Abstract

Introducing structural diversity into the nucleoside scaffold for use as potential chemotherapeutics has long been considered an important approach to drug design. In that regard, we have designed and synthesized a number of innovative 2′-deoxy expanded nucleosides where a heteroaromatic thiophene spacer ring has been inserted in between the imidazole and pyrimidine ring systems of the natural purine scaffold. The synthetic efforts towards realizing the expanded 2′-deoxy-guanosine and -adenosine tricyclic analogues as well as the preliminary biological results are presented herein.

Keywords: Tricyclic, Nucleosides, Expanded purine, Nucleobase, Guanosine, Adenosine

1. Introduction

Interest in the design and synthesis of modified nucleosides has increased steadily over the past few decades.1–3 The impetus for such development is a result of several factors.4 For example, modified nucleoside analogues have been found to be particularly important in chemotherapeutic applications for the treatment of disease. In that regard, they have been used to treat diseases by inhibiting essential enzymes involved with the replication pathways of many viruses, parasites, bacteria and cancers. Brivudine and Idoxuridine, both possessing heterobase modifications, are used to treat varicella-zoster virus and herpes simplex virus respectively.5 Additionally, FDA approved drugs such as Gemcitabine, Fludarabine and Cytarabine have been found useful in treating cancers,6 whereas, Zidovudine (AZT), a reverse transcriptase inhibitor, has provided the foundation for the treatment of HIV.7

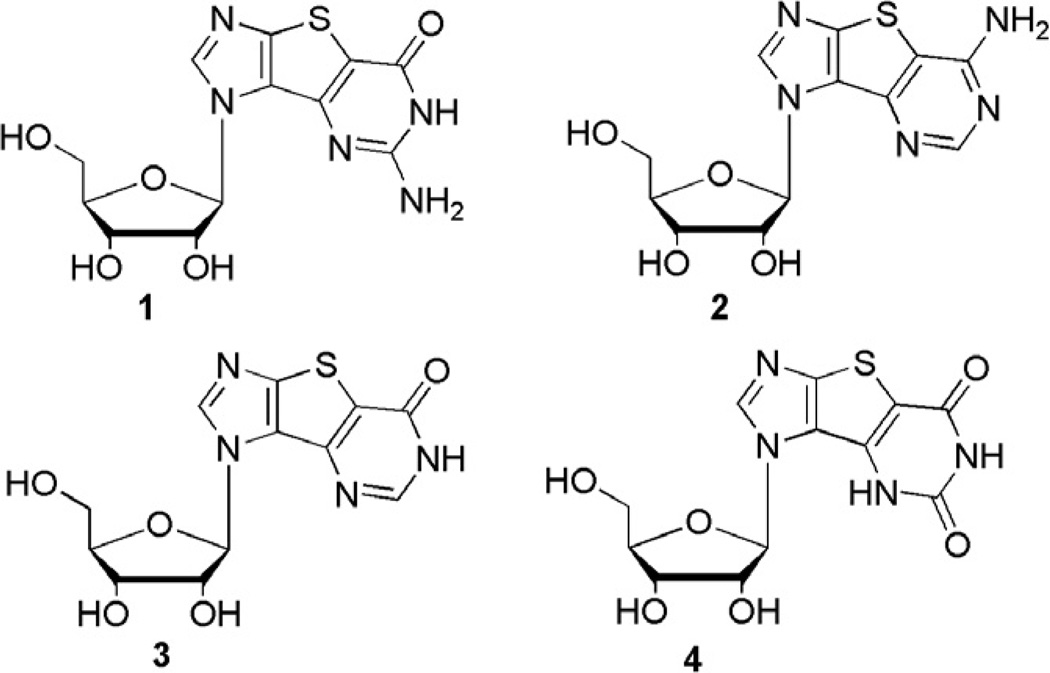

As a consequence, we, as many others in the field, have focused on the design and synthesis of innovative and structurally unique types of nucleosides with the aim of synthesizing potential chemotherapeutics. 8–17 One such series involves modified purine nucleosides that possess heteroaromatic spacer rings, for example a thiophene, between the imidazole and the pyrimidine ring of the purine scaffold (Fig. 1).10,18

Figure 1.

Thieno-expanded nucleosides.

This structural diversity provides several advantages over previously studied systems such as Leonard’s lin-benzoadenosine analogues.4,19–23 Some of the expanded nucleosides reported by our group (shown in Fig. 1), have exhibited promising chemotherapeutic activity suggesting the increased aromatic surface area increases biological activity.24–26 Notably, the triphosphates of the nucleosides in Figure 1 have been recognized and incorporated by RNA polymerases from T7 and SP6. Moreover, the triphosphate of the guanosine nucleoside 1 (Fig. 1) has been shown to be a good inhibitor of HCV NS5B polymerase.27 In the HCV replicon whole cell assay, the ribofuranose thieno-expanded guanosine and adenosine analogues (1 and 2 respectively in Fig. 1) possessed moderate inhibitory activity with EC50 values of 74 and 87 µM, respectively. 27 Another finding was the observation that the nucleoside and nucleobase transporters in Trypanosoma brucei recognized both the ribose analogues in their nucleoside form as well as their corresponding nucleobases.24 Additionally, the nucleobases of the modified ribonucleosides exhibited interesting cytostatic activity against three cancer cell lines.26

Given the promising activity of the parent ribose analogues, the analogous 2′-deoxy series (5 and 6, Fig. 2) were therefore of interest for investigating 2′-deoxy metabolizing enzymes.

Figure 2.

Proposed 2′-deoxythieno-expanded nucleosides.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Chemistry

