Abstract

Background

Enzyme end-product inhibition is a major challenge in the hydrolysis of lignocellulose at a high dry matter consistency. β-glucosidases (BGs) hydrolyze cellobiose into two molecules of glucose, thereby relieving the product inhibition of cellobiohydrolases (CBHs). However, BG inhibition by glucose will eventually lead to the accumulation of cellobiose and the inhibition of CBHs. Therefore, the kinetic properties of candidate BGs must meet the requirements determined by both the kinetic properties of CBHs and the set-up of the hydrolysis process.

Results

The kinetics of cellobiose hydrolysis and glucose inhibition of thermostable BGs from Acremonium thermophilum (AtBG3) and Thermoascus aurantiacus (TaBG3) was studied and compared to Aspergillus sp. BG purified from Novozyme®188 (N188BG). The most efficient cellobiose hydrolysis was achieved with TaBG3, followed by AtBG3 and N188BG, whereas the enzyme most sensitive to glucose inhibition was AtBG3, followed by TaBG3 and N188BG. The use of higher temperatures had an advantage in both increasing the catalytic efficiency and relieving the product inhibition of the enzymes. Our data, together with data from a literature survey, revealed a trade-off between the strength of glucose inhibition and the affinity for cellobiose; therefore, glucose-tolerant BGs tend to have low specificity constants for cellobiose hydrolysis. However, although a high specificity constant is always an advantage, in separate hydrolysis and fermentation, the priority may be given to a higher tolerance to glucose inhibition.

Conclusions

The specificity constant for cellobiose hydrolysis and the inhibition constant for glucose are the most important kinetic parameters in selecting BGs to support cellulases in cellulose hydrolysis.

Keywords: Cellulase, Cellulose, β-glucosidase, Cellobiose, Glucose, Inhibition, Acremonium thermophilum, Thermoascus aurantiacus

Background

Cellulose is the most abundant biopolymer on Earth and has a great potential as a renewable energy source. The enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose, followed by fermentation to ethanol is a promising green alternative for the production of transportation fuels. In nature, cellulose is degraded mostly by fungi and bacteria, which secret a number of hydrolytic and oxidative enzymes [1,2], though fungal enzymes have received most of the attention to date regarding biotechnological applications. The major components of fungal cellulase systems are cellobiohydrolases (CBHs), exo-acting enzymes that processively release consecutive cellobiose units from cellulose chain ends. Endoglucanases (EGs) attack cellulose chains at random positions and work in synergism with CBHs. The hydrolysis of cellulose is completed by β-glucosidases (BGs), which hydrolyze cellobiose and soluble cellodextrins to glucose [3]. BGs can be found in glycoside hydrolase (GH) families 1, 3, 9, 30 and 116 [4,5], and most of the microbial BGs employed in cellulose hydrolysis belong to GH family 3 [6]. Because cellobiose is a strong inhibitor of CBHs, the BG activity in cellulase mixtures must be optimized to overcome the product inhibition of CBHs. The inhibition of BGs by glucose must also be considered because the accumulation of glucose will lead to the accumulation of cellobiose and CBH inhibition. Many BGs are also inhibited by their substrate, and this apparent substrate inhibition is caused by the transglycosylation reaction, which competes with hydrolysis [7,8]. The catalytic mechanism of retaining BGs involves a covalent glucosyl-enzyme intermediate [9], which may be attacked by water (hydrolysis) or by a hydroxyl group of the substrate (transglycosylation). In addition to the substrate, attack by other nucleophiles, such as alcohols, can also lead to transglycosylation [9]. Transglycosylation is under kinetic control, meaning that all cellobiose and transglycosylation products will eventually be hydrolyzed to glucose.

To be economically feasible, the hydrolysis of cellulose must be conducted at a high dry matter concentration, which inevitably results in a high concentration of hydrolysis products, cellobiose and glucose, and makes the product inhibition of enzymes a major challenge in process and enzyme engineering. Several process set-ups have been developed that minimize product inhibition, and bioreactors enabling the continuous removal of hydrolysis products have been constructed [10,11]. The most often applied set-up is simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF), whereby glucose is constitutively removed by fermentation to ethanol. To bypass the use of BGs, yeast strains capable of fermenting cellobiose and cellodextrins have also been generated [12]. A major drawback of SSF is with regard to the different optimal conditions for the enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and yeast fermentation. The optimal temperature for yeast is 35°C, whereas cellulases exhibit the highest activity at temperatures of 50°C or higher. Although both processes can be conducted at each optimal temperature in separate hydrolysis and fermentation (SHF), the enzymes must operate under conditions of severe product inhibition [13]. An alternative process in between conventional SHF and SSF employs the high-temperature partial pre-hydrolysis of cellulose, followed by SSF [14]. Thus, the properties of candidate enzymes, such as temperature optima and tolerance toward inhibitors, must be selected depending on the process set-up.

In this study, we characterize the thermophilic GH family 3 BGs from Acremonium thermophilum (AtBG3) and Thermoascus aurantiacus (TaBG3) [15,16] in terms of cellobiose hydrolysis and glucose inhibition; a well-characterized BG from Aspergillus sp, purified from Novozyme®188 (N188BG), was used for comparison. A literature survey was also performed to identify correlations between the kinetic parameters of cellobiose hydrolysis and glucose inhibition.

Results and discussion

Kinetics of cellobiose hydrolysis

The hydrolysis of cellobiose by BGs, AtBG3, TaBG3 and N188BG was monitored by measuring the initial rates of glucose formation (vGlc). The values of the observed rate constants for cellobiose turnover (kobsCB) were derived from vGlc and the total concentration of enzyme ([E]0) according to

| (1) |

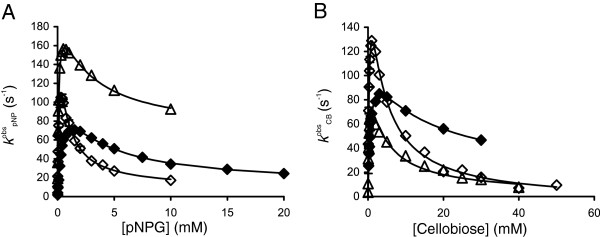

The hydrolysis kinetics of a chromogenic model substrate, para-nitrophenyl-β-glucoside (pNPG), was also studied. In this case, the initial rates of the liberation of para-nitrophenol (pNP) (vpNP) were monitored, and the observed rate constants for pNPG turnover (kobspNPG) were calculated as vpNP/[E]0. All BGs were found to subjected to substrate inhibition using both pNPG and cellobiose as substrates (Figure 1). The substrate inhibition of BGs is a well-known phenomenon that is caused by the competition between water (hydrolysis) and substrate (transglycosylation) for the glucosyl-enzyme intermediate (Scheme 1) [7,8]. The dependency of kobsCB (and also kobspNPG) on the substrate concentration is given by a set of four parameters, catalytic constants kcat(h) and kcat(t) and Michaelis constants KM(h) and KM(t) for hydrolysis and transglycosylation, respectively [17,18].

Figure 1.

Hydrolysis of pNPG and cellobiose by β-glucosidases. Observed rate constants (kobs) for the β-glucosidase-catalyzed turnover of pNPG (panel A) and cellobiose (panel B) at 25°C. β-glucosidases included TaBG3 (◊), AtBG3 (∆) or N188BG (♦). The solid lines are from the non-linear regression according to Equation 2.

| (2) |

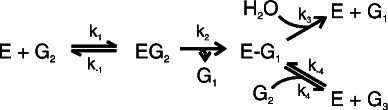

Scheme 1.

Schematic representation of the β-glucosidase-catalyzed turnover of cellobiose. Cellobiose (G2) binds to the enzyme to form a Michaelis complex (EG2) that reacts to form a first product (glucose, G1) and a covalent glucosyl-enzyme intermediate (E-G1). The latter can react with water to produce glucose (hydrolysis) or with cellobiose to produce a trisaccharide, G3, as a second product (transglycosylation). In the case of such model substrates as pNPG or MUG, the chromophore is released as the first product.

