Abstract

Alveolar epithelial cells (AECs) maintain the pulmonary blood-gas barrier integrity with gasketlike intercellular tight junctions (TJ) that are anchored internally to the actin cytoskeleton. We have previously shown that AEC monolayers stretched cyclically and equibiaxially undergo rapid magnitude- and frequency-dependent actin cytoskeletal remodeling to form perijunctional actin rings (PJARs). In this work, we show that even 10 min of stretch induced increases in the phosphorylation of Akt and LIM kinase (LIMK) and decreases in cofilin phosphorylation, suggesting that the Rac1/Akt pathway is involved in these stretch-mediated changes. We confirmed that Rac1 inhibitors wortmannin or EHT-1864 decrease stretch-stimulated Akt and LIMK phosphorylation and that Rac1 agonists PIP3 or PDGF increase phosphorylation of these proteins in unstretched cells. We also confirmed that Rac1 pathway inhibition during stretch modulated stretch-induced changes in occludin content and monolayer permeability, actin remodeling and PJAR formation, and cell death. As further validation, overexpression of Rac GTPase-activating protein β2-chimerin also preserved monolayer barrier properties in stretched monolayers. In summary, our data suggest that constitutive activity of Rac1, which is necessary for stretch-induced activation of the Rac1 downstream proteins, mediates stretch-induced increases in permeability and PJAR formation.

Keywords: lung injury, lung permeability, mechanical ventilation, Rac1 activity, tight junction

high magnitudes of cyclic stretch, analogous to pathological mechanical ventilation volumes, have been linked to formation of perijunctional F-actin rings (PJARs) and increased monolayer permeability in rat type I-like pulmonary alveolar epithelial cells (AECs; 15, 24). However, the underlying mechanistic pathways involved in stretch-induced PJAR formation and increased monolayer permeability in these cells are still vague. The Rho family of small GTPases, comprising Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, has been shown to play a major role in the regulation of epithelial structure and function and, more specifically, in the regulation of F-actin dynamics (32). The role of the Rho pathway has been implicated in regulation of tight junction (TJ) proteins and paracellular permeability in unstretched (9) and stretched cells (20, 50, 64). Although others show a dramatic increase in Rac1-GTP in stretched endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (45, 47) with subsequent increase in Akt phosphorylation (3, 22, 46) or a downregulation of Akt (52), there is a paucity of studies in stretched alveolar epithelial cells.

The Rac1 signaling pathway can be modulated through a number of upstream proteins, including phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K; 56). Furthermore, Rac interacts with Akt (35) and influences numerous downstream proteins such as LIM kinase (LIMK) (27) and the actin turnover mediator cofilin (5), which is activated by the phosphatase slingshot-1 (SSH1L; 43). In nonpulmonary cells, Rac1/Akt pathways have been shown to alter TJ protein distribution and bonds with actin (9), activate cofilin (17), and reorganize the F-actin cytoskeleton, resulting in increases in permeability (12, 48, 69). As confirmation, silencing PI3K improved the barrier function in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (12). Furthermore, others have shown that Rac1 promotes cell survival via Akt (11) and that Rac1 agonist PDGF improves cell motility (16, 35, 42).

To address the paucity of data regarding the role of Rac1 pathway signaling with stretch in pulmonary cells, we investigated the effect of cyclic equibiaxial stretch on activation of the Rac1 downstream proteins Akt, LIMK, and cofilin, and the Rac1 pathway-specific effects on TJ-mediated paracellular permeability, PJAR formation, and cell death and confirmed causality at multiple points in the signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of primary rat type I-like alveolar epithelial cells.

Alveolar type II cells were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously (24). The animal protocols used in this study were reviewed and approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Cells were seeded at a density of 1.0 million cells/cm2 onto fibronectin-coated (10 μg/cm2, Invitrogen) flexible Silastic membranes (Specialty Manufacturing, Saginaw, MI) in custom-designed wells (61) and were cultured for 4–5 days at 37°C, 5% CO2 in MEM with 10% FBS, after which the cells had adopted alveolar type I-like features (8, 21).

Experimental design.

Prior to stretch experiment, the monolayers were serum deprived in DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 20 mM HEPES (Sigma) for 2 h. The AEC monolayers were then stretched cyclically and equibiaxially with a stretch device that was previously designed in our laboratory (61), at 0.25 Hz and across a range of physiologically relevant magnitudes including at 12, 25, or 37% change in surface area (ΔSA), roughly corresponding to 64, 86, and 100% total lung capacity, respectively (61). Stretch duration for all the readouts was 10 min, which was the time found previously for actin PJARs to be formed (24). We also measured permeability and cell death after 60 min of stretch to test the prolonged effect of stretch on these end point results. Monolayers were either pretreated with one of the inhibitors or agonists for a specific period of time, as detailed in Table 1, or pretreated with appropriate vehicle control (VC).

Table 1.

Rac1 pathway agonists and antagonists

| Name | Function | Concentration | Time | Reference | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wortmannin | PI3K inhibitor | 100 nM | 60 min | 60 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO |

| PIP3 | Akt/Rac1 agonist | 5 μM | 60 min | 36 | Echelon, Salt Lake City, UT |

| EHT-1864 | Rac1-GTP inhibitor | 10 μM | 60 min | 51 | Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO |

| β2-Chimerin | Rac GTPase-activating protein | 30 MOI | 48 h | 13 | Gift from Dr. M. G. Kazanietz, University of Pennsylvania |

| PDGF-AA | Rac1 agonist | 10 ng/ml | 15 min | 55 | Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA |

| IPA-3 | PAK-1 inhibitor, upstream of LIMK | 10 μM | 60 min | 7 | Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK |

| Calyculin-A | Protein phosphatase type 1 and 2A (PP1/PP2A) antagonist, to activate (dephosphorylate) cofilin | 10 nM | 30 min | 34 | Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA |

| 2-Deoxy-d-glucose + antimycin A | ATP depletion | 2 mM, 10 μM | 60 min | 15 | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO |

PI3K, phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate di-C8; MOI, multiplicity of infection; PDGF-AA, platelet-derived growth factor; LIMK, LIM kinase.

Western blot.

To determine whether LIMK, cofilin, Akt, and phosphatase SSH1L are activated by stretch, we identified their phosphorylation state (Table 2) in AEC monolayers using Western blotting.

Table 2.

Phosphorylation sites of tested Rac1 pathway proteins

Monolayers (3 wells/lysate) were washed with ice-cold Dulbecco's PBS twice and scraped in SDS sample reducing buffer (30 mM Tris·HCl, 1.25% SDS, 12.5% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol) containing 50 mM sodium fluoride, 1.0 mM PMSF, 5 mM EDTA, 2 mM sodium orthovanadate, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete Mini, Roche, Indianapolis, IN), sonicated for 5 s, and then boiled for 5 min. Samples were loaded equivalently (20 or 25 μg), and protein lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE (NuPAGE Novex 4–12% Bis-Tris Mini Gel, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), transferred to 0.2-μm pore polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (30 V for 90 min, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), blocked in nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad), then incubated at 4°C overnight with one of the following primary antibodies: anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473), anti-phospho-Akt (Thr308), anti-Akt, anti-phospho-LIMK1/2 (Thr508/Thr505), anti-LIMK1/2, anti-phospho-cofilin (Ser3), anti-cofilin (all Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), anti-phospho-SSH1L (Ser978), anti-SSH1L (ECM Bioscience, Versailles, KY), or anti-occludin (50 and 65 kDa, Invitrogen). Anti- hemagglutinin (HA)-tag antibody (Covance, Conshohocken, PA) was used to measure the overexpression of the HA-tagged β2-chimerin.

Membranes were washed three times in TBS/T (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20, Bio-Rad), incubated at room temperature for 90 min with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), then rinsed six times with TBS/T. Immunoreactive proteins were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (ECL Plus, GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Developed film (Hyperfilm ECL, GE Healthcare) was digitized and the relative density of the protein in the bands were quantified by scanning densitometry in ImageJ (ver. 1.43j) based on method optimization in Gassmann et al. (31). Background membrane intensity for each lane was subtracted from blot intensity. Membranes were stripped (Restore, Thermo Scientific, Logan, UT) for 20 min at room temperature and reprobed with the relevant total protein antibody if applicable or with anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH, Millipore, Billerica, MA) to ensure equivalent total protein loading across lanes (26). The average of three measurements was used for band density. For each band, normalized (n) protein density was calculated by dividing the density of the band by the unstretched-vehicle control (UNS-VC) band density. Normalized density of the phosphorylated protein was divided by normalized density of the respective total protein or GAPDH signal and reported.

