Abstract

Electrical dyssynchrony leads to prestretch in late-activated regions and alters the sequence of mechanical contraction, although prestretch and its mechanisms are not well defined in the failing heart. We hypothesized that in heart failure, fiber prestretch magnitude increases with the amount of early-activated tissue and results in increased end-systolic strains, possibly due to length-dependent muscle properties. In five failing dog hearts with scars, three-dimensional strains were measured at the anterolateral left ventricle (LV). Prestretch magnitude was varied via ventricular pacing at increasing distances from the measurement site and was found to increase with activation time at various wall depths. At the subepicardium, prestretch magnitude positively correlated with the amount of early-activated tissue. At the subendocardium, local end-systolic strains (fiber shortening, radial wall thickening) increased proportionally to prestretch magnitude, resulting in greater mean strain values in late-activated compared with early-activated tissue. Increased fiber strains at end systole were accompanied by increases in preejection fiber strain, shortening duration, and the onset of fiber relengthening, which were all positively correlated with local activation time. In a dog-specific computational failing heart model, removal of length and velocity dependence on active fiber stress generation, both separately and together, alter the correlations between local electrical activation time and timing of fiber strains but do not primarily account for these relationships.

Keywords: epicardial pacing, fiber strain, heart failure, prestretch, wall thickening

in the normal heart, ectopic ventricular pacing results in dyssynchronous electrical activation, giving rise to an altered sequence of contraction, depressed pump function, and chronic ventricular remodeling (27, 40). Badke and coworkers (4) first described the effects of ectopic activation on regional mechanics in normal hearts. During ventricular epicardial pacing, early shortening (prior to aortic valve opening) occurs near the LV pacing site, whereas late-activated regions lengthen or “prestretch” during early systole. The magnitude of prestretch increases with local activation time (7), resulting in an increase in peak magnitude of fiber shortening in the late-activated regions (9, 18), with implications for subsequent long-term remodeling of the tissue. Proposed mechanisms for increased systolic fiber prestretch in late-activated regions involve both mechanical deformation imposed by adjacent early contracting regions and increased intracavity pressure at the time of local electrical activation (7). A recent computational study found that fiber prestretch resulted from a spatial variation in local fiber stiffness and the governing requirement of force equilibrium in the presence of a dyssynchronous activation sequence (19). Enhanced shortening function in late activated tissue may be a result of length-dependent activation due to longer fiber lengths (18, 28, 30).

In heart failure, the complex alterations in tissue mechanics and regional muscle fiber function may alter the effects and implications of dyssynchronous electrical activation. Investigating mechanical prestretch in the failing heart may provide mechanistic insight into the role of length-dependent fiber function in the early- and late-activated regions. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to quantify fiber prestretch in a canine model of dyssynchronous heart failure and investigate possible mechanisms for increased local strains in late-activated tissue. Specifically, we hypothesize that in the failing heart 1) the peak magnitude of fiber prestretch is proportional to the amount of early-activated tissue; 2) end-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening increase in proportion to prestretch magnitude as seen in the normal heart; and 3) length-dependent fiber stress generation is a mechanism of the strain variation in early- and late-activated tissue. To address these, we implemented a canine model of dyssynchronous heart failure with implanted markers and x-ray imaging to measure regional transmural strains in early- and late-activated tissue and used a dog-specific finite-element model of the failing heart to further elucidate potential mechanisms for changes in local fiber function due to altered electrical activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal studies were performed according to the National Institutes of Health “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.” Experimental protocols were submitted to and approved by the Animal Subjects Committee of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), which is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Tachycardia-induced heart failure protocol.

We implemented a previously established canine model of tachycardia-induced heart failure and myocardial infarction (6, 15) in five adult mongrel dogs (19–26 kg). Under sterile conditions and a surgical plane of anesthesia, a minimally invasive left thoracotomy was performed. Arterial pressure was monitored throughout the surgery by placing a small catheter, attached to a fluid-filled pressure transducer, into a side branch of the right femoral artery. Bipolar epicardial leads (CAPSURE EPI, model no. 4968, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) were sewn onto the right ventricular apical epicardium and routed to a programmable pacemaker capable of rates above 180 beats/min (INSYNC III, model no. 8042, Medtronic). Radiopaque gold markers (1–2 mm) were implanted to study three-dimensional transmural mechanics in the anterolateral LV wall, as described previously (2, 14, 39). An implantable pressure gauge (model no. TA11PA-C40, Data Sciences International, St. Paul, MN) was inserted into the left atrial appendage for noninvasive monitoring of left atrial pressure after surgery. The left circumflex coronary artery was dissected, and a marginal branch of the circumflex was permanently ligated with the distal ends embolized with multiple injections (4–8 ml) of microspheres (100- to 300-μm diameter, Biospheres Medical, Rockland, MA). Posterolateral scars were allowed to heal for 5 wk, and high rate ventricular pacing (220–250 beats/min) was performed for an additional 5 wk, resulting in a 10-wk period post initial surgery. The primary purpose of using a chronic infarct model, combined with the tachycardia-induced heart failure protocol, was to accelerate the progression of heart failure and reduce the potential for reverse remodeling once the rapid pacing period had ended and animals returned to normal sinus rhythm. The success of the combined infarct and rapid pacing model has been previously demonstrated by others (15). Prior to the terminal study, high-rate pacing was discontinued for 24 h. Cessation of high-rate pacing was done primarily to ensure lower intrinsic sinus rates at the terminal study to allow for AV sequential pacing within normal rates. Left atrial pressure was recorded at the onset, bidaily throughout the duration, and 24 h after the cessation of high-rate pacing. Only animals with mean left atrial pressure values of 3–4 times the value recorded at the onset of high-rate pacing, and displaying clinical signs of heart failure, were entered into the terminal experimental study.

Surgical preparation at the terminal study.

Acute ventricular pacing studies were performed ∼10 wk after animals had been subjected to posterolateral infarction and heart failure protocols, as described above. Animals were induced at the terminal study with intravenous propofol (4–6 mg/kg), intubated, and mechanically ventilated with a mixture of isoflurane (2%) and medical-grade oxygen (2 l/min) to achieve a surgical plane of anesthesia. To maintain a sustainable hemodynamic state (e.g., systolic pressure greater than 75 mmHg during intrinsic rhythm), inotropic support and supplemental analgesia were provided intermittently during the study with dopamine (3–10 μg·kg−1·min−1 iv) and buprenorphine (0.02–0.05 mg/kg sc), respectively. After a medial sternotomy and left thoracotomy at the fifth intercostal junction, the heart was positioned in a pericardial cradle. Bipolar pacing wires were sewn to the left atrial appendage for atrial pacing. Custom-made bipolar plunge electrodes (7) were positioned at the right ventricular apex and at five LV epicardial sites (Fig. 1). The bipolar electrodes were used for measuring local electrical activation time when not connected to the external stimulator. Additionally, at each LV epicardial pacing site, a bipolar recording electrode was positioned on the LV endocardium. Ventricular activation was achieved by atrioventricular (AV) sequential pacing of the left atrial appendage and one of the epicardial bipolar electrodes with a fixed AV delay of 40 ms.

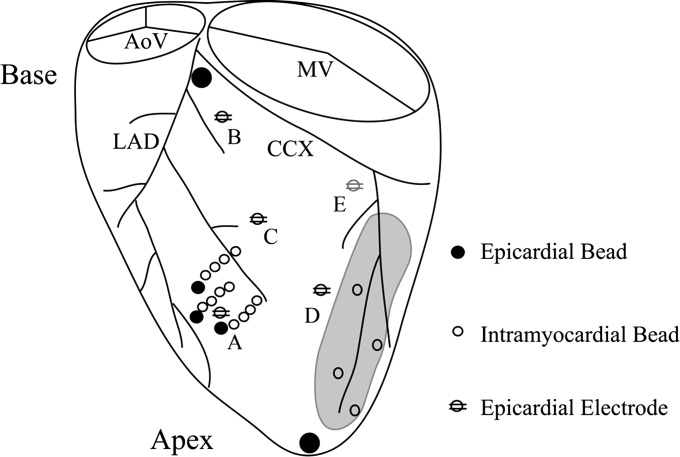

Fig. 1.

Location of implanted myocardial markers and epicardial pacing sites in the canine left ventricle. Intramyocardial gold beads were implanted at the anterolateral left ventricle, between diagonal branches of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. Surface epicardial beads were sewn at the entrance of each transmural column and at the apex and base of the heart, defined by the bifurcation of the LAD and circumflex (CCX) arteries. Bipolar pacing electrodes were positioned at the right ventricular apex (not shown) and at five left ventricular epicardial sites: anterior apical (A), anterior basal (B), anterior midventricle (C), lateral (D), and posterior basal near the coronary sinus (E). AoV, aortic valve; MV, mitral valve.

Varying the local electrical activation time at the anterolateral LV.

