Abstract

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is an evolutionally conserved intracellular process to maintain cellular homeostasis by facilitating the turnover of protein aggregates, cellular debris, and damaged organelles. During autophagy, cytosolic constituents are engulfed into double-membrane-bound vesicles called “autophagosomes,” which are subsequently delivered to the lysosome for degradation. Accumulated evidence suggests that autophagy is critically involved not only in the basal physiological states but also in the pathogenesis of various human diseases. Interestingly, a diverse variety of clinically approved drugs modulate autophagy to varying extents, although they are not currently utilized for the therapeutic purpose of manipulating autophagy. In this review, we highlight the functional roles of autophagy in lung diseases with focus on the recent progress of the potential therapeutic use of autophagy-modifying drugs in clinical medicine. The purpose of this review is to discuss the merits, and the pitfalls, of modulating autophagy as a therapeutic strategy in lung diseases.

Keywords: autophagy

in times of nutrient or oxygen scarcity, cells survive by eating and recycling part of themselves (73, 94). These cellular processes are collectively named “autophagy” (in Greek, “eating oneself”). Autophagy is a cellular self-degradation process in which cytosolic materials and organelles are sequestered and delivered to lysosome for degradation and recycling (73, 94). In addition to nutrient starvation, autophagy is induced by various physiological and pathological conditions. Importantly, autophagy is regulated in various human diseases such as cancer (120), metabolic diseases (e.g., obesity and Type 2 diabetes) (91), neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson disease) (122), and infectious diseases [e.g., human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis] (54, 60). These reports suggest that autophagy can serve as a potential therapeutic target for human diseases. Here, we summarize the pathophysiological roles of autophagy in lung disease, and we explore the possibility that modulating autophagy activity using a pharmacological approach can be a useful therapeutic intervention.

MOLECULAR MECHANISM OF AUTOPHAGY

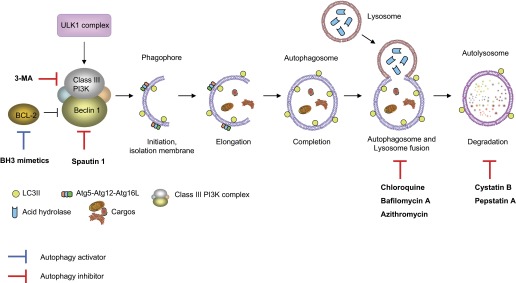

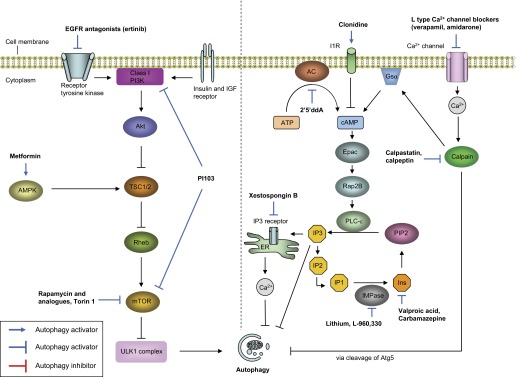

Autophagy encloses cytosolic materials by isolation membranes (phagophores) to form double membrane-bound vesicles called “autophagosomes” (Fig. 1). The isolation membranes are acquired from multiple sources including endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondrial outer membrane, and plasma membrane (35, 76, 93, 116). Subsequently, the autophagosome containing the cytosolic components and organelles fuses with the lysosome to become autolysosome, with subsequent degradation of cytosolic components (Fig. 1). More than 30 autophagy-related gene (Atg) proteins have been identified to be involved in autophagosome formation (73, 94). The activation of autophagy is mainly regulated by two signaling pathways including mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent and mTOR-independent pathways (94). In normal physiological condition, autophagy activity is regulated at basal level by activation of mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase that has diverse cellular functions. When cells encounter nutritional starvation, mTOR is inactivated and promotes the autophagosome formation (Fig. 2, left). In mTOR-independent pathways, Ca2+–calpain–Gsα and cyclic AMP (cAMP)–phospholipase Cε (PLCε)–inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3) pathways are involved in autophagy activation (Fig. 2, right).

Fig. 1.

Autophagy process and potential targets for modulating autophagy. Activation of UNC51-like kinase (ULK) complex in response to certain signals initiates isolation membrane and the formation of phagophore. (Upstream pathway of ULK1 complex is depicted in Fig. 2.) Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) complex composed of Beclin 1, class III PI3K, PIK3R4, and activating molecule in BECN1-regulated autophagy protein 1 (AMBRA1) is also required for the phagophore formation. The Atg-Atg12-Atg16L complex and LC3-II phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) conjugate promote the elongation and enwrap the cytosolic cargos including mitochondria, leading to the formation of autophagosome. Subsequently, lysosome fuses with the autophagosome (the formation of autolysosome) and releases acid hydrases into the interiors to degrade the cytosolic cargos. Autophagy can be activated by drugs such as BCL-2 homology 3 (BH3) mimetics that prevent the formation of autophagy inhibitory complex of Beclin 1 and BCL-2. In contrast, ubiquitin-mediated decrease of Beclin 1 protein by Spautin-1 and inhibition of class III PI3K by 3-methyladenine (3-MA) can inhibit autophagy. In addition, there are drugs to inhibit the late phase of autophagy process. Lysosomotropic agents that enhance lysosomal pH such as chloroquine inhibit lysosomal enzymes and also prevent the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome, resulting in inhibition of autophagy. Bafilomycin A1 inhibits the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome by inhibiting vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase) located in the lysosomal membrane. Compounds such as pepstatin A and cystatin B are inhibitors for lysosomal protease. (Please also see Table 4.)

Fig. 2.

Overview of the regulation of autophagy pathways and targets for modulating autophagy by drugs/compounds. Two major signaling pathways to regulate autophagy are depicted in this figure: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways and mTOR-independent signaling pathways. Autophagy is modulated by mTOR in response to certain nutritional stimulations. Insulin or growth factors activate class I PI3K pathway, leading to activation of mTOR and inhibition of autophagy. Glucose starvation activates AMPK and inhibits mTOR, followed by activating of ULK1 complex and activating autophagy. mTOR can be pharmacologically inhibited by activating AMPK (e.g., metformin) or inhibiting class I PI3K (e.g., EGFR antagonist). Recent new drugs such as PI-103 can activate autophagy by inhibiting both class I PI3K and mTOR. In the mTOR-independent pathway, increase of intracellular cAMP level and Ca2+ inhibits autophagy. Intracellular level of cAMP is upregulated by adenylyl cyclase (AC) and the calpain-Gsα pathway, which is activated by intracellular Ca2+ level. The inhibitory effect of cAMP on autophagy is mediated by increase of synthesis of inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate (IP3) and inositol. Increased level of IP3 activates IP3 receptor in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and release Ca2+ into cytosol, leading to inhibition of autophagy. Activation of L-type Ca2+ channel triggers Ca2+ influx and elevates intracellular Ca2+ level, which activates cysteine protease called calpain. In addition to elevating cAMP by the calpain-Gsα pathway, calpain inhibits autophagy by cleavage of Atg5. However, the concise mechanism by which cytosolic cAMP, Ca2+, inositol, and IP3 regulate autophagy is still unclear. In this cyclical mTOR-independent pathway, autophagy can be modulated by mainly targeting intracellular levels of cAMP or Ca2+. L-type Ca2+ receptor blockers such as verapamil inhibit Ca2+ influx, which leads inhibition of calpain activity and cAMP synthesis. Activation of autophagy by drugs such as lithium or carbamazepine is mediated by at least reduction of Ca2+ release by IP3 receptor (IP3R). EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; IGF, insulin-like growth; TSC, tuberous sclerosis 2; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; V-ATPase, vacuolar ATPase; I1R, imidazoline-1 receptor; PLCε, phospholipase C epsilon; 2′5′ddA, 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; cAMP, cyclic AMP; Ins, inositol; IP2, inositol-(1,4)-bisphosphate; IP3, Inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate; IMPase, inositol monophosphatase.

FUNCTION OF AUTOPHAGY

Whereas autophagy nonselectively engulfs and degrades intracellular proteins for recycling under nutritional starvation, autophagy can selectively target and remove specific subcellular components (selective autophagy) (18). This selective degradation pathway includes eliminating invading pathogens (xenophagy) (60), dysfunctional cellular organelles such as mitochondria (mitophagy) (126), and polyubiquitinated protein aggregates (aggrephagy) (56). Autophagy is also involved in lipid metabolism (lipophagy) (108). Selective autophagy plays important roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis in basal physiological states and in response to various cellular stresses.

Cytoprotective roles of autophagy under stress conditions such as starvation have been well documented (73). However, when cells receive lethal signals, the cellular stresses cause autophagy and also cell death including apoptosis. Although interactions of autophagy- and apoptosis-related molecules such as Beclin 1 and B cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), or LC3B and Fas have been reported in various models (16, 87), it is still unclear whether autophagy induced by lethal signals promotes cell death or is an independent process from cell death (94). The functional role of autophagy on cell death is likely to be dependent on stress models.

Against invading microbes, autophagy actively participates in innate immune responses (54, 60). For example, autophagy exerts its host defense role by degrading various pathogens by lysosomal system (xenophagy) (60). The target pathogens include bacteria, such as group A Streptococcus pyrogen (60), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) (23), Salmonella enterica (54), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (127); viruses such as herpes simplex virus 1 (54, 60); and parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii (54). In contrast, recent studies also suggest that autophagy machinery contributes to the replication and survival of microbes in the host cells. The list of pathogens exploiting autophagy machinery includes clinically important microbes, e.g., bacterial agents such as Brucella abortus (99) and Coxiella burnetii (99) and viruses such as HIV (99), hepatitis B virus (HBV) (54, 99), and avian influenza A H5N1 (H5N1) (109). Of note, autophagy exerts both killing and prosurvival properties for HIV (60, 99). Autophagy has diverse effects on both innate and adaptive immune systems (54, 60). Atg5 is involved with the production of type I interferons in response to single-stranded RNA viruses (54, 60). Autophagy proteins are also involved in the regulation of inflammasome, cytosolic multiprotein complexes responsible for activation of caspase-1 and its downstream signaling including secretion of IL-1β and IL-18 (20, 79). Beclin 1 and LC3B negatively regulate inflammasome activation by preserving mitochondrial homeostasis (79). The roles of autophagy in adaptive immunity include antigen presentation and antibody production. Autophagy is required for presenting antigen on both major histocompatibility complex class I and II molecules and activating CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes, respectively (60). Autophagy is also required for B cell differentiation (19) and for sustainable antibody production in plasma cells (88). Thus autophagy plays crucial diverse roles in immune systems including pathogen degradation and immune signaling, suggesting that the involvement of autophagy in infectious and inflammatory diseases.

