Abstract

G-protein coupled receptors catalyze nucleotide exchange on G proteins, which results in subunit dissociation and effector activation. In the recent β2AR-Gs structure, portions of Switch I and II of Gα are not fully elucidated. We paired fluorescence studies of receptor-Gαi interactions with the β2AR-Gs and other Gi structures to investigate changes in Switch I and II during receptor activation and GTP binding. The β2/β3 loop containing Leu194 of Gαi is located between Switches I and II, in close proximity to IC2 of the receptor and the C-terminus of Gα, thus providing an allosteric connection between these Switches and receptor activation. We compared the environment of residues in myristoylated Gαi proteins in the heterotrimer to that upon receptor activation and subsequent GTP binding. Upon receptor activation, residues in both Switch regions are less solvent-exposed, as compared to the heterotrimer. Upon GTPγS binding, the environment of several residues in Switch I resemble the receptor-bound state, while Switch II residues display effects on their environment which are consistent with their role in GTP binding and Gβγ dissociation. The ability to merge available crystal structures with solution studies is a powerful tool to gain insight into conformational changes associated with receptor-mediated Gi protein activation.

Keywords: Gαi, Gi, Switch I/II, site-directed fluorescence, N-terminal myristoylation, α5 helix

Introduction

The structural determination of the β2AR in complex with Gs paints a stunning picture of the receptor-G protein complex (Rasmussen et al. 2011). Upon activation, the carboxy terminus (CT) of the G protein α subunit inserts into a hydrophobic pocket created by the outward movement of TM6 on the receptor. The structure confirms the CT of Gα as the major receptor interaction site on the G protein, previously implicated in many structural and functional studies (Hamm et al. 1988; Conklin et al. 1993; Dratz et al. 1993; Schwindinger et al. 1994; Natochin et al. 2000). For example, peptides derived from the C-terminus of Gα bind to activated receptors (Dratz et al. 1993; Liu et al. 1995; Brabazon et al. 2003; Scheerer et al. 2008) and compete with endogenous G proteins to turn off receptor signaling (Gilchrist et al. 2002). When a flexible 5-glycine linker is inserted into the CT of Gαi, this perturbs both the rate and extent of receptor-mediated G protein activation (Natochin et al. 2001; Marin et al. 2002; Oldham et al. 2006). Interestingly, the β2AR-Gs structure also implicated several other receptor contact sites on the G protein, in addition to the CT (Rasmussen et al. 2011), confirming some earlier studies on receptor coupling in a variety of Gα subtypes. These include the α4/β6 loop (Onrust et al. 1997; Bae et al. 1999; Cai et al. 2001) αN helix (Hepler et al. 1996; Blahos et al. 2001; Itoh et al. 2001; Preininger et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2010), and the β2/β3 loop (Ho et al. 2004). Switch I (Sw I) precedes the β2/β3 loop, and is next to linker residues which connect the GTPase and helical domains. Switch II (Sw II) is located on the other side of β2/β3 loop. Sw II participates in binding to Gβγ and effectors in a GTP-dependent and mutually exclusive manner. Thus, receptor-mediated conformational changes in Switch I and II have functional implications in the G protein cycle, from GDP release to GTP binding and Gβγ dissociation. This work examines the connection between receptor activation and changes in Sw I and II of myristoylated Gαi proteins.

Receptors catalyze GDP release from the G protein, and stabilize the nucleotide-free G protein. In the absence of an activated receptor, Gαi subunits exhibit a loss of structure in the nucleotide-free state (Tontson et al.; Thomas et al. 2012). Because properly folded Gαi proteins are difficult to isolate in the nucleotide-free state, proteins with mutations in the C-terminal α5 helix have been used to mimic the nucleotide-free state of the Gαi protein (Kapoor et al. 2009; Preininger et al. 2009). However, this approach reveals neither how the receptor prevents the unfolding of the nucleotide-free Gαi protein, nor how this conformation relates to subsequent GTP binding. From comparison of GDP-bound and GTPγS-bound Gα proteins, we know that GTP binding is accompanied by dramatic changes in Sw I and Sw II (Noel et al. 1993; Lambright et al. 1994; Sprang 1997), but the conformation of these regions in the receptor-bound complex is not completely known. This is because, in the β2AR-Gs structure, parts of Sw I are disordered, and the nanobody stabilizing the complex binds to a portion of Sw II (Rasmussen et al. 2011). In an effort to better understand changes in these regions, we use site-specific fluorescence to illuminate the environment of residues in Sw I and II during receptor activation and GTP binding at several distinct end states. First, we examined the environment of the residues in Sw I and II in the inactive heterotrimer, and then compared it to their environment in the receptor-bound, nucleotide-free state, and finally after addition of GTPγS to the G protein-receptor complex. We combined our fluorescence results with structural features available from Gαi and Gαs crystal structures in a hybrid fashion to learn more about how the receptor stabilizes the nucleotide-free state of the Gα protein, and how this relates to subsequent GTP binding.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression, labeling and purification

Construction, expression, and purification Gαi proteins were performed as described previously (Medkova et al. 2002; Preininger et al. 2003). Briefly, a parent Gαi lacking solvent-exposed cysteines (HI), which was previously shown to have properties similar to wild type (Medkova et al. 2002), was generated with an expression vector encoding rat Gαi, with the following amino acids substituted: (C66A-C214S-C305S-C325A-C351I), a hexahistidine tag inserted between amino acid residues M119 and T120 (Medkova et al. 2002; Van Eps et al. 2006). Wild-type Gαi proteins for supplementary experiment contained native residues throughout, except for mutations as indicated in S. Fig. 1 and the hexahistadine tag used to facilitate purification. Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA); DNA sequencing confirmed all mutations. Myristoylated proteins were obtained by co-expression with N-myristoyl transferase (NMT, with NMT vector generously provided by M. Linder, Washington University) and purified as detailed previously (Preininger et al. 2003). Coomassie staining of urea SDS PAGE gels (Mumby and Linder 1994) demonstrate Gαi proteins are fully myristoylated (Preininger et al. 2003) when co-expressed with the NMT vector. Purified proteins were stored at −80 °C in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 10 μM GDP, pH 7.5, and 10% (v/v) glycerol. After purification, all proteins used in this study were greater than 90% pure, as estimated by Coomassie staining of SDS-PAGE gels. The ability of the purified proteins to undergo activation-dependent changes was ascertained with intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (see below).

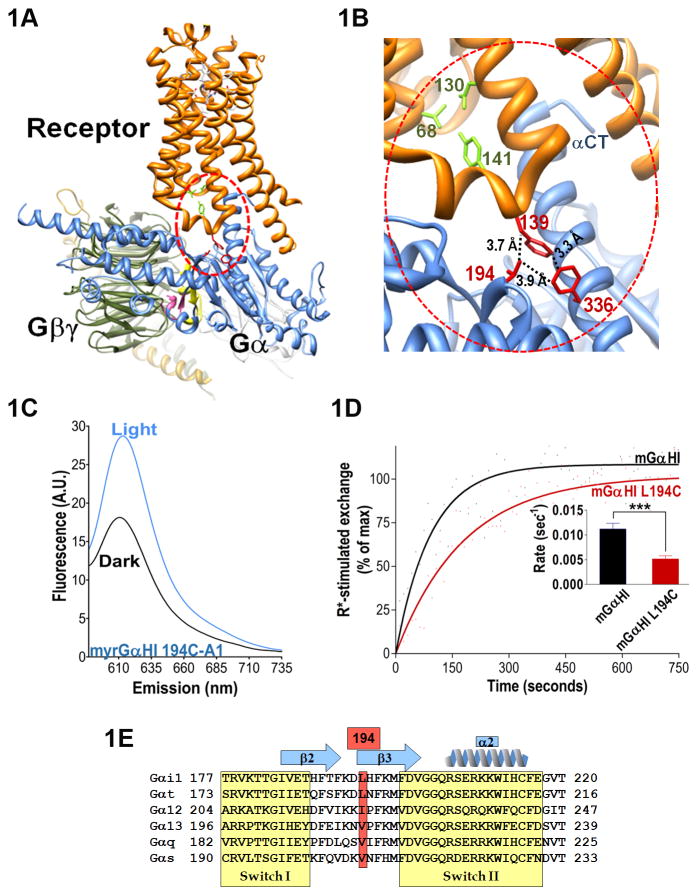

Fig. 1. Receptor-mediated changes in the β2/β3 loop.

