Abstract

Background

The National Institutes of Health–funded Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) have increasingly focused on community-engaged research and funded investigators for community-based participatory research (CBPR). However, because CBPR is a collaborative process focused on community-identified research topics, the Harvard CTSA and its Community Advisory Board (CERAB) funded community partners through a CBPR initiative.

Objectives

We describe lessons learned from this seed grants initiative designed to stimulate community–academic CBPR partnerships.

Methods

The CBPR program of the Harvard CTSA and the CERAB developed this initiative and each round incorporated participant and advisory feedback toward program improvement.

Lessons Learned

Although this initiative facilitated relevant and innovative research, challenges included variable community research readiness, insufficient project time, and difficulties identifying investigators for new partnerships.

Conclusion

Seed grants can foster innovative CBPR projects. Similar initiatives should consider preliminary assessments of community research readiness as well as strategies for meaningful academic researcher engagement.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, clinical and translational research, capacity building, seed grants, community–academic partnerships

Involving communities in research to advance community health is gaining attention as a way to improve the relevance and adoption of translational research. One approach is community-based participatory research (CBPR), a collaborative process focused on community-identified research topics.1 Proponents believe that CBPR can enhance the impact of translational science and lead to the sustainable adoption of evidence-based practices for social change.2 Despite the focus on community-initiated topics, CBPR funding is generally for academic investigator-initiated grants with community partners as co-investigators or subcontractors. We describe lessons from an initiative funding community-inspired CBPR projects.

BARRIERS AND FACILITATORS TO STIMULATING AND SUSTAINING CBPR

Factors that facilitate successful CBPR projects include a strong existing partnership,2 organizational commitment to this partnership,3 efforts to sustain partner trust,4 and the presence of organizational structures (e.g., staff) to support CBPR. However, communities still face exploitative and inequitable research relationships5 resulting from differential experience/capacity and resources.5–7

These challenges prompt questions about whether partnership equity is achievable.8 To address these barriers, we funded community-initiated CBPR projects to address unequal power dynamics and facilitate a community-driven research agenda. What follows is a discussion of lessons learned.

PROJECT BACKGROUND AND PARTNERS

In 2008, the National Institutes of Health awarded Harvard University a CTSA, also known as Harvard Catalyst. The overall goal of the CTSA is to remove the chasm between clinical and basic research by addressing the lag between the development of laboratory clinical innovation and its translation into practice, also known as translational research.9, 10 The Harvard Catalyst is 1 of 55 medical institutions funded through the CTSA. Harvard Catalyst facilitates cross-Harvard collaboration to improve human health and nurtures community–academic partnerships to increase community relevant research.

A key component of Harvard Catalyst is the Community Engagement (CE) program, which addresses the lack of meaningful public participation in clinical research.9 The CE program incorporates multiple foci including a CBPR program led by The Institute for Community Health in collaboration with the Center for Community Based Research at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute and the Department of Society, Human Development, and Health at the Harvard School of Public Health. A community advisory board(CERAB), described later, provides guidance to the program.

Harvard Catalyst also sponsors an annual pilot grant initiative for Harvard investigators to fund collaborative translational projects with a demonstrable impact on human health. Although this mechanism was open to CBPR projects, the number and quality of CBPR pilot proposals was limited, with only 1 CBPR project funded out of 61 funded grants in the initial pilot round. In response, the CBPR program and members of the CERAB designed and implemented a “seed” funding initiative (seed grants) to stimulate partnership and CBPR project development, and facilitate pilot grant submissions. The CERAB is composed of 8 community leaders representing community physicians, coalitions, and government/public health agencies, all with existing partnerships with Harvard CBPR researchers. The CERAB, originally convened to bring a community voice to the CE discourse, now meets regularly with Harvard Catalyst CE leaders and provides guidance to the CBPR program.

Overall, there is scant literature on the barriers and facilitators of funding community-initiated CBPR projects. Several attempts to provide funds for CBPR to communities have been limited to certain topic areas (e.g., geriatrics and cancer).11, 12. Although authors note benefits of this approach including community capacity building, they have acknowledged challenges such as maintenance costs and time needed to foster CBPR.11, 12 The purpose of our initiative was to stimulate community– academic relationships necessary for improved translational research. We address a key barrier to translational research, namely, unequal power dynamics, by directing funding to community partners. Additionally, our initiative encompasses a range of content areas and populations, thus broadening the potential impact on population health. The overall goals are to (1) engage communities and empower them to select a research problem area for study, (2) facilitate community understanding of the value of evidence and how to incorporate it into programs, (3) facilitate partnership with an academic and/or gather preliminary evidence in this area, and (4) facilitate data application to ultimately address the community-identified problem.