To alter the local electrical activation time at the anterolateral wall, ventricular pacing at multiple epicardial pacing sites, with increasing distance from the strain measurement site, was performed. LV epicardial pacing near the measurement site (i.e., anterior apex, Fig. 1) was used to induce early electrical activation, whereas remote sites were used to produce longer electrical activation times at the measurement site. Thus ventricular pacing at multiple anatomical sites was used to vary the electrical activation time and magnitude of prestretch at the anterolateral LV.

Electrical and hemodynamic measurements.

LV cavity pressure and rate of change were monitored with a high-fidelity micromanometer (model P6; Konigsburg Instruments, Pasadena, CA) placed in the LV lumen via puncture of the LV apex and closure with a purse-string suture. The micromanometer was matched to a statically calibrated fluid-filled pressure gauge, which was zeroed at a level approximate to the center of the heart. Aortic flow was obtained with an ultrasonic flow probe (model no. T208; Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY). LV volumes were measured with a conductance catheter (3) (Webster Laboratories, Baldwin Park, CA) positioned in the LV cavity via the left carotid artery. The conductance catheter was calibrated in vivo at the end of the study with a bolus (2–5 ml) injection of hypertonic saline solution (6 M NaCl). Arterial and aortic pressures were monitored with fluid-filled gauges positioned in the right femoral artery and left subclavian artery, respectively. Lead II electrocardiogram was recorded, along with local bipolar electrograms from nonpaced LV electrodes. A custom epicardial sock, consisting of 128 unipolar electrodes, was positioned on the heart to measure the electrical sequence of activation during ventricular pacing. Additionally, as described above, bipolar electrodes positioned at the subepicardium and subendocardium were used to measure local activation times at the subepicardium, midwall (interpolated), and subendocardium at the strain measurement site.

Pacing protocol and signal analysis.

Atrial, right ventricular apex, and LV epicardial pacing were performed via stimulation of bipolar electrodes with square-wave pulse generators (model no. SD9; Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA). LV epicardial pacing sites were anterior base, anterior apex, anterolateral midventricle, lateral midventricle, and posterior base near the coronary sinus (Fig. 1). All electrodes were positioned at least 1 cm from the posterolateral infarct. Pacing parameters were held constant throughout the study at a frequency > 120% of intrinsic rate, voltage > 110% threshold value, and AV delay of 40 milliseconds. The 128-electrode amplifier was set to a gain of 20–50×, and signal frequencies outside the desired range (2–200 kHz) were filtered from the recorded signals. Off-line signal analysis was performed in custom software in MATLAB 7.10 (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The time of the maximum derivative of electrode voltage was used to define the time of local activation at each electrode.

For all pacing runs, hemodynamic variables were collected after steady-state conditions were reached (∼2 min following the onset of pacing). Maximum (LVPmax), end-diastolic (LVEDP), and end-systolic (LVESP) LV pressures were determined with the calibrated micromanometer signal. Stroke volume (SV) was found by numerical integration of the aortic flow signal between the interval of aortic valve opening and closure, as determined by the zero crossing of the flow signal. Forward ejection fraction (EF) was determined by dividing SV by the end-diastolic volume determined by the conductance catheter. Numerical computation was performed off-line using custom software in MATLAB.

At the end of the study, animals were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg iv). Hearts were isolated in situ, perfused with cardioplegia, and perfusion-fixed at zero LV pressure with buffered glutaraldehyde (5%).

Additional pacing protocols, not described and out of scope, were performed in all five of the animals presented in the current study. Data collected from these out of scope protocols have been presented previously (14). Changes in body weight, unloaded LV volume, EDP, and other hemodynamic variables in the five animals of the present study have been previously summarized elsewhere (14).

Obtaining 3D geometry and fiber architecture with MRI and DTMRI.

For one dog (dog 6), geometry and fiber architecture were measured with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DTMRI) in the excised, postmortem heart fixed with an LV pressure of 0 mmHg. These high-resolution data were used to create a dog-specific computational model. The MRI and DTMRI protocols were performed on a General Electric (GE) Discovery MR750 3.0T whole body imaging system (GE Healthcare Waukesha, WI) at the Center for Functional MRI at UCSD. Anatomical scans were performed with a 3D gradient echo pulse sequence; parameters were optimized for signal to noise: echo time (TE) = minimum, repetition time (TR) = 8.7 ms, flip angle = 15°, and averages = 4. A field of view of 10.0 cm and data matrix of 256 × 256 were prescribed for an in-plane resolution of 391 μm; slice thickness was 1.0 mm, resulting in 82 contiguous slices. DTMRI was performed with a custom 3D fast spin echo pulse sequence (10). DTMRI parameters were TE = minimum, TR = 500 ms, FOV = 10 cm and in-plane resolution of 128 × 128 slices or 781 μm, slice thickness of 1.0 mm, and 12 diffusion encoded directions.

Three-dimensional coordinate reconstruction of implanted myocardial markers.

Intramyocardial markers were imaged with a biplane cineradiography system and digital images from the two X-ray views were acquired at high temporal resolution (125 frames/s). After allowing time to reach steady state during each pacing run, radiographic images were collected for multiple beats with respiration suspended at end expiration. Two-dimensional marker coordinates from each view were then corrected for spherical distortion (1) and reconstructed into three-dimensional coordinates (25) in a cardiac coordinate system defined by five reference markers (26).

Three-dimensional transmural fiber mechanics throughout the cardiac cycle.

Nonhomogenous, three-dimensional Lagrangian strain distributions across the anterolateral LV were computed throughout one complete cardiac cycle for atrial and ventricular activations. A time series of radiographic images, representing one complete cardiac cycle, were arranged such that the first and last frames corresponded to subsequent occurrences of the local ventricular pacing stimulus, visible as artifacts on the ECG recording. Unless otherwise specified, the reference configuration for strain calculation was the first frame in the time series, corresponding to the 3D positions of implanted markers at the time of the local ventricular pacing stimulus. Time courses of six independent strain components defined in a cardiac material coordinate system (circumferential, longitudinal, and radial) were determined at three transmural depths: subepicardium (25%), midwall (50%), and subendocardium (75%). At each wall depth, mean fiber angle measurements were used to rotate cardiac strain components (circumferential, longitudinal, radial) into fiber material coordinates (fiber, cross-fiber, radial) as described previously (2). The primary assumption was that fibers lie predominantly in planes parallel to the epicardial tangent plane. With this assumption, a reference coordinate system with directions aligned to the fiber, cross-fiber, and radial axes is defined by a rotation of the cardiac coordinates by the mean fiber angle.

Defining fiber prestretch and timing parameters of fiber strain.

The magnitude of fiber prestretch was defined as the strain magnitude at the first onset of fiber shortening, which corresponded to either a fiber strain value of zero or greater. Briefly, fiber strain rate was computed from the time course of fiber strain. The first zero crossing of fiber strain rate was defined as the onset of fiber shortening. The onset of fiber relengthening was then defined as the first zero crossing of fiber strain rate during the interval between the onset of fiber shortening and global ventricular stimulus of the next beat. In cases where multiple phases of shortening and lengthening occurred (i.e., multiple local minima/maxima), the earliest onsets of shortening and relengthening were used. Fiber shortening duration was defined as time difference between the first onset of relengthening and first onset of shortening. Results depicting the onset of fiber relengthening are presented minus the local activation time to correct for intrinsic dependence on the timing difference between the ventricular stimulus pacing artifact (0 ms) and local subendocardial electrical activation time.

Estimation of the amount of early-activated tissue at the sub-epicardium.

We used electrical activation times measured with a 128-electrode epicardial sock to create 2D epicardial isochronal maps using a polar grid projection (i.e., Bulls-eye plot) which conserved both the longitudinal and circumferential distribution of the electrodes. Briefly, dog-specific polar grids were defined from 3D polar coordinates of the 128 epicardial electrodes, obtained with a 3D digitization arm (Faro Instruments) in the postmortem heart. Local electrical activation time (ATlocal) at the strain measurement site was used to threshold regions of early electrical activation; specifically, regions with an activation time less than or equal to ATlocal minus 10 ms were defined as earlier-activated tissue. Percent total area of the threshold region was used as a measure of the amount of earlier activated tissue. Thus earlier activated tissue was defined relative to the time of electrical activation at the strain measurement site.

Histological measurement of mean fiber and sheet angle orientation.

To minimize the distortion effects of dehydration and shrinkage associated with paraffin embedding, histological measurements were obtained in fresh perfusion-fixed tissue. A transmural block from the anterolateral left ventricle, near the location of the implanted markers, was carefully excised with block edges cut parallel to the locally defined longitudinal, circumferential, and radial directions. Mean fiber and sheet angle measurements were then made at 1-mm transmural increments from epicardium to endocardium (1). In the case of bimodal distributions of sheet angle, mean sheet angle was determined by the circular average of the dominant sheet population, defined by the number of measurements. Mean fiber and sheet angle distributions in each animal were then corrected for geometric changes and variations in chamber pressure during fixation using the method of Takayama et al. (34). The main assumptions of the methods employed for fiber angle measurement were 1) myofibers lie in a plane parallel to the local epicardial tangent plane, and 2) transmural fiber orientation can be described by a mean fiber angle at each incremental depth.

