Abstract

The proteome of extremely thermophilic microorganisms affords a glimpse into the dynamics of microbial ecology of high temperature environments. The secretome, or extracellular proteome of these microorganisms no doubt harbors technologically important enzymes and other thermostable biomolecules that to date have been characterized only to a limited extent. In the first of a two part study on selected thermophiles, defining the secretome requires a sample preparation method that has no negative impact on all downstream experiments. Following efficient secretome purification, GeLC-MS2 analysis and prediction servers suggest probable protein secretion to complement experimental data. In an effort to define the extracellular proteome of the extreme thermophilic bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, several techniques were considered regarding sample processing to achieve the most in-depth analysis of secreted proteins. Order of operation experiments all including the C18 bead technique demonstrated that two levels of sample purification were necessary to effectively de-salt the sample and provide sufficient protein identifications. Five sample preparation combinations yielded 71 proteins and the majority described as enzymatic and putative uncharacterized proteins anticipating consolidated bioprocessing applications. Nineteen proteins were predicted by Phobius, SignalP, SecretomeP, or TatP for extracellular secretion and 11 contain transmembrane domain stretches suggested by Phobius and TMHMM. The sample preparation technique demonstrating the most effective outcome for C. saccharolyticus secreted proteins in this study involves acetone precipitation followed by the C18 bead method in which 2.4% (63 proteins) of the predicted proteome was indentified including proteins suggested to have secretion and transmembrane moieties.

Keywords: Secretome, Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus, GeLC-MS2, Thermophile, Sample Preparation

Introduction

Extremophiles, bacterial microorganisms that thrive in extreme environmental conditions such as temperature, pressure, and pH extremes, offer unique resources for biocatalysis. Due to their habitats, extremophiles render robust enzymatic potential for processing materials under a variety of conditions [1, 2]. Hypotheses suggest and recent investigations evidence a variety of features and functions, including extracellular carbohydrate degradation [3–5] and antimicrobial potential [6, 7] of organisms with optimal growth temperature above 50°C. One such example of enormous benefit, the thermostable Taq polymerase isolated from the extreme thermophile Thermus aquaticus, is widely used for DNA amplification in PCR experiments [8]. Furthermore, the significance and likely functions derived from the microbial secretome of thermophiles are grossly underestimated and command the positive identification of the secreted proteins. The secretome encompasses the proteins released by an organism into the surroundings as well as those associated with the outer cell wall [9]. This translocation can be instigated by different events such as communication between cells, interaction with various substrates, and environment stresses [10, 11]. Exploring the extracellular proteome is essential in understanding the microbial ecology of natural and bioprocessing environments.

Attributed to genome sequencing, considerable exploration of the genome, and growth on a variety of substrates, the extreme thermophile (optimal growth temperature > 70°C) Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus offers a preview of extracellular thermophilic activity. C. saccharolyticus, originally isolated from a thermal spring in New Zealand, is a rod shaped, gram-positive bacterium that grows optimally at 70°C [12, 13], more details pertaining to this organism are highlighted in Part II of this investigation. Defining this secretome and further examining thermophilic species afford a glimpse into microbial ecology. Transcriptional data offers inventory of probable translated gene products; however, mass spectrometry (MS) is capable of providing evidence of protein translation. Prior to liquid chromatography (LC) MS interrogations, a robust sample preparation scheme must be established for sample cleanup due to interferences such as nutritional growth media and environmental contaminates present as the microbes grow and are handled. This method will provide proper identification of the secreted material and offer opportunity for further studies. The proteome, especially the extracellular proteome, of thermophilic microorganisms, has not been largely studied, thus, the absence of effective sample processing methods. Devoid of careful and well-defined methods, successful proteomic analysis becomes dubious as this initial sample handling propagates throughout the experimental workflow. Several factors must be considered such as compatibility with downstream LC-MS, sample handling, efficiency, and number of confident positive protein identifications, among others. Development of proteomic methods and strategies for analysis of the extracellular proteome will likely traverse other thermophiles and microorganisms grown in similar conditions in the quest to engineer the most efficient and effective thermostable biocatalysts applicable for industrial and pharmaceutical objectives.

Here, in Part I, the extracellular protein fraction of C. saccharolyticus was purified by several different methods prior to one-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (1D SDS-PAGE). Acetone precipitation, trichloroacetic acid (TCA) precipitation, and phenol extraction were first used as a cleanup step. Additional experiments employed other techniques such as drop dialysis, extraction with stationary phase beads, and filtration by molecular weight cut off (MWCO) filters. Order of operation or pairing of two methods for increased sample purification was also investigated to provide sufficient protein purification. To evaluate the sample preparation techniques, the GeLC-MS2 method [14], 1D SDS-PAGE followed by nano-flow LC coupled to electrospray ionization hybrid linear ion trap Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (ESI-LTQ-FT-ICR) MS2, afforded protein identification and label-free relative quantification of the C. saccharolyticus secretome. Part II probes the intracellular proteome of two thermophiles in different environmental conditions supplementing the secretome information from Part I.

Complementing experimental secretome investigations, prediction tools provide evaluation of the identified secreted proteins and transmembrane domains. Mechanisms by which proteins are secreted or exported to different locations in and outside the cell most frequently involve signal peptides [9]. These amino-terminal signal peptides are short chains of mostly hydrophobic amino acids that are cleavable after translocation. Bacterial cells can secrete proteins completely outside of the organism into the growth milieu through a provided pathway. Influenced by the type of bacteria, several pathways exist for protein secretion. SignalP 3.0 renders recognition of secretory (Sec) pathway signal peptides and cleavage sites of these peptides after secretion of the mature protein into the extracellular space [15, 16]. The Sec pathway is noted as one of the most frequent means of protein secretion in gram-positive bacteria; a preprotein (protein with signal peptide) is directed to the translocation machinery at the cell membrane by different routes, the addition of a molecular chaperone, through the signal recognition particle pathway attributable to hydrophobic signal peptide chains, or due to the association with the translocase, a multicomponent domain [9, 17]. The translocation of the preprotein is promoted by the multicomponent membrane complex and through the course of secretion the signal peptide is cleaved. Another secretion pathway occurring very similarly to the Sec pathway, the twin-arginine translocation (Tat), also involves a signal peptide; however, it contains two consecutive arginine residues and can be predicted with TatP 1.0 [18]. Non-classical protein secretion, secretion of a species with no evident signal peptide, has been identified in eukaryotes [19, 20] and in bacteria [21, 22], and the SecretomeP server aims to predict these species [23]. Overall, the prediction models may support the secretion of a particular protein; however, secretion is not necessarily guaranteed.

Further investigating predicted protein secretion, transmembrane domains should be absent from the secreted entity as this would most likely result in the protein anchored to the plasma membrane, and thus not entirely released into the extracellular space. The transmembrane hidden Markove model (TMHMM) tool predicts transmembrane helices and anticipates protein topology [24]. Those proteins identified with a secreted mature protein engaged in a transmembrane domain will be considered false positives. Several groups describe a weakness in this approach as most signal peptide and transmembrane domain predictors often mistaken one feature for the other due to similar amino acid patterns [15, 25, 26]. Criteria of both predictors include pursuing the recognition of a positively charged and hydrophobic region among other measures [16, 24, 25]. A combined prediction server, Phobius, renders a prediction scheme in which the optimal feature, signal peptide or transmembrane domain, is selected [25, 26]. However, SignalP correctly predicts a greater percentage of signal peptides versus Phobius as well as generated less false positives on a data set deficient of transmembrane domain containing species [15].

