Abstract

Objectives. We examined the association between regular cigarette smoking and new onset of mood and anxiety disorders.

Methods. We used logistic regression analysis to detect associations between regular smoking and new-onset disorders during the 3-year follow-up among 34 653 participants in the longitudinal US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (2001–2005). We used instrumental variable methods to assess the appropriateness of these models.

Results. Regular smoking was associated with an increased risk of new onset of mood and anxiety disorders in multivariable analyses (Fdf = 5,61 = 11.73; P < .001). Participants who smoked a larger number of cigarettes daily displayed a trend toward greater likelihood of new-onset disorders. Age moderated the association of smoking with most new-onset disorders. The association was mostly statistically significant and generally stronger in participants aged 18 to 49 years but was smaller and mostly nonsignificant in older adults.

Conclusions. Our finding of a stronger association between regular cigarette smoking and increased risk of new-onset mood and anxiety disorders among younger adults suggest the need for vigorous antismoking campaigns and policy initiatives targeting this age group.

The relationship between cigarette smoking and pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases is well established.1–4 Indeed, early reports on the association of smoking and lung cancer were the major impetus for public health efforts to curb smoking.5 The publication in 1964 of the surgeon general’s report on smoking and health was associated with a steady decline in smoking—a trend that in the following decades likely contributed to declining rates of lung cancer, especially among men.6–8 The relationship between cigarette smoking and mental disorders, however, remains less well characterized.

Several large community surveys have found increased prevalence of mental disorders among smokers.9–18 Longitudinal studies have shown an increased risk of subsequent mood and anxiety disorders in individuals who smoked cigarettes and suggested that the effects might vary according to gender and age.15,19–21 Although longitudinal studies can establish the temporal order of smoking and subsequent incidence of mental disorders, their findings can be confounded by factors that are not known or that are difficult to measure, such as a common genetic predisposition22–25 or a specific personality diathesis,26,27 and that could explain the observed association of smoking and mental disorders.

Establishing the causal link between smoking and mental disorders conclusively would require experimental evidence, which is generally difficult or impossible to obtain. Exposing research participants to tobacco products in a randomized trial raises ethical issues. Controlled randomized trials of smoking cessation interventions might provide causal evidence. However, nicotine withdrawal is often associated with significant early psychological symptoms that may overshadow mental health benefits of smoking cessation.28 Furthermore, randomized trials often comprise a highly selected group of participants, and their findings may not be generalizable.

Because of these limitations, prospective observational studies of representative population-based samples may provide the best available means to investigate the causal links between smoking and common mood and anxiety disorders. Confidence in causal inferences from such data may be enhanced by the use of statistical methods designed for such inference, such as instrumental variable methods.29–31

In this study, we examined the association between smoking and subsequent development of mood or anxiety disorders in data from the longitudinal National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), a large prospective epidemiological survey of the US population.32–34 We examined the association of regular smoking during at least part of the 3-year follow-up period with new onset of major depressive episodes, dysthymia, manic episodes, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Our hypothesis, derived from previous research,9,10,12,20,35,36 was that regular smoking is associated with an increased risk of new onset of these mood and anxiety disorders. We also assessed the dose–response relationship between the average number of cigarettes smoked and the risk of new-onset disorders and whether the relationship between smoking and new-onset psychopathology varied by sociodemographic characteristics.

METHODS

The design and the sample characteristics of the NESARC have been described elsewhere.32–34 Briefly, the NESARC was a survey of the US general population, including residents of Hawaii and Alaska, sponsored by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. The interviews were completed in face-to-face encounters with the participants. The NESARC sample was weighted to adjust for the unequal probabilities of selection and to provide nationally representative estimates.

NESARC wave 1 (baseline) was fielded between 2001 and 2002 and comprised 43 093 participants aged 18 years and older. Of these, 39 959 were eligible for wave 2 (follow-up) interviews. Ineligible participants were, at the time of the follow-up interview, deceased, deported, mentally or physically impaired, or on active military duty. A total of 34 653 eligible wave 1 participants were successfully followed up in the wave 2 survey between 2004 and 2005. The response rates for wave 1 and eligible wave 2 surveys were 81% and 87%, respectively.32

Assessments

We ascertained smoking status from baseline and follow-up survey questions. Participants at baseline were asked whether they were current smokers, ex-smokers, or lifetime nonsmokers. At follow-up, participants were asked whether they smoked any cigarettes since the baseline interview, and if so, how often. The frequency was rated on an ordinal scale ranging from once a month or less to every day. Participants were also asked how many cigarettes they smoked on the days on which they smoked. Separate items asked about smoking in the past year and the time before the past year but after the baseline interview. The regular smoker groups were defined as those participants who reported smoking every day in both periods. We computed the average number of cigarettes smoked during the whole follow-up period as the average number of cigarettes smoked in the past year plus twice the average number of cigarettes smoked between the baseline interview and past year (a period of 2 years) divided by 3. We defined 4 regular smoker groups by the average number of cigarettes smoked daily: 1 to 9, 10 to 19, 20 to 29 or 30 or more cigarettes per day.

Participants who reported being lifetime nonsmokers or ex-smokers at baseline and who responded negatively at follow-up to the question, “Since your last interview in (MO/YR), did you smoke at least 100 cigarettes?” were identified as nonsmokers and ex-smokers, respectively. Participants who reported being current smokers at the baseline interview but denied having smoked 100 or more cigarettes during the follow-up period were also identified as ex-smokers.

