Abstract

Hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate (Pyr) has been used to assess metabolism in healthy and diseased states, focusing on downstream labeling of lactate (Lac), bicarbonate (Bic), and alanine. Whereas hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr, which retains the labeled carbon when Pyr is converted to acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), has been successfully used to assess mitochondrial metabolism in the heart, the application of [2-13C]Pyr in the study of brain metabolism has been limited to date, with Lac being the only downstream metabolic product previously reported.

In this study, single time-point chemical shift imaging data were acquired from rat brain in vivo. [5-13C]Glu, [1-13C]ALCAR, and [1-13C]Cit were detected in addition to resonances from [2-13C]Pyr and [2-13C]Lac. Brain metabolism was further investigated by infusing dichloroacetate (DCA), which upregulates Pyr flux to acetyl-CoA. After the DCA administration, a 40 % increase of [5-13C]Glu from 0.014 ± 0.004 to 0.020 ± 0.006 (p = 0.02) primarily from brain and a trend to higher citrate (0.002 ± 0.001 to 0.004 ± 0.002) was detected, whereas [1-13C]ALCAR was increased in peripheral tissues.

This study demonstrates, for the first time, that hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr can be used for the in vivo investigation of mitochondrial function and TCA cycle metabolism in brain.

Keywords: Hyperpolarized 13C, Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy, Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolism, Pyruvate, Glutamate, Dichloroacetate, Brain

Introduction

In addition to the anatomical information provided by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) has proven particularly useful in investigating in vivo cellular metabolism non-invasively due to its capability to differentiate key metabolites based on their chemical shifts [1, 2]. In particular, 1H-MRS is used in the study of neurological abnormalities in brain, including Alzheimer disease [3], multiple sclerosis [4], epilepsy [5], and brain tumors [6]. In contrast to 1H-MRS, the wide chemical shift dispersion of the 13C spectrum provides additional insights into intermediary metabolism and metabolic cycling rates [7, 8]. However, long acquisition times, due to the inherently low sensitivity and correspondingly low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), continue to be the major obstacles for conventional 1H- and 13C-MRS [9, 10].

Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) combined with the dissolution technique that achieves a greater than 10,000-fold increase in SNR above conventional methods enables real-time investigation of in vivo metabolism [11, 12]. Among several applicable substrates, [1-13C]pyruvate (Pyr) has been the most widely used due to its central role in cellular energy metabolism in combination with its long longitudinal relaxation time (T1) and high liquid-state polarization level. One of the main applications of hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyr is metabolic imaging of cancer as it is sensitive to a unique metabolic phenotype in tumors known as Warburg effect whereby glycolysis dominates oxidative phosphorylation even in the presence of oxygen [13-16]. The importance of [1-13C]Pyr is also illustrated by the fact that it is the substrate of choice for the first clinical trial of this new technology [17]. Whereas the conversion of Pyr to lactate (Lac) is a direct measurement of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity [14], the application of [1-13C]Pyr for the assessment of oxidative metabolism is limited.

When [1-13C]Pyr is converted to acetyl-CoA in the mitochondria by the enzyme pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), the labeled carbon is eliminated as 13CO2, which is in fast exchange with bicarbonate (Bic). It has recently been demonstrated in a rat glioma model that the potential anti-cancer drug dichloroacetate (DCA) leads to an increased level of Bic after injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyr [18], suggesting a shift in metabolism from glycolysis towards oxidative phosphorylation. But as the downstream metabolic fate of acetyl-CoA cannot be observed, it is not clear whether the increased flux through PDH corresponds to an increase in oxidative phosphorylation. However, if Pyr is instead labeled in the C2 position, the label is passed on to acetyl-CoA, hence, potentially permitting the investigation of the additional metabolic pathways. Whereas the feasibility of using hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr or [1, 2-13C]Pyr to assess mitochondrial metabolism has been demonstrated in rat and pig heart in vivo [19-22], the application of [2-13C]Pyr in studies of brain metabolism has been limited with Lac being the only metabolic product reported to date [23].

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility of assessing mitochondrial metabolism in rat brain in vivo after a bolus injection of hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr using an optimized single time-point MR spectroscopic imaging protocol. Flux through PDH was modulated by administration of DCA.

