Abstract

Background:

Melasma is a relatively common, acquired symmetric hypermelanosis characterized by irregular light to gray-brown macules involving sun-exposed areas. Kojic acid, with its depigmenting potential due to tyrosinase inhibition and suppression of melanogenesis, has become a vital component of the dermatologists’ armamentarium against melasma.

Aim:

To study and compare the efficacy of kojic acid 1% alone, vis-a-vis its separate combinations with 2% hydroquinone or 0.1% betamethasone valerate and a combination of all these three agents with respect to the duration of symptoms and level of pigmentation in the therapy of melasma.

Materials and Methods:

Eighty patients from a single tertiary care center objectively assessed by calculating the melasma area severity index (MASI) and randomized (simple randomization) into four parallel groups (A, B, C, and D) of 20 each were prescribed once daily local application at night, (participants blinded regarding the difference in identity of interventions), as follows:

Group A – kojic acid 1% cream.

Group B – kojic acid 1% and hydroquinone 2% cream.

Group C – kojic acid 1% and betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream.

Group D – kojic acid 1%, hydroquinone 2%, and betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream.

Strict photoprotection and use of a SPF 15 sunscreen was advised during the day. Patients were evaluated every 2 weeks and a fall in MASI score was calculated at the end of the study period of 12 weeks by the same investigator.

Results:

The response was compared according to percentage decrease in MASI score. Efficacy was evaluated among the groups at the end of 3 months using bivariate analysis and calculated by using the paired ‘t’ test. The clinical efficacy of group B was the highest followed closely by group D and group A, that of group C being the lowest.

Conclusion:

Kojic acid in synergy with hydroquinone is a superior depigmenting agent as compared with other combinations.

Keywords: Kojic acid, melasma, MASI score

Introduction

What was known?

Melasma, a multifactorial patterned facial hyperpigmentation of grave psychological impact, has been subjected to a range of depigmenting agents consisting of heavy metal salts to nutraceuticals, with rebound pigmentation as a rule. Although kojic acid has been in use for over a decade, not many studies have been published regarding its use in the Indian skin.

Melasma is a common, insidious, asymptomatic, symmetric, and patterned hyperpigmentation with predilection for involvement of the cheeks, forehead, upper lip, nose, and forearm occurring as irregularly shaped, but often distinctly defined, blotches of light to dark brown pigmentation in the fair skinned or dark ones in dark skinned individuals.[1,2] It may be idiopathic, may appear during pregnancy[3] or be associated with use of oral contraceptives.[3,4,5,6] Affecting all the races, it is most prevalent in the Hispanics and Asians of skin types IV, V, and VI with centrofacial, malar, and mandibular distribution.[3,6,7,8] Its location and occurrence in the nonpregnant women and even in men suggest some role of ultraviolet (UV) radiation.[8] Out of the three therapeutic modalities of hypopigmenting agents, chemical peels and lasers, latter is the most recent and hydroquinone, the oldest. The use of most of them is limited due to adverse effects and rebound hyperpigmentation. The initial impressive results with the use of kojic acid[3] in the treatment of melasma prompted numerous clinical trials worldwide including the present study, comparing the efficacy and safety of kojic acid alone and its combinations (hydroquinone, betamethasone valerate) in Indian skin types, there being only a few published studies in the latter skin type.

Materials and Methods

This simple randomized (computer generated random numbers), single center, single blinded (patients blinded and investigator aware of the intervention), parallel group comparative study comprised of 80 healthy adults of either sex clinically diagnosed as melasma attending the dermatology outpatient department of a tertiary care teaching hospital in western Maharashtra. Pregnant and lactating mothers, patients with severe actinic damage, on drugs causing or aggravating pigmentation, those with underlying systemic or dermatological conditions and with known allergy to any of the ingredients were excluded. Data recorded included age, sex, duration of symptoms, nature of progression, relationship with pregnancy, lactation, intake of oral contraceptive pills, history of previous treatments, and family history of melasma. The patients were instructed not to apply any cosmetics during the course of the study.

Assessment including by Wood's light was undertaken to discern the pattern of melasma (malar, centrofacial, and mandibular) and its level of pigmentation (epidermal, dermal, and mixed).

