucoronosyl and UDP-glucosyl transferases (LOC_Os01g08440, LOC_Os02g11640), and a glycosyltransferase (LOC_Os01g07530) showed downregulation in both deficient and resupply condition. Phosphoglycerate kinase (LOC_Os06g45710) and indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase (LOC_Os09g08130) were up- and downregulated in KM and KR condition, respectively. Alpha-amylase (LOC_Os09g28430, LOC_Os02g52700) showed the highest expression in deficient condition (Table 2).

Eleven of the lipid metabolism-associated genes were downregulated in potassium-deficient conditions and showed elevated expression in resupply conditions (Table S5). Beta-amylase (LOC_Os03g04770), omega-3 fatty acid desaturase (LOC_Os03g18070), and lipase (LOC_Os04g56240) exhibited low expression in deficient condition and high expression upon resupply. Three genes related to lipid metabolism showed the reverse trend and were upregulated in KM and downregulated in KR condition. A number of other genes related to metabolism such as transferases (10 genes), dehydrogenases (5 genes) other kinases/phosphatases (4 genes) were also differentially regulated (Table S5).

Genes Involved in Secondary Metabolism

Eleven K+-responsive genes related to secondary metabolism were also downregulated upon KM treatment and upregulated in KR conditions. This category included many enzymes such as two polyprenyl synthetases (LOC_Os05g50550, LOC_Os04g56230) and a protein containing a FAD-binding domain (LOC_Os02g51080). Seven genes encoding flavonol synthase (LOC_Os10g40934), dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (LOC_Os07g41060), and laccase precursor protein (LOC_Os12g15680, LOC_Os10g20610) showed upregulation in KM conditions and downregulation in KR conditions (Table 2).

Nucleic Acid and Protein Metabolism

In potassium-deficient conditions, the majority of DEG not only belonged to carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, but several genes were identified that are annotated as being involved with nucleic acid and protein metabolism. Among 22 genes associated with nucleic acid metabolism, only 8 showed downregulation in KM condition and elevated expression in KR condition, whereas the remaining exhibited reversed expression pattern (Table S5). Transcripts presenting this profile encoded, for example, two AMP deaminases (LOC_Os05g28180, LOC_Os07g46630); endonuclease/exonuclease/phosphatase domain containing (LOC_Os01g58690); RNA polymerase sigma factor (LOC_Os08g06630, LOC_Os05g51150); and 3′–5′ exonuclease (LOC_Os04g14810). Most of the protein metabolism-related transcripts shown in Table 2 were downregulated upon potassium treatment, and their expression increased upon KR treatment. The putative C-terminal processing peptidase OsCttP3 (LOC_Os06g21380), the putative prolyl oligopeptidase OsPOP9 (LOC_Os04g47360), aspartic proteinase nepenthesin-2 (LOC_Os06g03120), and 8 other genes were included in this category.

Genes Related to Photosynthesis and Plant growth

Photosynthesis is a process by which green plants capture light energy to synthesize organic compounds from carbon dioxide and water. Seventeen photosynthesis-related genes were expressed differentially under KM and KR conditions. Surprisingly, all 17 genes were downregulated in KM condition and upregulated in KR condition. Some of these genes (9) encoded chlorophyll a/b binding protein, photosystem I reaction centre subunit (LOC_Os09g30340), and magnesium-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase (LOC_Os01g17170) (Table 2). Sixteen transcripts (9 upregulated and 7 downregulated) that showed altered expression in potassium-deficient conditions relative to their expression under normal growth conditions were related to plant growth and development. The expression of these genes was reversed upon resupply of potassium (Table S5).