Immunofluorescent staining of F-actin, phosphorylated LIMK1/2, and cofilin.

Following stretch, monolayers were fixed with 1.5% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked with 5% goat serum. Monolayers were stained for F-actin by using phalloidin (Invitrogen) and the images were analyzed as previously described (24). Monolayers were also stained for phosphorylated cofilin by using anti-phospho-cofilin (Ser3) or phosphorylated LIMK1/2 by using anti-phospho-LIMK1/2 (Thr508/Thr505, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA). Images were captured on an epifluorescence microscope (Eclipse TE300, ×10 objective, Nikon, Melville, NY).

Infection with β2-chimerin.

The Rac GTPase-activating protein β2-chimerin adenovirus was generously provided by Dr. M. G. Kazanietz (University of Pennsylvania), and its generation was described elsewhere (13). The type I-like AECs were infected with 30 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of the adenoviruses 3 days after isolation, and stretch experiments were performed 48 h after infection (Fig. 5B). LacZ (β-galactosidase) adenovirus with the same backbone as the β2-chimerin adenovirus was used as a control at the same MOI (70). LacZ was stained with a warm 0.8 mg/ml Xgal solution in PBS containing 0.4 mM MgCl2, 4 mM potassium ferrocyanide, and 4 mM potassium ferricyanide to ensure efficient delivery of the adenovirus (not shown).

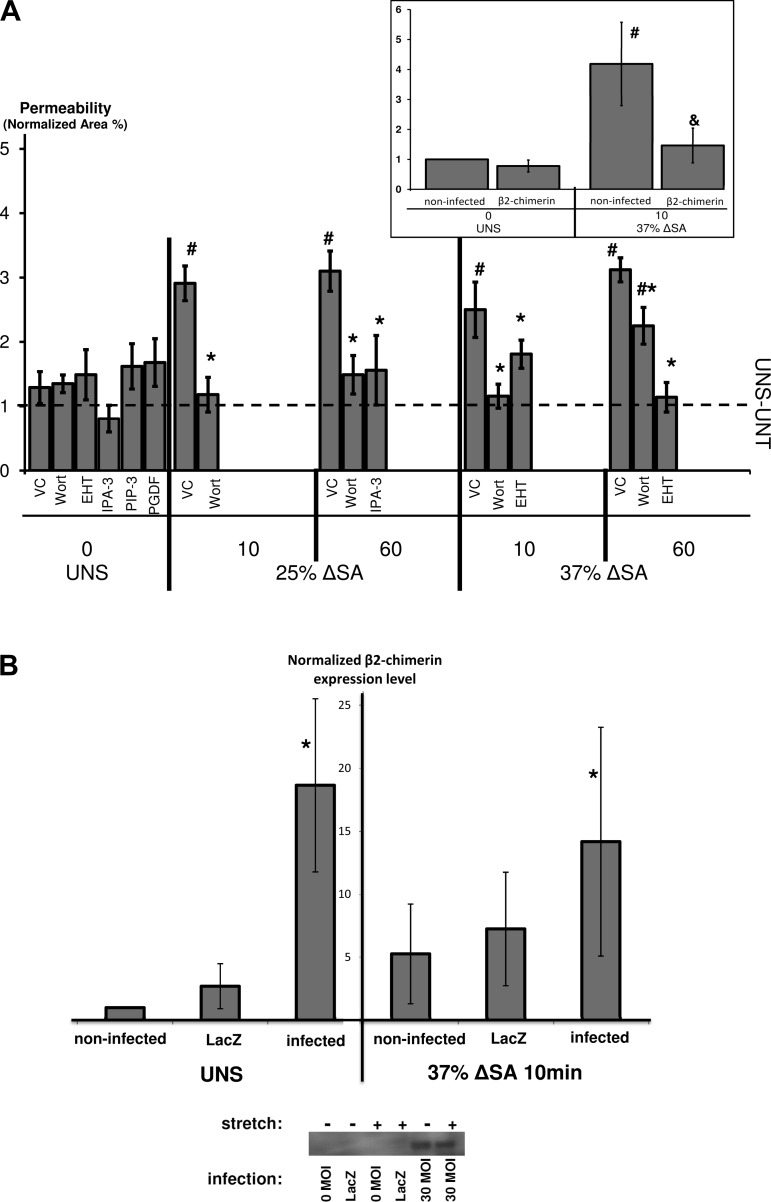

Fig. 5.

A: AEC monolayer paracellular permeability measured by the fluorescent tracer BODIPY-ouabain, in monolayers stretched for 10 or 60 min at 25 or 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz, compared with unstretched monolayers. BODIPY-ouabain image analysis was detailed elsewhere (25). Each data point is mean ± SE based on 3 images/well from 3 wells/animal from at least 3 animals/group. #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC and *P < 0.05 vs. stretch-VC. UNS-UNT, unstretched and untreated monolayers. Inset: paracellular permeability measured by the fluorescent tracer BODIPY-ouabain in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz, compared with unstretched monolayers, with and without infection with the Rac GTPase-activating protein β2-chimerin adenovirus. #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-noninfected monolayers and &P < 0.05 vs. stretch-noninfected monolayers. B: expression levels of β2-chimerin in UNS and stretched (37% ΔSA ¼ Hz 10 min) type I-like rat AEC monolayers, measured by Western blot. Data are fold change relative to UNS-noninfected cells, means ± SE from at least 4 animals/group (2 for LacZ) with *P < 0.05 vs. noninfected.

Monolayer permeability.

Permeability was estimated using a fluorescent BODIPY-tagged ouabain (radius ∼15–20 Å; Invitrogen), which selectively binds to the Na+-K+ ATPase pumps on the basolateral surface of the plasma membrane when the TJs are breached (14), and quantified as previously described (25).

Cell death quantification.

Monolayers were stained for dead cells by using 0.2 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (Invitrogen) as previously done (61), as well as for nuclei using 5 μg/ml (8.11 μM) Hoechst (Molecular Probes). Following the stretch or no-stretch period, monolayers were washed thoroughly and imaged (Eclipse TE300 epifluorescence microscope, ×10 objective, Nikon, Melville, NY) for dead stain, nuclei, and phase (not shown). The number of dead cells and the total number of cells per field was counted using a MATLAB (ver. 6.5 R13, The MathWorks, Natick, MA) program that identifies and counts ethidium homodimer-1-stained nuclei (dead cells) in the red channel and Hoechst-stained nuclei (total cells) in the blue channel of each image (3 images/monolayer). Cell mortality (% dead) was calculated by dividing the number of dead cells by the total number of cells in a field.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were performed at least three times, each time with cells from a different animal. All the data presented were expressed as means ± SE. Data were deemed statistically significant at P ≤ 0.05. All the statistical tests were implemented in JMP (version 8.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

To test the effect of stretch, readout values were compared with time-matched unstretched-untreated controls using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett's test (72). To test the effect of treatment (inhibitors or exogenous agonists), readout values were compared with time-matched VCs as well as UNS-VCs by a two-way ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer post hoc analysis (72).

RESULTS

Rac1 downstream proteins are activated by stretch.

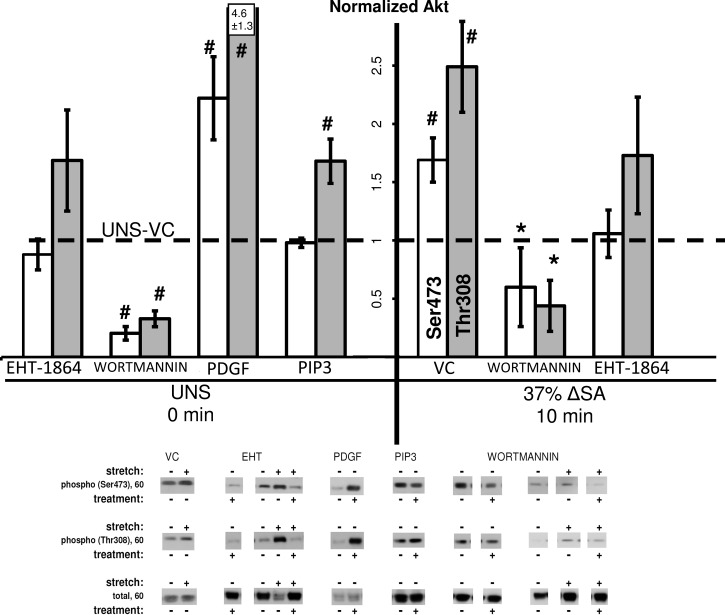

We hypothesized that actin cytoskeleton remodeling during formation of PJARs would be accompanied by an increase in phosphorylation of Rac1 downstream proteins Akt and LIMK1/2 and by a decrease in phosphorylation of cofilin. Akt (PKB) phosphorylation increased in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz (Fig. 1) but revealed a stretch magnitude effect because in monolayers stretched to 25% ΔSA the data for both phosphorylation sites (Ser473 and Thr308) were not significantly different from unstretched monolayers (data not shown). Moreover, monolayers that were treated with the Rac1-GTP inhibitor EHT-1864 and stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA showed no difference in Akt phosphorylation compared with unstretched monolayers treated with VC, suggesting that inhibition of Rac1 activation modulates the stretch-induced phosphorylation of Akt. Consistently, inhibition of PI3K with wortmannin with and without stretch resulted in decreased Akt phosphorylation in monolayers treated with 10 nM (not shown) or 100 nM wortmannin. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate di-C8 (PIP3), a Rac1 activator, was found to increase Akt phosphorylation (Thr308 only) in unstretched (UNS) monolayers compared with VC-treated monolayers, confirming that Rac1 is upstream of Akt. Furthermore, exogenous PDGF, an activator of endogenous Rac1, also increased Akt phosphorylation (both Ser473 and Thr308) in unstretched monolayers compared with VC monolayers.