Autophagy is critically involved in various metabolic pathways for maintaining cellular homeostasis (91). For example, autophagy is an important energy generator in the liver. Mice with specific deletion of atg7 gene in liver display decreased level of blood glucose and amino acids after starvation (25). Autophagy is also involved in lipid metabolism by breaking down lipid droplets to generate energy (lipophagy) (108). Metabolome analysis also suggests autophagy is required for maintenance of tricarboxylic acid cycle-related metabolites (33), suggesting that autophagy is involved in the quality control of mitochondria. Damaged mitochondria are selectively targeted and removed by autophagy to maintain normal mitochondrial function (mitophagy) (126). Although the concise molecular mechanism of mitophagy is still unclear, the importance of preserving mitochondrial homeostasis by autophagy is now further linked to the pathogenesis of human diseases such as Parkinson disease (68, 80, 81, 118). Thus the autophagy process is critically involved in not only physiological but also pathological metabolic responses.

MEASUREMENT OF AUTOPHAGY

As the research of autophagy continues to evolve, methods for monitoring autophagy have been evaluated and discussed in detail. Klionsky et al. (51) have recently reported the guideline for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes and described useful methods and how to interpret the data. A key tenet to emphasize is that investigators need to recognize whether they are evaluating the steady-state levels of autophagosomes or dynamic state of autophagy generated by their models (51, 101). If they are seeking to assess the change of autophagy flux or activity (e.g., the rate of delivery of autophagosomes substrate to lysosomes) in certain points, it is likely that monitoring steady state of autophagosome (e.g., measuring LC3-II expression without examining turnover by Western blot, counting autophagosomes by using electron microscopy, or counting puncta formation of LC3 by immunofluorescence microscopy) is not sufficient. Table 1 demonstrates the various methods to monitor autophagy both in vitro and in vivo. Generally, it is recommended to use multiple different assays (ideally for both steady and dynamic states), rather than relying on the results from a single method (51, 101).

Table 1.

Methods for monitoring autophagy in vitro and in vivo

| Methods | Key Points | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monitoring static state autophagy | |||

| Quantifying autophagosomes | Electron microscopy | ∙ Positive correlation of elevated number of autophagosomes and increased autophagy flux has not been proved reliably in all models. | 110 |

| LC3-II level (ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I) | Western blot | ∙ Increased level of LC3-II (ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I) does not always correlate with autophagy flux. | 75 |

| Puncta formation of LC3 | Immunofluorescence microscopy | ∙ This method can be applied to in vivo using GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. | 72, 74 |

| ∙ Increased puncta formation of LC3 does not reliably correlate with autophagic flux. | |||

| Monitoring dynamic state autophagy | |||

| Turnover of LC3-II | Western blot | ∙ LC3-II on the autophagosome membrane is normally continuously degraded during autophagy process. LC3-II can be accumulated by adding lysosomal proteolysis inhibitors such as leupeptin, chloroquine or bafilomycin. | 38, 41 |

| ∙ Cells or animals can be treated with lysosomal protease inhibitors. | |||

| ∙ Autophagic flux can be expressed as the difference in LC3B-II signal on Western blot obtained in the presence or absence of lysosome protein inhibitors. | |||

| Turnover of p62/SQSTMI | Western blot | ∙ P62/SQSTMI is a cytosolic protein that has an LC3 binding domain (REF). It binds to ubiquitinated protein and carry them to autophagosome. Subsequently, both p62/SQSTMI and the cargo proteins are degraded by autophagy. | 10, 38 |

| ∙ Similar with LC3-II, p62/SQSTMI turnover can be measured by adding lysosome protease inhibitors in vitro or in vivo. | |||

| Cytosolic protein sequestration assays | Western blot | ∙ Cells are incubated (or animals are intraperitoneally administered) with leupeptin to inhibit lysosomal proteolysis. Autophagosomes are purified via mechanical disruption (34) followed by density centrifugation. Autophagy flux is expressed by the amount of cytosolic protein, such as LDH recovered in the autophagosome fraction (Western blot). | 38, 52, 106 |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

AUTOPHAGY PATHWAY: POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC TARGET FOR LUNG DISEASES

Autophagy in Models of Human Lung Diseases

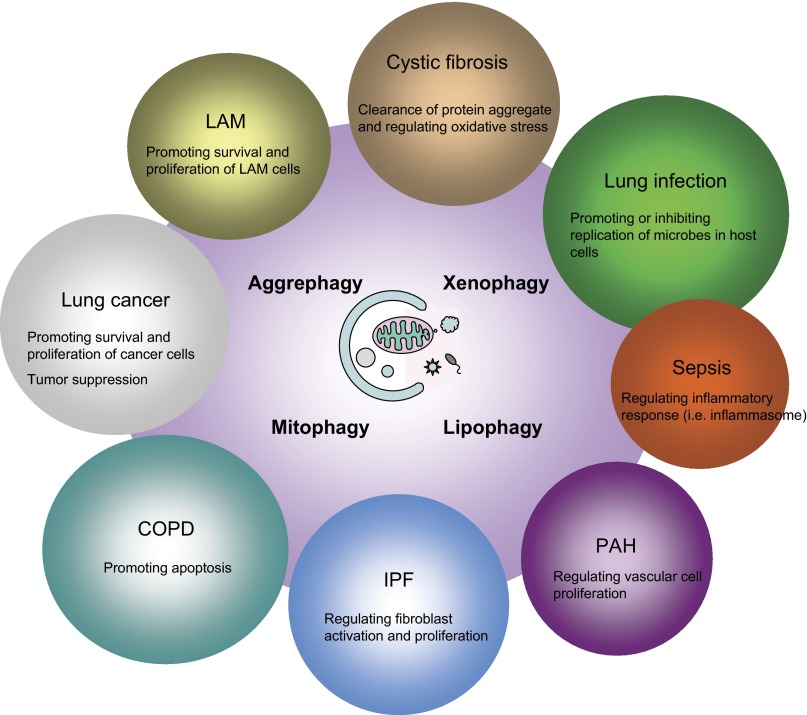

The functional roles of autophagy on various lung diseases have been studied both in vitro and in vivo. Tables 2 and 3 represent the functions of autophagy or autophagic proteins in lung diseases on the basis of studies using genetic or biochemical perturbation of autophagy. Although autophagy has been initially thought as a cytoprotective response in pathophysiological states, accumulating data reveal diverse functions of autophagy in lung diseases (Tables 2 and 3). For example, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one lung disease that has been shown to be associated with autophagy (15). Increased number of autophagosomes is observed by electron microscopy analysis, and expression of autophagic protein LC3B-II is increased in lung tissues from patients with COPD (15). Several molecules involved in autophagy-mediated COPD include FAS (16), Toll-like receptor 4 (5), and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) (11). In addition, alveolar macrophages isolated from smokers show increased of LC3 expression with defect of autophagy flux (77). In vivo, genetic deletion of LC3B displays resistance to cigarette smoke-induced airway space enlargement compared with the control mice (16). Similar adverse effects of autophagy are observed in other lung diseases including lung cancer (36, 46, 53) and acute lung injury induced by H5N1 infection (109). In contrast, the beneficial roles of autophagy are also observed in the diseases such as cystic fibrosis (CF) (1, 2, 65), tuberculosis (23, 34, 42), and sepsis (14, 40, 45, 64, 79). Thus autophagy is an important cellular process to regulate or contribute to the pathogenesis of lung diseases. Importantly, Fig. 3 demonstrates specificity of the pathophysiological functions of autophagy in each lung disease, resulting in either favorable or deleterious phenotype depending in the disease process.

Table 2.

The functional role of autophagic proteins in experimental models of lung diseases

| Lung Diseases | Function of Autophagic Proteins | References |

|---|---|---|

| COPD | ∙ LC3B and Beclin 1 deficiency inhibits CSE-induced cell death in pulmonary epithelial cells. | 15, 16, 47 |

| LC3B-deficient mice display inhibition of airspace enlargement and apoptosis in lungs after cigarette smoke exposure. | ||

| ∙ LC3 deficiency promotes CSE-induced IL-8 secretion in HBEC. | 28 | |

| Autophagy inhibition by bafilomycin A enhances CSE-induced IL-8 secretion in HBEC. | ||

| IPF | ∙ Autophagy activation by rapamycin inhibits IL-17A-induced collagen production in lung epithelial cells. | 71 |

| Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA suppresses degradation of collagen in epithelial cells. | ||

| 3-MA reverses the therapeutic effect of IL-17 antagonism on bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis and mortality of mice. | ||

| ∙ LC3B and Beclin 1 deficiency promotes TGF-β-induced activation of lung fibroblast in vitro. | 85 | |

| Autophagy activation by rapamycin inhibits TGF-β-induced fibronectin and α-SMA expression in lung fibroblast. | ||

| Rapamycin inhibits bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. | ||

| ∙ Rapamycin inhibits anti-TLR4 antibody-induced lung fibrosis in mice. | 124 | |

| ∙ Atg5 and LC3 deficiency promotes TGF-β-induced fibroblast activation in vitro. | 7 | |

| Inhibition of mTOR by Torin1 inhibits tunicamycin (ER stress inducer)-induced senescence in HBEC. | ||

| Atg5 and LC3 deficiency promotes tunicamycin-induced senescence in HBEC. | ||

| PH (PAH) | ∙ LC3B deficiency promotes hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice. | 59 |

| LC3B deficiency promotes cell proliferation in pulmonary artery endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells. | ||

| ∙ Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA and chloroquine increase angiogenesis in PAEC from fetal lambs with persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN-PAEC). | 114 | |

| ∙ Beclin-1 knockdown promotes angiogenesis in PPHN-PAEC. | ||

| CF | ∙ Beclin 1 deficiency promotes aggresome accumulation in CF epithelia. | 65 |

| Beclin 1 deficiency promotes macrophage infiltration and MPO activity in nasal mucosa of CF. | ||

| Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA abrogates CF phenotype in nasal mucosa. | ||

| ∙ LC3 deficiency promotes growth of B. cepacia and IL-1β secretion in macrophages. | 1 | |

| Autophagy activation by rapamycin inhibits growth of B. cepacia and IL-1β secretion in macrophages. | ||

| Autophagy activation reduces bacterial burden of lung and inflammation in lung of CF mice after B. cepacia infection. | ||

| ∙ Overexpression of SQSTM1/p62 inhibits intracellular survival of B. cepacia in macrophages. | 2 | |

| Deficiency of SQSTM1/p62 promotes intracellular survival of B. cepacia in macrophages. | ||

| Lung cancer | ∙ Blocking chaperone-mediated autophagy by LAMP-2A depletion suppresses cell proliferation and increases cell death in lung cancer cells. | 53 |

| Injection of lung cancer cells with LAMP-2A deficiency reduces tumor formation in xenograft mouse model. | ||

| ∙ Autophagy inhibition by chloroquine enhances cytotoxicity of gefinitib and erlotinib in lung cancer cells. | 36 | |

| Atg5 and Atg7 deficiency enhances cytotoxicity of gefinitib and erlotinib in lung cancer cells. | ||

| ∙ Atg7 deficiency reduces cancer cell proliferation in NSCLC cell lines. | 46 | |

| Atg7 deficiency sensitizes the cancer cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis in NSCLC cell lines. | ||

| ∙ Atg3 deficiency reverses erlotinib resistance in erlotinib-resistant lung cancer cells. | 57 | |

| LAM | ∙ TSC2 knockdown increases autophagy-dependent cell survival in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. | 84 |

| Atg5 deficiency inhibits TSC2-null xenograft tumor cell survival. | ||

| Autophagy inhibition by chloroquine inhibits xenograft tumor size in mice of TSC2-null xenograft tumor. | ||

| HALI | ∙ LC3B knockdown promotes hyperoxia-induced cell death in lung epithelial cells. | 112 |

| Sepsis | ∙ Depletion of LC3B and Beclin 1 leads mitochondrial dysfunction and enhances NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated IL-1β and IL-18 secretion in macrophages. | 79 |

| LC3B knockdown increases serum level of IL-1β and IL-18 production in CLP-induced polymicrobial sepsis and sensitizes mice to endotoxic shock. | ||

| ∙ Autophagy activation by rapamycin restores CLP-induced myocardial dysfunction in mice. | 40 | |

| ∙ LC3 overexpression ameliorates acute lung injury and survival in CLP-induced polymicrobial model of sepsis. | 64 | |

| ∙ Knockdown of VPS34 increases cell death and liver injury in CLP-induced polymicrobial models of sepsis. | 14 | |

| ∙ Autophagy inhibition suppresses releases of neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) induced by E. coli in human neutrophils. | 45 | |

| Nanoparticle-induced ALI | ∙ Knockdown of Atg6 improves nanoparticle-induced cell death in lung epithelial cells. | 61, 62 |

| Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA ameliorates nanoparticle-induced ALI in mice. |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CSE, cigarette smoke extract; HBEC, human bronchial epithelial cells; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin; 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; TLR4, Toll-like receptor 4; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; P(A)H, pulmonary (artery) hypertension; PAEC, pulmonary artery endothelial cells; CF, cystic fibrosis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; B. cepacia, Burkholderia cenocepacia; NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung cancer; LAMP2, lysosome-associated membrane protein 2; LAM, Lymphangioleiomyomatosis; TSC, tuberous sclerosis; HALI, hyperoxia-induced acute lung injury; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3; CLP, cecal ligation and puncture; E. coli, Escherichia coli; ALI, acute lung injury.

Table 3.

The functional role of autophagic proteins on pathogen(s) causing respiratory tract infection

| Pathogens | Role of Autophagy or Autophagic Proteins | References |

|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) | ∙ Autophagy induction by rapamycin or starvation inhibits M. tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. | 34 |

| ∙ IL-4 and IL-13 inhibit autophagy activation and autophagy-mediated killing of intracellular M. tuberculosis in macrophages. | 37 | |

| ∙ Autophagy activation by rapamycin enhances presentation of mycobacterial antigen in macrophages. | 42 | |

| Subcutaneous injection of mycobacteria-infected dendritic cells pretreated with rapamycin enhances Th1 response and increases vaccine efficacy in mice. | ||

| ∙ Autophagy induction by Vitamin D3 promotes killing of M. tuberculosis. | 128 | |

| ∙ Isoniazid-induced autophagy is associated with antimicrobial activity in M. tuberculosis-infected macrophages. | 49 | |

| Avian influenza A H5N1 | ∙ Knockdown of Atg5 and TSC2 inhibits H5N1-induced cell death in lung epithelial cells. | 109 |

| Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA ameliorates acute lung injury and mice survival rate in mice infected with H5N1 | ||

| Knockdown of Atg5 ameliorates acute lung injury and mice survival rate in mice infected with H5N1. | ||

| P. aeruginosa | ∙ Autophagy induction by rapamycin promotes P. aeruginosa clearance and autophagy inhibition by 3-MA inhibits the bacterial clearances in macrophages. | 127 |

| Knockdown of Beclin 1 inhibits P. aeruginosa clearance in macrophages. | ||

| M. abscessus | ∙ Autophagy inhibition by Azithromycin inhibits intracellular killing of M. abscessus in macrophages. | 96 |

| Autophagy inhibition by Azithromycin promotes M. abscessus infection in mice. | ||

| Human rhinovirus 2 | ∙ Autophagy activation by rapamycin increases replication of human rhinovirus 2 (HRV-2). | 50 |

| ∙ Autophagy inhibition by 3-MA suppresses replication of HRV-2. | ||

| Human adenovirus type 5 | ∙ Knockdown of Atg5 inhibits human adenovirus-mediated cell lysis. | 44 |

| S. aureus | ∙ Knockdown of Atg5 inhibits replication of S. aureus and S. aureus-mediated cell death. | 105 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus | ∙ Knockdown of Beclin 1 or LC3 attenuates respiratory syncytial virus-induced proinflammatory cytokines production. | 78 |

M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; M. abscessus, Mycobacterium abscessus; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus.

Fig. 3.

Diverse effects of autophagy in lung diseases. The functional modes of autophagy at cellular levels include eliminating intracellular microbes (xenophagy), dysfunctional mitochondria (mitophagy), and protein aggregate (aggrephagy). Autophagy also regulates lipid metabolism (lipophagy). Autophagy is involved in pathogenesis of various lung diseases. The roles of autophagy in each disease are shown. In lung cancer, autophagy may prevent tumorigenesis, whereas autophagy can promote survival and proliferation of tumor cells. In infectious diseases, the roles of autophagy are dependent on microbes. Autophagy may promote bacterial killing and inhibit intracellular survival of microbes such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. On the other hand, autophagy may promote replication and survival of microbes such as H5N1.

Autophagy in Clinical Trials

Although drugs modulating autophagy such as rapamycin or chloroquine have been clinically used for years without the intent to modulate autophagy activity, these drugs are now studied as autophagy modulators in clinical trials for lung diseases (17, 99, 120, 125). For example, chloroquine, which inhibits autophagy-mediated cell survival in tumor cells, is used as an intervention for patients with small cell lung cancer in a clinical trial (phase 1). In addition, the interventions using hydrochloroquine and other anticancer drugs such as erlotinib are used for non-small cell lung cancer in two clinical trials (phase 1/2 and 2) (125). Although autophagy has been initially shown to be associated with anti-tumorigenesis in rodent animal studies (90, 111), the current strategy for cancer therapy is more likely to be based on inhibition of autophagy (17, 120, 125).

This paradox may be due to the differential roles of autophagy in different stages of tumorigenesis (99, 120). Although initiation of tumorigenesis in normal cells is associated with defect of autophagy, autophagy subsequently may exert prosurvival effect in tumor cells (99, 120). Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a progressive lung disease caused by mutation in the tuberous sclerosis genes (tsc), is associated with inappropriate activation of mTOR signaling, which regulates cellular growth and lymphangiogenesis (39). The pathogenesis of LAM is in part similar with those of tumorigenesis including inappropriate cell growth and survival (39). Chloroquine is also used with rapamycin for patients with LAM (phase 1). This clinical trial is based on the rationale that rapamycin blocks mTOR of downstream kinases and restores homeostasis in cells with defective tsc function (39, 69, 84). The use of chloroquine aims to inhibit autophagy-mediated survival of LAM cells induced by rapamycin (39, 84). A recent clinical study concludes chloroquine does not prevent infection with influenza including H1N1 strain (86). Interestingly, autophagy is involved in infection with H5N1, rather than H1N1 (109). Therefore, it is possible that chloroquine has a differential effect on infection with H5N1 vs. H1N1, with genetic and biochemical inhibition of autophagy rescue in mice infected with H5N1 (109). Since chloroquine also has autophagy-independent pharmacological effects such as anti-inflammatory property, the effect of chloroquine on diseases including tumor may not be entirely explained by modulating autophagy (120). Although further studies are needed to evaluate the off-target effects of chloroquine on diseases, these reports suggest that autophagy modulation by clinically used drugs may be more accessible to study in clinical trials because of their favorable safety profiles. The details of ongoing clinical trial targeting modulating autophagy are listed (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=autophagy&Search=Search).

Autophagy Modulators

Given the important association between autophagy and human lung diseases, it is worthwhile to review whether modulating autophagy can serve as potent therapeutic targets for various lung diseases. Table 4 demonstrates a list of autophagy modulating drugs that are clinically used or being studied in clinical trials. Table 5 shows conventional and newly developed compounds or molecules modulating autophagy activity. There are several target signaling pathways wherein autophagy activity is modulated by drugs.

Table 4.