Methods

Substrate Preparation and Polarization

A 14-M sample of [2-13C]-labeled pyruvic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Co. St. Louis, MO) mixed with 15-mM trityl radical OX063 was polarized using a HyperSense DNP system (Oxford Instruments Molecular Biotools, Oxford, UK). The optimal microwave irradiation frequency for [2-13C]Pyr was determined by varying the frequency between 94.0 GHz and 94.1 GHz in 1-MHz increments while irradiating the sample for 120 s at each frequency. The solvent buffer consisted of 40-mM trishydroxymethylaminomethane, 125-mM NaOH, 100-mg/L ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid, and 50-mM NaCl, resulting in a 125-mM solution of [2-13C]Pyr. Liquid-state polarization level and T1 of [2-13C]Pyr were estimated from the solid-state polarization build-up curves and independent in vitro measurements, in which liquid-state polarization and T1 of a hyperpolarized sample were measured in the MR scanner using a small flip angle pulse-and-acquire sequence with a repetition time (TR) of 3 s. A volume of 2.0-3.5 mL of the solution with a pH of approximately 7.5 was injected through a rat tail vein catheter at a rate of 0.25 mL/s. The amount of the injected solution was adjusted to maintain a dose of 1.56 mmol/kg body weight for each animal.

Animal Model

Five healthy male Wistar rats (160-390 g) were anesthetized with 1-3 % of isoflurane in oxygen (~1.5 L/min), and cannulated in the tail vein for intravenous administration of both the hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr solution and DCA. Animals were placed on a heated water blanket to maintain body temperature (~37 °C) inside of the magnet. Respiration, body temperature, and oxygen saturation were monitored throughout the MR experiments, while the anesthesia was adjusted to maintain a respiratory rate of 50-60 breaths per minute. Manipulation of PDH flux was achieved by intravenous administration of DCA. DCA promotes mitochondrial function by inhibiting pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), thus increasing activity of PDH, which catalyzes the production of acetyl-CoA from Pyr [24, 25]. A dose of 150 mg DCA per kg body weight, dissolved in saline at 30 mg/mL, was administered through the tail vein catheter with 0.5 mL of the DCA solution injected as a bolus and the rest infused at a rate of 0.1 mL per 3 min. Each animal received four injections of hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr: two baseline measurements and two acquisitions at approximately 45 and 120 min post-DCA infusion. All procedures were approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

MR Protocol

All measurements were performed using 3-T Signa MR scanner (40 mT/m gradient amplitude, 150 T/m/s slew rate; GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). A custom-built 13C surface coil (Øinner = 28 mm) operating at 32.1 MHz was used for both radiofrequency (RF) excitation and signal reception. A proton quadrature birdcage coil (Øinner = 70 mm) was used to acquire proton MR images for anatomical references.

A single-shot fast spin echo sequence (FSE, TR = 1492 ms, echo time (TE) = 38.6 ms, slice thickness = 2 mm, in-plane resolution = 0.47 mm) was used to acquire anatomical reference images in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes. Images acquired from a single-echo FSE (TR = 5000 ms, TE = 56.7 ms, slice thickness = 1 mm, in-plane resolution = 0.34 mm, matrix size = 256 × 192, echo train length = 8) in the axial plane were employed for coregistration with 13C metabolic maps. The homogeneity of the B0 field over the targeted brain region was optimized using a point-resolved spectroscopy sequence in which the line width of unsuppressed water signal was minimized by manually adjusting the linear shim currents.

In order to determine the timing of the acquisition window for the single time-point chemical shift imaging (CSI), metabolite time courses for [2-13C]Pyr and its products were acquired from one animal (Rat1) using a slice-selective free induction decay (FID) spectroscopy sequence with a spectral width of 10 kHz, 4096 spectral points, nominal 11.25° excitation flip angle, and 3 s of temporal resolution.

Metabolic maps were obtained from four animals (Rat2-5) using a single time-point phase-encoded FID CSI sequence (TR = 75 ms, field of view = 43.5 mm, matrix size = 16 × 16, spectral bandwidth = 10 kHz, 512 spectral points, total acquisition time = 19 s). A circularly-reduced k-space sampling scheme was used to shorten the scan time while a centric phase-encoding order with variable flip angle scheme, , was applied to reduce blurring [26]. Taken apodization into account, the in-plane voxel size, given by the integral of point spread function [27], was estimated as 3.8 × 3.8 mm2. However, it is difficult to quantify the exact voxel size due to the inhomogeneous excitation profile of the surface coil and the varying intensities of the measured metabolites. In particular, Pyr experiences an additional apodization effect due to its fast signal decay during the imaging window. Based on results from the time-course experiments, FID CSI data were acquired beginning 25 s after the start of the [2-13C]Pyr injection for maximum signal acquisition of [5-13C]glutamate (Glu) and [1-13C]acetylcarnitine (ALCAR). The center frequency was set to the resonance of Glu for both 13C pulse sequences to lessen the chemical-shift displacement artifact for the metabolites of interest. Slice thickness ranged from 6 to 8 mm in order to cover the part of the brain between the olfactory bulb and cerebellum for both slice-selective MRS and CSI.

