Abstract

Picrotoxin is extensively and specifically used to inhibit GABAA receptors and other members of the Cys-loop receptor superfamily. We find that picrotoxin acts independently of known Cys-loop receptors to shorten the period of the circadian clock markedly by specifically advancing the accumulation of PERIOD2 protein. We show that this mechanism is surprisingly tetrodotoxin-insensitive, and the effect is larger than any known chemical or genetic manipulation. Notably, our results indicate that the circadian target of picrotoxin is common to a variety of human and rodent cell types but not Drosophila, thereby ruling out all conserved Cys-loop receptors and known regulators of mammalian PERIOD protein stability. Given that the circadian clock modulates significant aspects of cell physiology including synaptic plasticity, these results have immediate and broad experimental implications. Furthermore, our data point to the existence of an important and novel target within the mammalian circadian timing system.

Keywords: circadian, Cys-loop receptor, GABA receptor, picrotoxin

circadian clocks drive near 24-h rhythms in >10% of the genome and modulate daily changes in cellular metabolism and physiology (Herzog 2007; Panda et al. 2002). The period of circadian oscillations is temperature-compensated and remains remarkably resistant to pharmacological challenge. For example, a recent chemical screen of 1,280 active compounds reported no agents capable of dose-dependently shortening circadian periodicity by >4 h (Hirota et al. 2008). Here, we find that the classic GABAA receptor antagonist, picrotoxin, dramatically shortens circadian rhythms in gene expression in single cells and across multiple tissues. Surprisingly, this effect is independent of known Cys-loop receptors, including GABAA receptors. Importantly, we find that picrotoxin significantly decreases the period of circadian oscillations at concentrations routinely used in cellular and systems neuroscience.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Period2Luciferase (PER2::LUC) knock-in mice (Yoo et al. 2004; founders generously provided by J. S. Takahashi) and Period1::luc rats were housed in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and bred as homozygous pairs in the Danforth Animal Facility at Washington University. Timeless::luciferase (Tim::Luc) Drosophila melanogaster (Stanewsky et al. 1997), generously provided by P. H. Taghert, were grown on standard molasses and yeast medium at room temperature and on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University and followed National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines.

Cell lines.

Primary human astrocytes (generously provided by J. B. Rubin) were maintained at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin/streptomycin.

Gene reporter construct.

We performed lentiviral infections of pure human astrocyte cultures using a lentiviral construct expressing the Per2::dLuc reporter (Liu et al. 2008; Zhang et al. 2009). Astrocytes were incubated with the viral particles for 12 h, washed, and passaged twice over a 2-wk period before plating and imaging.

Mammalian bioluminescence recording.

For suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) explant recordings, 300-μm coronal SCN slices from PER2::LUC mice (age 7–14 days) were cultured at 34°C on Millicell CM membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in sealed 35-mm culture dishes (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) with prewarmed air-buffered medium and 100 μM beetle luciferin (Promega, Madison, WI). Bioluminescence was recorded using a photomultiplier tube (PMT; HC135-11 MOD; Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan) as previously described (Abe et al. 2002). Bioluminescence counts were integrated and stored at 1-min intervals for up to 18 days of recording. For single-cell recordings, explants were cultured for 4 days on Millicell CM membranes, inverted onto polylysine/laminin-coated glass coverslips in prewarmed air-buffered medium with 100 μM beetle luciferin, and imaged (VersArray 1024 cooled CCD camera; Princeton Instruments). Photon counts were integrated over 10–30 min with 2 × 2 binning and quantified using ImageJ software. For lung explant recordings, lung tissue from 14-day-old PER2::LUC mice was dissected and placed onto Millicell CM membranes. Tissue was cultured with air-buffered medium, 100 μM beetle luciferin, nystatin (20 μg/ml), and amphotericin B (0.25 μg/ml; Sigma). Bioluminescence was recorded using a PMT, and counts were integrated at 6-min intervals.

Drosophila bioluminescence recordings.

Abdomens and wings of male Tim::Luc flies were dissected and placed individually in 96-well plates containing Schneider's Insect Medium supplemented with 12% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 100 μM beetle luciferin (Giebultowicz et al. 2000). The plate was imaged at 30 frames per second using an XR/MEGA-10Z CCD camera placed in a light-tight, temperature-controlled box at 25°C (Stanford Photonics, Palo Alto, CA). Images were then integrated every 60 min using ImageJ software.

Electrophysiology.