Experimental

Thermophilic Bacterial Growth and Secretome Concentration

C. saccharolyticus DSM 8903 (ATCC 43494) was grown anaerobically on a modified DSMZ 640 media (DSMZ - Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany) containing yeast extract proteins and peptides ≤ 1 kDa and with glucose as the carbon source at 75°C, similar to that previously described [27]. Sixteen-hundred mL cultures were harvested at mid-exponential phase (cell density approximately 5 × 107 cells/mL). Samples were filtered thru a 0.22 μm Durapore PVDF hydrophilic membrane filter with 47 mm diameter (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to separate the culture media or secretome sample from the bacterial cells. The secretome fraction was concentrated by ultrafiltration and underwent dialysis in an effort to remove contaminates reducing the 1600 mL secretome sample to approximately 10 mL employing a Millipore stirred cell and polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes with a 10 kDa MWCO (Fisher Scientific).

Protein Purification Techniques

Total protein concentration was approximated by a modified Bradford Assay method, the Coomassie Plus Assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and 50 μg of the C. saccharolyticus secretome sample were aliquoted for purification method evaluation. The technique employed for acetone precipitation was described in a technical resource note by Pierce [28] and illustrated in Fig. 1a1. Briefly, four volumes of cold (−20°C) acetone (Fisher Scientific) were added to 50 μg protein sample. The solution was vortexed and then incubated at −20°C for 90–120 min. Centrifugation for 30 min at 11,000 rpm allowed for decanting of the supernatant before air drying the protein pellet for 30 min. TCA precipitation was completed according to Jiang et al. [29] and is shown in Fig. 1a2. TCA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to an aliquot to a final concentration of 7.5–10% and the solution was incubated for 2 hours at −20°C. This was centrifuged and supernatant removed as in the acetone precipitation method. An aliquot (100 μl) of 90% acetone (−20°C) was used to wash the pellet during a 15 min incubation at −20°C. Again the solution was centrifuged, the supernatant was discarded and the protein pellet allowed to dry according to the procedure described above. Outlined by Sauvé et al. and illustrated in Fig. 1a3, phenol extraction was completed by adding one volume of liquefied phenol (Sigma-Aldrich) to a secretome aliquot, the solution was vortexed 20 seconds and centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 5 min [30]. The upper aqueous phase was discarded and 2 volumes of diethyl ether (Fisher Scientific) were added to the organic layer. After vortexing for 20 seconds the solution was centrifuged as above and upper phase discarded. This wash step was repeated and the final lower phase dried under reduced pressure. The resulting dried protein pellets were stored at −20°C before reconstituting sample with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 (Fisher) for analysis by GeLC-MS2.

Fig. 1.

Initial sample preparation employing three frequently used protein purification techniques and corresponding 1D gel images. a Schematic of acetone precipitation, trichloroacetic acid precipitation, and phenol extraction methods as performed on 50 μg secretome samples. b and c 1D SDS-PAGE experiments of the purified protein samples visualizing with Bio-Safe Coomassie and Sypro Ruby, respectively. The numbered lanes correspond to the numbered purification methods. * represents the control sample in which the secretome aliquot was not processed prior to gel electrophoresis.

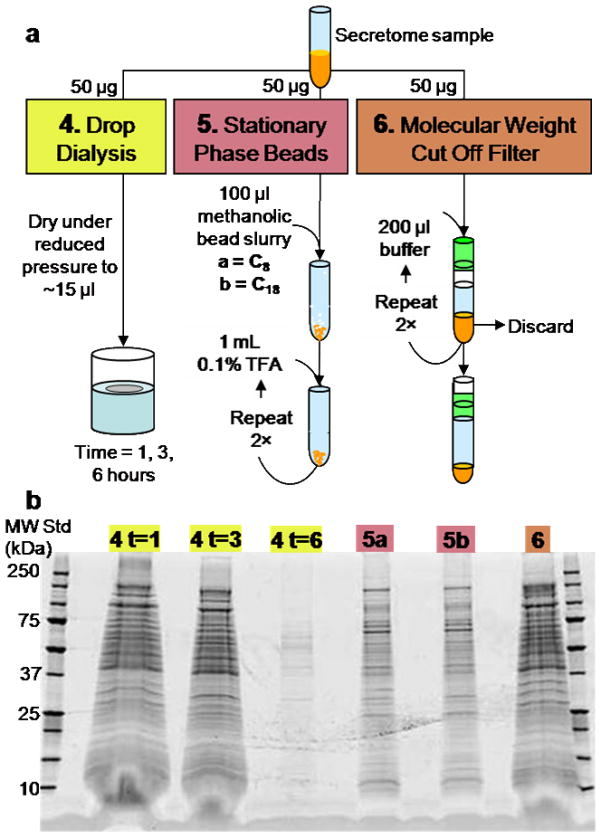

Drop dialysis 0.025 μm membrane filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) were moistened in a beaker of 100 mL HPLC-grade water (Burdick and Jackson, Muskegon, MI) for 10 min prior to aspiration of a 50 μg secretome aliquot dried down to approximately 15 μl on the middle of the filter. After incubation (1, 3, and 6 hours), the sample was collected, and dried under reduced pressure (see Fig. 2a4). For sample desalting using stationary phase beads, Fig. 2a5 outlines the method in which a methanolic slurry (100 μl) with 2.5–3 mg of 5 μm, 200A˚́ silica Magic C8 or C18AQ beads (Michrom BioReasources, Auburn, CA) was added to a 50 μg sample and vortexed for 5 min [31]. The mixture was centrifuged for 3 min at 14,000 rpm, 2 × 20 μl of methanol were added, centrifugation was repeated, and the supernatant discarded. The pellet was washed 3 times as follows: 1 mL of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich) was added, the solution vortexed for 1 min, and centrifuged 3 min as above. The supernatant was discarded. Lastly, for the MWCO filter technique (see Fig. 2a6), a secretome aliquot was passed through a 10 kDa Microcon centrifugal filter (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at 14000 rpm. A 200 μl aliquot of 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 (Fisher Scientific) was used to rinse the retentate, concentrated sample on membrane, and was subjected to centrifugation for 10 min at 14000 rpm, this rinsing was repeated twice. The ≥ 10 kDa retentate was collected. For samples purified by a combination of two cleanup steps, reagent aliquots required for the second step were based upon the initial sample volume. Each desalted sample was stored at −20°C prior to gel electrophoresis.

Fig. 2.

Investigation of additional sample desalting and protein purification techniques evaluated by gel electrophoresis. a Schematic of drop dialysis, stationary phase beads, and molecular weight cut off filter methods. b 1D SDS-PAGE experiment of secretome sample preparation methods. Sample loss occurred during drop dialysis over 6 hours due to the drop exceeding the membrane area. The numbered lanes correspond to the numbered purification methods.