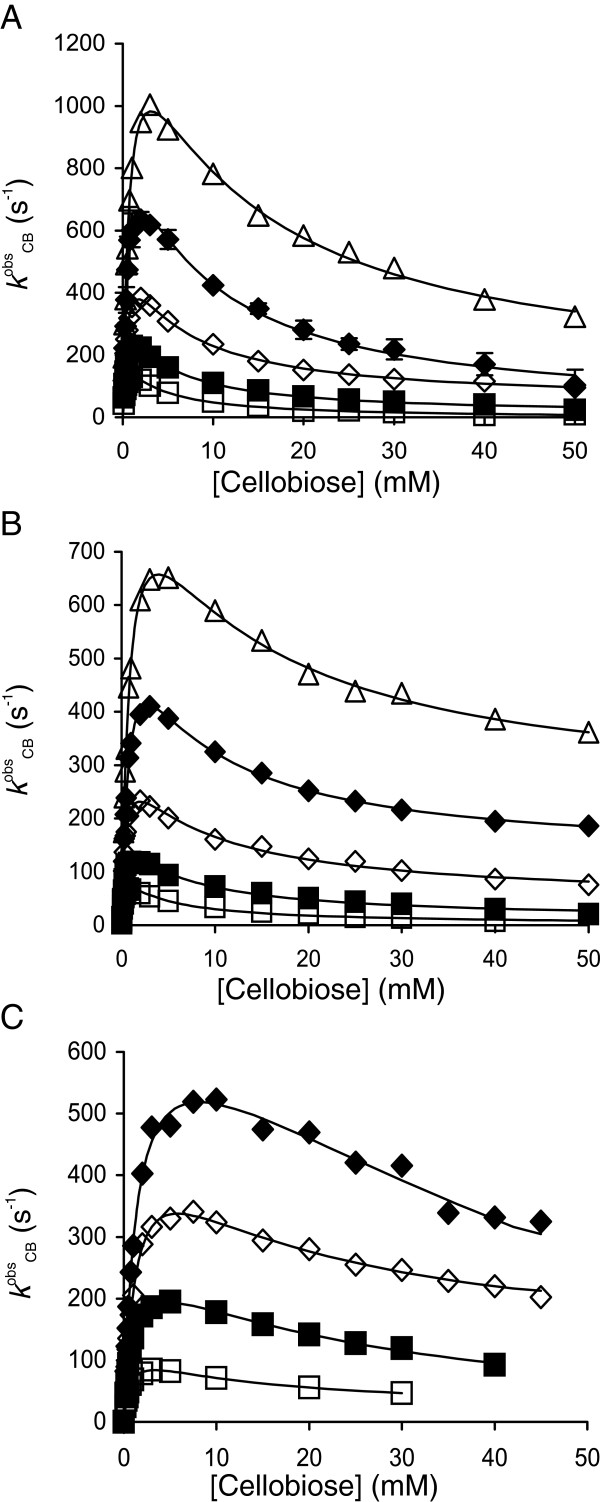

All four parameters in Equation 2 are combinations of the rate constants in Scheme 1[7,8]. The hydrolysis of cellobiose results in the formation of two molecules of glucose, whereas transglycosylation results in the formation of one molecule of glucose and one trisaccharide (Scheme 1). For this reason, the catalytic constant for transglycosylation in Equation 2 is multiplied by a factor of ½; this correction is not necessary for the pNPG substrate, as both the hydrolysis and transglycosylation reactions result in the formation of one molecule of pNP. The values of all four parameters were found by the non-linear regression analysis of the data for cellobiose turnover, according to Equation 2. We were primarily interested in the hydrolytic reaction. Therefore, the data points in the region of high cellobiose concentrations were, in some cases, insufficient for precise measurements of the parameter values for transglycosylation. However, one can estimate that the values of kcat(h) were approximately an order of magnitude higher than the values of kcat(t), whereas the opposite was true for the KM values (Additional file 1: Table S1). To test the possible interdependency between the parameters for the hydrolytic and transglycosylation reactions, we performed a non-linear regression analysis with the datasets in which the highest cellobiose concentration was limited to 5 KM(h) (Additional file 1: Table S1). The resulting kcat(h) and KM(h) values were close to those obtained from the analysis of the full datasets, indicating that the values for kcat(h) and KM(h) can be calculated without precise estimates of the values of kcat(t) and KM(t) (Additional file 1: Table S1). Another possibility for determining the values of kcat(h) and KM(h) is to restrict the analysis to data points in the regions of substrate concentration at which substrate inhibition is not yet revealed and to employ the simple Michaelis-Menten equation. However, this approach resulted in somewhat lower kcat(h) and KM(h) values, whereas the values of kcat(h)/KM(h) were overestimated (Additional file 1: Table S1). Figure 2 shows the turnover of cellobiose at different temperatures, and the kcat(h) and KM(h) values obtained are listed in Table 1. Although at the same order of magnitude, the highest kcat(h) values were found for TaBG3, followed by N188BG and AtBG3. However, it must be noted that, because of the competing transglycosylation reaction, cellobiose hydrolysis at the kcat(h) value is never realized (kcat(h) is the limiting value of kobsCB in the absence of transglycosylation, see Equation 2 in the case of kcat(t) = 0 and KM(t) → ∞). The highest measured kobsCB values averaged 60% ± 4%, 81% ± 13% and 72% ± 3% percent of the kcat(h) value for TaBG3, AtBG3 and N188BG, respectively (Table 1). The highest kcat(h)/KM(h) values were found for TaBG3, followed by AtBG3 and N188BG (Table 2). The values of all the kinetic parameters increased with increasing temperature. The activation energies for kcat(h) and kcat(h)/KM(h) and standard enthalpy changes for KM(h) and Ki were derived from the corresponding Arrhenius plots (Additional file 1: Figure S1) and are listed in Table 3. Among the parameters examined, the highest activation energies were found for kcat(h); activation energies for cellobiose hydrolysis in the range of 50 kJ mol-1 have previously been reported for BGs, consistent with our observations [19].

Figure 2.

Hydrolysis of cellobiose at different temperatures. Observed rate constants for the turnover of cellobiose (kobsCB) at 25°C (□), 35°C (■), 45°C (◊), 55°C (♦) and 65°C (∆). β-glucosidases included (A)TaBG3, (B)AtBG3 and (C)N188BG. The solid lines are from the non-linear regression according to Equation 2.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for cellobiose hydrolysis by β-glucosidases

| |

kcat(h) (s-1)a |

KM(h)(mM)a |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (°C) | N188BG | TaBG3 | AtBG3 | N188BG | TaBG3 | AtBG3 |

| 25 |

121 ± 4 (70%) |

227 ± 10 (57%) |

105 ± 11 (95%) |

0.73 ± 0.04 |

0.42 ± 0.03 |

0.29 ± 0.07 |

| 35 |

271 ± 5 (72%) |

401 ± 19 (57%) |

180 ± 11 (92%) |

0.97 ± 0.04 |

0.51 ± 0.04 |

0.32 ± 0.04 |

| 45 |

493 ± 12 (70%) |

632 ± 20 (61%) |

326 ± 14 (81%) |

1.34 ± 0.06 |

0.60 ± 0.03 |

0.41 ± 0.04 |

| 55 |

691 ± 27 (76%) |

1058 ± 81 (60%) |

666 ± 23 (66%) |

1.36 ± 0.12 |

0.67 ± 0.10 |

0.87 ± 0.05 |

| 65 | 1497 ± 53 (67%) | 968 ± 31 (71%) | 0.82 ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.06 | ||

The values in parentheses show the highest measured value of the rate constant for cellobiose hydrolysis as a percentage of kcat(h).

aThe values of kcat(h) and KM(h) were determined by a non-linear regression analysis of the data of cellobiose turnover, according to Equation 2.

Table 2.

Specificity constants of β-glucosidases for cellobiose

| |

kcat(h)/KM(h)for cellobiose (x 105 M-1 s-1)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| t (°C) | N188BG | TaBG3 | AtBG3 |

| 25 |

1.66 ± 0.10 |

5.43 ± 0.45 |

3.61 ± 0.84 |

| 35 |

2.78 ± 0.11 |

7.81 ± 0.67 |

5.62 ± 0.77 |

| 45 |

3.69 ± 0.17 |

10.6 ± 0.60 |

7.99 ± 0.77 |

| 55 |

5.07 ± 0.44 |

15.5 ± 2.16 |

7.65 ± 0.47 |

| 65 | 18.4 ± 1.25 | 10.4 ± 0.63 | |

aThe kcat(h)/KM(h) values were calculated from the values of kcat(h) and KM(h) listed in Table 1.

Table 3.

