Abstract

A drug interaction is a process by which a drug or any other substance interacts with another drug and affects its activity by increasing or decreasing its effect, causing a side effect or producing a new effect unrelated to the effect of either. Interactions may be of various types-drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, drug-medical condition interactions, or drug-herb interactions. Interactions may occur by single or multiple mechanisms. They may occur in vivo or in vitro (pharmaceutical reactions). In vivo interactions may be further subdivided into pharmacodynamic or pharmacokinetic reactions. Topical drug interactions which may be agonistic or antagonistic may occur between two drugs applied topically or between a topical and a systemic drug. Topical drug-food interaction (for example, grape fruit juice and cyclosporine) and drug-disease interactions (for example, topical corticosteroid and aloe vera) may also occur. It is important for the dermatologist to be aware of such interactions to avoid complications of therapy in day-to-day practice.

Keywords: Drug, interactions, pharmacodynamic, pharmacokinetic, topical

Introduction

What was known?

1. A drug or substance may interact with another drug or substance to cause alteration in effect or production of new effect.

2. Drug interactions may be of various types: Drug-drug, drug food, drugherb and drug-disease interaction.

3. Topical drug interactions may occur between topical-topical drugs or between topical-systemic drugs.

Alteration of the effects of a drug by reaction with another drug or drugs, with foods or beverages, with herbs, or with a pre-existing medical condition is known as drug interaction.[1] Drug interactions may be classified as drug-drug interactions, drug-food interactions, drug-medical condition interactions, or drug-herb interactions. This article will focus on different potential mechanisms of drug interactions and their clinical significance, with special interest to dermatological pharmacotherapy. Some drugs interact by a single mechanism, but some others do so by two or more mechanisms acting in concert. Drug interactions occurring outside the body are known as in vitro (pharmaceutical) reactions, whereas those occurring inside (the living body) are known as in vivo reactions. On the basis of the mechanism of action, in vivo interactions can be further subdivided into two categories pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. Drug interactions leading to serious adverse effects are known as unfavorable drug interactions. When multiple drugs are used simultaneously the patients should be under the watchful scrutiny of a doctor so that unfavorable interactions if any may be detected immediately. In some rare instances, the drug interaction may go in favor of the patient and prove to be beneficial – such interactions are known as favorable drug interactions. For example, a combination of antibiotics such as amoxicillin and clavulanic acid interact to augment each other's actions. Hence it is important for the dermatologists to be aware of both favorable and unfavorable interactions.[2] Fortunately, in many instances in dermatological practice, adverse interactions do not reach a magnitude of recognizable clinical concern. Rarely does the interaction result in a serious adverse outcome. Unfavorable drug interactions may lead to increased toxicity, decreased efficacy, or both. The possibility of interaction with over-the-counter drugs, herbal medicines, or various items of food should also be borne in mind. One must be extra cautious when a new drug is added to a treatment regimen because of the increased risk of drug-induced toxicity or therapeutic failure. It is a Herculean task to remember all possible drug interactions. A ready-to-refer checklist of drug interactions related to dermatological pharmacology can be a useful tool for clinical dermatological practice.[3]

