Abstract

Context:

White lesions in the oral cavity may be benign, pre-malignant or malignant. There are no signs and symptoms which can reliably predict whether a leukoplakia will undergo malignant change or not. Many systemic conditions appear initially in the oral cavity and prompt diagnosis and management can help in minimizing disease progression and organ destruction.

Aim:

The aim of the paper was to study the clinical and histopathological patterns of white lesions in the oral cavity presented at the study setting and to study the factors associated with the histopathological patterns of the lesions.

Settings and Design:

A hospital based cross-sectional study of patients with white lesions in the oral cavity attending the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram was done.

Materials and Methods:

After taking a detailed history, microscopic examination of Potassium hydroxide smear and an oral biopsy with histopathologial examination was done.

Results:

Out of the 50 patients in the study, clinically the diagnoses made were Lichen planus (32 patients; 64%), Frictional Keratosis (4;8%), Dysplasia (2;4%), Oral Hairy Leukoplakia (1;2%), Pemphigus Vulgaris (2;4%), Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (1;2%), Oral Submucous fibrosis (3;6%) and Oral Candidiasis alone (5;10%). Out of the 45 patients who had undergone biopsy, 25 (55.6%) had Lichen planus, 9 (20%) had Frictional Keratosis and mild Dysplasia was found in 4 (8.9%) patients.

Conclusion:

The measure of agreement between the clinical and pathological diagnosis was only 32%. Older age, difficulty in opening the mouth, consumption of non-smoked tobacco, site of the lesion (gingival, floor of mouth or lingual vestibule) and presence of tenderness on the lesion were significantly associated with Dysplasia.

Keywords: Frictional Keratosis, leukoplakia, oral lichen planus, oral white lesions

Introduction

What was known?

White lesions in the oral cavity may be benign, pre-malignant or malignant. Early diagnosis can minimize progression of oral cancer.

The oral cavity is vulnerable to a limitless number of environmental insults because of its exposure to the external world.[1] Many systemic conditions appear initially in the oral cavity and prompt diagnosis and management can help in minimizing disease progression and organ destruction.

White lesions are common findings in the oral cavity. Lesions appear white in the oral cavity because the abnormal keratin can reflect the spectrum of light evenly and because of the constant bathing of the hyperkeratotic tissue in saliva, analogous to the appearance of palms and soles when immersed in water for long periods.[2,3] It is a very common practice to classify majority of white lesions as ‘Leukoplakia’. The term ‘Leukoplakia’ literally means ‘white plaque’ and it was first used by Schwimmer in 1877 to describe a white lesion of the tongue which probably represented a Syphilitic glossitis.[4] The definition of leukoplakia has changed over the time.[5,6] The WHO working group redefined leukoplakia in 2007 as “the term leukoplakia should be used to recognize white plaques of questionable risk having excluded (other) known diseases or disorders that carry no increased risk for cancer.”[7]

White lesions in the oral cavity may be benign, pre-malignant or malignant. There are no signs and symptoms which can reliably predict whether a leukoplakia will undergo malignant change or not. So a thorough history taking, physical examination and blood investigations should always be succeeded by biopsy of the white lesion to analyze the histopathological status. The aim of the paper was to study the clinical and histopathological patterns of white lesions in the oral cavity in patients presented at the study setting and to study the factors associated with the histopathological patterns of the lesions.

Materials and Methods

A hospital based cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology and Venereology, Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram from April 2007 to September 2008. All patients who presented with white lesions in the oral cavity attending the outpatient wing of the department of Dermatology and Venereology during the study period was included in the study. Those patients with age less than 10 years and those who were pregnant were excluded from the study. Other criteria for exclusion from data collection were an inability to obtain a written informed consent from the patient or an inability to interview the patient because of the presence of any medical emergencies. After obtaining a well-informed written consent, the data was collected and entered in a preset proforma.