GeLC-MS2

Gel electrophoresis was performed with 10–20% Tris-HCl Criterion Gels (BioRad, Hercules, CA) in 25 mM Tris-HCl, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), pH 8.3 (BioRad). The resultant processed secretome samples were reconstituted in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, loaded on the gel, and run at 200 V for 55 min. The gel was either stained with Bio-Safe Coomassie Blue G-250 (BioRad) for 60 min or fixed, stained with Sypro Ruby (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) overnight, and rinsed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Each gel lane was cut into 32 bands and 8 bands were grouped for a total of 4 fractions per gel lane. The bands were excised using a disposable gridcutter (2 mm × 7 mm lanes with 25 rows) from The Gelcompany (San Francisco, CA) and further cut with a razor blade into 1 mm × 2–3 mm pieces. An in-gel tryptic digestion was performed to the samples as adapted from Shevchenko et al. [32]. After dehydration with HPLC-grade acetonitrile (Burdick and Jackson), the samples were reduced with 10 mM dithiothreitol (BioRad) for 30 min at 56°C. This solution was removed and acetonitrile added to dehydrate the gel pieces. The acetonitrile was removed and 55 mM iodoacetamide (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to alkylate for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. After the removal of the alkylation solution, the gel pieces were dehydrated with acetonitrile. The acetonitrile was removed, and to digest the proteins, 1 ng/μl trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) solution was added and the samples incubated overnight at 37°C. The tryptic peptides were extracted by first incubating the gel pieces in 5% formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich):acetonitrile (1:2) at 37°C and withdrawing the supernatant. The sample was dehydrated with acetonitrile, supernatant removed, and hydrated with 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate:acetonitrile (2:1), these steps were repeated, all extractions pooled, and dried under reduced pressure. Samples were stored at −20° prior to nanoLC-MS2 interrogation.

NanoLC-ESI-LTQ-FT-ICR MS2 interrogations were performed in triplicate with an Eksigent (Dublin, CA) nanoLC-2D system in a continuous, vented column configuration as previously described [33], which was coupled to a hybrid LTQ-FT Ultra mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Inc. San Jose, CA) equipped with an actively shielded 7-Tesla superconducting magnet (Oxford Instruments, Concord, MA). A 50 μm thick stainless steel (SS) mesh screen and zero dead volume SS fitting from VICI Valco Instruments Co. Inc. (Houston, TX) were included in the set up between the transfer line and trap column. The trap, 100 μm i.d. IntegraFrit capillary, and analytical, 75 μm i.d. PicoTip capillary with 15 μm i.d. tip, columns (New Objective, Woburn, MA) were packed in-house with Magic C18AQ stationary phase, 3.2 cm and 15 cm, respectively. Mobile phase solvents were purchased from Burdick and Jackson. Mobile phase A was water/acetonitrile (98/2) and mobile phase B was water/acetonitrile (2/98) each including 0.1% formic acid. Samples (approximately 1 μg of protein) in 4 μl were injected into the 10 μl sample loop and then trapped and washed on the trap column by a 15 μl metered injection consisting of 2% B from Channel 1 at 3 μl/min.

At the conclusion of the metered injection the switching valve positioned Channel 2, the nano-flow pumps, inline with the trap and analytical column where the analytical separations transpired with a flow-rate of 300 nl/min. Initially, the gradient elution profile was held at 2% B for 3 min, and then 10% B for 2 min preceded a linear gradient to 25% B over 40 min. The following 15 min ramped up to 50% B, then 95% B over 3 min and held for 2 min. Initial gradient conditions were reinstated linearly over 5 min and held 5 min for equilibration. The pulse sequence for the mass spectrometer consisted of 7 events; a broadband survey scan 300–1600 m/z in the ICR cell followed by data-dependent scans of the first through sixth most abundant ions having ≥ 2+ charge state. The mass resolving power was set a 100,000fwhm at m/z 400, the AGC limit at 1 ×106 for the ICR cell and 1 × 104 in the ion trap, dynamic exclusion restricted the selection of a m/z to twice within 30 seconds prior to its exclusion for 180 seconds. External calibration was performed as recommended by the manufacturer.

Data Analysis

The bioinformatic platform included MASCOT Daemon which integrates the analysis of RAW files by first processing through MASCOT Distiller, fitting experimental isotopic distributions with ideal isotopic distributions, followed by MASCOT (version 2.2.04, Matrix Science Ltd., London, UK) for database searching [34]. The protein database used for analysis was a compilation of the C. saccharolyticus UniProt protein sequence database and its reverse; the C. saccharolyticus protein sequences were reversed by a perl script and inserted into the FASTA file. In addition, the Bos taurus trypsin protein sequence (1 protein), Homo sapiens keratin and keratin related protein sequences (177 proteins) (see Electronic Supplementary Material Table S1), and the Saccaromyces cerevisiae were incorporated into the database file for a total of 12,061 entries. The search parameters include cysteine carbamidomethylation as a fixed modification attributable to protein alkylation with iodoacetamide, and variable modifications of methionine oxidation and asparagine and glutamine deamidation. A maximum of 2 missed trypsin cleavages were allowed and tolerance measurements of ± 5 ppm for peptide mass and ± 0.6 Daltons for tandem MS measurements were set. One ProteoIQ (version 1.2.01, BIOINQUIRE, www.bioinquire.com) project was created merging data from each gel lane fraction and replicates, and offered comparative and statistical analysis. The proteins identified were arranged according to total protein score and proteins were determined to be statistically significant maintaining a < 1% false discovery rate (FDR) [35, 36]. Of those proteins having < 1% FDR and identified with a single peptide, manual MS2 validation was performed. Total spectral counts (SpC) and normalized SpC were extracted from the created ProteoIQ project.

The statistically significant proteins were exported from ProteoIQ into a FASTA file format for evaluation by SignalP 3.0, TMHMM 2.0, SecretomeP 2.0, TatP 1.0 (all available from CBS Prediction Server at http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/), and Phobius (available from Stockholm Bioinformatics Centre at http://phobius.sbc.su.se/). The FASTA formatted file was submitted to each prediction server for analysis and gram-positive bacteria was chosen for those searches requiring selection. For evaluation by SignalP 3.0 the following parameters were selected: both neural networks and hidden Markov models employed for signal peptide prediction, standard output, and each sequences was truncated to the first 70 residues. The file was submitted to the TatP 1.0 server with the default settings for regular expression examining protein sequences for the double arginine feature with a standard output and truncation of 100 residues.

Results and Discussion

Evaluation of Protein Purification Techniques and Order of Operation Investigations

A fundamental importance exists in the production of a robust and reproducible sample preparation. Once developed, this method may expand to the analysis of extracellular proteomes of other thermophilic microorganisms leading to the investigation of thermostable biocatalysts for a variety of applications (e.g., biomass degradation and therapeutics requiring antimicrobial species). Because of the nature of the thermophilic secretome, containing many small molecules and other nutritional elements in the growth media (see Electronic Supplementary Material Table S2), sample purification was essential for proteomic evaluation. Furthermore, sample fractioning of the extracellular proteome prior to LC-MS analysis yields decreasing sample complexity anticipating increase of confident protein identifications.