A. Structure of the β2AR-Gs complex from PDB file 3SN6 (Rasmussen et al. 2011). Gαs is shown in blue, receptor in orange, Gβ in olive, Gγ gold, antibody fragments in grey. Sw I is shown in pink, Sw II in yellow. Red circle encompasses a hydrophobic triad of residues in close proximity to receptor’s DRY motif. B. Close up view of A, hydrophobic triad residues in red, and residues linked to conserved DRY motif in β2AR shown in green, indicated distances separating hydrophobic side chains shown with dotted lines. Residue D130 is part of the DRY motif (β2AR 130–132). Gα numbered according to homologous residue in Gαi (see Suppl. Table 1 for listing of homologous residues in Gαs vs. Gαi, β2AR vs. Rho). C. Emission of labeled Gαi protein in complex with Gβγ is scanned from 585–735 nm, with excitation at 580 nm, in the presence of either dark adapted (black) or light activated (blue) rhodopsin. D. Mutation of L194 significantly decreases the rate of receptor-mediated nucleotide exchange. Black, parent Gαi protein; red, L194C. Exchange is initiated by addition of excess GTPγs to unlabeled Gαi proteins (in complex with Gβγ) in the presence of light activated rhodopsin. Inset: quantitation of receptor mediated nucleotide exchange from at least 3 independent experiments (± S.E.M.). E. Sequences in Sw I and Sw II of indicated Gαi proteins were aligned using UniProt (UniProtConsortium), with Gα sequences followed by the UniProt identifiers: Gαi1 P603096, Gαt P11488, Gα12 Q03113, Gα13 Q14344, Gαq P50148, Gαs P63092). Secondary structure is depicted above sequences, and residue 194 from hydrophobic triad is outlined in red.

Preparation of rod outer segments (ROS) membranes containing bovine rhodopsin and Gβ1γ1: urea-washed rod outer segment membranes (ROS) containing dark-adapted rhodopsin were prepared as previously described (Mazzoni et al. 1991) and stored protected from light at −80 °C in buffer containing 10 mM MOPS, 200 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) and 100 μM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). Gβ1γ1 (hereafter referred to as Gβγ) was purified from bovine retina as described previously (Mazzoni et al. 1991) and stored in a buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME), pH 7.5, with 10% (v/v) glycerol.

Protein Labeling: Gαi HI proteins were labeled as described previously (Preininger et al. 2012) using a 10 molar excess of AlexaFluor 594C5-maleimide, (A1) (Invitrogen, WI), with a labeling time of 2 hours for Sw II proteins and 4 hours for Sw I proteins. Labeled proteins were purified via gel filtration HPLC, and fractions screened by intrinsic Trp fluorescence (or BD-GTPγS binding, in the case of W211C Gαi HI proteins, as described below) to ensure the functional integrity of the labeled proteins. Labeling efficiency was determined from comparison of Abs580 to protein concentration, as determined by Bradford, and found to be between 0.25–0.4 mollabel/molprotein, depending on the location of the residue and labeling time. The monodispersity and molecular weight of the monomeric, labeled proteins after HPLC gel filtration purification were confirmed through comparison of peak retention times and peak shape to a broad range molecular weight standard run on the same day as the purified samples (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). These labeled Gαi Hexa I proteins retain the ability to undergo activation-dependent changes, bind Gβγ, and couple to rhodopsin in ROS membranes (Medkova et al. 2002; Preininger et al. 2008).

Fluorescence Assays

Intrinsic Trp fluorescence: purified Gα proteins demonstrated > 40% increase in intrinsic Trp emission upon AlF4 activation, relative to emission in the GDP-bound state, as previously described (Mazzoni and Hamm 1993). Briefly, Gαi proteins (200 nM) in buffer A consisting of 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5 containing 10 μM GDP were monitored by fluorescence, with λex = 290 nm, λem = 345 nm, both before and after the addition of AlF4 (10 mM NaF and 50 μM AlCl3) using a Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorometer. For Gαi proteins containing a W211C mutation, the ability of the proteins to undergo activation-dependent changes was verified using BD-GTPγS Invitrogen (Madison, WI) as described previously (Hamm et al. 2009). Briefly, nucleotide exchange was measured as fold-increase in emission of 1 μM BODIPY-GTPγS (BD-GTPγS, λex = 490 nm, λem = 515 nm) in buffer containing 50 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 μM GDP, pH 7.5, at 21°C for 30 minutes after the addition of Gαi subunits (200 nM) to the cuvette containing BD-GTPγS. Tryptophan fluorescence of heterotrimeric Gαi proteins in the absence of receptors: indicated Gαi proteins (400 nM, unmyristoylated) were reconstituted with Gβγ (400 nM), and resulting heterotrimers were scanned with ex/em 280/340 both before and after activation with AlF4 (Suppl. Fig. 1).

Receptor-mediated fluorescence changes: labeled Gαi proteins were reconstituted with Gβγ at 4 °C prior to addition of excess dark ROS containing inactive rhodopsin, which was then transferred to a cuvette containing buffer A at a final concentration of 200 nM Gα protein, 250 nM Gβγ, and 2 μM dark-adapted rhodopsin. All manipulations involving dark rhodopsin were performed under dim red light to prevent its activation. The emission (dark spectra) from the cuvette containing dark-adapted ROS and A1-labeled subunits in complex with Gβγ was scanned between 590–750 nm with excitation at 580 nm at 21 °C using a Varian Cary Eclipse. After collecting dark spectrum, cuvettes were removed and subjected to a flash of light; light spectra were collected in duplicate 10 minutes after photo activation of rhodopsin. Finally, GTPγS spectra were collected in duplicate 10 minutes after addition of GTPγS (40 μM) to the light-activated sample in each cuvette. While duplicate readings were averaged for the light and GTPγS spectra, the dark spectrum was collected only once prior to light activation in order to avoid spurious activation of rhodopsin. Spectra average of three independent experiments (± S.E.M.) (Preininger et al. 2008).

Receptor-mediated nucleotide exchange rate: the rate of receptor-catalyzed GDP/GTPγS exchange was measured by monitoring the time-dependent increase in the Trp211 fluorescence (ex/em 290/340 nm) of Gαi HI proteins reconstituted with Gβγ (200 nM each) in buffer A- (lacking GDP) in the presence of 100 nM rhodopsin (light activated) at 21 °C (Oldham et al. 2006). Nucleotide exchange was initiated by the addition of GTPγS (10 μM). The data (average of 3 or more independent experiments) were normalized to the baseline (0%) and the fluorescence maximum (100%). The exchange rate was determined by fitting the data to an exponential association curve using Prism 4.0 (GraphPad Software).

Membrane binding assay

Rhodopsin binding assay: the ability of labeled Gαi proteins to bind rhodopsin in urea-washed ROS membranes was determined by a reconstitution assay. A1-labeled Gαi and Gβγ (5 μM each) were incubated together on ice for 30 minutes in buffer A- prior to adding light-activated rhodopsin (50 μM) to the reconstituted G protein sample. The samples were incubated with ROS for an additional 30 minutes, and an aliquot was further treated by addition of GTPγS (40 μM). Following 30 minutes incubation on ice, the membranes in each sample were pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000 X g for 1 hour, and supernatants removed from pellets. The isolated supernatant and pellet fractions were boiled, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and visualized with Coomassie blue (Preininger et al. 2008).

Structural depictions and statistical analyses

Molecular graphics images were produced using the UCSF Chimera package (Sanner et al. 1999; Pettersen et al. 2004) and PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (DeLano 2002). Graphs and statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA. Sequences were aligned with Clustal W using the human Gα sequences and accession codes as follows: Gαi1 P603096, Gαt P11488, Gα12 Q03113, Gα13 Q14344, Gαq P50148, Gαs P63092 (UniProtConsortium).

Results and Discussion

In order to examine changes within specific regions of the Gα subunit, we used a parent Gαi protein lacking solvent-exposed cysteines as a background for introduction of Cys residues at sites of interest. The parent Gαi protein, Gαi HI, and its labeled derivatives, binds to Gβγ and couples to rhodopsin in ROS membranes (Medkova et al. 2002; Preininger et al. 2003; Preininger et al. 2008). We labeled cysteine residues with the thiol-reactive AlexaFluor (A1) probe, and examined changes in the environment of the probe. These were measured first in the heterotrimeric state, in the presence of inactive, membrane bound receptors. We then compared the environment at each position to that in the receptor-bound, nucleotide-free, state, and finally to that in the GTPγS-bound state. The isolation of the activated G protein-receptor complex was facilitated by use of a nucleotide-free buffer and Gαi proteins in their myristoylated form. After addition of GTPγS to the receptor-bound complexes, the labeled Gαi proteins are released from receptors, and recovered in the soluble fraction (Preininger et al. 2008; Hamm et al. 2009). Throughout this study, this protocol was used to examine the environment of labeled residues during the G protein cycle. Because there is no crystal structure of a Gαi-receptor complex, or for any GDP-bound Gαs subunit, we have combined our solution studies of Gi proteins with existing Gi and Gs structures, to help better understand conformational changes that accompany activation in Sw I and II.