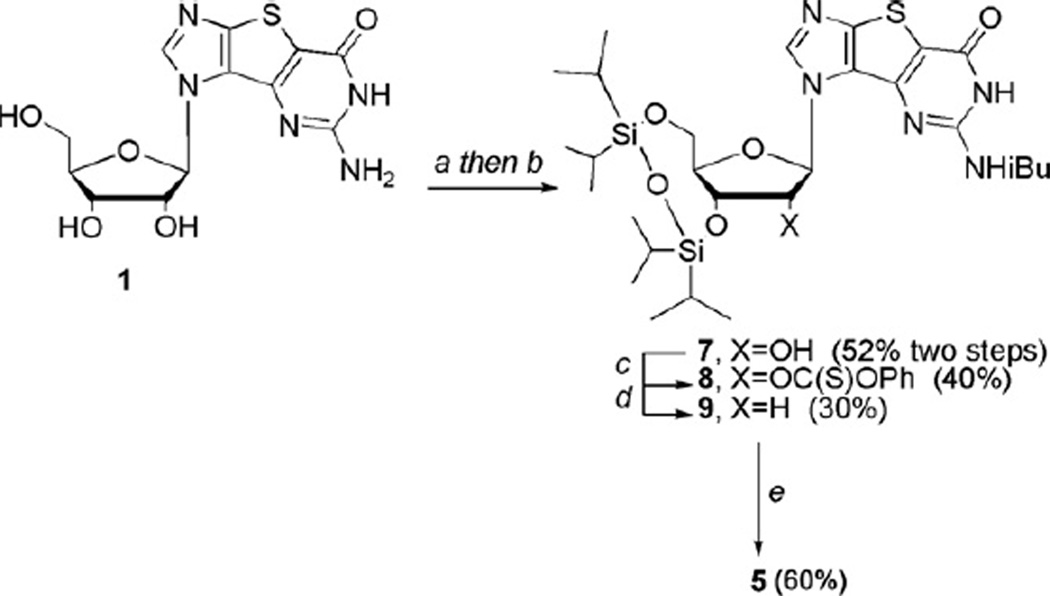

Two potential synthetic routes could be envisioned in order to realize the 2′-deoxynucleosides; one, a linear route stemming directly from a 2′-deoxy sugar, or two, treatment of the ribofuranose guanosine tricyclic nucleoside9,10,18,26 with the well-known Barton deoxygenation protocol28,29 to generate the 2′-deoxy target. The latter was initially chosen since a small amount of the ribose nucleosides were already in hand and could be utilized immediately. In preparation for the Barton deoxygenation, the exocyclic amine group on the guanosine nucleoside 110 was protected with isobutyryl chloride followed by selective bis-protection of the 3′- and 5′-hydroxyl groups with 1,3-dichloro-1,1,3,3-tetraisopropyl- 1,3-disiloxane to give 7 in 52% yield for the two steps (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2′-deoxyguanosine analogue 5. Reagents and conditions: (a) TMSCl, pyridine then isobutyryl chloride, 24 h; (b) 1,3-dichloro-1,1,3,3-tetraisopropyldisiloxane, pyridine, rt, 24 h; (c) phenyl chlorothionoformate, DMAP, rt, 24 h; (d) AIBN, Bu3SnH, toluene, reflux, 6 h; (e) (i) 1 M TBAF, THF, rt, 4 h; (ii) methanolic ammonia, rt.

Using Barton deoxygenation procedures,28,29 the free 2′-hydroxyl group was then treated with phenyl chlorothionoformate to give the thiocarbonate 8. Treatment with AIBN and tributyltin hydride then afforded intermediate 9, albeit in only 30% yield. Although a minute amount of starting material was recovered, there were a number of other side products that could not be isolated or characterized due to very similar Rf values. Finally, deprotection of the silyl groups followed by removal of the isobutyryl group gave the target compound 5 in 60% yield from 9 (Scheme 1), with an overall yield starting from the ribose nucleoside 1 of 3.8%. While on the surface this appeared reasonable, when considering that the overall yield starting from diiodoimidazole and commercially available protected ribose was only 0.5%, it rendered this approach less attractive, so attention turned to the alternative route—starting from a 2′-deoxy sugar.

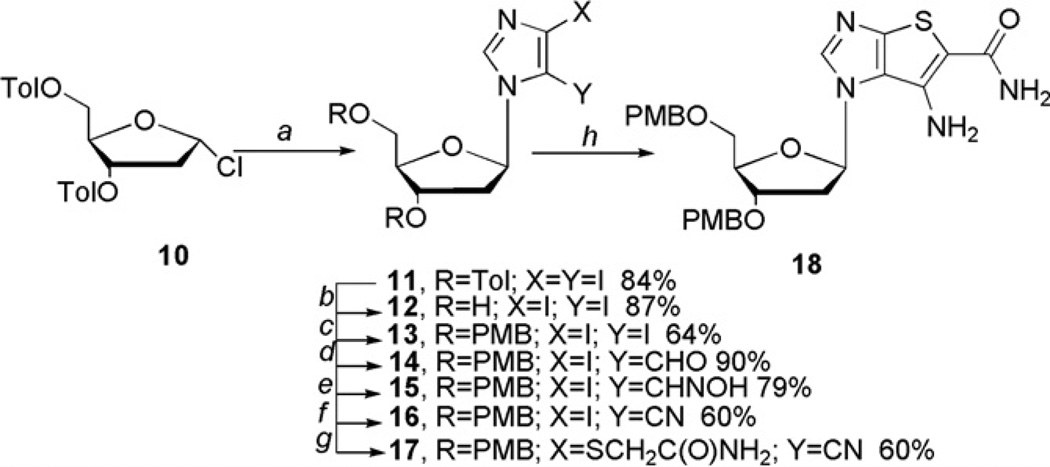

Synthesis began with the coupling of 4,5-diiodoimidazole to Hoffer’s well-known toluoyl-protected chlorosugar30,31 to provide intermediate 11 in 84% yield (Scheme 2). Sekine et al. were successful in synthesizing and isolating 11 not only in good yield, but also as the beta isomer.30 Due to the harsh conditions present in subsequent steps however, the toluoyl groups needed to be replaced with a more robust protecting group. Although several attempts were made to replace the toluoyl group before coupling, they all resulted in poor yields, so the decision was made to replace them after coupling. In that regard, the para-methoxybenzyl (PMB) group appeared to be a viable option as there exists a plethora of deprotection procedures in the literature.32–37 More importantly, a number of those procedures utilized neutral conditions thus would be less likely to result in glycosidic bond cleavage, something that had been a problem in the past using other deblocking protocols. Consequently, the nucleoside was protected with PMB using standard procedures to provide 13 in 64% yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 2′-deoxy intermediate 18. Reagents and conditions: (a) MeCN, NaH, 30 min, diiodoimidazole, 24 h, rt ; (b) MeOH, NaOMe; (c) THF, NaH, 3 h, TBAI, PMBCl, 18 h, rt; (d) (i) EtMgBr, THF, 15 min; (ii) anhydrous DMF; (e) (i) NaHCO3, hydroxylamine hydrochloride, H2O; (ii) carbaldehyde, EtOH, rt, 18 h; (f) CDI, THF, reflux, 18 h; (g) NH2C(O)CH2SH, K2CO3, DMF, 60 °C; (h) NaOEt, EtOH.

Addition of the aldehyde was carried out as before10,12 with the exception that the crude product was taken on directly to the next reaction without purification due to the observed instability of the aldehyde on silica gel columns. The protocol for the synthesis of the aldoxime 15 was also modified due to the decomposition of the 2′-deoxynucleoside under the previously used conditions.10,18 Sodium bicarbonate was used instead of pyridine as the base, and the order of addition for the reagents was changed, as well as the reaction conditions, all which served to result in greater yields. Dehydration was accomplished with 1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI)38 instead of acetic anhydride10,18 or trichloroacetonitrile12 to give 16. CDI appeared superior to the previously used reagents in terms of the yield of the isolated product as well as its purification. Ring closure to bicyclic intermediate 18 was then carried out in an analogous manner as was used for the ribose series.