NESARC investigators ascertained mental disorders with the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition version,37 administered at baseline and follow-up. Participants who did not meet the criteria for a lifetime disorder at baseline but met the diagnostic criteria in the period between the baseline and follow-up interviews were rated as new-onset or incident cases.32 We included 8 disorders in our analyses: major depressive episodes, dysthymia, manic episodes, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD was assessed only in the wave 2 interview. However, participants were asked whether the time they first experienced the symptoms was since the baseline interview. Only PTSD episodes that started after the baseline interview were categorized as new-onset PTSD.

We used instrumental variable methods to assess possible endogeneity of smoking in regression models predicting new-onset mental disorders.29–31 Instrumental variables are variables that are associated with the exposure of interest (in this case smoking), but are only associated with the outcome of interest (new-onset mental disorders) through their association with the exposure variable. The instrumental variables we chose for our study were state cigarette taxes and public attitudes toward smoking. Strong evidence exists for an association between these variables and initiation of smoking,38,39 and it is implausible that state cigarette taxes or public attitudes toward smoking would directly affect incidence of mood or anxiety disorders (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, provides a more detailed description of the instrumental variables and results of the analyses for testing the validity of the instruments). We obtained data on state cigarette taxes for 2001 and 2002 collected and published by the Tax Policy Center.40

Our data on attitudes toward smoking were collected as part of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health and aggregated for each state.41 We derived our data on attitudes from the following question that this survey asked of all participants: “How much do people risk harming themselves physically and in other ways when they smoke one or more packs of cigarettes per day?” Participants who responded “great risk” were rated as having a negative attitude toward smoking.

State taxes averaged over 2001 and 2002 ranged from 2.8 cents to $1.31 across states. Prevalence of negative attitudes toward smoking ranged from 64.4% to 72.2%. We linked data on instrumental variables to the NESARC data according to the state of residence of the NESARC participants at baseline.

Analyses

We conducted analyses in 3 stages. First, we explored the possible endogeneity of regular smoking in regression models predicting new onset of mood and anxiety disorders through a series of instrumental variable probit analyses.42 Instrumental variable methods allowed us to assess endogeneity (i.e., an association between smoking and the error terms in the regression models for each outcome as a result of omitted common causes of both smoking and new-onset mental disorders) and to adjust for such endogeneity if present. Each instrumental variable probit regression jointly modeled smoking (as a continuous variable of average number of cigarettes smoked) and the target mental health condition. We used the variables of state-level cigarette taxes and public attitudes toward smoking as instruments in these models.

We assessed endogeneity of smoking in 2 ways: testing the ρ coefficient obtained from the maximum likelihood estimation and the Wald statistics from the 2-step estimation. The ρ coefficient represented the correlation between the error terms of the 2 jointly modeled regressions: the regression of average number of cigarettes smoked on the instrumental variables and the probit regression of new-onset mental disorders on the predicted smoking variable from the first model. A large and statistically significant ρ coefficient and a statistically significant Wald statistic suggest that the estimator for the relationship of exposure and outcome obtained from the naive regression models would not be consistent because of endogeneity of the exposure variable.31 In this case, estimators from instrumental variable probit analyses are more likely to be consistent. A nonsignificant ρ coefficient and Wald statistic would suggest that exposure is not endogenous in the model predicting the outcome and that the results of the naive regression model without instrumental variables are consistent and can be interpreted.

The models adjusted for such potential confounding variables as gender, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education (< 12 years, high school graduate or general equivalency diploma, or any college), marital status (currently married or living as married, widowed, divorced, separated, or never married), physical illness (cardiovascular illnesses, gastrointestinal illnesses, and arthritis), residence (metropolitan central city, other metropolitan, or nonmetropolitan), region (Northeast, Southwest, West, or South). Cardiovascular illnesses comprised hardening of arteries or arteriosclerosis, high blood pressure or hypertension, chest pain or angina pectoris, heart attack or myocardial infarction, and other forms of heart disease. Gastrointestinal illnesses comprised gastritis, stomach ulcer, cirrhosis of the liver, and other liver diseases. The arthritis category had arthritis only. Participants were asked whether they had each condition in the past 12 months and whether the diagnosis was confirmed by a doctor or other health professional.

In the second stage of the analyses, we conducted binary logistic regression analyses in which we assessed the association of smoking with the onset of any mood or anxiety disorders and with new onset of individual disorders. We categorized smoking status into 5 levels: 4 smoker groups and 1 nonsmoker group. We further divided the nonsmoker group into ex-smokers and lifetime nonsmokers. The analyses also adjusted for the same variables as in the first stage. We excluded participants with a lifetime history of each target disorder from the analyses for that disorder. For example, we excluded participants with lifetime history of panic disorder at baseline from the analyses of new-onset panic disorder. The analyses adjusted for other lifetime disorders.

In the third stage of the analyses, we assessed whether the association of smoking with new-onset mental disorders was consistent across groups defined by gender, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, and past history of mental disorders (as a dichotomous variable, any vs none at baseline). To this end, we entered the interaction terms of smoking status with these characteristics 1 at a time into a logistic regression model and tested their association with the new onset of any mood or anxiety disorders. If an interaction term was statistically significant, we conducted further stratified regression analyses for any mood or anxiety disorders at aggregate level and for individual disorders. In the interaction analyses, we adjusted for the same sociodemographic, physical, and mental health variables as in the main effect analyses.

We conducted all analyses with the STATA 12 software43 and adjusted for survey weights, clustering, and stratification of data. We weighted all percentages reported. We defined statistical significance as P < .05.