Severity of melasma was quantified by calculating the melasma area severity index (MASI).[9] Four areas of the face were evaluated for use in calculation as f – forehead, mr – right malar, ml – left malar, c – chin; corresponding to 30%, 30%, 30%, and 10% of the total face, respectively. The melasma in each of these areas was given a numerical value according to the percentage of area involved as follows:

0 = No involvement, 1 = Less than 10%, 2 = 10–29%, 3 = 30–49%, 4 = 50–69%, 5 = 70–89%, 6 = 90–100%.

The severity of melasma was based on darkness (D), as compared with the normal skin, and homogeneity (H) of pigmentation, each assessed on a scale of 0 through 4 as follows: Darkness (D) - 0 = absent, 1 = slight, 2 = mild, 3 = marked, 4 = severe

Homogeneity (H) – 0 = minimal, 1 = slight, 2 = mild, 3 = marked, 4 = maximum.

To calculate MASI score, the sum of severity rating for darkness (D) and homogeneity (H) was multiplied by numerical value of the areas (A) involved and various percentages of the four facial areas. These values were added to obtain MASI score. Therefore,

MASI = 0.3 (Df+ Hf) Af + 0.3 (Dmr + Hmr) Amr + 0.3 (Dml + Hml) Aml + 0.1 (Dc + Hc) Ac.

MASI was scored at the baseline, at an interval of 4 weeks and at the end of the study, that is, 3 months. A written and informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Patients randomized by simple randomization into four parallel groups, each of 20 patients, were prescribed once nightly topical application (group A – kojic acid 1% cream, group B – kojic acid 1% and hydroquinone 2% cream, group C – kojic acid 1% and betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream, and group D – kojic acid 1%, hydroquinone 2%, and betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream) and were provided with a sunscreen of SPF15 for application during the day. Participants were unaware of the difference in the interventions among the four groups (single blinded).

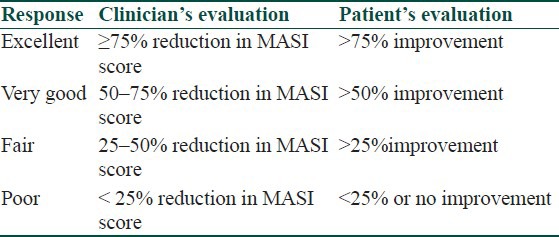

Patients were followed up and photographs taken at the end of 4, 8, and 12 weeks. Efficacy was evaluated by calculating the percentage reduction in MASI score among the groups at the end of 3 months by using bivariate analysis, that is, average and standard deviation. The efficacy of drugs was calculated by using the paired ‘t’ test. Therapeutic response was also compared with regard to duration of symptoms and level of pigmentation. The responses rated by the physician and the patients were recorded as tabulated in [Table 1] by global assessment scale.[10]

Table 1.

Global assessment scale for melasma

Safety evaluation was carried out by recording the adverse effects such as burning, erythema, and itching on a scoring scale of 0–3 as 0=none, 1 = mild, 2= moderate, 3 = severe.

The study protocol was approved by the research review board of the medical college and had no financial support from any agency.

Results

The age of the 80 patients in this study varied between 18 and 58 years; 33 (41.25%) cases in the range of 30–39 years formed the largest group and 8 (10%) between 50 and 59 years, the smallest. There were 67 females and 13 males, that is, F:M of approximately 5:1.

The duration of pigmentation ranged between 1.5 months and 23 years. In 8 (10%) patients, it was less than a year, in 42 (52.5%) between 1 and 5 years, and in the remainder 30 (37.5%), more than 5 years.

The patterns of melasma seen were centrofacial in 48 (60%) and malar in 32 (40%), there being no case of mandibular pattern. The levels of pigmentation detected on Wood's light in descending order of frequency were: epidermal [48 (60%)], mixed [26 (32.5%)], and dermal [6 (7.5%)].

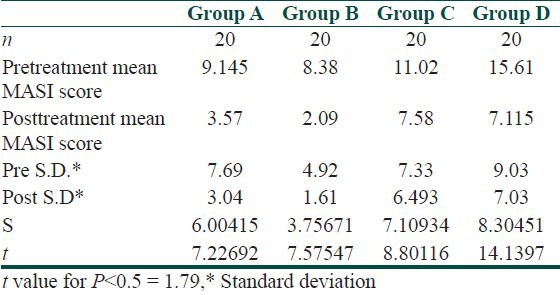

Evaluation of response of the four groups according to change in MASI score is shown in [Table 2].

