Abstract

We use the framework of coarsened data to motivate performing sensitivity analysis in the presence of incomplete data. To perform the sensitivity analysis, we specify pattern-mixture models to allow departures from the assumption of coarsening at random, a generalization of missing at random and independent censoring. We apply the concept of coarsening to address potential bias from missing data and interval-censored data in a randomized controlled trial of an herbal treatment for acute hepatitis. Computer code using SAS PROC NLMIXED for fitting the models is provided.

Keywords: Coarsened data, Interval censoring, Missing data, Nonignorable missingness, Sensitivity analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

The term coarsened data refers to a broad class of incomplete data structures that includes missing and censored data as special cases (Birmingham et al., 2003; Gill et al., 1997; Heitjan, 1993, 1994; Heitjan and Rubin, 1991). Multiple types of coarsened data are often encountered when analyzing data from clinical trials. For example, a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial was performed to assess whether an herbal treatment was effective at relieving clinical symptoms from acute hepatitis. The investigators were interested in comparing the placebo and intervention groups’ 8-week declines in total bilirubin, a continuous biomarker of impaired biliary excretion, and time to alleviation of elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT), an indicator of liver inflammation. All patients provided data at the baseline visit, but some patients missed prescheduled follow-up visits. Because patients may miss visits, total bilirubin at 8 weeks may be missing. Moreover, the time to alleviation of elevated ALT may be interval-censored for patients who returned to the study after missing visits, or it may be right-censored for those who dropped out of the study. Investigators were concerned about selection bias due to missingness for total bilirubin and censoring for time to alleviation of elevated ALT. In other words, investigators were concerned that the coarsening mechanisms may depend on the potentially unobserved outcomes of interest.

Statistical analyses of coarsened data are most often performed assuming special cases of coarsening at random (CAR), such as missing at random (MAR) or independent censoring. However, statisticians have developed methods to handle data that are coarsened not at random (CNAR). For data that are missing not at random (MNAR) (Little and Rubin, 2002; Rubin, 1976), methods include multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987), weighted estimating equations (Robins et al., 1995; Rotnitzky et al., 1998), and likelihood-based methods such as the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm (Dempster et al., 1977) for selection (Heckman, 1976) or pattern-mixture models (Little, 1993, 1994; Little and Wang, 1996). Methods for addressing noninformative and informative interval censoring have also been proposed, including EM-based (Shardell et al., 2007, 2008a,b; Turnbull, 1976) and imputation-based (Bebchuk and Betensky, 2000) methods. Sun (2006) includes additional approaches. Thus, methodology has been developed separately for different types of coarsened data.

In this article, we use the framework of coarsened data to examine a unified approach to perform sensitivity analyses. We exemplify the approach by focusing on the special cases of interval censoring and missingness here. For both types of coarsening, we propose pattern-mixture models to model the coarsening mechanism. These models involve factoring the joint distribution of the study outcome and coarsening mechanism into the product of the marginal coarsening-mechanism distribution and the conditional distribution of the outcome given the coarsening mechanism. Further, we propose a novel approach to estimate the cumulative incidence function in the presence of informative interval censoring. We illustrate how to perform a sensitivity analysis of results with respect to the coarsening mechanism using SAS PROC NLMIXED (SAS Institute, Inc., 2004).

2. NOTATION, COARSENING MECHANISMS, AND MODELS

2.1. Notation

We first consider a general notation; then we adapt it for the special cases of missing and interval-censored data. Following the notation of Gill et al. (1997), let X denote the outcome of interest taking on values x in E. Let ℰ denote the collection of all possible sets of E into which X may be coarsened. Let 𝒳 be a random variable that takes on values A in ℰ that is, A is a non-empty subset of E. The variable 𝒳 is a coarsening of X if X ∈ 𝒳 with probability 1.

2.2. Coarsening Mechanisms

Using the aforementioned notation, we can present the idea of CAR first described in Heitjan and Rubin (1991). In this section, we start with a general representation of CAR; then we consider the special cases of missing follow-up outcomes and interval-censored data.

Ignoring treatment group and other fully observed covariates for now, CAR means that

| (1) |

Thus, CAR means that the events X = x and 𝒳 = A are conditionally independent given X ∈ A. In other words, knowing the exact value of the outcome (i.e., that X = x) provides no more information about the coarsening mechanism than knowing the set of values into which the outcome is coarsened (i.e., that X ∈ A). Equation (1) is a selection model; it describes the distribution of the coarsening, given the outcome. Using Bayes’s theorem, CAR can also be presented as a pattern-mixture model:

| (2) |

Equation (2) clarifies that under the assumption of CAR, the coarsening mechanism is ignorable. In particular, the left-hand side of (2) involves the outcome (X) and the coarsening (𝒳), whereas the right side only involves the outcome. In other words, knowing that the outcome was coarsened into a set of values (i.e., that 𝒳 = A) provides no more information about the outcome than knowing that it falls somewhere in the set (i.e., that X ∈ A). Moreover,Gill et al. (1997) showed that when parameters for X and 𝒳 are distinct, then under CAR, the joint likelihood factors the parameters.

Before discussing models to relax CAR, we first adapt (2) to specify MAR and independent censoring.

2.2.1. Coarsening Mechanisms for Missing Follow-Up Outcomes

Let Y1 denote a continuous outcome at baseline that is always observed, and let Y2 be a potentially missing outcome at follow-up (8 weeks post randomization in the hepatitis trial). In this context, X = Y2 and E = ℛ, the real line. Let M be an indicator such that M = 1 if Y2 is missing, and M = 0 if Y2 is observed. The random variable M defines the coarsening of Y2: if M = 0, then 𝒳 = {Y2}, and if M = 1, then 𝒳 = ℛ. Thus, ℰ is a collection of sets that includes ℛ and each element of ℛ.

In this case, we represent CAR using densities like in Birmingham et al. (2003) and Rotnitzky et al. (2001), rather than distributions like in Gill et al. (1997). CAR means that

| (3) |

a well-known representation for MAR, and a useful expression for performing sensitivity analyses. In the context of a clinical study, Eq. (3) means that the distribution of the study outcome (Y2) is equal for participants who did drop out (M = 1) and did not drop out (M = 0), and it is therefore equal to the outcome distribution for all participants, regardless of dropout status.

2.2.2. Coarsening Mechanisms for Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data

In the context of discrete-time interval-censored data, let X = T, the time to an event, and let E be a finite set consisting of possible discrete event times. If the study consists of V prescheduled follow-up visits, T is the number of the first visit after which the event occurred, and E = {1,…, V, V + 1}, where T = V + 1 denotes that the event occurs after the last study visit or never; e.g., see Shardell et al. (2007, 2008a,b) and Rotnitzky et al. (2001). If left censoring is possible, then E = {0, 1,…, V, V + 1}, where T = 0 denotes that the event occurred prior to enrollment. Further, ℰ denotes the collection of all possible intervals into which T can be coarsened. The coarsening, 𝒳, is denoted by a pair of variables, L and R, which are the left and right endpoints, respectively, of the random censoring interval. Lastly, an element A ∈ ℰ is of the form [l, r], where l ≤ r and I, r ∈ E. Thus we can rewrite Eq. (2) as

| (4) |

In the context of a clinical study, Eq. (4) means that the distribution of the event time of the study endpoint (T) is equal for participants who are censored into the interval [l, r] and all participants whose event occurs between times l and r, regardless of censoring status.

