Abstract

Background:

Syphilis is caused by a spirochete Treponema pallidum. Invasion of the central nervous system (CNS) by T. pallidum may appear early during the course of disease. The diagnosis of confirmed neurosyphilis is based on the reactive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Recent studies indicated that serum RPR ≥ 1:32 are associated with higher risk of reactivity of CSF VDRL.

Aims:

The main aim of the current study was to assess cerebrospinal fluid serological and biochemical abnormalities in HIV negative subjects with secondary and early latent syphilis and serum VDRL ≥ 1:32.

Materials and Methods:

Clinical and laboratory data of 33 HIV-negative patients with secondary and early latent syphilis, with the serum VDRL titer ≥ 1:32, who underwent a lumbar puncture and were treated in Department of Dermatology at Jagiellonian University School of Medicine in Cracow, were collected.

Results:

Clinical examination revealed no symptoms of CNS involvement in all patients. 18% (n = 6) of patients met the criteria of confirmed neurosyphilis (reactive CSF-VDRL). In 14 (42%) patients CSF WBC count ≥ 5/ul was found, and in 13 (39%) subjects there was elevated CSF protein concentration (≥ 45 mg/dL). 10 patients had CSF WBC count ≥ 5/ul and/or elevated CSF protein concentration (≥ 45 mg/dL) but CSF-VDRL was not reactive.

Conclusions:

Indications for CSF examination in HIV-negative patients with early syphilis are the subject of discussion. It seems that all patients with syphilis and with CSF abnormalities (reactive serological tests, elevated CSF WBC count, elevated protein concentration) should be treated according to protocols for neurosyphilis. But there is a need for identification of biomarkes in order to identify a group of patients with syphilis, in whom risk of such abnormalities is high.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid examination, early syphilis, neurosyphilis

Introduction

What was known?

Neurosypilis may occur at any stage of syphilis infection, including an early phase of the diseae. When not treated or inaproperly treated neurosyphils may progress and cause neurological symptoms. Still the matter of debate, remains which syphilitic patients should undergo CSF examination. Recent study has shown that patients with syphilis and serum RPR => 1:32 are at higher risk of early neurosyphilis.

Syphilis is caused by a spirochete Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum, which cannot be cultured in vitro. Diagnosis of syphilis is based on clinical presentation and both reactive serum non-treponemal (i.e., VDRL - Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, RPR - Rapid plasma reagin) and treponemal tests (i.e., FTA - Fluorescent treponemal antibody test, TPHA - Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay). Invasion of the central nervous system (CNS) by T. pallidum appears early during the course of disease, and is defined by increased CSF WBC cerebrospinal fluid white blood cell (CSF WBC) count or elevated protein concentration and reactive VDRL in CSF.[1] CNS invasion by T. pallidum in the course of early stages of syphilis is usually asymptomatic.[2] Untreated or improperly treated asymptomatic neurosyphilis may develop to symptomatic phase, and manifest, for example as cognitive impairment, personality change, general paresis[3] or epilepsy.[4] The CNS involvement in the course of syphilis, regardless of stage of the disease requires different (i.e., intravenous) and longer treatment.[5] CSF examination in immunocompetent patients with syphilis has recently been the subject of discussion. Recent study indicated that the titer of serum RPR ≥ 1:32, regardless of the stage of syphilis, in HIV-negative patients is associated with slightly more than 10-fold increased risk of reactive CSF VDRL-laboratory marker of neurosyphilis.[6]

Materials and Methods

Clinical and laboratory data of 33 HIV-negative patients with secondary and early latent syphilis, with the serum VDRL titer ≥ 1:32, who underwent lumbar puncture and were treated in Department of Dermatology, Jagiellonian University School of Medicine in Cracow, were collected. In all patients syphilis was diagnosed at the basis of blood serology (VDRL, FTA, TPHA) and clinical manifestation. Prior to the study entry none of the patients was treated for syphilis. Everyone also denied receiving antibiotics in the 12 months period prior to admission to the hospital.

Results

The median age in the analyzed group was 32 years, the youngest patient was 20 and the oldest 55. 5 patients (15%) were with no skin and mucosal lesions, or lymphadenopathy. 48% of patients (n = 16) presented spotted rash on the trunk, 30% (n = 10) maculopapular rash on the hands and feet. In 3 (9%) patients were observed alopecia and in one vitiligo. In 12 (36%) cases serum VDRL was 1:32, 16 (48%) 1:64, and in 5 (15%) 1:128.