A triad of residues forms a hydrophobic pocket at the receptor-Gα interface

Structural determination of the β2AR-Gs complex shows residues in the β2/β3 loop in close proximity to the second intracellular loop (IC2) of the β2AR (Rasmussen et al. 2011). A conserved hydrophobic residue in IC2 (F139 in β2AR) occupies a position important for coupling of Gα subunits to class A GPCRs (Chen et al.; Moro et al. 1993; Wacker et al. 2008). In the structure of the complex, the density reveals IC2 residue F139 in close proximity to residues homologous to Gαi L194 and Gαi F336 (Fig. 1A–B, Gi numbering throughout)(Rasmussen et al. 2011), thus forming a triad of hydrophobic residues linking the receptor, the β2/β3 loop and CT of Gα (Fig 1A–B). To determine if receptor activation is communicated to changes in the β2/β3 loop in Gi proteins, we reconstituted fluorescently-labeled Gαi L194C protein (L194C-A1), with Gβ1γ1 (Gβγ), and incubated the heterotrimer with dark adapted rhodopsin (Rho) from rod outer segment (ROS) membranes. We scanned the emission of the inactive G protein from 590–750 nm in the presence of dark-adapted Rho (Fig. 1C, black trace) using excitation wavelength 580 nm, which does not activate Rho (Imamoto et al. 2000; Preininger et al. 2008). We next subjected the sample to a flash of light to activate receptors and re-scanned the sample (Fig. 1C, blue trace). The increased emission intensity of the from the labeled Gαi L194 upon receptor activation indicated a less polar environment for the A1 probe, consistent with increased packing (Imamoto et al. 2000; Harikumar et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2004; Preininger et al. 2008) surrounding Gαi L194 in the receptor-bound, nucleotide-free state.

To determine if mutation of Gαi L194 to Cys perturbs receptor-mediated G protein activation, we measured the GDP-GTPγS exchange rate in the presence of activated receptors. The rate of nucleotide exchange closely approximates the rate of GDP release, which is the rate-limiting step in G protein activation (Mukhopadhyay and Ross 1999). Mutation of Gαi Leu 194 to Cys significantly decreased the rate of receptor-mediated nucleotide exchange in the unlabeled protein (Fig. 1D, red), as compared to the parent protein containing the native Leu at position 194 (Fig. 1D, black). This is consistent with a role for Gαi 194L in receptor-mediated activation of Gi proteins.

The receptor contributes F139 to the hydrophobic triad of residues pictured in Fig. 1A–B. This Phe, located in IC2 of the receptor, is conserved across class A GPCRs, and is located next to an invariant Pro (Wacker et al. 2008), P138 in β2AR. This Pro likely helps to position Y141 in the IC2 helix for interaction with D130 in the DRY motif. This interaction also likely helps position F139 on the opposite side of the IC2 helix for interaction with the G protein (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, a Leu to Ser mutation of the residue homologous to Gαs F139 in a Gq-coupled class A GPCR, GPCR54, results in idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism (Wacker et al. 2008). Mutations of this residue to Asp or Glu even more dramatically impairs receptor-mediated G protein activation in vitro (Wacker et al. 2008), together underscoring the importance of a hydrophobic residue at this position for productive interaction with Gq family proteins. A similar role in Gi family proteins has yet to be established.

The receptor-mediated fluorescence changes we observed in Gαi L194C-A1, and the decreased rate of receptor-mediated exchange in the L194C mutant, may be a due to the interaction this residue makes with activated receptor, supporting a role for the β2/β3 loop in receptor interaction. The L194C mutation may also disrupt the allosteric connection to F336 in the C-terminal α5 helix, which itself is directly linked to receptor activation. The hydrophobic nature of Gαi L194 is conserved across G protein families (L, I or V), and F336 in the C-terminal α5 helix is absolutely conserved (Fig. 1E). While little is known about mutations of this residue in Gαi proteins, mutation of the homologous Phe in the C-terminus of monomeric G protein Ras disrupts the β1-β4 sheet network (Quilliam et al. 1995), accelerating the rate of nucleotide release. Likewise, a link between the α5 helix and β2/β3 loop is implicated in receptor-mediated activation of Gq proteins (Ho et al. 2004). Thus, the allosteric network of interactions surrounding this hydrophobic triad of residues may play important roles in receptor-mediated nucleotide release. Since the β2/β3 loop is located between Sw I and II (Fig. 1E), we next sought to determine if receptor activation was communicated to residues within Sw I.

Receptor-mediated changes in Sw I of Gα proteins

Sw I connects the helical and GTPase domains of Gα proteins, thus it is often referred to as the Sw I linker. Sw I consists of residues in the β2 strand in the GTPase domain plus residues making up the β2/αF loop which connects it to the helical domain. In the β2AR-Gs structure, the Sw I residues that are not a part of the β2 strand are disordered and therefore not visible in the structure (Rasmussen et al. 2011). To learn more about how domain separation, which is mediated by the Sw I linker, affects residues adjacent to this disordered region, we measured changes in emission intensity of labeled residues in Sw I of Gαi proteins before and after receptor activation (Fig. 2A, blue vs. black bars, as in 1C). The black bars (and black line) represent the maximal emission intensity of each respective residue in the inactive state, set to 1.0. These are set to 1.0 because the environment of each of the labeled residues in the heterotrimer is unique. Since the only difference between the dark and light samples is the flash of light used to activate receptors, the results shown in Fig. 2A reflect changes in the environment of each of the labeled as a result of receptor activation.

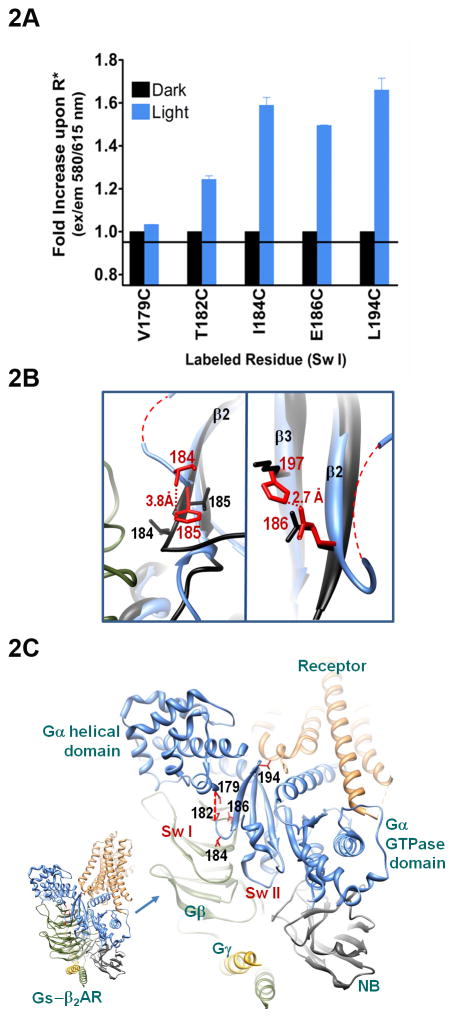

Fig. 2. Receptor-mediated changes in Sw I.

A. Maximal emission intensity as a result of receptor-mediated changes in the indicated labeled residues, blue bars, as compared to environment of the same labeled residue in the inactive, basal state (black bars). Data are the average of 2–3 independent experiments (+ S.E.M.). B. Residues I184 and VI185 in Gi heterotrimer shown in black (PDB file 1GP2 (Wall et al. 1995)) overlaid with GTPase domain of activated β2AR-Gs complex (PDB 3SN6), homologous residues in activated complex shown in red, Gi numbering throughout (see Suppl. Table 1). C. Overview of β2AR-Gs active complex from PDB file 3SN6. Gαi Sw I residues which were mutated to Cys and labeled are shown in red, inset is overview of complex. Red dashed line represents region of Sw I which is disordered in β2AR-Gs structure. NB refers to nanobody (antibody fragment) used to stabilize the activated complex, shown in light grey.

Residue V179C-A1 in the N-terminus of the Sw I linker, which is the first ordered residue flanking the disordered portion of the Sw I linker in the β2AR-Gs structure, displayed a relatively similar level of fluorescence both before and after light activation. This labeled protein, like all of the labeled proteins used in our study, retained the ability to undergo activation-dependent changes (see methods), thus the lack of environmental change reflects a relatively similar average polarity surrounding the probe before and after receptor activation. Farther up Sw I, nearer residues in the GTPase domain, we observed receptor-mediated enhancement in emission at all of the remaining positions tested (Fig. 2A), starting with Gαi T182. These results are consistent with increased packing throughout the Sw I region upon receptor activation. These results also rule out unfolding of the β2 strand upon receptor activation, as this would expose these residues to solvent, which would decrease, not increase emission from the labeled residues. To better understand the structural basis for the changes we observed in Sw I (Fig. 2A), we compared the conformation of Sw I in the Gi heterotrimer to the conformation of the homologous residues that were well ordered in the β2AR-Gs structure.