Transcription Factors and Related Genes

In higher plants, gene expression in response to various stresses is regulated by transcription factors [26]–[28]. In many biological pathways, transcription factors are considered to be master regulators, since they can control the expression of suites of multiple genes at a given time in response to a particular stress condition. Our microarray results showed that 55 genes encoding transcription factors were induced under potassium deficiency (Table S5). Among the 55 induced genes, 21 genes belong to the zinc finger family and 13 to the MYB gene family. Another 4 genes are bZIP (basic region/leucine zipper motif) transcription factors, and 4 other genes are HLH (Helix-loop-Helix) transcription factors, 2 are annotated as ethylene-responsive (ERF) transcription factors. Of the 19 zinc finger transcription factors, only 5 were upregulated in KM condition and downregulated upon KR condition, whereas the remaining 14 showed the reverse expression pattern. Similar expression patterns were observed for all other categories of transcription factors. Some of the MYB family transcription factors (LOC_Os02g46030, LOC_Os06g51260, LOC_Os08g06110) were strongly downregulated under deficient conditions and upregulated upon resupply of potassium (Table 2).

Transporters

Potassium deficiency affected the expression of a large number of transcripts encoding transporters representative of several distinct protein families. Similar to transcription factors, some transporters also showed downregulation under potassium deficiency and upregulation upon resupply. Of the 40 differentially expressed transporters, 9 were metal transporters; 7 were peptide transporters; and 5 were lipid transporters. In this study, sodium transporters (OsHKT2;3 and OsHKT2;4 2 ), sulphate transporters (2 genes), and ABC transporters (2 genes) were highly downregulated in KM conditions and upregulated under KR conditions (Table 2). Thirteen other transporters (annotated as aquaporins, MATE efflux transporters, and AAA-type ATPases) also displayed similar expression pattern as described above. Surprisingly, we did not find any potassium transporters that showed differential expression in our microarray data with the criteria of more than 2-fold change. But when the fold change criterion was reduced to 1.5, two potassium transporters (OsHAK1), one potassium channel (OsKAT1) and one putative potassium transporter were found to be differentially expressed (Table S6).

Signal Transduction Related Genes

Based on the available literature for analyses of gene expression changes in response to various nutrient deficiencies, several proteins involved in signal transduction networks such as calcium sensors, kinases, and phosphatases were found to be differentially regulated under those conditions [24], [25], [29], [30]. Kinases and phosphatases are involved in a large number of distinct signaling pathways, such as the signal transduction pathways controlling cell growth, differentiation, and death. In our analysis, 31 differentially expressed genes were classified as signal transduction-related genes. Three CIPKs (CIPK7, CIPK8 and CIPK29) and three MAPKs display distinct patterns of downregulation and upregulation in potassium-deficient and resupply conditions, respectively (Table S5). Among the other signaling related genes, 6 phosphatases, 2 PP2Cs (LOC_Os01g46760, LOC_Os04g33080), and a phosphocholine phosphatase exhibited low expression under KM condition and elevated expression under KR condition, whereas one of the Ser/Thr protein phosphatases and two of the pyrophosphatases exhibited the reverse expression pattern. Some of the kinases such as a CDPK (LOC_Os03g48270) and the serine/threonine protein kinase SNT7 (LOC_Os05g47560) also showed downregulation in KM condition, but BRASSINOSTEROID INSENSITIVE 1 (LOC_Os11g31530) was upregulated 12-fold under KM conditions and down regulated 10-fold under KR conditions (Table 2).

Stress Related Genes

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are known to be involved in signaling pathways specific to low potassium stress conditions [31], [32]. Oxidoreductase and glutathione S-transferase (GST) play important roles during oxidative stress in plants [33]. In our study, a total of 50 genes grouped as stress-related were differentially expressed under low potassium conditions. These included 28 upregulated and 22 downregulated genes. Among these, 5 oxidoreductase genes and 4 GST were identified that showed upregulation in KM conditions and downregulation in KR conditions (Table S5), which we view as unsurprising given the well established role of potassium in stress responses [34]–[36]. A total of 11 heat stress-related genes (HSPs) and 5 dehydration-related genes were identified. Most of the HSPs (9 genes) were downregulated in potassium-deficient conditions, and the expression pattern was reversed upon resupply of potassium. Other drought-responsive genes showed a qualitatively similar expression pattern (Table S2).