2.3. Models

We describe pattern-mixture restrictions based on exponential tilting (Barndorff-Nielsen and Cox, 1989) to relax the CAR assumption in Eq. (2) to allow CNAR assumptions. Let Z denote treatment group, where Z = 0 for the placebo, and Z = 1 for the experimental treatment. We are interested in departures of CAR within levels of Z.

Using the general notation, the CNAR models are specified as

where c(Z) = E[exp{q(X, Z)}|Z, X ∈ A], and q(X, Z) is an unidentifiable user-specified function. The role of q(X, Z) is to “tilt” the distribution of X toward higher or lower values of X relative to the distribution assumed under CAR, Pr(X = x | Z, X ∈ A). Examples of q(X, Z) for missing and interval-censored data are described next.

2.3.1. Models for Missing Follow-Up Outcomes

To specify the joint distribution of (Yl, Y2, M), we place pattern-mixture restrictions on the unidentifiable quantity f(Y2 |Y1, Z, M = 1). Let

| (5) |

Thus, q1(Y1, Y2, Z) specifies departures from CAR within levels of Y1 and Z, and c1(Y1, Z) = E[exp{q1(Y1, Y2, Z)}|Y1, Z, M = 0].

We consider the function

| (6) |

as in Birmingham et al. (2003). Equation (6) implies that Y1 does not modify the relationship between Y2 and missingness. The parameter is unidentifiable, and can differ according to Z, but is treated as fixed and known in estimation. A sensitivity analysis is performed by analyzing the data over plausible ranges of . When is tilted toward larger values of Y2 relative to CAR, whereas when is tilted toward smaller values of Y2 relative to CAR. In the context of the hepatitis treatment trial, means that those with missing total bilirubin are assumed to have stochastically higher total bilirubin levels compared to those with observed total bilirubin. That is, dropouts are assumed to be sicker on average than non-dropouts. On the other hand, means that dropouts are assumed to be healthier on average than non-dropouts. Note that implies CAR.

As discussed in previous work (Birmingham et al., 2003; Rotnitzky et al., 2001), applying Bayes’s theorem to (5) leads to

| (7) |

Plugging Eq. (6) into Eq. (7) and taking the natural log of both sides shows that

where h(Y1, Z) = log{Odds(M = 1 | Y1, Z)/c1(Y1, Z)}. Thus, has the selection-model interpretation of the Z-specific log-odds ratio of being missing (M = 1) per unit difference of Y2 controlling for Y1. Specific values of to use in sensitivity analyses depend on scientific background knowledge and should be derived from subject-matter experts (White et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2004). Aspects of this process are illustrated in the application to the hepatitis data. Details of estimation are included in Appendix 1, while the SAS code is included in Appendix 2.

2.3.2. Models for Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data

The analogous pattern-mixture restriction for interval-censored data is

| (8) |

The function q2(t, l, r, Z) specifies departures from CAR within levels of l, r, and Z; c2(l, r, Z) = E[exp{q2(t, l, r, Z)}|Z,T ∈ [l, r]].

We consider the function q2 proposed by Shardell et al. (2007, 2008a,b):

| (9) |

When , the event is assumed to occur stochastically later in the interval [l, r] relative to CAR; when , the event is assumed to occur stochastically earlier in the interval [l, r] relative to CAR; and when , CAR is assumed.

Shardell et al. (2007, 2008a,b) also showed that Eq. (9) has a selection-model interpretation. First, note that by adapting Eq. (1) to interval censoring, CAR within levels of Z means

for all [l, r] ∈ ℰ = {[l, r] : l ≤ r, l, r ∈ E}. Thus, using Bayes’s theorem on (8),

| (10) |

Consider two possible values for t: t = r and t = l. Using Eq. (10),

The last equality follows from Eq. (9), because and q2(l, l, r, Z) = 0. Thus, is the Z-specific log probability ratio of having [L, R] = [l, r] comparing those with T = r to those with T = l. Details of estimation and a test statistic are presented in Appendix 1. The SAS code is in Appendix 2.

3. SIMULATION STUDIES

We performed a simulation study to assess the finite-sample characteristics of the estimation procedures. Estimates were derived using sample sizes of n = 100 based on 5,000 iterations.

3.1. Missing Follow-Up Outcomes

We simulated binary treatment group Z according to a Bernoulli distribution with Pr(Z = z) = 0.5. We simulated M from a Bernoulli distribution with πz = 0.15(1 - Z) + 0.35Z, producing 25% missing data. Let µyk|zm = E[Yk|Z = z, M = m] and let σykyk′|zm = Cov[Yk, Yk′,|Z = z, M = m] for k, k′ = 1, 2; z = 0, 1; m = 0, 1. Y1 was simulated from a normal distribution conditional on Z and M with µy1|00 = 9, µy1|10 = 9, µy1|01 = 14, µy1|11 = 14 and σy1y1|zm = 1(1 — M) + 1.5M. When M = 0, Y2 was simulated from a normal distribution conditional on Y1, Z, and M = 0, where it was specified that µy2|00 = 8, µy2|10 = 7.5, σy1y2|z0 = 0.5, and σy2y2|z0 =1. We used q1(·) from Eq. (6) to model the missingness mechanism with . When M = 1, Y2 was simulated from a normal distribution conditional on Y1, Z, and M = 1 based on the mean and variance implied by the pattern-mixture restrictions. We set µyk|z = β0 + β1Z + β2I(k = 2) + β3ZI(k = 2) and solved for β.

The results, presented in Table 1, focus on β3, the target of inference. Table 1 shows that the proposed method performs well when the missing-data mechanism is correctly specified. In particular, bias is negligible, the estimated standard error corresponds closely to the empirical standard deviation, and empirical coverage of the 95% confidence interval is close to the nominal coverage of 95% when assumed equals true ϕ1. The magnitude of bias depends on the magnitude and direction of misspecification of ϕ1. For example, when ϕ1 = (‒log(2), ‒ log(2)), yet CAR is assumed, the degree of misspecification for both treatment groups is of equal magnitude in the same direction, and thus bias is relatively small, 9.8%. In contrast, when ϕ1 = (‒log(2), log(2)), yet CAR is assumed, the degree of misspecification for both treatment groups is of equal magnitude, but in opposite directions, thus bias is relatively large, −35.6%. A secondary simulation using as large as (log(5), log(5)) produced similar results (not shown).

Table 1.