Drug-drug Interactions

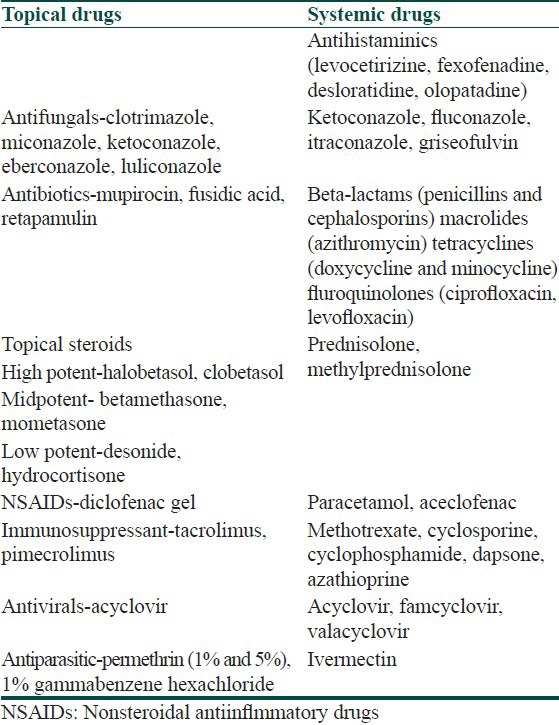

Commonly used drugs in dermatological practice are mentioned in Table 1. A drug-drug interaction occurs when two drugs are simultaneously present in the body and one drug alters the serum/tissue levels and mechanism of action of the other. The risk factors for such interactions may lie with the patient or with the drugs. High-risk patients are infants, children and the elderly, those who have multiple disease, those who are on multiple drug therapy, and those with renal or hepatic impairment.[4] High-risk drugs are those with a narrow therapeutic index or drugs that are recognized enzyme inhibitors or inducers. The therapeutic index of a drug is the ratio of the amount of drug needed to produce the desired therapeutic effect in relation to the drug dose that can produce toxicity. If this ratio is close to one, then the drug is said to have a narrow therapeutic index. Examples of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index are cyclosporin, methotrexate, doxepin, digoxin, theophyllin, and warfarin. The interaction may be favorable or unfavorable. Favorable interactions occur when the effect of the interaction is desired, for example, interaction between amoxycillin and clauvulinic acid. However, unfavourable reactions are undesirable and may be caused either by the doctor prescribing the wrong drug combination or by the patient taking more than one drug, particularly over-the-counter medication or consuming a drug with other substances such as vitamins, herbals, caffeine, nicotine, or alcohol.

Table 1.

Commonly used drugs in dermatological practice

Drug-drug interactions may be classified into pharmacokinetic interactions and pharmacodynamic interactions.

Pharmacokinetic Interactions

Interactions that can affect the processes by which drugs are absorbed, distributed, bound by plasma protein and sequestrated, metabolized, and excreted are known as pharmacokinetic drug interactions.[5]

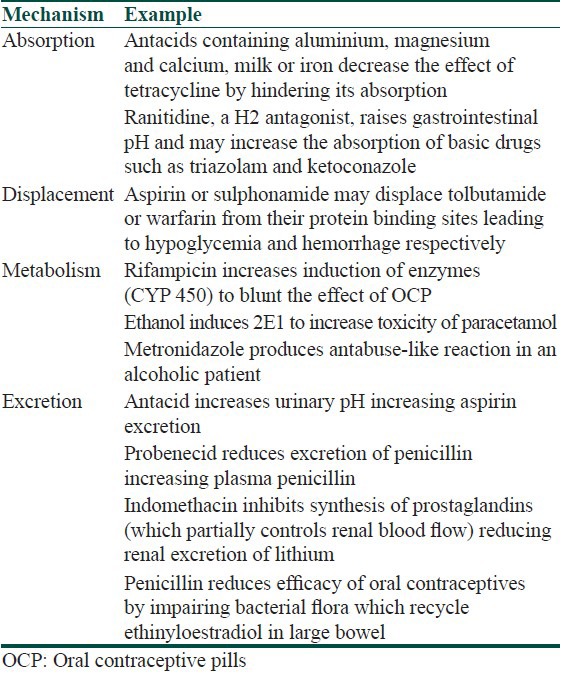

Table 2 lists some of the drug interactions that result from these changes. The mechanisms that alter absorption involve the formation of drug complexes that reduce absorption or cause alterations in the gastric pH and/or changes in gastrointestinal motility that alter transit time.[6]

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic drug interactions

After absorption in the intestine, the portal circulation transports drugs to the liver before they are distributed by the blood flow to the other parts of the body. Many of the highly lipid-soluble drugs undergo biotransformation during the passage (first pass) through the gut wall and liver, and there are evidences that some concurrently administered drugs can have a substantial effect on the extent of first pass metabolism.

After absorption, most drugs bind to plasma proteins. The most important plasma protein is albumin and to a lesser extent, α-globulins and α-1-acid glycoprotein. Taken together, the incidence of interactions caused by competition for serum protein binding appears to be rare in dermatological practice.