Despite the fact that the individual G protein structures used for comparison are at higher resolution than that of the complex, the individual residues in the β2AR-Gαs structure selected for structural comparisons with Gi proteins exhibited occupancy-weighted B factors which were within the average range for this structure (Kleywegt et al. 2004). This is a known metric used to judge the quality of crystal structures in the PDB (Brown and Ramaswamy 2007), and it was used, along with evaluation of the density at each position, to select residues for structural comparisons in this study. In the Gi heterotrimer, I184 and V185 point in opposite directions, with I184 oriented towards the inter-subunit space between Gα and Gβγ (Fig. 2B, left panel, black). Upon receptor activation, residues homologous to Gαi I184 and V185 (Gs I207 and F208), stack over one another (Fig. 2B, left panel, red, Gi numbering throughout, see Suppl. Table 1). The enhanced emission from Gαi I184C-A1 is consistent with the stacking of I184 over V185 upon receptor activation in the Gi-receptor complex. In the inactive Gi heterotrimer, the β2 strand is stabilized through hydrogen bonding with adjacent β strands (1GP2, (Wall et al. 1995)). However, in the receptor-bound state, the hydrogen bonding at the N terminus of the β2 is not present in the β2AR-Gs structure (Rasmussen et al. 2011), effectively shortening the β2 strand. The stacking of residues upstream of this region may help stabilize the folding of the β2 strand during the process of domain separation. This domain separation is likely a result of the loss of contacts between the domains upon interaction of the G protein with activated receptors, which is accompanied by a wide distribution of distances between the domains (Van Eps et al. 2011) and a high degree of flexibility overall (Abdulaev et al. 2006).

How might changes communicated from receptor to the β2 strand link to GDP release? While these experiments don’t address this question, one potential mechanism may involve destabilization of bound Mg+2, which is seen coordinated to GDP through its interactions with the conserved T181 in the crystal structure of Gαi-GDP-Mg+2 (Coleman and Sprang 1998). A role for Mg+2-mediated stabilization of GDP binding is implicated by the structure of Gαi T329A. This mutant exhibits a loss of coordination between T181 in Sw I and Mg+2 (Kapoor et al. 2009), and displays an elevated rate of basal nucleotide exchange, similar to that mediated by activated receptors. This same study demonstrated that low Mg+2 concentrations alone are sufficient to elevate rates of nucleotide exchange in wild-type Gαi proteins, again supporting the role of Sw I-Mg+2 interactions in maintaining high-affinity GDP binding. While it has long been known that Mg+2 is not required for GDP binding (Higashijima et al. 1987), it is not entirely unexpected that Mg+2 may promote GDP binding, given its role in GTP binding. Perturbation of Sw I’s coordination with the Mg+2-GDP binding site may help trigger nucleotide release in Gi proteins. This likely occurs in concert with disruption of the interface between the guanine ring and the base of the α5 helix, such as in the T329A mutant (Kapoor et al. 2009). In the visual system, Mg+2 binding may reduce conformational dynamics of Gαt that is normally associated with binding to activated receptors (Abdulaev et al. 2006). This NMR study demonstrated that, in the absence of activated receptors, the conformation of Mg+2-bound, GDP-free Gαt resembles that of GαtGDP, supporting a role for Mg+2 in stabilizing the inactive conformation of the Gαt protein.

Farther up the β2 strand are Gαi residues I184 and E186. These residues are absolutely conserved across G protein families, and mutations of these residues exert subtle effects on receptor-mediated nucleotide exchange (Oldham et al. 2007). Like I184C-A1, Gαi E186C-A1 exhibited increased emission upon receptor-mediated activation (Fig. 2A). While residues corresponding to Gαi E186 are themselves unaltered by activation (Fig. 2B, right panel), nearby residue homologous to Gαi K197, Gαs H220, is reoriented upon receptor activation. The density for Gαs H220 indicates the presence of a hydrogen bond between its ε-nitrogen and the nearby γ-carboxyl of E209 (Gαi E186). A similar reorientation of Gαi K197 may contribute to the enhanced fluorescence we detected for Gαi 186 in Fig. 2A. The enhanced fluorescence along the β2 strand may stabilize the β-sheet structure at the core of the GTPase domain during receptor mediated domain separation, mediated by linker residues N-terminal to the β2 strand. Since Sw II is located on the other side of the β2/β3 loop that contacts receptor, we next sought to determine if residues in Sw II sensed receptor activation.

Receptor-mediated changes in Sw II of Gαi proteins

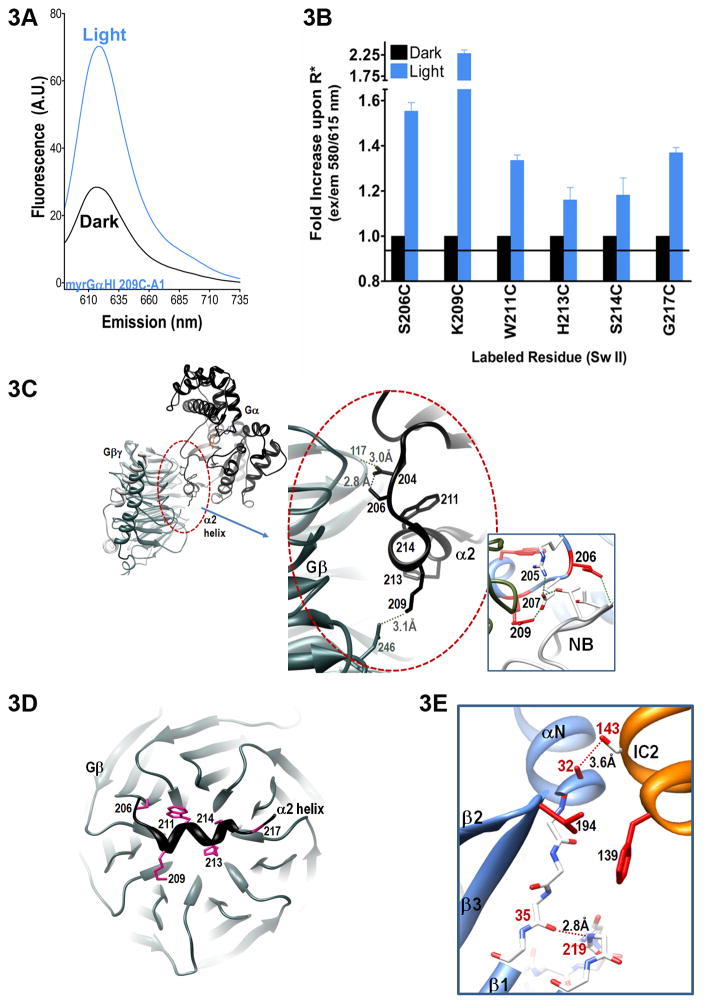

Because activation-dependent conformational changes in Sw II regulate binding to Gβγ and effectors in a mutually exclusive manner, and because of its location downstream of the β2/β3 loop, we next examined receptor mediated changes in Sw II. Sw II encompasses the α2 helix which is specifically involved in binding to Gβγ and contains Trp211, a well-conserved reporter of conformational changes in Gα proteins (Mazzoni et al. 1993; Lan et al. 1998). We labeled residues throughout this region, and found that Lys209C-A1 displayed a robust increase in emission upon receptor activation (Fig. 3A, blue vs. black line). Likewise, S206C-A1 also displayed a large increase in emission (Fig. 3B). The receptor-mediated increases for S206C-A1 and K209C-A1 ruled out a solvent-exposed orientation for these residues, which would result in decreased, not increased emission. We compared these fluorescence results to the structure of the Gi protein (Wall et al. 1995), and not to that of the activated complex, because of the extensive contacts that the nanobody makes with Sw II (Fig. 3C, right inset). In the Gi structure, residues K209 and S206 of Gαi are on the face of the α2 helix that contacts Gβγ (Fig. 3C, center, heterotrimer in black, corresponding to black in bar graphs). The increased emission that we detected for these two residues is consistent with enhanced packing between residues in the N-terminus of the α2 helix and Gβγ.

Fig. 3.

Receptor-mediated changes in Sw II of Gα proteins. A. Representative spectra of light dependent changes in Sw II, shown for K209C-A1, quantitated for all Sw II residues examined in B. B. Maximal emission intensity as a result of receptor-mediated changes in the indicated labeled residues, blue bars, as compared to environment of the same labeled residue in the inactive, basal state (black bars). Data are the average of 3 or more independent experiments (+ S.E.M.). C. Left inset: overview Gα–βγ interface in Gαβγ, (inactive GDP-bound heterotrimer, PDB file 1GP2). Gα shown in black, Gβγ in dark grey. Center: close up of the Gα–βγ interface in 1GP2, hydrogen bonds shown with dashed lines between indicated residues. Right inset: close up view of specific interactions between Sw II residues and antibody fragment (nanobody, NB) shown in light grey (PDB file 3SN6). D. Slab view of indicated residues in the α2 helix of Sw II, viewed from on top of the Gβγ barrel, with the remainder of Gα not shown for clarity. E. Close up view of interactions between backbone of residue 219 with the neighboring β1 strand, taken from the β2AR-Gs structure (PDB file 3SN6).