Fig. 1.

Phosphorylation of Akt at Ser473 site (open bars) and at Thr308 site (shaded bars) in alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% change in surface area (ΔSA) ¼ Hz compared with unstretched monolayers (UNS). The phosphorylated signal was divided by the total signal, after normalization of each signal to the signal from unstretched monolayers treated with vehicle control (UNS-VC, dashed line). Typical Western blot signals are shown below groups. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with *P < 0.05 vs. stretched monolayers treated with vehicle control (stretch-VC), #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC. EHT, EHT-1864; PIP3, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate di-C8.

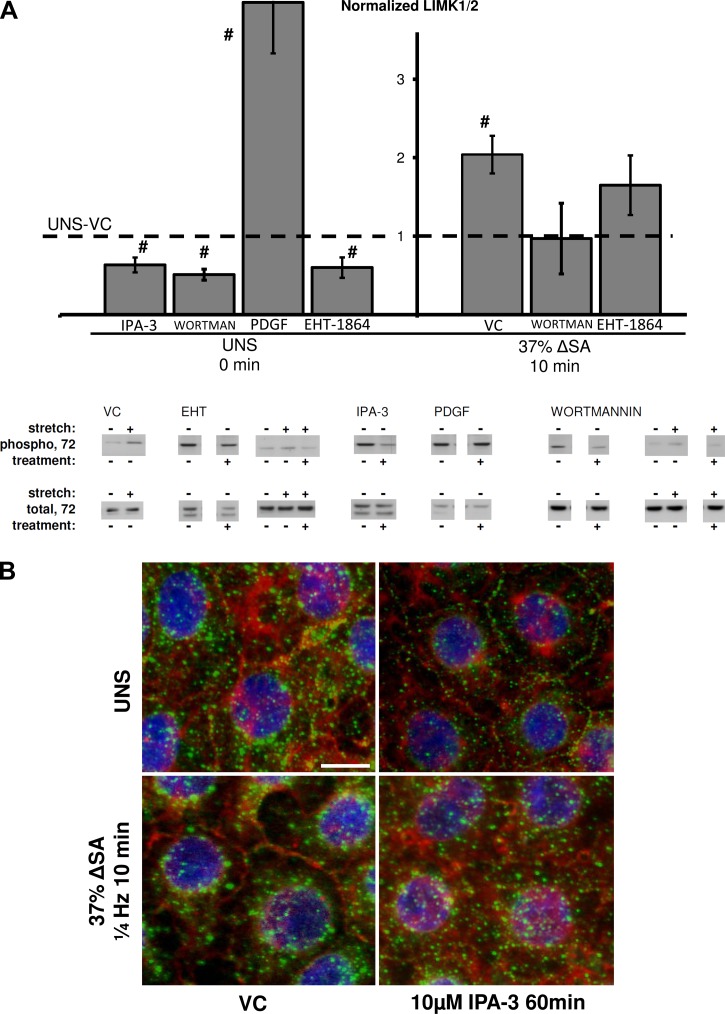

LIMK1/2 phosphorylation increased in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz compared with unstretched monolayers (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, phosphorylated LIMK1/2 (green) was localized to the perinuclear regions of the cell in stretched monolayers compared with nonlocalized phosphorylated LIMK1/2 in unstretched monolayers (Fig. 2B), suggesting that LIMK1/2 is activated by stretch. LIMK1/2 phosphorylation was decreased in unstretched monolayers treated with EHT-1864 and wortmannin compared with VC (Fig. 2A), and, consistently, stretched monolayers treated with EHT-1864 or wortmannin were not significantly different from unstretched monolayers treated with VC. Phosphorylation of LIMK1/2 was also decreased in unstretched monolayers treated with IPA-3, PAK-1 inhibitor, compared with monolayers treated with VC (Figs. 2, A and B). In stretched monolayers, IPA-3 abolished the polarization of phosphorylated LIMK1/2, resulting in a distribution of the protein that resembles unstretched monolayers. Treating unstretched monolayers with PDGF showed increased LIMK1/2 phosphorylation compared with VC monolayers (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

A: phosphorylation of LIM kinase (LIMK1/2) at Thr508/5 site in AEC monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz compared with unstretched monolayers. The phosphorylated signal was divided by the total signal, after normalization of each signal to the signal from UNS-VC (dashed line). Typical Western blot signals are shown below groups. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC. B: type I-like rat AEC monolayers stained for F-actin with phalloidin (red), phosphorylated LIM kinase (green), and nuclei with DAPI (blue), left unstretched, or after 10 min of 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz cyclic stretch. Bar = 10 μm.

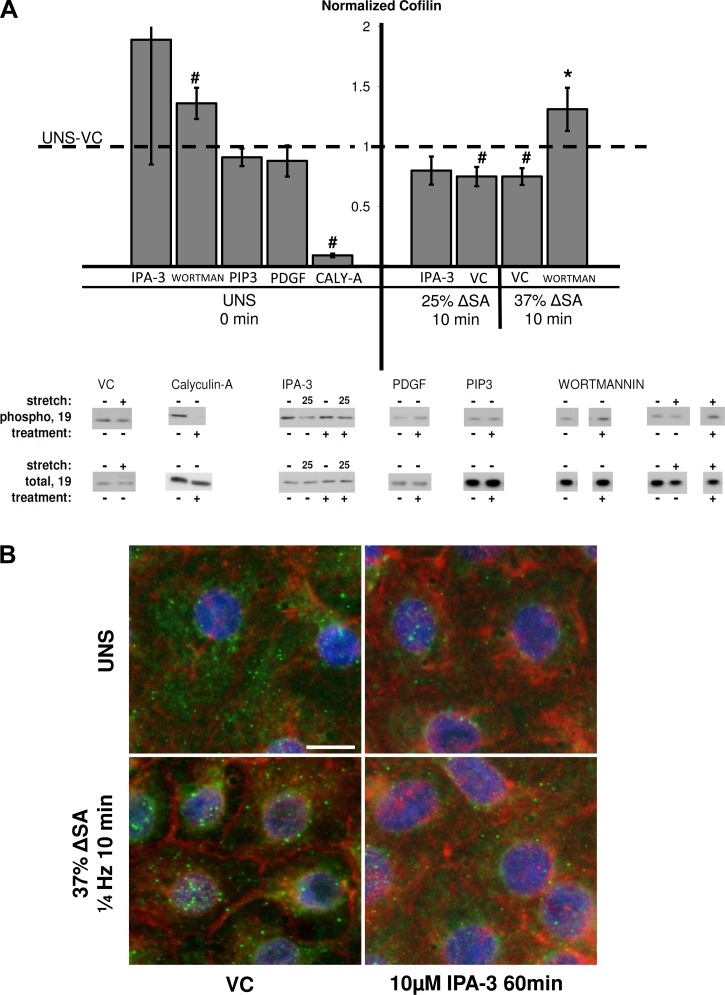

Cofilin phosphorylation, which indicates its inactivation, was significantly lower in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 25 and 37% ΔSA compared with unstretched untreated monolayers, whereas it was not decreased in cells stretched for 10 min at 12% ΔSA (data for 25 and 37% ΔSA only are shown in Fig. 3A). Furthermore, inactivated (phosphorylated) cofilin (green) was localized to the perinuclear regions of the cell in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA compared with nonlocalized phosphorylated cofilin in unstretched monolayers (Fig. 3B). Thus we find that cofilin is activated with stretch in a magnitude- and duration-dependent manner and that inactivated cofilin is sequestered away from the perijunction in stretched monolayers. In addition, wortmannin inactivated (phosphorylated) cofilin in unstretched monolayers and also increased cofilin phosphorylation in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA compared with stretched VC (Fig. 3A). Treating unstretched monolayers and monolayers stretched at 25% ΔSA for 10 min with IPA-3 resulted in insignificant difference from unstretched cells treated with VC (Figs. 3, A and B). The distribution of phosphorylated cofilin in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA resembled unstretched monolayers (Fig. 3B). Cofilin phosphorylation was greatly decreased in unstretched monolayers treated with the cofilin activator calyculin-A, compared with VC-treated monolayers (Fig. 3A). The Rac1 activators PIP3 and PDGF did not affect cofilin phosphorylation in unstretched monolayers, suggesting that other pathways may also be involved in cofilin phosphorylation (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