Data Processing and Analysis

All 13C data were corrected for differences in polarization and dissolution-to-injection time, and processed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Data from the time-resolved slice-selective spectroscopy were apodized by a 10-Hz Gaussian filter, followed by zero-filling by a factor of 4 and a fast Fourier transform (FFT). The CSI data were apodized by a 30-Hz Gaussian filter and zero-filled by a factor of 4 in the spectral domain. The processed data were further apodized by a generalized Hamming window with α = 0.66, and zero-filled by a factor of 2 in the spatial domains, followed by 3D FFT.

For both the time-curves and metabolic maps, metabolites were quantified by integrating the respective peak in absorption mode after zero-order phase correction. For the display of spectra, both a zero- and a first-order phase correction were performed and the baseline roll was subtracted by fitting a spline to the signal-free regions of the smoothed spectrum.

The effect of DCA on metabolite levels was evaluated in a region of interest (ROI) in the brain, and a paired Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance. The spectra from voxels in the brain ROI were averaged, integrated over each metabolite peak, and divided by the integrated [2-13C]Pyr to calculate the metabolite ratios. Values are reported as mean ± standard error.

Results

[2-13C]Pyr had the highest polarization with a microwave irradiation at 94.076 GHz, which was about 4 MHz higher than the optimal irradiation frequency for [1-13C]Pyr. Whereas [2-13C]Pyr had a similar liquid-state polarization level (25.5 %) as [1-13C]Pyr (27.2 %), the T1 of [2-13C]Pyr in solution was considerably shorter (50 s) than the T1 of [1-13C]Pyr (63 s).

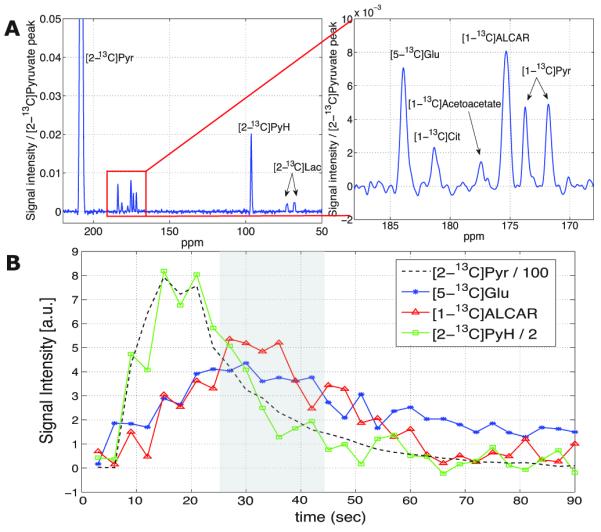

The spectrum shown in Fig. 1A acquired from an 8-mm slice through the brain (Rat1) was averaged over the first 20 time points of the dynamic acquisition and two post-DCA injections. Besides the substrate resonances of [2-13C]Pyr at 207.3 ppm and the [2-13C]Pyr hydrate (PyH) at 95.9 ppm, product resonances of [2-13C]Lac at 70.0 ppm, [5-13C]Glu at 183.4 ppm, and [1-13C]ALCAR at 172.3 ppm were observed. The spectrum is normalized to the [2-13C]Pyr peak. The Pyr doublet at 172.9 ppm was from natural abundance 13C (1.1 %) in the C1 position of the hyperpolarized substrate. The resonances detected at 180.8 ppm and 176.9 ppm were assigned to [1-13C]Cit and [1-13C]acetoacetate, respectively, based on their chemical shifts. The resonance of [2-13C]Ala, which has frequency at 52 ppm, was not detected. The time courses of [2-13C]Pyr, [2-13C]PyH, [5-13C]Glu, and [1-13C]ALCAR are shown in Fig. 1B. For the other resonances detected in the time-averaged spectrum, the SNR of the individual spectra was not sufficient to measure temporal changes. Compared to the time course of the other substrate resonances, which peaked around 15-20 s after the start of the injection, curves for the metabolic products Glu and ALCAR showed a slower build-up, reaching a broad maximum between 25 and 45 s. Hence, this interval was used as the acquisition window for the metabolic imaging acquisition. As the signal for Pyr and PyH continually decreased during this interval, a concentric phase encoding scheme was applied in the FID CSI experiments, leading to additional broadening of the point spread function for the substrates. The decay of the products, which is a combination of longitudinal relaxation and further metabolic conversion, appears to be slower for Glu than for ALCAR.

Figure 1.

(A) Time-averaged (3-60 s) spectrum from a slice through the brain of Rat1, and its zoomed spectrum, showing [5-13C]glutamate (Glu), [1-13C]citrate (Cit), [1-13C]acetoacetate, [1-13C]acetylcarnitine (ALCAR), and [1-13C]pyruvate (Pyr). (B) Time courses of [2-13C]Pyr (black--), [5-13C]Glu (blue*), [1-13C]ALCAR (redΔ), and [2-13C]pyruvate hydrate (PyH, green□) from the average of the pre- and post-dichloroacetate (DCA) data. The shaded area in the time course plot indicates the acquisition time window for single time-point 2D CSI.