Midway through the α2 helix lies the well-known Trp involved in activation-dependent changes in Gα proteins, W211 in Gαi. Crystal structures of Gαi proteins activated by GTPγS and AlF4− positions W211 in a hydrophobic groove bounded by the α2 and α3 helices (Coleman et al. 1994; Berghuis et al. 1996). We observed an increase in emission of Gαi W211C-A1, which indicated increased packing surrounding this labeled residue upon receptor activation. Nearby residues H213C-A1 and S214C-A1 exhibited similarly modest increases in emission upon receptor activation (Fig. 3B). In the Gi structure, H213 and C214 are oriented towards the inter-subunit space between Gα and Gβγ subunits (Fig. 3C), directly over the central cavity of the Gβγ barrel (Wall et al. 1995; Lambright et al. 1996) (Fig. 3D). Taken together, the receptor-mediated increases in fluorescence throughout the α2 helix indicate a closely packed Sw II interface in the receptor-activated complex (Cherfils and Chabre 2003).

While an earlier spin-label study detected receptor-mediated changes at Gαi G217C (as well as at several positions in Sw I)(Oldham et al. 2007), the spin-labeled proteins did not detect receptor-mediated changes at other spin-labeled α2 helix residues (Van Eps et al. 2006), as might be expected upon binding to Gβγ. One reason for this may be that Gi proteins used in the current study are myristoylated, which enhances the affinity of Gα for Gβγ (Linder et al. 1991), while the previous spin-label study used unmyristoylated proteins. Another reason may be that although the smaller spin label is optimal for detecting backbone level fluctuations, the somewhat larger A1 probe (MWt. 900) is better able to sense packing between subunits. Both the spin and fluorescent probe detected changes at Gαi G217. The β2AR-Gs structure indicates that Gαi 217G is not likely in contact with the receptor, as the homologous Gs residue (D240) is more than 17 Å away from the nearest receptor contact. However, the amide hydrogen of neighboring T242 in Gαs is hydrogen bonded to the backbone carbonyl of R42 in Gαs, a residue homologous to Gαi K35 in the N terminus of Gαi. This backbone interaction replaces a similar backbone interaction between amide nitrogen of K35 with the carbonyl of A220 in Gαi prior to receptor activation (Wall et al. 1995). The new backbone interaction between residues homologous to K35 and A219 in Gαi more closely links Sw II to the N terminus in the receptor-bound complex (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, in the receptor-bound complex, residue 32 of in the N-terminus of Gαs is linked to the receptor through a van der Waals contact with S143, which lies adjacent to the receptor’s DRY motif. The interaction between the NT and receptor may propagate to a change in packing between Gαi K35 and A219 directly adjacent to Sw II, suggesting a conduit between activated receptors and Sw II of Gαi proteins. Consistent with this idea, receptor activation results in conformational changes in Sw II (as well as the C-terminus) of Gαt proteins (Ridge et al. 2006).

Changes in environment of Sw I residues upon receptor-mediated GTPγS binding

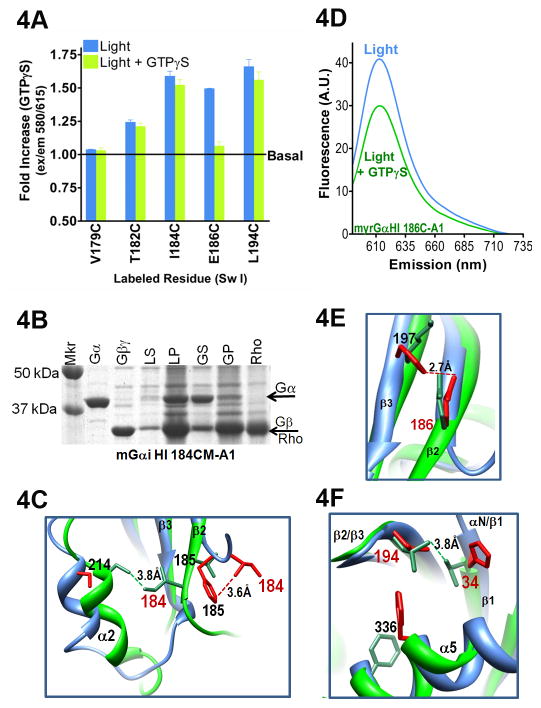

To determine how GTP binding alters the environment in Sw I, we added GTPγS to the activated Gi-receptor complexes and scanned the emission of the labeled proteins in the GTPγS-bound state. Our experimental approach recapitulates the sequence of events that occur during the G protein cycle at three discrete endpoints: heterotrimer (measured in the presence of inactive receptors, Fig. 4A, basal) receptor-bound, active complex (Fig. 4A, blue bars) and the soluble, GTPγS-bound state (Fig. 4A, green bars). Despite the ability of these proteins to undergo activation-dependent changes in Trp emission and partition to the soluble fraction on GTPγS binding (see methods), the environment of several Sw I residues after GTPγS binding mirrored their environment in the receptor-bound state (Fig. 4A, blue vs. green bars). Val 179C-A1 exhibited similar emission intensities in the inactive, receptor-bound and GTPγS-bound states (Fig 4A). This is consistent with the relatively solvent-exposed position for Gαi V179 seen in both the heterotrimer and GTPγS crystal structures, and its location adjacent to disordered residues in the receptor-bound Gs structure. The increase in emission intensity for T182C-A1 on binding GTPγS is higher than basal, and is similar to its emission in the receptor-bound state (Fig. 4A). This suggests a well-packed environment in both the receptor- and GTPγS-bound states at position 182. Because this position adjoins the disordered span of Sw I residues in the receptor-bound structure, we compared the environment of GαiT182 in the GαiGTPγS structure to the environment of this residue in the intact Gi protein. In the GTPγS-bound Gαi structure (Coleman et al. 1994), T182 is hydrogen bonded to the nearest side chain, E207. In the heterotrimer, T182 and E207 are nearly 17 Å apart, consistent with the relatively lower emission we detected for this labeled residue in the basal (heterotrimeric) state.

Fig. 4. Changes in Sw II upon receptor-mediated GTPγS binding.

A. Maximal emission intensity upon receptor-mediated GTPγS binding (green bars) to the light activated complexes (blue bars). Black line indicates maximal emission intensity in the inactive heterotrimer (basal). Data are the average of 3 or more independent experiments (± S.E.M.). B. Gαi labeled at residue 186 is membrane bound in the light activated state (LS, soluble fraction from light activation; LP, light, pellet fraction; GS, soluble fraction after addition of GTPγS to the light activated sample; GP, pellet fraction after GTPγS addition). C. Residues 184 and 214 interact in the GTPγS-bound Gαi (1GIA (Berghuis et al. 1996)), shown in green, as compared to the homologous residues in the β2AR-Gs structure (side chains in red). D. Representative trace of emission from labeled residue 186 before and after GTPγS binding. Receptor-bound, blue trace; GTPγS-bound, green trace. E. Residues homologous to Gαi 197 and 186 form a salt bridge in the β2AR-Gs activated complex (PDB 3SN6, side chains in red), in contrast to the position of these residues in the GαiGTPγS structure (PDB 1GIA), shown in green. F. Overlay of GαiGTPγS and Gαs from β2AR-Gs (PDB 1GIA and 3SN6, respectively), highlighting two residues in the hydrophobic triad, Gi 194 and 336, and a residue in the N terminus of Gi, V34, which makes a new hydrophobic contact with L194 upon GTPγS binding.

Likewise, we observed a similar environment of Gαi I184C-A1 before and after GTPγS binding (Fig. 4A). In the Gi structure, residue I184 is the first residue in the β2 strand. Like other A1-labeled Gαi proteins, Gαi I184C-A1 translocates to the soluble fraction on GTPγS binding (Fig. 4B). To gain insight into the structural changes responsible for the high level of fluorescence for residue 184 upon GTPγS binding, we compared the orientation of the homologous residue in the receptor-bound complex (Gs I207) to I184 in the GαiGTPγS structure. As shown in red in Fig. 4C (and 2B), the residue homologous to Gαi I184 stacks over an adjacent residue in the receptor-bound complex. In the GαiGTPγS structure, this stacked orientation is replaced by a van der Waals contact between I184 and C214 (Fig. 4C, green), thus explaining the well-packed environment for both of these residues upon GTPγS binding (Fig. 4A and Fig. 5A).