Techniques for sample cleanup rely on different principles of purification. Protein precipitation results from lowering the analyte solubility, by modifying the solvent composition via addition of reagent. With this alteration, proteins are precipitated out of solution removing impurities that remain in the sample medium. Acetone precipitation, first mentioned by Zakowski in 1931 for the precipitation of a soybean protein [37] is still widely applied today on samples ranging from human urinary [38] to fungal proteins [39]. A second protein precipitation technique, TCA precipitation, was first described in 1930 by Sahyn and Alsber to prepare rabbit liver glycogen [40]. Again, this method is still currently used for protein precipitation on a variety of samples such as plasma proteins [29] and secreted proteins from myeloid cells [41]. Exploiting the physical properties of proteins afford an alternative sample cleanup of complex biological samples in contrast to manipulating the solvent composition. Extraction with liquefied phenol purifies samples by means of hydrophobicity and was initially used for antigentic bacterial carbohydrate complexes in 1940 [42]. Phenol extraction allows for proteins to remain in solution when purified. Addition of liquefied phenol to a protein sample and rapid vortexing denature proteins and “flips” the hydrophobicity. The proteins are compelled to exchange solution from aqueous to organic.

Preliminary experiments purifying the C. saccharolyticus secretome by acetone precipitation, TCA precipitation, and phenol extraction (see Fig. 1a) proved to be inadequate as illustrated in Fig. 1b. This initial gel suggested that the Coomassie stain may not be sensitive enough for the secretome analysis and precipitation by TCA was not effective. Subsequent experiments employed acetone precipitation and phenol extraction to purify the sample, and Sypro Ruby stain was used for protein visualization. Fig. 1c illustrates increased band resolution with Sypro Ruby imparting greater sensitivity. Owing to the presence of vertical and horizontal diffusion, these experiments demonstrate that an interfering species or contaminant remains after an initial purification step.

It was necessary to incorporate a second level of secretome sample cleanup prior to GeLC-MS2 experiments. Three techniques (see Fig. 2a) resulted in a diverse range of sample desalting as demonstrated in Fig. 2b. Employing a commercially available membrane or membrane device (i.e., centrifugal filter), dialysis and filtration can be performed fractionating the sample due to its physical properties. The separation of molecules in a sample as a result of differing diffusion rates through a semipermeable membrane, dialysis removes small molecules and salts. The drop dialysis technique is formatted for small-volumes (≤100 μl), and is a simple and rapid method used for preparing samples for a variety of analysis (e.g., gel electrophoresis, isoelectric focusing, and electron microscopy) [43]. Drop dialysis reduced sample interferences over time; however, sample loss occurred between three and six hours due to the limited membrane area as the droplet increased in size over time. Filtering with a 10 kDa MWCO centrifugal filter, often used for sample desalting, did not effectively eliminate the horizontal band diffusion as demonstrated (see Fig. 2b lane 6). MWCO centrifugal filters fractionate species according to the radius of gyration [44, 45]. With a 10 kDa MWCO filter, small interfering species and salts approximately 10 kDa and less will flow thru the membrane, while in principle the retentate contains a desalted sample.

An alternative desalting technique not widely referenced, the addition of stationary phase beads directly into the sample of interest desalts as a function of protein/peptide interaction with the beads. As in reverse phase chromatography, the degree of hydrophobicity and the mobile phase induces partitioning of the analyte between the stationary and mobile phases. Prior to denaturing or linearizing a protein/peptide, the hydrophilic surface encapsulates hydrophobic moieties in aqueous solution. Integrating the methanolic slurry of C18 stationary phase beads with a secretome aliquot and rapidly vortexing provides some denaturing of proteins and the analyte-bead interaction to occur. The beads have affinity towards the analyte while the salts, small molecules, and impurities are washed from the sample. Although sample loss may occur due to extremely hydrophilic proteins or peptides as well as those not sufficiently denatured for interaction with the beads, the gel image (Fig. 2b lanes 5a and 5b) reveals that visually the bead technique is an improvement over more commonly used desalting techniques. Horizontal diffusion is almost completely eliminated employing the bead technique, particularly for lower molecular weight species which are potential smORFs (small opening reading frames) or SMURFs (small unknown opening reading frames) and are of significant interest in future studies of C. saccharolyticus and other thermophiles.[46] For subsequent sample processing, Magic C18AQ beads were utilized as it was anticipated that the longer chains would better retain smaller proteins.

In the case that one sample processing method, acetone precipitation or phenol extraction, improved purification in conjunction with using the Magic C18AQ beads, order of operation experiments were performed. Fig. 3 demonstrates that order does influence the 1D SDS-PAGE experiment visually. NanoLC-ESI-LTQ-FT-ICR MS2 experiments of the in-gel digestion [32] affords evaluation of the secreted proteins and demonstrates the most effective secretome sample preparation of the techniques investigated in this study (see following section for clarification). Visual differences between the C18 bead processed C. saccharolyticus secretome samples in Fig. 2b and 3 may be due to a variety of factors such as different C. saccharolyticus sample batches and inherently different volumes of secretome sample required to process approximately 50 μg of sample. Also alterations to imaging parameters for sufficient visualization of sample lanes may attribute to some of the visual variations. Nevertheless, the order of operation experiments were performed on equal aliquots of the same C. saccharolyticus secretome sample providing relative comparison of the protein purification techniques.

Fig. 3.

Order of operation of sample processing techniques for optimal 1D SDS-PAGE experiment. The numbered lanes correspond to combinations of the described purification methods. The numbers below the gel indicate the number of proteins identified by each method as well as the corresponding percentage based on 71 uniquely identified proteins from the C. saccharolyticus secretome sample.

Protein Identification Attributed to Sample Preparation

Interrogations by nanoLC-ESI-LTQ-FT-ICR MS and evaluation by the MASCOT-ProteoIQ bioinformatic platform (see Fig. 4 for workflow) confidently identified 71 proteins in the C. saccharolyticus secretome sample from the order of operation experiments with < 1% FDR (see Table 1a). Fifteen proteins were identified with one peptide (Table 1a dark shaded boxes); however after inspecting the MS2 spectra and considering the protein probability value, 1 identified protein was eliminated from the protein inventory. Fourteen proteins were identified as putative uncharacterized entities and the Protein Basic Local Alignment Search Tool 2.2.23 (Blastp) and Superfamily database of structural and functional protein annotation [47] were employed to determine possible functions listed in Table 1a following classification of putative. The number of protein identifications varies as a function of the purification method. Here, it is apparent that the C18 bead method in combination with another protein cleanup technique provides the most advantageous outcome in terms of number of proteins identified in this study; those techniques incorporating two methods resulted in 27–89% of the total identified proteins, whereas the C18 technique (5b) alone resulted in 4% or 3 proteins. Three techniques represented the majority (76–89%) of the proteins identified, acetone precipitation-C18 beads (1-5b) and both combinations of phenol extraction and C18 beads (5b-3, and 3-5b), resulting in nearly identical proteins despite differences in purification principles. Table 1a illustrates these similarities as well as includes a measurement of relative quantification suggesting explanation of protein recovery and most efficient sample preparation for C. saccharolyticus extracellular proteins.

Fig. 4.

Experimental workflow from start to finish of secretome sample preparation and evaluations. Order of operation investigations analyzed by GeLC-MS2 were assessed through a bioinformatic platform consisting of Mascot, ProteoIQ, and prediction servers. The sample preparation technique identifying the most proteins in conclusion of database searching (black outlined files) was suggested for use in future studies. Complementing the protein identification and spectral counts, prediction servers offered insight into the probable biological location of each protein.