A: phosphorylation of cofilin at Ser3 site in AEC monolayers stretched for 10 min at 25 or 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz compared with unstretched monolayers. The phosphorylated signal was divided by the total signal, after normalization of each signal to the signal from UNS-VC (dashed line). Typical Western blot signals are shown below groups for 37% ΔSA unless otherwise indicated. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC and *P < 0.05 vs. stretch-VC. B: type I-like rat AEC monolayers stained for F-actin with phalloidin (red), phosphorylated cofilin (green), and nuclei with DAPI (blue), left unstretched (UNS), or after 10 min of 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz cyclic stretch. Bar = 10 μm.

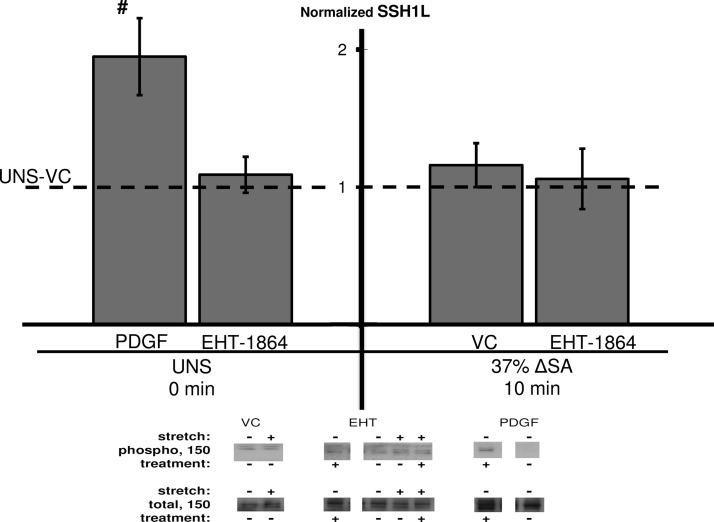

Additionally, we found no change in SSH1L phosphorylation in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA, compared with unstretched untreated monolayers (Fig. 4). Treating the AEC monolayers with EHT-1864 did not affect SSH1L phosphorylation in both unstretched and stretched monolayers. Interestingly, SSH1L phosphorylation increased in unstretched monolayers treated with PDGF compared with VC monolayers (Fig. 4), suggesting that PDGF phosphorylates SSH1L via different pathways than the one tested here.

Fig. 4.

Phosphorylation of slingshot-1 (SSH1L) at Ser978 site in AEC monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz compared with unstretched monolayers. The phosphorylated signal was divided by the total signal, after normalization of each signal to the signal from UNS-VC (dashed line). Typical Western blot signals are shown below groups. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC.

Rac1 pathway modulates stretch-induced increases in paracellular permeability.

Stretching AEC monolayers for 10 and 60 min significantly increased the monolayer permeability measured by using the fluorescent tracer BODIPY-ouabain (14), when the magnitude of stretch was 25 or 37% ΔSA, but not 12% ΔSA (Fig. 5A, data for 12% ΔSA not shown), compared with unstretched monolayers. In fact, permeability data for 25 and 37% ΔSA were also significantly higher than the data for 12% ΔSA, suggesting that the barrier integrity is stretch magnitude sensitive. We hypothesized that reduced Rac1 activity would strengthen monolayer barrier function in stretched monolayers. Permeability measurements in monolayers treated with EHT-1864 and stretched for 10 and 60 min of 37% ΔSA were significantly lower compared with stretched monolayers treated with VC and were not different from those in unstretched monolayers (Fig. 5A), suggesting that activation of the Rac1 pathway leads to compromised barrier function. Moreover, when we infected the cells with Rac GTPase-activating protein β2-chimerin adenovirus (Fig. 5B), we found very similar results to the data from the EHT-1864-treated monolayers (Fig. 5A, inset). In unstretched monolayers, permeability was unaffected by the β2-chimerin infection compared with noninfected cells. In monolayers stretched for 10 min to 37% ΔSA, permeability was significantly attenuated by the β2-chimerin compared with noninfected stretched monolayers.

Similarly, wortmannin decreased permeability in monolayers stretched for 10 and 60 min at 25% ΔSA or 10 min of 37% ΔSA, and no difference was found from unstretched monolayers treated with VC (Fig. 5A). Wortmannin-treated monolayers stretched for 60 min at 37% ΔSA showed significantly reduced permeability compared with stretched-VC monolayers; however, permeability was still significantly higher than in UNS-VC monolayers. Finally, monolayers stretched for 60 min at 25% ΔSA and treated with IPA-3 showed reduced BODIPY-ouabain staining compared with stretched monolayers treated with VC (Fig. 5A). Treating unstretched cells with wortmannin, EHT-1864, or IPA-3 did not yield significant changes in permeability. Importantly, treating unstretched cultures with PIP3 or PDGF did not result in increased monolayer permeability (Fig. 5A), suggesting that activation of the Rac1 pathway alone is not enough for induction of significant increases in permeability and that other pathways contribute to the stretch-induced damage to the epithelial barrier.

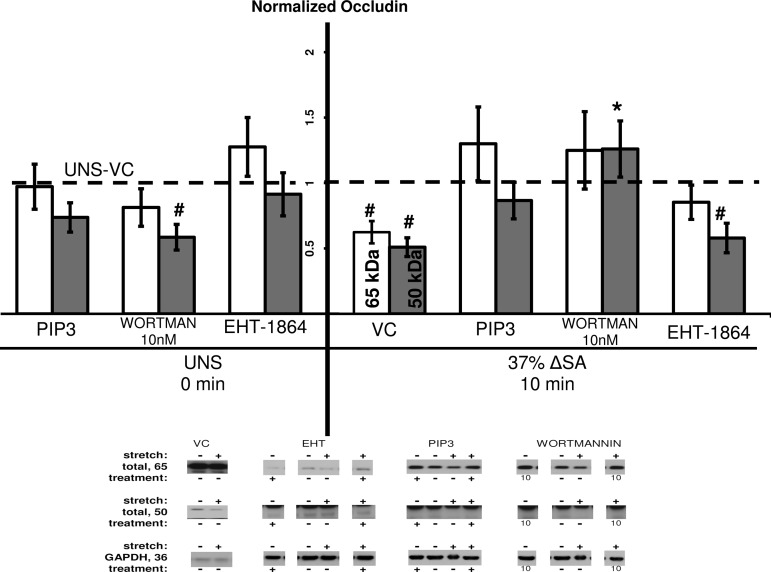

The TJ protein occludin, linked internally to the actin cytoskeleton via zona occludens 1 (ZO-1) (29), was previously shown to decrease in AEC monolayers stretched for 60 min at 37% ΔSA (15), and here we show similar results for both the 50-kDa and 65-kDa bands of occludin, compared with unstretched monolayers treated with VC (Fig. 6). Occludin content in stretched monolayers treated with EHT-1864 showed no change in the 50-kDa form compared with stretched monolayers treated with VC. However, the 65-kDa form of occludin did increase in stretched monolayers treated with EHT-1864, becoming insignificantly different from unstretched monolayers treated with VC. Thus EHT-1864 rescues the 65-kDa form of occludin in stretched monolayers. Additionally, occludin (65 kDa) was not different in wortmannin-treated stretched monolayers compared with unstretched monolayers treated with VC, whereas the 50-kDa occludin was even increased in wortmannin-treated monolayers that were stretched at 37% ΔSA for 10 min compared with stretched monolayers treated with VC. Altogether these data suggest that the Rac1 pathway has a role in decreased occludin content due to stretch. However, in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA and treated with PIP3, there was no attenuation of occludin content (65 and 50 kDa) compared with unstretched monolayers treated with VC (Fig. 6), suggesting that PIP3 has a protective role during this short period of stretch, perhaps through activation of signaling pathways different from Rac1.

