Abstract

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus (SC-PSD) is an acquired condition usually seen in young adults especially males. This prospective study has been performed to determine effects of the Limberg flap rotation surgery for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus, its feasibility to the patients, their compliance, and outcomes such as wound infection, postoperative pain relief, recurrence rates, and return to work. A total of 30 patients were operated by the same two surgeons from January 2009 to June 2011, including both primary and recurrent diseases, and patients with previous incision and drainage done for the pilonidal abscess. All patients successfully underwent surgery, with very minimal postoperative pain, stayed in hospital for average 5 days, returned to work after 3 weeks, with 3 patients having flap edema, 2 having flap necrosis, and no recurrences so far. Patients with flap edema and flap necrosis took 2–3 weeks to heal with regular dressing and antibiotic usage. Limberg flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus was found very useful and sound in terms of postoperative pain, infection rates, and early return to work with almost nil recurrences.

Keywords: Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus, Limberg flap, Flap necrosis, Wound infection

Introduction

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus is a common disease of the adult age group, especially male population, causing significant morbidity from both disease and surgery done for the same. It is essentially a cleavage between the buttocks (i.e., natal cleft), and diagnosis is made by identifying the epithelialized follicle opening (i.e., sinus). The name pilonidal is taken from Latin meaning “nest of hairs.”

The estimated incidence is 26 per 1,00,000 people [1, 2]. It generally presents as a cyst, abscess, or sinus tracts with or without discharge [3]. Men affected more often than women [1], rare both before puberty and after the age of 40 years [4]. Rarely may it present in the fourth decade [4].

The etiology of the pilonidal sinus is a matter of controversy. This condition was probably first described by Mayo in 1833, who suggested that it was due to congenital origin secondary to a remnant of an epithelial lined tract from postcoccygeal epidermal cell rests or vestigial scent cells. Now the view widely shifted toward acquired theory [5] is based on the observations that congenital tracts do not contain hair and are lined by cuboidal epithelium. A widely acceptable view is that they are caused by local trauma, poor hygiene, excessive hairiness, and presence of deep natal cleft [6]. Karydakis proposed three main factors causing the disease, namely high quantity of hair, extreme force, and vulnerability to infection [7].

The management of the sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus varies from clipping of hairs with good hygiene of the area, wide excision of the area, and newer flap procedures, but none is widely accepted [8]. Excision and packing, excision and primary closure, marsupialization, and flap techniques are the surgical procedures that have been suggested for the treatment [9].

The main concern for the treatment to the patient is the recurrence; the literature review suggested that it ranged from 20–40 % regardless of the technique used [10]. Many reasons were attributed to recurrence, such as leaving behind some tracts, sutures in midline causing more trauma with repeated infection accumulation of perspiration, and friction with tendency of the hair getting incorporated into the wound [11].

Limberg rhomboid flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus was designed by Limberg in 1946 [12], who described a technique for closing a 60 ° rhombus-shaped defect with a transposition flap. This flap was easy to perform, with sutures away from the midline giving rise to a tensionless flap of unscarred skin in the midline, which helps in good hygiene maintenance, reducing sweating maceration, erosions, and scar formation.

Literature study showed that Limberg flap reconstruction following rhomboid excision of the sinus area was superior to primary closure [13] and other flap procedures [14] and a safe and reliable method in sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease with low complication and recurrence rates.

Hence, this study was performed in our setup to evaluate the usefulness of Limberg flap procedure in sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus, patient compliance, complications, and long-term recurrence rates following the procedure.

Material and Methods

The study involves 30 patients, from January 2009 to July 10, 2011. Most of the patients were males; of those 6 were females. Average age was 24 years—the oldest was 29 years and the youngest was 15 years.

Procedure

The patient was put in prone position, under SA with buttocks strapped apart.