Activation energies and binding enthalpies for the kinetic parameters of β-glucosidases

| |

Activation energy, Ea (kJ mol-1)a |

Binding enthalpy, ΔH0 (kJ mol-1)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcat(h) | kcat(h)/KM(h) | KM(h) | Ki(Glc) | |

|

N188BG |

47.6 ± 1.3 |

29.5 ± 1.7 |

18.1 ± 1.0 |

19.6 |

|

TaBG3 |

39.8 ± 1.9 |

26.2 ± 2.3 |

13.6 ± 1.2 |

22.8 |

| AtBG3 | 48.2 ± 2.7 | 20.5 ± 2.4 | 27.7 ± 3.3 | 24.6 |

aFor the parameter p, the activation energy (for kcat(h) and kcat(h)/KM(h)) and standard binding enthalpy (for KM(h) and Ki(Glc)) was obtained from the slope of the line in the coordinates of ln(p) versus 1/T. For the data, see Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Inhibition of β-glucosidases by glucose

Glucose inhibition was evaluated using pNPG or 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-glucoside (MUG) as the substrate. The dependency of the strength of glucose inhibition on the substrate used for inhibition studies reported in the literature, i.e., chromogenic model substrates or cellobiose, is controversial. In some studies, glucose inhibition appears stronger with a cellobiose than pNPG substrate [20], whereas the opposite is also reported [20-24]. Furthermore, there is no obvious mechanistic interpretation for why the inhibition strength should be different with cellobiose and pNPG or MUG. In all cases, nucleophilic attack results in the formation of the same glucosyl-enzyme intermediate [9], and the only difference lies in the nature of the leaving group in the +1 binding site, which is glucose in the case of cellobiose and para-nitrophenole (pNP) or 4-methylumbelliferone (MU) in the case of pNPG or MUG, respectively. Therefore, we chose to study glucose inhibition on model substrates, the hydrolysis of which can be easily detected in a background of added glucose.

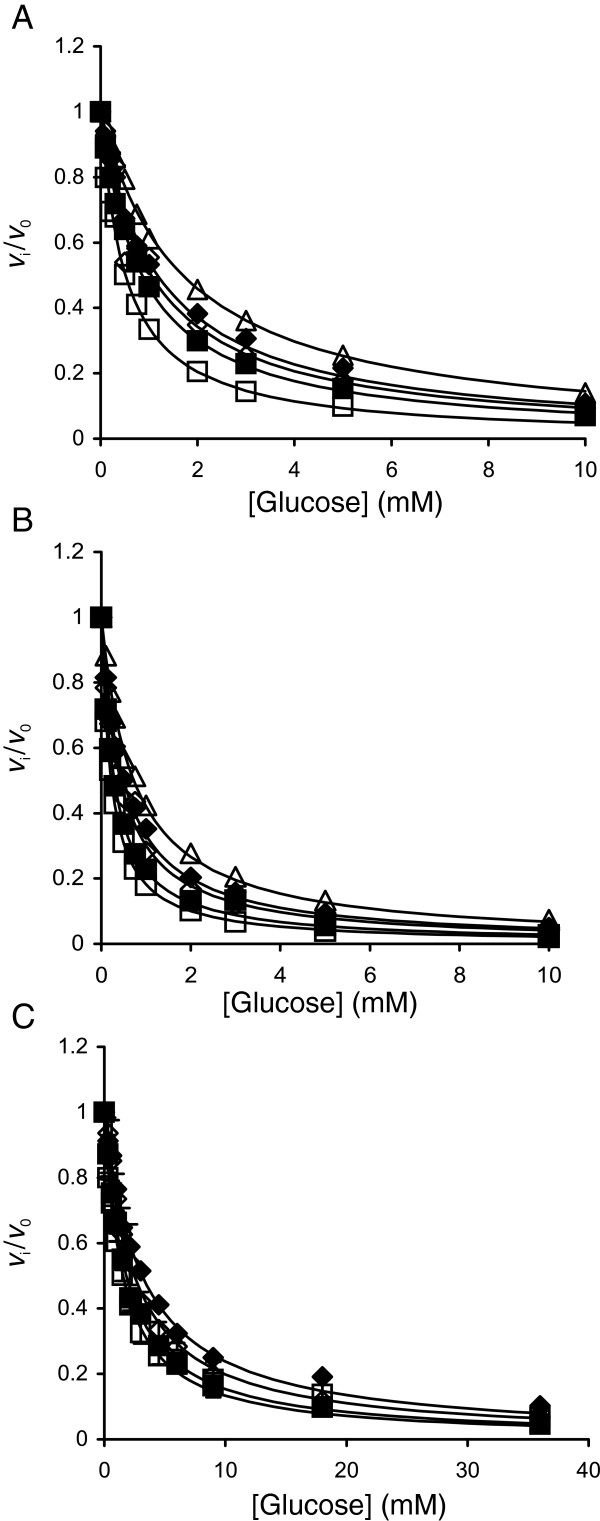

Although not without exceptions [25], glucose is a competitive inhibitor for BGs. In one trial (25°C, pNPG) we tested the type of inhibition by assessing the influence of glucose on the kinetic parameters of TaBG3. Consistent with competitive inhibition, increasing glucose concentration resulted in increased KM(h) and KM(t), with no or little effect on kcat(h) and kcat(t); approximate Ki values of 0.7 mM and 12 mM were found for glucose inhibition of the hydrolytic and transglycosylation reactions, respectively. For further investigation, we used a simplified approach and measured IC50 values by varying the concentration of glucose in the experiments at a single substrate concentration. Provided that the inhibition is competitive and the substrate concentration is well below its KM value, the IC50 value is close to the true Ki value [26]. At low substrate concentrations, the contribution of transglycosylation is negligible and is not expected to interfere with glucose inhibition of the hydrolytic reaction. First, the KM(h) values for pNPG were measured using a non-linear regression analysis of the data of pNPG hydrolysis, according to Equation 2 (the rate constant of pNPG hydrolysis, kobspNPG, was plotted as a function of [pNPG] instead of kobsCBversus [CB]) (Figure 1A). At 25°C, KM(h) values of 0.61 ± 0.06 mM, 0.22 ± 0.03 mM and 0.095 ± 0.003 mM were found for N188BG, TaBG3 and AtBG3, respectively. In the inhibition studies with N188BG, 50 μM pNPG was used as the substrate; however, low KM(h) values did not permit the use of the pNPG substrate for TaBG3 and AtBG3 because of the sensitivity limitations of the initial rate measurements under the conditions of [pNPG] < <KM(h). As the detection of MU fluorescence enables much greater sensitivity, MUG concentrations of 5 μM and 2.5 μM were used for TaBG3 and AtBG3, respectively. The initial rates measured in the presence of glucose (vi) were divided by those measured in the absence of glucose (v0), and data in the coordinates vi/v0versus [Glc] (Figure 3) were fitted to Equation 3.

Figure 3.

Glucose inhibition of β-glucosidases. The initial rates of the hydrolysis of 5 μM MUG by TaBG3 (A), 2.5 μM MUG by AtBG3 (B) or 50 μM pNPG by N188BG (C) measured in the presence of glucose (vi) were divided by those measured in the absence of glucose (v0). The temperatures used were 25°C (□), 35°C (■), 45°C (◊), 55°C (♦) and 65°C (∆). The solid lines are from the non-linear regression according to Equation 3.

| (3) |

In the fitting of the data, the substrate concentration ([S]) was fixed to the value used in the experiments. The value of [S] and the values of the empirical constants C1 and C2 found by the fitting were further used to calculate the IC50 value using Equation 4.