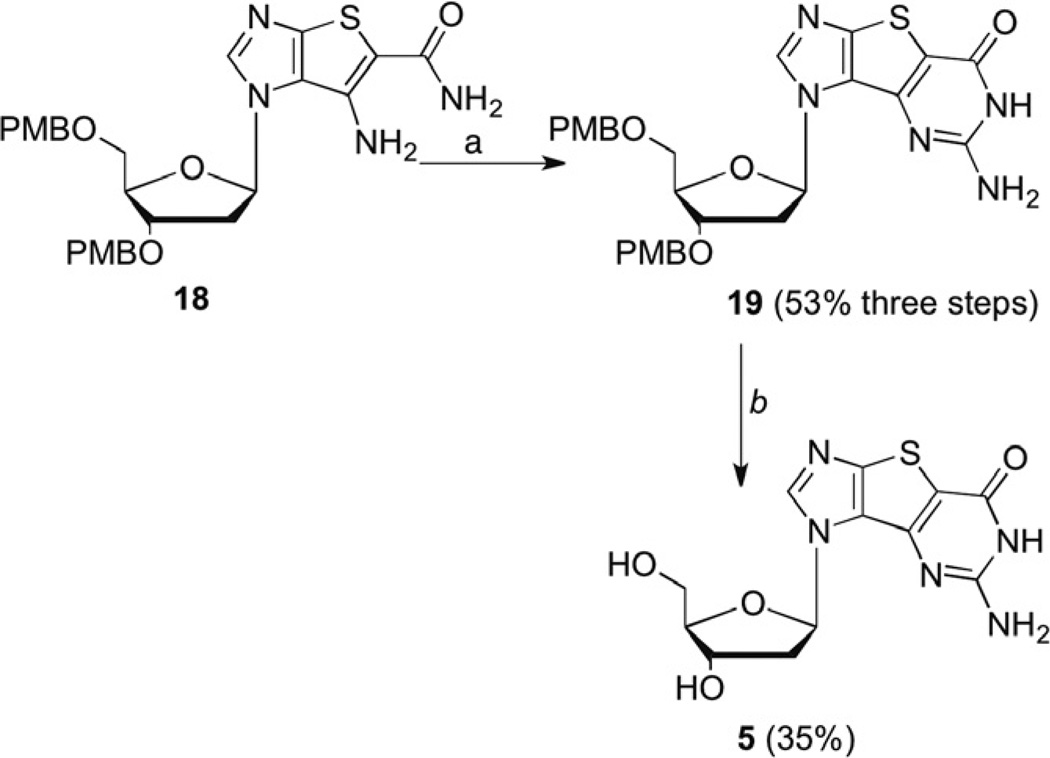

Formation of the tricyclic intermediate 19 (Scheme 3) was subsequently achieved in a 53% yield for three steps. The previous ring closure conditions using CS2 and NaOH in MeOH were observed to be incompatible with the 2′-deoxy nucleoside, as an inseparable mixture of products was obtained. As a result, the first step of the ring closure protocol was modified and pre-formed potassium ethylxanthic acid salt was used instead of CS2 and NaOH in MeOH. Surprisingly, in contrast to our reported synthesis of the ribose analogues, no xanthosine side-product was observed.10

Scheme 3.

Formation of tricyclic 2′-deoxyguanosine 5. Reagents and conditions: (a) (i) KSC(S)OEt, DMF, reflux, 4 h; (ii) H2O2, MeOH, 0 °C, 2 h; (iii) NH3, MeOH, 125 °C, 18 h; (b) BF3·OEt2, EtSH, CH2Cl2.

Deprotection of the PMB groups proved to be quite problematic despite the availability of numerous deprotection strategies that could be found in the literature.32–37 Several conditions were attempted, including the standard deprotection procedure utilizing ceric ammonium nitrate (CAN). Unfortunately CAN resulted in significant glycosidic bond cleavage. In most cases, either no product was observed or the product yields proved to be less than 10%. Ultimately the original Lewis acid mediated deblocking procedure was employed, which gave 5, albeit in only a 35% yield (Scheme 4). The overall yield for the linear route starting with the tolouyl sugar provided to be 2.2%, a significant increase over the yield starting from ribose.

Scheme 4.

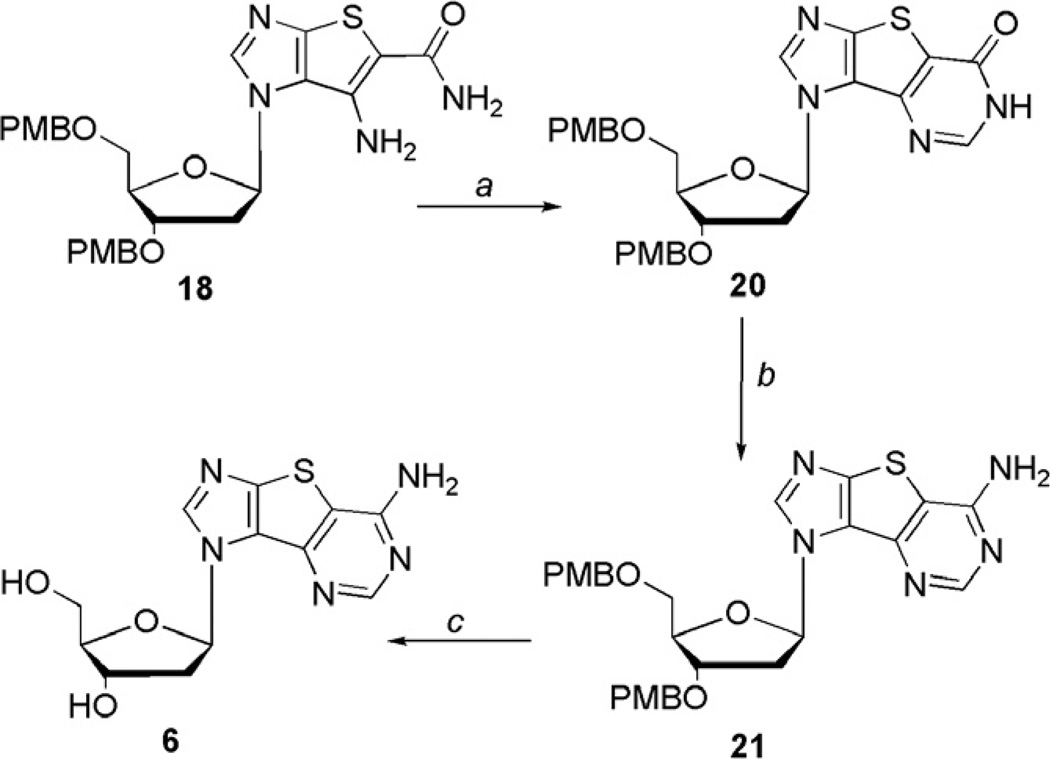

Synthesis of tricyclic 2′-deoxyadenosine 6. Reagents and conditions: (a) CH(OEt)3, 4 Å molecular sieves; (b) (i) TPSCl, DMAP, TEA, MeCN, 3 h; (ii) NH3, 18 h, rt; (c) BF3·OEt2, EtSH, CH2Cl2.

Analogous to the synthetic route to the guanosine analogue, the expanded adenosine nucleoside 6 could be approached from the same two routes, and since the synthesis of both 5 and 6 were being pursued concurrently, both routes were tried for comparison. As was the case with the guanosine analogue, the route involving the Barton deoxygenation was accompanied by low yields and difficulties with various purifications, thus the route using the 2′-deoxy sugar was attempted. Starting with the bicyclic intermediate 18, ring closure to the tricyclic base was accomplished with triethyl orthoformate and molecular sieves to give the inosine intermediate 20 (Scheme 4).

Initially, use of our previously published route of converting the carbonyl group of 20 to the thiocarbonyl followed by methylation and subsequent removal with ammonia18,26 to obtain the adenosine analogue was tried. However, reaction of the inosine intermediate with phosphorus pentasulfide did not afford any of the desired product, but instead, resulted in a complex mixture of unidentifiable compounds. Surmising that the phosphorus pentasulfide was reacting with the ether moiety of the PMB protecting group, akin to the results reportedly observed39 in the synthesis of Lawesson’s reagent from anisole, a new route was sought. Efforts to convert 20 to the chloro derivative using phosphorus oxychloride also proved futile as the starting material decomposed under these harsh conditions regardless of reaction time and/or temperature. Moreover, converting the carbonyl of 20 to the relatively labile triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl (TPS) group followed by removal with ammonium hydroxide,40 was disappointing. The yield of 21 was less than 20% although fortunately a significant amount of the inosine starting material 20 could be recovered. Speculation was that the water in the ammonium hydroxide was facile in replacing the labile TPS group, thus the use of ammonia instead of ammonium hydroxide provided 21 in 65% yield. Finally, use of the Lewis acid deprotection of 21 as before provided 6 in 30% yield.