Metabolic maps from a representative rat (Rat2) for [2-13C]Pyr, [5-13C]Glu, and [1-13C]ALCAR acquired pre- and post-DCA are shown in Figs. 2A-C. For each map, the data from two injections were averaged to increase the SNR. For the purpose of comparing between metabolite maps, the maximum signal intensity of each map in arbitrary units is displayed in the map after polarization correction. While Pyr levels remained similar, both Glu and ALCAR were higher after administration of DCA due to the increased conversion of Pyr to acetyl-CoA. However, whereas Glu was clearly detected in the brain, signal from ALCAR predominantly originated from muscle and/or lipid tissue surrounding the brain. Asymmetry in the maps, which is particularly visible for Pyr, is due to the slightly tilted orientation of the surface coil with respect to the animal’s head.

Figure 2.

Representative metabolite maps of (A) [2-13C]Pyr, (B) [5-13C]Glu, (C) [1-13C]ALCAR, acquired before and after DCA infusion from Rat2 using the single time-point 2D FIDCSI sequence. Each map was averaged over data from two injections. (E) Spectra of pre- and post-DCA from brain ROI shown in (D).

The effects of DCA are also illustrated in the pre- and post-DCA spectra (Fig. 2E) averaged over an ROI in the brain (Fig. 2D). The resonances of both Glu and ALCAR increased after DCA administration. Note that the ALCAR detected in the brain ROI is over-estimated because of partial volume effects from outside of brain due to the relatively low spatial resolution. With the higher SNR of the averaged spectra, even Cit could be detected in the brain and increased post-DCA. However, the Cit SNR from individual voxels was not sufficient to calculate a metabolic map. A quantitative analysis for Glu/Pyr showed an approximately 40% increase from 0.014 ± 0.004 to 0.020 ± 0.006 post-DCA (p = 0.02, n = 4). A trend to higher Cit/Pyr (from 0.002 ± 0.001 to 0.004 ± 0.002) was also found, but was not significant because of the low SNR (p = 0.11).

Discussion

In a previously published study using hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr to measure cerebral metabolism by Marjańska et al. [23], only [2-13C]Lac was observed as a metabolic product of Pyr. This was perhaps due to the relatively lower concentration of the injected substrate (35 mM) that limited the amount of Pyr crossing the blood brain barrier. In contrast, our study exploited the non-saturable component of Pyr transport into the brain [28] by using a higher Pyr concentration (125 mM). The presented results thus demonstrate for the first time the feasibility of using MRS of hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr to measure mitochondrial metabolism in rat brain in vivo.

In contrast to [1-13C]Pyr, the 13C label is retained during the conversion to acetyl-CoA, and the multiple metabolic pathways of the injected [2-13C]Pyr are briefly described in Fig. 3. First, the observation of ALCAR provides information regarding one possible metabolic fate of acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA in combination with carnitine inside of mitochondria can be converted to CoA and ALCAR via the enzyme carnitine acetyltransferase (CAT). The imaging data presented here suggest the dominant source of ALCAR labeling in these experiments is from tissue outside of the brain, however, given the relatively coarse spatial localization, we cannot definitely exclude the possibility that at least some of the ALCAR being produced in the brain. ALCAR in brain is mostly incorporated into fatty acids β-oxidation as well as carbohydrate metabolism [29, 30], which has a potential as a biomarker for assessing the fate of Pyr into fatty acid metabolism in mitochondria. Our observation of very little ALCAR labeling in the brain probably reflects the fact that the concentration of CAT is considerably lower in brain (12.3 μmol/min/g protein) than in skeletal muscle (410 μmol/min/g) [31].

Figure 3.

Metabolic pathways of [2-13C]Pyr and its observed downstream products (red). Glu and Cit can be biomarkers for the TCA cycle metabolism. The fate of the labeled carbon can be in ALCAR, which connects acetyl-CoA to β-oxidation of fatty acids in mitochondria, or acetoacetate in ketone-body metabolism.

Acetyl-CoA can be also involved in ketogenesis via acetyl-CoA acetyltransferases (ACAT). When glucose supply is not sufficient, e.g., starvation, acetoacetate becomes an alternative energy source of brain [32], which normally uses only glucose for energy. Unfortunately, the SNR of the acetoacetate peak was too low to provide spatial information. Thus, the source of the acetoacetate signal whether within or outside of the brain cannot be determined from these initial studies. While acetoacetate was only detected at just above noise level in the non-localized spectra in this study (Fig. 1A), future SNR improvements may allow this peak to serve as an imaging surrogate for cerebral ketone metabolism. Other literature results concerning 13C MRS detection of acetoacetate are mixed. While published rat heart spectra from Schroeder et al. [20] and Chen et al. [21] did not show a DCA-induced acetoacetate peak, those from Josan et al. [22] did.