Cell Wall and Cell Death Related

Among 12 cell wall-related genes identified in this study, 9 genes encoding peroxidases (LOC_Os07g48050, LOC_Os01g73170, LOC_Os03g13210), expansin (LOC_Os01g60770), and alpha-N-arabinofuranosidase (LOC_Os11g03780) were upregulated, and another 2 peroxidases (LOC_Os10g02070, LOC_Os07g47990) and an expansin (LOC_Os10g40710) were down regulated during potassium deficiency and showed reversal of expression upon resupply (Table 2).

Cell death-related transcripts constituted only a small category in the microarray results. This category contained 7 genes, including 5 genes encoding ubiquitin, which mostly showed upregulation under low potassium conditions (KM) (Table S5).

Phytohormones and Defense Related Genes

Changes in potassium supply affect the transcription of genes related to phytohormones like jasmonic acid (JA), auxin, gibberellin and others [5], [37]. Seven genes were found to be related to auxin, such as OsSAUR21, OsSAUR53, OsIAA2 (Table 2, S5). Interestingly, two jasmonic acid-related genes, lipoxygenase (LOC_Os02g10120) and jacalin-like lectin (LOC_Os12g14440) were upregulated 16- and 65-fold in potassium-deficient conditions, respectively. Their expression levels declined rapidly after resupply. Two GA-related genes also showed similar expression patterns as the jasmonic acid related genes, however GID1, exhibited the opposite expression pattern.

Thirteen genes related to plant defense were also differentially expressed, 7 genes were downregulated in KM condition and upregulated upon resupply (KR). The remaining 6 genes had a reverse expression pattern (i.e. upregulated in KM and downregulated in KR conditions). This category include genes encoding glycosyl hydrolase (LOC_Os05g31140, LOC_Os01g71340), cysteine protease 1 (LOC_Os03g54130), thaumatin (LOC_Os03g45960, LOC_Os03g46070), and WIP3 (LOC_Os11g37950).

cis-Regulatory Element Analysis of Potassium Deficiency Responsive Genes

When analysing the expression of a group of genes that respond similarly to a particular condition, it is anticipated that these genes might have some common features or elements driving their expression. The promoters of co-expressed genes might share some common regulatory elements or be regulated by a common set of transcription factors. Thus, the identification of shared cis-regulatory elements in the promoter regions of genes co-expressed in response to altered levels of potassium availability could provide new insights into the transcriptional regulatory networks that are triggered by potassium deficiency in plants. To identify common cis-regulatory elements, 1 kb regions directly upstream of potassium-responsive genes in Arabidopsis and rice were analysed in PLACE database [38], [39]. Genes that exhibited high levels of expression under potassium deficiency in this study and earlier studies on Arabidopsis including CIPK9 [40], HAK5 [41], peroxidase, glycosyl hydrolase, AP2 domain-containing transcription factor, rice alpha-amylase, glycosyl hydrolase, peroxidase, potassium transporter HAK1, GST, dehydration stress-induced protein, and ethylene-responsive transcription factor were compared. A total of 31 common cis-regulatory elements were found, including ABRELATERD1 (ACGTG), ARR1AT (NGATT), CAATBOX1 (CAAT), DOFCOREZM (AAG), GATABOX (GATA), GT1CONSENSUS (GRWAAW), POLLEN1LELAT52 (AGAAA), TAAAGSTKST1 (TAAAG), WRKY71OS (TGAC) and many others that were prominently present in the 1 kb putative regulatory regions of the aforementioned genes. A list of all of the 31 cis-regulatory elements with their sequences is provided in Table S7.

Comparative Analysis of Rice and Arabidopsis in Potassium and Other Nutrient Deprivation