Long-term recordings of firing rate from high-density dispersed SCN neurons were made using multielectrode arrays (Multi Channel Systems, Reutlingen, Germany). To disperse cells, SCN were punched from 300-μm-thick slices, and cells were dissociated using papain (Herzog et al. 1998). Viable cells (from 10–14 SCN) were plated on 60 30-μm-diameter electrodes (200-μm spacing) and maintained in CO2-buffered medium for 3 wk before recording. Culture chambers fixed to arrays were covered with a fluorinated ethylene-polypropylene membrane (Potter and DeMarse 2001) before transfer to recording incubator. The recording incubator was maintained at 36°C with 5% CO2 throughout all experiments. Extracellular voltage signals were recorded for a minimum of 10 days from 60 electrodes simultaneously. Action potentials exceeding a defined voltage threshold were digitized into 2-ms time-stamped cutouts (MC_Rack software; Multi Channel Systems). Spikes from individual neurons were discriminated offline using a principal component analysis-based system (Offline Sorter; Plexon), and firing rates were calculated over 1-min recording epochs (NeuroExplorer; Plexon). Correct discrimination of single-neuron activity was ensured by the presence of a clear refractory period in autocorrelograms of firing records (NeuroExplorer).

Measurement of CK1ε activity.

Casein kinase 1ε (CK1ε) activity was measured by coincubation of the purified enzyme with a synthetic peptide substrate derived from the βTrCP-binding region of mouse PER2, and CK1ε kinase activity was assayed using the P81 phosphocellulose assay (Isojima et al. 2009).

Drug treatments.

Picrotoxin, picrotoxinin, bicuculline, strychnine, U73122, TBPS (Dillon et al. 1995), NPPB, MDL-12,330A, TTX, and TPMPA (generously provided by P. D. Lukasiewicz) were purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO). SR-95531 (gabazine), (+)-tubocurarine (Yan et al. 1998), and 9-anthracene-carboxylate (9-AC) were purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO). All drugs were diluted in deionized water, 95% ethanol, or DMSO and stored at either −20 or 4°C depending on manufacturer instructions. A volume of concentrated stock solution (<0.5% of total volume) was applied to each culture.

Data analysis.

Continuous recordings of gene expression or firing records lasting at least 4 days were used for analysis of rhythmicity. Circadian period of explant rhythmicity was calculated using χ2-periodogram analysis (Sokolove and Bushell 1978); period for single-cell gene expression and Drosophila was calculated by FFT-NLLS (Plautz et al. 1997). Confidence intervals were set to 99 and 95% for χ2-periodogram and FFT-NLLS, respectively. Additional statistical tests were done with Origin 7 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Mean periods (for Figs. 1C, 1F, and 3A) were compared by one-way ANOVA and Scheffé post hoc tests. Mean periods for other analyses were compared by two-tailed t-tests. Distributions of periods were compared using both Levene's and Brown-Forsythe's tests for equal variance.

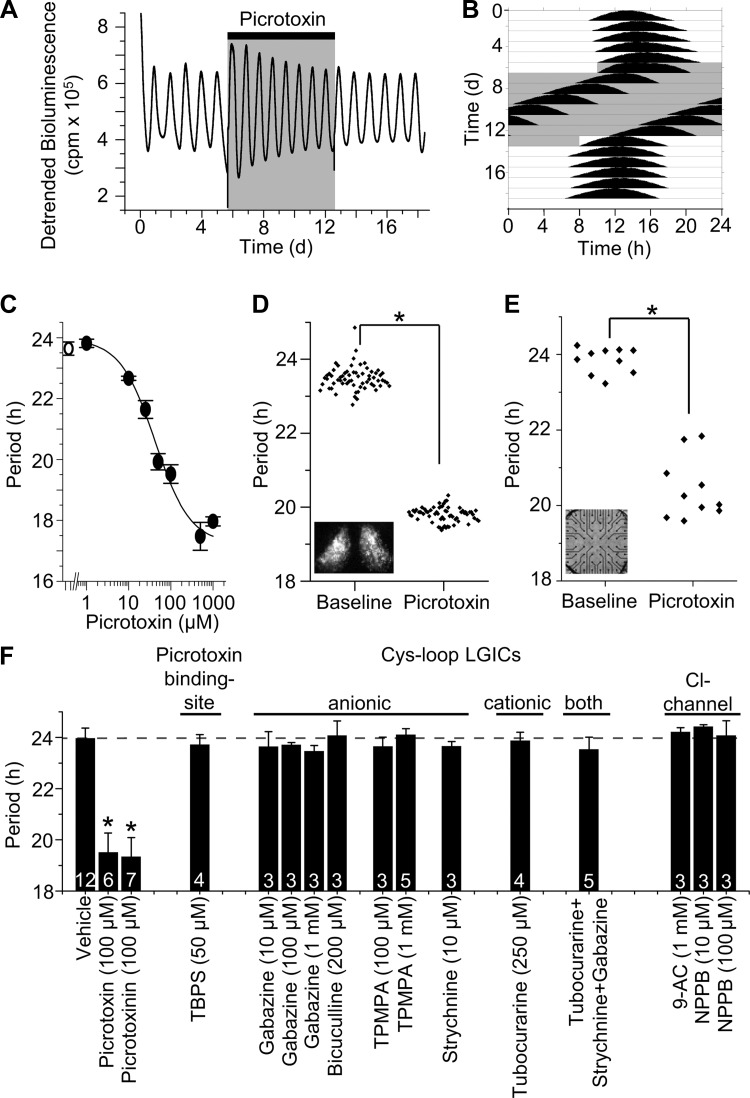

Fig. 1.