The data collection tool included three parts. A detailed history including the patient identification details, presenting complaints, duration of the disease, personal habits including addictions, past history and family history were included in the first part of the proforma. A detailed clinical examination including general examination, examination of oral cavity and extra oral tissues was the second part. The third section of the proforma included the results of laborotary investigations including the histopathological examination report of the lesion. A direct interview technique was used to collect the history and other socio-demographic information of the patient. General examination and preliminary examination of oral cavity was done at the Department of Dermatology as an outpatient procedure. The following investigations were done in all patients-hemoglobin estimation, Venereal Disease and Research Laboratory (VDRL) and HIV Enzyme Linked Immuno Sorbent Assay (ELISA) after obtaining a well informed consent. This was followed by microscopic examination of the smear obtained from the white lesion using potassium hydroxide (patients who were found to have oral candidiasis were given antifungal therapy). The detailed oral cavity examination, examination of the lesion and specimen collection was done at the minor operation theatre of ENT Department under strict aseptic precaution. The equipment used for examination of the oral cavity included disposable hand gloves, tongue blades, gauze pads and a good light source. The patients who had undergone the procedure were examined fifteen minutes after the procedure for bleeding from the site of specimen collection or any other complication.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using the computer software, Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 10. The data was expressed in frequency and percentage. To elucidate the association and comparison between different parameters, Chi square (χ2) test was used as nonparametric test. Yates correction was done in Chi-square values in case of tables with cubicles where the expected value is less than five. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used wherever the dependent variable was quantitative. For all statistical evaluations, a two-tailed distribution was assumed and P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

Obtaining a written informed consent was one of the eligibility criteria to participate in the study. The study protocol was submitted before the institutional human ethical committee and clearance was obtained. A guideline was prepared prior to the specimen collection to minimize the pain and any complication due to the even though minor surgical procedure. The area of specimen collection was infiltrated using one percent Lignocaine for minimizing the pain due to the procedure. All these procedures were done by the principal investigator who is trained in collecting biopsies and the procedure was monitored by a qualified ENT surgeon.

Results

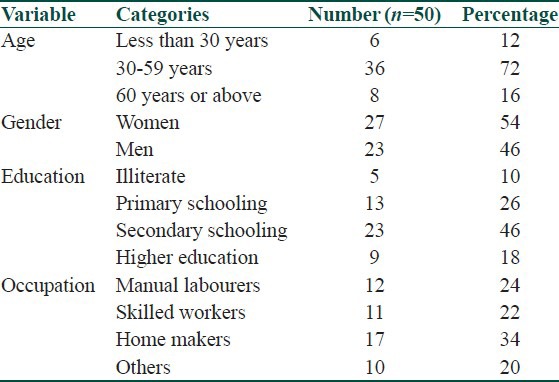

Fifty patients were included in the study after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The youngest patient was 17 years old and the oldest was of 85 years age. The mean age was 46.4 years. There were 23 males and 27 females in the study population. The socio-demographic characteristic of the study participants is given in Table 1. The duration of white lesions in oral cavity ranged from two weeks to 31 years with a mean of one year two months.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of study participants

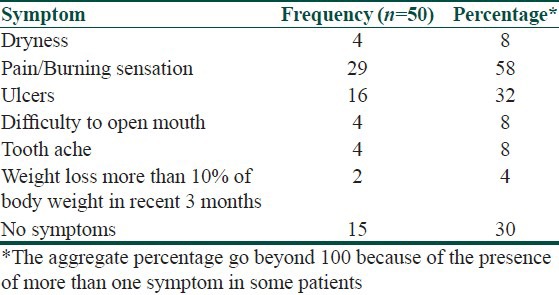

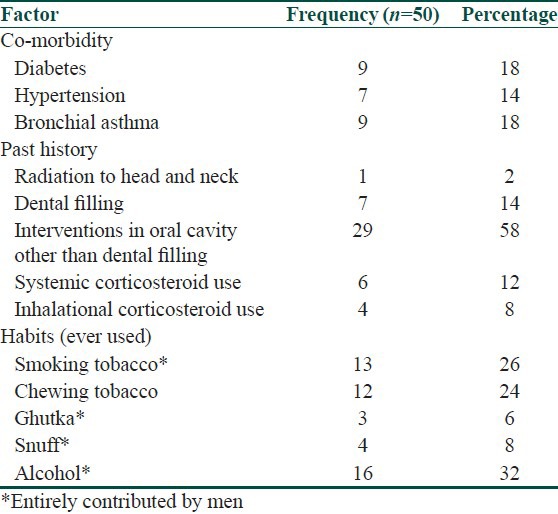

In addition to the white lesion in the oral cavity, pain or burning sensation in the oral cavity was present in 29 (58%) patients while 16 (32%) patients had ulcers in the oral cavity. 15 (30%) patients did not have any symptoms [Table 2]. Nine (18%) of them were known Diabetic and seven (14%) participants were known Hypertensive [Table 3]. 29 (58%) patients gave history of interventions in the oral cavity other than dental fillings and seven (14%) patients had history of dental fillings [Table 3]. Habit of smoking was present in 13 patients (26%) and tobacco was used in non-smoked form by 19 (38%) patients. Alcohol use was present in 16 (32%) patients [Table 3].