Fig. 6.

Occludin 65 kDa (open bars) and 50 kDa (shaded bars) content in AEC monolayers stretched for 10 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz compared with UNS monolayers. The occludin signal for each molecular weight was divided by GAPDH signal after normalization of each signal to the signal from UNS-VC (dashed line). Typical Western blot signals are shown below groups. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with *P < 0.05 vs. stretch-VC, #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC.

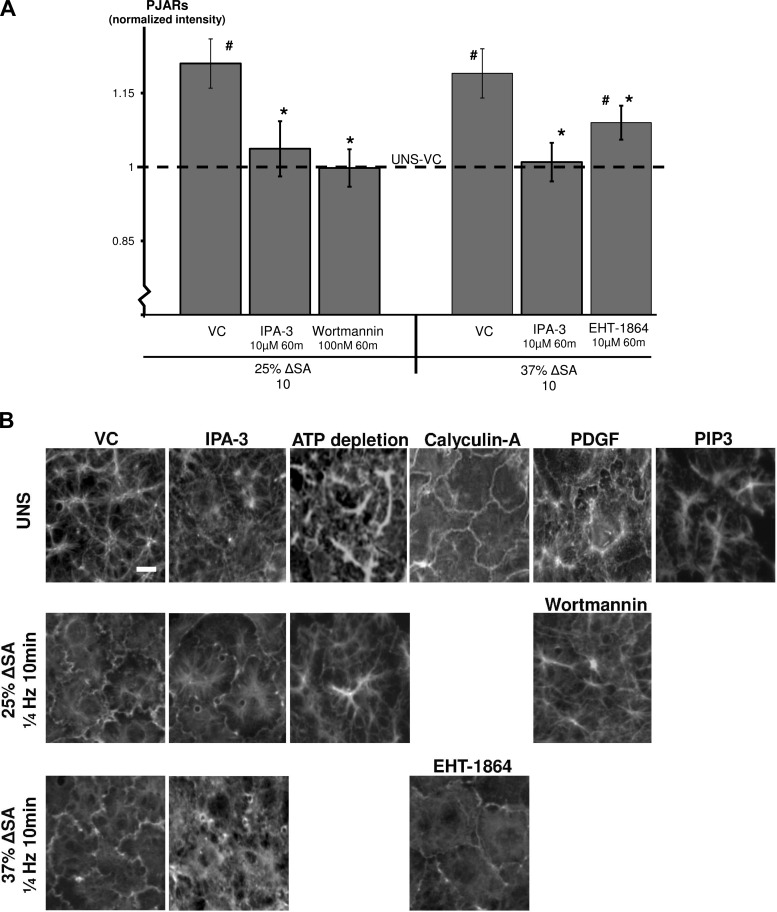

Rac1 pathway affects stretch-induced PJAR formation.

We have previously shown that stretch of primary rat AEC monolayers forms PJARs and rapidly reorganizes actin binding sites at the plasma membrane in a manner dependent on stretch magnitude and frequency (24). We now show significant increases in PJAR intensity in monolayers stretched for 10 min at 25% ΔSA but not in monolayers stretched at the same magnitude and treated with wortmannin (Fig. 7A). This is consistent with F-actin images showing F-actin remodeling and PJAR formation in these monolayers (Fig. 7B). Using EHT-1864 we show reduced PJAR intensity in monolayers stretched for 10 min also at 37% ΔSA compared with monolayers stretched at the same magnitude and time but treated with VC (Figs. 7, A and B). PJAR intensity in EHT-1864-treated stretched monolayers, however, was still significantly higher compared with UNS-VC monolayers. In addition, monolayers stretched for 10 min at 25 and 37% ΔSA and treated with IPA-3 showed significantly lower PJAR intensity (Fig. 7A), supported by immunofluorescent images (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

A: perijunctional actin ring (PJAR) intensity (Pi) found by taking the ratio of peripheral annulus F-actin mean intensity (Ai) to whole cell F-actin mean intensity (Wi; Pi = Ai/Wi), in AEC monolayers stretched for 10 min at 25 or 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz. PJAR image analysis was detailed elsewhere (24). Data shown are means ± SE with #P < 0.05 compared with UNS-VC and *P < 0.05 compared with stretch-VC. Each data point represents an average 32 cells per animal from at least 4 different animals. B: type I-like rat AEC monolayers immunostained with phalloidin-labeled F-actin and left unstretched or after 10 min of 25 or 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz stretch. Bar = 10 μm.

Unstretched monolayers treated with PDGF, but not with PIP3, showed F-actin in a PJAR structure, similar to stretched monolayers without treatment (Fig. 7B). This suggests that the Rac1 pathway is involved in stretch-induced PJAR formation; however, as for occludin data, PIP3 has a more complex effect on the cell response to stretch than uniquely activating the Rac1 pathway. In unstretched monolayers, calyculin-A, a cofilin activator, increased PJAR formation (Fig. 7B). Finally, hypothesizing that ATP is required for Rac1 pathway activation and subsequent PJAR formation, we show that using 2-deoxy-d-glucose and antimycin A to deplete ATP resulted in inhibited actin remodeling and PJAR formation in both unstretched monolayers and monolayers that were stretched for 10 min at 25% ΔSA (Fig. 7B).

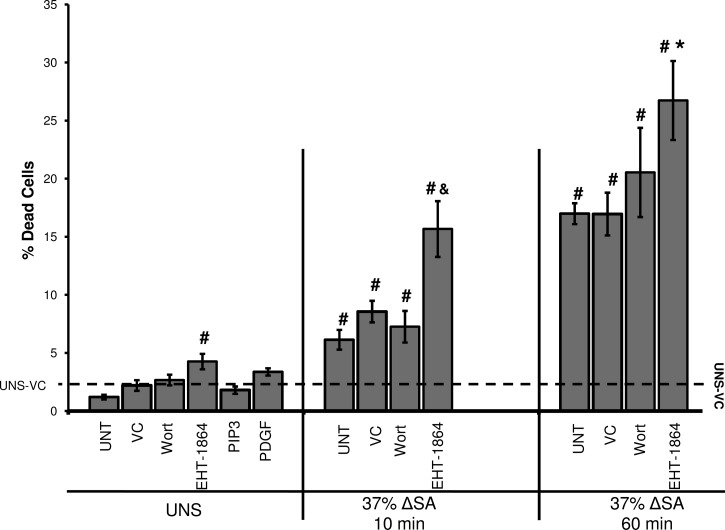

Rac1 pathway influences stretch-induced cell death.

Cell death increased significantly in monolayers stretched at 25 and 37% ΔSA for 10 or 60 min (data for 37% ΔSA are presented in Fig. 8). At 37% ΔSA, cell death was significantly higher than in monolayers stretched at 25% ΔSA (data not shown) and also showed a time dependency, with increased cell death at 60 min stretch compared with 10 min. Thus we find stretch magnitude- and time-dependent cell death in stretched AEC monolayers. The Rac1 pathway inhibitor wortmannin did not change cell death in either unstretched monolayers or those stretched for 10 and 60 min at 37% ΔSA compared with corresponding VC-treated cultures (Fig. 8). However, the percent of cell death in both unstretched monolayers and monolayers stretched for 10 and 60 min at 37% ΔSA that were treated with EHT-1864 significantly increased compared with VC-treated monolayers, suggesting that Rac1 pathway activation may have a cytoprotective effect on the stretched cells. However, exogenous PIP3 or PDGF, Rac1 activators, did not significantly decrease cell death in unstretched monolayers (Fig. 8) or in monolayers that were stretched at 37% ΔSA for 10 and 60 min compared with untreated stretched cells (not shown), suggesting that these treatments did not offer further protection against stretch-induced cell death. Altogether these data suggest that the Rac1 pathway is not a major contributor to stretch-induced cell death and that there are other pathways that do so more primarily.

Fig. 8.

Percent of dead cells in UNS and in monolayers stretched for 10 or 60 min at 37% ΔSA ¼ Hz. Data are means ± SE from at least 3 animals/group with #P < 0.05 vs. UNS-VC, *P < 0.05 vs. 37% 60 min VC, and &P < 0.05 vs. 37% 10 min VC.