Transcriptome data from this study were compared to earlier published results on the transcriptome response to potassium deficiency in Arabidopsis and rice, particularly an earlier transcriptomic profile of 2 week old rice roots grown under potassium-deficient conditions [37]. However, the transcriptome profile of potassium-deficient plants is comparatively far better characterized in Arabidopsis, where both two week old shoot and root tissues were analyzed under potassium deprivation [5], [42]. We compared the dataset; we obtained from seedlings grown under potassium-deficient conditions under these two published transcriptome datasets. In earlier reports, far fewer genes were reported to be differentially regulated with a 2-fold or greater expression change in response to potassium deficiency in both rice (722 in rice whole seedling [this study] versus 356 in rice root [37]) and Arabidopsis (119 in shoot, 299 in root [5]) (Table 3). In an attempt to identify the similarities and differences among potassium-responsive genes in rice and Arabidopsis, we categorised and compared 356 DEG from rice root [37] with 722 DEG from whole rice seedling (this study) and 418 genes from Arabidopsis shoot and root transcriptome [5] (Figure S1). This comparative analysis revealed that the majority of DEG was related to metabolism and signal transduction in response to potassium deficiency in both rice and Arabidopsis (Figure S1). The percentage of genes related to defense and cell wall were significantly greater in number in Arabidopsis than rice. In whole rice seedlings, the number of differentially expressed transcription factor genes were greater (this study, Figure S1) compared to the roots of potassium-deficient rice seedlings [37]. The present transcriptome profile of potassium-deficient rice seedlings was further compared to transcriptome profiles of rice under other nutrient deprivation (i.e. nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron) (Figure S2). From the above studies, it was inferred that genes differentially expressed in response to deprivation of distinct nutrients were associated with various metabolic processes and stress adapatations and were classified as transporters, transcription factors, and signal transduction components. This suggest that there might be a functional overalap of these genes in responses to deprivation of nutrients other than potassium in both rice and Arabidopsis.

Table 3. Differentially expressed genes from present microarray data and data obtained from 2 week K+-starved Arabidopsis shoot-root (Armengaud et al. 2004), roots of rice plants after 6 h, 3 days and 5 days (Ma et al. 2012).

| Study | (Armengaud et al. 2004) | (Ma et al. 2012) | Our data |

| Organ | Arabidopsis shoot and root | Rice root | Rice seedling |

| Cutoff value | FDR%<1 | Fold Change ≥2 and P-value ≤0.05 | Fold Change ≥2 and P-value ≤0.05 |

| Regulated Gene | 116 and 299 | 356 | 722 |

Relationship of Potassium Ion Response Related Genes with Abiotic Stresses

We analysed potassium responsive DEGs (mainly related to metabolism, signal transduction and stress) under abiotic stresses like cold, drought, heat and salt stress, using Genevestigator database for their transcript status. Most of the genes showed differential expression pattern under these stresses. Metabolism related carboxyvinyl-carboxyphosphonate phosphorylmutase (LOC_Os12g08760), heparanase (LOC_Os06g08090), UDP glucoronosyl (LOC_Os01g08440) showed downregulation in all stresses except heat stress. But phosphoglycerate kinase (LOC_Os06g45710) and beta-amylase (LOC_Os03g04770) were upregulated in all stress conditions (Figure S3A). Genes related to signal transduction, such as OsCML14 (LOC_Os05g50180) and BRI I, (LOC_Os11g31530) showed an upregulation in both cold and drought stresses whereas no differential expression was found in heat and salt stresses. MAP3K4 (LOC_Os01g50370) expression was elevated in response to above mentioned four stresses. In contrast, EF-hand containing protein (LOC_Os09g28510) was showing downregulation in stressed state (Figure S3B). Early responsive to dehydration protein (LOC_Os12g43720), oxidoreductase (LOC_Os11g07930), HSP (LOC_Os2g54140), HSF (LOC_Os02g35960) genes were downregulated in cold and heat stresses while upregulated under drought stress. Dehydrin (LOC_Os02g44870) showed elevated expression under cold, drought, heat and salt stresses whereas 2-oxoglutarate (LOC_Os10g40960) and oxidoreductase (LOC_Os02g53510) were downregulated under these conditions (Figure S3C).