The appearance of the [5-13C]Glu, which is in fast exchange with the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) [33], is most likely from acetyl-CoA being processed within the TCA cycle. Given that the TCA production of α-KG is accompanied by the generation of NADH, which is then further processed in the electron transport chain, the observed [5-13C]Glu peak may be a more accurate measure of oxidative phosphorylation in brain than Bic signal observed following the injection hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyr. However, neither α-KG itself nor any other intermediates besides Cit could be detected, probably due to small pool sizes and fast conversion within TCA cycle.

The SNR of the observed [5-13C]Glu in brain was sufficient to detect a 43 % increase in Glu/Pyr when the flux of Pyr to acetyl-CoA was increased after administration of DCA, whereas Schroeder et al. did not observe an increase in 13C-Glu production in a rat heart. This may reflect the heart’s higher CAT concentration (440 μmol/min/g protein) [31], making the enzyme readily available for converting the increased acetyl-CoA into ALCAR. In contrast, in brain, which has a much lower CAT concentration, the acetyl-CoA may be preferentially oxidized in the TCA cycle. The correlation between PDH flux and Glu labeling is an open area for investigation with Bic/Pyr and Glu/Pyr ratios potentially serving as surrogate markers for PDH activity and the TCA metabolism, respectively. However, care is needed when interpreting such studies. Whereas 13C-Bic produced from [1-13C]Pyr directly reflects PDH flux, changes in 13C-Glu labeling can reflect multiple processes. Modulation of TCA enzyme activities or differences Glu pool sizes can cause differences in the detected 13C-Glu signal even while 13C-Bic stays unchanged. Anaplerotic pathways from Pyr to the TCA cycle through oxaloacetate could be another factor that can affect the TCA cycle metabolism [34]. Indeed, the amount of Glu/Pyr increase is less than half compared to the approximately two-fold increase of Bic/Pyr in a similar experiment using hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyr [18]. The smaller DCA dose used in the current study (150 vs. 200 mg/kg) could have contributed to the difference, but the difference is probably also due to a loss of the labeled carbon signals via either T1 relaxation or metabolic conversion. For example, a portion of 13C can be released from the mitochondria as Cit to lipid synthesis, and a significant fraction of 13C-labeled α-KG could directly be oxidized to succinyl CoA via α-KG dehydrogenase (α-KGDH) rather than be incorporated into the Glu pool (Fig. 3). Moreover, the detected [1-13C]ALCAR and [5-13C]Glu could actually be from the same 13C label due to the fast exchange between the ALCAR and acetyl-CoA [19], which can also accelerate the signal decay through multiple enzyme-mediated reactions.

Because the majority of Pyr-derived acetyl-CoA may not be immediately taken up into the TCA cycle, hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr and the detected metabolic products in brain have many potential applications in studies of acetyl-CoA metabolism under various physiological conditions and disease models. For example, the mutated enzyme of isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) 1 in glioblastoma multiforme suppresses the reaction between isocitrate and α-KG, resulting in a depletion of α-KG [35]. Moreover, real time in vivo investigation of the TCA anion transport systems of succinate, Cit, malate, and α-oxoglutarate is also a potential application of [2-13C]Pyr [36]. Considering that the first ongoing human trial of [1-13C]Pyr on prostate patients has been successful [17], [2-13C]Pyr has much promise as the next hyperpolarizable substrate for human application.

Limitation

A main limitation of the presented study was the relatively small spectral bandwidth (2.3 kHz) of the slice-selective excitation pulse leading to considerable slice location offsets for some of the detected metabolites. Compared to [1-13C]Pyr and its metabolic products, the spectrum following the injection of hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr exhibits a much larger dispersion of chemical shifts from downstream products. The frequency difference between [2-13C]Pyr and [2-13C]Ala is more than seven times larger than the maximum frequency separation in the [1-13C]Pyr spectrum, which is approximately 700 Hz at 3 T between [1-13C]Lac and Bic (ignoring the usually non-detectable 13CO2 resonance). Therefore, the chemical shift displacement artifact (CSDA) is much more severe when using [2-13C]Pyr. Although the displacements from the target slice for [2-13C]Pyr at −2.7 mm (66.3 % overlap with the target slice), [1-13C]Cit at 0.3 mm (96.3 %), and [1-13C]ALCAR at 0.95 mm (88.1 %) are relatively small, the slice for [2-13C]Lac at 12.6 mm does not overlap at all. In combination with the B1 profile of the surface coil, the CSDA may explain why the signal for Lac and Ala, for which the slice is shifted even further, was too low to calculate metabolic maps. Note that the PyH-to-Pyr ratio of about 2 % is considerably lower than what expected at physiological pH. This is also likely due to the different slice location because of the CSDA. Similarly, a fraction of the detected ALCAR from brain tissue could be artificially high due to contribution from peripheral muscle and fat tissues in combination with CSDA and point spread function. In addition, the proton overlay image is acquired from a thinner slice (1 mm) than the CSI slice, resulting in muscle and fat tissue in the CSI slice from the more anterior part of the head. Potential solutions for the CSDA include 3D CSI using a hard pulse for excitation or metabolite-selective imaging [37]. Although fast spiral CSI [38] and EPSI [26] can shorten the 3D CSI’s long data acquisition time, appropriate spectral under-sampling might be necessary for fast 3D acquisitions as the higher acquisition speed is achieved at the expense of the spectral bandwidth [39]. Metabolite-selective imaging exploits spectrally selective RF pulses with varying excitation frequencies, but requires high selectivity and strong suppression in the stopband to avoid excitation of non-targeted metabolites.