Comparing the two approaches, just as was seen with the guanosine analogue, the overall yield for the route to the tricyclic adenosine starting with ribose and diiodoimidazole and using the Barton deoxygenation proved to be only 0.1%, while the route starting with the 2′-deoxy sugar was 2.1%. Thus, while it could be argued that using the ribose as a starting material would essentially produce both the 2′-deoxy and the ribose nucleosides, it was clear it was not a particularly efficient way to approach their synthesis.

2.2. Biological results

Once the tricyclic targets were in hand, they were evaluated for their potential inhibitory activity against a broad variety of viruses, and for their potential cytostatic activity. Moderate inhibition was observed for 5 and 6 against the proliferation of three cancer cell lines as summarized in Table 1. The compounds were somewhat more cytostatic against human embryonic lung fibroblasts (HEL). In all cases, 6 was ~2-fold more inhibitory to cell proliferation than 5. Both compounds 5 and 6 were evaluated against a wide variety of viruses (see Table 2 below), including herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), HSV-2, HSV TK, vaccina virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Sindbis virus, Punta Toro virus, Reovirus- 1, Coxsackie virus B4, parainfluenza-3 virus, influenza virus types A and B, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV- 1) and type 2 (HIV-2). Moderate activity was observed for both analogues against VZV (Table 2).

Table 1.

Anticancer activity of tricyclic targets

| Compound | IC50a(µM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1210 | CEM | HeLa | HEL | |

| 5 | 144 ± 15 | 166 ± 54 | 81 ± 10 | 22 |

| 6 | 53 ± 4 | 82 ± 39 | 57 ± 40 | 12 |

50% inhibitory concentration or compound concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50%.

Table 2.

Antiviral activity of targets 5 and 6 in cell culture

| Virus | EC50a (µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 6 | Ribavirin | |

| HEL cells | |||

| HCMV (AD-169 & Davis) | >100 | >4 | — |

| VZV (OKA & 07/1) | 71.3–100 | 8.9 | — |

| HSV-1 (KOS) | >100 | >20 | >250 |

| HSV-1 TK− | >100 | >20 | >250 |

| HSV-2 (G) | >100 | >20 | >250 |

| VV | >100 | >20 | >250 |

| VSV | >100 | >20 | 146 |

| HeLa cells | |||

| VSV | 100 | >100 | 29 |

| Coxsackie virus B4 | >100 | >100 | 146 |

| RSV | >100 | >100 | 10 |

| CEM cells | |||

| HIV-1(IIIB) HIV-2(ROD) | ≥250 | >10 | >50 |

| Vero cells | |||

| Parainfluenza-3 virus | >100 | >100 | 85 |

| Reovirus-1 | >100 | 100 | >250 |

| Sindbis virus | >100 | 100 | >250 |

| Coxsackie virus B4 | >100 | >100 | >250 |

| Punta Toro virus | >100 | 100 | 126 |

| MDCK cells | |||

| Influenza virus (AH3N2) | >0.16 | >4 | 5.1–9.0 |

| Influenza virus A (H1N1) | >0.16 | >4 | 2.3–3.4 |

| Influenza virus B | >0.16 | >4 | 4.5–9 |

| Cell line MCCb (µM) | |||

| HEL | >100 | ≥20 | >250 |

| HeLa | 100 | >100 | >250 |

| Vero | 100 | >100 | >250 |

| MDCK | 0.8 | 20 | 20 |

50% Effective concentration, or compound concentration required to inhibit virus-induced cytopathicity by 50%.

Minimal cytotoxic concentration, or compound concentration required to cause a microscopically visible alteration of cell morphology.

3. Summary

Two different routes to the 2′-deoxy ribose tricyclic analogues were developed. Although the Barton deoxygenation has been used successfully with other nucleosides, it proved to be less efficient with our analogues. Speculation that the sulfur in the thiophene ring might be interfering in the radical reaction was one mechanistic possibility we considered, however it was not pursued further since the other route was reasonable and much higher yielding. Not surprisingly, some of the conditions for the 2′-deoxy’s had to be altered from our previously reported routes to realize the ribose analogues due to the inherent differences in stabilities for their glycosidic bonds, however these modifications may ultimately prove advantageous to the ribose route as we continue to pursue additional analogues. Finally, although only moderate cytostatic and antiVZV activity was noted for the two 2′-deoxyanalogues, efforts are currently underway to synthesize other expanded purine analogues, including the corresponding triphosphates, the results of which will be reported as they become available.

4. Experimental section

4.1. Synthetic methods

4.1.1. General

All chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification unless otherwise noted. Anhydrous DMF, MeOH, DMSO, and toluene were purchased or obtained using a solvent purification system. Melting points are uncorrected. All 1H and 13C NMR spectra were referenced to internal tetramethylsilane (TMS) at 0.0 ppm. The spin multiplicities are indicated by the symbols s (singlet), d (doublet), dd (doublet of doublets), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet), and br (broad). Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Column chromatography was performed using commercial silica gel and eluted with the indicated solvent system. Yields refer to chromatographically and spectroscopically (1H and 13C NMR) homogeneous materials.

4.1.1.1. 3′,5′-(1,1,3,3-Tetraisopropyldisiloxane-1,3-diyl) [N7-isobutyryl- 7-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3-yl- 7-one]-2,3,5-β-d-ribofuranose (7)

To a mixture of the triol 1 (0.735 g, 2.17 mmol) in dry pyridine (40 mL) was added TMSCl (3.5 mL, 27.8 mmol) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred at this temperature for 30 min and then for an additional 2 h at room temperature (rt). The mixture was then cooled to 0 °C and iBuCl (1.14 mL, 10.85 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was allowed to warm up to rt slowly and then stirred overnight. The reaction was quenched by the addition of H2O (5 mL) at 0 °C and the mixture was allowed to stir for 15 min followed by the addition of NH4OH (20 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for an additional 2 h. The volatiles were then removed under reduced pressure and the product purified by column chromatography eluting with CH2Cl2/MeOH (10:1) to give the intermediate as a white solid (303 mg). 1H NMR (acetone-d6):δ 0.93–0.94 (m, 1 H), 1.22–1.24 (m, 6H), 2.02–2.03 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.89–2.97 (m, 1 H), 4.05–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.30 (m, 1H), 4.94–4.99 (m, 1 H), 6.21 (d, 1 H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 9.99 (s, 1H), 12.24 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone- d6): δ 18.3, 18.4, 29.2, 29.4, 63.0, 53.2, 71.1, 71.2, 74.0, 82.4, 90.2, 90.3, 148.6, 149.5, 177.4, 180.4, 180.5, 180.6.