Numerical simulations in a dog-specific computational model of the failing heart.

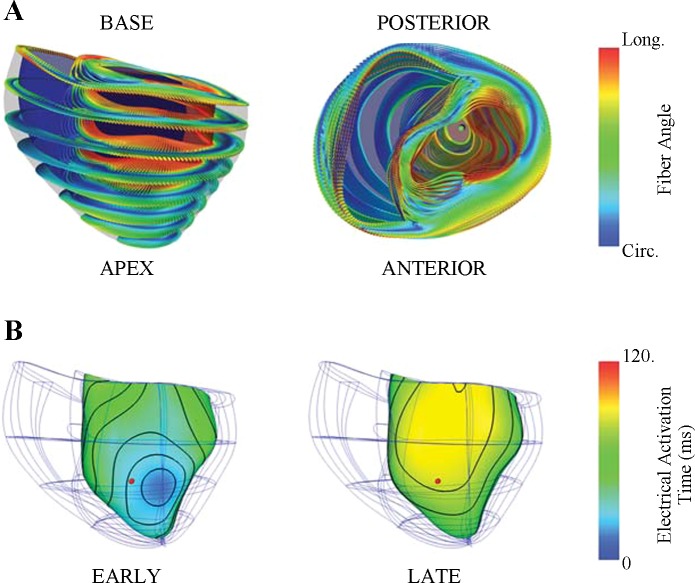

Left ventricular mechanics were simulated in a dog-specific model of biventricular electromechanics, created using one dog from the experiments. Further details of the modeling methods can be found in the Supplemental Material available with the online version of this article). Anatomical models of the right and left ventricular geometry and fiber architecture were fitted to MRI and DT-MRI data (21). The fiber architecture fit using DT-MRI data was initialized with generic transmural fiber angles of −60° to +60° (epicardial to endocardial), with 0° transverse and sheet angles throughout the myocardial volume. The fit was penalized against regions with poor quality DT-MRI measurements (e.g., the RV free wall) to preserve the initialized fiber-sheet orientations in those regions. The ventricles were described by a total of 128 tricubic Hermite finite elements and 5,016 degrees of freedom. Each element consisted of a 3 × 3 × 3 arrangement of integration points. The finite element model is shown in Fig. 2A. The finite element model was coupled to a three-element Windkessel model (17), and the Arts model of sarcomere mechanics (24) governed the generation of active fiber stress. Parameters of the baseline sarcomere mechanics model were obtained by matching LV cavity pressures and strain time courses between model and experiment. Passive material properties were estimated by matching end-diastolic LV pressure between model and experiment. Electrical activation times (Fig. 2B) during ventricular pacing were computed by an electrophysiology model (35) using a more refined discretization of the ventricles with 25,600 tricubic Hermit finite elements, 245,520 degrees of freedom, and a 4 × 4 × 4 arrangement of integration points. Conduction velocities were determined by matching subendocardium activation time at the location of strain measurement and QRS duration between experiment and model. Electrical activation times were then used to initiate active stress development.

Fig. 2.

Dog-specific computational model of the failing canine heart. A: 128 tricubic Hermite finite elements were used to describe realistic geometry obtained from one experimental animal (dog 6). Anterior (left) and basal (right) views of the fiber architecture fitted to DT-MRI measurements were registered to the mesh using a log-Euclidean framework to interpolate the tensors (23). The 3-dimensional local fiber-sheet structure is visualized by the shape, orientation, and color glyphs; the primary and minor axes of the glyphs represent the fiber and sheet-normal axes, respectively. The glyph color redundantly encodes circumferential to longitudinal (blue to red) fiber orientation to illustrate the smooth fiber variation. B: ventricular pacing at 2 separate locations resulted in opposite sequences of electrical activation. Local activation times are rendered in color at the subendocardial surface of the finite-element model. During left ventricular anterior apical pacing (EARLY, left), subendocardial activation was relatively uniform across the anterolateral apical wall and occurred earlier compared with the septal and right ventricular free walls. Pacing on the posterior basal left ventricle (LATE, right) resulted in delayed activation at the anterolateral left ventricle. A comparable anterolateral location (red dot) to the experimental protocol was used to compare differences between early at late activation. Local electrical activation time at the mechanical site was 28 and 81 ms for EARLY and LATE, respectively. Circ, circumferential; Long, longitudinal.

The baseline active stress model (BASE) consisted of a Hill relationship, which modeled the sarcomere as a passive element in parallel with contractile and series elastic elements. Detailed mathematical descriptions of the active stress model and its dependence on sarcomere length and shortening velocity are described elsewhere (24).

The BASE model was then modified in the following ways: 1) active stress dependency on sarcomere shortening velocity was removed, thus resulting in a velocity independent (VI) model; 2) active stress dependency on sarcomere length was removed (LI); and 3) active stress dependency on both sarcomere length and shortening velocity was removed, thus resulting in a length and velocity independent model (LVI).

A total of eight simulations were performed using two activation sequences (i.e., 2 pacing locations were used for each of the 4 active stress models). The ventricular pacing locations were the posterior basal near coronary sinus (PCS) and the anterior apical site (AAPEX), as in the experiments, which resulted in early activation and late activation at the anterolateral LV, respectively. The multiscale model was solved with the Continuity 6.4 package (http://www.continuity.ucsd.edu).

Model fiber strains at the subendocardial anterior LV equator were selected for comparison of experimental findings at a similar site. Local fiber strain, the time to the onset of fiber relengthening, and fiber shortening duration were computed to determine the effects of length and velocity dependence on active stress generation in regulating local fiber function during dyssynchrony.

Statistical analysis.

All measurements are reported as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed in SigmaPlot 11 (SyStat Software, San Jose, CA). A one-factor repeated-measures ANOVA was used to determine the effect of pacing site on functional parameters (e.g., QRSd, dP/dtmax, end-systolic Eff). Post hoc comparisons between pacing sites were performed with a Tukey's test. For comparison of mean values between two groups a two-tailed Student's t-test was used. Linear regression analysis was performed to investigate the effects of activation time and peak fiber prestretch on strain magnitudes and timing parameters for experimental and numerical results. In all cases, statistical significance was accepted for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Electrical dyssynchrony impairs global hemodynamic function.

The effects of pacing site on electrical and hemodynamic parameters are summarized in Table 1. Compared with atrial activation, QRS duration was increased (P < 0.05) and SV reduced (P < 0.05) during ventricular pacing at all sites. LV dP/dtmax was lowered (P < 0.05) in a majority of the ventricular pacing sites, compared with atrial activation. Changes in body weight, unloaded left ventricular volume, and end-diastolic filling pressure resulting from 5 wk of tachycardia-induced heart failure and posterolateral scarring have been previously reported in all of these animals (14). Peak systolic pressure and LV dP/dtmin were unchanged for nearly all LV epicardial pacing sites, but significantly reduced (P < 0.05) for the RVA pacing site, compared with atrial activation. After combining data from all ventricular pacing sites, QRS duration increased by 133.6 ± 5.8% (P < 0.001) compared with atrial activation, and LVPmax, dP/dtmax, dP/dtmin, and SV were reduced, compared with atrial activation, by 12.0 ± 1.7% (P < 0.01), 27.7 ± 7.0% (P < 0.05), 22.3 ± 3.6% (P < 0.01), and 20.0 ± 5.1% (P < 0.05), respectively.

Table 1.

Electrical and hemodynamic parameters at steady-state during ventricular pacing

| Pacing Site | RR, ms | QRSd, ms | LVEDP, mmHg | LVESP, mmHg | LVPmax, mmHg | dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | SV, ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATRIAL | 485.7 ± 13.1 | 53.1 ± 4.8 | 14.6 ± 0.9 | 64.3 ± 7.9 | 93.9 ± 6.3 | 1,768 ± 344 | −1,593 ± 161 | 9.0 ± 1.5 |

| RVA | 485.1 ± 13.0 | 124.3 ± 8.7* | 13.4 ± 0.5 | 51.4 ± 6.9 | 78.6 ± 7.3* | 1,296 ± 329* | −1,100 ± 210† | 6.6 ± 1.0* |

| PCS | 485.1 ± 14.5 | 123.4 ± 14.0* | 13.1 ± 0.5 | 52.7 ± 6.7 | 81.6 ± 7.7 | 1,382 ± 314† | −1,177 ± 159 | 6.2 ± 0.7* |

| LAT | 484.4 ± 15.1 | 132.1 ± 17.9* | 12.6 ± 1.1 | 55.5 ± 5.5 | 84.7 ± 6.4 | 1,438 ± 307 | −1,318 ± 194 | 6.5 ± 0.7* |

| ABASE | 484.9 ± 15.1 | 121.9 ± 13.0* | 13.1 ± 0.6 | 48.9 ± 2.3 | 78 ± 3.2 | 1,264 ± 232* | −1,147 ± 74 | 5.5 ± 0.3* |

| AMID | 484.7 ± 13.4 | 131.6 ± 13.5* | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 53.3 ± 4.7 | 82.6 ± 4.9 | 1,317 ± 181* | −1,294 ± 133 | 6.2 ± 0.6* |

| AAPEX | 485.1 ± 13.2 | 109.8 ± 11.1* | 13.6 ± 0.7 | 52.9 ± 5.5 | 81.9 ± 5.7 | 1,300 ± 157* | −1,300 ± 144 | 6.4 ± 0.7* |

Values are mean ± SE (n = 5). RR, RR interval; QRSd, QRS duration; LVEDP, end-diastolic left ventricular pressure; LVESP, end- systolic left ventricular pressure; LVPmax, maximum left ventricular pressure; dP/dtmax, maximum rate of pressure change; dP/dtmin, minimum rate of pressure change; SV, stroke volume; RVA, right ventricular apex; PCS, posterior near coronary sinus; LAT, lateral; ABASE, anterior base; AMID, anterior mid-ventricle; AAPEX, anterior apex (i.e., site of intramyocardial markers).