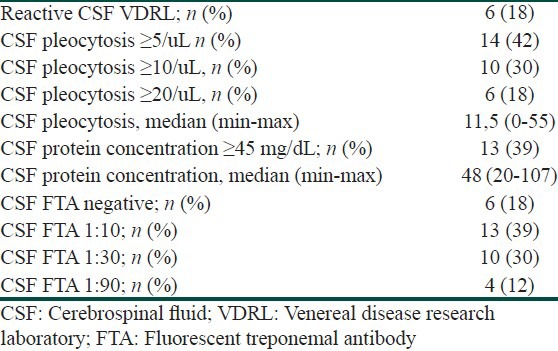

All patients were without any clinical symptoms of CNS involvement. Table 1 presents the results of cerebrospinal fluid examination in the analyzed group of subjects. 18% (n = 6) of patients met the criteria of confirmed neurosyphilis (reactive CSF-VDRL). Of these 6, 5 subjects had both reactive CSF VDRL test results and CSF WBC count ≥ 5 cells/uL, and 4 had reactive CSF VDRL test result, CSF WBC ≥ 5 cells/uL and CSF protein concentration ≥ 45 mg/dL. Only one patient with reactive VDRL test result had WBC count 4 cell/uL but protein concentration was 51 mg/dL. Furthermore, only one patient from the reactive CSF VDRL group had CSF protein concentration in normal range (35 mg/dL), but the CSF WBC count in this case was 51/uL. In 10 subjects (30%) there were biochemical abnormalities in CSF detected (WBC count ≥ 5/ul and/or elevated protein concentration ≥ 45 mg/dL), but CSF-VDRL test was not reactive. All subjects with reactive CSF VDRL test result had reactive CSF FTA as well. In the group of 27 patients with non-reactive CSF VDRL test 20 had reactive CSF FTA. Because all these patients were with no clinical symptoms of CNS disease, the diagnosis of presumptive neurosyphilis was not possible. All patients in whom we have detected any CSF abnormalities, were treated with a regimen recommended for neurosyphilis (i.e., intravenous crystalline penicillin).

Table 1.

Results of the CSF examination

Discussion

Data available from the literature indicate that CNS invasion by T. pallidum in the course of syphilis may occur in up to 100% of the patients. In about 80% of them T. pallidum is cleared from CNS by immune system and in 13,5-20% cases, asyptomatic neurosyphilis develops.[7] It is estimated that in the whole group of patients with asymptomatic neurosyphilis approximately 35% develop symptomatic disease (symptomatic neurosyphilis). The study of preantibiotic era showed that in these patients the risk of developing symptomatic neurosyphilis is the higher, the more abnormalities are found in the examination of CSF.[8]

There is no gold standard test to diagnose neurosyphilis. The centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) has established the two categories: “Confirmed” neurosyphilis and “presumptive” neurosyphilis. The former is defined as any stage of syphilis and a reactive CSF VDRL. Presumptive neurosyphilis is defined as any stage of syphilis,[2] a nonreactive CSF VDRL, CSF pleocytosis or elevated protein, and clinical signs or symptoms consistent with syphilis without an alternate diagnosis to account for these.[9] A reactive CSF-VDRL is considered diagnostic for neurosyphilis, but this test may be negative in as many as 70% of individuals with neurosyphilis, and the diagnosis in such cases may be based solely on the CSF WBC count.[10] The CSF WBC count in syphilis is lymphocyte-predominant. A cutoff of greater than or equal to 5 cells/uL has been the standard in HIV-negative subjects.[7] Several studies have evaluated the performance measures of detecting intrathecal production of T. pallidum specific IgG in the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, but data have been inconsistent, so this method is not used in the routine diagnostics.[11,12,13]

First-line therapy of the asymptomatic and symptomatic neurosyphilis is intravenous crystalline penicillin. Until now the efficacy of alternative methods of therapy (oral antibiotics, intramuscular penicillin) in treatment of neurosyphilis has not been sufficient proven in randomized trials. However, in vitro studies revealed that these antimicrobials do not reach treponemocidal level in CSF.[14]

According to data from the preantibiotic era routine examining of CSF in each patient with syphilis is unnecessary, and nowadays, mostly for economic reasons, impossible. Still, there is a need for selecting a group of patients with syphilis who are saddled with an increased risk of abnormalities in CSF examination (i.e., elevated CSF WBC count, elevated protein concentration or reactive serologic test results).