Table 2.

Other associated symptoms

Table 3.

Distribution of known risk factors

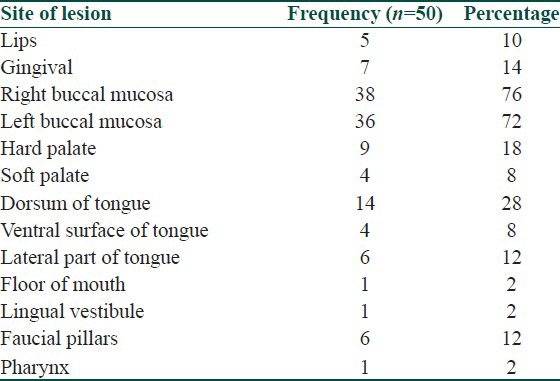

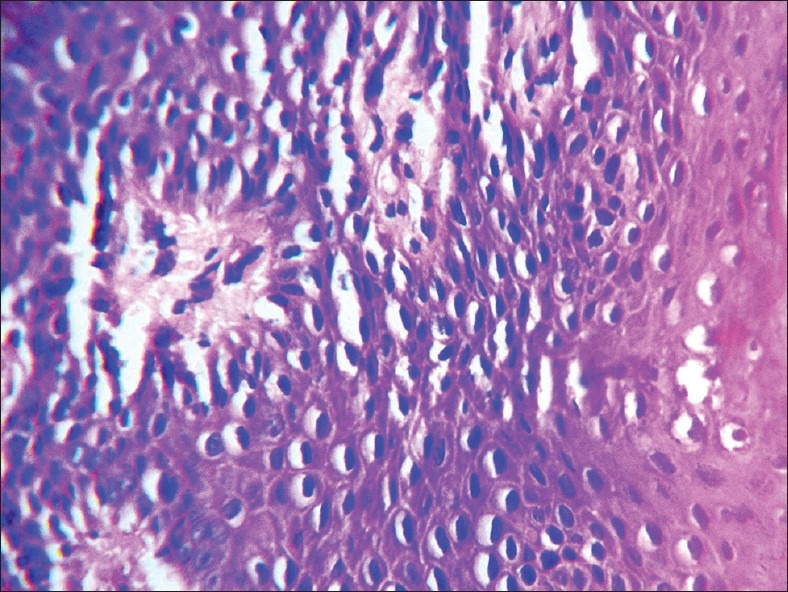

Maximum number of patients had the white lesion in the right 38 (76%) and the left 36 (72%) buccal mucosa. The next common site of involvement was the dorsum of tongue 14 (28%). The distribution of white lesions according to the anatomical location is given in Table 4. Lacy pattern of the white lesion was seen in 23 (46%) patients while 22 (44%) of them had a uniformly white lesion. The detail of the surface characteristics of the white lesion is given in Table 5. Pigmentation was the most common associated lesion followed by erythema in the oral cavity.

Table 4.

Distribution of white lesions according to the anatomical location

Table 5.

Characteristics of the white lesion

Eight (16%) patients had skin lesions suggestive of Oral Lichen Planus (OLP). Thirty (60%) patients did not have any skin lesions. VDRL testing was done in all the patients and it was reactive in one dilution in one patient who was diagnosed as Frictional keratosis clinically and histologically. HIV ELISA testing was done in 45 patients after obtaining consent. Five patients were not willing to do the test. One patient was tested positive and was diagnosed to have oral candidiasis.

The potassium hydroxide examination of smear from seven (14%) patients showed candidal hyphae. Out of this, the white lesion of five patients subsided with anti-candidal treatment. The two patients in whom the white lesion persisted were subjected to oral biopsy. One patient was clinically diagnosed to have oral erosive Lichen planus and the histopathological examination showed Keratosis, Lichenoid with mild dysplasia (Lichenoid dysplasia). The other patient was clinically diagnosed to have oral Submucous fibrosis and the oral biopsy revealed Keratosis, Not Otherwise Specified, with mild dysplasia consistent with Frictional Keratosis with dysplasia.

Clinically the diagnoses made for the white lesions were OLP (32 patients; 64%), Frictional Keratosis (4;8%), Dysplasia (2;4%), Oral Hairy Leukoplakia (1;2%), Pemphigus Vulgaris (2;4%), Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (1;2%), Oral Submucous fibrosis (3;6%), and Oral Candidiasis alone (5;10%).