Picrotoxin reversibly and dose-dependently shortens the period of the circadian clock independent of Cys-loop receptors. A: real-time monitoring of Period2Luciferase (PER2::LUC) expression from a representative suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) explant shows that 100 μM picrotoxin treatment (shaded box) had no effect on rhythm amplitude. cpm, Counts per minute; d, days. B: plotting the same data as an actogram reveals that picrotoxin rapidly shortened period from 24.4 to 20.6 h during treatment (shaded box). Period rapidly recovered to baseline (24.1 h) following washout. C: the effect of picrotoxin was concentration-dependent (1 μM, P > 0.05; 10 μM, P < 0.005; 25, 50, 100, 500, and 1,000 μM, P < 0.001; 1-way ANOVA vs. vehicle; means ± SE, n = 4–6 SCN explants per concentration). Line represents a sigmoidal fit to the data. D: picrotoxin (100 μM) shortens periodicity of PER2::LUC expression in single neurons within an SCN explant (inset; n = 64 neurons; *P < 0.001, Student's t-test). E: picrotoxin speeds circadian rhythms in firing activity of neurons recorded on a multielectrode array (inset; n = 10 neurons; *P < 0.001). F: pharmacological block of Cys-loop receptors and Cl− channels does not affect period. Picrotoxin and picrotoxinin shortened PER2::LUC rhythms, however, alternative inhibitors of Cys-loop receptors or Cl− channels do not shorten period (means ± SD, the number of SCN explants is indicated for each treatment). Asterisk indicates significant difference compared with vehicle (P < 0.001; 1-way ANOVA). Dashed line indicates mean of vehicle treatment. LGICs, ligand-gated ion channels; TBPS, tert-butylbicyclophosphorothionate; TPMPA, (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl)methylphosphinic acid; NPPB, 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropylamino)benzoic acid; 9-AC, 9-anthracene-carboxylate.

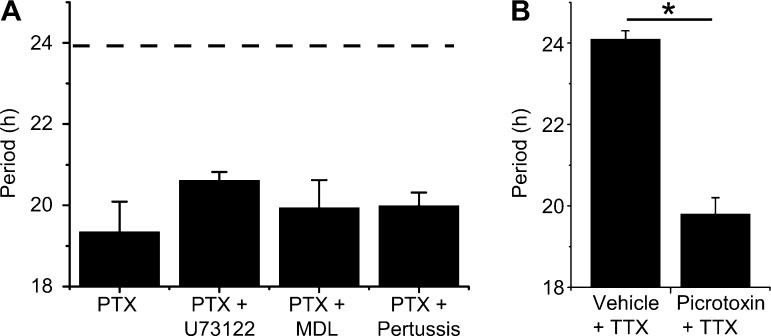

Fig. 3.

Picrotoxin speeds circadian rhythmicity independent of G-protein-coupled-receptor- or action potential-dependent signaling. A: picrotoxinin (PTX; 100 μM, n = 7) reduced circadian period (19.3 ± 0.7 h) of SCN explants. Cotreatment with picrotoxinin and inhibitors of Gq-phospholipase C (20.6 ± 0.2 h, U73122, 10 μM, n = 3), Gs-adenylyl cyclase [19.9 ± 0.7 h, MDL-12,330A (MDL), 2.5 μM, n = 3], or Gi/o/t (19.9 ± 0.3 h, pertussis toxin, 5 nM, n = 3) did not lessen the effect of picrotoxinin (1-way ANOVA, P > 0.05 vs. picrotoxinin). Data represent means ± SE. Dashed line represents mean period of vehicle-treated cultures. B: TTX (2 μM) does not abrogate picrotoxin-induced period shortening of PER2::LUC rhythmicity in SCN explants. *P < 0.0001. Data represent means ± SE, n = 3–4 independent SCN explants per treatment.

RESULTS

Picrotoxin speeds the circadian clock within the central mammalian pacemaker.