Simulation results for data with missing outcomes: 5,000 iterations; n = 100; 25% missing data; % Bias = 100(β̂3 − β3)/|β3|; standard error (SE); empirical standard deviation (ESD)

| True | True | True β3 | Assumed ϕ1 |

% Bias | SE | ESD | 95% CI Cover |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −log(2) | −log(2) | −1.103 | Truth | −0.3 | 0.362 | 0.374 | 94.8 |

| CAR | 9.8 | 0.329 | 0.339 | 91.4 | |||

| 0 | −0.922 | Truth | 0.4 | 0.340 | 0.340 | 95.0 | |

| CAR | −9.0 | 0.328 | 0.328 | 95.1 | |||

| log(2) | −0.740 | Truth | −4.0 | 0.324 | 0.329 | 94.2 | |

| CAR | −35.6 | 0.328 | 0.332 | 89.1 | |||

| 0 | −log(2) | −1.182 | Truth | −1.2 | 0.350 | 0.355 | 94.7 |

| CAR | 16.1 | 0.328 | 0.333 | 88.5 | |||

| 0 | −1.000 | Truth/CAR | −0.3 | 0.328 | 0.339 | 94.8 | |

| log(2) | −0.818 | Truth | 1.8 | 0.311 | 0.319 | 94.4 | |

| CAR | −23.2 | 0.328 | 0.336 | 92.3 | |||

| log(2) | −log(2) | −1.260 | Truth | −2.2 | 0.341 | 0.344 | 95.0 |

| CAR | 20.8 | 0.328 | 0.331 | 84.3 | |||

| 0 | −1.078 | Truth | −0.6 | 0.318 | 0.319 | 94.9 | |

| CAR | 7.6 | 0.328 | 0.328 | 93.4 | |||

| log(2) | −0.896 | Truth | 0.6 | 0.301 | 0.303 | 95.0 | |

| CAR | −11.7 | 0.329 | 0.332 | 94.5 |

Note. 95% CI Cover, empirical percent coverage of the 95% confidence interval.

3.2. Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data

We specified V = 5 and simulated event time T according to a multinomial distribution with probabilities pt = 1/6 for t = 1…,6. Conditional on T, censoring intervals [L, R] were simulated using q2(·) in Eq. (9). Data were generated for ϕ2 ∈ {‒log(2), 0, log(2)}. The cumulative distribution, F(t), was estimated for correctly and incorrectly assumed values of ϕ2. The results, presented in Table 2, show that estimates of F(t), t = 2, 4 are biased when ϕ2 is incorrectly specified. When CAR (ϕ2 = 0) is assumed, F(t) is underestimated when true ϕ2 = − log(2), and F(t) is overestimated when true ϕ2 = log (2). However, bias is negligible when ϕ2 is correctly specified. Moreover, the estimated standard errors are close to the empirical standard deviations. A secondary simulation using ϕ2 as large as log(5) produced similar results (not shown).

Table 2.

Simulation results for interval-censored data: 5,000 iterations, V =5, n = 100, 86% censoring

| True ϕ2 |

Assumed ϕ2 |

F̂(2) (SE) (ESD) |

F̂(4) (SE) (ESD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| −log(2) | −log(2) | 0.334 (0.051) | 0.667 (0.051) |

| (0.052) | (0.051) | ||

| 0 | 0.315 (0.051) | 0.649 (0.052) | |

| (0.052) | (0.053) | ||

| log(2) | 0.296 (0.050) | 0.631 (0.052) | |

| (0.050) | (0.053) | ||

| 0 | −log(2) | 0.361 (0.053) | 0.680 (0.049) |

| (0.054) | (0.050) | ||

| 0 | 0.336 (0.053) | 0.666 (0.051) | |

| (0.053) | (0.051) | ||

| log(2) | 0.311 (0.051) | 0.651 (0.051) | |

| (0.052) | (0.052) | ||

| log(2) | −log(2) | 0.383 (0.053) | 0.694 (0.048) |

| (0.054) | (0.049) | ||

| 0 | 0.359 (0.053) | 0.681 (0.050) | |

| (0.054) | (0.050) | ||

| log(2) | 0.334 (0.052) | 0.667 (0.051) | |

| (0.053) | (0.050) |

Note. Bold indicates correct assumed values for ϕ2. F(2) = 0.333, F(4)=0.667. Standard error (SE), empirical standard deviation (ESD).

4. APPLICATION TO HEPATITIS DATA

We apply our methods to a double-blind, randomized controlled trial consisting of patients with clinical symptoms of acute hepatitis. The aim of the study was to determine whether silymarin (Silybum marianum), the purified extract of milk thistle, is effective at alleviating symptoms and signs of acute hepatitis. To achieve this aim, 105 patients with elevated ALT (ALT > 40 IU/L) were recruited from two fever hospitals in rural Egypt, among whom 55 and 50 patients were randomly assigned to receive silymarin and placebo, respectively, for 4 weeks with an additional 4 weeks of follow-up. The patients were prescheduled to attend study visits at baseline (enrollment); at 2, 4, and 7 days post-baseline; and at 2, 4, and 8 weeks post-baseline. Additional details regarding the study design are reported elsewhere (El-Kamary et al., 2009). One aim of the study was to assess the effectiveness of silymarin at alleviating symptoms of hepatitis, such as elevated ALT and high levels of total bilirubin. To do so, we use intention-to-treat analyses to compare 8-week changes in total bilirubin and to compare cumulative incidence of alleviated elevated ALT (ALT > 40 IU/L) between the groups. However, missed visits led to coarsened data, and the coarsening was thought to be informative. Thus, we use a sensitivity analysis to determine the robustness of study conclusions across assumptions about coarsening. The SAS code for this application is included in Appendix 2.

4.1. Missing Follow-Up Outcome: Total Bilirubin

Total bilirubin levels were missing at the 8-week visit among 13 (26%) and 15 (30%) patients assigned to the silymarin and placebo groups, respectively. To perform a sensitivity analysis, the function q1 in Eq. (6) was used (by M.S.) to elicit assumptions (from S.S.E.) about selection bias. An exploratory analysis revealed that a log transformation was needed for total bilirubin to be normally distributed. In this case, is interpreted as the log odds ratio of being missing per unit difference in log total bilirubin.

It is difficult for subject-matter experts to interpret log units. Therefore, was elicited by comparing the odds of missing (M =1) between two hypothetical patients where the first patient’s total bilirubin was twice as high as that of the second patient. Denote this odds ratio as ORZ for those in group Z. Thus, an elicited value of is log(ORz)/log(2). The ranges of elicited values for ORZ were 1/3.0 to 1.0 for both study groups, meaning that those with higher total bilirubin levels were assumed to have lower or equal odds of being missing compared to those with lower total bilirubin levels. Those with elevated total bilirubin were thought most likely to not feel well, and therefore would be motivated to attend study visits. Thus, a patient was believed to have from 3 times lower to equal odds of missing compared to a patient with half the 8-week total bilirubin level who has the same treatment assignment and the same baseline total bilirubin level. The elicited ranges did not differ by study group because treatment assignment was double blinded. The elicited range of ORZ corresponds to ranging from −1.58 to 0 (CAR).