Pharmacokinetic drug interactions are common in dermatology and usually involve hepatic metabolism by their influence on the cytochrome P-450 (CYP P450) isoenzyme system. The human CYP P-450 enzymes belong to three gene families, designated as P-450 1, P-450 2, and P-450 3. The P-450 3A subfamily is the most important for systemic dermatological therapy. Enzymes may be inhibited or induced. Individual drugs metabolized by a specific enzyme are identified as substrates for the isoenzyme. Considerable effort has been expended in recent years to classify drugs metabolized by this system as either an inhibitor, An inducer or a substrate of a specific isoenzyme. A drug may demonstrate complex activity within this scheme, acting as an inhibitor of one isoenzyme while serving as a substrate for another. Other enzyme systems may also influence a drug's pharmacokinetic profile. For example, a key enzyme system regulating the absorption of drugs is the P-glycoprotein system. Ketoconazole, a competitive inhibitor of CYP P-450 (CYP3A4) enzyme, binds tightly to heme iron and reduces the metabolism of endogenous substrates such as testosterone and other drugs such as cyclosporine, calcium channel blockers, and carbamazepine. On the contrary, omeprazole decreases absorption of ketoconazole and an antitubercular drug rifampicin increases the metabolism of the same. Recent evidence suggests that some interactions originally attributed to the cytochrome system may, in fact, have been the result of inhibition of this enzyme.[6,7] Griseofulvin reduces the efficacy of oral contraceptive pills by inducing the same system. Terbinafine, on the contrary, does not affect CYP 450 system and has demonstrated no significant drug interactions to date.

With the exception of the inhalation anesthetics, most drugs are excreted either in the bile or in the urine. Interference by drugs with kidney tubules fluid pH, with active transport systems, and with blood flow to the kidney can alter the excretion of other drugs.

Pharmacodynamic Interactions

Pharmacodynamic interactions are those where the effects of one drug are changed by the presence of another drug at its site of action. Sometimes the drugs directly compete for particular receptors, but often the reaction is more indirect and involves the interference with physiological mechanisms. These interactions include the following:

Additive interactions and combined toxicity

If two drugs that have the same pharmacological effect are given together, the effects can be additive. Additive effects can occur with both the main effects of the drugs as well as their side effects. Sometimes the addictive effects are solely toxic.

Antagonistic or opposing interactions

In contrast to additive interactions, there are some pairs of drugs with activities that are opposed to one another.

Interactions caused by changes in drug transport mechanisms

A number of drugs whose actions occur at adrenergic neurones can be prevented from reaching those sites of action by the presence of other drugs.

Interactions caused by disturbances in fluid and electrolyte balance

Plasma lithium levels can rise if thiazide diuretics are used because the clearance of lithium by the kidney is changed, probably as a result of the changes in sodium excretion that can accompany the use of these diuretics.[8]

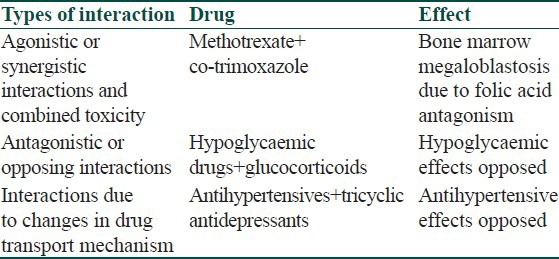

Table 3 lists some of the drug interactions that result from changes in pharmacodynamic interactions.

Table 3.

Pharmacodynamic drug interaction

Drug-food/Beverage/Herb Interactions

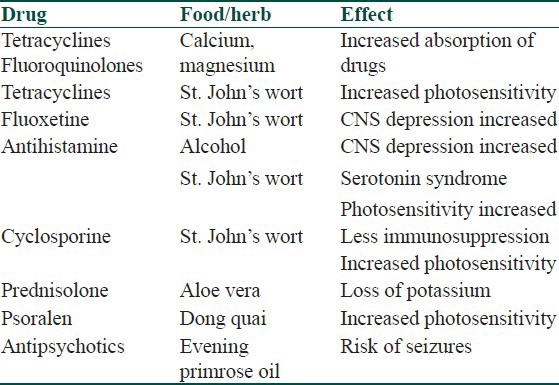

Drug-food or drug-herb interactions occur when a food, beverage, or herb taken along with a drug interacts with a drug to either increase or decrease its effect.[9] Concomitant alcohol intake along with ingestion of antihistaminics may cause CNS depression. Alcohol may also cause nausea, vomiting, flushing, dizziness, and tachycardia if administered along with cyclosporine, ketoconazole, or metronidazole (antabuse reaction). Flavonoids in grapefruit juice inhibit enzymes of CYP P450, resulting in reduced metabolism of cyclosporin and other drugs cleared by the system.[10,11] Some important drug-food/herb interactions are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Drug+food/herb interaction

Drug-disease Interactions

Drug-disease interactions occur when a drug aggravates an existing medical condition. They may occur in any age group but is more common among older people, who tend to have more diseases. Examples of drugs commonly used in dermatology causing aggravation or initiation of disease are antihistamines which can aggravate bronchial asthma, corticosteroids which can aggravate hypertension, diabetes and peptic ulcer and clindamycin (oral and topical) which may cause colitis.[12]