RESULTS

A total of 33 154 (95.7%) of the 34 653 NESARC participants were classified as regular current smokers, nonsmokers, or ex-smokers; 1009 (2.8%) could not be categorized because they were not regular smokers during the entire follow-up period, and 490 (1.4%) had missing data on some smoking variables and were excluded from the analyses.

Of the 33 154 participants included in the analyses, 18 454 (53.9%) reported being lifetime nonsmokers at baseline and denied smoking cigarettes regularly during the follow-up. Another 8900 (27.9%) reported being ex-smokers or current smokers at baseline, but denied smoking regularly during the follow-up. Finally, 5800 (18.2%) reported smoking regularly (i.e., every day) during the follow-up period. Of these, 1061 (14.8% of smokers) reported smoking 1 to 9 cigarettes per day on average; 1961 (32.3%), 10 to 19 cigarettes; 2040 (38.1%), 20 to 29 cigarettes; and 738 (14.8%), 30 or more cigarettes.

We found significant differences among lifetime nonsmokers, ex-smokers, and current regular smokers in sociodemographic, physical health, and psychiatric characteristics (Table 1). Most notably, regular heavy smokers (≥ 20 cigarettes/day) and ex-smokers were more likely than nonsmokers to be male, and ex-smokers were significantly older than both nonsmokers and current smokers (Table 1). Furthermore, regular smokers, especially those smoking a larger number of cigarettes on average, were consistently 2 to 3 times as likely as nonsmokers to meet the lifetime criteria for mood, anxiety, and nonnicotine substance use disorders. Smokers were also more likely to experience new onset of mood and anxiety disorders during the follow-up (Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Participants by Smoking Status: US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2005

| Smokers, by Number of Cigarettes/Day |

||||||

| Characteristics | Nonsmokers (n = 18 454), % | Ex-smokers (n = 8900), % | 1–9 (n = 1061), % | 10–19 (n = 1961), % | 20–29 (n = 2040), % | ≥ 30 (n = 738), % |

| Women | 60.5 | 40.0*** | 57.4 | 56.2** | 41.8*** | 34.0*** |

| Age, y | ||||||

| 18–29 | 24.8 | 10.7*** | 35.7*** | 30.1*** | 21.7* | 13.5*** |

| 30–39 | 22.2 | 14.7*** | 23.5 | 23.0 | 21.6 | 18.3* |

| 40–49 | 20.0 | 19.8 | 20.2 | 22.4 | 25.2*** | 34.9*** |

| 50–64 | 18.1 | 28.1*** | 13.9** | 17.6 | 24.4*** | 28.8*** |

| ≥ 65 | 14.8 | 26.8*** | 6.7*** | 7.0*** | 7.1*** | 4.6*** |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 64.7 | 80.0*** | 49.5*** | 72.6*** | 84.3*** | 89.2*** |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12.8 | 7.7*** | 22.6*** | 12.6 | 7.2*** | 3.0*** |

| Hispanic | 14.7 | 7.8*** | 18.4* | 7.7*** | 3.9*** | 2.8*** |

| Other | 7.7 | 4.4*** | 9.5 | 7.0 | 4.6** | 5.0* |

| Household income, $ | ||||||

| < 20 000 | 20.0 | 17.5*** | 25.0** | 23.5*** | 24.3*** | 24.7* |

| 20 000–34 999 | 18.4 | 19.5 | 23.5** | 23.9*** | 23.8*** | 19.1 |

| 35 000–59 999 | 25.1 | 27.5** | 27.3 | 27.6 | 26.5 | 33.8*** |

| ≥ 60 000 | 36.2 | 35.5 | 24.2*** | 25.1*** | 25.5*** | 22.3*** |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or living as married | 62.8 | 71.4*** | 46.1*** | 52.5*** | 58.0*** | 58.2* |

| Widowed, divorced, or separated | 14.2 | 17.9*** | 17.5** | 21.0*** | 21.6*** | 27.0*** |

| Never married | 23.1 | 10.7*** | 36.4*** | 26.6** | 20.4* | 14.9*** |

| Education | ||||||

| < 12 y | 12.8 | 14.8** | 19.4*** | 18.4*** | 20.2*** | 22.8*** |

| High school graduate/GED | 26.2 | 28.7** | 29.9* | 33.7*** | 40.2*** | 41.3*** |

| Any college | 60.9 | 56.5*** | 50.7*** | 48.0*** | 39.7*** | 36.0*** |

| Urbanicity | ||||||

| Metropolitan, central city | 30.9 | 25.8*** | 37.3** | 29.7 | 24.4*** | 18.1*** |

| Other metropolitan | 50.9 | 52.1 | 46.5* | 46.2** | 49.3 | 49.8 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 18.2 | 22.1*** | 16.2 | 24.1*** | 26.3*** | 32.1*** |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 19.5 | 20.6 | 21.6 | 19.8 | 17.2 | 17.2 |

| Midwest | 21.7 | 23.5* | 19.7 | 26.5*** | 29.7*** | 29.3** |

| South | 34.8 | 34.6 | 35.6 | 34.9 | 37.8 | 43.2** |

| West | 24.1 | 21.2* | 23.1 | 18.8** | 15.4*** | 10.4*** |

| Lifetime mental disorders at baseline | ||||||

| Major depression | 13.7 | 15.9** | 16.1 | 22.7*** | 19.9*** | 21.3*** |

| Dysthymia | 3.5 | 4.8*** | 4.2 | 7.9*** | 8.9*** | 13.9*** |

| Bipolar disorder (manic episode) | 2.6 | 3.0 | 4.2* | 6.8*** | 7.5*** | 9.4*** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.7 | 4.4* | 4.2 | 7.4*** | 6.7*** | 12.6*** |