Mean levels of baseline log total bilirubin levels were 1.48 (SE = 0.16) log mg/dl and 1.86 (SE = 0.13) log mg/dl for those assigned to placebo and silymarin, respectively. We estimated the model E[Yk | Z = z] = β0 +β1Z + β2I(k = 2) + β3ZI(k = 2), where β3, the target of inference, is interpreted as the mean difference in changes of log total bilirubin. Total bilirubin levels were expected to decline over 8 weeks in both treatment groups; thus, β3 < 0 means that those assigned to the intervention have a greater average decline than those assigned to the placebo, a result that favors the intervention. The estimated mean decline in log total bilirubin among those assigned to the placebo group ranged from 2.03 (SE = 0.16) log mg/dl when OR0 = 1/3.0 to 1.74 (SE = 0.16) log mg/dl when OR0 = 1.0. The estimated mean decline in log total bilirubin among those assigned to the silymarin group ranged from 2.43 (SE = 0.18) log mg/dl when OR1 = 1/3.0 to 2.11 (SE = 0.14) log mg/dl when OR1 = 1.0.

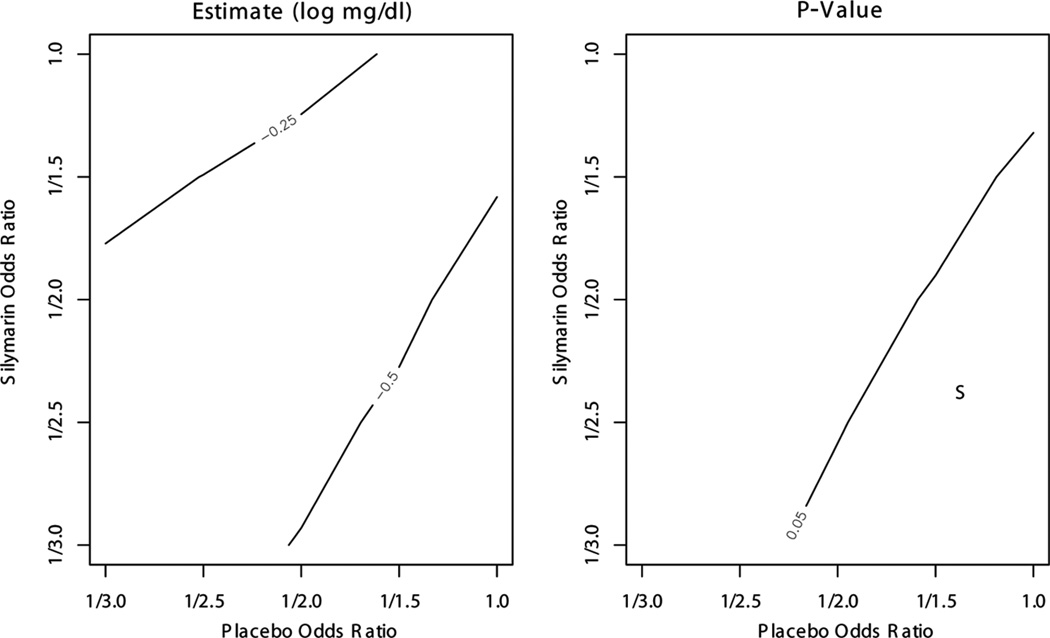

Figure 1 presents contour plots of β̂3 and the p value for a two-sided test of equal changes in log total bilirubin, H0 :β3 = 0. The estimated drop in log total bilirubin was greater in the silymarin group than in the placebo group for all combinations of OR0 and OR1 (β̂3 < 0). The difference was significant at the 0.05 level when OR0 > 0.5 and OR1 < OR0, i.e., a subset of mechanisms where selection bias is assumed to be greater for those assigned to silymarin compared with those assigned to placebo.

Figure 1.

Total bilirubin sensitivity analysis results for β3 based on elicitation. Odds ratios of response are per doubling of 8-week total bilirubin. The p value is for a two-sided test of H0 : β3 = 0. “S” indicates region where results favor silymarin over placebo (β̂3 < 0, p value < 0.05). No elicited odds ratios produced results that favor placebo over silymarin (β̂3 > 0, p value < 0.05).

We also performed analysis via PROC MIXED with a “repeated” statement using last observation carried forward (LOCF) and using only available cases, both with an unstructured variance-covariance matrix. When the data were analyzed using LOCF, we found β̂3 = 0.05, p value = 0.81. Note that using LOCF assumes Y2 = Y1 given M = 1 with probability 1. When only available cases were analyzed, the data were unbalanced, which resulted in different estimates depending on the estimation procedure used. When maximum likelihood or restricted maximum likelihood was used, we found β̂3 = −0.37, p value = 0.08. When minimum variance unbiased quadratic estimation was used, we found β̂3 = −0.39, p value = 0.08. Lastly, we analyzed the available cases using PROC GENMOD with a “repeated” statement and robust unstructured variance-covariance matrix, resulting in β̂3 = −0.35, p value = 0.09. Results using the proposed method with ϕ1 = 0 were β̂3 = −0.37, p value = 0.09.

4.2. Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data: Time to Alleviation of Elevated ALT

Missed visits for those assigned to silymarin led to right-censoring and interval-censoring among 16 (29%) and 2 (4%) patients, respectively. The analogous numbers for those assigned to placebo were 14 (28%) and 6 (12%). All patients had elevated ALT at the baseline visit.

The function q2 in Eq. (9) was used (by M.S.) to elicit assumptions (from S.S.E.) about selection bias to perform a sensitivity analysis. The elicited values for ranged from ‒ log(1.5) to log(2) for both treatment groups. This elicited range expresses uncertainty about the direction of association between event time and censoring interval. Specifying indicates that patients were assumed more likely to return to the study at the time of alleviation of elevated ALT, perhaps to obtain confirmation from medical staff; specifying indicates that patients were assumed more likely to miss several visits after alleviation of elevated ALT, perhaps because elevated ALT is associated with abdominal pain and swelling, and the lack of symptomatology for those with normal ALT levels may provide a disincentive to disrupt daily routines with study visits.

For each set of parameter estimates, an integrated difference (ID) test comparing the two groups’ cumulative incidence functions was performed. The construction of this test is described in Appendix 1. When and , the ID test statistic equals −0.54 (p value = 0.59); when and , the ID test statistic equals 0.40 (p value = 0.69). Thus, the data provide no evidence of different cumulative incidence functions over the range of elicited assumptions about selection bias. In addition, we imputed the censoring interval midpoint and endpoints among those who were interval-censored, and analyzed the data using Kaplan and Meier (1958) and the logrank test with PROC LIFETEST. When interval midpoints were used to impute interval-censored event times, p value = 0.80. Similarly, when the right endpoint was used to impute the event time for those with Z = 0, and the left endpoint was used to impute the event time for those with Z = 1, p value = 0.99. Note that this assumption is equivalent to assuming CAR for those who are right-censored (R = V + 1), and assuming and when R < V + 1. Lastly, when the right endpoint was used to impute the event time for those with Z = 1, and the left endpoint was used to impute the event time for those with Z = 0, p value = 0.57. This assumption is equivalent to assuming CAR for those who are right-censored (R = V + 1), and assuming and when R < V + 1.