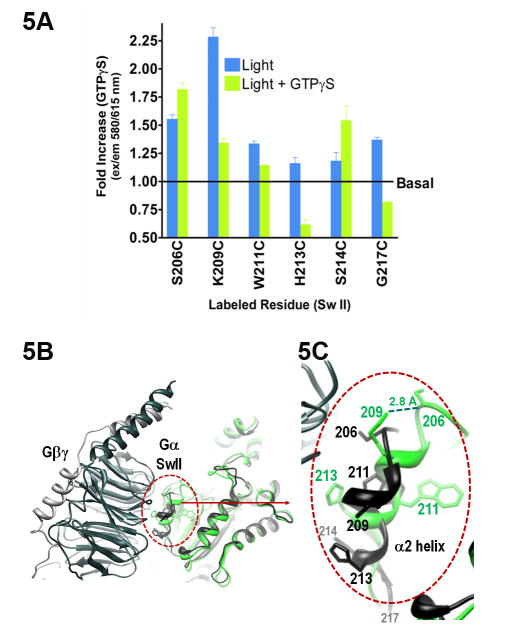

Fig. 5. Sw II changes due to receptor-mediated GTPγS binding.

A. Maximal emission intensity upon receptor-mediated GTPγS binding (green bars) to the light activated complexes (blue bars). Black line indicates maximal emission intensity in the inactive heterotrimer (basal). Data are the average of 3 or more independent experiments (+ S.E.M.). B. Overview of GTPγS bound Gαi (green, PDB file 1GIA) compared to Gαβγi heterotrimer (black, PDB file 1GP2). C. Close up view of the isolated Gα–βγ interface shown in B.

Farther up the β2 strand, Gαi E186 exhibited a drop in emission upon GTPγS binding (Fig. 4A, 4D), suggesting that GTP binding increases the solvent exposure at this position. In the Gi-GTPγS structure, E186 does not interact with K197, but in the β2AR-Gs structure, there is clear density supporting a salt bridge between the homologous residues, E209 and H220, prior to GTPγS binding (Fig. 4E, green vs. red, respectively). This is consistent with the decrease in emission of Gαi E186C-A1 upon GTPγS binding. Finally, at the top of the β2/β3 loop is L194, part of the hydrophobic triad pictured in Figs. 1A–B. This labeled residue maintained high emission intensity upon GTPγS binding (Fig. 4A). This was unexpected, given the loss of interaction with the receptor, as well as loss of interaction with CT residue F336 upon GTP binding, which moves the CT out of the receptor binding pocket. However, these losses are compensated by a new interaction with residue V34 in the αN/β1 hinge upon Gαi-GTPγS binding (Fig. 4F, green, GTPγS-bound vs. red, receptor-bound).

The interaction between αN/β1 hinge and the β2/β3 loop is reflected in the high emission of Gαi L194C-A1 in the GTPγS-bound state. However, since this interaction is also present in the structure of the Gi heterotrimer, it is not likely to be the only cause of the fluorescence we observed. Further investigation revealed that the CT influences the environment of the hinge region. To examine the relationship between the CT and αN/β1 hinge region, which makes van der Waals contact with residue 194 in the β2/β3 loop, we tested the ability of R to L mutation (R32L) in the hinge to mediate changes in a protein with a Trp mutation at the C terminus (L353W). We compared Trp emission in the inactive heterotrimers to Trp emission after activation with AlF4. This circumvents the need for receptor-mediated GDP/GTPγS exchange, as AlF4 directly complexes with bound GDP, forming a transition state mimetic of GTP (Coleman et al. 1994). It also allows direct comparison of heterotrimer vs. AlF4-activated states using Trp fluorescence. We found that while neither mutation alone had any effect on Trp fluorescence, the combination of these mutations significantly altered the activation-dependent change in Trp fluorescence (S. Fig. 1). This links the CT to the αN/β1 hinge region that contacts L194. While not conclusive, this indirectly supports an increased proximity to the CT upon GTPγS binding (as compared to the basal state), which likely contributes to the relatively high fluorescence of Gαi L194C-A1-GTPγS.

We do not know the reason for the similarly high emission of Sw I residues in the receptor-bound and GTPγS bound states. The enhanced packing of Sw I residues in the receptor-bound state may help stabilize the protein in the absence of nucleotide, given its location adjacent to the linker which mediates domain separation. Maintaining a solvent-restricted environment in the receptor-bound state may also be energetically favorable in terms of subsequent GTP binding, as it circumvents a desolvation penalty that would otherwise be associated with bringing GTP-Mg+2 into a hydrated binding site. The maintenance of the environment from receptor-bound to GTP-bound state is consistent with the observed kinetics of GTP binding, which quickly follows the rate-limiting step of GDP release. Because the binding of GTP is sensed by Sw II, we next examined the environment of Sw II residues upon GTPγS binding.

Changes in environment of Sw II residues upon receptor-mediated GTPγS binding

The activation-dependent reorganization of Sw II upon GTPγS binding influences the residues in the α2 helix in a position-specific manner. When GTPγS was added to the receptor-bound complexes, both Gαi S206C-A1 and K209C-A1 maintained elevated levels of emission intensity (Fig. 5A). Comparing emission of these residues in the GTPγS-bound state, where the structure is known, to emission in the receptor-bound state, where the environment of these residues is obscured by the nanobody, provides valuable insights into conformational changes associated with activation in the Sw II region.

Because the nanobody binds portions of Sw II, we used the structure of the Gi heterotrimer, PDB file 1GP2, to help visualize the Sw II and the Gα-Gβγ interface prior to GTP binding. In the Gi heterotrimer, residues S206 and K209 are more than 10 Å apart from each other (Fig. 5B–C, black). After GTPγS binding, there is an activation-dependent increase in proximity between 206 and 209 (Fig. 5B–C, green) due to hydrogen bonding between the positively charged side chain of K209 and the backbone carbonyl of S206. The fluorescent probe on S206C provides a convenient reporter of this increased proximity. The enhanced emission from K209C-A1 upon GTPγS binding suggests that this labeled residue senses the GTP-dependent reorganization of Sw II, which brings K209 into close proximity with S206 (Fig. 5B–C).

Farther up the Sw II α2 helix, we observed a modest increase in Gαi W211C-A1 and S214C-A1 upon binding to GTPγS, compared to basal (Fig. 5A, green bar vs. black line). Trp211, a well-known reporter of activational changes in Gα, is oriented towards the core of the protein in both the heterotrimer and the GTPγS-bound states (Fig. 5B–C). Note that the folding of W211C-A1 was confirmed using a fluorescently labeled GTPγS analog, since mutation of the native Trp precludes use of the Trp activation assay (see methods). We used this approach since Bodipy-labeled GTPγS exhibits a time-dependent increase in fluorescence on binding to Gα that mirrors the GTPγS-dependent increase in W211 in the unlabeled parent protein (Preininger et al. 2012). Although we selected mainly solvent-exposed positions for site-directed labeling in this study, W211 is oriented towards the core of the protein, and activation by GTPγS increases the packing of this residue within the α2-α3 binding pocket. While the 5-carbon spacer linking the thiol to the fluorescent moiety facilitates flexibility of the probe, the α2-α3 pocket may not accommodate a fluorophore as well as other, more solvent exposed positions. Nevertheless, the activation-dependent increase in fluorescence we observed in GαiW211C-A1 indicates that the increased packing of this labeled residue against the core of the protein is likely maintained through GTPγS binding. As mentioned previously in connection with Sw I residue 184, Gαi S214C-A1 shows an enhanced emission in the GTPγS-bound state (Fig. 5A). Again, this is consistent with the interaction between C214 and I184 seen in the crystal structure of GαiGTPγS (Fig. 4C, green). On the other hand, positions H213 and G217 in Gαi both exhibit a decrease in emission intensity upon GTPγS binding (Fig. 5A, green bars). In the GαiGTPγS structure, H213 is solvent-exposed upon dissociation from Gβγ (Fig. 5C, green). The drop in emission that we observe at position 213 suggests that the contacts with Gβγ are reduced or eliminated upon GTPγS binding. Likewise, the decreased emission exhibited by G217C-A1 upon binding GTPγS (Fig. 5A) indicates an increase in solvent exposure for G217, consistent with a loss of packing between neighboring Gαi G219 and the αN/β1 hinge (Fig. 3E).