Ventricular pacing vs. Atrial (P < 0.05, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test).

Ventricular pacing vs. Atrial (P < 0.10, one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test). No statistically significant differences were present among ventricular pacing sites.

Transmural marker positions, LV wall geometry, and local fiber-sheet orientations.

The centroid of the epicardial surface markers was located at a distance of 66.1 ± 5.4% of the apex-base length referenced from the base bead. The deepest bead of the transmural array spanned 77.4 ± 5.8% of the local wall thickness. Ex vivo wall thickness near the markers was 11.7 ± 0.4 mm in the perfusion-fixed geometric configuration at a LV intracavity pressure of 0 mmHg. Values of mean fiber and sheet angle orientation at the subepicardium, midwall, and subendocardium are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Average fiber and sheet angle values at three transmural depths in the anterolateral LV

| Wall Depth | Fiber Angle0 | Sheet Angle0 |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Epi | −7.45 ± 3.13 | −37.8 ± 1.47 |

| Mid | 34.8 ± 3.48 | −50.5 ± 2.20 |

| Sub-Endo | 73.5 ± 5.50 | −59.1 ± 5.94 |

Values are mean ± SE. Sub-Epi, subepicardium (25% wall depth); Mid, midwall (50% wall depth); Sub-Endo, subendocardium (75% wall depth).

Fiber prestretch increases proportionally to the amount of early activated tissue.

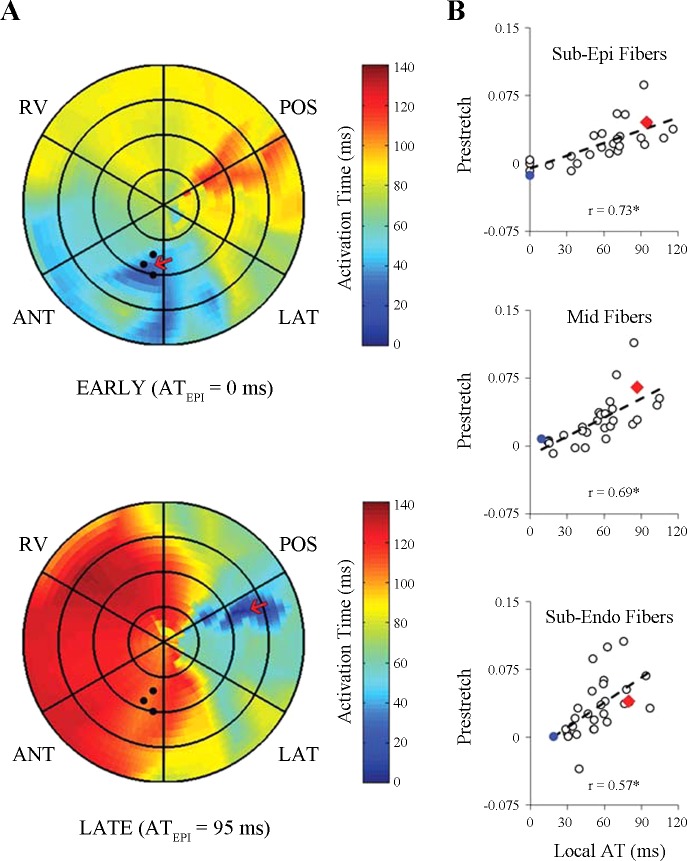

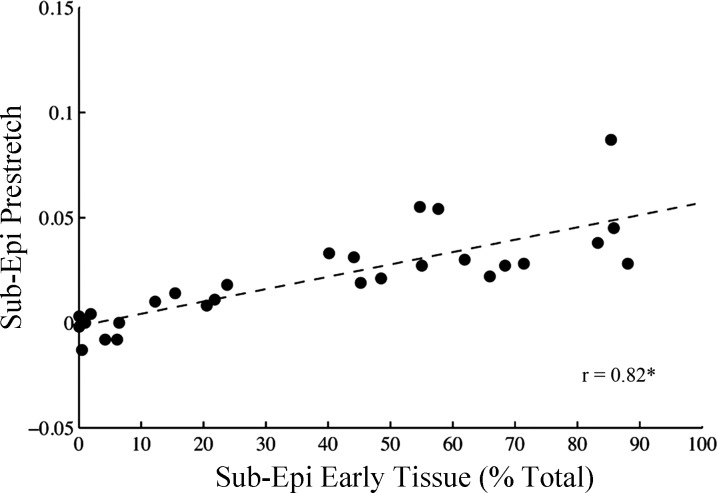

In all animals, ventricular activation at six anatomical sites (Fig. 1) resulted in a variation of local electrical activation time and fiber prestretch magnitude at the anterolateral LV. Figure 3 shows epicardial isochronal electrical activation with a bullseye plot during ventricular pacing at two sites for one representative animal (Fig. 3A). The ventricular pacing sites (red arrows) were LV anterior apex (Fig. 3A, top) and LV posterior near the coronary sinus (Fig. 3A, bottom), producing substantial differences in local activation time at the epicardium (0 vs. 95 ms) at the strain measurement site. In all experiments, the magnitude of peak fiber prestretch at subepicardium (r = 0.73, P < 0.01), midwall (r = 0.69, P < 0.01), and subendocardium (r = 0.57, P < 0.01) increased with activation time at the corresponding wall depth. Finally, the magnitude of peak fiber prestretch (Fig. 4) at the subepicardium positively correlated (r = 0.74) with the amount of early-activated tissue, as defined as percent total of the mapped epicardium, with a slope significantly different from zero (P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Varying local electrical activation time and magnitude of fiber prestretch at the anterolateral left ventricle (LV). LV wall mechanics were measured at the anterolateral LV (solid black circles), and the ventricular pacing site (red arrow) was varied to produce a range of local electrical activation times (Local AT) and fiber prestretch magnitude (Prestretch) at the strain measurement site. A: in one representative animal (dog 9), electrical activation times at the epicardium are illustrated using polar isochronal electrical activation maps obtained during ventricular pacing at 2 different anatomical sites using an epicardial 128-electrode sock. Patch color represents linearly interpolated activation times recorded by sock electrodes; color ranges from blue (0 ms) to red (120 ms). Subepicardial anterior apical (EARLY, top) and subepicardial posterior basal (LATE, bottom) pacing resulted in 2 distinct electrical activation sequences, each producing a unique local subepicardial electrical activation time (ATEPI) at the strain measurement site. B: at the strain measurement site, prestretch measured in all animals during ventricular pacing at each site (i.e., 28 total data points) was correlated with local AT for myofibers at the subepicardium (Sub-Epi Fibers, top), midwall (Mid Fibers, middle), and subendocardium (Sub-Endo Fibers, bottom). For each transmural correlation, measurements of fiber prestretch and local electrical activation time were used for each corresponding wall depth (i.e., subepicardium, midwall, or subendocardium). Data from EARLY (blue circles) and LATE (red triangles) measured in the representative animal are indicated in the regression plots. Prestretch, peak myofiber prestretch; Local AT, local electrical activation time; POS, LV posterior; RV, right ventricle; ANT, LV anterior; LAT, LV lateral. Sub-Epi, subepicardium (25% depth); Midwall (50% depth); and Sub-Endo, sub-endocardium (75% depth). r, correlation coefficient. *Slope different from zero (P < 0.01).

Fig. 4.

Fiber prestretch magnitude increases with the amount of earlier activated tissue at the subepicardium. Subepicardial peak fiber prestretch (Sub-Epi Prestretch) was correlated with the amount of subepicardial earlier-activated tissue (Sub-Epi Early Tissue), defined as percent total of the epicardial tissue area. Earlier activated tissue was determined from polar epicardial isochronal activation maps (see methods) in all animals during ventricular pacing at each site (i.e., 28 total data points). Linear regression analysis revealed a significant positive slope between Sub-Epi Prestretch and Sub-Epi Early Tissue. Sub-Epi, sub-epicardium (25% depth); r, correlation coefficient. *Slope different from zero (P < 0.001).

End-systolic fiber and radial strain magnitudes increase with prestretch magnitude.