To measure the effect of picrotoxin on circadian rhythmicity, we monitored a bioluminescent reporter of PERIOD2 (PER2) protein expression from SCN of Period2Luciferase mice. SCN explants generate sustained and stable daily rhythms and are therefore ideally suited for testing period effects of drugs (Fig. 1A). We found that within one cycle, a frequently used experimental concentration of picrotoxin (100 μM) decreased the period of PER2 rhythms from 23.9 ± 0.3 to 19.8 ± 0.1 h (n = 4; Fig. 1B) but did not affect the peak-to-trough amplitude (ratio of 3rd day of picrotoxin treatment to the 3rd day of baseline was 1.1 ± 0.2, n = 4). Circadian period shortened dramatically with increasing picrotoxin concentration, saturating at ∼500 μM with a period of 17.4 ± 0.4 h (Fig. 1C). Picrotoxin was similarly effective on rat SCN, significantly accelerating rhythmicity of a luciferase reporter for Period1 transcriptional activity (vehicle, 25.5 ± 0.6 h; 100 μM picrotoxin, 19.2 ± 0.1 h; n = 3–5; P < 0.00001).

The SCN consists of a broad range of neural subgroups, differentiated according to neuropeptide content (van den Pol and Tsujimoto 1985), oscillatory behavior (Moore et al. 2002; Shinohara et al. 1995; Webb et al. 2009), and connectivity (Leak and Moore 2001; Moga and Moore 1997). To test whether picrotoxin decreases periodicity in all SCN cells or only a subset, we monitored PER2 expression in individual neurons within an SCN explant. We found that picrotoxin decreased periodicity in all measured SCN neurons (baseline, 23.5 ± 0.1 h; picrotoxin, 19.8 ± 0.1 h; n = 64 neurons; P < 0.00001; Fig. 1D). Importantly, picrotoxin also shortened rhythms in firing rate of individual SCN neurons dispersed on a multielectrode array (baseline, 23.9 ± 0.1 h; picrotoxin, 20.4 ± 0.2 h; n = 10 neurons; P < 0.00001; Fig. 1E).

Picrotoxin alters clock function independent of Cys-loop receptors.

These effects of picrotoxin, although highly reliable and reversible, appeared to contradict a prior report that blockade of GABAA receptors had no effect on circadian period (Aton et al. 2006). To examine the mechanism of the effect of picrotoxin on circadian rhythmicity, we first tested the necessity of inhibiting Cys-loop receptor picrotoxin-binding sites. Whereas picrotoxin or its constituent, picrotoxinin, reliably decreased the period of circadian oscillations, the chemically distinct competitor for the picrotoxin-binding site, TBPS (Squires et al. 1983), did not (Fig. 1F). Furthermore, pre- and cotreatment with equimolar TBPS did not abrogate the period-reducing effect of 50 μM picrotoxin (vehicle+picrotoxin, −1.91 ± 0.19 h; TBPS+picrotoxin, −1.91 ± 0.12 h, n = 5 per group; P = 1). Given that picrotoxin can inhibit other members of the Cys-loop receptor superfamily (Erkkila et al. 2004), we systematically tested antagonists of known picrotoxin targets on SCN rhythmicity (Fig. 1F). Blockade of the anionic Cys-loop receptors, GABAA receptors (with gabazine or bicuculline), GABAA-ρ receptors (with TPMPA), and glycine receptors (with strychnine) all failed to alter periodicity (P > 0.05). Antagonism of the cationic Cys-loop receptors, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, and 5-HT3 receptors (with d-tubocurarine) was also ineffective (P > 0.05). Simultaneous application of gabazine (500 μM), strychnine (50 μM), and d-tubocurarine (250 μM) also did not alter SCN periodicity (P > 0.05). Together, these results indicate that picrotoxin acts independently of known Cys-loop receptor targets to shorten the period of the circadian clock.

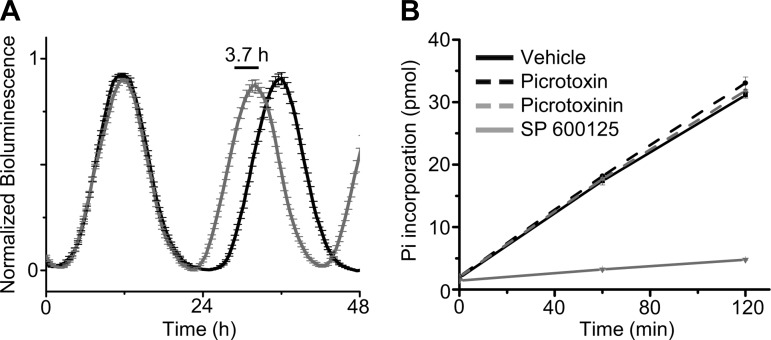

Picrotoxin specifically accelerates PER2 protein accumulation without altering CK1ε activity.