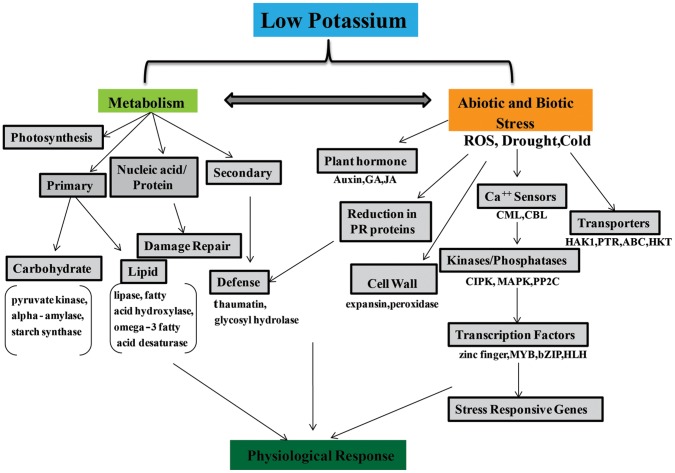

Discussion

Nutritional deficiencies alter the physiology and metabolism of plants during both short-term and long-term periods of growth. In response to nutrient deficiency, plants activate a plethora of genes and gene networks encoding a large number of proteins involved in acclimation and adaptation. Significant research has contributed to our understanding of the uptake, distribution and homeostasis of potassium ions in Arabidopsis by employing advanced tools for genetics, biochemistry, cell biology, and physiology. Our knowledge of adjustment and adaptation to short-term and long-term nutrient deficiency is still insufficient to establish a basic model of how plants manage to thrive physiologically despite nutrient deficiencies in soil. As mentioned in the introduction, research related to potassium nutrition in plants has drawn the attention of several leading research groups who seek to enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of plant tolerance to potassium deficiency. In this study, we have contributed to this effort by performing detailed transcriptomic profiling of whole rice seedlings exposed to short-term (5 days) potassium deprivation.

It is quite possible that different plant species might have different mechanism to absorb, transport, distribute, and utilize potassium [4], [6], [7], [43]–[45]. Biomass is one important parameter to measure plant growth under low nutrient conditions, and it is a significant criterion to judge the crucial role played by particular nutrient in plant growth and development.

In order to complement our transcriptomic analysis of rice seedlings, we also performed a physiological experiment to determine the growth symptoms of potassium deficiency. The experimental results indicate that rice grew significantly more poorly under low potassium conditions than it did under higher concentrations of potassium that we believe are more reflective of optimal growth conditions for rice. This effect is clearly seen in the qualitative and quantitative assessment of seedling biomass under both conditions (Figure 1A, B, C). At the molecular level, the content of potassium ions in plants grown in low potassium media was also appreciably lower than the potassium content of plants grown in media with sufficient levels of potassium, which demonstrates that rice seedlings are indeed able to take up higher levels of potassium when external levels are sufficiently higher and further establishes a direct link between potassium supply and plant growth (Figure 1D). Similar results were previosuly described in Arabidopsis plants starved of potassium [5]. Analysis of the growth of Arabidopsis under long-term potassium starvation (14 days) by Armengaud et al. (2004) [5] revealed chlorosis (bleaching) of older leaves, as well as a reduction in lateral root growth of seedlings. In contrast to these reported results in Arabidopsis, we observed an obvious reduction in the growth of rice seedlings by the fifth day of growth on low potassium containing media without any significant signs of chlorosis or bleaching of seedling leaves. We also observed a very similar, severe impairment of growth in rice seedlings maintained on potassium-deficient media for longer period of time (i.e. 14 days; data not shown). After observing growth differences of rice seedlings exposed to short-term or long-term potassium deprivation, we decided to investigate gene expression profiles under short-term (5 days) potassium starvation.

During the preparation of this manuscript, we discovered a report on the transcriptome profile of rice roots deprived of potassium [37]. The major difference between this study and our study is that we chose to use whole seedlings rather than just roots. Moreover, this study is more comprehensive due to our transcriptional profiling of seedlings resupplied with potassium after short-term potassium deprivation. These growth conditions closely mimicked a previous study by Armengaud et al. 2004 [5]. The usage of higher level of stringency (i.e. 2-fold or greater change) and false discovery rate (FDR) in the present study also strengthens the reliability of our data on differential gene expression. Despite several differences, some of our findings are consistent with differentially expressing genes previously reported by Ma et al. 2012 [37].