Finally, the development and implementation of this initiative represents a participatory process. We have continually incorporated feedback from CERAB members and participants. The lessons learned may be useful to others considering similar initiatives.

METHODS

Development and Implementation of the Seed Grant Initiative

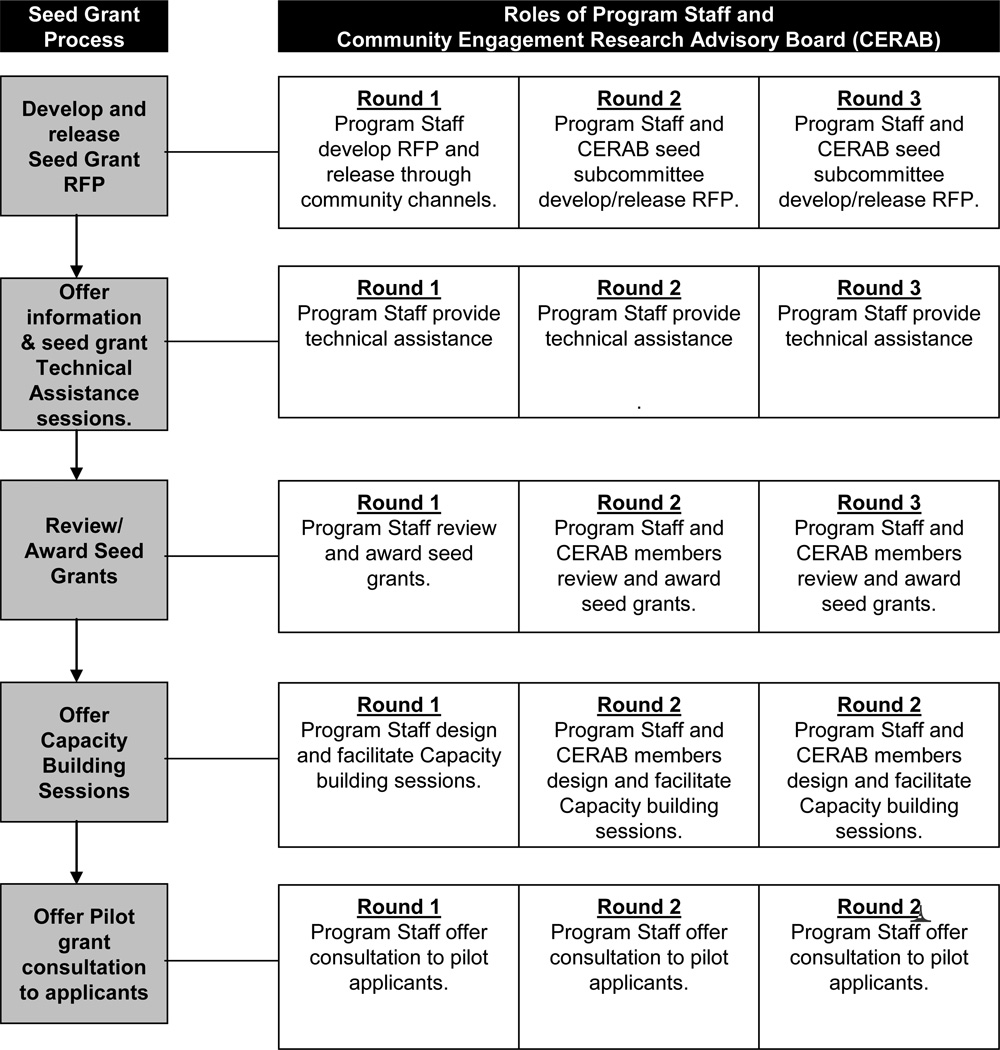

The seed grant initiative was conceptualized by the CBPR program staff however program participants and CERAB members provide ongoing feedback (Figure 1). Funding is available to support activities related to relationship building, research question generation, preliminary data collection, and analysis.