To gain insight into the mechanism by which picrotoxin speeds the molecular clock, we analyzed the waveform of PER2 expression in individual cells recorded in an SCN explant. Period shortening could result through uniform compression of the waveform, however, we found that 100 μM picrotoxin selectively advanced the accumulation of PER2 protein by ∼3.7 h without affecting PER2 stability or degradation as measured by peak half-width (baseline, 8.7 h; picrotoxin, 8.6 h; calculated from averaged traces of 50 randomly selected neurons; Fig. 2A). Additionally, we directly monitored the effect of picrotoxin on CK1ε, a key posttranslational regulator of PER2 stability in vivo (Takahashi et al. 2008). We found that neither picrotoxin (100 μM) nor picrotoxinin (100 μM) altered CK1ε kinase activity (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data suggest that picrotoxin acts independently of known posttranslational mechanisms specifically to speed daily PER2 accumulation.

Fig. 2.

Picrotoxin shortens period by advancing accumulation of PER2 protein without altering casein kinase 1ε (CK1ε) activity. A: PER2::LUC rhythms of single SCN cells under baseline (black) and picrotoxin (gray) conditions were phase-aligned, averaged, and normalized to peak (means ± SE, n = 50). Picrotoxin advances the accumulation of PER2 protein on subsequent days (3.7 h) but does not alter rhythm half-width. B: CK1ε kinase activity was assessed by the rate of phosphate incorporation of PER2 peptide. Picrotoxin (100 μM) and picrotoxinin (100 μM) did not alter the rate of phosphoincorporation relative to vehicle (DMSO; P = 0.97), however, a specific antagonist of CK1ε (SP600125) was effective (P < 0.001).

Period shortening does not require GPCR or action potential-dependent signaling.

Advances in PER2 accumulation could occur through a variety of candidate pathways requiring G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) activation (Golombek and Rosenstein 2010). We found, however, that inhibition of Gs-adenylyl cyclase (MDL-12,330A, 2.5 μM), Gq-phospholipase C (U73122, 10 μM), or Gi/o/t signaling (pertussis toxin, 5 nM) all failed to block picrotoxinin-induced period reduction (P > 0.05; Fig. 3A). In retina of the marine gastropod Bulla gouldiana, shortened circadian periods and phase-advanced rhythms in compound action potential frequency result from blockade of nonspecific chloride conductances (Khalsa et al. 1990; Michel et al. 1992). Given that picrotoxin antagonizes ligand-gated chloride conductances, we hypothesized that its effect on PER2 was due to chloride channel/transporter blockade. However, inhibition of Ca2+-activated and voltage-gated chloride channels by 9-AC or NPPB did not alter period length (P > 0.05; Fig. 1F). Since picrotoxin ubiquitously shortens period of single neurons independent of Cys-loop receptors and GPCR activation, we tested whether its actions required intercellular signaling. Application of the voltage-gated sodium channel blocker TTX to SCN explants did not block the effect of picrotoxin (TTX+vehicle, 24.1 ± 0.2 h; TTX+picrotoxin, 19.8 ± 0.4 h; n = 4 and 3, respectively; P < 0.0001; Fig. 3B). Together, these data indicate that picrotoxin acts cell-autonomously to accelerate the intracellular molecular mechanisms regulating PER2 accumulation.

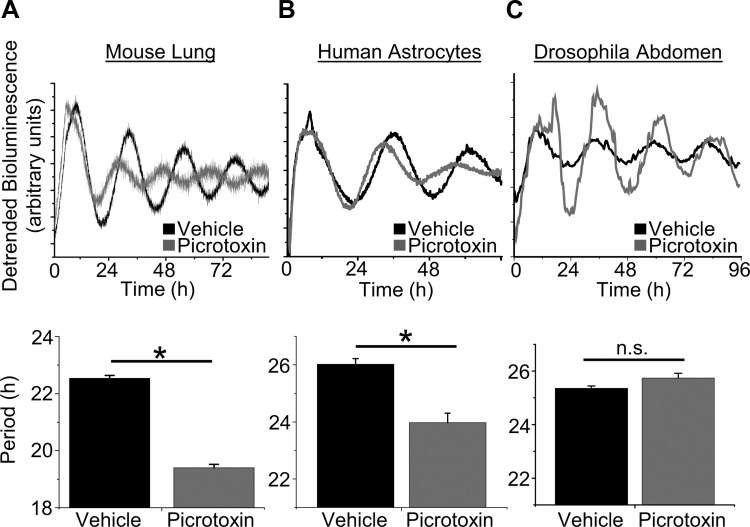

Picrotoxin shortens periodicity in human and murine nonneuronal cells.

