Abstract

Flu viruses package essential functions into a small integral membrane protein known as M2. Such small membrane proteins represent major challenges for structural biology. A new study presented in this issue details the structure and functions of the influenza B M2 protein through the use of functional domain–specific solution NMR spectroscopy.

Influenza B is a substantial component of the annual mix of seasonal flu viruses. One of the essential proteins in this virus is BM2, a small membrane protein with a single transmembrane helix that, as a tetramer, forms a proton channel1. In this issue of Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, James Chou and co-workers describe the structure of BM2 (ref. 2), the first full-length proton channel to be structurally characterized. Membrane proteins and especially small α-helical membrane proteins continue to be a very challenging arena for structural biology, partly due to the large ratio of hydrophobic surface area to protein volume, which requires a good membrane-mimetic model for the native environment. This BM2 structure was solved by studying two overlapping constructs, one harboring the transmembrane or channel domain and the other the cytoplasmic or M1-binding domain. This report adds to the growing justification for structural studies of isolated functional domains, which can lead to important functional and biophysical insights for membrane proteins.

The influenza M2 proteins (the 97-residue AM2 and 109-residue BM2 from influenza A and B, respectively; Fig. 1) are the smallest ion channels that have ion selectivity as well as gating properties3,4. Their transmembrane domains (AM2 residues 25–46 and BM2 residues 6–26) form the proton-selective channels. Even minimalistic constructs of this domain have proton selectivity and acid activation properties, and the AM2, but not the BM2, channel can be blocked by the antiflu drugs amantadine and rimantadine1,2. Full native channel conductance properties appear to require somewhat more of the intact protein5, although this seems to be more of a structural rather than a sequence requirement. BM2 has very little sequence identity with AM2, except for the HxxxW signature sequence for a proton channel. Despite the low homology, the conductance rates of the two channels are similar.

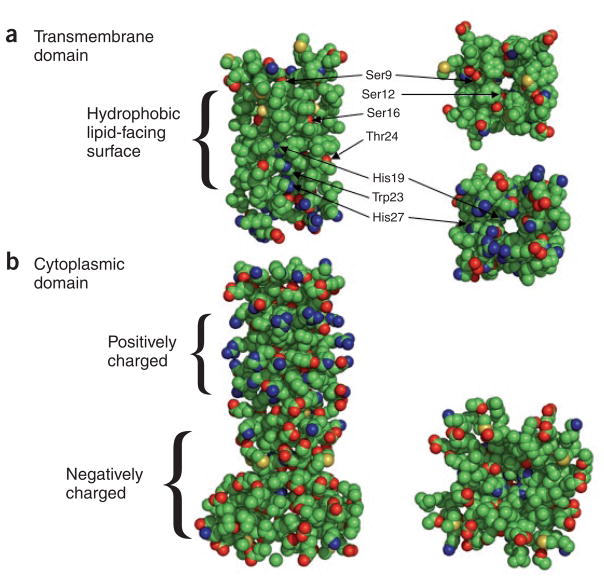

Figure 1.

Two structural and functional domains of BM2 (ref. 2) in a space-filling view of only the side chains, to emphasize the polar and titratable groups. (a) A side view (edge on to the membrane) of the transmembrane domain, which is primarily associated with proton conductance, is shown at left and end views at right. Shown here are residues 1–33. A highly hydrophobic surface is exposed to the fatty acyl chains of the lipid environment, although some of the Ser16 and Thr24 hydroxyls do not appear to line the pore of the channel. Although the side chain of His19 lines the pore, somewhat surprisingly the side chain nitrogens of Trp23 and His27 do not. (b) Side view of the M1 binding domain at left and end view at right. The structurally characterized sequence includes residues 43–103. There is a dramatic separation of charge due to a positively charged region between residues 32 and 71 that has 13 basic groups but only 4 glutamates per monomer (5 of these basic residues are in the sequence 32–42, which is not shown here). The C-terminal negatively charged region between 72 and 109 has 12 acidic groups but only 2 histidines and 1 lysine per monomer (5 of these charged residues are in the sequence 104–109, which is not shown here).