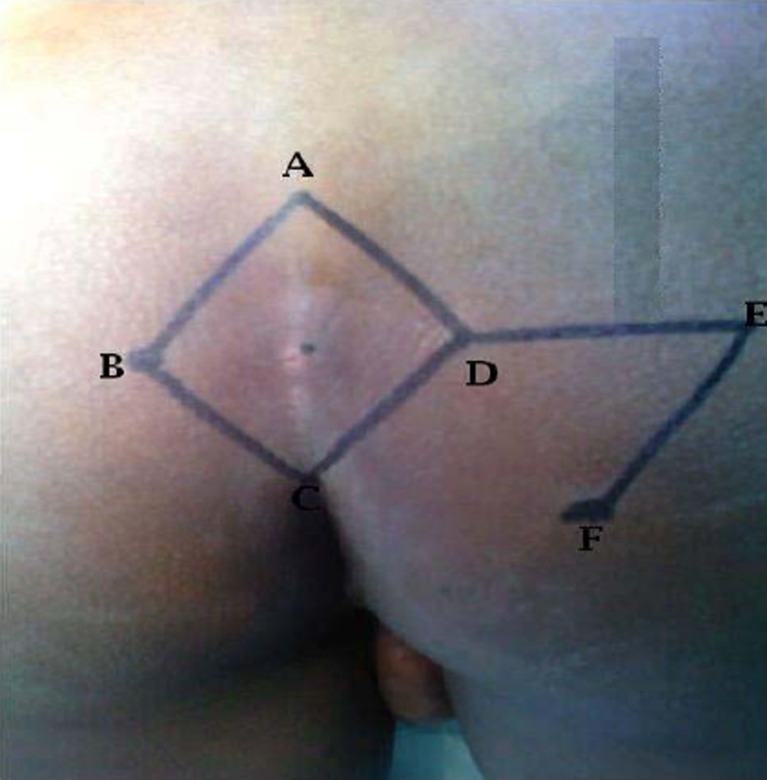

A rhombic area of skin is marked over pilonidal sinus involving all midline pits and lateral extension if any. The long axis of the rhomboid in midline is marked as A–C, C being adjacent to perianal skin, A placed so that all diseased tissues can be included in the excision. The line B–D transects the midpoint of A–C at right angles and is 60 % of its length. D–E is a direct continuation of the line B–D and is of equal length to the incision B –A, to which it will be sutured after rotation. E–F is parallel to D–C and of equal length. After rotation, it will sutured to A–D (Figs. 1 and 2) [16].

Fig. 1.

Initial marking

Fig. 2.

Marking with letters

The skin and subcut fat to be removed is excised down to deep fascia, and a rhomboid area of specimen including pilonidal sinus and its all extensions are removed (Fig. 3). Then flap is raised so that it includes skin, subcut fat, and the fascia overlying gluteus maximus, rotated to cover midline rhomboid defect (Fig. 4). The defect thus created can be closed in linear fashion (Fig. 5). Deep absorbable sutures to include fascia and fat are placed over a vacuum drain, and then finally the skin is closed in interrupted sutures [15].

Fig. 3.

Excision till deep fascia

Fig. 4.

Raising of flap and rotating over the defect

Fig. 5.

Suturing in linear fashion

The operation produces a tension-free flap of unscarred skin in the midline (Fig. 6). Antibiotics were given for 7 days initially intravenously, then orally, suction drain removed after 2 days, sutures removed around 10th day. The patient was advised not to put pressure on the flap for 3 weeks.

Fig. 6.

Final outcome after suturing

Results

In this study 30 patients were included. Among them 24 were males and 6 were females. Mean age was 24 years (range 15–29 years). Of the 30 patients, 14 had primary disease, 6 had recurrent disease, and 10 came up after having previous incision and drainage for abscess.

All patients came with pilonidal sinus, from January 2009, were assessed for its severity and investigated, and then they underwent Limberg flap surgery under spinal anesthesia. Postoperatively patient made to lie on sides, then made them ambulant after first postoperative day, with drain in situ. The patient received antibiotics and regular dressing of the wound. Drain was removed approximately on the second postoperative day, following which the patient got discharged with advice of not to pressure for 3 weeks. Sutures were removed during follow-up around 10th day. All patients are followed up initially 2 weekly interval, then bimonthly for next 1 year. Two female patients had complications—one had flap necrosis and the other had persistent serous discharge from the wound. It took 3 weeks to heal completely with diligent dressing and usage of antibiotics. Three patients had flap edema, which resolved by 10 days. One had persistent discharge at the tip which took 4 weeks to settle down, since he was HbsAg positive and had two surgeries before. All other patients wound healed nicely with minimal scarring, with very less postoperative pain, with no recurrence so far. None needed readmission due to pilonidal sinus, and most patients returned to work after 3 weeks.

Discussion

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus is blind epithelial tract situated in the skin of the natal cleft, close to anal verge, generally containing hair. The etiology is matter of debate; initially congenital origin was thought of which is now given up. Main causes for the formation of this sinus are hirsuitism, sweating in the area, repeated maceration due to trauma, leading to breakage of the skin barrier, attracting hair inside which initiates a foreign body reaction leading to infection with abscess or sinus formation.

Surgical treatment for this sinus is by the way of excision of the diseased tissue down to the sacrococcygeal fascia, but the next step of what to do with defect is a matter of concern. In this regard, one has to take into account of patient compliance, postoperative pain, infection and recurrence rates, hospital stay, frequent wound dressings, and cosmetic outlook with preservation of the bottom.

