Abstract

Background

There is no guideline defining the optimal time from a positive screening fecal occult blood test to follow-up colonoscopy.

Methods

We reviewed records of 231 consecutive primary care patients who received a colonoscopy within 18 months of a positive fecal occult blood test. We examined the relationship between time to colonoscopy and risk of neoplasia on colonoscopy using a logistic regression analysis adjusting for potential confounders such as age, race, and gender.

Results

The mean time to colonoscopy was 236 days. Longer time to colonoscopy (OR=1.10, p=0.01) and older age (OR 1.04, p=0.01) were associated with higher odds of neoplasia. The association of time with advanced neoplasia was positive, but not statistically significant (OR 1.07, p=0.14).

Conclusions

In this study, a longer interval to colonoscopy after fecal occult blood test was associated with an increased risk of neoplasia. Determining the optimal interval for follow up is desirable and will require larger studies.

Keywords: Colonic Neoplasm, Occult Blood, Colonoscopy, Follow-up studies

II. Introduction

Colorectal cancer remains a leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. Screening asymptomatic individuals with yearly fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) has been shown to decrease mortality from colon cancer.[1–4] Furthermore, colorectal cancers detected by FOBT screening are diagnosed at an earlier, more manageable, stage [5] and are associated with lower costs than symptom-diagnosed cancers. [6]

The current screening guidelines recommend that a positive FOBT should be followed by a complete colon evaluation with colonoscopy.[7] However, the timing of the colonoscopy is not specified and there is no evidence defining the optimal time from a positive screen to follow-up testing. A recent Veterans Health Administration (VHA) study found that only 44 percent of patients underwent a full colon evaluation within 12 months of positive FOBT. [8] In fact, in 2004, the average time from positive FOBT to colonoscopy for asymptomatic patients in the VHA was 199 days. [9] In light of these findings, the VHA has recently issued a performance monitor measuring the proportion of positive FOBT with a follow-up colonoscopy within sixty days. [10]

The concern underlying this performance monitor may be that a delay to diagnosis will lead to poorer health outcomes. However, published studies do not support this supposition.[11–13] Furthermore, no study has yet examined time delay from FOBT to colonoscopy and its relationship to outcome. We were interested in whether a delay in pursuing colonoscopy after positive FOBT would result in more advanced disease at the time of the colonoscopy. We hypothesized that the probability of finding neoplasia at the time of colonoscopy after a positive FOBT would not be associated with the timing of that colonoscopy.

III. Methods

Settings & Data

The patient and colonoscopy data collection has been previously described.[8] Briefly, 676 consecutive patients, age 45 and older, with a positive FOBT ordered from a primary care clinic between March 1, 2000 and February 28, 2001 were identified using the laboratory database and electronic VHA medical record. Patients’ age, gender, race, date of positive FOBT, date of colonoscopy and findings on colonoscopy were abstracted by trained personnel onto a standardized data abstraction form. Additionally, the pathology results for tissue removed at colonoscopy were abstracted for this study. Patients were excluded from the analysis if they had an FOBT sent for indications other than colorectal cancer screening, if they did not undergo colonoscopy within 18 months of the FOBT, or if the colonoscopy was performed outside of the VHA and pathology results were not available. Thus, the final number of subjects available for analysis was 231.

For the FOBT, per usual clinic protocol, a nurse gave patients the three stool cards (Hemoccult SENSA ®, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) and instructions. The patients collected the stool at home and returned the stool cards to the VHA facility. All FOBTs were processed and interpreted without rehydration in the central clinical laboratory. If any of the three cards were positive for occult blood, then the FOBT result was “positive.” All colonoscopies were performed on-site by a gastroenterology trainee under the supervision of a board-certified gastroenterologist or an attending gastroenterologist operating independently. Biopsies were reviewed by the medical center pathology department.