| Panic disorder | 3.9 | 5.7*** | 6.5** | 10.4*** | 9.4*** | 12.3*** |

| Social phobia | 4.6 | 5.3* | 2.9* | 6.2** | 6.6** | 8.9*** |

| Specific phobias | 8.2 | 9.8** | 9.1 | 12.7*** | 13.6*** | 15.2*** |

| Lifetime substance disorders at baseline | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | 11.3 | 27.2*** | 19.0*** | 21.6*** | 25.0*** | 27.0*** |

| Alcohol dependence | 6.4 | 14.6*** | 19.3*** | 22.4*** | 25.6*** | 29.1*** |

| Nonalcohol drug abusea | 3.2 | 9.3*** | 12.7*** | 15.5*** | 17.7*** | 15.9*** |

| Nonalcohol drug dependencea | 0.6 | 2.6*** | 4.5*** | 6.0*** | 6.4*** | 7.1*** |

| Physical illness in the past year | ||||||

| Cardiovascularb | 18.9 | 30.1*** | 14.7** | 15.3** | 18.1 | 23.0* |

| Gastrointestinalc | 4.8 | 7.7*** | 5.7 | 7.2*** | 10.3*** | 8.8*** |

| Arthritis | 14.6 | 23.7*** | 11.3* | 15.0 | 17.1* | 23.0*** |

| New-onset mental disorders | ||||||

| Any mood or anxiety disorder | 11.1 | 10.5 | 17.7*** | 15.8*** | 17.5*** | 18.6*** |

| Major depressive episodes | 4.6 | 3.7** | 6.4* | 4.8 | 5.6 | 6.9* |

| Dysthymia | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.5* | 1.8*** | 2.0*** | 1.8** |

| Manic episodes | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 2.4** | 3.3*** | 4.1*** |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 2.9 | 2.7 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 5.0*** | 4.9** |

| Panic disorder | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.9** | 2.9*** | 3.3*** | 3.0** |

| Social anxiety disorder | 1.1 | 1.3 | 2.2** | 2.7*** | 2.9*** | 2.8** |

| Specific phobias | 2.1 | 1.7 | 4.0** | 3.5** | 3.2* | 3.9** |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.5* | 2.2 | 2.9*** | 1.6 |

Note. GED = general equivalency diploma.

Comprises cannabis, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, and stimulants.

Comprises self-reported history of hardening of arteries or arteriosclerosis, high blood pressure or hypertension, chest pain or angina pectoris, heart attack or myocardial infarction, or other form of heart disease as confirmed by a doctor or other health professional in the past 12 months.

Comprises self-reported history of gastritis, stomach ulcer, cirrhosis of the liver or other liver disease as confirmed by a doctor or other health professional in the past 12 months.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001. Each group is compared with the group of lifetime nonsmokers.

The instrumental variables were strongly and significantly associated with individual-level smoking behavior (joint Fdf = 2,64 = 91.68; P < .001). A 1% higher rating of negative attitudes toward smoking at the state level was associated with 7% lower odds of being a regular smoker (odds ratio [OR] = 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.92, 0.94; P < .001). Also, a $1 higher state cigarette tax was associated with 31% lower odds of being a regular smoker (OR = 0.69; 95% CI = 0.60, 0.80; P < .001). However, neither the ρ coefficient nor the Wald test from the 2-step estimation in the instrumental variable probit models reached a statistically significant level (Appendix A, available as an online supplement), suggesting that the regression coefficients from the naive models were consistent and could be interpreted.

These multivariable logistic regression analyses adjusting for gender, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, physical illness, residence, region, and lifetime history of mental disorders, alcohol disorders, and nonalcohol drug disorders revealed a statistically significant association between regular smoking and new onset of any mood or anxiety disorder as well as specific disorders, except for generalized anxiety disorder (Table 2). Furthermore, these analyses revealed significant trends across smoking status: lifetime nonsmokers typically had lower odds of new-onset disorders than other groups, and heavy smokers had higher odds. However, this pattern was not consistent across all disorders and was not apparent in the case of PTSD (Table 2).

TABLE 2—

Association of Smoking With New Onset of Mental Disorders at Follow-Up: US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2005

| Disorders | AORa (95% CI) | Overall Test, Fdf = 5,61 | Test of Trend, Fdf = 1,65 |

| Any mood or anxiety disorder | 11.73*** | 29.88*** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.18** (1.06, 1.31) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.49** (1.18, 1.86) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.30** (1.11, 1.53) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.64*** (1.41, 1.90) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.84*** (1.43, 2.38) | ||

| New onset of major depressive episodes | 2.86* | 11.62** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.05 (0.88, 1.24) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.31 (0.91, 1.90) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.11 (0.83, 1.47) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.40* (1.08, 1.81) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.93** (1.27, 2.95) | ||

| New onset of dysthymia | 9.05*** | 27.53*** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.08 (0.69, 1.68) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.95 (0.95, 4.03) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 2.87*** (1.67, 4.95) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 4.26*** (2.45, 7.40) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 4.31*** (2.00, 9.32) | ||

| New onset of manic episodes | 5.95*** | 24.46*** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.07 (0.75, 1.50) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.07 (0.65, 1.76) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.44 (0.96, 2.15) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.28*** (1.52, 3.41) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.83** (1.60, 5.02) | ||

| New onset of generalized anxiety disorder | 1.77 | 5.55* | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.05 (0.86, 1.30) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.37 (0.84, 2.22) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.05 (0.78, 1.41) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.46* (1.08, 1.97) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.55 (1.00, 2.40) | ||