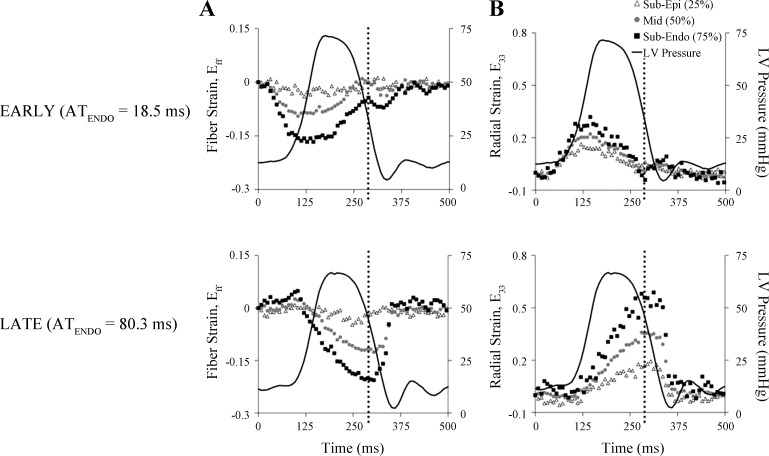

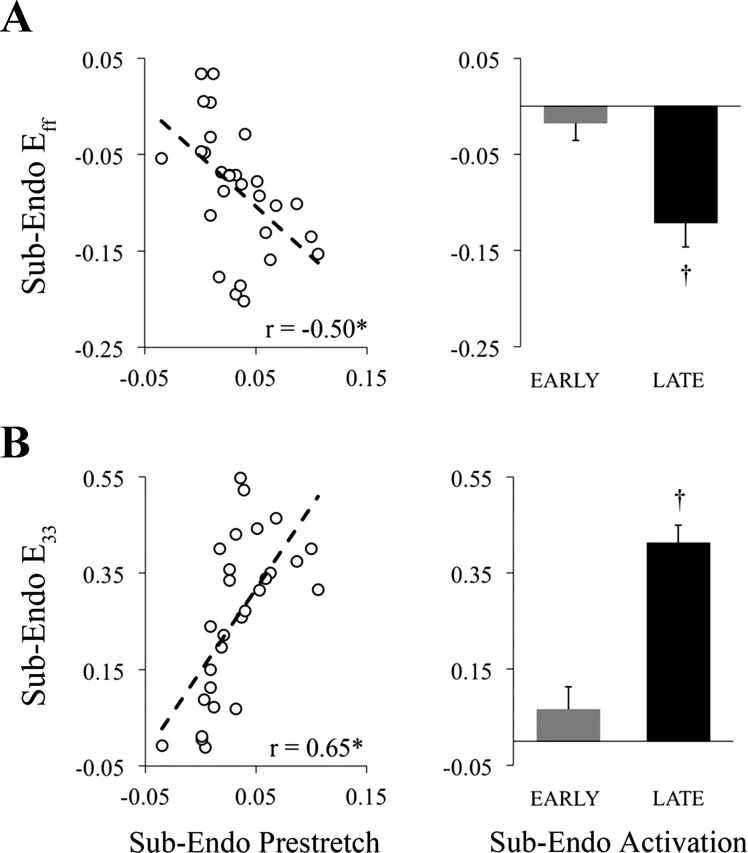

Fiber (Fig. 5A) and radial (Fig. 5B) strain throughout the cardiac cycle are shown for one animal during epicardial pacing at the LV anterior apex and LV posterior. Epicardial pacing at the LV anterior apex produced early-activated (EARLY) tissue at the measurement site, whereas epicardial pacing at the LV posterior resulted in late-activated (LATE) tissue at the measurement site. LV pressure time course and the time of end systole (dotted black line) are superimposed onto the strain time courses to illustrate timing differences, relative to global hemodynamic events, in fiber shortening (negative strain) and radial wall thickening (positive strain) between EARLY (Fig. 5, A and B; top) and LATE (Fig. 5, A and B; bottom). During EARLY activation, local fibers shortened prior to end diastole, reached peak shortening near aortic valve opening and were stretched throughout most of the ejection phase, resulting in fiber strain values near zero at end systole, whereas with LATE activation, fiber stretch (i.e., positive strain) occurred during early systole, followed by shortening throughout ejection, and peak shortening occurred near end systole. Additionally, with EARLY activation the wall thickening occurred prior to aortic valve opening, whereas with LATE activation the majority of wall thickening occurred after aortic valve opening and was maximum near end systole, thus contributing to systolic ejection. The effect of prestretch magnitude on end-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening at the subendocardium is presented in Fig. 6. Both strain components were strongly correlated with the magnitude of fiber prestretch, with significant slopes. Mean values of end-systolic fiber shortening (Fig. 6A, right) and wall thickening (Fig. 6B, right) were significantly greater in LATE compared with EARLY activated tissue at the subendocardium. Regression data for all strain components and at three transmural depths are provided in Supplemental Material available online with this article.

Fig. 5.

Differences in transmural fiber and radial strain time courses due to early and late electrical activation at the anterolateral left ventricle. Fiber strain (Eff; A) and radial strain (E33; B) at 3 transmural depths (subepicardium, midwall, and subendocardium) of the anterolateral LV are plotted throughout the cardiac cycle (in ms) for one representative animal (dog 9). Ventricular epicardial pacing at anterior apical (EARLY, top) and posterior basal (LATE, bottom) left ventricular sites resulted in marked differences in subendocardial activation time (ATENDO), as well as end-systolic strain values. Time of end systole is denoted by the black dotted line. LV pressure tracings are superimposed and synchronized with strain time courses. Reference time (0 ms) was the time of the local ventricular stimulus artifact. Sub-Epi, subepicardium (25% depth); Mid, midwall (50% depth); Sub-Endo, sub-epicardium (75% depth).

Fig. 6.

End-systolic subendocardial fiber shortening and wall thickening increase proportionally with fiber prestretch at the anterolateral left ventricle. A: end-systolic fiber shortening (negative fiber strain) at the subendocardium was correlated with the peak magnitude of fiber prestretch (Prestretch). B: subendocardial wall thickening (positive radial strain) correlated with Prestretch. End-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening strain magnitudes at the subendocardium were significantly increased for late-activated (LATE) compared with early-activated (EARLY) tissue. Sub-Endo, sub-endocardium (75% depth); Eff, fiber strain; E33, radial strain. r, correlation coefficient. *Slope different from zero (P < 0.05). †P < 0.05, EARLY vs. LATE (Student's t-test).

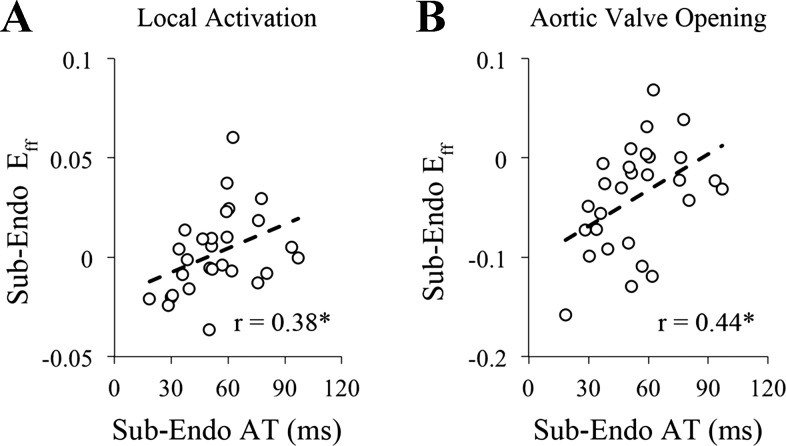

Preejection magnitude and timing parameters of fiber strain increase proportionally to local electrical activation time.