| (4) |

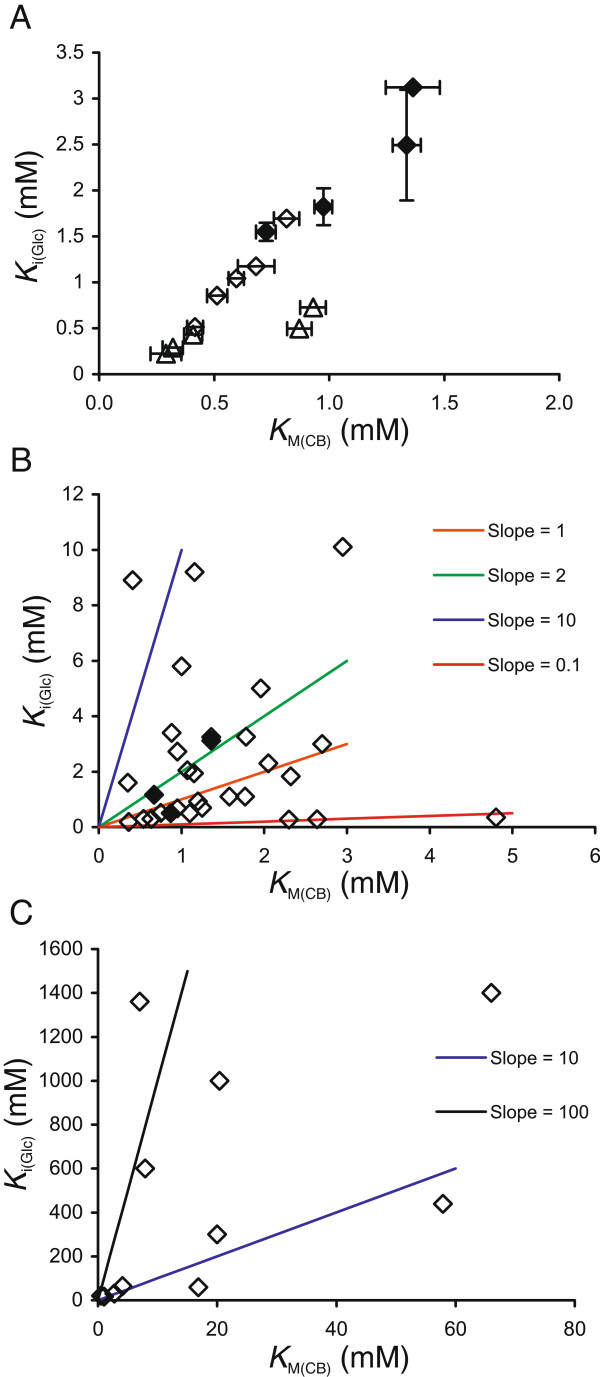

Because of the experimental conditions, [S] < <KM, these IC50 values are further referred to as Ki for glucose, Ki(Glc). The Ki(Glc) values for BGs at different temperatures are listed in Table 4; the enzyme most sensitive to glucose inhibition was AtBG3, followed by TaBG3 and N188BG. With all BGs, the strength of glucose inhibition decreased with increasing temperature; thus, the use of higher temperatures has an advantage of both increasing the catalytic efficiency and relieving the product inhibition. By plotting Ki(Glc)versus KM(h) for cellobiose, KM(CB) (Figure 4A) revealed a trade-off between the two parameters: a higher affinity for cellobiose is accompanied by a stronger glucose inhibition. Because of the similar temperature dependency of KM(CB) and Ki(Glc), the data points for a specific BG at different temperatures followed the same line in the coordinates Ki(Glc)versus KM(CB) (Figure 4A). We also conducted a literature survey in search of a correlation between the kinetic parameters of cellobiose hydrolysis and glucose inhibition. Table 5 lists BGs in order of increasing Ki(Glc). Although much scattering is observed, BGs can be tentatively divided into three groups based on their relative affinity for cellobiose (KM(CB)) and glucose (Ki(Glc)). (1) BGs with a higher affinity for glucose than for cellobiose, KM(CB) > > Ki(Glc) (Figure 4B, BGs near the red line). Because of the low specificity constants for cellobiose and strong glucose inhibition, these BGs are not suitable for supporting CBHs in cellulose degradation. (2) BGs with an approximately equal affinity for cellobiose and glucose, KM(CB) ≈ Ki(Glc). Most of the listed BGs belong to this group, which can be further divided into two sub-groups, BGs with KM(CB) slightly higher than Ki(Glc) (Figure 4B, BGs near the pink line) and BGs with KM(CB) slightly lower than Ki(Glc) (Figure 4B, BGs near the green line). Although the variation is more than two orders of magnitude (partly because of the different temperatures used), BGs belonging to this group have highest specificity constants for cellobiose (kcat/KM(CB) values usually higher than 105 M-1 s-1). These BGs include N188BG and the other fungal BGs most often used to support cellulases in cellulose hydrolysis. (3) BGs with a higher affinity for cellobiose than for glucose, KM(CB) < <Ki(Glc) (Figure 4B and C, BGs near the blue and black line). This group consists of BGs that are also referred to as glucose-tolerant BGs. Their Ki(Glc) values are in the molar or sub-molar range, and the Ki(Glc)/KM(CB) ratio is often more than 10 [27-33]. These BGs, however, tend to have low kcat and kcat/KM(CB) values for cellobiose (kcat/KM(CB) in the order of or below 104 M-1 s-1).

Table 4.

Glucose inhibition of β-glucosidases

| |

Ki for glucose, Ki(Glc)(mM) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| t (°C) | N188BGa | TaBG3b | AtBG3b |

| 25 |

1.55 |

0.51 |

0.22 |

| 35 |

1.82 |

0.85 |

0.29 |

| 45 |

2.50 |

1.04 |

0.43 |

| 55 |

3.12 |

1.17 |

0.50 |

| 65 | 1.69 | 0.73 | |

astudied using pNPG.

bstudied using MUG.

Figure 4.

A higher affinity for cellobiose is accompanied by a stronger glucose inhibition of β-glucosidases (BGs). (A) The values of the Michaelis constants for cellobiose hydrolysis (KM(h)) and the inhibition constants for glucose (Ki(Glc)) are from Table 1 and Table 4, respectively. TaBG3 (◊), AtBG3 (∆) and N188BG (♦). (B and C) A literature survey revealed that BGs can be tentatively divided into three groups based on their relative affinities for cellobiose (KM(CB)) and glucose (Ki(Glc)): (i) KM(CB) > > Ki(Glc), BGs near the red line; (ii) KM(CB) ≈ Ki(Glc), BGs near the pink and the green line and (iii) KM(CB) < <Ki(Glc), BGs near the blue and the black line. For the numerical values of KM(CB) and Ki(Glc), see Table 5. If Ki(Glc) values measured using both pNPG and cellobiose as the substrate were available, the priority was given to the Ki(Glc) value measured using cellobiose. Data from the present study (♦).

Table 5.

Kinetic parameters of selected β-glucosidases

|

Organism |

|

|

kcat (s-1) |

KM (mM) |

kcat/KM (105 M-1 s-1) |

Ki glucose (mM) |

Ki/KMa |

Ref |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t°C | pH | CB | pNPG | CB | pNPG | CB | pNPG | on CB | on pNPG | |||