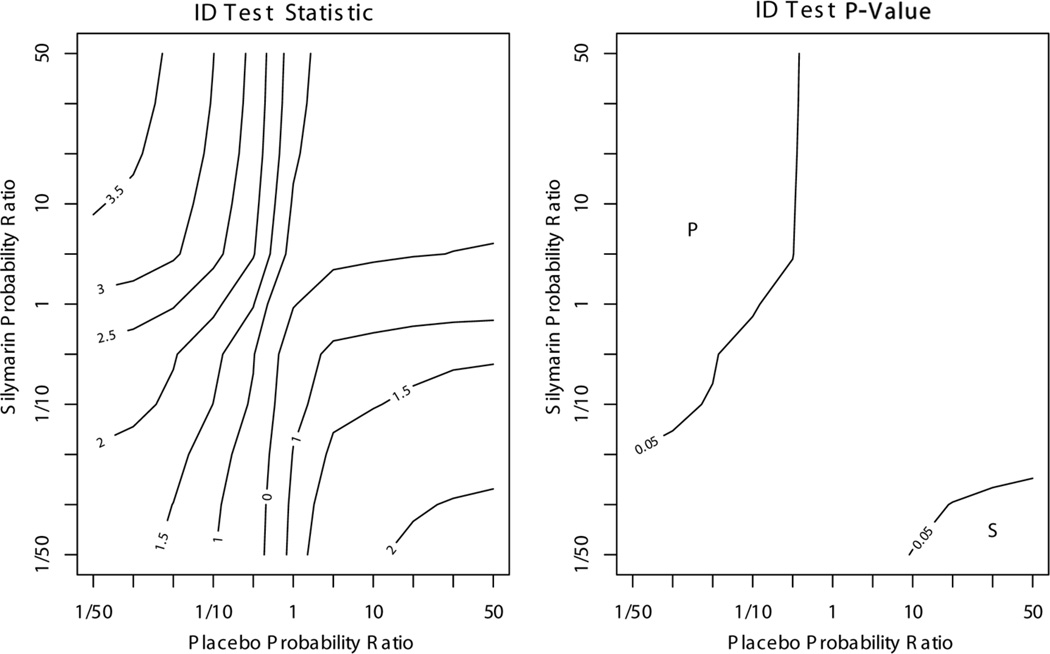

Another approach to sensitivity analysis is to examine the direction and degree of selection bias required to produce conclusions that differ from those found assuming CAR. Figure 2 presents contour plots of the ID test statistic and a p value for the two-sided test of equal incidence functions of alleviated elevated ALT for ranging from −log(50) to log(50). When and , results favor silymarin. In contrast, when and , results favor placebo. Thus, levels of selection bias would need to be of much greater magnitude than the elicited values to produce results in favor of one treatment or the other.

Figure 2.

ALT sensitivity analysis results based on extreme departures from CAR. Probability ratios of L = l, R = r compare T = r to T = l. “P” indicates region where ID test results favor placebo over silymarin (ID test statistic < 0, p value < 0.05), and “S” indicates region where ID test results favor silymarin over placebo (ID test statistic >0, p value < 0.05).

5. DISCUSSION

The benefits of sensitivity analyses over ad hoc methods such as LOCF for handling missing data have been well documented for pharmaceutical and other studies (Ali and Siddiqui, 2000; Ali and Talukder, 2005; Curran et al., 2004; Liu and Gould, 2002; Mallinckrodt et al., 2003; Rotnitzky et al., 1998, 2001; Scharfstein et al., 2003; Siddiqui and Ali, 1998; White et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2004). In particular, sensitivity analyses allow transparent reporting of the robustness of study conclusions over ranges of plausible assumptions, whereas LOCF may not be plausible and does not account for selection bias beyond differences in the last value prior to missingness. Similar benefits of sensitivity analyses over imputing endpoints or the midpoint of censoring intervals for interval-censored data have been reported (Shardell et al., 2008b).

In the context of the hepatitis example, assumptions implied by the ad hoc method of imputing censoring interval endpoints were thought implausible by a subject-matter expert. Even within the elicited range of assumptions, study results about total bilirubin were not robust to the coarsening mechanism. Depending on the nature of selection bias, the data suggested that total bilirubin may decline at greater or equal levels for those assigned to silymarin compared with those assigned to placebo. Conclusions showing no difference in speed of alleviating elevated ALT were robust to elicited assumptions about the censoring mechanism.

By conceptualizing missing data as a special case of coarsened data, a broader framework for performing sensitivity analyses can be developed. In this article, we examined a framework based on pattern-mixture models for analyzing informatively coarsened data. By starting with the general problem of coarsened data, we were able to apply the sensitivity-analysis approach to the special cases of interval-censored data and data with missing values due to drop out. This approach can be further applied to other types of coarsened data such as longitudinal data with dropouts (Birmingham et al., 2003; Molenberghs et al., 1998; Rotnitzky et al., 2001; Thijs et al., 2002). In this case, the exponential tilt model in Eq. (5) can be adapted to model departures from sequential ignorability, which is equivalent to MAR in longitudinal studies (Birmingham et al., 2003; Molenberghs et al., 1998; Scharfstein et al., 1999). Exponential tilt models for right censoring have also been proposed (Scharfstein et al., 2001). Also, if our goal was to compare the two groups’ trajectories of total bilirubin, we would have encountered non-monotone missing data, because some patients missed visits and then returned to the study. Few methods based on pattern-mixture models have been developed in the literature for handling longitudinal data with non-monotone missingness (Lin et al., 2004; Wilkins and Fitzmaurice, 2007; Vansteelandt et al., 2007).

Despite the benefits of sensitivity analysis for coarsened data, some challenges remain. First, the observed data cannot be used to determine the coarsening mechanism (that is, neither CAR nor any CNAR assumption can be ruled out as a possible mechanism based on observed data alone). Therefore, specifying “plausible” mechanisms is a difficult and subjective task. However, subjectivity in coarsened-data problems is inescapable (Kadane, 1993). Recent reports have advocated performing sensitivity analyses based on information elicited from subject-matter experts (Birmingham et al., 2003; Scharfstein et al., 2003; Shardell et al., 2007; White et al., 2007; Wood et al., 2004). Thus, a second challenge is identifying experts and deciding how to elicit information from them. Elicitation methodology is the subject of a growing body of literature (Cooke, 1991; Meyer and Booker, 1991; O’Hagan, 2006). Lastly, communicating the sensitivity of results with respect to assumptions about coarsening is challenging. Contour plots, like those presented for the silymarin trial results, are useful for this purpose.

Although challenges exist, sensitivity analysis of coarsened data using elicited expert information is still preferred over ad hoc methods because it is based on scientific background information rather than computationally simplifying assumptions. One reason that ad hoc methods are still widely used is the lack of software available for performing alternative sensitivity-analysis methods like those described in this article. To help remove this barrier, this work aimed to promote the use of sensitivity analysis by presenting a unified framework for handling types of coarsened data that are common in biopharmaceutical studies and by providing a SAS code for estimation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant K12 HD043489.