To a solution of the tricyclic intermediate (55 mg, 0.134 mmol) in pyridine (15 mL) was added TIPDSCl (0.052 mL, 0.134 mmol) dropwise. The reaction was then stirred at rt for 24 h. The solvent was evaporated and the residue was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (50 mL), washed with H2O, then saturated NaHCO3. The organic phases were dried and evaporated to dryness. The residue was purified by preparative chromatography (CH2Cl2/MeOH, 10:1) to give 7 as a yellow oil. Yield: 88 mg, 96% (52 % for two steps). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 0.93–0.94 (m, 1 H), 1.22–1.24 (m, 34H), 2.02–2.03 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.89–2.97 (m, 1 H), 4.05–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.30 (m, 1H), 4.94–4.99 (m, 1H), 6.21 (d, 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H), 9.99 (s, 1H), 12.24 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 18.3, 18.4, 29.2, 29.4, 63.0, 53.2, 71.1, 71.2, 74.0, 82.4, 90.2, 90.3, 116.6, 127.0, 148.9, 149.5, 151.4, 177.4, 180.4. HRMS (FAB): calcd for C28H46N5O7SSi2 (M+H)+ 652.2657, found 652.2659.

4.1.1.2. 3′,5′-(1,1,3,3-Tetraisopropyldisiloxane-1,3-diyl) [N7-isobutyryl- 7-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3-yl- 7-one]-2,3,5-β-d-ribofuranose- 2′-O-thiocarbonate henyl ester (8)

Compound 7 (91.3 mg, 0.143 mmol) was suspended in anhydrous CH3CN (10 mL) and was treated with DMAP (98 mg, 0.804 mmol) followed by phenylchlorothionoformate (0.036 mL, 0.268 mmol). The yellow solution was stirred for 24 h at rt. The solvent was removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography eluting with a gradient of 100% hexanes to 25% EtOAc in hexanes to give yellow crystals. Yield: 39 mg, 39%; mp 132–135 °C. 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 0.93–0.94 (m, 1 H), 1.22–1.24 (m, 34H), 2.02–2.03 (m, 1H), 2.58–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.89–2.97 (m, 1 H), 4.05–4.09 (m, 1H), 4.28–4.30 (m, 1H), 4.94–4.99 (m, 1H), 6.03 (d, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 6.72–7.32 (m, 5H), 8.30 (s, 1H), 10.34 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6) δ 18.3, 18.4, 29.2, 29.4, 63.0, 53.2, 71.1, 71.2, 74.0, 82.4, 90.3, 90.2, 148.4, 149.8, 177.5, 180.6, 180.5, 180.6, 205.4, 205.6 HRMS (FAB): calcd for C35H50N5O8S2Si2 [M+H]+ 788.2639, found 788.2641.

4.1.1.3. 3′,5′-(1,1,3,3-Tetraisopropyldisiloxane-1,3-diyl) [N7-isobutyryl- 7-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3-yl- 7-one]-2,3,5-β-d-deoxyribofuranose (9)

Under N2, 8 (300 mg, 0.38 mmol) was suspended in 10 mL anhydrous toluene and AIBN (28 mg, 0.17 mmol) added, followed by n-Bu3SnH (1.25 mL, 2.07 mmol). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6 h, and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum to give a yellow syrup. The crude syrup was purified via chromatography eluting with hexanes/EtOAc (2:1) to afford 9 as a colorless oil. Yield: 72 mg, 30%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 1.05–1.22 (m, 34H), 2.65–2.74 (m, 3H), 2.75–2.84 (m, 1 H), 3.92–3.94 (m, 1H), 4.05–4.12 (m, 1H), 4.66– 4.72 (m, 1H), 6.39–6.40 (m, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H), 12.06 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 12.6, 13.1, 13.2, 13.5, 16.9, 17.0, 17.3, 17.4, 17.5, 17.6, 19.1, 36.7, 41.2, 61.5, 69.1, 85.0, 85.6, 148.3, 157.3, 178.5. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C28H46N5O6SSi2 [M+H]+ 636.2707, found 636.2705.

4.1.1.4. 1-[(5-Aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3- yl-7-one)]-β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranose (5)

To a solution of 9 (72 mg, 0.113 mmol) in 5 ml of anhydrous THF was added TBAF (1 M in THF, 0.226 ml, 0.226 mmol). The mixture was stirred at rt until TLC analysis indicated the disappearance of the starting material. The THF was removed under vacuum and a solution of methanolic ammonia was added. This mixture was warmed to 40 °C and stirred for 18 h. The solvent was removed and the product 5 was purified by column chromatography eluting with EtOAc/acetone/ EtOH/H2O (4:1:1:1) to give a solid. Yield: 22 mg, 60%; mp 136– 138 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.64 (s, 1H), 3.75 (dd, 1H), 3.77 (dd, 1H), 3.87 (dd, 1H), 4.10–4.16 (m, 2H), 4.40 (s, 1H), 6.52 (t, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (s, 1H), 9.56 (s, 1H), 10.20 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 62.2, 70.7, 77.0, 88.6, 89.7, 108.9, 131.7, 150.6, 151.9, 160.6. HR-FAB m/z calcd for C12H14N5O4S [M+H]+ 324.0767, found 324.0765.

4.1.1.5. 1-[2’-Deoxy-3’,5’-di-O-(4-toluoyl)- β-d-ribofuranose-1- yl]-4,5-diiodoimidazole (11)30

To a solution of 4,5-diiodoimidazole (35.5 g, 111.2 mmol) in anhydrous CH3CN (200 mL) at 0 °C was added NaH (95%, 2.8 g, 111.2 mmol) portion wise. After the mixture was stirred for 30 min at rt, 10 (32 g, 101.1 mmol) was added portion wise at rt over a period of 1 h. After stirring at the same temperature for 18 h the reaction mixture was filtered over celite and washed with EtOAc (3 × 150 mL). The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was isolated by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane/EtOAc (3:1) to give 11 as a pale yellow syrup. Yield: 57 g, 84%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.42 (s, 3H), 2.54 (ddd, 6.40 Hz, 7.80 Hz, 14.20 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (ddd, 2.32 Hz, 5.96 Hz, 14.24 Hz, 1H), 4.60 (m, 1H), 4.64 (d, 3.64 Hz, 2H), 5.63 (dt, 2.76 Hz, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 6.06 (dd, 5.48 Hz, 7.76 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (d, 8.24 Hz, 2H), 7.27 (d, 8.24 Hz, 2H), 7.84 (d, 8.24 Hz, 2H), 7.85 (s, 1H), 7.93 (d, 8.24 Hz, 2H);13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 21.81, 21.87, 39.8, 63.8, 74.6, 79.8, 83.2, 89.5, 97.2, 126.3, 126.5, 129.4, 129.5, 129.6, 129.9, 138.9, 144.4, 144.7, 165.9, 166.2. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C24H23I2N2O5 (M+H)+ 672.9696, found 672.9693.

4.1.1.6. 1-(2’-Deoxy-β-d-ribofuranose-1-yl)-4,5-diiodoimidazole (12)30

To a solution of 11 (20.34 g, 30.3 mmol), in anhydrous MeOH (200 mL) was added NaOMe (3.38 g, 60.5 mmol) was added and the resulting solution was stirred for 4 h at rt. Then the solvent was evaporated and the product 12 was isolated as a white solid by flash chromatography on silica gel eluting with EtOAc/MeOH (9:1). Yield: 8.2 g, 87%; mp 58 °C–60 °C. 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz): δ 2.42 (m, 2H), 3.75 (m, 2H), 3.95 (m, 1H), 4.42 (m, 1H), 6.02 (t, 6.40 Hz, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H).13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz): δ 41.3, 61.3, 70.5, 88.0, 89.6, 94.5, 140.0. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C8H11I2N2O3 [M+H]+ 436.8859, found 436.8856.