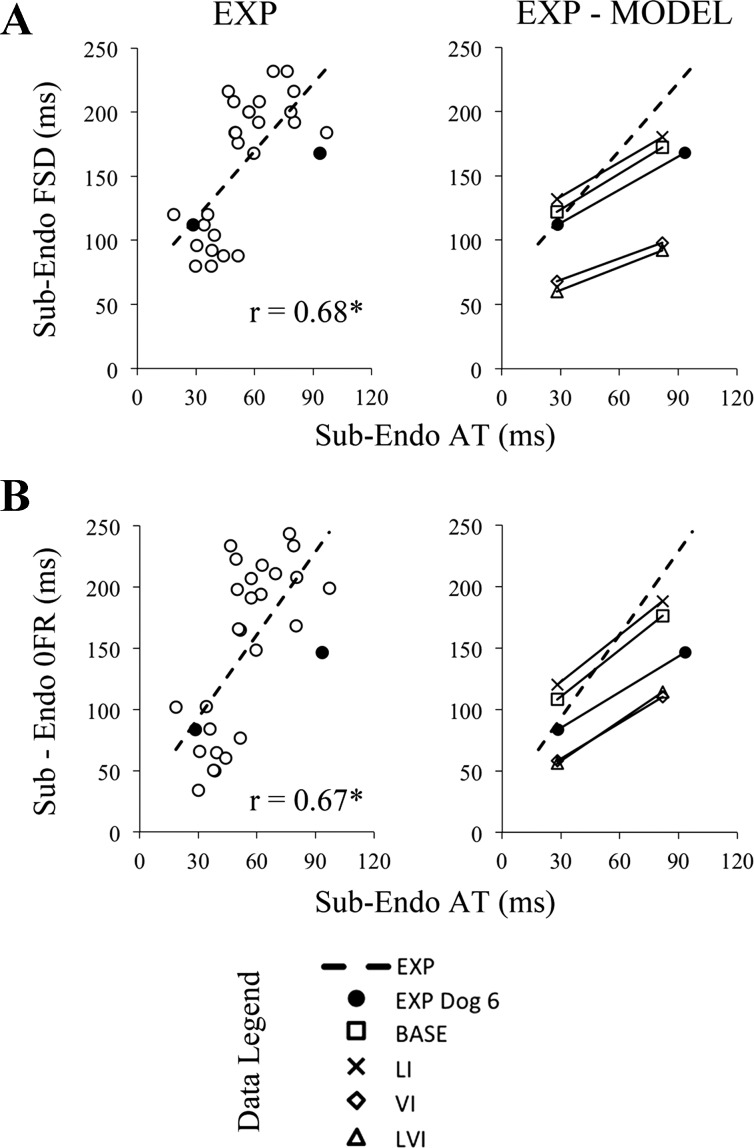

To test for differences in fiber length due to variations in local electrical activation time, fiber strain, referenced to end-diastole during atrial activation, at the time of local depolarization and aortic valve opening were determined, and results are shown in Fig. 7. Fiber strain at both the time of local electrical activation (r = 0.38) and aortic valve opening (r = 0.44) were positively correlated with local electrical activation time, and both slopes were significantly different from zero. At the subendocardium, the onset of fiber relengthening (r = 0.67) and fiber shortening duration (r = 0.68) were positively correlated with local electrical activation time, with a significant slope (P < 0.001), as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 7.

Preejection subendocardial fiber strain increases proportionally with local electrical activation time. The magnitude of subendocardial fiber strain (Eff) at the time of local electrical activation (Local Activation) (A) and aortic valve opening (B) were positively correlated with subendocardial electrical activation time (AT) at the strain measurement site, suggesting longer subendocardial fiber lengths with increasing electrical activation time in late-activated tissue compared with early-activated tissue. AT, electrical activation time; Sub-Endo, sub-endocardium (75% depth); r, correlation coefficient. *Slope different from zero (P < 0.05).

Fig. 8.

Timing in subendocardial fiber strain parameters increases proportionally with local electrical activation time from experiments and a dog-specific computational model. Fiber shortening duration (FSD; A) and the onset of fiber relengthening (OFR; B) positively correlated with local electrical activation time (AT) at the subendocardium in all experimental data (EXP, open circles, left). Increased fiber shortening duration and onset of fiber relengthening likely contribute to differences in end-systolic strains when local AT is altered at the strain measurement site. A dog-specific computational model was developed based on data collected in one animal, dog 6. Data from ventricular pacing at two sites for dog 6 (closed circles) weres compared with EXP and model simulations during pacing at identical sites (EXP-MODEL, right). In A, compared with the baseline (BASE, squares) model, removal of velocity dependence in fiber active stress generation (VI, diamonds) reduced the slope by 40%; by 20% after removal of length dependence (LI, crosses); and by 37% after removing both length and velocity dependence (LVI, triangles). In B, compared with the BASE model, VI model reduced the slope by 23%; by 11% in the LI model; and by 15% in the LVI model. Sub-Endo, sub-endocardium (75% depth); FSD, fiber shortening duration; OFR, onset of fiber relengthening; EXP, all experimental data; EXP dog 6, experimental data for dog 6 at two pacing sites; BASE, baseline active stress model; LI, length-independent active stress model; VI, velocity-independent active stress model; LVI, length- and velocity-independent active stress model; r, correlation coefficient. *Slope different from zero (P < 0.001).

Dog-specific model of prestretch.

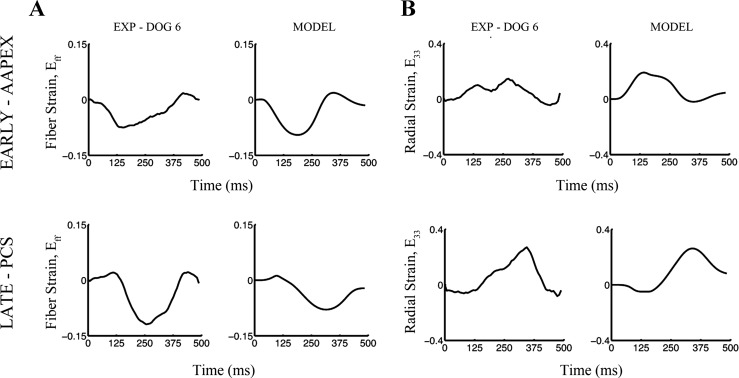

A computational approach was used to examine the effects of fiber length and shortening velocity in regulating the local response to alterations in local activation time and fiber prestretch. Global LV hemodynamics (Table 3) and local fiber and radial strain time courses (Fig. 9) calculated in the baseline dog-specific model matched well with those from the experiment.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic comparisons between experimental and dog-specific computational model data

| Pacing Site | LVEDP, mmHg | LVPmax, mmHg | LV dP/dtmax, mmHg/s |

|---|---|---|---|

| AAPEX | |||

| EXP-Dog 6 | 15 | 101 | 1,610 |

| MODEL | 15 | 103 | 1,680 |

| PCS | |||

| EXP-Dog 6 | 15 | 98 | 1,450 |

| MODEL | 15 | 95 | 1,700 |

LVEDP, end-diastolic left ventricular pressure; LVPmax, maximum left ventricular pressure; LV dP/dtmax; maximum rate of change of left ventricular pressure; AAPEX, anterior apex; PCS, posterior basal near coronary sinus; EXP, experiment; MODEL, dog-specific computational model.

Fig. 9.

Subendocardial fiber and radial strain time courses from experiment and a dog-specific computational model. Fiber (A) and radial strains (B) measured at the subendocardium of the anterolateral left ventricle are shown for one animal (EXP dog 6, left) and in a dog-specific computational model (MODEL, right) of the same animal. Early activation with anterior apical pacing of the left ventricular subepicardium (EARLY-AAPEX, top) and late activation with posterior basal near coronary sinus pacing (LATE-PCS, bottom) produced marked differences in fiber and radial strain time courses in experiment and a dog-specific model. Note the qualitative agreement between experiment and baseline model strain values and quantitative agreement regarding onset of fiber shortening and relengthening. EXP, experiment; AAPEX, anterior apical pacing; PCS, posterior basal near coronary sinus pacing.

At the subendocardial depth of the anterolateral wall, which was similar to the experimental strain measurement location, local electrical activation time for the two pacing sequences were 28.0 and 81.9 ms, respectively. The timing of the onset of fiber relengthening and fiber shortening duration were determined for the three model simulations (e.g., BASE, VI, LI, and LVI) and compared with experimental results (Fig. 8). In the BASE model both the onset of fiber relengthening (slope = 1.27) and the duration of fiber shortening (slope = 0.93) were positively correlated with local electrical activation time. Removing length dependence from the active stress model had a moderate effect on these relationships, reducing the slopes by 11% and 20%, respectively. Removing velocity dependence reduced the magnitude of the slopes by 23% and 40%, respectively. Removing both length and velocity dependence on the active stress showed a reduction in these relationships of 15% and 37% compared with baseline. Thus removing the length and velocity dependence of fiber shortening has a marginal effect on the prestretch mechanics in the failing heart.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we sought to investigate the mechanisms for increased fiber prestretch in late-activated tissue, and the role of fiber length change in determining local function in the dyssynchronous failing canine heart. We found that fiber prestretch at the subepicardium increased proportionally to the amount of earlier activated subepicardial tissue. Local end-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening were increased in the anterolateral wall in proportion to the local electrical activation time and magnitude of fiber prestretch. Increased end-systolic strain magnitudes were attributed to altered timing of strain parameters, which were sensitive to local electrical activation time. From these experimental observations, we proposed that fiber length via length-dependent activation was a primary determinant of strain timing parameters in regions of late activation and prestretch. However, in a dog-specific computational model of the failing heart, removing either or both fiber length and velocity dependence from active stress development had a small effect on the timing parameters of fiber strain (e.g., onset of fiber relengthening, fiber shortening duration), suggesting that the mechanism for changes in local strains at sites with increased electrical activation time is unlikely to be length- or velocity-dependent activation in the failing heart.

Changes in global and local function with electrical dyssynchrony in normal hearts.