Table 2.

Evaluation of response of the four treatment groups according to the change in MASI score

Thus there is significant difference between the pre- and posttreatment MASI scores among all the four groups.

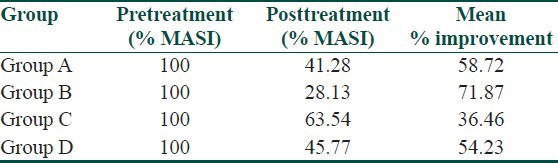

Response evaluation according to percentage improvement in the mean pre- and posttreatment scores in all the four groups are shown in [Table 3]

Table 3.

Mean percentage improvement in posttreatment MASI score

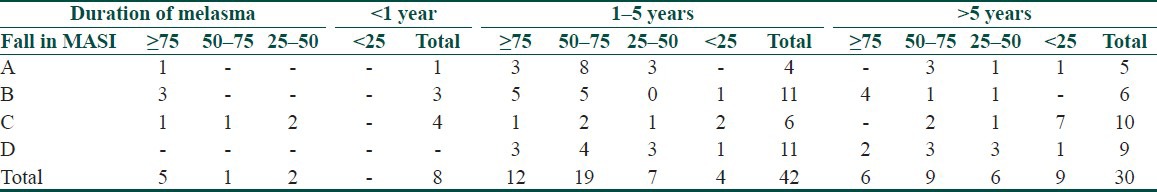

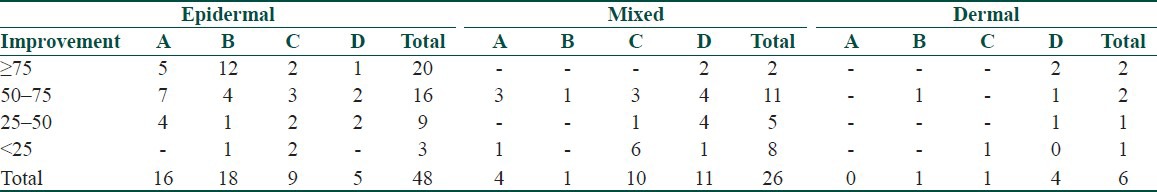

Clinical response in relation to the duration and level of pigmentation are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Clinical response in relation to duration of melasma

Table 5.

Group wise clinical response in relation to level of pigmentation

Discussion

Ever since its introduction (by Kligman and Willis in 1975), the “triple” combination (consisting of hydroquinone 5%, tretinoin 0.1%, and dexamethsone 0.1%)[11] and its various modifications remain the most frequently prescribed topical agents for melasma, the most common of the hyperpigmentary conditions. However, unacceptable side effects of these chemical agents have recently shifted the focus to the traditionally used indigenous agents like kojic acid, an ingredient of Japanese food.

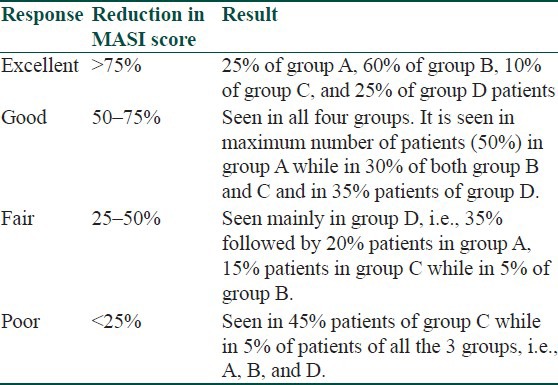

The percentage decrease in MASI score among the four groups in our study as tabulated in [Table 6] showed the highest reduction (60%, excellent reduction) in group B Figure 1 followed by group A [Figure 2] and D [Figure 3] (25%, excellent reduction) and least (10%, excellent reduction) in group C [Figure 4].

Table 6.

Theraperutic response according to percentage (%) decrease in MASI score

Figure 1.

Pre- and posttreatment response, group B

Figure 2.

Pre- and posttreatment response, group A

Figure 3.

Pre- and posttreatment response, group D

Figure 4.