|

Penicillium verruculosum |

|

|

118b |

650b |

0.36 |

1.6 |

3.29 |

4.06 |

|

0.19 |

0.53 |

[34] |

|

Phanerochaete chrysosporium |

22 |

4 |

50 |

132 |

2.3 |

0.10 |

0.22 |

13.8 |

|

0.27 |

0.12 |

[35] |

|

Myceliophthora thermophila |

40 |

5 |

46 |

147 |

2.64 |

0.39 |

0.17 |

3.76 |

|

0.28 |

0.11 |

[36] |

|

Thermoascus aurantiacus |

60 |

4.5 |

284 |

242 |

0.64 |

0.11 |

4.46 |

21.2 |

|

0.29 |

0.45 |

[37] |

|

Trichoderma reesei |

50 |

4.5 |

22 |

|

0.54 |

|

0.41 |

|

0.29 |

|

0.54 |

[38] |

|

Fomitopsis palustris |

50 |

5 |

102 |

721 |

4.8 |

0.12 |

0.21 |

61.6 |

|

0.35 |

0.07 |

[39] |

|

Acremonium thermophilum |

55 |

5 |

666 |

|

0.87 |

|

7.65 |

|

|

0.50 |

0.57 |

Tc |

|

Magnaporthe grisea |

50 |

5 |

|

|

1.1 |

|

|

|

0.5 |

|

0.45 |

[8] |

|

Trichoderma reesei |

40 |

5 |

42 |

118 |

0.75 |

0.09 |

0.56 |

13.1 |

|

0.51 |

0.68 |

[40] |

|

Chaetomium globosum |

50 |

5 |

168 |

|

0.95 |

|

1.77 |

|

0.68 |

|

0.72 |

[21] |

|

Trichoderma reesei |

40 |

5 |

29 |

70.8 |

1.25 |

0.1 |

0.23 |

6.94 |

|

0.7 |

0.56 |

[41] |

|

Penicillium verruculosum |

40 |

5 |

89 |

160 |

1.2 |

0.44 |

0.74 |

3.64 |

|

0.93 |

0.78 |

[40] |

|

Aspergillus fumigatus |

50 |

5 |

768 |

|

1.77 |

|

4.34 |

0.00 |

1.1 |

|

0.62 |

[21] |

|

Penicillium brasilianum |

22 |

4.8 |

53.7b |

146b |

1.58 |

0.09 |

0.34 |

16.2 |

1.1 |

2.3 |

0.70 |

[20] |

|

Thermoascus aurantiacus |

55 |

5 |

1058 |

|

0.67 |

|

15.5 |

|

|

1.17 |

1.75 |

Tc |

|

Aspergillus niger (N188) |

22 |

4.8 |

|

|

0.35 |

0.45 |

|

|

1.6 |

1.1 |

4.57 |

[20] |

|

Emericella nidulans |

50 |

5 |

87 |

|

2.32 |

|

0.38 |

|

1.83 |

|

0.79 |

[21] |

|

Aspergillus niger (N188) |

50 |

5 |

558 |

|

1.15 |

|

4.85 |

|

1.94 |

|

1.69 |

[21] |

|

Fusarium oxysporum |

50 |

5 |

323 |

7.7 |

1.07 |

0.09 |

3.02 |

0.83 |

|

2.05 |

1.92 |

[42] |

|

Penicillium brasilianum |

50 |

5 |

520 |

|

2.05 |

|

2.54 |

|

2.3 |

|

1.12 |

[21] |

|

Aspergillus japonicus |

40 |

5 |

350 |

259 |

0.95 |

0.6 |

3.68 |

4.32 |

|

2.73 |

2.87 |

[40] |

|

Aspergillus niger |

25 |

4.5 |

104b |

61b |

2.7 |

1 |

0.38 |

0.61 |

|

3 |

1.11 |

[43] |

|

Aspergillus niger (N188) |

55 |

5 |

691 |

|

1.36 |

|

5.07 |

|

|

3.12 |

2.29 |

Tc |

|

Trichoderma reesei |

50 |

4.8 |

41 |

87.9 |

1.36 |

0.38 |

0.30 |

2.31 |

|

3.25 |

2.39 |

[23] |

|

Aspergillus oryzae |

50 |

5 |

363 |

|

1.78 |

|

2.04 |

|

3.26 |

|

1.83 |

[21] |

|

Aspergillus niger (N188) |

50 |

4.8 |

32 |

23.4 |

0.88 |

0.57 |

0.36 |

0.41 |

3.4 |

2.7 |

3.86 |

[23] |

|

Aspergillus oryzae |

50 |

5 |

1000 |

370 |

1.96 |

0.29 |

5.10 |

12.7 |

5 |

2.9 |

2.55 |

[22] |

|

Aspergillus niger |

40 |

4 |

2780 |

917 |

15.4 |

2.2 |

1.81 |

4.17 |

|

5.7 |

0.37 |

[44] |

|

Aspergillus tubingensis |

30 |

4.6 |

331b |

140b |

1 |

0.76 |

3.31 |

1.83 |

|

5.8 |

5.80 |

[45] |

|

Penicillium italicum |

60 |

4.5 |

2641 |

1746 |

0.41 |

0.11 |

64.4 |

158 |

|

8.9 |

21.7 |

[25] |

|

Aspergillus japonicus |

30 |

5 |

46b |

54.5b |

1.16 |

0.2 |

0.40 |

2.72 |

|

9.2 |

7.93 |

[46] |

|

Neurospora crassa |

50 |

5 |

423 |

640 |

2.95 |

2.54 |

1.43 |

2.52 |

10.1 |

6.43 |

3.42 |

[21] |

|

Aspergillus sp |

60 |

4.5 |

|

|

|

1.0 |

|

|

|

17 |

17 |

[47] |

|

Periconia sp |

40 |

5 |

972b |

1180b |

0.5 |

0.19 |

19.4 |

62.7 |

|

20 |

40.0 |

[48] |

|

Baltic sea metagenome |

30 |

6.5 |

11.2 |

22.5 |

2.76 |

0.37 |

0.04 |

0.61 |

|

30 |

10.8 |

[49] |

|

Aspergillus niger (N188) |

45 |

5 |

|

|

16.8 |

1.77 |

|

|

59.5 |

1.59 |

3.54 |

[24] |

|

Streptomyces sp |

50 |

6.5 |

35.6 |

28.4 |

4.1 |

0.15 |

0.09 |

1.89 |

|

65 |

15.8 |

[50,51] |

|

Torulopsis wickerhamii |

|

|

|

362b |

300 |

2.8 |

|

1.29 |

|

190 |

0.63 |

[52] |

|

Thermoascus aurantiacus |

40 |

5 |

0.72b |

5.08b |

|

0.2 |

|

0.25 |

|

300 |

|

[27] |

|

Pyrococcus furiosus |

95 |

5 |

454 |

677b |

20 |

0.15 |

0.23 |

45.1 |

|

300 |

15.0 |

[53] |

|

Debaromyces vanrijiae |

40 |

5 |

141b |

1113b |

57.9 |

0.77 |

0.02 |

14.5 |

|

439 |

7.58 |

[54] |

|

Aspergillus niger |

40 |

4 |

4.3b |

223 |

|

21.7 |

|

0.10 |

|

543 |

|

[28] |

|

Thermoanaer. thermosacch. |

70 |

6.4 |

104b |

55b |

7.9 |

0.63 |

0.13 |

0.88 |

|

600 |

75.9 |

[29] |

|

Uncultured bacterium |

40 |

6.5 |

13.2b |

43b |

20.4 |

0.39 |

0.01 |

1.11 |

|

1000 |

49.0 |

[55] |

|

Aspergillus oryzae |

50 |

5 |

253b |

764b |

7 |

0.55 |

0.36 |

13.9 |

|

1360 |

194 |

[30] |

| Candida peltata | 50 | 5 | 54b | 158b | 66 | 2.3 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 1400 | 21.2 | [31] | |

BGs are listed in the order of increasing Ki(Glc). If Ki(Glc) values measured using both pNPG and cellobiose (CB) as the substrate were available, the priority was given to the Ki(Glc) value measured using cellobiose.

aKM is for cellobiose hydrolysis. If Ki(Glc) values measured using both pNPG and cellobiose (CB) as the substrate were available, the priority was given to the Ki(Glc) value measured using cellobiose.

bCalculated from the reported specific activity and molecular weight of the enzyme.

cThis study.

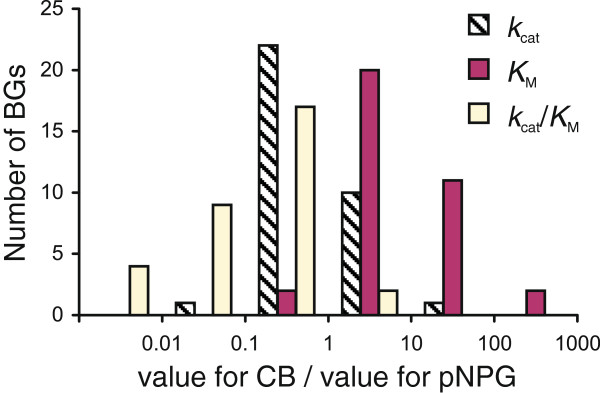

BGs have been divided into three groups based on their substrate specificity [9]: (i) aryl BGs, (ii) true cellobiases and (iii) broad-substrate specificity BGs. Although there is no stringent, unequivocal criteria for this classification, the BGs listed in Table 5 appear to belong to the last group. A comparison of the kinetic parameters for cellobiose and pNPG hydrolysis revealed that pNPG is the preferred substrate for the most of the listed BGs (Figure 5). The higher specificity constants for pNPG were mainly caused by the lower KM values for pNPG, whereas the kcat values for pNPG and cellobiose were of the same order. The preference for pNPG over cellobiose was most prominent in the case of the glucose-tolerant BGs and also for BGs with KM(CB) > > Ki(Glc).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the kinetic parameters of β-glucosidases measured for cellobiose and pNPG. The value of the parameter measured for cellobiose was divided by the value of the corresponding parameter measured for pNPG. kcat denotes kcat(CB)/kcat(pNPG), KM denotes KM(CB)/KM(pNPG), and kcat/KM denotes (kcat(CB)/KM(CB))/(kcat(pNPG)/KM(pNPG)). The parameter values listed in Table 5 were used for the calculation of the ratios.

In addition to protein properties, such as stability with regard to pH and temperature, the kinetic properties of enzymes must also be considered in selecting BGs to support cellulases. The main “work horses” in cellulose hydrolysis, GH7 CBHs, are inhibited by cellobiose, with IC50 values in the few millimolar range [26,56-58], and most BGs have a KM value for cellobiose in the same range (Table 5). Thus, to be efficient in relieving the cellobiose inhibition of CBHs, a BG must maintain the steady-state cellobiose concentration well below its IC50 value for CBHs, meaning that most BGs must operate under the conditions of [CB] < <KM(CB). Under the conditions of [CB] < <KM(h), and bearing in mind that KM(h) < <KM(t) and kcat(t) < <kcat(h), Equation 2 reduces to