Figure 1.

Description of the Seed Grant Initiative and the Role of Program Staff and Community Engagement Advisory Board Members

To date, we have released three rounds of seed grant requests for proposals (RFP). Each round was modified based on feedback from a previous round. The round 1 RFP (December 2008) was for 4 months and offered $5,000 grants. Round 2 (September 2009) was also for 4 months but offered partnership (up to $2,000) or project development (up to $5,000) grants. Finally, the round 3 RFP (May 2010) was for 8 months, and offered partnership (up to $4,000) or project development grants (up to $8,000). Applications were accepted via e-mail, mail, or fax. Although small, the money was intended to fund community– academic partnerships across a range of projects and prepare communities to submit a larger pilot grant. In response to feedback, grant amounts increased slightly over time.

Grantees were restricted to community partners who were encouraged to work with researchers. Existing partnerships were not required. Eligible applicants were community-based organizations or coalitions of any size with a nonprofit, 501(c) (3) tax-exempt status from Massachusetts. The organizations/groups that were funded ranged from larger local health departments to smaller volunteer agencies (Table 1). Although smaller agencies might not have the reach of larger coalitions, they were often the most likely to impact vulnerable populations and the least likely to have financial support to build evidence into their programs and practice. Round 3 grantees in particular covered a broad geographic range.

Table 1.

Descriptions of Funded Seed Grant Projects

| Grant Typea |

Title | Project Description | Organization Type |

Prior Relationship With Researcher |

Received Harvard Catalyst Pilot Grant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Round 1 Funded Seed Projects | |||||

| CBPR-G | Designing Interventions to Educate Minority Populations about Health Risks Associated with Elevated Sodium Intake | A community project to decrease sodium intake and improve hypertension. | Health center | ||

| CBPR-G | Assessing the Efficacy of Outreach Efforts and Mobile Mammography | To investigate the efficacy of specific strategies related to mobile mammography screening and inform future screening interventions. | Task force | ||

| CBPR-G | Comprehensive Needs Assessment of a Diverse Community | To gather information on what motivates people to make food choices and barriers that prevent them from making sustainable changes related to their health. | Coalition | ||

| CBPR-G | Examining Recent Increase in Teen Pregnancy in Roxbury | To explore implementation of a teen after school programs and its impact on teen health/health seeking behaviors and sexuality decision making. | Health center | ||

| CBPR-G | From Homeless to Housed: Assessing the Impact on Health Outcomes | To collect comprehensive data on housing and health outcomes among rough sleepers. | Homeless program | Yes | Yes |

| CBPR-G | Reducing the Risk: Effective HIV Outreach to Portuguese Speaker and New Immigrant Populations | To collect preliminary data evaluating the outcomes and impact of a Portuguese speakers HIV prevention program on HIV risk behaviors of the Portuguese community. | Community-based organization | ||

| CBPR-G | Screen time reduction: developing a family targeted preventive health campaign | To develop a culturally appropriate campaign and family education intervention to create a healthy home screen environment for children. | Community task force | ||

| CBPR-G | Use of a registry to promote optimal outcomes for childhood ADHD | To construct and deploy a childhood ADHD Registry to reduce adverse clinical outcomes in children with ADHD. | Health alliance | Yes | Yes |

| CBPR-G | Community Efforts to Address Outdoor Alcohol Advertising and Marketing in Greater Boston | To create a community dialogue around alcohol advertising, to collect map data of the current environment and explore social justice issues in communities with high exposure to alcohol advertising. | Community organization | ||

| CBPR-G | Women in Need: Exploration of an Alternative Sentencing Model for Commercial Sex Workers in Chelsea | To identify the components for a successful alternative sentencing program for commercial sex workers and explore the feasibility of implementing this program. | Hospital community benefits department | ||

| CBPR-G | Assessing Community Interest in Helping the Familial Caregivers of Latino Adults With Dementia | To ascertain the number of Latino families caring for a demented adult and identify barriers (e.g., language), resources (e.g., coalition-based) and needs unique to this population. | Elder services organization | Yes | |

| CBPR-G | Building a Haitian Church Base for Participatory Research | To expand and foster new relationships with Haitian pastors to identify health priorities of their congregations and gather input regarding culturally appropriate methods for recruitment and data collection. | Faith-based organization | Yes | |