4.1.1.7. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzlyoxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-(4,5-diiodoimidazol-3-yl)- β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (13)

To a suspension of NaH (95%, 0.82 g, 32.4 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) at 0 °C was added a solution of 12 (5.65 g, 12.96 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) dropwise over a period of 10 min. The resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 3 h, at which point tetrabutylammonium iodide (957 mg, 2.59 mmol) was added, followed by dropwise addition of p-methoxybenzyl chloride (5.2 mL, 38.9 mmol). The mixture was further stirred at rt for an additional 18 h. The reaction was filtered over celite and repeatedly washed with CH2Cl2. The organic layers were combined and reduced under vacuum to give a yellow syrup. Column chromatography eluting with hexane/EtOAc (3:2) gave 13 as thick oil. Yield: 5.6 g, 64%.1H NMR (acetone-d6, 400 MHz): δ 1.94 (m, 1H), 2.50–2.72 (m, 2H), 2.80 (s, 2H), 3.76 (dd, 3.2 Hz, 10.56 Hz, 2H), 3.77 (s, 6H), 4.45 (m, 1H), 4.47 (m, 1H), 5.94 (d, 6.40 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (m, 4H), 7.20 (m, 4H), 8.00 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (acetone-d6, 100 MHz) δ 39.7, 55.3, 69.5, 71.4, 73.3, 78.6, 84.4, 90.0, 113.9, 114.0, 129.3, 129.4, 129.5, 129.6, 139.7, 159.4. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C24H27I2N2O5 [M+H]+ 677.0015, found 677.0016.

4.1.1.8. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzlyoxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(5-iodo-4-carbaldehyde) imidazol-3-yl]- β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (14)

EtMgBr (1.6 mL, 3.0 M in Et2O, 3.84 mmol) was added to a stirred solution of the starting material (2.6 g, 3.84 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) under N2 at 0 °C. The mixture was then stirred at this temperature for 15 min. Anhydrous DMF (1.6 mL, 4.81 mmol) was added, and the mixture was further stirred for 20 min at 0 °C. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. Saturated NH4Cl solution (100 mL) was added and the mixture extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 mL). The organic extracts were combined, washed with brine (2 × 20 mL), and dried over MgSO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give 14 as a pale brown syrup which was used in the next step without further purification. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.15 (m, 1H), 2.68 (ddd, 3.20 Hz, 6.4 Hz, 13.72 Hz, 1H), 3.53 (m, 1H), 3.71 (dd, 3.2 Hz, 10.56 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (s, 6H), 4.20 (m, 2H), 4.39 (q, 11.44 Hz, 2H), 4.45 (q, 11.92 Hz, 2H), 6.58 (t, 5.04 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, 6.44 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, 6.44 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, 8.64 Hz, 4H), 8.61 (s, 1H), 9.66 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 40.4, 55.3, 68.7, 71.5, 73.2, 77.1, 84.6, 87.9, 114.0, 114.1, 129.4, 129.5, 129.6, 142.2, 159.4, 180.7. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C25H28IN2O6 [M+H]+ 579.0992, found 579.0995.

4.1.1.9. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzlyoxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(5-iodo-4-carbaldehydeoxime) imidazol-3-yl]- β-d-2’- deoxyribofuranose (15)

To NaHCO3 (2.9 g, 34.6 mmol) in H2O (15 mL) was carefully added hydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.97 g, 28.3 mmol), after which a solution of crude aldehyde 14 (2.22 g, 3.84 mmol) in THF/EtOH (1:3, 16 mL) was added dropwise. To the resulting turbid solution was added THF until the mixture turned homogeneous. The reaction mixture was then stirred at rt overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure; the residue was treated with H2O (10 mL) and the mixture extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 75 mL). The organic extracts were combined, washed with brine (10 mL), and dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford 15 as a pale yellow syrup which was used directly without further purification. Yield: 1.8 g, 79%.1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.15 (dt, 5.92 Hz, 13.72 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (ddd, 4.92 Hz, 5.96 Hz, 13.98 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (dd, 3.20 Hz, 10.52 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (dd, 2.76 Hz, 10.56 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 6H), 4.18 (m, 2H), 4.36 (q, 11.44 Hz, 2H), 4.44 (q, 11.92 Hz, 2H), 5.23 (s, 1H), 6.83 (d, 8.72 Hz, 2H), 6.87 (d, 8.68 Hz, 2H), 7.15 (d, 8.72 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, 8.34 Hz, 2H), 8.05 (s, 1H), 8.17 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 40.3, 55.3, 68.9, 71.5, 73.2, 77.6, 84.4, 88.0, 90.1, 113.9, 114.0, 125.0, 129.4, 129.5, 129.6, 139.4, 141.3, 142.8. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C25H29IN3O6 [M+H]+ 594.1101, found 594.1104.

4.1.1.10. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzlyoxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(5-iodo-4-carbonitrile)imidazol-3-yl]- β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (16)

To oxime 15 (2.40 g, 4.05 mmol) dissolved in dry THF (10 mL) was added 1, 1′-carbonyldiimidazole (821 mg, 5.06 mmol) and the reaction refluxed overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the syrup purified via flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane: EtOAc (3:2) to give the product 16 as a thick oil. Yield: 1.40 g, 60%. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.63 (m, 2H), 3.61 (dd, 3.24 Hz, 10.56 Hz, 2H), 3.62 (s, 6H), 4.31 (m, 2H), 4.46–4.49 (m, 4H), 6.15 (t, 6.60 Hz, 1H), 6.85 (m, 4H), 7.16 (d, 8.72 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (d, 8.88 Hz, 2H), 8.02 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 15.6, 65.9, 68.9, 69.4, 71.4, 72.2, 73.3, 78.5, 80.4, 81.9, 83.6, 92.1, 127.1, 128.1, 129.3, 129.5, 129.6, 163.9. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C25H27IN3O5 [M+H]+ 576.0995, found 576.0991.

4.1.1.11. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzlyoxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(5-carboxamide)[2,3-d]imidazol-3-yl]- β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (18)

To a solution of 16 (1.12 g, 1.95 mmol) dissolved in dry DMF (20 mL) was added potassium carbonate (352 mg, 2.53 mmol) and thioglycolamide (359 mg, 3.9 mmol) and heated at 60 °C for 19 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The reaction mixture was filtered over celite and the celite pad washed with MeOH (100 mL). The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a thick syrup 17 which was used directly in the next step without further purification or characterization.

To the syrup (1.05 g, 1.95 mmol) dissolved in dry EtOH (30 mL) was added NaOEt (95%, 279 mg, 3.9 mmol) and refluxed for 6 to 9 h. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was isolated as thick oil by flash chromatography on silica gel eluting with EtOAc to give 18 as a syrup. Yield: 650 mg, 62%.1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ 2.38 (m, 1H), 3.66 (m, 1H), 3.74 (m, 1H), 3.82 (s, 6H), 4.26 (m, 1H), 4.46–4.47 (m, 1H), 4.50 (s, 1H), 4.45–4.61 (m, 4H), 6.16 (s, 2H), 6.23 (t, 6.44 Hz, 1H), 6.60– 6.72 (s, 2H), 7.31–7.36 (m, 8H), 8.04 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 15.5, 39.9, 55.3, 68.3, 71.7, 73.3, 84.1, 86.2, 98.9, 113.8, 114.0, 114.1, 129.0, 129.4, 129.6, 129.8, 139.7, 145.6, 159.6, 168.5. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C27H30N4O6S [M]+ 538.1886, found 538.1889.