The two structures that Chou and co-workers describe in this issue2 are shown in Figure 1, which displays just the side chains, highlighting the oxygen and nitrogen atoms. The transmembrane domain is characterized by only a few hydrophilic residues, most of which line the aqueous pore. Both ends of the pore are hydrophilic, and nearly the full length of this construct (residues 1–33) is structurally characterized. The second construct (residues 26–109) also forms a tetrameric structure dominated by a four-helix bundle for residues 46–85 and a short additional helix for residues 92–101. The C-terminal region from residue 72 to 109 is dominated by glutamates and a couple of aspartates presenting a highly charged region that the authors show, via chemical shift perturbation, to bind M1 protein.

Although their channel activity has received much attention, other functions associated with these M2 proteins are also important. For AM2 the N-terminal 24 residues or ectodomain seems to be important for viral budding6. Interestingly, although chimeras of BM2 with the N-terminal half of the transmembrane domain of AM2 are blocked to a considerable degree by amantadine, if a portion of the AM2 ectodomain is included, the channel is ≥85% blockable by amantadine7. Residues 47–62 of AM2 form a membrane surface–bound amphipathic helix that may stabilize the tetrameric transmembrane domain by forming salt bridges from these amphipathic helices to adjacent monomers8. This amphipathic helix has numerous positive charges, similar to an analogous sequence (residues 27–41) in BM2 that is represented by terminal regions of the author’s two constructs. This highly charged region presumably forms significant interactions with the negatively charged lipids of the native membrane inner leaflet. In addition, the amphipathic helix of AM2 has a palmitoylation site, Cys50, that is not present in BM2 and is anticipated to strengthen the interactions with the membrane. Such lipid interactions may suggest that this helix is involved in membrane trafficking and localization9. Finally, the C-terminal or cytoplasmic domain (residues 63–97 of AM2 and residues 42–109 of BM2) binds to M1 protein, promoting the recruitment of viral proteins and RNA to the plasma membrane for efficient viral assembly10.

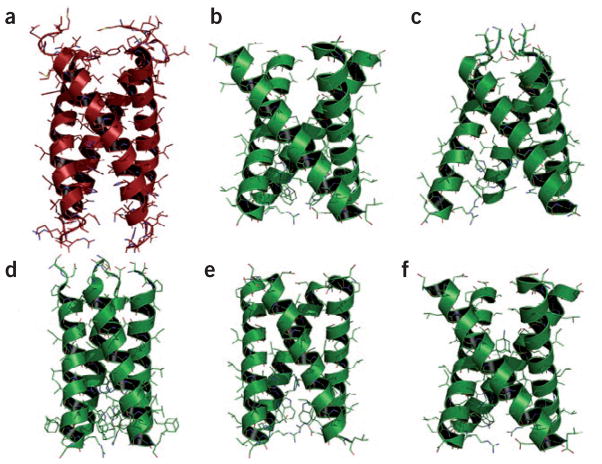

Figure 2 shows some of the AM2 transmembrane domain structures that have been deposited in the PDB, in comparison with the BM2 structure presented now. They all show a tetrameric left-handed helical bundle, and the helices have a significant tilt with respect to the bilayer normal. The structures of the top row were obtained in the absence of antiflu drugs, and those in the bottom row were obtained in the presence of amantadine or rimantadine. Several of the AM2 structures show helical kinks or bends near the Gly34 residue, a feature proposed to be important for channel activity11. Uniquely, the BM2 helical bundle is purported to be a coiled coil. This may be caused by the unique pattern of serine residues in BM2, SxxSxxxS (where the three serines are Ser9, Ser 12, Ser16), in which Ser16 is sequentially aligned with the AM2 Gly34. These small side chains permit close packing of helices. Alternatively, three of the four helices in this BM2 structure have a primary bend near Ser16 consistent with some observations in AM2.

Figure 2.

Structures of the M2 proton channel domain from influenza A and influenza B. The top three panels show structures obtained in the absence of the antiviral drugs; the bottom three panels show structures obtained in the presence of the drugs amantadine and rimantadine. (a) BM2 (residues 1–33): the structure presented in this issue of NSMB by Chou and co-workers2 using solution NMR of DHPC micelles (PDB 2KIX). (b)AM2 (residues 22–46) obtained by solid-state NMR–derived orientational and distance restraints in liquid crystalline DMPC lipid bilayers (PDB 1NYJ)13. (c) AM2 (residues 22–46) obtained by X-ray crystallography in the presence of octylglucoside (PDB 3BKD)14. (d) AM2 (residues 18–60) obtained by solution NMR in DHPC micelles in the presence of rimantadine (but not bound in the pore) (PDB 2RLF)15. This portion of the structure (residues 23–46) was one of two helical segments characterized from this longer construct of the AM2 protein. (e) AM2 (residues 22–46) obtained from solid-state NMR in liquid crystalline lipid bilayers in the presence of amantadine (PDB 2H95)16. (f) AM2 (residues 22–46) obtained by torsional restraints from solid state NMR in lipid bilayers (PDB 2KAD)17.