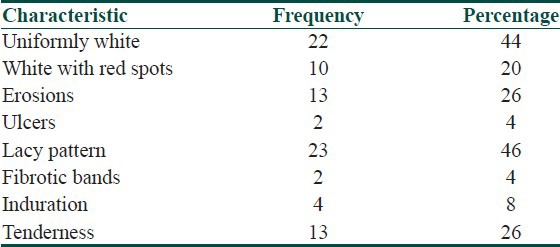

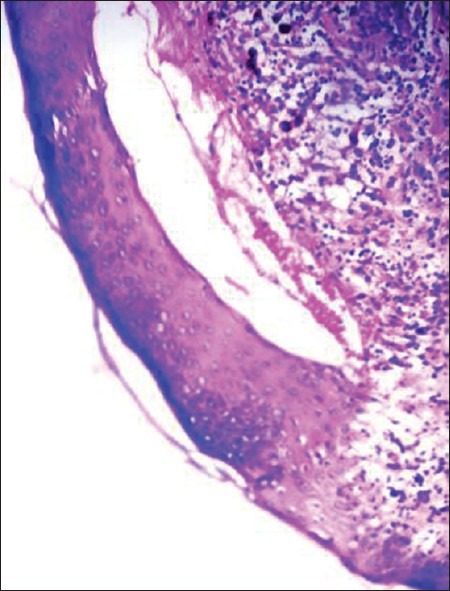

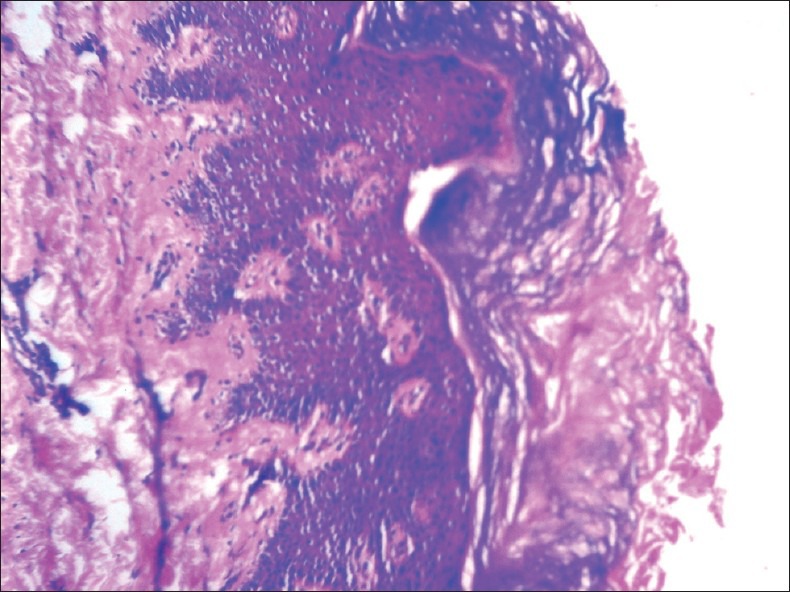

A total of 45 patients were subjected to biopsy and histopathological examination of the white lesion. Maximum number of patients 25, (55.6%) was histologically found to have Keratosis, Lichenoid, No Dysplasia which is consistent with OLP [Figure 1] and nine (20%) patients were diagnosed histopathologically as Keratosis, Not Otherwise Specified, No Dysplasia which is consistent with Frictional Keratosis [Figure 2]. Mild Dysplasia was found in four (8.9%) patients [Figure 3]. The remaining histological diagnoses were Pemphigus vulgaris (two patients), Oral Submucous fibrosis (one patient) and Vitiligo (one patient). In the case of three patients, a specific histological diagnosis could not be made.

Figure 1.

H and E stained section of Lichen planus (×10)

Figure 2.

H and E stained section of Frictional keratosis (×10)

Figure 3.