4.1.1.12. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzyloxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(5-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno-[2,3-d]pyrimidin-3- yl-7-one)]-β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (19)

Intermediate 18 (650 mg, 1.21 mmol) and ethylxanthic acid potassium salt (388 mg, 2.42 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (25 mL) and the mixture was refluxed for 4 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure to give a thick syrup. The syrup was then dissolved in a minimal amount of THF and cooled to 0 °C followed by the dropwise addition of H2O2 (8 mL). The mixture was then stirred at 0 °C for 2 h. The resulting mixture was then transferred to a steel bomb and cooled down to −78 °C and NH3 was bubbled in for 15 min. The bomb was sealed and heated at 120–130 °C for 18 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the product 19 isolated as a colorless oil. Yield: 360 mg, 53 %. 1H NMR (DMSOd6, 400 MHz): δ 2.38 (m, 2H), 3.50 (m, 1H), 3.60 (m, 1H), 3.70–3.71 (m, 6H), 4.31 (m, 1H), 4.38 (s, 2H), 4.45 (s, 2H), 6.44 (t, 6.44 Hz, 1H), 6.52 (s, 2H), 6.82–6.89 (m, 4H), 7.17–7.18 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.28 (m, 2H), 8.33 (s, 1H), 11.05 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ 39.9, 55.3, 68.3, 71.9, 73.6, 84.2, 87.0, 99.0, 113.6, 114.2, 114.5, 129.2, 129.6, 129.8, 130.0, 139.8, 146.2, 150.1, 159.4, 159.6. HRMS (ESI): calcd for C28H30N5O6S [M+H] 564.1917, found 564.1915.

4.1.1.13. 1-[(5-Aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin- 3-yl-7-one)]-β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (5)

Intermediate 19 (360 mg, 0.638 mmol) was dissolved at 0 °C in CH2Cl2, followed by the addition of BF3·OEt2 (0.27 mL, 1.275 mmol) and EtSH (0.96 mL, 1.275 mmol). The mixture was left to stir at rt overnight. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and H2O (10 mL) was added. The aqueous layer was then extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 10 mL). After which, the aqueous layers were combined and evaporated to give 5 as a colorless amorphous solid. Yield: 72 mg, 35%; mp 136–138 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.68 (s, 1H), 3.74 (dd, 2.4 Hz, 10.5 Hz. 1H), 3.76 (dd, 1.8 Hz, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.82 (dd, 1.9 Hz, 10.7 Hz, 1H), 4.08–4.16 (m, 2H), 4.37 (s, 1H), 6.32 (t, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.92 (s, 1H), 9.55 (s, 1H), 10.19 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 61.2, 70.2, 76.1, 86.7, 89.5, 108.7, 131.6, 150.4, 151.7, 160.4. HRMS (FAB) m/z calcd for C12H14N5O4S [M+H] 324.0767, found 324.0764.

4.1.1.14. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzyloxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-(imidazo[4′,5v:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3-yl-7-one)- β-d-2’-deoxyribofuranose (20)

A mixture of 18 (1.0 g, 1.86 mmol), triethylorthoformate (40 mL), and 4 Å molecular sieves (oven dried before use) was refluxed for 6 h. The reaction mixture was filtered and the excess solvent was evaporated and the residue purified by column chromatography eluting with ethyl acetate/hexane (2:1) to afford 20 as a hygroscopic white foam. Yield: 900 mg, 88%. 1H NMR (acetone-d6) δ 2.64 (dd, 4.1 Hz, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (dd, 5.0 Hz, 10.5 Hz, 1H), 3.70–3.71 (m, 6H), 4.30–4.31 (m, 2H), 4.36–4.38 (m, 2H), 4.46 (s, 2H), 4.52 (s, 2H), 6.58 (t, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 6.87–6.89 (m, 4H), 7.19–7.30 (m, 4H), 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.34 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (Acetone-d6) δ 54.3, 70.1, 70.4, 72.5, 79.3, 84.3, 86.9, 113.7, 121.7, 129.3, 129.5, 130.5, 142.5, 143.1, 146.4, 159.1, 159.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C28H29N4O6S [M+H] 549.1807, found 549.1804.

4.1.1.15. 3’-(p-Methoxybenzyloxy)-5’-(p-methoxybenzyloxymethyl)- 1-[(7-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-3- yl)]-β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranose (21)

To a mixture of 20 (900 mg, 1.64 mmol), DMAP (800 mg, 6.56 mmol), TEA (15 ml) in MeCN (50 ml) was added TPSCl (1.99 g, 6.56 mmol) portion wise over 10 min. The mixture was then left to stir overnight. After TLC analysis confirmed the disappearance of the starting material, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and THF (55 ml) added. The mixture was transferred to a bomb and cooled to −78 °C and ammonia was bubbled in for 10 min. The bomb was sealed and then left to stir overnight at rt. After which, the solvent was removed and the product was purified to give 21 as a yellow foam. Yield: 584 mg, 65%. 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ 2.87 (m, 1H), 3.73 (m, 1H), 3.75–3.76 (m, 6H), 3.96 (m, 1H), 4.29–4.30 (m, 1H), 4.56–4.60 (m, 4H), 4.62–4.89 (m, 2H), 6.00 (s, 2H), 6.34 (t, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.10–7.11 (m, 4H), 7.30–7.34 (m, 4H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 8.39 (m, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3) δ 14.3, 21.4, 29.8, 53.6, 60.5, 72.4, 73.6, 82.1, 88.9, 115.6, 127.9, 128.0, 128.6, 137.2, 137.5, 143.1, 144.4, 151.5, 156.4, 161.5, 171.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C28H30N5O5S [M+H] 548.1967, found 548.1969.

4.1.1.16. Synthesis of 1-[(7-aminoimidazo[4′,5′:4,5]thieno[3,2- d]pyrimidin-3-yl)]-β-d-2′-deoxyribofuranose (6)

Intermediate 21 (430 mg, 0.785 mmol) was dissolved at 0 °C in CH2Cl2, followed by the addition of BF3·OEt2 (1.25 mL, 5.903 mmol) and EtSH (6.31 mL, 8.38 mmol). The mixture was left to stir at rt for 48 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and H2O (10 mL) was added. The aqueous layer was then extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 10 mL). After which, the aqueous layers were combined and evaporated to give 6 as a colorless amorphous solid. Yield: 72 mg, 30%; mp 148–151.4 °C. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 3.52 (m, 1H), 3.62 (m, 1H), 3.93 (m, 1H), 4.11 (m, 1H), 4.58 (m, 1H), 5.16 (d, 1H), 5.41–5.43 (m, 2H), 5.85 (t, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (s, 2H), 8.09 (s, 1H), 8.31 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 21.3, 61.7, 70.6, 86.2, 112.1, 129.4, 135.7, 145.3, 155.1, 158.8, 162.5. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C12H14N5O3S [M+H] 308.0817, found 308.0815.