| CBPR-G | Assessing Disparities in Reduction of Body Mass Index in Cambridge Youth | To understand recent increases in obesity among African American and low-income children. | Community task force | Yes | Yes |

| Round 2 Funded Seed Projects | |||||

| PB | Using GIS to Understand Community Health, Assets, Needs, and Disparities: Data-Sharing at the Neighborhood Level | To develop a partnership with a researcher and ultimately use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) related to health and wellness, to identify obesity causes, impacts and possible interventions. | Health department | ||

| PB | Exploring the Mental and Physical Health Impacts of Adolescent Girls' Experience With Dysmenorrhea and the Barriers to Treatment Through the Cultural Lens of the Portuguese-Speaking Community | To develop a partnership with a researcher and explore cultural issues that impact identification and intervention for various manifestations of painful periods (dysmenorrhea). | Women's group | ||

| PD | Promoting Cancer Screening Among Haitians in Faith-Based Settings | To understand Haitian disparities in cancer morbidity and mortality and to adapt, implement, and evaluate cancer control interventions for Haitians delivered in faith-based settings. | Community-based organization | Yes | |

| PD | Assessing the Impact of a Peer-Led Empowerment and Community- Building Program on Low-Income Women With Depression | To understand how peer-led empowerment and social support program created by and for low income women impacts low-income women struggling with depression. | Community organization | Yes | |

| PB | Using CBPR to Understand the Impact of a Parenting Intervention on Child Outcomes | To develop a partnership with a researcher to understand child and parental outcomes that are impacted by participation in a parenting program for at-risk parents. | Family support organization | Yes | |

| PD | The Community Health Education Project | To understand modalities that reduce the communication gap between communities and clinical providers on self-management and disease prevention and explore whether community health forums can improve the knowledge, skills, and health behaviors of participants. | Neighborhood organization | Yes | |

| PD | Community-Based Ultrafine Studies, Data Mapping, and Health Policy Forum | To collect ultrafine particulate air quality data and explore possible collaborations to devise more powerful methods of communicating environmental data to the public and include the community in the collection of air quality data. | Health department | Yes | Yes |

| PB | HEAP: Health Education and Awareness Project | To develop a partnership with a researcher to explore how to engage older foster care youth and professionals who work with them to identify health information to support their transition into adulthood. | Adoption and Foster Care Organization | ||

| Round 3 Funded Seed Projectsb | |||||

| PB | Integrated Care for Homeless and At-Risk Adults | To develop a partnership with a researcher to identify and address chronic pain management in a vulnerable homeless population through an integrated model of care. | Health center | Round 3 Seed Grant Recipients will apply for Harvard Catalyst pilot grants in Spring 2011. | |

| PB | The Men's Health League—It's Working, But Why? | To develop a partnership with a researcher to understand why a men's health intervention has been effective in reaching and engaging men of color. | Neighborhood settlement house | ||

| PB | Healthy Community Initiative | To develop a partnership with a researcher to explore community assets related to youth substance abuse/use, self-image, and suicide. | School system | ||

| PB | Association of Mental Health Diagnoses and Noncompliance With Birth Control Methods Among Urban Teens | To develop a partnership with a researcher to understand behavioral health factors associated with birth control noncompliance among teen women. | Health center | ||

| PB | Impact of a Community Educational Intervention on Kidney Disease Awareness and Health Outcome for African Americans in an Inner-City Neighborhood of Massachusetts | To develop a partnership with a researcher and track participant awareness and health outcomes resulting from an educational intervention focused on treatment options and transplantation for chronic kidney disease. | Support group | ||

| PD | Approaches for Integrating Depression Screening and Other Behavioral Health Issues Into Primary Care (Community Health Centers) Settings, Including Barriers and Facilitators | To understand patient mental health issues, ascertain coping skills, examine screening and referral patterns, barriers, and facilitators to integrating behavioral and primary healthcare and examine barriers to mental health care among African American patients. | Social service agency | Yes | |

| PD | Mental Health of the Newly Resettled Iraqi Families in Worcester | To examine mental health issues among Iraqi refugee individuals and families. | Coalition | Yes | |

In Year 1, we did not make a distinction between Partnership Building and Project development grants, but funded general CBPR projects (CBPR-G). PB are Partnership Building Grants (for or to encourage newly developing partnerships between community-based organizations and Harvard academic partners); PD are Project Development Grants (to develop a specific CBPR research project between community-based organizations and Harvard academic partners).