In the presence of an abnormal electrical conduction, such as left-bundle branch block or with ectopic ventricular pacing, the spread of electrical activation is markedly slowed and less uniform compared with normal sinus rhythm (28, 37, 42). An altered sequence of electrical activation is associated with lower systolic blood pressures (27, 40) reduced rates of LV pressure generation and relaxation (43), and decreased LV stroke volume (9, 31). Additionally, the temporal and spatial distribution of the magnitude of contraction is altered (4, 29, 38). Badke et al. (4) observed early shortening (i.e., prior to aortic valve opening) and systolic lengthening in regions near and remote to the site of ventricular stimulus. Additional studies have shown that the onset of mechanical activation (4, 41), and magnitude of ejection shortening (9, 18), increase with the local electrical activation time, whereas Prinzen et al. (28) found that the interval between local electrical activation time and onset of shortening was nonuniform and increased in areas with greater delay in electrical activation time. Increased fiber shortening function at the subepicardial (9, 29) and mid wall (7) were previously observed in late-activated regions in normal canine hearts with ectopic ventricular activation.

Timing and magnitude changes in local strains with electrical dyssynchrony in failing hearts.

In the present study, we found that fiber prestretch at the subepicardium increased proportionally to the amount of earlier activated tissue at the subepicardium, which provided further insights into the determinants of fiber prestretch. By prolonging local electrical activation time, late-activated fibers may remain passive for a longer duration of time and could be susceptible to stretching due to early activated, stress-generating fibers. A previous modeling study suggested that prestretch could be a result of a regional imbalance of regional stiffness and the governing principle of force equilibrium (19), which would require spatial variation of fiber length and stretching of late-activated fibers.

Our results on the effects of prestretch on local end-systolic fiber and radial strain provide new insights into the role of increased fiber prestretch in failing tissue with altered electrical activation timing. Specifically, at the subendocardium, end-systolic fiber shortening and radial wall thickening strain values increased proportionally with fiber prestretch magnitude and were significantly greater for late-activated tissue compared with early-activated tissue (Fig. 6). Our choice of using fiber prestretch as an independent predictor of end-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening strains was based on the inherit contractile nature of the myofilament. At the tissue level, helical arrangement of myofibers, the transmural gradient in fiber orientation, and transmural differences in cellular properties collectively result in complex, heterogeneous 3D deformation. Thus factors that regulate fiber strain function (e.g., length, shortening velocity) are likely to also determine other strain values (e.g., radial strain, transverse shear strain). Our findings support the hypothesis that increased magnitudes of fiber prestretch result in greater magnitudes of systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening at the subendocardium (Fig. 6), as well as other normal and shear strains at various wall depths (see online Supplemental Material).

We attributed differences in end-systolic strain magnitudes between early- and late-activated tissue to differences in the timing of strain parameters. Particularly with regard to fiber shortening, both the onset of fiber relengthening and fiber shortening duration were positively correlated with local activation time.

Role of fiber length and shortening velocity on fiber shortening function.

In failing hearts, we compared subendocardial preejection fiber strain at the times of local activation and aortic valve opening during ventricular pacing at multiple sites using a common geometric reference, specifically atrial end diastole. At both time points, we found that the magnitude of fiber strain positively correlated with local activation time, and hence was greater in regions with larger magnitudes of prestretch. In addition, the onset of fiber relengthening and duration of fiber shortening were prolonged with increasing local activation time (Fig. 8), which could be a result of the increase in fiber length prior to local activation. Additional studies, in isolated skeletal muscle fibers, found that the magnitude and duration of force development were increased with longer fiber length prior to stimulation, compared with shorter lengths (11). It is generally thought that the increase in force development is directly due to increased calcium sensitivity with increasing sarcomere length within physiological limits (16), yet the exact mechanism by which increased sarcomere length enhances calcium sensitivity is unclear. Additionally, active shortening decreases the amount of strong bound cross-bridges (13, 32) and reduces the ability to generate force in a process of shortening deactivation (22, 23). In late-activated regions, the onset of fiber shortening was delayed and occurred against greater systolic pressure (Fig. 5). Thus differences in the onset of fiber relengthening and shortening duration could also be explained by processes involving shortening deactivation, which would be exaggerated in early-activated regions that presumably shorten at greater velocities due to low intracavity pressure prior to global ventricular ejection.

Insights from a computational model on the mechanisms regulating the effect of prestretch on local strains differences between early and late activated tissue.

Length dependence of force development (36), rate of fiber shortening (8, 12), afterload (9), cross-bridge cycling kinetics (5), and mechanoelectric feedback (20) are likely to contribute to the differences in magnitude and timing of local stain values in the failing heart. To probe potential mechanisms for changes in strain timing parameters, we developed a dog-specific computational model based upon in vivo hemodynamic data, high-resolution biventricular geometry and fiber architecture, and similar anatomical pacing and strain measurement sites. In our baseline model simulations, in which active stress development depended on fiber length and shortening velocity, differences in strain timing parameters (e.g., shortening duration, and onset of relengthening) between early and late activation were similar to experimental results (Fig. 8). Removing length and/or velocity dependence had a marginal effect on this difference. While factors other than hemodynamics, activation time, fiber length, and shortening velocity were not included in the active stress model, the results suggest that other mechanisms are likely involved in the effects of prestretch on local systolic function.

Experimental limitations.

In the present study we measured local function in the anterolateral left ventricles of open-chest, anesthetized failing canine hearts at steady-state during ventricular ectopic pacing. Thus our findings characterize the acute response to alterations in local activation time and prestretch in the chronic failing canine heart and may not represent the mechanical response in closed-chest, conscious animals. During the terminal pacing study, inotropic support was provided intravenously to maintain a sustainable hemodynamic state. As a result, myocardial contractility and the dynamics of activation and relaxation may have been altered. We suspect that inotropic support was likely to have a small effect on the regional mechanical function, but we did not quantitatively verify these differences. Three-dimensional strains were measured in vivo with a defined cardiac coordinate system; postmortem dissections in the fixed excised heart were used to define a local material coordinate system. Histological data on the mean fiber angle at the strain measurement site was used to define a strain coordinate system with one of the axes aligned to the long axis of the fiber. The primary assumption in this methodology is that fibers lay in plane parallel to the epicardial tangent plane thus allowing for a simple in-plane rotation of the cardiac coordinates. Thus out-of-plane contributions to fiber strain would be unaccounted for in the current method. Additionally, the possibility for local distortion in the region of strain measurement due to fixation at low LV cavity pressures could be a potential source of error; however, to minimize this error we corrected for deformations that occurred due to fixation and cavity pressure change by calculating a fiber angle change resulting from a deformation from the fixed low-pressure state to the in vivo end-diastolic state. We did not find a statistical effect of left ventricular pacing site on global hemodynamic loading (e.g., EDP) and function (LVPmax, dP/dtmax). We attributed this to interanimal variability in hemodynamic response to ventricular pacing at the various anatomical sites and possibly to the differences in inotropic support. Thus it is possible that grouping data based on common anatomical sites may have masked intra-animal differences that were present between pacing sites. Finally, there is much clinical interest in the optimal placement of the left ventricular lead during biventricular pacing, also referred to as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). The functional implications of prestretch on CRT and lead placement are beyond the scope of this study and warrant future studies, specifically utilizing tools that can adequately give global assessments of local function (e.g., MRI tracking) to correlate sites for optimal pacing to baseline mechanical function (e.g., site of greatest prestretch).

Modeling limitations.

The Arts active stress model used in the dog-specific model does not include the mechanics of shortening deactivation. Removal of velocity and length dependence did change the relation between local activation time and fiber shortening duration, but did not completely eliminate it. Therefore, shortening deactivation may be one mechanism responsible for the remaining effects on the latter relation, and was not implemented in the current model. Mitral regurgitation may have occurred in the dilated failing dog hearts, although we do not have any direct measurement to support this. Such regurgitation could affect the ventricular pressure, but was not part of the model used here. Another possible effect that was not taken into account is a difference in regional electromechanical delay due to the rate of change of ventricular pressure (33).

Conclusions.

In the present study with dyssynchronous failing hearts, local end-systolic fiber shortening and wall thickening strains were found to increase in proportion to the magnitude of fiber prestretch, primarily at the subendocardium. Additionally, at the subepicardium, fiber prestretch magnitude increased with greater amounts of early-activated tissue, suggesting that prestretch is determined in part by early shortening near the pacing site. Overall, these findings suggest that even with depressed length-dependent activation, the effects of prestretch on local fiber function in the dyssynchronous failing canine heart are similar to those previously found in the normal heart.