Although there is a basic similarity between these structures, there are significant deviations even among the AM2 structures of the same construct with and without the antiviral drugs. There are many differences in the details of how these structures were determined and of the environments used to mimic the membrane environment. The solid-state NMR structures have few interhelical distances, and most of the side chain conformations have not been characterized, but the backbone structures as well as the tilt and rotational angles of the helices were determined with high resolution. The solution AM2 NMR structure is actually that of a longer construct, and therefore a potentially more native-like sample; however, the solution NMR and X-ray structures use a detergent environment to model the membrane, whereas the solid-state NMR samples use lipid bilayers and, for two of these bilayer preparations, the data were collected from a liquid crystalline phase. Even lipid composition is known to inactivate membrane proteins and to alter membrane protein structure12, never mind the substitution of lipids for detergents.

So how important is the structure of BM2 solved by Chou and colleagues? This paper documents functional assays for both channel conductance and M1 protein binding. Furthermore, this is the only BM2 structure and the only structure of a full-length proton channel presently available. Until the day when we can solve these structures in the native cellular (or viral) environment, there will be risk of structural imperfections. M2 proteins are not alone among membrane protein structural controversies. Here, there may be a weakness in the structure at the bilayer interface (residues 27–41), but the structure of the TM region is largely consistent with the majority of the AM2 structures. Furthermore, the structure of the M1 binding domain is unique. This continues to be a daunting structural problem for many reasons, but primary among them is the fact that the interactions between helices in the transmembrane domain are weak and prone to distortion and dynamics. Understanding the stability of these oligomeric protein structures is of great biophysical and functional importance for this class of proteins, which accounts for more than 50% of all drug targets. Chou and co-workers have described here an important structure that advances our knowledge substantially. Although a detailed mechanistic explanation of ion conductance is not immediately apparent, neither should it be expected. Membrane proteins have multiple native conformational states, ligand bound, ligand free, activated, inactivated, closed, open, and so on. An initial structure such as this BM2 structure is a crucial start toward understanding the conformational space over which this membrane protein carries out multiple functions.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank H.-X. Zhou for helpful discussions. Research in the Cross lab on membrane proteins is supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (R01 AI-023007, R01 AI-073891 and P01 AI-074805), and the spectroscopy is conducted at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory supported by Cooperative Agreement 0654118 though the Division of Materials Research at the National Science Foundation and the State of Florida.

References

- 1.Mould JA, et al. Dev Cell. 2003;5:175–184. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Pielak RM, McClintock MA, Chou JJ. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1267–1271. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pinto LH, Lamb RA. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5:629–632. doi: 10.1039/b517734k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busath DD. Advan Planar Lipid Bilayers & Liposomes. 2009;10:161–201. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tobler K, Kelly ML, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. J Virol. 1999;73:9695–9701. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.9695-9701.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park EK, Castrucci MR, Portner A, Kawaoka Y. J Virol. 1998;72:2449–2455. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2449-2455.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohigashi Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18775–18779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910584106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tian C, Gao PF, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Cross TA. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2597–2605. doi: 10.1110/ps.03168503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma C, et al. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15921–15931. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710302200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen BJ, Leser GP, Jackson D, Lamb RA. J Virol. 2008;82:10059–10070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01184-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yi M, Cross TA, Zhou HX. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13311–13316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906553106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bogdanov M, Heacock PN, Dowhan W. EMBO J. 2002;21:2107–2116. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.9.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishimura K, Kim S, Zhang L, Cross TA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13170–13177. doi: 10.1021/bi0262799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stouffer AL, et al. Nature. 2008;451:596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature06528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schnell JR, Chou JJ. Nature. 2008;451:591–595. doi: 10.1038/nature06531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, et al. Biophys J. 2007;92:4335–4343. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cady SD, Mishanina TV, Hong M. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1127–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]