4.2. Antiviral assays

The antiviral assays, other than the anti-HIV assays, were based on inhibition of virus-induced cytopathicity in HEL [herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) (KOS), HSV-2 (G), vaccinia virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, cytomegalovirus (HCMV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV)], Vero (parainfluenza-3, reovirus-1, Sindbis and Coxsackie B4), HeLa (vesicular stomatitis virus, Coxsackie virus B4, and respiratory syncytial virus) or MDCK [influenza A (H1N1; H3N2) and influenza B] cell cultures. Confluent cell cultures (or nearly confluent for MDCK cells) in microtiter 96-well plates were inoculated with 100 CCID50 of virus (1 CCID50 being the virus dose to infect 50% of the cell cultures) in the presence of varying concentrations (fivefold compound dilutions) of the test compounds. Viral cytopathicity was recorded as soon as it reached completion in the control virus-infected cell cultures that were not treated with the test compounds. The minimal cytotoxic concentration (MCC) of the compounds was defined as the compound concentration that caused a microscopically visible alteration of cell morphology. The methodology of the anti-HIV assays was as follows: human CEM (~3 × 105 cells/cm3) cells were infected with 100 CCID50 of HIV(IIIB) or HIV-2(ROD)/ml and seeded in 200 µL wells of a microtiter plate containing appropriate dilutions of the test compounds. After 4 days of incubation at 37 °C, HIV-induced CEM giant cell formation was examined microscopically.

For the HCMV assays, confluent human embryonic lung (HEL) fibroblasts were grown in 96-well microtiter plates and infected with the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) strains, AD-169 and Davis at 100 PFU per well. After a 2-h incubation period, residual virus was removed and the infected cells were further incubated with medium containing different concentrations of the test compounds (in duplicate). After incubation for 7 days at 37 °C, virus-induced cytopathogenicity was monitored microscopically after ethanol fixation and staining with Giemsa. Antiviral activity was expressed as the EC50 or compound concentration required to reduce virusinduced cytopathogenicity by 50%. EC50’s were calculated from graphic plots of the percentage of cytopathogenicity as a function of concentration of the compounds.

The laboratory wild-type VZV strain Oka and the thymidine kinase- deficient VZV strain 07-1 were used for VZV infections. Confluent HEL cells grown in 96-well microtiter plates were inoculated with VZV at an input of 20 PFU per well. After a 2-h incubation period, residual virus was removed and varying concentrations of the test compounds were added (in duplicate). Antiviral activity was expressed as EC50, or compound concentration required to reduce viral plaque formation by 50%after 5 days as compared with untreated controls.

4.3. Cytostatic assays

Murine leukemia L1210, human T-lymphocyte CEM, human cervix carcinoma (HeLa) and human embryonic lung fibroblast (HEL) cells were suspended at 300,000–500,000 cells/mL of culture medium, and 100 µL of a cell suspension was added to 100 µL of an appropriate dilution of the test compounds in wells of 96-well microtiter plates. After incubation at 37 °C for two (L1210) or three (CEM, HeLa and HEL) days, the cell number was determined using a Coulter counter. The IC50 was defined as the compound concentration required to inhibit cell proliferation by 50%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM073645, KRS) and the K. U. Leuven (GOA 10/14). The authors are grateful for this support. The authors would also like to thank Phil Mortimer at Johns Hopkins University for his generous assistance with the HRMS, and Leentje Persoons, Frieda De Meyer, Lies Van den Heurck, Steven Carmans, Anita Camps, Leen Ingels and Lizette van Berckelaer for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.004.

References

- 1.Shimidzu T, Letsinger RL. J. Org. Chem. 1968;33:708. doi: 10.1021/jo01266a048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogilvie KK, Kroeker K. Can.J Chem. 1972;50:1211. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaucage SL, Caruthers MH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981;22:1859. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu H, Gao J, Maynard L, Saito YD, Kool ET. J. Am Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1102. doi: 10.1021/ja038384r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Clercq. E.Med. Res. Rev. 2008;28:929. doi: 10.1002/med.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, Kolitz J, Elias L, Shepherd L, Hines J, Threatte GA, Larson RA, Cheson BD, Schiffer CA. N. Engl. J Med. 2000;343:1750. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012143432402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Clercq. E Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2010;10:507. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Madhoun AS, Eriksson S, Wang ZX, Naimi E, Knaus EE, Wiebe LI. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2004;23:1865. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200040634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seley KL. In: Recent Advances in Nucleosides: Chemistry and Chemotherapy. Chu CK, editor. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2002. p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Wauchope OR, Seley-Radtke KL. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10791. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seley-Radtke KL, Zhang Z, Wauchope OR, Zimmermann SC, Ivanov A, Korba B. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. (Oxf) 2008:635. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wauchope OR, Tomney MJ, Pepper JL, Korba BE, Seley-Radtke KL. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4466. doi: 10.1021/ol101482h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicolaou KC, Ellery SP, Rivas F, Saye K, Rogers E, Workinger TJ, Schallenberger M, Tawatao R, Montero A, Hessell A, Romesberg F, Carson D, Burton D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011;19:5648. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Secrist JA, III, Barrio JR, Leonard NJ. Science. 1972;175:646. doi: 10.1126/science.175.4022.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lessor RA, Gibson KJ, Leonard NJ. Biochemistry. 1984;23:3868. doi: 10.1021/bi00312a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark JL, Hollecker L, Mason JC, Stuyver LJ, Tharnish PM, Lostia S, McBrayer TR, Schinazi RF, Watanabe KA, Otto MJ, Furman PA, Stec WJ, Patterson SE, Pankiewicz KW. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5504. doi: 10.1021/jm0502788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Clercq E, Field HJ. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006;147:1. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seley KL, Zhang L, Hagos A, Quirk SJ. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3365. doi: 10.1021/jo0255476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leonard NJ, Morrice AG, Sprecker MA. J. Org. Chem. 1975;40:356. doi: 10.1021/jo00891a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leonard NJ, Hiremath SP. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:1917. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maki AS, Kim T, Kool ET. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1102. doi: 10.1021/bi035340m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kool ET, Lu H, Kim SJ, Tan S, Wilson JN, Gao J, Liu H. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser. (Oxf) 2006;15 doi: 10.1093/nass/nrl008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kool ET, Lee AHF. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:141. doi: 10.1021/ar068200o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wallace LJM, Candlish D, Hagos A, Seley KL, de Koning HP. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2004;23:1441. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200027660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quirk S, Seley KL. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10854. doi: 10.1021/bi0503605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seley KL, Januszczyk P, Hagos A, Zhang L, Dransfield DT. J. Med. Chem. 2000;43:4877. doi: 10.1021/jm000326i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seley-Radtke KL, Zhang Z, Wauchope OR, Zimmermann SC, Ivanov A, Korba B. Nucleic Acids Symposium Series. 2008;52:635. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrn321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barton DHR. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:3991. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez RM, Hays DS, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:6949. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tawarada R, Seio K, Sekine MJ. Org. Chem. 2008;73:383. doi: 10.1021/jo701634t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolland V, Kotera M, Lhomme J. Synth. Commun. 1997;27:3505. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horita K, Yoshioka T, Tanaka T, Oikawa Y, Yonemitsu O. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:3021. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oikawa Y, Yoshioka T, Yonemitsu O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:885. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wright JA, Yu J, Spencer JB. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:4033. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu W, Su M, Gao X, Yang Z, Jin Z. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:4015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan L, Kahne D. Synlett. 1995;523 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oriyama T, Yatabe K, Kawada Y, Koga G. Synlett. 1995;45 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medwid JB, Paul R, Baker JS, Brockman JA, Du MT, Hallett WA, Hanifin JW, Hardy RA, Jr, Tarrant ME, et al. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:1230. doi: 10.1021/jm00166a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomsen I, Clausen K, Scheibye S, Lawesson SO. Organic Syntheses. 1984;62:158. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosley SL, Bakke BA, Sadler JM, Sunkara NK, Dorgan KM, Zhou ZS, Seley-Radtke KL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:7967. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.