Round 3 Seed Grant Recipients will apply for Harvard Catalyst pilot grants in Spring 2011.

Applicants were offered information sessions (rounds 2 and 3) and individual project consultations to facilitate proposal preparation. Once funded, groups were invited to capacity-building sessions and offered consultation. In rounds 2 and 3, capacity building sessions were designed with participant input. Topics ranged from negotiating equitable community-researcher relationships to preparing proposals. Although we did not offer institutional review board training to grantees, we advised projects pursuing human subjects research to seek institutional review board approval. In round 3, based on feedback, we offered institutional review board and ethics training to grantees.

Seed grants were initially reviewed by researchers with CBPR expertise and then by researchers and community partners in rounds 2 and 3. Reviewers awarded grants to interdisciplinary projects that demonstrated the potential to impact human health.

Seed Grant Initiative Applications and Awards

The program distributed the round 1 RFP through community partner networks and CBPR program staff/investigators. In round 1, we received 14 applications and funded 13. In round 2, based on applicant feedback and CERAB interest, CERAB members became more actively engaged. They provided feedback on the RFP, reviewed proposals with investigators and determined funding priorities. In round 2, we received 14 applications and funded 8 (4 partnership building and 4 project development). In round 3, we received 14 applications and funded 7 (5 partnership building and 2 project development). Diverse projects and organizations were funded across the three rounds (Table 1). Groups varied in size, in prior relationships with researchers, funding, staffing (e.g., volunteer versus paid staff) and organizational type (e.g., coalition versus stand-alone organization). Unfunded applicants were also assisted in future application preparation, invited to capacity-building sessions, and offered consultation.

At the end of the seed grant award period, successful applicants were encouraged to apply for a $50,000 Harvard Catalyst pilot grant. The CBPR program provided additional technical assistance (e.g., proposal review) to applicants.

LESSONS LEARNED

To date, the CBPR seed initiative has distributed almost $100,000 in seed grants to community partners for numerous innovative projects and funded 28 organizations (Table 1). An important metric of success is the receipt of a Harvard Catalyst pilot grant. In Round 1, 7 out of 13 seed recipients applied for Harvard Catalyst pilot grants and three were funded. In round 2, three seed recipients applied for Harvard Catalyst pilot grants (one applicant was a round 1 recipient) and one was funded. This manuscript shares lessons learned and reflects a collaborative preparation and writing process.

Lesson 1: Designate Sufficient Time for CBPR Partnership and Project Development

Owing to restrictions on funding and the timing of pilot submission, we initially provided community partners with 3 to 4 months to complete their seed projects and prepare a pilot grant application. The time needed for CBPR versus traditional research has been noted throughout the literature13 and, not surprisingly, the allotted timeframe was insufficient. The seed grants do stimulate work beyond the allocated timeframe. For example, one round 1 recipient collaborated with their academic partner beyond the seed grant and applied for a pilot grant in round 2. Therefore, to address the barrier of time, we have extended the seed grant timeframe in round 3 to 8 to 12 months.

Lesson 2: Pathways to CBPR: Engaging Academic Investigators

Although the seed grant process successfully engaged a variety of community partners, it was challenging to find interested and skilled CBPR researchers. First, it was difficult to identify researchers with both CBPR experience and relevant content expertise. Second, few investigators in seed grant partnerships attended capacity-building sessions. Third, community partners struggled to accommodate investigator schedules. One seed recipient seeking an academic partner reached out to several senior CBPR researchers, but they were too busy to engage. She eventually connected with a junior investigator with content interest, but no CBPR experience or time to establish a partnership. As a result, she did not apply for a pilot grant despite her commitment.

We did identify researcher characteristics that facilitated involvement in CBPR—namely shared interests, preexisting community relationships, and prior CBPR experience. Furthermore, several junior researchers made efforts (e.g., traveling to community sites) to build rapport with their community partners. However, in general, we were unable to address persistent and systemic barriers to CBPR researcher involvement (e.g., lack of academic incentives to participate in CBPR),14 despite extensive outreach.