Table 1.

Proteins identified and corresponding label-free relative quantification with SpC. a Complete list of proteins identified in the study arranged alphabetically by sequence ID. A shaded box indicates the identification of the particular protein by the described method and the number within the box equals the number of total SpC for that particular identification. The darker shaded boxes indicate the protein was identified with one tryptic peptide; however still maintaining < 1% FDR. b Comparison of SpC and normalized SpC of two proteins from the complete list. SpC is indicated first with normalized SpC in parenthesis.

| a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5b | 5b-1 | 1-5b | 5b-3 | 3-5b | Protein Sequence ID |

| 3 | 19 | 63 | 54 | 58 | Total Proteins Identified |

| 17 | 50 | 28 | A4XFY3 Putative, probable polyprotein | ||

| 6 | 29 | 17 | A4XG54 Periplasmic binding protein/Lacl transcriptional regulator precursor | ||

| 10 | 2 | 1 | A4XG90 Putative, probable ISOPREN_C2_like protein | ||

| 9 | 2 | A4XG91 Putative, probable transglutaminase domain protein | |||

| 14 | A4XGB3 5-methyltetrahydropteroyltriglutamate–homocysteine S-methyltransferase | ||||

| 1 | 3 | A4XGF7 D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, NAD-binding | |||

| 5 | 24 | 15 | A4XGN5 Extracellular solute-binding protein, family 1 precursor | ||

| 1 | 3 | 3 | A4XGZ2 or A4XH19 Glutamate synthase | ||

| 2 | A4XHB1 Aspartyl-tRNA synthetase | ||||

| 13 | 4 | 7 | A4XHC3 Pullulanase, type I precursor | ||

| 3 | 4 | 1 | A4XHF8 Pyruvate carboxyltransferase | ||

| 1 | A4XHI0 Pyruvate carboxyltransferase | ||||

| 10 | 6 | 7 | A4XHI4 Aconitase | ||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | A4XHL2 Transcriptional regulator/glucokinase | ||

| 1 | 52 | 23 | 41 | 44 | A4XHT4 Putative, probable 2-oxoacid ferredoxin/llavodoxin oxidoreductase protein |

| 1 | A4XHV9 TIG Trigger factor | ||||

| 2 | A4XI26 Ser-tRNA(Thr) hydrolase/threonyl-tRNA synthetase | ||||

| 39 | 2 | 16 | A4XI36 EFG Elongation factor G | ||

| 21 | 22 | 51 | A4XI37 EFTU Elongation factor Tu | ||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | A4XI48 Aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase | ||

| 5 | 3 | 2 | A4XIF2 Putative, probably acriflavin resistance protein B | ||

| 8 | 8 | 6 | A4XIF3 Putative, probable toxin complex protein | ||

| 4 | 79 | 51 | 74 | A4XIF5 Glycoside hydrolase, family 48 precursor | |

| 2 | 14 | 14 | 19 | A4XIF6 Glycoside hydrolase, family 5 precursor | |

| 2 | 12 | 9 | 10 | A4XIF7 Cellulose 1,4–beta-cellobiosidase precursor | |

| 2 | 35 | 17 | 20 | A4XIF8 Cellulase, Cellulose 1,4–beta-cellobiosidase precursor | |

| 2 | A4XIG9 Cellobiose phosphorylase | ||||

| 4 | 3 | A4XIL8 2-isopropylmalate synthase | |||

| 2 | 2 | A4XIL9 2-isopropylmalate synthase | |||

| 3 | A4XIQ5 Mannose-6-phosphate isomerase/glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | A4XIQ7 Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | A4XJ08 CH 10 10 kDa chaperonin | |

| 44 | 25 | 28 | A4XJ09 CH60 60 kDa chaperonin | ||

| 2 | 3 | A4XJ20 L-aspartate aminotransferase/phosphoserine aminotransferase | |||

| 2 | 23 | 4 | 16 | A4XJ21 D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase | |

| 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | A4XJ27 Ig domain protein, group 2 domain protein precursor | |

| 2 | 2 | A4XJH3 Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, gamma subunit | |||

| 2 | 5 | 6 | A4XJH5 Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, alpha subunit | ||

| 4 | 1 | 3 | A4XJH6 Thiamine pyrophosphate enzyme domain protein TPP-binding | ||

| 2 | 5 | 11 | 6 | A4XJI8 Putative, probable zinc figure associated protein | |

| 12 | 1 | 4 | A4XJP0 Cell wall hydrolase/autolysin precursor | ||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | A4XJW3 Acyl carrier protein synthase II | |

| 1 | 3 | 4 | A4XJW4 3-oxoacyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] synthase II | ||

| 9 | A4XJY3 Putative, probable phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | ||||

| 2 | 5 | A4XKI0 6-phosphofructokinase | |||

| 11 | 3 | 1 | A4XKL3 NADH dehydrogenase | ||

| 10 | 11 | 6 | A4XKL4 Hydrogenase, Fe-only | ||

| 2 | 1 | 1 | A4XKR2 SYI Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase | ||

| 2 | 11 | 4 | 14 | A4XKR7 Putative, probable peptidase M56 | |

| 8 | 20 | A4XKV0 ENO Enolase | |||

| 19 | 5 | A4XKV2 Phosphoglycerate kinase/triosephosphate isomerase | |||

| 4 | 4 | 11 | A4XKV3 Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | ||

| 3 | 87 | 67 | 62 | A4XKV5 Pyruvate phosphate dikinase | |

| 3 | 1 | A4XKX0 ATPB ATP synthase subunit beta | |||

| 3 | 1 | A4XL01 2-alkenal reductase | |||

| 1 | A4XL36 TAL Probable transaldolase | ||||

| 5 | A4XL41 Phosphotransacetylase | ||||

| 1 | 5 | 2 | A4XL61 Serine hydroxymethyltransferase | ||

| 1 | 6 | 12 | 12 | A4XLH0 Putative, probable PKD domain-containing protein | |

| 12 | 15 | 23 | A4XLH1 Putative, probable polyamine oxidase | ||

| 4 | 5 | 13 | A4XLI2 Putative, probable polyamine oxidase | ||

| 1 | A4XLL5 Putative, conservative domain with unknown function | ||||

| 2 | 3 | A4XM01 EFTS Elongation factor Ts | |||

| 1 | 3 | A4XM28 Putative, probable membrane protein | |||

| 7 | A4XM70 Alpha amylase, catalytic region | ||||

| 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | A4XM72 Rubrerythrin | |

| 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | A4XM87 S-layer domain protein precursor | |

| 7 | 40 | 58 | 55 | 63 | A4XM93 S-layer domain protein precursor |

| 3 | 6 | 17 | 8 | A4XMD5 Extracellular solute-binding protein, family 1 precursor | |

| 1 | 28 | 29 | 62 | A4XME8 D-xylose ABC transporter, periplasmic substrate-binding protein precursor | |

| 2 | 3 | A4XMZ6 Ferritin, Dps family protein | |||

| 10 | 129 | 739 | 618 | 737 | Overall Total Spectral Counts |

| b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein ID | MW, kDa | 5b | 5b-1 | 1-5b | 5b-3 | 3-5b |

| S-layer domain (A4XM93) | 108 | 2 (1) | 36 (0.918) | 53 (0.733) | 48 (0.515) | 55 (0.516) |

| Putative uncharacterized (A4XLH0) | 36 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.082) | 6 (0.267) | 14 (0.485) | 16 (0.484) |