Clock genes are rhythmically expressed in multiple mammalian tissues including brain, liver, and lung (Takahashi et al. 2008). To test the generality of the effect of picrotoxin on mammalian tissue, we applied picrotoxin to primary human astrocytes expressing a lentivirus-delivered luciferase reporter of Per2 transcription. We found that picrotoxin shortened the period of Per2::dLuc rhythmicity in astrocytes (vehicle, 26.0 ± 0.2 h; 100 μM picrotoxin, 23.9 ± 0.3 h; P < 0.001; Fig. 4, C and D). Additionally, we applied picrotoxin to mouse lung explants and found it shortened period (vehicle, 22.5 ± 0.1 h; 500 μM picrotoxin, 19.4 ± 0.1 h; n = 4 and 3, respectively; P < 0.001; Fig. 4, A and B). These results are also consistent with the period shortening found in the drug screen by Isojima et al. (2009) on NIH/3T3 and U2OS cells. Given that tritiated picrotoxinin, [3H]α-dihydropicrotoxinin, does not specifically bind lung membrane fractions (Ticku et al. 1978), our results suggest that the target of picrotoxin may be intracellular.

Fig. 4.

Picrotoxin speeds the circadian clock in murine and human nonneural tissue but not Drosophila. A, top: PER2::LUC rhythms from representative lung explants cultured with vehicle or picrotoxin (500 μM); bottom: quantification of the period of lung under each condition (means ± SE, n = 3–4 per treatment; *P < 0.001). B, top: PER2::dLuc rhythms from representative primary human astrocytes cultured with vehicle or picrotoxin (100 μM); bottom: quantification of the period of human astrocyte cultures under each condition (n = 5 per treatment; *P < 0.001). C, top: Timeless::luciferase (Tim::Luc) rhythms from representative Drosophila abdomens cultured in vehicle or picrotoxin (500 μM); bottom: Drosophila Tim::Luc abdominal rhythms were unaffected by picrotoxin (n = 26 per treatment; P > 0.05). n.s., Not significant.

Picrotoxin does not alter periodicity in Drosophila.

Since picrotoxin speeds rhythmicity in nonneural tissue and across human, mouse, and rat, we tested whether it could also modulate period across phyla. We developed a high-throughput assay to monitor Timeless gene expression from D. melanogaster. Interestingly, rhythms in Drosophila abdominal clock gene expression are not altered by 500 μM picrotoxin (vehicle, 23.4 ± 0.1 h; picrotoxin, 23.7 ± 0.2 h; n = 26 per treatment; P > 0.05; Fig. 4, E and F). Similar results were also obtained from individual wings (vehicle, 25.4 ± 0.8 h; 100 μM picrotoxin, 25.4 ± 0.5 h; n = 20–25 per treatment, P > 0.05; vehicle, 23.3 ± 0.3 h; 500 μM picrotoxin, 22.8 ± 0.3 h; n = 23 per treatment, P > 0.05). Given that picrotoxin-sensitive Cys-loop receptors are conserved in Drosophila (Ortells and Lunt 1995), these results further indicate that picrotoxin is acting via a distinct and novel mechanism in mammalian cells.

DISCUSSION

Our results are consistent with observations that cell-autonomous regulation of PER2 protein accumulation can accelerate circadian rhythms (Blau 2008). For example, in humans, mice, hamsters, and flies, it has been argued that mutations in homologs of Per2 or CK1 speed circadian periodicity by altering PER phosphorylation, stability, nuclear localization, and transcriptional activation, although the specifics remain unclear (Takahashi et al. 2008). Notably, however, our results suggest that the target of picrotoxin is found in mammal but not flies, thereby ruling out all conserved Cys-loop receptors and known regulators of mammalian PER stability. We conclude that picrotoxin alters PER2 dynamics through a novel, mammalian-specific mechanism.

The effects of picrotoxin on circadian timing in vivo remain untested. Because picrotoxin can induce epileptiform activity and seizures (Sierra-Paredes and Sierra-Marcuno 1996a,b), most behavioral experiments have been limited to acute injections (Berretta et al. 2004; Ikemoto et al. 1997; Kodsi and Swerdlow 1995; Shin and Ikemoto 2010). For example, acute picrotoxin administration into the supramammillary nucleus transiently increased locomotor activity for several minutes (Shin and Ikemoto 2010). Although the effects of chronic picrotoxin exposure remain unknown, we predict that in vivo manipulation of the picrotoxin target would speed circadian rhythms in physiology and behavior. Unfortunately, until its circadian target is identified, the toxic side-effects of picrotoxin will prevent its use for in vivo tests on circadian timing.