Localized MRS measurements for dynamic changes of 13C-labeled Cit, Glu, ALCAR, and acetoacetate would be useful for a direct measure of the metabolites’ kinetics, however non-localized dynamic MRS spectra, as observed in this study, are of very limited value in brain due to differential contributions from different tissues/compartments, e.g., Pyr in vasculature, Glu in brain, ALCAR in muscle/fat. A limitation of these studies was that the metabolic maps were acquired with single time-point metabolic imaging that does not allow for the calculation of metabolic apparent conversion rates. It also makes the measurements more sensitive to experimental parameters such as injection time or bolus shape than dynamic imaging [40]. However, even when using acquisition techniques faster than the applied FID CSI, there is a trade-off between the number of temporal samples and the SNR at each measurement in hyperpolarized MRI. Therefore, higher SNR would be necessary for dynamic metabolic imaging. Strategies to increase the SNR comprise multi-channel receiver coils, proton decoupling [41], or higher substrate polarization, which can be achieved by polarizing at lower temperature [42] and/or higher field strength [43, 44].

Supraphysiological levels of Pyr are required for typical in vivo studies using hyperpolarized 13C-labeled Pyr for an adequate SNR. Although the high concentration of Pyr can suppress oxidation of other substrates, and thus, may have a significant effect on redox state and glycolysis, no hemodynamic event up to 10 mM of Pyr concentration has been reported [45] to date.

Conclusion

This study is the first report of in vivo observation of metabolic products of acetyl-CoA in brain after injection of hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr. These results extend the in vivo application of hyperpolarized Pyr to the investigation of brain mitochondrial metabolism via the assessment of the multiple possible metabolic fates of acetyl-CoA in healthy and diseased tissues. Moreover, hyperpolarized [2-13C]Pyr is potentially better suited to assess the efficacy of DCA as a cancer drug as it can provide a measure of both glycolytic and oxidative metabolism.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate for the support of National Institutes of Health (grants: EB009070, AA05965, AA018681, AA13521-INIA, and P41 EB015891), Department of Defense (grant: PC100427), the Lucas Foundation, and GE Healthcare.

Sponsors

NIH grants: EB009070, AA005965, AA018681, AA013521-INIA, and P41 EB015891 DOD grant: PC100427 The Lucas Foundation, GE Healthcare