H and E stained section of dysplasia (×40)

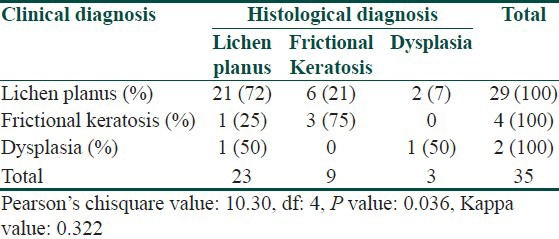

Only those patients in whom both the clinical and histological diagnoses fell under OLP, frictional keratosis or dysplasia were included in finding out the clinicopathological correlation because other diseases were very less in number [Table 6]. Out of the 29 clinical OLPs 21 (72%) turned to be OLP in histopathological analysis also. But two (7%) of them were proved to be Dysplasia. Out of the two patients clinically diagnosed as Dysplasia, one was OLP according to the histopathological analysis. Both the diagnoses were different significantly [Table 6]. The measure of agreement, Kappa value 0.322 shows that the correlation between clinical and histopathological diagnoses is as low as 32%.

Table 6.

Clinicopathological correlation

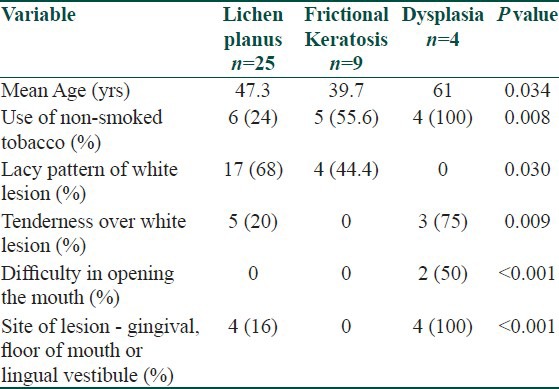

The mean age of the patients is found to be higher in patients with Dysplasia when compared with those having OLP and this difference was found to be statistically significant [Table 7]. The other factors significantly associated with Dysplasia were difficulty in opening the mouth, consumption of non-smoked tobacco, site of lesion (gingival, floor of mouth or lingual vestibule) and presence of tenderness. Lacy pattern of the white lesion was significantly associated with OLP.

Table 7.

Factors associated with the histopathological outcome

The most common symptom associated with the white lesion was pain in the case of Lichen planus and Dysplasia whereas in the case of Frictional keratosis, it was ulcer closely followed by pain. History of radiation to head and neck was documented in one of the patients and the histopathological diagnosis was turned out to be Dysplasia. Majority of patients with OLP (88%) and Frictional keratosis (80%) and half of the patients with Dysplasia did not have the habit of smoking tobacco but this was not statistically significant.

The most common site of involvement was the right buccal mucosa in Lichen planus (80%) and the left buccal mucosa in Frictional keratosis (55.56%) and Dysplasia (100%), but this is not statistically significant. Fibrotic bands were seen in one patient with Dysplasia. The statistically significant findings after cross tabulation is summarized in Table 7.

Discussion

Lesions in oral cavity are generally regarded as a strong indicator of general health of an individual.[8] It can be grouped into five categories according to the pathological process, known as the 5 Is: Inherent (congenital or hereditary, e.g. white sponge nevus), inflammation (e.g., oral lichen planus, some variants of geographic tongue), infection (e.g., oral candidiasis), iatrogenic (e.g., drug-induced lichenoid reaction, frictional hyperkeratosis) and idiopathic (e.g., oral premalignant lesion or neoplasm).[9]

In our study the single major diagnosis of oral white lesions is OLP. Shklar and Meyer suggested three criteria for diagnosis of Oral lichen planus i.e., para or hyperkeratosis, hydropic degeneration of the basal cell layer and band like chronic inflammatory infiltrate adjacent to the epithelium.[10] Hyperkeratosis was seen in 96% patients, basal cell degeneration in 88% patients and band like infiltrate adjacent to the epithelium in 80% patients in our study population. Out of the 25 patients in our study who were histopathologically diagnosed to have OLP, five (20%) patients had skin lesions of Lichen planus. According to Boyd et al., 20-34% of patients with oral Lichen planus also have concomitant cutaneous involvement which is similar to our study.[11] Although oral lichen planus without dysplasia is not considered as a pre malignant lesion, OLP can undergo transformation through genetic pathways other than that of dysplasia.[12]

A white lesion with dysplastic changes often indicate malignancy and the victim has a very high chance of mortality due to the lesion.[13] The site of lesion is also important in terms of the disease epidemiology of oral malignancies. It is often related to the behavior of people who often keep pan and other tobacco product around the bucco-alveolar complex. It has been found out that tobacco and alcohol are the potential risk factors of oral malignancy and it was estimated that 75% of oral cancer patients are regular users of tobacco or alcohol.[14] Usage of non-smoke tobacco, commonly used in the form of chewable products like pan masala was found as a significant risk factor for dysplasia by the current study also.