Drugs that modulate autophagy activity

| Drugs | Clinical Application or Pharmacological Class | Mechanism of Action in Autophagy Pathway | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Autophagy inducers | |||

| Rapamycin and analogs | Immunosuppressant for preventing rejection in organ transplant and coronary stent coating for anti-proliferation | Inhibit mTORC1 | 92, 95, 121 |

| Amidarone | Class III antiarrhytmic | Inhibits mTORC1 or upstream in mTOR pathway | 9 |

| Nicosamide | Antiparasitic | Inhibits mTORC1 or upstream in mTOR pathway | 9 |

| EGFR antagonists (erltinib hydrochlorine) | Anticancer | Inhibit PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway | 30, 36 |

| Resveratrol (Stilbenoids) | Supplementary diet. Secondary products of heartwood formation in trees that act as phytoalexins | Activates sirtuin 1 (histone deacetylase) and inhibits S6 kinase | 8, 43, 82 |

| Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid | Anticutaneous T cell lymphoma | Inhibits mTOR | 13 |

| Dexamethasone (glucocorticoide) | Anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant | Upregulates PML and Akt dephosphorylation | 31, 55 |

| Metformin | Antidiabetic | Upregulates AMPK (and ULK1 phosphorylation) | 48, 70 |

| Verapamil, nicardipine, nimodipine (L-type Ca2+ channel blockers) | Vasodilator | Reduce intracellular Ca2+ levels | 9, 121, 129 |

| Sodium valproate | Anticonvulsant | Inhibits histone deacetylase and reduces intracellular Ca2+ levels | 103, 121 |

| Clonidine | Antihypertensive, treatment for ADHD and anxiety/panic disorder | Reduces cAMP levels (Imidazoline-1 receptor agonist) | 121 |

| Rilmenidine | Antihypertensive | Reduces cAMP levels (imidazoline-1 receptor agonist) | 98, 121 |

| Lithium, L-690 330 | Mood-stabilizing drug | Inhibit IMPase and reduce inositol and IP3 levels | 103 |

| Carbamazepine | Antiepileptics | Reduces inositol and IP3 levels | 103, 121 |

| Tamoxifen (estrogen receptor antagonist) | Anti-breast cancer and anti-bipolar disorder | Accumulation of sterol, Increases Beclin 1 | 21, 99 |

| Statin (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor) | Lower cholesterol | Depletes geranylgeranyl diphosphate | 83 |

| Vitamin D3 | Supplementary diet to reduce the risk of fractures and falls | Increases Beclin 1 expression by upregulating cathelicidin | 128 |

| BH3 mimetics (ABT-737) | Undergoing clinical trial for ovarian cancer | Disrupts interaction between the BH3 domain of Beclin 1 and the antiapoptotic proteins BCL-2 | 66 |

| Carbon monoxide (at 250 ppm) | Vasodilator, anti-inflammation and antiproliferation Undergoing clinical trials for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sepsis | Increases mitochondrial reactive oxygen species | 58 |

| Minoxidil (potassium channel opener) | Vasodilator | Unknown | 121 |

| Salbutamol (β2 adrenergic receptor agonist) | Treatment for asthma by smooth muscle relaxant | Unknown | 6 |

| Isoniazid, pyrazinamide | Antibiotics for tuberculosis | AMPK and intracellular Ca2+ dependent | 49 |

| Autophagy inhibitors | |||

| Azithromycin | Macrolide antibiotic | Inhibits fusion of autophagosome and lysosome | 96 |

| Chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine | Treatment for RA, SLE, and malaria Undergoing clinical trials for various cancers | Inhibits fusion of autophagosome and lysosome | 4, 12 |

| Vinblastine | Anticancer | Inhibits microtubule formation | 89 |

| IL-4 | Undergoing clinical trial for tuberculosis by blocking IL-4 | Activates Akt and STAT6 | 37 |

| IL-13 | Undergoing clinical trial for advanced cancers | Activates Akt and STAT6 | 37 |

mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; mTORC1, mTOR complex 1; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB, AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase: ULK1, UNC51-like kinase; cAMP, cyclic AMP; IP3, inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate; IMPase, inositol monophosphatase; BH3, BCL-2 homology 3; BCL-2, B cell lymphoma 2; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A; STAT6, signal transduction and transcription 6; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; PML, promyelocytic leukemia protein; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; IL-4, interleukin 4; IL-13, interleukin 13. For details of clinical trials, please see the website http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/.

Table 5.

Molecules or compounds that modulate autophagy activity

| Molecules or Compounds | Mechanism of Action in Autophagy Pathway | References |

|---|---|---|

| Autophagy activators | ||

| Torin1 | Directly inhibits both mTORC1 and mTORC2 | 115 |

| PP242 | Inhibits mTORC1 | 26 |

| PI103 hydrochloride | Highly selective class I PI3K inhibitor and ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitor | 22 |

| 2′,5′- Dideoxyadenosine | Reduces cAMP levels (Adenynyl cyclase inhibitor) | 121 |

| Xestospongin B | IP3R antagonist | 117 |

| Spermidine | Postulated to affect expression of Atg genes | 24 |

| Tat-beclin1 | A cell permeable peptide derived from a region (267–284) of Beclin 1 | 107 |

| Calpastatin, calpeptin | Inhibit calpain | 121 |

| Trehalose (an α-linked disaccharide | mTOR independent | 102 |

| l-NAME (inhibition of NOS and decrease of NO production) | Unknown | 104 |

| GGTi-298 (inhibition of geranylgeranyl transferase 1) | P53 dependent | 29 |

| Autophagy inhibitors | ||

| Spautin-1 | Lowers Beclin 1 levels by promoting its ubiquitination | 63 |

| 3-MA | Inhibits class III PI3K | 100 |

| Pepstatin A | Inhibits aspartyl protease (cathepsin D) | 113 |

| Cystatin B | Inhibits cystatine protease (cathepsin B) | 99 |

| Leupeptin | Inhibits serine and cysteine proteases | 38 |

| Bafilomycin A1 | Inhibits V-ATPase; Inhibits fusion of autophagosome and lysosome | 92, 123 |

| Nocodazole | Inhibits microtubule formation | 97, 119 |

IP3R, inositol-(1,4,5)-trisphosphate receptor; L-NAME, N-l-arginine methyl ester; 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; Atg, autophagy-related; V-ATPase, vacuolar ATPase.

mTOR signaling pathways.

The mTOR is one of the main targets for modulating autophagy by drugs and forms two distinct complexes to regulate autophagy: mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) and mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) (94) (Fig. 2, left). Rapamycin and its analogs inhibit mTORC1, a main complex responsible for autophagy regulation, and promote autophagy induction (92, 95, 121). A recently identified compound Torin1 directly inhibits both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and induces greater autophagy than does rapamycin (115). Of note, another new class of drugs has dual targets in autophagy pathways. PI-103 hydrochloride inhibits both mTOR and class I phosphoinositide 3-kinase (class I PI3K), suggesting an effective autophagy inducer (22).

mTOR-independent pathways.

Figure 2, right, shows mTOR-independent pathways.

phosphoinositol signaling pathway.

Intracellular inositol and IP3 levels negatively regulate autophagy (94). Drugs such as lithium (103) or carbamazepine (103, 121) increase autophagy activity by decreasing intracellular level of inositol.

ca2+-camp-plcε-ip3 pathway.

Intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP negatively regulate autophagy by increasing intracellular inositol level (94). In addition, calpain activated by elevated level of intracellular Ca2+ inhibits autophagy by cleavage of Atg5 (94, 99). Antihypertensive drugs including Ca2+ receptor blockers (9, 121, 129) or imidazolin receptor agonists (98, 121) induce autophagy by decreasing cAMP.

Degradation steps of autophagy.

Inhibiting formation of autolysosome and lysosomal protease are also important targets to inhibit autophagy (Fig. 1). Chloroquine is a lysosomotropic and inhibits the fusion of autophagosome and lysosome (4, 12). Cystatin B is a potent inhibitor of cystatin protease (cathepsin B) in lysosome (99).

Other pathways.

BCL-2 homology 3 (BH3) mimics inhibit the interaction of BCL-2 and BCL-x with Beclin 1, an inhibitory complex for autophagy (66) (Fig. 1). Resveratrol induces autophagy by activating sirtuin 1 and inhibits P70 S6 kinase (8, 43, 82). There are several compounds or drugs such as l-NAME (104), trehalose (102), or β2-adrenergic receptor agonist (6) whose mechanisms to modulate autophagy are still unclear (Table 4). Further studies will be needed to identify concise pathways by which those drugs or compounds modulate autophagy.

Since there are several pathways regulating autophagy, it is possible that some drugs can stimulate both proautophagy and antiautophagy pathways. For example, although lithium has been shown to activate autophagy via an mTOR-independent pathway, lithium also inhibits GSK-3β, which can activate mTOR and lead to inhibition of autophagy (27) (Fig. 2). In addition, some drugs may inhibit Ca2+ channel (activating autophagy by mTOR-independent pathways) and also inhibit EGFR receptor (inhibiting autophagy by activating mTOR), which offset both the cellular signaling pathways against each other and result in no autophagy activation being observed. Thus it is also important to analyze the effect of drugs on the individual pathways to regulate autophagy. These profiles may lead to developing the combined use of different types of autophagy modulators such as lithium and rapamycin, which can gain the greater activation of autophagy (27) (Fig. 2).

Autophagy Modulation as a Potential Therapeutic Intervention for Lung Diseases

Although various classes of clinically used drug modulate autophagy pathways (Table 4), it is still unclear in many cases whether the therapeutic effects of those drugs arise from autophagy or autophagy-independent pathways. Even if autophagy is involved, there is still an important question remaining whether modulating autophagy by drugs contributes to their beneficial pharmacological effects. For example, metformin, one of the most commonly used drugs for treatment of Type 2 diabetes, induces autophagy (48, 70). The role of autophagy on the pathogenesis of diabetes is still controversial (94). Antidiabetic effects of metformin may be mediated by metformin-induced autophagy activation or conversely may be compromised by the autophagy activation. Recent clinical studies show new possible interventions using drugs for lung diseases including COPD (3) and tuberculosis (67). Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, inhibits the frequency of exacerbation of COPD (3). High-dose supplement of vitamin D3 (VitD3) reduces time of sputum culture conversion of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mbt) in patients with polymorphism of VitD3 receptor (67). Although the concise mechanisms by which these drugs exert the beneficial effects are still unclear, they commonly modulate autophagy activity. The pharmacological effect of azithromycin is similar with bafilomycin A1, a family of macrolide antibiotic and also a well-known autophagy inhibitor (96) (Fig. 1). The beneficial roles of azithromycin on COPD may be associated with the inhibitory effect of azithromycin on autophagy, since autophagy gene deficiency displays protective effects in a mouse model of COPD. In contrast, VitD3 inhibits replication of Mbt by increasing autophagy activity (128). Interestingly, drugs can also increase autophagy activity in specific pathological condition. Isoniazid, an antibiotic for Mbt, induces autophagy in macrophages infected with Mbt, rather than in uninfected cells (49). Although further studies are needed to clarify how autophagy is involved in the beneficial effects of those drugs, these reports suggest that pharmacological manipulation on autophagy activity can serve as a potential therapeutic strategy in lung diseases. In addition, investigating the effect of drugs on autophagy activity can reveal the new mechanism of disease pathogenesis and previously unknown pharmacological actions of the drugs.