Pre- and posttreatment response, group C

As regard to the duration, the clinical response was inversely proportional to the duration of melasma in group A, proportional in groups B and D, but did not vary in group C. Overall cases of melasma of less than 5 years duration had a better clinical response while response became poorer as the duration increased. The best clinical response was seen in the epidermal followed by the mixed and the dermal types. However, unreliability of Wood's light as regards this distinction of depth of pigmentation in Indian skin types IV and V is a limitation in our study patients.

With group A, that is, kojic acid 1% cream, the mean percentage improvement in MASI score was observed to be 58.72%.

With group B, that is, kojic acid 1% and hydroquinone 2%, the mean percentage improvement in MASI score was 71.87%, with excellent response in 60%, good in 30% and fair and poor in 5% each. The results of this group correlate with the following studies:

A study by Fulton et al.[12] of 39 patients who applied hydroquinone 4% or 2% kojic acid on either cheek, revealed equal response in 20 (51%), to hydroquinone and kojic acid.

In the study by Lim et al.,[13] 60% cases applying a hydroquinone 2% and kojic acid 2% gel had a better response than those applying hydroquinone only, 47.5% of whom responded.

Group C (kojic acid 1% and betamethasone valerate 0.1% cream), showed the lowest (36.46%) improvement. There are no reports in literature studying the efficacy of kojic acid in combination with a topical corticosteroid.

With group D (kojic acid 1%, hydroquinone 2%, and betamethasone valerate 0.1% in a cream base), the mean percentage improvement in MASI score was 54.03%, with 25% showing excellent improvement, good response in 35%, fair 35%, and poor in 5%. This group proved to be third in efficacy. The lesser efficacy of these combinations (groups C and D) whether betamethasone induced or contributed by unreliable distinction between epidermal and dermal pigmentation by Wood's light in type IV and V Indian skin or even may be by an imbalance in stratification as per duration of melasma, could not be explained and needs further investigation.

Only a solitary patient of group A and two patients of group B complained of burning sensation. None in our study complained of any dermatitic reaction or contact allergy to kojic acid unlike that reported in the study by Nagakawa et al.[2] One patient in group D developed acneiform eruptions. Although betamethasone valerate did not improve the efficacy of the combination, it was helpful in decreasing the irritation caused by hydroquinone and kojic acid.

The percentage reduction in MASI score incorporating clinical components namely darkness (D), homogeneity (H), and area (A) correlated well with the subjective analysis of the therapeutic response by the patients. Hence MASI score can be useful to compare various therapeutic regimens of melasma.

In conclusion, kojic acid along with hydroquinone is a superior depigmenting agent as compared with other three combinations in our study. Its combination with hydroquinone is synergistic. However, larger studies overcoming above mentioned limitations are required to obtain more conclusive data.

What is new?

Kojic acid and hydroquinone combination is synergistic and has a better depigmenting effect than the other three groups in our study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Grimes PE. Melasma: Etiologic and Therapeutic considerations. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1453–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.131.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagakawa M, Kawal K, Kawai K. Contact allergy to Kojic acid in skin care products. Contact Dermatitis. 1995;32:9–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1995.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandyopadhyay D. Topical treatment of melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54:303–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.57602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Achar A, Rathi SK. Melasma: A clinico-epidemiological study of 312 cases. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:380–2. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.84722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godse KV, Zawar V. Mometasone menace in melasma. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:324–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.97686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez NP, Pathak MA, Sato S, Fitzpatrick TB, Sanchez JL, Mihm MC., Jr Melasma: A clinical, light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunofluorescence study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4:698–710. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)70071-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drug. JAMA. 1967;199:601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB, Kraus EW. Usefulness of retinoic acid in the treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:894–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kimbrough-Green CK, Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, Hamilton TA, Bulengo-Ransby SM, Ellis CN, et al. Topical retinoic acid (tretinoin) for melasma in black patients. A vehicle-controlled clinical trial. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:727–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffiths CE, Finkel LJ, Ditre CM, Hamilton TA, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ. Topical tretinoin (retinoic acid) improves melasma: A vehicle-controlled, clinical trial. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:415–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kligman AM, Willis I. A New formula for Depigmenting Human Skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia A, Fulton JE., Jr The combination of glycolic acid and hydroquinone, kojic acid for the treatment of melasma and related conditions. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:443–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lim JT. Treatment of melasma using kojic acid in a gel containing hyroquinone and glycolic acid. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:282–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]