The lesions in some sites are often not visible both to the patient and to the physician. All the patients with Dysplasia in our study had white lesion on the left buccal mucosa. Right buccal mucosa and gingiva were involved in 75% patients, tongue in 50% patients, hard palate, lip, floor of mouth, lingual vestibule and faucial pillar in 25% patients. Floor of mouth and lingual vestibule were involved only in patients with Dysplasia. Moore and Catlin have shown that the floor of mouth and lingual vestibule, known as the ‘drainage area of mouth’, are high risk sites for dysplasia and further development of oral cancer.[15,16]

The clinical and histopathological diagnoses in our study were significantly different. This low correlation could be because of the over diagnosis of OLP made in a dermatology set up. In our study uniformly white lesion and lesion with lacy pattern was seen in 44.4% of frictional keratosis patients each. This is an important finding because lacy pattern is considered highly characteristic of OLP. Eventhough in our study we got a statistically significant association between lacy pattern and OLP, it is important to keep in mind that lacy pattern can occur in frictional keratosis also.

Out of the 45 patients in our study, 8.9% were histologically diagnosed to have dysplasia and dysplastic lesions are known to have a high probability of transforming to malignancy. Also, features which are considered typical of oral lichen planus like lacy pattern were found histologically to be dysplastic in some patients. So it is highly advisable that oral biopsy be done ideally in all white lesions or at least in those with atypical clinical features.

Despite the great strides that have been made in improving the prognosis of a number of cancers throughout the world, the prognosis for oral cancer has not experienced a similar improvement. The five-year survival in oral cancer is directly related to the stage at diagnosis, and so prevention and early detection efforts have the potential not only for decreasing the incidence, but also for improving the survival of those who develop the disease.[17]

What is new?

Lacy pattern of white lesion usually seen in oral lichen planus can occur in frictional keratosis also. Usage of non-smoked form of tobacco is also a significant risk factor for dysplasia. It is advisable to do early biopsy atleast in those oral white lesions with atypical clinical features to decrease the incidence and improve the survival of oral cancer.

Acknowledgements

Dr. N. Ashokan, Associate professor of Dermatology, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram

Dr. S. Radhakrishnan, Professor & Head of Dermatology, Governmet Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Ship JA, Phelan J, Kerr AR. Biology and pathology of the Oral Mucosa. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6th ed. Vol. 112. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. pp. 1077–91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Payne TF. Why are white lesions white? Oral Surg. 1975;40:652–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(75)90375-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong DC, Ferguson MM. A clinical approach to white patches in the mouth [internet].nzfp. 2002. Oct, pp. 334–9. Available from http://www.mzcgp.org .

- 4.Cooke BD. Leukoplakia buccalis: An enigma. Proc R Soc Med. 1975;68:337–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Axell T, Holmstrup P, Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. International seminar on oral leukoplakia and associated lesions related to tobacco habits. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1984;12:145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Axell T, Pindborg JJ, Smith CJ, van der Waal I. Oral white lesions with special reference to precancerous and tobacco-related lesions: Conclusions of an international symposium held in Uppasala, Sweden, May 18-21, 1994. International collaborative group on oral white lesions. J Oral Pathol Med. 1996;25:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;10:575–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somma F, Castagnola R, Bollino D, Marigo L. Oral inflammatory process and general health. Part 1: The focal infection and the oral inflammatory lesion. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:1085–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams PM, Poh CF, Hovan AJ, Ng S, Rosin MP. Evaluation of a suspicious oral mucosal lesion. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andreason JO. Oral lichen planus: A histologic evaluation of 97 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968;25:158–66. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(68)90194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593–619. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70241-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Michelsen C, Cheng X, Zeng T, Priddy R, Rosint MP. Molecular analysis of oral lichen planus: A premalignant Lesion? Am J Pathol. 1997;151:323–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenspan D, Jordan RC. The white lesion that kills-aneuploid dysplastic oral leukoplakia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1382–4. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laronde DM, Hislop TG, Elwood JM, Rosin MP. Oral cancer: Just the facts. J Can Dent Assoc. 2008;74:269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cawson RA. Leukoplakia and oral cancer. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62:610–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mashberg A, Garfinkel A. Early diagnosis of oral cancer: The erythroplastic lesion in high risk sites. CA Cancer J Clin. 1978;28:297–303. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.28.5.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messadi DV, Waibel JS, Mirowski GW. White lesions of oral cavity. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(02)00069-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]