GRANTS

This study was supported by a University of California Discovery Grant ITL06-10159 (A. D. McCulloch) that was cosponsored by Medtronic. Additional support was provided National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HL-46345 (A. D. McCulloch), RR-08605 (A. D. McCulloch), HL-096544 (A. D. McCulloch), and HL-32583 (J. H. Omens), and by National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship DGE-1144086 (K. P. Vincent)

DISCLOSURES

L. J. Mulligan is an employee of Medtronic. Primary funding for this study was provided by a University of California Discovery Grant ITL06-10159 (A.D. McCulloch) that was cosponsored by Medtronic. Medtronic provided implantable electrodes, programmable pacemakers, surgical and interrogatory accessories, and technical support.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: E.J.H., R.C.K., L.J.M., A.D.M., and J.H.O. conception and design of research; E.J.H., R.C.K., and J.H.O. performed experiments; E.J.H., R.C.K., K.P.V., A.K., C.T.V., A.D.M., and J.H.O. analyzed data; E.J.H., R.C.K., K.P.V., A.K., C.T.V., A.D.M., and J.H.O. interpreted results of experiments; E.J.H., K.P.V., A.K., and C.T.V. prepared figures; E.J.H. drafted manuscript; E.J.H., R.C.K., K.P.V., A.D.M., and J.H.O. edited and revised manuscript; E.J.H., R.C.K., K.P.V., A.K., C.T.V., L.J.M., A.D.M., and J.H.O. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. James Covell and Bruce Ito for their support with the surgical preparation and fruitful discussions. We also thank Dr. Morton Printz for supplying us with the implantable left atrial pressure transducers and telemetric monitoring system. We are particularly indebted to Dr. Irina Ellrott, DVM, without whose surgical and veterinary skills these difficult chronic heart failure preparations would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashikaga H, Criscione JC, Omens JH, Covell JW, Ingels NB., Jr Transmural left ventricular mechanics underlying torsional recoil during relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H640–H647, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashikaga H, Omens JH, Ingels NB, Jr, Covell JW. Transmural mechanics at left ventricular epicardial pacing site. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2401–H2407, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baan J, van der Velde E, de Bruin H, Smeenk G, Koops J, van Dijk A, Temmerman D, Senden J, Buis B. Continuous measurement of left ventricular volume in animals and humans by conductance catheter. Circulation 70: 812–823, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Badke FR, Boinay P, Covell JW. Effects of ventricular pacing on regional left ventricular performance in the dog. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 238: H858–H867, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Campbell KB, Simpson AM, Campbell SG, Granzier HL, Slinker BK. Dynamic left ventricular elastance: a model for integrating cardiac muscle contraction into ventricular pressure-volume relationships. J Appl Physiol 104: 958–975, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Coleman HN, Taylor RR, Pool PE, Whipple GH, Covell JW, Ross J, Braunwald E. Congestive heart failure following chronic tachycardia. Am Heart J 81: 790–798, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coppola BA, Covell JW, McCulloch AD, Omens JH. Asynchrony of ventricular activation affects magnitude and timing of fiber stretch in late-activated regions of the canine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H754–H761, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Tombe P, ter Keurs H. Force and velocity of sarcomere shortening in trabeculae from rat heart. Effects of temperature. Circ Res 66: 1239–1254, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Delhaas T, Arts T, Prinzen FW, Reneman RS. Relation between regional electrical activation time and subepicardial fiber strain in the canine left ventricle. Pflügers Arch 423: 78–87, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frank LR, Jung Y, Inati S, Tyszka JM, Wong EC. High efficiency, low distortion 3D diffusion tensor imaging with variable density spiral fast spin echoes (3D DW VDS RARE). Neuroimage 49: 1510–1523, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon AM, Ridgway EB. Length-dependent electromechanical coupling in single muscle fibers. J Gen Physiol 68: 653–669, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hill AV. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc R Soc London Series B Biol Sci 126: 136–195, 1938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Housmans P, Lee N, Blinks Active shortening retards the decline of the intracellular calcium transient in mammalian heart muscle. Science 221: 159–161, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howard EJ, Covell JW, Mulligan LJ, McCulloch AD, Omens JH, Kerckhoffs RCP. Improvement in pump function with endocardial biventricular pacing increases with activation time at the left ventricular pacing site in failing canine hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1447–H1455, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Issa ZF, Rosenberger J, Groh WJ, Miller JM, Zipes DP. Ischemic ventricular arrhythmias during heart failure: a canine model to replicate clinical events. Heart Rhythm 2: 979–983, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kentish J, ter Keurs H, Ricciardi L, Bucx J, Noble M. Comparison between the sarcomere length-force relations of intact and skinned trabeculae from rat right ventricle. Influence of calcium concentrations on these relations. Circ Res 58: 755–768, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kerckhoffs RC, Neal ML, Gu Q, Bassingthwaighte JB, Omens JH, McCulloch AD. Coupling of a 3D finite element model of cardiac ventricular mechanics to lumped systems models of the systemic and pulmonic circulation. Ann Biomed Eng 35: 1–18, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kerckhoffs RCP, Faris OP, Bovendeerd PHM, Prinzen FW, Smits K, McVeigh ER, Arts T. Electromechanics of paced left ventricle simulated by straightforward mathematical model: comparison with experiments. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H1889–H1897, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kerckhoffs RCP, Omens JH, McCulloch AD, Mulligan LJ. Ventricular dilation and electrical dyssynchrony synergistically increase regional mechanical nonuniformity but not mechanical dyssynchrony. Clinical perspective. Circ Heart Failure 3: 528–536, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kohl P, Hunter P, Noble D. Stretch-induced changes in heart rate and rhythm: clinical observations, experiments and mathematical models. Progress Biophys Mol Biol 71: 91–138, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Krishnamurthy A, Villongco CT, Chuang J, Frank LR, Nigam V, Belezzuoli E, Stark P, Krummen DE, Narayan S, Omens JH, McCulloch AD, Kerckhoffs RCP. Patient-specific models of cardiac biomechanics. J Comput Physics 244: 4–21, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leach JK, Brady AJ, Skipper BJ, Millis DL. Effects of active shortening on tension development of rabbit papillary muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 238: H8–H13, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leach JK, Priola DV, Grimes LA, Skipper BJ. Shortening deactivation of cardiac muscle: physiological mechanisms and clinical implications. J Investig Med 47: 369–377, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lumens J, Delhaas T, Kirn B, Arts T. Three-wall segment (TriSeg) model describing mechanics and hemodynamics of ventricular interaction. Annals Biomed Eng 37: 2234–2255, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. MacKay SA, Potel MJ, Rubin JM. Graphics methods for tracking three-dimensional heart wall motion. Comput Biomed Res 15: 455–473, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meier GD, Ziskin MC, Santamore WP, Bove AA. Kinematics of the beating heart. Biomed Eng IEEE Transact BME-27: 319–329, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park R, Little W, O'Rourke R. Effect of alteration of left ventricular activation sequence on the left ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relation in closed-chest dogs. Circ Res 57: 706–717, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prinzen FW, Augustijn CH, Allessie MA, Arts T, Delhass T, Reneman RS. The time sequence of electrical and mechanical activation during spontaneous beating and ectopic stimulation. Eur Heart J 13: 535–543, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Prinzen FW, Augustijn CH, Arts T, Allessie MA, Reneman RS. Redistribution of myocardial fiber strain and blood flow by asynchronous activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 259: H300–H308, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prinzen FW, Hunter WC, Wyman BT, McVeigh ER. Mapping of regional myocardial strain and work during ventricular pacing: experimental study using magnetic resonance imaging tagging. J Am Coll Cardiol 33: 1735–1742, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Prinzen FW, Peschar M. Relation between the pacing induced sequence of activation and left ventricular pump function in animals. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 25: 484–498, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ridgway EB, Gordon AM. Muscle calcium transient. Effect of post-stimulus length changes in single fibers. J Gen Physiol 83: 75–103, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Russell K, Smiseth OA, Gjesdal O, Qvigstad E, Norseng PA, Sjaastad I, Opdahl A, Skulstad H, Edvardsen T, Remme EW. Mechanism of prolonged electromechanical delay in late activated myocardium during left bundle branch block. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H2334–H2343, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takayama Y, Costa KD, Covell JW. Contribution of laminar myofiber architecture to load-dependent changes in mechanics of LV myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1510–H1520, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Usyk T, McCulloch AD. Electromechanical model of cardiac resynchronization in the dilated failing heart with left bundle branch block. J Electrocardiol 36: 57–61, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Heuningen R, Rijnsburger WH, ter Keurs HE. Sarcomere length control in striated muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 242: H411–H420, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vassallo JA, Cassidy DM, Miller JM, Buxton AE, Marchlinski FE, Josephson ME. Left ventricular endocardial activation during right ventricular pacing: effect of underlying heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 7: 1228–1233, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Waldman LK, Covell JW. Effects of ventricular pacing on finite deformation in canine left ventricles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 252: H1023–H1030, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Waldman LK, Fung YC, Covell JW. Transmural myocardial deformation in the canine left ventricle. Normal in vivo three-dimensional finite strains. Circ Res 57: 152–163, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wiggers CJ. The muscular reactions of the mammalian ventricles to artificial surface stimuli. Am J Physiol 73: 345–378, 1925 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wyman BT, Hunter WC, Prinzen FW, McVeigh ER. Mapping propagation of mechanical activation in the paced heart with MRI tagging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H881–H891, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wyndham C, Smith T, Meeran M, Mammana R, Levitsky S, Rosen K. Epicardial activation in patients with left bundle branch block. Circulation 61: 696–703, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zile MR, Blaustein AS, Shimizu G, Gaasch WH. Right ventricular pacing reduces the rate of left ventricular relaxation and filling. J Am Coll Cardiol 10: 702–709, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.