APPENDIX 1: ESTIMATION

Estimation for Missing Follow-Up Outcomes

Let µy2|y1zm = E[Y2|Y1, Z = z, M = m] and σy2y2|y1zm = Var[Y2|Y1, Z = z, M = m]. If we assume that Eq. (6) holds and that f(Y1, Y2|Z, M = 0) is bivariate normal, then

Therefore, if f(Y1, Z, M = 1) is assumed to be normal, then f(Y2|Y1, Z, M = 1) is normally distributed with and σy2y2|y1z1 = σy2y2|y1z0. Using the iterated variance, it can be shown that σy1y2|z1 = σy1y2|Z0σy1y1|Z1/σy1y1|Z0. The implication is that f(Y1, Y2|Z) is bivariate normal because it is a weighted average of two bivariate normal densities.

Let µyk|z = E[Yk|Z = z] and πz = Pr(M = 1|Z = z). Then, µyk|z = µyk|z0(1 -πz) + µyk|z1 πx. We can parameterize µyk|z as β0 + β1Z + β2I(k = 2) + β3ZI(k = 2). In this case, β3 = (µy2|1 − µy1|1) − (µy2|0 − µy1|0), the difference in mean outcome changes between the intervention and placebo groups, which was the target of inference for the hepatitis trial. To estimate the identifiable parameters, we maximize the likelihood

Once the estimates are obtained, the pattern-mixture restrictions can be used to solve for unidentifiable parameters µy2|y1z1, and σy2y2|y1z1 the iterated expectation and variance can be used to find µyk|z and σykyk′|z, = Cov[Yk, Yk′|Z = z]. This estimation procedure can be carried out using PROC NLMIXED in SAS via a user-specified “general” likelihood. Sample code for the hepatitis trial is in Appendix 2.

Estimation for Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data

The analysis goal is to estimate Pr(T = t|Z = z) = ptz and compare between treatment groups. Shardell et al. (2007, 2008a,b) treated pz = (ptz : t = 1, …, V + 1) as a vector of probabilities from a multinomial distribution and proposed estimation using the EM algorithm. We consider an alternative approach here where we maximize a pseudo-likelihood to solve a set of unbiased estimating equations. An advantage of this approach is that standard errors are easily obtained from the optimization algorithm.

Motivated by the estimating equation in Gill et al. (1997), we aim to solve

| (11) |

Let nz denote the sample size with Z = z, and let nlrz denote the sample size with L = l, R = r, and Z = z. Dividing (11) by ptz, replacing Pr(L = l, R = r|Z = z) with empirical probabilities nlrz/nz, and plugging in the pattern-mixture restriction (8) results in

| (12) |

Multiplying Eq. (12) by nz and integrating with respect to ptz results in

| (13) |

The term is analogous to the Lagrange multiplier in Shardell et al. (2007) used to specify the constraint . Equation (13) can be rewritten to handle individual (ungrouped) data. Let dijz be the indicator that j ∈ [l, r] for patient i, i = 1, …, nz. Thus, maximizing

| (14) |

solves Eq. (11). The log-pseudo-likelihood in Eq. (14) is analogous to the log-likelihood in Turnbull (1976).

One challenge in estimating pz is that one must first determine the intervals for which probability mass is identifiable. As described in Turnbull (1976), a set of disjoint intervals is constructed whose left and right endpoints lie within the observed L and R, and that contains no other members of the set of observed L and R other than their endpoints. The disjoint intervals are often referred to as “equivalence classes,” because the cumulative incidence function only jumps within the classes and the function is flat between them. The tutorial by Lindsey and Ryan (1998) provides an algorithm for determining the equivalence classes.

The estimated pz can be used to estimate Fz(·), the cumulative incidence function for treatment z, where Once estimates of Fz(t), denoted F̂z(t), and standard errors are obtained, statistics can be derived for testing the null hypothesis H0: F1(·) = F0(·). In this article, we consider a two-sided integrated difference (ID) test described in Shardell et al. (2008a). The test has numerator , where . The test statistic, can be compared to a standard normal distribution.

PROC NLMIXED in SAS can be used to maximize Eq. (14) using Newton-Raphson and to compute the integrated difference test. Code for the hepatitis trial is shown in Appendix 2.

APPENDIX 2: SAS CODE

Missing Follow-Up Outcomes

****Example data

****Data (mddat) from the hepatitis study

****Y1, Y2 are log of total bilirubin at baseline and follow-up.

****A numeric value (-999 here) is needed for missing data to avoid

****computational problems;

ID Z Y1 Y2 M

1 0 -0.91629073 -1.60943791 0

2 1 2.37954613 -999 1

3 1 2.20827441 -999 1

4 0 0.18232156 -999 1

5 1 1.48160454 -1.20397280 0

... ...

... ...

... ...

proc nlmixed data=mddat technique=newrap maxiter=1000

gconv=0.00000000001 fconv=0.00000000001;

****starting values for pi_z, mu_y1|zm, mu_y2|z0,

****sigma_y1y1|zm, sigma_y2y2|z0, sigma_y1y2|z0;

parms pi_0=0.26 pi_1=0.31

mu_y1_00=1.64 mu_y1_01=1.04 mu_y1_10=1.56

mu_y1_11=2.52 mu_y2_00=-0.22 mu_y2_10=-0.34

logsig_y1y1_00=0.66 logsig_y1y1_01=1.00

logsig_y1y1_10=0.53 logsig_y1y1_11=0.47

logsig_y2y2_00=0.38 logsig_y2y2_10=0.32

sig_y1y2_00=0.27 sig_y1y2_10=0.18;

sig_y1y1_00 = exp(logsig_y1y1_00);

sig_y1y1_01 = exp(logsig_y1y1_01);

sig_y1y1_10 = exp(logsig_y1y1_10);

sig_y1y1_11 = exp(logsig_y1y1_11);

sig_y2y2_00 = exp(logsig_y2y2_00);

sig_y2y2_10 = exp(logsig_y2y2_10);

****E[Y2 | Y1, Z=0, M=0];

mu_y2_y100 = mu_y2_00 + sig_y1y2_00/sig_y1y1_00*(Y1-mu_y1_00);

****Var[Y2 | Y1, Z=0, M=0]; sig_y2y2_y100 = sig_y2y2_00 -

sig_y1y2_00*sig_y1y2_00/

sig_y1y1_00;

****E[Y2 | Y1, Z=1, M=0];

mu_y2_y110 = mu_y2_10 + sig_y1y2_10/sig_y1y1_10*(Y1- mu_y1_10);

****Var[Y2 | Y1, Z=1, M=0]; sig_y2y2_y110 = sig_y2y2_10 -

sig_y1y2_10*sig_y1y2_10/

sig_y1y1_10;