Although picrotoxin is commonly used to inhibit Cys-loop receptors including GABAA receptors, our results show that it could impact experimental results through two additional routes. First, thousands of genes and proteins oscillate in abundance or activity over circadian time, as do features of LTP (Herzog 2007). Therefore, a change in the amplitude of experimental readouts after chronic or acute (Rangarajan et al. 1994) picrotoxin treatment may be due to measuring the readouts at different phases of their respective oscillations. Second, molecular mechanisms that modulate circadian rhythmicity have been shown to affect synaptic plasticity independently. For example, chronic inhibition of CK2 leads to significant period-lengthening of the circadian clock via hypophosphorylation of Per2 (Tsuchiya et al. 2009), whereas acute CK2 inhibition alters LTP by antagonizing activity-dependent NR2B phosphorylation and endocytosis (Sanz-Clemente et al. 2010). Given that picrotoxin surprisingly impacts protein dynamics over circadian time independent of known Cys-loop receptor targets, unknown targets may have important and novel short-term actions as well.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants MH-63104 (to E. D. Herzog) and F30-NS-070376 (to G. M. Freeman, Jr.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.M.F., H.R.U., and E.D.H. conception and design of research; G.M.F. and M.N. performed experiments; G.M.F. and M.N. analyzed data; G.M.F. and M.N. interpreted results of experiments; G.M.F. prepared figures; G.M.F. drafted manuscript; G.M.F., H.R.U., and E.D.H. edited and revised manuscript; G.M.F., M.N., H.R.U., and E.D.H. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Marpegan and T. Simon for expert technical assistance; P. H. Taghert, W. Li, and L. Duvall for assistance with Drosophila; P. D. Lukasiewicz, S. Mennerick, D. Covey, J.-H. Steinbach, C. Lingle, and members of the Herzog laboratory for helpful discussion.