It is important to note that, unlike GDP-bound Gαs, for which there are no high resolution structures, there are several structures for GTPγS-bound Gαs. Comparison of GαsGTPγS from 1AZT (Sunahara et al. 1997) revealed that the Gαs residues are similar in their respective orientations as the homologous residues in Gαi pictured in Figs. 4 and 5 in green. In the case of Gαs H220, homologous to Gαi K197 (Fig. 4e, green), H220 of Gαs is hydrogen bonded to a solvent phosphate ion in the GαsGTPγS structure. Despite this artifact, the distance between Gαs 209 and 220 (Gαi 186 and 197, respectively) increases after GTPγS binding, qualitatively consistent with the drop in emission we observe in the homologous residue in Gαi (E186) upon GTPγS binding. While the β2AR-Gs structure is the first of an activated receptor in complex with a G protein, the use of stabilizing proteins may alter native conformation, especially in regions of direct contact. However, site-specific labeling has its own drawbacks. Backbone conformational changes may result in detection of changes in environment not sensed by a native residue, due to the larger radius of detection of the fluorescent probe. Furthermore, since the emission represents the average environment of the probe, fluorescence may not be particularly informative in highly flexible and disordered regions of the protein. Nevertheless, these site-specific labeling experiments provide additional information regarding the environment of regions which are not completely elucidated in the structure. Together with the high resolution structures of individual G proteins, this work highlights the sequential changes in Switch regions of Gα that occur upon receptor activation and GTP binding (Fig. 6).

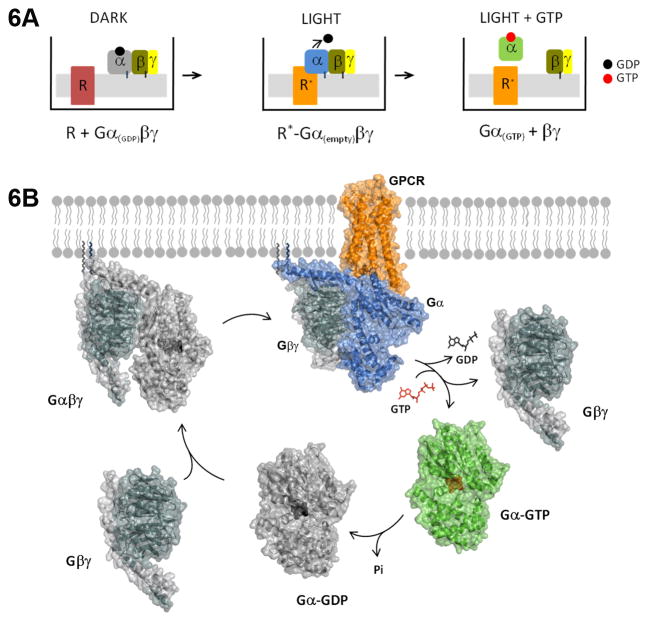

Fig. 6. Schematic and model.

Top panel represents experimental protocol, corresponding to discrete steps in the G protein cycle, modeled in the bottom panel. Inactive receptor, red; active receptor, orange; Gαβγ-GDP, black and grey; nucleotide-free Gα (Gαβγ.0), blue, with Gβγ in black and grey; GαGTP, green; GTP, red; GDP, black.

The observed changes in Sw II upon GTP binding can be understood within the context of the canonical view of the G protein cycle, including GTP-dependent Gα–βγ dissociation (schematic, Fig. 6A and model, 6B). Receptor activation results in the nucleotide-free, empty pocket Gα subunit, in complex with Gβγ and receptor, which stabilizes the high affinity state of the receptor. Subsequent GTP binding to Gα results in its dissociation from both receptors and Gβγ, each competent to activate their respective downstream effectors. Hydrolysis of bound GTP returns the Gα to the GDP-bound state, leading to Gβγ reassociation, with the G protein poised for a new round of activation. While several studies have indicated that GαGTP and Gβγ subunits may remain tethered (Frank et al. 2005; Ridge et al. 2006), our results do not support an interaction between Sw II of Gαi and Gβγ upon GTP binding to Gα. However, further studies with specifically labeled Gα and Gβγ subunits may reveal tethering through other regions of Gα, or a possible tethering through distinct scaffold proteins. Importantly, while Gαs and Gαi are not likely to be identical in many regions of their structure, the conformations of the Sw I and II residues depicted in the GαiGTPγS structure (Coleman et al. 1994) were qualitatively reproduced in the GαsGTPγS structure (Sunahara et al. 1997). The similarities between Sw I and II in the Gαs and Gαi GTPγS-bound structures likely reflect the conserved nature of these Switch regions in all Gα proteins.

4.0 Conclusion

The current study follows the environment of Sw I and II residues upon receptor activation and subsequent GTP binding during the G protein cycle. Receptor activation is allosterically communicated to Sw I and Sw II through a hydrophobic triad of residues. These originate from a residue homologous to F139 in IC2 of the β2AR, and Gαi residues 194 in the β2/β3 loop and F336 in the C-terminal α5 helix. Of all the residues in Sw I and Sw II examined, only Gαi L194 is close enough to make direct receptor contact, according to homologous residues in the β2AR-Gαs complex. Another contributor to the hydrophobic triad is F336 of Gαi. Receptor activation and translocation of the C-terminal α5 helix into the receptor binding pocket brings F336 into proximity with L194 of Gαi and F139 of the IC2 loop of the receptor. The residue Gαi L194 that is linked to receptor activation is located in the β2/β3 loop that is sandwiched between Sw I and Sw II. Our fluorescence results suggest that receptor activation is accompanied by enhanced packing within the β2 strand of Sw I. This may serve to stabilize Sw I during separation of helical and GTPase domains, mediated by residues N-terminal to the β2 strand. Consistent with structures of isolated Gα proteins in the activated state, GTPγS binding stabilizes the relative orientation between the domains. In our experiments, the environment of Sw I residues observed in the receptor-activated state was maintained upon subsequent GTPγS binding. Downstream from the β2/β3 loop, labeled residues in Sw II display increased packing upon receptor activation, followed by position-specific changes upon GTPγS binding. The GTP-dependent changes in Sw II reflect reorganization of this region that occurs upon GTP binding and Gβγ dissociation. The receptor-mediated changes in Sw I and Sw II may help preserve the folding of the protein in the nucleotide-free state, stabilizing the protein for fast, efficient GTP binding to the receptor-bound Gα protein. The current study combines results from solution studies with insights from crystal structures to reveal new details associated with the sequence of conformational changes in Sw I and Sw II that occur during receptor activation and subsequent GTP binding to Gi proteins.

Supplementary Material

Gαiβγ proteins containing either no mutation (WT) or indicated residues mutated were assayed before and after activation with AlF4, in the absence of receptors, and fluorescence shown as percent increase in Trp emission after activation with AlF4. Data are the average of 3 independent experiments (± S.E.M.).

Gαi and Gαs homology (left) (Chung et al. 2011); Rho and β2AR homology (right)(Gregory et al.).