Spectral counting relatively quantifies proteins by the number of MS2 spectra from peptides corresponding to a particular protein [48–52]. This assessment of SpC is inherent in the collected data, and is merited the most straightforward label-free quantification method. The overall total SpC for each order of operation experiment provide a reflection of total sample recovery, and range from 10–739 overall total SpC. Species identified with increased numbers of SpC, suggesting highly abundant proteins, were more likely to be identified by 4–5 order of operation experiments. Normalized SpC [53], see Part II of this investigation for an in-depth discussion, were also computed in order for corroboration (data not shown for all identified proteins). For example, S-layer domain protein precursor (A4XM93) was identified by all five techniques, and the number of total SpC per function of purification method varies greatly from 7 by the C18 bead method (5b) to 63 SpC by the phenol extraction-C18 bead method (3-5b) and is described in Table 1b. This suggests that the Slayer domain protein precursor is in high abundance in the initial unprocessed sample and is sufficiently recovered by all order of operation methods except for C18 beads alone (5b). A contrasting example of a lesser abundant species, as described by fewer overall SpC in Table 1b and comparison of normalized SpC with the S-layer domain protein, a putative, probable PKD domain-containing protein (A4XLH0) was identified by each combination method, and only one SpC was demonstrated by the C18 bead-acetone precipitation method (5b-1), whereas the other methods resulted in 6–12 SpC. This pattern of total SpC corresponding to protein abundance and sample recovery is present in most of the data, although a few exceptions exist. It is evident that the three combination order of operation experiments, acetone preciptitation-C18 beads (1-5b), phenol extraction-C18 beads (3-5b), and C18 beads-phenol extraction (5b-3) are nearly equivalent in performance identifying 63, 58, and 54 proteins, respectively, and providing 739, 737, and 618 overall total SpC, respectively.

Interestingly, the second step of the top three order of operation techniques conclude with a purification method reliant on hydrophobic interaction. This is presumably a factor in the number of homologous protein identifications. It can also be proposed that highly abundant proteins are better recovered following the sample purification methods. The flux in SpC of the homologous proteins can be an indicator of sample recovery as opposed to types of proteins identified by different techniques. For instance, the combination technique C18 beads-acetone precipitation (5b-1) contributes 129 overall total SpC identifying few proteins. In general these identifications had fewer SpC as compared to the top three combination techniques. Further probing this method (5b-1), a reason for so many fewer protein identifications may result from difficultly reconstituting the purified protein following acetone precipitation. The tertiary structure of proteins may be altered as the aqueous solution surrounding the analyte is replaced with acetone. In addition, drying down the sample to remove solvent, the structure is further vulnerable to modification and leads to reconstitution difficulties, and thus sample loss.

Biological Importance and Evidence for Secretion

Noteworthy, C. saccharolyticus has the most active and stable celluloytic enzymes, cellulases, in the genus Clostridium, which contributes to the approximately 20% of open reading frames of known function encoding carbohydrate degrading-type proteins/peptides [2, 13]. Accordingly, carbohydrate degrading species were identified in the C. saccharolyticus secretome sample (see Table 1a), for example cellulase (A4XIF7 and A4XIF8), glycoside hydrolases (A4XIF5 and A4XIF6), and pullulanase (A4XHC3), as well as 14 putative uncharacterized proteins. The variety of enzymes, such as those mentioned, evidence the potential benefit of an individual thermophilic microorganism targeting complex carbohydrates for degradation and the production of bioenergy in a single step, or consolidated bioprocessing in bioenergy production, a process in which substrate utilization and product formation are combined [54, 55].

Almost all proteins resulting in prediction for secretion and/or transmembrane domains (28 of 30 total proteins) fell within the species identified by the acetone precipitation-C18 beads technique (1-5b) and the phenol extraction-C18 bead technique (3-5b), and are described in Table 2a. Of all identified proteins 8 and 13 from 1-5b and 3-5b, respectively, were not identified by the said techniques, but did not result in output when evaluated by the various prediction tools. The combination technique involving the C18 beads and phenol extraction (5b-3) identified 2 fewer proteins with sample preparation taking roughly half the time (~100 min) compared those methods involving acetone precipitation. Based upon the number of proteins identified, as well as prediction evaluation of the proteins, the acetone precipitation-C18 beads method (1-5b) for secretome sample preparation offers the greatest benefit, with the combinations of C18 beads and phenol extraction (5b-3 and 3-5b) following close behind.

Table 2.

Summary of identified C. saccharolyticus secretome proteins with output from prediction server evaluation. a Total proteins predicted for secretion and containing Transmembrane domains as a function of preparation method. b List of proteins predicted to contain a signal peptide or transmembrane domain moiety. Proteins arranged by prediction features followed by protein type and sequence ID.

| a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technique | 5b | 5b-1 | 1-5b | 5b-3 | 3-5b |

| Predicted Secreted | 2 | 9 | 19 | 17 | 19 |

| Predicted Transmembrane Domain | 1 | 3 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Total | 3 | 12 | 28 | 26 | 28 |

| b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence ID | Phobius Signal Peptide | Phobius Trans. Domain | SignalP | TMHMM | SecretomeP | TatP |

| Predicted Secreted Protein | ||||||

| A4XIF5 Glycoside hydrolase, family 48 precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XIF7 Cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XIF8 Cellulase, Cellulose 1,4-beta-cellobiosidase precursor | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| A4XHC3 Pullulanase, type I precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XG90 Putative, probable ISOPREN_C2_like protein | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XHT4 Putative, probable 2-oxoacid ferredoxin/flavodoxin oxidoreductase protein | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XLH1 Putative, probable polyamine oxidase | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XLI2 Putative, probable polyamine oxidase | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XM28 Putative, probable membrane protein | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XKR7 Putative, probable peptidase M56 | Yes | Yes | ||||

| A4XM87 S-layer domain protein precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XM93 S-layer domain protein precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XGN5 Extracellular solute-binding protein, family 1 precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XMD5 Extracellular solute-binding protein, family 1 precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | |||

| A4XJP0 Cell wall hydrolase autolysin precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XG54 Periplasmic binding protein Lacl transcriptional regulator precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XJ27 Ig domain protein, group 2 domain protein precursor | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XJH6 Thiamine pyrophosphate enzyme domain protein TPP-binding | Yes | |||||

| A4XJH3 Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, gamma subunit* | Yes | |||||

| Predicted Anchored to Transmembrane Domain | ||||||

| A4XIF6 Glycoside hydrolase, family 5 precursor | 1 | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XJW4 3-oxoacyl-acyl-carrier-protein synthase II | 1 | |||||

| A4XME8 D-xylose ABC transporter, periplasmic substrate-binding protein precursor | 1 | Yes | 1 | |||

| A4XL01 2-alkenal reductase | 1 | 1 | Yes | |||

| A4XFY3 Putative, probable polyprotein | 1 | 1 | Yes | |||

| A4XIF2 Putative, probably acriflavin resistance protein B | 1 | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XIF3 Putative, probable toxin complex protein | 1 | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XJI8 Putative, probable zinc figure associated protein | 1 | Yes | 1 | Yes | ||

| A4XJY3 Putative, probable phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | 1 | |||||

| A4XLH0 Putative, probable PKD domain-containing protein | 1 | 1 | Yes | |||

| A4XG91 Putative, probable transglutaminase domain protein | Yes | 3 | Yes | 4 | ||

Predicted as potential Tat signal peptide but motif absent.