The primary explanatory variable was time (in days) from positive FOBT to colonoscopy. The primary outcome variable was the most advanced lesion on colonoscopy, which was classified as: no adenoma, adenoma, advanced adenoma or invasive cancer. Advanced adenomas were defined as having a diameter of 10mm or more, villous architecture (>25% villous), high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma.[14] Invasive cancer was defined by invasion beyond the muscularis mucosae. For analysis, any adenoma was considered “neoplasia” and advanced adenomas and invasive cancer were considered “advanced neoplasia.”[15] This categorization was determined prior to the analysis to reflect clinically relevant categories that may influence health policy decisions.

Statistical Analysis

Our primary aim was to understand the effect of time from FOBT to colonoscopy on the risk of neoplasia and advanced neoplasia. Descriptive statistics were computed for neoplasia and advanced neoplasia, time to colonoscopy, and the covariates age, race, and gender. In an effort to understand the possible role of confounding by age, race, and gender, we calculated bivariate measures of association between the covariates and time to colonoscopy using two-sample t-tests (race, gender) and Pearson’s correlation (age). [16] Statistical analyses of the primary outcome measures neoplasia and advanced neoplasia were conducted using logistic regression conditional on time to colonoscopy and adjusting for possible confounding covariates.[17]

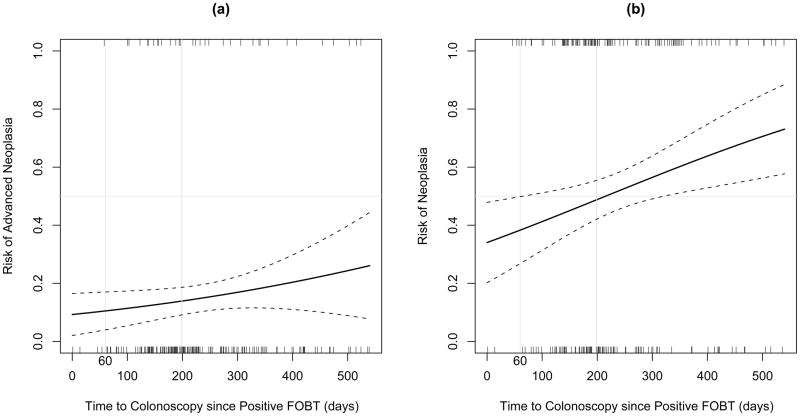

To aid in the interpretation of the results, predicted probability plots based on the fitted logistic regression models were produced. These plots describe the marginal effect of time to colonoscopy since positive FOBT on the risk of neoplasia and advanced neoplasia, averaged over the covariates. Point-wise confidence intervals for the predicted probabilities (pt) were computed using the delta method.[18]

All analyses were conducted using R version 2.5.0 for Windows (R Development Core Team (2007)).

IV. Results

The baseline characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The majority (97%) of subjects were male and Caucasian though over a third were African-American. Approximately half the subjects had no neoplasia on colonoscopy. Fifteen percent had advanced neoplasia, including nine patients with invasive cancer. The mean time to colonoscopy was 236 days with a median of 201 days.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Characteristic | Results (N=231) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 66 (9.6) |

|

| |

| Gender | |

| Male | 225 (97%) |

| Female | 6 (3%) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 137 (59%) |

| African-American | 74 (32%) |

| Hispanic | 2 (1%) |

| Missing/Unknown | 18 (8%) |

|

| |

| Time to Colonoscopy, days (mean, SD) | 236 (112) |

|

| |

| Colonoscopy Findings | |

| No Adenoma | 112 (48%) |

| Adenoma | 84 (36%) |

| Advanced Adenoma | 26 (11%) |

| Invasive Cancer | 9 (4%) |

We first examined the bivariate associations between patient characteristics and time to colonoscopy (Table 2). Mean time to colonoscopy was significantly longer in non-Caucasians (258 days) as compared to Caucasians (220 days, p=0.01). Age (p = 0.12) and gender (p = 0.91) were not significantly associated with time to colonoscopy.