Abbreviations

- Pyr

pyruvate

- Lac

lactate

- Ala

alanine

- Bic

bicarbonate

- Glu

glutamate

- ALCAR

acetylcarnitine

- Cit

citrate

- PyH

pyruvate hydrate

- Acetyl-CoA

acetyl coenzyme A

- DCA

dichloroacetate

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- PDH

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- PDK

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

- CSI

chemical shift imaging

- DNP

dynamic nuclear polarization

- FID

free induction decay

Reference

- 1.Gadian DG, Radda GK. NMR studies of tissue metabolism. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:69–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Graaf M. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy: basic methodology and clinical applications. Eur Biophys J. 2010 Mar;39(4):527–40. doi: 10.1007/s00249-009-0517-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarci K, Knopman DS, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Josephs KA, Boeve BF, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr. Alzheimer disease: postmortem neuropathologic correlates of antemortem 1H MR spectroscopy metabolite measurements. Radiology. 2008 Jul;248(1):210–20. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Stefano N, Filippi M. MR spectroscopy in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2007 Apr;17(Suppl 1):31S–35S. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2007.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan JW, Williamson A, Cavus I. Hetherington HP, Zaveri H, Petroff OA, Spencer DD. Neurometabolism in human epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 3):31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson SJ, Graves E, Pirzkall A, Li X, Antiniw Chan A, Vigneron DB, McKnight TR. In vivo molecular imaging for planning radiation therapy of gliomas: an application of 1H MRSI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002 Oct;16(4):464–76. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shulman RG, Rothman DL. 13C NMR of intermediary metabolism: implications for systemic physiology. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:15–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henry PG, Adriany G, Deelchand D, Gruetter R, Marjańska M, Oz G, Seaquist ER, Shestov A, Uğurbil K. In vivo 13C NMR spectroscopy and metabolic modeling in the brain: a practical perspective. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006 May;24(4):527–39. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ross BD, Higgins RJ, Boggan JE, Willis JA, Knittel B, Unger SW. Carbohydrate metabolism of the rat C6 glioma. An in vivo 13C and in vitro 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. NMR Biomed. 1988 Feb;1(1):20–6. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940010105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wijnen JP, Van der Graaf M, Scheenen TW, Klomp DW, de Galan BE, Idema AJ, Heerschap A. In vivo 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy of a human brain tumor after application of 13C-1-enriched glucose. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010 Jun;28(5):690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Fridlund B, Gram A, Hansson G, Hansson L, Lerche MH, Servin R, Thaning M, Golman K. Increase of signal-to-noise ratio of more than 10,000 times in liquid state NMR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(18):10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733835100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Petersson JS, Mansson S, Leunbach I. Molecular imaging with endogenous substances. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(18):10435–10439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1733836100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brindle KM, Bohndiek SE, Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI. Tumor imaging using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2011 Aug;66(2):505–19. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witney TH, Brindle KM. Imaging tumour cell metabolism using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010 Oct;38(5):1220–4. doi: 10.1042/BST0381220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park I, Larson PE, Zierhut ML, Hu S, Bok R, Ozawa T, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Vandenberg SR, James CD, Nelson SJ. Hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance metabolic imaging: application to brain tumors. Neuro Oncol. 2010 Feb;12(2):133–44. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Albers MJ, Bok R, Chen AP, Cunningham CH, Zierhut ML, Zhang VY, Kohler SJ, Tropp J, Hurd RE, Yen YF, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J. Hyperpolarized 13C lactate, pyruvate, and alanine: noninvasive biomarkers for prostate cancer detection and grading. Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 15;68(20):8607–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson SJ, Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron DB, Larson P, Harzstarck A, Ferrone M, Criekinge M, Chang J, Bok R, Park I, Reed G, Carvajal L, Crane J, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Chen A, Hurd R, Odegardstuen LI, Tropp J. International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Melbourne: May, 2012. Proof of Concept Clinical Trial of Hyperpolarized C-13 Pyruvate in Patients with Prostate Cancer; p. 0274. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JM, Recht L, Josan S, Jang T, Merchant M, Yen YF, Hurd RE, Spielman DM, Mayer D. Metabolic Response of Glioma to Dichloroacetate Measured by Hyperpolarized 13C MRSI. Neuro Oncol. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nos319. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Dodd MS, Lee P, Cochlin LE, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. The Cycling of Acetyl-Coenzyme A Through Acetylcarnitine Buffers Cardiac Substrate Supply: A Hyperpolarized 13C Magnetic Resonance Study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012 Mar 1;5(2):201–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.969451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeder MA, Atherton HJ, Ball DR, Cole MA, Heather LC, Griffin JL, Clarke K, Radda GK, Tyler DJ. Real-time assessment of Krebs cycle metabolism using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy. FASEB J. 2009 Aug;23(8):2529–38. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen AP, Hurd RE, Schroeder MA, Lau AZ, Gu YP, Lam WW, Barry J, Tropp J, Cunningham CH. Simultaneous investigation of cardiac pyruvate dehydrogenase flux, Krebs cycle metabolism and pH, using hyperpolarized [1,2-(13)C2]pyruvate in vivo. NMR Biomed. 2012 Feb;25(2):305–11. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Josan S, Park JM, Yen YF, Hurd RE, Pfefferbaum A, Spielman DM, Mayer D. International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Melbourne: May, 2012. In Vivo Investigation of Dicholoroacetate-Modulated Cardiac Metabolism in the Rat Using Hyperpolarized 13C MRS; p. 4322. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marjańska M, Iltis I, Shestov AA, Deelchand DK, Nelson C, Uğurbil K, Henry PG. In vivo 13C spectroscopy in the rat brain using hyperpolarized [1-(13)C]pyruvate and [2-(13)C]pyruvate. J Magn Reson. 2010 Oct;206(2):210–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stacpoole PW. The pharmacology of dichloroacetate. Metabolism. 1989;38(11):1124–44. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(89)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michelakis ED, Webster L, Mackey JR. Dichloroacetate (DCA) as a potential metabolic targeting therapy for cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(7):989–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yen YF, Kohler SJ, Chen AP, Tropp J, Bok R, Wolber J, Albers MJ, Gram KA, Zierhut ML, Park I, Zhang V, Hu S, Nelson SJ, Vigneron DB, Kurhanewicz J, Dirven HA, Hurd RE. Imaging considerations for in vivo 13C metabolic mapping using hyperpolarized 13C-pyruvate. Magn Reson Med. 2009 Jul;62(1):1–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golay X, Gillen J, van Zijl PC, Barker PB. Scan time reduction in proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of the human brain. Magn Reson Med. 2002 Feb;47(2):384–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hurd RE, Yen YF, Tropp J, Pfefferbaum A, Spielman DM, Mayer D. Cerebral dynamics and metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-(13)C]pyruvate using time-resolved MR spectroscopic imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010 Oct;30(10):1734–41. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones LL, McDonald DA, Borum PR. Acylcarnitines: role in brain. Prog Lipid Res. 2010 Jan;49(1):61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aureli T, Di Cocco ME, Puccetti C, Ricciolini R, Scalibastri M, Miccheli A, Manetti C, Conti F. Acetyl-L-carnitine modulates glucose metabolism and stimulates glycogen synthesis in rat brain. Brain Res. 1998 Jun 15;796(1-2):75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00319-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquis NR, Fritz IB. The distribution of carnitine, acetylcarnitine, and carnitine acetyltransferase in rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1965 May;240:2193–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y, Kuang Y, LaManna JC, Puchowicz MA. Contribution of brain glucose and ketone bodies to oxidative metabolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;765:365–70. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4989-8_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason GF, Gruetter R, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Shulman RG, Novotny EJ. Simultaneous determination of the rates of the TCA cycle, glucose utilization, alpha-ketoglutarate/glutamate exchange, and glutamine synthesis in human brain by NMR. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1995 Jan;15(1):12–25. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1995.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, Burgess SC. Flux through hepatic pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase detected by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Nov 22;108(47):19084–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111247108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, Mankoo P, Carter H, Siu IM, Gallia GL, Olivi A, McLendon R, Rasheed BA, Keir S, Nikolskaya T, Nikolsky Y, Busam DA, Tekleab H, Diaz LA, Jr, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Strausberg RL, Marie SK, Shinjo SM, Yan H, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Karchin R, Papadopoulos N, Parmigiani G, Vogelstein B, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008 Sep 26;321(5897):1807–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perkins M, Haslam JM, Linnane AW. Biogenesis of mitochondria. The effects of physiological and genetic manipulation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae on the mitochondrial transport systems for tricarboxylate-cycle anions. Biochem J. 1973 Aug;134(4):923–34. doi: 10.1042/bj1340923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lau AZ, Chen AP, Hurd RE, Cunningham CH. Spectral-spatial excitation for rapid imaging of DNP compounds. NMR Biomed. 2011 Oct;24(8):988–96. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Josan S, Spielman D, Yen YF, Hurd R, Pfefferbaum A, Mayer D. Fast volumetric imaging of ethanol metabolism in rat liver with hyperpolarized [1-(13) C]pyruvate. NMR Biomed. 2012 Aug;25(8):993–9. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer D, Levin YS, Hurd RE, Glover GH, Spielman DM. Fast metabolic imaging of systems with sparse spectra: application for hyperpolarized 13C imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Oct;56(4):932–7. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park JM, Josan S, Jang T, Merchant M, Yen YF, Hurd RE, Recht L, Spielman DM, Mayer D. Metabolite kinetics in C6 rat glioma model using magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging of hyperpolarized [1-(13) C]pyruvate. Magn Reson Med. 2012 Feb 14; doi: 10.1002/mrm.24181. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deelchand DK, Uğurbil K, Henry PG. Investigating brain metabolism at high fields using localized 13C NMR spectroscopy without 1H decoupling. Magn Reson Med. 2006 Feb;55(2):279–86. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Urbahn J, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Leach A, Stautner W, Zhang T, Clarke N. A closed cycle helium sorption pumpsystem and its use in making hyperpolarized compounds for MR Imaging; International Cryogenic Engineering Conference 22 and International Cryogenic Materials Conference; Seoul. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jannin S, Comment A, Kurdzesau F, Konter JA, Hautle P, van den Brandt B, van der Klink JJ. A 140 GHz prepolarizer for dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization. J Chem Phys. 2008 Jun 28;128(24):241102. doi: 10.1063/1.2951994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jóhannesson H, Macholl S, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH. Dynamic Nuclear Polarization of [1-13C]pyruvic acid at 4.6 tesla. J Magn Reson. 2009 Apr;197(2):167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moreno KX, Sabelhaus SM, Merritt ME, Sherry AD, Malloy CR. Competition of pyruvate with physiological substrates for oxidation by the heart: implications for studies with hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010 May;298(5):H1556–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00656.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]