DISCUSSION

In the present paper, we found increases in the phosphorylation of Akt and LIMK and a decrease in cofilin phosphorylation (Figs. 1–3). In monolayers stretched for 10 or 60 min at 37% ΔSA, Rac1 pathway inhibitors wortmannin and EHT-1864 attenuated the stretch-induced increase in permeability (Fig. 5A) and also partially helped rescue the stretch-induced reduction of TJ protein occludin (Fig. 6). In addition, EHT-1864 and IPA-3, a PAK-1 inhibitor upstream of LIMK, reduced the stretch-induced PJAR formation compared with stretched monolayers that were treated with VC (Figs. 7, A and B). Altogether, our data suggest that constitutive activity of Rac1, which is necessary for stretch-induced activation of the Rac1 downstream proteins Akt, LIMK, and cofilin, mediates the stretch-induced increases in permeability and actin reorganization.

Sensitivity of Rac1 signaling pathway to stretch.

We report that stretch increased the activity of downstream Rac1 pathway proteins Akt, LIMK1/2, and cofilin in primary type I-like AEC monolayers (Figs. 1–3). Akt phosphorylation increased in monolayers stretched at 37% ΔSA but not at 25% ΔSA (Fig. 1). Interestingly, others have shown in endothelial cells that moderate physiological levels of cyclic stretch (6–10%, 1 Hz, 30 min) phosphorylated Akt and inhibited apoptosis, while higher stretch magnitudes (20%, 1 Hz) stimulated apoptosis (46). Moreover, decreased Akt phosphorylation was found in rat type II alveolar cells stretched at 30% ΔSA for 2 or 24 h (33). Altogether, these outcomes suggest that Akt phosphorylation is stretch magnitude dependent and may also depend on the cell type. Treating unstretched cells with exogenous PIP3 or PDGF increased Akt phosphorylation (Fig. 1). These outcomes agree with previous studies in which PIP3 was ectopically implanted into the apical portion of MDCK epithelial cells and increased GTP-bound Rac and phosphorylation of Akt by 5 min (30), whereas in Saos2 cells (16) and smooth muscle cells (38) treatment with PDGF has led to increased Akt phosphorylation and activation.

Downstream of Rac1, we show that stretch activated LIMK1/2 (Fig. 2A), which others have shown leads to cofilin phosphorylation, accumulation of actin filaments (5), PJAR formation (71), and F-actin stabilization in a Rac-dependent manner (5, 27, 71). Consistent with these studies, we show that stretch of AECs dephosphorylated (activated) cofilin (Fig. 3A), and depolymerized actin, likely as part of stretch-induced reorganization of actin into PJARs (24).

Rac1 pathway role in stretch-induced increase in paracellular permeability.

Previously, stretch of alveolar epithelial cells was shown to result in increased permeability in vitro (58). In the present study, monolayer permeability increased within 10 min in stretched AEC monolayers in a magnitude-dependent manner (Fig. 5A), similar to the time course reported for actin reorganization (24). Permeability was attenuated significantly with wortmannin treatment in monolayers stretched for 10 and 60 min at both 25 and 37% ΔSA stretch. EHT-1864 also attenuated the increase in permeability in monolayers stretched at 37% ΔSA for 10 or 60 min of stretch. Finally, Rac1 inhibition with β2-chimerin (Fig. 5A, inset) or PAK-1 inhibition with IPA-3 (Fig. 5A) both attenuated stretch-induced increases in monolayer permeability. Altogether, these data suggest that the Rac1 pathway has an important role in stretch-induced increases in epithelial permeability. However, because treating unstretched monolayers with the Rac1 activators PIP3 or PDGF did not result in increased permeability compared with VC-treated cells, possibly owing to broader effects these agents have on the cells, we conclude that the Rac1 pathway alone is not sufficient for significant increases in permeability and that other pathways also contribute to the stretch-induced impairment of the epithelial barrier.

We hypothesized that the stretch-induced permeability modulation associated with the Rac1 pathway would influence TJ proteins and actin. Accordingly, occludin content was decreased (both 50 and 65 kDa) in monolayers stretched at 37% ΔSA for 10 min (Fig. 6). Likewise, AEC monolayers stretched at longer durations (60 min) at 25 or 37% ΔSA also showed loss of occludin content (15, 19). During stretch, wortmannin prevented the stretch-induced decrease of occludin, but EHT-1864 provided only partial rescue. Because decreased occludin has been correlated with impaired TJ barrier function (18), we hypothesize that stretch-induced dissociation of the actin-occludin bond may cause loss of occludin, PJAR formation, and an increase in monolayer permeability. Nevertheless, we have previously studied the intensity of perijunctional ZO-1 by taking the ratio of peripheral annulus ZO-1 mean intensity to whole cell ZO-1 mean intensity in cells that were stretched at 12, 25, and 37% ΔSA for 60 min and did not find any differences between the stretched and unstretched preparations (23).

Rac1 pathway role in stretch-induced PJAR formation.

Previously we reported that cyclic stretch induces the formation of PJARs in rat AECs, correlated with stretch-induced increase in paracellular permeability (24). Here we show attenuation of PJAR formation in stretched cells treated with the Rac1 pathway inhibitors: PI3K inhibitor wortmannin, Rac1-GTP inhibitor EHT-1864, or PAK-1 inhibitor IPA-3 (Fig. 7, A and B). The link between the Rac1 pathway and actin cytoskeleton reorganization, including PJAR formation, was previously shown in other cells (49, 55), and our data add to understanding the mechanism through which it occurs. In agreement with published studies, unstretched monolayers immunostained for phosphorylated LIMK1/2 and phosphorylated cofilin exhibit homogeneous distribution of both proteins (Figs. 2B and 3B; 1, 66). Here we show that stretch colocalized activated (phosphorylated) LIMK1/2 and inactive (phosphorylated) cofilin to the perinuclear region, and also formed PJARs (Fig. 7, A and B). Furthermore, in unstretched monolayers incubated with IPA-3 to inhibit PAK-1, subcellular polarization of phosphorylated LIMK1/2 and phosphorylated cofilin is abolished (Figs. 2B, 3B), perinuclear stress fibers remain, and PJAR formation is inhibited (Fig. 7B). Similarly, stretched monolayers incubated with wortmannin or EHT-1864 show decreased activation of LIMK1/2 and cofilin and attenuated PJAR formation (Figs. 2A, 3A, and 7, A and B).

Taken together, these data suggest that stretch activates LIMK1/2 and cofilin, polarizes the subcellular localization of active LIMK1/2 and cofilin, and results in the reduction of perinuclear stress fibers and the formation or accumulation of peripheral stress fibers (PJARs). This pathway can be inhibited with IPA-3, wortmannin, or EHT-1864, resulting in attenuated or a completely abolished formation of PJARs.

Offering additional insight, our data in unstretched cells show that calyculin-A stimulation decreases cofilin phosphorylation (Fig. 3A) and causes PJAR formation (Fig. 7B). Because calyculin-A is an antagonist of type 1 and 2A protein phosphatases (PP1 and PP2A; 34, 37), these results suggest that PJAR formation in AEC monolayers is independent of PP1 or PP2A. In addition, ATP depletion prevented PJAR formation in both unstretched and stretched monolayers (Fig. 7B), suggesting that actin remodeling and PJAR formation in stretched AEC monolayers are ATP dependent. Although ATP depletion inhibits PJAR formation in stretched monolayers, which was previously shown to be beneficial to paracellular barrier strength (15), in other studies it has also been shown to break down TJs (6). More studies to test the mechanisms of actin-TJ associations are thus required.

Rac1 pathway role in stretch-induced cell death.

Cell death increased significantly in stretched monolayers (Fig. 8), in a time- and magnitude-dependent manner. These data agree with previous data with cyclic stretch as well as with a single deformation (61, 63). Wortmannin did not affect cell death in AEC monolayers whereas EHT-1864 significantly increased cell death in both unstretched and stretched monolayers compared with their respective VCs. These data suggest a lack of correlation between the effect of Rac1 pathway inhibition on stretch-induced increases in permeability and on cell death. Here and previously we have shown that even at high magnitudes of stretch (37% ΔSA) for 1 h, the stretch-induced increases in epithelial barrier permeability occur without a dramatic increase in cell death (∼9–17%; Ref. 61). Furthermore, to test whether apoptosis is initiated during 1 h of stretch but evident only several hours later, we measured cell death in monolayers that were stretched for 1 h at 37% ΔSA and then incubated at rest for additional 23 h (6.71 ± 5.39%), compared with monolayers that were kept at rest for 23 h and then stretched at the same magnitude for 1 h (12.42 ± 5.39%). The results showed no significant difference between the two groups, suggesting that 1 h of stretch at 37% ΔSA does not result in additional cell death at a later time point.