Table 2.

Bivariate Comparisons of Time to Colonoscopy since Positive FOBT

| Time to colonoscopy Mean days (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 236 (111) | 8 (−162, 177) | 0.91 |

| Female | 228 (162) | * | * |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Caucasian | 220 (111) | −38 (−67, −8) | 0.01 |

| Non-Caucasian | 258 (111) | * | * |

|

| |||

| Colonoscopy Findings | |||

| No Adenomas | 220 (105) | * | * |

| Adenomas | 248 (113) | 28 (−3, 59) | 0.08 |

| Advanced Adenomas | 256 (123) | 36 (−17, 90) | 0.17 |

| Invasive Cancer | 265 (153) | 46 (−73, 164) | 0.40 |

Denotes the reference category.

P values correspond to two-sample t-tests of the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean time to colonoscopy since positive FOBT with respect to the reference category.

Table 2 also lists mean time to colonoscopy stratified by findings on colonoscopy. Differences in mean time to colonoscopy between patients in the adenoma, advanced adenoma, and invasive cancer groups as compared to the no adenoma group (reference category) were not statistically significant. The data, however, suggest a trend such that longer time to colonoscopy was associated with more advanced findings on colonoscopy (ANOVA trend test, p = 0.04).

Results from a logistic regression analysis of neoplasia and advanced neoplasia are described in Table 3. For the analysis with neoplasia as outcome, all covariates (age, race, and gender) were entered into the model. Gender could not be included in the advanced neoplasia model because there were no females with advanced neoplasia in our sample. Longer time to colonoscopy was associated with higher odds of neoplasia (OR = 1.10 for each additional 30-day wait; 95%CI = 1.02, 1.19). Though positively correlated, the association between time to colonoscopy and advanced neoplasia was not statistically significant (OR = 1.07; 95%CI = 0.98–1.18). Older age was associated with higher odds of neoplasia (OR = 1.04 for each additional year; 95%CI =1.01–1.07) but not significantly associated with advanced neoplasia (OR = 1.02; 95%CI = 0.98–1.06). There was no association between race and odds of neoplasia.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Advanced Neoplasia and Neoplasia

| Variable | Advanced Neoplasia | Neoplasia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p value | |

| Time to Colonoscopy* | 1.07 | 0.98–1.18 | 0.14 | 1.10 | 1.02–1.19 | 0.01 |

| Age (years) | 1.02 | 0.98–1.06 | 0.43 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.01 |

| Caucasian** | 1.25 | 0.58–2.67 | 0.57 | 1.38 | 0.79–2.41 | 0.26 |

| Male*** | NA | NA | NA | 2.33 | 0.37–14.74 | 0.37 |

Scaled to reflect the effect of an additional 30-day wait from positive FOBT

Non-Caucasian is the reference category.

Female is the reference category. There were no females with advanced neoplasia in our sample; thus we could not enter gender as a covariate in our advanced neoplasia model.

The effect of time to colonoscopy is further illustrated in Figure 1, which displays the predicted probability (e.g., risk) of advanced neoplasia (a) and neoplasia (b) as a function of time to colonoscopy since positive FOBT. The plots are based on the fitted logistic regression models described above. Notably, the effect of time to colonoscopy on the risk of disease is more pronounced in subjects with neoplasia as compared to advanced neoplasia. However, the slope is also positive in the advanced neoplasia plot, reflecting the increased odds of advanced neoplasia identified in our model.

Figure 1.

V. Discussion

In this secondary data analysis from a single VHA medical center, we found a significantly increased risk of neoplasia associated with delay to colonoscopy, even after adjusting for age, gender and race. The risk of advanced neoplasia also appeared to increase, though the relationship did not meet criteria for statistical significance.