Researcher involvement continued to be affected by limited money to support researcher time. The seed money was initially strictly for community partners, although in round 3 community partners could fund academic partners at their discretion. Furthermore, the Harvard Catalyst pilot grants only supported 5% of investigator time (Harvard Catalyst requirements). Although 5% effort of a $50,000 pilot grant seemed feasible for academic researchers, we found few investigators committed to pursuing CBPR. Those with CBPR interest often lacked mentorship or could not commit time to building community partnerships. In addition, their interests did not always coincide with community selected topics. For example, one researcher remarked that a community partner was responsible for their shared CBPR project, raising questions about the researcher’s investment in the project.

We believe that these difficulties illustrate the national challenges facing community-engaged scholarship. There is a dearth of CBPR researchers and few experienced CBPR faculty mentors. The absence of protected academic time for CBPR and the negative impact of pursuing CBPR on tenure prospects are major systemic barriers to the growth of CBPR trained academics. Furthermore, few universities offer CBPR training opportunities. In response, we are launching a CBPR course at Harvard School of Public Health and incorporating CBPR into training opportunities at Harvard. We will also utilize capacity building sessions to explore (1) academic disincentives, (2) trajectories of successful CBPR researchers, and (3) CBPR funding and dissemination opportunities.

Lesson 3: Community Partners Have the Potential to Successfully Leverage Minimal Resources or Overextend Themselves in CBPR Work

For many seed awardees, limited seed dollars catalyzed successful projects. For example, one recipient used $7,500 to mobilize 10 organizations for a community needs assessment and dedicated small subgrants to 25 groups for this work. Her project resulted in a large needs assessment and action steps beyond the grant period. Another recipient subsequently received a Catalyst pilot grant to expand preliminary work on environmental health. Finally, a third seed recipient subsequently received a Catalyst pilot grant focused on the adoption of evidence-based guidelines in pediatric primary care related to attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD) (see Table 1 for project descriptions). We are developing an outcomes survey for funded projects to assess dissemination, funding, and policy outcomes and will explore whether organizational characteristics relate to these outcomes.

Despite these successes, some community partners initially proposed unrealistic goals. For example, the ADHD project proposed to pilot their child disease registry in 3 months, with $5,000. This applicant worked with staff to scale down his application and ultimately received a seed and pilot grant. We note that successful pilot applications took advantage of the individual consultation offered by the CBPR Program and incorporated this input into their proposals.

Although several community partners were able to leverage small resources for large impact projects, going forward it is critical that we illustrate the “true” cost of research. This enables community partners to develop realistic CBPR proposals and advocate appropriately for financial needs in CBPR partnerships.

Lesson 4: Community Context and Capacity Building: Barriers and Facilitators to CBPR

In both rounds, several community partners expressed interest but did not ultimately apply for a seed grant. Although we originally thought this was due to research readiness per se (e.g., knowledge of research methods), we subsequently identified other factors related to readiness and likelihood of application. Seed grant applicants were likely to have “contexts” that included well-developed networks/coalitions, a pool of people with skills and resources, a committed and interested leader, and a historical and shared community interest in an issue. For example, one community partner—a longstanding community coalition with a well-established investigator relationship—received a seed and subsequent pilot grant. This coalition’s access to people with relevant skills and historical interest in the issue facilitated this outcome.

In contrast, nonapplicant challenges included competing demands (e.g., research was not a priority), fragmented interest, unclear research expectations, and absence of an established academic partner. Similar challenges hindered seed recipients from applying for pilot grants. For example, after the Haiti earthquake, a Haitian partnership intending to submit a pilot application redirected resources from research into providing mental health services to their community. Another strong partnership was poised to submit a seed grant project for a pilot grant application. Several weeks before application, new political leadership dismissed a key task force member and the team did not submit a pilot grant. Finally, one seemingly strong seed applicant did not ultimately apply for a pilot grant due, in part, to the community partner’s historical mistrust of the academic investigator’s organization.