Of the 19 proteins predicted for secretion, 17 were unanimously predicted to have signal peptides by Phobius however mixed results were generated with SignalP and TMHMM (see Table 2b). Two enzymes were predicted for translocation to the extracellular milieu by the Tat pathway, thiamine pyrophosphate enzyme domain protein TPP-binding and pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase gamma subunit, although the twin-arginine motif was not explicitly found in the later. Nine proteins were predicted to contain transmembrane domains with Phobius, while TMHMM suggested 24 proteins had this moiety. TMHMM reinforced most of the predictions proposed by Phobius, but appeared to excessively suggest the presence of transmembrane domains when signal peptide recognition was the superior choice. In one instance, a putative uncharacterized protein precursor (A4XG91) was predicted by Phobius to contain both a signal peptide and several transmembrane domains, the same predictions were generated by SignalP and TMHMM, and thus no precise classification can be determined.

Conclusions

The investigations in Part I of this study provided molecular level proteomic insight into the surroundings of C. saccharolyticus and the material released into the extracellular space or culture medium. To adequately study the secretome, several preparation techniques were performed prior to nanoLC-MS2 and the bioinformatic platform as illustrated in Fig. 4. Although requiring roughly twice as much time as other techniques (~200 min), the acetone-precipitation-C18 beads method (1-5b) gave the most protein identifications of the methods evaluated. This was followed by combinations of phenol extraction and C18 beads techniques (3-5b and 5b-3) resulting in 7–12% fewer identifications and requiring less time (~100 min). To ensure the most thorough secretome analysis it is essential to employ a sample preparation technique affording the greatest sample recovery and consequently many protein identifications. It was evidenced that the species identified by 4–5 purification methods had greater numbers of SpC suggesting greater protein concentration in the unprocessed secretome sample as well as greater sample recovery from purification.

Approximately 19 of the 71 total proteins identified in the secretome of the extreme thermophile C. saccharolyticus were predicted to feature moieties highly suggesting and complementing their presence in the secretome. While the secretome should encompass only those species released out into the extracellular space, over 70% of proteins identified were deficient of a moiety for translocation as determined by the publicly available prediction servers (i.e., Phobius, SignalP, TMHMM, SecretomeP, TatP). Several factors may cause this behavior. The particular prediction servers employed for protein evaluation only detect three routes of translocation while several more exist. Also, the servers are trained on limited data quantities, due to limited experimental data, and may cause deficiencies and possible inaccuracies in prediction. Regarding the biological sample, cell lysis would expose intercellular material to the extracellular milieu and consequently their detection. Probability also exists that detected peptides may be cleaved from proteins anchored to the plasma membrane. Overall, the sample preparation method provides satisfactory performance in defining the extracellular proteome of the thermophilic bacterial microorganism C. saccharolyticus with promise to traverse other species to continue examination of microbial applications and environments.

Supplementary Material

Table S1 Homo sapiens and Bos taurus proteins included in the C. saccharolyticus-Reverse-S. cerevisiae database protein FASTA formatted file for protein identification.

Table S2 Composition of DSMZ 640 Caldicellulosiruptor medium and concentrations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health (Grant 5T32GM00-8776-08), which supports GLA in the North Carolina State University Molecular Biotechnology Training Program, and the W. M. Keck Foundation. RMK acknowledges support from the US National Science Foundation (CBT0617272) and the Bioenergy Science Center (BESC), a U.S. DOE Bioenergy Research Center supported by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. DLL acknowledges support from a US Department of Education GAANN Fellowship.

References

- 1.Antranikian G, Egorova K. Extremophiles, a Unique Resource of Biocatalysts for Industrial Biotechnology. In: Gerday C, Glansdorff N, editors. Physiology and Biochemistry of Extremophiles. ASM Press; Washington, D.C: 2007. pp. 361–406. [Google Scholar]

- 2.VanFossen AL, Lewis DL, Nichols JD, Kelly RM. Polysaccharide degradation and synthesis by extremely nermophilic anaerobes. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1125:322–337. doi: 10.1196/annals.1419.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vafiadi C, Topakas E, Biely P, Christakopoulos P. Purification, characterization and mass spectrometric sequencing of a thermophilic glucuronoyl esterase from Sporotrichum thermophile. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;296:178–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barabote RD, Xie G, Leu DH, Normand P, Necsulea A, Daubin V, Medigue C, Adney WS, Xu XC, Lapidus A, Parales RE, Detter C, Pujic P, Bruce D, Lavire C, Challacombe JF, Brettin TS, Berry AM. Complete genome of the cellulolytic thermophile Acidothermus cellulolyticus 11B provides insights into its ecophysiological and evolutionary adaptations. Genome Res. 2009;19:1033–1043. doi: 10.1101/gr.084848.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asada Y, Endo S, Inoue Y, Mamiya H, Hara A, Kunishima N, Matsunaga T. Biochemical and structural characterization of a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase of Thermus thermophilus HB8 A hyperthermostable aldose-1-dehydrogenase with broad substrate specificity. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;178:117–126. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muhammad SA, Ahmad S, Hameed A. Antibiotic Production by Thermophilic Bacillus Specie Sat-4. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2009;22:339–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esikova TZ, Temirov YV, Sokolov SL, Alakhov YB. Secondary antimicrobial metabolites produced by thermophilic Bacillus spp. strains VK2 and VK21. Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2002;38:226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato S, Hutchison CA, Harris JI. Thermostable Sequence-Specific Endonuclease from Thermus-Aquaticus. PNAS. 1977;74:542–546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.2.542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjalsma H, Bolhuis A, Jongbloed JDH, Bron S, van Dijl JM. Signal peptide-dependent protein transport in Bacillus subtilis: a genome-based survey of the secretome. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:515–547. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.515-547.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou M, Boekhorst J, Francke C, Siezen RJ. LocateP: Genome-scale subcellular-location predictor for bacterial proteins. BMC Bioinf. 2008;9:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hathout Y. Approaches to the study of the cell secretome. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2007;4:239–248. doi: 10.1586/14789450.4.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rainey FA, Donnison AM, Janssen PH, Saul D, Rodrigo A, Bergquist PL, Daniel RM, Stackebrandt E, Morgan HW. Description of Caldicellulosiruptor-Saccharolyticus Gen-Nov, Sp-Nov - an Obligately Anaerobic, Extremely Thermophilic, Cellulolytic Bacterium. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;120:263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blumer-Schuette SE, Kataeva I, Westpheling J, Adams MWW, Kelly RM. Extremely thermophilic microorganisms for biomass conversion: status and prospects. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2008;19:210–217. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rezaul K, Wu LF, Mayya V, Hwang SI, Han D. A systematic characterization of mitochondrial proteome from human T leukemia cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:169–181. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400115-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, von Heijne G, Brunak S. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:783–795. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nielsen H, Engelbrecht J, Brunak S, vonHeijne G. Identification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic signal peptides and prediction of their cleavage sites. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1–6. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Does C, Nouwen N, Driessen AJM. The Sec Translocase. In: Oudega B, editor. Protein Secretion Pathways in Bacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2003. p. 296. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bendtsen JD, Nielsen H, Widdick D, Palmer T, Brunak S. Prediction of twin-arginine signal peptides. BMC Bioinf. 2005;6:167. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muesch A, Hartmann E, Rohde K, Rubartelli A, Sitia R, Rapoport TA. A Novel Pathway for Secretory Proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:86–88. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90186-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubartelli A, Cozzolino F, Talio M, Sitia R. A Novel Secretory Pathway for Interleukin-1-Beta, a Protein Lacking a Signal Sequence. EMBO J. 1990;9:1503–1510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08268.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harth G, Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. Glutamine-Synthetase of Mycobacterium-Tuberculosis - Extracellular Release and Characterization of Its Enzymatic-Activity. PNAS. 1994;91:9342–9346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harth G, Horwitz MA. Expression and efficient export of enzymatically active Mycobacterium tuberculosis glutamine synthetase in Mycobacterium smegmatis and evidence that the information for export is contained within the protein. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:22728–22735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.36.22728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bendtsen JD, Kiemer L, Fausboll A, Brunak S. Non-classical protein secretion in bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 2005;5:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer ELL. A combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction method. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kall L, Krogh A, Sonnhammer ELL. Advantages of combined transmembrane topology and signal peptide prediction - the Phobius web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W429–W432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Werken HJG, Verhaart MRA, VanFossen AL, Willquist K, Lewis DL, Nichols JD, Goorissen HP, Mongodin EF, Nelson KE, van Niel EWJ, Stams AJM, Ward DE, de Vos WM, van der Oost J, Kelly RM, Kengen SWM. Hydrogenomics of the Extremely Thermophilic Bacterium Caldicellulosiruptor saccharolyticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6720–6729. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00968-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.(2004) Pierce Technical Resource: TR00490.