*****LH = Pr(M=m |Z)*f(Y1 | Z, M)*[f(Y2 | Y1, Z,M=0)]ˆ(1-M);

****if Z=0 and M=0;

fobs0 = (1-pi_0)*PDF(’Normal’,Y1,mu_y1_00, sig_y1y1_00)*

PDF(’Normal’,Y2,mu_y2_y100 , sig_y2y2_y100);

****if Z=1 and M=0;

fobs1 = (1-pi_1)*PDF(’Normal’,Y1,mu_y1_10, sig_y1y1_10)*

PDF(’Normal’,Y2,mu_y2_y110 , sig_y2y2_y110);

****if Z=0 and M=1;

fmis0 = pi_0*PDF(’Normal’,Y1,mu_y1_01, sig_y1y1_01);

****if Z=1 and M=1;

fmis1 = pi_1*PDF(’Normal’,Y1,mu_y1_11, sig_y1y1_11);

if Z=0 & M=0 then lik=fobs0;

else if Z=1 & M=0 then lik=fobs1;

else if Z=0 & M=1 then lik=fmis0;

else lik=fmis1;

llik=log(lik);

****q_1(Y_1, Y_2, Z) = phiˆZ Y_2;

****Y_2 = log total bilirubin in this analysis,

****logOR_Z elicited for analysis is log(OR) of missing comparing

****one patient with exp(Y_2) twice as high as another patient;

logOR0=log(1);

logOR1=log(1);

****phiˆz = log(OR_Z)/log(2);

phi0 = logOR0/log(2);

phi1 = logOR1/log(2);

phi=phi0*(1-Z) + phi1*Z;

****Calculating means and model coefficients;

****E[Yk | Z] = B0 + B1Z + B2I(k=2) + B3ZI(k=2);

****B0 = E[Y1 | Z=0];

B0est = mu_y1_00*(1-pi_0) + mu_y1_01*(pi_0);

****E[Y1 | Z=1];

mu_y1_1 = (mu_y1_10)*(1-pi_1) + (mu_y1_11)*pi_1;

****B1 = E[Y1 | Z=1] - E[Y1 | Z=0];

B1est = mu_y1_1 - B0est;

****E[Y2 | Z=0];

mu_y2_0 = mu_y2_00*(1-pi_0) +

(mu_y2_00+ sig_y1y2_00/sig_y1y1_00*(mu_y1_01-mu_y1_00) +

phi0*sig_y2y2_y100 )*pi_0;

****B2 = E[Y2 | Z=0] - E[Y1 | Z=0];

B2est= mu_y2_0 -B0est;

****E[Y2 | Z=1];

mu_y2_1 = mu_y2_10*(1-pi_1) +

(mu_y2_10+sig_y1y2_10/sig_y1y1_10*(mu_y1_11-mu_y1_10) +

phi1*sig_y2y2_y110)*pi_1;

****B3 = (E[Y2 | Z=1] - E[Y1 | Z=1]) - (E[Y2 | Z=0] - E[Y1 | Z=0]);

B3est = mu_y2_1 - B2est - B1est - B0est;

****Y2 is a place holder because a variable is needed;

****on the left hand side of equation;

model Y2 ˜ general(llik);

****Estimates of model parameters, means, and mean changes;

estimate ’B0 = E[Y1 | Z=0]’ B0est;

estimate ’B1 = E[Y1 | Z=1] - E[Y1 | Z=0]’ B1est;

estimate ’B2 = E[Y2 | Z=0] - E[Y1 | Z=0]’ B2est;

estimate ’B3 = E[Y2 | Z=1] - B2 - B1 - B0’ B3est;

estimate ’E[Y1 | Z=1]’ mu_y1_1;

estimate ’E[Y2 | Z=0]’ mu_y2_0;

estimate ’E[Y2 | Z=1]’ mu_y2_1;

estimate ’E[Y2 | Z=1] - E[Y1 | Z=1]’ mu_y2_1 - mu_y1_1;

run;

Discrete-Time Interval-Censored Data

****Example data;

****Data (icdat) from the hepatitis study, V=6;

ID Z d1 d2 d3 d4 d5 d6 d7 left right

1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 3 3

2 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7

3 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 2 4

4 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 2

5 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 4 4

... ...

... ...

****PROC NLMIXED for informative interval censoring with V=6.;

proc nlmixed data=icdat technique=newrap maxiter=1000

gconv=0.00000000001 fconv=0.00000000001;

****starting values for Pr(T=t | Z=z)=pzt;

parms p01=0.01 p02=0.01 p03=0.02

p04=0.15 p05=0.24 p06=0.36

p11=0.01 p12=0.01 p13=0.01

p14=0.18 p15=0.19 p16=0.46;

bounds 0 <= p01 - p06 <= 1, 0 <= p11 - p16 <= 1;

p07 = 1 - p01 - p02 - p03 - p04 - p05 - p06;

p17 = 1 - p11 - p12 - p13 - p14 - p15 - p16;

****q_2(left, right, Z) = phiˆZ*I(right>left)*(t-left)/

(right-left);

****values of phiˆZ specified for analysis;

phi0 = 0;

phi1 = 0;

phi = phi0*(1-Z) + phi1*Z;

****q function at t=1,...,7;

****the (right=left) ensures that division is not by 0;

q1 = phi*(right>left)*(1-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q2 = phi*(right>left)*(2-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q3 = phi*(right>left)*(3-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q4 = phi*(right>left)*(4-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q5 = phi*(right>left)*(5-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q6 = phi*(right>left)*(6-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

q7 = phi*(right>left)*(7-left)/(right-left + (right=left));

****pseudo-likelihood;

plik0 = (d1*exp(q1)*p01 + d2*exp(q2)*p02 +

d3*exp(q3)*p03 + d4*exp(q4)*p04 + d5*exp(q5)*p05 +

d6*exp(q6)*p06 + d7*exp(q7)*p07);

plik1 = (d1*exp(q1)*p11 + d2*exp(q2)*p12 +

d3*exp(q3)*p13 + d4*exp(q4)*p14 + d5*exp(q5)*p15 +

d6*exp(q6)*p16 + d7*exp(q7)*p17);

if Z=0 then plik=plik0;

else if Z=1 then plik=plik1;

****log-pseudo-likelihood with lagrange multipliers;

lplik = log(plik) +(1-Z)*(1-p01-p02-p03-p04-p05-p06-p07) +

(Z)*(1-p11-p12-p13-p14-p15-p16-p17);

**** d1 is a place holder because;

****a variable is needed on the left-hand side;

model d1 ˜ general(lplik);

****integrated difference test;

****cdf in placebo group;

F01 = p01; F02 = F01 + p02;

F03 = F02 + p03; F04 = F03 + p04; F05 = F04 + p05;

F06 = F05 + p06;

****cdf in treatment group;

F11 = p11; F12 = F11 + p12; F13 = F12 +

p13; F14 = F13 + p14; F15 = F14 + p15;

F16 = F15 + p16;

****numerator of the integrated difference test statistic;

IDtest = (F11-F01) + (F12-F02) + (F13-F03) +

(F14-F04) + (F15-F05) + (F16-F06);