Recent studies of Marra et al.,[6] showed that, serum RPR ≥ 1:32, in HIV-uninfected patients with syphilis, regardless the stage of disease, may 10-fold increase the risk of neurosyphilis. Marra et al., defined the neurosyphilis as a reactive CSF VDRL or WBC count > 20 cells/uL. In the current study, we presented the abnormalities in the CSF examination in patients with secondary and early latent syphilis with serum VDRL ≥ 1:32. According to the CDC, 18% subjects in our group met the criteria for asymptomatic neurosyphilis. Using less stringent criteria proposed by Marra et al., (reactive CSF VDRL or CSF WBC count > 20 cells/uL), the percentage was 21% (data not shown). We have also observed a quite large percentage of patients with positive CSF treponemal tests. However, most experts consider that the treponemal tests may serve to exclude the diagnosis of neurosyphilis, but are not suitable for its confirmation.[15]

In 18 patients (54%) there were found any abnormalities in the CSF examination (reactive VDRL, CSF WBC count ≥ 5/uL or protein concentration ≥ 45 mg/dL). So far, the clinical relevance of these observations remains unclear. Due to discrepancies in definition of the neurosyphilis, all patients diagnosed with any abnormalites in the CSF examination were treated as neurosyphilis.

As mentioned above, the penetration of T. pallidum to the nervous system at a very early stage of infection (primary syphilis) is common and probably not associated with clinical consequences. It seems that the immune response in the secondary syphilis is the most important factor responsible for development of asymptomatic or/and symptomatic neurosyphilis. But further studies on biomarkers of CNS involvement in the course of syphilis are needed, in order to identify groups of patients in whom the risk of neurosyphilis is high, and thus, who should undergo further tests (i.e., CSF examination). There is also a need for studies on therapeutic strategies in patients with syphilis and only biochemical abnormalities in CSF.

What is new?

Almost one fifth of patients with early syphilis and serum VDRL => 1:32 fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for neurosyphilis. Almost one half had some CSF abnormalities. Unfortunately, clinical relevance of these observations remains unclear. Furhter studies on biomarkers of neurosyphilis are needed.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Lukehart SA, Hook EW, 3rd, Baker-Zander SA, Collier AC, Critchlow CW, Handsfield HH. Invasion of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum: Implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:855–62. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-11-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosc Rep. 2004;4:4340. doi: 10.1007/s11910-004-0065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helsen G. General paresis of the insane: A case with MR imaging. Acta Neurol Belg. 2011;1:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajjaj I, Kissani N. Status epilepticus revealing syphilitic meningoencephalitis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2010;3:263–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marra CM, Maxwell CL, Smith SL, Lukehart SA, Rompalo AM, Eaton M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis: Association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:369–76. doi: 10.1086/381227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghanem KG. Neurosyphilis: A historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16:e157–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore JE, Hopkins HH. Asymptomatic neurosyphilis VI: The prognosis of early and late asymptomatic neurosyphilis. J Am Med Assoc. 1930;95:1637–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wharton M, Chorba TL, Vogt RL, Morse DL, Buehler JW. Case definition for public health surveillance. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1990;39:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooshman H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphilis: Study of 241 patients. J Am Med Assoc. 1972;219:726–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.219.6.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vartdal F, Vandvik B, Michaelsen TE, Loe K, Norrby E. Neurosyphilis: Intrathecal synthesis of oligoclonal antibodies to Treponema pallidum. Ann Neurol. 1982;11:35–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prange HW, Moskophidis M, Schipper HI, Muller F. Relationship between neurological features and intrathecal synthesis of IgG antibodies to Treponema pallidum in untreated and treated human neurosyphilis. J Neurol. 1983;230:241–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00313700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moskophidis M, Peters S. Comparison of intrathecal synthesis of Treponema pallidum-specific IgG antibodies and polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1996;283:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parkers R, Renton A, Mekens A, Lauhamm-Josten U. Review of current evidence and comparison for effective syphilis treatment in Europe. Int J STD AIDS. 2904;15:73–88. doi: 10.1258/095646204322764253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffe HW, Larsen SA, Peters M, Jove DF, Lopez B, Schroeter AL. Tests for treponemal antibody in CSF. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:252–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]