It is also important to explore the possibility to use autophagy modulators as an intervention for treatment of lung diseases. For example, an intervention to enhance autophagy activity may have beneficial effects in lung diseases such as tuberculosis or CF, since the effective drugs reported for those diseases activate autophagy (32, 67). However, the caution should be taken for this strategy. Autophagy has diverse effects depending on diseases or pathological conditions. Although activation of autophagy is beneficial for Mbt infection, the activated autophagy may also exert protective roles for microbes such as HIV or HBV (99). If patients with tuberculosis have latent infections with HIV or HBV, it is possible that autophagy activation promotes replication and survival of those microbes in the patients (99). On the other hand, autophagy inducers may have the additive beneficial effects in patients enrolled in clinical trials for treatment of tuberculosis, such as patients with Parkinson disease, where autophagy plays protective roles (99). Finally, therapeutic interventions by modulating autophagy can add to the current therapeutic strategies, rather than be used solely. For example, a recent clinical trial for lung cancer utilizes the combined interventions of erlotinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, and chloroquine (125). The anticancer mechanism of erlotinib is likely to be autophagy independent (36, 57). Inhibiting autophagy by chloroquine enhances anticancer effect of erlotinib by minimizing prosurvival effect of erlotinib-mediated autophagy in tumor cells (36, 57, 120, 125). Modulating autophagy activity may enhance the beneficial roles of autophagy or minimize the adverse effect of autophagy on each disease. Furthermore, adding autophagy modulators may improve the current pharmacological effect of drugs used for the treatment.

Although clinical trials for investigating the therapeutic effects of autophagy modulators are most desirable to observe the usefulness of drugs, cohort studies to examine the effect of autophagy modulator on patients' prognosis would be more accessible. For example, there are a number of patients with COPD who use autophagy modulators such as Ca2+ blockers, statin, or metformin for their medication; these drugs may influence patients' quality of life, lung function, and frequency of acute exacerbation. In addition, these studies may help to identify drugs which are suitable for the clinical trials.

CONCLUSION

Until now more than 20 different classes of drug used for treatment have been identified as autophagy modulators (9, 129) (Table 4). Moreover, the new-class autophagy modulators with improved specificity and effectiveness have been developed for human disease indications as potential therapeutics (Table 5). Given the important roles of autophagy in various lung diseases (Fig. 3 and Tables 2 and 3), utilizing autophagy modulators may improve the therapeutic effects of the current interventions in various lung diseases. However, there are also several important points to keep in mind. Although similar situations are observed in other medical interventions, effective and less-invasive methods to monitor autophagy activity for patients (e.g., biomarkers) are not currently available. Secondly, since autophagy is such a fundamental cellular process that affects various pathophysiological conditions, it is plausible that modulating autophagy causes other untoward effects that may be clinically deleterious. Finally, the autophagy modulators listed in Tables 4 and 5 may have off-target effects in addition to modulating autophagy. Nonetheless, recent clinical studies using autophagy modulators (3, 32, 67) and ongoing clinical trials (more than 15 active trials targeting autophagy) still suggest that autophagy modulators unravel new avenues in therapeutic interventions of various human diseases including lung diseases. Although further development of assays for autophagy activity and drugs with improved selectivity are needed, the day when we use autophagy-modifying drugs to treat lung disease may come sooner than later.

GRANTS

This study is supported by NIH T32HL007633-27 (K. Nakahira) and NIH PO1 HL105339 (A. M. K. Choi) and R01 HL05530 (A. M. K. Choi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.N. and A.M.K.C. conception and design of research; K.N. drafted manuscript; K.N. and A.M.K.C. edited and revised manuscript; K.N. and A.M.K.C. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jeffrey Adam Haspel for critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

The aim of this series is to provide practicing MDs and researchers an up-to-date physiological understanding of disease. Articles published in this series are intended to provide a thoughtful and lucid linkage of science to the patient. Go here for more information on this series and to browse the content (http://www.the-aps.org/mm/Publications/Journals/PIM).