****prints the test statistic and $p$˜value;

estimate ’ID test’ IDtest;

run;

REFERENCES

- Ali MW, Siddiqui O. Multiple imputation compared with some informative dropout procedures in the estimation and comparison of rates of change in longitudinal clinical trials with dropouts. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2000;10:165–181. doi: 10.1081/BIP-100101020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali MW, Talukder E. Analysis of longitudinal binary data with missing data due to dropouts. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2005;15:993–1007. doi: 10.1080/10543400500266692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barndorff-Nielsen OE, Cox DR. Asymptotic Techniques for Use in Statistics. London: Chapman & Hall; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bebchuk JD, Betensky RA. Multiple imputation for simple estimation of the hazard function based on interval censored data. Stat. Med. 2000;19:405–419. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000215)19:3<405::aid-sim325>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham J, Rotnitzky A, Fitzmaurice GM. Pattern-mixture and selection models for analyzing longitudinal data with monotone missing patterns. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 2003;65:275–297. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke R. Experts in Uncertainty: Opinion and Subjective Probability in Science. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Curran D, Molenberghs G, Thijs H, Verbeke G. Sensitivity analysis for pattern mixture models. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2004;14:125–143. doi: 10.1081/BIP-120028510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster P, Laird N, Rubin D. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1977;39:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- El-Kamary SS, Shardell MD, Abdel-hamid M, Ismail S, El-Ateek M, Metwally M, Mikhail N, Hashem M, Mousa A, Aboul-Fotouh A, El-Kassas M, Esmat G, Strickland GT. A randomized controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of silymarin on symptoms, signs and biomarkers of acute hepatitis. Phytomedicine. 2009;16:391–400. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill RD, van der Laan NJ, Robins JM. Coarsening at random: Characterizations, conjectures and counter-examples. In: Lin DY, Fleming TR, editors. State of the Art in Survival Analysis. Vol. 123. New York: Springer Lecture Notes in Statistics; 1997. pp. 255–294. [Google Scholar]

- Heckman JJ. The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection, and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Ann. Econ. Soc. Meas. 1976;5:475–492. [Google Scholar]

- Heitjan DF. Ignorability and coarse data: Some biomedical examples. Biometrics. 1993;49:1099–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitjan DF. Ignorability in general incomplete-data models. Biometrika. 1994;81:701–708. [Google Scholar]

- Heitjan DF, Rubin DB. Ignorability and coarse data. Ann. Stat. 1991;19:2244–2253. [Google Scholar]

- Kadane JB. Subjective Bayesian analysis for surveys with missing data. Statistician. 1993;42:415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, McCulloch CE, Rosenheck RA. Latent pattern mixture models for informative intermittent missing data in longitudinal studies. Biometrics. 2004;60:295–305. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2004.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey JC, Ryan LM. Tutorial in biostatistics methods for interval-censored data. Stat. Med. 1998;17:219–238. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980130)17:2<219::aid-sim735>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;88:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. A class of pattern-mixture models for normal incomplete data. Biometrika. 1994;81:471–483. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Wang Y. Pattern-mixture models for multivariate incomplete data with covariates. Biometrics. 1996;52:98–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Gould AL. Comparison of alternative strategies for analysis of longitudinal trials with dropouts. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2002;12:207–226. doi: 10.1081/bip-120015744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt CH, Clark SW, Carroll RJ, Molenberghs G. Assessing response profiles from incomplete longitudinal clinical trial data under regulatory considerations. J. Biopharm. Stat. 2003;13:179–190. doi: 10.1081/BIP-120019265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer MA, Booker JM. Eliciting and Analyzing Expert Judgment: A Practical Guide. Philadelphia: SIAM; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Molenberghs G, Michels B, Kenward MG, Diggle PJ. Missing data mechanisms and pattern-mixture models. Stat. Neerland. 1998;52:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hagan A. Uncertain Judgements: Eliciting Experts’ Probabilities. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Robins JM, Rotnitzky A, Zhao LP. Analysis of semiparametric regression models for repeated outcomes in the presence of missing data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995;90:106–121. [Google Scholar]

- Rotnitzky A, Robins JM, Scharfstein DO. Semiparametric regression for repeated outcomes with nonignorable nonresponse. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1998;93:1321–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Rotnitzky A, Scharfstein D, Su TL, Robins J. Methods for conducting sensitivity analysis of trials with potentially nonignorable competing causes of censoring. Biometrics. 2001;57:103–113. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63:581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/IML User’s Guide. Version 9. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Scharfstein DO, Daniels MJ, Robins JM. Incorporating prior beliefs about selection bias into the analysis of randomized trials with missing outcomes. Biostatistics. 2003;4:495–512. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.4.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfstein D, Robins JM, Eddings W, Rotnitzky A. Inference in randomized studies with informative censoring and discrete time-to-event endpoints. Biometrics. 2001;57:404–413. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfstein DO, Rotnitzky A, Robins JM. Adjusting for nonignorable dropout using semiparametric nonresponse models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1999;94:1096–1120. [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Scharfstein DO, Bozzette SA. Survival curve estimation for informatively coarsened discrete event-time data. Stat. Med. 2007;26:2184–2202. doi: 10.1002/sim.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Scharfstein DO, Vlahov D, Galai N. Inference for cumulative incidence functions with informatively coarsened discrete event-time data. Stat. Med. 2008a;27:5861–5879. doi: 10.1002/sim.3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shardell M, Scharfstein DO, Vlahov D, Galai N. Sensitivity analysis using elicited expert information for inference with coarsened data: Illustration of censored discrete event times in ALIVE. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008b;168:1460–1469. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui O, Ali MW. A comparison of the random-effects pattern mixture model with last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) analysis in longitudinal clinical trials with dropouts. J. Biopharm. Stat. 1998;8:545–563. doi: 10.1080/10543409808835259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J. Statistical Analysis of Interval-Censored Failure Time Data. New York: Springer; 2006. . [Google Scholar]

- Thijs H, Molenberghs G, Michiels B, Verbeke G, Curran D. Strategies to fit pattern-mixture models. Biostatistics. 2002;3:245–265. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull BW. The empirical distribution function with arbitrarily grouped, censored and truncated data. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1976;38:290–295. [Google Scholar]

- Vansteelandt S, Rotnitzky A, Robins J. Estimation of regression models for the mean of repeated outcomes under nonignorable nonmonotone non-response. Biometrika. 2007;94:841–860. doi: 10.1093/biomet/asm070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Carpenter J, Evans S, Schroter S. Eliciting and using expert opinions about dropout bias in randomized controlled trials. Clin. Trials. 2007;4:125–139. doi: 10.1177/1740774507077849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins KJ, Fitzmaurice GM. A marginalized pattern-mixture model for longitudinal binary data when nonresponse depends on unobserved responses. Biostatistics. 2007;8:297–305. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxl010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, White IR, Thompson SG. Are missing outcome data adequately handled? A review of published randomized controlled trials in major medical journals. Clin. Trials. 2004;1:368–376. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn032oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]