Context can influence the implementation, acceptance, success, and sustainability of CBPR. As such, it is critical to understand applicant organizations’ experiences with partnerships and priorities at the onset. Furthermore, given the unpredictability of environmental influences, it is important to facilitate partner capacity building that extends beyond specific projects. In this effort, we offered our grantees capacity building sessions, consultations and CBPR resources (e.g., grant and training notices). As a result, many seed grantees were informed and empowered to engage in opportunities beyond their seed grant. For example, one seed recipient successfully applied for and received a community-engaged research training program fellowship through another CTSA. Another seed recipient presented her project at a national conference. Finally, a third seed recipient received another Harvard Catalyst grant to empower patients to make informed health decisions. In summary, although the context can facilitate or hinder CBPR, community capacity building can empower communities to engage in CBPR opportunities that extend beyond specific projects and unpredictable environments.

Lesson 5: Plan, Learn, Change

Although this initiative was developed by the program staff, it is continually improved with ongoing community (CERAB and participant) input (Figure 1). CERAB members are not compensated for their feedback; however, they receive an honorarium to attend board meetings and they are considered an integral part of the seed grant initiative. To institutionalize their role, they recently formed a seed grant subcommittee. CERAB recommended changes include increased award amounts, changes to the types of grants offered (e.g., general CBPR grants versus partnership building and project development grants), and improvements to the RFP.

The iterative process described above incorporates the “Plan Do STUDY Act” process of quality improvement.14, 15 This tool, used in quality improvement efforts, allows one to test a change, by planning it, implementing it, observing the impact and results, and acting on what was learned. We hope this improves the seed grant initiative and ultimately leads to increasingly successful CBPR partnerships and projects.

CONCLUSION

The Harvard Catalyst CBPR Program’s seed grant initiative demonstrates an innovative collaborative approach to supporting numerous community–academic partnerships. This type of initiative can uniquely engage community partners in identifying research questions of community importance and stimulate new community–academic partnerships. In the future, we will measure long-term outcomes to assess the sustainability and success of funded projects. However, we anticipate that barriers such as suboptimal researcher engagement, community–academic matching, and time will pose continued challenges. Overcoming these challenges will require collaborative engagement of community partners, researchers, academic institutions, and funders.

The multifaceted value of CBPR to investigators and community partners needs to be defined and demonstrated, whether in the form of increased community capacity to engage in research and translate evidence to practice, improved research processes such as participant recruitment and retention, increased researcher engagement, or improved human health.

Engaging in this discourse and implementing the resulting strategies will benefit researchers, community partners, and communities in myriad ways whether in the form of community engagement in research, enhanced community research capacity, increased researcher engagement in CBPR, or ultimately improved human health. These benefits must be identified and defined by both communities and academic partners.

REFERENCES

- 1.Minkler M, Blackwell AG, Thompson M, Tamir H. Community-based participatory research: implications for public health funding. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:12103. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, Ciske S, Foley M, Fortin P, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83:102240. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lantz PM, ViruellFuentes E, Israel BA, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. J Urban Health. 2001;78:495507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silka L, Gleghorn GD, Grullon M, Tellez T. Creating community-based participatory research in a diverse community: a case study. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3:516. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru OK, Mangione CM. Partnering with community-based organizations: an academic institution’s evolving perspective. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed SM, Beck B, Maurana CA, Newton G. Overcoming barriers to effective community-based participatory research in US medical schools. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2004;17:14151. doi: 10.1080/13576280410001710969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. [accessed 2010 Mar 2];NIH roadmap for clinical research: clinical research networks and NECTAR. Available from: http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-networks.asp.

- 9.Sung NS, Crowley WF, Jr, Genel M, Salber P, Sandy L, Sherwood LM, et al. Central challenges facing the national clinical research enterprise. JAMA. 2003;289:127887. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.10.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zerhouni EA. Clinical research at a crossroads: the NIH roadmap. J Investig Med. 2006;54:1713. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.X0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wethington E, Breckman R, Meador R, Reid MC, Sabir M, Lachs M, et al. The CITRA pilot studies program: mentoring translational research. Gerontologist. 2007;47:84550. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson B, Ondelacy S, Godina R, Coronado GD. A small grants program to involve communities in research. J Community Health. 2010;35:294301. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9235-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Conference on com mu nitybased participatory research. Rockville (MD): 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer J. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. Br Med J. 2000;320:17881. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walton M. The Deming management method. New York: Putnam Publishing Group; 1986. [Google Scholar]