Topical Drug Interactions

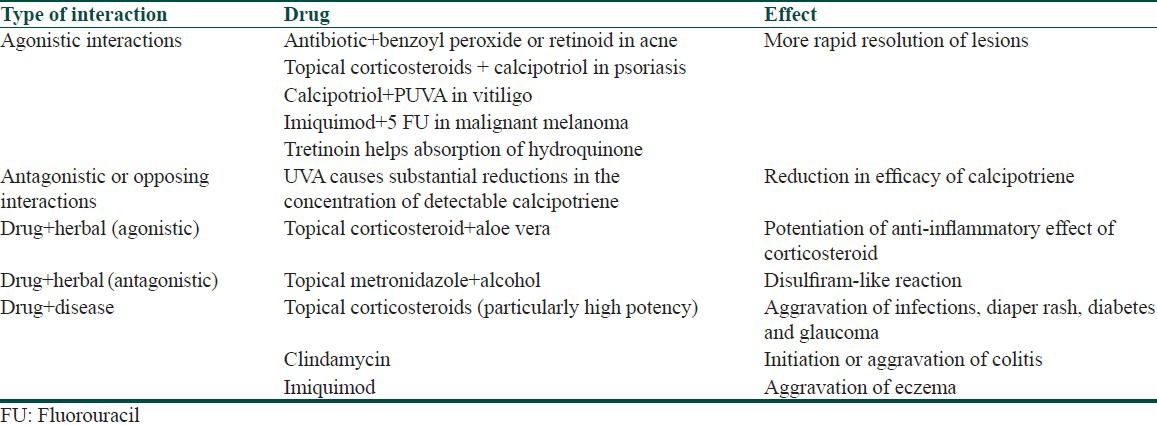

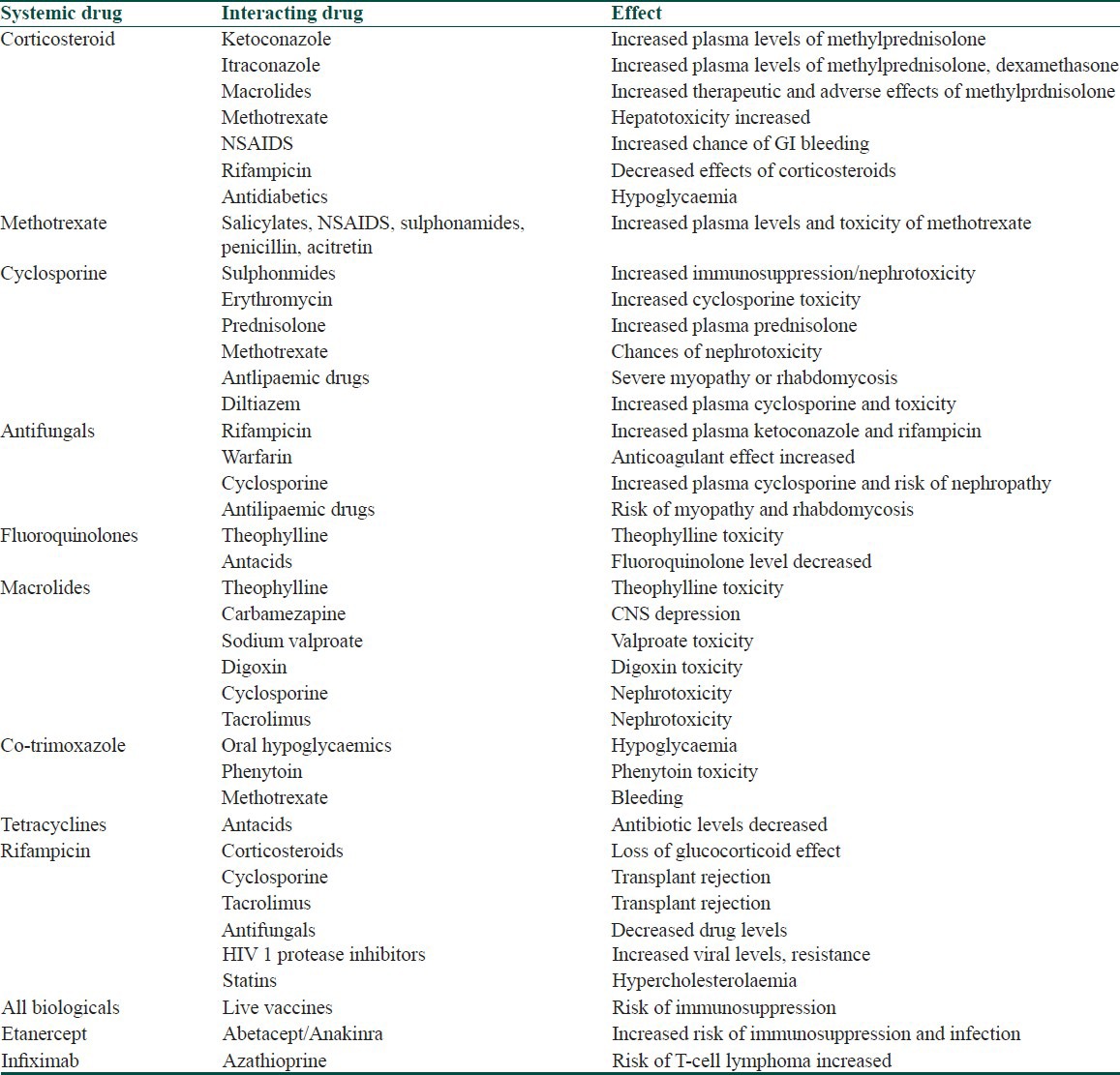

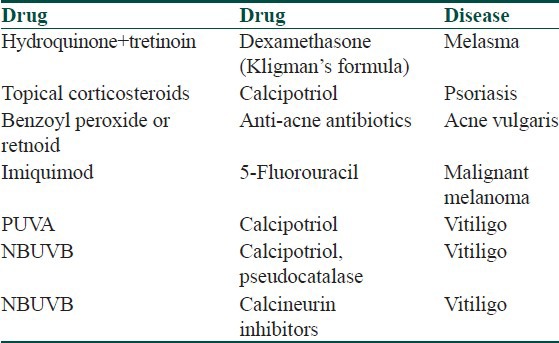

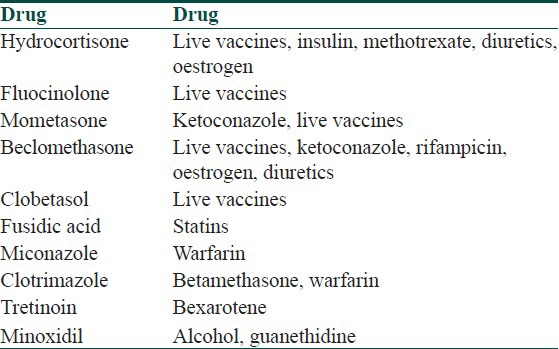

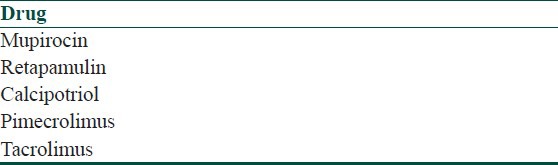

A variety of drugs applied topically to the skin or mucous membranes produce therapeutic effects localized to the site of application. They act primarily by virtue of their physical, mechanical, chemical, or biological properties. Although some part of the topical drug is absorbed, it does not have much of systemic actions unless it has been used for a long duration. Drugs applied topically may thus have interactions with other topical medications as well as systemic medications [Table 5].[13] The concept underlying the usage of different drugs and combinations in topical form is to avoid systemic side effects of systemic preparations [Table 6]. Topical drug-drug interactions may be agonistic or antagonistic.[14] A classic example of agonistic topical drug-drug interaction is the use of dexamethasone, tretinoin, and hydroquionone in Kligman's formula, wherein tretinoin helps absorption of hydroquinone and dexamethasone helps to minimize skin irritation that may be caused by tretinoin and hydroquinone [Table 7].[15] However, an antagonistic drug interaction may occur when calcipotriene is applied before PUVA causing increase in Minimum erythema dose (MED) as a result of which UVA may cause reduction in concentration of calcipotriene. Hence when used in conjunction with PUVA, calcipotriene should be applied after UVA exposure [Table 8].[16] Apart from drug-drug interactions, drug-food, drug-herb, or drug-disease interactions may also occur. Some topical drugs without significant drug interactions are mupirocin, retapamulin, calcipotriol, tacrolimus, and pimecrolimus [Table 9].

Table 5.

Topical drug interactions

Table 6.

Important drug interactions of systemic drugs commonly used in dermatology

Table 7.

Important agonistic drug interactions of commonly used topical drugs

Table 8.

Important antagonistic drug interactions of commonly used topical drugs

Table 9.