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdulrahman BA, Khweek AA, Akhter A, Caution K, Kotrange S, Abdelaziz DH, Newland C, Rosales-Reyes R, Kopp B, McCoy K, Montione R, Schlesinger LS, Gavrilin MA, Wewers MD, Valvano MA, Amer AO. Autophagy stimulation by rapamycin suppresses lung inflammation and infection by Burkholderia cenocepacia in a model of cystic fibrosis. Autophagy 7: 1359–1370, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdulrahman BA, Khweek AA, Akhter A, Caution K, Tazi M, Hassan H, Zhang Y, Rowland PD, Malhotra S, Aeffner F, Davis IC, Valvano MA, Amer AO. Depletion of the ubiquitin-binding adaptor molecule SQSTM1/p62 from macrophages harboring cftr DeltaF508 mutation improves the delivery of Burkholderia cenocepacia to the autophagic machinery. J Biol Chem 288: 2049–2058, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, Casaburi R, Cooper JA, Jr, Criner GJ, Curtis JL, Dransfield MT, Han MK, Lazarus SC, Make B, Marchetti N, Martinez FJ, Madinger NE, McEvoy C, Niewoehner DE, Porsasz J, Price CS, Reilly J, Scanlon PD, Sciurba FC, Scharf SM, Washko GR, Woodruff PG, Anthonisen NR. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 365: 689–698, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amaravadi RK, Yu D, Lum JJ, Bui T, Christophorou MA, Evan GI, Thomas-Tikhonenko A, Thompson CB. Autophagy inhibition enhances therapy-induced apoptosis in a Myc-induced model of lymphoma. J Clin Invest 117: 326–336, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. An CH, Wang XM, Lam HC, Ifedigbo E, Washko GR, Ryter SW, Choi AM. TLR4 deficiency promotes autophagy during cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303: L748–L757, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aranguiz-Urroz P, Canales J, Copaja M, Troncoso R, Vicencio JM, Carrillo C, Lara H, Lavandero S, Diaz-Araya G. Beta(2)-adrenergic receptor regulates cardiac fibroblast autophagy and collagen degradation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1812: 23–31, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Araya J, Kojima J, Takasaka N, Ito S, Fujii S, Hara H, Yanagisawa H, Kobayashi K, Tsurushige C, Kawaishi M, Kamiya N, Hirano J, Odaka M, Morikawa T, Nishimura SL, Kawabata Y, Hano H, Nakayama K, Kuwano K. Insufficient autophagy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 304: L56–L69, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Armour SM, Baur JA, Hsieh SN, Land-Bracha A, Thomas SM, Sinclair DA. Inhibition of mammalian S6 kinase by resveratrol suppresses autophagy. Aging (Albany NY) 1: 515–528, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balgi AD, Fonseca BD, Donohue E, Tsang TC, Lajoie P, Proud CG, Nabi IR, Roberge M. Screen for chemical modulators of autophagy reveals novel therapeutic inhibitors of mTORC1 signaling. PLoS One 4: e7124, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bjorkoy G, Lamark T, Pankiv S, Overvatn A, Brech A, Johansen T. Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzymol 452: 181–197, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bodas M, Min T, Vij N. Critical role of CFTR-dependent lipid rafts in cigarette smoke-induced lung epithelial injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L811–L820, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Metivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, Pierron G, Codogno P, Kroemer G. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 25: 1025–1040, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cao Q, Yu C, Xue R, Hsueh W, Pan P, Chen Z, Wang S, McNutt M, Gu J. Autophagy induced by suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid in Hela S3 cells involves inhibition of protein kinase B and up-regulation of Beclin 1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 40: 272–283, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carchman EH, Rao J, Loughran PA, Rosengart MR, Zuckerbraun BS. Heme oxygenase-1-mediated autophagy protects against hepatocyte cell death and hepatic injury from infection/sepsis in mice. Hepatology 53: 2053–2062, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen ZH, Kim HP, Sciurba FC, Lee SJ, Feghali-Bostwick C, Stolz DB, Dhir R, Landreneau RJ, Schuchert MJ, Yousem SA, Nakahira K, Pilewski JM, Lee JS, Zhang Y, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Egr-1 regulates autophagy in cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 3: e3316, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen ZH, Lam HC, Jin Y, Kim HP, Cao J, Lee SJ, Ifedigbo E, Parameswaran H, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagy protein microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain-3B (LC3B) activates extrinsic apoptosis during cigarette smoke-induced emphysema. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18880–18885, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cheong H, Lu C, Lindsten T, Thompson CB. Therapeutic targets in cancer cell metabolism and autophagy. Nat Biotechnol 30: 671–678, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi AM, Ryter SW, Levine B. Autophagy in human health and disease. N Engl J Med 368: 1845–1846, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Conway KL, Kuballa P, Khor B, Zhang M, Shi HN, Virgin HW, Xavier RJ. ATG5 regulates plasma cell differentiation. Autophagy 9: 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Davis BK, Wen H, Ting JP. The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu Rev Immunol 29: 707–735, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. de Medina P, Silvente-Poirot S, Poirot M. Tamoxifen and AEBS ligands induced apoptosis and autophagy in breast cancer cells through the stimulation of sterol accumulation. Autophagy 5: 1066–1067, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Degtyarev M, De Maziere A, Orr C, Lin J, Lee BB, Tien JY, Prior WW, van Dijk S, Wu H, Gray DC, Davis DP, Stern HM, Murray LJ, Hoeflich KP, Klumperman J, Friedman LS, Lin K. Akt inhibition promotes autophagy and sensitizes PTEN-null tumors to lysosomotropic agents. J Cell Biol 183: 101–116, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Deretic V, Delgado M, Vergne I, Master S, De Haro S, Ponpuak M, Singh S. Autophagy in immunity against mycobacterium tuberculosis: a model system to dissect immunological roles of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 335: 169–188, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eisenberg T, Knauer H, Schauer A, Buttner S, Ruckenstuhl C, Carmona-Gutierrez D, Ring J, Schroeder S, Magnes C, Antonacci L, Fussi H, Deszcz L, Hartl R, Schraml E, Criollo A, Megalou E, Weiskopf D, Laun P, Heeren G, Breitenbach M, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Herker E, Fahrenkrog B, Frohlich KU, Sinner F, Tavernarakis N, Minois N, Kroemer G, Madeo F. Induction of autophagy by spermidine promotes longevity. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1305–1314, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ezaki J, Matsumoto N, Takeda-Ezaki M, Komatsu M, Takahashi K, Hiraoka Y, Taka H, Fujimura T, Takehana K, Yoshida M, Iwata J, Tanida I, Furuya N, Zheng DM, Tada N, Tanaka K, Kominami E, Ueno T. Liver autophagy contributes to the maintenance of blood glucose and amino acid levels. Autophagy 7: 727–736, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feldman ME, Apsel B, Uotila A, Loewith R, Knight ZA, Ruggero D, Shokat KM. Active-site inhibitors of mTOR target rapamycin-resistant outputs of mTORC1 and mTORC2. PLoS Biol 7: e38, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fleming A, Noda T, Yoshimori T, Rubinsztein DC. Chemical modulators of autophagy as biological probes and potential therapeutics. Nat Chem Biol 7: 9–17, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fujii S, Hara H, Araya J, Takasaka N, Kojima J, Ito S, Minagawa S, Yumino Y, Ishikawa T, Numata T, Kawaishi M, Hirano J, Odaka M, Morikawa T, Nishimura S, Nakayama K, Kuwano K. Insufficient autophagy promotes bronchial epithelial cell senescence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Oncoimmunology 1: 630–641, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ghavami S, Mutawe MM, Schaafsma D, Yeganeh B, Unruh H, Klonisch T, Halayko AJ. Geranylgeranyl transferase 1 modulates autophagy and apoptosis in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 302: L420–L428, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gorzalczany Y, Gilad Y, Amihai D, Hammel I, Sagi-Eisenberg R, Merimsky O. Combining an EGFR directed tyrosine kinase inhibitor with autophagy-inducing drugs: a beneficial strategy to combat non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 310: 207–215, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grander D, Kharaziha P, Laane E, Pokrovskaja K, Panaretakis T. Autophagy as the main means of cytotoxicity by glucocorticoids in hematological malignancies. Autophagy 5: 1198–1200, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Grossmann RE, Zughaier SM, Kumari M, Seydafkan S, Lyles RH, Liu S, Sueblinvong V, Schechter MS, Stecenko AA, Ziegler TR, Tangpricha V. Pilot study of vitamin D supplementation in adults with cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbation: a randomized, controlled trial. Dermatoendocrinology 4: 191–197, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J, Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM, Karantza V, Coller HA, Dipaola RS, Gelinas C, Rabinowitz JD, White E. Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 25: 460–470, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119: 753–766, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell 141: 656–667, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Han W, Pan H, Chen Y, Sun J, Wang Y, Li J, Ge W, Feng L, Lin X, Wang X, Jin H. EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors activate autophagy as a cytoprotective response in human lung cancer cells. PLoS One 6: e18691, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harris J, De Haro SA, Master SS, Keane J, Roberts EA, Delgado M, Deretic V. T helper 2 cytokines inhibit autophagic control of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunity 27: 505–517, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haspel J, Shaik RS, Ifedigbo E, Nakahira K, Dolinay T, Englert JA, Choi AM. Characterization of macroautophagic flux in vivo using a leupeptin-based assay. Autophagy 7: 629–642, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Henske EP, McCormack FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis — a wolf in sheep's clothing. J Clin Invest 122: 3807–3816, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hsieh CH, Pai PY, Hsueh HW, Yuan SS, Hsieh YC. Complete induction of autophagy is essential for cardioprotection in sepsis. Ann Surg 253: 1190–1200, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Iwai-Kanai E, Yuan H, Huang C, Sayen MR, Perry-Garza CN, Kim L, Gottlieb RA. A method to measure cardiac autophagic flux in vivo. Autophagy 4: 322–329, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jagannath C, Lindsey DR, Dhandayuthapani S, Xu Y, Hunter RL, Jr, Eissa NT. Autophagy enhances the efficacy of BCG vaccine by increasing peptide presentation in mouse dendritic cells. Nat Med 15: 267–276, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jeong JK, Moon MH, Bae BC, Lee YJ, Seol JW, Kang HS, Kim JS, Kang SJ, Park SY. Autophagy induced by resveratrol prevents human prion protein-mediated neurotoxicity. Neurosci Res 73: 99–105, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jiang H, White EJ, Rios-Vicil CI, Xu J, Gomez-Manzano C, Fueyo J. Human adenovirus type 5 induces cell lysis through autophagy and autophagy-triggered caspase activity. J Virol 85: 4720–4729, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kambas K, Mitroulis I, Apostolidou E, Girod A, Chrysanthopoulou A, Pneumatikos I, Skendros P, Kourtzelis I, Koffa M, Kotsianidis I, Ritis K. Autophagy mediates the delivery of thrombogenic tissue factor to neutrophil extracellular traps in human sepsis. PLoS One 7: e45427, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaminskyy VO, Piskunova T, Zborovskaya IB, Tchevkina EM, Zhivotovsky B. Suppression of basal autophagy reduces lung cancer cell proliferation and enhances caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis by stimulating ROS formation. Autophagy 8: 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim HP, Wang X, Chen ZH, Lee SJ, Huang MH, Wang Y, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Autophagic proteins regulate cigarette smoke-induced apoptosis: protective role of heme oxygenase-1. Autophagy 4: 887–895, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol 13: 132–141, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim JJ, Lee HM, Shin DM, Kim W, Yuk JM, Jin HS, Lee SH, Cha GH, Kim JM, Lee ZW, Shin SJ, Yoo H, Park YK, Park JB, Chung J, Yoshimori T, Jo EK. Host cell autophagy activated by antibiotics is required for their effective antimycobacterial drug action. Cell Host Microbe 11: 457–468, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Klein KA, Jackson WT. Human rhinovirus 2 induces the autophagic pathway and replicates more efficiently in autophagic cells. J Virol 85: 9651–9654, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Ahn HJ, Ait-Mohamed O, Ait-Si-Ali S, Akematsu T, Akira S, Al-Younes HM, Al-Zeer MA, Albert ML, Albin RL, Alegre-Abarrategui J, Aleo MF, Alirezaei M, Almasan A, Almonte-Becerril M, Amano A, Amaravadi R, Amarnath S, Amer AO, Andrieu-Abadie N, Anantharam V, Ann DK, Anoopkumar-Dukie S, Aoki H, Apostolova N, Arancia G, Aris JP, Asanuma K, Asare NY, Ashida H, Askanas V, Askew DS, Auberger P, Baba M, Backues SK, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Bai XY, Bailly Y, Baiocchi R, Baldini G, Balduini W, Ballabio A, Bamber BA, Bampton ET, Banhegyi G, Bartholomew CR, Bassham DC, Bast RC, Jr, Batoko H, Bay BH, Beau I, Bechet DM, Begley TJ, Behl C, Behrends C, Bekri S, Bellaire B, Bendall LJ, Benetti L, Berliocchi L, Bernardi H, Bernassola F, Besteiro S, Bhatia-Kissova I, Bi X, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Blum JS, Boise LH, Bonaldo P, Boone DL, Bornhauser BC, Bortoluci KR, Bossis I, Bost F, Bourquin JP, Boya P, Boyer-Guittaut M, Bozhkov PV, Brady NR, Brancolini C, Brech A, Brenman JE, Brennand A, Bresnick EH, Brest P, Bridges D, Bristol ML, Brookes PS, Brown EJ, Brumell JH, Brunetti-Pierri N, Brunk UT, Bulman DE, Bultman SJ, Bultynck G, Burbulla LF, Bursch W, Butchar JP, Buzgariu W, Bydlowski SP, Cadwell K, Cahova M, Cai D, Cai J, Cai Q, Calabretta B, Calvo-Garrido J, Camougrand N, Campanella M, Campos-Salinas J, Candi E, Cao L, Caplan AB, Carding SR, Cardoso SM, Carew JS, Carlin CR, Carmignac V, Carneiro LA, Carra S, Caruso RA, Casari G, Casas C, Castino R, Cebollero E, Cecconi F, Celli J, Chaachouay H, Chae HJ, Chai CY, Chan DC, Chan EY, Chang RC, Che CM, Chen CC, Chen GC, Chen GQ, Chen M, Chen Q, Chen SS, Chen W, Chen X, Chen YG, Chen Y, Chen YJ, Chen Z, Cheng A, Cheng CH, Cheng Y, Cheong H, Cheong JH, Cherry S, Chess-Williams R, Cheung ZH, Chevet E, Chiang HL, Chiarelli R, Chiba T, Chin LS, Chiou SH, Chisari FV, Cho CH, Cho DH, Choi AM, Choi D, Choi KS, Choi ME, Chouaib S, Choubey D, Choubey V, Chu CT, Chuang TH, Chueh SH, Chun T, Chwae YJ, Chye ML, Ciarcia R, Ciriolo MR, Clague MJ, Clark RS, Clarke PG, Clarke R, Codogno P, Coller HA, Colombo MI, Comincini S, Condello M, Condorelli F, Cookson MR, Coombs GH, Coppens I, Corbalan R, Cossart P, Costelli P, Costes S, Coto-Montes A, Couve E, Coxon FP, Cregg JM, Crespo JL, Cronje MJ, Cuervo AM, Cullen JJ, Czaja MJ, D'Amelio M, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Davids LM, Davies FE, De Felici M, de Groot JF, de Haan CA, De Martino L, De Milito A, De Tata V, Debnath J, Degterev A, Dehay B, Delbridge LM, Demarchi F, Deng YZ, Dengjel J, Dent P, Denton D, Deretic V, Desai SD, Devenish RJ, Di Gioacchino M, Di Paolo G, Di Pietro C, Diaz-Araya G, Diaz-Laviada I, Diaz-Meco MT, Diaz-Nido J, Dikic I, Dinesh-Kumar SP, Ding WX, Distelhorst CW, Diwan A, Djavaheri-Mergny M, Dokudovskaya S, Dong Z, Dorsey FC, Dosenko V, Dowling JJ, Doxsey S, Dreux M, Drew ME, Duan Q, Duchosal MA, Duff K, Dugail I, Durbeej M, Duszenko M, Edelstein CL, Edinger AL, Egea G, Eichinger L, Eissa NT, Ekmekcioglu S, El-Deiry WS, Elazar Z, Elgendy M, Ellerby LM, Eng KE, Engelbrecht AM, Engelender S, Erenpreisa J, Escalante R, Esclatine A, Eskelinen EL, Espert L, Espina V, Fan H, Fan J, Fan QW, Fan Z, Fang S, Fang Y, Fanto M, Fanzani A, Farkas T, Farre JC, Faure M, Fechheimer M, Feng CG, Feng J, Feng Q, Feng Y, Fesus L, Feuer R, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Fimia GM, Fingar DC, Finkbeiner S, Finkel T, Finley KD, Fiorito F, Fisher EA, Fisher PB, Flajolet M, Florez-McClure ML, Florio S, Fon EA, Fornai F, Fortunato F, Fotedar R, Fowler DH, Fox HS, Franco R, Frankel LB, Fransen M, Fuentes JM, Fueyo J, Fujii J, Fujisaki K, Fujita E, Fukuda M, Furukawa RH, Gaestel M, Gailly P, Gajewska M, Galliot B, Galy V, Ganesh S, Ganetzky B, Ganley IG, Gao FB, Gao GF, Gao J, Garcia L, Garcia-Manero G, Garcia-Marcos M, Garmyn M, Gartel AL, Gatti E, Gautel M, Gawriluk TR, Gegg ME, Geng J, Germain M, Gestwicki JE, Gewirtz DA, Ghavami S, Ghosh P, Giammarioli AM, Giatromanolaki AN, Gibson SB, Gilkerson RW, Ginger ML, Ginsberg HN, Golab J, Goligorsky MS, Golstein P, Gomez-Manzano C, Goncu E, Gongora C, Gonzalez CD, Gonzalez R, Gonzalez-Estevez C, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Gonzalez-Rey E, Gorbunov NV, Gorski S, Goruppi S, Gottlieb RA, Gozuacik D, Granato GE, Grant GD, Green KN, Gregorc A, Gros F, Grose C, Grunt TW, Gual P, Guan JL, Guan KL, Guichard SM, Gukovskaya AS, Gukovsky I, Gunst J, Gustafsson AB, Halayko AJ, Hale AN, Halonen SK, Hamasaki M, Han F, Han T, Hancock MK, Hansen M, Harada H, Harada M, Hardt SE, Harper JW, Harris AL, Harris J, Harris SD, Hashimoto M, Haspel JA, Hayashi S, Hazelhurst LA, He C, He YW, Hebert MJ, Heidenreich KA, Helfrich MH, Helgason GV, Henske EP, Herman B, Herman PK, Hetz C, Hilfiker S, Hill JA, Hocking LJ, Hofman P, Hofmann TG, Hohfeld J, Holyoake TL, Hong MH, Hood DA, Hotamisligil GS, Houwerzijl EJ, Hoyer-Hansen M, Hu B, Hu CA, Hu HM, Hua Y, Huang C, Huang J, Huang S, Huang WP, Huber TB, Huh WK, Hung TH, Hupp TR, Hur GM, Hurley JB, Hussain SN, Hussey PJ, Hwang JJ, Hwang S, Ichihara A, Ilkhanizadeh S, Inoki K, Into T, Iovane V, Iovanna JL, Ip NY, Isaka Y, Ishida H, Isidoro C, Isobe K, Iwasaki A, Izquierdo M, Izumi Y, Jaakkola PM, Jaattela M, Jackson GR, Jackson WT, Janji B, Jendrach M, Jeon JH, Jeung EB, Jiang H, Jiang JX, Jiang M, Jiang Q, Jiang X, Jimenez A, Jin M, Jin S, Joe CO, Johansen T, Johnson DE, Johnson GV, Jones NL, Joseph B, Joseph SK, Joubert AM, Juhasz G, Juillerat-Jeanneret L, Jung CH, Jung YK, Kaarniranta K, Kaasik A, Kabuta T, Kadowaki M, Kagedal K, Kamada Y, Kaminskyy VO, Kampinga HH, Kanamori H, Kang C, Kang KB, Kang KI, Kang R, Kang YA, Kanki T, Kanneganti TD, Kanno H, Kanthasamy AG, Kanthasamy A, Karantza V, Kaushal GP, Kaushik S, Kawazoe Y, Ke PY, Kehrl JH, Kelekar A, Kerkhoff C, Kessel DH, Khalil H, Kiel JA, Kiger AA, Kihara A, Kim DR, Kim DH, Kim EK, Kim HR, Kim JS, Kim JH, Kim JC, Kim JK, Kim PK, Kim SW, Kim YS, Kim Y, Kimchi A, Kimmelman AC, King JS, Kinsella TJ, Kirkin V, Kirshenbaum LA, Kitamoto K, Kitazato K, Klein L, Klimecki WT, Klucken J, Knecht E, Ko BC, Koch JC, Koga H, Koh JY, Koh YH, Koike M, Komatsu M, Kominami E, Kong HJ, Kong WJ, Korolchuk VI, Kotake Y, Koukourakis MI, Kouri Flores JB, Kovacs AL, Kraft C, Krainc D, Kramer H, Kretz-Remy C, Krichevsky AM, Kroemer G, Kruger R, Krut O, Ktistakis NT, Kuan CY, Kucharczyk R, Kumar A, Kumar R, Kumar S, Kundu M, Kung HJ, Kurz T, Kwon HJ, La Spada AR, Lafont F, Lamark T, Landry J, Lane JD, Lapaquette P, Laporte JF, Laszlo L, Lavandero S, Lavoie JN, Layfield R, Lazo PA, Le W, Le Cam L, Ledbetter DJ, Lee AJ, Lee BW, Lee GM, Lee J, Lee JH, Lee M, Lee MS, Lee SH, Leeuwenburgh C, Legembre P, Legouis R, Lehmann M, Lei HY, Lei QY, Leib DA, Leiro J, Lemasters JJ, Lemoine A, Lesniak MS, Lev D, Levenson VV, Levine B, Levy E, Li F, Li JL, Li L, Li S, Li W, Li XJ, Li YB, Li YP, Liang C, Liang Q, Liao YF, Liberski PP, Lieberman A, Lim HJ, Lim KL, Lim K, Lin CF, Lin FC, Lin J, Lin JD, Lin K, Lin WW, Lin WC, Lin YL, Linden R, Lingor P, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Lisanti MP, Liton PB, Liu B, Liu CF, Liu K, Liu L, Liu QA, Liu W, Liu YC, Liu Y, Lockshin RA, Lok CN, Lonial S, Loos B, Lopez-Berestein G, Lopez-Otin C, Lossi L, Lotze MT, Low P, Lu B, Lu Z, Luciano F, Lukacs NW, Lund AH, Lynch-Day