| (5) |

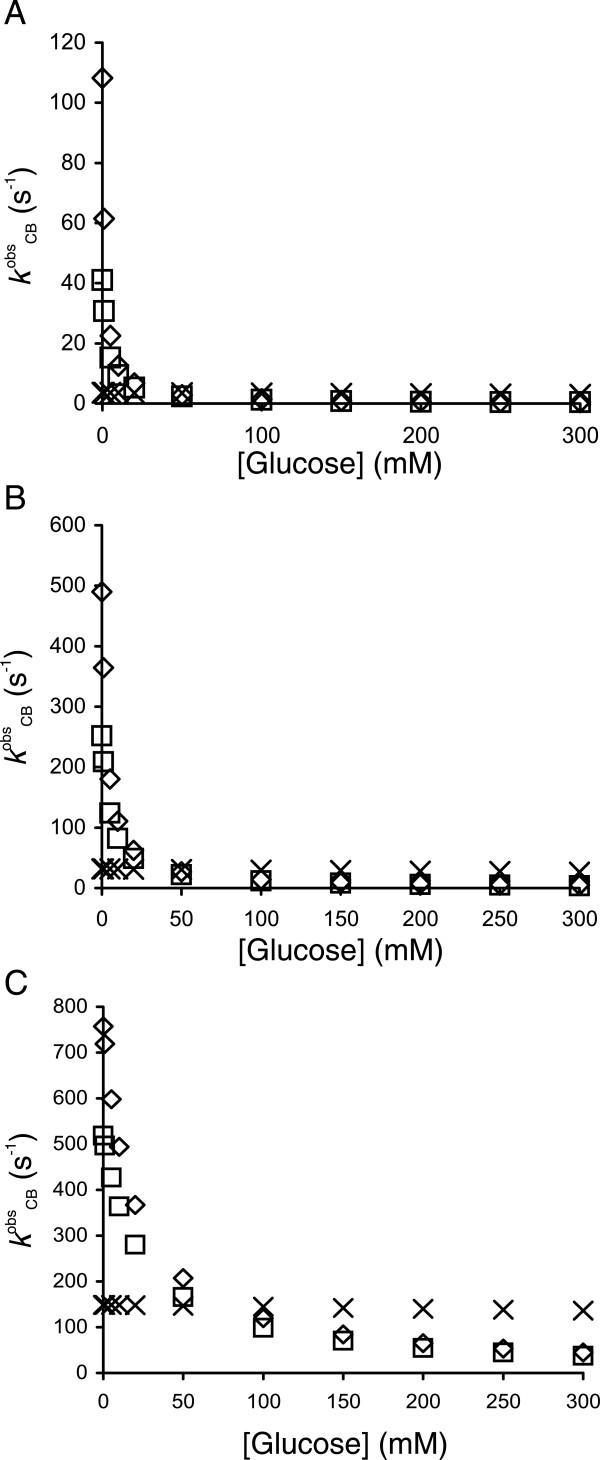

Thus, under the conditions of low cellobiose concentrations, the rate of cellobiose hydrolysis is governed by the specificity constant for the hydrolytic reaction, and the terms accounting for transglycosylation cancel out. Therefore, the kcat(h)/KM(h) value may be an important characteristic for selecting BGs to support cellulases in cellulose hydrolysis. Although the glucose inhibition of CBHs is relatively weak [26,58], the glucose inhibition of a BG will eventually lead to the accumulation of cellobiose and CBH inhibition. Therefore, the value of Ki(Glc) is another important characteristic to consider when selecting BGs. We predicted the kobsCB values at different cellobiose and glucose concentrations for three BGs with different kcat, KM(CB) and Ki(Glc) values (Figure 6). Because of the unavailability of the values of the kinetic parameters, the transglycosylation reaction was ignored, and a simple Michaelis-Menten equation with competitive glucose inhibition was used in the calculations. Using a numerical analysis of the time courses of cellobiose hydrolysis, Bohlin et al. found that product inhibition exerts a more pronounced negative effect on BG activity than transglycosylation [8]. Nonetheless, by ignoring transglycosylation, the kobsCB values calculated herein are somewhat overestimated. TaBG3 and N188BG (characterized in this study) and a glucose-tolerant BG from Aspergillus oryzae (AoBG3) were assessed [30]. The values of the kinetic parameters for TaBG3 and N188BG at 50°C were calculated based on data for the temperature dependency of the parameters. TaBG3 had the highest specificity constant (kcat/KM(CB) = 1.25 x 106 M-1 s-1) but was the enzyme most sensitive to glucose inhibition (Ki(Glc) = 1.14 mM). In contrast, AoBG3 was highly tolerant to glucose inhibition (Ki(Glc) = 1.36 M) but had a moderate specificity constant (kcat/KM(CB) = 3.6 x 104 M-1 s-1). Amid these two enzymes was N188BG, with kcat/KM(CB) and Ki(Glc) values of 4.4 x 105 M-1 s-1 and 2.76 mM, respectively. The kobsCB of TaBG3 was higher than that of N188BG under all the conditions tested, but the difference was more prominent at low cellobiose and glucose concentrations. Although AoBG3 had much lower kobsCB values at low glucose concentrations, it outperformed TaBG3 and N188BG at glucose concentrations above 50 mM. Thus, AoBG3 appears to be a better candidate BG for the hydrolysis of cellulose in separate hydrolysis and fermentation processes under high dry matter conditions. The amount of BG required to maintain the cellobiose concentration at a certain steady-state level depends on the velocity of cellobiose production from cellulose. The maximum catalytic potential of CBHs is given by their kcat value of cellulose hydrolysis and is within the range of 1–10 s-1[57,59,60]. If kcat for cellulose hydrolysis equal to 2 s-1 and kobsCB is 100 s-1, then a molar ratio of CBH/BG of 50 is required to maintain a steady-state cellobiose concentration, which means that the relative amount of BG in a cellulase system must be approximately 4% (w/w, considering that BGs usually have approximately 2-fold higher molar masses than CBHs). However, if kobsCB is only 10 s-1, as in the case of TaBG3 and N188BG at high glucose concentrations or in the case of AoBG3 at low cellobiose concentrations (Figure 6), the relative amount of BG must be 10 times higher. Although the hydrolysis of lignocellulose is much slower than that predicted by the kcat value of CBHs, we used the catalytic potential of CBHs to predict the relative amount of BG to ensure that the rate limitation of cellulose hydrolysis via BG activity is excluded. The selection criteria of candidate BGs also depend on the lignocellulose hydrolysis set-up. A high kcat/KM(CB) value always becomes an advantage and is the primary kinetic parameter for selecting BGs. However, in separate hydrolysis and fermentation at a high dry matter concentration, the advantage of having a high Ki(Glc) value may overbalance the somewhat lower kcat/KM(CB) value. Because of the trade-off between Ki(Glc) and KM(CB), it is, unfortunately, not possible to maximize both kcat/KM(CB) and Ki(Glc) in parallel.

Figure 6.

Calculated values of the rate constants of cellobiose hydrolysis for β-glucosidases with different kinetic properties. The values of the observed rate constants of cellobiose hydrolysis (kobsCB) at different cellobiose and glucose concentrations were calculated using the simple Michaelis-Menten equation with competitive glucose inhibition and ignoring substrate inhibition. The β-glucosidases used were TaBG3 (◊) and N188BG (□), characterized in the present study, and a previously characterized glucose-tolerant β-glucosidase from Aspergillus oryzae (AoBG3) (×) [30]. kcat(h) values of 806 s-1, 587 s-1 and 253 s-1, KM(CB) values of 0.65 mM, 1.33 mM and 7.0 mM and Ki(Glc) values of 1.14 mM, 2.75 mM and 1360 mM were used for TaBG3, N188BG and AoBG3, respectively. The concentration of cellobiose was set to 0.1 mM (A), 1.0 mM (B) or 10 mM (C).

Conclusions

The analysis of the kinetic parameters of BGs in the light of the cellobiose inhibition of CBHs suggested that the specificity constant for cellobiose hydrolysis and the inhibition constant for glucose are the most important parameters in selecting BGs to support cellulose hydrolysis. The use of higher temperatures had the advantage of both increasing the catalytic efficiency and relieving the glucose inhibition of BGs. Our data, together with data from a literature survey, revealed a trade-off between the strength of glucose inhibition and the affinity for cellobiose: an increased tolerance to glucose inhibition was accompanied by a decrease in catalytic efficiency (lower specificity constant values). Therefore, the optimal properties of the candidate BG depend on the cellulose hydrolysis set-up. Although a high specificity constant is always an advantage, the priority may be given to a higher tolerance to glucose inhibition when performing separate hydrolysis and fermentation.

Methods

Materials

Glucose, MUG, pNPG, Novozyme®188 and BSA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Cellobiose (≥ 99%) was obtained from Fluka. All the chemicals were used as received from the supplier.

Enzymes

N188BG was purified from Novozyme®188, as previously described [61]. Culture filtrates containing AtBG3 or TaBG3 were kindly provided by Terhi Puranen from Roal Oy (Rajamäki, Finland). BGs were heterologously expressed in a Trichoderma reesei (Tr) strain that lacks the genes of four major cellulases [15]. AtBG3 and TaBG3 were purified using gel-filtration chromatography. The buffer of the crude BG preparation was first changed to 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5) containing 0.15 M NaCl using a Toyopearl HW-40 column. Fractions with high pNPG-ase activity were combined, concentrated with Amicon centrifugal filter devices (5,000 MWCO) and applied to a Sephacryl S-200 column equilibrated with 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5) containing 0.15 M NaCl. TaBG3 was purified identically but using a Sephacryl S-300 column. The purity of AtBG3 and TaBG3 was approximately 95%, as determined by SDS-PAGE. The concentration of AtBG3 and TaBG3 was determined by the bicinchoninic acid method using BSA as a standard and molecular weights of 101 kDa and 81 kDa, respectively [15]. The concentration of N188BG was measured by the absorbance at 280 nm using a theoretical ϵ280 value of 180,000 M-1 cm-1. Several BGs from T. aurantiacus have been previously characterized [27,37,62-64]. According to the molecular weight, TaBG3 characterized herein is closest to that characterized by Tong et al. [62].