| New onset of panic disorder | 5.95*** | 13.52*** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.56** (1.16, 2.10) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 2.03** (1.21, 3.41) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 2.04*** (1.40, 2.97) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.59*** (1.69, 3.95) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.64** (1.45, 4.82) | ||

| New onset of social anxiety disorder | 3.85** | 7.54** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.25 (0.90, 1.72) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.51 (0.91, 2.51) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.85** (1.19, 2.89) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.11*** (1.42, 3.11) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.95* (1.03, 3.72) | ||

| New onset of specific phobias | 5.96*** | 17.62*** | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.09 (0.84, 1.42) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.83* (1.12, 3.00) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.72** (1.23, 2.40) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.79** (1.26, 2.55) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.35** (1.45, 3.80) | ||

| New onset of posttraumatic stress disorder | 3.03* | 2.76 | |

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | ||

| Ex-smokers | 1.37* (1.05, 1.80) | ||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.43 (0.85, 2.39) | ||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.33 (0.86, 2.06) | ||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.17** (1.45, 3.25) | ||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.35 (0.71, 2.60) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Analyses adjusted for baseline variables of gender, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, physical illness (cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, arthritis), residence (metropolitan central city, other metropolitan, nonmetropolitan), region (Northeast, Southwest, West, South), lifetime history of other mental disorders, alcohol disorders, and nonalcohol drug disorders.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

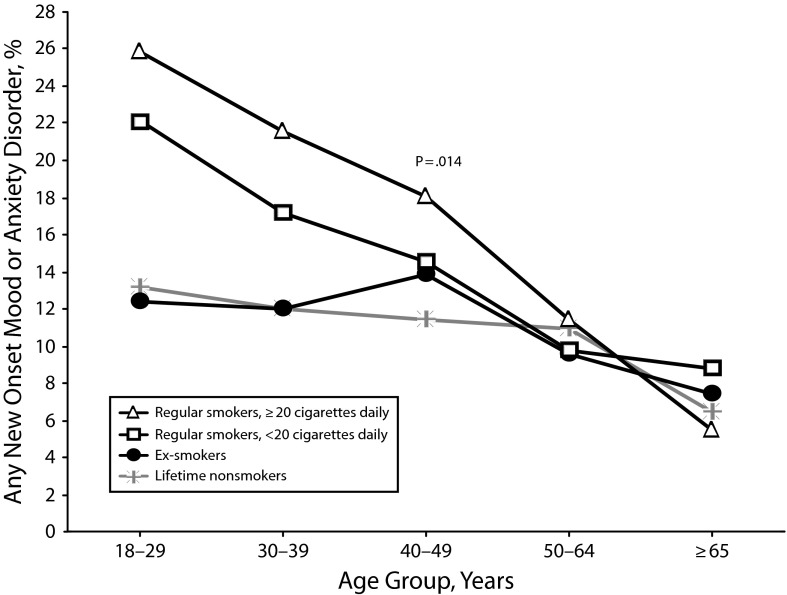

In our assessment of whether the association of smoking and new-onset mental disorders was consistent across sociodemographic groups, only the interaction term for age with smoking status was statistically significant (Fdf = 20,46 = 2.19; P = .014). We detected an association of smoking with any new-onset mood or anxiety disorders only in the younger age groups (18–29 years, Fdf = 5,61 = 8.98; P < .001; 30–39 years, Fdf = 5, 61 = 4.17; P = .003; 40–49 years, Fdf = 5,61 = 4.75; P = .001). In participants aged 50 years or older, the association of smoking with new onset of disorders was not statistically significant (50–64 years, Fdf = 5,61 = 0.53; P = .750; ≥ 65 years, Fdf = 5,61 = 1.51; P = .200; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1—

New onset of any mood or anxiety disorders according to age group and smoking status: US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2005.

Note. P value is derived from statistical testing of the interaction of age group with smoking status.

We found a similar pattern for most individual new-onset disorders when we tested their association with smoking within age strata separately for each disorder. Among participants who were younger than 50 years, smoking was associated at a statistically significant level with new onset of major depressive episodes, dysthymia, manic episodes, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobias, social phobia, and PTSD (Table 3). Among participants aged 50 years or older, smoking was only associated with new onset of manic episodes (Table 3). In addition, the test for trend in the association of smoking and dysthymia was statistically significant among participants aged 50 years or older, although the overall test was not statistically significant (Table 3).

TABLE 3—

Association of Smoking With New Onset of Mental Disorders at Follow-Up by Age: US National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions, 2001–2005

| Participants Aged < 50 Years | Participants Aged ≥ 50 Years | |||||

| New-Onset Disorders | AORa (95% CI) | Overall Test, Fdf = 5,61 | Test of Trend, Fdf = 1,65 | AORa (95% CI) | Overall Test, Fdf = 5,61 | Test of Trend, Fdf = 1,65 |

| Any mood or anxiety disorder | 12.02*** | 33.33*** | 0.72 | 1.26 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.16* (1.00, 1.35) | 1.12 (0.95, 1.32) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.64*** (1.27, 2.11) | 0.93 (0.55, 1.58) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.42** (1.17, 1.72) | 1.03 (0.73, 1.46) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.84*** (1.53, 2.22) | 1.21 (0.89, 1.65) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.14*** (1.58, 2.88) | 1.28 (0.75, 2.19) | ||||

| Major depressive episodes | 4.15** | 16.40*** | 0.73 | 0.43 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 0.92 (0.73, 1.15) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.60) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.38 (0.93, 2.06) | 0.93 (0.37, 2.32) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.21 (0.87, 1.69) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.49) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.61** (1.19, 2.17) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.62) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.18** (1.37, 3.48) | 1.6 (0.68, 3.77) | ||||