- 29.Jiang L, He L, Fountoulakis M. Comparison of protein precipitation methods for sample preparation prior to proteomic analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2004;1023:317–320. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sauve DM, Ho DT, Roberge M. Concentration of Dilute Protein for Gel-electrophoresis. Anal Biochem. 1995;226:382–383. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winston RL, Fitzgerald MC. Concentration and desalting of protein samples for mass spectrometry analysis. Anal Biochem. 1998;262:83–85. doi: 10.1006/abio.1998.2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havlis J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2856–2860. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews GL, Shuford CM, Burnett JC, Hawkridge AM, Muddiman DC. Coupling of a vented column with splitless nanoRPLC-ESI-MS for the improved separation and detection of brain natriuretic peptide-32 and its proteolytic peptides. J Chromatogr B. 2009;877:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perkins DN, Pappin DJC, Creasy DM, Cottrell JS. Probability-based protein identification by searching sequence databases using mass spectrometry data. Electrophoresis. 1999;20:3551–3567. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991201)20:18<3551::AID-ELPS3551>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weatherly DB, Atwood JA, Minning TA, Cavola C, Tarleton RL, Orlando R. A heuristic method for assigning a false-discovery rate for protein identifications from mascot database search results. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:762–772. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400215-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zakowski J. On the purification of soya-urease through precipitation with acetone and carbonic acids. Hoppe-Seyler’s Z Physiol Chem. 1931;202:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thongboonkerd V, McLeish KR, Arthur JM, Klein JB. Proteomic analysis of normal human urinary proteins isolated by acetone precipitation or ultracentrifugation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:119A–119A. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2002.kid565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Collier TS, Hawkridge AM, Georgianna DR, Payne GA, Muddiman DC. Top-down identification and quantification of stable isotope labeled proteins from Aspergillus flavus using online nano-flow reversed-phase liquid chromatography coupled to a LTQ-FTICR mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2008;80:4994–5001. doi: 10.1021/ac800254z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sahyun M, Alsberg CL. On rabbit liver glycogen and its preparation. J Biol Chem. 1930;89:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chevallet M, Diemer H, Van Dorssealer A, Villiers C, Rabilloud T. Toward a better analysis of secreted proteins: the example of the myeloid cells secretome. Proteomics. 2007;7:1757–1770. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200601024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer JW, Gerlough TD. A simple method for preparing antigenic substances from the typhoid bacillus. Science. 1940;92:155–156. doi: 10.1126/science.92.2381.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marusyk R, Sergeant A. A Simple Method for Dialysis of Small-Volume Samples. Anal Biochem. 1980;105:403–404. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bergen HR, Vasmatzis G, Cliby WA, Johnson KL, Oberg AL, Muddiman DC. Discovery of ovarian cancer biomarkers in serum using NanoLC electrospray ionization TOF and FT-ICR mass spectrometry. Dis Markers. 2003;19:239–249. doi: 10.1155/2004/797204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson KL, Mason CJ, Muddiman DC, Eckel JE. Analysis of the low molecular weight fraction of serum by LC-dual ESI-FT-ICR mass spectrometry: Precision of retention time, mass, and ion abundance. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5097–5103. doi: 10.1021/ac0497003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basrai MA, Hieter P, Boeke JD. Small open reading frames: Beautiful needles in the haystack. Genome Res. 1997;7:768–771. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.8.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gough J, Karplus K, Hughey R, Chothia C. Assignment of homology to genome sequences using a library of hidden Markov models that represent all proteins of known structure. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:903–919. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bantscheff M, Schirle M, Sweetman G, Rick J, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: a critical review. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;389:1017–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao J, Friedrichs MS, Dongre AR, Opiteck GJ. Guidelines for the routine application of the peptide hits technique. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:1231–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu HB, Sadygov RG, Yates JR. A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193–4201. doi: 10.1021/ac0498563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Old WM, Meyer-Arendt K, Aveline-Wolf L, Pierce KG, Mendoza A, Sevinsky JR, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Comparison of label-free methods for quantifying human proteins by shotgun proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1487–1502. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500084-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zybailov B, Coleman MK, Florens L, Washburn MP. Correlation of relative abundance ratios derived from peptide ion chromatograms and spectrum counting for quantitative proteomic analysis using stable isotope labeling. Anal Chem. 2005;77:6218–6224. doi: 10.1021/ac050846r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zybailov B, Mosley AL, Sardiu ME, Coleman MK, Florens L, Washburn MP. Statistical analysis of membrane proteome expression changes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:2339–2347. doi: 10.1021/pr060161n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lynd LR, Weimer PJ, van Zyl WH, Pretorius IS. Microbial cellulose utilization: Fundamentals and biotechnology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2002;66:506–577. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.506-577.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lynd LR, Elander RT, Wyman CE. Likely features and costs of mature biomass ethanol technology. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 1996;57–8:741–761. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Homo sapiens and Bos taurus proteins included in the C. saccharolyticus-Reverse-S. cerevisiae database protein FASTA formatted file for protein identification.

Table S2 Composition of DSMZ 640 Caldicellulosiruptor medium and concentrations.