Acknowledgments

Research reported here was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants EY006062 and GM095633 (to H.E.H.). The authors gratefully acknowledge helpful discussions with Drs. T. M. Iverson and V. V. Gurevich and, and thank G. Liao and S. Meier for technical assistance. We also thank R. A. Tracy for proofreading the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abdulaev NG, et al. The receptor-bound “empty pocket” state of the heterotrimeric G-protein alpha-subunit is conformationally dynamic. Biochemistry. 2006;45(43):12986–97. doi: 10.1021/bi061088h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae H, et al. Two Amino Acids Within the α4 Helix of Gαi1 Mediate Coupling with 5-Hydroxytryptamine1B Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(21):14963–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghuis AM, et al. Structure of the GDP-Pi complex of Gly203→Ala Giα1: a mimic of the ternary product complex of Gα-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis. Structure. 1996;4(11):1277–90. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blahos J, et al. A Novel Site on the Gα-protein That Recognizes Heptahelical Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(5):3262–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004880200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabazon DM, et al. Evidence for Structural Changes in Carboxyl-Terminal Peptides of Transducin α-Subunit upon Binding a Soluble Mimic of Light-Activated Rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 2003;42(2):302–11. doi: 10.1021/bi0268899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EN, Ramaswamy S. Quality of protein crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2007;63(Pt 9):941–50. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907033847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai K, et al. Mapping of contact sites in complex formation between transducin and light-activated rhodopsin by covalent crosslinking: Use of a photoactivatable reagent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(9):4877–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XP, et al. Structural determinants in the second intracellular loop of the human cannabinoid CB1 receptor mediate selective coupling to G(s) and G(i) Br J Pharmacol. 161(8):1817–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01006.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherfils J, Chabre M. Activation of G-protein Gα subunits by receptors through Gα–Gβ and Gα–Gγ interactions. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2003;28(1):13–7. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung KY, et al. Conformational changes in the G protein Gs induced by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. Nature. 2011;477(7366):611–5. doi: 10.1038/nature10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DE, et al. Structures of Active Conformations of Giα1 and the Mechanism of GTP Hydrolysis. Science. 1994;265(5177):1405–12. doi: 10.1126/science.8073283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DE, Sprang SR. Crystal Structures of the G Protein Giα1 Complexed with GDP and Mg2+: A Crystallographic Titration Experiment. Biochemistry. 1998;37(41):14376–85. doi: 10.1021/bi9810306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin BR, et al. Substitution of three amino acids switches receptor specificity of Gqα to that of Giα. Nature. 1993;363(6426):274–6. doi: 10.1038/363274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dratz EA, et al. NMR structure of a receptor-bound G-protein peptide. Nature. 1993;363(6426):276–81. doi: 10.1038/363276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank M, et al. G Protein Activation without Subunit Dissociation Depends on a Gαi-specific Region. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(26):24584–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414630200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist A, et al. G alpha COOH-terminal minigene vectors dissect heterotrimeric G protein signaling. Sci STKE. 2002;2002(118):PL1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.118.pl1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory KJ, et al. Allosteric modulation of metabotropic glutamate receptors: structural insights and therapeutic potential. Neuropharmacology. 60(1):66–81. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm HE, et al. Site of G protein binding to rhodopsin mapped with synthetic peptides from the alpha subunit. Science. 1988;241(4867):832–5. doi: 10.1126/science.3136547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm HE, et al. Trp fluorescence reveals an activation-dependent cation-pi interaction in the Switch II region of Galphai proteins. Protein Sci. 2009;18(11):2326–35. doi: 10.1002/pro.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harikumar KG, et al. Environment and mobility of a series of fluorescent reporters at the amino terminus of structurally related peptide agonists and antagonists bound to the cholecystokinin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(21):18552–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepler JR, et al. Functional Importance of the Amino Terminus of Gqα. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(1):496–504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashijima T, et al. Effects of Mg2+ and the βγ-Subunit Complex on the Interactions of Guanine Nucleotides with G proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(2):762–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho MK, et al. Identification of a stretch of six divergent amino acids on the α5 helix of Gα16 as a major determinant of the promiscuity and efficiency of receptor coupling. Biochemical Journal. 2004;380(Pt 2):361–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, et al. Structural basis of G protein-coupled receptor-G protein interactions. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(7):541–8. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto Y, et al. Light-induced conformational changes of rhodopsin probed by fluorescent alexa594 immobilized on the cytoplasmic surface. Biochemistry. 2000;39(49):15225–33. doi: 10.1021/bi0018685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, et al. Mapping of contact sites in complex formation between light-activated rhodopsin and transducin by covalent crosslinking: Use of a chemically preactivated reagent. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(9):4883–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051632998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor N, et al. Structural evidence for a sequential release mechanism for activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. J Mol Biol. 2009;393(4):882–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ, et al. The Uppsala Electron-Density Server. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60(Pt 12 Pt 1):2240–9. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904013253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambright DG, et al. Structural determinants for activation of the α-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature. 1994;369(6482):621–8. doi: 10.1038/369621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambright DG, et al. The 2.0 Å crystal structure of a heterotrimeric G protein. Nature. 1996;379(6563):311–9. doi: 10.1038/379311a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KL, et al. Roles of G(o)alpha tryptophans in GTP hydrolysis, GDP release, and fluorescence signals. Biochemistry. 1998;37(3):837–43. doi: 10.1021/bi972122i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder ME, et al. Lipid modifications of G protein subunits. Myristoylation of Go alpha increases its affinity for beta gamma. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(7):4654–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, et al. Identification of a receptor/G-protein contact site critical for signaling specificity and G-protein activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(25):11642–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin EP, et al. Disruption of the α5 Helix of Transducin Impairs Rhodopsin-Catalyzed Nucleotide Exchange. Biochemistry. 2002;41(22):6988–94. doi: 10.1021/bi025514k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni MR, Hamm HE. Tryptophan207 is involved in the GTP-dependent conformational switch in the alpha subunit of the G protein transducin: chymotryptic digestion patterns of the GTP gamma S and GDP-bound forms. J Protein Chem. 1993;12(2):215–21. doi: 10.1007/BF01026043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni MR, et al. Structural Analysis of Rod GTP-binding Protein, Gt. Limited Proteolytic Digestion Pattern of Gt with Four Proteases Defines Monoclonal Antibody Epitope. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266(21):14072–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medkova M, et al. Conformational Changes in the Amino-Terminal Helix of the G Protein αi1 Following Dissociation from Gβγ Subunit and Activation. Biochemistry. 2002;41(31):9962–72. doi: 10.1021/bi0255726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro O, et al. Hydrophobic amino acid in the i2 loop plays a key role in receptor-G protein coupling. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(30):22273–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay S, Ross EM. Rapid GTP binding and hydrolysis by Gq promoted by receptor and GTPase-activating proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(17):9539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby SM, Linder ME. Myristoylation of G-protein alpha subunits. Methods Enzymol. 1994;237:254–68. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)37067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natochin M, et al. Probing the mechanism of rhodopsin-catalyzed transducin activation. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;77(1):202–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.t01-1-00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natochin M, et al. Rhodopsin Recognition by Mutant Gsα Containing C-terminal Residues of Transducin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2000;275(4):2669–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel JP, et al. The 2.2 Å crystal structure of transducin-α complexed with GTPγS. Nature. 1993;366(6456):654–663. doi: 10.1038/366654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham WM, et al. Mechanism of the receptor-catalyzed activation of heterotrimeric G proteins. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2006;13(9):772–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham WM, et al. Mapping allosteric connections from the receptor to the nucleotide-binding pocket of heterotrimeric G proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):7927–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702623104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onrust R, et al. Receptor and βγ Binding Sites in the α Subunit of the Retinal G Protein Transducin. Science. 1997;275(5298):381–4. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5298.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–12. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger A, et al. Helix dipole movement and conformational variability contribute to allosteric GDP release in Gi subunits. Biochemistry. 2009;48(12):2630–2642. doi: 10.1021/bi801853a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger AM, et al. Myristoylation exerts direct and allosteric effects on Galpha conformation and dynamics in solution. Biochemistry. 2012;51(9):1911–24. doi: 10.1021/bi201472c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger AM, et al. Receptor-mediated changes at the myristoylated amino terminus of Galpha(il) proteins. Biochemistry. 2008;47(39):10281–93. doi: 10.1021/bi800741r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger AM, et al. The Myristoylated Amino Terminus of Gαi1 Plays a Critical Role in the Structure and Function of Gαi1 Subunits in Solution. Biochemistry. 2003;42(26):7931–41. doi: 10.1021/bi0345438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quilliam LA, et al. Biological and structural characterization of a Ras transforming mutation at the phenylalanine-156 residue, which is conserved in all members of the Ras superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(5):1272–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen SG, et al. Crystal structure of the beta(2) adrenergic receptor-Gs protein complex. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridge KD, et al. Conformational Changes Associated with Receptor Stimulated Guanine Nucleotide Exchange in a Heterotrimeric G-Protein a-subunit: NMR Analysis of GTPγS-Bound States. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:7635–48. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanner MF, et al. Integrating computation and visualization for biomolecular analysis: an example using python and AVS. Pac Symp Biocomput. 1999:401–12. doi: 10.1142/9789814447300_0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheerer P, et al. Crystal structure of opsin in its G-protein-interacting conformation. Nature. 2008;455(7212):497–502. doi: 10.1038/nature07330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwindinger WF, et al. A Novel Gsα Mutant in a Patient with Albright Hereditary Osteodystrophy Uncouples Cell Surface Receptors from Adenylyl Cyclase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(41):25387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith WC, et al. The surface of visual arrestin that binds to rhodopsin. Mol Vis. 2004;10:392–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang SR. G Protein Mechanisms: Insights from Structural Analysis. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 1997;66:639–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara RK, et al. Crystal Structure of the Adenylyl Cyclase Activator Gsα. Science. 1997;278(5345):1943–7. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CJ, et al. The nucleotide exchange factor Ric-8A is a chaperone for the conformationally dynamic nucleotide-free state of Galphai1. PLoS One. 2012;6(8):e23197. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontson L, et al. Characterization of heterotrimeric nucleotide-depleted Galpha(i)-proteins by Bodipy-FL-GTPgammaS fluorescence anisotropy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 524(2):93–8. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProtConsortium. Reorganizing the protein space at the Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 40(Database issue):D71–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eps N, et al. Structural and dynamical changes in an alpha-subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein along the activation pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(44):16194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607972103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eps N, et al. Interaction of a G protein with an activated receptor opens the interdomain interface in the alpha subunit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(23):9420–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105810108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker JL, et al. Disease-causing mutation in GPR54 reveals the importance of the second intracellular loop for class A G-protein-coupled receptor function. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(45):31068–78. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805251200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MA, et al. The Structure of the G Protein Heterotrimer Giα1β1γ2. Cell. 1995;83(6):1047–58. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90220-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gαiβγ proteins containing either no mutation (WT) or indicated residues mutated were assayed before and after activation with AlF4, in the absence of receptors, and fluorescence shown as percent increase in Trp emission after activation with AlF4. Data are the average of 3 independent experiments (± S.E.M.).

Gαi and Gαs homology (left) (Chung et al. 2011); Rho and β2AR homology (right)(Gregory et al.).