| Dysthymia | 7.05*** | 19.23*** | 1.87 | 8.28** | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 0.93 (0.51, 1.70) | 1.18 (0.58, 2.40) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.86 (0.81, 4.28) | 1.91 (0.57, 6.39) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 2.82** (1.53, 5.21) | 2.72 (0.97, 7.66) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 4.46*** (2.23, 8.92) | 2.73 (1.00, 7.48) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 4.27** (1.64, 11.14) | 4.97* (1.38, 17.88) | ||||

| Manic episodes | 4.86*** | 21.35*** | 3.13* | 5.09* | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.03 (0.65, 1.62) | 1.01 (0.61, 1.69) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 0.92 (0.52, 1.65) | 2.53* (1.00, 6.37) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.23 (0.78, 1.93) | 3.09* (1.33, 7.21) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.24** (1.37, 3.66) | 2.58* (1.24, 5.36) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.83** (1.53, 5.23) | 3.28 (0.74, 14.51) | ||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.81** | 10.56** | 0.83 | 0.13 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.17 (0.90, 1.52) | 0.86 (0.61, 1.20) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.65 (0.98, 2.77) | 0.63 (0.18, 2.21) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.21 (0.86, 1.70) | 0.72 (0.36, 1.43) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 1.93*** (1.41, 2.66) | 0.59 (0.32, 1.09) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.95** (1.19, 3.19) | 1.03 (0.42, 2.51) | ||||

| Panic disorder | 5.97*** | 12.46*** | 0.77 | 1.01 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.56* (1.08, 2.27) | 1.25 (0.76, 2.06) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 2.24** (1.28, 3.93) | 1.16 (0.37, 3.66) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 2.38*** (1.54, 3.67) | 0.85 (0.30, 2.40) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 3.08*** (1.93, 4.92) | 1.02 (0.41, 2.51) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.86** (1.39, 5.88) | 2.10 (0.74, 5.89) | ||||

| Social anxiety disorder | 3.65** | 8.43** | 2.28 | 0.62 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.64** (1.20, 2.25) | 0.77 (0.44, 1.35) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.61 (0.92, 2.83) | 1.35 (0.56, 3.26) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.82* (1.10, 3.02) | 2.1 (0.74, 5.94) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.11** (1.34, 3.30) | 1.96 (0.93, 4.09) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 2.64** (1.34, 5.20) | 0.27 (0.05, 1.35) | ||||

| Specific phobias | 7.11*** | 19.85*** | 0.3 | 0.69 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.20 (0.84, 1.73) | 0.87 (0.60, 1.24) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 2.08** (1.22, 3.54) | 1.04 (0.37, 2.92) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 2.04*** (1.40, 2.97) | 1.02 (0.49, 2.12) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.14** (1.41, 3.25) | 1.19 (0.59, 2.44) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 3.04*** (1.75, 5.28) | 1.3 (0.49, 3.45) | ||||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 2.58* | 1.87 | 0.67 | 0.4 | ||

| Nonsmokers (Ref) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Ex-smokers | 1.18 (0.81, 1.71) | 1.46 (0.48, 6.73) | ||||

| Smokers, 1–9 cigarettes/d | 1.43 (0.81, 2.51) | 1.47 (0.41, 5.33) | ||||

| Smokers, 10–19 cigarettes/d | 1.35 (0.81, 2.25) | 1.33 (0.53, 3.33) | ||||

| Smokers, 20–29 cigarettes/d | 2.35** (1.45, 3.78) | 1.24 (0.54, 2.81) | ||||

| Smokers, ≥ 30 cigarettes/d | 1.14 (0.54, 2.43) | 1.79 (0.48, 6.73) | ||||

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Analyses adjusted for baseline variables of gender, age, race/ethnicity, household income, education, marital status, physical illness (cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, arthritis), residence (metropolitan central city, other metropolitan, nonmetropolitan), region (Northeast, Southwest, West, South), lifetime history of other mental disorders, alcohol disorders, and nonalcohol drug disorders.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

These findings corresponded with an overall decreasing rate of new-onset mood or anxiety disorders associated with increasing age. A total of 3181 (14.2%) of the 21 164 participants aged 18 to 49 years experienced new onset of mood or anxiety disorders; by contrast, only 1268 (8.9%) of 13 489 participants aged 50 years or older reported a new mood or anxiety disorder (OR = 1.69; 95% CI = 1.56, 184; P < .001). We observed a similar pattern for each individual mood and anxiety disorder, with ORs ranging from 1.51 for dysthymia to 2.42 for manic episodes (all, P < 0.01; data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Despite declining rates, smoking remains prevalent in the United States and other countries.44–48 Almost 1 out of every 5 NESARC participants reported smoking cigarettes regularly at some point during the 3-year follow-up. Thus, smoking remains a major public health problem. We found a clear association between regular smoking and new-onset mood and anxiety disorders. This finding is consistent with results from other longitudinal studies.15,19–21 Our use of instrumental variable models and longitudinal design further supports a causal link. Instrumental variable analyses with state cigarette taxes and public attitudes as instruments did not detect significant endogeneity for smoking in these models, suggesting that the coefficients from naive regression models could be interpreted as consistent estimators of the effects of smoking on new-onset mental disorders.