Hydrolysis of cellobiose by BGs

The experiments were performed in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.1 g l-1 BSA in a total volume of 0.5 ml. The concentration of cellobiose was varied between 0.1 – 50 mM, and glucose formation was followed in the linear region of time curves. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.25 ml 1.0 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.5), and the concentration of glucose was measured using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase method. The concentrations of hexokinase, G6PDH, NADP+, ATP and MgCl2 in the assay were 1.5 U/ml, 0.75 U/ml, 0.64 mM, 1.26 mM and 13.3 mM, respectively. After completion of the reaction (approximately 15 min), the absorbance at 340 nm was recorded. The zero data points were identical, but 0.25 ml 1.0 M Tris–HCl (pH 8.5) was added prior to BG. Calibration curves were generated using glucose as a standard.

Activity and glucose inhibition of BGs using pNPG and MUG

For the activity measurements, the initial rates of pNPG (0.01 – 20 mM) hydrolysis were measured in 50 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) containing 0.1 g l-1 BSA in a total volume of 0.9 ml. The reactions were stopped by the addition of 0.1 ml 1.0 M NH3, and the pNP released was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 414 nm. The glucose inhibition of BGs was measured using 0.05 mM pNPG (N188BG), 5 μM MUG (TaBG3) or 2.5 μM MUG (AtBG3) as the substrate. The experiments were performed as above, but the reactions were supplied with glucose (0.1 – 36 mM). The pNP released was quantified by measuring the absorbance at 414 nm, and the MU released was quantified by fluorescence using excitation and emission wavelengths of 360 nm and 450 nm, respectively. All the rates correspond to the initial rates.

Abbreviations

At: Acremonium thermophilum; BG: β-glucosidase; BSA: Bovine serum albumin; CB: Cellobiose; CBH: Cellobiohydrolase; EG: Endoglucanase; GH: Glycoside hydrolase; Glc: Glucose; MU: 4-methylumbelliferone; MUG: 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-glucoside; N188BG: BG purified from Novozyme®188; pNP: Para-nitrophenol; pNPG: Para-nitrophenyl-β-glucoside; SHF: Separate hydrolysis and fermentation; SSF: Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation; Ta: Thermoascus aurantiacus; Tr: Trichoderma reesei.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HT and PV designed and performed the experiments. PV wrote the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material to “Selecting beta-glucosidases to support cellulases in cellulose saccharification”.

Contributor Information

Hele Teugjas, Email: hele.teugjas@ut.ee.

Priit Väljamäe, Email: priit.valjamae@ut.ee.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the EU Commission (FP7/2007-2013, grant agreement no. 213139). Dr Terhi Puranen from Roal Oy (Rajamäki, Finland) and Dr Matti Siika-Aho from VTT (Espoo, Finland) are acknowledged for the crude preparations of TaBG3 and AtBG3. Among our colleagues from the University of Tartu, we thank Jürgen Jalak for assistance in protein purification and in preparing the figures, Laura Tompson for the preliminary analysis of β-glucosidases and Dr Silja Kuusk for critical reading of the manuscript.

References

- Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial cellulose utilization: fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SJ, Vaaje-Kolstad G, Westereng B, Eijsink VGH. Novel enzymes for the degradation of cellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:45. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhania RR, Patel AK, Sukumaran RK, Larroche C, Pandey A. Role and significance of beta-glucosidases in the hydrolysis of cellulose for bioethanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2013;127:500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAZy database. http://www.cazy.org.

- Cantarel BL, Coutinho PM, Rancurel C, Bernard T, Lombard V, Henrissat B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acid Res. 2009;37:D233–D238. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pozo MV, Fernandez-Arrojo L, Gil-Martinez J, Montesinos A, Chernikova TN, Nechitaylo TY, Waliszek A, Tortajada M, Rojas A, Huws SA, Golyshina OV, Newbold CJ, Polaina J, Ferrer M, Golyshin PN. Microbial β-glucosidases from cow rumen metagenome enhance the saccharification of lignocellulose in combination with commercial cellulase cocktail. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:73. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai R, Igarashi K, Kitaoka M, Ishii T, Samejima M. Kinetics of substrate transglycosylation by glycoside hydrolase family 3 glucan (1 → 3)-β-glucosidase from the white-rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Carbohydr Res. 2004;339:2851–2857. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin C, Praestgaard E, Baumann MJ, Borch K, Praestgaard J, Monrad RN, Westh P. A comparative study of hydrolysis and transglycosylation activities of fungal β-glucosidases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:159–169. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-3875-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia Y, Mishra S, Bisaria VS. Microbial β-glucosidases: cloning, properties, and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2002;22(4):375–407. doi: 10.1080/07388550290789568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric P, Meyer AS, Jensen PA, Dam-johansen K. Reactor design for minimizing product inhibition during enzymatic lignocelluloses hydrolysis: I. Significance and mechanism of cellobiose and glucose inhibition on cellulolytic enzymes. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:308–324. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andric P, Meyer AS, Jensen PA, Dam-johansen K. Reactor design for minimizing product inhibition during enzymatic lignocelluloses hydrolysis: II. Quantification of inhibition and suitability of membrane reactors. Biotechnol Adv. 2010;28:407–425. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galazka JM, Tian C, Beeson WT, Martinez B, Glass NL, Cate JHD. Cellodextrin transport in yeast for improved biofuel production. Science. 2010;330:84–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1192838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen JB, Felby C, Jorgensen H. Yield-determining factors in high-solids enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2009;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öhgren K, Vehmaanperä J, Siika-aho M, Galbe M, Viikari L, Zacchi G. High temperature enzymatic prehydrolysis prior to simultaneous saccharification and fermentation of steam pretreated corn stover for ethanol production. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2007;40:607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vehamaanperä J, Alapuranen M, Puranen T, Siika-aho M, Kallio J, Hooman S, Voutilainen S, Halonen T, Viikari L. Treatment of cellulosic material and enzymes useful therein. Patent application FI 20051318, WO2007071818. Priority 22.12.2055.