The most significant contribution of the present work is the identification of genes implicated in the growth and development of rice seedling exposed to the short-term stress of potassium deficiency and the resupply of potassium to deprived seedlings. This study provides a platform for the investigation of the mechanisms of regulatory responses to low potassium conditions. From our microarray analysis, a large number of genes (722) were found to be differentially expressed during potassium deprivation and resupply (1867 DEG). Only 307 of the affected genes, however, exhibited reversal of gene expression (i.e. restoration of comparable expression levels as seen during optimal growth conditions) upon resupply of potassium to the deficient media (Figure 2B), therefore this study clearly identifies a subset of the differentially expressed genes that are specifically expressed only during potassium deprivation. This difference in expression is also seen in the results of our PCA analysis, where the three biological replicates of the potassium resupply treatment were more similar to those grown with sufficient levels of potassium (Figure 2A). This recognizable difference in gene expression between the plants during potassium deficient conditions and following resupply highlights the flexibility of biological pathways to adapt quickly as per changes in the environment. Through this study, we reveal adaptive responses of plants to fluctuations in potassium ion concentration. As previously reported, genes involved in various processes like primary and secondary metabolism, ion transport, signal transduction, and hormone signaling were linked to potassium deficiency [5], [44]–[47]. We have also identified differentially expressed genes related to carbohydrate metabolism, carboxyvinyl-carboxyphosphonate phosphorylmutase, glyoxalase, lactate/malate dehydrogenase, phosphoglycerate kinase, UDP-glucosyl transferase and many other enzymes and biological processes (Table 2). Many genes related to carbohydrate metabolism have also been reported to play important roles in response to phosphorus deficiency in rice roots and potassium deficiency [46], [48]. One of the genes identified in this study, UDP-glucosyl transferase, was also found to be influenced by iron toxicity in rice [49]. Similarly, alpha amylase transcript that shows the greatest magnitude of upregulation in response to potassium deficiency was also reported to be involved in starch hydrolysis [50].

Our microarray data suggests a number of proteins involved in diverse aspects of carbohydrate metabolism were differentially regulated and thereby indicates that potassium deficiency has widespread effects on carbohydrate metabolism. Carbohydrate metabolism directly impacts plant biomass and photosynthetic yield and, based on our findings, could be a significant component of the stress imposed by potassium deprivation.

Lipases are enzymes involved in the cleavage of lipids and are crucial components of lipid metabolism responsible for the mobilization of lipids during stress conditions. In this study, several lipases were identified that exhibited downregulation during potassium deprivation. In Arabidopsis, Armengaud et al. (2009) [5] reported the involvement of lipases and their similar differential expression in potassium deficiency treatments.

Based on earlier physiological analysis of growth symptoms under potassium deficiency, photosynthesis was identified as one of the major processes directly affected by potassium deficiency [51]–[53]. Photosynthesis serves as the major energy source of plants, and its efficiency is reduced under nutrient deficiencies [54]. The efflux of potassium ion from guard cells causes decreased stomatal conductance and thereby reduces rates of photosynthesis as a tradeoff for reduced water loss [51], [55]–[58]. In our differential gene expression analysis, we have identified several genes involved in photosynthesis. In particular, chlorophyll A–B binding protein and magnesium-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester cyclase were downregulated in KM conditions and strongly upregulated upon KR conditions. Similarly, several genes involved in jasmonic acid (JA), auxin, ethylene, and gibberellin signaling pathways are known to be directly influenced by potassium deficiency in plants [5], [37], [59].

With extensive research in the field of stress biology in plants, it is widely appreciated that many of these stresses are inter-related and produce similar secondary messenger molecules such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), calcium (Ca2+), and others [32], [54], [60]. Research in Arabidopsis pertaining to deprivation of multiple nutrients (N, S, P, K, Fe and others) suggests the activation of signaling pathways implicated in other abiotic stresses such as drought or toxic ion exposure [32], [61]. Presumably due to the interconnected nature of diverse plant stresses, plants grown under low potassium conditions have also been shown to be particularly susceptibile to drought and cold stress [9], [34], [36]. Moreover, many of the abiotic or biotic stresses affect metabolism and hence affect growth [62]. Different cellular processes like growth, photosynthesis, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism, osmotic homeostasis, protein synthesis are affected by both biotic and abiotic stresses [63]–[66].