We also found a significant moderating effect of age on the relationship between smoking and new onset of mood and anxiety disorders. The association was significant in participants aged 18 to 49 years but mainly nonsignificant in participants aged 50 years or older. The reasons for the moderating effect of age on the association of smoking with new-onset mood and anxiety disorders remain unclear. One possible explanation for this moderating effect is the existence of a risk window, during which individuals are especially vulnerable to exposures.49–51 This interpretation is supported by findings of decreased incidence of mood and anxiety disorders in older adults in our study and others52–54 and findings of strong associations between smoking and new onset of mood and anxiety disorders in adolescents.15,21 Nevertheless, this explanation remains speculative. Future research should explore this and other possible explanations, such as cohort effects and greater mortality among smokers with mood and anxiety disorders.

Previous research provides few clues to possible biological mechanisms linking smoking and mental illness. Agonists of nicotinic cholinergic receptors (including nicotine itself) presumably improve cognition and mood.55–56 Indeed, these effects of nicotine are the basis for the self-medication hypothesis regarding the association of smoking with mental disorders.14,57 However, it has also been hypothesized that chronic administration of cholinergic agents may lead to indirect inhibition of the nicotinic receptors (functional antagonism) and hence contribute to increased prevalence of depression.56 Furthermore, the mechanisms linking smoking with mental illness may vary across individuals according to their genetic makeup.58 The mechanisms may also vary by type of mental disorder.59 In view of the findings regarding the moderating effect of age, exploring the potential impact of biological factors such as hormonal changes associated with age may help to elucidate the link between smoking and mental illness.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in the context of our study’s limitations. The onset of smoking might have preceded the onset of mental disorders by many years. The time lag between the onset of regular smoking and the onset of new mental disorders may have important implications. For example, participants who have just started smoking may be more vulnerable than those who have smoked regularly for many years. A more detailed assessment of the effect of smoking on onset of mental disorders would require studying a large cohort of participants recruited at an early age and assessed at multiple time points across the life span.

Smoking history and mental disorder symptoms were both assessed by self-report and were thus prone to recall bias. Past research has shown that reports of lifetime mental disorders are especially prone to such biases.60

In the context of these limitations, the data provide supporting evidence from a large, longitudinal, population-based survey on the link between regular smoking and the onset of mental disorders. These findings add to a growing literature on the mental health consequences of smoking and further suggest that these consequences might be limited to the younger age group.

Conclusions

Past antismoking information and policy initiatives were mostly motivated by findings of increased risk of lung cancer and cardiovascular disease and higher rates of mortality among smokers.61 Our findings and results from other studies of the mental health consequences of smoking for youths15,21 point to an increased, smoking-attributable burden of mental health morbidity and impairment in functioning. It is estimated that by 2030, major depression will be the number one contributor to the burden of disease worldwide.62 The finding of links between smoking and major depression as well as other common and disabling mental disorders highlights the urgency of antismoking campaigns and policy initiatives, especially those targeting adolescents and young adults.

Our finding of a strong association between state-level public attitudes and smoking behavior highlights the role of public health education campaigns and media in shaping behaviors. The observed association with state cigarette taxes highlights the role of policy initiatives and financial disincentives in discouraging smoking behavior. Public health interventions involving education and financial disincentives may be combined with individual-level smoking cessation interventions for youths63–66 to effectively reduce smoking behavior among this vulnerable population group.

Acknowledgments

Data analyses and preparation of this paper were supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA030460) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA016346).

Note. Ramin Mojtabai previously received research funding and consultant fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Lundbeck pharmaceuticals.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was required because the study used de-identified public access data.