Topical medications without significant antagonistic interactions

Interaction with “Other” Drugs

A significant point which should be borne in mind by dermatologists is that drug interactions may involve drugs prescribed by practitioners of alternative medicine. Clinicians may not be aware of the pharmacology of such drugs. Before starting treatment, it is advisable to ask patients to stop all such medications to avoid unexpected and unpleasant situations.[17]

Conclusion

Drug interactions may at times be of benefit to the patients and are desirable. A majority of adverse drug interactions are not expressed clinically and may not be of serious concern. However, in some cases, the drug interactions may have serious adverse clinical expression. Hence it is important for the dermatologist to be aware of these interactions.

What is new?

1. Drug interactions are at times beneficial and helpful.

2. Most adverse drug interactions are not expressed clinically.

3. Drug interactions may involve substances prescribed by practitioners of alternative medicine – dermatologists should stop such medications before starting treatment.

4. A ready to refer check list of drug interactions related to dermatologic pharmacology can be a useful tool for clinical dermatological practice.

CME Questions

-

Drug interaction is observed in presence of

- More than one drug

- Herb

- Food

- All of them

-

Drug interactions are

- In vivo

- In vitro

- None

- Both

-

Drug interactions are.

- Unfavorable

- favorable

- None

- Both

-

All drugs have low therapeutic index except

- Cyclosprin

- Methotrexate

- Theophylline

- Peniciline

-

All are unfavorable drug interactions except

- Tetracycline and antacid

- Rifampicin and oral contraceptives

- Aspirin and warfarin

- Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid

-

All are pharmacokinetic drug interactions except

- Tetracycline and antacid

- Rifampicin and oral contraceptives

- Aspirin and warfarin

- Amoxicillin and clavulanic acid

-

None of the topical formulations show significant drug interactions except

- Mupirocin

- Retapamulin

- Calcipotriol

- Tretinoin

-

Therapeutic index means

- Lethal dose (LD50)/Effective dose (ED50)

- Lethal dose (LD50)

- Effective dose (ED50)

- Effective dose (ED50)/Lethal dose (LD50)

-

In Kligman's formula Dexamethasone helps to minimise skin irritation caused by

- Tretinoin

- Hydroquinone

- None

- Both

-

Pharmacokinetic drug interaction includes process of

- Absorption

- Metabolism

- Excretion

- All of the above

Answers

1. d, 2. d, 3. d, 4. d, 5. d, 6. d, 7. d, 8. a, 9. d, 10. d

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Wolverton SE. Drug interactions. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell D, editors. Fitzpatricks's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. New York: McGraw Hill; 2008. p. 2238. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro LE, Shear NE. Drug interactions. In: Wolverton SE, editor. Comprehensive Dermatologic Drug Therapy. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 949–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hansten PD. Drug interaction management. Pharm World Sci. 2003;25:94–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1024077018902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hendrychová T, Vlček J. Drug interactions in the elderly with diabetes mellitus. Vnitr Lek. 2012;58:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro LE, Singer MI, Shear NH. Pharmacokinetic mechanisms of drug-drug and drug-food interactions in dermatology. Curr Opin Dermatol. 1997;4:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shapiro LE, Shear NH. Drug interactions: Proteins, pumps, and P-450s. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:467–84. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2002.126823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen C, Meng Q. Prediction of cytochrome 450 mediated drug-drug interactions by three-dimensional cultured hepatocytes. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2012;12:1028–36. doi: 10.2174/138955712802762293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roos TC, Merk HF. Important drug interactions in dermatology. Drugs. 2000;59:181–92. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushra R, Aslam N, Khan AY. Food-drug interactions. Oman Med J. 2011;26:77–83. doi: 10.5001/omj.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasinu PS, Bouic PJ, Rosenkranz B. An overview of the evidence and mechanisms of herb-drug interactions. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:69. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong GA, Shear NH. Adverse drug interactions and reactions in dermatology: Current issues of clinical relevance. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen WK, Feingold DS. Adverse drug interactions clinically important for the dermatologist. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:468–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cyriac MJ. Drug interactions of some commonly used drugs in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:54–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barranco VP. Clinically significant drug interactions in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:599–612. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70125-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kligman AM, Willis I. A new formula for depigmenting human skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lebwohl M, Hecker D, Martinez J, Sapadin A, Patel B. Interactions between calcipotriene and ultraviolet light. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:93–5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchness MR. Alternative medicine and dermatology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1998;17:284–90. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(98)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]