These finding were not anticipated and contrasted with our original hypothesis that there would be no difference in risk of advanced disease in patients receiving colonoscopy within 60 days as compared to those receiving the test within 199 days. This hypothesis was based on the assumption that the average time for an adenomatous polyp to become invasive is 10 years and bleeding may begin an average of two years before an adenoma becomes invasive. [19] Thus, a delay to colonoscopy of a few months in average risk patients should not alter the course of disease.

In fact, previous studies have not uncovered a significant relationship between time to diagnosis and outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Fernandez and colleagues found no significant association between the time interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis and the risk of death from digestive tract cancers including esophagus, stomach, colon and rectum.[11] Similarly, Porta et al reported that time to diagnosis from symptoms onset was not a significant predictor of survival.[13] Instead, longer time to diagnosis actually was associated with a decreased risk of death. This latter finding was echoed in the work of Rupassara et al in Great Britain who report that patients with colorectal cancer who had a delay between referral and diagnosis had less aggressive tumors than those without delay.[12] To our knowledge, our analysis is the first to examine the effect of time delay in the context of screening.

One possible explanation for the unexpected finding in our analysis is residual confounding in our regression model. Delay to colonoscopy may, in fact, be a proxy for other factors that modify the risk of neoplasia. For example, obesity has been associated with an increased risk of adenoma growth [20,21] and could also make obtaining a colonoscopy more difficult. Alternatively, patients who delayed their colonoscopy may also have been more likely to delay their FOBT testing. We attempted to minimize the potential impact of this confounder by excluding patients from the analysis who had FOBT sent for reasons other than screening (i.e. symptoms). As a result, a delay in returning the FOBT cards should not have biased the results. Nevertheless, we cannot be certain that patients did not develop symptoms between the time the FOBT was ordered and the time it was returned.

An additional explanation for our findings is that the FOBT and colonoscopy were not actually related. It is conceivable that colonoscopies were not ordered as a direct result of a positive FOBT but rather for another reason, such as the development of symptoms concerning for colorectal cancer. This concern is higher for those colonoscopies performed long after the FOBT and thus could explain the increased risk of disease with increasing time to colonoscopy.

Finally, recent advances in the understanding of colorectal cancer pathogenesis have uncovered multiple distinct pathways of tumor progression that could explain our findings.[22,23] There may be populations of patients with accelerated disease progression in which a few months can make a difference in polyp development or progression. It is unlikely that our population was homogenous in this regard, but the presence of a small proportion of patients with these accelerated pathways could have affected our results. Better understanding these pathophysiologic variations in colorectal cancer development may allow a more personalized approach to colorectal cancer screening and polyp surveillance.

Another provocative finding from our analysis is the longer delay to colonoscopy in non-Caucasian veterans when compared to Caucasians. The non-Caucasian category was predominately African-American though also included self-declared Hispanic and Asian veterans. We adjusted for this racial difference in our logistic regression model, and so we do not think that it explains the apparent association between time to colonoscopy and findings at the time of colonoscopy. Unfortunately, we do not have sufficient information in this analysis to explain the difference in delay. However, it remains of interest and will be further explored in future studies.

These surprising findings must be interpreted in the context of the study limitations. Firstly, this study analyzes data originally collected for clinical documentation and then abstracted to examine the primary outcome of whether or not a colonoscopy had been performed within 18 months of a positive FOBT.[8] Therefore, this is not an analysis of the natural history of patients with a positive FOBT. The natural history of these patients would be best understood using repeated colonoscopies over the short-term to identify and sample new and existing polyps. However, the risks to the subject in such a study will remain prohibitive until less invasive techniques are available to reliably examine polyps in vivo.

Secondly, the small number of subjects with advanced neoplasia limited the power of our analysis to detect statistically significant differences within this group. Nevertheless, our probability plot (figure 1a) suggests that there may be a clinically relevant relationship between delay to colonoscopy and risk of advanced neoplasia. Further studies will need to be adequately powered to definitively determine whether such a relationship exists.