MA, Ma Y, Macian F, MacKeigan JP, Macleod KF, Madeo F, Maiuri L, Maiuri MC, Malagoli D, Malicdan MC, Malorni W, Man N, Mandelkow EM, Manon S, Manov I, Mao K, Mao X, Mao Z, Marambaud P, Marazziti D, Marcel YL, Marchbank K, Marchetti P, Marciniak SJ, Marcondes M, Mardi M, Marfe G, Marino G, Markaki M, Marten MR, Martin SJ, Martinand-Mari C, Martinet W, Martinez-Vicente M, Masini M, Matarrese P, Matsuo S, Matteoni R, Mayer A, Mazure NM, McConkey DJ, McConnell MJ, McDermott C, McDonald C, McInerney GM, McKenna SL, McLaughlin B, McLean PJ, McMaster CR, McQuibban GA, Meijer AJ, Meisler MH, Melendez A, Melia TJ, Melino G, Mena MA, Menendez JA, Menna-Barreto RF, Menon MB, Menzies FM, Mercer CA, Merighi A, Merry DE, Meschini S, Meyer CG, Meyer TF, Miao CY, Miao JY, Michels PA, Michiels C, Mijaljica D, Milojkovic A, Minucci S, Miracco C, Miranti CK, Mitroulis I, Miyazawa K, Mizushima N, Mograbi B, Mohseni S, Molero X, Mollereau B, Mollinedo F, Momoi T, Monastyrska I, Monick MM, Monteiro MJ, Moore MN, Mora R, Moreau K, Moreira PI, Moriyasu Y, Moscat J, Mostowy S, Mottram JC, Motyl T, Moussa CE, Muller S, Munger K, Munz C, Murphy LO, Murphy ME, Musaro A, Mysorekar I, Nagata E, Nagata K, Nahimana A, Nair U, Nakagawa T, Nakahira K, Nakano H, Nakatogawa H, Nanjundan M, Naqvi NI, Narendra DP, Narita M, Navarro M, Nawrocki ST, Nazarko TY, Nemchenko A, Netea MG, Neufeld TP, Ney PA, Nezis IP, Nguyen HP, Nie D, Nishino I, Nislow C, Nixon RA, Noda T, Noegel AA, Nogalska A, Noguchi S, Notterpek L, Novak I, Nozaki T, Nukina N, Nurnberger T, Nyfeler B, Obara K, Oberley TD, Oddo S, Ogawa M, Ohashi T, Okamoto K, Oleinick NL, Oliver FJ, Olsen LJ, Olsson S, Opota O, Osborne TF, Ostrander GK, Otsu K, Ou JH, Ouimet M, Overholtzer M, Ozpolat B, Paganetti P, Pagnini U, Pallet N, Palmer GE, Palumbo C, Pan T, Panaretakis T, Pandey UB, Papackova Z, Papassideri I, Paris I, Park J, Park OK, Parys JB, Parzych KR, Patschan S, Patterson C, Pattingre S, Pawelek JM, Peng J, Perlmutter DH, Perrotta I, Perry G, Pervaiz S, Peter M, Peters GJ, Petersen M, Petrovski G, Phang JM, Piacentini M, Pierre P, Pierrefite-Carle V, Pierron G, Pinkas-Kramarski R, Piras A, Piri N, Platanias LC, Poggeler S, Poirot M, Poletti A, Pous C, Pozuelo-Rubio M, Praetorius-Ibba M, Prasad A, Prescott M, Priault M, Produit-Zengaffinen N, Progulske-Fox A, Proikas-Cezanne T, Przedborski S, Przyklenk K, Puertollano R, Puyal J, Qian SB, Qin L, Qin ZH, Quaggin SE, Raben N, Rabinowich H, Rabkin SW, Rahman I, Rami A, Ramm G, Randall G, Randow F, Rao VA, Rathmell JC, Ravikumar B, Ray SK, Reed BH, Reed JC, Reggiori F, Regnier-Vigouroux A, Reichert AS, Reiners JJ, Jr, Reiter RJ, Ren J, Revuelta JL, Rhodes CJ, Ritis K, Rizzo E, Robbins J, Roberge M, Roca H, Roccheri MC, Rocchi S, Rodemann HP, Rodriguez de Cordoba S, Rohrer B, Roninson IB, Rosen K, Rost-Roszkowska MM, Rouis M, Rouschop KM, Rovetta F, Rubin BP, Rubinsztein DC, Ruckdeschel K, Rucker EB, 3rd, Rudich A, Rudolf E, Ruiz-Opazo N, Russo R, Rusten TE, Ryan KM, Ryter SW, Sabatini DM, Sadoshima J, Saha T, Saitoh T, Sakagami H, Sakai Y, Salekdeh GH, Salomoni P, Salvaterra PM, Salvesen G, Salvioli R, Sanchez AM, Sanchez-Alcazar JA, Sanchez-Prieto R, Sandri M, Sankar U, Sansanwal P, Santambrogio L, Saran S, Sarkar S, Sarwal M, Sasakawa C, Sasnauskiene A, Sass M, Sato K, Sato M, Schapira AH, Scharl M, Schatzl HM, Scheper W, Schiaffino S, Schneider C, Schneider ME, Schneider-Stock R, Schoenlein PV, Schorderet DF, Schuller C, Schwartz GK, Scorrano L, Sealy L, Seglen PO, Segura-Aguilar J, Seiliez I, Seleverstov O, Sell C, Seo JB, Separovic D, Setaluri V, Setoguchi T, Settembre C, Shacka JJ, Shanmugam M, Shapiro IM, Shaulian E, Shaw RJ, Shelhamer JH, Shen HM, Shen WC, Sheng ZH, Shi Y, Shibuya K, Shidoji Y, Shieh JJ, Shih CM, Shimada Y, Shimizu S, Shintani T, Shirihai OS, Shore GC, Sibirny AA, Sidhu SB, Sikorska B, Silva-Zacarin EC, Simmons A, Simon AK, Simon HU, Simone C, Simonsen A, Sinclair DA, Singh R, Sinha D, Sinicrope FA, Sirko A, Siu PM, Sivridis E, Skop V, Skulachev VP, Slack RS, Smaili SS, Smith DR, Soengas MS, Soldati T, Song X, Sood AK, Soong TW, Sotgia F, Spector SA, Spies CD, Springer W, Srinivasula SM, Stefanis L, Steffan JS, Stendel R, Stenmark H, Stephanou A, Stern ST, Sternberg C, Stork B, Stralfors P, Subauste CS, Sui X, Sulzer D, Sun J, Sun SY, Sun ZJ, Sung JJ, Suzuki K, Suzuki T, Swanson MS, Swanton C, Sweeney ST, Sy LK, Szabadkai G, Tabas I, Taegtmeyer H, Tafani M, Takacs-Vellai K, Takano Y, Takegawa K, Takemura G, Takeshita F, Talbot NJ, Tan KS, Tanaka K, Tang D, Tanida I, Tannous BA, Tavernarakis N, Taylor GS, Taylor GA, Taylor JP, Terada LS, Terman A, Tettamanti G, Thevissen K, Thompson CB, Thorburn A, Thumm M, Tian F, Tian Y, Tocchini-Valentini G, Tolkovsky AM, Tomino Y, Tonges L, Tooze SA, Tournier C, Tower J, Towns R, Trajkovic V, Travassos LH, Tsai TF, Tschan MP, Tsubata T, Tsung A, Turk B, Turner LS, Tyagi SC, Uchiyama Y, Ueno T, Umekawa M, Umemiya-Shirafuji R, Unni VK, Vaccaro MI, Valente EM, Van den Berghe G, van der Klei IJ, van Doorn W, van Dyk LF, van Egmond M, van Grunsven LA, Vandenabeele P, Vandenberghe WP, Vanhorebeek I, Vaquero EC, Velasco G, Vellai T, Vicencio JM, Vierstra RD, Vila M, Vindis C, Viola G, Viscomi MT, Voitsekhovskaja OV, von Haefen C, Votruba M, Wada K, Wade-Martins R, Walker CL, Walsh CM, Walter J, Wan XB, Wang A, Wang C, Wang D, Wang F, Wang G, Wang H, Wang HG, Wang HD, Wang J, Wang K, Wang M, Wang RC, Wang X, Wang YJ, Wang Y, Wang Z, Wang ZC, Wansink DG, Ward DM, Watada H, Waters SL, Webster P, Wei L, Weihl CC, Weiss WA, Welford SM, Wen LP, Whitehouse CA, Whitton JL, Whitworth AJ, Wileman T, Wiley JW, Wilkinson S, Willbold D, Williams RL, Williamson PR, Wouters BG, Wu C, Wu DC, Wu WK, Wyttenbach A, Xavier RJ, Xi Z, Xia P, Xiao G, Xie Z, Xu DZ, Xu J, Xu L, Xu X, Yamamoto A, Yamashina S, Yamashita M, Yan X, Yanagida M, Yang DS, Yang E, Yang JM, Yang SY, Yang W, Yang WY, Yang Z, Yao MC, Yao TP, Yeganeh B, Yen WL, Yin JJ, Yin XM, Yoo OJ, Yoon G, Yoon SY, Yorimitsu T, Yoshikawa Y, Yoshimori T, Yoshimoto K, You HJ, Youle RJ, Younes A, Yu L, Yu SW, Yu WH, Yuan ZM, Yue Z, Yun CH, Yuzaki M, Zabirnyk O, Silva-Zacarin E, Zacks D, Zacksenhaus E, Zaffaroni N, Zakeri Z, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Zeitlin SO, Zhang H, Zhang HL, Zhang J, Zhang JP, Zhang L, Zhang MY, Zhang XD, Zhao M, Zhao YF, Zhao Y, Zhao ZJ, Zheng X, Zhivotovsky B, Zhong Q, Zhou CZ, Zhu C, Zhu WG, Zhu XF, Zhu X, Zhu Y, Zoladek T, Zong WX, Zorzano A, Zschocke J, Zuckerbraun B. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8: 445–544, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kominami E, Hashida S, Khairallah EA, Katunuma N. Sequestration of cytoplasmic enzymes in an autophagic vacuole-lysosomal system induced by injection of leupeptin. J Biol Chem 258: 6093–6100, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kon M, Kiffin R, Koga H, Chapochnick J, Macian F, Varticovski L, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy is required for tumor growth. Sci Transl Med 3: 109ra117, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kuballa P, Nolte WM, Castoreno AB, Xavier RJ. Autophagy and the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 611–646, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Laane E, Tamm KP, Buentke E, Ito K, Kharaziha P, Oscarsson J, Corcoran M, Bjorklund AC, Hultenby K, Lundin J, Heyman M, Soderhall S, Mazur J, Porwit A, Pandolfi PP, Zhivotovsky B, Panaretakis T, Grander D. Cell death induced by dexamethasone in lymphoid leukemia is mediated through initiation of autophagy. Cell Death Differ 16: 1018–1029, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lamark T, Johansen T. Aggrephagy: selective disposal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy. Int J Cell Biol 2012: 736905, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lee JG, Wu R. Combination erlotinib-cisplatin and Atg3-mediated autophagy in erlotinib resistant lung cancer. PLoS One 7: e48532, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lee SJ, Ryter SW, Xu JF, Nakahira K, Kim HP, Choi AM, Kim YS. Carbon monoxide activates autophagy via mitochondrial reactive oxygen species formation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 45: 867–873, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lee SJ, Smith A, Guo L, Alastalo TP, Li M, Sawada H, Liu X, Chen ZH, Ifedigbo E, Jin Y, Feghali-Bostwick C, Ryter SW, Kim HP, Rabinovitch M, Choi AM. Autophagic protein LC3B confers resistance against hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 649–658, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469: 323–335, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li C, Liu H, Sun Y, Wang H, Guo F, Rao S, Deng J, Zhang Y, Miao Y, Guo C, Meng J, Chen X, Li L, Li D, Xu H, Li B, Jiang C. PAMAM nanoparticles promote acute lung injury by inducing autophagic cell death through the Akt-TSC2-mTOR signaling pathway. J Mol Cell Biol 1: 37–45, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liu HL, Zhang YL, Yang N, Zhang YX, Liu XQ, Li CG, Zhao Y, Wang YG, Zhang GG, Yang P, Guo F, Sun Y, Jiang CY. A functionalized single-walled carbon nanotube-induced autophagic cell death in human lung cells through Akt-TSC2-mTOR signaling. Cell Death Dis 2: e159, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Liu J, Xia H, Kim M, Xu L, Li Y, Zhang L, Cai Y, Norberg HV, Zhang T, Furuya T, Jin M, Zhu Z, Wang H, Yu J, Hao Y, Choi A, Ke H, Ma D, Yuan J. Beclin1 controls the levels of p53 by regulating the deubiquitination activity of USP10 and USP13. Cell 147: 223–234, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Lo S, Yuan SS, Hsu C, Cheng YJ, Chang YF, Hsueh HW, Lee PH, Hsieh YC. Lc3 Over-expression improves survival and attenuates lung injury through increasing autophagosomal clearance in septic mice. Ann Surg 257: 352–363, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Luciani A, Villella VR, Esposito S, Brunetti-Pierri N, Medina D, Settembre C, Gavina M, Pulze L, Giardino I, Pettoello-Mantovani M, D'Apolito M, Guido S, Masliah E, Spencer B, Quaratino S, Raia V, Ballabio A, Maiuri L. Defective CFTR induces aggresome formation and lung inflammation in cystic fibrosis through ROS-mediated autophagy inhibition. Nat Cell Biol 12: 863–875, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]