References

- 1.Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung. BMJ. 1950;2(4682):739–748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sasco AJ, Secretan MB, Straif K. Tobacco smoking and cancer: a brief review of recent epidemiological evidence. Lung Cancer. 2004;45(suppl 2):S3–S9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilhelmsson C, Elmfeldt D, Vedin JA, Tibblin G, Wilhelmsen L. Smoking and myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1975;305(7904):415–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt AM. The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product That Defined America. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingo PA, Ries LA, Giovino GAet al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1996, with a special section on lung cancer and tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(8):675–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jemal A, Thun MJ, Ries LAet al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2005, featuring trends in lung cancer, tobacco use, and tobacco control. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(23):1672–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Surgeon General’s Advisory Committee on Smoking and Health Smoking and Health Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington, DC: Public Health Service; 1964 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mykletun A, Overland S, Aar LE, Liab HM, Stewart R. Smoking in relation to anxiety and depression: evidence from a large population survey: the HUNT study. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(2):77–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Borges Get al. Smoking and suicidal behaviors in the National Comorbidity Survey: replication. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195(5):369–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zvolensky MJ, Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner EW, McLeish AC. Smoking and panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia: a review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(6):761–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard S, Adler L, Benhammou Ket al. Smoking and mental illness. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70(4):561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonntag H, Wittchen HU, Hofler M, Kessler RC, Stein MB. Are social fears and DSM-IV social anxiety disorder associated with smoking and nicotine dependence in adolescents and young adults? Eur Psychiatry. 2000;15(1):67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. JAMA. 2000;284(18):2348–2351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breslau N, Klein DF. Smoking and panic attacks: an epidemiologic investigation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1141–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslau N. Psychiatric comorbidity of smoking and nicotine dependence. Behav Genet. 1995;25(2):95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dube SR, Caraballo RS, Dhingra SSet al. The relationship between smoking status and serious psychological distress: findings from the 2007 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:68–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klungsøyr O, Nygård JF, Sørensen T, Sandanger I. Cigarette smoking and incidence of first depressive episode: an 11-year, population-based follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(5):421–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korhonen T, Broms U, Varjonen Jet al. Smoking behaviour as a predictor of depression among Finnish men and women: a prospective cohort study of adult twins. Psychol Med. 2007;37(5):705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steuber TL, Danner F. Adolescent smoking and depression: which comes first? Addict Behav. 2006;31(1):133–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishikawa H, Ohtsuki T, Ishiguro Het al. Association between serotonin transporter gene polymorphism and smoking among Japanese males. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(9):831–833 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schinka JA, Busch RM, Robichaux-Keene N. A meta-analysis of the association between the serotonin transporter gene polymorphism (5-HTTLPR) and trait anxiety. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(2):197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kendler KS, Neale MC, MacLean CJ, Heath AC, Eaves LJ, Kessler RC. Smoking and major depression: a causal analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(1):36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pergadia ML, Glowinski AL, Wray NRet al. A 3p26-3p25 genetic linkage finding for DSM-IV major depression in heavy smoking families. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(8):848–852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eysenck HJ, Tarrant M, Woolf M, England L. Smoking and personality. Br Med J. 1960;1(5184):1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terracciano A, Costa PT., Jr Smoking and the Five-Factor Model of personality. Addiction. 2004;99(4):472–481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Breslau N, Kilbey MM, Andreski P. Nicotine withdrawal symptoms and psychiatric disorders: findings from an epidemiologic study of young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(4):464–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wooldridge JM. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. 4th ed. Mason, OH: South Western, Cengage Learning; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao Y, Duan N, Fox SA. Is some provider advice on smoking cessation better than no advice? An instrumental variable analysis of the 2001 National Health Interview Survey. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(6):2114–2135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharya J, Goldman D, McCaffrey D. Estimating probit models with self-selected treatments. Stat Med. 2006;25(3):389–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Chou SPet al. Sociodemographic and psychopathologic predictors of first incidence of DSM-IV substance use, mood and anxiety disorders: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(11):1051–1066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DAet al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hasin DS, Goodwin RD, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(10):1097–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Psychiatric disorders and stages of smoking. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Daily smoking and the subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):323–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Corty E, Olshavsky RW. Predicting the onset of cigarette smoking in adolescents: a longitudinal study. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1984;14(3):224–243 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meier KJ, Licari MJ. The effect of cigarette taxes on cigarette consumption, 1955 through 1994. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1126–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tax Policy Center. State Cigarette rates 2001–2011. 2011. Available at: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=433. Accessed November 8, 2012.

- 41.Office of Applied Studies Results From the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Summary of National Findings. Vol 1 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Newey WK. Efficient estimation of limited dependent variable models with endogenous explanatory variables. J Econom. 1987;36(3):231–250 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stata 12 [computer program] College Station, TX: Stata Corp LP; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. BMJ. 2000;321(7257):323–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin RD, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Changes in cigarette use and nicotine dependence in the United States: evidence from the 2001–2002 wave of the national epidemiologic survey of alcoholism and related conditions. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1471–1477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pierce JP, Fiore MC, Novotny TE, Hatziandreu EJ, Davis RM. Trends in cigarette smoking in the United States. JAMA. 1989;261(1):56–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Warning: a hard habit to break [editorial]. Lancet. 2011;378(9787):200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mullin S. Global anti-smoking campaigns urgently needed. Lancet. 2011;378(9795):970–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murgatroyd C, Wu Y, Bockmuhl Y, Spengler D. Genes learn from stress: how infantile trauma programs us for depression. Epigenetics. 2010;5(3):194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soares CN. Depression during the menopausal transition: window of vulnerability or continuum of risk? Menopause. 2008;15(2):207–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soares CN, Maki PM. Menopausal transition, mood, and cognition: an integrated view to close the gaps. Menopause. 2010;17(4):812–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Major depression in community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: prevalence and 2- and 4-year follow-up symptoms. Psychol Med. 2004;34(4):623–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Castriotta N, Lenze EJ, Stanley MA, Craske MG. Anxiety disorders in older adults: a comprehensive review. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(2):190–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eaton WW, Kramer M, Anthony JC, Dryman A, Shapiro S, Locke BZ. The incidence of specific DIS/DSM-III mental disorders: data from the NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79(2):163–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mihailescu S, Drucker-Colin R. Nicotine, brain nicotinic receptors, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Arch Med Res. 2000;31(2):131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dome P, Lazary J, Kalapos MP, Rihmer Z. Smoking, nicotine and neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(3):295–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Glass RM. Blue mood, blackened lungs. Depression and smoking JAMA. 1990;264(12):1583–1584 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lerman C, Caporaso N, Main Det al. Depression and self-medication with nicotine: the modifying influence of the dopamine D4 receptor gene. Health Psychol. 1998;17(1):56–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goodwin RD, Zvolensky MJ, Keyes KM. Nicotine dependence and mental disorders among adults in the USA: evaluating the role of the mode of administration. Psychol Med. 2008;38(9):1277–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor Aet al. How common are common mental disorders? Evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychol Med. 2010;40(6):899–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mathers C, Fat DM, Boerma JT. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Lewis AL, Klintworth EM, Upadhyaya HP. Varenicline versus bupropion XL for smoking cessation in older adolescents: a randomized, double-blind pilot trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(2):234–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Markham WA, Bridle C, Grimshaw G, Stanton A, Aveyard P. Trial protocol and preliminary results for a cluster randomised trial of behavioural support versus brief advice for smoking cessation in adolescents. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karpinski JP, Timpe EM, Lubsch L. Smoking cessation treatment for adolescents. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2010;15(4):249–263 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schepis TS, Rao U. Smoking cessation for adolescents: a review of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments. Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2008;1(2):142–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]