Lastly, this study was performed at a single VHA facility and may limit its generalizability to non-veteran and female populations. Unfortunately, data for comparison of time to colonoscopy in these populations is limited. Our data may be at least representative of the national veteran population in that the test characteristics of our FOBT were similar to a large national observational study within the VHA system.[24] Similarly, the proportion of subjects with positive FOBT and invasive cancer in our study is comparable to that found in a multi-center randomized trial in the civilian population. [3]

In summary, this secondary data analysis demonstrates a significantly increased risk of neoplasia associated with delay to colonoscopy. The absolute risk increase per day is minimal, but it becomes more pronounced when large delays are encountered. Further studies examining the risk of advanced neoplasia may be helpful for policy-makers when discussing performance guidelines for follow up of positive FOBT. Until these studies are completed, our analysis would support timely follow-up of positive fecal occult blood tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statement of Support

This study was funded in part by NIH T32 DK007568-17 (Dr Gellad). Dr. Fisher was supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA03-174). Dr. Provenzale was supported by an NIH K24 (DK002926-07).

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

VII. Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

VI. References

- 1.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–1477. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Jorn O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365–1371. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305133281901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Towler B, Irwig L, Glasziou P, Kewenter J, Weller D, Silagy C. A systematic review of the effects of screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. BMJ. 1998;317:559–565. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7158.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond JH. The place of fecal occult blood test in colorectal cancer screening in 2006: the U.S. perspective. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:219–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramsey SD, Mandelson MT, Berry K, Etzioni R, Harrison R. Cancer-attributable costs of diagnosis and care for persons with screen-detected versus symptom-detected colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1645–1650. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex DK, Bond JH, Randall B, Ferruci J, Ganiats T, Levin TR, Woolf S, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litin S, Simmang C. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale - update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Coffman CJ, Fasanella k. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1232–1235. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daigh JD. Healthcare Inspection: Colorectal Cancer Detection and Management in Veterans Health Administration Facilities. InWashington, DC: VA Office of Inspector General; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.VHA directive 2007–004. 2007 Jan 12; available at http://www1.va.gov/cancer/

- 11.Fernandez E, Porta M, Malats N, Belloc J, Gallen M. Symptom-to-diagnosis interval and survival in cancers of the digestive tract. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2434–2440. doi: 10.1023/a:1020535304670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rupassara KS, Ponnusamy S, Withanage N, Milewski PJ. A paradox explained? Patients with delayed diagnosis of symptomatic colorectal cancer have good prognosis. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Porta M, Gallen M, Malats N, Planas J. Influence of “diagnostic delay” upon cancer survival: an analysis of five tumour sites. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:225–230. doi: 10.1136/jech.45.3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lieberman D, Weiss DG, Bond JH, Ahnen DJ, Garewal H, Chejfec G. Use of colonoscopy to screen asymptomatic adults for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:162–168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007203430301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lieberman D, Prindiville S, Weiss DG, Willett W. Risk factors for advanced colonic neoplasia and hyperplastic polyps in asymptomatic individuals. JAMA. 2003;290:2959–2967. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobson JD. Applied Multivariate Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Vaart . Asymptotic Statistics. Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eddy DM. Screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:373–384. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-5-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Almendingen K, Hofstad B, Vatn MH. Does high body fatness increase the risk of presence and growth of colorectal adenomas followed up in situ for 3 years? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2238–2246. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moghaddam AA, Woodward M, Huxley R. Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of 31 studies with 70,000 events. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2533–2247. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jass JR, Whitehall VLJ, Young J, Leggett BA. Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:862–876. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jass JR. Molecular heterogeneity of colorectal cancer: Implications for cancer control. Surgical Oncology. 2007;16:S7–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberman D, Weiss DG. One-time screening for colorectal cancer with combined fecal occult-blood testing and examination of the distal colon. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:555–560. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.