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a byproduct of normal cell metabolism in plants. Accumulation of ROS is damaging to cells, however ROS also act as important signaling molecules. The balance between production and detoxification of ROS is tightly regulated by many proteins and enzymes [67]–[69]. ROS are generated as a signal of several biotic and abiotic stress conditions [68], [70]–[72]. ROS level were also elevated in response to deficiency of several nutrients (N, S, P, Fe), and ROS are a known signal of potassium starvation in roots [31], [32], [45], [73]. Under potassium-deficient conditions, many ROS related genes such as oxidoreductase and glutathione S-transferase (GST) are involved in detoxifying the ROS to maintain homeostasis of these molecules in the cytosol. We observed that transcripts encoding these enzymes were upregulated in response to potassium deprivation and subsequently downregulated following resupply of potassium.

Recently in the field of calcium signaling in plants, calcium has often been placed downstream of ROS [26], [31], [32], [40], [74], [75]. In previous reports in Arabidopsis, calcium-binding proteins were described to be differentially regulated in response to potassium starvation conditions [45]. Calcium sensors such as calmodulin (CaM), calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs), CBL interacting protein kinases (CIPKs), and Ca2+-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), were differentially expressed in potassium-deficient conditions [5]. In the rice root transcriptome, OsCIPK29 was found to be downregulated in response to potassium deficiency [37]. Three other CIPKs (OsCIPK7, OsCIPK8, and OsCIPK29) were found to be downregulated under potassium starvation. Their expression increased after resupply of potassium in this study, which suggests that these kinases might be acting as negative regulators of potassium nutrition and signaling in rice. One recently discovered, important aspect of potassium uptake and nutrition that has been elucidated in Arabidopsis is regulation of the high affinity K+ channel AKT1 by physical interactions with the calcium-binding proteins CBL1 and CBL9 and the Ser/Thr kinase CIPK23 in the root to regulate uptake of potassium [24], [25]. The downregulation of two PP2C protein phosphatases in the transcriptomic data suggests that these phosphatases might be acting as counteracting molecules in protein phosphorylation pathways that signal potassium-deficient conditions. Previously, it was reported that several members of the PP2C family are involved in regulating responses to multiple abiotic stresses as well as developmental processes in rice [76]. Some MAP kinases were also differentially regulated in potassium-deficient conditions, which suggest other signaling components are involved in the regulation of potassium starvation responses. MAPKs have also been implicated in both biotic and abiotic stress responses in addition to potassium starvation, development, cell proliferation, and hormone physiology [47], [61], [77], [78]. The involvement of phytohormones like JA and auxin in potassium-deficient conditions was shown earlier by identification of differentially regulated genes in the metabolism or signaling of these phytohormones [5], [37]. Surprisingly, we identified only a few candidate genes involved in JA and auxin metabolism and signaling during potassium-deficient conditions in rice seedling. It is quite possible that the altered expression of these signal transduction, stress and hormone-related genes might also play roles in enabling plants to adapt under low potassium stress conditions in rice.

Genome-wide analysis has led to the identification of a large family of genes encoding K+ transporters/channels in both Arabidopsis and rice [79]–[83]. Moreover, several detailed gene expression profiles by northern blots and RT-PCR analyses identified multiple K+ transporters that are differentially regulated under potassium starvation conditions [19], [61], [84]. However, in this transcriptomic analysis, we could not identify any K+ transporters with at least two fold change in gene expression, in contrast to the findings of Ma et al 2012 [37]. Similar to our findings, two previous reports on transcriptomic responses to potassium starvation in Arabidopsis did not identify many K+ transporters with significant changes in expression [5], [42]. Upon relaxing our analysis stringency to 1.5 fold with FDR, p<0.05, three transporters including HAK1 (LOC_Os04g32920) and KAT1 (LOC_Os01g11250) were identified. OsHAK1 is a member of the KUP/HAK/KT family of putative high-affinity K+ transporters that have been known to be involved in potassium uptake under low potassium conditions [37], [85]. KAT1 is a shaker-type K+ channel that is specifically expressed in guard cells and mediates potassium fluxes for turgor-dependent regulation of the stomatal aperture [86], [87]. As reported earlier, HKT class I transporters conduct Na+ uptake under KM condition in rice. In contrast, class II HKT transporters showed higher permeability for K+ ions. [88]–[93]. In transcriptomic analysis, the expression of sulfate transporters such as SULTR1;2 was found to be altered under potassium-deficient condition in Arabidopsis [5]. Approximately 30 DEG annotated as transporters that conduct molecules other than K+ were identified in this study, and these are believed to be involved in the transport of metals, lipids, sulphate, and other molecules. We identified representatives of ABC transporters, aquaporins, MATE efflux transpirters, and AAA-ATPase-type transporters. The differential expression of these transporters in potassium-deficient conditions might be related to the homeostasis of other molecules to maintain proper osmoticum and neutralize the charges across the membranes and in the cytosol [19], [32], [94].