- McClendon SD, Batth T, Petzold CJ, Adams PD, Simmons BA, Singer SW. Thermoascus aurantiacus is a promising source of enzymes for biomass deconstruction under thermophilic conditions. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:54. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidle HF, Huber RE. Transglucosidic reactions of the Aspergillus niger family 3 β-glucosidase: qualitative and quantitative analyses and evidence that the transglucosidic rate is independent of pH. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;436:254–264. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidle HF, McKenzie K, Marten I, Shoseyov O, Huber RE. Trp-262 is a key residue for the hydrolytic and transglucosidic reactivity of the Aspergillus niger family 3 β-glucosidase: substitution results in enzymes with mainly transglucosidic activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;444:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsavara LPV, De Moraes FF, Zanin GM. Modeling cellobiose hydrolysis with integrated kinetic models. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1999;77–79:789–806. doi: 10.1385/abab:79:1-3:789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh KBRM, Harris PV, Olsen CL, Johansen KS, Hojer-Pedersen J, Borjesson J, Olsson L. Characterization and kinetic analysis of thermostable GH3 β-glucosidase from Penicillium brasilianum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;86(1):143–154. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin C, Olsen SN, Morant MD, Patkar S, Borch K, Westh P. A comparative study of activity and apparent inhibition of fungal β-glucosidases. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2010;107:943–952. doi: 10.1002/bit.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langston J, Sheehy N, Xu F. Substrate specificity of Aspergillus oryzae family 3 β-glucosidase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1764:972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauve M, Mathis H, Huc D, Casanave D, Monot F, Ferreira NL. Comparative kinetic analysis of two fungal β-glucosidases. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2010;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng IS, Tsai SW, Ju YM, Yu SM, Ho THD. Dynamic synergistic effect on Trichoderma reesei cellulases by novel β-glucosidases from Taiwanese fungi. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:6073–6081. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park A-R, Hong JH, Kim J-J, Yoon J-J. Biochemical characterization of an extracellular β-glucosidase from the fungus, Penicillium italicum, isolated from rotten citrus peel. Mycobiology. 2012;40(3):173–180. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2012.40.3.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teugjas H, Väljamäe P. Product inhibition of cellulases studied with 14C-labeled cellulose substrates. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hong J, Tamaki H, Kumagai H. Unusual hydrophobic linker region of β-glucosidase (BGLII) from Thermoascus aurantiacus is required for hyper-activation by organic solvents. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2006;73:80–88. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan TR, Lin CL. Purification and characterization of a glucose-tolerant β-glucosidase from Aspergillus niger CCRC 31494. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1997;61:965–970. doi: 10.1271/bbb.61.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J, Pang Q, Zhao L, Fan S, Shi H. Thermoanaerobacterium thermosaccharolyticum β-glucosidase: a glucose-tolerant enzyme with high specific activity for cellobiose. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2012;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riou C, Salmon JM, Vallier MJ, Günata Z, Barre P. Purification, characterization, and substrate specificity of a novel highly glucose-tolerant β-glucosidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3607–3614. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3607-3614.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha BC, Bothast RJ. Production, purification, and characterization of a highly glucose-tolerant novel β-glucosidase from Candida peltata. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3165–3170. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3165-3170.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonia KG, Chadha BS, Badhan AK, Saini HS, Bhat MK. Identification of glucose tolerant acid active β-glucosidases from thermophilic and thermotolerant fungi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;24:599–604. doi: 10.1007/s11274-007-9512-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waeonukul R, Kosugi A, Prawitwong P, Deng L, Tachaapaikoon C, Pason P, Ratanakhanokchai K, Saito M, Mori Y. Novel cellulase recycling method using a combination of Clostridium thermocellum cellulosomes and Thermoanaerobacter brockii β-glucosidase. Bioresour Technol. 2013;130:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2012.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorov IN, Gusakov AV, Baraznenok VA, Bekkarevich AO, Okunev ON, Sinitsyn AP, Kondrateva EG. Isolation and properties of cellobiase from Penicillium verruculosum. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2001;37:587–592. doi: 10.1023/A:1012351017032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lymar ES, Li B, Renganathan V. Purification and characterization of a cellulose-binding β-glucosidase from cellulose-degrading cultures of Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2976–2980. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.2976-2980.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnaouri A, Topakas E, Paschos T, Taouki I, Christakopoulos P. Cloning, expression and characterization of an ethanol tolerant GH3 β-glucosidase from Myceliophthora thermophila. Peerj. 2013;1:e46. doi: 10.7717/peerj.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry NJ, Beever DE, Owen E, Vandenberghe I, Van Beeum J, Bhat MK. Biochemical characterization and mechanism of action of a thermostable β-glucosidase purified from Thermoascus aurantiacus. Biochem J. 2001;353:117–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid G, Wandrey C. Characterization of a cellodextrin glucohydrolase with soluble oligomeric substrates: experimental results and modeling of concentration-time-course data. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1989;33:1445–1460. doi: 10.1002/bit.260331112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JJ, Kim KY, Cha CJ. Purification and characterization of thermostable β-glucosidase from the brown-rot basidiomycete Fomitopsis palustris grown on microcrystalline cellulose. J Microbiol. 2008;46:51–55. doi: 10.1007/s12275-007-0230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova OG, Semenova MV, Morozova VV, Zorov IN, Sokolova LM, Bubnova TM, Okunev ON, Sinitsyn AP. Isolation and properties of fungal β-glucosidases. Biochem Mosc. 2009;74:569–577. doi: 10.1134/S0006297909050137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico WJ, Brown RD. Purification and characterization of a β-glucosidase from Trichoderma reesei. Eur J Biochem. 1987;165:333–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christakopoulos P, Goodenough PW, Kekos D, Macris BJ, Claeyssens M, Bhat MK. Purification and characterization of an extracellular β-glucosidase with transglycosylation and exo-glucosidase activities from Fusarium oxysporum. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:379–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidle HF, Marten I, Shoseyov O, Huber RE. Physical and kinetic properties of the family 3 β-glucosidase from Aspergillus niger which is important for cellulose breakdown. Protein J. 2004;23:11–23. doi: 10.1023/b:jopc.0000016254.58189.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan TR, Lin YH, Lin CL. Purification and characterization of an extracellular β-glucosidase II with high hydrolysis and transglucosylation activities from Aspergillus niger. J Agric Food Chem. 1998;46:431–437. doi: 10.1021/jf9702499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker CH, Visser J, Schreier P. β-glucosidase multiplicity from Aspergillus tubingensis CBS 943.92: purification and characterization of four β-glucosidases and their differentiation with respect to substrate specificity, glucose inhibition and acid tolerance. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s002530000462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker CH, Visser J, Schreier P. β-glucosidases from five black Aspergillus species: study of their physico-chemical and biocatalytic properties. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:4929–4936. doi: 10.1021/jf000434d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueira JA, Sato HH, Fernandes P. Establishing the feasibility of using β-glucosidase entrapped in Lentikas and in sol–gel supports for cellobiose hydrolysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61:626–634. doi: 10.1021/jf304594s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnipcharnchai P, Champreda V, Sornlake W, Eurwilaichitr L. A thermotolerant β-glucosidase isolated from an endophytic fungi, Periconia sp., with a possible use for biomass conversion to sugars. Prot Express Purif. 2009;67:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierzbicka-Wos A, Bartasun B, Cieslinski H, Kur J. Cloning and characterization of a novel cold-active glycoside hydrolase family 1 enzyme with β-glucosidase, β-fucosidase and β-galactosidase activities. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perezpons JA, Cayetano A, Rebordosa X, Lloberas J, Guasch A, Querol E. A β-glucosidase gene (BGL3) from Streptomyces sp. strain-QM-B814 – molecular cloning, nucleotide-sequence, purification and characterization of the encoded enzyme, a new member of family 1 glycosyl hydrolases. Eur J Biochem. 1994;223:557–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallmitjana M, Ferrer-Navarro M, Planell R, Abel M, Ausin C, Querol E, Planas A, Perezpons JA. Mechanism of the family 1 β-glucosidase from the Streptomyces sp: catalytic residues and kinetic studies. Biochemistry. 2001;40:5975–5982. doi: 10.1021/bi002947j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmel ME, Tucker MP, Lastick SM, Oh KK, Fox JW, Spindler DD, Grohmann K. Isolation and characterization of an 1,4-β-D-glucan glucohydrolase from the yeast, Torulopsis wickerhamii. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12948–12955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kengen SWM, Luesink EJ, Stams AJM, Zehnder AJB. Purification and characterization of an extremely thermostable β-glucosidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:305–312. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belancic A, Gunata Z, Vallier MJ, Agosin E. β-glucosidase from the grape native yeast Debaromyces vanrijiae: purification, characterization, and its effect on monoterpene content of a muscat grape juice. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:1453–1459. doi: 10.1021/jf025777l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemin F, Fang W, Liu J, Hong Y, Peng H, Zhang X, Sun B, Xiao Y. Cloning and characterization of β-glucosidase from marine microbial metagenome with excellent glucose tolerance. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;20:1351–1358. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1003.03011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruno M, Väljamäe P, Pettersson G, Johansson G. Inhibition of the Trichoderma reesei cellulases by cellobiose is strongly dependent on the nature of the substrate. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2004;86:503–511. doi: 10.1002/bit.10838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalak J, Kurašin M, Teugjas H, Väljamäe P. Endo-exo synergism in cellulose hydrolysis revisited. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28802–28815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy L, Bohlin C, Baumann MJ, Olsen SN, Sorensen TH, Anderson L, Borch K, Westh P. Product inhibition of five Hypocrea jecorina cellulases. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2013;52:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruys-Bagger N, Elmerdahl J, Praestgaard E, Tatsumi H, Spodsberg N, Borch K, Westh P. Pre-steady state kinetics for the hydrolysis of insoluble cellulose by cellobiohydrolase Cel7A. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:18451–18458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.334946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi K, Uchihashi T, Koivula A, Wada M, Kimura S, Okamoto T, Penttilä M, Ando T, Samejima M. Traffic jams reduce hydrolytic efficiency of cellulase on cellulose surface. Science. 2011;333:1279–1282. doi: 10.1126/science.1208386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipos B, Benkö Z, Reczey K, Viikari L, Siika-aho M. Characterisation of specific activities and hydrolytic properties of cell-wall-degrading enzymes produced by Trichoderma reesei Rut C30 on different carbon sources. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2010;161:347–364. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8824-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong CC, Cole AL, Shepherd MG. Purification and properties of the cellulases from the thermophilic fungus Thermoascus aurantiacus. Biochem J. 1980;191:83–94. doi: 10.1042/bj1910083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Palma-Fernandez ER, Gomes E, da Silva R. Purification and characterization of two β-glucosidases from the thermophilic fungus Thermoascus aurantiacus. Folia Microbiol. 2002;47:685–690. doi: 10.1007/BF02818672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Tamaki H, Kumagai H. Cloning and functional expression of thermostable β-glucosidase gene from Thermoascus aurantiacus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;73:1331–1339. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material to “Selecting beta-glucosidases to support cellulases in cellulose saccharification”.