Moreover, to further explore the relationship between cell death and permeability at different stretch durations, we stretched cells at 37% ΔSA for 1 and 6 h and measured cell death and permeability. Quantification of the data revealed no significant change both in cell death and in permeability between the two stretch durations (cell death above unstretched cells: 18.78 ± 5.05% for the 1-h group, and 29.57 ± 2.31% for the 6-h group; permeability normalized to unstretched cells: 6.70 ± 5.75 for the 1-h group, and 18.99 ± 12.13 for the 6-h group). Stretching cells for 24 h did not increase permeability (17.61 ± 6.61) above the 1- or 6-h groups; however, it resulted in significantly more cell death (42.52 ± 8.77% above unstretched levels). These data suggest that cell death is not the only mechanism leading to increased permeability in response to stretch. Moreover, in those studies we showed that, although occasionally there was a colocalization of dead cells with the permeability tracer, there are numerous locations where the barrier function is compromised without any indication of cell death (see Fig. 3 in Ref. 14 for example). Altogether, this suggests that Rac1 pathway association with stretch-induced increased permeability does not necessarily have to protect the cells from stretch-induced death.

In addition, although others found that stimulating Akt directly with PIP3 resulted in decreased cell death (73), and that constitutively active PI3K or Akt can even block anoikis (41), we did not find any cytoprotective response in PIP3- or PDGF-treated stretched or unstretched monolayers. Because cell death is not the major contributor to stretch-induced increased permeability in our monolayers, it is not clear whether Akt activation due to stretch is a damaging or a protective event. By direct inhibition of Akt, future studies may test whether Akt activation due to stretch contributes to increased permeability, or whether it is a protective event. Altogether, these data suggest that the permeability rescue associated with inhibiting the Rac1 pathway is not associated with decreased stretch-induced cell death.

Direct Rac1 activation measurement in response to mechanical stress.

In this paper we have associated stretch-induced cellular alterations with activation of the Rac1 downstream proteins Akt, LIMK, and cofilin; however, we have not demonstrated a direct stretch-induced activation of the Rac1 protein itself, because of the following reasons. Firstly, Rac1 activation in response to physical forces is a cell-specific, rapid, and transient event, which also depends on the specific stretch parameters (39, 40, 45, 53, 57, 67). Secondly, it has been previously well-established that Rac1 activation is very sensitive to cell density and culture confluence (e.g., 44, 54), with baseline Rac1 activity increasing with cell density. Because our primary rat type I-like AECs form dense, confluent monolayers with TJs between the cells, we expect a very high and constitutive level of Rac1 activation even in unstretched cultures. Consistent with this hypothesis, we demonstrated in multiple studies that inhibition of Rac1 during stretch protects barrier properties (Fig. 5A), preserves TJ proteins (Fig. 6), alters the formation of PJARs (Fig. 7), and mediates downstream proteins in the Rac1 pathway (Figs. 1, 2A, and 3A), suggesting a high baseline level of Rac1 activity in our monolayers. We postulate that this high baseline activity level allows the stretch-induced acute changes in Rac1 downstream proteins Akt, LIMK, and cofilin, which leads eventually to the changes in actin organization and permeability in response to stretch.

Conclusions.

In the present paper, we have shown that stretch increases the paracellular permeability of AEC monolayers through the activation of the Rac1/Akt pathway. We have demonstrated that Akt, LIMK1/2 and cofilin are activated rapidly by stretch, and that their activation is accompanied by actin remodeling, PJAR formation, occludin content reduction, and increased monolayer permeability. We have shown that inhibition of Rac1 in stretched cells attenuates the activation of Rac1 downstream proteins and PJAR formation, and it partially protects the monolayer barrier properties during stretch. We conclude that high-magnitude biaxial stretch within the physiological range rapidly increases Rac1 pathway activity, resulting in actin cytoskeletal remodeling and increased monolayer permeability. Future studies may explore inhibiting the Rac1 pathway to treat or prevent pulmonary edema associated with large tidal volume (65, 68).