REFERENCES

- Abe M, Herzog ED, Yamazaki S, Straume M, Tei H, Sakaki Y, Menaker M, Block GD. Circadian rhythms in isolated brain regions. J Neurosci 22: 350–356, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton SJ, Huettner JE, Straume M, Herzog ED. GABA and Gi/o differentially control circadian rhythms and synchrony in clock neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 19188–19193, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta S, Lange N, Bhattacharyya S, Sebro R, Garces J, Benes FM. Long-term effects of amygdala GABA receptor blockade on specific subpopulations of hippocampal interneurons. Hippocampus 14: 876–894, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blau J. PERspective on PER phosphorylation. Genes Dev 22: 1737–1740, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon GH, Im WB, Carter DB, McKinley DD. Enhancement by GABA of the association rate of picrotoxin and tert-butylbicyclophosphorothionate to the rat cloned alpha 1 beta 2 gamma 2 GABAA receptor subtype. Br J Pharmacol 115: 539–545, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkkila BE, Weiss DS, Wotring VE. Picrotoxin-mediated antagonism of alpha3beta4 and alpha7 acetylcholine receptors. Neuroreport 15: 1969–1973, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebultowicz JM, Stanewsky R, Hall JC, Hege DM. Transplanted Drosophila excretory tubules maintain circadian clock cycling out of phase with the host. Curr Biol 10: 107–110, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek DA, Rosenstein RE. Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol Rev 90: 1063–1102, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog ED. Neurons and networks in daily rhythms. Nat Rev Neurosci 8: 790–802, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog ED, Takahashi JS, Block GD. Clock controls circadian period in isolated suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Nat Neurosci 1: 708–713, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T, Lewis WG, Liu AC, Lee JW, Schultz PG, Kay SA. A chemical biology approach reveals period shortening of the mammalian circadian clock by specific inhibition of GSK-3β. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 20746–20751, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Kohl RR, McBride WJ. GABA(A) receptor blockade in the anterior ventral tegmental area increases extracellular levels of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats. J Neurochem 69: 137–143, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isojima Y, Nakajima M, Ukai H, Fujishima H, Yamada RG, Masumoto KH, Kiuchi R, Ishida M, Ukai-Tadenuma M, Minami Y, Kito R, Nakao K, Kishimoto W, Yoo SH, Shimomura K, Takao T, Takano A, Kojima T, Nagai K, Sakaki Y, Takahashi JS, Ueda HR. CKIepsilon/delta-dependent phosphorylation is a temperature-insensitive, period-determining process in the mammalian circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 15744–15749, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SB, Ralph MR, Block GD. Chloride conductance contributes to period determination of a neuronal circadian pacemaker. Brain Res 520: 166–169, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodsi MH, Swerdlow NR. Prepulse inhibition in the rat is regulated by ventral and caudodorsal striato-pallidal circuitry. Behav Neurosci 109: 912–928, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leak RK, Moore RY. Topographic organization of suprachiasmatic nucleus projection neurons. J Comp Neurol 433: 312–334, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu AC, Tran HG, Zhang EE, Priest AA, Welsh DK, Kay SA. Redundant function of REV-ERBalpha and beta and non-essential role for Bmal1 cycling in transcriptional regulation of intracellular circadian rhythms. PLoS Genet 4: e1000023, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel S, Khalsa SB, Block GD. Phase shifting of the circadian rhythm in the eye of Bulla by inhibition of chloride conductance. Neurosci Lett 146: 219–222, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moga MM, Moore RY. Organization of neural inputs to the suprachiasmatic nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 389: 508–534, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC, Leak RK. Suprachiasmatic nucleus organization. Cell Tissue Res 309: 89–98, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortells MO, Lunt GG. Evolutionary history of the ligand-gated ion-channel superfamily of receptors. Trends Neurosci 18: 121–127, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S, Antoch MP, Miller BH, Su AI, Schook AB, Straume M, Schultz PG, Kay SA, Takahashi JS, Hogenesch JB. Coordinated transcription of key pathways in the mouse by the circadian clock. Cell 109: 307–320, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plautz JD, Straume M, Stanewsky R, Jamison CF, Brandes C, Dowse HB, Hall JC, Kay SA. Quantitative analysis of Drosophila period gene transcription in living animals. J Biol Rhythms 12: 204–217, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter SM, DeMarse TB. A new approach to neural cell culture for long-term studies. J Neurosci Methods 110: 17–24, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan R, Heller HC, Miller JD. Chloride channel block phase advances the single-unit activity rhythm in the SCN. Brain Res Bull 34: 69–72, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Clemente A, Matta JA, Isaac JT, Roche KW. Casein kinase 2 regulates the NR2 subunit composition of synaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron 67: 984–996, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin R, Ikemoto S. Administration of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin into rat supramammillary nucleus induces c-Fos in reward-related brain structures. Supramammillary picrotoxin and c-Fos expression. BMC Neurosci 11: 101, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara K, Honma S, Katsuno Y, Abe H, Honma KI. Two distinct oscillators in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 92: 7396–7400, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Paredes G, Sierra-Marcuno G. Effects of NMDA antagonists on seizure thresholds induced by intrahippocampal microdialysis of picrotoxin in freely moving rats. Neurosci Lett 218: 62–66, 1996a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra-Paredes G, Sierra-Marcuno G. Microperfusion of picrotoxin in the hippocampus of chronic freely moving rats through microdialysis probes: a new method of induce partial and secondary generalized seizures. J Neurosci Methods 67: 113–120, 1996b [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolove PG, Bushell WN. The chi square periodogram: its utility for analysis of circadian rhythms. J Theor Biol 72: 131–160, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires RF, Casida JE, Richardson M, Saederup E. [35S]t-butylbicyclophosphorothionate binds with high affinity to brain-specific sites coupled to gamma-aminobutyric acid-A and ion recognition sites. Mol Pharmacol 23: 326–336, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanewsky R, Jamison CF, Plautz JD, Kay SA, Hall JC. Multiple circadian-regulated elements contribute to cycling period gene expression in Drosophila. EMBO J 16: 5006–5018, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet 9: 764–775, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticku MK, Ban M, Olsen RW. Binding of [3H]alpha-dihydropicrotoxinin, a gamma-aminobutyric acid synaptic antagonist, to rat brain membranes. Mol Pharmacol 14: 391–402, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiya Y, Akashi M, Matsuda M, Goto K, Miyata Y, Node K, Nishida E. Involvement of the protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of mammalian circadian rhythms. Sci Signal 2: ra26, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Pol AN, Tsujimoto KL. Neurotransmitters of the hypothalamic suprachiasmatic nucleus: immunocytochemical analysis of 25 neuronal antigens. Neuroscience 15: 1049–1086, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb AB, Angelo N, Huettner JE, Herzog ED. Intrinsic, nondeterministic circadian rhythm generation in identified mammalian neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 16493–16498, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D, Pedersen SE, White MM. Interaction of d-tubocurarine analogs with the 5HT3 receptor. Neuropharmacology 37: 251–257, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SH, Yamazaki S, Lowrey PL, Shimomura K, Ko CH, Buhr ED, Siepka SM, Hong HK, Oh WJ, Yoo OJ, Menaker M, Takahashi JS. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 5339–5346, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang EE, Liu AC, Hirota T, Miraglia LJ, Welch G, Pongsawakul PY, Liu X, Atwood A, Huss JW, 3rd, Janes J, Su AI, Hogenesch JB, Kay SA. A genome-wide RNAi screen for modifiers of the circadian clock in human cells. Cell 139: 199–210, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]