Reconstruction of the defect with Limberg flap has many advantages as it is easy to perform and design, and it flattens the natal cleft with large vascularized pedicle, sutured without tension. This in turn maintains good hygiene, reducing the friction, preventing maceration, and avoiding scar in the midline. This flap procedure found better than simple excision and closure, marsupialization [13, 14], other flap procedures such as bescom and Karydakis [17, 22]. Several series reported recently about the usefulness of this flap in treatment for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus have been comparable with our series in terms of complications and recurrences. Katsoulis had 25 patients, with 16 of them having complications with no recurrences [18]. Aslam had 110 patients, with 5 of them having complications and 1 recurrence [19]. Mentes and Urhan were other studies [20, 21]. In our series we had two complex wound infections, three minor flap edemas, and one flap tip discharge—all healed in due time. No recurrence was reported so far.

Conclusions

Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus is headache to both the patient and the treating physician because of its repeated infection, persistent pain with discharge, and high recurrence rates with regular procedures. Following Limberg flap reconstruction after excision of the pilonidal sinus, the patient got immense relief from the weeping and smelling bottom without distortion of the contour of the bottom.

The technique is easy to perform in quick time, useful in both primary and recurrent diseases, with very low complication and recurrence rates, which further can be reduced by meticulous skin closure, without skin edge eversion, with a wide flap to obliterate the midline natal cleft.

Other advantages are quick healing time, short hospital stay, and early return to daily life.

References

- 1.Humphries AE, James E. Evaluation and management of pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2010;90(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sondenaa K, Andersen E. Patient characteristics and symptoms of in chronic pilonidal sinus disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10(1):39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00337585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hull TL, Wu J. Pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1169–1185. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the post anal pilonidal sinus. Ann R College Surg England. 1984;66(3):201–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brearley R. Pilonidal sinus: a new theory of origin. Br J Surg. 1955;43:62–68. doi: 10.1002/bjs.18004317708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bascom J. Pilonidal disease: origin from follicles of hairs and results of follicle removal as treatment. Surgery. 1980;87:567–572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust NZJ Surg. 1992;62:385–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiedozi LC, AlRayyes FA, Salem MM, Al Haddi FH, Al-Bidwei AA. Management of pilonidal sinus. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:786–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohamed HA, Kadry I, Adly S. Comparison between three modalities for non-complicated pilonidal sinus disease. Surgeon. 2005;3(2):73–77. doi: 10.1016/S1479-666X(05)80065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger A, Frileux P. Pilonidal sinus. Ann Chir. 1995;49:889–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casetecker J, Mann BD, Castellanes AF, Strauss J (2006) Pilonidal disease. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article192668. Accessed 11 Dec 2011

- 12.Wolfe SA, Limberg AA, M.D., 1894-1974 (1975) Plastic and reconstructive surgery 56(2):239–240 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Akca T, Colak T. Primary closure with Limberg flap in treatment of pilonidal sinus-randomized clinical trial. BJS. 2005;5074:1081–1084. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Azab AS, Kamal MS, Saad RA, Abount AL, Atta KA, Ali NA. Radical cure of pilonidal sinus by a transposition rhomboid flap. BJS. 1984;71(2):154–155. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800710227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapan M, Kapan S, Pekmezci S, Dugun V. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus disease with Limberg flap repair. Tech Coloproctol. 2002;190:388–392. doi: 10.1007/s101510200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farquharson EL, Rintoul RF (2005) Farquharson's Textbook of operative general surgery, 9th edn. Hodder Arnold Publication, London, pp 457–458

- 17.Mentes O, Bagci M, Biglin T, Ozgul O, Ozdemir M. Limberg flap procedure for pilonidal sinus diseased: results of 353 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393(2):185–189. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katsoulis IE, Hibberts F, Carapeti EA (2006) Outcome of treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus with Limberg flap. Surgeon 4(1):7–10, 62 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Aslam M, Choudhry A (2009) Use of Limberg flap for pilonidal sinus—a viable option. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 21(4) [PubMed]

- 20.Urhan MK, Kuckel F, Topgul K, Ozer I, Sari S. Rhomboid excision and Limber flap for managing pilonidal sinus: results of 102 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:656–659. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6263-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mentes BB, Leventoglu S, Cihan A, Tatlicioglu E, Akin M, Oguz M. Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Surg Today. 2004;34(5):419–423. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2725-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Can MF, Sevinc MM, Hahcerliogullari O, Yilmaz M, Yagci G. Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200(3):318–327. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]