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH R01-HL-057204 and R01-CA-74197 grants, and the University of Pennsylvania Ashton Fellowship program.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.C.D., N.D., and S.S.M. conception and design of research; B.C.D. and N.D. performed experiments; B.C.D. and N.D. analyzed data; B.C.D., N.D., M.G.K., and S.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; B.C.D. and N.D. prepared figures; B.C.D. and N.D. drafted manuscript; M.G.K. and S.S.M. edited, revised, and approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Gladys Gray Lawrence and Hong-Bin Wang for assistance with Lac-Z staining and β2-chimerin Western blotting, Anirudh Lingamaneni for assisting with PJAR intensity quantification, Jessie Huang for assisting with densitometry, and Nicole Ibrahim for running several cell death studies.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acevedo K, Moussi N, Li R, Soo P, Bernard O. LIM kinase 2 is widely expressed in all tissues. J Histochem Cytochem 54: 487–501, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agnew BJ, Minamide LS, Bamburg JR. Reactivation of phosphorylated actin depolymerizing factor and identification of the regulatory site. J Biol Chem 270: 17582–17587, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albinsson S, Hellstrand P. Integration of signal pathways for stretch-dependent growth and differentiation in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C772–C782, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alessi DR, Andjelkovic M, Caudwell B, Cron P, Morrice N, Cohen P, Hemmings BA. Mechanism of activation of protein kinase B by insulin and IGF-1. EMBO J 15: 6541–6551, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arber S, Barbayannis FA, Hanser H, Schneider C, Stanyon CA, Bernard O, Caroni P. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature 393: 805–809, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bacallao R, Garfinkel A, Monke S, Zampighi G, Mandel LJ. ATP depletion: a novel method to study junctional properties in epithelial tissues. I. Rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 107: 3301–3313, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bokoch GM. PAK'n it in: identification of a selective PAK inhibitor. Chem Biol 15: 305–306, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Borok Z, Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Defined medium for primary culture de novo of adult rat alveolar epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 30A: 99–104, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruewer M, Hopkins AM, Hobert ME, Nusrat A, Madara JL. RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 exert distinct effects on epithelial barrier via selective structural and biochemical modulation of junctional proteins and F-actin. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 287: C327–C335, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J, Greenberg ME. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell 96: 857–868, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burgering BM, Coffer PJ. Protein kinase B (c-Akt) in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase signal transduction. Nature 376: 599–602, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cain RJ, Vanhaesebroeck B, Ridley AJ. The PI3K p110alpha isoform regulates endothelial adherens junctions via Pyk2 and Rac1. J Cell Biol 188: 863–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caloca MJ, Wang H, Kazanietz MG. Characterization of the Rac-GAP (Rac-GTPase-activating protein) activity of beta2-chimaerin, a ‘non-protein kinase C’ phorbol ester receptor. Biochem J 375: 313–321, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cavanaugh KJ, Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C1801–C1808, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cavanaugh KJ, Oswari J, Margulies SS. Role of stretch on tight junction structure in alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 25: 584–591, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cenni V, Sirri A, Riccio M, Lattanzi G, Santi S, de Pol A, Maraldi NM, Marmiroli S. Targeting of the Akt/PKB kinase to the actin skeleton. Cell Mol Life Sci 60: 2710–2720, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen H, Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR. Regulating actin-filament dynamics in vivo. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 19–23, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen Y, Merzdorf C, Paul DL, Goodenough DA. COOH terminus of occludin is required for tight junction barrier function in early Xenopus embryos. J Cell Biol 138: 891–899, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen TS, Gray Lawrence G, Khasgiwala A, Margulies SS. MAPK activation modulates permeability of isolated rat alveolar epithelial cell monolayers following cyclic stretch. PLoS One 5: e10385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Collins NT, Cummins PM, Colgan OC, Ferguson G, Birney YA, Murphy RP, Meade G, Cahill PA. Cyclic strain-mediated regulation of vascular endothelial occludin and ZO-1: influence on intercellular tight junction assembly and function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 62–68, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Reactivity of alveolar epithelial cells in primary culture with type I cell monoclonal antibodies. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 6: 296–306, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dimmeler S, Assmus B, Hermann C, Haendeler J, Zeiher AM. Fluid shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of Akt in human endothelial cells: involvement in suppression of apoptosis. Circ Res 83: 334–341, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. DiPaolo BC. Rac1-Mediated Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling and Monolayer Barrier Properties of Stretched Alveolar Epithelial Cells (PhD dissertation) Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24. DiPaolo BC, Lenormand G, Fredberg JJ, Margulies SS. Stretch magnitude and frequency-dependent actin cytoskeleton remodeling in alveolar epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C345–C353, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dipaolo BC, Margulies SS. Rho kinase signaling pathways during stretch in primary alveolar epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L992–L1002, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dittmer A, Dittmer J. Beta-actin is not a reliable loading control in Western blot analysis. Electrophoresis 27: 2844–2845, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat Cell Biol 1: 253–259, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eiseler T, Doppler H, Yan IK, Kitatani K, Mizuno K, Storz P. Protein kinase D1 regulates cofilin-mediated F-actin reorganization and cell motility through slingshot. Nat Cell Biol 11: 545–556, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, Nagafuchi A, Yonemura S, Tsukita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol 123: 1777–1788, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gassama-Diagne A, Yu W, ter Beest M, Martin-Belmonte F, Kierbel A, Engel J, Mostov K. Phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate regulates the formation of the basolateral plasma membrane in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol 8: 963–970, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gassmann M, Grenacher B, Rohde B, Vogel J. Quantifying Western blots: pitfalls of densitometry. Electrophoresis 30: 1845–1855, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hall A. Rho GTPases and the actin cytoskeleton. Science 279: 509–514, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hammerschmidt S, Kuhn H, Gessner C, Seyfarth HJ, Wirtz H. Stretch-induced alveolar type II cell apoptosis: role of endogenous bradykinin and PI3K-Akt signaling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 37: 699–705, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Heyworth PG, Robinson JM, Ding J, Ellis BA, Badwey JA. Cofilin undergoes rapid dephosphorylation in stimulated neutrophils and translocates to ruffled membranes enriched in products of the NADPH oxidase complex. Evidence for a novel cycle of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Histochem Cell Biol 108: 221–233, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Higuchi M, Masuyama N, Fukui Y, Suzuki A, Gotoh Y. Akt mediates Rac/Cdc42-regulated cell motility in growth factor-stimulated cells and in invasive PTEN knockout cells. Curr Biol 11: 1958–1962, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Innocenti M, Frittoli E, Ponzanelli I, Falck JR, Brachmann SM, Di Fiore PP, Scita G. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activates Rac by entering in a complex with Eps8, Abi1, and Sos-1. J Cell Biol 160: 17–23, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ishihara H, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Karaki H, Ozaki H, Kato Y, Fusetani N, Watabe S, Hashimoto K, Uemura D. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 159: 871–877, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kaplan-Albuquerque N, Garat C, Desseva C, Jones PL, Nemenoff RA. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB-mediated activation of Akt suppresses smooth muscle-specific gene expression through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase and redistribution of serum response factor. J Biol Chem 278: 39830–39838, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katsumi A, Milanini J, Kiosses WB, del Pozo MA, Kaunas R, Chien S, Hahn KM, Schwartz MA. Effects of cell tension on the small GTPase Rac. J Cell Biol 158: 153–164, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kawamura S, Miyamoto S, Brown JH. Initiation and transduction of stretch-induced RhoA and Rac1 activation through caveolae: cytoskeletal regulation of ERK translocation. J Biol Chem 278: 31111–31117, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Khwaja A, Rodriguez-Viciana P, Wennstrom S, Warne PH, Downward J. Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J 16: 2783–2793, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kolsch V, Charest PG, Firtel RA. The regulation of cell motility and chemotaxis by phospholipid signaling. J Cell Sci 121: 551–559, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kurita S, Gunji E, Ohashi K, Mizuno K. Actin filaments-stabilizing and -bundling activities of cofilin-phosphatase Slingshot-1. Genes Cells 12: 663–676, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Liu WF, Nelson CM, Pirone DM, Chen CS. E-cadherin engagement stimulates proliferation via Rac1. J Cell Biol 173: 431–441, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Liu WF, Nelson CM, Tan JL, Chen CS. Cadherins, RhoA, and Rac1 are differentially required for stretch-mediated proliferation in endothelial versus smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 101: e44–e52, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Liu XM, Ensenat D, Wang H, Schafer AI, Durante W. Physiologic cyclic stretch inhibits apoptosis in vascular endothelium. FEBS Lett 541: 52–56, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mohamed JS, Boriek AM. Stretch augments TGF-β1 expression through RhoA/ROCK1/2, PTK and PI3K in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: L413–L424, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nagumo Y, Han J, Bellila A, Isoda H, Tanaka T. Cofilin mediates tight-junction opening by redistributing actin and tight-junction proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377: 921–925, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac, and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and filopodia. Cell 81: 53–62, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nusrat A, Turner JR, Madara JL. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions. IV. Regulation of tight junctions by extracellular stimuli: nutrients, cytokines, and immune cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 279: G851–G857, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Onesto C, Shutes A, Picard V, Schweighoffer F, Der CJ. Characterization of EHT 1864, a novel small molecule inhibitor of Rac family small GTPases. Methods Enzymol 439: 111–129, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peng XQ, Damarla M, Skirball J, Nonas S, Wang XY, Han EJ, Hasan EJ, Cao X, Boueiz A, Damico R, Tuder RM, Sciuto AM, Anderson DR, Garcia JG, Kass DA, Hassoun PM, Zhang JT. Protective role of PI3-kinase/Akt/eNOS signaling in mechanical stress through inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in mouse lung. Acta Pharmacol Sin 31: 175–183, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Poh YC, Na S, Chowdhury F, Ouyang M, Wang Y, Wang N. Rapid activation of Rac GTPase in living cells by force is independent of Src. PLoS One 4: e7886, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Raptis L, Arulanandam R, Vultur A, Geletu M, Chevalier S, Feracci H. Beyond structure, to survival: activation of Stat3 by cadherin engagement. Biochem Cell Biol 87: 835–843, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70: 401–410, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Scita G, Tenca P, Frittoli E, Tocchetti A, Innocenti M, Giardina G, Di Fiore PP. Signaling from Ras to Rac and beyond: not just a matter of GEFs. EMBO J 19: 2393–2398, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Silbert O, Wang Y, Maciejewski BS, Lee HS, Shaw SK, Sanchez-Esteban J. Roles of RhoA and Rac1 on actin remodeling and cell alignment and differentiation in fetal type II epithelial cells exposed to cyclic mechanical stretch. Exp Lung Res 34: 663–680, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stroetz RW, Vlahakis NE, Walters BJ, Schroeder MA, Hubmayr RD. Validation of a new live cell strain system: characterization of plasma membrane stress failure. J Appl Physiol 90: 2361–2370, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sumi T, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Specific activation of LIM kinase 2 via phosphorylation of threonine 505 by ROCK, a Rho-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 276: 670–676, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Thelen M, Wymann MP, Langen H. Wortmannin binds specifically to 1-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase while inhibiting guanine nucleotide-binding protein-coupled receptor signaling in neutrophil leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 4960–4964, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tschumperlin DJ, Margulies SS. Equibiaxial deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L1173–L1183, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tschumperlin DJ, Oswari J, Margulies AS. Deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells. Effect of frequency, duration, and amplitude. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 357–362, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Turner JR, Angle JM, Black ED, Joyal JL, Sacks DB, Madara JL. PKC-dependent regulation of transepithelial resistance: roles of MLC and MLC kinase. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C554–C562, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Uhlig S. Ventilation-induced lung injury and mechanotransduction: stretching it too far? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L892–L896, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vartiainen M, Ojala PJ, Auvinen P, Peranen J, Lappalainen P. Mouse A6/twinfilin is an actin monomer-binding protein that localizes to the regions of rapid actin dynamics. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1772–1783, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Verma SK, Lal H, Golden HB, Gerilechaogetu F, Smith M, Guleria RS, Foster DM, Lu G, Dostal DE. Rac1 and RhoA differentially regulate angiotensinogen gene expression in stretched cardiac fibroblasts. Cardiovasc Res 90: 88–96, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vlahakis NE, Hubmayr RD. Invited review: plasma membrane stress failure in alveolar epithelial cells. J Appl Physiol 89: 2490–2496; discussion 2497, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wojciak-Stothard B, Potempa S, Eichholtz T, Ridley AJ. Rho and Rac but not Cdc42 regulate endothelial cell permeability. J Cell Sci 114: 1343–1355, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yang C, Liu Y, Leskow FC, Weaver VM, Kazanietz MG. Rac-GAP-dependent inhibition of breast cancer cell proliferation by β2-chimerin. J Biol Chem 280: 24363–24370, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yang N, Higuchi O, Ohashi K, Nagata K, Wada A, Kangawa K, Nishida E, Mizuno K. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature 393: 809–812, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999, p. 1 v (various pagings) [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zugasti O, Rul W, Roux P, Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A, Franke TF, Fort P, Hibner U. Raf-MEK-Erk cascade in anoikis is controlled by Rac1 and Cdc42 via Akt. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6706–6717, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]