The identification of fewer K+ transporters led to an argument for the possible existence of post-translational regulatory mechanisms of K+ transporters that direct uptake and distribution of potassium from the root to shoot. In fact, this mode of regulation has been recently discovered in Arabidopsis, where a high affinity K+ channel was regulated by a calcium-mediated phosphorylation-dephosphorylation network in roots [24], [25], [95]. However, no such phosphorylation-dephosphorylation signaling network has been identifed yet in rice. We speculate that similar post-translational modes of regulation are likely present in rice for regulation of K+ transporters during low potassium conditons.

In the present transcriptomic analysis, genes for a large number of transcription factors were differentially regulated in KM condition and their expression returned to baseline levels upon resupply of potassium. The maximum effect was shown by members of the zinc-finger transcription factor family, followed by MYB family transcription factors (Table 2). Zinc-finger family and basic helix-loop-helix (BHLH038, BHLH039, BHLH100, and BHLH101) transcription factors were previously reported to be involved in responses to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis [96]. Multiple reports in plants suggest that MYB family transcription factors regulate a wide range of processes in plants, including biotic and abiotic stress responses, plant growth and development, and secondary metabolite production [97]–[101]. In addition to potassium and iron, this family is also involved in phosphate starvation signaling in both vascular plants and unicellular algae [102].

Regulatory cis elements present in promoter regions are one of the salient aspects of gene regulation and often provide a mechanistic explanation for coexpression of a group of coexpressed genes. Several common cis-regulatory elements have been identified in multiple genes regulated similarly at transcriptional level [103]. Upon analysis of cis-regulatory elements in some of the highly differentially expressed genes in the present study, we found that they contained previously identifed drought responsive, sugar responsive, and light responsive regulatory cis-elements including ABRELATERD1, ACGTABOX, GT1CONSENSUS, GATABOX and others [104]–[107]. Interestingly, an earlier study concluded that ABREs functions Ca2+-responsive cis-elements in response to calcium transients induced by biotic and abiotic stresses [108]–[110]. Also the expressions of many potassium transporters and channels (KCO) have been shown to be activated by cytosolic Ca2+ [111]. The TAAAGSTKST1 element was found in promoter of the StKST1 gene encoding a K+ channel, and this gene is a known target site for trans-acting StDof1 protein controlling guard cell-specific gene expression [112]. Thus, the presence of these cis-regulatory elements in the promoter sequences of genes involved in nutrient stress might be associated with several abiotic and biotic stresses that lead to changes in the expression of signal transduction components and might also regulate signaling pathway crosstalk to enable plants to acclimatize to a wide range of conditions. Despite the presence of several common cis-regulatory elements in the promoters of highly differentially expressed genes under potassium deprivation, we could not identify a motif or cis-element specific for potassium responsiveness.

The comparative transcriptome analysis of rice and Arabidopsis (Figure S1, S2) suggests a common regulatory mechanism for genes whose expression is highly dependent on potassium availability. Such genes are implicated in a variety of cellular processes including metabolism, molecular transport, transcriptional regulation and signal transduction. We believe the concerted interplay of this diverse suite of genes coordinates plant adaptation to potassium starvation.